1. Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), which is characterized by abnormal blood vessel growth in the retina, is a significant cause of visual impairment in premature infants. This condition primarily arises due to the premature interruption of normal retinal vascular development and subsequent exposure to varying oxygen levels in neonatal care units [

1]. In severe cases, the abnormal proliferation and disruption of normal immature retinal blood vessel development can lead to retinal detachment and vision loss. Treatments such as retinal photocoagulation and intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) injections are effective in managing abnormal blood vessel growth [

2], but no currently available treatments can truly treat ROP by restoring the retinal vascular networks that have already become avascular [

1,

2,

3].

Oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) is a well-established animal model that closely replicates the pathogenesis of ROP [

4]. In this model, neonatal mice are exposed to hyperoxia followed by a return to normoxia, and this exposure leads to retinal vaso-obliteration and subsequent pathological neovascularization, mirroring the phases of vessel loss and aberrant proliferation observed in ROP. However, unlike in humans, the non-perfused areas and the associated neovascularization in mice recover with time, eventually returning to an almost normal state [

4].

Astrocytes are retinal glial cells that play a crucial role in the development and maintenance of retinal blood vessels [

5]. During retinal development, astrocytes migrate from the optic nerve head to the peripheral retina and provide a scaffold for endothelial cells to form new blood vessels by secreting VEGF, which stimulates angiogenesis and promotes the formation of a stable vascular network [

6]. Notably, this process is significantly influenced by oxygen levels. The astrocytes initially originate from precursor cells that express Pax2 under hypoxic conditions, which promote astrocyte migration and proliferation. As these precursor cells invade the retina, they proliferate rapidly and begin to express low levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) [

6]. Postnatally, they differentiate into immature astrocytes, laying the foundation for the retinal vasculature. As the retina further matures and vascularizes, astrocytes guide and stabilize developing blood vessels, preventing pathological neovascularization. Mature astrocytes, marked by strong GFAP immunoreactivity, then participate in vessel pruning and remodeling in response to oxygen levels, ensuring proper vascular formation and maintenance [

7].

Studies have shown that platelet-derived growth factor subunit A (PDGF-A) regulates astrocyte activity by promoting their proliferation and differentiation, thereby supporting normal angiogenesis, and thus playing a crucial role in the development of retinal blood vessels [

8]. PDGF-A signaling is essential for the survival and function of astrocytes, and its deficiency leads to the collapse of the retinal vascular network. Therefore, the balance between PDGF-A signaling, astrocyte activity, and vascular development is expected to be critical for the normal development of the retinal vascular network and potentially for the prevention of diseases characterized by vascular regression, such as ROP. Previous studies on transgenic mice overexpressing PDGF-A in the retina [

9,

10] have reported vascular regression following OIR and a reduction in tuft formation at postnatal day 17 (P17). However, the precise mechanisms underlying these phenomena have not been thoroughly explored.

In this study, we investigated the vascular regression following hyperoxic exposure in one of the abovementioned transgenic PDGF-A OIR models, focusing on the effects of PDGF-A on astrocytes and blood vessels and its role in astrocyte-mediated vascular stabilization. By comparing the transgenic and wild-type (WT) mice under the high-oxygen exposure OIR protocol as a model for ROP, we aimed to further understand the potential of PDGF-A as a therapeutic target for this condition.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Animals

Transgenic mice were obtained from the Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University [

9]. WT C57BL/6 mice were procured from CLEA Japan, Inc.

To prepare C57BL/6 background rho/PDGF-Atg mice, full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) for PDGF-AA was cloned into a plasmid with a 2.2 kb HindIII/NaeI fragment from the bovine rhodopsin promoter, an intron, a polyadenylic acid addition site derived from the mouse protamine gene, and a eukaryotic consensus ribosomal binding site. After transformation, a clone with the correct orientation was selected, the DNA was double CsCl-purified and cleaved using EcoRI to yield the 3546 bp fusion gene (

Figure 9).

To confirm the transgenic status, presumptive rho/PDGF-Atg mice were crossed with WT C57BL/6 mice, and the offspring litters were genotyped using PCR of tail DNA. Briefly, tail pieces were digested overnight at 55 °C in a solution containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM EDTA, 400 mM NaCl, 0.5% SDS, and 0.6 g/L Proteinase K. PCR was performed at 58 °C using the primers P1 (5'-GTCCAGCCGGAGCCCCGTG-3') and P2 (5'-TGGCACTTGACACTGCTCGTGTTG-3'), which amplify a 580 bp transgene-specific sequence. Transgenic parents were considered confirmed rho/PDGF-Atg mice if all offspring litters were transgene-positive.

These animals were housed in the Kansai Medical University animal experimentation facility within isolators at a temperature of 22±3 °C and 60% humidity. The lighting conditions consisted of 12 h of dark (less than 10 lux) followed by 12 h of light (approximately 50 lux). To minimize and eliminate pain, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection containing 0.3 mL/kg of Ceractar® (Bayer, Berlin, Germany) and Ketalar® (Daiichi Sankyo Co., Tokyo, Japan) (50 mg/mL ketamine and 5 mg/mL xylazine). Euthanasia was performed using the cervical dislocation method to ensure central destruction. This study involving the use of mice was conducted in accordance with ethical standards and guidelines for animal experimentation and was duly approved by the Ethics Committee of Kansai Medical University (approval number 24-034).

4.2. OIR Model

Retinal vascular obliteration was induced using a well-established method [

4]. Briefly, P7 mice were exposed to 75% oxygen for 5 days, followed by a return to room air for 5 days to mimic the fluctuating oxygen levels encountered during ROP. Typically, proliferative neovascularization in this model is assessed on P17; however, as we focused on the vascular regression occurring during high oxygen exposure int his study, the mice were sacrificed on P12, i.e., 5 days after high oxygen exposure, to obtain samples for specifically examining the effects of hyperoxia on vascular obliteration.

4.3. Sample Collection

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, a method approved by our institutional animal care and use committee, and the eyeballs were carefully enucleated immediately to avoid retinal damage.

4.4. Western Blotting

Retinal tissues were collected and homogenized in ice-cold UltraRIPA® Kit for Lipid Raft (BioDynamics Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan) solution supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) to prepare total protein lysates. The homogenates were centrifuged at 20,000× g for 15 minutes at 4 °C to remove debris and obtain the supernatant. Protein concentration in the supernatant samples was determined using a BCA kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Thereafter, equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from each sample were mixed with Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) containing β-mercaptoethanol (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 10% polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a PVDF membrane using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Membranes were blocked using EveryBlot Blocking Buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies specific to the target proteins diluted in the same blocking buffer. The primary antibodies used in this study are as follows: anti-PDGF-A (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA; Cat# sc-9974; mouse monoclonal) and anti-β-actin (1:3000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; Cat# 4970S; rabbit monoclonal). β-actin was used as the loading control. Following primary antibody incubation, the membranes were washed three times in TBS-T and then incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:10000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then washed again and developed using the ImmunoStar LD chemiluminescence detection kit (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Protein bands were visualized using a Fusion Solo imaging system (Vilber Lourmat, Collégien, France). Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), with protein expression levels normalized to that of β-actin.

4.5. Immunofluorescence Analysis of Whole-Mount Retinas

After enucleation, eyeballs were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h. The cornea and the lens were carefully removed to expose the retina, which was gently separated from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium using fine microsurgical tools. To ensure optimal preservation of retinal architecture, the isolated retina was re-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C.

Immunofluorescent staining of the retinas was performed using the following primary antibodies: anti-Pax2 (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; Cat# ab79389, rabbit monoclonal), anti-GFAP (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; Cat# ab279291, rat monoclonal), anti-CD31 (1:500; BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA, USA; Cat# 550274, rat monoclonal), anti-NG2 (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; Cat# ab259324, rabbit polyclonal), and anti-PDGFRα (1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK; Cat# ab203491, rabbit polyclonal). The cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C. Following primary antibody incubation, the retinas were treated with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor® 488 and Alexa Fluor® 546 (1:800, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 3 hours at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were selected based on the host species of primary antibodies. During the secondary antibody incubation, simultaneous 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining was performed to label the cell nuclei.

