1. Introduction

Intellectual disability (ID) is characterized by significant limitations both in intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior as expressed in conceptual, social, and practical adaptive skills. This disability originates during the developmental period, which is defined operationally as before the individual attains age twenty-two ([

1]. ID is a developmental disorder and since is a very heterogeneous group, is usually clinically assessed with appropriately normed, standardized and validated tests of intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior which are individually administered [

2,

3,

4]. Measured IQ is considered an approximation of intellectual functioning, which may or may not necessarily correlate with the level of adaptive functioning [

4]. According to multiple epidemiological studies, individuals with an IQ score of 50 or below are classified as having severe intellectual disability, whereas those with an IQ score exceeding 50 are classified as having mild intellectual disability [

5]. Down syndrome (DS) is a common chromosomal abnormality that can result in various limitations [

6]. Individuals with DS often exhibit lower physical fitness (PF) levels compared to those with ID alone [

7]. Reduced physical activity (PA) and age-related factors contribute to lower levels of PF in people with ID [

8]. Due to the nature of ID, motor function is often impaired, requiring tailored physical development strategies ([

9].

People with ID exhibit significantly lower muscular strength (MS) than their typically developing peers. For male athletes, this difference is 9%, while for female athletes, it is 19%. Furthermore, strength differences of up to 40% have been reported for untrained individuals with ID [

7,

10]. Improved MS has a positive impact on muscle tone and functionality, enhancing overall movement quality [

11]. Heart rate (HR), which is associated with PA, determines energy expenditure and exercise intensity. People with ID typically have lower cardiovascular endurance compared to those without disabilities [

12]. The evaluation of effort and endurance is vital in exercise program design, and maximum heart rate (HRmax) is a key factor in this assessment. It has been observed that people with ID often have a lower HRmax [

12].

Swimming is particularly important for people with ID due to the supportive aquatic environment that facilitates movement, especially for those facing gravity-related limitations [

13]. Research on the effects of swimming on ID is limited [

14]. People with ID benefit from improved cardiorespiratory and muscular endurance, speed, balance, and agility in the water [

15,

16]. Marques-Aleixo et al. (2013) found that swimmers with ID showed distinctive differences in swimming performance (SP) and MS [

17]. Elite swimmers with ID face challenges in speed, particularly during turns, compared to swimmers without ID [

18]. Swimmers with ID often encounter challenges in adopting a strategic approach during competitive events, a factor that can adversely impact their performance outcomes [

17].

Detraining (DT) is the partial or complete loss of training adaptations that affect performance, as well as one’s anatomical and physiological levels [

19]. This observation aligns with the principle of reversibility, which posits that cessation or reduction in training intensity can lead to a regression in physical conditioning. Specifically, the physiological and anatomical adaptations acquired during the preparatory phase are transient and may diminish or revert if the training stimulus is insufficient or discontinued. Consequently, in instances of illness, injury, or rest following a training period, detraining may reverse prior training adaptations, thereby adversely affecting performance parameters. Therefore, athletes should plan their return to training after rest periods to mitigate any measurable reductions in performance capacity [

20]. DT can result in a decrease in PF, affecting both cardiopulmonary endurance and MS. The extent of these effects may vary depending on the individual’s level of training [

21].

Research on sports for individuals with intellectual disabilities remains limited, particularly regarding competitive swimming [

22,

23,

24]. The challenges in assessing performance within aquatic environments, coupled with the necessary collaboration between athletes with ID and researchers, present complexities in research on this population. Examining the detraining period is crucial, as it not only diminishes performance levels but also induces physical adaptations. The limited availability of specialized studies on sports activities for individuals with ID highlights a significant research gap in this area [

21]. Therefore, exploring the effects of a three-month DT period on performance, strength, and heart rate in freestyle swimming among athletes with ID could contribute valuable insights [

25]. The aim of this study was to acquire new insights into the effects of a three-month detraining on body composition, muscular strength, heart rate, and performance among swimmers with intellectual disability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample size (n) required for this study was determined using G*Power 3.1.9.7 for Windows (G*power, University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). A sample size of 24 participants was determined to be necessary to detect significant differences with a 95% probability of rejecting the null hypothesis, assuming a medium to large effect size of 0.7 for one group and two measurements. The study involved 21 swimmers, consist of 16 males and 5 females, with a mean age of 26.2 years (range: 17.6-44.8 years). Of the participants, 15 were with ID and 6 with DS. All participants were designated as S14-class swimmers by the National Federation of Sports for People with Disabilities (EAOM-AmeA), specifically for swimming competitions within Greece [

26]. Their swimming experience ranged from 4 to 20 years. Each participant engaged in an eight-month training program comprising two or three one-hour sessions per week.

All participants had been diagnosed by a group of certified scientists, working at the official public Disability Certification Centers. Disability categorization into severe, moderate, or mild ID and DS was based on WISC-V GR test.

