1. Introduction

Micronutrient deficiency is a worldwide public health problem and remains an economic burden. Micronutrients such as iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin A, thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, folate, and vitamin B12 are essential for all forms of life to sustain optimal physiological function. Shortages of these essential nutrients pose a significant global health concern. Also, such deficiencies can lead to inadequate physical and mental growth in children, increased susceptibility to or worsening of diseases, cognitive disabilities, vision impairment, and reduced overall productivity and potential [

1]. Estimates suggest that over half of preschool-aged children and about two-thirds of non-pregnant women of reproductive age globally experience micronutrient deficiencies [

2].

Plant-based diets are gaining popularity worldwide, and legumes like lentils, chickpeas, dry peas, beans, and faba beans play a significant role as dietary protein sources. In many countries, vitamin B12, calcium, folate, and other vitamins and micronutrients are also increasingly important for plant-based foods in vegetarian and vegan diets. Lentils are notable among legumes for their relatively high content of protein, carbohydrates, and essential micronutrients, surpassing certain staple cereals and root crops. Collectively, over 50 countries produce approximately 6.65 million tonnes of lentils globally, with Canada contributing about 50% (2.20 million tonnes) of this total [

3]. Lentils, as a type of legume, are rich in protein (25.8 to 27.1% dry weight), starch (27.4 to 47.1%), dietary fiber (5.1 to 26.6%), iron (73 to 90 mg/kg), zinc (44 to 54 mg/kg), and selenium (425 to 673 µg/kg) [

4]. Lentils are also rich in vitamin A, thiamin, folate, and β-carotene, and provide significant amounts of riboflavin, niacin, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, vitamin K, and vitamin E [

5,

6]. A combination of rice and lentils makes a popular and commonly eaten dish known as “hotchpotch” in many Asian countries, such as, in Bangladesh. This dish provides all essential amino acids, carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and several minerals and vitamins. Although lentils have a significant amount of intrinsic Fe and Zn, some antinutritional factors, such as phytate, polyphenols, calcium, and protein, can inhibit the absorption of both nutrients from food [

4]. Improving the concentration of these micronutrients and their bioavailability using a sustainable approach is a prime area for research to provide adequate micronutrients and cope with micronutrient deficiency [

7].

Various strategies are employed to address global micronutrient deficiency issues, such as biofortification, food fortification, public health interventions, supplementation, nutrition education, disease control measures, dietary diversification, and food safety measures. These approaches aim to improve the micronutrient content in crops and food products [

8,

9], and they are being implemented for various staple crops and foods globally [

10]. Among all the approaches, the fortification of staple foods is now the more widely used strategy that has a proven history of improving dietary diversity and effectively decreasing micronutrient deficiencies [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Around 125, 91, 32, 19, 12, and 7 countries have mandatory food fortification legislation for salt, wheat flour, vegetable oil, maize flour, sugar, and rice, respectively [

13].

The Crop Development Centre of the University of Saskatchewan has developed techniques and expertise in lentil fortification since 2014. A laboratory-scale protocol was initially developed for fortifying dehulled lentils using a spray application to deliver appropriate doses of iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn) fortificants. This protocol aims to establish a strategy for lentil fortification and explore methods to increase the bioavailability of Fe and Zn in the human diet [

7,

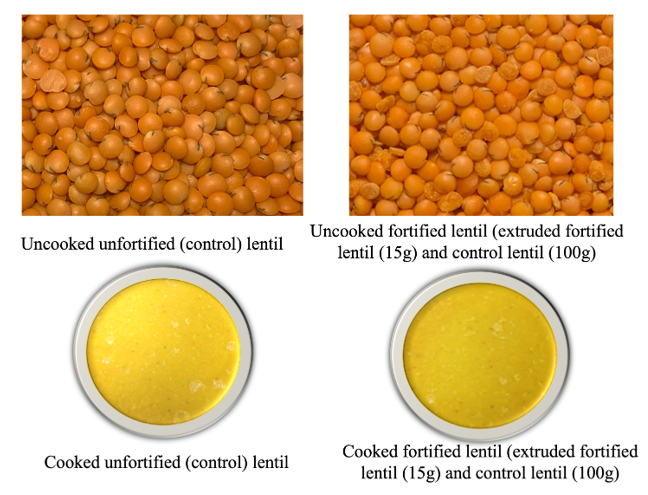

14]. To add additional essential micronutrients, a hot extrusion technology was used to expand the essential micronutrient spectrum for lentil fortification to its full nutritional potential. We developed the fortified extruded lentil analog and blended it with the unfortified dehulled lentil kernel at a 15:100 ratio to produce the multiple micronutrients fortified (MMF) lentil product (

Figure 1). In preliminary studies, we assessed the total nutritional profile, protein digestibility, colorimetric changes, and stability of micronutrients of MMF lentils after six months and one year of storage in retail market environment conditions [

15]. This study was designed to conduct an exploratory sensory evaluation of MMF lentils by lentil consumers in Bangladesh.

