1. Introduction

The higher education domain is facing important alteration, led by technical developments, globalization, and the change of student demographics. Traditional business models are being challenged, and new, innovative methods are developing to meet the evolving necessities of learners and the demands of the modern workforce.

This research discovers the improvement of a disturbing business model in higher education, highlighting the conception of tailored grades. In this model, students have the chance to regulate a customized degree program, credited by an authorization framework like ABET), and tailored to their individual learning goals.

Inspiring this research is the recognition that the troubles created by COVID-19 have underlined the serious meaning of adjustable and adapted learning approaches. The pandemic has not only speeded partial alterations; it has lightened the imperative for educational organizations to hold novelty, ensuring the flexibility and importance of their submissions in a fast-altering world. Our exploration is a suitable response to the request for transformative novelty in higher education.

The suggested business model gets benefits from the newest technologies, like artificial intelligence (AI), ChatGPT, and Gemini, to develop the education capability, make learning personalized, and increase admission to higher education. It highlights the challenges in the higher education domain, including the necessity for flexibility, affordability, and importance in the 21st-century employment market.

This research inspects the modern state of higher education, finds gaps in the literature, and analyses previous research on student-centered learning, learning technology combination, and disturbing business models. It also discovers the possible profits and challenges of the suggested business model, drawing on visions from business experts, tutors, and learners.

2. Literature Review:

2.1. Emerging Technologies in Higher Education

Higher education is a dynamic field continually shaped by evolving trends and technologies, presenting new tools and platforms that develop learning, teaching, and research. These most new and encouraging technologies include artificial intelligence (AI), ChatGPT, and Gemini, which suggest inventive solutions to determine challenges and develop the educational skill.

2.1.1 Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI means the machines’ ability to execute tasks that usually depends on human intelligence, like learning, decision-making, and problem-solving [

1]. In higher education, AI can achieve:

Automate administrative tasks: AI-powered systems have the ability to simplify some managerial procedures, like scheduling classes, grading homework, and organizing student registers, which saves the time of the staff of the faculty for more considered creativities [

1].

Personalize learning: The AI procedures can study the student data to discover their education styles and desires, giving designer recommendations for assignments, courses, and funding services.

Enhance research: AI can help experts in analyzing data, demonstrating, and theory tests, increasing the speed of scientific finding and invention initiatives [

1].

2.1.2. ChatGPT

ChatGPT is a large language model developed by OpenAI which has attracted attention for its capability to produce human-like writing, interpret languages, and answer questions [

1]. In advanced education, ChatGPT can be used to:

Support student writing: ChatGPT can offer remarks on student papers, propose modifications, and produce text prompts, to help learners develop their writing abilities and skills [

3].

Answer student questions: ChatGPT can be like a simulated helper, which can answer the students' questions about course material, homework, and common information.

Facilitate online discussions: ChatGPT can join the online debates, provided that visions and views which improve the student education.

2.1.3. Gemini

Gemini is a multi-modal AI model developed by Google that contains writing, coding, and the ability to generate images [

1]. In higher education, Gemini can be used to:

Generate interactive learning content: Gemini can make cooperative imitations, visualizations, and games which can make education more attractive and reachable initiatives [

1].

Afford personalized learning experiences: The AI procedures can study the student data to discover their education styles and desires, giving designer recommendations for assignments, courses, and funding services, so Gemini can become accustomed to each student needs and learning styles, giving tailored approvals and provision.

Enhance research: Gemini can assist researchers in exploring complex datasets and can help experts in analyzing data, identifying patterns, and generating hypotheses, increasing the speed of scientific finding and invention initiatives [

1].

The AI, ChatGPT, and Gemini combination to the suggested disrupting business model in higher education can affect the educational process in different ways like:

Improving the efficacy and effectiveness of managerial procedures.

Distinguishing the learning practice for individual students.

Improving the research quality and novelty.

Making learning more available and inexpensive for more students.

The COVID-19 pandemic required a quick evolution to virtual and merged education environs, stressing the necessity for new and operative learning tools. Smart learning environments (SLEs) occurred as a promising solution, presenting modified, cooperative, and data-driven education practices. And the SLEs had some benefits and challenges shown as:

Enhanced student engagement: the SLEs offer cooperative and immersive learning involvements which can raise student motivation and engagement [

4].

Personalized learning: SLEs can get used to different student needs and learning styles, providing designer content and support [

5].

Improved access to education: SLEs allows students to reach learning subjects and contribute to classes distantly, decreasing obstacles which face education in the pandemic [

5].

2.2. Key Concepts, gaps and Previous Research

The higher education background is experiencing important alteration, determined by technical developments, globalization, and changing student demographics. To understand this developing site, it is important to inspect key concepts, theories, and previous research that produced the understanding of advanced education. MDPI journals have made important offerings to this discourse, giving valuable visions into the challenges fronting higher education organizations.

