1. Introduction

Orthodontic bracket bond strength is determined by the type of adhesive system used and the quality of treated enamel and bracket base surfaces. Studies have demonstrated that the conventional etch-and-rinse method using phosphoric acid continues to be the method of choice for enamel conditioning prior to bracket bonding since it ensures the durability of the bracket attachment to enamel. An orthodontic adhesive needs to provide a high shear bond strength (SBS) to withstand masticatory stresses and forces exerted by orthodontic wires. Unfortunately, this entails a greater debonding force to remove the brackets following orthodontic treatment, which results in iatrogenic enamel fracture, chipping or cracking and leaves larger adhesive residues [

1,

2,

3].

Recent research in orthodontics has been directed towards reducing enamel damage and shortening chair-side treatment times in order to expedite intraoral application [

4,

5]. Self-adhesive resins (SARs) can eliminate the need for separately applying primers after enamel conditioning via combining the priming and adhesive ingredients into a single application. These materials are desired because they achieve clinically successful bond strengths while cutting down on working time and saliva contamination risks during the treatment process [

6,

7]. However, SARs may have drawbacks in terms of the higher microbial adhesion levels, insufficient micromechanical retention between the adhesive and the tooth surface, and greater microleakage than conventional adhesives. Consequently, may be associated with white spot lesions and\or plaque retention around bracket margins [

8].

Nowadays, the clinical application of bioactive glass (BAG) materials in various fields of dentistry has been widespread, such as their use to enhance enamel remineralization and combat white spot lesion development [

9]. Among these, the 45S5 BAGs possess a broad range of effective applications since they have the ability to dissolve in bodily fluids, forming a silica-rich layer that is then covered with a bioactive hydroxyapatite-rich layer and can adhere to both hard and soft biological tissues [

10,

11]. In addition, it has been reported that BAGs with strontium substitution are superior biomaterials to plain 45S5 BAG as strontium provides an anticariogenic effect and may function synergistically with fluoride [

12]. Moreover, natural products such as grape seeds have recently been increasingly used in restorative dental work and prevention of dental caries via its proanthocyanidin group that is responsible for grape seeds positive effects on dental diseases [

13].

Therefore, this study aimed to develop a novel (SAR) for orthodontic bracket bonding that can leave minimal remnant adhesive and enamel damage upon bracket debonding, while maintaining adequate SBS for clinical performance. The study rationale was premised on chemically inducing surface changes onto the enamel to enhance its resistance to damage via incorporation of strontium fluoride, grape seed extract (GSE) and BAG into an orthodontic SAR without adversely affecting the SBS. The null hypothesis stated that the newly developed and plain SARs would demonstrate a similar behaviour in terms of shear bond strength, micro-hardness, enamel damage and amount of residual adhesive post bracket debonding.

2. Materials and Methods

The study involved three phases (

Figure 1):

2.1. Phase I: Preparation of Tooth Sample, Modified Orthodontic SARs and SBS Measurements

2.1.1. Preparation of Tooth Samples and Modified Orthodontic SARs

Eighty human premolars extracted from patients for orthodontic purposes were collected to be used in orthodontic bonding procedures. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the College of Dentistry, University of Baghdad (Ref. number 620\620422). According to ISO/TS 11405:2015, the teeth were cleansed under running water after extraction, immersed in a 1% chloramine-T trihydrate bacteriostatic/bactericidal solution for a week, and then kept in distilled water until bonding time. Upon examination under a stereomicroscope (10X magnification, Optico ASZ-400B Stereo Zoom Microscope, Australia), the selected teeth showed intact buccal enamel surface, no carious lesions, and no enamel cracks or abnormalities. The teeth were set in acrylic blocks using a custom-made rubber mould and a standardized procedure (Ibrahim et al., 2020). Prior to the bonding process, the mounted premolars were kept in distilled water at 20–23°C and 50–60% humidity at a laboratory setting.

Following an initial phase of rigorous pilot experiments on developing 10 modified SARs, only three formulations performed successfully; hence proceeded to the current phase of study. The plain orthodontic SAR (Heliosit Orthodontic, Ivoclar-Vivadent, Germany) was used as control (composition: highly dispersed silica dioxide (as filler) 14% wt; monomer matrix of urethane dimethacrylate, Bis-GMA and decandiol dimethacrylate 85%wt; catalysts and stabilizers 1% wt). Three modified SARs were prepared in a weight-to-weight ratio by mixing 1% of commercially available BAG 45S5 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 0.5% of strontium fluoride (anhydrous, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 0.5% powdered GSE (high strength 95% proanthocyanidins, One Planet Nutrition, USA) with the plain SAR.

