Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

0. Introduction

I. Symmetry of the World Line of an Escaping Galaxy in Front of and Beyond the Cosmic Event Horizon Because of a Time-Reversal

- a)

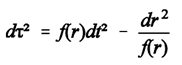

- The Schwarzschild solution of Einstein’s field equation

(1)

(1) - b)

-

The Schwarzschild solution of Einstein’s field equation for a single, non-rotating spherical mass

- aa)

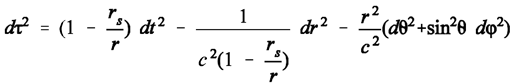

- When completed, the first variant of the Schwarzschild solution (which deals with a spherical, non-rotating mass) reads (in polar coordinates t, r, theta, phi):

(2)

(2)- c)

-

The Schwarzschild solution of Einstein’s field equation for a steadily expanding universe in which dark energy prevails over matter

- aa)

-

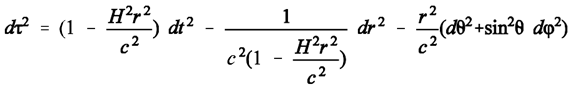

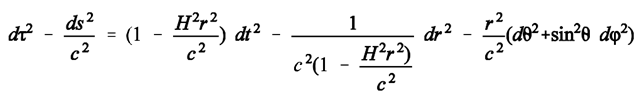

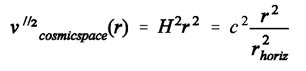

The second variant of the Schwarzschild solution deals with the visible universe as a whole. It describes a De-Sitter-universe, in which dark energy prevails over matter (so that matter is negligible), and in which the Hubble-constant H is invariant over space and time. The cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution (De Sitter space) is:

(3)The distance r denotes circumference of a circle around the center of the Milky Way divided by 2 pi; time t is the time measured in the Milky Way; time tau is the time measured in the escaping galaxy. Equation (3) can be found in E. Gaztanaga (2022), his Equation (3) and his Figure 1 [his r* is equal to 1/H, his c is equal to unity, as is made evident between his Equations (2) and (3)].

(3)The distance r denotes circumference of a circle around the center of the Milky Way divided by 2 pi; time t is the time measured in the Milky Way; time tau is the time measured in the escaping galaxy. Equation (3) can be found in E. Gaztanaga (2022), his Equation (3) and his Figure 1 [his r* is equal to 1/H, his c is equal to unity, as is made evident between his Equations (2) and (3)].

- bb)

-

In that variant, the role of a Schwarzschild horizon of a black hole is replaced by the cosmic event horizon (see also Gaztanaga, op. cit). Different from the Schwarzschild horizon of a black hole, the cosmic event horizon is a relative thing, and every galaxy has one of its own. The Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon is located at a distance of rhoriz= c/H = 14,000,000,000 lightyears. The parameter c is the local speed of light. The local speed v’’ at which an observer who sits in immediate front of the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon – and is connected to the Milky Way by a tether that keeps his or her distance from the Milky Way constant – watches an escaping galaxy pass by is very close to that speed c.A neighboring galaxy (that is, a galaxy neighboring our Milky Way) which is not gravitationally bound to any other galaxy will pick up speed as a result of the expansion of space, and will eventually reach the fixed cosmic event horizon several billion lightyears away. Just in front of the cosmic event horizon, the local escape velocity of that escaping galaxy, judged from the perspective the aforementioned local observer who is connected to the center of the distant Milky Way by an imagined, extremely long tether (and is thus standing still with respect to the Milky Way), is almost c (as has been stated already). One should note that escaping galaxies are merely small test-objects in this model in which matter-density is negligible by presupposition (the tensor T in Einstein’s field equation is vanishing everywhere and and at any time).

- cc)

- The escaping galaxy will eventually cross the cosmic event horizon (that is attributed to the reference frame of the Milky Way). But apparently, it will do so only in the reference frame of that escaping galaxy, where this invisible borderline will rush by at a speed of c (just as other galaxies’ cosmic event horizons are rushing past us here on Earth every second at velocity c). From the perspective of the Milky Way, this galaxy is more or less not moving at all, but has got “frozen” in front of the cosmic event horizon, just as freely falling Alice gets “frozen” in front of the Schwarzschild horizon of a black hole from the perspective of distant Bob (see Gaztanaga, op. cit.: “No signal from inside r* can reach the outside, just like in the interior of a BH.”)

- d)

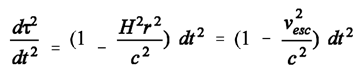

- The world line of an escaping galaxy on a t,r-chart

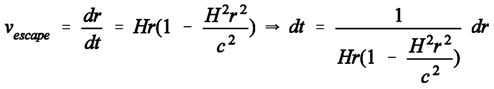

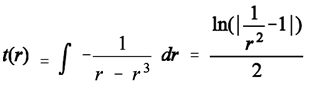

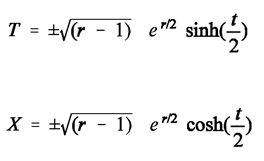

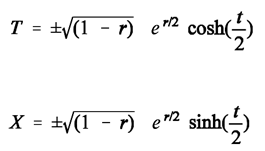

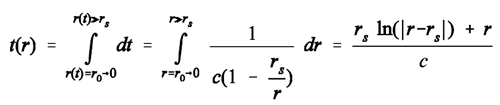

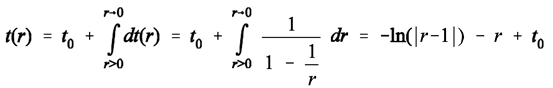

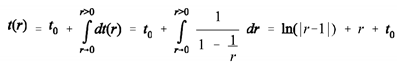

(4)

(4) (5)

(5) (6)

(6) (6a)

(6a)- e)

-

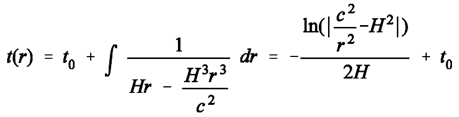

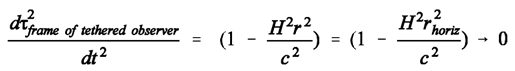

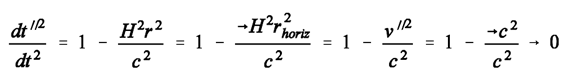

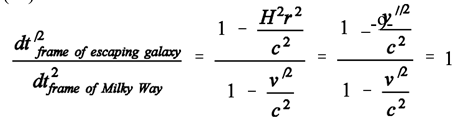

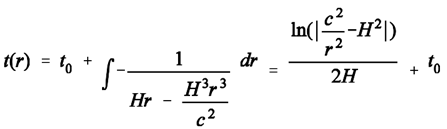

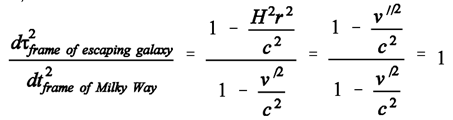

The behaviour of clocks co-moving with the escaping galaxyAs mentioned above, an observer who sits in front of the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon, and who is connected to the Milky Way by a tether that keeps his or her distance from the Milky Way constant, will also undergo a dilation of his or her time tau (judged by an observer in the Milky Way). This dilation is given by (1), since, in this special case, dr, d phi and d theta are all zero. We therefore get from (1):

(7)Because of rhoriz= c/H , the quotient dtau/dt vanishes for an r that is approaching rhoriz .Similarly, a radially oriented meter stick held by the tethered observer is contracted in the reference frame of the Milky Way. Its contraction is given as follows when (1) is written in its complete form:

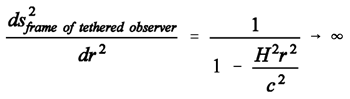

(7)Because of rhoriz= c/H , the quotient dtau/dt vanishes for an r that is approaching rhoriz .Similarly, a radially oriented meter stick held by the tethered observer is contracted in the reference frame of the Milky Way. Its contraction is given as follows when (1) is written in its complete form: (8)The parameter ds is the spatial proper length between two local chains of “vertical-world- line” events (as opposed to point events). When a local meter stick rests in the reference frame of the observer (Alice) who sits in the gravity field, both the continued existence of its one end and also the continued existence of its other end form a vertical world-line each in Alice’s tau, r-chart. Since the meter stick is also stationary in Bob’s frame of reference, the two ends also form vertical world-lines in Bob’s t,r-chart. In order to determine the time- invariant spatial distance between the two ends in the two frames of reference, that is, between the two vertical world-lines, both Alice’s d tau and Bob’s dt are set to zero. Given that d tau, dt, d phi and d theta are all zero, we then get by a re-arrangement:

(8)The parameter ds is the spatial proper length between two local chains of “vertical-world- line” events (as opposed to point events). When a local meter stick rests in the reference frame of the observer (Alice) who sits in the gravity field, both the continued existence of its one end and also the continued existence of its other end form a vertical world-line each in Alice’s tau, r-chart. Since the meter stick is also stationary in Bob’s frame of reference, the two ends also form vertical world-lines in Bob’s t,r-chart. In order to determine the time- invariant spatial distance between the two ends in the two frames of reference, that is, between the two vertical world-lines, both Alice’s d tau and Bob’s dt are set to zero. Given that d tau, dt, d phi and d theta are all zero, we then get by a re-arrangement: (9)The quotient ds/dr goes to infinity when r approaches rhoriz.

