Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

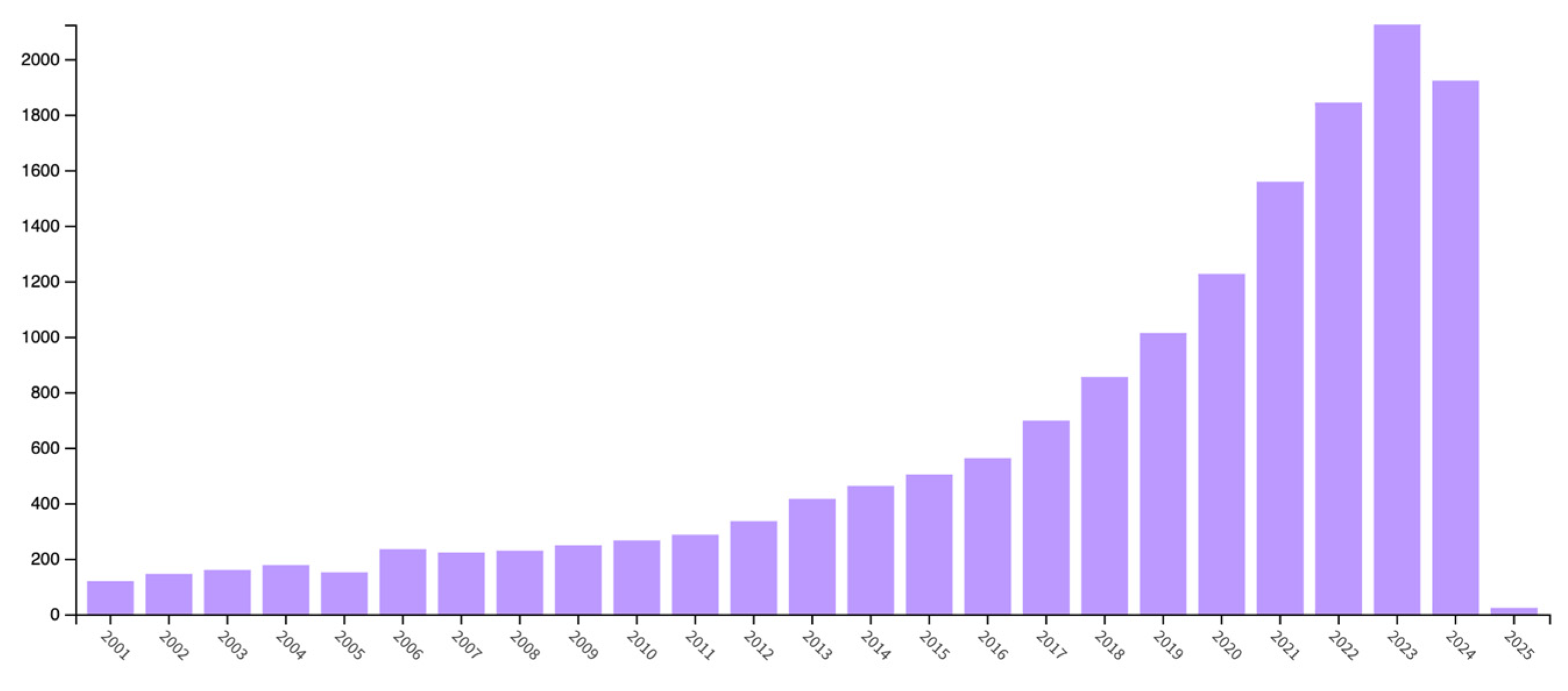

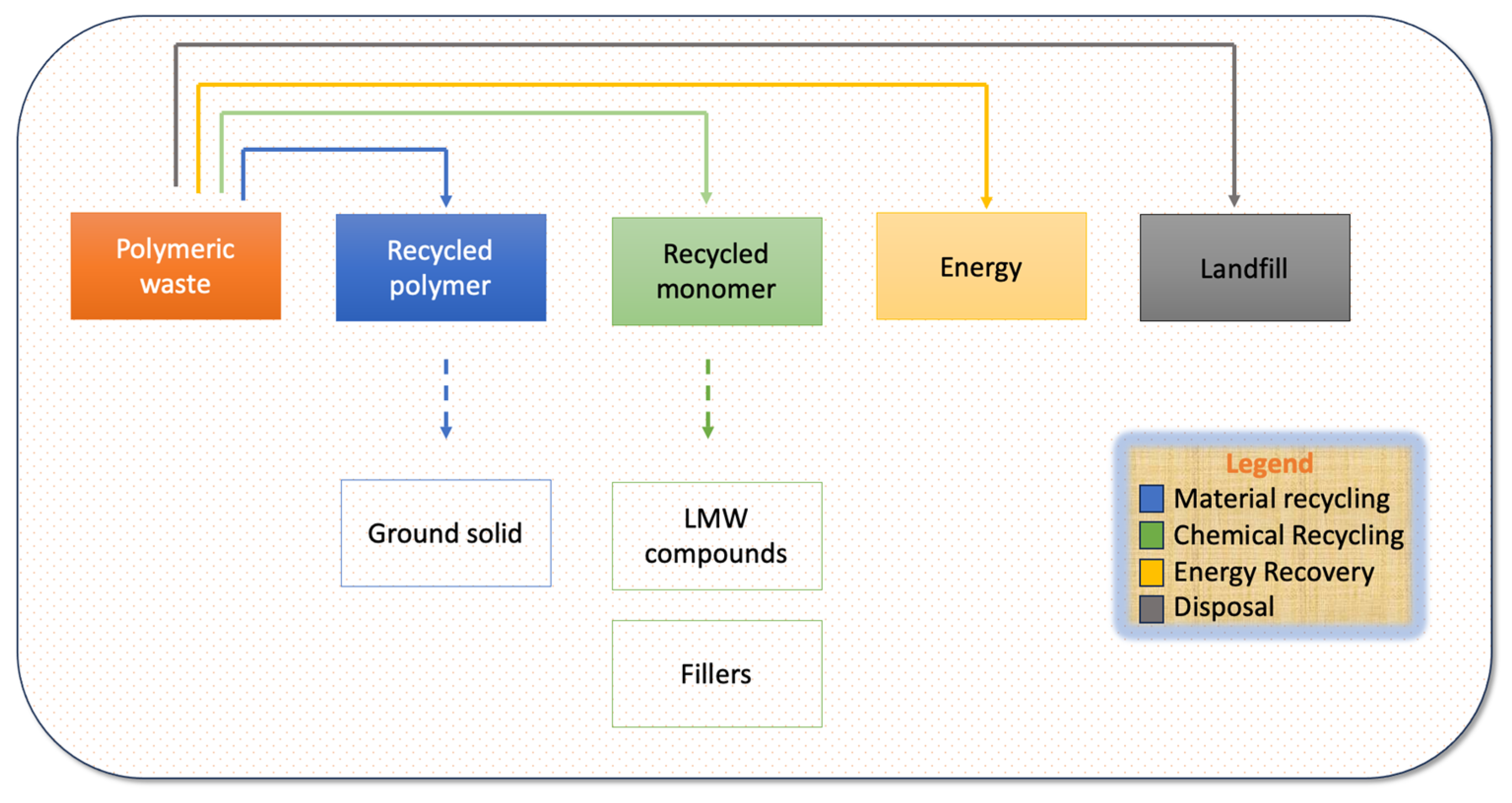

1. General Definitions and Aim of This Work

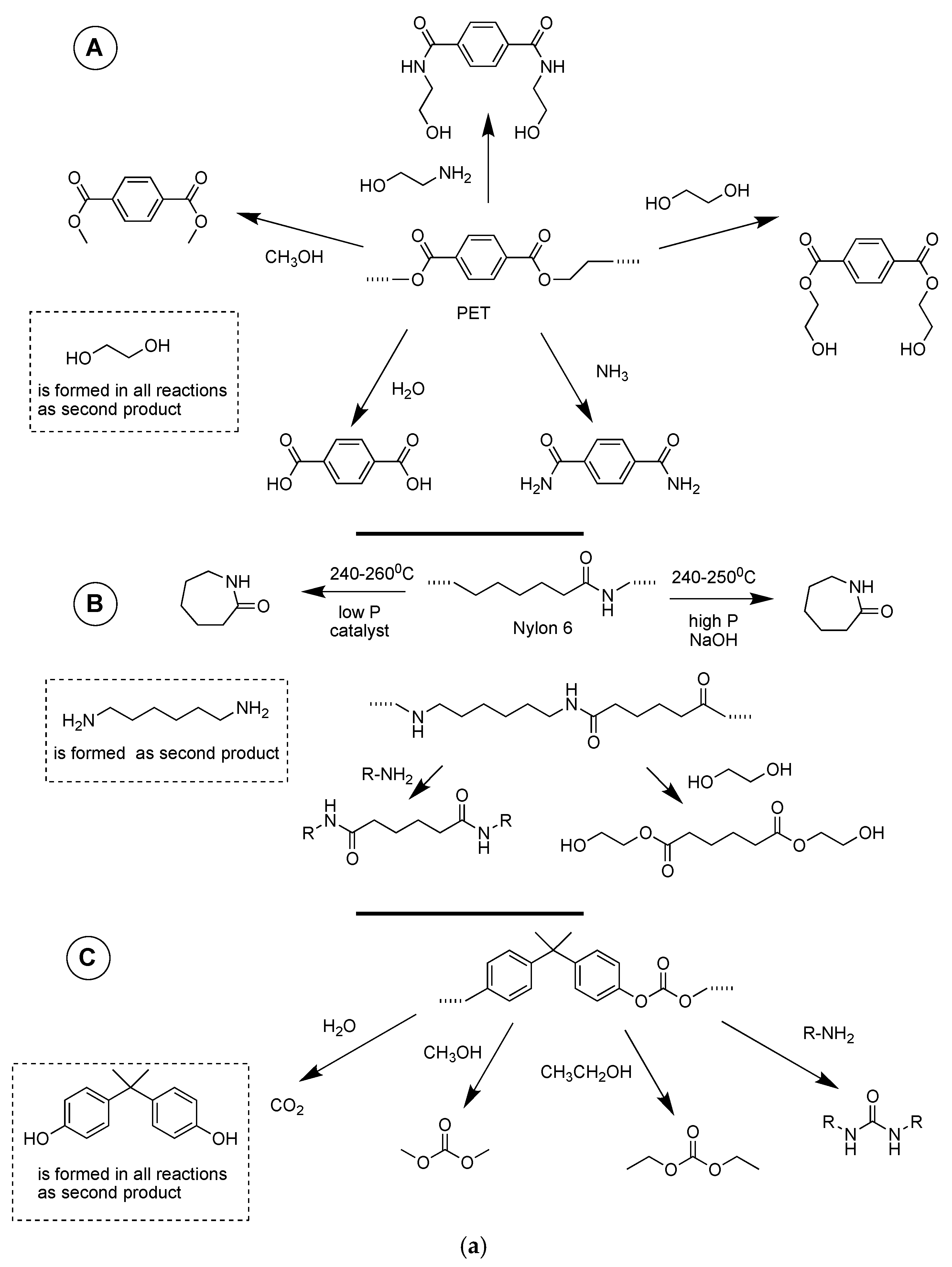

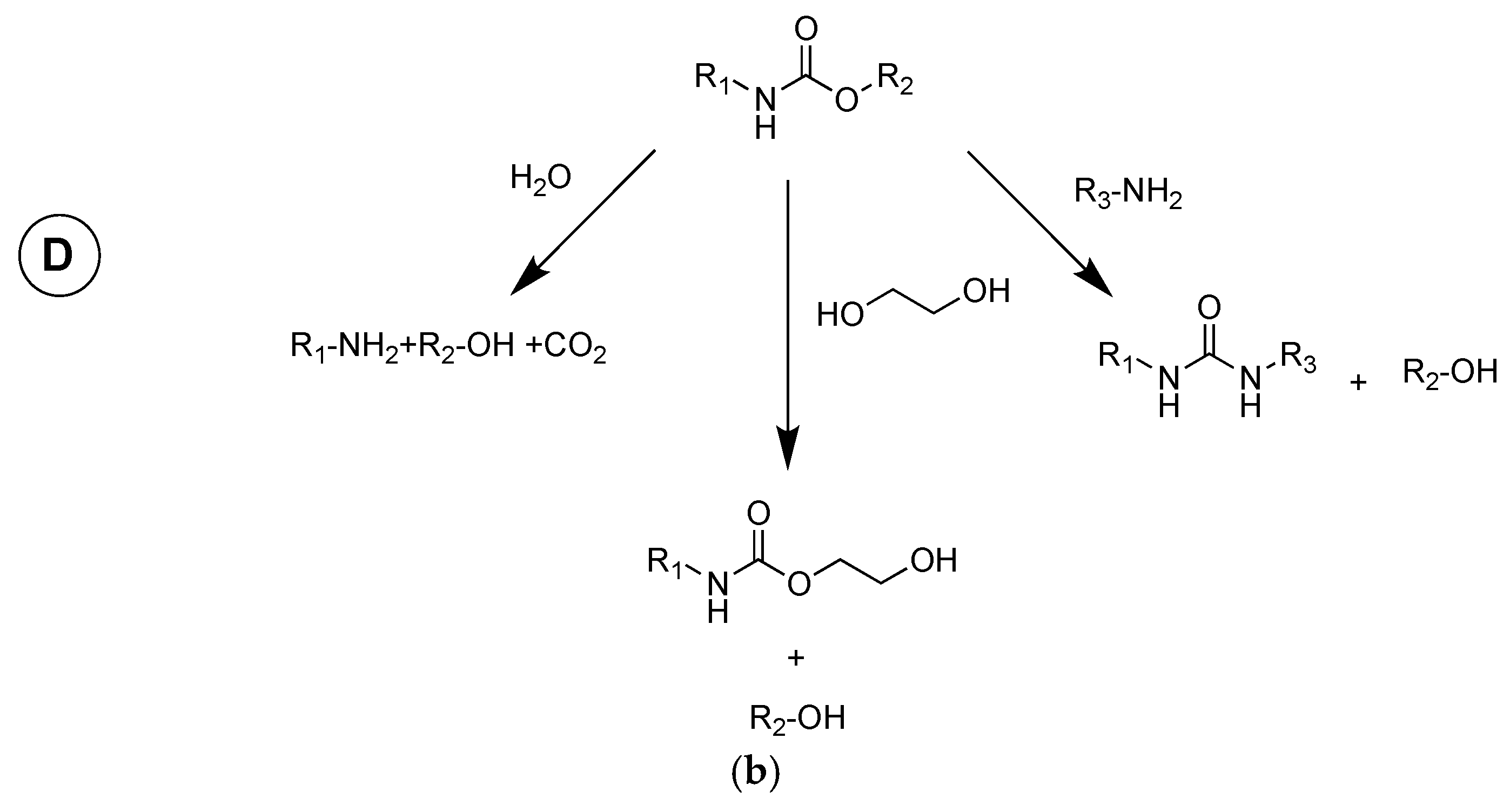

2. Recycling of Current Commercially Available Polymers

2.1. Pre-Treatment

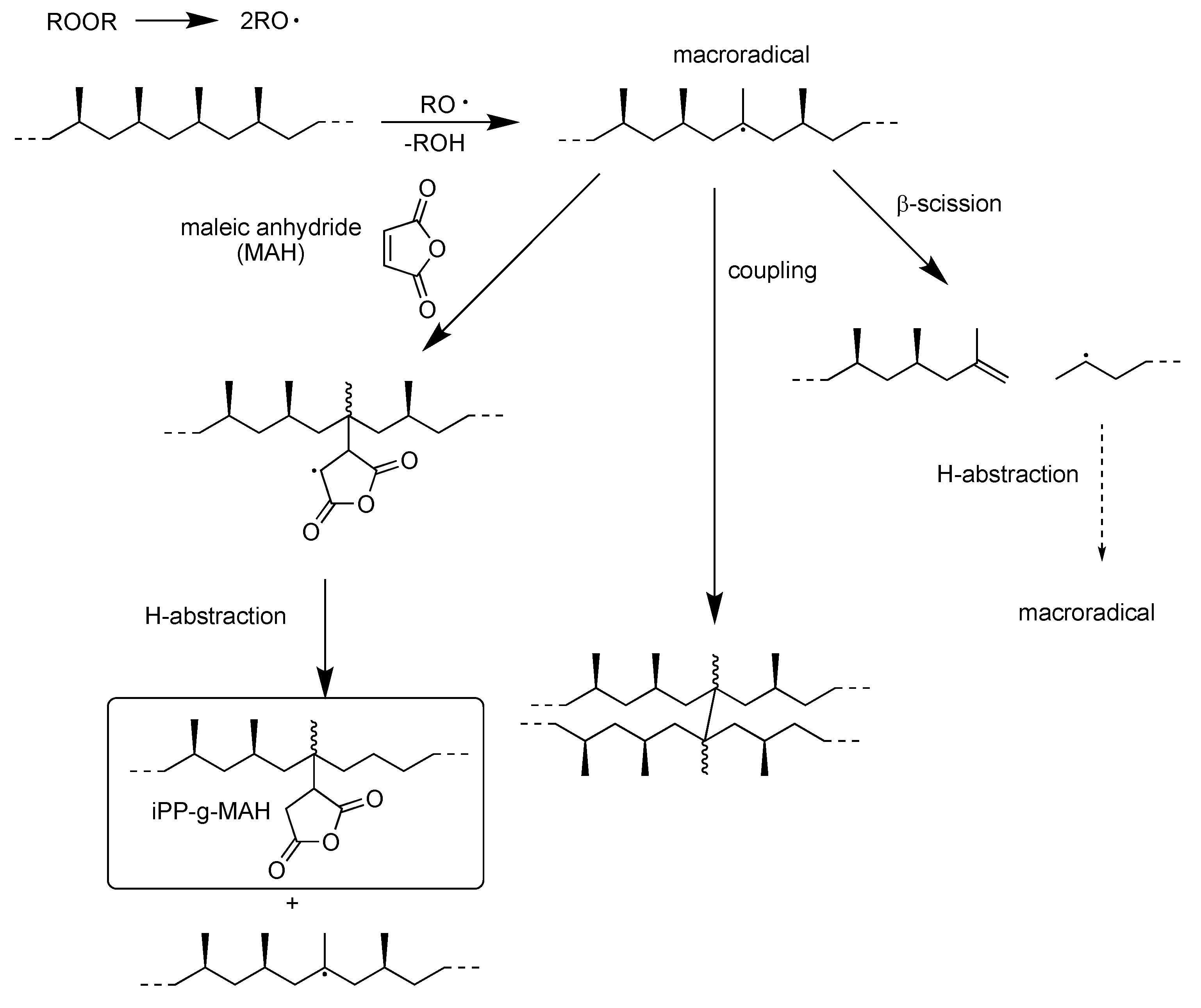

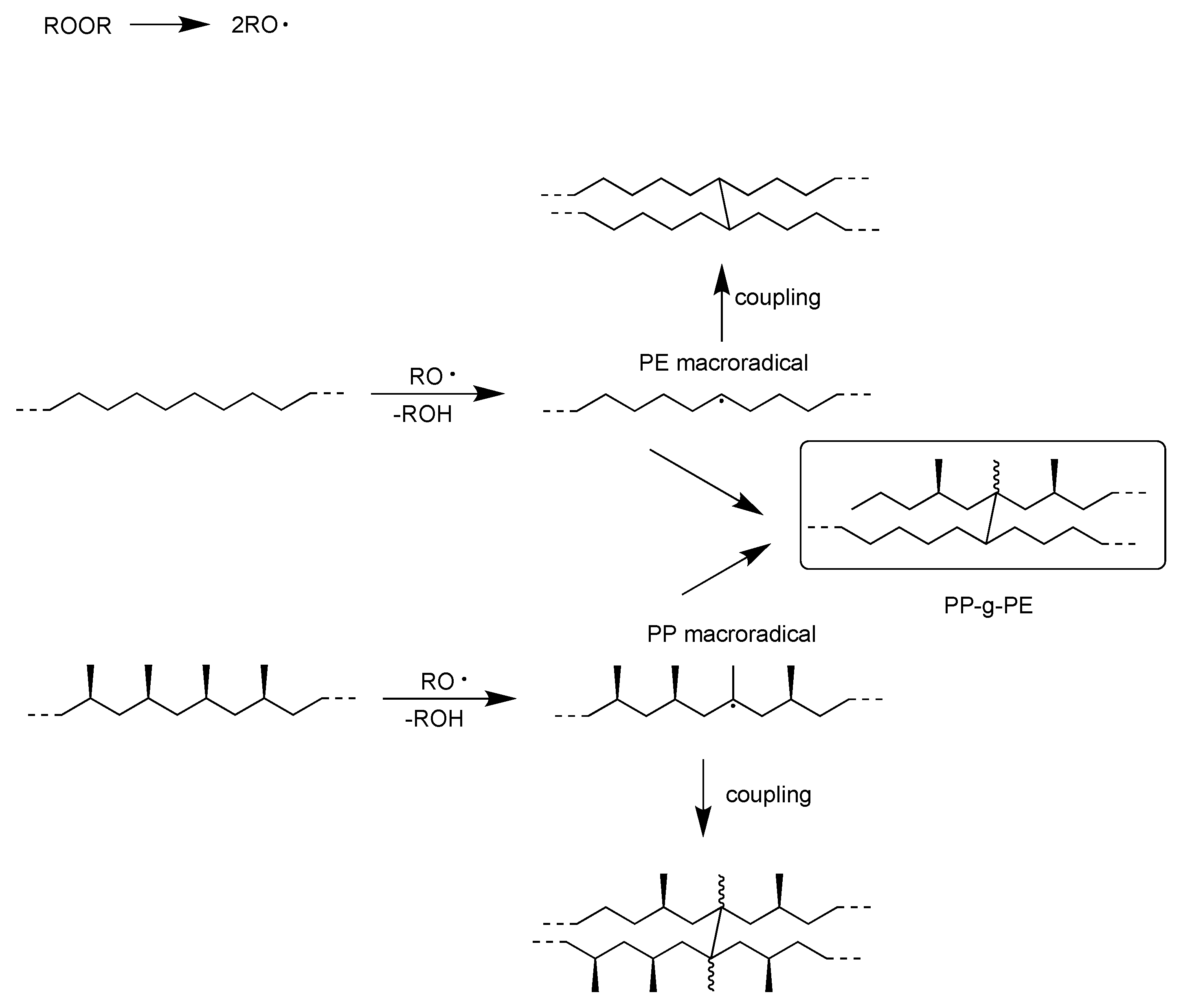

2.2. Material Recycling

2.3. Chemical Recycling

3. Future Outlook

3.1. Design for Recycling

3.2. General Considerations

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| ABS | Poly(acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene) |

| CAN | Covalent Adaptable Network |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamic |

| EPDM | Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GPC | Gel Permeation Chromatography |

