1. Introduction

The global demand for seafood products is increasing and plays a significant role in household menus worldwide [

1,

2]. Currently, seafood supply consists of 62% from wild capture and 38% from aquaculture [

3]. The ability to expand seafood production depends on various factors, including natural conditions, available water surface area, and fishing and aquaculture practices [

4,

5]. More than 80% of global seafood products originate from Asian countries, including Vietnam, which has favorable conditions for aquaculture development [

6,

7]. In 2022, Vietnam's total aquatic product output reached 9.02 million tons, consisting of 5.2 million tons from aquaculture and 3.8 million tons from wild capture [

8]. The aquaculture industry has experienced significant growth over the past five years, with

Pangasius catfish and brackish shrimp (White leg shrimp and Giant tiger prawn species) being the primary farmed species in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam [

9,

10,

11]. However, since 2015, Vietnam has been increasingly affected by climate change, including saline intrusion, rising temperatures, irregular rainfall, and the construction of high dikes for rice cultivation protection. These environmental changes have contributed to widespread shrimp diseases [

12,

13]. In addition to environmental pressures, the shrimp farming sector faces challenges such as disease outbreaks and economic difficulties, underscoring its vulnerability. Consequently, The report on the needs of aquaculture farmers in the Mekong River Delta, Vietnam in 2024, conducted by Ingrid [

14], found that Vietnamese shrimp farmers have experienced a 20% to 60% decline in net earnings since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The mud crab (

Scylla paramamosain) is an economically significant species inhabiting the mangroves and estuaries of tropical regions. It is a highly valued seafood product in Vietnam’s coastal areas and Southeast Asian markets. This species thrives in challenging conditions, demonstrating rapid growth, high tolerance to environmental fluctuations, strong disease resistance, a diverse diet, and substantial size [

15,

16]. Additionally, mud crabs possess reliable reproductive potential, significant economic value, and excellent post-harvest preservation qualities. Consequently, they are considered an ideal species for aquaculture alongside shrimp [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Moreover, mud crab farming operates as a large-scale agricultural system that minimizes the use of pesticides and commercial feed. Extensive farming practices allow crab fry to develop naturally with minimal human intervention [

18,

21,

22]. This approach is expected to support the sustainable development of the aquaculture industry by reducing environmental harm and minimizing health risks associated with excessive antibiotic and growth stimulant use [

21].

According to the statistics of Directorate of Fisheries [

23], total farmed mud crab production in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam, reached 66,000 tons in 2022, representing an approximate 19% increase compared to 2017. This production is expected to continue growing through 2025. The previous studies are reported that the transition from specialized shrimp farming to extensive mud crab farming initially generated substantial revenue. On average, farmers in the Mekong Delta earned aprroximate 30–50 million VND per hectare per crop [

15,

18,

22,

24,

25]. However, mud crab farming in the region currently faces several challenges. There is no designated farming area plan established by local governments, breed quarantine measures are not implemented, and collaboration among stakeholders remains limited [

15,

26,

27]. Additionally, the industry lacks a recognized brand for mud crab products, and farming practices remain unstandardized, with no established quality control measures for inputs. Most importantly, the absence of comprehensive government macro policies to regulate annual development in response to market fluctuations has made mud crab prices unpredictable, directly affecting farmers' incomes [

15,

19,

22,

24,

26]. Furthermore, mud crabs are primarily consumed domestically and are not widely exported [

24,

26].

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers have become increasingly concerned about their health and quality of life, with a particular focus on improving their diets by selecting nutritious foods, including seafood and other aquatic animal sources [

28,

29,

30]. However, the quality and origin of seafood and aquatic products vary significantly, leading to inconsistencies in consumer trust [

31,

32,

33].

Mud crabs, shrimp, and other crustaceans play a crucial role in human nutrition, and consumer purchasing decisions are influenced by factors such as brand recognition, perceived health benefits, and food safety concerns[

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. However, mud crab products are highly perishable and undergo significant quality deterioration during transportation and storage, posing additional challenges to their marketability [

39,

41,

42]. Carlucci, Nocella [

43] conducted a study reviewing seafood purchasing behavior and identified key factors influencing consumer decisions, including fish availability, price perception, and self-efficacy in preparation, convenience, eating habits, health beliefs, and sensory perception. Additional attributes affecting purchasing choices include production methods, country of origin, preservation techniques, product innovation, packaging, and eco-labeling. In recent years, consumer concerns about seafood quality have increased, particularly regarding live and frozen products. A study conducted by a data journalist in the United States examined consumer preferences for different crab sexes and found that American consumers prefer male crabs over female crabs due to their larger size and higher demand. Consequently, female crabs are sold at lower prices. Additionally, consumers tend to avoid female crabs due to the presence of roe, further influencing market trends [

43,

44]. In contrast, consumers in Vietnam primarily purchase fresh whole mud crabs for home preparation [

4,

16,

24].

