1. Introduction

Organic-inorganic hybrid films are widely used in many fields, from biomedicine to electronics, as they combine the properties of both inorganic and organic materials [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Sol–gel chemistry offers a unique approach to obtaining organic-inorganic hybrids with different compositions by using several precursors that react with each other to form a metal oxide network and link organic chains [

5]. One of the best-known and most important materials for various applications is organically modified silicates (ORMOSILs) or organosilica glasses (OSG) [

6,

7,

8,

9]. These materials, based on a silicon-oxygen network, offer good thermal and chemical stability, adhesion, mechanical, optical, and electrical properties. Their good compatibility with materials and processes used in microelectronics allows for their use in semiconductor manufacturing [

10].

One of the most important microelectronic applications is as an insulator in the interconnection of integrated circuits. Silicon dioxide has been used for this purpose for many decades due to its excellent dielectric properties. Continuous advancements in speed and reductions in the size of microelectronic devices are driven by the introduction of innovative technologies and materials with enhanced properties. However, as the density of components increases, issues related to crosstalk in transistor structures emerge. Addressing this challenge requires a comprehensive approach, particularly the implementation of new conductors with lower resistance and insulating layers with reduced dielectric constants. For these reasons, silicon dioxide was replaced firstly on organosilica and subsequently on porous organosilica. These materials, which have a lower permittivity than SiO

2, are referred to as low-

k dielectrics [

11].

The inverse relationship between Young's modulus and the porosity of the material, which in turn affects mechanical strength, remains a significant challenge. High values of Young's modulus (more than 5 GPa [

12]) are essential for the successful implementation of porous dielectrics in integrated circuit (IC) manufacturing [

13]. Another significant issue associated with the porous structure is the adsorption of moisture, which subsequently deteriorates the dielectric properties of the material [

14,

15]. Therefore, to enhance hydrophobicity, it is essential to modify materials using various precursors that contain chemical groups capable of imparting high hydrophobicity. The most effective modification method involves the use of precursors with terminal methyl (–CH₃) groups. The modification of the pore surface by Si–CH₃ leads to increased silicate hydrophobicity and a reduction in the dielectric constant (

k) [

13,

16,

17,

18].

Copolymers derived from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) and methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) have gained significant popularity in sol–gel synthesis. The incorporation of the MTEOS precursor into the copolymer composition enhances hydrophobicity and decreases the dielectric constant [

19]. This effect can be attributed to the presence of a terminal methyl group in the precursor molecule. Surface hydrophobicity depends on the number of introduced Si–CH

3 bonds and residual Si–OH bonds present on the surface [

20]. To achieve sufficient hydrophobicity, the content of MTEOS must be increased. However, an increase in the methyl-containing precursor leads to a reduction in the connectivity of the Si–O–Si network and consequently to a reduction in mechanical properties [

21]. For this reason, it is challenging to strike a balance between hydrophobicity and film strength when using these two precursors. Consequently, there is a need to explore alternative methods for producing organosilica glasses.

In this study, we aimed to replace MTEOS, which contains a single terminal group, with diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS), which features two terminal methyl groups attached to a single silicon atom (a terminal dimethyl group). Several research groups have reported that the DEDMS precursor exhibits high hydrophobicity due to the presence of these two terminal methyl groups [

22,

23]. DEDMS-based copolymers are widely used in hybrid materials, including bulk materials, to improve hydrophobicity [

24,

25,

26]. However, the properties of organosilica films produced from precursors containing terminal dimethyl groups have not been extensively investigated. The objective of this research is to provide a comprehensive and detailed analysis of organosilica films with varying concentrations of methyl and dimethyl groups. This analysis will involve a comparative examination of the chemical composition, microstructure, hydrophobic characteristics, mechanical properties, and electrical properties of the materials.

2. Materials and Methods

The thin film samples were prepared from film-forming solutions using the sol–gel method. Two copolymers were selected for experiments. The first copolymer was synthesized from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS, 99.999%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) and methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA). Hydrolysis and copolymerization of TEOS and MTEOS should result in a silicon oxide network with terminal methyl groups, as the Si–CH

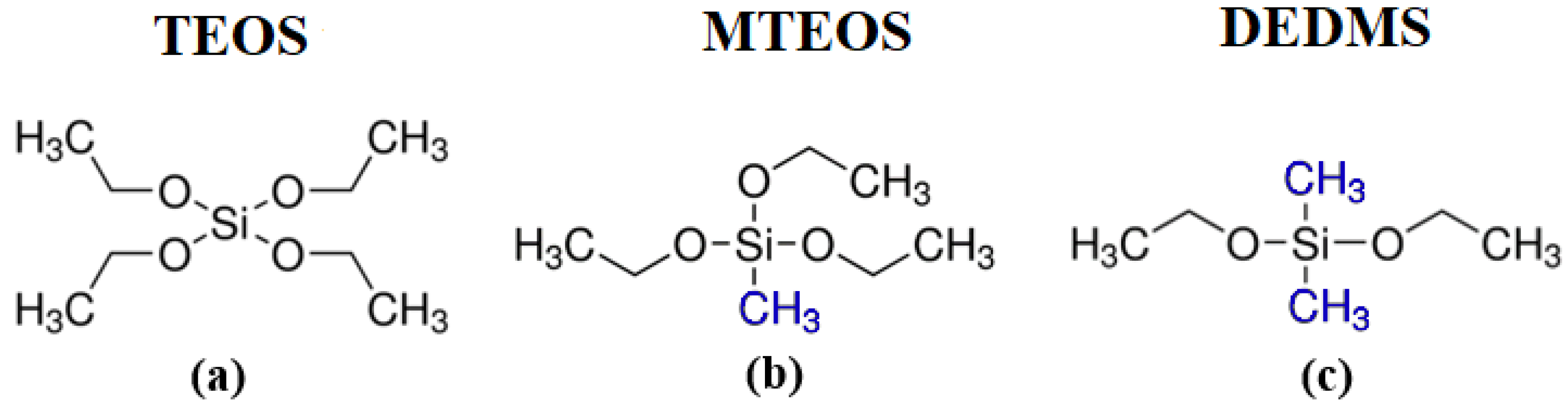

3 bond is not hydrolyzed. The synthesis of the second copolymer was also based on TEOS, but instead of MTEOS, a precursor with two terminal methyl groups, namely diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS, 97%, Acros Organics, Geel, Belgium), was added. Accordingly, this copolymer should contain dimethyl instead of methyl groups. Precursor molecules are illustrated in

Figure 1. The solutions also differed in the number of methyl groups per silicon atom. The CH

3/Si ratio was 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0 for both solutions containing MTEOS (series ‘y’) and those with DEDMS (series ‘w’). Thus, the solution with a CH

3/Si ratio of 1 was prepared using either MTEOS or a 1:1 molar ratio of TEOS to DEDMS (see

Table 1).