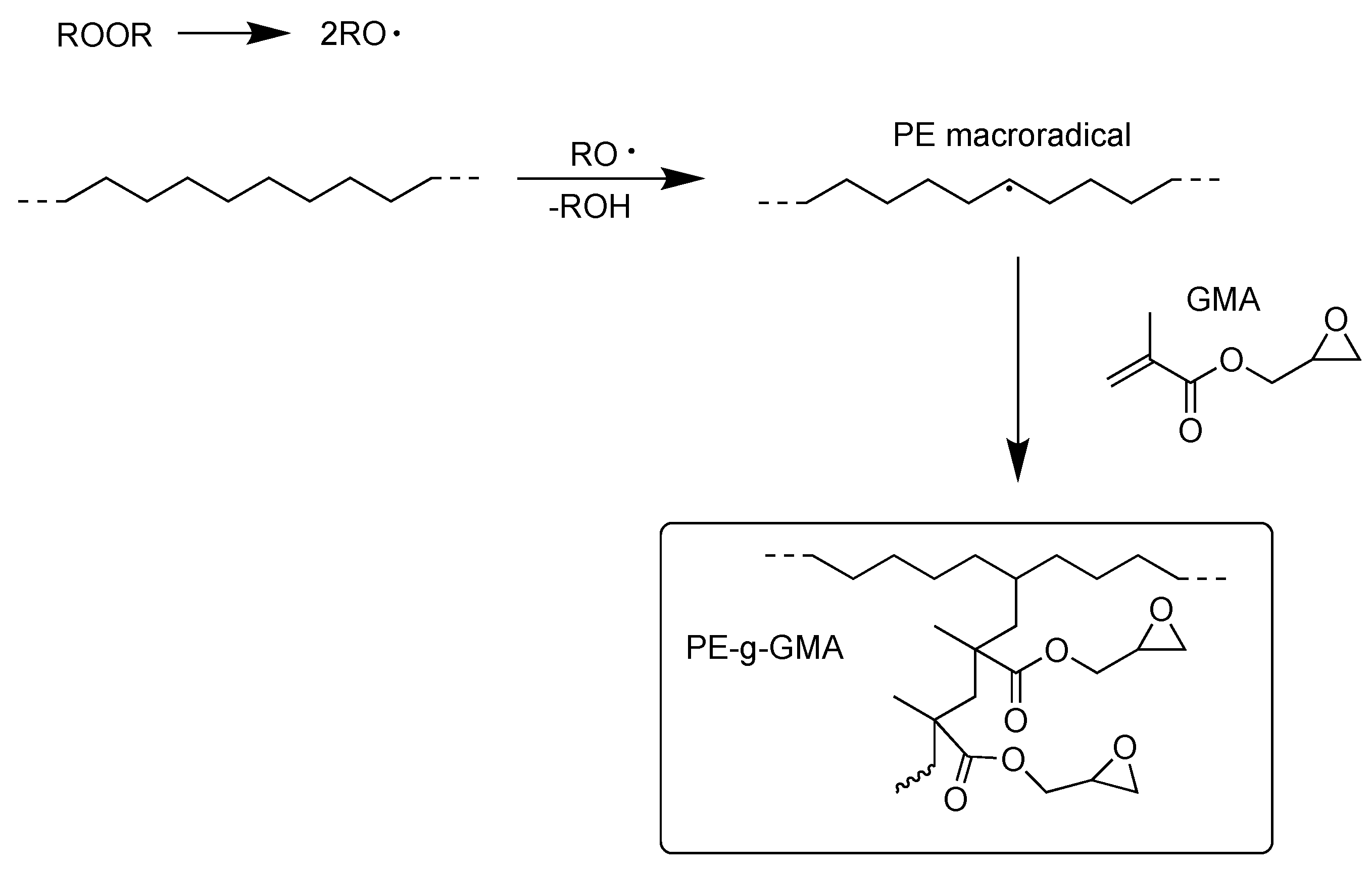

| GMA | Glycidyl methacrylate |

| HDPE | High Density Polyethylene |

| HIPS | High Impact Poly(styrene) |

| i | Isotactic |

| LDPE | Low Density Polyethylene |

| LMW | Low Molecular Weight |

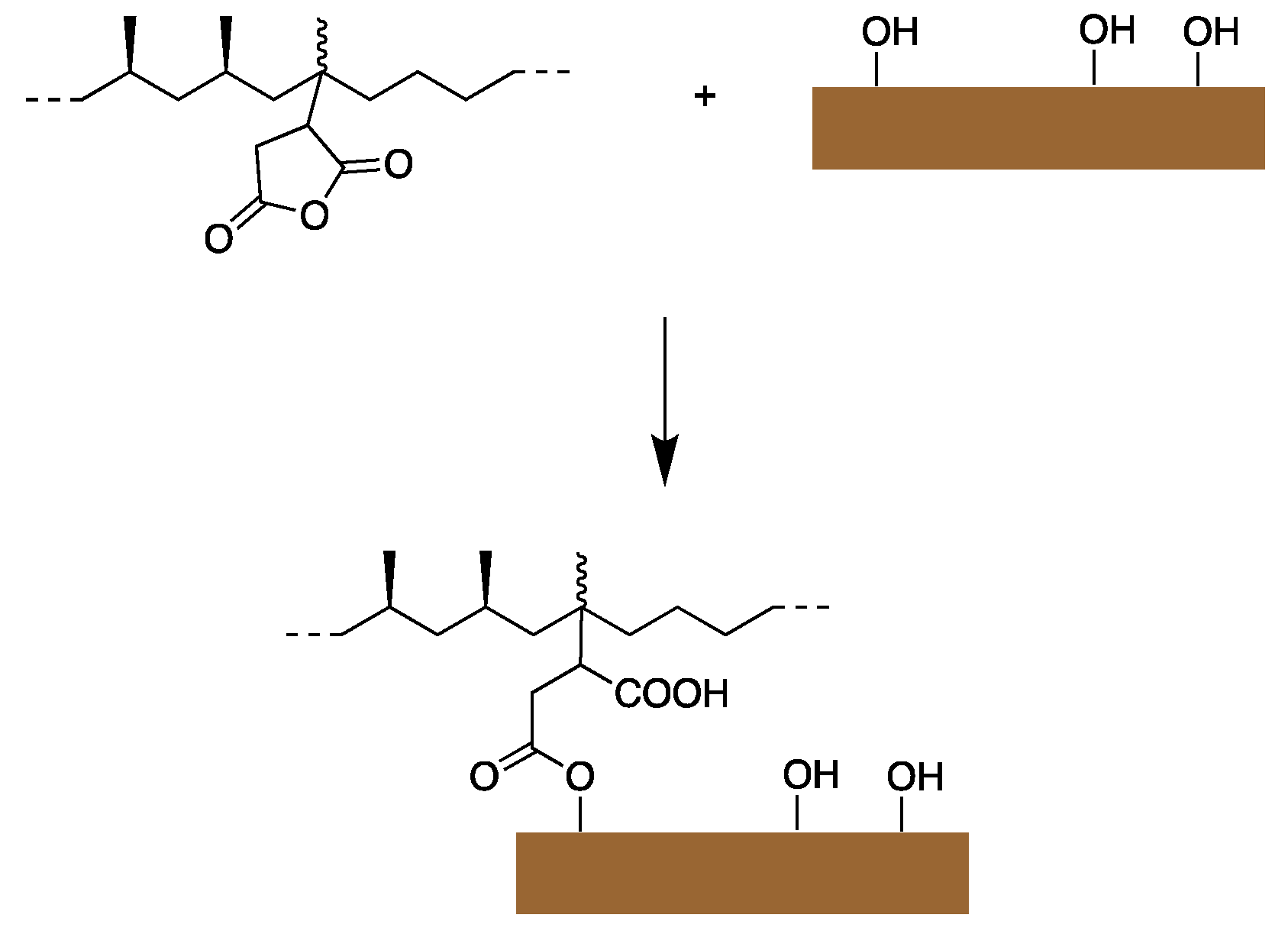

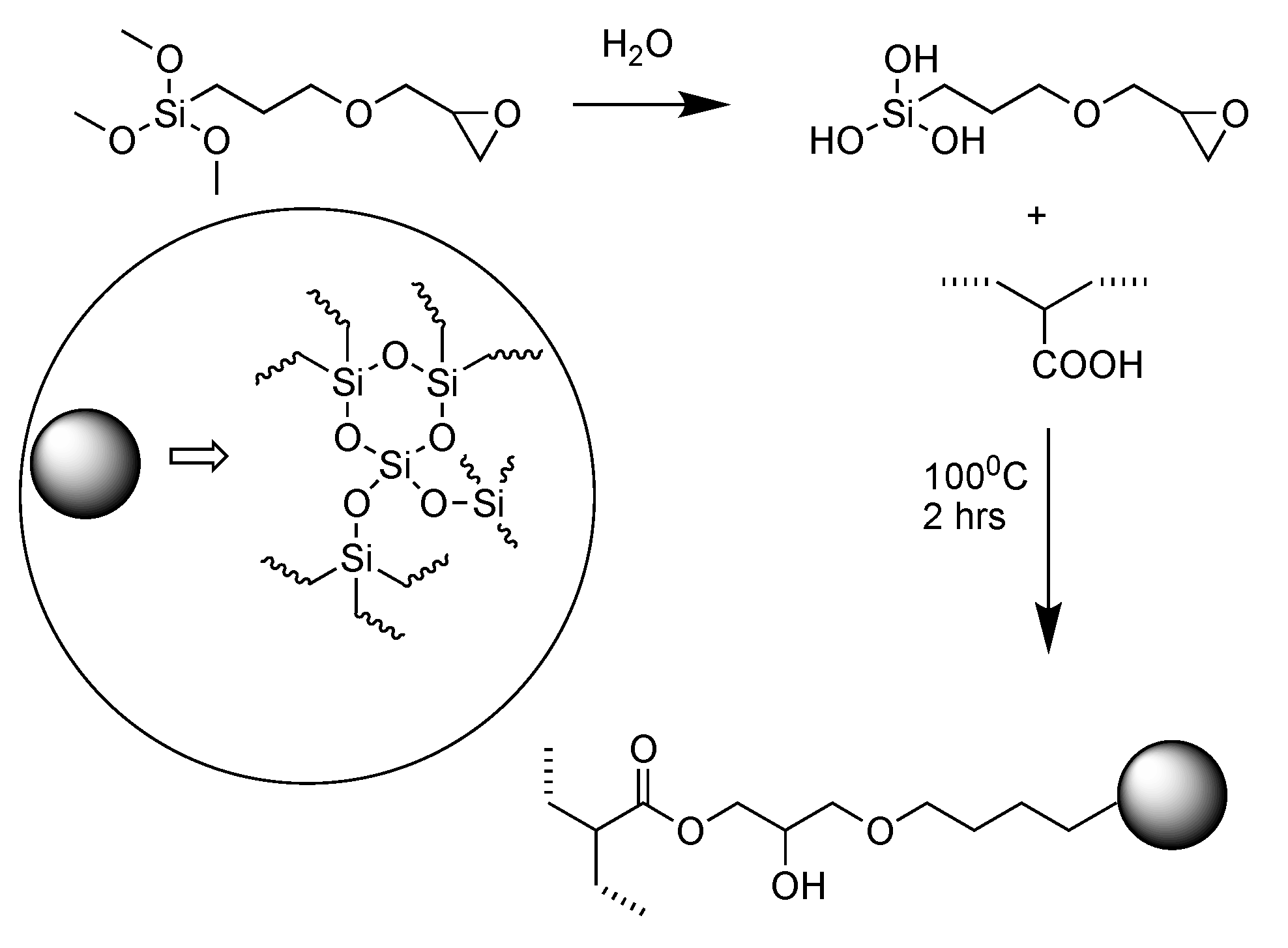

| MAH | Maleic anhydride |

| PAA | Poly(acrylic acid) |

| PC | Poly(carbonate) |

| PE | Poly(ethylene) |

| PET | Poly(ethylene terephthalate) |

| PHBV | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| PLA | Poly(lactic acid) |

| PMMA | Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| PP | Poly(propylene) |

| PS | Poly(styrene) |

| PU | Poly(urethane) |

| PVC | Poly(vinyl chloride) |

| SAN | Styrene-acrylonitrile resin |

| SAP | Super Adsorbant Polymer |

| r | Recycled |

References

- Gubanova, E., et al., RECYCLING OF POLYMER WASTE IN THE CONTEXT OF DEVELOPING CIRCULAR ECONOMY. Architecture Civil Engineering Environment, 2019. 12(4): p. 99-108. [CrossRef]