2.2.1. Key Concepts

Student-centered learning: An educational method that highlights the requirements and experiences of students, allowing them to have an active part in their education [

5].

Blended learning: An integration of virtual and direct teaching that provides flexibility and personalization to students [

6].

Digital transformation: The combination of digital skills into all features of higher education, containing learning, teaching, and management [

7].

2.2.2. Identified Gaps in Literature in Higher Education

- 1.

Long-Term Impact of COVID-19

- 2.

Customized Degree Programs

The growth and application of disrupting commercial replicas needs additional exploration which enables specialized/customized grade programs.

The request for modified programs should be investigated, the challenges of planning and providing them, and their influence on student products.

The cybersecurity feature of virtual education is still a serious gap, requiring research to protect digital learning environments [

8].

The vulnerabilities of the online learning platforms still need to be examined, cybersecurity measures need to be developed effectively, and awareness raised between students and teachers.

- 4.

Sustainability of Hybrid Models

2.2.3. Previous Research

MDPI journals have published numerous studies that have explored key concepts and theories in higher education. Some notable examples include:

A study [

5] investigated the challenges and opportunities of future learning environments with smart elements.

A study [

6] examined the effectiveness of blended learning models in improving student satisfaction and academic performance.

Research [

7] analyzed the challenges and opportunities of digital transformation in higher education, highlighting the need for institutional support and faculty training.

3. The Current Business Model in Higher Education

The current business model in higher education is a multifaceted construct influenced by various factors, including funding sources, competition, technology, and institutional values. A business model in the context of higher education refers to the overarching strategy and framework that educational institutions employ to generate revenue, allocate resources, and deliver educational services [

10]. It encompasses various factors, including funding sources, revenue streams, and the institution's core mission [

11]. As higher education continues to evolve, institutions must carefully navigate this landscape to ensure their financial sustainability while upholding their commitment to academic excellence and societal impact [

12].

Higher education institutions worldwide operate within a complex ecosystem that necessitates the adoption of sustainable and effective business models. The current landscape of higher education business models reflects an intricate interplay of factors such as funding sources, revenue streams, and institutional priorities. Traditionally, higher education institutions have relied heavily on a mixture of tuition fees, government funding, and endowments to sustain their operations [

11]. This revenue model often manifested itself as a hybrid between public and private funding sources, with public institutions drawing substantial support from government coffers [

13]. However, the financial landscape has evolved significantly over the years, prompting institutions to diversify their revenue streams and explore alternative business models.

One prominent trend in recent years has been the commercialization of higher education, driven in part by the globalization of educational services [

14]. The rise of online and distance education platforms has facilitated the entry of private providers into the higher education space [

15]. These providers often operate on a for-profit basis, challenging the traditional non-profit model of many universities. This shift has raised questions about the priorities of institutions and their commitment to academic quality and student welfare [

16]. Furthermore, the competitive landscape has spurred innovation in the delivery of educational services [

17]. Universities have begun to explore new revenue streams through continuing education, executive programs, and partnerships with industry [

18]. Additionally, philanthropy and fundraising have played an increasingly vital role in the financial sustainability of higher education institutions [

19].

The role of technology in the current business model cannot be overstated. Digital transformation has allowed institutions to optimize their operations, enhance student experiences, and expand their reach [

20]. Online education has proven to be a lucrative venture for many institutions, offering scalable and cost-effective methods of program delivery [

21]. However, this transition has also raised concerns about equity, access, and the commodification of education [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. While financial sustainability is a paramount concern, the current business model must also align with the core mission and values of higher education institutions [

12]. Striking a balance between financial viability and the preservation of academic integrity remains an ongoing challenge [

23]. Institutions must grapple with questions of affordability, accountability, and the ethical dimensions of their revenue-generating activities [

18].

In summary, the current business model in higher education is a multifaceted construct influenced by various factors, including funding sources, competition, technology, and institutional values. As higher education continues to evolve, institutions must carefully navigate this landscape to ensure their financial sustainability while upholding their commitment to academic excellence and societal impact.

