1. Introduction

Tennis is considered one of the most demanding sports in the glenohumeral joint

[1]. Technical requirements in tennis needs the development of kinetic chains from de ground to the racket to generate force when hitting the ball. In this kinetic chain the glenohumeral joint of the dominant shoulder plays a vital role in the preparation, acceleration, and follow-through phases of a tennis stroke. A greater range of glenohumeral rotation in the dominant shoulder may be beneficial for tennis players

[1].

The shoulder is a joint complex, has a great mobility and it is static, and dynamic stability depends on the synchronized action of rotator cuff muscles and capsuloligamentous structures

[2,3]. The demands on these structures are even higher during the practice of sports such as tennis, volleyball, baseball, and swimming. Although these sports have different characteristics, they show similar movement patterns and subject the shoulder and the upper limb to repeated overhead movements (overhead sports)

[4,5]. The repetitive storks that tennis players must make in every practice and match, with a lot of power and acceleration can cause tightness and compromise the internal rotation ROM of the dominant shoulder, in comparison with the nondominant side and to imbalances in the muscle strength

[6,7,8].

The numerous serves throughout a tennis match can cause recurrent microtrauma and may lead to physiological adaptations of the joint as well as of the joint’s surrounding soft tissue

[9]. A permanent tightness of the posterior rotator cuff, muscles and tendons, lead to alterations in scapular and humeral kinematics and in a stable change in shoulder motion of tennis athletes

[10]. These physiological adaptations often result in a decreased internal rotation (IR) range of motion (ROM) of the glenohumeral joint combined with a decreased total range of motion (TROM) of the dominant compared to the nondominant limb

[10]. Previous study stated that playing overhead sports, in which an action like the overhead movement of the pitcher is repeated, was the risk factor for GIRD. Thus, appropriate prevention or early intervention may be necessary for all overhead sports players

[11,12]

The glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) is defined as a decrease in the internal rotation range of the dominant shoulder compared with the non-dominant shoulder

[13,14]. This glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD), however, is associated with an increased risk for shoulder injuries and might have an impact on the performance of youth tennis players

[9,10]. Most of studies of the shoulders in overhead athletes are focused on baseball pitchers or other throwing athletes. Nevertheless, the technical requirement and the injury ethology in the pitchers is very different than tennis players

[15].

Current literature differentiates between an anatomical GIRD and a pathological GIRD. Most commonly, an anatomical GIRD is defined as a loss of IR greater than 18°-20° compared to the contralateral shoulder

[16,17]. In addition, other authors defined a pathological GIRD as the loss of glenohumeral IR combined with a loss in TROM greater than 5 degrees

[13]. These GIRD descriptions are specific to pitchers

[13,16,17,18] and for tennis players we defined a bilateral internal rotation deficit is considered to exist when the significant difference between the internal rotation of the dominant and non-dominant shoulder is 20% greater than the total internal rotation amplitude or 10% of the total range of motion of the joint will increase the risk of injury by a factor of two. On the other hand, only a 5° difference in total range of motion in full rotation between the dominant and non-dominant shoulder increases the risk of injury. Moreover, several authors state that GIRD could be develop after long period of a restriction in the glenohumeral external rotation range of movement (GERD). Nevertheless, there are few studies focus on describing the problems that GERD could cause to overhead athletes

[19,20,21].

Shoulder injuries are the most common upper limb injuries in tennis players

[6,10,22,23]. Most of them are in the dominant shoulder and have an incidence of 8.2 injuries per 1000 playing hours in tennis matches, accounting for 15,9% of all overuse injuries in elite junior tennis players (11). Especially youth athletes show chronic overuse disorders and a higher risk for acute injury as possible implication of repetitive stress on the glenohumeral joint during growing periods

[10,11,22].

