Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Treatment Process

2.2. Heat Treatment Process and Fatigue Properties Testing

2.3. Microstructure Characterization

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Effect of Aging Temperature on Multi-Level Microstructures of TC21 Alloy

3.2. Effect of Aging Temperature on on the Notch Tensile Properties of TC21 Alloy

3.3. Microvoids and Microcracks Features below the Main Crack Initiation Region

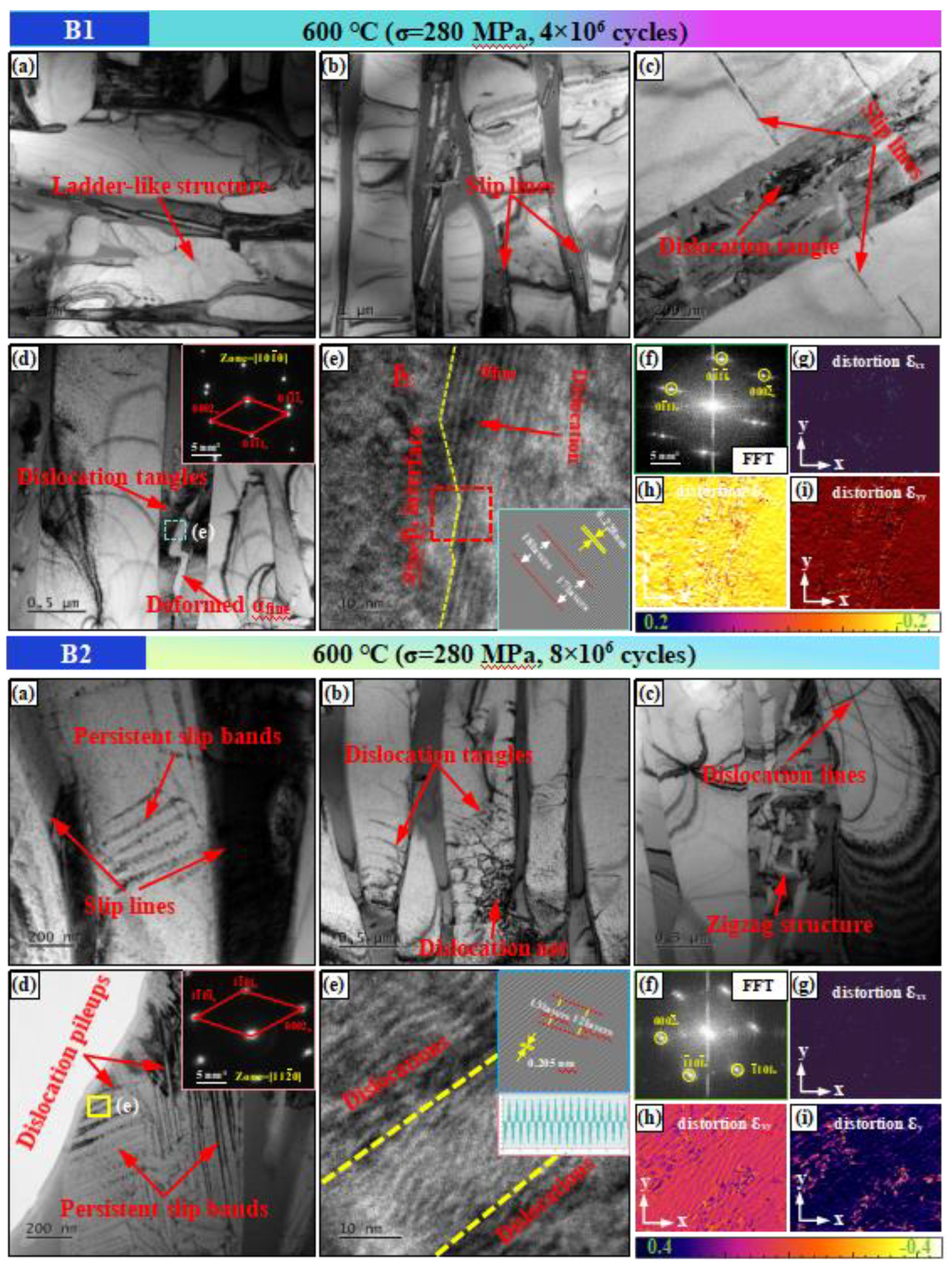

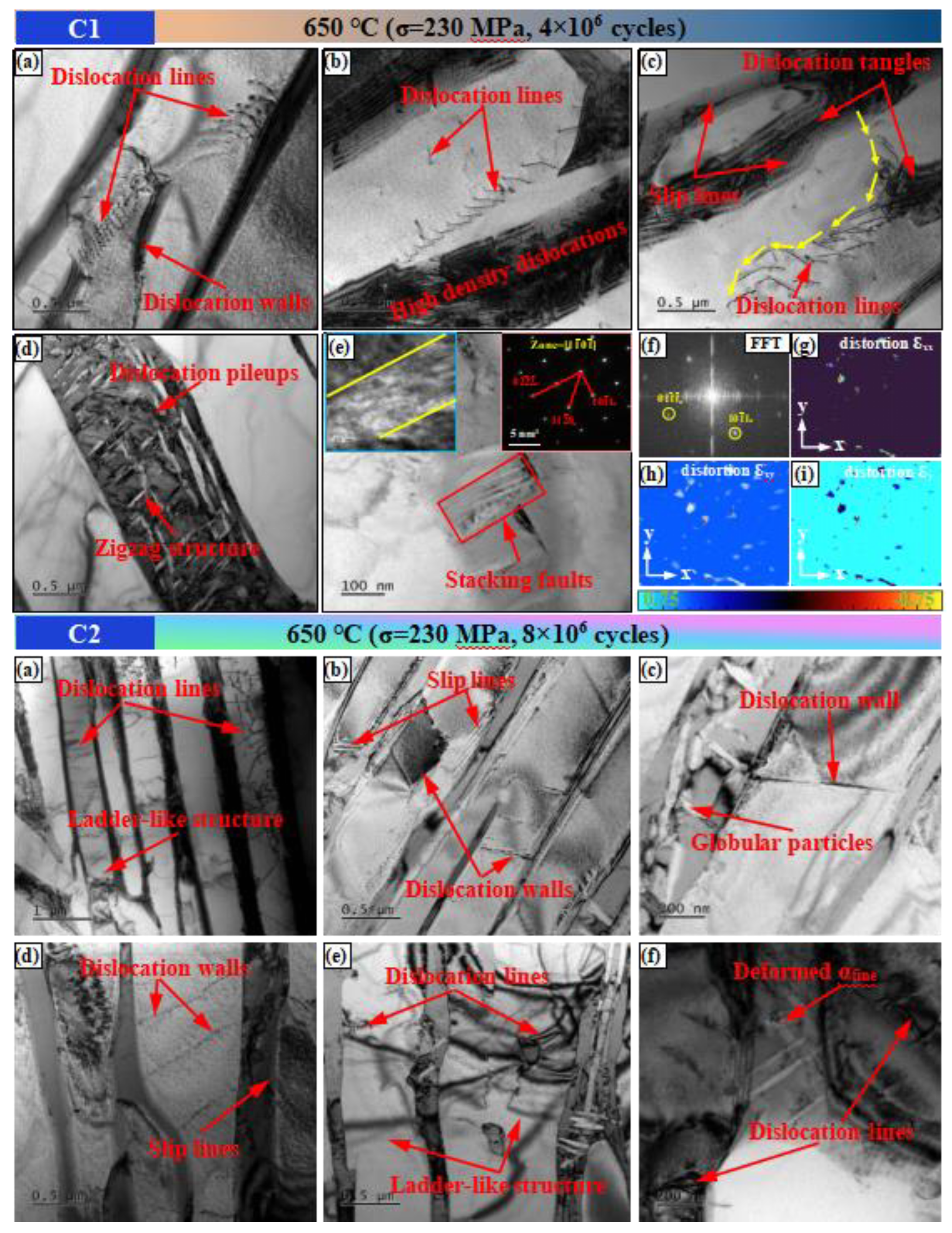

3.4. Dislocation Structures in NHCF Specimens of TC21 Alloy with MLMs

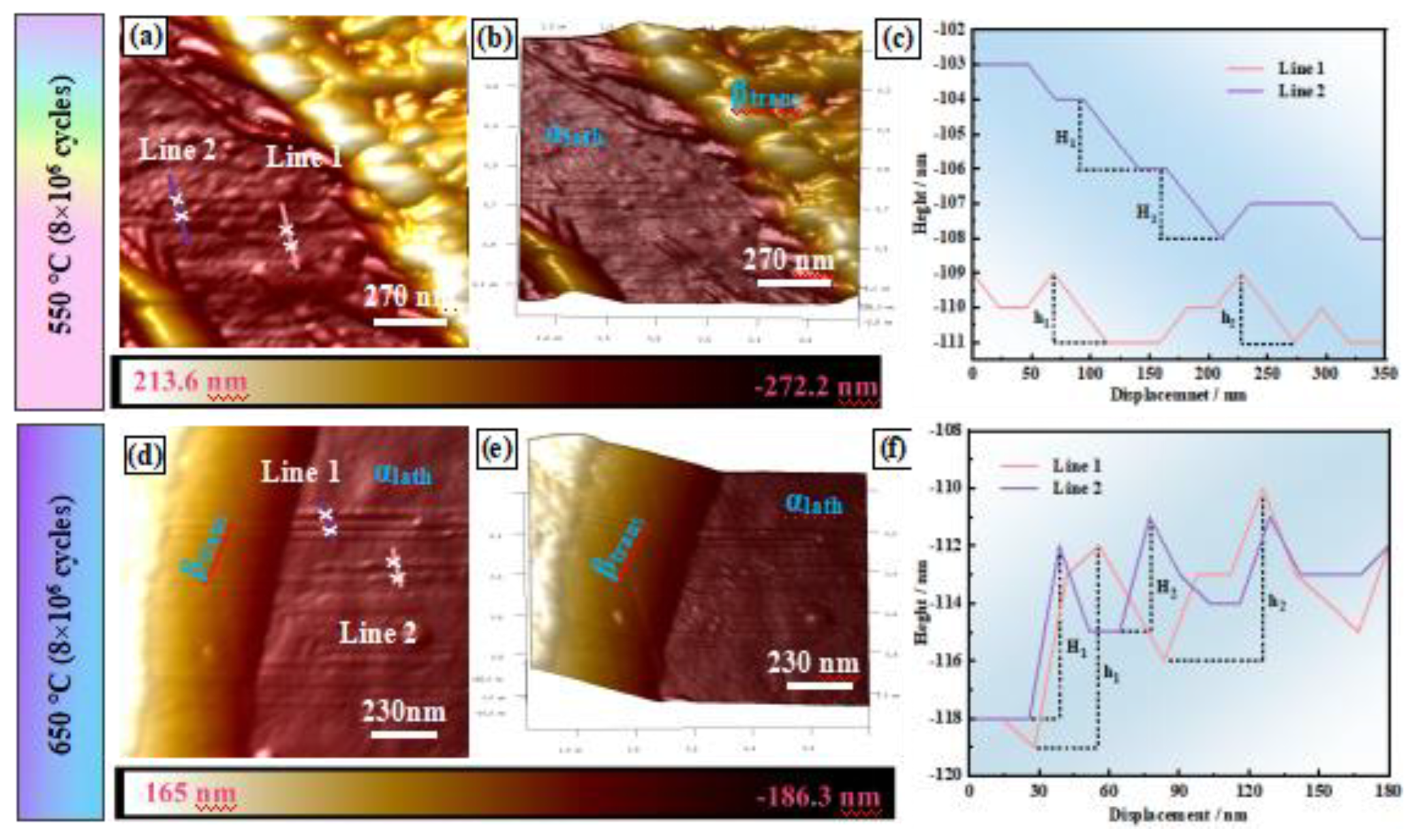

3.5. The Slip Behavior of Dislocations within the αlath of TC21alloy with MLMs

4. Conclusions

- The width of αc and GBα, the size of αfine, and the content of αlath increase as aging temperature increases, while the thickness of αlath and the content of αfine decrease. The notched tensile strengths of the TC21 alloy were determined to be 1580, 1650, and 1577 MPa with an increase in aging temperature, while the corresponding notched fatigue strengths were 240, 280, and 230 MPa respectively.

