1. Introduction

Oilseed crops are one of the most abundant sources of vegetable oils which are produced and processed in large quantities and utilized in many applications including food, feed, oleochemicals and biodiesel production. They contribute a significant role in human health due to their nutritional components [

1,

2]. The most cultivated oilseed crops are soybean, rapeseed, sunflower, peanut, cotton and oil palm [

3]. Recently, flaxseed (

Linum usitatissimum L.) and hemp seed (

Cannabis sativa L.) are becoming increasingly popular around the world because of their growing demand and economic benefits [

4,

5,

6]. Flaxseed is rich in various functional components such as oil, protein, polysaccharides and lignans. It is an important oilseed crop grown mainly in Canada, Argentina, USA, China and India [

4,

7]. Flaxseed accounts for about 35–45% oil located in the kernel composed of cotyledon and endosperm [

4]. Hemp seed oil is also nutritious and rich in essential fatty acids, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [

6]. Hemp seeds contain about 30–50% oil with some variation between varieties depending on the climatic conditions and regions of cultivation [

6,

8,

9]. Currently, hemp crops are not only utilized in the textile processing industry but also applied in the production of new materials, food processing, medical and health products [

10]. Hemp seeds oil have medicinal value, such as anti-oxidation, regulation of blood lipids, improvement of the digestive system, blood pressure reduction, ageing delay and brain nourishment [

11,

12]. The global market for industrial hemp will grow from USD 4.6 billion in 2019 to 9.4 billion USD in 2025 with an annual growth rate of 12.8% [

13]. Most hemp is currently grown for its oil and biomass [

8].

Mechanical pressing is commonly used for oil extraction from oilseeds. Its efficiency has improved over the years because of technological advancements in screw-press design. However, its percentage oil yield is still significantly lower compared to hexane/solvent extraction which adversely affects the economic feasibility of the extraction process [

1]. Industrial processing of plant oils employs high-temperature (hot pressing) and cold pressing methods. A lower oil extraction rate is observed under cold pressing compared to hot pressing [

6,

14]. It has been reported that pretreatment/drying of oilseeds using various methods has a significant influence on the output of oil and the quality attributes [

4,

15,

16,

17]. The drying process involves the principle of simultaneous heat and mass transfer and is quite an energy-intensive method [

18]. The effect of different drying methods including oven or hot air, vacuum, microwave and freeze on the extraction rate, oxidation degree, fatty acid composition, content of minor components such as total phenols, total sterols, vitamin E, chlorophyll and carotenoid of various agricultural products have been studied [

4,

6,

19]. Oven/convective drying is the most used technique for agricultural products due to its feasibility and simplicity in operation, equipment design, and environmental requirements [

17,

19,

20,

21]. Vacuum and microwave are novel drying technologies which are gaining wider application in food processing [

19,

22]. The freeze-drying method can preserve food’s colour, flavour and nutritional content [

17]. New drying technologies including hybrid drying systems are being developed to help reduce post-harvest losses, delay deterioration, lengthen shelf life and ensure rapidity, affordability, simplicity and minimize energy consumption [

17,

23].

To obtain high oil yield and quality, mechanical extraction methods and new extraction techniques such as ultrasound-assisted extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, enzyme-assisted extraction, liquefied gases and supercritical extraction coupled with pretreatment methods have been employed in industrial-scale oil production [

13]. The production of oil from oilseeds can also be visualized under the linear compression process involving a testing machine and a vessel diameter with a plunger [

24,

25]. The linear process provides an alternative approach for improving the mechanical extraction due to its relatively low oil yield which requires further processing of the oilseed cakes with a solvent to recover the residual oil content. Information on the linear process has not been adequately reported on bulk flax and hemp oilseeds under different heating methods. Therefore, the objective of the study was to examine different heating temperatures using the oven and vacuum drying methods for flax and hemp oilseeds by determining the percentage oil yield and energy demand under the linear compression process. The mechanical properties (maximum force, maximum deformation and hardness) of bulk flax and hemp seeds were also determined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

Samples of flax and hemp oilseeds of 5 kg each were used. Prior to the experimentation, the samples were kept under laboratory conditions of a temperature of 20 ± 1.54 °C and humidity of 45 ± 2%.

2.2. Determination of Samples Moisture Content

The moisture content of the sample was determined using the conventional oven method of 105

oC and a drying time of 17 hours [

26]. The electronic balance (KERN & SOHN 440–35, Balingen, Germany) with an accuracy of 0.01 g was used for the samples’ initial and final measurements. The moisture content of the samples was calculated according to [

27] as follows:

where

is the moisture content in wet basis (%),

is the mass of the sample before drying and

is the mass of the sample after oven drying.