A four-digit sensitive balance (ADAM\ADAM Equipment, UK) was used to confirm the exact weight of the experimental materials. The weighed amount of each experimental material was added to a glass vial containing a plain SAR in the following ratios: BAG 45S5 0.01:1 and 0.03:1; strontium fluoride 0.005:1 and 0.01:1; and powdered GSE 0.005:1 and 0.01:1 during the mixing procedure, which was carried out under UV light protection. A customized plastic bur installed on a straight handpiece of an electric micro-motor dentistry machine was used to mix the material inside the glass container for three minutes until a uniform mixture was achieved. For orthodontic bonding, one type of metal (stainless steel) pre-adjusted upper premolar brackets (Roth, slot 0.022x0.028-inch, DB Orthodontics, UK) was used for orthodontic bonding. 37% phosphoric acid gel (Ultradent, USA) was applied onto the whole buccal surface of each tooth for 30 s, followed by 10 s rinsing and 10 s dryness [

14]. The control and modified SARs were utilized for bracket bonding, a thin layer was placed on each bracket base, and a force gauge (Digital Force Gauge, China) was used to press the bracket onto the buccal surface for three seconds applying a force of 300 g [

5]. Ultimately, in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, the attached brackets were exposed to an LED curing light (Woodpecker iLED Max Curing Light, China; 2300–2500 mw/cm2 light intensity) that was set on turbo mode for 12 s (6 s on each mesial and distal side). The bonded premolars were stored in distilled water at 37°C for 24 h, then divided into three groups according to the following artificial ageing protocols:

2.1.2. SBS and Adhesive Remnant Index (ARI) Assessment:

A chisel attached to an Instron (Tinius - Olsen universal testing machine, model H50KT, England) was used to perform the SBS debonding test. The chisel was vertically positioned at the enamel-bracket base interface, parallel to the bonded surface. The bracket was subjected to an occluso-gingival strain at a cross-head speed of 0.5 mm/min until it debonded [

4]. The resultant SBS (in MPa) was equal to the load at bracket failure (measured in Newton) divided by the bracket base surface area (provided by DB Orthodontics Company). The debonded premolars were coded and randomly examined under a stereomicroscope with 10× magnification to assess the amount of adhesive left on the enamel surface following debonding according to the following scoring system [

15]: score 0 = no adhesive left on the tooth; score 1 = less than half of the adhesive left on the tooth; score 2 = more than half of the adhesive left on the tooth; and score 3 = all adhesive left on the tooth, with distinct impression of the bracket mesh.