4. Disruptive Higher Education Business Model

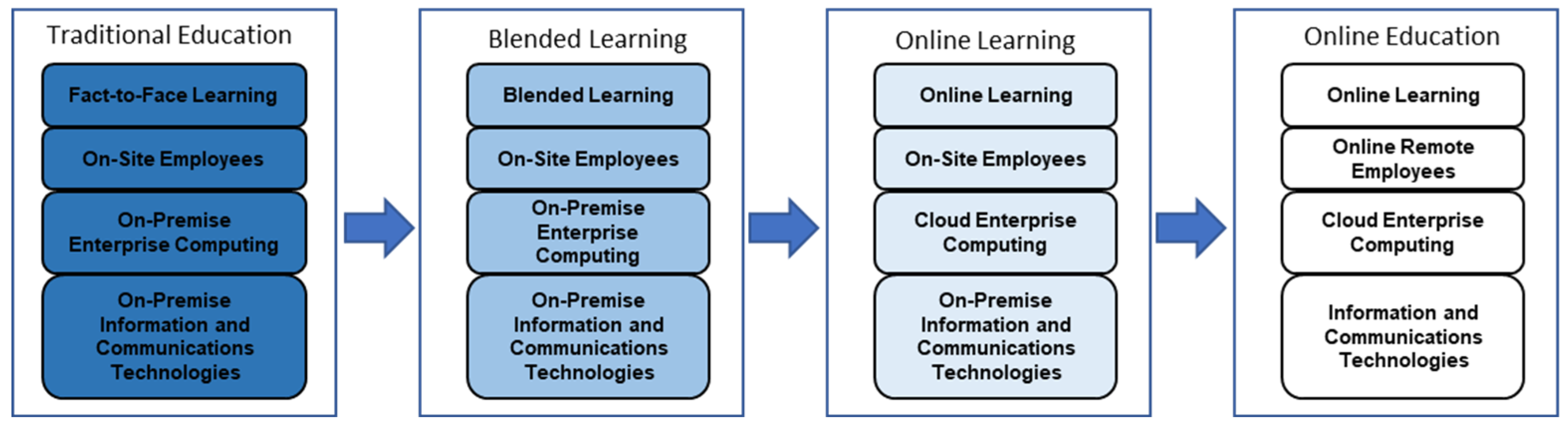

Higher education institutions are witnessing a progressive paradigm shift in the teaching and learning process and its support services and systems, as shown in

Figure 1. The shift is now happening from traditional education to blended learning. Institutions in the developed world have successfully moved to the blended learning paradigm. In contrast, other institutions that don’t have the necessary infrastructure are not yet ready to adopt the blended learning approach. Most models developed by higher education institutions address aspects of the learning process and do not offer systematic changes in the entire model. In general, it seems reasonable to claim that most disruptive initiatives in higher education are incomplete and inconsistent and, thus, cannot be duplicated by other organizations. It is necessary to design a model that would address all the relevant aspects of higher education and meet the expectations of all the relevant stakeholders.

