Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

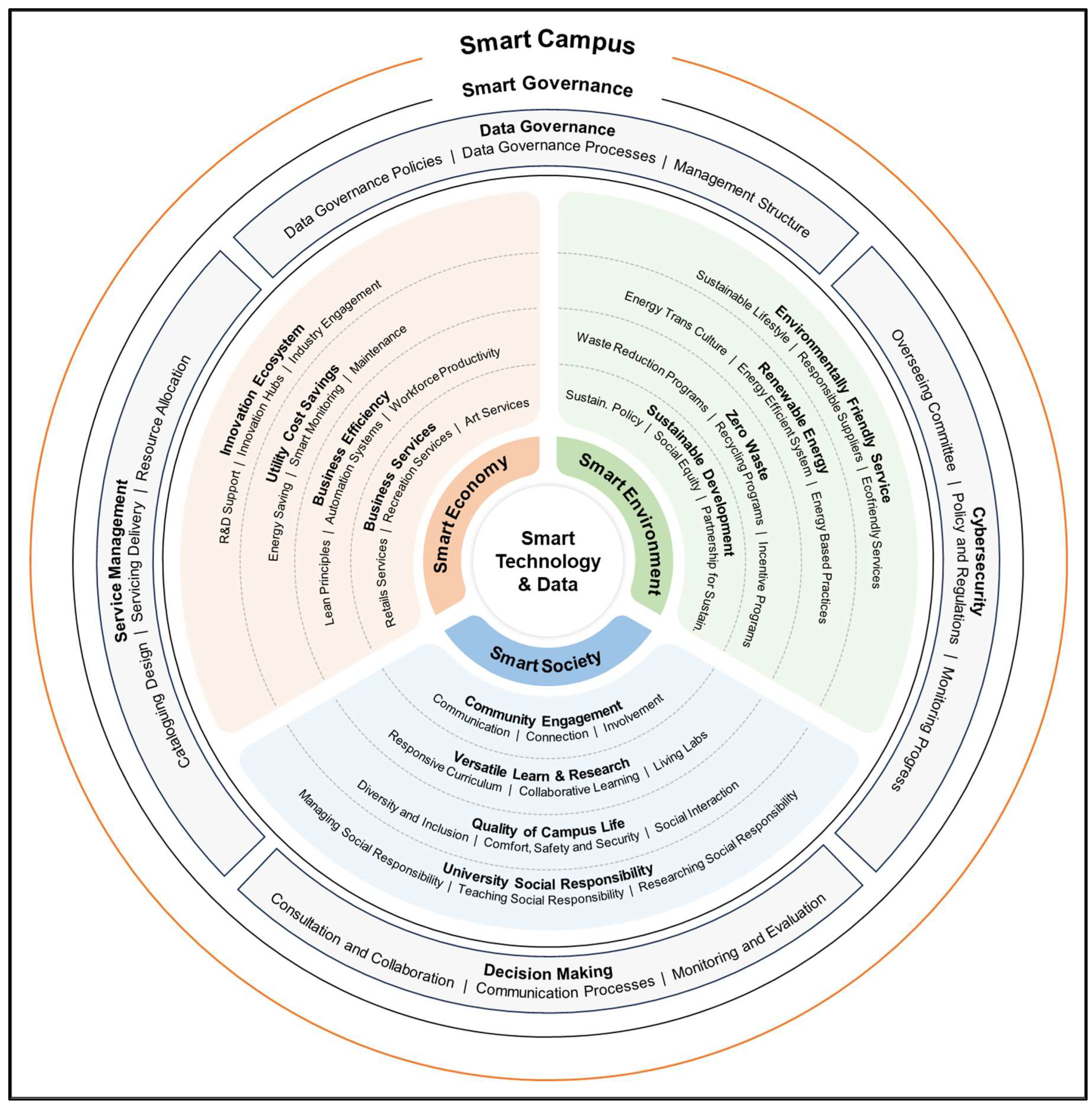

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

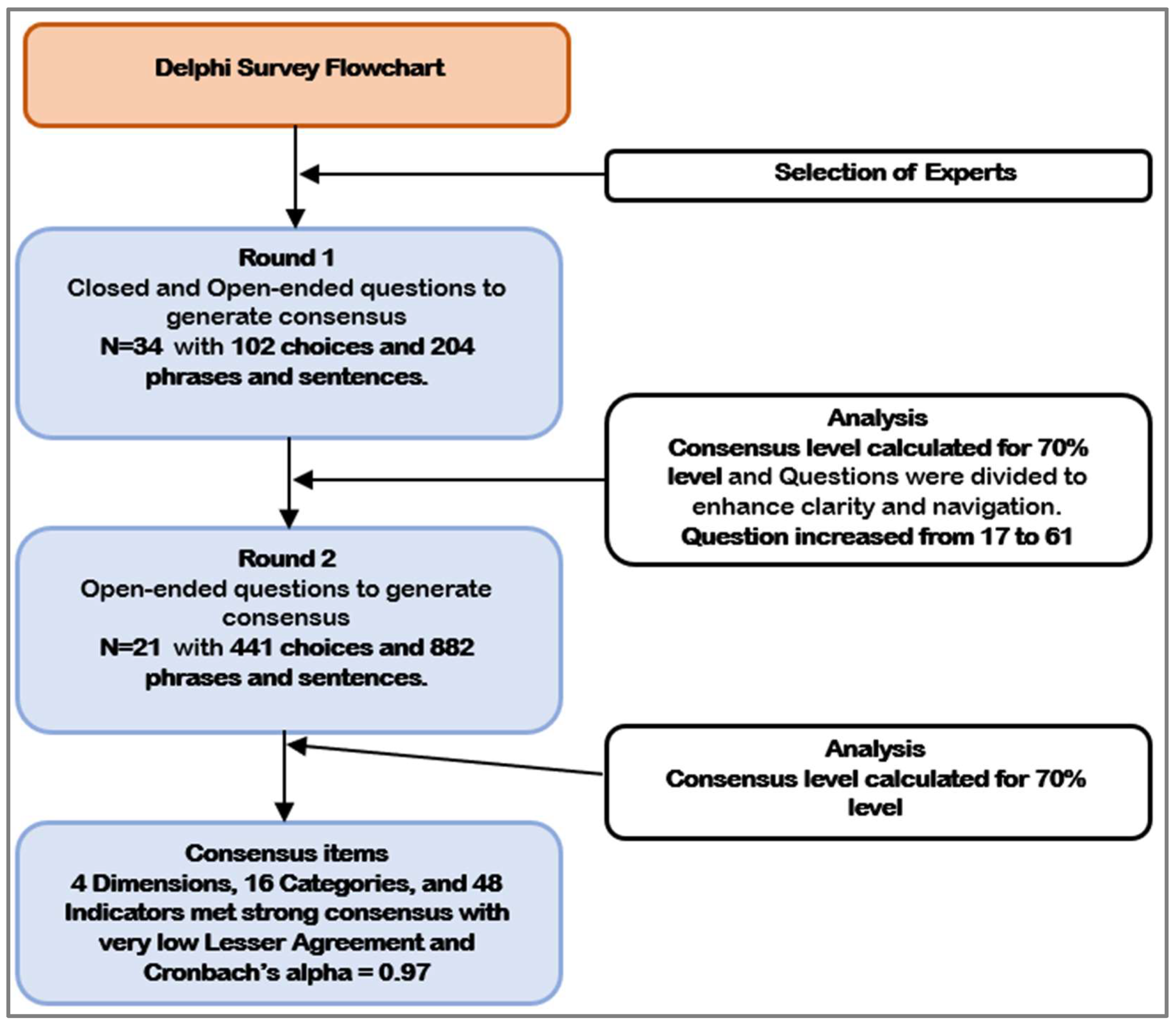

2. Research Design

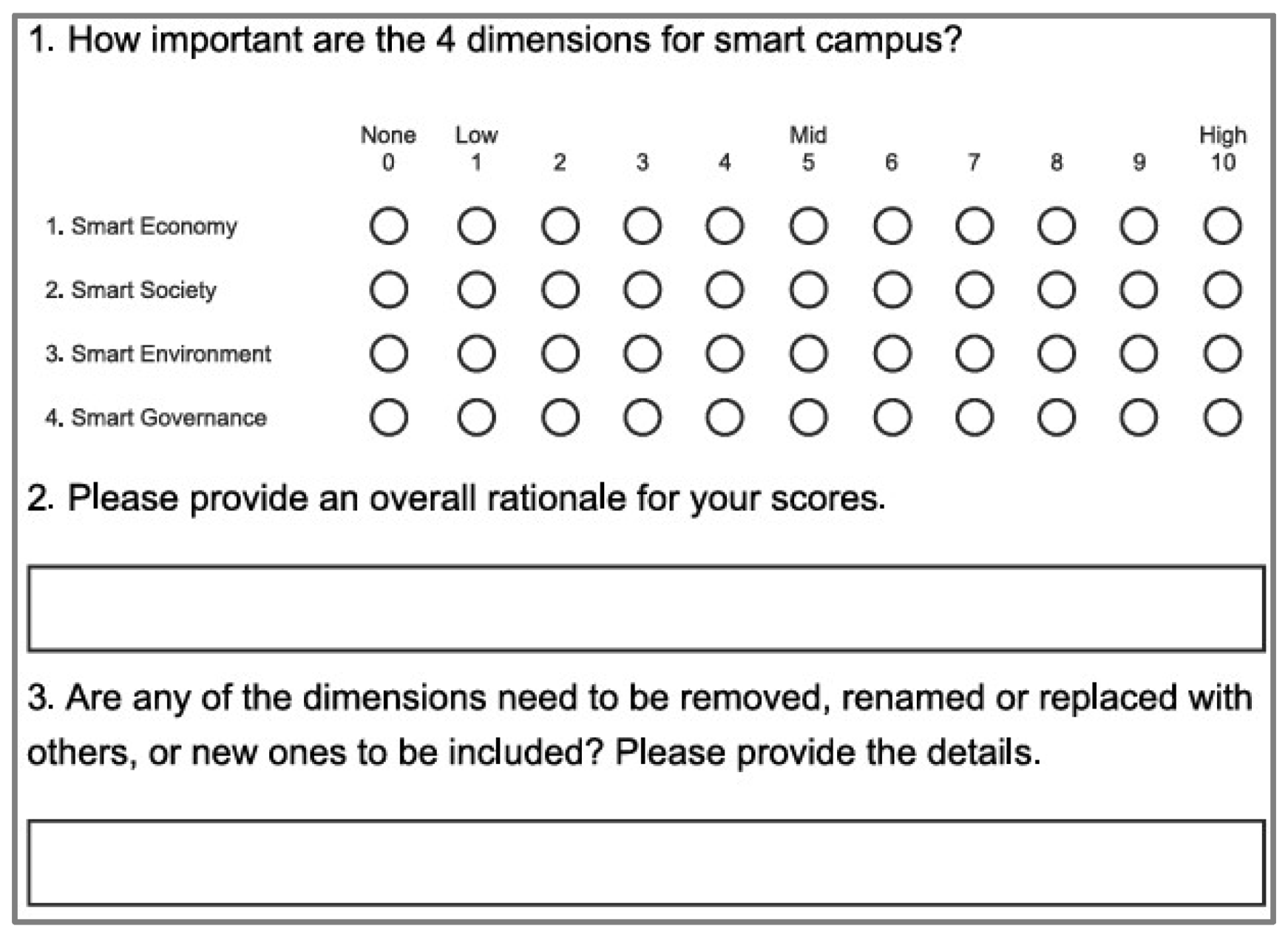

2.1. Survey Questionnaire

2.2. Delphi Study

2.3. Delphi Rounds

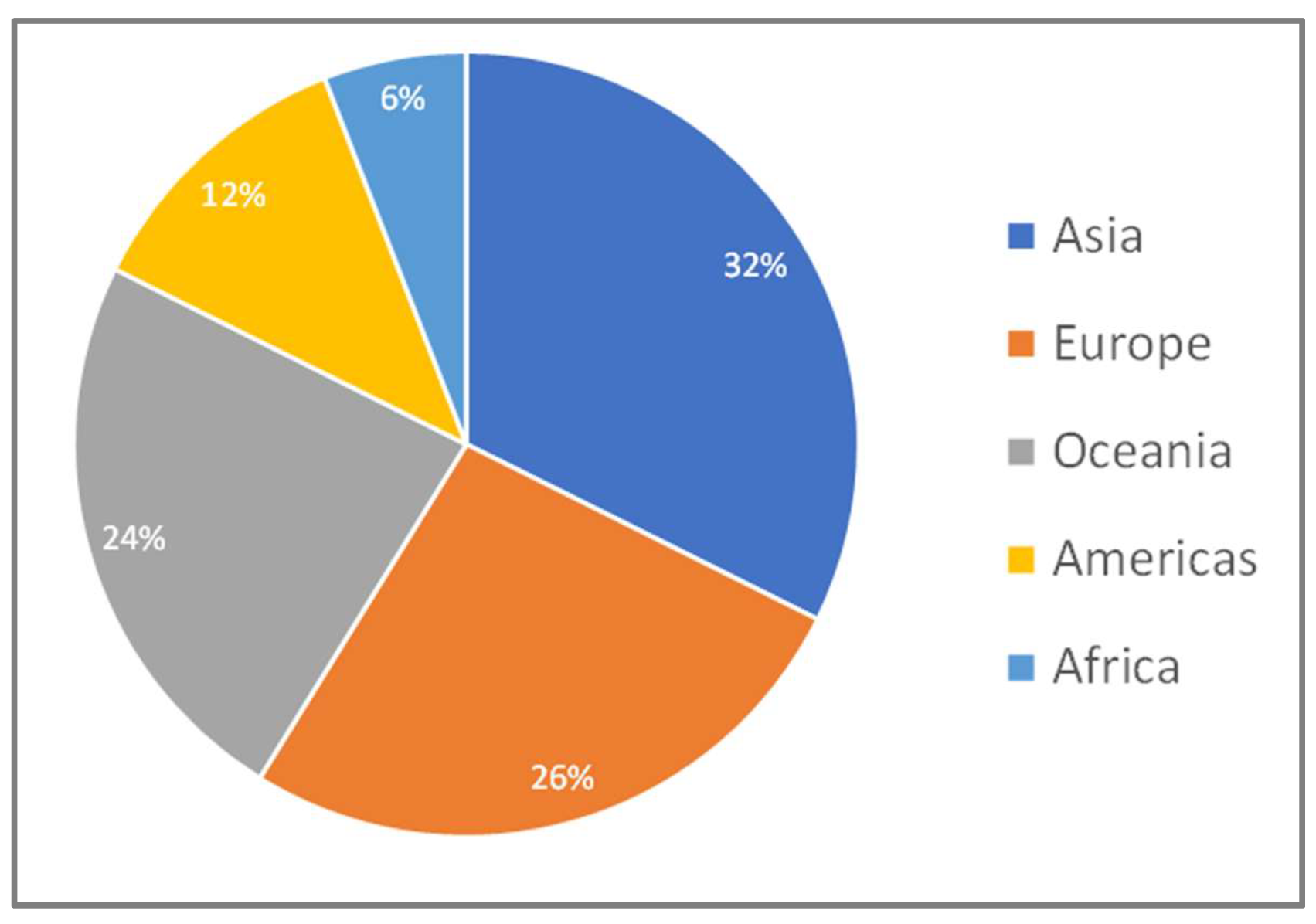

2.4. Selection of Experts from Relevant Journals and Organizations

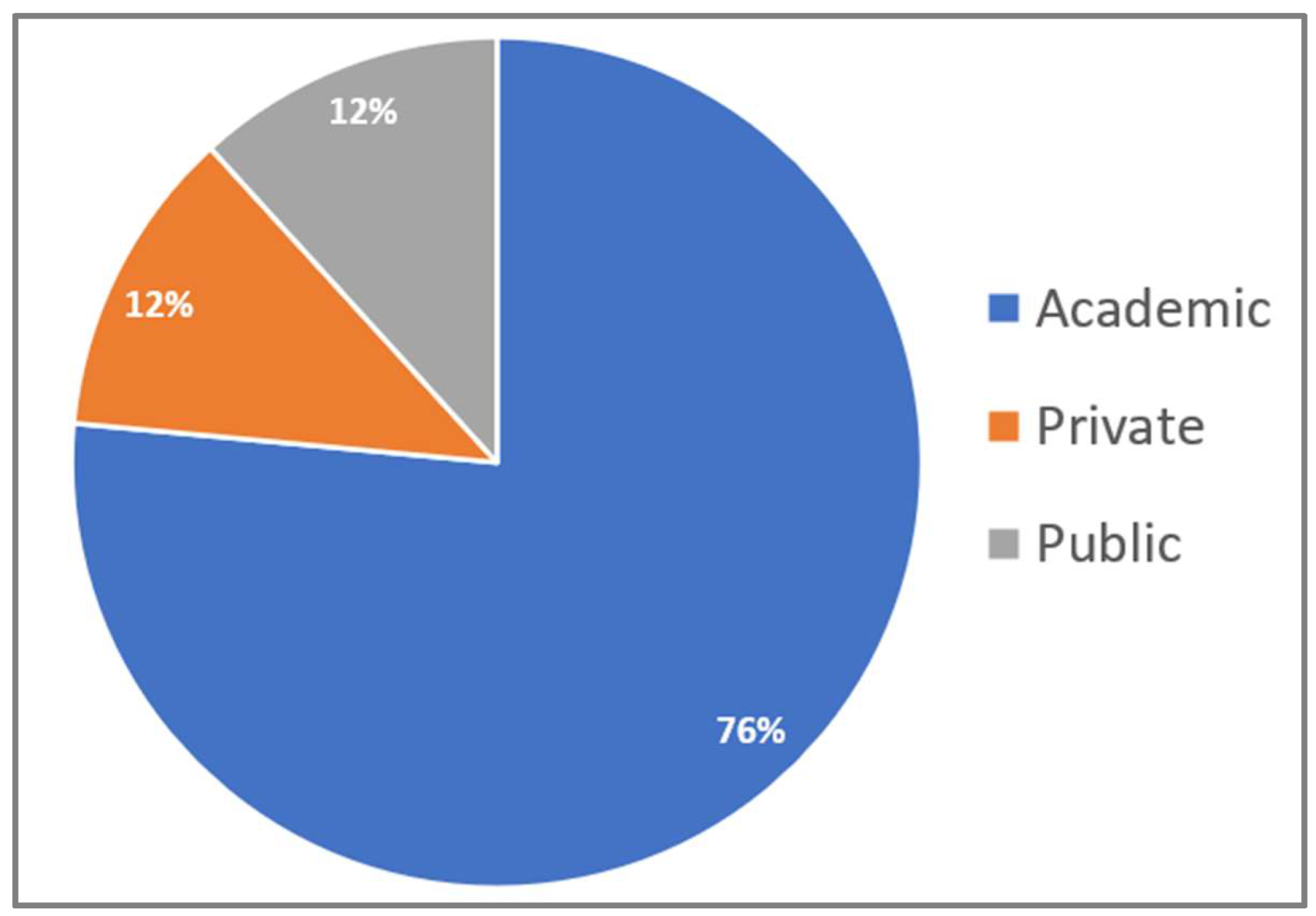

2.5. Delphi Participants

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Analysis and Results

3.1. Round 1 Results

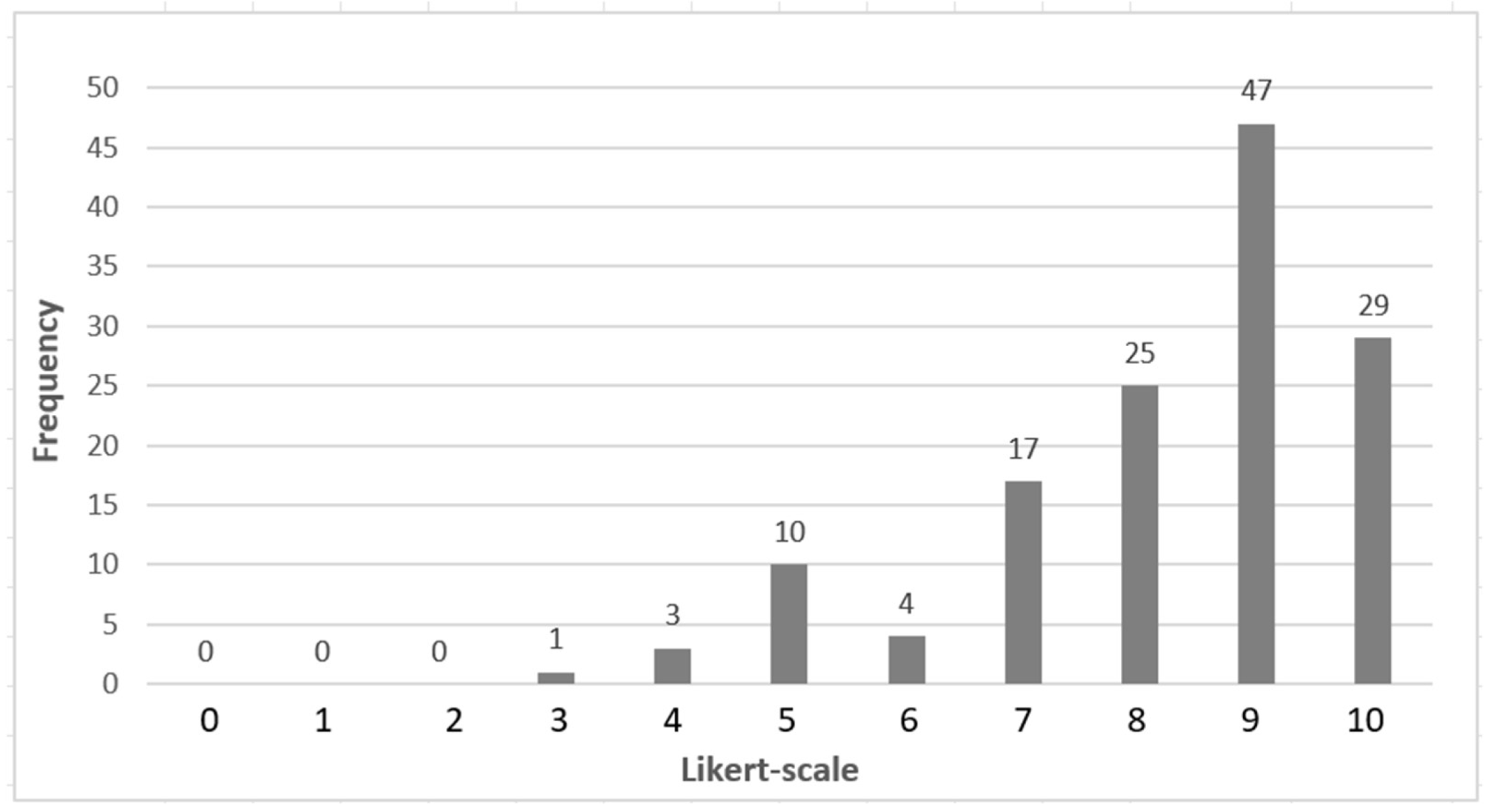

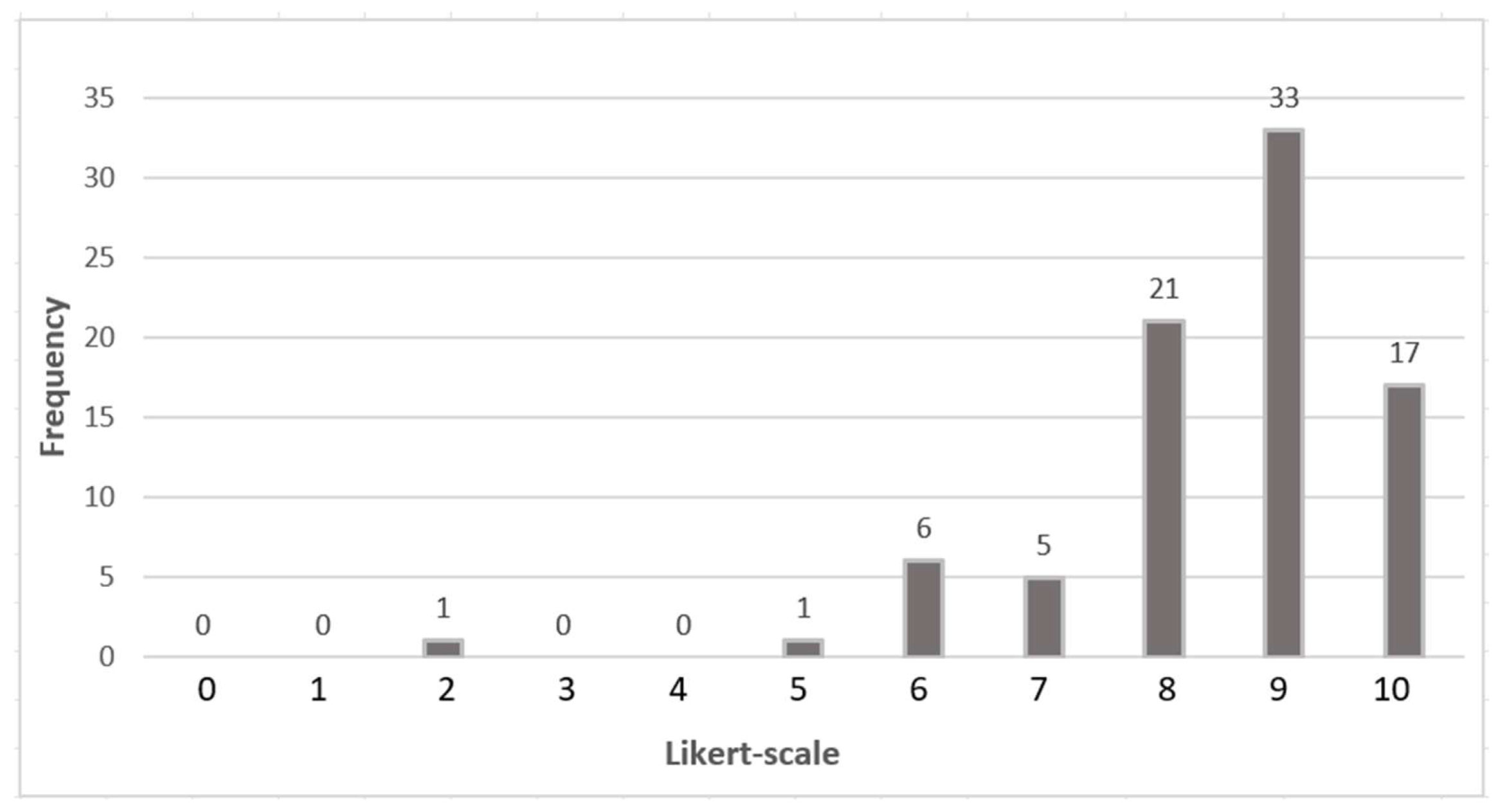

3.1.1. Responses to Dimensions

3.1.2. Responses to Categories

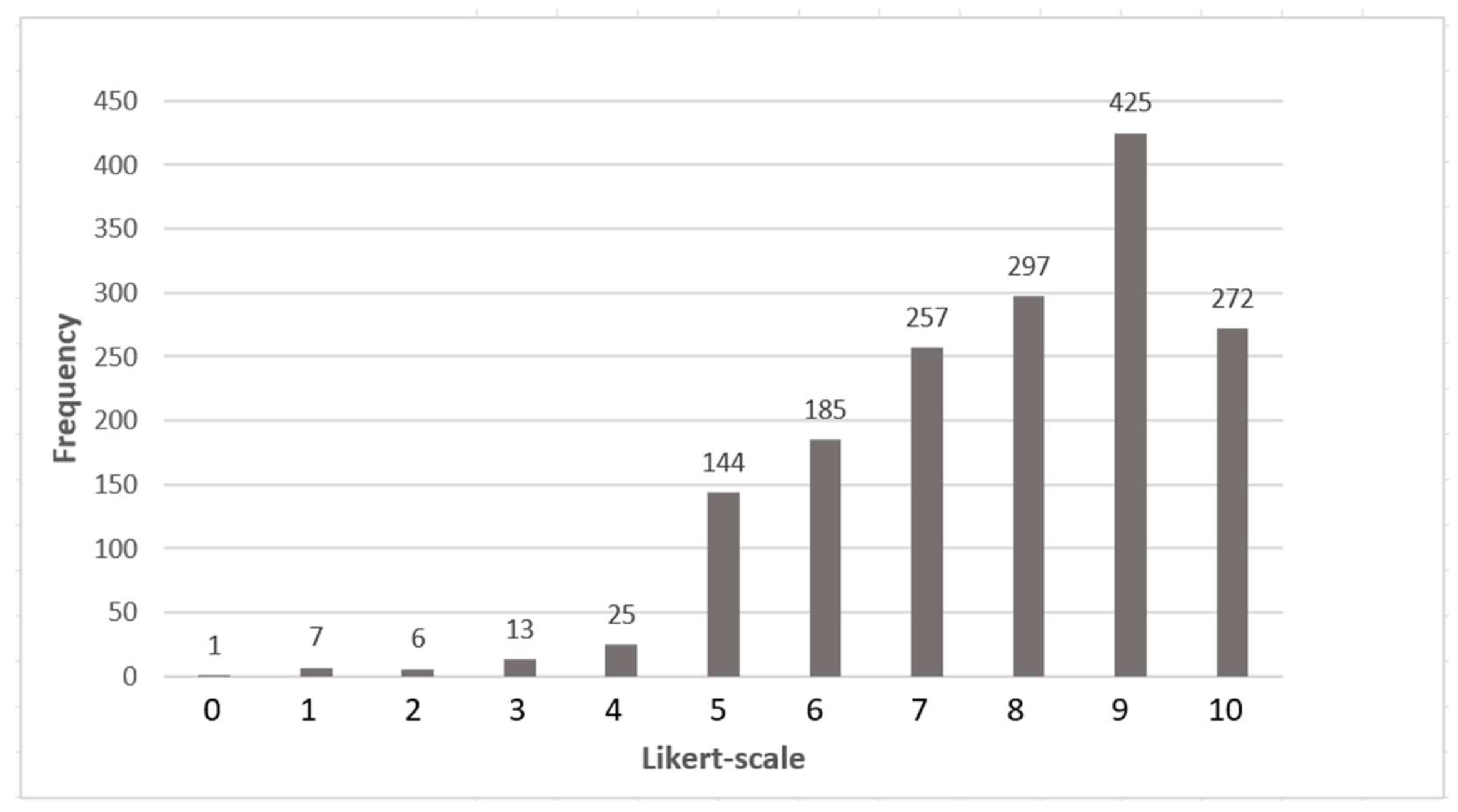

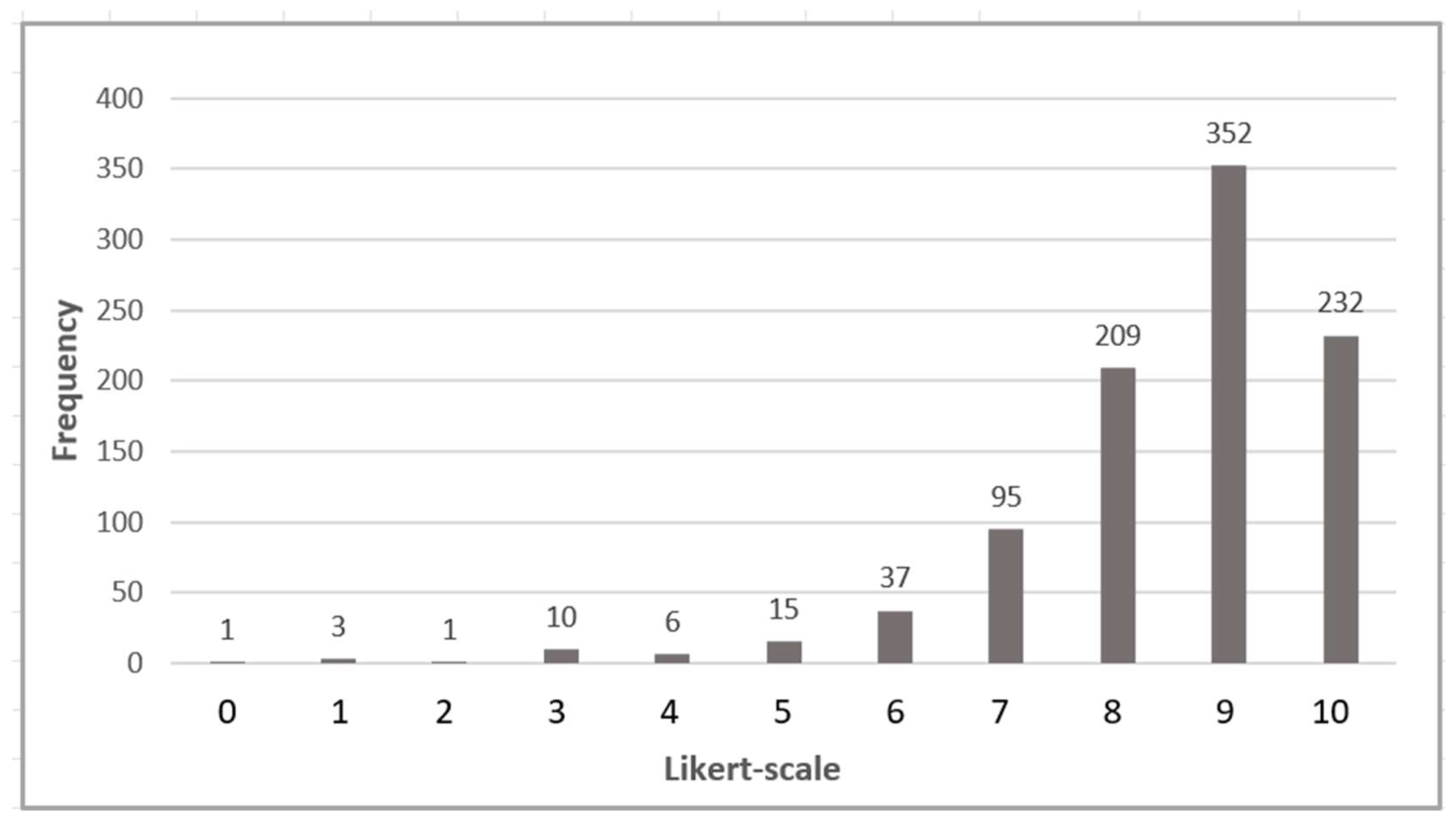

3.1.3. Responses to Indicators

3.1.4. Overall Responses

3.2. Round 2

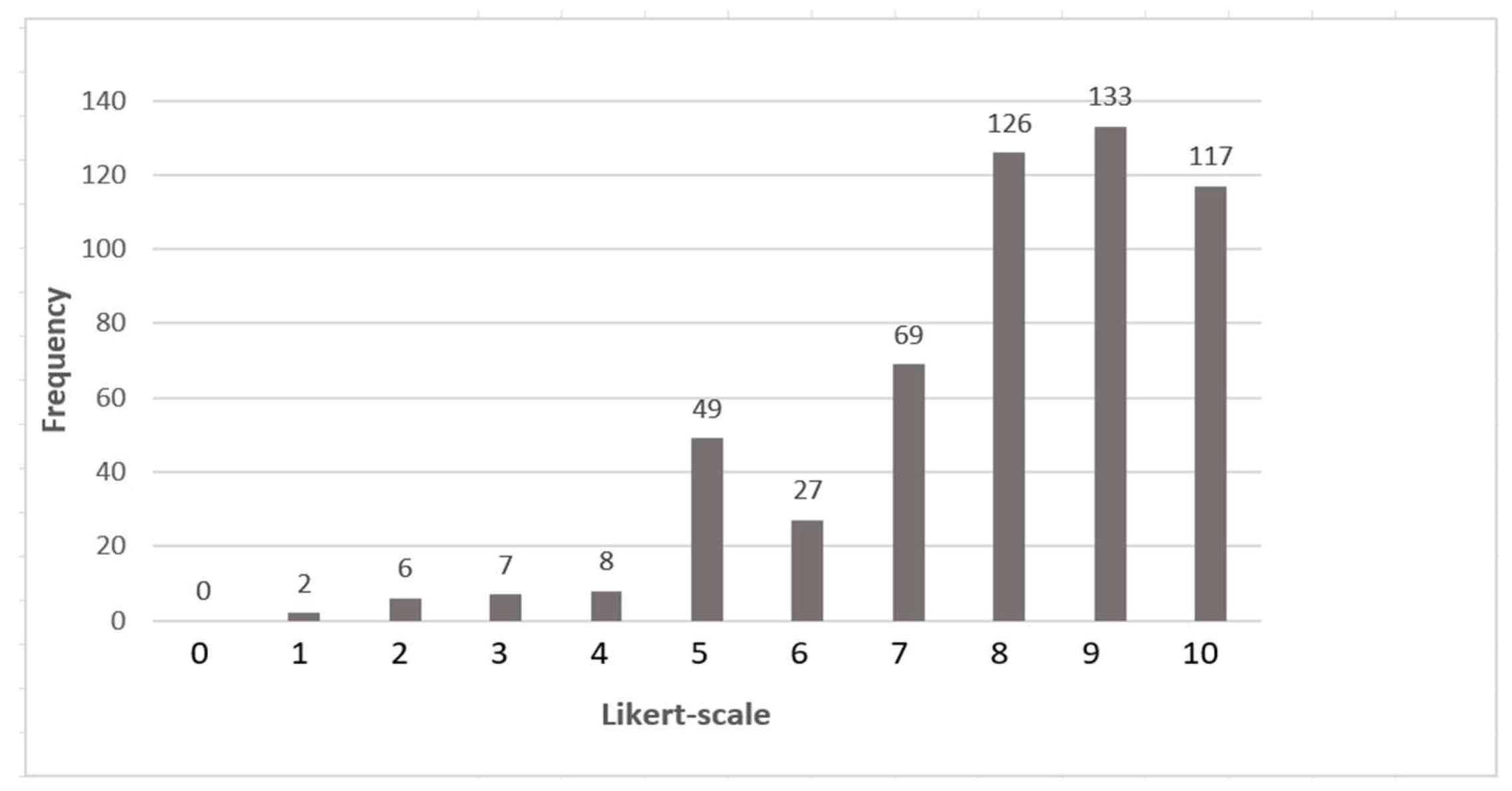

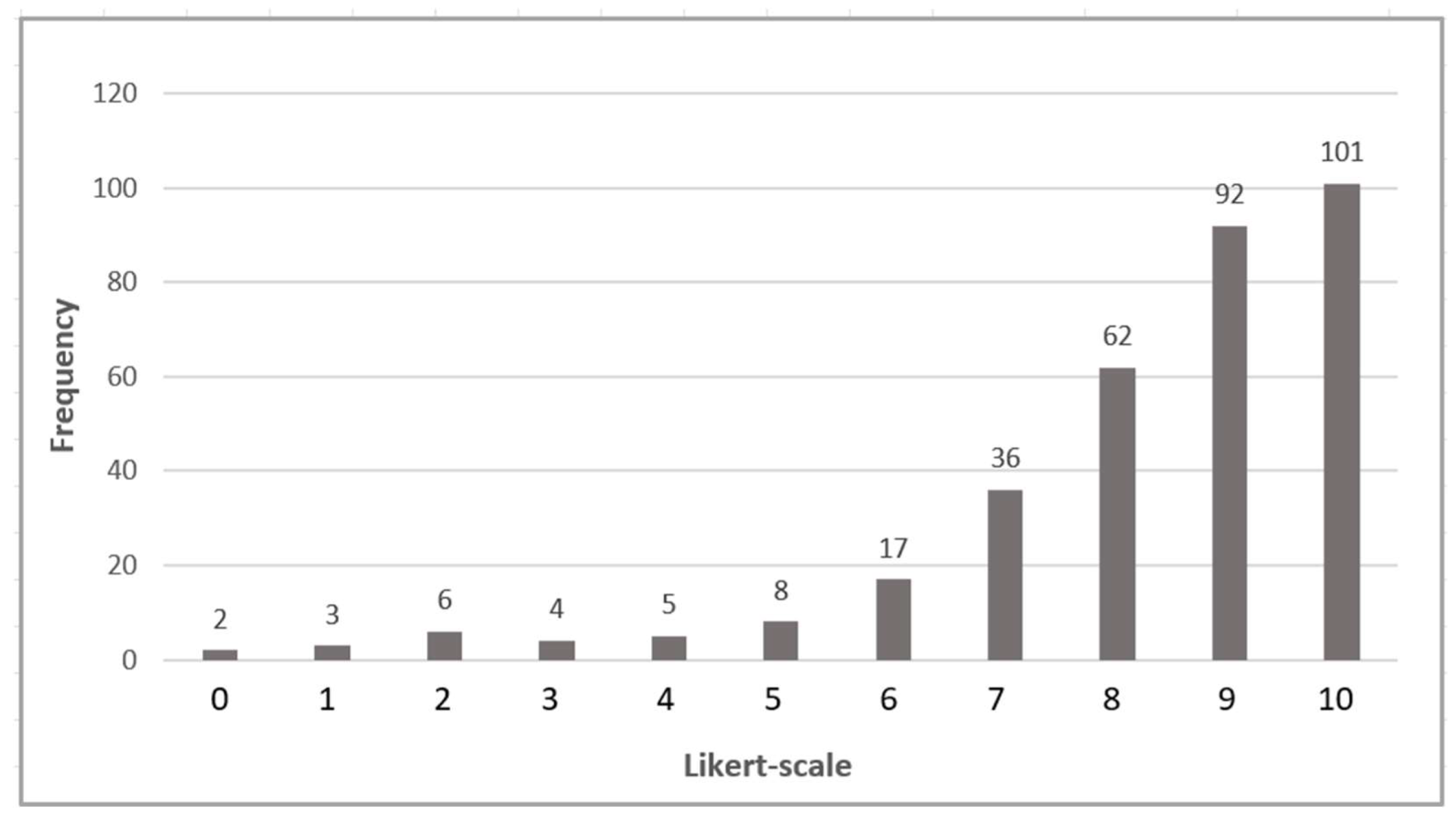

3.2.1. Responses to Dimensions

3.2.2. Responses to Categories

3.2.3. Responses to Indicator

3.2.4. Overall Responses

3.3. Response Rate

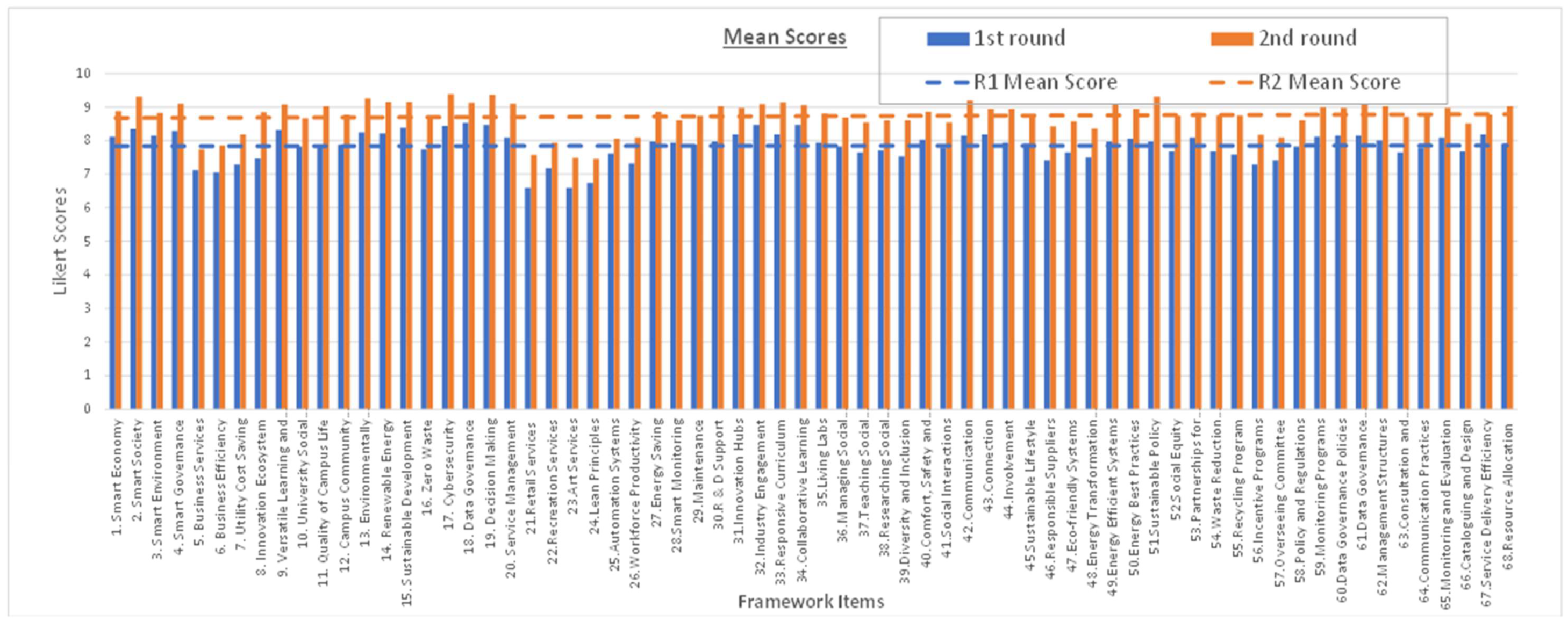

3.4. Statistical Analysis Parameters

- ▪

- A’ (Agree): scales 6,7;

- ▪

- ‘SA’ (Strongly Agree): scales 8, 9, and 10;

- ▪

- ‘OA’ (Overall Agreement): A + SA (must be >70% for consensus);

- ▪

- Standard deviation: less than 2.0.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Delphi Study Overview