- The notch alters the stress distribution at the root, resulting in localized plastic deformation and stress relaxation at the notch root, which enhances the strength of the alloy but also exacerbates brittle fracture occurrence. The increase in grain boundaries is the primary driving factor for fracture propagation along the GBα.

- When the αlath is thicker and the αfine is smaller, micro-voids and micro-cracks primarily form along the twist deformed interfaces of αlath/βtrans and αfine/βr, gradually spreading along these interfaces. As the sizes of GB α and αfine increase and the thickness of α lath decreases, micro-voids and micro-cracks emerge not only at the αlath/βtrans interface under twist deformation but also within GB α, characterized by relatively large localized plastic deformation regions. These micro-voids and micro-cracks propagate along the αlath/βtrans interface or penetrate through the αlath, creating lengthy zigzag cracks that eventually result in specimen fracture.

- The deformation and fracture behavior of αfine is influenced by their size. Larger αfine release dislocations upon fracture, which decreases the density of dislocations accumulated at the αfine/βr interface. Conversely, a thicker αlath allows for the buildup and propagation of dislocations along the αlath/βr interface, resulting in the formation of numerous micro-voids that coalesce along the interface, creating micro-cracks. In contrast, a thinner αlath initiates different dislocation systems at the αlath/βtrans interface. These dislocations propagate into the interior of the αlath at an angle to the interface, forming PSBs and dislocation walls within the αlath, intensifying local hardening and promoting the development of micro-voids and micro-cracks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hodgson, P.; Birbilis, N.; Weyland, M.; Fraser, H.L.; Lim, S.C.V.; Peng, H.; Yang, R.; Wang, H.; Huang, A. Ultrastrong nanotwinned titanium alloys through additive manufacturing. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Wu, M.; Yan, Z.; Li, D.; Xin, R.; Liu, Q. Dynamic restoration and deformation heterogeneity during hot deformation of a duplex-structure TC21 titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2018, 712, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Sun, Q.; Xin, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Wan, M.; Zeng, W.; Zhao, Y. High-strength titanium alloys for aerospace engineering applications: A review on melting-forging process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2022, 845, 143260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zeng, W.; Ma, H.; Zhang, F.; Xu, L.; Liang, X.; Zhao, Y. Research on tensile anisotropy of Ti-22Al-25Nb alloy isothermally forged in B2 phase region related with texture and variant selection. Mater. Charact. 2023, 201, 112899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, A.V.; Raab, G.I.; Semenova, I.P.; Valiev, R.Z. Notched fatigue and impact toughness. Mater. Lett. 2021, 302, 130366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Qiu, D.; Gibson, M.A.; Zheng, Y.; Fraser, H.L.; StJohn, D.H.; Easton, M.A. Additive manufacturing of ultrafine-grained high-strength titanium alloys. Nature 2019, 576, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, S.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Arora, P.; Chattopadhyay, J. Fatigue experiments and life predictions of notched C-Mn steel tubes. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 165, 1075027. [Google Scholar]