Sensory analysis is a multidisciplinary field encompassing various social sciences, including food science, statistics, and psychology. It captures unbiased human responses to food, aiding stakeholders in identifying brand effects [

16,

17]. Sensory tests fall into two main categories: analytical tests, which focus on the product, and affective tests, which focus on the consumer [

18]. Taste, flavor, appearance, and texture are vital organoleptic attributes in sensory evaluations of food products. The potential alteration of these attributes due to fortification can be a fascinating area of study, potentially impacting consumer acceptability. The acceptability of fortified foods depends on the type and dosage of the fortificant, the chemistry of the food vehicle, and interactions between different fortificants [

19]. Fortification can also result in a metallic taste in foods, undesirable flavors from fat rancidity, unacceptable color changes, and a decrease in the quality of vitamins (such as vitamins A and C, essential for iron absorption and utilization) [

20]. Any fortification program aims to reduce unwanted changes in food or food products. A prior study assessing consumer opinions on cooked and uncooked iron-fortified lentils (NaFeEDTA) revealed that consumers favored fortified lentils over unfortified lentils and those fortified with other iron sources [

21]. The current study expects that MMF lentils will be just as acceptable to consumers regarding taste, smell, appearance, texture, and overall appeal. We propose that fortifying lentils with multiple micronutrients significantly affects preferences for their sensory qualities. Furthermore, we suggest that there may be noticeable differences in sensory attributes between fortified and non-fortified lentils. Identifying these sensory differences could have important scientific implications for the food science industry. Consumer feedback, a valuable source of insights, plays a crucial role in guiding recommendations for food scientists and commercial food product developers. Additionally, understanding sensory acceptability can help determine the optimal baseline and limits for fortificant formulas to meet the recommended daily allowance of added micronutrients.

4. Discussion

Vitamin and mineral deficiencies affect more than a third of the world’s population. To fight the consequences of such deficiencies, relevant staple foods are chosen to be enriched with micronutrients. Lentils are one of them. Collectively, over 50 countries produce approximately 7.6 million tonnes of lentils globally, with Canada contributing about 50% (3.7 million tonnes) [

3]. Some countries that do not produce lentils rely on imports to use them as a staple food. Lentils, a cost-effective solution, are favored in daily meals for their quick cooking time and affordability as a source of protein, carbohydrates, and micronutrients compared to animal-based sources [

33]. Lentil adds complementary protein to rice-based diets, and most importantly, unlike rice, which in many countries is boiled in water and then drained from the rice, cooked lentil is consumed as a soup without draining the cooking water, and this results in maximum nutrient availability after cooking in comparison to rice [

7].

Fortifying lentils may be much more efficient because the volume of food products to achieve effective nutrition will be reduced. Many countries now accept extruded fortified rice to combat micronutrient deficiencies. Our previous study [

15] proposed a similar approach to fortify lentils with multiple essential micronutrients. The extrusion techniques for fortified lentils were similar to rice fortification, entirely different from the flour fortification used for maize and wheat. Finally, we developed a novel method of fortifying lentils with multiple vitamins and minerals (vitamins A (retinol and beta-carotene); B1 (thiamine), B3 (niacin), B6 (pyridoxine), B9 (folate), B12 (cyanocobalamin); vitamin D3; calcium, iron, and zinc) using Hot Extrusion Technology (HET) [

15]. These fortified lentils have been named multiple micronutrients fortified (MMF) lentils, and the MMF development protocol can easily merge with the existing pulse industry milling practices.

Sensory evaluation measures consumer responses regarding their liking, preference, and acceptance of food products [

34]. In this study, we assessed sensory attributes of the newly developed MMF lentils among consumers in Bangladesh. The study's overall findings showed that the mean scores for odor, taste, texture, and overall acceptability of MMF lentils were not significantly different from those of the control/unfortified lentils. This suggests that the fortification process had minimal or no impact on the sensory qualities of the MMF lentil sample, reinforcing the positive consumer response to the MMF lentils.

In this study, we also selected Bangladesh as the study site for several reasons. Lentils are a staple or semi-staple food in many countries, with 56% of the world’s lentils consumed in Asia [

17], particularly in Bangladesh. The study took place in a key lentil-growing region of Bangladesh, where farmers have extensive experience in cultivating, processing, and marketing lentils. The National Pulses Research Centre (PRC) of the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI) is also located in this region. Various national and international organizations are actively involved in the Bangladesh health sector, conducting research, sensory evaluations, and field trials with fortified foods, such as fortified rice. Dishes like “daal (pulses) and vhat (rice)” or “hotchpotch,” made with lentils and rice, are common and popular in South Asia, including Bangladesh. Approximately 60% and 12% of Bangladeshi women consume lentils three and four days per week, respectively [

34]. The similar study revealed that 92% of 384 respondents ate hotchpotch at least once a week [

34]. Over 80% of the lentils in Bangladesh are imported from countries like Australia and Canada, presenting a significant opportunity to export MMF lentil products to address micronutrient deficiencies in Bangladesh.