4.2. Research Limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, L.; Tang, Q. Construction of a Six-Pronge Intelligent Physical Education Classroom Model in Colleges and Universities, Scientific Programming, 2022, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yip, C.; Swift, S.; Beswick, K. Smart campus: Definition, framework, technologies, and services. IET Smart Cities 2020, 2, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shoqran,M.; Shorman,S. A Review on smart universities and artificial intelligence. In The fourth industrial revolution: implementation of artificial intelligence for growing business success studies in computational intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021.

- Pagliaro, F.; Mattoni, B.; Gugliermenti, F.; Bisegna, F.; Azzaro, B.; Tomei, F.; Catucci, S. A roadmap toward the development of Sapienza Smart Campus. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering (EEEIC), Florence, Italy, (7–10 June 2016).

- Aion, N.; Helmandollar, L.; Wang, M.; Ng, J. Intelligent campus (iCampus) impact study. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/WIC/ACMInternational Conferences on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology, Macau, China, (4–7 December 2012); pp. 291–295.

- Luckyardi, S.; Jurriyati, R.; Disman, D.; Dirgantari, P.D. A Systematic Review of the IoT in Smart University: Model and Contribution. In J Sci Tech 2022, 7, 529–550. [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, D.; Sensuse, D. Knowledge Management Model for Smart Campus in Indonesia. Data 2022, 7, 7. [CrossRef]

- Horvath, D.; Csordas, T.; Ásvanyi, K.; Faludi, J.; Cosovan, A.; Simay, A.; Komar, Z. Will Interfaces Take Over the Physical Workplace in Higher Education? A Pessimistic View of the Future. JCRE 2021, 24, 108–123. [CrossRef]

- Zaballos, A.; Briones, A.; Massa, A.; Centelles, P.; Caballero, V. A Smart Campus’ Digital Twin for Sustainable Comfort Monitoring. Sust 2020, 12, 9196. [CrossRef]

- Imbar, R.; Supangkat, S.; Langi, A. Smart Campus Model: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), IEEE, New York, NY, USA, (19–20 November 2020); pp. 1–7.

- Huertas J.; Mahlknecht J.; Lozoya-Santos J.; Uribe S.; López-Guajardo E.; Ramirez-Mendoza R. Campus City Project: Challenge Living Lab for Smart Cities Living Lab for Smart Cities; Ap Sc. 2021, 11, 23.

- Qureshi M., Khan N.; Bahru J.; Ismail F. Digital Technologies in Education 4.0. Does it Enhance the Effectiveness of Learning? A Systematic Literature Review; Int J Int Mob Tech, 2021, 15(4), 31-47.

- Zhang, Y. Challenges and Strategies of Student Management in Universities in the Context of Big Data. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu Y. Research and Construction of University Data Governance Platform Based on Smart Campus Environment. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Advanced Manufacture, Manchester, UK, (23–25 October, 2021); pp. 450–455.