After maintaining the temperature at 60 °C for 180 min, the solutions were diluted with an alcohol mixture to achieve concentrations of ~1.2 wt% silicon, resulting in films with thicknesses ranging from 90 to 160 nm. The sacrificial surfactant Brij

® L4 (molecular weight 362, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI, USA) was added at a concentration of 45 wt% relative to the mass of the solid phase to induce porosity in these copolymer films via evaporation-induced self-assembly (EISA) [

27].

The films were spin-coated onto monocrystalline silicon wafers with resistivities of both 0.005 and 12 Ω∙cm, using a rotation speed of 2500 rpm. Subsequently, they were soft-baked on a hot plate at 150 °C for 30 min, followed by heat treatment in a furnace at 400 °C for 30 min in air.

The thickness (

d) and refractive index (RI,

n) at λ = 632.8 nm of the films were measured using spectral ellipsometry (SE) with an SE 850 ellipsometer (Sentech, Berlin, Germany) at a beam incidence angle of 70° over a wavelength range of 320–800 nm. The calculations were performed within the framework of the three-layer Cauchy model: air/film/silicon. Based on the known thickness values obtained after low-temperature drying and after annealing at 400 °C, the film shrinkage (Δ

d) during heat treatment was calculated using the following formula:

where

d1 is the thickness of the soft-baked film, and

d2 is the thickness after the heat treatment at 400 °C.

The infrared (IR) spectra were recorded using a Nicolet 6700 Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Waltham, MA, USA) in transmission mode, with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ and a minimum of 64 scans. To minimize noise in the spectra caused by the atmosphere, the spectrometer was intensively purged with dry, pure nitrogen. This purging process was conducted for at least 50 min, with an increased flow rate during the first half hour, ~50 standard cubic feet per hour (scfh), compared to the normal rate of 30 scfh.

The RI is used to calculate the relative or full porosity within the framework of the Lorentz–Lorenz model. In this model, the relative volume fraction of pores in the film is determined using the following expression [

28,

29]:

where

neff is the RI of the porous film;

nmat is the RI of the dense silicate film, equal to 1.46.

The open porosity, which is accessible to adsorbate molecules, and the pore radius distribution were evaluated using ellipsometric porosimetry (EP). In the porosimetry setup, the partial pressure of the adsorptive is precisely controlled to regulate the composition of the vapor–gas mixture delivered to the sample through a specialized nozzle, employing a custom-developed program. One component of the vapor–gas mixture is dry nitrogen. The second component is also dry nitrogen, which functions as a carrier gas that passes through a thermo-stabilized bubbler containing liquid isopropyl alcohol (IPA), which is utilized as the adsorbate. The degree of filling of the open porous structure of the films with condensed adsorbate was calculated using the modified Lorentz–Lorenz equation [

28,

29]:

where

neff is the RI of the porous film, partially or completely filled with adsorbate molecules,

np is the RI of the film before adsorption (empty pores), and

nads is the RI of the liquid adsorbate (1.377 for IPA). The pore size was determined by analyzing the gradual filling (adsorption) and emptying (desorption) curves, using the Kelvin and the Dubinin–Radushkevich formulas for meso- and micropore size distribution, respectively. The radius obtained from adsorption isotherms corresponds to the size of the internal cavities, while the radius derived from desorption isotherms reflects the interconnections among these cavities and the external environment.

Young's modulus is a fundamental mechanical property used to evaluate the elastic strength of a film. The values of Young's modulus are determined based on deformations induced by adsorption or desorption, exhibiting a more pronounced dependence. The Young's modulus values (

E) are calculated by approximating several points from the experimental curve that describes the change in film thickness (

d) as a function of the partial pressure (

P/

P0) of adsorbate vapors, using [

30]:

where

d0 represents the initial film thickness prior to the desorption process, specifically at

P/

P0 = 1. By fitting the experimental data points of the deformation isotherm to a logarithmic function (Equation (4)), we derive the coefficient (κ), which is then used to calculate Young's modulus [

30]:

where

R is the gas constant,

T is the temperature in Kelvin, and

VL is the molar volume of the adsorbate. This method enables the estimation of Young's modulus values for micro- and mesoporous films, reaching up to 5–8 GPa.

The mechanical properties of the films were also evaluated using the PeakForce Quantitative Nanomechanics (PFQNM) semi-contact mode with a Dimension Icon atomic force microscope (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). AFM studies in the PFQNM mode were conducted under ambient conditions using RTESPA525 silicon probes, which have a stiffness constant of

k = 200 N/m and a probe tip radius of

R = 8 nm, in accordance with refs. [

31,

32].

To investigate the surface hydrophobicity, a method for measuring the contact angle with water (WCA) was employed. For this purpose, a DSA25B WCA device (KRÜSS, Hamburg, Germany) was utilized. The WCA values were calculated as the average of at least three points, with ten photographs taken at each point. The measurements were conducted at room temperature (~23 °C). Data processing was conducted using KRÜSS ADVANCE version 1.13.0.21301.

The permittivity (k) was determined from the measured capacitance data using the formula for a parallel-plate capacitor. This measurement was performed using a mercury probe (MDC 802B-150) with a contact diameter of ~790 µm and an MDC CSM/Win Semiconductor measurement system (Materials Development Corporation, Andover, MA, USA) that contains a 4284A LCR meter (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The metal-insulator-semiconductor structure was formed by positioning a mercury point electrode on a film deposited on highly doped silicon samples. The permittivity was calculated based on the frequency dependence of the capacitance measured at zero bias voltage, within a frequency range from 1 kHz to 1 MHz.

3. Results and Discussions

Table 1 presents the names of the samples, their compositions, and the results obtained from SE measurements: thickness (

d), RI (

n) after a soft bake on a hot plate at 150 °C for 30 min, and after annealing in a furnace at 400 °C for 30 min. Additionally, it includes calculated film shrinkage (Δ

d) and full porosity (

Vfull). The crosslinking coefficient is defined as the number of Si–O–Si bonds present at specific precursor ratios, expressed by the formula:

where

mY and

mZ represent the mole fractions of the methyl-containing precursors (MTEOS or DEDMS) and TEOS, respectively;

YO and Z

O denote the number of oxygen atoms, while

YSi and

ZSi indicate the number of silicon atoms in the corresponding precursors. A higher value of

x indicates a more extensively cross-linked system, which is expected to enhance the elastic stiffness of the film material. For example, silicon dioxide has the chemical formula SiO₂, which indicates that the value of

x is equal to 2.

Table 1.

Calculated compositional parameters and results obtained from spectral ellipsometry of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS).

Table 1.

Calculated compositional parameters and results obtained from spectral ellipsometry of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS).