- Flizikowski, J., W. Kruszelnicka, and M. Macko, The Development of Efficient Contaminated Polymer Materials Shredding in Recycling Processes. Polymers, 2021. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J., POLYMER WASTE MANAGEMENT - BIODEGRADATION, INCINERATION, AND RECYCLING. Journal of Macromolecular Science-Pure and Applied Chemistry, 1995. A32(4): p. 593-597. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.L., et al., Recycling and Upgrading Utilization of Polymer Plastics†. Chinese Journal of Chemistry, 2023. 41(4): p. 469-480. [CrossRef]

- Somers, M.J., J.F. Alfaro, and G.M. Lewis, Feasibility of superabsorbent polymer recycling and reuse in disposable absorbent hygiene products. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021. 313. [CrossRef]

- Russo, S., et al., Exergy-Based Assessment of Polymers Production and Recycling: An Application to the Automotive Sector. Energies, 2021. 14(2). [CrossRef]

- Mekhzoum, M.E., et al., Recent Advances in Polymer Recycling: A Short Review. Current Organic Synthesis, 2017. 14(2): p. 171-185. [CrossRef]

- Spinacé, M.A.D. and M.A. De Paoli, The technology of polymer recycling. Quimica Nova, 2005. 28(1): p. 65-72. [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.S., POLYMER RECYCLING - OPPORTUNITIES AND LIMITATIONS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1992. 89(3): p. 835-838. [CrossRef]

- Bonardi, A., et al., Effects of degree of recycling on the rheology and processability of thermoplastic polymers. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 2003. 23(2): p. 79-94. [CrossRef]

- Fraïsse, F., et al., Recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate)/polycarbonate blends. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2005. 90(2): p. 250-255. [CrossRef]

- Albitres, G.A.V., L.C. Mendes, and S.P. Cestari, Polymer blends of polyamide-6/Spandex fabric scraps and recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate). Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2017. 129(3): p. 1505-1515. [CrossRef]

- SUTANTO, P., F. PICCHIONI, and L. JANSSEN, The use of experimental design to study the responses of continuous devulcanization processes. JOURNAL OF APPLIED POLYMER SCIENCE, 2006. 102(5): p. 5028-5038. [CrossRef]

- SUTANTO, P., F. PICCHIONI, and L. JANSSEN, Modelling a continuous devulcanization in an extruder. CHEMICAL ENGINEERING SCIENCE, 2006. 61(21): p. 7077-7086. [CrossRef]

- SUTANTO, P., et al., EPDM rubber reclaim from devulcanized EPDM. JOURNAL OF APPLIED POLYMER SCIENCE, 2006. 102(6): p. 5948-5957. [CrossRef]

- JANSSEN, L.P.B.M., P. SUTANTO, and F. PICCHIONI, Modelling a continuous devulcanization in an extruder. Chemical Engineering Science, 2006. vol.61, no.21: p. 7077-86. [CrossRef]

- JANSSEN, L.P.B.M., et al., Modeling on the kinetics of an EPDM devulcanization in an internal batch mixer using an amine as the devulcanizing agent. Chemical Engineering Science, 2006. vol.61, no.19: p. 6442-53. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E., et al., Effects of Recycled Polymer on Melt Viscosity and Crystallization Temperature of Polyester Elastomer Blends. Materials, 2023. 16(17). [CrossRef]

- Mormann, W. and P. Frank, (Supercritical) ammonia for recycling of thermoset polymers. Macromolecular Symposia, 2006. 242: p. 165-173. [CrossRef]

- Vogt, B.D., K.K. Stokes, and S.K. Kumar, Why is Recycling of Postconsumer Plastics so Challenging? Acs Applied Polymer Materials, 2021. 3(9): p. 4325-4346. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, W.N., et al., Effect of recycling on the thermal properties of polymers. Polymer Testing, 2007. 26(2): p. 216-221. [CrossRef]

- Hamad, K., M. Kaseem, and F. Deri, Recycling of waste from polymer materials: An overview of the recent works. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2013. 98(12): p. 2801-2812. [CrossRef]

- Jiun, Y.L., et al., Effects of Recycling Cycle on Used Thermoplastic Polymer and Thermoplastic Elastomer Polymer. Polymers & Polymer Composites, 2016. 24(9): p. 735-739. [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.P., Mechanical properties of recycled polymers. Macromolecular Symposia, 1999. 147: p. 167-172. [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.P. and N.T. Dintcheva, Time carbonyl groups equivalence in photo-oxidative aging of virgin/recycled polymer blends. Plastics Rubber and Composites, 2004. 33(4): p. 184-186. [CrossRef]

- Momanyi, J., M. Herzog, and P. Muchiri, Analysis of Thermomechanical Properties of Selected Class of Recycled Thermoplastic Materials Based on Their Applications. Recycling, 2019. 4(3). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.F., T.G. Hsu, and J.P. Wang, Mechanochemical Degradation and Recycling of Synthetic Polymers. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.A., et al., Effects of recycling on polystyrene shape memory polymers for in-situ resource utilization. Smart Materials and Structures, 2023. 32(9). [CrossRef]

- Fakirov, S., A new approach to plastic recycling via the concept of microfibrillar composites. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 2021. 4(3): p. 187-198. [CrossRef]

- Garforth, A.A., et al., Feedstock recycling of polymer wastes. Current Opinion in Solid State & Materials Science, 2004. 8(6): p. 419-425. [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, S., Recycled polyolefins. Material properties and means for quality determination, in Long-Term Properties of Polyolefins, A.C. Albertsson, Editor. 2004. p. 201-229. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.Y., et al., Recent trends in recycling and reusing techniques of different plastic polymers and their composite materials. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2022. 31. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, J., A Review of Recycling Methods for Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Sustainability, 2022. 14(24). [CrossRef]

- Sasse, F. and G. Emig, Chemical recycling of polymer materials. Chemical Engineering & Technology, 1998. 21(10): p. 777-789. [CrossRef]

- Ignatyev, I.A., W. Thielemans, and B. Vander Beke, Recycling of Polymers: A Review. Chemsuschem, 2014. 7(6): p. 1579-1593. [CrossRef]

- Ragaert, K., L. Delva, and K. Van Geem, Mechanical and chemical recycling of solid plastic waste. Waste Management, 2017. 69: p. 24-58. [CrossRef]

- Beigbeder, J., et al., Study of the physico-chemical properties of recycled polymers from waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) sorted by high resolution near infrared devices. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2013. 78: p. 105-114. [CrossRef]

- Florestan, J., et al., RECYCLING OF PLASTICS - AUTOMATIC IDENTIFICATION OF POLYMERS BY SPECTROSCOPIC METHODS. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 1994. 10(1-2): p. 67-74. [CrossRef]

- Bifulco, A., et al., Recycling of flame retardant polymers: Current technologies and future perspectives. Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 2024. 199: p. 156-183. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.J. and H. Wiebeck, Current options for characterizing, sorting, and recycling polymeric waste. Progress in Rubber Plastics and Recycling Technology, 2020. 36(4): p. 284-303. [CrossRef]

- Boekhoff, S., H. Zetzener, and A. Kwade, Comminution of Metal-Polymer Composites for Recycling. Chemie Ingenieur Technik, 2024. 96(7): p. 941-949. [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, P., M. Scheffer, and H. Bos, Textiles for Circular Fashion: The Logic behind Recycling Options. Sustainability, 2021. 13(17). [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S., et al., Opportunities and Limitations in Recycling Fossil Polymers from Textiles. Macromol, 2023. 3(2): p. 120-148. [CrossRef]

- Boborodea, A., S. O’Donohue, and A. Brookes, A new GPC/TREF/LinELSD instrument to determine the molecular weight distribution and chemical composition: application to recycled polymers. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization, 2021. 26(8): p. 721-734. [CrossRef]

- Brasileiro, L.L., et al., Study of the feasability of producing modified asphalt bitumens using flakes made from recycled polymers. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 208: p. 269-282. [CrossRef]

- Buczynski, P. and M. Iwanski, The Influence of a Polymer Powder on the Properties of a Cold-Recycled Mixture with Foamed Bitumen. Materials, 2019. 12(24). [CrossRef]

- Casey, D., et al., Development of a recycled polymer modified binder for use in stone mastic asphalt. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2008. 52(10): p. 1167-1174. [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, J.M.L. and M.A.G. Jurumenha, Experimental Investigation on the Effects of Recycled Aggregate on Fracture Behavior of Polymer Concrete. Materials Research-Ibero-American Journal of Materials, 2011. 14(3): p. 326-330. [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, J.M.L., et al., Mechanical Characterization Using Optical Fiber Sensors of Polyester Polymer Concrete Made with Recycled Aggregates. Materials Research-Ibero-American Journal of Materials, 2009. 12(3): p. 269-271. [CrossRef]

- Eui-Hwan, H., Y.S. Ko, and J.K. Jeon, Effect of polymer cement modifiers on mechanical and physical properties of polymer-modified mortar using recycled waste concrete fine aggregate. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2007. 13(3): p. 387-394. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, F.P., et al., Effects of Recycled Steel and Polymer Fibres on Explosive Fire Spalling of Concrete. Fire Technology, 2019. 55(5): p. 1495-1516. [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Audén, C., et al., Evaluation of thermal and mechanical properties of recycled polyethylene modified bitumen. Polymer Testing, 2008. 27(8): p. 1005-1012. [CrossRef]

- Asdollah-Tabar, M., M. Heidari-Rarani, and M.R.M. Aliha, The effect of recycled PET bottles on the fracture toughness of polymer concrete. Composites Communications, 2021. 25. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.T., et al., Evaluation of mechanical/dynamic properties of polyetherimide recycled polymer concrete for reducing rail slab noise. Functional Composites and Structures, 2019. 1(2). [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.W., S.K. Park, and J.C. Park, Mechanical properties of polymer concrete made with recycled PET and recycled concrete aggregates. Construction and Building Materials, 2008. 22(12): p. 2281-2291. [CrossRef]

- Jo, B.W., S.K. Park, and C.H. Kim, Mechanical properties of polyester polymer concrete using recycled polyethylene terephthalate. Aci Structural Journal, 2006. 103(2): p. 219-225.