IR decreases with age, with a parallel decrease in the total arc of motion (TROM) in the dominant side when compared to the non-dominant side

[9]. Moreover, absolute/normalized shoulder strength values were higher in the dominant side compared to the non-dominant side, and values increased with age, although studies showed some discrepancies, especially related to the biological age or when strength data are normalized

[11,24]. Nevertheless, a loss of glenohumeral internal rotation on the dominant side in youth tennis players is given and is progressive with increasing years of tennis practice and independently associated with the history of injuries in the dominant side. Therefore, that changes in rotational shoulder ROM are not dependent on age, depend on years of tennis practice

[10,15]

Shoulder range of motion (ROM) assessment in tennis players have been recommended because is essential for evaluating the muscular conditions

[25], to maintain a healthy shoulder rotation and reduce the risk of shoulder injury

[1,10,11,26]. Since healthy glenohumeral rotation may be beneficial to the biomechanics of the tennis stroke and prevention of shoulder injury, the junior tennis players in particular need periodic surveillance of shoulder ROM

[1,11]. Previous studies agreed with the importance to analyze the joint in the position that most closely resembles the specific tennis movements to obtain more accurate information on the functionality of the joint

[8,27]. Furthermore, regarding the side-to-side asymmetries, the dominant shoulder reported adaptations of shoulder ROM, with reduction of the IR and TROM, and an increase in the ER when compared with the non-dominant side

[8]. Although most studies of the shoulders of overhead sports players were tested in a shoulder position of 90

° of abduction, although most demanding strokes in tennis are developed at 45

° [1,12,13].

In tennis, the recommended ER/IR strength ratio ranges between 61-76%, meaning that ER should have at least 2/3 of the IR strength

[8]. In this regard, a muscle imbalance in the ER/IR ratio together with weak ER in the dominant shoulder have an impact on the dominant rotation ROM and have been associated with a high risk of shoulder pain in overhead athletes, including tennis players

[8].

To obtain accurate and reliable results, researchers had used the goniometer as a tool to calculate the range of motion of a joint. The goniometer has been the most widely used tool to calculate ROM passively, as it is easy to use, inexpensive and has proven its validity

[28]. An important concept to note regarding the measurement of glenohumeral motion is scapular stabilization to ensure isolated glenohumeral motion. Previous studies assessed three methods of glenohumeral internal rotation measurement (no stabilization, humeral head stabilization and scapular stabilization). The most reliable method was with scapular stabilization

[28]. Nevertheless, the twohanded requirement of using a goniometer makes difficult to stabilize the trunk and scapula, resulting in an increased likelihood of measurement error

[12,25,29,30]. Goniometers, when used correctly, can accurately measure ROM, however measurement quality is influenced by the tester’s manual skills and methods used

[30]. In recent years, the popularity of commercially available motion tracking devices has increased the use of wearable motion capture systems to measure ROM. Inertial measurement units (IMUs) are one type of motion tracking device that have been widely adopted due to their ease of use, relative low cost, and portability

[30].

Current test to assess glenohumeral rotational range of motion are developed at 90

° of glenohumeral abduction

[1,8,10,15,24,31,32]. Nevertheless, most of the powerful actions in tennis are developed at 45

° of abduction

[24,32]. Moreover, to our knowledge, there is a lack of studies that consider the possible differences in ER or GERD and GIRD actively and passively at 90

° and 45

° of abduction. Understanding the tennis specific adaptations of the shoulder complex could help tennis players, coaches, athletic trainers and clinicians to design optimal exercise protocols. Therefore, the aim of this study is establishing baseline models of pathological GIRD and GERD in tennis players, to determine the differences between the passive and active rotational range of motion of the glenohumeral joint at 90° and 45

° of abduction.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this study presents for the first time reference data for the glenohumeral rotation at 45° and 90° actively and passively, and different types of GIRDs and GERDs in tennis players. This highlights the need for having a reference values more specific than most of the evaluations in the previous studies. It’s reported that specific information regarding the bilateral comparisons of normal range of motion in healthy, uninjured athletes is of importance as these comparisons often are used in clinical decisions on the extent and magnitude of range of motion loss and subsequent strategies to regain motion after injury or surgery[

13,

15,

36].