- Cavuoto, R.; Lenarda, P.; Msseroni, D.; Paggi, M.; Bigoni, D. Failure through crack propagation in components with holes and notches: An experimental assessment of the phase field model. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2022, 257, 111798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, A.M.; Vázquez, J.; Navarro, C.; Domínguez, J. Fatigue behavior of notched and unnotched AM Scalmalloy specimens subjected to different surface treatments. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 181, 108146. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Pei, X.; Wang, P.; Dong, P.; Wang, B.; Xie, X. Notch structural stress theory: Part II predicting total fatigue lives of notched structuresInternational. Int. J. Fatigue. 2024, 182, 108201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haritos, G.K.; Nicholas, T.; Lanning, D.B. Notch size effects in HCF behavior of Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Fatigue. 1999, 21, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuri, T.; Ono, Y.; Ogata, T. Effects of surface roughness and notch on fatigue properties for Ti–5Al–2. 5Sn ELI alloy at cryogenic temperatures. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mat 2003, 4, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Kou, H.; Chen, N.; Zhang, M.; Hua, K.; Fan, J.; Tang, B.; Li, J. Duality of the fatigue behavior and failure mechanism in notched specimens of Ti-7Mo-3Nb-3Cr-3Al alloy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 50, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Long, S.; Tan, C.; Wan, M.; Liu, D.; Ji, S.; Zeng, W. Influence of notch root radius on high cycle fatigue properties and fatigue crack initiation behavior of Ti-55531 alloy with a multilevel lamellar microstructure. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 6293–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Deng, C.; Gong, B.; He, Y.; Wang, D. Fatigue limit prediction of notched plates using the zero-point effective notch stress method. Int. J. Fatigue. 2021, 151, 106392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beber, V.C.; Schneider, B. Fatigue of structural adhesives under stress concentrations: Notch effect on fatigue strength, crack initiation and damage evolution. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 140, 105824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Zhao, Z.; Ouyang, Y.; Chen, D.; Chen, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, S. Effect of low cycle fatigue predamage on very high cycle fatigue behavior of TC21 titanium alloy. Materials 2017, 10, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.; Li, X.; Sun, Q.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J. Effect of α-phase morphology on low-cycle fatigue behavior of TC21 alloy. Int. J. Fatigue. 2015, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hémery, S.; Stinville, J.C.; Wang, F.; Charpagne, M.A.; Emigh, M.G.; Pollock, T.M.; Valle, V. Strain localization and fatigue crack formation at (0001) twist boundaries in titanium alloys. Acta. Mater. 2021, 219, 117227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Dang, N.; Wang, X. The effect of laser shock peening, shot peening and their combination on the microstructure and fatigue properties of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 153, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, B.; Chen, D.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Meng, Y.; Gao, G. Notch effect on the fatigue behavior of a TC21 titanium alloy in very high cycle regime. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wan, M.; Huang, C.; Lei, M.; Jian, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, D.; Huang, F. Effect of aging temperature on mechanical properties of TC21 alloy with multi-level lamellar microstructure, Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2022, 840, 142825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, L.; Li, C.; Hui, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Guo, S.; Li, J. Research progress on hot deformation behavior of high-strength beta titanium alloy: Flow behavior and constitutive model. Rare. Metals 2022, 41, 1434–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, G. Role of microstructure in plastic deformation and crack propagation behaviour of an α/β titanium alloy. Vaccum 2021, 183, 109848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Shan, D.; Zhao, Y.; Ge, P.; Zeng, W. Accordance between fracture toughness and strength difference in TC21 titanium alloy with equiaxed microstructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 664, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Jia, X.; Bao, Z.; Song, Y. Effect of notch geometry on the fatigue strength and critical distance of TC4 titanium alloy. