Submitted:

03 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

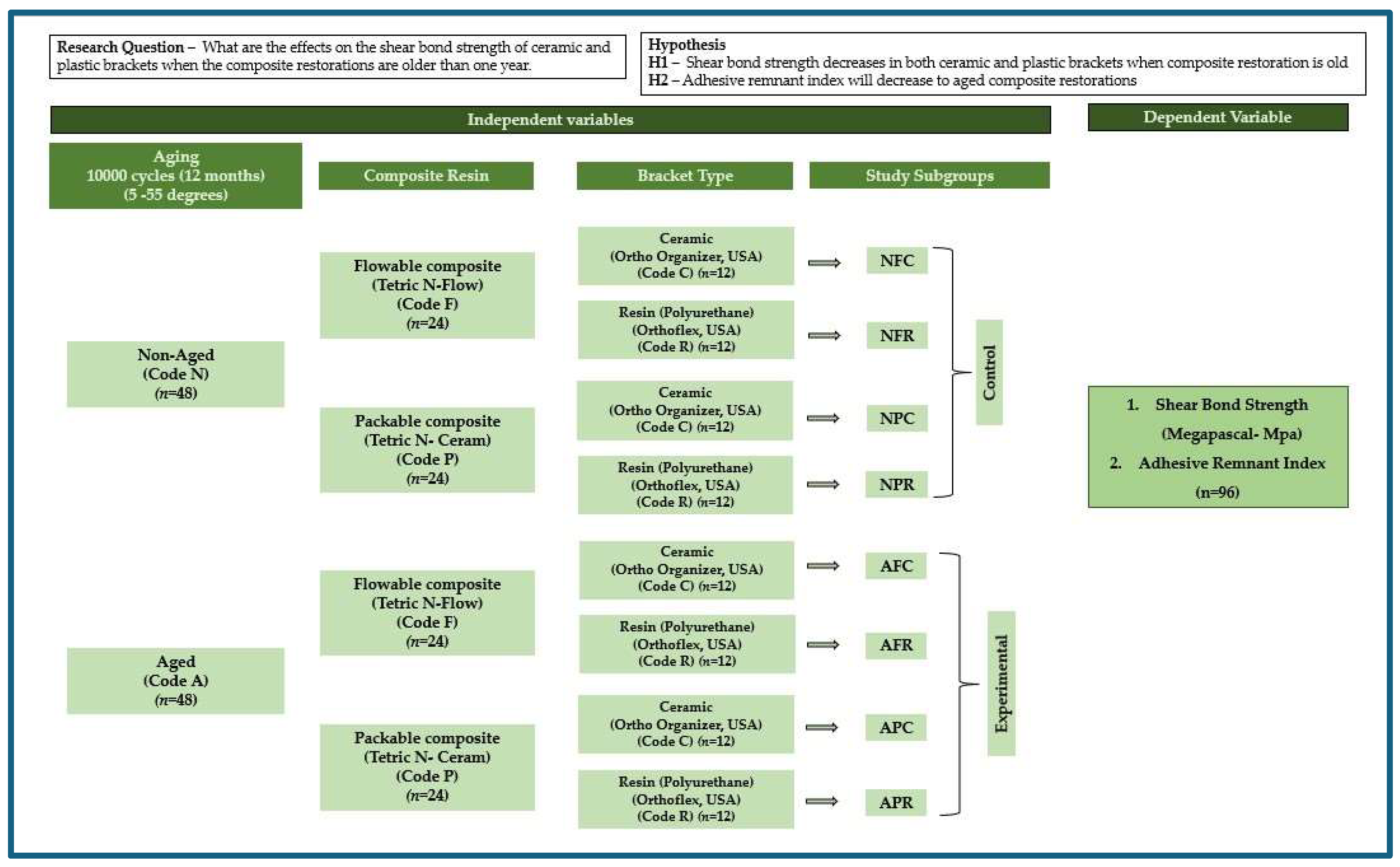

2. Materials And Methods

3. Sample Preparation and Experimental Intervention

4. Orthodontic Bracket Bonding

5. Measures, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

6. Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bayram, M.; YeşIlyurt, C.; KuşGöZ, A.; Ülker, M.; Nur, M. Shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets to aged resin composite surfaces: effect of surface conditioning. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 33, 174–179. [CrossRef]