Moreover, food fortification is gaining momentum in Bangladesh, though the market currently offers limited options, with some products still under review. Presently, two fortified foods—vegetable oil with vitamin A and salt with iodine—are available [

35]. Research is ongoing for other fortified foods such as rice, lentils, wheat flour, and sugar [

35]. A feasibility study on Fe-fortified lentils with adolescent girls showed positive acceptance [

36]. Additionally, a large-scale, double-blind, community-based, randomized controlled trial involving around 1,200 adolescent girls demonstrated that Fe-fortified lentils significantly improved their iron status [

36].

In sensory evaluation studies, consumers are essential for assessing product differences and characteristics [

37]. The number of respondents needed for a consumer test depends on the specific food products being evaluated, the test’s purpose, duration, and cost [

38]. A sample size of 50–300 respondents is recommended for consumer acceptability tests [

39]. Suresh & Chandrashekara, (2012) [

40] provided a formula for calculating sample size, indicating that around 96 participants are sufficient for consumer-level research. This study used data from 150 participants to achieve statistically significant results.

In consumer-level sensory analysis, sociodemographic data is crucial for determining if participants accurately represent the broader population when evaluating a specific food product. Previous research has shown that sociocultural diversity, demographic factors, and economic status influence consumer choices regarding functional foods [

41]. In this study, data on participant diversity—including age, gender, monthly income, employment status, education, and attitudes toward lentil consumption—confirmed the sample’s representativeness of the general consumer population. Consumer attitudes toward lentil consumption in Bangladesh indicate a preference for red lentils over other pulses. Among the two types of red lentils, the football type is favored by 95.3% of consumers over the split type. Approximately 94% of consumers in Ishurdi purchase lentils from local markets, where they are sold in open sacs or 1–2 kg plastic bags. A previous study [

14,

23] found that 37% of urban consumers bought lentils from local markets or retail shops, likely due to sociodemographic differences between urban and suburban areas. Consumers also the MMF lentils as a value-added product that should be packaged in sealed bags to ensure quality and reduce the risk of adulteration.