Table 1 illustrates the number of participants based on the outcomes of the assessment. The presence of a specific syndrome, such as DS, was included as a criterion for participant selection. The researchers’ acceptance by participants to ensure the accurate conduct of measurements constituted an additional criterion. Individuals with significant disabilities received training in small groups of no more than three. These individuals had been trained together for an extended period, which led to the absence of conflicts or issues.

The participants and their guardians were provided with a comprehensive briefing on the procedure, the objective of the task, and the intended utilization of the resulting data. Subsequently, the participants were requested to read and sign the letter of consent and participation in the study, which had been prepared in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, prior to the commencement of the experiment. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines set forth by the ethics committee of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Serres (ERC-010/2023, 02 October 2023). The athletes provided their consent for filming to facilitate the analysis of the results. To ensure anonymity, names were matched with codes.

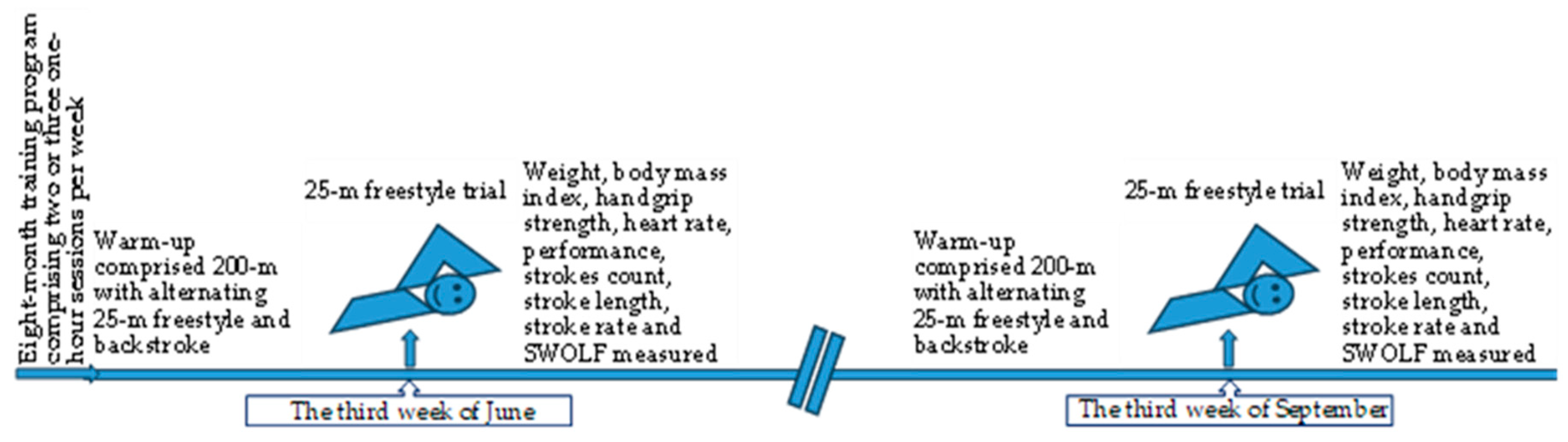

2.2. Measurement Procedure

Two measurements were taken on two occasions, three months apart, under identical conditions at the National Swimming Pool in Thessaloniki, Greece. The indoor pool was 25 meters in length and the temperature of the water and air were 27 and 25 degrees Celsius, respectively. The measurements were conducted by a doctoral student as part of her thesis, with the assistance of expert colleagues, coaches, and professors. A schematic diagram of the experimental protocol is presented in

Figure 1.

2.3. Anthropometrics and Performance Parameters

The participant’s date of birth was recorded along with their anthropometric measurements, including height measured with a Seca 213 stadiometer (Seca GmbH & Co. KG., Hamburg, Germany) and weight measured with a Xiaomi Mi Body Composition Scale 2 Smart (XIAOMI Inc., Pekuno, Beijing, China). The body mass index (BMI) was determined by dividing body weight, measured in kilograms, by the square of height, measured in meters.

The maximum force of each hand was measured using the TAKEI 5401 digital hand dynamometer (TAKEI, Japan) while the athletes were in a standing position. The athletes were required to complete two attempts on each arm with a 15-second interval between attempts, in accordance with the specifications of the Eurofit test [

7]. The hand was positioned in accordance with the natural joint angle, and the dynamometer was calibrated to the dimensions of the palm. The optimal performance of each hand was then determined based on these criteria, and subsequently, the average value of the handgrip force for both hands was calculated and considered.

Following a 30-minute recovery period, the subjects engaged in a typical warm-up routine. After 15 minutes, the time taken by the swimmers to complete a 25-m freestyle at maximum effort was recorded using a CASIO HS 30W handheld stopwatch (Casio America, Inc. USA). The warm-up comprised 200-m with alternating 25-m freestyle and backstroke. During the training period, participants engaged in multiple 25-m freestyle attempts within the program with the objective of enhancing their speed. Additionally, during the training session, the elastic strap of the heart rate monitor was applied to the chest to ascertain the intensity of the participants’ efforts. Following the DT period, the participants undertook one or two training sessions prior to the second trial with the aim of reacquainting themselves with the sensation of swimming in water. The athlete entered the pool, positioning one hand on the start bar of the starting block. Upon the coach’s signal, the swimmer commenced a 25-meter freestyle swim. HR was measured at four time points: pre-trial, immediately post-trial, and at one- and two-minutes post-trial using a Polar S410 heart rate monitor (Polar Electro Oy, Finland). The participant wore an elastic Polar chest strap with the HR monitor before, during, and for a brief period following the swim. Resting HR was recorded while participants sat on a chair poolside, following a minimum of five minutes of seated rest. At the conclusion of the trial, HR was measured while swimmers were in the water, and subsequently at one- and two-minutes post-trial as they returned to the seated position on the poolside chair.