The objective of this study is to investigate and develop a comprehensive understanding of buyer behavior, purchasing preferences, and the key factors influencing consumer decisions regarding mud crabs (Scylla paramamosain) in Vietnam’s largest cities. The findings will provide valuable insights for mud crab producers, local governments, and policymakers, enabling them to better understand consumer preferences and optimize production to align with market demands for product type, quality, safety, and affordability more effectively.

2. Theoretical Approach and Perspective Review

Consumer behavior refers to the actions individuals take in acquiring and using goods or services, including searching, selecting, purchasing, and consuming products to meet personal needs. It not only involves the specific behaviors related to buying and using products but also the psychological and social processes that occur before, during, and after these actions [

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

The analysis of consumer behavior regarding perishable mud crab products aims to enhance profitability and reduce risks associated with unmet consumer demands while also considering decision-making processes influenced by product attributes [

42]. Research on the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) explores the factors that influence consumer decision-making and purchase intentions [

50]. Consumer behavior is a widely studied concept in economics, particularly in marketing. According to Blackwell, Miniard [

48],

“Consumer behavior encompasses all activities directly associated with the processes of searching, collecting, purchasing, owning, utilizing, and disposing of products and services”. It includes the decision-making processes that occur before, during, and after these actions. Consumer behavior examines the actions of individuals, groups, or organizations and the processes through which they select, acquire, use, and dispose of products, services, experiences, or ideas to satisfy personal and societal needs [

45,

51,

52,

53].

Many researchers use market analysis methods to study seafood consumers, aiming to identify the key factors influencing their purchasing decisions. This topic has been widely explored on a global scale [

30,

45,

50,

51,

54]. Similar to Vietnam, scholars have concentrated on consumer behavior about safe seafood goods [

35,

55,

56,

57,

58]. Studies on customers' preferences for fresh mud crabs have been undertaken in many crab-producing nations [

39,

40,

41,

59] (Binpeng

et al., 2016; Riniwati

et al., 2017; Khasanah

et al., 2019; Lorenzo

et al., 2021). In Vietnam, most research on mud crabs has focused on the economic aspects of mud crab production [

17,

18,

21,

22,

24] (Hien et al., 2015; Nghi et al., 2015b; Pho, 2015). However, no studies have yet explored the purchasing decisions of urban consumers regarding fresh mud crabs.

This research integrates the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to achieve research objectives. In the TRA model, an individual's beliefs about a product shape their attitude toward purchasing fresh mud crab, which in turn influences their purchase intention, but not their actual purchase behavior directly. Therefore, attitudes help explain the factors affecting consumer purchase intentions, while these intentions serve as the strongest predictors of actual purchasing behavior [

45]. In the TPB model, behavioral intentions are influenced by three key factors. First, attitudes refer to an individual's favorable or unfavorable evaluation of a behavior. Second, social influence represents the perceived societal pressure to perform or avoid a specific action. Lastly, the Theory of Planned Behavior expands on the TRA model by incorporating perceived behavioral control, which reflects the ease or difficulty of performing a behavior based on the availability of resources and opportunities [

51,

60].