2.3. Samples Under oven

and Vacuum

Pretreatments

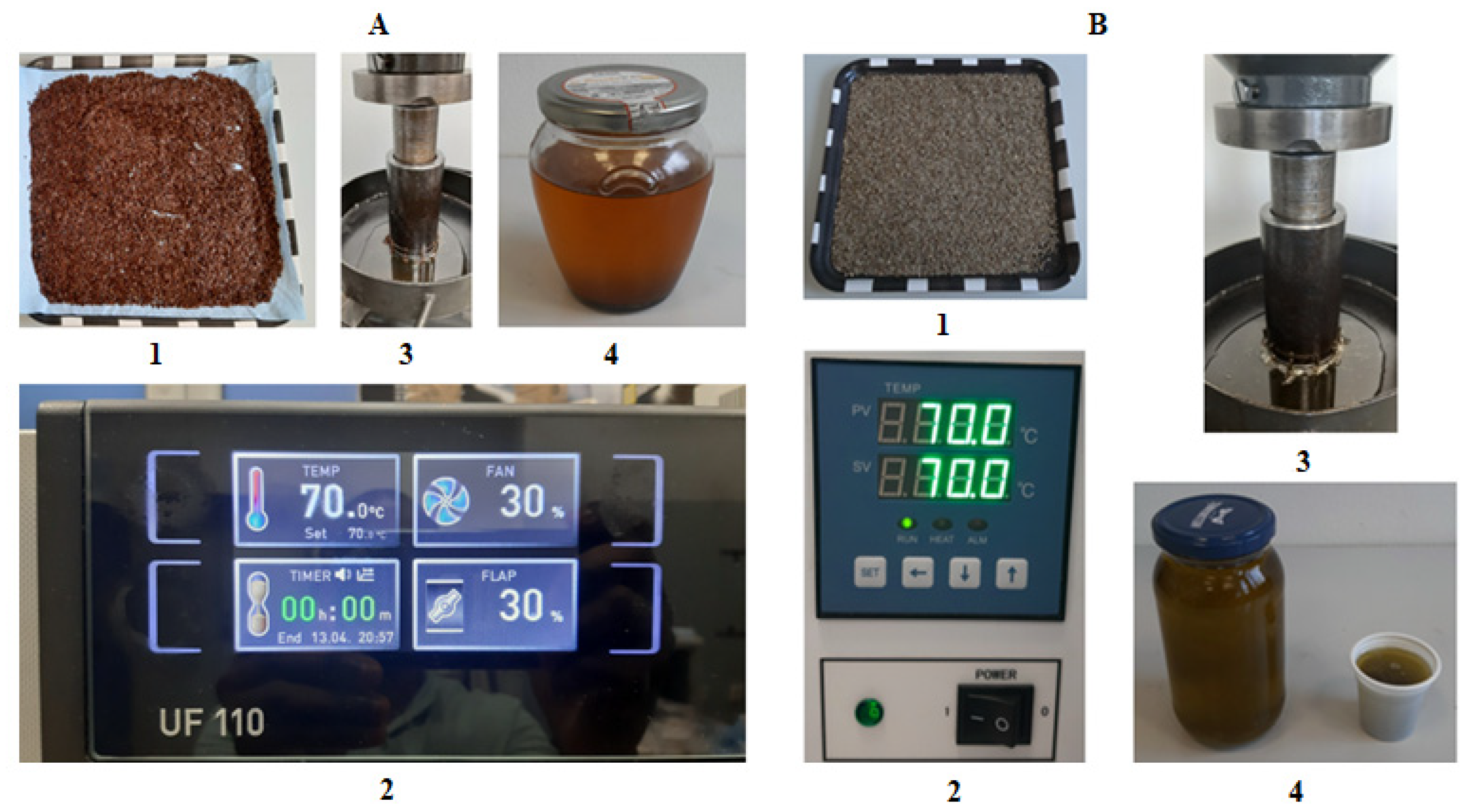

The laboratory temperature of 20 °C served as the control of the samples. The samples were pretreated using DS_Memmert Universal oven UF 110 (MEMMERT GmbH + Co. KG, Germany) (

Figure 1A) and vacuum dryer with a vacuum pump connection (Goldbrunn 1450, Zielona Gora, Poland) (

Figure 1B). The heating temperatures for both drying methods ranged from 40 °C to 90 °C with 10 °C intervals at a constant drying time of 60 min. The oven voltage ranges from 115 to 230V, 50/60 Hz and the electrical load of 1800 to 2800 W. The setting temperature ranges from +20 to 300 °C. The drying temperature and time were set using the control cockpit. The drying process time does not start until the set temperature is reached. The air circulation during the drying process was controlled by setting the fan and restrictor flap at 30%. On the other hand, the vacuum dryer was operated by first switching ON the vacuum pump at a 60 mbar. Afterwards, the vacuum dryer was also switched ON and the preset temperature (SV) was set. After the measured temperature (PV) had reached the preset temperature, the sample was loaded inside the dryer chamber. The vacuum drying process started at a pressure of 2.0·100 mbar. The heating time was controlled by a stopwatch. The vacuum dryer’s rated power is 1450 W. The temperature range is 50~250 °C with a heating rate of 6~8 °C per min.

2.4. Compression Tests

Samples were measured at 80 mm pressing height using the pressing vessel of diameter 60 mm with a plunger. The initial mass of flax samples was measured to be 171.07 g and hemp was 127.3 g. The samples’ volume was calculated to be 22.62·10

−4 m

3. The universal compression testing machine (ZDM 50, Czech Republic) of a maximum load of 500 kN together with the pressing vessel with a plunger was used for the oil extraction process (

Figure 1A,B). The compression rate was set at 5 mm/min. The force-deformation curves data were used to calculate the energy demand. The tests were repeated twice, and data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.5. Percentage Oil Yield

The oil yield was calculated as the ratio of the mass of oil to the mass of the sample multiplied by 100 using equation (2) [

28,

29] as follows:

where

is the oil yield (%),

is the mass of oil (g) calculated as the difference between the initial mass of the sample

(g) and mass of press cake (g). For each compression test, the press cake remains in the pressing vessel after the oil is recovered.

2.6. Energy Demand

The energy demand

was calculated based on the trapezoidal rule using equation (3) [

30,

31,

32,

33] as follows:

where

is the energy demand (N·m = Joules, J),

and

are the force (N) the deformation (mm = 10

−3 m),

n is the number of data points and

i is the number of sections in which the axis deformation was divided.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Following the standard hypothesis test procedure, the null

and alternative

hypotheses of the study were specified as follows;

: there is no lack of fit in the regression model and

: there is a lack of fit in the regression model. If the

P-value is smaller than the significance level alpha (α = 0.05), the null hypothesis is rejected in favour of the alternative. However, if the

P-value is larger than the significance level alpha (α = 0.05), the null hypothesis is not rejected (that is the null hypothesis is accepted while the alternative is rejected, or the alternative hypothesis is not supported). The experimental data were analyzed by employing the general linear regression technique at a 0.05 significance level using STATISTICA 13 [

34]. Graphical descriptions were also done using the same software.