- Adawi, H.; Reddy, K.N.; Mattoo, K.; Najmi, N.; Arishi, M.; Ageeli, A.; Bahri, A.; Khateeb, S.U.; Sainudeen, S.; Baba, S.M.; et al. Effects of Artificial Aging of Direct Resin Nano-Hybrid Composite on Mean Bond Strength Values for Veneer Ceramic Samples. Med Sci. Monit. 2024, 30, e945243-1–e945243-11. [CrossRef]

- Al Jabbari, Y.S.; Al Taweel, S.M.; Al Rifaiy, M.; Alqahtani, M.Q.; Koutsoukis, T.; Zinelis, S. Effects of surface treatment and artificial aging on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets bonded to four different provisional restorations. Angle Orthod. 2014, 84, 649–655. [CrossRef]

- Goymen, M.; Topcuoglu, T.; Topcuoglu, S.; Akin, H. Effect of Different Temporary Crown Materials and Surface Roughening Methods on the Shear Bond Strengths of Orthodontic Brackets. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Rathi, N.; Jain, K.; A Mattoo, K. Placing an implant fixture during ongoing orthodontic treatment. Int. J. Med Sci. 2019, 6, 19–21. [CrossRef]

- Bakhadher, W.; Halawany, H.; Talic, N.; Abraham, N.; Jacob, V. Factors Affecting the Shear Bond Strength of Orthodontic Brackets – a Review of In Vitro Studies. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic) 2015, 58, 43–48. [CrossRef]

- Blakey, R.; Mah, J. Effects of surface conditioning on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets bonded to temporary polycarbonate crowns. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 138, 72–78. [CrossRef]

- Mavreas, D.; Athanasiou, A.E. Factors affecting the duration of orthodontic treatment: a systematic review. Eur. J. Orthod. 2008, 30, 386–395. [CrossRef]

- Oskoee, P.A.; Kachoei, M.; Rikhtegaran, S.; Fathalizadeh, F.; Navimipour, E.J. Effect of surface treatment with sandblasting and Er,Cr:YSGG laser on bonding of stainless steel orthodontic brackets to silver amalgam. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2012, 17, e292–e296. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, I.R. A Review of Direct Orthodontic Bonding. Br. J. Orthod. 1975, 2, 171–178. [CrossRef]

- Eliades, T.; A Brantley, W. The inappropriateness of conventional orthodontic bond strength assessment protocols. Eur. J. Orthod. 2000, 22, 13–23. [CrossRef]

- Hajrassie, M.K.; Khier, S.E. In-vivo and in-vitro comparison of bond strengths of orthodontic brackets bonded to enamel and debonded at various times. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 131, 384–390. [CrossRef]

- Linklater, R.A.; Gordon, P.H. AnEx VivoStudy to Investigate Bond Strengths of Different Tooth Types. J. Orthod. 2001, 28, 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Ash, S.; Hay, N. Adhesive Pre-coated Brackets, a Comparative Clinical Study. Br. J. Orthod. 1996, 23, 325–329. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Ab Rahman, N.; Alam, M.K. Assessment of in vivo bond strength studies of the orthodontic bracket-adhesive system: A systematic review. Eur. J. Dent. 2018, 12, 602–609. [CrossRef]

- E Bishara, S.; VonWald, L.; Laffoon, J.F.; Warren, J.J. The effect of repeated bonding on the shear bond strength of a composite resin orthodontic adhesive.. 2000, 70, 435–41. [CrossRef]

- Imani, M.M.; Delavarian, M.; Rahimi, F.; Mohammadi, R. Shear bond strength of ceramic and metal brackets bonded to enamel using color-change adhesive. Dent. Res. J. 2019, 16, 233–238. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Silva, T.; Otoni, R.P.; Magalhães, A.A.M.; Ramos, G.M.; Gomes, T.R.; Rego, T.M.; Araújo, C.T.P.; Santos, C.C.d.O. Comparative Analysis of Shear Bond Strength of Steel and Ceramic Orthodontic Brackets Bonded with Six Different Orthodontic Adhesives. Int. J. Odontostomatol. 2020, 14, 658–663. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, C.M.; da Silva, V.R.; Pecorari, V.G.A.; Martins, L.R.M.; Santos, E.C.A. SHEAR BOND STRENGTH OF DIFFERENT ORTHODONTIC BRACKET BONDING SYSTEMS ON SALIVA- CONTAMINATED ENAMEL: IN VITRO. J. Media Crit. 2024, 10, e142–e142. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Tandon, P.; Nagar, A.; Singh, G.; Singh, A.; Chugh, V. A comparison of shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets bonded with four different orthodontic adhesives. J. Orthod. Sci. 2014, 3, 29–33. [CrossRef]