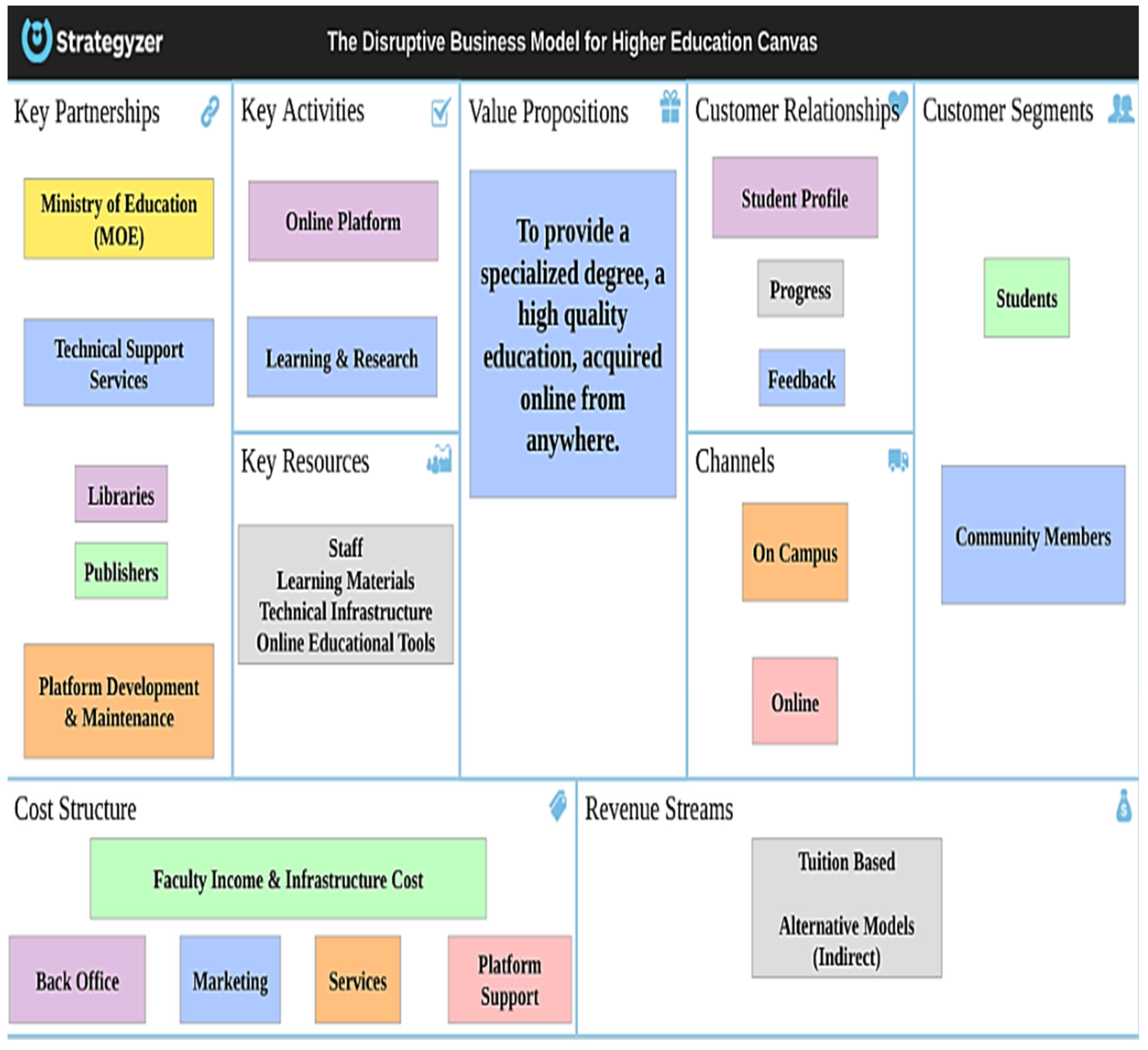

This section presents a framework for a disruptive higher education business model that can be considered a viable alternative to the existing business model in higher education. It illustrates the main features of a model that could reshape the higher education system towards increased affordability, improved quality of educational services, and a reduced gap between the expectations of employers and the skill sets and knowledge of graduates. The discussion will be based on the business model canvas designed by Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010). This concept identifies nine business model components, including customer segments, value propositions, customer channels, customer relationships, revenue streams, key activities, key resources, key partners, and a cost structure, as shown in

Figure 2.

4.1. Customer Segment

The higher education system serves individuals seeking skills development and higher qualifications in the desired specialty. An effective disruptive model of higher education is supposed to expand the target audience. Most other disruptive business models offer only narrow customer segments. In contrast, learning outcome-based systems focus on customers who seek education in practical niches that could be quickly converted into a job position. The model developed by Osterwalder & Pigneur (2010) helps elucidate how customer groups will be affected by the new model and draw a student profile.

The customer segment in the proposed business model for higher education includes all kinds of students, including those who live overseas and those who cannot afford educational expenses, and community members, including faculty members, administrators, and guardians. A system should be flexible to meet these criteria, offering educational services at varying pricing levels. A new/disruptive business model will significantly attract many students, which, in turn, will help reduce tuition costs. In addition, organizations will have a chance to attract applicants from other countries.

As it is known, affordability and geographic coverage are currently important challenges faced by the higher education system. Institutions based on the disruptive business model will have to address this issue to expand their customer groups. A low tuition price might be one way to achieve this goal; however, some individuals will not afford tuition even if its price is significantly reduced. To cover this target audience, institutions will need to develop alternative instruments of revenue generation, such as taking a percentage of students' future earnings.

4.2. Value Proposition

The value proposition of the proposed business model is to provide a specialized degree, and a high-quality educational experience acquired online and from anywhere. The business model will have two important benefits. First, it will ensure a high degree of specialization. This will simplify the process of finding high-paid jobs for graduates. The second advantage is that educational services will be available to many potential customers, regardless of their financial well-being and geographic location.

4.3. Customer Channels

Various customer channels, such as email, mobile phones, digital applications, websites, and social media can be used. At the same time, the proposed model implies enabling a higher educational degrees-based online system to empower the new disrupted model of higher education to revolutionize the educational system. Creating a single platform that would accumulate the courses from all the leading universities and providing reliable and trusted channels that would link customers to educational institutions is paramount.

4.4. Customer Relationships

Customer relationships are one of the most challenging matters in the disruptive higher educational model. Teachers and students rarely interact face-to-face during blended learning courses. The current model differs from other projects in its emphasis on customer relations. It relies on such mechanisms as managing students' course expectations, creating clear assignment tutorials, uploading video biographies of teachers, sharing relevant personal experiences of a teacher regularly, ensuring that teachers take an interest in student's lives, and regularly collecting data from both students and teachers, and increasing students' engagements via personalized video feedback and video calls.

4.5. Revenue Stream

The tuition-based model is the basic approach toward revenue generation that allows educational institutions to earn money from tuition payments. In the most general view, possible revenue generation models could be divided into the advertising, subscription, tuition, and brokerage fee subcategories [

25]. The new business model's revenue streams are diverse, superior to employer-funded and learning outcome-based models. The current model allows higher education institutions to offer various models for customer segments. Eventually, this approach is expected to ensure that institutions attract more students.