- Min-Allah, N.; Alrashed, S. Smart Campus—A Sketch. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 1–15.

- Polin, K.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Limb. M.; & Washington, T. The making of smart campus: a review and conceptual framework, Build, 2023, 13, 891. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Degirmenci, K.; Butler, L.; Desouza, K. What are the key factors affecting smart city transformation readiness? Evidence from Australian cities. Cities. 2022, 120, 103434. [CrossRef]

- Awuzie B.; Ngowi A.; Omotayo T.; Obi L.; Akotia J. Facilitating Successful Smart Campus Transitions: A Systems Thinking-SWOT Analysis Approach; Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 2044.

- Polin, K.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Washington, T.; Limb, M. Unpacking smart campus assessment: developing a framework via narrative literature review. Sustainability. 2024, 16, 2494. 10.3390/su16062494.

- AbuAlnaaj, K.; Ahmed, V.; Saboor, S. A strategic framework for smart campus. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, (10–12 March 2020); Volume 22, pp. 790–798.

- Landeta, J. Elmetodo Delphi. Unatecnica de prevision de la incertidumbre. Barcelona: Editorial Ariel, S.; 1999.

- Silverman, D. Qualitative Research. London, UK: Sage; 2016.

- Avella, J. 2016, ‘Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges’, In. J. Doc Stud; 2016, 11(1), 305–321.

- Hasson, F.; Keeney, S.; McKenna, H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000; 32 (4): 1008 1015. [CrossRef]

- Vernon, W. The Delphi technique: A review, I J The Reh; 2009, 16(2), pp. 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Young, S.; Jamieson, L., Delivery methodology of the Delphi: A comparison of two approaches’, J Pa & Rec Ad. 2001, 19(1), 42–58.

- Shah K.; Naidoo K.; Loughman J. Development of socially responsive competency frameworks for ophthalmic technicians and optometrists in Mozambique. Clin Exp Optom. 2016; 99 (2), 173-182. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, I.; Grant, R.; Feldman, B.; Pencharz, P.; Ling, S., Moore, A.; Wales, P. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epid; 2014, 67(4), 401,409. [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilpoorarabi, N.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M.; Kamruzzaman, M. Does place quality matter for innovation districts? Determining the essential place characteristics from Brisbane’s knowledge precincts. Land Use Pol. 2018, 79, 734-747. [CrossRef]

- McVie, R. A Methodology for Identifying Typologies to Improve Innovation District Outcomes: The case of South East Queensland, Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Queensland University of Technology, Australia, 2023.

- . [CrossRef]