3. Results and Discussion

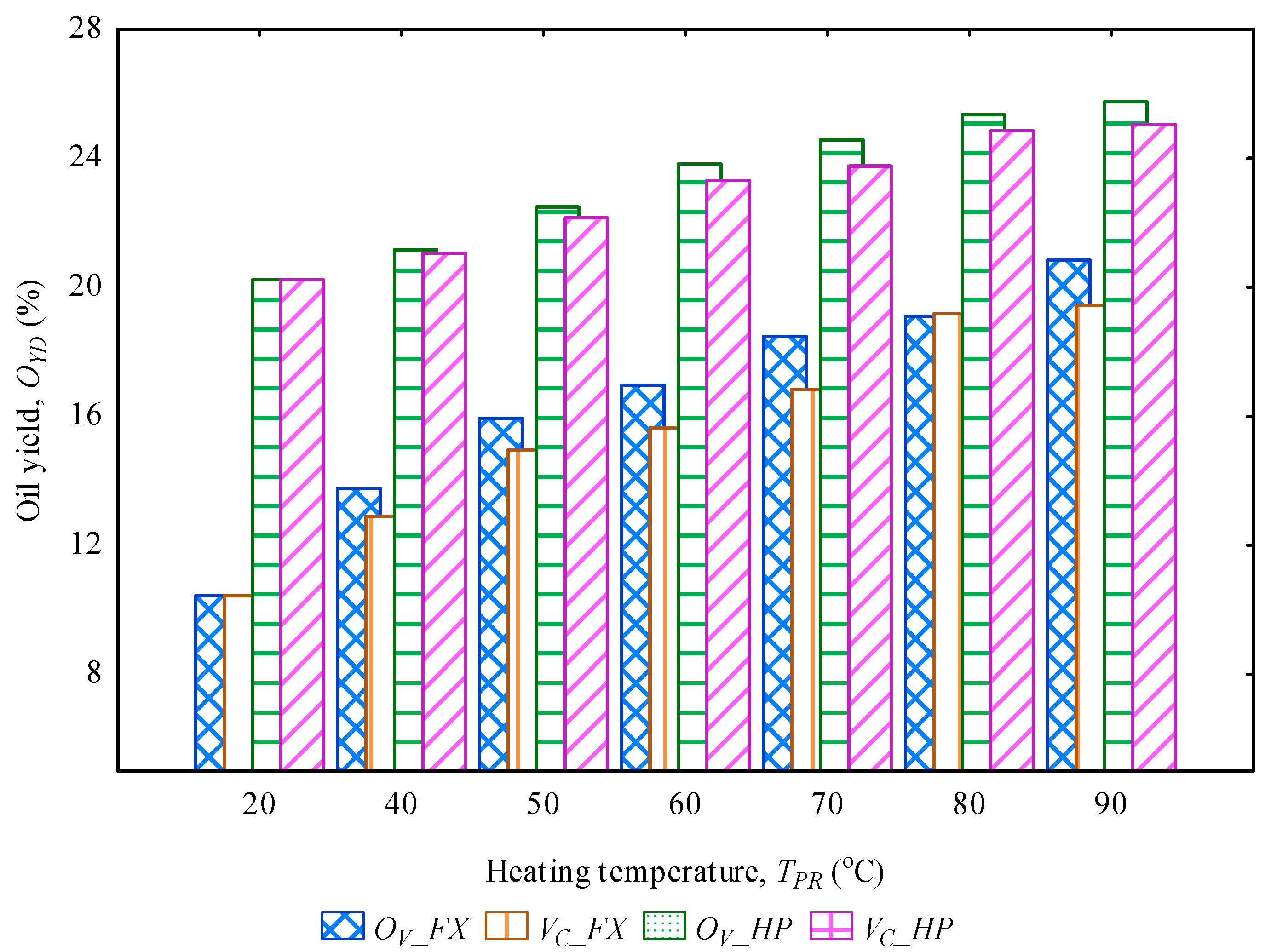

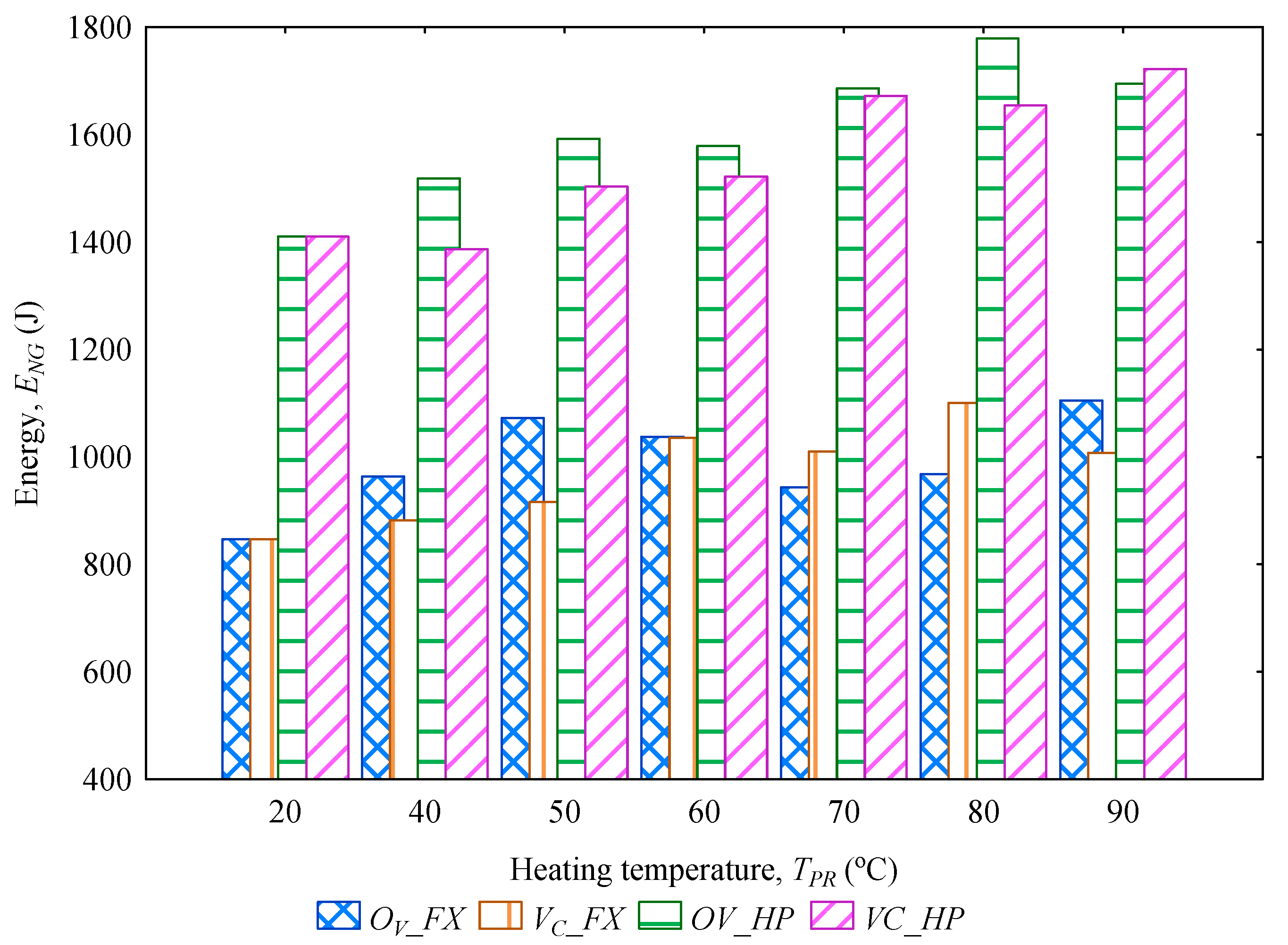

3.1. Percentage Oil Yield and Energy Demand of Bulk Flax and Hemp Oilseeds

The calculated amounts of percentage oil yield and energy demand of bulk flax and hemp oilseeds under oven

and vacuum

pretreatment conditions with heating temperatures are given in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The heating temperature of 20 °C served as the control whereas the heating temperatures between 40 °C and 90 °C were examined. Under

