1. Introduction

Paracycling is the third most prominent Paralympic sport, conducted under the parameters of the International Cycling Union (UCI) and the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) [

1]. The IPC and UCI oversee the functional classification and official competitions for male and female athletes with physical disabilities, visual impairments, and cerebral palsy [

2,

3].

This sport is performed in track races in a velodrome and road events on closed circuits. Track events include time trials, individual pursuits, and team sprints. Road events consist of mixed team relay races and time trials. In Paralympic sports, functional classification ensures that athletic achievement is determined by factors other than the impact of disability, fostering equity in competition [

4]. Functional classification in Paracycling assigns athletes to classes for bicycles (C1-C5), handcycles (H1-H5), tandems (B), and tricycles (T1-T2) [

5,

6].

In the T1-T2 sport class, athletes are diagnosed with cerebral palsy, including hypertonia, ataxia, and athetosis. They compete using a modified three-wheeled bicycle, with two rear wheels and one front wheel [

7]. This configuration enhances stability and helps prevent accidents during training and competitions due to the instability of paralympic athlete [

8]. Tricycle events range from 15 km to 20 km in individual time trials and from 30 km to 40 km in road races [

3].

In Paracycling, energy demands during events are primarily met by the oxidative pathway throughout most of the race, with a significant contribution from the glycolytic pathway during inclines and at the end of the race with a sprint [

9,

10]. This sport requires high lower-limb muscular power output to complete road and time trial races in the shortest possible time [

11]. Thus, monitoring and controlling these variables is essential to meet the physiological and neuromuscular demands of competition [

12].

Given this, coaches aim to enhance paralympic athlete performance throughout the season, emphasizing sport and athlete characterization, physiological load monitoring, intensity and volume control, physical fitness evaluation, and competition performance assessment. These factors are vital in Paralympic sports due to the population’s variability and heterogeneity [

1].

Performance in Paracycling largely depends on aerobic and anaerobic power produced during competition. These capacities should be trained using methods that ensure optimal physiological and competitive adaptations [

13,

14]. High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) has proven to be an efficient and applicable method for athletes with physical or visual disabilities or cerebral palsy [

15].

Numerous studies in wheelchair basketball [

16,

17], wheelchair rugby [

18], cerebral palsy football [

19], paratriathlon [

20], Paracycling [

12,

21] and ParaAthletics [

22] have reported changes in maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max), upper and lower body muscular power, body composition, and athletic performance in Paralympic athletes [

15].

HIIT consists of performing repeated bouts of high-intensity efforts, typically above 85% of Maximum Oxygen Uptake (VO2max), interspersed with active or passive recovery periods at low intensity [

22,

23]. In this endurance training method, the workload is characterized by low training volume and high intensity (above 85% VO2max) during the athletic season [

24]. This feature of HIIT is generally used to improve cardiorespiratory function and the energy reserves of oxidative and glycolytic metabolism, which translates into performance improvements in time-trial sports by delaying the onset of fatigue [

25].

To achieve the desired central and peripheral physiological adaptations, the dosing of HIIT workload is influenced by the stage of the season and the type of HIIT applied (short HIIT or long HIIT). Long HIIT intensities range from 2 to 6 minutes (85–100% VO2max), focusing primarily on the oxidative pathway. In contrast, short HIIT, which predominantly involves the glycolytic pathway, ranges from 10 to 60 seconds (100–115% VO2max), alternating with recovery intervals at 50–60% VO2max [

25].

Previous research on Paralympic sports performance has highlighted the need for more specific studies on elite athletes with disabilities. A literature review on the use of HIIT reported studies on Paracycling in the cycling and handcycling sport classes, but no studies were found for tricycles [

15].

However, to date, these studies have primarily focused on measuring performance in controlled environments, improving mobility, and rehabilitation to avoid exacerbating athletes' limitations [

26]. Therefore, this study aims to analyze the effects on VO2max, anaerobic power, and athletic performance of cyclists with cerebral palsy after four weeks of HIIT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This quasi-experimental, longitudinal analytical study was conducted with paralympic athlete from the Departmental Paracycling Commission of Cauca, Colombia. The dependent variables were aerobic power, anaerobic power, and specific performance. The independent variable was the four-week HIIT training program.