4.6. Key Activities

Using a disruptive business model for higher education could help substantially increase the number of key activities. In addition to traditional lectures, seminars, group discussions, written assignments, oral speeches, and final coursework or thesis, such model may also include online masterclasses, forums, interviews with experts, online tests, online communication with a tutor, and many other activities [

26]. With the help of a disruptive model, the higher education system can offer customized solutions based on a sensory system preferred by specific students, the amount of available time, costs, and many other factors. In general, increased activities could make higher education much more flexible. In turn, this advantage is expected to improve the quality of educational services. In the most general view, the key activities of institutions based on the disruptive business model of higher education could be divided into several groups following the categories shown in

Table 1 below.

4.7. Key Resources

Table 2 shows a list of key resources needed to support the business model of higher education. Institutions may use a single higher educational degree-based online system. They may also choose learning resources from the list of solutions approved by the local governing education entity. This way, organizations will minimize the chance that some technical errors or other shortcomings of learning resources and solutions will undermine the quality of services. For instance, in the case of the United Arab Emirates, organizations should use only those solutions that the government has approved, such as "School, McGraw Hill, Oxford University Press, College Board, Code dot or cde.org, Matific and Alef, Twig platform, Ynmo grow, and Nahla platform And Nahal, Bookclip, Lernetech, and Microsoft Teams" (Jamal, 2020). At the same time, while these restrictions create limitations for the model, they also help systematize its application and ensure its consistency. Moreover, institutions will also be safeguarded from possible technical flaws of unreliable platforms and software problems. This advantage could be barely found in learning outcome-based and employer-funded models.

4.8. Key Partnerships

The success of a business model requires the support of business partners. Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) model allows investigating and explaining how strategic partnerships could help institutions ensure that the model translates into high-quality educational services. The available evidence provides a premise to believe that it is important to coordinate the efforts of educational institutions and key partners, such as government authorities, influencers, IT developers, employers, etc. The need for such coordination is a popular recommendation that is often mentioned in the literature regarding the future of online education [

28]. While the government and educational institutions explain the benefits of the new strategy, employers could display their commitment to hiring people who graduate from institutions that operate based on this disruptive model.

4.9. Cost Structure

An organization operating based on the new model could save substantial money on rent, as it would not need such large spaces as a traditional educational institution. Since rent, maintenance, and other related expenditures usually are a major component of the cost structure of any educational institution [

29].

From the cost structure perspective, the proposed model is more beneficial for institutions than employed-funded and learning outcome-based ones. These systems rely on future earnings obtained as a percentage of students' salaries or work inputs; however, their costs are similar or even higher than those of "traditional" higher education institutions. The cost per student is higher in both these models because they do not transfer all the learning activities to the online domain. By postponing their revenues, organizations expose themselves to increased risks related to delayed or missed payments; furthermore, it becomes harder to accumulate and invest cash into infrastructure development and other strategic projects.

5. Research Methodology

This part describes the research methodology applied during the study. It covers details about the research approach, the research design, and the advantages and disadvantages of the chosen research technique. It also explains the ethical aspects of this methodology and concludes with a brief explanation of the limitations of this research design. Moreover, this section covers how the data was collected and analyzed. The participants were chosen from the target industry (higher education). Moreover, the results were analyzed statistically through graphs and charts.

5.1. Research Approach

A quantitative methodology is implemented in this study. In theory, a qualitative approach could have also been used; however, after thorough consideration, it was decided to select a quantitative one. The data collected can be interpreted using visual, textual material, and oral history [

30].

Moreover, it would be very hard to compare the perspectives of students, teachers, and parents using a qualitative approach. In contrast, a quantitative methodology will allow collecting data on the use of online technologies in educational technologies and their perception by relevant stakeholder groups.

5.2. Research Methods

This research implemented the quantitative approach. Therefore, the data collected was numeric. The quantitative research strategy allowed retrieving information on various useful parameters, such as the number of teachers who use online technologies in the classroom and students' perceptions of online learning. Tools such as bar graphs and pie charts were used to interpret and visualize the data collected. Through this research design, the data collected has helped investigate the research problem and develop meaningful recommendations.

The survey was implemented to help in collecting data for this research. Surveys aim at making inferences about a specific sample from a population. This design contrasts with a census that makes observations from an entire population. Thus, this survey was aimed at university students, administrators, faculty members, and parents from the UAE. The sample population represents the primary stakeholders of higher education.

Google forms were used to implement the questionnaire and then distributed to the sample population (students, teachers, parents, faculty members, and university administrators. The sample population was chosen from five universities based in UAE. These universities include Alain University of Science and Technology, Ajman University, Khawarizmi International College, United Arab Emirates University, and Abu Dhabi University. The faculty's email addresses were collected through their university websites. So, the surveys were distributed to the faculty members by email. The College of Graduate Studies provided the students' emails. However, compared with students and faculty, parents were the least percentage. The survey was distributed on WhatsApp to reach school students' parents.

5.3. Design of the Questionnaire

The questionnaire includes open and closed-ended questions. The open-ended questionnaires require a full explained answer while closed-ended questions are usually a yes or no question. In the first survey, the participants were asked closed-ended questions. The second survey and the third survey contained a mixture of both open and closed questions.