condition for bulk flax oilseeds, the percentage oil yield increased from 13.76 ± 0.15 to 20.84 ± 0.31% compared to the

where the percentage oil yield increased from 12.91 ± 0.37 to 19.44 ± 0.50%. The energy demand increased from 963.42 ± 30.41 J to 1105.20 ± 142.44 J under

and from 881.69 ± 91.86 J to 1100.24 ± 2.54 J under

. The percentage oil yield linearly increased under both drying conditions, but the energy demand showed both increasing and decreasing trends with the increase in heating temperature. The

increased the oil yield of bulk flax oilseeds by 1.02% compared to

method. This increment resulted in a higher energy demand of 23.06 J. For bulk hemp oilseeds under both drying conditions, the percentage oil yield increased from 21.16 ± 0.00 to 25.75 ± 0.07% in comparison with the

where the percentage oil yield increased from 21.06 ± 0.58 to 25.05± 0.36%. On the other hand, the energy demand increased from 1518.83 ± 2.35 J to 1778.96 ± 92.77 J under

and from 1386.52 ± 35.33 J to 1722.23± 121.69 J under

. The

increased the oil yield of bulk hemp oilseeds by 0.49% compared to

method. This increment resulted in a higher energy demand of 65.03 J. It was observed that bulk hemp oilseeds produced a higher percentage of oil yield with higher energy demand than bulk flax oilseeds under both drying conditions. The results in

Table 1 and

Table 2 are illustrated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

and

for flax oilseeds under

and

conditions.

|

(°C) |

Oven pretreatment, |

Vacuum pretreatment, |

|

(%) |

(J) |

(%) |

(J) |

| 20* |

10.43 ± 0.32 |

847 ±9.47 |

10.43 ± 0.32 |

847 ±9.47 |

| 40 |

13.76 ± 0.15 |

963.42 ± 30.41 |

12.91 ± 0.37 |

881.69 ± 91.86 |

| 50 |

15.95 ± 0.29 |

1072.19 ± 82.92 |

14.96 ± 0.38 |

916.27 ± 38.29 |

| 60 |

16.97 ± 0.95 |

1037.54 ± 15.23 |

15.64 ± 0.67 |

1035.31 ± 54.48 |

| 70 |

18.48 ± 0.53 |

943.16 ± 10.63 |

16.84 ± 1.10 |

1009.81 ± 98.11 |

| 80 |

19.11 ± 0.27 |

967.55 ± 20.25 |

19.19 ± 0.68 |

1100.24 ± 2.54 |

| 90 |

20.84 ± 0.31 |

1105.20 ± 142.44 |

19.44 ± 0.50 |

1007.36 ± 73.23 |

and

for hemp oilseeds under

and

conditions.

|

(°C) |

Oven pretreatment, |

Vacuum pretreatment, |

|

(%) |

(J) |

(%) |

(J) |

| 20* |

20.23 ± 0.64 |

1410.05 ± 77.49 |

20.23 ± 0.64 |

1410.05 ± 77.49 |

| 40 |

21.16 ± 0.00 |

1518.83 ± 2.35 |

21.06 ± 0.58 |

1386.52 ± 35.33 |

| 50 |

22.49 ± 0.27 |

1592.46 ± 20.63 |

22.15 ± 0.64 |

1503.26 ± 49.30 |

| 60 |

23.82 ± 0.16 |

1578.53 ± 69.28 |

23.31± 0.34 |

1521.48 ± 116.92 |

| 70 |

24.57 ± 0.26 |

1686.06 ± 26.21 |

23.76± 0.08 |

1671.99 ± 162.40 |

| 80 |

25.35 ± 0.18 |

1778.96 ± 92.77 |

24.85 ± 0.42 |

1654.28 ± 48.39 |

| 90 |

25.75 ± 0.07 |

1695.12 ± 72.43 |

25.05± 0.36 |

1722.23± 121.69 |

) and vacuum () pretreatment conditions.

) and vacuum () pretreatment conditions.