After antibody incubation, the retinas were washed three times in PBS for 30 min each with gentle rocking. The retinas were carefully spread on a glass slide to ensure that they lay flat, with the photoreceptor side facing downward. Finally, the retinas were whole-mounted in ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.6. Immunofluorescence Analysis of Frozen Retinal Sections

To prepare the frozen retinal sections, eyeballs from the mice were immediately embedded in OCT compound (Sakura, Tokyo, Japan) for cryopreservation. During the embedding process, ink marks were made on the eyeballs to ensure clear identification of the superior and inferior poles. The embedded eyeballs were sectioned into 8 μm thick slices using a cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany), and the sections were carefully placed on MAS-coated glass slides (Matsunami Glass Ind., Ltd., Kishiwada, Japan). For the immunostaining for PDGF-A and vascular structure, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies, including anti-PDGF-A (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA, Cat# sc-9974; mouse monoclonal) and anti-CD31 (1:500; BD Pharmingen™, San Jose, CA, USA; Cat# 550274; rat monoclonal) overnight at 4 ℃. After primary antibody incubation, the sections were treated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated; 1:800 dilution; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. During the secondary antibody incubation, DAPI staining (Cellstain DAPI Solution; FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was performed simultaneously to label the cell nuclei. Following the staining process, the sections were mounted using ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.7. Fluorescein Visualization of Retinal Vasculature

Mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of 0.3 mL/kg of Ceractar® (Bayer, Berlin, Germany) and Ketalar® (Daiichi Sankyo Co., Tokyo, Japan) (50 mg/mL ketamine and 5 mg/mL xylazine). Following deep anesthesia, fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextran (FITC-Dextran, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA; average molecular weight, 4,000) was administered via cardiac perfusion using a syringe after thoracotomy to expose the heart. This procedure ensured thorough circulation of fluorescein throughout the body. The eyes were enucleated after perfusion, the enucleated eyeballs were immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h, and the cornea and the lens were carefully removed to expose the retina. The retina was gently separated from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium using fine microsurgical tools, and the isolated retina was then re-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4 °C to ensure optimal preservation of the retinal architecture. Thereafter, the retinas were flat-mounted on glass slides with the photoreceptor side facing down and covered with ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

4.8. Image Acquisition and Analysis

The FV3000 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for confocal microscopy. Image acquisition settings, including exposure time, gain, and pinhole size, were standardized across all samples to ensure the comparability and reproducibility of the results. Care was taken to avoid overexposure or underexposure as a possible reason for loss of detail or increased background noise, respectively.

Image analysis was performed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). For each image, regions of interest (ROIs) were defined, and fluorescence intensity within these areas was automatically measured using the software.

Total vascular length was measured using AngioTool [

19] following the protocol outlined for vascular network quantification.

4.9. Statistical Analysis

To compare PDGF-A expression using western blotting analysis, three separate mice from each group (WT and PDGF-Atg) were analyzed using the aforementioned methods.

Additionally, the total GFAP, Pax2, and PDGFRα expression areas as well as the total vascular area and total vascular length were compared. Each group had 10 mice, and one retina was collected from each mouse. Retinal measurements were obtained from 10 randomly selected peripheral regions, and the average of these measurements was used for the analysis.

Eleven mice were used in each group to compare ischemic areas after OIR. One retina was collected from each mouse and analyzed. Therefore, "n" in the figures and tables represents the number of mice.

Since this study does not involve observing temporal changes, no specific criteria were established for excluding animals or data points. However, in cases where fundamental experimental conditions were not met, such as failure to properly regulate oxygen concentration, data exclusion was considered. No data were ultimately excluded.

To evaluate the differences between groups, independent two-sample t-tests (two-tailed) were performed for each parameter. Welch’s t-test was used to account for differences in variance. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using JMP® (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

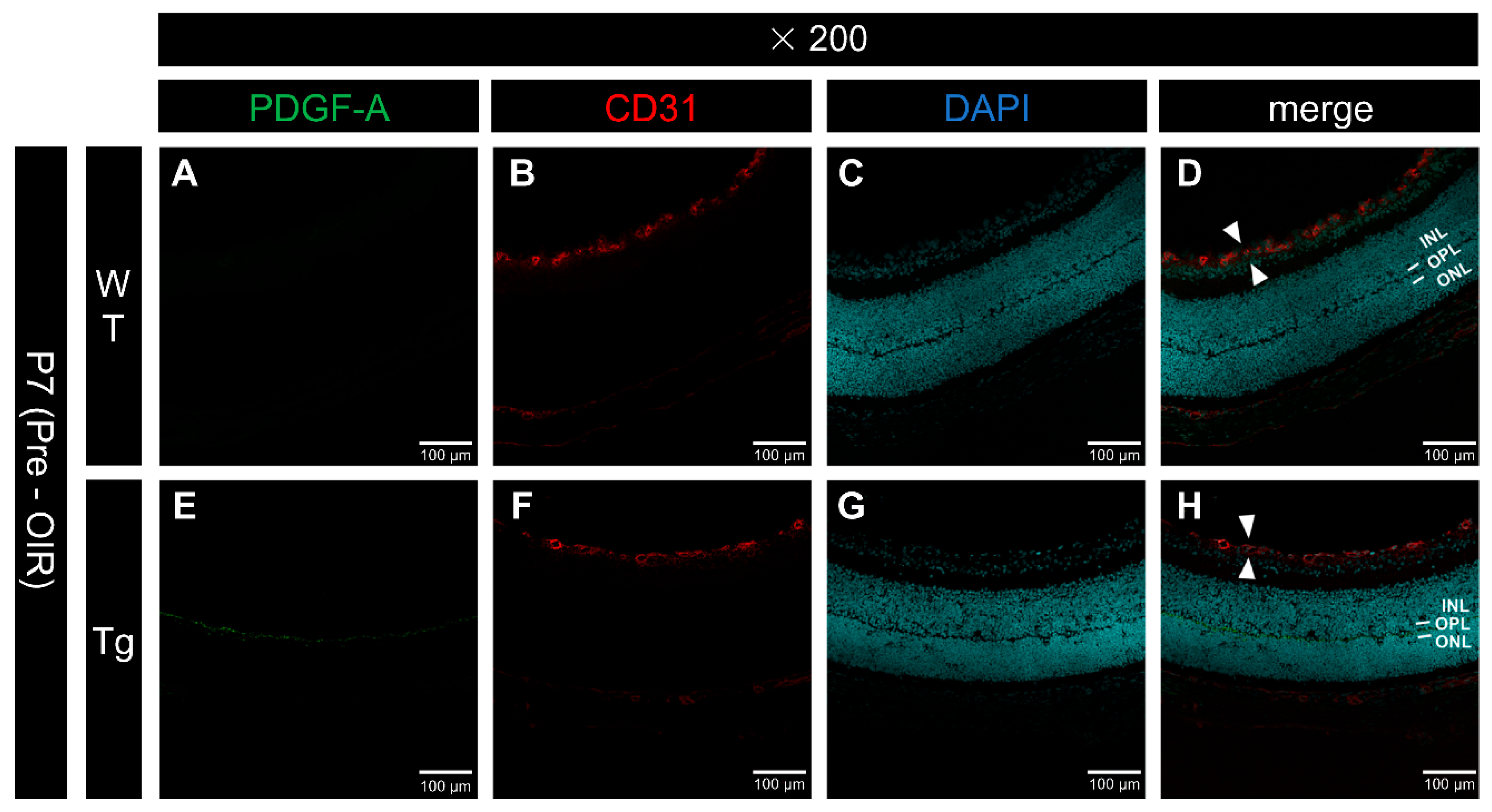

Figure 1.