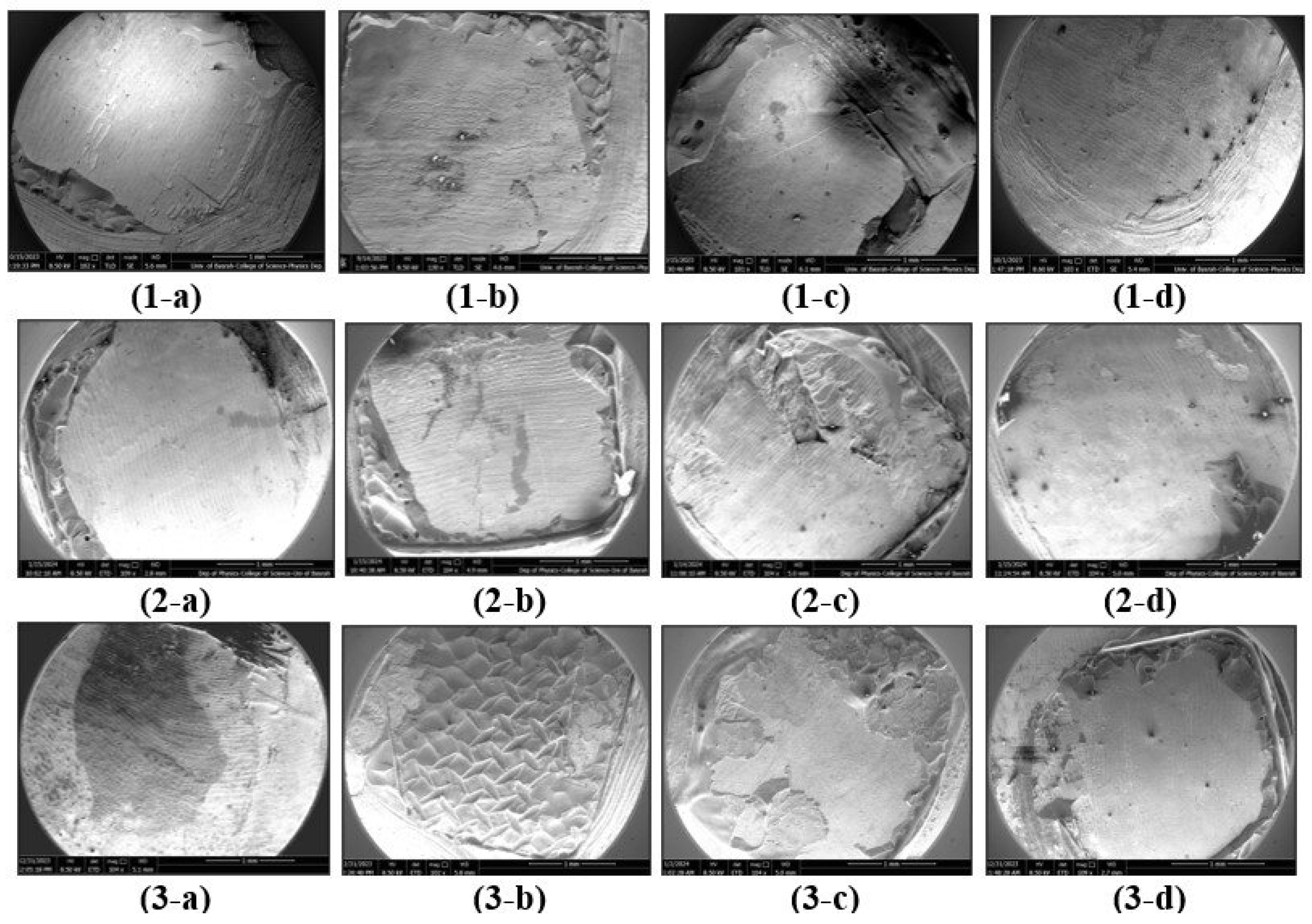

2.2. Phase II: Evaluation of Enamel Damage Index

Three teeth were selected randomly from each group (control and experimental SARs), the crown of each tooth was sectioned mesio-distally through the occlusal central fossae using a metal abrasive disk under running water to obtain the buccal bracket-debonded half, then sputter-coated with gold nanoparticles and examined with Fe-SEM [

4]. The debonded enamel surface was evaluated for signs of enamel damage, if any, according to the Enamel Damage Index [

16], which includes the following categories:

Grade (0): Smooth surface without scratches, and perikymata might be visible.

Grade (1): Acceptable surface, with fine scattered scratches.

Grade (2): Rough surface, with numerous coarse scratches or slight grooves visible.

Grade (3): Surface with coarse scratches, wide grooves, and enamel damage visible to the naked eye.

2.3. Phase III: Assessment of Microhardness

Three discs were used for each group (control and experimental SARs). The discs were prepared by filling a customized teflon mould with the resin, covered using a glass slide and light-cured for 6 seconds from each side. Then the discs were released from the mould and any excess was removed. Vicker’s hardness test was performed three times for each disc using a square-shaped diamond pyramid indenter of a micro-hardness tester (Nanchang Kuang’s Hardness Block Manufacturing Co., Ltd, China) with 136° top angle. The discs were subjected to a load of (100 N= 0.1 HV) for a duration of 10 seconds, and results were reported in terms of hardness Vickers (HV).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Based on the findings of a pilot study, the sample size was determined using G-power software 3.1.7 (Franz Faul, Uni Kiel, Germany). A minimum sample size of 15 specimens per subgroup was required to detect a significant difference with large effect size and 80% power tested with analysis of variance (ANOVA) model at 0.05 alpha level. Data were tested for normality using Shapiro–Wilk test. For parametric data analysis including SBS and micro-hardness, one-way ANOVA test was conducted, followed by Post hoc multiple comparisons test. Kruskal–Wallis test was performed for non-parametric data analysis (ARI). All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS statistical software (version 26, SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) at a level of significance p< 0.05.

3. Results

The parametric data exhibited normal distribution (p > 0.05) according to Shapiro–Wilk test.