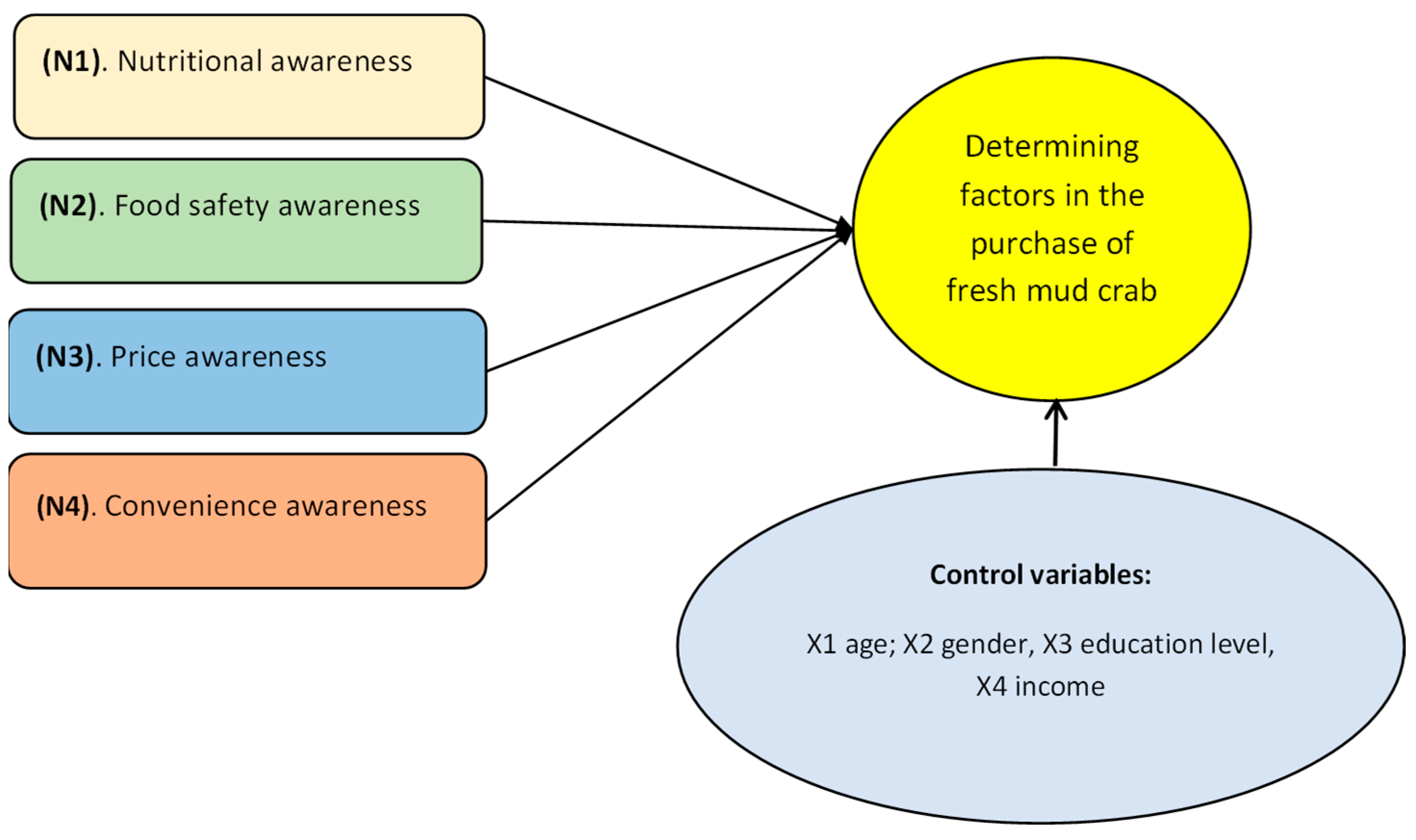

The proposed research model identifies key factors influencing the purchase of fresh mud crab as follows: Consumer attitude factors (N1) include the

'Perception of Nutritional Needs,' which encompasses health maintenance, adequate nutrition, absence of contamination, and the establishment of clear quality assessment standards [

41,

61,

62]. Another key factor (N2),

'Perception of Food Hygiene and Safety,' includes concerns about clear product origin, absence of preservatives, absence of parasites, and absence of allergens [

37,

63,

64]. The factor group (N3),

'Price Awareness' includes market price comparisons, assessments of fair pricing relative to income, and evaluations of fresh product pricing [

34,

47,

61]. Additionally, personal consumer variables such as age, gender, income, and distance influence the decision to purchase crabs [

34,

47,

61]. The factor group (N4) related to the ease or difficulty of acquiring a product includes the '

Perception of Ease of Access,' which encompasses convenient storage, a variety of options, easy purchasing when needed, and efficient processing [

34,

35,

63]. The proposed research models are presented in

Figure 1

5. Solutions and Recommendations

5.1. Basis for Proposing Solutions

This study has developed a new purchase decision scale consisting of four cognitive variables and four control variables. Analysis of the multivariate regression model reveals that two independent variables, namely nutrition awareness and convenience perception, significantly influence the decision to purchase fresh crab. These findings provide a foundation for proposing practical solutions based on the research.