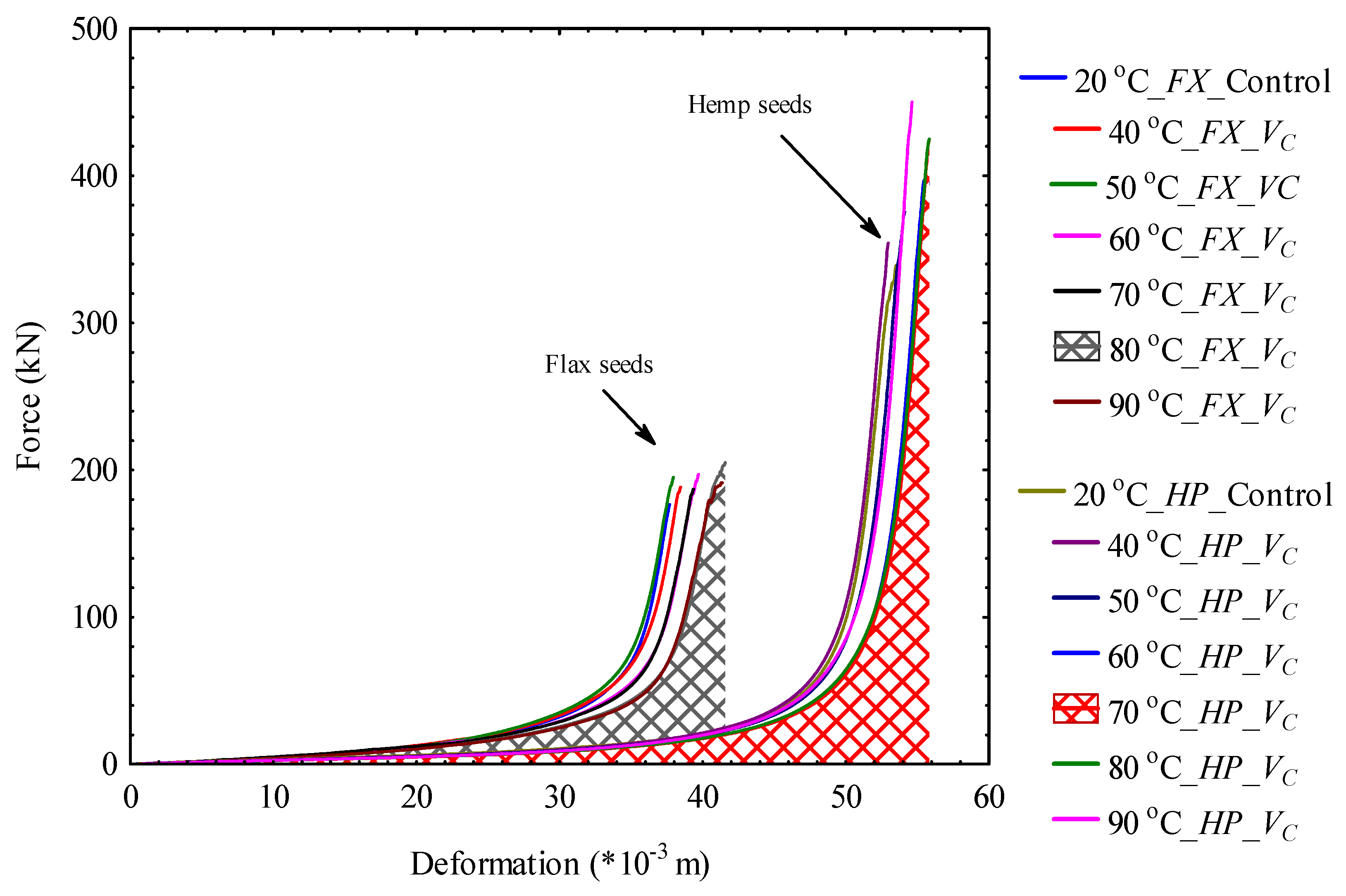

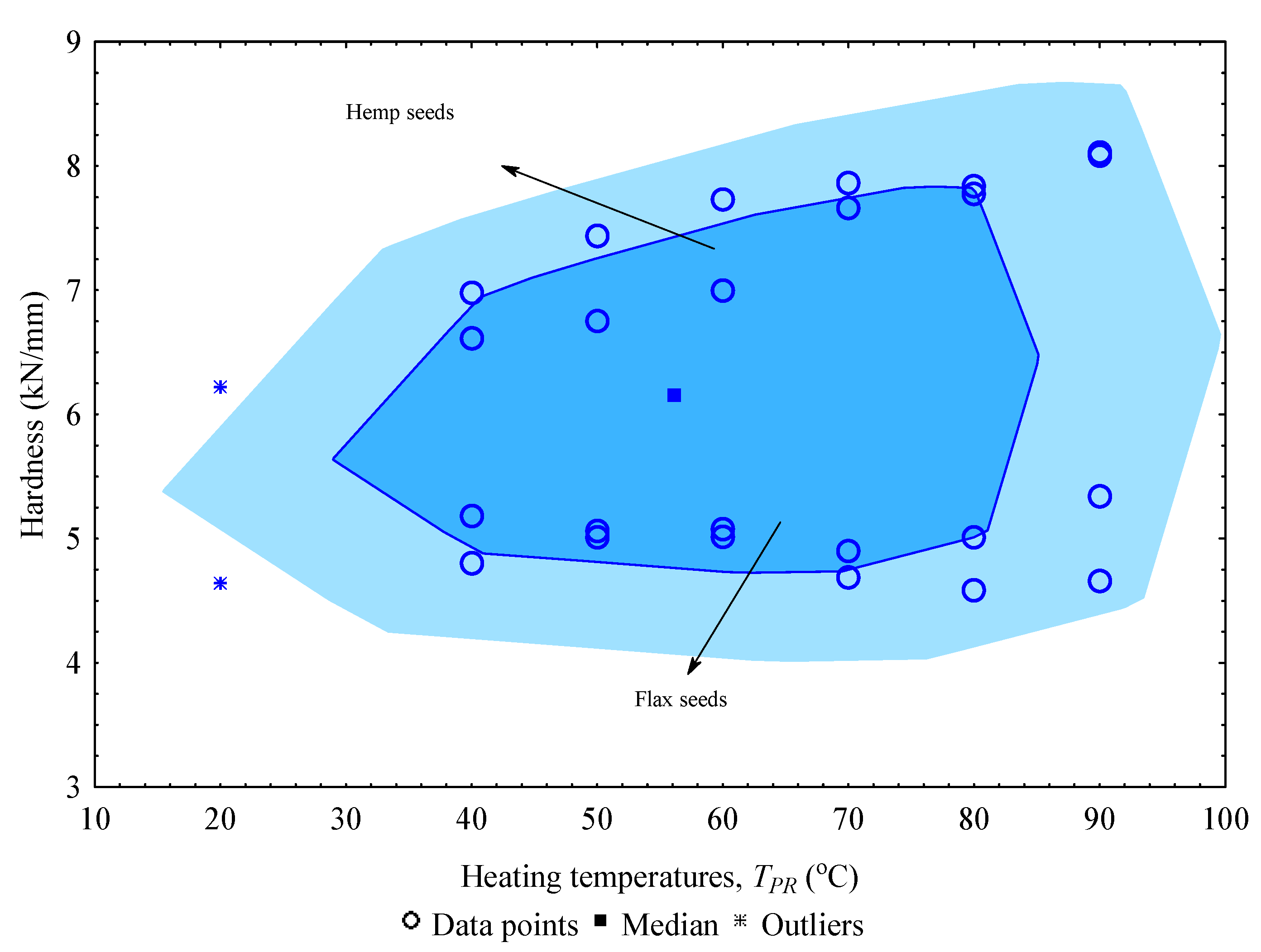

3.2. Force-Deformation Curves under

and

Pretreatment Conditions

The force-deformation curves of bulk flax and hemp oilseeds under

and

heating temperatures between 40 and 90 °C are illustrated in Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The area under the curve is the energy demand which was calculated according to equation (4). For all the tests conducted, the compressive force ranged from 174.97 ± 2.08 to 452.99 ± 3.97 kN with the corresponding deformation values from 37.70 ± 0.04 to 55.87 ± 0.40 mm. For bulk flax oilseeds under

, the maximum force of 206.33 ± 1.78 kN was observed at the heating temperature of 80 °C whereas 211.60 ± 40.35 kN was noticed at 90 °C under

. Contrary, bulk hemp oilseeds under both

and

, the compressive force increased linearly with the increase in heating temperatures. The maximum force of 452.99 ± 3.97 kN was observed under

whereas 443.54 ± 9.29 kN was produced under

. This observation indicates that higher force is required for compressing the oil from bulk hemp oilseeds than flax bulk oilseeds either at heating temperature increment or laboratory temperature. The higher force also corresponded to a greater hardness of the hemp seeds with an amount of 8.08 ± 0.23 kN/mm at 90 °C compared to 6.22 ± 0.16 kN/mm at the laboratory temperature of 20 °C. The hardness values for flax and hemp seeds are displayed in

Figure 6. The hardness was calculated from the ratio of the force to the deformation [

25,

33]. The force and the hardness values for bulk flax and hemp seeds were significant (P < 0.05) but that of deformation was insignificant (P > 0.05) under

and

heating temperatures.

heating temperatures (the area under the curve is the energy demand).

and heating temperatures.