- Brady, S. Utilizing and adapting the Delphi method for use in qualitative research. I J Qual Met, 2015, 14(5), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hanafin, S. Review on literature on the Delphi technique. Department of Children and Youth Affairs, Ireland. (2004). https://www.dcya.gov.ie/documents/publications/Delphi_Technique_A_Literature_Review.pdf.

- Ludwig, B. Predicting the future: Have you considered using the Delphi methodology? J Ext, 1997. 35(5).

- Schmiedel, T.; Vom Brocke, J.; Recker, J. Which cultural values matter to business process management? Results from a global Delphi study. Bus Pro Man J, 2013, 19(2), 292-317.

- Zeeman, H.; Wright, C.; Hellyer, T. (2016). Developing design guidelines for inclusive housing: a multi- stakeholder approach using a Delphi method. Journal of Housing and Built Environment, 2016, 31(4), 761-772. [CrossRef]

- Yigitcanlar, T.; Dur, F. Making space and place for knowledge communities: lessons for Australian practice. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 2013, 19(1), 36-63.

- Metaxiotis, K.; Carrillo, J.; Yigitcanlar, T. Knowledge-based development for cities and societies: integrated multi-level approaches. IGI Global, Hersey, PA, USA, 2010.

- Baum, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Horton, S.; Velibeyoglu, K, Gleeson, B. The role of community and lifestyle in the making of a knowledge city. Griffith University, Brisbane. 2007.