2.4. Kinematic Analysis

A digital video camera with a sampling rate of 48 Hz (SJ4000 WiFi digital camera, SJCAM, Hong Kong) was placed at a high point on one side and in the middle of the pool [

27], twenty meters from the lanes where the swimmers performed their efforts, to record the entire 25-m distance [

28]. Before the trials, a 2 m long floating wand was placed in the center of the lane, 2 to 4 m from the wall. The length of the wand in pixels (as measured in screen coordinates) was used to provide an analogy of screen length to actual length. This analogy was used to transform the screen length to the actual length for the selected variable. The first 5 meters of the 25-m course were marked with a fixed rod out of the water and excluded from the total distance to ensure a fair measurement of the number of strokes (stroke count – SC20) due to differences in pushing and sliding among athletes. For each swimmer, the velocity (V20), stroke count (SC20), distance per stroke or stroke length (SL20), and stroke rate (SR20) during the final 20 meters of the 25-meter freestyle trial were calculated from recorded data. Additionally, the total time for the 25-meter trial (T25) and the total stroke count (SC25) were recorded. The performance index for each athlete, referred to as SWOLF, was calculated [

29]. SWOLF, a quantitative measure, originates from the amalgamation of “swimming” and “golf” [

30,

31]. Like golf, where a lower score signifies improved performance, SWOLF reflects performance in swimming by summing the total strokes taken to complete a specified distance (25 meters) and the time required to swim this distance (SWOLF = T25 + SC25). This index provides an indirect measure of performance, offering a valuable means of comparing training sessions within a single individual, rather than between different athletes.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The values are presented as mean (M) with standard deviation (SD). Shapiro-Wilk’s test was used to check the normal distribution of the data, while Levene’s test was used to test the homogeneity of variance. Paired t-tests were used for all parameters except HR, which was compared using one-way repeated measures ANOVA. A one-tailed p-value was used since the research hypothesis is the deterioration of the parameters tested [

32]. The effect size (Cohen’s d, ES) was classified as small (d = 0.20), medium (d = 0.50), and large (d ≥ 0.80). Correlation analysis was conducted using bivariate Pearson’s r analysis between the variables. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY, USA: IBM Corp). The level of significance was set at p=.05.

3. Results

The mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) are presented, along with the level of significance and Cohen’s d.

3.1. Anthropometrics Parameters

The final measurement revealed a significant increase of 1.9% in the mean weight and 1.8% in the mean BMI of the participants (

p = 0.002, d = 2.13 huge;

p = 0.004, d = 0.74 large, respectively,

Table 2).