2.2. Subjects

The study involved three male paralympic athlete classified in the T1 sport class (n=2; age: 21.5±3.53 years; height: 158.5±3.53 cm; body mass: 53.1±2.40 kg; competitive experience: 4.5±3.53 years) and the T2 sport class (n=1; age: 56 years; height: 171 cm; body mass: 72.4 kg; competitive experience: 4.5±3.53 years). They actively participate in regional and national competitions (Qualification Games and National Paralympic Games), with weekly training frequency ranging from 3 to 7 sessions.

The sample was non-probabilistic and intentional, with exclusion criteria including musculoskeletal injuries or inability to complete the study. Participants signed informed consent forms before starting the study. They were informed about the research objectives, procedures, risks, and benefits and could withdraw from the experiment at any time.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Vice-Rectory for Research at the University of Cauca and the Autonomous University Corporation of Cauca through Resolutions No. 011 of 2023 and No. 0221 of 2024, respectively. Ethical guidelines were followed according to the Declaration of Helsinki, Resolution 8430 of 1993 by the Ministry of Health, and Colombia's Data Protection Law 1581 of 2012.

2.3. Procedure

The study was conducted over a six-week period. The first week was used for preintervention evaluations; from the second to the fifth week, the HIIT training was implemented, and the sixth week was dedicated to final evaluations.

2.4. Reference Tests

Measurements were taken before and after the four-week intervention during the first and last weeks of the study under the same conditions of place and time. Tests were conducted on three separate days with a 48-hour interval between tests to avoid fatigue. Participants followed their usual diet, ensured proper hydration, refrained from high-intensity activities 48 hours before the test, and abstained from consuming caffeine, supplements, and stimulants on test mornings.

Before starting protocols (initial and final tests) and training (during the intervention) on the Cyclus 2 bicycle ergometer (Avantronic, Cyclus 2, Leipzig, Germany). Paralympic athlete performed a standardized 10-minute warm-up at a self-selected cadence of 60 revolutions per minute (rpm) with a load of 60 W. Cool-down consisted of 5 minutes at 50 W and a cadence of 60 rpm.

2.5. Body Composition

Paralympic athlete ensured proper fluid voiding to minimize measurement errors from bioelectrical impedance. Height was recorded with a mechanical measuring tape (Seca 206, Germany). Body composition was assessed using bioelectrical impedance (OMRON Healthcare Technology, HBF-514C scale, Japan). The device sends a light electrical current (50 kHz) through the body via electrodes. Participants stood upright, wearing minimal clothing and no shoes, with feet on the platform electrodes and hands gripping the designated handles, extending arms forward at chest height.

2.6. VO2max

VO2max was indirectly measured using a graded, incremental test, where athletes were required to sustain increasing workloads over time. The test respected the principle of individuality, with specific adjustments for each athlete. For T1 athletes, the initial workload was set at 70 W, with increments of 15 W every 2 minutes at a cadence of 60 rpm until exhaustion. For the T2 athlete, the initial workload was 100 W, increasing by 25 W every 2 minutes at a cadence of 80 rpm until exhaustion [

12,

27].

The test concluded when participants could no longer maintain the workload or cadence. In this test, heart rate (HR) was monitored each time the athletes progressed to a higher stage, as well as their maximum HR.The device used was a Polar H10 chest strap sensor (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland) linked to the Cyclus 2. Finally, to determine indirect VO2max (ml·kg⁻¹·min⁻¹), the following equation, used in previous studies [

28], was applied:

VO2máx = (10.51 x Wmáx.) + (6.35 x Weight (kg)) - (10.49 x Age (years)) + 519.3.

2.7. Wingate Test

The measurement of anaerobic power was conducted using a Cyclus 2 bicycle ergometer. The test required the athlete to pedal against a resistance of 0.075 kg per kilogram of body mass at maximum speed for 30 seconds to determine the peak power output in watts [

29]. Participants were instructed to reach their maximum power in the shortest time possible, maintain maximum power until the end of the test, and were provided with auditory stimuli to encourage maximum effort [

30].