Confocal images of frozen sections of eyes from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice imunostained with anti-PDGF-A (green) and anti-CD31 (red) antibodies and DAPI (blue). (a-d) WT mouse retina; (e-h) Retinas from genetically modified mice. Scale bars = 100 μm, 200x); (a and e) PDGF-A antibody staining; (b and f) CD31 staining; (c and g) DAPI; (d and h) Merged images. No clear PDGF-A expression is observable in the WT retina (a, d), whereas PDGF-A expression is observed in the outer plexiform layer (OPL), which corresponds to the inner segment of the rhodopsin-producing photoreceptor, in genetically modified mice (e, h). In both wild-type (white arrow in d) and genetically modified (white arrow in h) mice, blood vessels (CD31) were observed only in the superficial layer of the retina, with no differences in the vascular layer structure.

Figure 1.

Confocal images of frozen sections of eyes from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice imunostained with anti-PDGF-A (green) and anti-CD31 (red) antibodies and DAPI (blue). (a-d) WT mouse retina; (e-h) Retinas from genetically modified mice. Scale bars = 100 μm, 200x); (a and e) PDGF-A antibody staining; (b and f) CD31 staining; (c and g) DAPI; (d and h) Merged images. No clear PDGF-A expression is observable in the WT retina (a, d), whereas PDGF-A expression is observed in the outer plexiform layer (OPL), which corresponds to the inner segment of the rhodopsin-producing photoreceptor, in genetically modified mice (e, h). In both wild-type (white arrow in d) and genetically modified (white arrow in h) mice, blood vessels (CD31) were observed only in the superficial layer of the retina, with no differences in the vascular layer structure.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of retinal tissue showing PDGF-A expression in WT (n=3) and genetically modified (Tg; n=3) mice at P7 (normalized to β-actin). WT retinas showed no detectable PDGF-A expression, while Tg retinas showed detectable PDGF-A expression (n = 3, p = 0.0032 < 0.05), indicating a significant difference between the groups. The bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) values.

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of retinal tissue showing PDGF-A expression in WT (n=3) and genetically modified (Tg; n=3) mice at P7 (normalized to β-actin). WT retinas showed no detectable PDGF-A expression, while Tg retinas showed detectable PDGF-A expression (n = 3, p = 0.0032 < 0.05), indicating a significant difference between the groups. The bars represent the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) values.

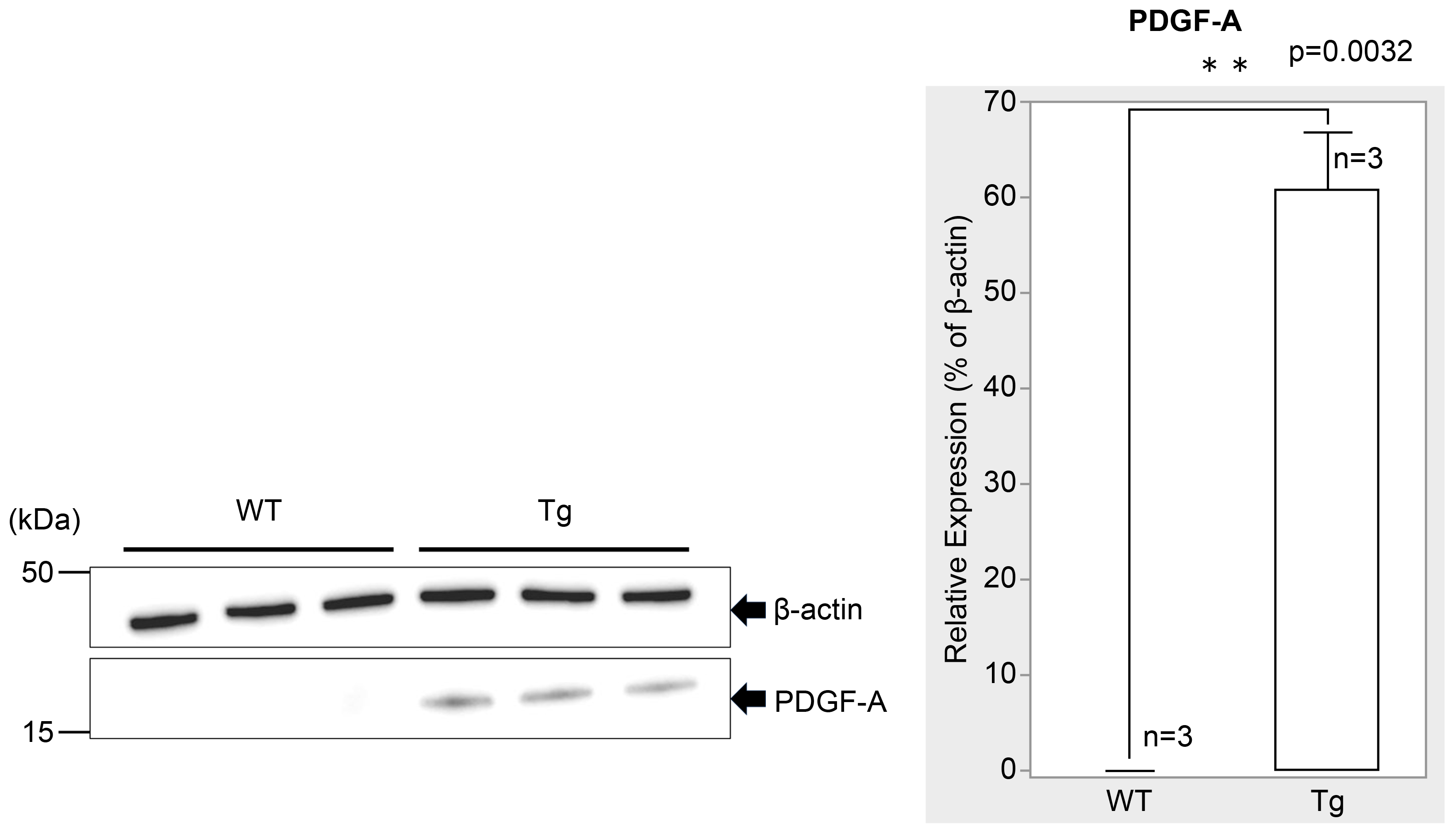

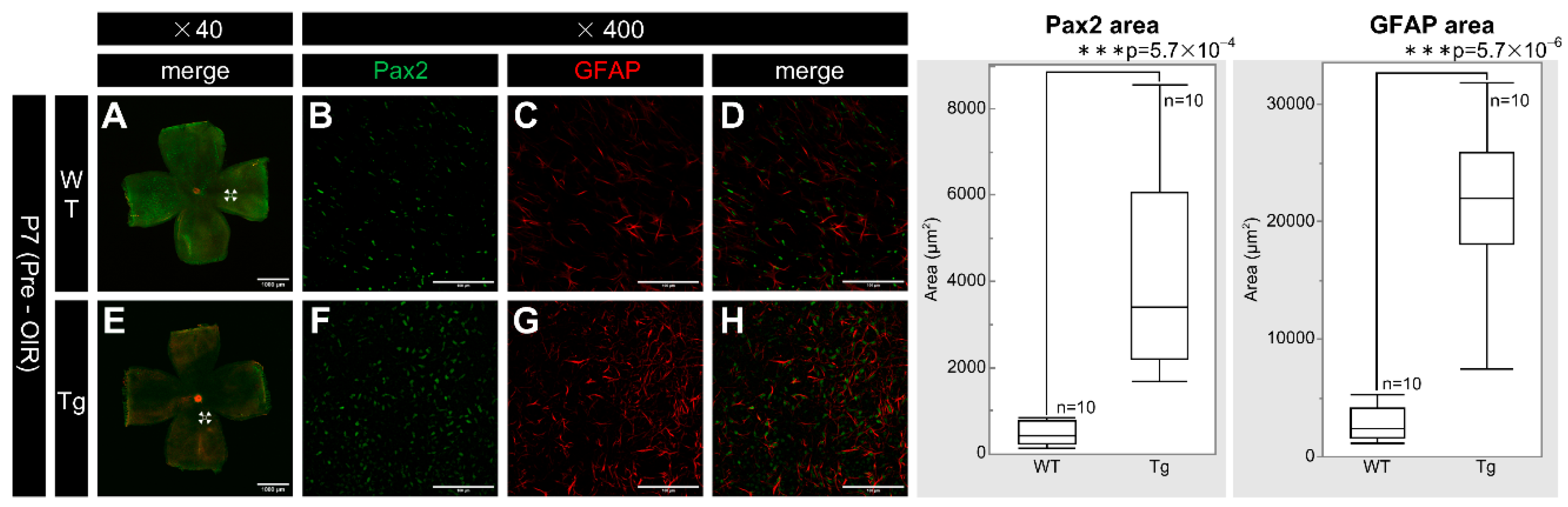

Figure 3.