5.2. Solutions and Recommendations to Enhance the Value of Vietnam's Mud Crab

Improving the nutritional quality of seawater during aquaculture and raising consumer awareness of the nutritional benefits of crab products are essential. Firstly, Crab farmers must strengthen quality control by closely monitoring cultivation, harvesting, transportation, and preservation processes to ensure high nutritional value. This includes assessing the aquaculture environment, testing water quality, optimizing the crabs' diet, and maintaining their integrity during transport to market. It is also crucial to promote and enforce food hygiene and safety standards in crab product preparation. Researchers should develop scientific frameworks to better understand the nutritional value of crabs and refine aquaculture techniques to enhance their quality. Additionally, production methods should be improved to preserve essential nutrients in crab products. Organizations must collaborate to independently verify that crab products meet food quality and safety standards. The use of certification markers can further enhance consumer trust in the nutritional quality of crab products.

Develop promotional and training strategies to increase consumer awareness of the nutritional benefits of crab products. Include detailed nutritional information on product packaging to inform consumers about their health advantages. The Vietnamese government should implement regulations to strengthen the crab industry and protect renewable marine resources. Public education initiatives should be enhanced to highlight the nutritional value and importance of crab-based meals. To expand international markets and trade, export strategies should be developed to enhance global market penetration and increase the value of crab products worldwide. Additionally, fostering international collaboration on the coastal zone and maritime resource management as well as trade policies will further support the industry's mud crab growth.

Secondly, enhancing the distribution system and diversifying crab products is crucial to increasing accessibility and expanding consumer reach. This can be achieved through the following strategies:

Develop a variety of products: Create a diverse range of crab offerings, including packaged options such as steamed and pre-cooked crab. Introduce health-conscious alternatives, such as low-sodium or low-fat varieties, for nutrition-focused consumers.

Expand distribution partnerships: Collaborate with restaurants, hotels, supermarkets, and food distributors to ensure a wide selection of crab products. Establish long-term agreements with partners to maintain a stable and consistent supply.

Broaden distribution channels: Improve direct-to-consumer access by leveraging online platforms, mobile applications, and home delivery services. Partner with local food retailers to make crab products more readily available.

Invest in technology: Enhance manufacturing, preservation, and shipping processes using advanced cleaning, packaging, and storage technologies to improve convenience and extend shelf life.

Boost marketing efforts: Develop targeted advertising campaigns to raise awareness and attract consumers to crab products. Utilize social media and digital marketing strategies to generate interest and drive sales.

Create consumer-friendly options: Offer ready-to-eat crab products, pre-processed selections, and items with simple cooking instructions. Ensure practical packaging with clear nutritional information for added consumer convenience.

Introduce value-added promotions: Develop combo packages and special incentives to encourage the purchase of multiple crab products. Implement rewards, promotions, and loyalty programs to enhance consumer engagement and satisfaction.

By implementing these solutions, the mud crab industry can diversify its product offerings, improve consumer convenience, and expand its market reach. This, in turn, will drive industry growth and create new trade, and business opportunities.

6. Conclusion

This study developed a 16-item scale to assess factors influencing consumer purchasing decisions for crabs in three biggest cities of Vietnam. The multiple regression analysis identified two key determinants. First, consumers strongly associate fresh crabs with superior quality, expecting them to provide optimal freshness, high mineral content, excellent flesh texture, and enhanced flavor compared to canned alternatives. To expand the market for fresh crab products, it is crucial to preserve their nutritional value and establish a well-defined nutritional profile for each crab variety at different market stages. Second, convenience plays a significant role in purchasing decisions. Consumers prefer mud crab products that offer a diverse selection, widespread availability, ease of preparation, and simplicity of use after processing.

Based on the regression analysis, two key strategies are recommended for developing new crab products: (1) Enhancing nutritional quality to meet consumer expectations for health benefits, and (2) Strengthening distribution networks and diversifying product offerings to improve accessibility and convenience. To expand the fresh crab market in Vietnam, businesses should focus on maintaining and effectively communicating the high nutritional value of crab products while optimizing distribution and product variety. Implementing these strategies will increase consumer interest and drive market growth both domestically and internationally.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model of the key factors influencing the purchase of fresh mud crab.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model of the key factors influencing the purchase of fresh mud crab.