The workload for T1 class athletes was set at an initial cadence of 70 rpm, while for T2 class athletes, the starting cadence was 90 rpm. The protocol began with a starting signal, where athletes were positioned standing on the pedals, with their dominant leg ready for the initial push. Athletes performed three alternating attempts, with 30 minutes of recovery between each attempt, and the best result was recorded.

2.8. Specific Performance

The performance test was conducted on a closed 1 km circuit. Athletes performed a standardized 20-minute warm-up on the track at a comfortable pace, allowing them to familiarize themselves with the circuit. Timing was recorded using Witty·Gate photocells (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy) with a precision of ±0.4 milliseconds, positioned 40 cm above the ground and spanning a length of 2 meters. For this test, paralympic athlete were instructed to cover the assigned distance in the shortest possible time. A 14 km time trial was conducted for T1 class athletes and a 20 km time trial for T2 class athletes. Both sport classes performed the test simultaneously to simulate a competitive race and were encouraged by the coach and researchers.

2.9. Training Program

The periodization, dosage, and monitoring of the training load were conducted in collaboration with the athletes’ coach. Additionally, guidance and recommendations on volume, intensity, and exercises applied using the HIIT method were provided by a national coach with international experience (bronze medalist in the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games with a T2 class athlete in a road race).

The classic periodization model by Matveev [

31] was used, distributed into three microcycles, with a training frequency of two sessions per week, each lasting 50 minutes. The study was implemented during the special preparation phase before the 2023 National Para Games in Colombia.

The participants performed all HIIT training sessions using a bicycle ergometer. Based on the aerobic and anaerobic power tests, four power training zones in Watts (W) were established to guide the intervention: Zone 1 (40–65%), Zone 2 (70–80%), Zone 3 (85–100%), and Zone 4 (105–120%). Additionally, five heart rate (HR) training zones were defined based on the maximum HR recorded during the incremental protocol: Zone 1 (50–60%), Zone 2 (60–70%), Zone 3 (70–80%), Zone 4 (80–90%), and Zone 5 (90–100%) [

5].

Table 1 presents the volume and intensity of the HIIT sessions during the intervention. During training sessions, heart rate was continuously monitored, and athletes were asked to provide their rate of perceived exertion (RPE) using a modified Borg scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates minimal intensity and 10 very intense [

32,

33]. This scale was familiarized with the athletes before the study.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Software (

Version 24.0, licensed by the Autonomous University Corporation of Cauca). Descriptive statistics were applied using measures of central tendency, and the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for paired samples was used to determine significant differences in the analyzed variables, considering that the subjects could not be normally distributed [

27]. The percentage of change was calculated as (

Δ = [postest – pretest / pretest] * 100) [

19].

The effect size (ES) was calculated using Hedges’g test [

34] for VO2max and anaerobic power variables only. Specific performance in the time trial events was not included due to the disparity in distances for each sport class. The interpretation of effect size values was as follows: < 0.24 (trivial), 0.25–0.49 (small), 0.5–0.99 (moderate), or > 1.00 (large) [

34]. Statistical significance was established at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

The body composition characteristics of the participants are shown in

Table 2. However, these variables presented minimal percentage changes (< 0.2, trivial). Body weight and BMI decreased by 0.3%, muscle mass increased by only 0.2%, and body fat showed a difference of 1.3% in the post-test. Height did not show any changes.

The VO2max and anaerobic power results for both the pre-test and post-test are presented in

Table 3. Regarding VO2max from the incremental test, percentage changes were greater for the T2 class (9.4%) compared to the T1 class (8.2%). Overall, there was a 7.7% improvement (d = 0.02, trivial) in the post-test. The maximum watts (Wmax) in the Wingate test after the HIIT program were 16.6% higher (d = 0.52, moderate) than in the pre-test. For T1 and T2 sport classes, these changes were 21.1% and 9.0%, respectively. Mean power improved by 16.2% (d = 0.58, moderate), the fatigue index by 30.4% (d = 0.04, trivial), anaerobic power by 16.2% (d = 0.13, trivial), and anaerobic capacity by 13.4% (d = 0.06, trivial). Positive numerical and percentage changes were observed in all the analyzed variables in the post-test.