Sample

name |

TEOS/

MTEOS

ratio |

TEOS/

DEDMS

ratio |

TEOS

mole

fraction |

CH3/

Si

ratio |

Cross-

linking

coefficient

x in

SiOx

|

Soft bake

150 °С, 30 min |

Heat treatment

400 °С, 30 min |

d

(nm)

[±2] |

n

[±0.005] |

d

(nm)

[±2] |

n

[±0.005] |

Δd

(%)

[±2] |

Vfull

(%)

[±2] |

| 02y |

80/20 |

- |

0.8 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

116 |

1.398 |

101 |

1.239 |

13 |

45 |

| 02w |

- |

90/10 |

0.9 |

149 |

1.308 |

129 |

1.253 |

13 |

42 |

| 06y |

40/60 |

- |

0.4 |

0.6 |

1.7 |

105 |

1.374 |

97 |

1.243 |

8 |

44 |

| 06w |

- |

70/30 |

0.7 |

105 |

1.417 |

94 |

1.275 |

10 |

37 |

| 10y |

0/100 |

- |

0 |

1 |

1.5 |

96 |

1.413 |

91 |

1.285 |

5 |

35 |

| 10w |

- |

50/50 |

0.5 |

102 |

1.444 |

93 |

1.304 |

9 |

31 |

As illustrated in

Table 1, both series of samples demonstrate a decrease in the RI as the annealing temperature increases from 150 °C to 400 °C. This phenomenon can be attributed to the thermal degradation of the porogen and the subsequent formation of a porous structure within the films. In addition, the samples from the ‘y’ series exhibit higher relative porosity values compared to the samples from the ‘w’ series, which can be attributed to the significant thermal shrinkage observed in the latter.

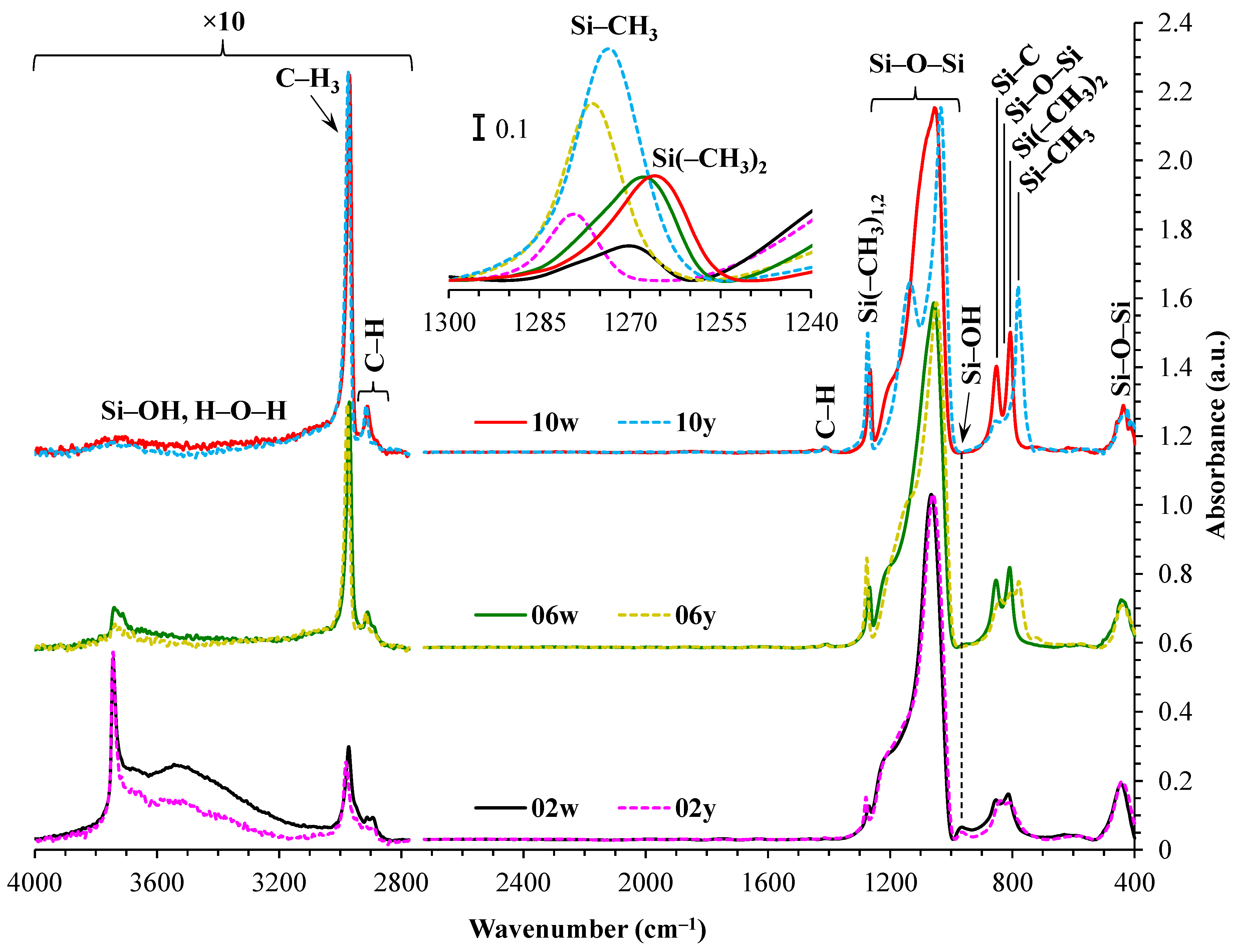

From

Figure 2, it can be seen that although calculations indicate the same number of methyl groups per silicon atom in both the ’y’ and ’w’ series, the ’w’ samples have a lower number of methyl groups (peak at 1280–1265 cm⁻¹). This discrepancy may be attributed to the lower thermal stability of dimethyl groups. In the case of CH

3/Si = 0.2, sample ‘w’ exhibits a more pronounced peak at a position of ~3500 cm⁻¹ and contains a higher amount of hydrogen-bonded surface silanols, along with adsorbed water, compared to sample ‘y’. The narrow peak at ~3750 cm

–1 is attributed to the peak associated with isolated –OH groups that are not involved in water adsorption or interactions with each other [

33,

34]. Their appearance also indicates a strong correlation with Si–OH at ~950 cm

–1, while the methyl group transforms to Si–OH during thermal destruction [

35,

36]. It is also worth noting the broadening of the Si(–CH

3)

1,2 peak, which may indicate partial destruction of the Si(–CH

3)

2 group (~1265 cm

–1) [

37,

38] during heat treatment at 400 °C. The asymmetry of the Si(–CH

3)

1,2 peak (refer to the inset in

Figure 2) indicates that some Si atoms have only a single methyl group (~1275 cm

–1) [

37,

38] after annealing.

The higher quantity of uncondensed residual silanol groups in the dimethyl samples can be attributed to the lower functionality of the DEDMS precursor, which contains two ethoxy (–OEt) functional groups, in contrast to MTEOS, which has three OEt groups available for polycondensation.