- Martínez-Barrera, G., et al., Modified recycled tire fibers by gamma radiation and their use on the improvement of polymer concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 2019. 204: p. 327-334. [CrossRef]

- Martuscelli, C.C., et al., Polymer-cementitious composites containing recycled rubber particles. Construction and Building Materials, 2018. 170: p. 446-454. [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S.B., et al., Properties of Modified Bitumen Obtained from Vacuum Bottom by Adding Recycled Waste Polymers and Natural Bitumen. Iranian Polymer Journal 2010, 19(3), 197–205.

- Navarro, F.J., et al., Bitumen modification with reactive and non-reactive (virgin and recycled) polymers: A comparative analysis. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2009. 15(4): p. 458-464. [CrossRef]

- Nizamuddin, S., Y.J. Boom, and F. Giustozzi, Sustainable Polymers from Recycled Waste Plastics and Their Virgin Counterparts as Bitumen Modifiers: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers, 2021. 13(19). [CrossRef]

- Rebeiz, K.S., Precast use of polymer concrete using unsaturated polyester resin based on recycled PET waste. Construction and Building Materials, 1996. 10(3): p. 215-220. [CrossRef]

- Rebeiz, K.S. and D.W. Fowler, Flexural strength of reinforced polymer concrete made with recycled plastic waste. Aci Structural Journal, 1996. 93(5): p. 524-530. [CrossRef]

- Rebeiz, K.S., S. Yang, and D.W. Fowler, POLYMER MORTAR COMPOSITES MADE WITH RECYCLED PLASTICS. Aci Materials Journal, 1994. 91(3): p. 313-319. [CrossRef]

- Rebeiz, K.S., D.W. Fowler, and D.R. Paul, MECHANICAL-PROPERTIES OF POLYMER CONCRETE SYSTEMS MADE WITH RECYCLED PLASTIC. Aci Materials Journal, 1994. 91(1): p. 40-45. [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.M.L., et al., Effect of recycled PET in the fracture mechanics of polymer mortar. Construction and Building Materials, 2011. 25(6): p. 2799-2804. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, M., M. Pal, and D. Sarkar, Performance of polymer-reinforced bituminous mixes using recycled coarse aggregate. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport, 2021. 174(2): p. 142-156. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., S.A. Hadigheh, and Y. Wei, Recycling of glass fibre reinforced polymer (GFRP) composite wastes in concrete: A critical review and cost benefit analysis. Structures, 2023. 53: p. 1540-1556. [CrossRef]

- Viscione, N., et al., Performance-based characterization of recycled polymer modified asphalt mixture. Construction and Building Materials, 2021. 310. [CrossRef]

- Wieser, M., et al., On the Effect of Recycled Polyolefins on the Thermorheological Performance of Polymer-Modified Bitumen Used for Roofing-Applications. Sustainability, 2021. 13(6). [CrossRef]

- Xiong, C., et al., Study of Mechanical Properties of an Eco-Friendly Concrete Containing Recycled Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer and Recycled Aggregate. Materials, 2020. 13(20). [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.Q., et al., Impact of virgin and recycled polymer fibers on the rheological properties of cemented paste backfill. Scientific Reports, 2024. 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Samchenko, S.V. and O.A. Larsen, Modifying the Sand Concrete with Recycled Tyre Polymer Fiber to Increase the Crack Resistance of Building Structures. Buildings, 2023. 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Assaad, J.J. and C.A. Issa, Effect of Recycled Acrylic-Based Polymers on Bond Stress-Slip Behavior in Reinforced Concrete Structures. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering, 2017. 29(1). [CrossRef]

- Baricevic, A., et al., Influence of recycled tire polymer fibers on concrete properties. Cement & Concrete Composites, 2018. 91: p. 29-41. [CrossRef]

- Gawdzinska, K., et al., The Choice of Recycling Methods for Single-Polymer Polyester Composites. Materiale Plastice, 2018. 55(4): p. 658-665. [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C.J., CONSTRUCTION MATERIALS FROM RECYCLED POLYMERS. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Structures and Buildings, 1993. 99(4): p. 455-464. [CrossRef]

- Devasahayam, S., et al., PlasticsVillain or Hero? Polymers and Recycled Polymers in Mineral and Metallurgical ProcessingA Review. Materials, 2019. 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Audén, C., et al., Formulation of new synthetic properties of recycled binders:: Thermo-mechanical polymer/oil blends. Polymer Testing, 2007. 26(3): p. 323-332. [CrossRef]

- Duflou, J.R., et al., Product clustering as a strategy for enhanced plastics recycling from WEEE. Cirp Annals-Manufacturing Technology, 2020. 69(1): p. 29-32. [CrossRef]

- Dias, P., et al., Recycling WEEE: Polymer characterization and pyrolysis study for waste of crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules. Waste Management, 2017. 60: p. 716-722. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, D., et al., Recycling of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS): a review. Polymer Bulletin, 2024. 81(13): p. 28-38. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.P., R.M.C. Santana, and H.M. Veit, Evaluation of Recycled Polymers From CRT Monitor Frames of Different Years of Manufacture. Progress in Rubber Plastics and Recycling Technology, 2014. 30(1): p. 55-66. [CrossRef]

- Achilias, D.S., et al., Chemical Recycling of Polymers from Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2009. 114(1): p. 212-221. [CrossRef]

- Achilias, D.S., A. Giannoulis, and G.Z. Papageorgiou, Recycling of polymers from plastic packaging materials using the dissolution-reprecipitation technique. Polymer Bulletin, 2009. 63(3): p. 449-465. [CrossRef]

- Cecon, V.S., G.W. Curtzwiler, and K.L. Vorst, A Study on Recycled Polymers Recovered from Multilayer Plastic Packaging Films by Solvent-Targeted Recovery and Precipitation (STRAP). Macromolecular Materials and Engineering, 2022. 307(11). [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.J., G.F. Najmuldeen, and K. Bin Yusoh, Dissolution/reprecipitation technique for waste polyolefin recycling using new pure and blend organic solvents. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 2013. 33(5): p. 471-481. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.M., et al., Progress in Solvent-Based Recycling of Polymers from Multilayer Packaging. Polymers, 2024. 16(12). [CrossRef]

- Denolf, R., et al., Constructing and validating ternary phase diagrams as basis for polymer dissolution recycling. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 2023. 387. [CrossRef]

- Pappa, G., et al., The selective dissolution/precipitation technique for polymer recycling: a pilot unit application. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2001. 34(1): p. 33-44. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Y., et al., Modification of fresh and hardened properties of 3D-printed recycled mortar by superabsorbent polymers. Journal of Building Engineering, 2024. 95. [CrossRef]

- Cecon, V.S., et al., The effect of post-consumer recycled polyethylene (PCRPE) on the properties of polyethylene blends of different densities. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2021. 190. [CrossRef]

- Cecon, V.S., et al., Dataset of the properties of polyethylene (PE) blends of different densities mixed with post-consumer recycled polyethylene (PCRPE). Data in Brief, 2021. 38. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C., et al., Influence of Recycled ABS Added to Virgin Polymers on the Physical, Mechanical Properties and Molding Characteristics. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering, 2011. 50(3): p. 306-311. [CrossRef]

- Titone, V., et al., Toward the Decarbonization of Plastic: Monopolymer Blend of Virgin and Recycled Bio-Based, Biodegradable Polymer. Polymers, 2022. 14(24). [CrossRef]

- Dorigato, A., Recycling of polymer blends. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 2021. 4(2): p. 53-69.

- Rydzkowski, T., PROPERTIES OF RECYCLED POLYMER MIXTURES OBTAINED IN THE SCREW-DISC EXTRUSION PROCESS. Polimery, 2011. 56(2): p. 135-139. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., et al., Blends of syndiotactic polystyrene with SEBS triblock copolymers. POLYMER, 2002. 43(11): p. 3323-3329. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., et al., Blends of SBS triblock copolymer with poly(2,6-dimethyl-1,4-phenylene oxide)/polystyrene mixture. JOURNAL OF APPLIED POLYMER SCIENCE, 2003. 88(11): p. 2698-2705. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., et al., Blending of styrene-block-butadiene-block styrene copolymer with sulfonated vinyl aromatic polymers. POLYMER INTERNATIONAL, 2001. 50(6): p. 714-721. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., J. GOOSSENS, and M. VAN DUIN, Solid-state modification of polypropylene (PP): Grafting of styrene on atactic PP. MACROMOLECULAR SYMPOSIA, 2001. 176: p. 245-263. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., J. GOOSSENS, and M. VAN DUIN, Solid-state modification of isotactic polypropylene (iPP) via grafting of styrene. II. Morphology and melt processing. JOURNAL OF APPLIED POLYMER SCIENCE, 2005. 97(2): p. 575-583. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., et al., Solid-state modification of isotactic polypropylene (iPP) via grafting of styrene. I. Polymerization experiments. JOURNAL OF APPLIED POLYMER SCIENCE, 2003. 89(12): p. 3279-3291. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., et al., Blends of syndiotactic polystyrene with SBS triblock copolymers. MACROMOLECULAR CHEMISTRY AND PHYSICS, 2001. 202(11): p. 2142-2147. [CrossRef]

- PICCHIONI, F., et al., Blends of styrene-butadiene-styrene triblock copolymer with random styrene-maleic anhydride copolymers. MACROMOLECULAR CHEMISTRY AND PHYSICS, 2002. 203(10-11): p. 1396-1402. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Silva, P.C., et al., Active Mono-Material Films from Natural and Post-consumer Recycled Polymers with Essential Oils for Food Packaging Applications. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 2023. 31(12): p. 5198-5209. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D., et al., Mechanical properties of recycled PVC blends with styrenic polymers. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2006. 101(4): p. 2464-2471. [CrossRef]

- Lepadatu, A.M., S. Asaftei, and N. Vennemann, Recycling of EPDM Rubber Waste Powder by Activation with liquid Polymers. Kgk-Kautschuk Gummi Kunststoffe, 2014. 67(1-2): p. 41-47.

- Möllnitz, S., et al., Processability of Different Polymer Fractions Recovered from Mixed Wastes and Determination of Material Properties for Recycling. Polymers, 2021. 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.P., et al., Recycling and Mechanical Characterization of Polymer Blends Present in Printers. Materials Research-Ibero-American Journal of Materials, 2017. 20: p. 202-208. [CrossRef]

- Akkapeddi, M.K., et al., PERFORMANCE BLENDS BASED ON RECYCLED POLYMERS. Polymer Engineering and Science, 1995. 35(1): p. 72-78. [CrossRef]

- Titone, V., E.F. Gulino, and F.P. La Mantia, Recycling of Heterogeneous Mixed Waste Polymers through Reactive Mixing. Polymers, 2023. 15(6). [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.S., Polymer recycling: Thermodynamics and economics, in Plastics, Rubber, and Paper Recycling: A Pragmatic Approach, C.P. Rader, et al., Editors. 1995. p. 27-46. [CrossRef]

- Stein, R.S., Polymer recycling: Thermodynamics and economics. Macromolecular Symposia, 1998. 135: p. 295-314. [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, S.M., et al., Mechanical Recycling of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer in a Circular Economy. Polymers, 2024. 16(10). [CrossRef]

- Amberg, M., et al., Surface modification of recycled polymers in comparison to virgin polymers using Ar/O2 plasma etching. Plasma Processes and Polymers, 2022. 19(12). [CrossRef]

- Ateeq, M., et al., A review of 3D printing of the recycled carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites: Processing, potential, and perspectives. Journal of Materials Research and Technology-Jmr&T, 2023. 26: p. 2291-2309. [CrossRef]

- Czvikovszky, T. and H. Hargitai, Electron beam surface modifications in reinforcing and recycling of polymers. Nuclear Instruments & Methods in Physics Research Section B-Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, 1997. 131(1-4): p. 300-304. [CrossRef]

- CIARDELLI, F., et al., Controlled functionalization of olefin/styrene copolymers through free radical processes. POLYMERS FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES, 2000. 11(8-12): p. 371-376. [CrossRef]

- PASSAGLIA, E., et al., Grafting of diethyl maleate and maleic anhydride onto styrene-b-(ethylene-co-1-butene)-b-styrene triblock copolymer (SEBS). POLYMER, 2000. 41(12): p. 4389-4400. [CrossRef]

- PASSAGLIA, E., et al., Formation and compatibilizing effect of the grafted copolymer in the reactive blending of 2-diethylsuccinate containing polyolefins with poly-epsilon-caprolactam (Nylon-6). POLYMERS FOR ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES, 1998. 9(5): p. 273-281. [CrossRef]

- PASSAGLIA, E., et al., Features of graft copolymer formation through reaction of functionalized polyolefins with poly-epsilon-caprolatam. TURKISH JOURNAL OF CHEMISTRY, 1997. 21(4): p. 262-269.