Table 4 presents the values for the sports performance variable after the HIIT training program. These data are expressed in seconds for the individual time trial races. Overall, a reduction in time is observed for the 14 km time trial (2489 vs. 2338.25 seconds, Δ = 6.05%) and the 20 km time trial (2775 vs. 2674 seconds, Δ = 3.6%) for the T1 and T2 sport classes, respectively.

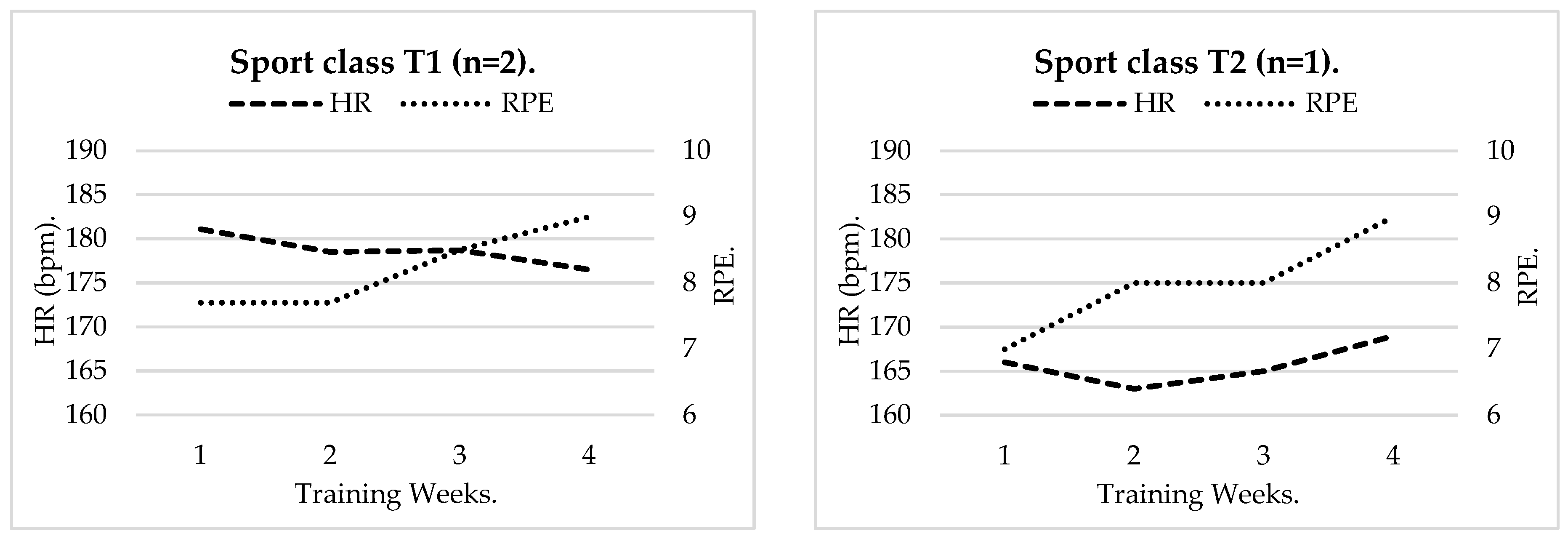

The physiological response of the cardiovascular system, monitored through heart rate (HR), and the perceptual response measured by RPE in Paracycling athletes after undergoing an HIIT training program during 8 sessions over four weeks, is presented. Graph 1 illustrates the behavior of these variables for each sport class.

For T1 sport class athletes, the HR curve showed a downward trend until the fourth week. Similarly, the RPE curve maintained steady levels during the first two weeks but increased during the third and fourth weeks due to the higher intensity of short HIIT sessions. Overall, HR fluctuated above 175 bpm, and RPE remained above 8/10 throughout the study. For the T2 class athlete, HR exceeded 165 bpm during weeks 1, 3, and 4, while RPE increased progressively during the study, reaching a maximum perceptual response of 9/10.

Figure 1.

Heart Rate (HR) and Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Response During 4 Weeks of HIIT in Paracycling Athletes.