3.3. Evaluation of Statistical Analysis Outcome of Calculated Parameters Under

and

The statistical outcome of the calculated parameters or dependent variables (percentage oil yield and energy demand) for both bulk flax and hemp oilseeds under oven

and vacuum

heating temperatures are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The results show that the effect of heating temperature (predictor variable) on the dependent variables was significant (P-value < 0.05). A positive linear relationship was found between the predictor variable and the dependent variables under both pretreatment conditions. The dependent parameters for bulk flax oilseeds under oven and vacuum pretreatment conditions produced correlation coefficient values between 0.549 and 0.987 whereas the same parameters for bulk hemp oilseeds indicated correlation coefficient values between 0.813 and 0.981.

(%) under

.

| |

: Oil yield (%) under : Oven pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

146.4650 |

146.4650 |

450.8847 |

0.0000* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

3.8981 |

0.3248 |

|

|

| Lacko of Fit |

5 |

2.3441 |

0.4688 |

2.1118 |

0.1786** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

1.553992 |

0.221999 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

150.3631 |

|

|

|

| |

: Oil yield (%) under : Vacuum pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

124.8500 |

124.8500 |

309.0554 |

0.0000* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

4.8477 |

0.4040 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

5 |

2.0877 |

0.4175 |

1.0590 |

0.4549** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

2.7599 |

0.3943 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

129.6977 |

|

|

|

| |

: Energy (J) under : Oven pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

36510 |

36510 |

5.1732 |

0.0421* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

84691 |

7058 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

5 |

55756.14 |

11151.23 |

2.6977 |

0.1141** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

28935.28 |

4133.611 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

121202 |

|

|

|

| |

: Energy (J) under : Vacuum pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

74021 |

74021 |

16.4604 |

0.0016* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

53963 |

4497 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

5 |

26007.08 |

5201.415 |

1.302422 |

0.3614** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

27955.54 |

3993.649 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

127983 |

|

|

|

: Heating temperature, df: degrees of freedom; * P-Value < 0.05 denotes significant; ** P-Value > 0.05 denotes non-significant.

(%) under

.

| |

: Oil yield (%) under : Oven pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

52.0477 |

52.0477 |

310.6972 |

0.0000* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

2.0102 |

0.1675 |

|

|

| Lacko of Fit |

5 |

1.3929 |

0.2786 |

3.1591 |

0.0829** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

0.6173 |

0.0882 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

54.0580 |

|

|

|

| |

: Oil yield (%) under : Vacuum pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

39.8145 |

39.8145 |

183.610 |

0.0000* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

2.6021 |

0.2168 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

5 |

1.0108 |

0.2022 |

0.8893 |

0.5353** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

1.5913 |

0.2273 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

42.4166 |

|

|

|

| |

: Energy (J) under : Oven pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

159563 |

159563 |

39.4589 |

0.0000* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

48525 |

4044 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

5 |

22751.01 |

4550.203 |

1.2358 |

0.3847** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

25774.19 |

3682.027 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

208088 |

|

|

|

| |

: Energy (J) under : Vacuum pretreatment |

| Source |

df |

Sum of squares |

Mean Squares |

F-Value |

P-Value |

|

(°C) |

1 |

182523 |

182523 |

23.3756 |

0.0004* |

| Residual Error |

12 |

93699 |

7808 |

|

|

| Lack of Fit |

5 |

26821.56 |

5364.313 |

0.561481 |

0.7281** |

| Pure Error |

7 |

66877.10 |

9553.872 |

|

|

| Total |

13 |

276221 |

|

|

|

: Heating temperature, df: degrees of freedom; * P-Value < 0.05 denotes significant; ** P-Value > 0.05 denotes non-significant.

3.4. Determined Regression Models for

and

Under

and

Based on the results presented in

Table 1 and

Table 2 above, for bulk flax oilseeds (FX), the regression models for determining the calculated parameters are provided in equations (4) to (7) and for bulk hemp (

HP) oilseeds in equations (8) to (11) (

Table 5). Each equation represents the conditions of the hypotheses specified in section 2.7. Since the P-value of the lack of fit is greater than 0.05, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected, or the alternative hypothesis is not supported indicating that there is no lack of fit in the regression models established. The regression models thus correspond to the scatterplots depicted in

Figure 7 explains that the increase in heating temperature linearly increased the percentage oil yield and energy demand of bulk flax and hemp oilseeds under oven and vacuum pretreatment conditions.

and .

Regression

models

3.5. Paired t-Test of the Calculated Parameters under

and

The calculated parameters (percentage oil yield, energy demand, compressive force, deformation, and hardness) under and were subjected to paired t-test analysis to establish the statistically significant differences between the means at α = 0.05. For flax seeds oil yield under and , the two-tail P-value of 0.01 was less than 0.05, hence the null hypothesis was rejected in favour of the alternative implying that the means of oil yield under is not equal to that of the means under . A similar observation was found for the oil yield of bulk hemp oilseeds. On the other hand, the alternative hypothesis was not supported in the case of the energy demand for both bulk flax and hemp oilseeds because the P-value of 0.61 was greater than the significant level of 0.05. The force, deformation and hardness results also show that there is evidence to conclude that their means under and were not significantly different from each other based on the P-value being greater than 0.05 which was supported by the null hypothesis that the means of those parameters under and were equal.

3.6. Effect of Moisture Content and Other Input Factors during Oil Extraction Processes

The moisture content of flaxseed and hemp seed was found to be 6.18 ± 1.79 and 7.12 ± 0.91% w.b. The moisture content of oilseeds plays an important role in the oil extraction process [

4]. Lower moisture content of seed increases friction whereas higher moisture content acts as a lubricant during the pressing operation [

24,

35,

36,

37]. Choking of the seeds or seedcake occurs with a lower seed moisture content. On the contrary, higher moisture content increases plasticity, thereby reducing the level of compression and contributing to poor oil recovery [

24,

37,

38,

39]. The quality of the oil is also affected by moisture content. A lower moisture content increases chlorophyll and phospholipids content in the oil. Conversely, sulphur, calcium and magnesium contents in the oil increase at a higher moisture content [

24,

39,

40,

41]. The heating temperature, pressing speed, vessel diameter, nozzle diameter, screw shaft diameter, compressive force/pressure, sample pressing height, particle size and input energy are other input factors that affect the oil yield under linear or non-linear compression processes [

24,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Higher screw speed results in higher speed of material throughput leading to higher residual oil content in the press cake since less time is available for the oil to drain from the solids [