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Place making for innovation and knowledge-intensive activities: the Australian experience. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2019, 146, 616-625. [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Category | Indicator | Description | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smart economy | Business services | Retail services | Quantity and quality of food, retail, and other business services | A variety of food, retail and other business services on campus with opening hours during peak periods and to the public during off peak and weekends. |

| Recreation services | Quantity and quality of sports and recreation services | A variety of sports and recreation services on campus with opening hours during peak periods and to the public during off peak and weekends. | ||

| Art services | Quantity and quality of art galleries and performance services | A variety of art galleries and performance services on campus with opening hours during peak periods and to the public during off peak and weekends. | ||

| Business efficiency | Lean principles | Effective practice of lean principles | Improvement of workplace efficiency for value creation in business on campus. | |

| Automation systems | Effectiveness of collaborative automation systems | The robust automation system in business on campus. | ||

| Workforce productivity | Level of workforce productivity | The output of workforce activity in business on campus. | ||

| Utility cost saving | Energy saving | Effectiveness of energy saving mechanisms | The robustness of energy saving mechanisms on campus. | |

| Smart monitoring | Effectiveness of smart monitoring and control mechanisms | The robustness of smart monitoring and control mechanisms on campus. | ||

| Maintenance | Level of appropriate maintenance and service upgrade | The adequate maintenance and service upgrade of campus facilities to reduce cost. | ||

| Innovation ecosystem | R&D support | Level of incentives and support for R&D | Having an R&D promotion culture of incentives and adequate support. | |

| Innovation hubs | Effectiveness of incubators and accelerators | Provision of incubators and accelerators for innovation on campus. | ||

| Industry engagement | Level of industry engagement and partnership | The extent of industry engagement and participation in innovation. | ||

| Smart society | Versatile learning and research | Responsive curriculum | Successful adoption of responsive curriculum | Having curriculum meeting changes in the market and employment sector. |

| Collaborative learning | Offering of operational collaborative teaching and learning resources | Having robust teaching and learning resources. | ||

| Living labs | Effectiveness of Living labs for knowledge sharing | Having robust Living Labs for knowledge sharing. | ||

| University social responsibility | Managing social responsibility | Effective management of the social responsibility agenda | The resilient leadership and successful implementation of the social responsibility agenda | |

| Teaching social responsibility | Effective integration of social responsibility into teaching | The success in integrating social responsibility into teaching. | ||

| Researching social responsibility | Effective integration of social responsibility into research and projects | The success in integrating social responsibility into research and projects. | ||

| Quality of campus life | Diversity and inclusion | Practice of diversity and inclusion | Presence of a culture of diversity and inclusion on campus. | |

| Comfort, safety and security | Presence of comfort, safety and security | Having a comfort, safe and secure campus community. | ||

| Social interactions | Presence of vibrant social interactions | Promotion of vibrant social interactions on campus. | ||

| Campus community engagement | Communication | Effective communication channels | Means of enabling communication on campus. | |

| Connection | Level of connectedness among the campus community | The campus community getting connected together through some means. | ||

| Involvement | Level of socially involved members of the campus community | Members of the campus community getting involved along their social identities. | ||

| Smart environment | Environmentally friendly services | Sustainable lifestyle | Level of sustainable lifestyle on campus | The livelihood of campus residents which harmonises with the natural environment. |

| Responsible suppliers | Level of engagement with environmentally responsible suppliers | Suppliers of goods and services to the university conforming to environmental sustainability agenda. | ||

| Eco-friendly initiatives | Level of development and practice of eco-friendly initiatives | Eco-friendly development and practice endeavours. | ||

| Renewable energy | Energy transformation culture | Effectiveness of energy transformation culture | Shift towards positive changes in campus energy. | |

| Energy efficiency systems | Effectiveness of energy efficiency system utilisation | Implementation of systems to improve energy efficiency. | ||

| Energy best practices | Level of good practices in renewable energy use, generation, and storage | Promotion of good practices in renewable energy use, generation, and storage | ||

| Sustainable development | Sustainability policy | Effectiveness of environmental sustainability policy | Successful implementation of environmental sustainability policies. | |

| Social equity | Effective practice of social equity | Campus citizens’ sense of responsibility in sustainable development. | ||

| Partnerships for sustainability | Effective practice of building partnerships for sustainability | Identifying and engaging parties of common interest in sustainability. | ||

| Zero waste | Waste reduction programs | Effective utilisation of waste reduction programs | Promotion of initiatives to reduce waste in the overall operation of the university. | |

| Recycling program | Effective utilisation of recycling programs | Promotion of reusing used materials and goods to sustain the operations of the university. | ||

| Incentive programs | Effective establishment and practice of incentive programs | Implementation of incentive programs to promote zero waste. | ||

| Smart governance | Cybersecurity | Overseeing committee | Effectiveness of the cybersecurity committee | Establishment of a select group of people to be responsible for cybersecurity. |

| Policy and regulations | Effective cybersecurity policy and regulations | Establishment of overall guidelines and rules for cybersecurity implementation. | ||

| Monitoring programs | Effective monitoring programs for follow-ups | Establishment of means for checking and following up the implementation of cybersecurity. | ||

| Data governance | Data governance policies | Effectiveness of data governance policies | Establishment of overall guidelines for the use of data in governance. | |

| Data governance processes | Effectiveness of data governance processes | Establishment of means to deal with data for governance. | ||

| Management structures | Effectiveness of data governance management structures | Establishment of levels of power and authority to control use of data in governance. | ||

| Decision-making | Consultation and collaboration | Effective consultation and collaboration | A wide inquisitive and interactive campus community. | |

| Communication practices | Effective communication practices | Presence of robust communication avenues throughout the campus community. | ||

| Monitoring and evaluation | Effective monitoring and evaluation mechanisms | The consistent checking and evaluation of campus operations. | ||

| Service management | Cataloguing and design | Effectiveness of cataloguing and design | Constant updating of product and services stock and meeting campus stakeholders needs. | |

| Service delivery efficiency | Effectiveness of service delivery efficiency | Means of providing services to campus stakeholders when needed. | ||

| Resource allocation | Effectiveness of resource allocation | Resource distribution reaching all the campus community as required. |

| Academic | Public | Private | Average Professional Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

19 years |

|

| (N=34) | Likert scale | Mean | Std Dev | Var | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1. Smart Economy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 8.12 | 1.79 | 3.20 |

| 2. Smart Society | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 8.35 | 1.30 | 1.69 |

| 3. Smart Environment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 8.15 | 1.73 | 2.98 |

| 4. Smart Governance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 8 | 8.29 | 1.64 | 2.70 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha = | 0.81 | |||||||||||||

| (N=34) | Likert scale | Mean | Std Dev | Var | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1. Business Services | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 7.12 | 1.93 | 3.74 |

| 2. Business Efficiency | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7.06 | 1.94 | 3.75 |

| 3. Utility Cost Saving | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 3 | 7.29 | 1.99 | 3.97 |

| 4. Innovation Ecosystem | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 11 | 6 | 7.47 | 2.79 | 7.77 |

| 5. Versatile Learning and Research | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 8.32 | 1.61 | 2.59 |

| 6. University Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7.82 | 1.98 | 3.91 |

| 7. Quality of Campus Life | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 10 | 7.88 | 2.13 | 4.53 |

| 8. Campus Community Engagement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 7.88 | 1.63 | 2.65 |

| 9. Environmentally Friendly Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 14 | 5 | 7.88 | 1.63 | 2.65 |

| 10. Renewable Energy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 8 | 8.21 | 1.67 | 2.77 |

| 11. Sustainable Development | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 8.38 | 1.52 | 2.30 |

| 12. Zero Waste | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 7.74 | 2.15 | 4.62 |

| 13. Cybersecurity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 12 | 8.44 | 1.69 | 2.86 |

| 14. Data Governance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 14 | 8.53 | 1.62 | 2.62 |

| 15. Decision Making | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 8.47 | 1.48 | 2.20 |

| 16. Service Management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 8.09 | 1.75 | 3.05 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha = | 0.90 | |||||||||||||

| (N=34) | Likert scale | Mean | Std Dev | Var | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1. Retail Services | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 6.59 | 2.18 | 4.73 |

| 2. Recreation Services | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 7.18 | 1.77 | 3.12 |

| 3. Art Services | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 6.59 | 1.94 | 3.76 |

| 4. Lean Principles | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 6.74 | 1.96 | 3.84 |

| 5. Automation Systems | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 7.62 | 1.89 | 3.58 |

| 6. Workforce Productivity | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 7.32 | 2.10 | 4.41 |

| 7. Energy Saving | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 7.97 | 1.71 | 2.94 |

| 8. Smart Monitoring | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 11 | 7 | 7.94 | 1.94 | 3.75 |

| 9. Maintenance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 7.88 | 1.51 | 2.29 |

| 10. R&D Support | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 11 | 5 | 7.97 | 1.70 | 2.88 |

| 11. Innovation Hubs | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 15 | 6 | 8.18 | 1.83 | 3.36 |

| 12. Industry Engagement | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 16 | 7 | 8.47 | 1.76 | 3.11 |

| 13. Responsive Curriculum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 8.18 | 1.73 | 3.00 |