Confocal images of whole-mount retinas from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained for Pax2 (green) and GFAP (red) alongside a comparative box plot analysis. (a-d) Confocal images of WT retinas; (b-d) (Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice; (f-h) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). (a and e) Composite low-magnification images of staining for Pax2 and GFAP, respectively; (b and f) immunostaining with the Pax2 antibody; (c and g) immunostaining with the GFAP antibody; d is a combination of b and c; and h is a combination of f and g. In the retinas, Pax2 expression was increased in PDGF-A transgenic mice (f) compared to that in WT mice (b) (n = 10, p = 5.7 × 10-4 < 0.05). Similarly, GFAP expression was also increased in PDGF-A transgenic mice (g) compared to that in WT mice (c) (n = 10, p = 5.7 × 10-6 < 0.05). The corresponding box plot analysis, positioned adjacent to the images, illustrates the statistical comparisons. Retinal and statistical analyses were conducted as described in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice.

Figure 3.

Confocal images of whole-mount retinas from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained for Pax2 (green) and GFAP (red) alongside a comparative box plot analysis. (a-d) Confocal images of WT retinas; (b-d) (Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice; (f-h) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). (a and e) Composite low-magnification images of staining for Pax2 and GFAP, respectively; (b and f) immunostaining with the Pax2 antibody; (c and g) immunostaining with the GFAP antibody; d is a combination of b and c; and h is a combination of f and g. In the retinas, Pax2 expression was increased in PDGF-A transgenic mice (f) compared to that in WT mice (b) (n = 10, p = 5.7 × 10-4 < 0.05). Similarly, GFAP expression was also increased in PDGF-A transgenic mice (g) compared to that in WT mice (c) (n = 10, p = 5.7 × 10-6 < 0.05). The corresponding box plot analysis, positioned adjacent to the images, illustrates the statistical comparisons. Retinal and statistical analyses were conducted as described in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice.