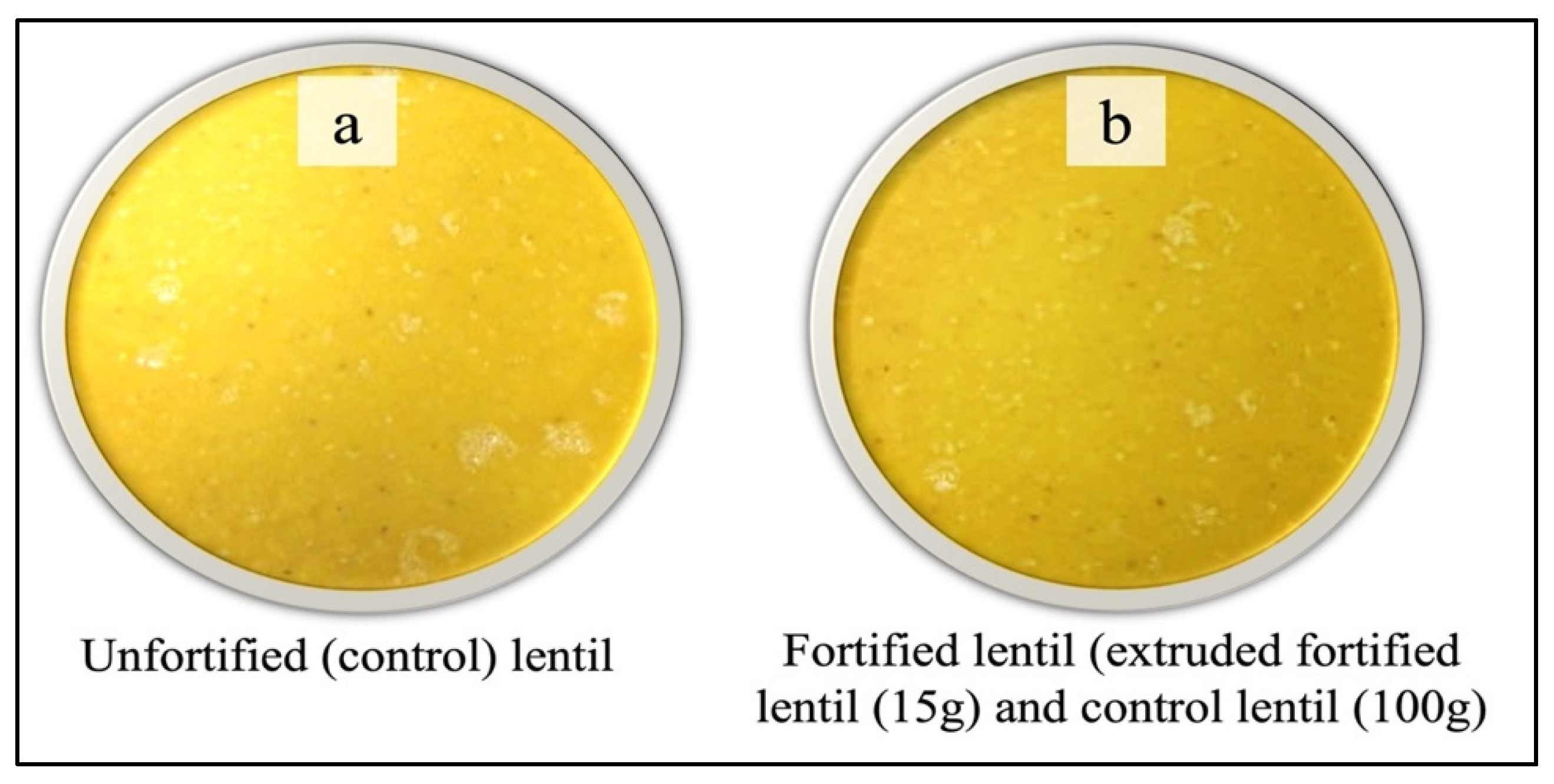

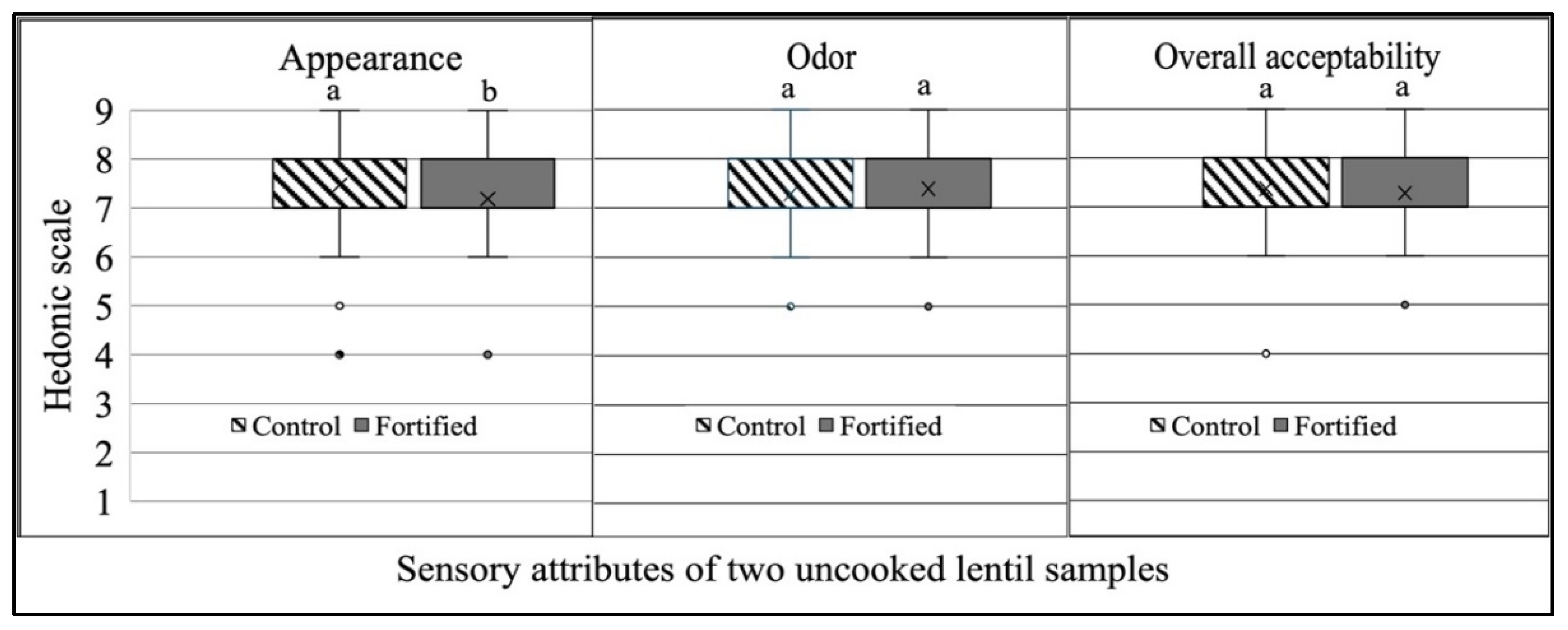

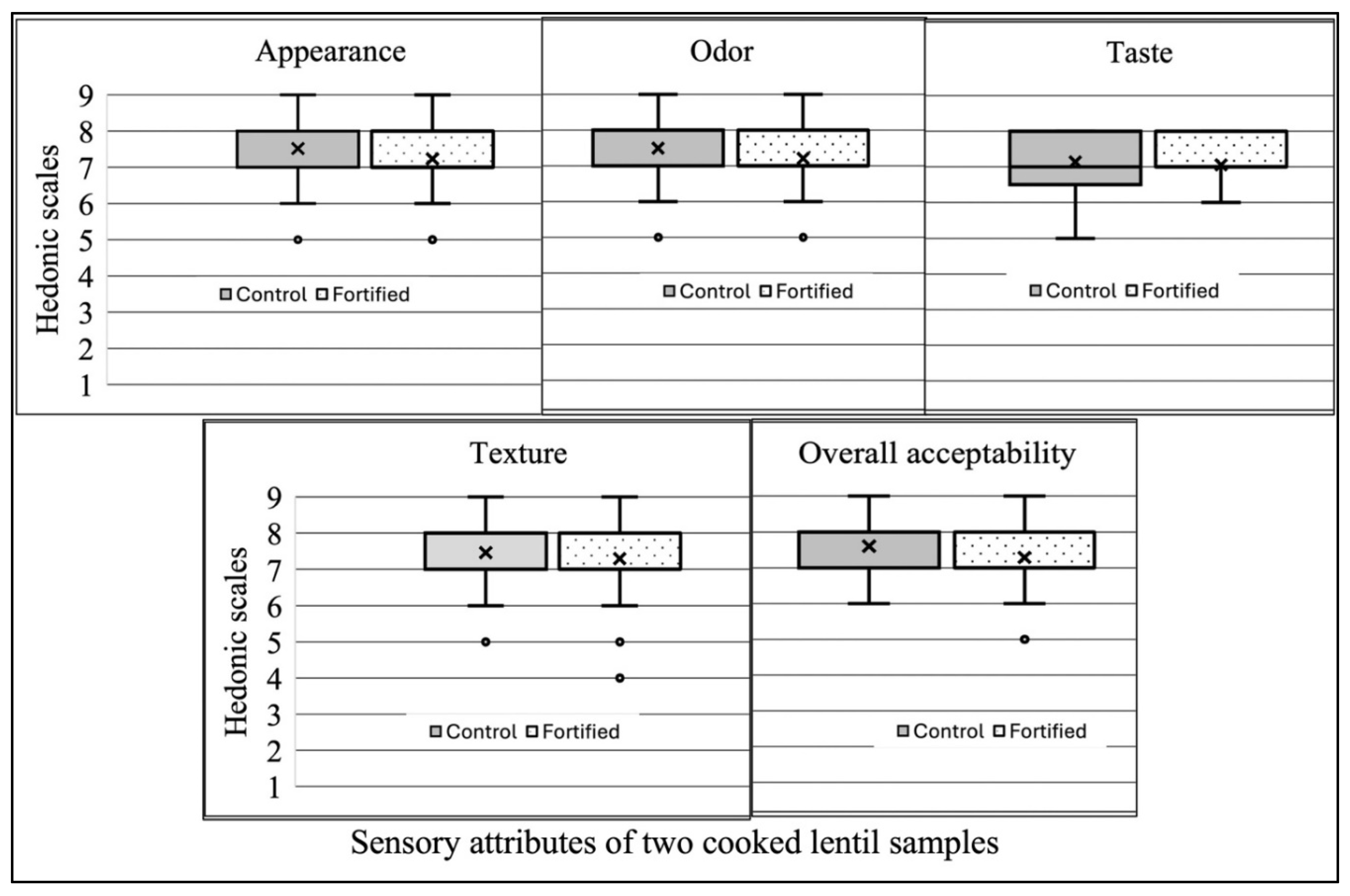

Consumer responses were significantly not different between two uncooked samples (MMF and control lentils) for all three attributes except appearance. The average sensory scores of appearances, odor, and overall acceptability for uncooked control and MMF lentils sample were 7.49 & 7.22, 7.31 & 7.43, and 7.39 & 7.32, respectively. Although the difference in appearance was significant, it was numerically very low. This could be due to adding only 15% of the extruded fortified lentil, which looks similar to the control lentil. Overall, 40%, 34%, and 26 % of the consumers scored lower, higher, and similar for MMF lentils compared to the unfortified uncooked sample. These results suggest that multiple micronutrient fortification did not negatively impact the sensory characteristics of fortified lentils. Similar to the uncooked samples, consumer responses to both the unfortified and fortified cooked samples were significantly similar across all five attributes, including overall acceptability. The control and MMF samples exhibited a similar range and dispersion for all attributes except taste. The average sensory scores of appearances, odor, taste, texture, and overall acceptability for cooked control and MMF samples were 7.54 & 7.44, 7.68 & 7.28, 7.36 & 7.14, 7.48 & 7.31, and 7.61 & 7.50, respectively. For both samples, the control lentils received a higher score for all five attributes than MMF lentils. Overall, 55%, 24%, and 22 % of the consumers scored lower, higher, and similar for MMF lentils compared to the unfortified cooked sample.