Table 1 shows the SBS measurements of the study groups following three artificial aging models, where all groups exhibited mean values within the clinically acceptable range. However, compared with the control, the GSE group showed the highest SBS mean value post the three aging procedures, followed by SrF2 group, then BAG group. A statistically significant difference between groups was revealed via ANOVA. Post hoc comparisons demonstrated a statistically significant difference between thermocycling and 1-month DW incubation for control group, and a statistically significant difference between thermocycling and 1 month acid challenge procedure for BAG group.

According to the stereomicroscopic analysis of the enamel surfaces after bracket debonding, the GSE group exhibited less adhesive remnants compared to other experimental groups; enamel fracture was noticed in all SARs groups except for GSE group. On the other hand, a statistically significant difference between 1-month DW and 1 month acid challenge was demonstrated for BAG and GSE groups (

Table 2).

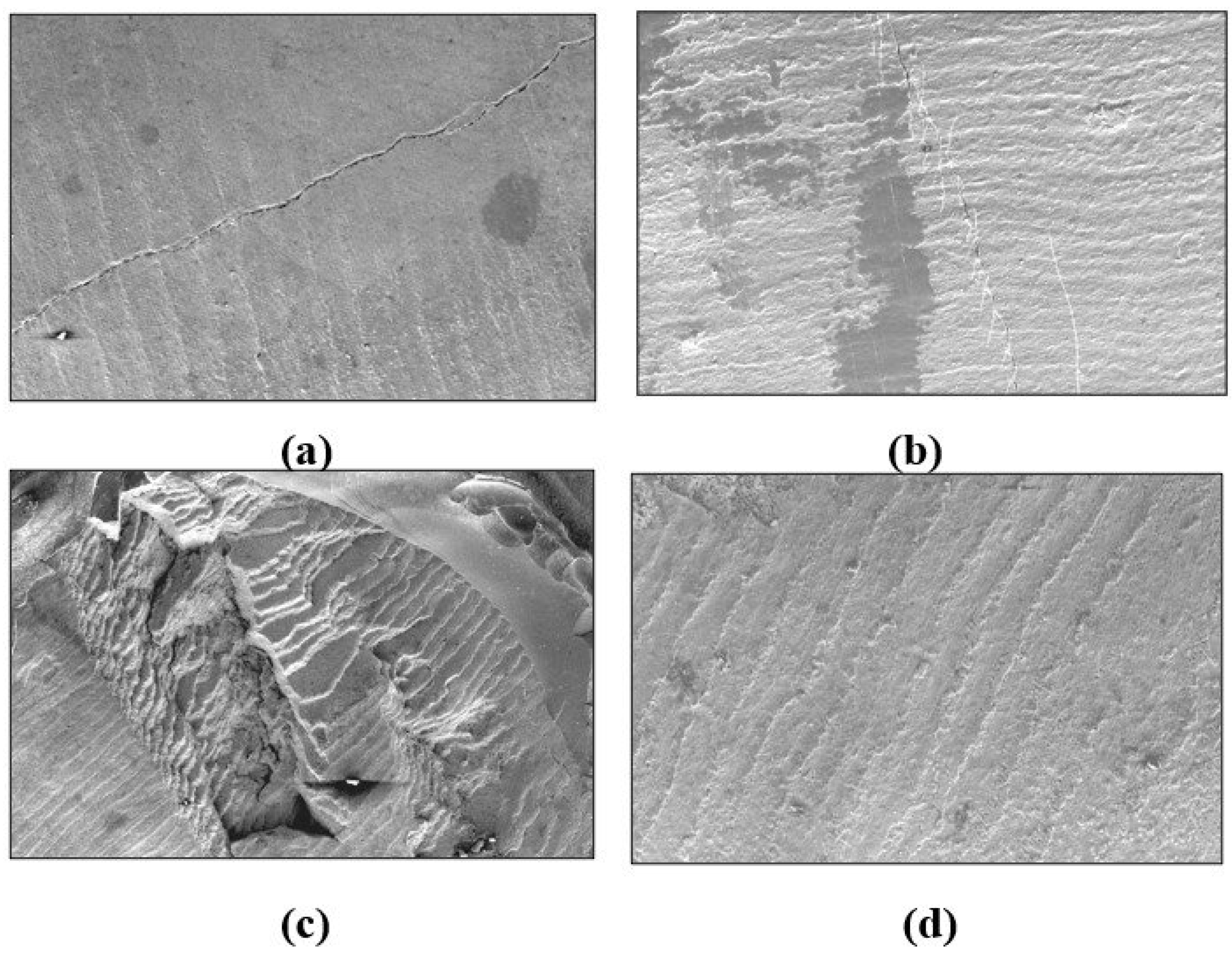

Table 3 shows the microhardness descriptive and inferential statistics of control and experimental SAR discs. The highest mean value was reported by GSE group, followed by SrF2 group, whereas the lowest mean value was demonstrated by BAG group. ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference among groups, and games-howell comparison test showed statistically significant differences among GSE, control and BAG groups. Regarding enamel damage index (EDI),