The peak associated with the presence of Si–CH

3 and/or Si(–CH

3)

2 at ~1270 cm

–1 is not clearly distinguishable [

39]. It seems that there should be a similar relative amount of these groups, adjusted for the number of Si–O–Si bonds, but there are about 1.6 times fewer methyl groups in the ‘w’ series samples. The most plausible explanation for this discrepancy is the broadening of this peak in the ‘w’ series spectra, coupled with the strengthening of the cage component, which is also shifted to the region of higher wavenumbers. Such overlapping of bands often leads to a decrease in the reliability of direct area under the curve (AUC) determination, typically resulting in an underestimation of the values obtained for the less pronounced peak. This is indirectly supported by the lack of noticeable differences in the region of C–H group vibrations at 3000–2900 cm

–1 (see

Table 4).

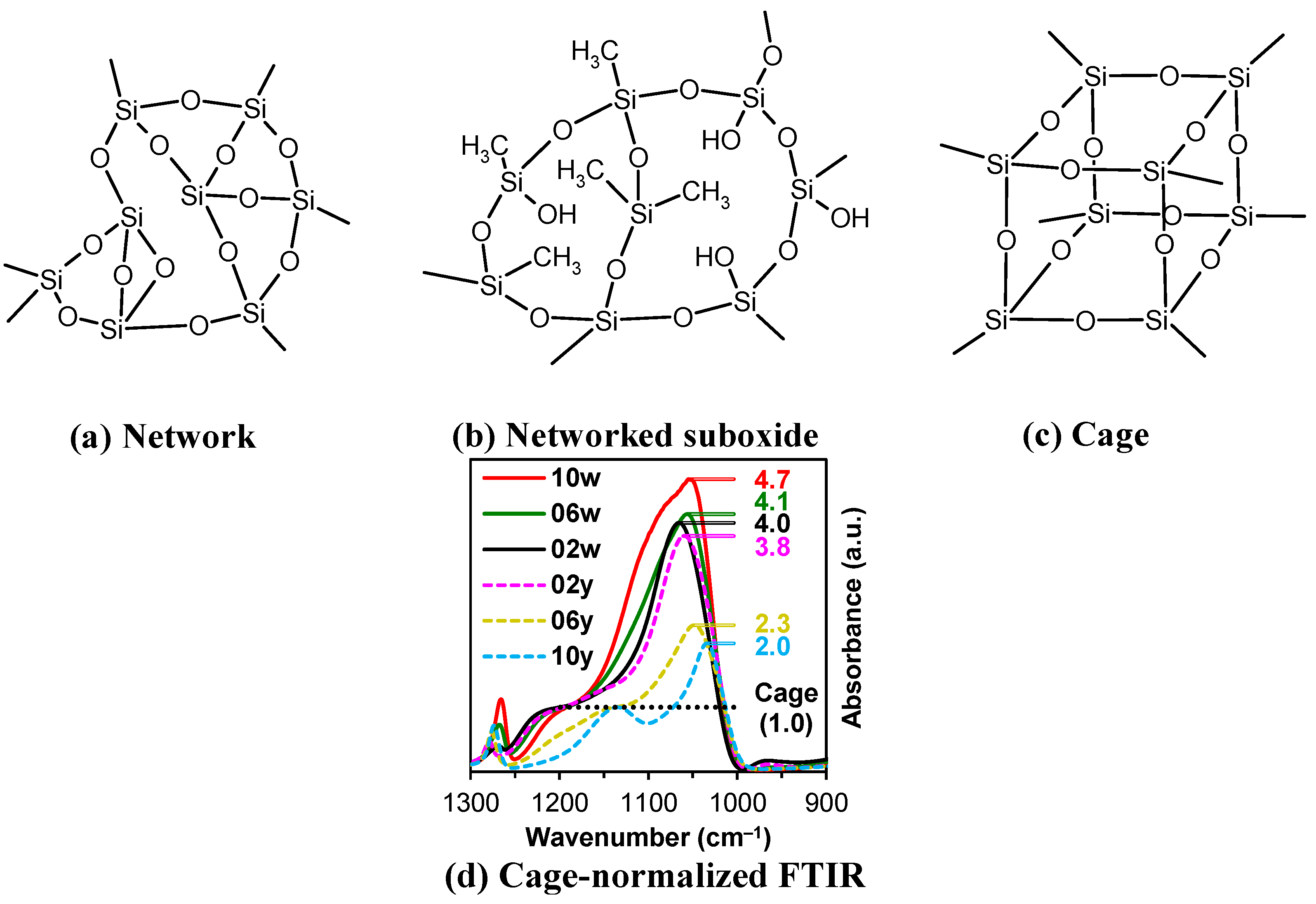

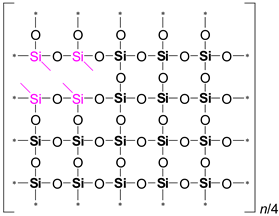

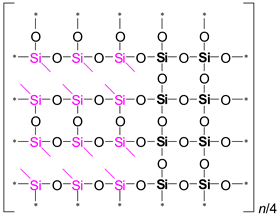

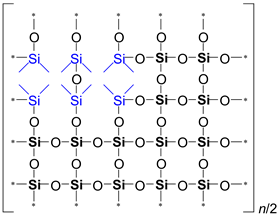

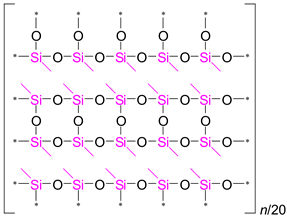

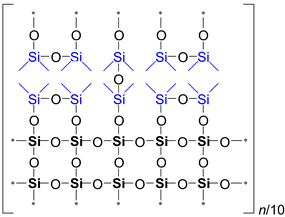

It is evident from

Table 2 that the ratio of the Network/Cage absorption intensities is significantly higher for the ’w’ series samples. The network component is characterized by a long Si–O–Si chain (SiO

2, i.e.,

x = 2; see

Figure 3a) and is located within the range of 1100–1050 cm

−1. A networked suboxide consists of a long chain of Si–O–Si with terminal groups, specifically SiO

x, where 1 <

x < 2 (see

Figure 3b). This structure is observed within the range of 1000 to 1050 cm

–1. In contrast, the cage component is associated with a short chain of Si–O–Si (see

Figure 3c) and is situated within the range of 1250–1100 cm

−1. The Network/Cage ratio provides an indirect assessment of the mechanical strength of the structure: higher values indicate a stronger structure [

41,

42,

43]. This finding correlates well with the Young's modulus values obtained through porosimetry and PFQNM AFM, as will be demonstrated later in this paper. This increase can be attributed to the greater amount of the TEOS precursor used, which promotes crosslinking. However, this also results in a side effect: increased shrinkage. Note that in the case of CH

3/Si = 0.2, this effect is less pronounced due to the higher concentration of residual silanol groups. These terminal silanol groups also contribute to an increase in the networked suboxide component, resulting in a slight rightward shift (red shift) in the position of the maximum of the Si–O–Si band, as well as broadening it.