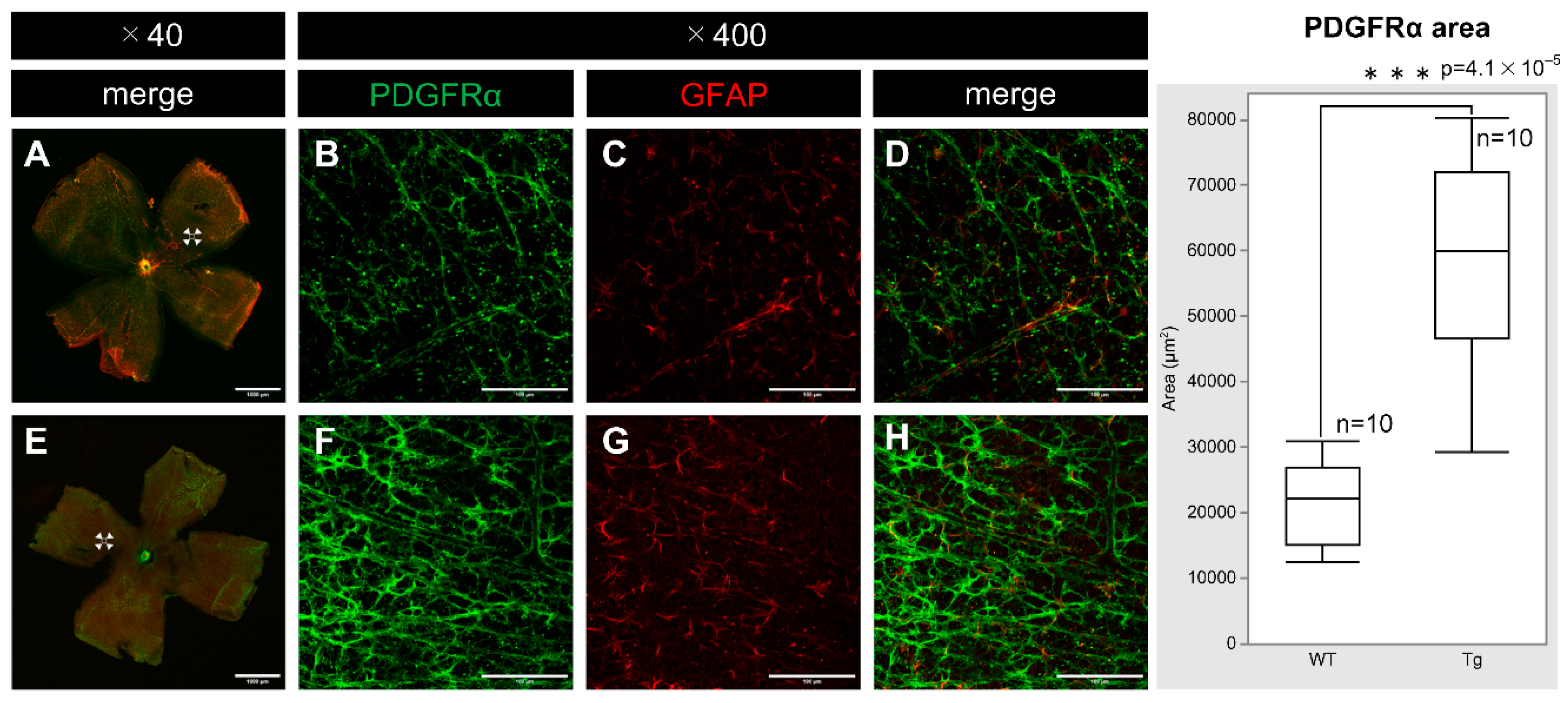

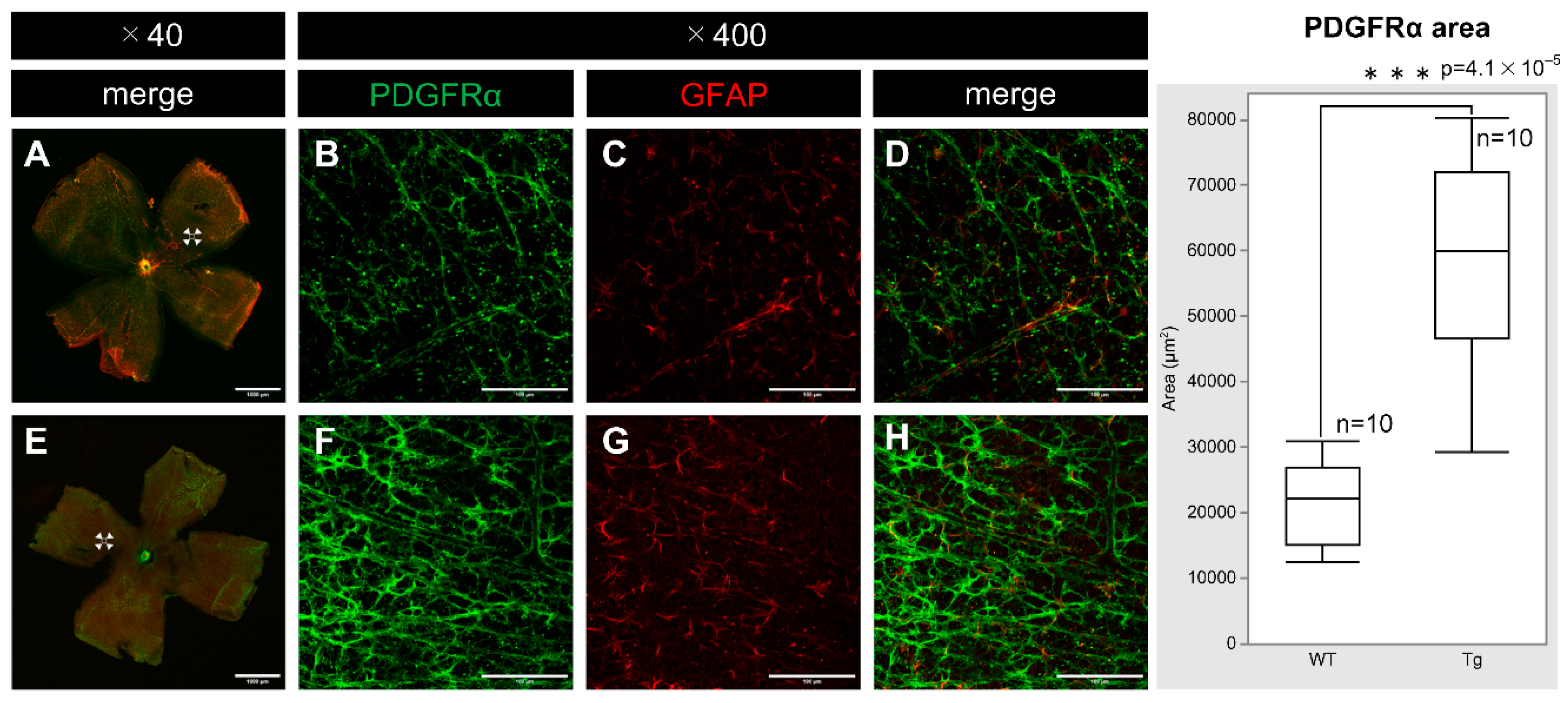

Figure 4.

Confocal images of whole-mount of the retinas from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained for PDGFRα (green) and GFAP (red) antibody, alongside a comparative box plot analysis. (a-d) Confocal images of wild-type mice; (b-d) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice. (f-h) Scale bar = 100 μm); enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). a and e are composite low-magnification images stained with PDGFRα and GFAP. b and f show immunostaining with PDGFRα antibody, c and g show immunostaining with GFAP antibody, and d is a merge of b and c, while h is a merge of f and g. In the retinas, PDGFRα expression was increased in PDGF-A transgenic mice (f) compared to that in WT mice (b) (n = 10, p = 4.1 × 10-5 < 0.05). The corresponding box plot analysis, positioned adjacent to the images, illustrates the statistical comparisons. Retinal and statistical analyses were conducted as described in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice.

Figure 4.

Confocal images of whole-mount of the retinas from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained for PDGFRα (green) and GFAP (red) antibody, alongside a comparative box plot analysis. (a-d) Confocal images of wild-type mice; (b-d) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice. (f-h) Scale bar = 100 μm); enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). a and e are composite low-magnification images stained with PDGFRα and GFAP. b and f show immunostaining with PDGFRα antibody, c and g show immunostaining with GFAP antibody, and d is a merge of b and c, while h is a merge of f and g. In the retinas, PDGFRα expression was increased in PDGF-A transgenic mice (f) compared to that in WT mice (b) (n = 10, p = 4.1 × 10-5 < 0.05). The corresponding box plot analysis, positioned adjacent to the images, illustrates the statistical comparisons. Retinal and statistical analyses were conducted as described in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice.