- Goracci, C.; Margvelashvili, M.; Giovannetti, A.; Vichi, A.; Ferrari, M. Shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets bonded with a new self-adhering flowable resin composite. Clin. Oral Investig. 2012, 17, 609–617. [CrossRef]

- Abu Alhaija, E.S.J.; Abu AlReesh, I.A.; AlWahadni, A.M.S. Factors affecting the shear bond strength of metal and ceramic brackets bonded to different ceramic surfaces. Eur. J. Orthod. 2009, 32, 274–280. [CrossRef]

- Babaahmadi, F.; Aghaali, M.; Saleh, A.; Mehdipour, A. Comparing the Effect of Zirconia Surface Conditioning Using Nd: YAG Laser and Conventional Method on Shear Bond Strength of Ceramic Brackets to Zirconia Surface: An In vitro Study. J. Maz. Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 33, 139–145.

- Pinho, M.; Manso, M.C.; Almeida, R.F.; Martin, C.; Carvalho, Ó.; Henriques, B.; Silva, F.; Ferreira, A.P.; Souza, J.C.M. Bond Strength of Metallic or Ceramic Orthodontic Brackets to Enamel, Acrylic, or Porcelain Surfaces. Materials 2020, 13, 5197. [CrossRef]

- Samruajbenjakul, B.; Kukiattrakoon, B. Shear bond strength of ceramic brackets with different base designs to feldspathic porcelains. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 571–576.

- Chunhacheevachaloke, E.; Tyas, M.J. Shear bond strength of ceramic brackets to resin-composite surfaces. Australas. Orthod. J. 1997, 15, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Danha, L.S.; Rafeeq, R.A. Assessment of Effect of Flowable Composite on the Shear Bond Strength of Sapphire Bracket Bonded to Composite Restoration: An in Vitro Study. Dent. Hypotheses 2024, 15, 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Della Bona, A.; Kochenborger, R.; Di Guida, L.A. Bond strength of ceramic and metal orthodontic brackets to aged resin-based composite restorations. Curr. Dent. 2019, 1, 40–15.

- Eslamian, L.; Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Mousavi, N.; Ghasemi, A. A comparative study of shear bond strength between metal and ceramic brackets and artificially aged composite restorations using different surface treatments. Eur. J. Orthod. 2011, 34, 610–617. [CrossRef]

- Eslamian, L.; Borzabadi-Farahani, A.; Mousavi, N.; Ghasemi, A. The effects of various surface treatments on the shear bond strengths of stainless steel brackets to artificially-aged composite restorations. Australas. Orthod. J. 2011, 27, 28–32. [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh, S.; Alimohammadi, G.; Nik, T.H.; Etemadi, A.; Tanbakuchi, B. In vitro evaluation of shear bond strength of orthodontic metal brackets to aged composite using a self-adhesive composite: Effect of surface conditioning and different bonding agents. Int. Orthod. 2020, 18, 528–537. [CrossRef]

- Yassaei, S.; Davari, A.; Moghadam, M.G.; Kamaei, A. Comparison of Shear Bond Strength of RMGI and Composite Resin for Orthodontic Bracket Bonding. 2014, 11, 282–289.

- Tahmasbi, S.; Badiee, M.; Modarresi, M. Shear Bond Strength of Orthodontic Brackets to Composite Restorations Using Universal Adhesive. 2019, 20, 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Tayebi, A.; Fallahzadeh, F.; Morsaghian, M. Shear bond strength of orthodontic metal brackets to aged composite using three primers. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e749–e755. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.A.; de Morais, A.V.; Brunetto, D.P.; Ruellas, A.C.d.O.; de Araujo, M.T.S. Comparison of shear bond strength of orthodontics brackets on composite resin restorations with different surface treatments. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2013, 18, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Büyükyilmaz, T.; Zachrisson, B.U. Improved orthodontic bonding to silver amalgam. Part 2. Lathe-cut, admixed, and spherical amalgams with different intermediate resins.. 1998, 68, 337–44. [CrossRef]

- Zachrisson, B.U.; Büyükyilmaz, T.; O Zachrisson, Y. Improving orthodontic bonding to silver amalgam.. 1995, 65, 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Haber, D.; Khoury, E.; Ghoubril, J.; Cirulli, N. Effect of Different Surface Treatments on the Shear Bond Strength of Metal Orthodontic Brackets Bonded to CAD/CAM Provisional Crowns. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 38. [CrossRef]