The use of more closed-ended questionnaires was preferred in this research. It was intended to improve the quality of the answers received. For example, when asking about Internet speed, the participants were expected to rate it as fast, average, or slow. Thus, the closed-ended question helps receive the expected response that is believed to be accurate [

31]. Moreover, the participants were teased to give additional information by asking an open-ended question at the end. For example, an open-ended question is concluded with a "why" question, as shown in this question:

Would you prefer to take this course online or in the classroom? Why?

The "why" question expects participants' explanation of the closed-ended question. Mixing open- and closed-ended questions encourages a rational answer and avoids artificial responses.

5.4. Methods of Data Analysis

The data analysis in the questionnaire was conducted by simply calculating the number of respondents who have given specific answers to certain questions. No statistical instruments were used in data analysis, as the measurement of correlations between variables was not within the scope of the study. In addition, charts were used to visualize the data. Pie charts and bar graphs are vital in analyzing and presenting the survey's results in an understandable format [

31].

5.5. Ethical Consideration

Ethics should be considered when participating in collecting user data and opinions. Although private information was not collected in this research, such as names and contact data, we adhered to the ethics of data collection. In this research, the participants in the survey had informed consent. The users were informed of each questionnaire, the reason for collecting it, and how the data will be used. Therefore, they were aware of the risks and consequences of their decisions. Thus, they participated in the research voluntarily. The anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were respected. Therefore, the participants were informed not to write their names or personal details on the questionnaires.

5.6. Problems and Limitations

The methodology chosen had several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was small. Therefore, the data collected, and findings could not be extrapolated to a broader scale. Secondly, the time for conducting this research was limited. More time is required to reach out to a large sample population and gather adequate responses. Thirdly, an interpretive approach was used, determined by the nature and objectives of the research [

32]. This research is biased because the connection between variables is analyzed according to the basis of the analytical and judgmental expertise by target population in the academic arena.

6. Survey Results and Analysis

The empirical part of this study implied conducting one survey to investigate the potential of a disruptive business model of higher education to succeed in the UAE. The survey aimed to collect data on integrating the Internet in higher education from students, teachers, and parents. This information was crucial for determining whether key stakeholders in the UAE are ready to launch the new model of higher education.

6.1. The Data from Students

Almost 49% of the study's respondents were students, including 72.9% of females and 27.1% of males. Such a high percentage of females in the sample is natural, as it harmonizes with the recent trends of the popularization of women's education in the United Arab Emirates [

33]. The research participants included individuals studying Bachelor's, Master's, and Ph.D. programs; furthermore, they represented ten different United Arab Emirates University colleges. The demographic characteristics of respondents illustrate that the survey collected data from students who represent various groups, thus contributing to the validity and reliability of the study's findings.

As shown in

Table 3, only 8.6% of students attend university courses with the help of blended learning systems, and none acquire a degree through exclusively online education. This finding harmonizes with the dominant opinion that the popularity of online education in the UAE is still low [

2]. At the same time, the Internet proficiency of most students allows them to engage in e-learning, almost 90% have significant Internet usage skills, 98.3% have access to the Internet at home, and 96.6% have an internet connection in the classroom. In other words, it seems that students are prepared for online education's expansion. Some aspects of online education are already present: more than 60% of learners use the Internet regularly or occasionally to communicate with their instructors, and 96.6% sometimes use Internet technologies in the classroom. The numbers above illustrate that launching online education has already started and achieved significant progress in the country.

At the same time, despite these promising signs, around a third of students are barely ready for the full-scale implementation of blended learning systems. In

Table 4, 30.5% do not use social media for downloading or sharing content, 30.5% do not utilize online libraries, 24.1% have never used cloud technologies in the learning process, and 61% (

Table 5) have never been introduced to online courses by an instructor.

The survey results illustrate that a further expansion of online learning might meet a substantial resistance to change among around a quarter of students, which is cited in the literature as one of the most disturbing barriers to implementing e-learning activities [

34]. In this situation, it seems justified to claim that while some UAE institutions might be ready to launch blended learning systems, they will likely face essential obstacles. At the same time, it might be possible to gradually expand the use of online instruments in the higher education system, thus gradually preparing stakeholders for applying the disruptive model.

An analysis of students' perceptions illustrates that most enthusiastically perceive the idea of embracing online education. In

Table 6 and

Table 7 - respectively - 98.3% and 96.6% of them believe that the Internet can improve academic performance and facilitate learning, respectively. Simultaneously, 67.8% of them do not agree with the appeal to make all the lectures and courses online, it is very important to emphasize that most people who are not willing to attend online learning activities without any offline events have an incomplete understanding of the concept of online learning. As shown in

Table 8, 55.9% of the sample cannot decide whether they support the implementation of online courses, which points to a high level of uncertainty concerning this matter. Similarly, 35.6% of the survey's respondents are unsure whether acquiring a Bachelor's, Master's, or Ph.D. degree through an online university may be a viable option.