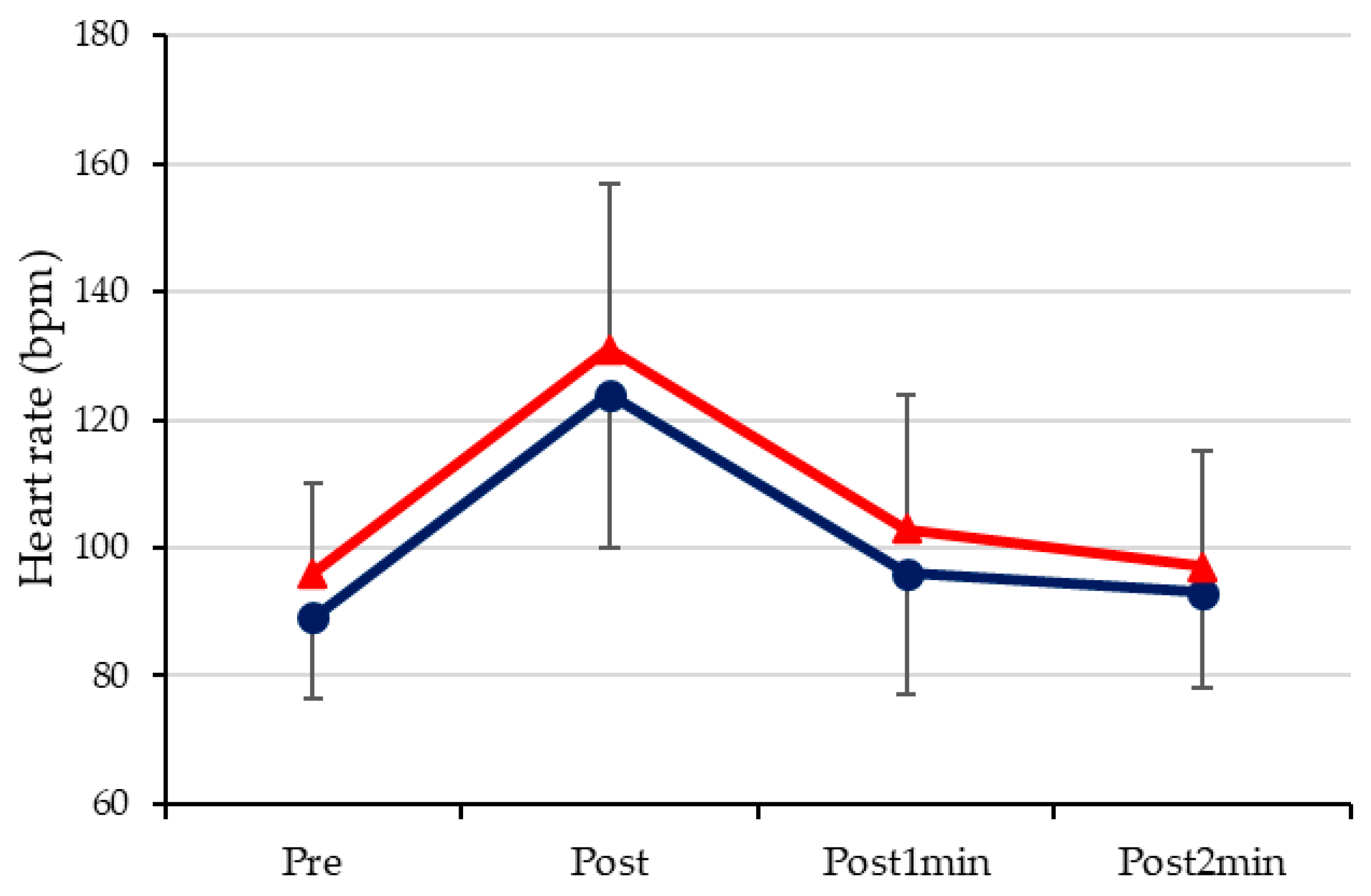

3.2. Heart Rate

Despite an approximate 6.4% increase in HR across all time points during the September trials, no statistically significant differences were observed in any measurements at any time point (

Figure 2). The recorded beats per minute were, on average, 92, 128, 99, and 95 before the trial, immediately after the trial, and at one- and two-minutes post-trial, respectively.

3.3. Performance and Kinematic Parameters

Table 3 shows the performance and kinematic parameters of the participants before and after the summer break. T25 increased significantly by 2.5 s (

p = 0.002, d = 3.48 huge). In the 20-m swim, the speed was reduced by 0.05 m*s

-1 (

p = 0.003, d = 0.08 huge), the SC increase by 1.4 cycles (

p = 0.003, d = 2.16 huge), the SL was reduced by 0.12 m (

p = <0.001, d = 0.13 small), but, the SR was remained around 35.4 cycles*min

-1 (

p = 0.491, d = 4.06 huge). The SC at 25-m increase by 1.5 cycles (

p = 0.003, d = 2.16 huge), and the SWOLF efficiency index worsened from 52.4 to 56.3 points (

p = <0.001, d = 4.84 huge).

There were no statistically significant differences between the two measures of handgrip strength, which was approximately 226 Ν (p = 0.070, d = 65.50 huge).

No significant correlations were observed between HR and any of the performance parameters across the total participant cohort during the study.

Table 4 presents the correlation analysis results, revealing that increased body weight was associated with a prolonged T25 in both measurements (r = 0.479, p = 0.028; r = 0.489, p = 0.024, respectively) and an inverse relationship with SR20 (r = -0.562, p = 0.008; r = -0.496, p = 0.022, respectively). BMI demonstrated a strong positive correlation with both elevated T25 and SWOLF (r = 0.731, p = 0.000; r = 0.703, p = 0.000 and r = 0.684, p = 0.001; r = 0.680, p = 0.001, respectively) across both measurements, but a negative association with SC20 (r = -0.537, p = 0.012) specifically in September. Additionally, HGS was negatively correlated with T25 across both measurements (r = -0.458, p = 0.037; r = -0.470, p = 0.032, respectively), and in September, HGS showed a positive correlation with SL20 (r = 0.551, p = 0.010) while presenting an inverse relationship with both SC20 and SWOLF (r = -0.475, p = 0.029; r = -0.488, p = 0.025, respectively).

4. Discussion

It is well established that cessation of training can lead to the reversal of training-induced adaptations, thereby impacting performance parameters. Specifically, detraining has been shown to result in declines in PF, notably in cardiopulmonary endurance and MS, with the extent of these declines depending on the individual’s baseline training level [

20,

21,

25]. While extensive research has examined this phenomenon among individuals without disabilities, the effects on individuals with ID remain largely unexplored. This study aims to advance understanding of the impacts of a three-month period of DT on body composition, strength, HR, and performance in swimmers with ID.