Boxplot comparisons of both uncooked and cooked samples revealed that some outlier scores might have significantly influenced the average scores of the lentil samples. Some consumers rated both the uncooked and cooked control and fortified lentils with lower hedonic scores (dislike slightly, a score of four; neither dislike nor like, a score of five). Overall, the liking scores indicated that both cooked and uncooked samples were equally accepted by the participants.

Consumer evaluations indicated no significant difference in preference for sensory qualities or overall satisfaction between uncooked and cooked lentil samples. This uniformity in scoring could be attributed to cooking methods based on traditional recipes for making lentil soup (Kohinoor et al., 2010). Ingredients like dry turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) powder and onion (Allium cepa L.), which are commonly used in cooking lentils, can enhance visual appeal by reducing darkness with turmeric’s yellow hue. They also modify the scent and flavor profiles, potentially masking any metallic taste from fortified lentils [

23]. Similar negligible variances were observed when comparing sensory characteristics of cooked conventional versus fortified rice [

42] Furthermore, this research utilized fortified lentils processed at the Saskatchewan Food Industry Development Centre in Canada, where canola oil is typically employed post-dehulling for an enhanced glossy appearance aimed at increasing consumer appeal; however, other oils like palm or soybean were deliberately excluded from this process to prevent any potential impact on flavor or aroma. Participants were briefed on the recipe prior to commencing with sensory assessments.

Sensory analysis allows for the evaluation of products quickly and cost-effectively with representative consumers who regularly consume the product and possess sensory skills [

43]. The impact of fortification on the sensory properties of food varies greatly and depends on the components of the fortificants (minerals and vitamins), their doses, and the food items [

19]. In this study, although consumers could easily distinguish the MMF samples from the control, the overall acceptability was statistically similar for both uncooked and cooked samples.

The consistency of sensory data was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (CA), which indicated that panelists consistently scored both uncooked and cooked samples, with CA values falling within the acceptable range (0.75 to 0.95) [

31,

32]. However, the uncooked fortified sample had a CA value of 0.68, which is below the suggested range. This inconsistency could be attributed to the variable scoring by consumers for this sample. One study noted that missing values can affect the psychometric properties of any test [

44]. Since the data were cross-sectional, generalizability cannot be inferred from this study, so caution is advised when interpreting these specific results.

Lentils are often paired with rice as a staple food in many countries, such as Bangladesh. They are also a promising option for quick-cooking meals that can be further enhanced nutritionally. MMF lentils offer a sustainable, whole-food solution to address micronutrient deficiencies in countries where lentils are commonly consumed. We estimated that a 50 g serving of fortified lentils used in a cooked lentil can provide approximately 992 IU of vitamin A palmitate, 0.06 mg of beta carotene, 93.8 IU of vitamin D3, 0.77 µg of vitamin B12, 1.22 mg of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine hydrochloride), 4.6 mg of niacinamide, 1.98 mg of thiamine mononitrate, 0.15 mg of folic acid, 11.2 mg of iron (ferric pyrophosphate hydrate), and 4.87 mg of zinc (zinc sulfate monohydrate). These amounts cover a significant portion of the Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) for these micronutrients, as the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended.

Figure 1.

Images of uncooked lentil samples from two red lentil products: (a) unfortified control lentils, and (b) fortified lentils containing 15 g of extruded fortified lentil kernels mixed with 100 g of unfortified control lentils.

Figure 1.

Images of uncooked lentil samples from two red lentil products: (a) unfortified control lentils, and (b) fortified lentils containing 15 g of extruded fortified lentil kernels mixed with 100 g of unfortified control lentils.