- Goracci, C.; Özcan, M.; Franchi, L.; Di Bello, G.; Louca, C.; Vichi, A. Bracket bonding to polymethylmethacrylate-based materials for computer-aided design/manufacture of temporary restorations: Influence of mechanical treatment and chemical treatment with universal adhesives. Korean J. Orthod. 2019, 49, 404–412. [CrossRef]

- Rambhia, S.; Heshmati, R.; Dhuru, V.; Iacopino, A. Shear Bond Strength of Orthodontic Brackets Bonded to Provisional Crown Materials Utilizing Two Different Adhesives. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 784–789. [CrossRef]

- Najafi, H.Z.; Moradi, M.; Torkan, S. Effect of different surface treatment methods on the shear bond strength of orthodontic brackets to temporary crowns. Int. Orthod. 2019, 17, 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Chay, S.H.; Wong, S.L.; Mohamed, N.; Chia, A.; Yap, A.U.J. Effects of surface treatment and aging on the bond strength of orthodontic brackets to provisional materials. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 132, 577.e7–577.e11. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, S.Y.; Abu Showmi, T.H.; Alzaghran, S.H.; Albaqawi, H.; Alrashoudi, L.; Gad, M.M. Bond Strength of Orthodontic Brackets to Temporary Crowns: In Vitro Effects of Surface Treatment. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Makou, M.; Papadopoulos, T.; Eliades, G. Laboratory evaluation of modern plastic brackets. Eur. J. Orthod. 2011, 34, 595–602. [CrossRef]

- De Pulido, L.G.; Powers, J.M. Bond strength of orthodontic direct-bonding cement-plastic bracket systems in vitro. Am. J. Orthod. 1983, 83, 124–130.

- Guan, G.; Takano-Yamamoto, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Hattori, T.; Ishikawa, K.; Suzuki, K. Shear bond strengths of orthodontic plastic brackets. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2000, 117, 438–443. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-K.; Chang, L.-T.; Chuang, S.-F.; Shieh, D.-B. Shear bond strengths of plastic brackets with a mechanical base.. 2002, 72, 141–5. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-K.; Chuang, S.-F.; Chang, C.-Y.; Pan, Y.-J. Comparison of initial shear bond strengths of plastic and metal brackets.. Eur. J. Orthod. 2004, 26, 531–534. [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.-H.; Chae, J.-M.; Chang, N.-Y. Color Stability of Various Plastic and Ceramic Brackets: An In Vitro Study. Clin. J. Korean Assoc. Orthod. 2022, 12, 189–199. [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, G.; Premkumar, S.; Amit, K. Assessment Of Enamel Loss After Debonding Of Ceramic, Composite Plastic And Metal Brackets-An In Vitro Study.. J. Contemp. Orthod. 2023, 3, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Miyagawa, Y.; Endo, T. Effects of plastic bracket primer on the shear bond strengths of orthodontic brackets. J. Dent. Sci. 2020, 16, 424–430. [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, T.; Nagata, S.; Ishikawa, T.; Tanimoto, Y. Mechanical characterization of aesthetic orthodontic brackets by the dynamic indentation method. Dent. Mater. J. 2022, 41, 860–867. [CrossRef]

- Farhadifard, H.; Rezaei-Soufi, L.; Farhadian, M.; Shokouhi, P. Effect of different surface treatments on shear bond strength of ceramic brackets to old composite. Biomater. Res. 2020, 24, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Seyhan-Cezairli, N.; Serkan-Küçükekenci, A.; Başoğlu, H. Evaluation of shear bond strength between orthodontic brackets and three aged bulk fill composites. Odovtos Int. J. Dent. Sci. 2019, 21, 89–99.

- The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms 2023. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 130, e1–e3. [CrossRef]

- Alqarawi, F.K.; Al-Makramani, B.M.A.; Gangadharappa, P.; Mattoo, K.; Hadi, M.; Alamri, M.; Alsubaiy, E.F.; Alqahtani, S.M.; Sayed, M.E. Comparative Assessment of the Influence of Various Time Intervals upon the Linear Accuracy of Regular, Scannable, and Transparent Vinyl Polysiloxane-Based Bite Registration Materials for Indirect Dental Restoration Fabrication. Polymers 2024, 17, 52. [CrossRef]

- Reicheneder, C.; Baumert, U.; Gedrange, T.; Proff, P.; A Faltermeier, A.; Muessig, D. Frictional properties of aesthetic brackets. Eur. J. Orthod. 2007, 29, 359–365. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.Y.; Agarwal, D.K.; Gupta, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Ansar, J.; Bhandari, R. Shear bond strength of ceramic brackets with different base designs: Comparative in-vitro study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. JCDR 2016, 10, ZC64.