Figure 1.

Heart Rate (HR) and Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Response During 4 Weeks of HIIT in Paracycling Athletes.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this research was to analyze the effects on VO2max, anaerobic power, and athletic performance in cyclists with cerebral palsy after four weeks of HIIT. On one hand, percentage changes were observed with an increase in VO2max, in peak power output (in the 30-second test and the incremental test), and in time trial performance. However, no significant differences were detected in the studied variables from pre-test to post-test. This improvement was reflected in shorter times for the 14 km individual time trial for the T1 class and the 20 km time trial for the T2 class.

To our knowledge, this is the first study conducted with Paracycling athletes in the T1 and T2 sport classes [

15]. The results of the current study show that active participation in Paracycling training programs is predominantly male, findings consistent with those reported by Kim et al. [

12], who included a similar sample.

The body weight of the participants was lower compared to the study by Nevin et al. [

10] which included physically disabled athletes (69.4 ± 15.4 kg) who underwent an 8-week handcycling training program. The age, weight, and height of the current study differ from findings in previous research [

35]. BMI at the end of the HIIT training showed no changes, as reported by Burkett & Mellifint [

35] in Paralympic cycling athletes.

The muscle tissue observed in this study was higher compared to previous research [

7]. Anaerobic power improved after the intervention, with T1 athletes showing lower W values, while the T2 athlete exhibited higher values. These results are consistent with the reduced recruitment of muscle fibers for contraction and the limited contribution of phosphagen and glycolytic metabolism in T1 athletes due to the severity of their disability compared to T2 athletes.

The results of this research show moderate improvements in anaerobic power, specifically in maximal power peak (342.7 vs. 399.7 W, Δ: 16.6; p=0.109, d=0.52, moderate) and mean power (277.7 vs. 336.7 W, Δ: 21.2; p=0.109, d=0.58, moderate). These findings indicate that the HIIT training program was effective in improving anaerobic power in T1 and T2 class athletes.

Anaerobic power in the study by Furno Puglia et al. [

30], involving international handcycling athletes ranged from 223.9 to 571.7 W, aligning with the W values reported in this study (277.4 to 516.2 W). However, these results are also comparable to those found in football players with cerebral palsy, who achieved a maximum power output of 490.6 ± 125.7 W [

36].

It is noteworthy that these data surpass those of T1 class athletes, but the W generated by the T2 athlete were higher (516.2 W). In contrast, trained cyclists completed the same test with a power output of 799.2 ± 267.0 W [

37]. In the study by Yanci et al. [

36], mean power, fatigue index, and anaerobic power were superior, as evidenced by higher W values mobilized within the first 6 seconds of the test, where the mean W mobilized remained close to the maximum W achieved.

In this context, better performance was observed in the Wingate test, which is of short duration, compared to the incremental protocol, which is a prolonged test. These positive numerical and percentage changes in aerobic endurance and maximum W can be explained by the fact that the athletes followed both long HIIT and short HIIT training programs on the bicycle ergometer during the study.

According to our findings, Kim et al. [

12], observed a decrease in VO2max in 2 out of 3 athletes studied over the same period while using hypobaric hypoxia training at an altitude of 4,000 m. Similar results were reported by Koontz et al. [

21] and Russo et al. [

38], where no significant changes (p > 0.05) in VO2max were observed after a HIIT program in handcycling.

Additionally, Russo et al. [

38], in an incremental test with 5 handcycling athletes, found W values similar to those mobilized by the athletes in the current study, but lower than those of non-disabled cyclists who participated in the same experiment. From previous studies [

4,

9], heart rate (HR) response was higher during W production in the incremental test, where positive changes were observed in T1 and T2 class athletes.

Regarding sports performance variables, there was a reduction in the time required to complete the individual time trials of 14 km and 20 km for T1 and T2 classes, respectively. T1 class athletes improved their individual performance in the 14 km time trial, which is directly related to the findings reported by Kim et al [

12], who applied the same test with physically disabled athletes at an altitude of 4,000 m above sea level.