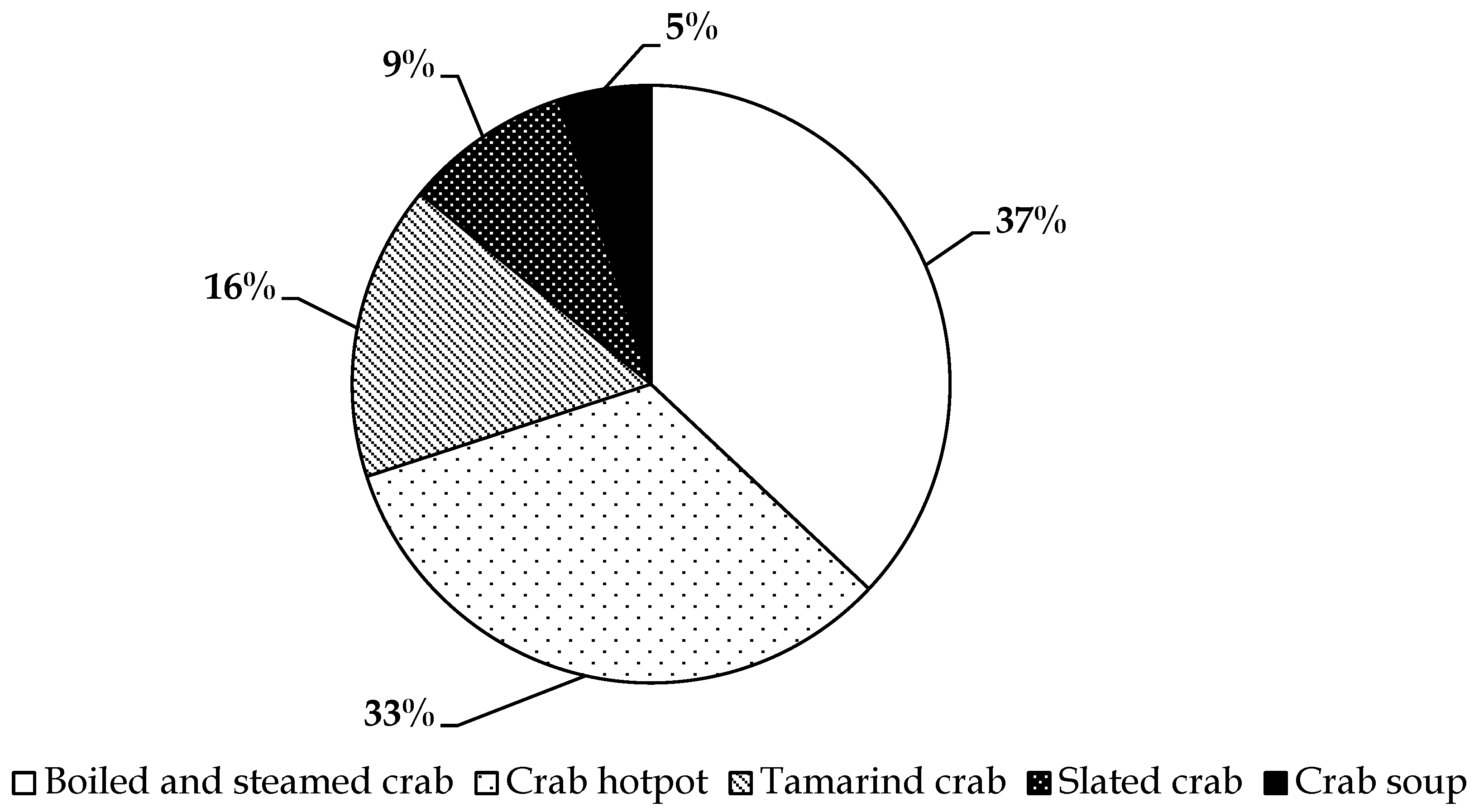

Figure 2.

Consumer preferences in three largest cities (Can Tho, Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi) of Vietnam for different fresh mud crab dishes.

Figure 2.

Consumer preferences in three largest cities (Can Tho, Ho Chi Minh and Hanoi) of Vietnam for different fresh mud crab dishes.