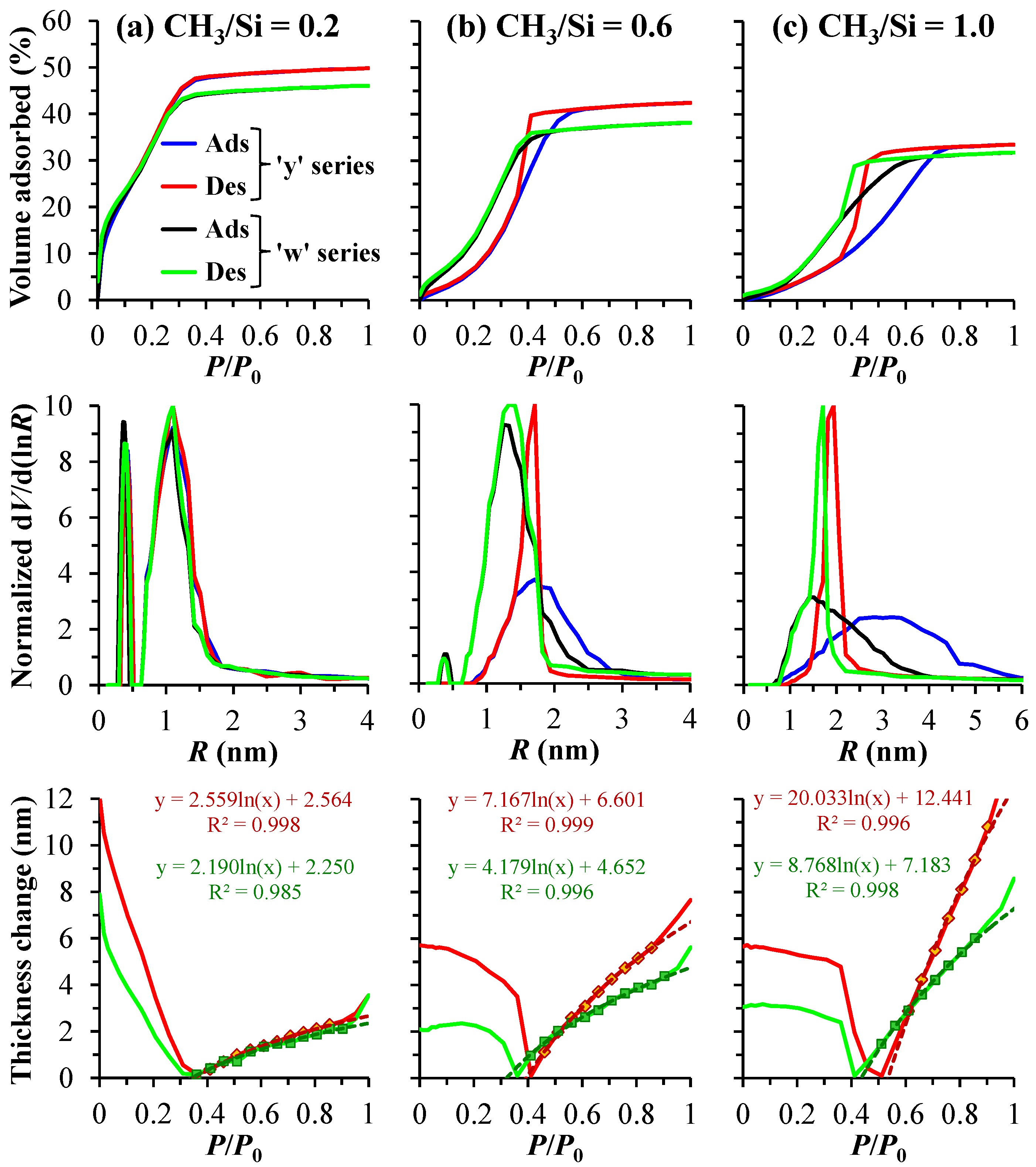

The pore structure characteristics of the two copolymer films show a difference. As shown in

Figure 4a, at a low precursor to TEOS ratio, the ‘y’ and ’w’ series samples exhibit fairly similar pore radius distributions, with a slightly larger average pore radius for the ’y’ samples, which may be attributed to an increased value of open porosity [

44]. As the concentration of the TEOS precursor in the copolymers decreases, the differences in pore radius distributions between the ‘y’ and ’w’ series samples become increasingly pronounced. Specifically, the ’w’ series samples, which contain dimethyl groups, exhibit pores with a smaller radius. This phenomenon can be attributed to an increased crosslinking density, and it becomes more pronounced as the CH

3/Si ratio increases. As is known from ref. [

30], a more crosslinked system is indicated by a less steep thickness isotherm (see the bottom line of

Figure 4). Consequently, the ‘w’ series samples exhibit a higher Young's modulus value compared to the ’y’ series. It is also important to note that, in the case of CH

3/Si = 0.6, the ’w’ series samples continue to exhibit a bimodal distribution, while the ’y’ series samples lose their microporous structure. This loss may be attributed to smaller pores merging into larger ones, resulting in an increase in the average pore radius. More detailed data obtained from porosimetry are presented in

Table 3.

Despite the results obtained in non-porous copolymer films with similar compositions [

23], which indicate a decrease in hardness and Young's modulus when replacing MTEOS with DEDMS, our EP results present a contrasting perspective. Moreover, this dynamic is evident across the entire range of ratios related to the TEOS precursor.

Table 4.

AFM Young's modulus data for porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS)—designated as series ‘y’—or with diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS)—designated as series ‘w’.

Table 4.

AFM Young's modulus data for porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS)—designated as series ‘y’—or with diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS)—designated as series ‘w’.

| CH3/Siratio |

AFM Young's modulus (GPa)

[±0.5] |

| Series ‘y’ |

Series ‘w’ |

| 0.2 |

7.5 |

8.9 |

| 0.6 |

4.2 |

4.5 |

| 1.0 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

Table 4 shows that the PFQNM AFM measurements confirm an increase in Young's modulus for samples with terminal dimethyl groups. However, this increase is counterbalanced by significant measurement errors, especially in samples with low Young's modulus values (CH

3/Si = 1.0). To illustrate the differences in Young's modulus and the Network/Cage ratios, corresponding simulations were conducted and are presented in

Table 5.