24,

47,

51]. At a higher speed the viscosity thus remains lower resulting in less pressure build-up and more oil content in the press cake [

47,

49,

50,

51]. Higher pressure will lead to higher temperature generation and higher oil recovery efficiency [

49,

50]. Lower energy input means lower oil recovery efficiency, higher oil residue in press cake and higher speed material throughput [

51]. Theoretically, oil yield would be increased with the increase in heating temperature and pressure. However, under a certain level, the increase in heating temperature and pressure will probably decrease the percentage of oil yield [

28,

45,

52,

53]. The authors further explained that the decrease in oil yield at higher heating temperatures could be due to the change in moisture content and structural changes of the oilseed material during the heating process. In addition, the increase in heating temperature to a certain level will reduce the moisture content of the seeds thus resulting in a reduction in water content. This reduction of moisture content will not be able to help in breaking/cracking the seed cell which thus results in lower percentage oil yield. On the other hand, a smaller pressing vessel diameter in the case of the linear compression process, and a smaller nozzle size and screw shaft diameter in the case of mechanical screw press would provide higher pressure towards the seeds for higher oil yield compared to bigger sizes or diameters which allow larger space for the seeds to be filled, hence less pressure is provided towards the seeds resulting into lower oil yield [

28].

4. Conclusions

Heating temperatures ranging from 40 °C to 90 °C were investigated for bulk flax and hemp oilseeds under oven and vacuum drying methods. Compressive force, deformation, hardness, percentage oil yield and energy demand were calculated from the compression tests at a pressing rate of 5 mm/min using the pressing vessel of diameter 60 mm with a plunger by applying a maximum compressive force of 500 kN to the initial samples pressing height of 80 mm representing a sample volume of 22.62·10−4 m3. The force-deformation curves were described where the energy demand was calculated from the area under the curve. The compression data obtained for bulk flax oilseed pretreatments with varying heating temperatures showed that the means of compressive force under oven and vacuum drying methods ranged from 194.37 to 192.36 kN. The deformation values ranged from 39.47 to 39.48 mm. The hardness values ranged from 4.93 to 4.87 kN/mm. The oil yield ranged from 16.51 to 15.63% and the energy demand ranged from 990.87 to 971.09 J. The data for bulk hemp oilseeds also showed that the means of compressive force under both drying methods ranged from 402.78 to 392.57 kN. The deformation values ranged from 54.08 to 54.75 mm. The hardness values ranged from 7.45 to 7.17 kN/mm. The oil yield ranged from 23.34 to 22.92% and the energy demand ranged from 1608.57 to 1552.83 J. Based on the hypothesis testing using the t-test for paired two samples for means, only the means of oil yield of the flax and hemp oilseeds significantly differed (P < 0.05) from each other under the pretreatment methods whereas their means of compressive force, deformation and energy were not statistically different from other. It was evident that a higher percentage of oil yield from bulk flax and hemp oilseeds was produced in the oven than vacuum drying methods. However, their corresponding energy demands were not significantly different (P > 0.05) under both drying methods. A study on the relaxation force and time curves should be performed to determine the residual oil in the seedcake after the compression process. Several oilseeds should be examined under various pretreatment methods and to assess their oil quality indicators, fatty acid compositions, sensory and UV-spectral properties. The energy consumption of the drying methods for the pretreatment of the oilseeds before oil processing should also be determined.

Author Contributions

A. Kabutey: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Visualization, Validation, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. S. H. Kibret: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. A. W. Kiros: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. M. A. Afework: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. M. Onwuka: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. A. Raj: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported financially by the Internal Grant Agency of the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague (IGA Project Number – 2023:31130/1312/3110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dunford, N.T. Enzyme-aided oil and oilseed processing: opportunities and challenges. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 48, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevara, G.A.; Ibrahim, S.G.; Muhammad, S.K.S.; Zawawi, N.; Mustapha, N.A.; Karim, R. Oilseed meals into foods: an approach for the valorization of oilseed by-products. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 6330–6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, K.J.; Wu, T.Y. Second-generation bioenergy from oilseed crop residues: Recent technologies, techno-economic assessments and policies. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 267, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Che, L. Effects of different drying methods on the extraction rate and qualities of oils from demucilaged flaxseed. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S.; Singh, B.; Kaur, A. Infrared pretreatment for improving oxidative stability, physiochemical properties, phenolic, phytosterol and tocopherol profile of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 206, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Shen, X.; Wu, L. Microwave pretreatment of hemp seeds changes the flavor and quality of hemp seed oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 213, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, D.; Wang, L. J.; Huang, Z. G.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X. D.; Mao, Z. H. Effect of Moisture Content on the Physical Properties of Fibered Flaxseed. Int. J. Food Eng. 2007, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eržen, M.; Čeh, B.; Kolenc, Z.; Bosancic, B.; Čerenak, A. Evaluation of different hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) progenies resulting from crosses with focus on oil content and seed yield. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 201, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholivand, S.; Tan, T.B.; Yusoff, M.M.; Choy, H.W.; Teow, S.J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, C.P. An in-depth comparative study of various plant-based protein-alginate complexes in the production of hemp seed oil microcapsules by supercritical carbon dioxide solution-enhanced dispersion. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 153, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassab, Z.; Abdellaoui, Y.; Salim, M.H.; Bouhfid, R.; Achaby, M. E. Micro-and nano-celluloses derived from hemp stalks and their effect as polymer reinforcing materials. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 245, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgih, A.T.; Alashi, A.; He, R.; Malomo, S.; Aluko, R.E. Preventive and treatment effects of a hemp seed (Cannabis sativa L.) meal protein hydrolysate against high blood pressure in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur. J. Nutr. 1246. [Google Scholar]

- Du, S.; Zhao, Z.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Tong, N.; Che, Q.; Wang, J. Preparation of natural antibacterial regenerated cellulose fibre from seed-type hemp. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 208, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravotto, C. ; Fabiano-Tixier, A-S.; Bartier, M.; Claux, O.; Tabasso, S. Green extraction of hemp seeds cake (Cannabis sativa L.) with 2-methyloxolane: A response surface optimization study. Sustain. Chem. Pharm.