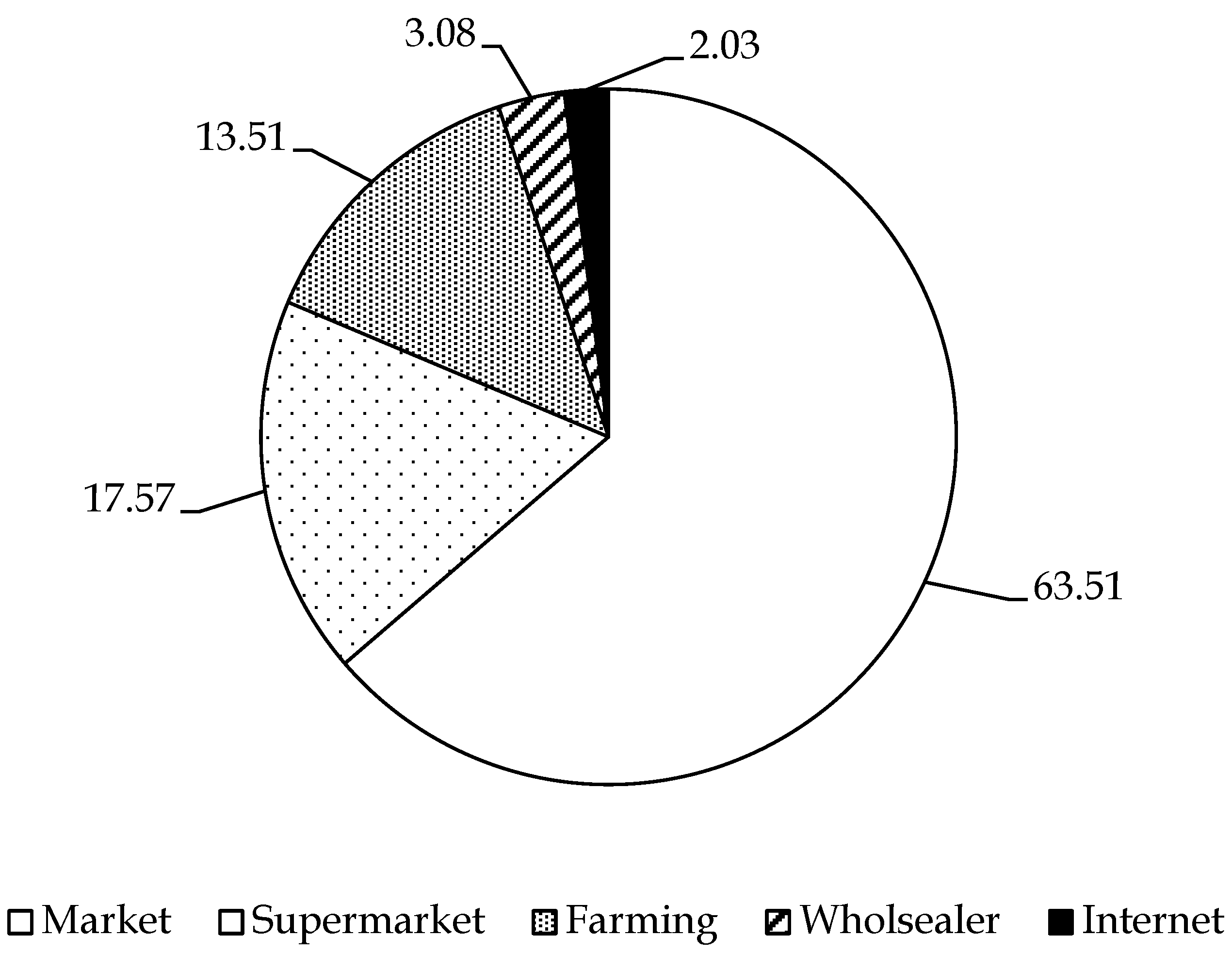

Figure 3.

percentage distribution of consumer preferences for different crab dishes.

Figure 3.

percentage distribution of consumer preferences for different crab dishes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of fresh mud crab consumers in three major cities (Can Tho, Ho Chi Minh, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 1.