4.1. Anthropometrics Parameters

The present study examines the impact of DT on anthropometric measurements, specifically height, weight, and BMI. The mean height of the athletes was found to remain constant. Most participants exhibited an increase in weight and BMI, with a mean increase of 1.9% and 1.8%, respectively, over the course of the three-month DT period (

Table 2). At the outset of the study, 50% of the participants exhibited a normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), 25% were classified as overweight (BMI > 25–29.9 kg/m²), and the remaining participants were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²) [

33]. However, this status deteriorated following the observation of two individuals transitioning from a state of normal to that of overweight, with most participants exhibiting a shift in their BMI category. There is substantial evidence that regular exercise prevents weight gain and an increase in BMI [

34]. It is evident that the observed increase in weight and BMI was a consequence of the lack of regular exercise. These effects have been observed in individuals with ID, as well as in the general population [

35,

36,

37]. Although the present study did not record the health status of the participants before and after the DT period, it is established that weight gain and an increase in BMI can have a negative impact on the overall health of people with ID [

6,

38,

39].

4.2. Heart Rate

The objective was to measure HR to determine the intensity of cardiac effort during rest, after exercise, and at 1- and 2-minutes post-exercise. Additionally, the aim was to ascertain whether there were any changes in HR after DT. The results demonstrated no statistically significant differences in HR at rest or after the test. These findings are consistent with those of Zacca et al. (2019), who also observed that four weeks of DT were insufficient to induce alterations in myocardial structure.

The study revealed that there was an approximate 6.4% increase in HR in September in comparison to June (

Figure 2). Coyle et al. (1984) observed a 5% increase in HR in athletes who had undergone aerobic training after a period of 84 days during which they did not engage in any training [

41]. This finding suggests that DT may have a negative impact on cardiovascular fitness. The lack of cardiorespiratory training may be due to a slight loss of adaptations [

19]. The study found that the highest HR achieved during swimming was approximately 75% of the predicted HRmax, as calculated using the formula Y=189-(0.59*age) for subjects with ID or Y=210-[(0.56*age)-15.5] for subjects with DS [

12]. The findings indicated that the subjects were unable to reach the requisite exertion levels during the trial. Additionally, the data demonstrated that their HRmax was approximately 15 beats per minute lower than that observed in their peers without ID [

8]. Individuals with ID have been shown to exhibit lower HR levels in response to stress stimuli compared to the general population [

42]. This results in a plateau that may not be affected by abstinence from exercise.

The average time required to complete the 25-m swim was approximately 35 s in both measurement trials, which may not have been sufficient to produce a significant elevation in HR. However, the highest HR reached approximately 75% of the predicted maximum HR, indicating a relatively modest proportion. Notably, individuals with ID demonstrated a SR considerably lower than that of typical swimmers, averaging approximately 35 cycles per minute in this research compared to around 49 cycles per minute in López-Plaza et al. (2024) study [

29]. Interestingly, a similar proportion (~75%) was observed in SR and HR for individuals with ID relative to competitive swimmers. These results suggest that individuals with ID have a limited capacity for high-intensity swimming, leading to a less substantial increase in HR. Furthermore, no significant correlations were observed between HR and any performance parameters across the entire participant cohort in this study.

4.3. Performance, and Kinematic Parameters

There was a significant decline in performance of 2.5 seconds after DT consistently with a decrease in V20 by 0.05 m*s

-1. Research has shown that swimmers’ performance can be negatively affected by interruptions in training lasting either 4-6 weeks or longer than 10 weeks [

40,

43]. Głyk et al. (2022) reported a decrease in swimming speed in adult swimmers after 3 months of DT [

44]. SC, SL, and SR are important parameters for determining swimming speed and achieving better times for a given distance [

45,

46,

47]. In this study, the SC20 and SC25 increased significantly by 1.4 SC and SL20 decreased significantly by 0.12 m between the two measurements. However, the SR20 remains constant around 35 cycles*min

-1. The data suggests that SR was the key factor affecting performance. Changes in SC and SL were significantly related to changes in swimming speed, resulted in a decrease in SP [

24]. The highest performance was achieved in the June measurement, where participants had a superior SC and SL. There appeared to be no difference in the pattern of SP between the typical and the population with ID [

24]. The SWOLF index demonstrated a statistically significant difference as it increased from a mean of 52.4 to 56.3 points. This indicates a loss of kinetics and physical adaptations from training. While there are very small differences in individual performance parameters, the effectiveness of swimming ability is declining [

48].

The relationship between an athlete’s mental and motor potential can be influenced by the level of brain development. Giagazoglou et al. (2012) suggest that inadequate brain development can restrict an athlete’s mental potential [

9]. Marques-Aleixo et al. (2013) found that people with ID may have poor strategic performance in swimming due to their limited cognitive abilities [

17]. The present study confirms the relationship between swimming speed parameters and performance, consistent with typical swimmers. A higher SC resulted in a prolonged time. Furthermore, better performance was correlated with longer SL, higher SR, and a lesser SWOLF index [

49].