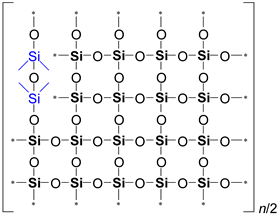

Looking at

Table 5, we observe that as the MTEOS content increases relative to the TEOS precursor, the ratio of fully crosslinked silicon atoms to the total number of silicon atoms (ψ) goes down. This trend ultimately leads to the complete disappearance of these atoms when only MTEOS is used. In the ‘w’ series samples, the presence of two methyl groups attached to silicon also results in a decrease in the number of fully crosslinked Si atoms as the concentration of the DEDMS precursor increases. However, the DEDMS precursor retains more of these atoms than the ‘y’ series does. Thus, the increased number of these atoms correlates positively with the higher Young's modulus values observed in the ‘w’ series samples. In reality, the crosslinking coefficient

x does not accurately represent the degree of crosslinking, which is determined solely by the precursor responsible for generating fully crosslinked silicon atoms within the film; that is, the mole fraction of TEOS ≡ ψ.

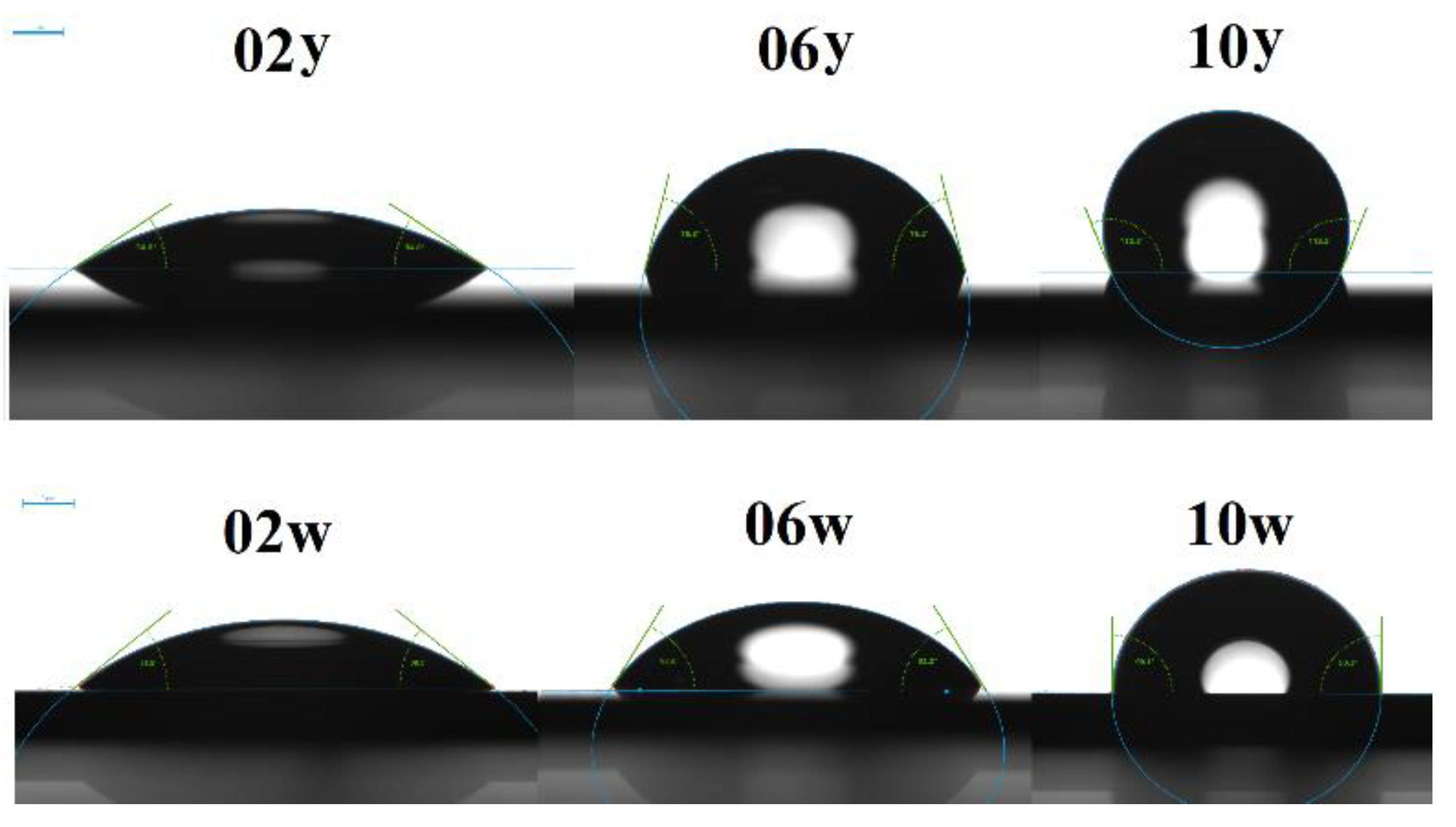

Contact angle measurements are illustrated in

Figure 5. The ’w’ samples, which had the dimethyl group, showed lower levels of hydrophobicity. This is likely due to the decreased number of methyl groups in the films that underwent heat treatment. It is also important to note that at a concentration of 100 mol% MTEOS, the film becomes hydrophobic, as its contact angle exceeds 90° [

45]. In contrast, a film composed of 100 mol% DEDMS has a contact angle that is at the threshold of hydrophobicity. Angle values for: 02y—34.8°±0.4°, 06y—75.4°±0.6°, 10y—112.2°±1.7°, 02w—38.5°±3°, 06w—62.2°±1.3°, and 10w—89.5°±1°.

The dielectric constant increases in porous organosilica films when water is absorbed because water has a very high permittivity (

k ≈ 81).