Figure 2 shows FE-SEM images of debracketed buccal surfaces following the artificial aging procedures where the control and SrF2 groups exhibited enamel damage (cracking). Rough and irregular enamel surfaces with scratches comparable to grades 2 and 3 were depicted by BAG group. The least enamel damage (grades 0 and 1) was associated with the GSE group exhibiting smooth surface or even, fine, scattered scratches (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

The benefits of orthodontic therapy should greatly exceed any potential drawbacks if it is to be beneficial to the patient. For an orthodontic adhesive to be effective, it must have sufficient bond strength to hold brackets during tooth movement, yet preserve the integrity of the enamel surface when brackets are debonded. Bond strengths between 6 and 12 MPa have been reported to be appropriate for clinical performance, and values over this range are typically associated with various types of enamel damage [

3,

4]. Therefore, this study sought developing a modified SAR that avoids unnecessarily excessive bond strengths and targets enamel preservation. This can add to the known advantage of lack of need for priming with SARs, offering superiority over traditional adhesive systems by speeding up orthodontic bonding in clinical settings, particularly when it is challenging to monitor moisture control and isolation conditions [

17,

18]. The developed SARs yielded a clinically acceptable SBS, minimal adhesive remnants, and displayed distinct behaviours regarding enamel damage and micro-hardness; hence the null hypothesis was only partially accepted in terms of SBS and the amount of adhesive remnants.

The prevailing method for studying the deterioration of the tooth-adhesive interface is through artificial aging in water. This process is believed to cause hydrolysis and penetration into the adhesive substance, thus weakening its polymer matrix mechanical properties [

19]. The samples of the current study were exposed to robust artificial aging procedures including thermocycling, 1 month in DW, and 1 month acid challenge. The thermocycling regimen simulates the effects of temperature and water fluctuations in the mouth on dental materials. On the other hand, drinking acidic beverages while undergoing orthodontic treatment might reduce the brackets ability to stay in place and lead to bond failure. This happens when the enamel is softened and the adhesive resin substance degrades causing the filler content to drain out. The complexity of the enamel surface is affected by the concentration and duration of acid exposure [

20,

21,

22]; therefore, the potential enamel resistance was investigated in a laboratory setting via adopting a rigorous acid challenge protocol over 30 days.

All study groups demonstrated clinically acceptable SBS values following the three aging procedures, but the highest mean value was in favour of the GSE, followed by the control, SrF2 then BAG group. Despite the fact that incorporation of a herbal remedy can potentially compromise the mechanical characteristics of dental adhesives, utilizing a grape seed extract, mostly composed of proanthocyanidins (PA), has shown to enhance the structural properties of dentin by promoting collagen cross-linking, resulting in increased resistance to biodegradation. Proanthocyanidins possess both hydrophobic and hydrophilic characteristics, which augment their capacity to form irreversible bonds with various substances such as minerals, proteins, and carbohydrates. Moreover, it has been reported that the use of GSE completely neutralized the bleaching effects and significantly enhanced bond strength before applying bonding treatments to bleached enamel [

23]. This could explain the ability of GSE to neutralise the effect of acidic challenge in this study, in addition to its ability to resist excessive water absorption during thermocycling and 1 month DW storage. On the other hand, it has been shown that strontium plays a role in improving enamel hardness and assist in remineralization [

24,

25]. In a previous study, adding strontium to enamel samples and immersion in acidic solutions resulted in an increase in the strontium ion content on the enamel surface. Yet, strontium ions bear resemblance to calcium ions, undergo a reaction with the dissociated phosphate ions to generate salts on the surface of the enamel leading to changes in enamel physical properties in favour of minimizing the acidity effect [

26].