| 14. Collaborative Learning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 8.47 | 1.35 | 1.83 |

| 15. Living Labs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 7.94 | 1.46 | 2.12 |

| 16. Managing Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7.82 | 1.57 | 2.45 |

| 17. Teaching Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 7.65 | 1.81 | 3.27 |

| 18. Researching Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 7.71 | 1.62 | 2.64 |

| 19. Diversity and Inclusion | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 7.53 | 2.15 | 4.62 |

| 20. Comfort, Safety and Security | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 8.03 | 1.83 | 3.36 |

| 21. Social Interactions | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 7.79 | 1.87 | 3.50 |

| 22. Communication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 9 | 8.15 | 1.64 | 2.67 |

| 23. Connection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 8.18 | 1.66 | 2.76 |

| 24. Involvement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 7.94 | 1.63 | 2.66 |

| 25. Sustainable Lifestyle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 7.91 | 1.50 | 2.26 |

| 26. Responsible Suppliers | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 7.41 | 1.78 | 3.16 |

| 27. Eco-friendly Systems | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 7.65 | 1.59 | 2.54 |

| 28. Energy Transformation Culture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 7.50 | 1.78 | 3.17 |

| 29. Energy Efficient Systems | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 7.97 | 1.68 | 2.82 |

| 30. Energy Best Practices | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 8.06 | 1.59 | 2.54 |

| 31. Sustainable Policy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7.97 | 1.75 | 3.06 |

| 32. Social Equity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 7.68 | 1.61 | 2.59 |

| 33. Partnerships for Sustainability | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 8.09 | 1.60 | 2.57 |

| 34. Waste Reduction Programs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7.68 | 1.89 | 3.56 |

| 35. Recycling Program | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7.59 | 1.84 | 3.40 |

| 36. Incentive Programs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 7.29 | 1.70 | 2.88 |

| 37. Overseeing Committee | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 7.41 | 1.78 | 3.16 |

| 38. Policy and Regulations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 7.82 | 1.85 | 3.42 |

| 39. Monitoring Programs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 13 | 8 | 8.12 | 1.85 | 3.44 |

| 40. Data Governance Policies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 11 | 9 | 8.15 | 1.78 | 3.16 |

| 41. Data Governance Processes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 8.15 | 1.78 | 3.16 |

| 42. Management Structures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 8.00 | 1.84 | 3.39 |

| 43. Consultation and Collaboration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 7.65 | 1.72 | 2.96 |

| 44. Communication Practices | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 4 | 7.79 | 1.53 | 2.35 |

| 45. Monitoring and Evaluation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 13 | 6 | 8.09 | 1.71 | 2.93 |

| 46. Cataloguing and Design | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 4 | 7.68 | 1.74 | 3.01 |

| 47. Service Delivery Efficiency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 8.18 | 1.45 | 2.09 |

| 48. Resource Allocation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 8 | 7.91 | 1.86 | 3.48 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha = | 1 | |||||||||||||

| N=21 | Likert scale | Mean | Std Dev | Var | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1. Smart Economy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 8.24 | 1.81 | 3.29 |

| 2. Smart Society | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 8.71 | 1.10 | 1.21 |

| 3. Smart Environment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 8.52 | 1.17 | 1.36 |

| 4. Smart Governance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 8.90 | 0.83 | 0.69 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha = | 0.76 | |||||||||||||

| N=21 | Likert scale | Mean | Std Dev | Var | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1. Business Services | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 7.71 | 1.87 | 3.51 |

| 2. Business Efficiency | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 7.29 | 2.55 | 6.51 |

| 3. Utility Cost Saving | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 7.48 | 2.64 | 6.96 |

| 4. Innovation Ecosystem | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 8.76 | 1.92 | 3.69 |

| 5. Versatile Learning and Research | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8.48 | 1.78 | 3.16 |

| 6. University Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 7.57 | 2.11 | 4.46 |

| 7. Quality of Campus Life | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 8.33 | 1.62 | 2.63 |

| 8. Campus Community Engagement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 8.33 | 1.62 | 2.63 |

| 9. Environmentally Friendly Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 8.19 | 1.36 | 1.86 |

| 10. Renewable Energy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 8.14 | 1.96 | 3.83 |

| 11. Sustainable Development | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8.14 | 2.33 | 5.43 |

| 12. Zero Waste | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 8.05 | 2.09 | 4.35 |

| 13. Cybersecurity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 10 | 8.76 | 1.95 | 3.79 |

| 14. Data Governance | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 8.76 | 2.12 | 4.49 |

| 15. Decision Making | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 8 | 9.29 | 0.72 | 0.51 |

| 16. Service Management | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 8.86 | 1.59 | 2.53 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha = | 0.94 | |||||||||||||

| N=21 | Likert scale | Mean | Std Dev | Var | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1. Retail Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 7.86 | 1.68 | 2.83 |

| 2. Recreation Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 8.29 | 1.59 | 2.51 |

| 3. Art Services | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 7.86 | 1.71 | 2.93 |

| 4. Lean Principles | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 7.90 | 2.10 | 4.39 |

| 5. Automation Systems | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 8.25 | 2.00 | 3.99 |

| 6. Workforce Productivity | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 11 | 2 | 7.95 | 2.13 | 4.55 |

| 7. Energy Saving | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 8.52 | 1.50 | 2.26 |

| 8. Smart Monitoring | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8.48 | 1.69 | 2.86 |

| 9. Maintenance | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 8.76 | 1.18 | 1.39 |

| 10. R D Support | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 8.52 | 1.50 | 2.26 |

| 11. Innovation Hubs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8.81 | 1.57 | 2.46 |

| 12. Industry Engagement | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 8.86 | 1.71 | 2.93 |

| 13. Responsive Curriculum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 8.48 | 1.60 | 2.56 |

| 14. Collaborative Learning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 8.95 | 1.02 | 1.05 |

| 15. Living Labs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 8.71 | 0.90 | 0.81 |

| 16. Managing Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 7.90 | 1.61 | 2.59 |

| 17. Teaching Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 7.95 | 1.86 | 3.45 |

| 18. Researching Social Responsibility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 7.90 | 1.84 | 3.39 |

| 19. Diversity and Inclusion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 8.10 | 2.10 | 4.39 |

| 20. Comfort, Safety and Security | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8.67 | 1.65 | 2.73 |

| 21. Social Interactions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8.48 | 1.78 | 3.16 |

| 22. Communication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 8.52 | 1.12 | 1.26 |

| 23. Connection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 8.24 | 1.37 | 1.89 |

| 24. Involvement | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 7 | 8.43 | 1.43 | 2.06 |

| 25. Sustainable Lifestyle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 8.43 | 1.21 | 1.46 |

| 26. Responsible Suppliers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 8.81 | 1.08 | 1.16 |

| 27. Eco-friendly Systems | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8.48 | 1.40 | 1.96 |

| 28. Energy Transformation Culture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8.52 | 1.44 | 2.06 |

| 29. Energy Efficient Systems | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 8.29 | 1.95 | 3.81 |

| 30. Energy Best Practices | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 8.71 | 0.96 | 0.91 |

| 31. Sustainable Policy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 8.33 | 1.65 | 2.73 |

| 32. Social Equity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8.33 | 1.56 | 2.43 |

| 33. Partnerships for Sustainability | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 8.05 | 1.88 | 3.55 |

| 34. Waste Reduction Programs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8.33 | 1.77 | 3.13 |

| 35. Recycling Program | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 6 | 8.48 | 1.72 | 2.96 |

| 36. Incentive Programs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 7 | 8.90 | 1.58 | 2.49 |

| 37. Overseeing Committee | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 8.90 | 1.22 | 1.49 |

| 38. Policy and Regulations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 9.14 | 1.15 | 1.33 |

| 39. Monitoring Programs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 9.05 | 1.12 | 1.25 |

| 40. Data Governance Policies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 12 | 4 | 8.90 | 0.94 | 0.89 |

| 41. Data Governance Processes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 8.81 | 0.93 | 0.86 |

| 42. Management Structures | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 8.95 | 1.28 | 1.65 |

| 43. Consultation and Collaboration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 8.00 | 1.76 | 3.10 |

| 44. Communication Practices | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 8.33 | 1.62 | 2.63 |

| 45. Monitoring and Evaluation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 8.71 | 1.31 | 1.71 |

| 46. Cataloguing and Design | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 8.33 | 1.46 | 2.13 |

| 47. Service Delivery Efficiency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 8.57 | 1.03 | 1.06 |

| 48. Resource Allocation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 8.81 | 0.93 | 0.86 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha = | 0.98 | |||||||||||||

| Parameter | Round 1 | Round 2 |

|---|---|---|

| SD standard deviation max | 2.79 | 2.64 |

| SD standard deviation min | 1.73 | 0.72 |

| % SD < 2 | 93% | 85% |

| OA – overall agreement | 99% | 100% |

| SA – specific agreement | 29% | 96% |

| CA – Cronbach’s Alpha | 0.982 | 0.976 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).