In contrast to the present study, Boer & Terblanche [

39] and Flueck [

7], observed lower time values (2220 seconds) for completing a 20 km time trial in T2 class athletes. These differences could be explained by factors such as variations in the age of the sample, differences in body composition, with athletes presenting a lower proportion of fat tissue and a higher proportion of lean muscle tissue. Additionally, these factors influence the workload dosing and training program design.

The data collected on the physiological response through heart rate (HR) and the subjective response via RPE during the 8 training sessions provided a means to control and optimize the effects induced by the workload. This allowed for monitoring and acting on states of overload, overtraining, and the prevention of potential injuries in Paracycling athletes [

26].

However, this study presents certain limitations. The small sample size, the absence of female athletes, and the lack of control groups are significant constraints. Given the heterogeneity among athletes, sport classes, and types of disabilities, the findings may vary. These challenges stem from the difficulty and complexity of accessing the population due to territorial dispersion and their specific characteristics. Future studies should consider working with athletes residing in institutional settings to better control the variables under investigation.

Another limitation is that, as a non-controlled quasi-experimental study, biochemical and physiological markers were not measured using direct methods [

40]. Future studies should incorporate these techniques. Additionally, training programs should prioritize and implement strength, flexibility, and road work exercises to better assimilate the training loads applied in laboratory settings.

Lastly, longer intervention studies are needed to confirm the findings over the medium and long term. In this study, one of the limitations preventing the research from extending beyond four weeks with the HIIT method was the cyclists' national competition schedule. Nevertheless, this experiment is highlighted for its novelty as it opens the door to more exhaustive, controlled, and rigorous future research.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reported that HIIT positively influenced VO2max, moderate improvements in anaerobic power output, and athletic performance in T1-T2 class athletes over a short period of four weeks. These changes were reflected in reduced time trial durations for 14 km and 20 km races for each sport class. While this is the first study conducted with T1 and T2 class athletes, it is recommended that future research include additional measurement protocols to thoroughly analyze the effects on body composition, physical fitness, and sports performance over the medium and long term. This will help identify the optimal training approach for Paracycling athletes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.L.Q. and L.M.C.N.; methodology, C.A.L.Q., L.M.C.N., D.C.G.C., C.C.M. and R.A.Y.S.; validation, C.A.L.Q., L.M.C.N., D.C.G.C., C.C.M. and R.A.Y.S.; formal analysis, C.A.L.Q., L.M.C.N., D.C.G.C., C.C.M. and R.A.Y.S.; investigation, C.A.L.Q. and L.M.C.N.; resources, C.A.L.Q. and L.M.C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.L.Q., L.M.C.N. and D.C.G.C.; writing—review and editing, C.A.L.Q., L.M.C.N., D.C.G.C., C.C.M. and R.A.Y.S.; visualization, C.A.L.Q., L.M.C.N., D.C.G.C., C.C.M. and R.A.Y.S.; supervision, C.A.L.Q.; project administration, C.A.L.Q.; funding acquisition, C.A.L.Q. and L.M.C.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Cauca and the Corporacion Universitaria Autonoma del Cauca under the Young Researchers and Innovators of the Department of Cauca 2023-2024 Project, identified under BPIN 2020000100043 and DNI 5645.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Resolution 8430 of 1993 by the Ministry of Health, and Colombia's Data Protection Law 1581 of 2012, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Vice-Rectory for Research at the University of Cauca and the Corporacion Universitaria Autonoma del Cauca through Resolutions No. 011 of 2023 and No. 0221 of 2024, respectively.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Physiology Laboratory of the Autonomous University Corporation of Cauca, the University of Cauca, Comfacauca, the Young Researchers and Innovators Project in the Department of Cauca and the Departmental Commission of Paracycling of Cauca for their support in carrying out this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cavedon V, Rosponi A, Alviti F, et al. Comparison between the 10- and the 30-s-long Wingate Anaerobic Test in summer Paralympic athletes with a lower limb impairment. Sport Sci Health. 2021;17(1):79-90. [CrossRef]

- International Paralympic Committee. IPC Athlete Classification Code.; 2015. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://bit.ly/3JL8urD.