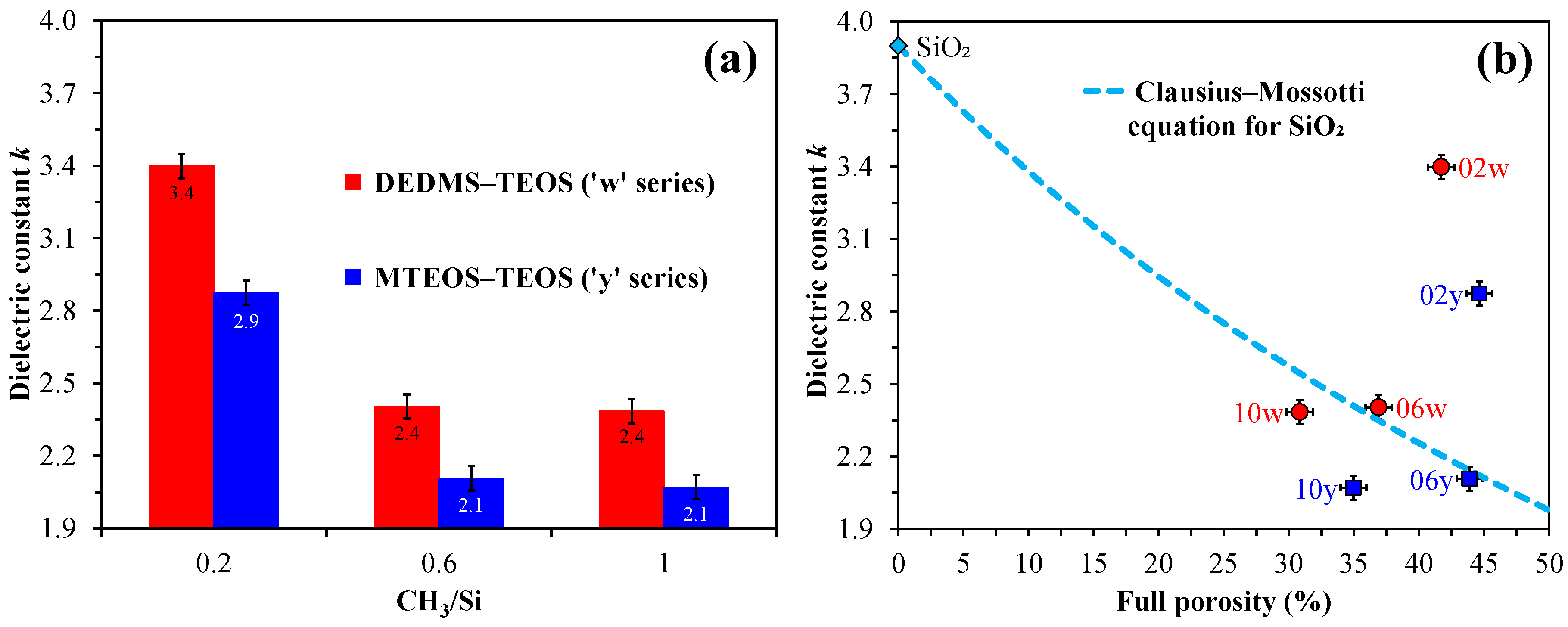

Figure 6 shows the dependence of the dielectric constant versus CH

3/Si content in copolymer films. An increase in the amount of methyl content leads to a decrease in the dielectric constant for both series. A higher amount of methyl groups and lower silanol content in the ‘y’ series lead to lower values of the dielectric constant.

Figure 6b shows the relationship between permittivity and full porosity as described by the Clausius–Mossotti equation for SiO

2. Samples 02w, 02y, and 06w are above the conventional boundary as they have a high concentration of surface silanols. The effect of water adsorption is most pronounced in the films prepared from pure TEOS, which exhibit higher leakage currents and capacitance that strongly depend on frequency. For this reason, the dielectric constant can have unusually high values, with

k > 8 [

46], compared to 2.3 for 40% porous SiO

2 (see

Figure 6b).

Therefore, the distribution and number of methyl groups within porous organosilica films can significantly impact the structure, including pore size, as well as surface chemistry, elastic properties, and dielectric constant. This provides a potential avenue for the development of films with tailored properties for diverse applications.

4. Conclusions

Organosilica films are versatile materials with a wide range of applications, including electronics, optics, catalysis, drug delivery, and many others. In the field of electronics, porous organosilica films are used as a material with a low dielectric constant. Most applications require high hydrophobicity, as water adsorption degrades film properties. The most common way to provide hydrophobicity is to protect the film surface with methyl groups. However, this leads to a reduction in the connectivity of the silicon-oxygen network and, as a result, to a degradation of the mechanical properties of the films. To find an optimal balance between these properties, we compare porous organosilica films containing methyl and dimethyl groups attached to the silicon atom.

In sol–gel synthesis, a hybrid organic-inorganic material is produced using two components: one is silicon alkoxide TEOS, which forms only a Si–O–Si network, while the other is a methyl-modified alkoxide, MTEOS, which contains Si–CH3 bonds that do not undergo hydrolysis and remain in the final material. This set of experiments is referred to as the ’y’ series. To prepare films containing Si(–CH3)2 bonds, we used diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS) instead of MTEOS, which is used in the ’w’ series. The film composition was varied by adjusting the ratio of the two components, quantified as the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0. The non-ionic surfactant Brij® was used to provide porosity by self-assembly. The study included characterization by FTIR, spectral ellipsometry, ellipsometric porosimetry, PFQNM AFM method, water contact angle, and dielectric constant.

The study revealed that, despite both the ‘y’ and ‘w’ series samples having the same ratio of methyl groups to silicon atoms, the ’y’ series films exhibit a greater number of methyl groups. This finding is supported by the FTIR spectra. Dimethyl groups are susceptible to thermal destruction, which subsequently impacts the processes of secondary condensation and crosslinking. Additional crosslinking influences the porous structure by strengthening the pore walls, as evidenced by the increased Young's modulus values of films derived from the DEDMS precursor, which increased by ~1 GPa.

The porosimetry study indicates that the ’w’ series samples exhibit a smaller average pore size compared to the ’y’ series samples. This observation is consistent with the observed decrease in open porosity. The reduced average pore size can also be attributed to increased crosslinking that occurs during the thermal destruction of dimethyl groups.

An important observation is the higher concentration of silanol groups in the ’w’ series samples, which influences water adsorption and subsequently leads to increased dielectric constant values. Additionally, the lower dielectric constant values can be attributed to reduced porosity. The combination of factors, including an increased number of Si–OH groups, a reduced number of methyl groups, and lower open and total porosity values compared to the ’y’ series samples, results in decreased hydrophobicity of the samples derived from the precursor with the terminal dimethyl group, as confirmed by WCA measurements.

A speculative model of the crosslinking behavior of MTEOS–TEOS and DEDMS–TEOS copolymer films indicates that, at equivalent ratios of methyl groups to silicon atoms, films derived from the DEDMS precursor exhibit a higher degree of crosslinking. This observation correlates with the Young's modulus values obtained through both ellipsometric porosimetry and AFM methods. It is also indirectly supported by quantitative FTIR analysis, specifically the Si–O–Si broadband.

Thus, the copolymer films containing dimethyl groups provide a higher degree of crosslinking and, therefore, higher mechanical properties than films containing the same amount of methyl groups. However, the lower thermal stability of the dimethyl bonds leads to a decrease in hydrophobic behavior and related properties, such as the dielectric constant. These data will increase our knowledge about organic-inorganic hybrid films and their structural and physical properties. The choice between these two components for practical applications depends on the requirements of the particular application.

Figure 1.

Structure of molecules: a) tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), b) methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS), c) diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS).

Figure 1.

Structure of molecules: a) tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), b) methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS), c) diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS).

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the MTEOS–TEOS (samples ’y’) and DEDMS–TEOS (samples ’w’) films. The inset displays the Si–CH3 peak normalized for thickness and open porosity. The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. In this context, MTEOS—methyltriethoxysilane, TEOS—tetraethoxysilane, DEDMS—diethoxydimethylsilane.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the MTEOS–TEOS (samples ’y’) and DEDMS–TEOS (samples ’w’) films. The inset displays the Si–CH3 peak normalized for thickness and open porosity. The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. In this context, MTEOS—methyltriethoxysilane, TEOS—tetraethoxysilane, DEDMS—diethoxydimethylsilane.