(9)The quotient ds/dr goes to infinity when r approaches rhoriz.- bb)

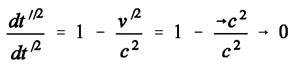

- Let us now turn our attention to the (single-primed) reference frame of the escaping galaxy that finds itself near the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon. In that frame of reference, the dilation of time of a clock held by the (nearby) tethered observer is described by Special Relativity, as it is attributed to the motion of the tethered observer and his or her clock (and not to the motion of space). In comparison, the dilation of time t’’ of a clock held by the tethered observer with respect to the Milky Way’s time t is NOT due to the fact that the tethered observer’s clock is in motion. For this clock is stationary in the Milky Way’s reference frame. We nevertheless have (because of Equation 3):

(10)

(10) (11)

(11) (12)

(12)- f)

- The two axioms of General Relativity must be understood as local principles

- g)

-

The flow of space not only as a cause of the expansion of space, but also as the cause of time dilation and length contraction in Relativity in general

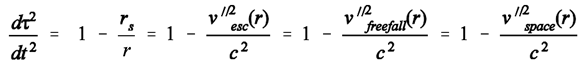

- aa)

- As has been stated above, time of the tethered observer is dilated in the Milky Way’s frame of reference, even though the distance between the Milky Way and the tethered observer does not change with time. How then can that time dilation (and length contraction) be accounted for in physics (apart from the simple fact that is follows from the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution)?

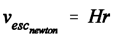

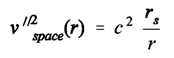

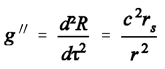

The answer is: It is the flow of space past a clock and past a meter stick that is responsible for these two relativistic effects. As regards the tethered observer, space volumes that, as a result of cosmic expansion, have emerged somewhere between the Milky Way and its cosmic event horizon rush past the tethered observer at a local velocity of almost c, whereas the escaping galaxy is embedded in that flow. There is simply no other explanation of the behaviour of stationary meter-sticks and stationary clocks other than an expansion of space in a t,r- reference frame of the Milky Way in which the spatial distances between meter-marks are NOT expanding, but are static. As Gaztanaga (op.cit.) correctly put it: “As H becomes dominated by lambda, the expansion becomes static ... in the SW frame.”In the black-hole variant of the Schwarzschild solution (which describes the situation around any spherical, gravitating object), things are similar. For we have: (13)and hence:

(13)and hence: (13a)The parameter v’’esc is the local escape velocity in the gravity field of a spherical mass (whose Schwarzschild radius is rs). In other words: v’’esc is the local escape velocity of a stone that is tossed upward by a stationary observer (whose time is tau) in the gravity field of a spherical mass. That velocity is the same in magnitude as the velocity of a test object in free radial fall that started its journey far away at an initial velocity of almost zero. That velocity, in turn, is not the result of an accelerating force, but of geometry of space; this is because a falling test object is simply following a geodesic. Then it is space itself that is gathering speed. There is no other explanation of what “following a geodesic” could possibly mean.

(13a)The parameter v’’esc is the local escape velocity in the gravity field of a spherical mass (whose Schwarzschild radius is rs). In other words: v’’esc is the local escape velocity of a stone that is tossed upward by a stationary observer (whose time is tau) in the gravity field of a spherical mass. That velocity is the same in magnitude as the velocity of a test object in free radial fall that started its journey far away at an initial velocity of almost zero. That velocity, in turn, is not the result of an accelerating force, but of geometry of space; this is because a falling test object is simply following a geodesic. Then it is space itself that is gathering speed. There is no other explanation of what “following a geodesic” could possibly mean.- bb)

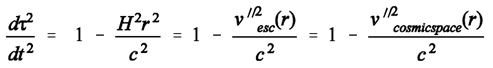

- For comparison, we have in the cosmic case:

(13b)and

(13b)and (13c)Textbooks tend to “blame” the effect of time dilation of a stationary clock in a gravity field of a spherical mass) simply on “local gravity” and not on any local flow of space. Consequently, textbook authors would have to regard the sameness of time dilation of a stationary clock in a gravity field with time dilation of a clock outside the gravity field – in motion at a speed which is exactly that of the escape velocity in the former case – as a pure coincidence without any physical significance. However, when it comes to the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution, there is no “gravity” on which the time dilation of the clock held by the tethered observer could be blamed. The force on the tethered observer (brought about by the expansion of space) cannot function as a substitute for gravity, simply because the accelerating force per unit mass the tethered observer is subject to amounts to less than 10-9 m/sec² (see below), and is therefore negligible. Even in the gravity field of a spherical mass where the gravitational acceleration is

(13c)Textbooks tend to “blame” the effect of time dilation of a stationary clock in a gravity field of a spherical mass) simply on “local gravity” and not on any local flow of space. Consequently, textbook authors would have to regard the sameness of time dilation of a stationary clock in a gravity field with time dilation of a clock outside the gravity field – in motion at a speed which is exactly that of the escape velocity in the former case – as a pure coincidence without any physical significance. However, when it comes to the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution, there is no “gravity” on which the time dilation of the clock held by the tethered observer could be blamed. The force on the tethered observer (brought about by the expansion of space) cannot function as a substitute for gravity, simply because the accelerating force per unit mass the tethered observer is subject to amounts to less than 10-9 m/sec² (see below), and is therefore negligible. Even in the gravity field of a spherical mass where the gravitational acceleration is (14)one finds that, at a given quotient rs/r (even if rs/r =1, that is, at the Schwarzschild radius where the local escape velocity v’’esc is c) and hence with an enormous time dilation of a stationary clock in the gravity field, the local gravitational acceleration g’’ is vanishingly small if r is very large. [R in (14) is the radial length measured in stationary meter sticks laid end-to-end, r is circumference of a circle divided by 2pi.]Last not least, when determining the rate of time-dilation of the tethered observer from the perspective of the Milky Way, we get from (3):

(14)one finds that, at a given quotient rs/r (even if rs/r =1, that is, at the Schwarzschild radius where the local escape velocity v’’esc is c) and hence with an enormous time dilation of a stationary clock in the gravity field, the local gravitational acceleration g’’ is vanishingly small if r is very large. [R in (14) is the radial length measured in stationary meter sticks laid end-to-end, r is circumference of a circle divided by 2pi.]Last not least, when determining the rate of time-dilation of the tethered observer from the perspective of the Milky Way, we get from (3): (14a)Although the tethered observer is at rest with respect to the Milky Way, the rate of his or her time dilation is determined by a velocity, and by nothing else. Given there is only vacuum around him or her, it can only be the velocity of space itself that is the cause of his or her time dilation.Things cannot be different when it comes to the case of a stationary clock in the gravity field of a spherical mass. Here, too, the local cause (required by the principle of action-by-contact) of time dilation can only be the flow of space past the respective clock. It is by means of flowing space – and by nothing else – that gravity can be ubiquitously and not only locally be transformed away (see A. Trupp, .. and A. Trupp, ...). Only thereby is it rigorously deprived of its character as a force in physics.

(14a)Although the tethered observer is at rest with respect to the Milky Way, the rate of his or her time dilation is determined by a velocity, and by nothing else. Given there is only vacuum around him or her, it can only be the velocity of space itself that is the cause of his or her time dilation.Things cannot be different when it comes to the case of a stationary clock in the gravity field of a spherical mass. Here, too, the local cause (required by the principle of action-by-contact) of time dilation can only be the flow of space past the respective clock. It is by means of flowing space – and by nothing else – that gravity can be ubiquitously and not only locally be transformed away (see A. Trupp, .. and A. Trupp, ...). Only thereby is it rigorously deprived of its character as a force in physics.- cc)

- The “flow of space” is a general concept added to General Relativity by A. Einstein a few years prior to his death (see A. Einstein, ....). It can be frame-dependent (or even dependent on the direction of the arrow of time, see A. Trupp, ). As regards frame-dependence, it resembles the flow of electromagnetic energy described by the Poynting vector: When scrutinizing an electric motor, the Poynting vector tells us that, in the reference frame of the stator, electromagnetic energy flows from the electric power source into the rotor that is yielding mechanical work. In the reference frame of the rotor (which, for reasons of simplicity, we imagine to be a straight wire that moves back and forth in transverse, straight motions), the electromagnetic energy flows from the electric power source into the stator, which, in that frame of reference, is yielding mechanical work as a consequence of the fact that the counter-force is acting on the stator over a distance and is thus doing mechanical work.