Previous studies have shown that the aging process does not significantly impact the way brackets fail in terms of the ARI because the strengths of the enamel-adhesive and bracket-adhesive interfaces are essentially identical [

27,

28]. Supporting the results of prior research, no statistically significant differences were observed in this study among SARs groups in terms of ARI scores [

4,

29]. Enamel fracture was demonstrated by the control and other SARs excepting the GSE group, which consistently yielded ARI values less than score 3. Shifting the location of bracket failure closer to the enamel-adhesive interface typically leads to a drop in the amount of remaining adhesive, yet increased stress and a higher likelihood of enamel damage during the process of debonding. However, a low ARI score may confer certain benefits including facile debonding of orthodontic brackets with minimal iatrogenic harm to the enamel, streamlining enamel cleaning procedures following orthodontic therapy. Following the process of adhesive polymerization, resin tags located within the enamel pores create a micromechanical interlocking effect yielding the most optimal bond, yet with higher possibility of enamel damage. Previous studies have shown the effectiveness of GSE in blocking etched-enamel surface pores, hence reducing the possibility of enamel damage [

30,

31].

It has been reported that the microhardness values of dental adhesives are very responsive to subtle alterations in the creation and propagation of the polymer chain. Fillers are usually incorporated into the polymeric portion of adhesives to enhance their strength, stiffness, minimize dimensional alterations, and facilitate handling [

21,

32,

33]. The SAR represents an adhesive that is not completely filled, where silicon concentration is minimal versus higher carbon concentration, and it exhibited a low Vickers micro-hardness value [

34]. Within this particular context, it is important for orthodontists to take into account that the process of polymerization shrinkage becomes more pronounced as the amount of filler decreases. This can result in the production of microgaps between the adhesive and the enamel surface that can promote microleakage, a common shortcoming of SARs; consequently, this may trigger the development of white spot lesions. In contrast, composite resins containing high quantities of filler particles of different sizes have demonstrated superior mechanical characteristics [

33,

35]. The use of additives in this study improved the micro-hardness of the developed SARs in comparison with the plain SAR as the highest mean value was recorded for GSE group, followed by SrF2 group. Statistically significant differences were observed between the control and GSE, and between BAG, SrF2 and GSE groups. However, previous studies reported that the presence of GSE during free radical polymerization caused a decrease in the hardness of the resulting resin. Grape seed extract contains the oligomeric proanthocyanidin molecule, which has a large molecular size that allows it to separate the monomer molecules from the polymer chain, interrupting chain propagation; hence, the integrity of the polymerized material was reduced [

36,

37]. Yet, very small amount of powdered GSE was added to the plain SAR in this study, so that no adsverse effect on resin hardness was observed; these results were in accordance with a more recent study [

38]. Furthermore, the use of SrF2 as a micro-filler with the BAG group has likely contributed to the improvement in the microhardness of the adhesive. This is because inorganic particles normally possess higher stiffness compared to the polymer matrix. The increase in filler content can further enhance the microhardness of the adhesive [

39].

Despite the limitations associated with in vitro studies, this study served as a critical preliminary phase in the collection of initial data and insights regarding novel adhesive formulations that have the potential to address common obstacles encountered during routine orthodontic procedures. Moreover, the remineralisation potential of the developed SARs, their ion release and its long-term effectiveness need to be investigated in the subsequent phase.

5. Conclusions

The GSE group (C+ 1% BAG+ 0.5% GSE) yielded clinically satisfactory SBS, minimal adhesive residue, minimal enamel damage, and highest micro-hardness mean value as compared to the control and other experimental SAR groups.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, DR Mohammed. and AI Ibrahim.; methodology, DR Mohammed.; software, AI Ibrahim.; validation, DR Mohammed., S Deb. and AI Ibrahim.; formal analysis, DR Mohammed.; investigation, DR Mohammed.; resources, DR Mohammed.; data curation, DR Mohammed.; writing—original draft preparation, DR Mohammed.; writing—review and editing, S Deb and AI Ibrahim.; visualization, AI Ibrahim. and S Deb; supervision, AI Ibrahim and S Deb.; project administration, DR Mohammed. and AI Ibrahim ; funding acquisition, DR Mohammed. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author can provide the data that support the study findings upon request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ibrahim, A.I.; Al-Hasani, N.R.; Thompson, V.P.; Deb, S. In vitro bond strengths post thermal and fatigue load cycling of sapphire brackets bonded with self-etch primer and evaluation of enamel damage. J Clin Exp Dent 2020;12:e22-30. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, W.L.; Piva, E.; Silva, A.F. Bond strength of universal adhesives: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 2015;43:765-76. [CrossRef]