- Özcan, M.; Vallittu, P.K.; Peltomäki, T.; Huysmans, M.-C.; Kalk, W. Bonding polycarbonate brackets to ceramic: Effects of substrate treatment on bond strength. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2004, 126, 220–227. [CrossRef]

- Dootz, E.; Koran, A.; Craig, R. Physical property comparison of 11 soft denture lining materials as a function of accelerated aging. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1993, 69, 114–119. [CrossRef]

- Seeliger, J.H.; Botzenhart, U.U.; Gedrange, T.; Kozak, K.; Stepien, L.; Machoy, M. Enamel shear bond strength of different primers combined with an orthodontic adhesive paste. Biomed. Eng. / Biomed. Tech. 2017, 62, 415–420. [CrossRef]

- Neto, H.N.M.; Leite, J.V.C.; de Medeiros, J.M.; Campos, D.e.S.; Muniz, I.d.A.F.; De Andrade, A.K.M.; Duarte, R.M.; De Souza, G.M.; Lima, R.B.W. Scoping review: Effect of surface treatments on bond strength of resin composite repair. J. Dent. 2023, 140, 104737. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.-H.A.-A.; Sindi, A.S.; Atout, A.M.; Morsy, M.S.; Mattoo, K.A.; Obulareddy, V.T.; Mathur, A.; Mehta, V. Assessment of Microhardness of Bulk-Fill Class II Resin Composite Restorations Performed by Preclinical Students: An In Vitro Study. Eur. J. Gen. Dent. 2024, 13, 158–164. [CrossRef]

- Viazis, A.D.; Cavanaugh, G.; Bevis, R.R. Bond strength of ceramic brackets under shear stress: An in vitro report. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1990, 98, 214–221. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Sayed, M.E.; Gupta, B.; Patel, A.; Mattoo, K.; Alotaibi, N.T.; Alnemi, S.I.; Jokhadar, H.F.; Mashhor, B.M.; Othman, M.A.; et al. Comparison of Composite Resin (Duo-Shade) Shade Guide with Vita Ceramic Shades Before and After Chemical and Autoclave Sterilization. Med Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e940949–e940949-12. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N.; Khosla, A.; Jain, S.; Mattoo, K.; Singla, I.; Maini, A.P.; Manzoor, S. Effect of storage media on the flexural strength of heat and self cure denture base acrylic resins–an invitro study. Ann. Rom. Soc. Cell Biol. 2021, 11743–11750.

- Sibi, A.S.; Kumar, S.; Sundareswaran, S.; Philip, K.; Pillai, B. An in vitro evaluation of shear bond strength of adhesive precoated brackets. J. Ind. Orthod. Soc. 2014, 48, 97–103.

- Sayed, M.; Reddy, N.K.; Reddy, N.R.; Mattoo, K.A.; Jad, Y.A.; Hakami, A.J.; Hakami, A.K.; Dighriri, A.M.; Hurubi, S.Y.; Hamdi, B.A.; et al. Evaluation of the Milled and Three-Dimensional Digital Manufacturing, 10-Degree and 20-Degree Preparation Taper, Groove and Box Auxiliary Retentive Features, and Conventional and Resin-Based Provisional Cement Type on the Adhesive Failure Stress of 3 mm Short Provisional Crowns. Med Sci. Monit. 2023, 30, e943237–e943237-16. [CrossRef]

| Materials | Trade Name /Manufacturer | Specifications/Features |

| Tetric N-Ceram Code P |

|

|

| Tetric N-Flow Shade A2 Filling material Code F |

|

|

| Assure Plus bonding resin |

|

|

| Transbond XT Light cure adhesive paste |

3M Unitek, South Peck Road Monrovia, CA, Los Angeles USA |

|

| Ceramic bracket Code C |

Ortho organizer San Marcos, CA, USA |

|

| Resin (polyurethane) bracket Code R |

Orthoflex, Ortho Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA |

|

| Thermocycling machine |

Model 1100, SD Mechatronik, Bayern, Germany |

|

| Teflon mold | Guarniflon Spa, Castelli Calepio BG, Italy |

|

| Independent Variable | Composite Type | Bracket Type | n | Subgroup | Mean | SD | dF | F Statistic | p-Value |