- h)

- Time-resersed sections of world lines of escaping galaxies

- i)

-

Galaxies that exist twice at the same moment in coordinate timeMoreover, the escaping galaxy exists twice at the same time in the reference frame of the Milky Way, provided the distance (of its first copy, i.e., the copy that finds itself on the near side of the horizon) from the Milky Way, is roughly more than 3/4 of the invariant distance rhoriz to the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon.It is worth mentioning (as has been pointed out by L. Susskind) that, at every second, we are crossing some other galaxy’s cosmic event horizon (which is rushing past us at velocity c). Consequently, our own world line is, at every moment that follows for us, time-reversed in the reference frame of that distant galaxy.The world line of a galaxy in case cosmic expansion is succeeded by contraction

- aa)

-

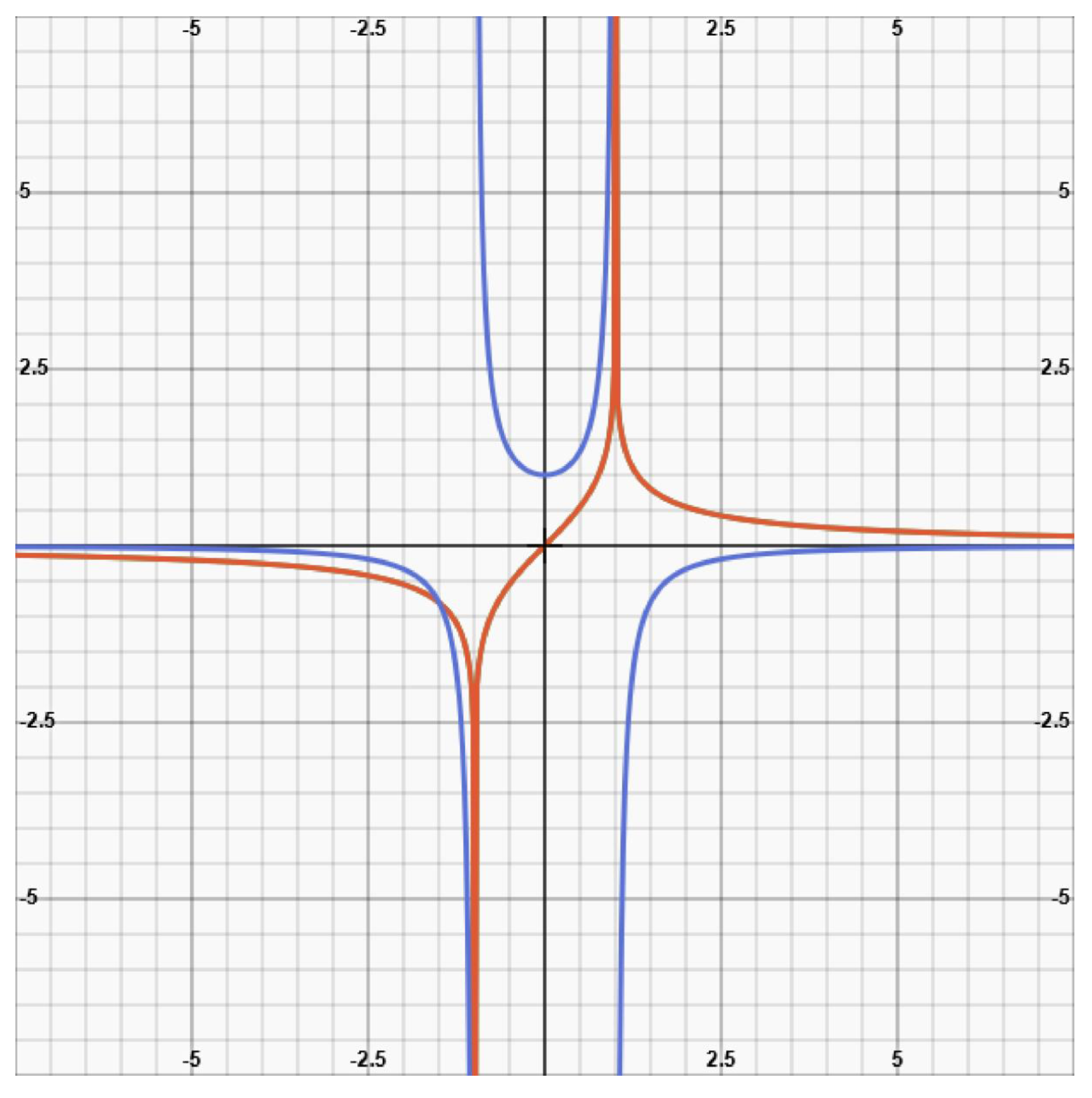

In order to convince ourselves of the fact that an escaping galaxy is capable of crossing the cosmic event horizon in the reference frame of the Milky Way (so that the continuation of the graph at regions of r>rhoriz is not just an artefact beyond the validity range of the Schwarzschild equation), we imagine the following thing to happen: We imagine that the expansion of the universe is succeeded by a contraction. One can simply assume that all motions of space and galaxies are reversed like the motion of a ping-pong ball hitting a wall (the galaxies wouldn’t feel any acceleration, as they would stay embedded in cosmic space). In the cosmic version of the Schwarzschild solution, the sign of Hubble’s constant H would have to be altered from positive to negative. That’s all. (That’s not strictly true, though: The time-coordinates of distant point-events my have jumped forward or backward as a consequence of the change of sign of H.)(6) is thus converted into:

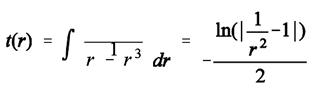

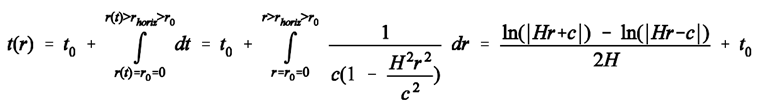

(14b)If c=1, H=1, C=0, t0=0, and if r is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the distance to the cosmic event horizon, t as expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of 14 billion years, we get:

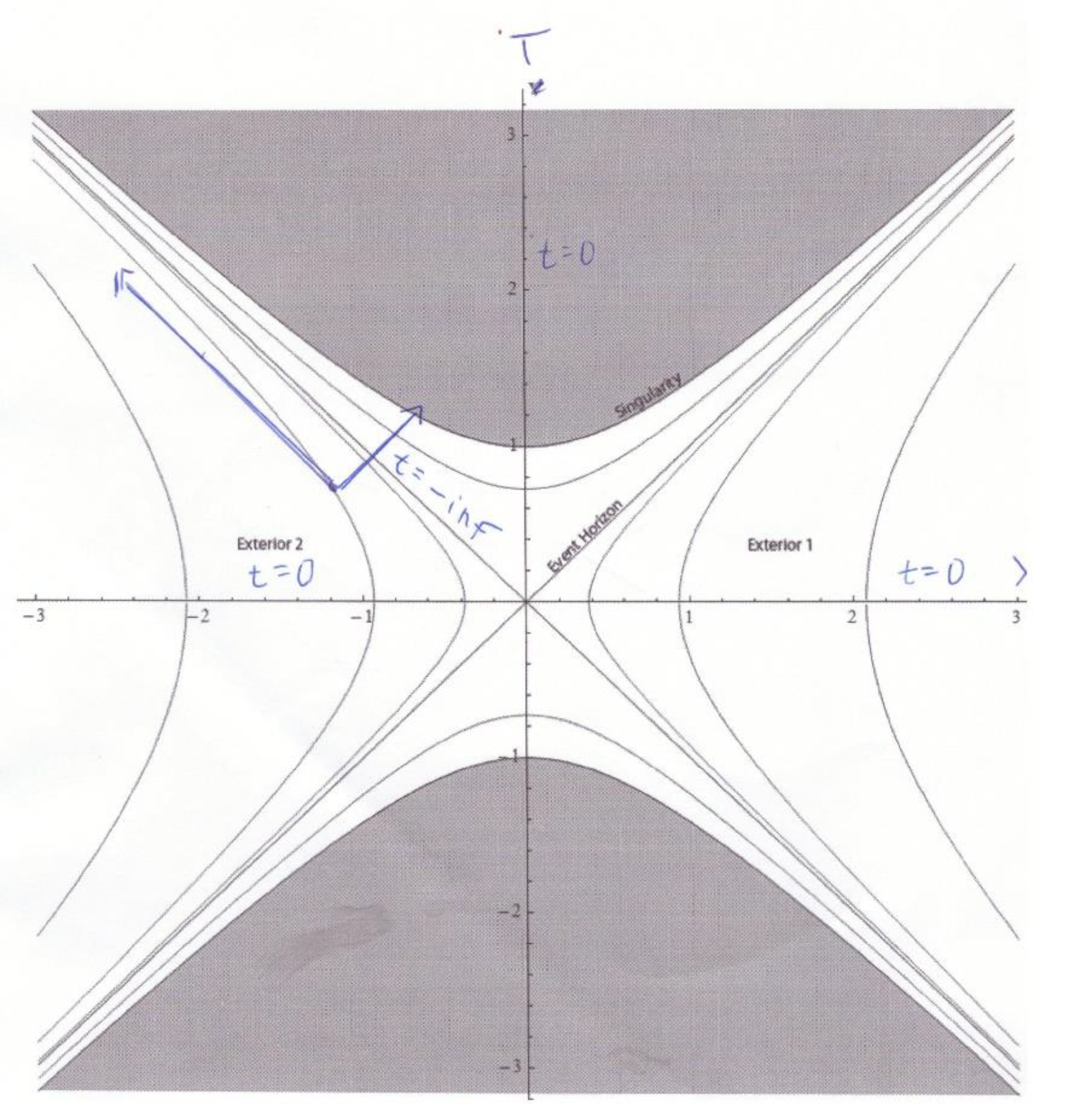

(14b)If c=1, H=1, C=0, t0=0, and if r is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the distance to the cosmic event horizon, t as expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of 14 billion years, we get: (14c)(14b) and (14c) describe the approach of a distant galaxy, and not its escape. See Figure 1b for a visualization of (14c).Thus, after billions of years, the galaxy that began its trip when it had been located close to the Milky Way is back at the location close to the Milky Way where it once had been. Given that all processes in nature are reversible, such an assumption is permissible.

(14c)(14b) and (14c) describe the approach of a distant galaxy, and not its escape. See Figure 1b for a visualization of (14c).Thus, after billions of years, the galaxy that began its trip when it had been located close to the Milky Way is back at the location close to the Milky Way where it once had been. Given that all processes in nature are reversible, such an assumption is permissible. - bb)

- When comparing their clocks with each other, observers in the Milky Way and in the once distant (and now again nearby) galaxy would find that proper time has elapsed at the same rate in both galaxies. This was shown above already. See again (12), which reads:

(14d)

(14d)II. Symmetry of the World Line of a Trans-Horizon Radio Signal That Has a Time-Reversed Section

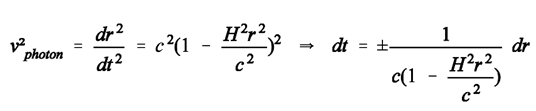

(15)

(15) (15a)

(15a) (16)

(16) (16a)

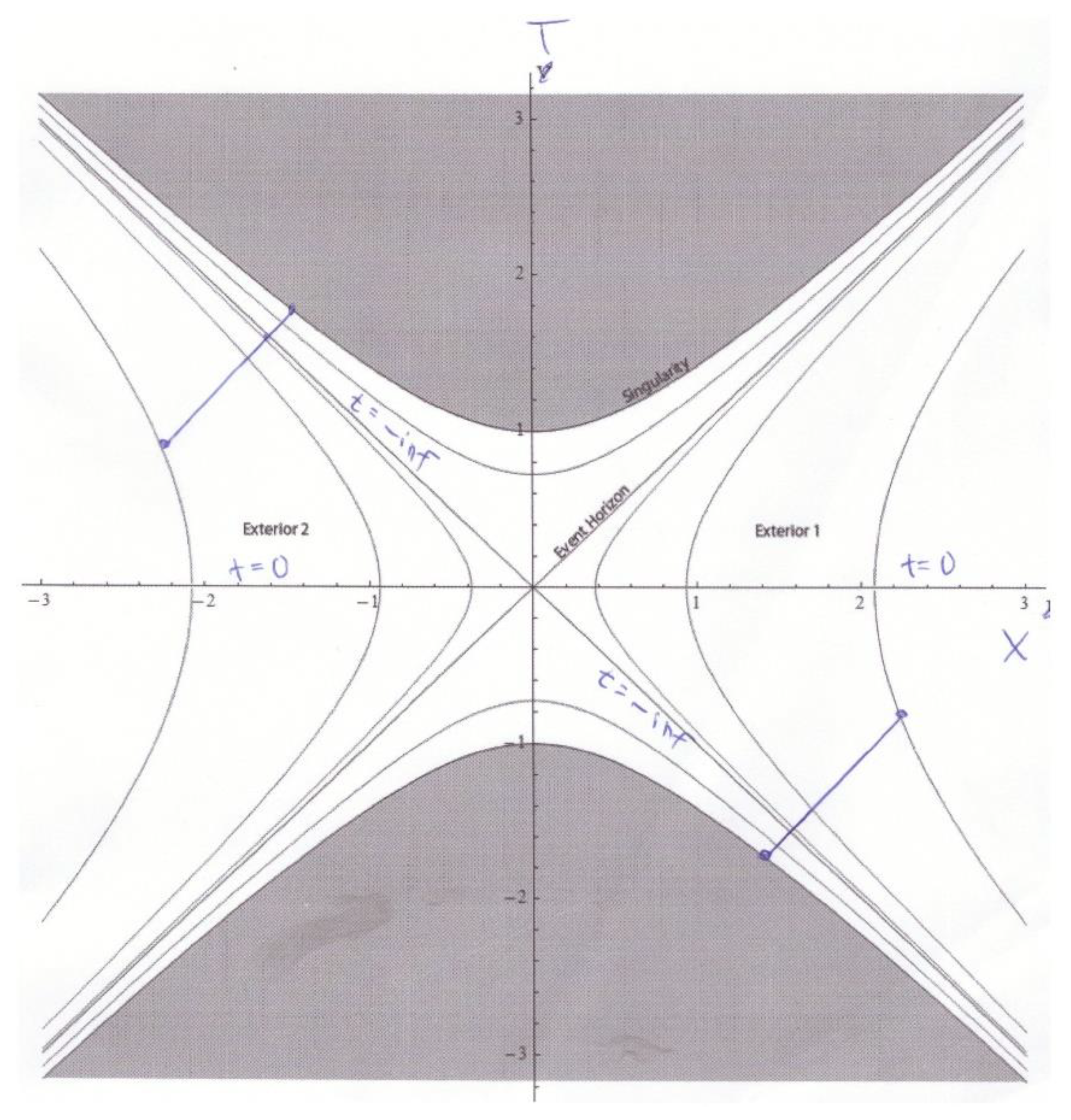

(16a)III. Why Kruskal Charts Do Not Object to the Possibility of a Photon’s Trip Back and Forth Across the Cosmic Event Horizon, but Rather Yield a Symmetry

- a)

-

Kruskal-Szekeres charts as means of depicting both variants of the Schwarzschild solution

- aa)

- Given that all textbooks assert that it is impossible even for a photon to cross the Schwarzschild horizon from the inside to the outside, and given the cosmic event horizon is the analogue to the Schwarzschild horizon when it comes to the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution, how can it be that the above results (regarding the crossing of the cosmic event horizons back and forth) can nevertheless be yielded by the Schwarzschild solution?