Characteristics of fresh mud crab consumers in three major cities (Can Tho, Ho Chi Minh, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

| Respondent characteristics |

Medium |

Standard deviation |

Min |

Max |

| Age (years)

|

32 |

8.4 |

20 |

62 |

| Number of family members (people)

|

3.7 |

1.4 |

1 |

9 |

| Female ratio (%) |

69 |

|

|

|

| Male ratio (%) |

31 |

|

|

|

| Education level |

|

|

|

|

| PhD |

0.75

|

|

|

|

| Master |

7.46

|

|

|

|

| Bachelor |

70 |

|

|

|

|

College

|

8.95

|

|

|

|

|

Intermediate

|

5.9

|

|

|

|

| High School |

6.94

|

|

|

|

| Career (%)

|

|

|

|

|

| Unemployed |

3.7 |

|

|

|

| Housewife |

12 |

|

|

|

| General labour |

9 |

|

|

|

| Office staff |

60.4 |

|

|

|

| Teacher |

2,9 |

|

|

|

| Online sales |

12 |

|

|

|

| Income (million VND/person/month) |

11 |

15 |

1 |

104 |

| Household food expenses (million VND/month) |

11.2 |

9 |

2 |

70 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of fresh mud crab consumption in three major cities (Can Tho, Ho Chi Minh, Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 2.

Characteristics of fresh mud crab consumption in three major cities (Can Tho, Ho Chi Minh, Hanoi), Vietnam.

| Respondent characteristics |

Medium |

Standard deviation |

Min |

Max |

| Number of crab purchases (times/household/year) |

|

Times

|

2.1 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

12 |

| Purchase rate of each type of crab (%) |

|

Crab with roe

|

53.7 |

|

|

|

|

Crab meat

|

56.0 |

|

|

|

|

Crab bucket

|

6.0 |

|

|

|

| Purchase volume of each type of crab (kg/household/year) |

|

Crab with roe

|

3.5 |

2.8 |

1.0 |

20 |

| Crab meat (Y crab) |

5.1 |

2.9 |

0.5 |

13 |

|

Crab bucket

|

6.0 |

2.9 |

2.0 |

10 |

| Amount spent on each type of crab (1000 VND/household/year) |

|

Crab with roe

|

1,454 |

1,040 |

280 |

6,420 |

| Crab meat (Y crab) |

1,656 |

1,042 |

175 |

5,030 |

|

Crab bucket

|

976.0 |

386.0 |

420 |

1,560 |

Table 3.

Cronbach's Alpha test.

Table 3.

Cronbach's Alpha test.

| Numerical order |

Observation variable name |

Total variable correlation coefficient |

Cronbach's Alpha coefficient |

Eliminated variable |

| NU1 |

Fresh crab ensures freshness |

0.87 |

0.92 |

|

| NU2 |

Fresh crab ensures high minerals |

0.86 |

0.93 |

|

| NU3 |

Fresh crab has sweet meat |

0.87 |

0.92 |

|

| NU4 |

Fresh crab tastes better than canned products |

0.87 |

0.92 |

|

| FHS1 |

Fresh crab does not contain toxic substances |

0.74 |

0.83 |

|

| FHS2 |

Fresh crab ensures clear origin |

0.76 |

0.82 |

|

| FHS3 |

Fresh crab does not contain preservatives |

0.67 |

0.84 |

|

| FHS4 |

Fresh crab does not contain parasites |

0.63 |

0.85 |

|

| FHS5 |

Fresh crab does not cause allergies |

0.66 |

0.85 |

|

| PR1 |

The price of fresh crab is an important issue for me |

0.88 |

0.89 |

|

| PR2 |

The price of fresh crab is commensurate with the quality |

0.87 |

0.82 |

|

| PR3 |

The price of fresh crab is higher than that of shrimp |

0.74 |

0.84 |

X |

| PR4 |

The price of fresh crab is suitable for my family's income |

0.87 |

0.89 |

|

| CO1 |

Fresh crab has a variety of types to choose from |

0.81 |

0.94 |

|

| CO2 |

Fresh crab is easy to find everywhere |

0.82 |

0.93 |

|

| CO3 |

Fresh crab is convenient for processing |

0.83 |

0.96 |

|

| CO4 |

Fresh crab is easy to use after processing |

0.83 |

0.90 |

|

| PD1 |

I decided to buy crab because of its high nutrition |

0.91 |

0.91 |

|

| PD2 |

I decided to buy crab because of food safety |

0.77 |

0.96 |

X |

| PD3 |

I decided to buy crab sea because the price is suitable for family |

0.90 |

0.90 |

|

| PD4 |

I decided to buy sea crab because of the high convenience |

0.91 |

0.90 |

|

Table 4.