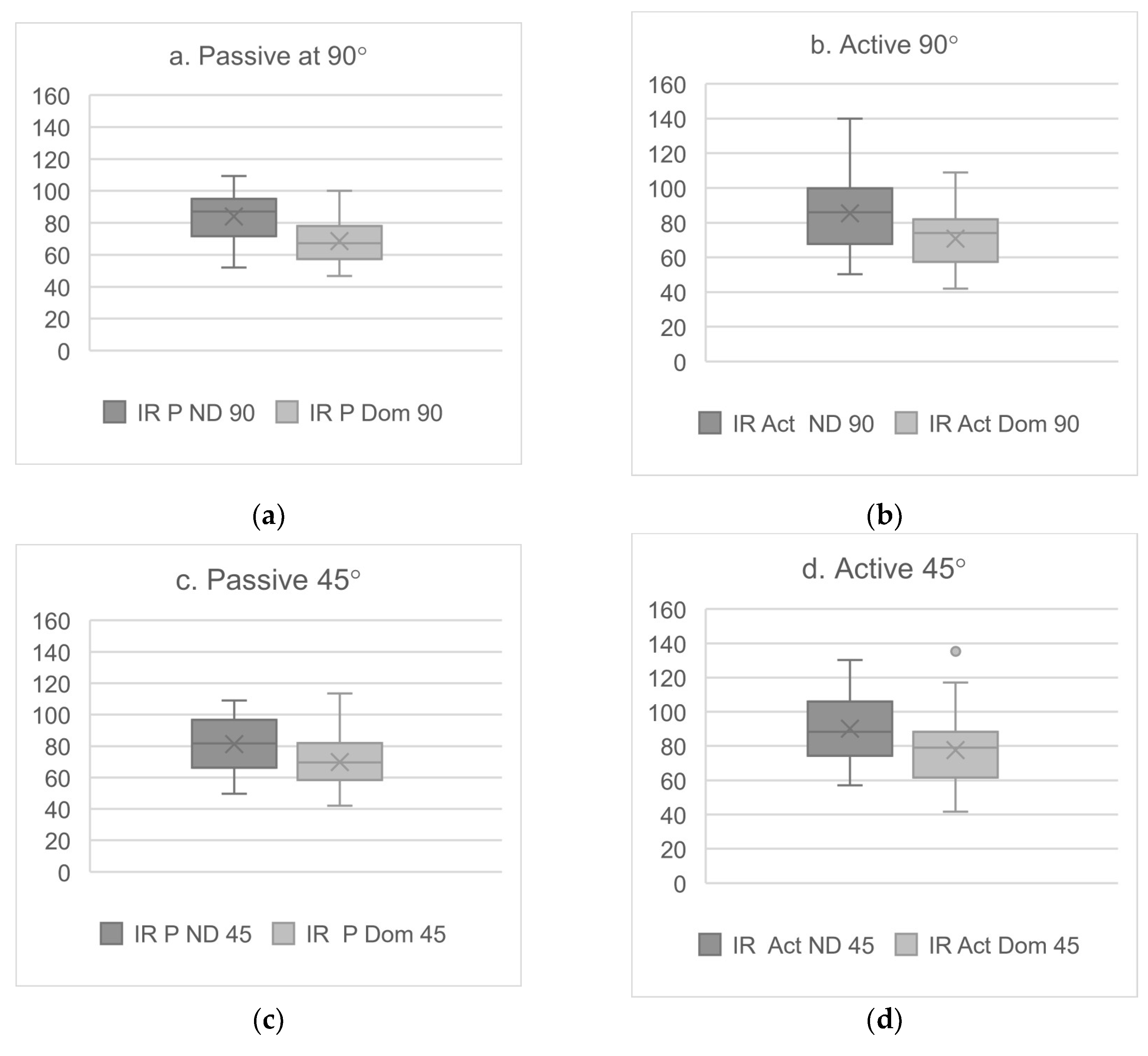