- Suresh, S.S., S. Mohanty, and S.K. Nayak, Epoxidized soybean oil toughened recycled blends: a new method for the toughening of recycled polymers employing renewable resources. Polymer Bulletin, 2020. 77(12): p. 6543-6562. [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R., et al., Degradation and Recycling of Films Based on Biodegradable Polymers: A Short Review. Polymers, 2019. 11(4). [CrossRef]

- Bavasso, I., et al., Recycling of a commercial biodegradable polymer blend: Influence of reprocessing cycles on rheological and thermo-mechanical properties. Polymer Testing, 2024. 134. [CrossRef]

- Paiva, R., et al., Biobased Polymer Recycling: A Comprehensive Dive into the Recycling Process of PLA and Its Decontamination Efficacy. Acs Applied Polymer Materials, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, F.R., et al., Valorization of poly(lactic acid) wastes via mechanical recycling: Improvement of the properties of the recycled polymer. Waste Management & Research, 2019. 37(2): p. 135-141. [CrossRef]

- Capuano, R., et al., Valorization and Mechanical Recycling of Heterogeneous Post-Consumer Polymer Waste through a Mechano-Chemical Process. Polymers, 2021. 13(16). [CrossRef]

- Korol, J., et al., Wastes from Agricultural Silage Film Recycling Line as a Potential Polymer Materials. Polymers, 2021. 13(9). [CrossRef]

- Martikka, O. and T. Kärki, Promoting Recycling of Mixed Waste Polymers in Wood-Polymer Composites Using Compatibilizers. Recycling, 2019. 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Mengeloglu, F. and K. Karakus, Some Properties of Eucalyptus Wood Flour Filled Recycled High Density Polyethylene Polymer-Composites. Turkish Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2008. 32(6): p. 537-546.

- Nukala, S.G., et al., Development of Wood Polymer Composites from Recycled Wood and Plastic Waste: Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Journal of Composites Science, 2022. 6(7). [CrossRef]

- Moini, N. and K. Kabiri, Organosilane compounds for tunable recycling of waste superabsorbent polymer fine particles. Polymer Bulletin, 2022. 79(11): p. 10229-10249. [CrossRef]

- Ropota, I., et al., RECYCLING SOLID WASTES AS POLYMER COMPOSITES. Studia Universitatis Babes-Bolyai Chemia, 2013. 58(4): p. 213-225.

- Wisniewska, P., et al., Rubber wastes recycling for developing advanced polymer composites: A warm handshake with sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2023. 427. [CrossRef]

- Zenkiewicz, M. and M. Kurcok, Effects of compatibilizers and electron radiation on thermomechanical properties of composites consisting of five recycled polymers. Polymer Testing, 2008. 27(4): p. 420-427. [CrossRef]

- Zenkiewicz, M. and J. Dzwonkowski, Effects of electron radiation and compatibilizers on impact strength of composites of recycled polymers. Polymer Testing, 2007. 26(7): p. 903-907. [CrossRef]

- Niño, C.G., et al., Effect of Gamma Radiation on the Processability of New and Recycled PA-6 Polymers. Polymers, 2023. 15(3). [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.P., Re-stabilization of recycled polymers. Macromolecular Symposia, 2000. 152: p. 201-210. [CrossRef]

- 140. Bek, M., et al., Long-Term Creep Compliance of Wood Polymer Composites: Using Untreated Wood Fibers as a Filler in Recycled and Neat Polypropylene Matrix. Polymers, 2022. 14(13). [CrossRef]

- Begley, T.H. and H.C. Hollifield, Food packaging made form recycled polymers - Functional barrier considerations, in Plastics, Rubber, and Paper Recycling: A Pragmatic Approach, C.P. Rader, et al., Editors. 1995. p. 445-457. [CrossRef]

- Cecon, V.S., et al., The challenges in recycling post-consumer polyolefins for food contact applications: A review. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2021. 167. [CrossRef]

- Sadler, G.D., Recycling of polymers for food use: A current perspective, in Plastics, Rubber, and Paper Recycling: A Pragmatic Approach, C.P. Rader, et al., Editors. 1995. p. 380-388. [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.A., et al., Recycled Polymers for Food Contact. Polimeros-Ciencia E Tecnologia, 2011. 21(4): p. 340-345.

- Kolek, Z., Recycled polymers from food packaging in relation to environmental protection. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 2001. 10(1): p. 73-76.

- Vergnaud, J.M., Problems encountered for food safety with polymer packages: chemical exchange, recycling. Advances in Colloid and Interface Science, 1998. 78(3): p. 267-297. [CrossRef]

- Perou, A.L. and J.M. Vergnaud, Contaminant transfer during the processing of thick three-layer food packages with a recycled polymer between two virgin polymer layers. International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow, 1998. 8(7): p. 841-+. [CrossRef]

- Perou, A.L. and J.M. Vergnaud, Contaminant transfer during the co-extrusion of food packages made of recycled polymer and virgin polymer layers. Polymer, 1997. 38(18): p. A1-A6. [CrossRef]

- Perou, A.L. and J.M. Vergnaud, Contaminant transfer during the coextrusion of thin three-layer food packages with a recycled polymer between two virgin polymer layers. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 1997. 17(5): p. 349-361. [CrossRef]

- Feigenbaum, A., S. Laoubi, and J.M. Vergnaud, Kinetics of diffusion of a pollutant from a recycled polymer through a functional barrier: Recycling plastics for food packaging. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 1997. 66(3): p. 597-607. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G., et al., Conversion of recycled polymers fibers into melt-blown nonwovens. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering, 1999. 38(3): p. 499-511. [CrossRef]

- Evstatiev, M., et al., Recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate) as polymer-polymer composites. Polymer Engineering and Science, 2002. 42(4): p. 826-835. [CrossRef]

- Daren, S., Homomicronization - a route for polymer recycling. The Newplast process. Polimery, 1998. 43(6): p. 379-383.

- Arif, Z.U., et al., Recycling of the glass/carbon fibre reinforced polymer composites: A step towards the circular economy. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials, 2022. 61(7): p. 761-788. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.Y., et al., Efficient method of recycling carbon fiber from the waste of carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2020. 182. [CrossRef]

- May, D., C. Goergen, and K. Friedrich, Multifunctionality of polymer composites based on recycled carbon fibers: A review. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 2021. 4(2): p. 70-81. [CrossRef]

- Vega-Leal, C., et al., Mechanical recycling of carbon fibre reinforced polymers. Part 1: influence of cutting speed on recycled particles and composites properties. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 2024. 17(1): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Ateeq, M., A state of art review on recycling and remanufacturing of the carbon fiber from carbon fiber polymer composite. Composites Part C: Open Access, 2023. 12. [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K., et al., Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composite Polymers-Review-Part 1: Volume of Production, Recycling Technologies, Legislative Aspects. Polymers, 2021. 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Bledzki, A.K., et al., Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composite Polymers-Review-Part 2: Recovery and Application of Recycled Carbon Fibers. Polymers, 2020. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Butenegro, J.A., et al., Recent Progress in Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymers Recycling: A Review of Recycling Methods and Reuse of Carbon Fibers. Materials, 2021. 14(21). [CrossRef]

- Unterweger, C., et al., Impact of fiber length and fiber content on the mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of short carbon fiber reinforced polypropylene composites. Composites Science and Technology, 2020. 188. [CrossRef]

- Khanam, P.N. and M.A. AlMaadeed, Improvement of ternary recycled polymer blend reinforced with date palm fibre. Materials & Design, 2014. 60: p. 532-539. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, K.M., D. Ponnamma, and M.A. Al-Maadeed, Date palm fibre filled recycled ternary polymer blend composites with enhanced flame retardancy. Polymer Testing, 2017. 61: p. 341-348. [CrossRef]

- Tasdemir, M., et al., Properties of Recycled Polycarbonate/Waste Silk and Cotton Fiber Polymer Composites. International Journal of Polymeric Materials, 2008. 57(8): p. 797-805. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castellanos, W., et al., Nanomechanical properties and thermal stability of recycled cellulose reinforced starch-gelatin polymer composite. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2015. 132(14). [CrossRef]

- Dib, A., et al., Parametric characterization of recycled polymers with nanofillers. Polymer Composites, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y., Recent progress on preparation and properties of nanocomposites from recycled polymers: A review. Waste Management, 2013. 33(3): p. 598-604. [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y., et al., An analysis of interfacial adhesion in nanocomposites from recycled polymers. Computational Materials Science, 2014. 81: p. 612-616. [CrossRef]

- Zdiri, K., et al., Reinforcement of recycled PP polymers by nanoparticles incorporation. Green Chemistry Letters and Reviews, 2018. 11(3): p. 296-311. [CrossRef]

- Djoumaliisky, S. and P. Zipper, Modification of recycled polymer blends with activated natural zeolite. Macromolecular Symposia, 2004. 217: p. 391-400. [CrossRef]

- Hong, B. and H. Byun, Preparation of Polymer-modified Mortars with Recycled PET and Their Sound Absorption Characteristics. Polymer-Korea, 2010. 34(5): p. 410-414. [CrossRef]

- Singh, N., R. Singh, and I.P.S. Ahuja, Recycling of polymer waste with SiC/Al2O3 reinforcement for rapid tooling applications. Materials Today Communications, 2018. 15: p. 124-127. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., et al., Waste management by recycling of polymers with reinforcement of metal powder. Composites Part B-Engineering, 2016. 105: p. 23-29. [CrossRef]

- Keskisaari, A., T. Kärki, and T. Vuorinen, Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polymer Composites Made from Side-Stream Materials from Different Industries. Sustainability, 2019. 11(21). [CrossRef]

- Toncheva, A., et al., Recycled Tire Rubber in Additive Manufacturing: Selective Laser Sintering for Polymer-Ground Rubber Composites. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2021. 11(18). [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.J.Y., et al., Conductive Polymer Composites Made from Polypropylene and Recycled Graphite Scrap. Journal of Physical Science, 2021. 32(3): p. 31-44. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T., et al., Closed-loop recycling of microparticle-based polymers. Green Chemistry, 2023. 25(9): p. 3418-3424. [CrossRef]

- Hugo, A.M., et al., Development of recycled polymer composites for structural applications. Plastics Rubber and Composites, 2011. 40(6-7): p. 317-323. [CrossRef]