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2017, 31, 4727–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Jiang, X.; Shuai, C.; Zhao, C.; He, D.; Chen, M.; Chen, C. Effects of initial microstructures on hot tensile deformation behaviors and fracture characteristics of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2018, 711, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Ou, M.; Mao, X.; Liang, Y. In situ deformation behavior of TC21 titanium alloy with different alpha morphologies (equiaxed/lamellar). Rare. Metals 2021, 40, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Nicholas, T. Notch size effects on high cycle fatigue limit stress of Udimet 720. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2003, 357, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ma, M.; Tan, Y.; Xiang, S.; Zhao, F.; Liang, Y. Microstructure and texture evolution of TB8 titanium alloys during hot compression. Rare. Metals 2021, 40, 2917–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.K.; Szczepanski, C.J.; John, R.; Larsen, M. Deformation heterogeneities and their role in life-limiting fatigue failures in a two-phase titanium alloy. Acta. Mater. 2015, 82, 378–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Xie, H.; Wang, H.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Wu, L. The geometric phase analysis method based on the local high resolution discrete Fourier transform for deformation measurement. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 025402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftink, B.P.; Li, A.; Szlufarska, I.; Mara, N.A.; Robertson, I.M. Deformation response of AgCu interfaces investigated by in situ and ex situ TEM straining and MD simulations. Acta. Mater. 2017, 138, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.S.; Liu, Y.; McCabe, R.J.; Wang, J.; Tomé, C.N. Quantifying elastic strain near coherent twin interface in magnesium with nanometric resolution. Mater. Character. 2020, 160, 110082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzinova, M.A.; Zherebtsov, S.V.; Klimenko, D.N.; Semiatin, S.L. The effect of β stabilizers on the structure and energy of α/β interfaces in titanium alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A. 2021, 52, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhong, B.; Huang, Q.; He, C.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y. Stress ratio effect on notched fatigue behavior of a Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V alloy in the very high cycle fatigue regime. Int. J. Fatigue 2018, 116, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, L.; Wang, Q.; Shao, X.; Chen, Q. Localized dislocation interactions within slip bands and crack initiation in Mg-10Gd-3Y-0. 3Zr. Int. J. Fatigue. 2021, 150, 106302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hémery, S.; Dang, V.T.; Signor, L.; Villechaise, P. Influence of microtexture on early plastic slip activity in Ti-6Al-4 V polycrystals. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2018, 49, 2048–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.W.; Dimlich, R.V.W.; Alexander, K.B.; McCarthy, J.J.; Pretlow, T.P.; Okerstrom, S.; Geng, W.; Kramer, D.; Gerberich, W. Slip Band Analysis by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). Microsc. Microanal. 1997, 3, 1273–1274. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Huang, C.; Zeng, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Wan, M.; Liu, D.; Ji, S.; Zeng, W. Deformation and fracture mechanisms of Ti-55531 alloy with a bimodal microstructure under the pre-tension plus torsion composite loading. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 7425–7443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, D.; Busolo, T.; Xu, X.; da Fonseca, J.Q.; Preuss, M. Effect of nanoscale α2 precipitation on strain localisation in a two-phase Ti-alloy. Acta. Mater. 2017, 129, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wen, H.; Xie, H.; Liu, C. Subset geometric phase analysis method for deformation evaluation of HRTEM images. Ultramicroscopy 2016, 171, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Elements | Al | Zr | Mo | Nb | V | Zn | Si | Ni | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content (%) | 5.91 | 2.44 | 3.27 | 2.22 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.1 | Bal. |

| Aging temperatures | UTS/MPa | YS/MPa | EL/% | σ-1(107)/MPa | σ-1(107)/UTS | σ-1(107)/YS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 550 ℃ | 1580±5 | 1067±2 | 2.32±0.4 | 240 | 0.152 | 0.225 |

| 600 ℃ | 1650±3 | 1099±5 | 1.52±0.5 | 280 | 0.170 | 0.255 |

| 650 ℃ | 1577±2 | 1095±3 | 1.80±0.3 | 230 | 0.146 | 0.210 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).