- Hama, T.; Namura, Y.; Nishion, Y.; Yoneyama, T.; Shimizu, N. Effect of orthodontic adhesive thickness on force required by debonding pliers. J Oral Sci 2014;56:185-90. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.I.; Thompson, V.P.; Deb, S. A Novel Etchant System for Orthodontic Bracket Bonding. Sci Rep 2019;9:9579. [CrossRef]

- Garma, N.M.H.; Ibrahim, A.I. Bond Strength Survival of a Novel Calcium Phosphate-Enriched Orthodontic Self-Etching System after Various Ageing Protocols: An In Vitro Study. Int J Dent 2022;3960362. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, T.M.A.; Behrens, B.A.; Nascimento, D.; Retamoso, L.B.; Lon, L.F.S.; Tanaka, O.; Filho, O.G. Blood contamination efect on shear bond strength of an orthodontic hydrophilic resin. J Appl Oral Sci 2012;20:89-93. [CrossRef]

- Latta, M.A.; Radniecki, S.M. Bond Strength of Self-Adhesive Restorative Materials Affected by Smear Layer Thickness but not Dentin Desiccation. J Adhes Dent 2020;22:79-84. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinipour, Z.S.; Heidari, A.; Shahrabi, M.; Poorzandpoush, K. Microleakage of a self-adhesive flowable composite, a self-adhesive fissure sealant and a conventional fissure sealant in permanent teeth with/without saliva contamination. FID 2019;16:239. [CrossRef]

- Skallevold, H.E.; Rokaya, D.; Khurshid, Z.; Zafar, M.S. Bioactive glass applications in dentistry. Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:5960. [CrossRef]

- Bakry, A.S.; Takahashi, H.; Otsuki, M.; Tagami, J. Evaluation of new treatment for incipient enamel demineralization using 45S5 bioglass. Dent Mater 2014;30:314-20. [CrossRef]

- Abbassy, M.A.; Bakry, A.S.; Alshehri, N.I.; Alghamdi, T.M.; Rafiq, S.A.; Aljeddawi, D.H.; et al. 45S5 Bioglass paste is capable of protecting the enamel surrounding orthodontic brackets against erosive challenge, J Orthod Sci 2019;8. [CrossRef]

- Santocildes-Romero, M.E.; Crawford, A.; Hatton, P.V.; Goodchild, R.L.; Reaney, I.M.; Miller, C.A. The osteogenic response of mesenchymal stromal cells to strontium-substituted bioactive glasses. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2015;9:619-31. [CrossRef]

- Delimont, N.M.; Carlson, B.N. Prevention of Dental Caries by Grape Seed Extract Supplementation: A Systematic Review. JNH 2020;26:43-52. [CrossRef]

- Proença, M.A.M.; Carvalho, E.M.; Silva, A.S.; Ribeiro, G.A.C.; Ferreira, P.V.C.; Carvalho, C.N., et al. Orthodontic resin containing bioactive glass: Preparation, physicoche-mical characterization, antimicrobial activity, bioactivity and bonding to enamel. Int J Adhesion Adhes 2020;99:102575. [CrossRef]

- Artun, J.; Bergland, S. Clinical trials with crystal growth conditioning as an alternative to acid-etch enamel pretreatment. Am J Orthod 1984;85:333-40. [CrossRef]

- Schuler, F.S.; Van Waes, H. SEM-evaluation of enamel surfaces after removal of fixed orthodontic appliances. Am J Dent 2003;16:390-4.

- Hasan, L.A. Evaluation the properties of orthodontic adhesive incorporated with nano-hydroxyapatite particles. Saudi Dent J 2021;33:1190-6. [CrossRef]

- Yashpal; Chitra, P. A comparison of the efficacy of a primerless orthodontic bonding adhesive as compared to conventional materials: an in vitro study. Dent J Adv Stud 2016;4:49-55. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Lu, Z.; Qian, M.; Xie, H.; Tay, F.R. The effects of water on degradation of the zirconia-resin bond. J Dent 2017;64:23-9. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, N.; Weir, MD.; Bai, Y.; Xu, H.H.K. Novel multifunctional dental cement to prevent enamel demineralization near orthodontic brackets. J Dent 2017;64:58-67. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.R.; Al-Hasani, N.R.; Mahmood, M.A.; Ibrahim, A.I. Effect of Amoxicillin and Azithromycin Suspensions on Microhardness of Sliver Reinforced and Nano Resin-Modified Glass Ionomers: An In Vitro Study. Dent Hypotheses 2023;14:32-6. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim HA, Deb S, Ibrahim AI. In vitro assessment of bracket adhesion post enamel conditioning with a novel etchant paste. J Bagh Coll Dent 2023;35:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Chaichana, W.; Insee, K.; Chanachai, S.; Benjakul, S.; Aupaphong, V.; Naruphontjirakul, P.; et al. Physical/mechanical and antibacterial properties of orthodontic adhesives containing Sr-bioactive glass nanoparticles, calcium phosphate, and andrographolide. Sci Rep 2022;12:6635. [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.H.; Spector, P.C.; Curzon, M.E. Pre- and posteruptive effects of low doses of strontium on dental caries in the rat. Caries Res 1980;14:341e6. [CrossRef]