While many students are skeptical regarding online education, 96.6% would be interested in customizing their learning plan (

Table 9). In

Table 10, 72.9% of the sample prefer offline courses over online training, which explains why students rarely consider online education an instrument of such customization.

6.2. The Data from Faculty

An analysis of the questionnaires filled out by faculty members illustrates that they represent various demographic groups and teach at different colleges. More than 95% of them claim to have significant Internet usage skills. The overwhelming majority of these people already use the Internet to communicate with other professors and students, and 95.8% of the sample have Internet access inside classrooms. 87.5% of teachers benefit from the Internet in course development, and 85.4% have made the material they are teaching available online. At the same time, it seems justified to claim that the degree to which the Internet is integrated into the daily work of the faculty is still moderate, as only 43.8% of them regularly utilize the Internet and online technologies in their classrooms (

Table 11). Only 2.1% of the sample reported a low Internet connection speed. From this perspective, teachers' responses harmonize with the opinions of students.

These numbers show that the Internet has already become integral to the learning process. Nevertheless, despite this trend, most teachers have not incorporated any elements of online learning into their curriculums. Only 18.8% of them have taught at least one course online. These teachers have no agreement concerning the optimal platform for administering online education. As shown in

Table 12, and independent of the needs of a particular course or learning activity, they may use Zoom, Skype, YouTube, WiziIQ, and social media. At the same time, there is no information concerning incorporating those learning resources discussed regarding the proposed business model, which is a disturbing sign of its applicability. Interestingly, most teachers consider social media as unreliable platforms; as a result, only 36.4% of them share learning content on social networks.

An analysis of the survey's results illustrates that most instructors do not use all the advantages of online technologies. In particular, more than 79% and 63% of the sample employ some elements of cloud technologies and online libraries, the popularity of student response tools and discussion boards is low. Most faculty members regard the Internet as a helpful mechanism that can supplement traditional learning and provide effective solutions for solving specific problems, such as recording students' attendance. Simultaneously, the potential of online technologies to revolutionize the higher education system is barely recognized by respondents. Only 12.5% agree that online courses may be more effective than offline learning activities, and less than 40% of the sample is willing to deliver an online course. These numbers harmonize with a popular concern that many teachers might not be prepared to teach online courses. In

Table 13, the fact that only 16.6% of teachers are open to the idea of supporting the acquisition of Bachelor's, Master's, and Ph.D. degrees through an online university confirms this trend. Most teachers are not psychologically prepared to implement a disruptive model of higher education.

6.3. The Data from Parents

While all the parents have an Internet connection at home, their Internet fluency is much lower than among students and teachers. More than a third of the sample argues that their skills in using the Internet are average. All the parents who participated in the survey support using the Internet in education, and 73.3% of them point out that their children already employ online technologies in their studies. Parents generally seem to display more positive attitudes towards integrating the Internet into the learning process than the faculty. Only 20% of parents would not support their children in acquiring a university degree online (

Table 14). Moreover, as shown in

Table 15, 46.7% of them would prefer online courses over the option of sending their children to a university.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

The paper proposed a disruptive business model for higher education. It is based on integrating online technologies into the learning process and uses blended teaching instruments to cover the maximum number of customers. The model is based on the canvas offered by Osterwalder and Pigneur. It allows integrating all the relevant aspects of higher education institutions into a consistent framework and aligning them with the needs and expectations of pertinent stakeholders. Institutions that follow this model will promote the highest degree of customization in their courses, allowing students to acquire specialized skills and knowledge necessary for working in their specific sector or niche. Due to a shift to online learning, universities and colleges will be able to reduce their expenses and, as a result, improve work conditions for the academic staff and make courses more affordable.

Results of the survey carried out in the study illustrate that students, teachers, and parents in the United Arab Emirates are ready to implement such a disruptive model. They are proficient in using Internet technologies in learning; moreover, online instruments have already become an unalienable part of most courses at UAE higher education institutions. High resistance to change currently observed in the UAE regarding the embracement of online learning may be rather explained by the low level of stakeholders' awareness of the specifics and benefits of this instrument than by their unwillingness to embrace this innovation. To apply the new disruptive model of higher education, it is paramount to ensure the stable work of electrical equipment and a fast Internet connection. It is also of paramount importance to continue collecting data from all the relevant stakeholders to determine an optimal design of an educational process that would be suitable for all concerned parties.

Since the educational service is provided directly to students, future work will focus solely on higher education students as they are the primary customer segment of the proposed business model. A framework of the business model should be identified. The framework should provide a strategy for higher education that allows students to customize and accredit their learning plans. This can be achieved by exploring the existing frameworks like Abet, which provides accreditation per program. Then, create a specialized framework for the proposed business model whose main objective is to provide accreditation per student.