- Hu, H.; Liu, H.; Shi, A.; Liu, L.; Fauconnier, M.L.; Wang, Q. The Effect of Microwave Pretreatment on Micronutrient Contents, Oxidative Stability and Flavor Quality of Peanut Oil. Molecules, 2018, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanyo, P.; Meeso, N.; Kaewseejan, N.; Siriamornpun, S. Effects of Drying Methods and Enzyme Aided on the Fatty Acid Profiles and Lipid Oxidation of Rice By-Products. Dry. Technol. 2015, 34, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Yang, X.; Fu, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Qiao, X. Effects of Three Conventional Drying Methods on the Lipid Oxidation, Fatty Acids Composition, and Antioxidant Activities of Walnut (Juglans regia L.). Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, S.; Ucak, I.; Jain, S.; Elsheikh, W.; Redha, A.A.; Kurt, A.; Toker, O.S. Impact of drying on techno-functional and nutritional properties of food proteins and carbohydrates – A comprehensive review. Dry. Technol. 2024, 42, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.H.; Welsh, Z.; Gu, Y.; Karim, M.A.; Bhandari, B. Modelling of simultaneous heat and mass transfer considering the spatial distribution of air velocity during intermittent microwave convective drying. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 153, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Liu, H.; Xie, Y.; Liao, Q.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xio, H.; Gao, Z.; Liu, S. Postharvest processing and storage methods for Camellia oleifera seeds. Foods Rev. Int. 2019, 36(4), 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghannya, J.; Hosseinlar, S. H.; Heshmati, M. K. Multi-Stage Continuous and Intermittent Microwave Drying of Quince Fruit Coupled with Osmotic Dehydration and Low Temperature Hot Air Drying. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg Technol. 2018, 45, 132–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemis, M.; Watson, D.; Gariepy, Y.; Lyew, D.; Raghavan, V. Modelling study of dielectric of seed to improve mathematical modelling for microwave-assisted hot-air drying. J Microw Power Electromagn Energy. 2019, 53, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigrahi, S.; Rana, A.; Meda, V.; Chang, P. R. Microwave-Vacuum Drying of Flax Fiber for Biocomposite Production. J Microw Power Electromagn Energy. 2016, 43, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwude, D. I.; Hashim, N.; Janius, R.; Abdan, K.; Chen, G.; Oladejo, A. O. Non-Thermal Hybrid Drying of Fruits and Vegetables: A Review of Current Technologies. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg Technol. 2017, 43, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabutey, A.; Herák, D.; Mizera, Č. Assessment of quality and efficiency of cold-pressed oil from selected oilseeds. Foods. 2023, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabutey, A.; Mizera, Č.; Herák, D. Evaluation of percentage oil yield, energy requirement and mechanical properties of selected bulk oilseeds under compression loading. J. Food Eng. 2024, 360, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

IS:3579; Indian Standard Methods for Analysis of Oilseeds. Indian Standard Institute: New Delhi, India, 1996.

- Blahovec, J. Agromaterials Study Guide; Czech University of Life Sciences Prague: Prague, Czech Republic, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Deli, S.; Farah Masturah, M.; Tajul Aris, Y.; Wan Nadiah, W.A. The effects of physical parameters of the screw press oil expeller on oil yield from Nigella sativa L. seeds. Int. Food Res. J. 2011, 18, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar]

- Chanioti, S.; Tzia, C. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of oil from olive pomace using response surface technology: Oil recovery, unsaponifiable matter, total phenol content and antioxidant activity. LWT – Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysiak, G. Fracture toughness of pea: Weibull analysis. J. Food Eng. 2007, 83, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakespari, A.G.; Rajabipour, A.; Mobli, H. Strength behaviour study of apples (cv. Shafi Abadi & Golab Kohanz) under compression loading. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2010, 4, 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Sedlacek, A.; Gurdil, G. Mechanical behaviour of several layers of selected plant seeds under compression loading. Res. Agric. Eng. 2012, 58, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divisova, M.; Herak, D.; Kabutey, A.; Sigalingging, R.; Svatonova, T. Deformation curve characteristics of rapeseeds and sunflower seeds under compression loading. Sci. Agric. Bohem. 2014, 45, 180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Statsoft Inc. STATISTICA for Windows, T: Inc, 2013.

- Hoffmann, G. The Chemistry and Technology of Edible Oils and Fats and Their High-Fat Products. Academic Press, New York, 1989, 63–68.

- Reuber, M.A. New technologies for processing Crambe abyssinica. Retrospective Theses and Dissertations, 1992. https://lib.dr.iastate. 1762. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.K.; Wiesenborn, D.P.; Tostenson, K.; Kangas, N. Influence of moisture content and cooking on screw pressing of crambe seed. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2002, 79, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Bargale, P.C. Development of a small capacity double stage compression screw press for oil expression. J. Food Eng. 2000, 43, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, M.A.F.M.; Mansour, M.P.; Trujillo, F.J.; Juliano, P. Microwave pre-treatment of canola seeds and flaked seeds for increased hot expeller oil yield. J. Food. Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, R.L.; Cermak, S. Full-press oil extraction of Cuphea (PSR23) seeds. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2007, 84, 1169–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoire, R.; Lanoiselle, J.-L.; Vorobiev, E. Mechanical continuous oil expression from oilseeds: A review. Food Bioprocess Tech. 2013, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L.M.; Hanna, M.A. Expression of oil from oilseeds – a review. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1983, 28, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrema, G.C.; McNulty, P.B. Mathematical model of mechanical oil expression from oilseeds. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1985, 31, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajibola, O.O.; Adetunji, S.O.; Owolarafe, O.K. Oil point pressure of sesame seeds. Ife J. Sci. Technol. 2000, 9, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Baryeh, E.A. Effect of palm oil processing parameters on yield. J. Food Eng. 2001, 48, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayanju, T.M.A.; Akinoso, R.; Oresanya, M.O. Effect of wormshaft speed, moisture content and variety on oil recovery from expelled beniseed. Agric. Eng. Int. the CIGR Ejournal, 2006, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Beerens, P. Screw-pressing of Jatropha seeds for fueling purposes in less developed countries. MSc Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mwithiga, G.; Moriasi, L. A study of yield characteristics during mechanical oil extraction of preheated and ground soybeans. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2007, 3, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Willems, P.; Kuipers, N.J.M.; De Haan, A.B. Hydraulic pressing of oilseeds: Experimental determination and modeling of yield and pressing rates. J. Food Eng. 2008, 89, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, P.; Kuipers, N.J.M.; de Haan, A.B. A consolidation based extruder model to explore GAME process configurations. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaj, S.; Muller, J. Optimizing mechanical oil extraction of Jatropha curcas L. seeds with respect to press capacity, oil recovery and energy efficiency. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 34, 1010–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeeko, K.A.; Ajibola, O.O. Processing factors affecting yield and quality of mechanically expressed groundnut oil. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1990, 45, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzat, K.O.; Clarke, B. Prediction of oil yields from groundnuts using the concept of quasi-equilibrium oil yield. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1993, 28, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).