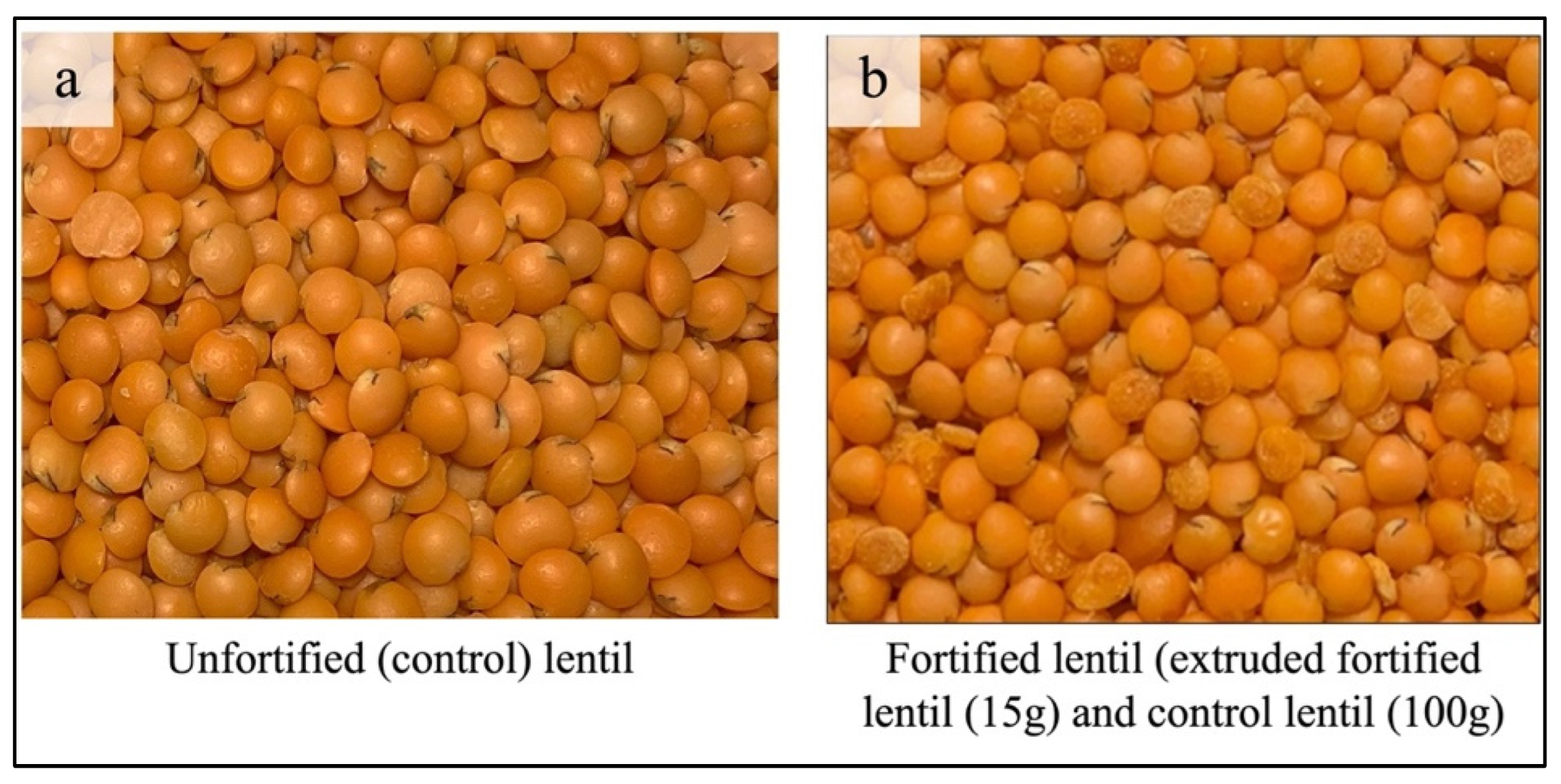

Figure 2.

Images of cooked lentil samples from two red lentil products: (a) unfortified control lentils, and (b) fortified lentils containing 15 g of extruded fortified lentil kernels mixed with 100 g of unfortified control lentils.

Figure 2.

Images of cooked lentil samples from two red lentil products: (a) unfortified control lentils, and (b) fortified lentils containing 15 g of extruded fortified lentil kernels mixed with 100 g of unfortified control lentils.

Figure 3.

Box plot analysis of hedonic scores (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely) obtained for two uncooked lentil samples (unfortified control lentil polished with 0.5% canola oil; multiple micronutrient fortified lentil) evaluated for appearance, odor, and overall acceptability by 150 panelists in Bangladesh. Different letters above the box plots signify significant differences between the two samples for each attribute. Each box plot shows the data distribution for each sample type separately, using a five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median, third quartile (Q3), and maximum.”

Figure 3.

Box plot analysis of hedonic scores (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely) obtained for two uncooked lentil samples (unfortified control lentil polished with 0.5% canola oil; multiple micronutrient fortified lentil) evaluated for appearance, odor, and overall acceptability by 150 panelists in Bangladesh. Different letters above the box plots signify significant differences between the two samples for each attribute. Each box plot shows the data distribution for each sample type separately, using a five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median, third quartile (Q3), and maximum.”

Figure 4.

Box plot analysis of hedonic scores (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely) obtained for two cooked lentil samples: an unfortified control lentil polished with 0.5% canola oil, and a multiple micronutrient fortified lentil. These samples were evaluated for appearance, odor, and overall acceptability by 150 panelists in Bangladesh. Different letters above the box plots indicate significant differences between the two samples for each attribute. Each box plot shows the data distribution for each sample type separately, based on a five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median, third quartile (Q3), and maximum.

Figure 4.