References

- Dempere, J.; et al. (2023) The impact of CHATGPT on Higher Education, Frontiers. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1206936/full (Accessed: 31 March 2024).

- Alkaabi, S.A.; Albion, P.; Redmond, P. Blended learning in the United Arab Emirates: Development of an adaptability model. Asia Pacific Journal of Contemporary Education and Communication Technology 2016, 2, 1–23, https://apiar.org.au/wpcontent/uploads/2017/02/13_APJCECT_Feb_BRR798_EDU-126-131.pdf Access date: 08-April-2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, S. Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students’ academic writing skills: a mixed methods intervention study. Smart Learning Environments. Mahapatra Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogas, J.; Palau, R.; Fuentes, M.; Cebrián, G. Smart schools on the way: How school principals from Catalonia approach the future of education within the fourth industrial revolution. Learning Environments Research 2022, 25, 875–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.K.S.; Kwok, L.F.; Phusavat, K.; et al. Shaping the future learning environments with smart elements: challenges and opportunities. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 2021, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, S. Blended Learning in Higher Education: An Approach, a Model, and Two Theoretical Frameworks. Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hashim, M.; Tlemsani, I.; Matthews, R. Higher education strategy in digital transformation. Educ Inf Technol 2022, 27, 3171–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulven, J.B.; Wangen, G.B. A systematic review of cybersecurity risks in higher education. Future Internet 2021, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisadza, C.; Clance, M.; Mthembu, T.; Nicholls, N.; Yitbarek, E. Online and face-to-face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid-19 pandemic. Afr Dev Rev. 2021, 33 (Suppl 1), S114–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, D.; Anderson, M. Disruptive Business Models in Higher Education: A Review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2017, 14, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Hauptman, A.M. The History and Future of Tuition. New Directions for Higher Education 2018, 2018, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter, S.; Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, State, and Higher Education. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Hudspeth, N.; Wellman, G.C. Equity and public finance issues in the state subsidy of public transit. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 2018, 30, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P.G.; Knight, J. The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities. Journal of Studies in International Education 2007, 11, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, A.W. (2019). The Impact of the Internet on University Teaching and Learning. In M. J. W. Lee, C.R.M. Dennen, & G. C. Enfield (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 725–734). Springer.

- Eaton, J.S. Commercialization and Higher Education: A Literature Review. Canadian Journal of Higher Education 2010, 40, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Eyring, H.J. (2011). The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education from the Inside Out. Jossey-Bass.

- Eckel, P.D.; King, J.A. An Overview of Trends in Privatization of Public Higher Education. New Directions for Higher Education, 2004, 2004, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, R.; Starke-Meyerring, D. Uncovering Collaboration: An Analysis of the Interactions between Continuing Education and Academic Units in Canadian Universities. Journal of Continuing Higher Education 2008, 56, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, N. Digital Transformation in Higher Education: A Case Study of a "Smart" University. Journal of Educational Technology Systems 2020, 49, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. (2017). Digital Learning Compass: Distance Education Enrollment Report 2017. Babson Survey Group.

- Selwyn, N. What’s the Problem with Learning Analytics? Journal of Learning Analytics 2019, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, C. Academic Earmarks and the Future of American Research Universities. The Journal of Higher Education 2010, 81, 513–536. [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. Hoboken, CA: Wiley.

- Mendling, J.; Neumann, G.; Pinterits, A.; Simon, B. Revenue models for e-learning at universities. Withschaftsinformatik 2005, 1, 827–846. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.R. (2011). Global e-learning: A phenomenological study. Fort Collins: ColoradoaStateaUniversity:hhttps://mountainscholar.org/bitstream/handle/10217/70652/Rao_colostate_0053A_10885.pdf. Access date: 27-February-2020.

- Jamal, A.A. (2020). MOE adapts 13 online platforms to support distance learning. The Emirates Today. Retrieved from https://www.emaratalyoum.com/local-section/education/2020-03-25-1.1324800. Access date: 03-April-2020.

- Dabbagh, N.; Marra, R.M.; Howland, J.L. (2018). Meaningful online learning: Integrating strategies, activities, and learning technologies for effective designs. London: Routledge.

- Estermann, T.; Claeys-Kulik, A.L. (2013). Financially sustainable universities: Full costing: Progress and practice. EUA. Retrieved from https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/financially%20sustainable%20universities%20full%20costing%20progress%20and%20practice.pdf. Access date: 07-September-2018.

- Mohajan, H. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People 2018, 7, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, A.M.; Novikov, D.A. (2013). Research methodology: From philosophy of science to research design. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Pham, L. (2018). A Review of key paradigms: positivism, interpretivism and critical inquiry. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324486854. Access date: 10-April-2019.

- Ridge, N. The hidden gender gap in education in the UAE. Dubai School of Government 2009, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gillett-Swan, J. The challenges of online learning: Supporting and engaging the isolated learner. Journal of Learning Design 2017, 10, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).