The correlation analysis showed that both body weight and BMI were associated with a prolonged T25, as well as a decline in SWOLF and poor performance on both measures. In a typical population of swimmers, BMI does not seem to have an impact on performance ([

49,

50]. However, people with ID who have a high BMI are often described as having low levels of cardiorespiratory fitness [

16,

51] or poor motor skills [

52,

53].

4.4. Muscular Strength

Following detraining (DT), an observed increase in HGS from 215 N to 237 N was noted, though it did not reach statistical significance. This outcome aligns with the findings of Lemmer et al. (2000), which demonstrated that strength gains resulting from training are comparably retained across both young and older men and women during a 12-week period of detraining [

54]. Additionally, in both measurement periods, a correlation was identified between HGS and T25, consistent with prior research by Garrido et al. (2012) and Zampagni et al. (2006) [

55,

56].

4.5. Limitations

It is important to recognize the limitations of this study. The sample of participants included people with intellectual disability across a wide range of ages and levels of disability. In addition, a relatively small number of people with Down syndrome were included in the study. Stratifying participants by gender and disability status would result in small subgroup sizes, which would subsequently reduce the statistical power and robustness of the analysis.

5. Conclusions

The study revealed a statistically significant reduction in swimming performance following the summer break, with event times increasing by an average of 2.5 s from June to September. This decline was primarily attributed to reductions in SC, SL and the SWOLF index, which indicates compromised efficiency in swimming techniques. Athletes who exhibited an increase in SC exhibited longer completion times, reflecting diminished glide, flexibility, and reduced effectiveness in the pull and propulsion phases of the stroke cycle. This finding is consistent with the principle of reversibility, which states that previous training adaptations are lost in the absence of regular exercise. Furthermore, there was a positive correlation between grip strength and performance, which served to underscore the role of muscular strength in athletic outcomes. Additionally, the data indicated a slight increase in heart rate in September relative to June, which suggests a negative impact on cardiovascular fitness due to inactivity. People with ID were unable to reach optimal heart rate levels, which underscores additional barriers to performance. Physiological parameters, including weight and BMI, also increased during the de-training period, which potentially poses additional health risks for individuals with ID. These findings highlight the critical importance of consistent physical activity to maintain fitness levels and mitigate the decline in adaptations gained from prior training, particularly after competitive events, to support sustained health and athletic performance.

Perspectives

The effects of physical activity cessation in individuals with ID, particularly in relation to swimming, have been the subject of limited research. Swimming has been demonstrated to enhance the quality of life of people with ID, while also facilitating their participation in competitive activities and enabling them to achieve their full potential, thereby promoting socialization. In order to enhance the detection of parameter variations, it is recommended that the parameters in question be measured during the training period. Furthermore, future research could consider recruiting participants from a wider range of swimming styles and distances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.; methodology, G.K. and G.T.; software, G.K. and G.T.; validation, G.K.; G.T.; and C.E.; formal analysis, G.T.; investigation, G.K. and G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, G.K. and G.T.; writing—review and editing, G.T. and C.E.; supervision, C.E.; project administration, C.E.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Serres (ERC-010/2023, 02 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schalock, R.L.; Luckasson, R.; Tassé, M.J. An overview of intellectual disability: Definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of supports. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 2021, 126, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalock, R.L.; Borthwick-Duffy, S.A.; Bradley, V.J.; Buntinx, W.H.; Coulter, D.L.; Craig, E.M.; ...; Yeager, M.H. Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 444 North Capitol Street NW Suite 846, Washington 2010.

- Schalock, R.L.; Luckasson, R. A Systematic Approach to Subgroup Classification in Intellectual Disability. Intellect Dev Disabil 2015, 53, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC, 2013, pp. 31-86.

- Shapiro, B.K.; O’Neill, M.E. Developmental delay and intellectual disability. In: Kliegman RM, St Geme III JW, Blum NJ, et al. editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st edition. Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2020, pp. 283-293.