- Union Cycliste Internationale. UCI REGULATIONS PART 16 PARA-CYCLING.; 2023. Accessed October 28, 2023. https://archive.uci.org/docs/default-source/rules-and-regulations/part-xvi--para-cycling.pdf?sfvrsn=47af1c56_34.

- Muchaxo R, De Groot S, Kouwijzer I, Van Der Woude L, Janssen T, Nooijen CFJ. A Role for Trunk Function in Elite Recumbent Handcycling Performance? J Sports Sci. 2021;39(20):2312-2321. [CrossRef]

- Zeller S, Abel T, Strueder HK. Monitoring Training Load in Handcycling: A Case Study. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(11):3094-3100. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Galíndez E, Lasso-Quilindo CA, Pérez-Muñoz S. Adapted cycling: a beacon of light to heal physical and psychological wounds. Colombian Journal of Sociology. 2022;45(2):349-372. [CrossRef]

- Flueck JL. Nutritional Considerations for Para-Cycling Athletes: A Narrative Review. Sports. 2021;9(11):154. [CrossRef]

- Villa del Bosque G, González-Devesa D, Villa-Vicente JG, García-Fresneda A, Suárez-Iglesias D, Ayán-Pérez C. Exploring research on competitive Para-cyclists and its related factors: A scoping review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. Published online June 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kouwijzer I, Valent L, Osterthun R, van der Woude L, de Groot S. Peak power output in handcycling of individuals with a chronic spinal cord injury: predictive modeling, validation and reference values. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(3):400-409. [CrossRef]

- Nevin J, Smith P, Waldron M, et al. Efficacy of an 8-Week Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training program on Hand Cycling Performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(7):1861-1868. [CrossRef]

- Stone B, Mason BS, Stephenson BT, Goosey-Tolfrey VL. Physiological responses during simulated 16 km recumbent handcycling time trial and determinants of performance in trained handcyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2020;120(7):1621-1628. [CrossRef]

- Kim SH, An HJ, Choi JH, Kim YY. Effects of 2-week intermittent training in hypobaric hypoxia on the aerobic energy metabolism and performance of cycling athletes with disabilities. J Phys Ther Sci. 2017;29(6):1116-1120. [CrossRef]

- Muchaxo R, De Groot S, Kouwijzer I, van der Woude LH V., Nooijen CFJ, Janssen TWJ. Association between upper-limb isometric strength and handcycling performance in elite athletes. Sports Biomech. Published online June 20, 2022:1-20. [CrossRef]

- Kouwijzer I, Valent LJM, van Bennekom CAM, Post MWM, van der Woude LH V., de Groot S. Training for the HandbikeBattle: an explorative analysis of training load and handcycling physical capacity in recreationally active wheelchair users. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(12):2723-2732. [CrossRef]

- Lasso-Quilindo CA, Chalapud-Narváez LM. High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) in Paralympic Athletes. A narrative review. Retos. 2024;51:1431-1441. [CrossRef]

- Iturricastillo A, Granados C, Yanci J. Changes in Body Composition and Physical Performance in Wheelchair Basketball Players During a Competitive Season. J Hum Kinet. 2015;48(1):157-165. [CrossRef]

- Iturricastillo A, Yanci J, Granados C. Neuromuscular Responses and Physiological Changes During Small-Sided Games in Wheelchair Basketball. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2018;35(1):20-35. [CrossRef]

- Briley SJ, O’Brien TJ, Oh Y, et al. Wheelchair rugby players maintain sprint performance but alter propulsion biomechanics after simulated match play. Scand J Med Sci Sports. Published online June 6, 2023:1-12. [CrossRef]

- Peña-González I, Moya-Ramón M. Physical performance preparation for the cerebral palsy football world cup: A team study. Apunts Sports Medicine. 2023;58(218):100413. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson BT, Shill A, Lenton J, Goosey-Tolfrey V. Physiological Correlates to In-race Paratriathlon Cycling Performance. Int J Sports Med. 2020;41(08):539-544. [CrossRef]

- Koontz AM, Garfunkel CE, Crytzer TM, Anthony SJ, Nindl BC. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a handcycling high-intensity interval training program for individuals with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2021;59(1):34-43. [CrossRef]