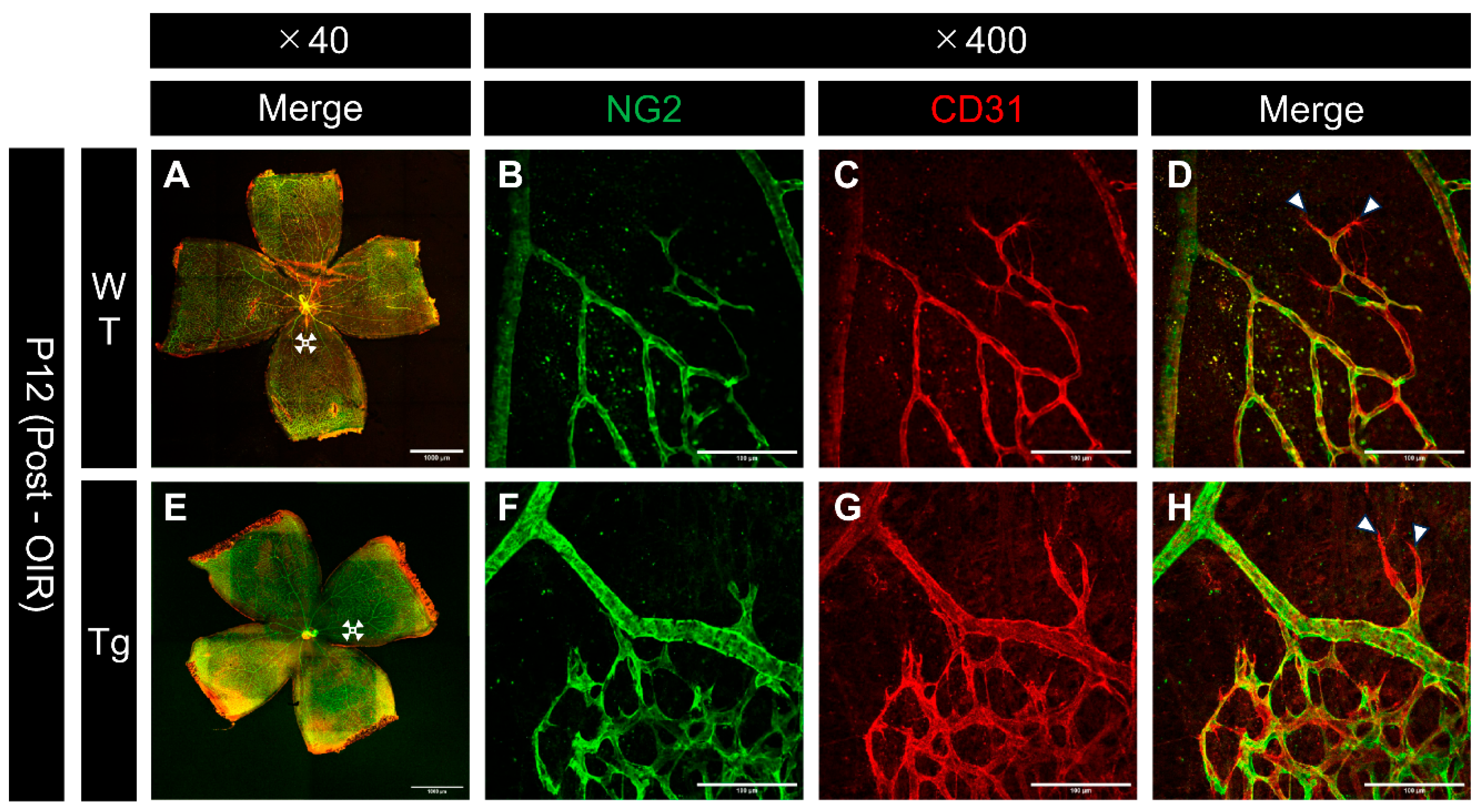

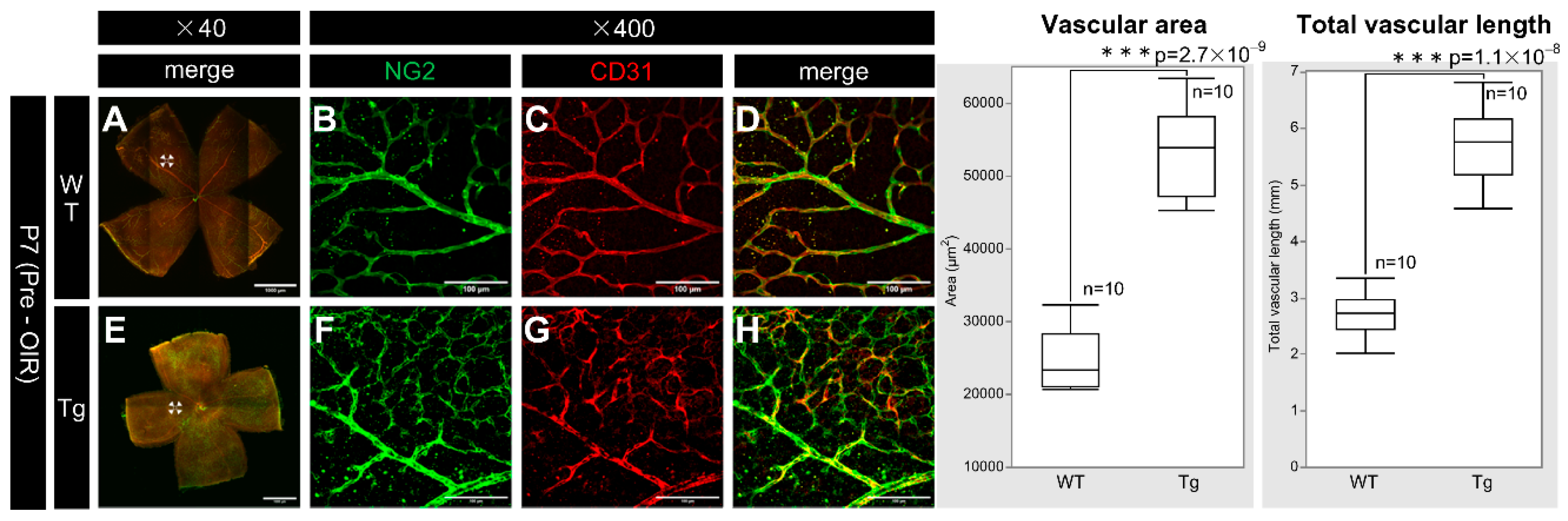

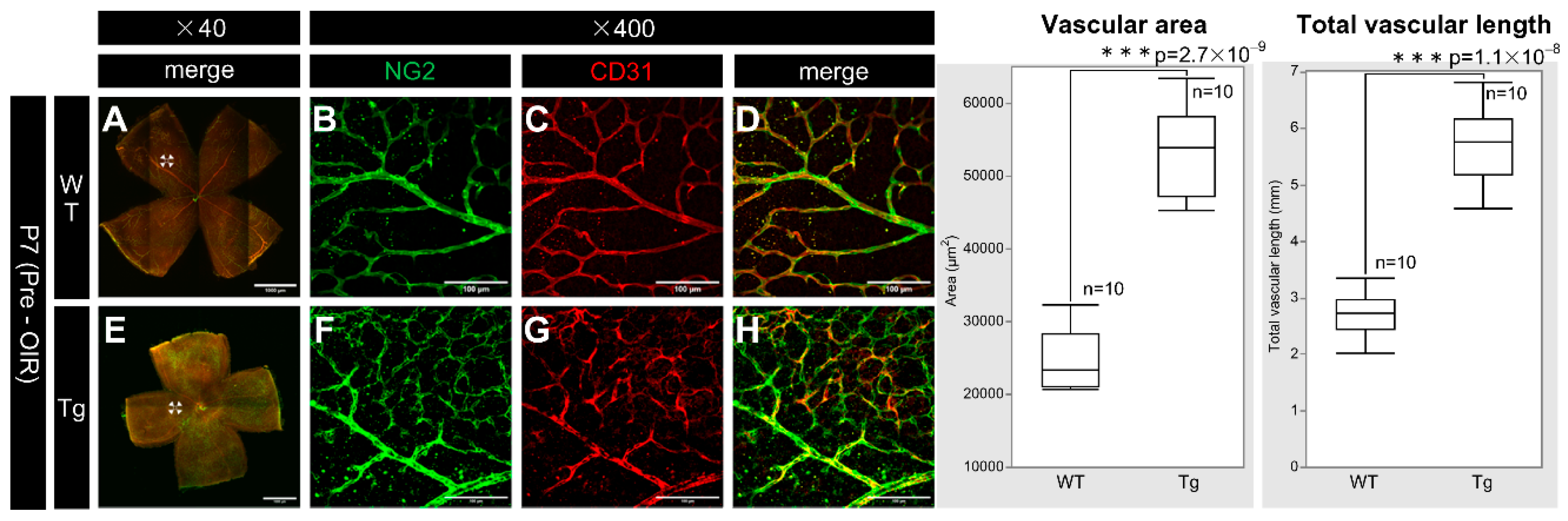

Figure 5.

Confocal images of whole-mount of the retinas from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained with anti-NG2 (green) and anti-CD31 (red) antibody, alongside a comparative box plot analysis. (a-d) Confocal images of wild-type mice. (b-d) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice. (f-h) scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). a and e show composite low-magnification images stained with NG2 and CD31, respectively. b and f show immunostaining with NG2 antibody, c and g show immunostaining with CD31 antibody, d is a combination of b and c, and h is a combination of f and g. In the retinas of PDGF-A transgenic mice, the expression of the vascular markers NG2 and CD31 was increased (f, g) compared to wild-type mice (b, c). Both CD31 and NG2 are components of the vascular structure, indicating increased vascular density (n = 10, p = 2.7 × 10-9 < 0.05) and length (n = 10, p = 1.1 × 10-8 < 0.05) in the retinas of the transgenic mice. The corresponding box plot analysis, positioned adjacent to the images, illustrates the statistical comparisons. Retinal and statistical analyses were conducted as described in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice.

Figure 5.

Confocal images of whole-mount of the retinas from P7 WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained with anti-NG2 (green) and anti-CD31 (red) antibody, alongside a comparative box plot analysis. (a-d) Confocal images of wild-type mice. (b-d) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice. (f-h) scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). a and e show composite low-magnification images stained with NG2 and CD31, respectively. b and f show immunostaining with NG2 antibody, c and g show immunostaining with CD31 antibody, d is a combination of b and c, and h is a combination of f and g. In the retinas of PDGF-A transgenic mice, the expression of the vascular markers NG2 and CD31 was increased (f, g) compared to wild-type mice (b, c). Both CD31 and NG2 are components of the vascular structure, indicating increased vascular density (n = 10, p = 2.7 × 10-9 < 0.05) and length (n = 10, p = 1.1 × 10-8 < 0.05) in the retinas of the transgenic mice. The corresponding box plot analysis, positioned adjacent to the images, illustrates the statistical comparisons. Retinal and statistical analyses were conducted as described in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice.