- Boer, P.H. Effects of detraining on anthropometry, aerobic capacity and functional ability in adults with Down syndrome. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 31 Suppl 1 2018, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vliet, P.; Rintala, P.; Fröjd, K.; Verellen, J.; van Houtte, S.; Daly, D.J.; Vanlandewijck, Y.C. Physical fitness profile of elite athletes with intellectual disability. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006, 16, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhall, B.; Pitetti, KH. Limitations to physical work capacity in individuals with mental retardation. Clin Exerc Physiol 2001, 3, 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Giagazoglou, P.; Arabatzi, F.; Dipla, K.; Liga, M.; Kellis, E. Effect of a hippotherapy intervention program on static balance and strength in adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Res Dev Disabil 2012, 33, 2265–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvat, M.; Pitetti, K.H.; Croce, R. Isokinetic torque, average power, and flexion/extension ratios in nondisabled adults and adults with mental retardation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther (JOSPT) 1997, 25, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, U.; Rintala, P.; Malin, A. Physical performance of individuals with intellectual disability: a 30 year follow-up. Adapt Phys Activ Q (APAQ) 2007, 24, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhall, B.; McCubbin, J.A.; Pitetti, K.H.; Rintala, P.; Rimmer, J.H.; Millar, A.L.; De Silva, A. Prediction of maximal heart rate in individuals with mental retardation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M.; Feys, H.; Daly, D. Benefits of swimming for children with cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Serb J Sports Sci 2013, 7, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, I.; Ergu, N.; Konukman, F.; Agbuğa, B.; Zorba, E.; Cimen, Z. The effects of water exercises and swimming on physical fitness of children with mental retardation. J Hum Kinet 2009, 21, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, A.F.; Rasmussen, R.; Mackenzie, S.J.; Glenn, J. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry to measure the influence of a 16-week community-based swim training program on body fat in children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010, 91, 1064–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhall, B.; Pitetti, K.H.; Vukovich, M.D.; Stubbs, N.; Hensen, T.; Winnick, J.P.; Short, F.X. Validation of cardiovascular fitness field tests in children with mental retardation. Am J Ment Retard 1998, 102, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques-Aleixo, I.; Querido, A.; Figueiredo, P.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Corredeira, R.; Daly, D.; Fernandes, R.J. Intracyclic velocity variation and arm coordination assessment in swimmers with Down syndrome. Adapt Phys Activ Q (APAQ) 2013, 30, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsson, I.P.; Johannsson, E.; Daly, D. Between and within race changes in race parameters in swimmers with intellectual disabilities. In: Aquatic Space Activities. Editors Nomura, T.; Ungerechts, B.E. 1st International Scientific Conference of Aquatic Space Activities. Publisher University of Tsukuba. Japan. 25-28/03/2008, pp. 153-158.

- Mujika, I.; Padilla, S. Detraining: loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part II: Long term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med (SMNZ) 2000b, 30, 145–154. [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, S.; Or, M. The detraining effects of complete inactivity. Thesis, Sport Science Faculty Yogyakarta State University 2005. Available at: https://staffnew.uny.ac.id/upload/132319845/penelitian/DETRAINING++EFFECTS+OF+COMPLETE+INACTIVITY.pdf (accessed on 30-05-2024).

- Lemmer, J.T.; Ivey, F.M.; Ryan, A.S.; Martel, G.F.; Hurlbut, D.E.; Metter, J.E.; Fozard, J.L.; Fleg, J.L.; Hurley, B.F. Effect of strength training on resting metabolic rate and physical activity: age and gender comparisons. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer P., H. The effect of 8 weeks of freestyle swim training on the functional fitness of adults with Down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res (JIDR) 2020, 64, 770–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, A.F.; Emes, C. The effects of swim training on respiratory aspects of speech production in adolescents with down syndrome. Adapt Phys Activ Q (APAQ) 2011, 28, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, D.; Einarsson, I.; Van de Vliet, P.; Vanlandewijck, Y. Freestyle race success in swimmers with intellectual disability. Portuguese J Sports Sci (PJSS) 2006, 6, 294–296. [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet, L.; Mujika, I. Detraining. In Endurance training: Science and Practice; Iñigo Mujika, S.L.U., Ed.; Iñigo Mujika: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2012, pp. 99–106.

- EAOM-AmeA. https://www.eaom-amea.gr.