Matrix of factors influencing people's decision to consume fresh crab in largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 4.

Matrix of factors influencing people's decision to consume fresh crab in largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

| Observation variable |

Factors |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| 1. Fresh mud crab ensures freshness |

0.90 |

|

|

|

| 2. Fresh mud crab ensures high minerals |

0.89 |

|

|

|

| 3. Fresh mud crab has sweet meat |

0.91 |

|

|

|

| 4. Fresh mud crab tastes better than canned products |

0.89 |

|

|

|

| 5. Fresh mud crab does not contain toxic substances |

|

0.84 |

|

|

| 6. Fresh mud crab ensures clear origin |

|

0.85 |

|

|

| 7. Fresh mud crab does not contain preservatives |

|

0.79 |

|

|

| 8. Fresh mud crab does not contain parasites |

|

0.77 |

|

|

| 9. Fresh mud crab does not cause allergies |

|

0.78 |

|

|

| 10. Fresh mud crab has a variety of types to choose from |

|

|

0.87 |

|

| 11. Fresh mud crab is easy to find everywhere |

|

|

0.86 |

|

| 12. Fresh mud crab is convenient for processing |

|

|

0.89 |

|

| 13. Fresh mud crab is easy to use after processing |

|

|

0.88 |

|

| 14. The price of fresh mud crab is an important issue for me |

|

|

|

0.94 |

| 15. The price of fresh mud crab is commensurate with the quality |

|

|

|

0.96 |

| 16. The price of fresh mud crab is suitable for my family's income |

|

|

|

0.93 |

| KMO coefficients |

0.706 |

Table 5.

Groups of factors influencing people's decision to purchase fresh crab in three largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 5.

Groups of factors influencing people's decision to purchase fresh crab in three largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

| Group of factors |

Factor name |

Medium |

Evaluate ** |

| N1 |

Nutritional awareness |

3.6 |

affect |

| N2 |

Food safety awareness |

3.8 |

affect |

| N3 |

Perception of convenience |

3.6 |

affect |

| N4 |

Price awareness |

3.3 |

neutral |

Table 6.

KMO and Bartlett's test – tourist satisfaction scale in three largest citities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 6.

KMO and Bartlett's test – tourist satisfaction scale in three largest citities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

|

“KMO coefficient”

|

0.77 |

| Bartlett's test |

Chi-square value |

732 |

| df |

3.0 |

| Sig – Observational significance level |

0.000 |

Table 7.

Factor analysis results – tourist satisfaction scale in the three largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 7.

Factor analysis results – tourist satisfaction scale in the three largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

| |

“Load factor |

| Purchase decision 1 |

0.97 |

| Purchase decision 3 |

0.97 |

| Purchase decision 4 |

0.95 |

| Eigenvalue |

2.80 |

|

“Cumulative variance |

0.93 |

Table 8.

Factors influencing consumers' intention to purchase processed crab in three largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

Table 8.

Factors influencing consumers' intention to purchase processed crab in three largest cities (Can Tho City, Ho Chi Minh City, and Hanoi), Vietnam.

| Symbol |

Variable name |

Estimated coefficient β |

Standard error |

P value |

| X1 |

Age (years) |

0.001ns

|

0.003 |

0.659 |

| X2 |

Gender (1-Male; 0-Female) |

-0.02ns

|

0.049 |

0.650 |

| X3 |

Education (years of schooling) |

-0.08ns

|

0.014 |

0.589 |

| X4 |

Income (million VND/month) |

-0.04ns

|

0.031 |

0.235 |

| N1 |

Nutritional awareness |

0.914***

|

0.022 |

0.000 |

| N2 |

Food safety awareness |

0.036ns

|

0.023 |

0.119 |

| N3 |

Perception of convenience |

0.256***

|

0.022 |

0.000 |

| N4 |

Price awareness |

-0.014ns

|

0.022 |

0.547 |

| |

Constant |

0.193 ns

|

0.247 |

0.435 |

| Y |

Decision to buy fresh crab |

|

| Number of observations |

|

200 |

| P value |

|

0.000 |

| Coefficient of determination R2 (%) |

|

90 |