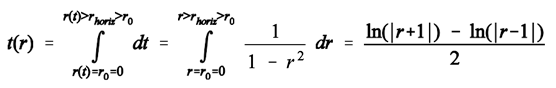

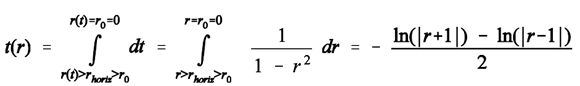

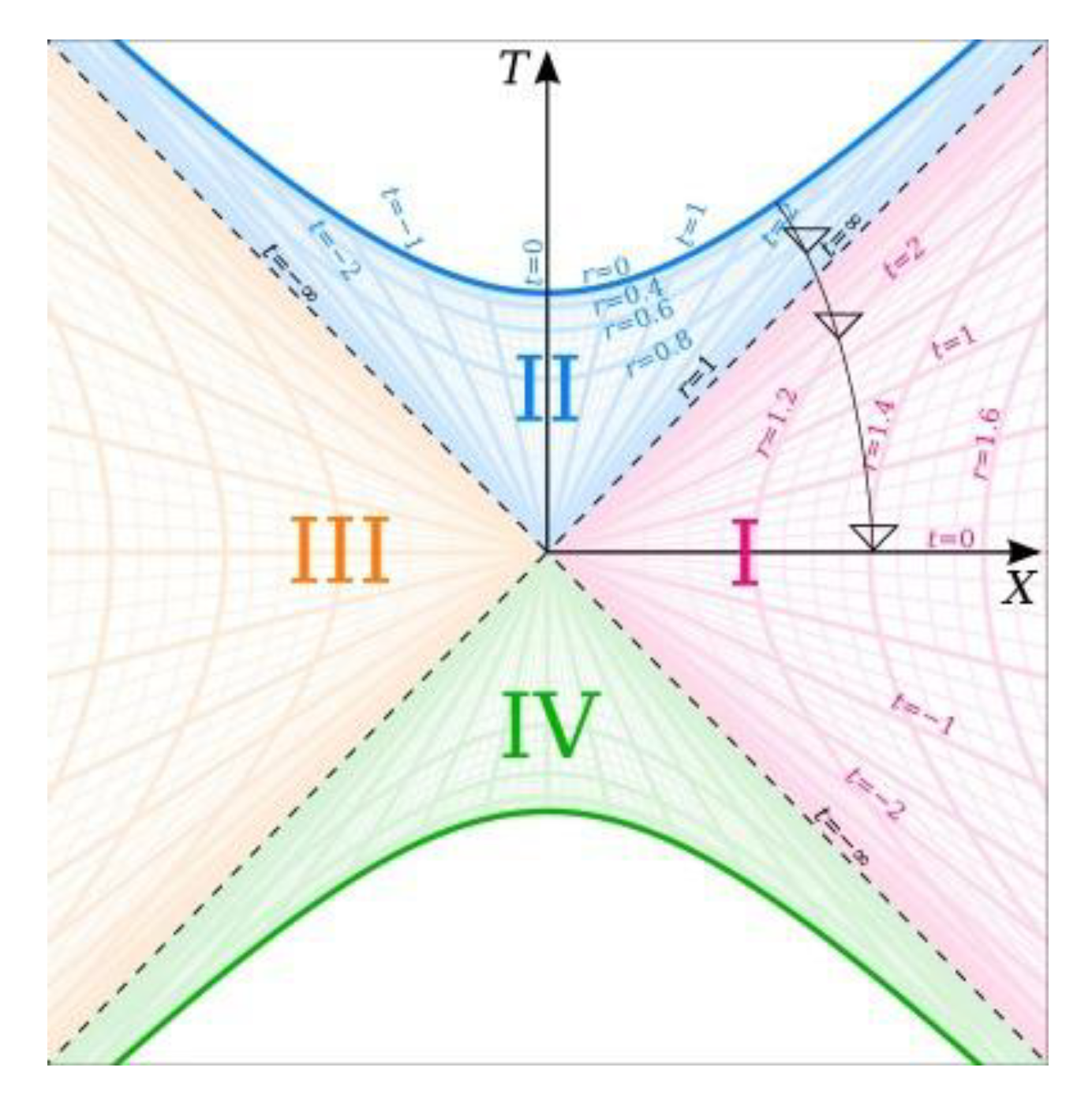

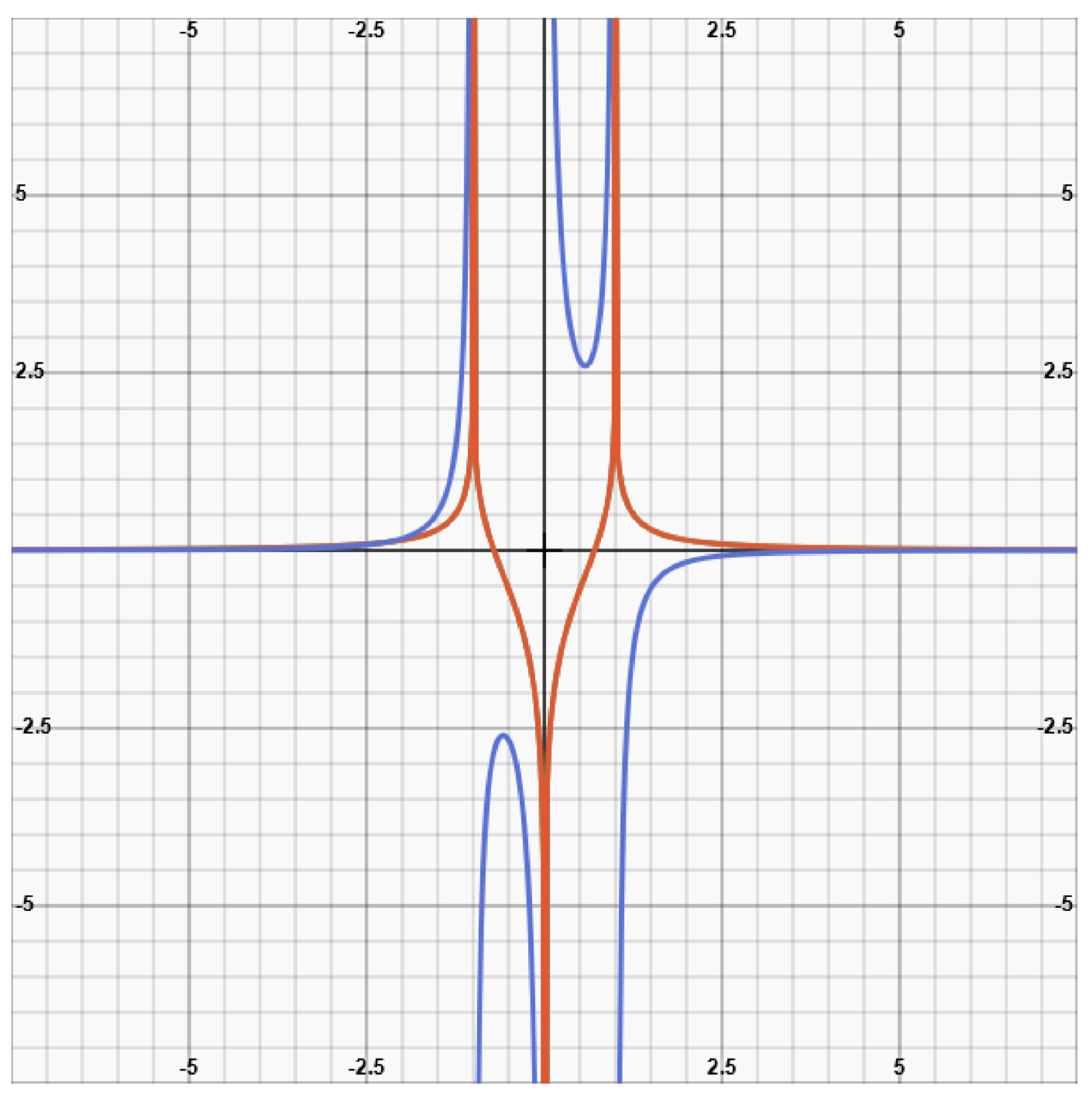

The answer is as follows:For reasons displayed below, textbooks convert the Schwarzschild equation (which uses spherical coordinates) into a so-called Kruskal chart that uses special coordinates. When using a Kruskal chart, the coordinates t and r – which appear in the equation of the Schwarzschild solution for a spherical mass, and which are the coordinates of the observer Bob who sits outside of the gravity field – are substituted by new variables T (ordinate) and X (abscissa). The transformation goes like this: (17)The above transformation rule is used for regions outside the Schwarzschild radius of Black Holes, that is, for r>1. The spatial coordinate r is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the Schwarzschild radius rs =2MG/c². The temporal ccordinate t is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the time needed for a photon to cover the distance rs in flat spacetime, that is, t is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of rs/c.For regions inside the Schwarzschild radius (r<1), the following transformation rule is used:

(17)The above transformation rule is used for regions outside the Schwarzschild radius of Black Holes, that is, for r>1. The spatial coordinate r is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the Schwarzschild radius rs =2MG/c². The temporal ccordinate t is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the time needed for a photon to cover the distance rs in flat spacetime, that is, t is expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of rs/c.For regions inside the Schwarzschild radius (r<1), the following transformation rule is used: (18)All motions described by the Schwarzschild solution shall be restricted to straight-line motions in the equatorial plane. As a consequence, d tau and d phi are both zero, and no transformations of these variables that appear in the Schwarzschild solution are necessary.Figure 2c. A Kruskal-chart taken from Wikipedia. The numbering I, II, III, IV does not match with the numbering of quadrants used in this article.Figure 2c. A Kruskal-chart taken from Wikipedia. The numbering I, II, III, IV does not match with the numbering of quadrants used in this article.