- Athanassouli, T.M.; Papastathopoulos DS, Apostolopoulos AX. Dental caries and strontium concentration in drinking water and surface enamel. J Dent Res 1983;62:989e91. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y-L.; Chang, H-H.; Chiang, Y-C.; Lin, C-H.; Lin, C-P. Strontium ion can significantly decrease enamel demineralization and prevent the enamel surface hardness loss in acidic environment. JFMA 2019;118:39-49. [CrossRef]

- Al-Duliamy, M.J. In vivo plaque count of Streptococcus Mutans around orthodontic brackets bonded with two different adhesives. J Bagh Coll Dent 2014;26:175-9. [CrossRef]

- Garma, N.M.H.; Ibrahim, A.I. Development of a remineralizing calcium phosphate nanoparticle-containing self-etching system for orthodontic bonding. Clin Oral Invest 2023;27:1483-97. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, H.A.; Deb, S.; Ibrahim, A.I. Performance of novel enamel-conditioning calcium-phosphate pastes for orthodontic bonding: An in vitro study. J Clin Exp Dent 2023;15:e102-9. [CrossRef]

- Sofan, E.; Sofan, A.; Palaia, G.; Tenore, G.; Romeo, U.; Migliau, G. Classification review of dental adhesive systems: from the IV generation to the universal type. Ann Stomatol 2017;8:1-17. [CrossRef]

- Haithem, M.H.; Tahlawy, A.A.E.; Saniour, S.H. Assessment of the Remineralizing Efficacy of Grape Seed Extract vs Sodium Fluoride on Surface and Subsurface Enamel Lesions: An In Vitro Study. J Contemp Dent Pract 2022;23:1237-44. [CrossRef]

- Faltermeier, A.; Rosentritt, M.; Reicheneder, C.; Mussig, D. Experimental composite brackets: influence of filler level on the mechanical properties. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;130:e9-699.e14. [CrossRef]

- Faltermeier, A.; Rosentritt, M.; Faltermeier, R.; Reicheneder, C.; Mussig D. Influence of filler level on the bond strength of orthodontic adhesives. Angle Orthod 2007;77:494-8. [CrossRef]

- Vilchis, R.J.S.; Hotta, Y.; Yamamoto, K. Examination of Six Orthodontic Adhesives with Electron Microscopy, Hardness Tester and Energy Dispersive X-ray Microanalyzer. Angle Orthod 2008;78:655-61. [CrossRef]

- Arhun, N.; Arman, A.; Cehreli, S.B.; Arikan, S.; Karabulut, E.; Gulsahi, K. Microleakage beneath ceramic and metal brackets bonded with a conventional and an antibacterial adhesive system. Angle Orthod 2006;76:1028-34. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Ferracane, J.L.; Prahl, S.A. A pilot study of a simple photon migration model for predicting depth of cure in dental composite. Dent Mater 2005;21:1075-86. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.F.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Consani, S.; Prahl, S.A.; Ferracane, J.L. Influence of photoinitiator type on the rate of polymerization, degree of conversion, hardness and yellowing of dental resin composites. Dent Mater 2008;24:1169-77. [CrossRef]

- Epasinghe, D.J.; You, C.K.Y.; Burrow, M.F. Mechanical properties, water sorption characteristics, and compound release of grape seed extract-incorporated resins. J Appl Oral Sci 2017;25:412-9. [CrossRef]

- Go, H-B.; Lee, M-J.; Seo, J-Y.; Byun, S-Y.; Kwon, J-S. Mechanical properties and sustainable bacterial resistance effect of strontium modifed phosphate based glass microfller in dental composite resins. Sci Rep 2023;13:17763. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).