- Grillo, C.C. and C. Saron, Accelerated aging of polymer composite from Pennisetum purpureum fibers with recycled low-density polyethylene. Journal of Composite Materials, 2023. 57(20): p. 3231-3242. [CrossRef]

- Paraye, P. and R.M. Sarviya, Advances in polymer composites, manufacturing, recycling, and sustainable practices. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Materials, 2024. 63(11): p. 1474-1497. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, D.R., R.K. Vieira, and M.C. Chain, Strategy and management for the recycling of carbon fiber-reinforced polymers (CFRPs) in the aircraft industry: a critical review. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 2017. 24(3): p. 214-223. [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R., A. Di Bartolo, and N.T. Dintcheva, Matrix and Filler Recycling of Carbon and Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Review. Polymers, 2021. 13(21). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q., et al., Efficient and sustainable strategy for recycling of carbon fiber-reinforced thermoset composite waste at ambient pressure. Polymer, 2024. 297. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.H., et al., Recycling of natural fiber composites: Challenges and opportunities. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2022. 177. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.F., et al., Recycling of carbon fibers from carbon fiber reinforced polymer using electrochemical method. Composites Part a-Applied Science and Manufacturing, 2015. 78: p. 10-17. [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.Z., et al., Facile preparation, closed-loop recycling of multifunctional carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites. Composites Part B-Engineering, 2023. 257. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C., et al., Compressive performance of fiber reinforced polymer encased recycled concrete with nanoparticles. Journal of Materials Research and Technology-Jmr&T, 2021. 14: p. 2727-2738. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.H., et al., Recycling and Reutilizing Polymer Waste via Electrospun Micro/Nanofibers: A Review. Nanomaterials, 2022. 12(10). [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y. and G.S. Yang, Single Polymer Composites by Partially Melting Recycled Polyamide 6 Fibers: Preparation and Characterization. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2010. 118(6): p. 3357-3363. [CrossRef]

- Gregor-Svetec, D., et al., MONOFILAMENTS PRODUCED BY BLENDING VIRGIN WITH RECYCLED POLYPROPYLENE. Tekstil Ve Konfeksiyon, 2009. 19(3): p. 181-188.

- Jurumenha, M.A.G. and J.M.L. dos Reis, Fracture Mechanics of Polymer Mortar Made with Recycled Raw Materials. Materials Research-Ibero-American Journal of Materials, 2010. 13(4): p. 475-478. [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.C.M., et al., Sustainable waste recycling solution for the glass fibre reinforced polymer composite materials industry. Construction and Building Materials, 2013. 45: p. 87-94. [CrossRef]

- Clark, E., et al., Recycling carbon and glass fiber polymer matrix composite waste into cementitious materials. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2020. 155. [CrossRef]

- Dehghan, A., K. Peterson, and A. Shvarzman, Recycled glass fiber reinforced polymer additions to Portland cement concrete. Construction and Building Materials, 2017. 146: p. 238-250. [CrossRef]

- Dertinger, S.C., et al., Technical pathways for distributed recycling of polymer composites for distributed manufacturing: Windshield wiper blades. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2020. 157. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, F.A.C., et al., Polymer recycling in an open-source additive manufacturing context: Mechanical issues. Additive Manufacturing, 2017. 17: p. 87-105. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, A., et al., Potential and challenges of recycled polymer plastics and natural waste materials for additive manufacturing. Sustainable Materials and Technologies, 2024. 41. [CrossRef]

- Fico, D., et al., Sustainable Polymer Composites Manufacturing through 3D Printing Technologies by Using Recycled Polymer and Filler. Polymers, 2022. 14(18). [CrossRef]

- Habiba, R.D., C. Malça, and R. Branco, Exploring the Potential of Recycled Polymers for 3D Printing Applications: A Review. Materials, 2024. 17(12). [CrossRef]

- Maraveas, C., I.V. Kyrtopoulos, and K.G. Arvanitis, Evaluation of the Viability of 3D Printing in Recycling Polymers. Polymers, 2024. 16(8). [CrossRef]

- Pernica, J., et al., Mechanical Properties of Recycled Polymer Materials in Additive Manufacturing. Manufacturing Technology, 2022. 22(2): p. 200-203. [CrossRef]

- Pinho, A.C., A.M. Amaro, and A.P. Piedade, 3D printing goes greener: Study of the properties of post-consumer recycled polymers for the manufacturing of engineering components. Waste Management, 2020. 118: p. 426-434. [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.D.S., et al., Sustainable polymer reclamation: recycling poly(ethylene terephthalate) glycol (PETG) for 3D printing applications. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Engineering, 2024. 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Olawumi, M.A., B.I. Oladapo, and T.O. Olugbade, Evaluating the impact of recycling on polymer of 3D printing for energy and material sustainability. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2024. 209. [CrossRef]

- Mantelli, A., et al., UV-Assisted 3D Printing of Polymer Composites from Thermally and Mechanically Recycled Carbon Fibers. Polymers, 2021. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Alsewailem, F.D. and S.A. Aljlil, RECYCLED POLYMER/CLAY COMPOSITES FOR HEAVY-METALS ADSORPTION. Materiali in Tehnologije, 2013. 47(4): p. 525-529.

- Hunt, E.J., et al., Polymer recycling codes for distributed manufacturing with 3-D printers. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2015. 97: p. 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Achilias, D.S., P. Megalokonomos, and G.P. Karayannidis, CURRENT TRENDS IN CHEMICAL RECYCLING OF POLYOLEFINS. Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology, 2006. 7(2): p. 407-413.

- Datta, J. and P. Kopczynska, From polymer waste to potential main industrial products: Actual state of recycling and recovering. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2016. 46(10): p. 905-946. [CrossRef]

- Vouvoudi, E.C. and D.S. Achilias, Polymer packaging waste recycling: study of the pyrolysis of two blends via TGA. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2020. 142(5): p. 1891-1895. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.B., et al., Advances in Microwave-Assisted Polymer Recycling. Acta Polymerica Sinica, 2022. 53(9): p. 1032-1040. [CrossRef]

- Vichare, P., et al., Chemical recycling of polymer composites induced by selective variable frequency microwave heating. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2024. 141(3). [CrossRef]

- Adam, M., et al., Understanding microwave interactions with polymers to enable advanced plastic chemical recycling. Polymer Testing, 2024. 137. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., et al., Polymer waste recycling over “used” catalysts. Catalysis Today, 2002. 75(1-4): p. 247-255. [CrossRef]

- Chanda, M., Chemical aspects of polymer recycling. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 2021. 4(3): p. 133-150. [CrossRef]

- Gobin, K. and G. Manos, Polymer degradation to fuels over microporous catalysts as a novel tertiary plastic recycling method. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2004. 83(2): p. 267-279. [CrossRef]

- Braido, R.S., L.E.P. Borges, and J.C. Pinto, Chemical recycling of crosslinked poly(methyl methacrylate) and characterization of polymers produced with the recycled monomer. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 2018. 132: p. 47-55. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, W., M. Predel, and A. Sadiki, Feedstock recycling of polymers by pyrolysis in a fluidised bed. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2004. 85(3): p. 1045-1050. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y. and Y.W. Ma, Chemical Recycling of Step-Growth Polymers Guided by Le Chatelier’s Principle. Acs Engineering Au, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tsuneizumi, Y., et al., Chemical recycling of poly(lactic acid)-based polymer blends using environmentally benign catalysts. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2010. 95(8): p. 1387-1393. [CrossRef]

- Ichiura, H., H. Nakaoka, and T. Konishi, Recycling disposable diaper waste pulp after dehydrating the superabsorbent polymer through oxidation using ozone. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020. 276. [CrossRef]

- Utekar, S., et al., Comprehensive study of recycling of thermosetting polymer composites - Driving force, challenges and methods. Composites Part B-Engineering, 2021. 207. [CrossRef]

- Sachin, E.K., N. Muthu, and P. Tiwari, Hybrid recycling methods for fiber reinforced polymer composites: A review. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J., et al., Reusing recycled fibers in high-value fiber-reinforced polymer composites: Improving bending strength by surface cleaning. Composites Science and Technology, 2012. 72(11): p. 1298-1303. [CrossRef]

- Henry, L., et al., Semi-continuous flow recycling method for carbon fibre reinforced thermoset polymers by near- and supercritical solvolysis. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2016. 133: p. 264-274. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.H., W.H. Liu, and Z.F. Liu, An additive manufacturing-based approach for carbon fiber reinforced polymer recycling. Cirp Annals-Manufacturing Technology, 2020. 69(1): p. 33-36. [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S., B.R. Pinkard, and I.V. Novosselov, Recycling of carbon fiber reinforced polymers in a subcritical acetic acid solution. Heliyon, 2022. 8(12). [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.W., et al., Comparison of the Characteristics of Recycled Carbon Fibers/Polymer Composites by Different Recycling Techniques. Molecules, 2022. 27(17). [CrossRef]

- Torkaman, N.F., W. Bremser, and R. Wilhelm, Catalytic Recycling of Thermoset Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymers. Acs Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2024. 12(20): p. 7668-7682. [CrossRef]

- Nishida, H., Development of materials and technologies for control of polymer recycling. Polymer Journal, 2011. 43(5): p. 435-447. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.C., et al., Recycling strategies for vitrimers. International Journal of Smart and Nano Materials, 2022. 13(3): p. 367-390. [CrossRef]

- Liguori, A. and M. Hakkarainen, Designed from Biobased Materials for Recycling: Imine-Based Covalent Adaptable Networks. Macromol Rapid Commun, 2022. 43(13): p. e2100816. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., F. Picchioni, and R.K. Bose, Electrically and thermally healable nanocomposites via one-step Diels-Alder reaction on carbon nanotubes. Polymer, 2023. 283. [CrossRef]

- Orozco, F., et al., Diels-Alder-based thermo-reversibly crosslinked polymers: Interplay of crosslinking density, network mobility, kinetics and stereoisomerism. European Polymer Journal, 2020. 135. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M., et al., Diels(-)Alder-Crosslinked Polymers Derived from Jatropha Oil. Polymers (Basel), 2018. 10(10). [CrossRef]

- Yuliati, F., et al., Thermally Reversible Polymeric Networks from Vegetable Oils. Polymers (Basel), 2020. 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Polgar, L.M., et al., Kinetics of cross-linking and de-cross-linking of EPM rubber with thermoreversible Diels-Alder chemistry. European Polymer Journal, 2017. 90: p. 150-161. [CrossRef]

- Polgar, L.M., et al., Use of Diels–Alder Chemistry for Thermoreversible Cross-Linking of Rubbers: The Next Step toward Recycling of Rubber Products? Macromolecules, 2015. 48(19): p. 7096-7105. [CrossRef]

- van den Tempel, P., F. Picchioni, and R.K. Bose, Designing End-of-Life Recyclable Polymers via Diels-Alder Chemistry: A Review on the Kinetics of Reversible Reactions. Macromol Rapid Commun, 2022. 43(13): p. e2200023. [CrossRef]

- Flory, P., Molecular Size Distribution in Three Dimensional Polymers. Journal of American Chemical Society, 1941. 63: p. 3083–3090. [CrossRef]

- Stockmayer, W.H., Theory of Molecular Size Distribution and Gel Formation in Branched-Chain Polymers. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 1943. 11(2): p. 45-55. [CrossRef]