| Control Groups Non-Aged (Code N) (n = 48) |

Flowable (Code F) (Tetric N-Flow) (n = 24) |

Ceramic (Polycrystalline) (Code C) |

12 | NFC | 8.196 | 0.544 | 7 | 35.502 | 0.0000 * |

| Resin (Polyurethane) (Code R) |

12 | NFR | 5.838 | 0.684 | |||||

| Packable (Code P) (Tetric N-Ceram) (n = 24) |

Ceramic (Polycrystalline) (Code C) |

12 | NPC | 6.469 | 0.645 | ||||

| Resin (Polyurethane) (Code R) |

12 | NPR | 5.141 | 0.801 | |||||

| Experimental Groups Aged (Code A) (n = 48) |

Flowable (Code F) (Tetric N-Flow) (n = 24) |

Ceramic (Polycrystalline) (Code C) |

12 | AFC | 7.73 | 0.545 | |||

| Resin (Polyurethane) (Code R) |

12 | AFR | 5.558 | 0.694 | |||||

| Packable (Code P) (Tetric N-Ceram) (n = 24) |

Ceramic (Polycrystalline) (Code C) |

12 | APC | 6.348 | 0.776 | ||||

| Resin (Polyurethane) (Code R) |

12 | APR | 4.895 | 0.746 |

| Subgroups | NFC | AFC | NPC | APC | NFR | NPR | AFR | APR |

| NFC | 0.47 | 1.73 | 1.85 | 2.36 | 2.64 | 3.06 | 3.3 | |

| 0.708 | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | ||

| AFC | 0.47 | 1.26 | 1.38 | 1.89 | 2.17 | 2.59 | 2.83 | |

| 0.708 | 0.0005 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | ||

| NPC | 1.73 | 1.26 | 0.120 | 0.630 | 0.910 | 1.33 | 1.57 | |

| 0.0000 * | 0.0005 * | 0.9999 | 0.3321 | 0.0332 * | 0.0002 * | 0.0000 * | ||

| APC | 1.85 | 1.38 | 0.120 | 0.51 | 0.79 | 1.21 | 1.45 | |

| 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.9999 | 0.609 | 0.103 | 0.0010 * | 0.0000 * | ||

| NFR | 2.36 | 1.89 | 0.630 | 0.51 | 0.28 | 0.70 | 0.94 | |

| 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.3321 | 0.609 | 0.973 | 0.214 | 0.023 * | ||

| NPR | 2.64 | 2.17 | 0.910 | 0.79 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.66 | |

| 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0332 * | 0.103 | 0.973 | 0.812 | 0.270 | ||

| AFR | 3.06 | 2.59 | 1.33 | 1.21 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.25 | |

| 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0002 * | 0.0010 * | 0.214 | 0.812 | 0.987 | ||

| APR | 3.3 | 2.83 | 1.57 | 1.45 | 0.94 | 0.66 | 0.25 | |

| 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.0000 * | 0.023 * | 0.270 | 0.987 |

| ARI Score Distributions | Failure Mode Distribution | |||||||

| Subgroups | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | C | A | M | |

| NFC | N | 1 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 3 |

| % | 8.33% | 41.67% | 41.67% | 8.33% | 75.00% | 0.00% | 25.00% | |

| AFC | N | 0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| % | 0.00% | 58.33% | 41.67% | 0.00% | 66.67% | 0.00% | 33.33% | |

| NPC | N | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| % | 8.33% | 16.67% | 58.33% | 16.67% | 41.67% | 8.33% | 50.00% | |

| APC | N | 1 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 0 |

| % | 8.33% | 66.67% | 25.00% | 0.00% | 83.33% | 16.67% | 0.00% | |

| NFR | N | 3 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 |

| % | 25.00% | 33.33% | 41.67% | 0.00% | 8.33% | 83.33% | 8.33% | |

| NPR | N | 2 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 |

| % | 16.67% | 25.00% | 58.33% | 0.00% | 8.33% | 83.33% | 8.33% | |

| AFR | N | 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| % | 25.00% | 50.00% | 25.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 100.00% | 0.00% | |

| APR | N | 3 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 |

| % | 25.00% | 41.67% | 33.33% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 100.00% | 0.00% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).