(18)All motions described by the Schwarzschild solution shall be restricted to straight-line motions in the equatorial plane. As a consequence, d tau and d phi are both zero, and no transformations of these variables that appear in the Schwarzschild solution are necessary.Figure 2c. A Kruskal-chart taken from Wikipedia. The numbering I, II, III, IV does not match with the numbering of quadrants used in this article.Figure 2c. A Kruskal-chart taken from Wikipedia. The numbering I, II, III, IV does not match with the numbering of quadrants used in this article. Every point in the t,r-plane of the t,r-chart is thus attributed a point in the T,X-plane of the T,X-chart. More precisely: Every point in the t,r-plane appears to be attributed four points in T,X-plane! This is because of the plus-or-minus sign in front of each of the two square roots, one appearing in the equation for X, the other one appearing in the equation for T. But given that t comes with a positive and a negative sign (different from r that has a positive sign only), and given that a single point in the T,X-plane shall not be a representation of more than one single point in the t,r-plane, every point in the t,r-plane can only be attributed two points in the T,X-plane. If there were four points, a positive T for a positive t could not be distinguished from a positive T for a negative t of the same magnitude. The impossibility would arise whenever the positive sign in front of the square root were chosen in case of a positive t, and the negative sign in front of the square root were chosen in case of a negative t of the same magnitude. The same would apply to X, and one single point in the T,X-plane would stand for two points in the t,r-plane.As a consequence, the combinations + + and - - (and no other combinations) are chosen in front of the two square roots in the pair of equations for T and X by most authors. This choice makes it possible to draw the totality of “lines of constant t” as a bundle of straight lines through the origin of the T,X-coordinate system, without a necessity to change their signs when passing through that origin. Moreover, straight “lines of constant t” then all have positive numerical values in the region that is defined by the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) positive Y-axis (quadrant I). Their range is from zero – along both the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) positive Y-axis – to positive infinity along the diagonal between these two axes. Similarly, the numerical values of straight “lines of constant t” are all negative between the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) negative Y-axis. Their range is from zero – along both the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) negative Y-axis – to negative infinity along the diagonal between these two axes.One should note that T does not represent physical time. Instead, it is just a variable that bears some resemblance to time. Similarly, X does not stand for spatial (radial) distance, but is just a variable that bears some resemblance to spatial distance.

Every point in the t,r-plane of the t,r-chart is thus attributed a point in the T,X-plane of the T,X-chart. More precisely: Every point in the t,r-plane appears to be attributed four points in T,X-plane! This is because of the plus-or-minus sign in front of each of the two square roots, one appearing in the equation for X, the other one appearing in the equation for T. But given that t comes with a positive and a negative sign (different from r that has a positive sign only), and given that a single point in the T,X-plane shall not be a representation of more than one single point in the t,r-plane, every point in the t,r-plane can only be attributed two points in the T,X-plane. If there were four points, a positive T for a positive t could not be distinguished from a positive T for a negative t of the same magnitude. The impossibility would arise whenever the positive sign in front of the square root were chosen in case of a positive t, and the negative sign in front of the square root were chosen in case of a negative t of the same magnitude. The same would apply to X, and one single point in the T,X-plane would stand for two points in the t,r-plane.As a consequence, the combinations + + and - - (and no other combinations) are chosen in front of the two square roots in the pair of equations for T and X by most authors. This choice makes it possible to draw the totality of “lines of constant t” as a bundle of straight lines through the origin of the T,X-coordinate system, without a necessity to change their signs when passing through that origin. Moreover, straight “lines of constant t” then all have positive numerical values in the region that is defined by the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) positive Y-axis (quadrant I). Their range is from zero – along both the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) positive Y-axis – to positive infinity along the diagonal between these two axes. Similarly, the numerical values of straight “lines of constant t” are all negative between the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) negative Y-axis. Their range is from zero – along both the (horizontal) positive X-axis and the (vertical) negative Y-axis – to negative infinity along the diagonal between these two axes.One should note that T does not represent physical time. Instead, it is just a variable that bears some resemblance to time. Similarly, X does not stand for spatial (radial) distance, but is just a variable that bears some resemblance to spatial distance.- bb)

- In order to transform the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution into the parameters T,X of a Kruskal-chart, r is simply replaced by 1/r², with r now expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the distance from the Milky Way to its cosmic event horizon. The variable t is unchanged in the transformation equations, but is now expressed in dimensionless units of multiples of the time needed for a light pulse sent off from the Milky Way to reach the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon if the speed of light did not slow down in the Milky Way’s frame of reference.

- b)

- Special characteristics of Kruskal-charts

- a)

-

When confining our attention to the area between the horizontal, positive X-axis and the vertical, positive T-axis (quadrant I) of the new chart, we find: “lines of same (positive) r“ arise from the horizontal, positive X-axis at right angle, and form curves that assymptotically approach the diagonal (between the vertical, positive T-axis and the horizontal, positive X- axis). The diagonal line (that bisects the right angle between the vertical T-axis and the horizontal X-axis) is identical with the “line of same r=1” (with r =1 denoting the Schwarzschild radius in the spherical-mass case we are considering here).There are other curved “lines of same (positive) r” which do not originate on the (positive) horizontal X-axis, but originate on the vertical (positive) T-axis. They form curves that asymptotically approach the diagonal from the other side. The uppermost of these lines is the “line of same r=0".

- bb)

- As has already been said, there exist lines of “same coordinate time t” (=Bob’s time, who sits outside of the gravity field in the spherical-mass case). Those lines are straight lines all of which run through the origin of coordinates. The horizontal, positive X-axis coincides with the line of “same coordinate time t=0". The diagonal line (which also represents the line of “same r=rs“) coincides with the line of “same coordinate time t= +inf ”. The vertical, positive T-axis coincides with the line of “same coordinate time t=0" (as does the horizontal, positive X-axis).

- cc)

- An important feature of a T,X-diagram is the following: Measuring counter-clockwise, the world-line of a radial light pulse forms an angle (with the X- axis or one of its parallels of the diagram) of 45°, or of 45°+90°= 135°, respectively. Hence, the world-line of an infalling photon that is generated at t=0 and thus orginates on the positive horizontal X-axis of the chart (provided that r, that is, the spatial location where the photon is “born”, is larger than unity) has a slope of 90°+45° = 135°. It intersects the line that bisects the angle formed by the positive X-axis and the positive T-axis, that is, the Schwarzschild horizon (r=1) at right angle. The coordinate time t (Bob’s time) of this crossing of the Schwarzschild horizon is positive infinity. Beyond the Schwarzschild horizon, the photon’s straight world line in the T,X-chart then intersects “lines of same coordinate time t” with declining numerical values of coordinate time t , until the world line reaches the curved line that stands for r=0.

- dd)

- Why are Kruskal-charts considered to be useful? Their usefulness is commonly seen as lying in the fact that, different from the world line of a photon in a t,r-diagram, the world line of the infalling photon on the Kruskal chart is not infinitely long, and has no points or disruptions, not even where it intersects the r=rs-line.

- c)

- The world line of photon that falls into a black hole (as it presents itself in a Kruskal- chart)