- Papadimitriou, K.; Papadimitriou, N.; Gourgoulis, V.; Barkoukis, V.; Loupos, D. Assessment of Young Swimmers’ Technique with Tec Pa Tool. Cent Eur J Sport Sci Med (CEJSSM) 2021, 34, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, K.; Loupos, D. The Effect of an Alternative Swimming Learning Program on Skills, Technique, Performance, and Salivary Cortisol Concentration at Primary School Ages Novice Swimmers. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 9, 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Plaza, D.; Quero-Calero, C.D.; Alacid, F.; Abellán-Aynés, O. Stroke Steadiness as a Determinant Factor of Performance in 100 m Freestyle in Young Swimmers. Sports (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madou, T.; Vanluyten, K.; Martens, J.; Iserbyt, P. Assessment and Prediction of Swimming Performance Using the SWOLF Index. Int J Kin High Educ (IJKHE) 2021, 7, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perego, P.; Andreoni, G.; Sironi, R.; Lenzi, S.; Santambrogio, G. Wearable device for swim assessment: a new ecologic approach for communication and analysis. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Internet of Things 2015, 2, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludbrook, J. Should we use one-sided or two-sided P values in tests of significance? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2013, 40, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, C.B.; Jan, A. BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Treasure Island (FL) 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jacinto, M.; Monteiro, D.; Antunes, R.; Ferreira, J.P.; Matos, R.; Campos, M.J. Effects of exercise on body mass index and waist circumference of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1236379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, U.S.; Pillay, J.; Johnson, E.; Omoya, O.T.; Adedokun, A.P. A systematic review of physical activity: benefits and needs for maintenance of quality of life among adults with intellectual disability. Front Sports Act Living 2023, 5, 1184946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmi, T.; Nagi, L.F.; Iqbal, S.P.; Razzaq, S.; Hassnain, S.; Khan, S.; Shahid, N. Relationship Between Physical Inactivity and Obesity in the Urban Slums of Lahore. Cureus 2022, 14, e23719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwack, C.C.; McDonald, R.; Tursunalieva, A.; Lambert, G.W.; Lambert, E.A. Exploration of diet, physical activity, health knowledge and the cardiometabolic profile of young adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res (JIDR) 2022, 66, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Walpitage, D.L.; Mohseni, M.; Dreyer Gillette, M.L.; Davis, A.M.; Forseth, B.; Dean, E.E.; Waitman, L.R. Weight status and associated comorbidities in children and adults with Down syndrome, autism spectrum disorder and intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res (JIDR) 2020, 64, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; McCallion, P.; McCarron, M.; Luus, R.; Burke, E.A. Overweight/obesity and chronic health conditions in older people with intellectual disability in Ireland. J Intellect Disabil Res (JIDR) 2021, 65, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacca, R.; Toubekis, A.; Freitas, L.; Silva, A.F.; Azevedo, R.; Vilas-Boas, J.P.; Pyne, D.B.; Castro, F.A.S.; Fernandes, R.J. Effects of detraining in age-group swimmers performance, energetics and kinematics. J Sports Sci 2019, 37, 1490–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, E.F.; Martin, W.H.; Sinacore, D.R.; Joyner, M.J.; Hagberg, J.M.; Holloszy, J.O. Time course of loss of adaptations after stopping prolonged intense endurance training. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 1984, 57, 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, M.; Bricout, V.A. Low heart rate response of children with autism spectrum disorders in comparison to controls during physical exercise. Physiol Behavl 2015, 141, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, M.F.; Morais, J.E.; Marinho, D.A.; Silva, A.J.; Barbosa, T.M.; Costa, M.J. Growth influences biomechanical profile of talented swimmers during the summer break. Sports Biomech 2014, 13, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głyk, W.; Hołub, M.; Karpiński, J.; Rejdych, W.; Sadowski, W.; Trybus, A.; Baron, J.; Rydzik, Ł.; Ambroży, T.; Stanula, A. Effects of a 12-Week Detraining Period on Physical Capacity, Power and Speed in Elite Swimmers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barden, J.M.; Kell, R.T. Relationships between stroke parameters and critical swimming speed in a sprint interval training set. J Sports Sci 2009, 27, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellard, P.; Avalos, M.; Hausswirth, C.; Pyne, D.; Toussaint, J.F.; Mujika, I. Identifying Optimal Overload and Taper in Elite Swimmers over Time. J Sports Sci Med 2013, 12, 668–678. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalis, G.; Toubekis, A.G.; Michailidou, D.; Gourgoulis, V.; Douda, H.; Tokmakidis, S.P. Physiological responses and stroke-parameter changes during interval swimming in different age-group female swimmers. J Strength Cond Res 2012, 26, 3312–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, T.M.; Bragada, J.A.; Reis, V.M.; Marinho, D.A.; Carvalho, C.; Silva, A.J. Energetics and biomechanics as determining factors of swimming performance: updating the state of the art. J Sci Med Sport 2010, 13, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dopsaj, M.; Zuoziene, I.J.; Milić, R.; Cherepov, E.; Erlikh, V.; Masiulis, N.; di Nino, A.; Vodičar, J. Body Composition in International Sprint Swimmers: Are There Any Relations with Performance? Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, P.T.; Zisimatos, D. Relationship of body mass index with 1600 m running, 50 m swimming, and pull-ups performance in army cadets. Saudi J Sports Med 2014, 14, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitetti, K.H.; Yarmer, D.A.; Fernhall; B. Cardiovascular fitness and body composition of youth with and without mental retardation. Adapt Phys Activ Q (APAQ) 2001, 18, 127–141.

- Liu, T.; Kelly, J.; Davis, L.; Zamora, K. Nutrition, BMI and Motor Competence in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2019, 55, 135. [CrossRef]

- Sulton, K.; Jajat, J. Relationship between gross motor skills and body mass index of children with intellectual disability. In 3rd International Conference on Sport Science, Health, and Physical Education (ICSSHPE 25-26/09/2018). Advances in Health Sciences Research, Atlantis Press, 2019, 11, 210-213.

- Lemmer, J.T.; Hurlbut, D.E.; Martel, G.F.; Tracy, B.L.; Ivey, F.M.; Metter, E.J.; Fozard, J.L.; Fleg, J.L.; Hurley, B.F. Age and gender responses to strength training and detraining. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000, 32, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido, N.D.; Silva, A.J.; Fernandes, R.J.; Barbosa, T.M.; Costa, A.M.; Marinho, D.A.; Marques, M.C. High level swimming performance and its relation to non-specific parameters: a cross-sectional study on maximum handgrip isometric strength. Percept Mot Skills 2012, 114, 936–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampagni, M.L.; Casino, D.; Visani, A.; Martelli, S.; Benelli, P.; Marcacci, M.; De Vito, G. Influence of age and hand grip strength on freestyle performances in master swimmers. In ISBS-Conference Proceedings Archive. Salzburg – Austria, 14-18/07/ 2006).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).