- Cuvellier, A., et al., The influence of stereochemistry on the reactivity of the Diels–Alder cycloaddition and the implications for reversible network polymerization. Polymer Chemistry, 2019. 10(4): p. 473-485. [CrossRef]

- Terryn, S., et al., Structure–Property Relationships of Self-Healing Polymer Networks Based on Reversible Diels–Alder Chemistry. Macromolecules, 2022. 55(13): p. 5497-5513. [CrossRef]

- Safaei, A., et al., The Influence of the Furan and Maleimide Stoichiometry on the Thermoreversible Diels-Alder Network Polymerization. Polymers (Basel), 2021. 13(15). [CrossRef]

- van den Tempel, P., et al., Looping and gelation kinetics in reversible networks based on furan and maleimide. Materials Today Chemistry, 2024. 42. [CrossRef]

- McReynolds, B.T., et al., Understanding the Effect of Side Reactions on the Recyclability of Furan-Maleimide Resins Based on Thermoreversible Diels-Alder Network. Polymers (Basel), 2023. 15(5). [CrossRef]

- Orozco, F., et al., Maleimide Self-Reaction in Furan/Maleimide-Based Reversibly Crosslinked Polyketones: Processing Limitation or Potential Advantage? Molecules, 2021. 26(8). [CrossRef]

- van den Tempel, P., et al., Beyond Diels-Alder: Domino reactions in furan-maleimide click networks. Polymer, 2023. 274. [CrossRef]

- Beljaars, M., et al., Bio-Based Aromatic Polyesters Reversibly Crosslinked via the Diels–Alder Reaction. Applied Sciences, 2022. 12(5). [CrossRef]

- Briou, B., B. Ameduri, and B. Boutevin, Trends in the Diels-Alder reaction in polymer chemistry. Chem Soc Rev, 2021. 50(19): p. 11055-11097. [CrossRef]

- Tesoro, g.S., Vinod, Synthesis of Siloxane-Containing Bis(furans) and Polymerization with Bis(maleimides). Ind. Eng. Chem. Prod. Res. Dev. , 1986. 25: p. 444-448. [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.J., B. Drain, and C.R. Becer, Exploring Polymeric Diene-Dienophile Pairs for Thermoreversible Diels-Alder Reactions. Macromolecules, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Raut, S.K., et al., Covalent adaptable network in an anthracenyl functionalised non-olefinic elastomer; a new class of self-healing elastomer coupled with fluorescence switching. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2023. 453. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H., S.-R. Shin, and D.-S. Lee, Self-healing of cross-linked PU via dual-dynamic covalent bonds of a Schiff base from cystine and vanillin. Materials & Design, 2019. 172. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., et al., Robust, Fire-Safe, Monomer-Recovery, Highly Malleable Thermosets from Renewable Bioresources. Macromolecules, 2018. 51(20): p. 8001-8012. [CrossRef]

- Costa Cornellà, A., et al., Self-Healing, Recyclable, and Degradable Castor Oil-Based Elastomers for Sustainable Soft Robotics. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2023. 11(8): p. 3437-3450. [CrossRef]

- Toncelli, C., et al., Properties of Reversible Diels–Alder Furan/Maleimide Polymer Networks as Function of Crosslink Density. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 2012. 213(2): p. 157-165. [CrossRef]

- Geng, H., et al., Vanillin-Based Polyschiff Vitrimers: Reprocessability and Chemical Recyclability. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2018. 6(11): p. 15463-15470. [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y., et al., Oxime-Urethane Structure-Based Dynamically Crosslinked Polyurethane with Robust Reprocessing Properties. Macromol Rapid Commun, 2022. 43(13): p. e2100781. [CrossRef]

- Marco-Dufort, B. and M.W. Tibbitt, Design of moldable hydrogels for biomedical applications using dynamic covalent boronic esters. Materials Today Chemistry, 2019. 12: p. 16-33. [CrossRef]

- Caillaud, K. and C. Ladavière, Water-Soluble (Poly)acylhydrazones: Syntheses and Applications. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 2022. 223(15). [CrossRef]

- Van Lijsebetten, F., et al., A Highly Dynamic Covalent Polymer Network without Creep: Mission Impossible? Angew Chem Int Ed Engl, 2022. 61(48): p. e202210405. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. and L.A. Connal, Biobased Transesterification Vitrimers. Macromolecular Rapid Communications, 2023. 44(7): p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Montarnal, D., et al., Silica-Like Malleable Materials from Permanent Organic Networks. Science, 2011. 334: p. 965–958. [CrossRef]

- Taplan, C., et al., Fast processing of highly crosslinked, low-viscosity vitrimers. Materials Horizons, 2020. 7(1): p. 104-110. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., et al., Catalyst-Free Self-Healing Bio-Based Polymers: Robust Mechanical Properties, Shape Memory, and Recyclability. J Agric Food Chem, 2021. 69(32): p. 9338-9349. [CrossRef]

- Mu, S., et al., Recyclable and Mechanically Robust Palm Oil-Derived Epoxy Resins with Reconfigurable Shape-Memory Properties. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 2020. 8(13): p. 5296-5304. [CrossRef]

- Memon, H. and Y. Wei, Welding and reprocessing of disulfide-containing thermoset epoxy resin exhibiting behavior reminiscent of a thermoplastic. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2020. 137(47). [CrossRef]

- Patachia, S., et al., COLORS DISTRIBUTION IN POLYMER WASTES AND COLOR PREDICTION OF RECYCLED POLYMERS. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, 2019. 18(5): p. 1039-1048. [CrossRef]

- Signoret, C., et al., MIR spectral characterization of plastic to enable discrimination in an industrial recycling context: I. Specific case of styrenic polymers. Waste Management, 2019. 95: p. 513-525. [CrossRef]

- Pavon, C., et al., Identification of biodegradable polymers as contaminants in the thermoplastic recycling process. Dyna, 2021. 96(4): p. 415-421. [CrossRef]

- Scott, G., ‘Green’ polymers. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2000. 68(1): p. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Samper, M.D., et al., Interference of Biodegradable Plastics in the Polypropylene Recycling Process. Materials, 2018. 11(10). [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.Y.N., et al., Review of polymer technologies for improving the recycling and upcycling efficiency of plastic waste. Chemosphere, 2023. 320. [CrossRef]

- Podara, C., et al., Recent Trends of Recycling and Upcycling of Polymers and Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Recycling, 2024. 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D., et al., Toward Sustainable Polymer Materials for Rechargeable Batteries: Utilizing Natural Feedstocks and Recycling/Upcycling of Polymer Waste. Chemsuschem, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jeziórska, R., B. Swierz-Motysia, and A. Szadkowska, MODIFIERS APPLIED IN POLYMER RECYCLING: PROCESSING, PROPERTIES AND APPLICATION. Polimery, 2010. 55(10): p. 748-756. [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, F.A., et al., Reactive Extrusion Grafting of Glycidyl Methacrylate onto Low-Density and Recycled Polyethylene Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Applied Sciences-Basel, 2022. 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Lahtela, V., et al., The Effects of Bromine Additives on the Recyclability of Injection Molded Electronic Waste Polymers. Global Challenges, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Schlummer, M. and A. Mäurer, Recycling of styrene polymers from shredded screen housings containing brominated flame retardants. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 2006. 102(2): p. 1262-1273. [CrossRef]

- Riess, M., et al., Analysis of flame retarded polymers and recycling materials. Chemosphere, 2000. 40(9-11): p. 937-941. [CrossRef]

- Möller, J., E. Strömberg, and S. Karlsson, Comparison of extraction methods for sampling of low molecular compounds in polymers degraded during recycling. European Polymer Journal, 2008. 44(6): p. 1583-1593. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Alfonso, J.E., et al., Influence of some processing variables on the rheological properties of lithium lubricating greases modified with recycled polymers. International Journal of Materials & Product Technology, 2012. 43(1-4): p. 184-200. [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.X., et al., Precisely Tailoring and Renewing Polymers: An Efficient Strategy for Polymer Recycling. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 2022. 223(19). [CrossRef]

- Andraju, N., et al., Machine-Learning-Based Predictions of Polymer and Postconsumer Recycled Polymer Properties: A Comprehensive Review. Acs Applied Materials & Interfaces, 2022. 14(38): p. 42771-42790. [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y. and H. Okamoto, Estimation method to achieve desired mechanical properties with minimum virgin polymer in plastics recycling. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 2024. 211. [CrossRef]

- van Gisbergen, J. and J. den Doelder, Processability predictions for mechanically recycled blends of linear polymers. Journal of Polymer Engineering, 2020. 40(9): p. 771-781. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.R., Polymer recycling: Economic realities, in Plastics, Rubber, and Paper Recycling: A Pragmatic Approach, C.P. Rader, et al., Editors. 1995. p. 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Synyuk, O., et al., Development of Equipment for Injection Molding of Polymer Products Filled with Recycled Polymer Waste. Polymers, 2020. 12(11). [CrossRef]

- Erenkov, O.Y. and D.O. Yavorskiy, Modernized Design of a Polymer Recycling Unit. Chemical and Petroleum Engineering, 2023. 58(9-10): p. 795-797. [CrossRef]

- Karuppaiah, C., N. Vasiljevic, and Z. Chen, Circular Economy of Polymers - Electrochemical Recycling and Upcycling. Electrochemical Society Interface, 2021. 30(3): p. 55-58. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.K., G. McNally, and A. Clarke, Automatic extruder for processing recycled polymers with ultrasound and temperature control system. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part E-Journal of Process Mechanical Engineering, 2016. 230(5): p. 355-370. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.K., G. McNally, and A. Clarke, Real time measurement and control of viscosity for extrusion processes using recycled materials. Polymer Degradation and Stability, 2014. 102: p. 212-221. [CrossRef]

- Pachner, S., M. Aigner, and J. Miethlinger, A heuristic method for modeling the initial pressure drop in melt filtration using woven screens in polymer recycling. Polymer Engineering and Science, 2019. 59(6): p. 1105-1113. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A., et al., The role of paradigms and technical strategies for implementation of the circular economy in the polymer and composite recycling industries. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 2023. 6(1): p. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Rejewski, P. and J. Kijenski, WASTE POLYMERS - AN AVAILABLE AND PERSPECTIVE RAW MATERIALS FOR RECYCLING PROCESSES. Polimery, 2010. 55(10): p. 711-717. [CrossRef]

| Chemistry | T (°C) | Method | Comments | reference |

| Diels-Alder: furan-maleimide cross-linked castor oil | 130 | Free flow into mould | three cycles | [257] |

| Diels-Alder: furan-maleimide cross-linked polyketones | 120–150 | Dynamic mechanical thermal analysis | seven cycles | [258] |

| Diels-Alder: furan-maleimide crosslinked EPDM rubber | 175 | Hot pressing | One cycle shown in tensile tests | [239] |

| Schiff base: Vanillin based | 50 °C | Acid hydrolysis | Shown once with NMR | [259] |

| Schiff base: Vanillin based | 170 °C | Hot pressing | three cycles | [255] |

| Oximes | 155 °C | Hot pressing | four cycles | [260] |

| Chemistry | Temperature | Method | Comments | reference |

| Trans-esterification: fractionated lignin and sebacic acid | 160 °C | Hot pressing | Zn(acac)2 as catalyst | [267] |

| Trans-esterification: palm oil based epoxy and citric acid | 170 °C | Hot pressing | Catalyst free | [268] |

| Di-sulfide metathesis | 180 | Hot pressing | Three cycles, welding performance tested | [269] |

| Polyurethane | 150 | Extrusion | Twin-screw extrusion, one cycle | [266] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).