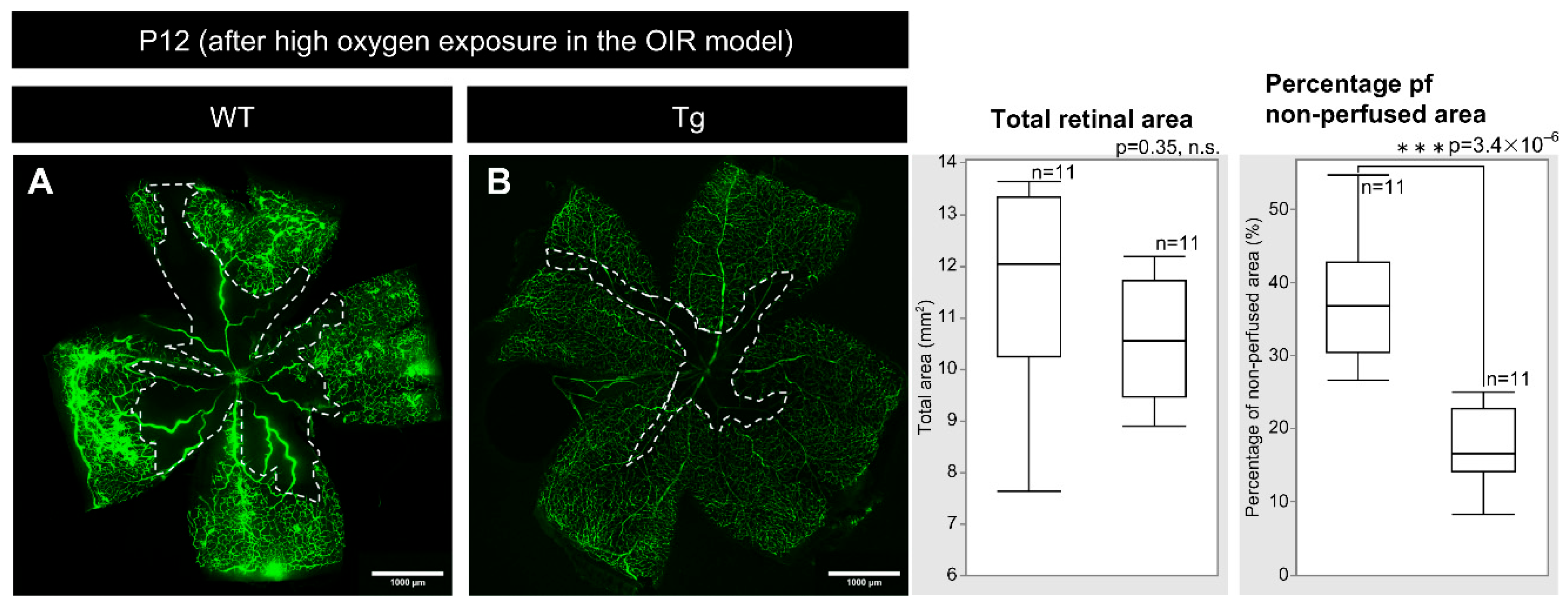

Figure 6.

Images of whole-mount retinas taken after fluorescein perfusion from P12 (after high oxygen exposure) WT and PDGF-Atg mice (scale bar = 1000 μm) alongside comparative box plot analysis. The areas outlined by the white dashed lines indicate the regions of retinal vascular regression, which were analyzed automatically using ImageJ software. Adjacent to the images, a table and box plot analysis were used to compare the total retinal area and non-perfused retinal area between the wild-type and PDGF-A transgenic mice. Whole-mount retinal fluorescein-staining shows a reduced vascular regression area after high oxygen exposure in PDGF-A transgenic mice compared to wild-type mice (n = 11, p = 3.4×10−6). Statistical analysis was performed as detailed in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice analyzed.

Figure 6.

Images of whole-mount retinas taken after fluorescein perfusion from P12 (after high oxygen exposure) WT and PDGF-Atg mice (scale bar = 1000 μm) alongside comparative box plot analysis. The areas outlined by the white dashed lines indicate the regions of retinal vascular regression, which were analyzed automatically using ImageJ software. Adjacent to the images, a table and box plot analysis were used to compare the total retinal area and non-perfused retinal area between the wild-type and PDGF-A transgenic mice. Whole-mount retinal fluorescein-staining shows a reduced vascular regression area after high oxygen exposure in PDGF-A transgenic mice compared to wild-type mice (n = 11, p = 3.4×10−6). Statistical analysis was performed as detailed in the Methods section, with n representing the number of mice analyzed.