Box plot analysis of hedonic scores (1 = dislike extremely, 9 = like extremely) obtained for two cooked lentil samples: an unfortified control lentil polished with 0.5% canola oil, and a multiple micronutrient fortified lentil. These samples were evaluated for appearance, odor, and overall acceptability by 150 panelists in Bangladesh. Different letters above the box plots indicate significant differences between the two samples for each attribute. Each box plot shows the data distribution for each sample type separately, based on a five-number summary: minimum, first quartile (Q1), median, third quartile (Q3), and maximum.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants involved in the sensory evaluation study of multiple micronutrient fortified lentils conducted in Bangladesh.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants involved in the sensory evaluation study of multiple micronutrient fortified lentils conducted in Bangladesh.

| Characteristics of the profile |

Number (%) |

Biological sex

|

Male |

76 (50.7) |

| Female |

74 (49.3) |

Age (years)

|

16–25 |

32 (21.3) |

| 26–35 |

50 (33.3) |

| 36–45 |

40 (26.7) |

| 46–55 |

19 (12.7) |

| 56–65 |

9 (6.0) |

| Count of employed individuals within the household |

1–5 |

114 (76.0) |

| 6–10 |

34 (22.7) |

| ≥11 |

2 (1.3) |

| Aggregate monthly earnings from various sources (Bangladeshi Taka) |

5000–9999 (~ 90 to 120 USD) |

11 (7.4) |

| 10000–19999 (~ 121 to 240 USD) |

82 (55.0) |

| 20000–29999 (~ 241 to 360 USD) |

28 (18.0) |

| 30000–39999 (~ 361 to 480 USD) |

19 (12.8) |

| ≥40000 (≥480 USD) |

9 (6.0) |

Education

|

Illiterate |

2 (1.3) |

| Incomplete elementary (primary; grade 5) |

7 (4.7) |

| Completed elementary |

65 (43.6) |

| Passed Secondary School Certificate (grade 10) |

34 (22.8) |

| Passed Higher Secondary Certificate (grade 12) |

41 (27.5) |

Table 2.

Lentil consumption behaviors and trends among consumers.

Table 2.

Lentil consumption behaviors and trends among consumers.

| Observation |

Consumer pulse purchases

(g/family/week) |

Number of consumers (%) |

Purchasing lentils by the consumers

|

100–250 |

24 (16.0) |

| 251–500 |

86 (57.3) |

| 501–750 |

13 (8.7) |

| 751–1000 |

18 (12.0) |

| ≥1001 |

9 (6.0) |

Other pulse (chickpeas, mung beans, black gram, field peas, etc.) purchases by the consumers

|

100–250 |

77 (51.3) |

| 251–500 |

56 (37.3) |

| 501–750 |

5 (3.3) |

| 751–1000 |

3 (2.0) |

| ≥1001 |

9 (6.0) |

Lentil purchase source

|

Retail shops |

141 (94.0) |

| Wholesale |

8 (5.3) |

| Do not buy or produce |

1 (0.7) |

Frequency of lentil purchase

|

Several days in a week |

7 (7.4) |

| Weekly |

11 (7.3) |

| Fortnightly |

4 (2.7) |

| Monthly |

128 (85.3) |

Lentil product preference market

|

Dehulled football |

143 (95.3) |

| Dehulled split |

7 (4.7) |

Table 3.

Lightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*) scores of unfortified and fortified lentil samples prepared using multiple micronutrients.

Table 3.

Lightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*) scores of unfortified and fortified lentil samples prepared using multiple micronutrients.

| |

Samples |

CIELAB color score [Mean (CI 95%)] a

|

| Lightness (L*) |

| |

Unfortified |

55.62 ± 0.50 a

|

| |

Fortified |

58.07 ± 0.23 b

|

| Redness (a*) |

| |

Unfortified |

34.62 ± 0.16 a

|

| |

Fortified |

33.65 ± 0.35 a

|

| Yellowness (b*) |

| |

Unfortified |

40.56 ± 0.34 a

|

| |

Fortified |

40.39 ± 0.39 a

|

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between the colorimetric data (lightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*)) obtained from HunterLab and sensory acceptability scores from Bangladeshi consumers were analyzed for two attributes (appearance and overall acceptability) of three uncooked lentil types (red football, red split, and yellow split). All correlation coefficients were found to be significant at p < 0.0001.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between the colorimetric data (lightness (L*), redness (a*), and yellowness (b*)) obtained from HunterLab and sensory acceptability scores from Bangladeshi consumers were analyzed for two attributes (appearance and overall acceptability) of three uncooked lentil types (red football, red split, and yellow split). All correlation coefficients were found to be significant at p < 0.0001.

| Sensory Attributes |

L, a*, and b* scores obtained from HunterLab |

| L |

a* |

b* |

| Appearance (n = 3) |

-0.98 |

0.96 |

0.95 |

| Overall acceptability (n = 3) |

-0.98 |

0.97 |

0.96 |

Table 5.

Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of sensory panelists’ ratings for uncooked and cooked control and fortified lentils.

Table 5.

Internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of sensory panelists’ ratings for uncooked and cooked control and fortified lentils.

| Samples |

CA Score |

| Uncooked |

Control/unfortified |

0.75 |

| |

Fortified |

0.68 |

| Mean value for all uncooked samples |

0.71 |

| Cooked |

Control/unfortified |

0.79 |

| |

Fortified |

0.79 |

| Mean value for all cooked samples |

0.79 |