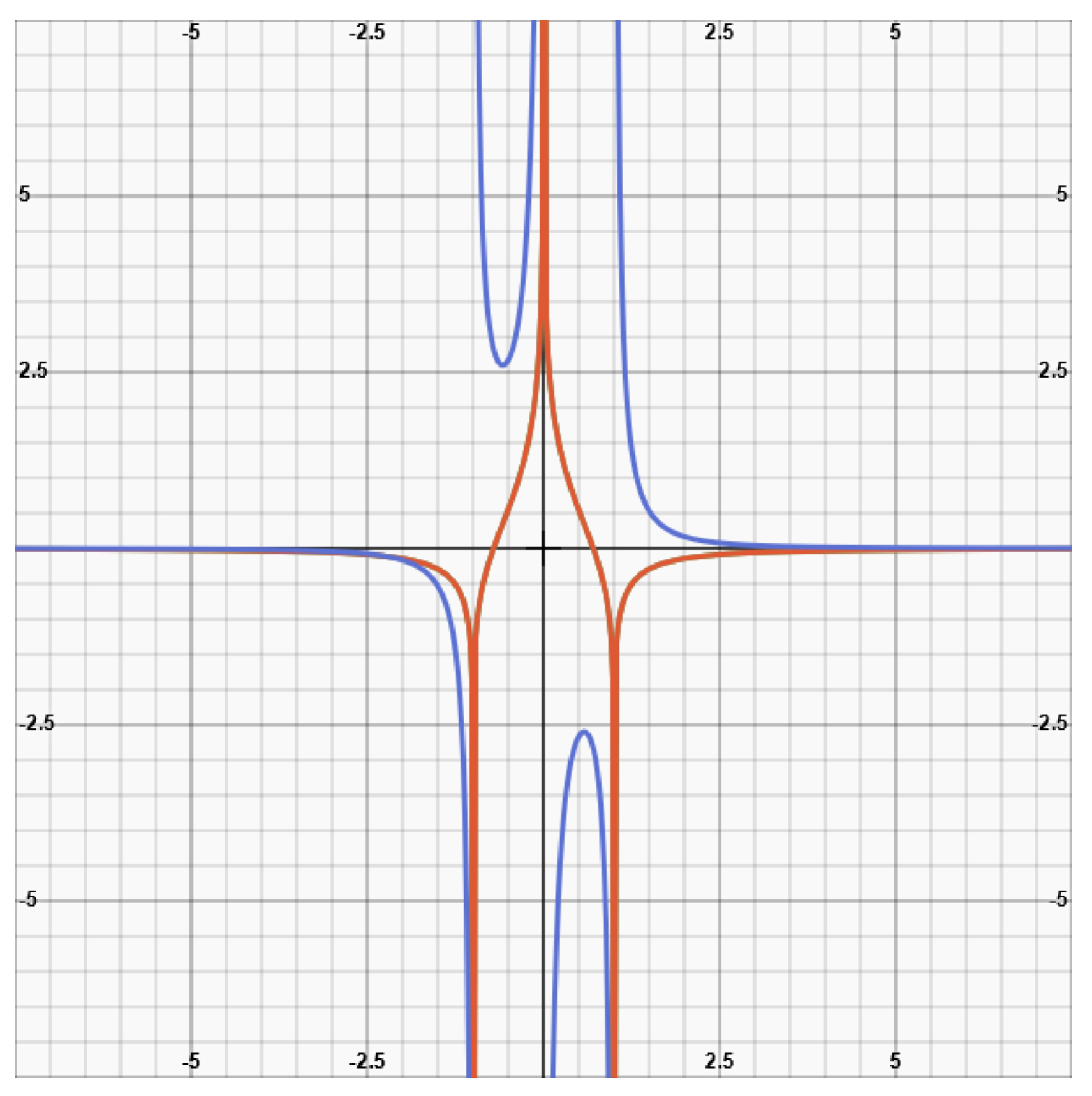

(19)

(19) (20)

(20)- d)

- The world line of photon that rises from a black hole (as it presents itself in a Kruskal-chart)

(21)

(21)- e)

-

A wrong way of using Kruskal-charts

- aa)

-

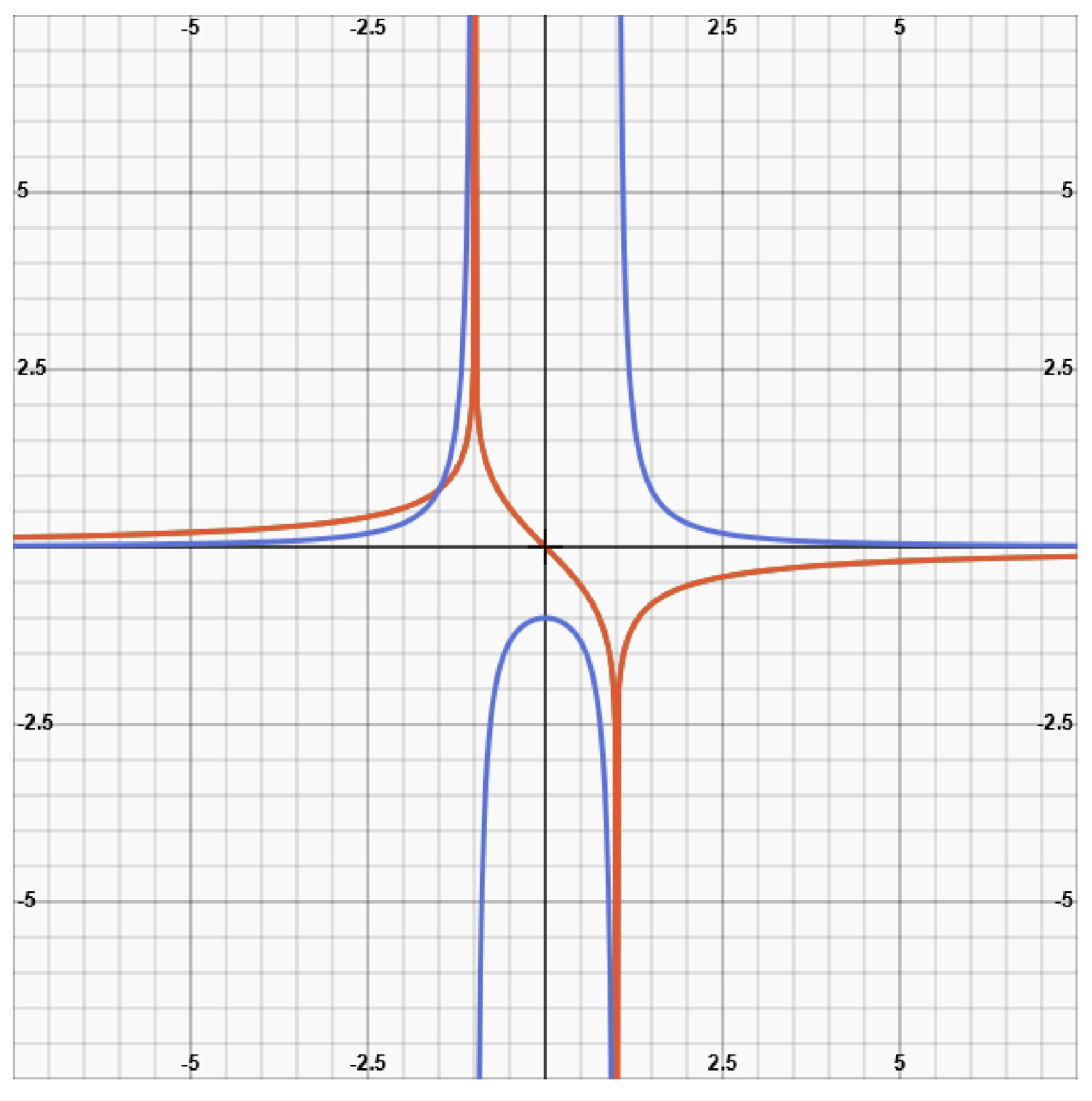

Now comes the crucial point: It is commonly believed that the world-line of an outbound photon that is “born” in the interior of a black hole at r<rs can (and must) be pictured as a straight line in the same sector of the Kruskal chart which is used for representing the infalling photon. That sector is the one defined by the positive horizontal abscissa (positive X-axis) and the positive vertical ordinate (positive T-axis), that is, quadrant I. The result is shown in Figure 4.The world-line of an outgoing photon and that of an ingoing photon are supposed to form an angle of 90° in the chart (so called “forward lightcone”). The world line of the “outgoing” photon that starts at t=0 and r=0 is thus supposed to form a 45°-angle with the horizontal, positive X-axis (measured in an anti-clockwise direction), and therefore ends up at r=0, right where it started. It has zero-length and thus appears to never approach the Schwarzschild horizon at r=rs .In case the outbound photon starts at 0<r<1 (and not at r=0), say, at r=0.8 and t=1, the fate of the photon appears to be the same. See Figure 4. The photon’s world line is then supposed to form a parallel to the “line of same r=1" (Schwarzschild radius). That parallel is doomed to eventually meet the “line of same r=0" near the upper right corner of the T,X-chart.L. Susskind / A. Cabannes (2023) (Figure 17, p. 232/233) recently expressed this widespread belief as follows:“Remember, in the coordinates that we are using, light moves with a 45° angle. Therefore light cannot escape from the upper quadrant in figure 17. All it can do is eventually hit the singularity [at r=0]. And anything that is moving slower than the speed of light has a slope closer to the vertical, and will also hit the singularity. Consequently, anybody who at some point is in the upper quadrant is doomed. Figure 17, and its variants figures 15 and 16, are pictures you should familiarize yourself with, until they no longer have any secrets. If you want to understand and be able to resolve weird paradoxes about who sees what in the black hole, I recommend that you always go back to these diagrams.”

- bb)

-

But this is clearly at odds with (21), which tells us that the outgoing photon does approach the Schwarzschild horizon asymptotically (see above).To insist, as textboold do, that it is quadrant I (defined by the vertical, positive T-axis and the horizontal, positive X-axis) where the world-line of an outgoing photon has to be placed, is as irrational as it would be to insist that it is quadrant II (defined by the vertical, positive T-axis and the horizontal, negative X-axis) where the world-line of an INGOING photon has to be placed (see Figure 5): If doing the latter, the result would be that the photon would be going backward in time outside of the Schwarzschild horizon, no matter whether the world-line forms a 45°-angle or a 45°+90°= 135°-angle with the horizontal in the Kruskal-chart.