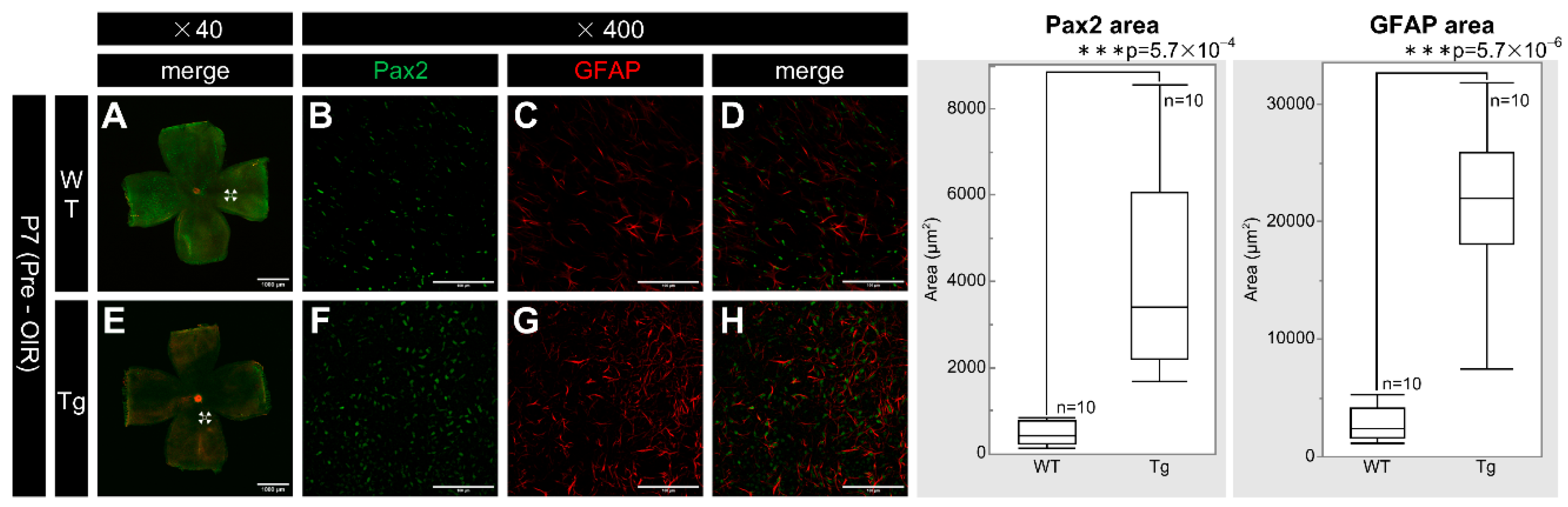

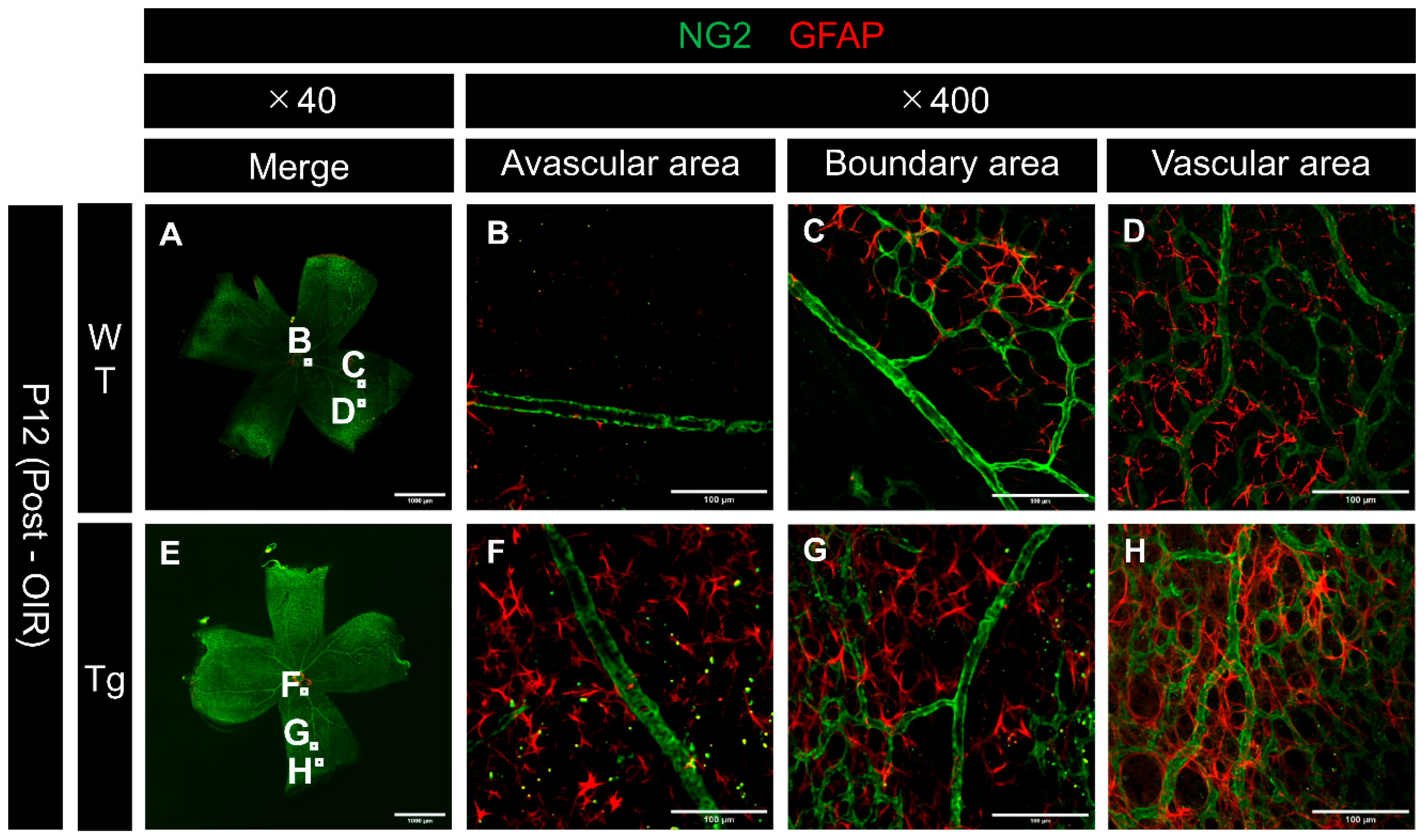

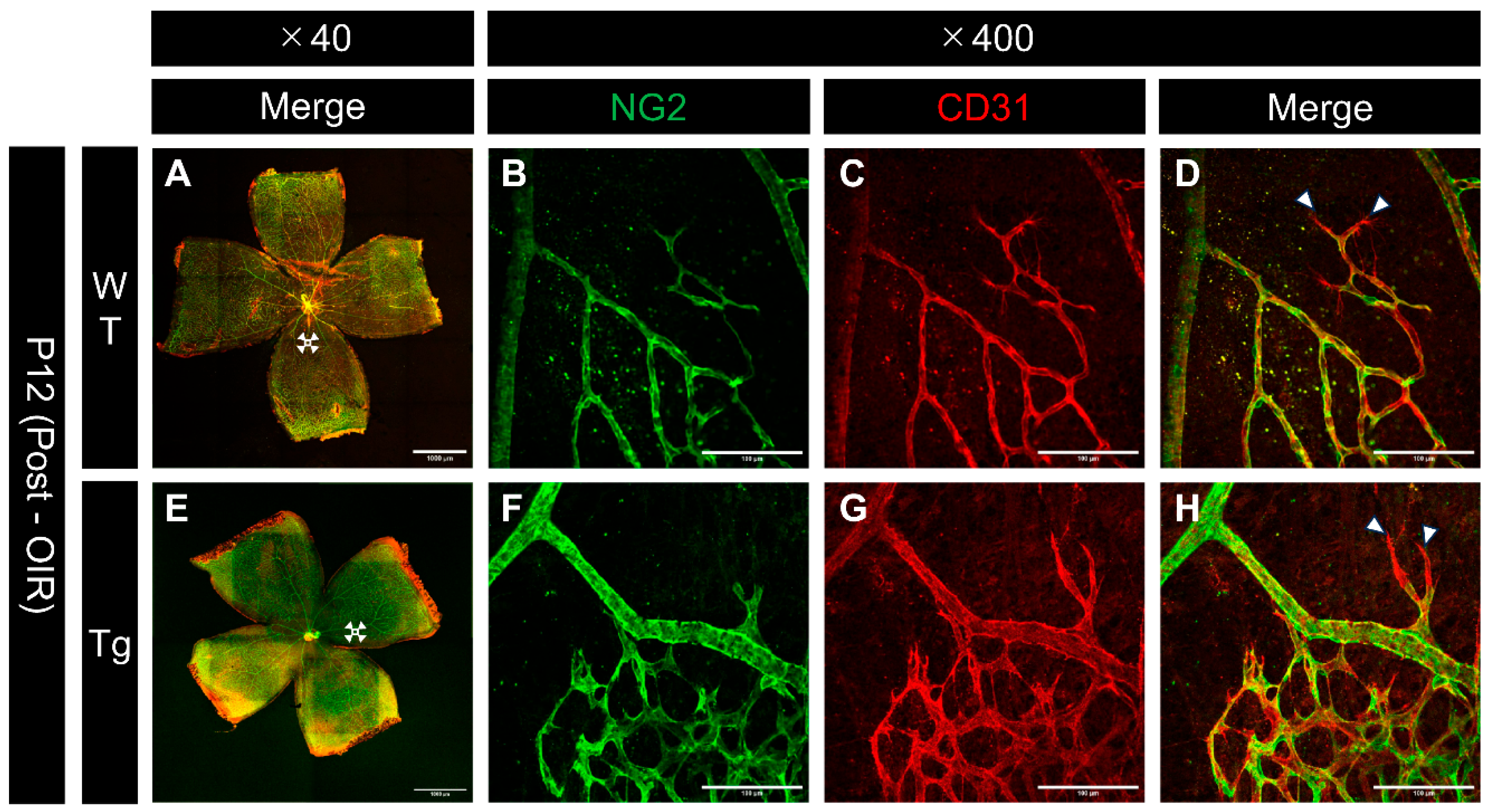

Figure 7.

Confocal images of whole-mount retinas from P12 (after high oxygen exposure in the OIR model) WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained with anti-NG2 (green) and anti-GFAP (red) antibody. (a-d) Confocal images of wild-type mice. (b-d) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice. (f-h) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). (b-d and f-h) Images of a single major vein extending from the optic disc, capturing the non-perfused area (b, f), vascular area (d, h), and boundary area between them (c, g). Comparison of astrocyte (GFAP) expression in the non-perfused regions revealed low expression in wild-type mice (b) but relatively retained expression in PDGF-A transgenic mice (f). Similar trends were observed in the border regions (c,g). In the vascularized areas (d,h), both retained GFAP expression.

Figure 7.

Confocal images of whole-mount retinas from P12 (after high oxygen exposure in the OIR model) WT and PDGF-Atg mice immunostained with anti-NG2 (green) and anti-GFAP (red) antibody. (a-d) Confocal images of wild-type mice. (b-d) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in a (scale bar = 1000 μm). (e-h) Images of PDGF-A transgenic mice. (f-h) Scale bar = 100 μm; enlarged images of the area outlined in e (scale bar = 1000 μm). (b-d and f-h) Images of a single major vein extending from the optic disc, capturing the non-perfused area (b, f), vascular area (d, h), and boundary area between them (c, g). Comparison of astrocyte (GFAP) expression in the non-perfused regions revealed low expression in wild-type mice (b) but relatively retained expression in PDGF-A transgenic mice (f). Similar trends were observed in the border regions (c,g). In the vascularized areas (d,h), both retained GFAP expression.

Figure 9.

Schematic map of the rhodopsin/PDGF-A fusion gene. P1 and P2, oligonucleotide primers used to screen genomic DNA for the transgene; P3 and P4, primers used for RT-PCR; + 1, transcription start site [

9].

Figure 9.

Schematic map of the rhodopsin/PDGF-A fusion gene. P1 and P2, oligonucleotide primers used to screen genomic DNA for the transgene; P3 and P4, primers used for RT-PCR; + 1, transcription start site [

9].

Table 1.

Total Retinal Area and Non-Perfused Area in P12 WT and PDGF-A Transgenic Mice After High Oxygen Exposure in the OIR Model.

Table 1.

Total Retinal Area and Non-Perfused Area in P12 WT and PDGF-A Transgenic Mice After High Oxygen Exposure in the OIR Model.

| |

WT (n=11) |

Tg (n=11) |

| Total retinal area (mm²) |

11.39 ± 1.96 |

10.74 ± 1.11 |

| Non-perfused area (mm²) |

4.16 ± 0.93 |

1.80 ± 0.52 |

| Percentage of non-perfused area (mm²) |

37.10 ± 8.34 |

16.97 ± 5.30 |