Figure 3.

Components of a broad Si–O–Si band, which includes the network (

a), networked suboxide (

b), and cage (

c) structures, observed in the range of 1300 to 1000 cm⁻¹ (

d) in the cage-normalized FTIR spectra of the MTEOS–TEOS (samples ’y’) and DEDMS–TEOS (samples ’w’) films. The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. In this context, MTEOS—methyltriethoxysilane, TEOS—tetraethoxysilane, and DEDMS—diethoxydimethylsilane. Sections (a)–(c) have been partially redrawn from ref. [

40].

Figure 3.

Components of a broad Si–O–Si band, which includes the network (

a), networked suboxide (

b), and cage (

c) structures, observed in the range of 1300 to 1000 cm⁻¹ (

d) in the cage-normalized FTIR spectra of the MTEOS–TEOS (samples ’y’) and DEDMS–TEOS (samples ’w’) films. The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. In this context, MTEOS—methyltriethoxysilane, TEOS—tetraethoxysilane, and DEDMS—diethoxydimethylsilane. Sections (a)–(c) have been partially redrawn from ref. [

40].

Figure 4.

Isotherms of adsorption (Ads) and desorption (Des) as a function of the partial pressure P/P0 of the vapor–gas mixture, which indicates the degree of pore filling with adsorbate (isopropyl alcohol, top line), the corresponding pore radius distribution (middle line), and the change in thickness during desorption (bottom line) for samples with varying numbers of methyl groups per silicon atom (CH3/Si) of 0.2 (a), 0.6 (b), and 1.0 (c). The series ‘y’ and ‘w’ represent porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS), respectively. In the bottom line, markers represent experimental data points of the deformation isotherm (Des branch), which is modeled using a logarithmic function (Equation (4)), as indicated by the dashed lines.

Figure 4.

Isotherms of adsorption (Ads) and desorption (Des) as a function of the partial pressure P/P0 of the vapor–gas mixture, which indicates the degree of pore filling with adsorbate (isopropyl alcohol, top line), the corresponding pore radius distribution (middle line), and the change in thickness during desorption (bottom line) for samples with varying numbers of methyl groups per silicon atom (CH3/Si) of 0.2 (a), 0.6 (b), and 1.0 (c). The series ‘y’ and ‘w’ represent porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS), respectively. In the bottom line, markers represent experimental data points of the deformation isotherm (Des branch), which is modeled using a logarithmic function (Equation (4)), as indicated by the dashed lines.

Figure 5.

WCA images of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) (top line) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS) (bottom line). The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. The designation ’y’ denotes the MTEOS–TEOS copolymer, while ’w’ indicates the DEDMS–TEOS copolymer.

Figure 5.

WCA images of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) (top line) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS) (bottom line). The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. The designation ’y’ denotes the MTEOS–TEOS copolymer, while ’w’ indicates the DEDMS–TEOS copolymer.

Figure 6.

Relationship between the dielectric constant (

k) and the number of methyl groups per silicon atom (CH

3/Si) (

a), as well as the relationship between

k and full porosity (

b). The latter is compared with data plotted according to the Clausius–Mossotti equation [

39] for SiO

2. The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. The designation ’y’ denotes the MTEOS–TEOS copolymer, while ’w’ indicates the DEDMS–TEOS copolymer. In this context, MTEOS—methyltriethoxysilane, TEOS—tetraethoxysilane, DEDMS—diethoxydimethylsilane.

Figure 6.

Relationship between the dielectric constant (

k) and the number of methyl groups per silicon atom (CH

3/Si) (

a), as well as the relationship between

k and full porosity (

b). The latter is compared with data plotted according to the Clausius–Mossotti equation [

39] for SiO

2. The initial digits in the sample names (02, 06, 10) represent the number of methyl groups per silicon atom: 0.2, 0.6, and 1.0, respectively. The designation ’y’ denotes the MTEOS–TEOS copolymer, while ’w’ indicates the DEDMS–TEOS copolymer. In this context, MTEOS—methyltriethoxysilane, TEOS—tetraethoxysilane, DEDMS—diethoxydimethylsilane.

Table 2.

Quantitative analysis of FTIR spectra of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS).

Table 2.

Quantitative analysis of FTIR spectra of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS) or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS).

Sample

name |

Area under the absorption peak/band,

related to the broad band Si–O–Si

(×100) |

Network/Cage

ratio |

Si–OH,

H–O–H |

C–H |

C–H3

|

Si(–CH3)1,2

|

Si–OH |

| 02y |

5.14 |

0.93 |

0.33 |

0.70 |

0.44 |

3.8 |

| 02w |

9.57 |

1.02 |

0.37 |

0.37 |

0.75 |

4.0 |

| 06y |

0.64 |

2.02 |

1.23 |

2.91 |

0.02 |

2.3 |

| 06w |

1.22 |

2.08 |

1.23 |

1.65 |

0.09 |

4.1 |

| 10y |

0.54 |

3.53 |

2.34 |

5.75 |

- |

2.0 |

| 10w |

0.55 |

3.14 |

1.88 |

2.91 |

0.01 |

4.7 |

Table 3.

Main porosimetric parameters of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS)—designated as series ‘y’—or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS)—designated as series ‘w’.

Table 3.

Main porosimetric parameters of porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS)—designated as series ‘y’—or diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS)—designated as series ‘w’.

Sample

name |

d

(nm)

[±2] |

n

[±0.005] |

ns

[±0.005] |

Vopen

(%)

[±2] |

Vfull

(%)

[±2] |

|

Rads |

Rdes |

⟨Rads⟩ |

ΔmRads

|

EP YM

(GPa)

[±0.3] |

|

(nm)

[±0.1] |

| 02y |

465 |

1.221 |

1.472 |

50 |

49 |

0.4/1.1 |

0.4/1.1 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

5.7 |

| 02w |

453 |

1.238 |

1.471 |

46 |

46 |

0.4/1.1 |

0.4/1.1 |

0.8 |

0.6 |

6.6 |

| 06y |

558 |

1.238 |

1.436 |

42 |

46 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

2.5 |

| 06w |

547 |

1.261 |

1.444 |

38 |

41 |

0.4/1.3 |

0.4/1.3 |

1.3 |

0.7 |

4.2 |

| 10y |

507 |

1.269 |

1.421 |

34 |

39 |

2.8 |

1.9 |

2.7 |

2.8 |

0.8 |

| 10w |

402 |

1.282 |

1.431 |

32 |

36 |

1.5 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

Table 5.

Idealized speculative model of crosslinking for porous organosilica films prepared from tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) mixed with either methyltriethoxysilane (MTEOS)—designated as series ‘y’—or with diethoxydimethylsilane (DEDMS)—designated as series ‘w’—which vary in the number of methyl groups per silicon atom (CH3/Si ratio).