- cc)

-

It still gets worse for the common interpretation of Kruskal-charts: Even Susskind and others would concede that the world-line of an object that does not move at all coincides with a “line of constant r”. Quadrant I (defined by the vertical, positive T-axis and the gorizontal, positive X-axis) is bisected by the diagonal that represents a “line of same r=1", that is, the Schwarzschild horizon. In the area defined by the diagonal (line of Schwarzschild horizon) and the vertical, positive T-axis, any short straight piece of a curved “line of constant r” is, in terms of angle width, farther away from the vertical (in a clockwise direction) than just 45°. A curved line – originating on a “line of constant r” – that is a tiny bit farther away from the vertical (in terms of angle width) than the “line of constant r” on which it orginates represents a world line of an outbound object which is moving between two different “lines of constant r “. That curved line represents a motion of an object as slow as one wishes it to be (so that its behaviour might be almost indistinguishable from complete rest). As has already been stated, it has a slope of more than just 45° (measured from the vertical in a clockwise direction). That slope is thus larger than the slope of the postulated world-line of an outgoing photon, which is thought to be 45° from the vertical. But “anything that is moving slower than the speed of light” cannot have a slope closer to the vertical and also farther from the vertical in comparison with the slope of the world line of an outgoing photon. (The terms “ingoing” and “outgoing” refer to space outside of the Schwarzschild horizon.) Hence, the use of quadrant I for the representation of an outgoing photon leads to an inner contradiction.This inconsistency extends to the case of Kruskal-charts being used in connection with thecosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution.

- dd)

- Consequently, contrary to what L. Susskind and A. Cabannes are saying (in accordance with all textbooks on Black Holes), their diagram 17 is not crucial for a correct understanding of what Black Holes and the cosmic event horizons are. Instead, that kind of diagram is responsible for a long-standing, complete misconception regarding Black Holes and cosmic event horizons.

- d)

-

How to use Kruskal-charts correctly for regions beyond event horizons

- aa)

- The just described error is rooted in the disregard for the following rule: The sector defined by the positive, horizontal abscissa and the positive, vertical ordinate of the Kruskal chart (quadrant I) can only be used for inbound objects (traveling into the Black Hole), not for outbound ones. For outbound light signals or other objects, a different quadrant of the chart has to be used: either the quadrant defined by the vertical, negative T-axis and the horizontal, positive X-axis, or the quadrant defined by the vertical, positive T-axis and the horizontal, negative X-axis (see above). Then the result given by (19) or (20) for an outgoing light pulse is reproduced by the Kruskal chart (as it should).

- bb)

- In other words: According to (21), an outbound photon originating beyond the Schwarzschild horizon (at r=0 and t=0) approaches the Schwarzschild horizon at infinitely negative time t. But a line of infinitely negative time t is not available in the quadrant defined by the vertical, positive T-axis and the horizontal, positive X-axis of a Kruskal-chart (quadrant I). It is available, though, in the quadrant defined by the vertical, negative T-axis and the horizontal, positive X-axis of a Kruskal-chart (quadrant IV). In addition, it is available in the quadrant defined by the positive, vertical T-axis and the horizontal, negative X-axis (quadrant II). This is shown in Figure 6.

- e)

-

The absence of a singularity beyond the cosmic event horizon and also at r=0 in the interior of black holes

- aa)

-

It has been shown that there is no room for drawing the world-line of an outbound photon in the quadrant defined by the vertical, positive T-axis and the horizontal, positive X-axis (quadrant I). This is why the assertion according to which no object or signal, not even a photon, may leave the interior of a black hole, is evidently wrong.And so is the assertion of a singularity at r=0, according to which all world-lines of all objects beyond the Schwarzschild horizon, even of those that try to leave the black hole, end up at r=0. In other words: There is no such thing as a singularity at r=0.

- bb)

-

When doing things correctly, the world-line of an outgoing photon is symmetrical with respect to the world line of an ingoing photon, just as it should be due to the principle of reversibiliy of any light path.In other words: The common but wrong interpretation of Kruskal charts is incompatible with the principle of “reversibility of any light path”. By contrast, the correct use of Kruskal charts gives due consideration to that principle.

- cc)

- All of what has said with regard to the spherical-mass variant of a Kruskal chart applies to the cosmic variant of that chart as well. This is what is to be highlighted.

- dd)

- It is worth noticing that R.P. Kerr (2023) recently made similar objections to the usual interpretation of Kruskal charts [as did A. Trupp (2020)].

- ee)

- As regards the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution, Kruskal charts postulate no singularities either. This is obvious for symmetry reasons already: Otherwise a cosmic event horizon could not be a relative thing, but would be absolute. But this would entail that a certain point in space is privileged over others places, and would thus violate the symmetry rule.

IV. Cross-Check of the Obtained Result by Means of a Thought Experiment

V. Loop-Shaped World Lines of Objects Crossing the Cosmic Event Horizon Back and Forth

- a)

- The possibility of loop-shaped world lines

- b)

-

Consequences of looped-shaped world lines: Copies of persons and things

- aa)

- As Gödel had correctly pointed out when he introduced his special universe, a loop- shaped world line is proof of the static model of time, according to which present, past and future events occurring at the same spatial location are equally part of physical reality as are events occurring at the same time at different places.

- bb)

- Moreover, in the face of the now emerging grandfather’s paradox, we find that General Relativity leads to two alternative outcomes: As a first possibility, returning Alice is prevented from destroying her former self (when crossing her own world line) by some mysterious mechanism which science has not yet detected. But alternatively, it could well be that the phenomenon of a choice between alternatives – that humans think they are capable of making – requires and is thus proof of the existence of multiple worlds. Hence, when returning Alice decides to destroy her former self (upon crossing her own world line), that destruction happens in a parallel world only, so that Alice is acting on a copy of herself.

- c)

- The possibility of creating loop-shaped world lines of material objects in our vicinity and of copies of themselves

VI. Results

- -

- In the cosmic variant of the Schwarzschild solution (expanding space), world lines of objects and even persons may exist that are capable of crossing the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon back and forth. This constitutes a first symmetry.

- -

- The part of the world line of such an object (crossing the cosmic event horizon) which extends beyond the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon is time-reversed in the reference frame of the Milky Way. The cosmic event horizon thus acts as a symmetry line of a special kind (second symmetry).

- -

- All persons and objects on earth exist twice in the reference frames of some of those galaxies which find themselves beyond the Milky Way’s cosmic event horizon. This constitutes another strange symmetry (third symmetry).

- -

- Loop-shaped world lines of traveling objects or even persons that cross the cosmic event horizon of a distant galaxy back and forth are allowed to exist even in our neighborhood. The arrows of time along world lines may thus come in two opposite directions. This constitutes a fourth symmetry. It also corroborates the static model of time.

- -

- Kruskal-charts do not obstruct these results. This is because the first quadrant of a T,X- Kruskal chart may only be used for world lines (crossing an event horizon) of outbound photons or other objects, that is, photons or other objects sent off by an observer towards an event horizon. As regards photons or other objects that cross the event horizon in order to reunite with the observer, the second and/or the fourth quadrant – and not the first one – of a Kruskal chart has to be used. This guarantees a complete reversibility – and hence a form of symmetry – of any light path across event horizons. It constitutes a fifth symmetry.

- -

- There is no such thing as a singularity behind an event horizon; neither in the case of black holes, nor in the case of the cosmic event horizons.

References

- Boehmer, Stuart, Tolman’s paradox and the proper treatment of time in relativistic theories, Physics Essays, Vol. 30, 3 (2017), pp. 239-242. [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, Stuart, Supplementary Conditions on solutions of Einstein field equations, uploaded to Academia, 2024.

- Deutsch, D. (1997), The Fabric of Reality. 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. (2018), Doc 31: Ideas and Methods, II, The Theory of General Relativity, in: Janssen, Michel / Schulmann, Robert / Illy, József / Lehner, Christoph / Buchwald, Diana (eds.), The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein. Volume 7: The Berlin Years: Writings, 1918-1921 (English translation supplement) (Digital ed.), California Institute of Technology, retrieved 15 April 2018;

- Gaztanaga, E. (2022), The Cosmological Constant as Event Horizon, Symmetry. 2022; 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gödel, K. (1949), An Example of a New Type of Cosmological Solutions of Einstein’s Field Equations of Gravitation, Reviews of Modern Physics, Vol. 21, 3 (1949), pp. 447-450. [CrossRef]

- Kerr, R.P. (2023), Do Black Holes have Singularities?, arXiv:2312.00841v1 [gr-qc] 1 Dec 2023;

- Misner, Ch. W, Thorne, K.S., Wheeler, J.A. (1973), Gravitation; 1973.

- Susskind, L. , Cabannes, A. (2023), General Relativity – The Theoretical Minimum. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Trupp, A. (2020), Traversing a black-and-white hole in free fall and rise, Physics Essays, Vol. 33, 4 (2020), pp. 460-465. [CrossRef]

- Trupp. A. (2022), What the Covariant and Ordinary Divergences of the Tensors in Einstein’s Field Equation Tell about Newton’s Apple When it Hits the Ground, Advanced Studies in Theoretical Physics, Vol. 16, 2022, no. 4, 239 - 257. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).