- Lasso-Quilindo CA, Chalapud-Narváez LM, Medina-López JE, García-Mantilla ED. Effects of HIIT on Physical Condition and Sports Performance in 800 and 1500 m Middle Distance Runners of Para Athletics: A Case Study. Retos. 2024;56:707-717. [CrossRef]

- Sanabria Navarro JR, Cardozo Pacheco LÁ, Cortina Núñez MDJ. Effects of HIIT vs. Traditional Functional Training in a Group of Workers at Risk of Metabolic Syndrome and Cardiovascular Disease in the District of Cartagena, Colombia. Retos. 2024;51:551-558. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit M, Laursen P. High-Intensity Interval Training, Solutions to the Programming Puzzle: Part I: Cardiopulmonary Emphasis. Sports Medicine. 2013;43(5):313-338. [CrossRef]

- Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-Intensity Interval Training, Solutions to the Programming Puzzle: Part II: Anaerobic Energy, Neuromuscular Load and Practical Applications. Sports Medicine. 2013;43(10):927-954. [CrossRef]

- Stieler E, de Mello MT, Lôbo ILB, et al. Current Technologies and Practices to Assess External Training Load in Paralympic Sport: A Systematic Review. J Sport Rehabil. 2023;32(6):635-644. [CrossRef]

- Park HY, Jung WS, Kim J, et al. Effects of 2-Week Exercise Training in Hypobaric Hypoxic Conditions on Exercise Performance and Immune Function in Korean National Cycling Athletes with Disabilities: A Case Report. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3):861. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Parraci CA, Gomez-Mazorra M. Assessment of physical condition and prescription of physical exercise. University of Tolima Publishing House Imprint; 2018. https://elibro.net/es/lc/unicauca/titulos/228360.

- Takeda R, Nojima H, Nishikawa T, Okudaira M, Hirono T, Watanabe K. Subtetanic neuromuscular electrical stimulation can maintain Wingate test performance but augment blood lactate accumulation. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2023;124(2):433-444. [CrossRef]

- Furno-Puglia V, Paquette M, Bergdahl A. Characterization of muscle oxygenation response in well-trained handcyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol. Published online June 10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- García-Manzo JM, Navarro-Valdivielso M, Ruiz-Caballero JA. Planificación Del Entrenamiento Deportivo. Gymnos Editorial; 1995.

- Bellinger P, Arnold B, Minahan C. Quantifying the Training-Intensity Distribution in Middle-Distance Runners: The Influence of Different Methods of Training-Intensity Quantification. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020;15(3):319-323. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes A, Gomes de Souza Vale R, Ferreira Costa Leite CD, et al. Effects of different recovery times during high-intensity interval training using body weight on psychophysiological variables. Retos. 2024;51:109-116. [CrossRef]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1998.

- Burkett BJ, Mellifont RB. Sport Science and Coaching in Paralympic Cycling. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2008;3(1):95-103. [CrossRef]

- Yanci J, Castagna C, Los Arcos A, et al. Muscle strength and anaerobic performance in football players with cerebral palsy. Disabil Health J. 2016;9(2):313-319. [CrossRef]

- Devereux G, Le Winton HG, Black J, Beato M. Effect of a high-intensity short-duration cycling elevation training mask on VO2max and anaerobic power. A randomized controlled trial. Biol Sport. 2022;39(1):181-187. [CrossRef]

- Russo A, Invernizzi PL, Scurati R, Ceruso R, Altavilla G. Removing the division into categories between cycling and para-cycling (Handbike category H) by designing a single performance and training activity. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise. 2021;16(Proc2):716-725. [CrossRef]

- Boer PH, Terblanche E. Relationship between maximal exercise parameters and individual time trial performance in elite cyclists with physical disabilities. South African Journal for Research in Sport, Physical Education and Recreation. 2014;36(1):1-10.

- Bermejo F, Olcina G, Martínez I, Timón R. Effects of a HIIT protocol with functional exercises on performance and body composition. Arch of Sports Med. 2018;35(6):386-391. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://archivosdemedicinadeldeporte.com/articulos/upload/or05_bermejo.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).