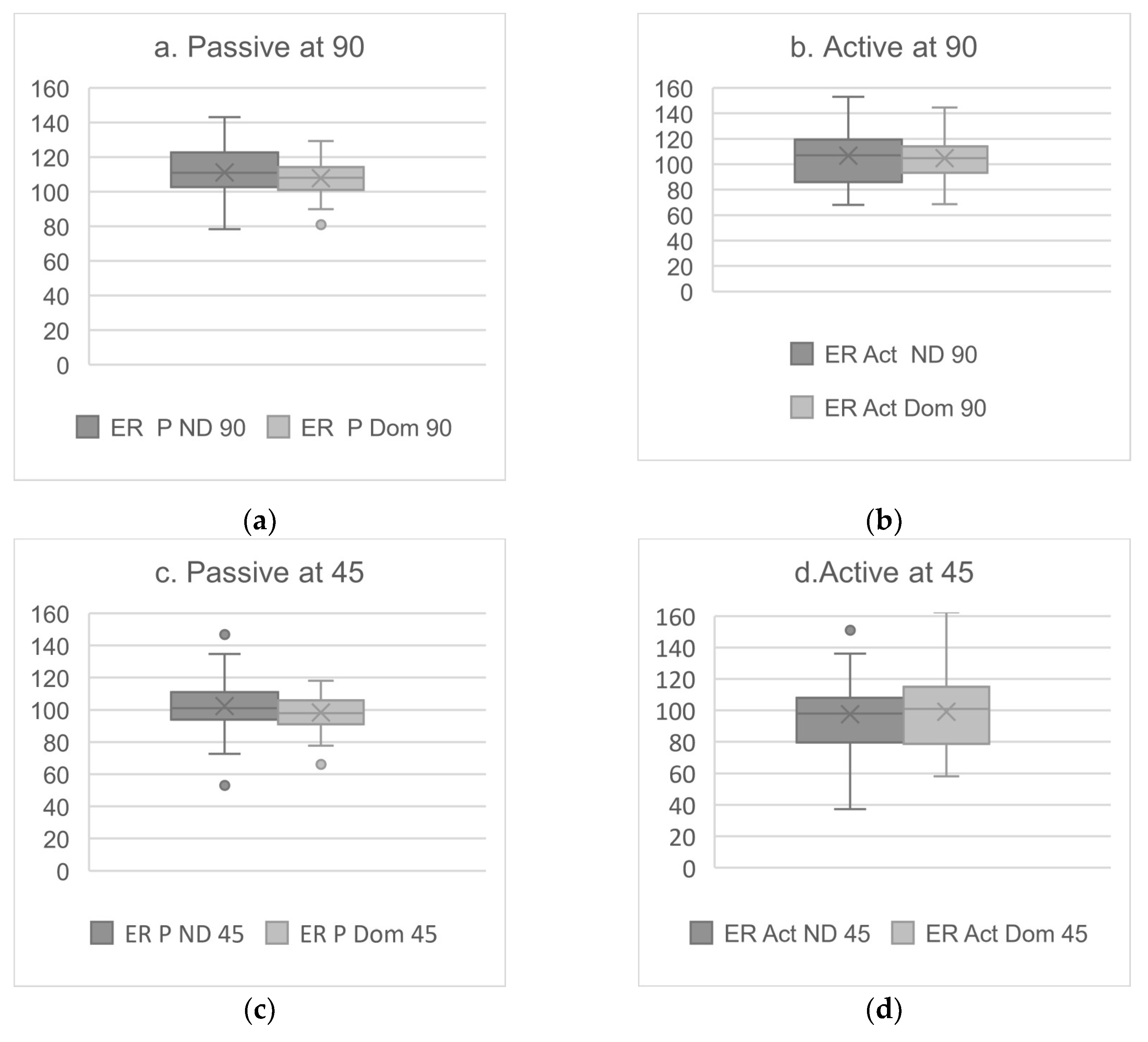

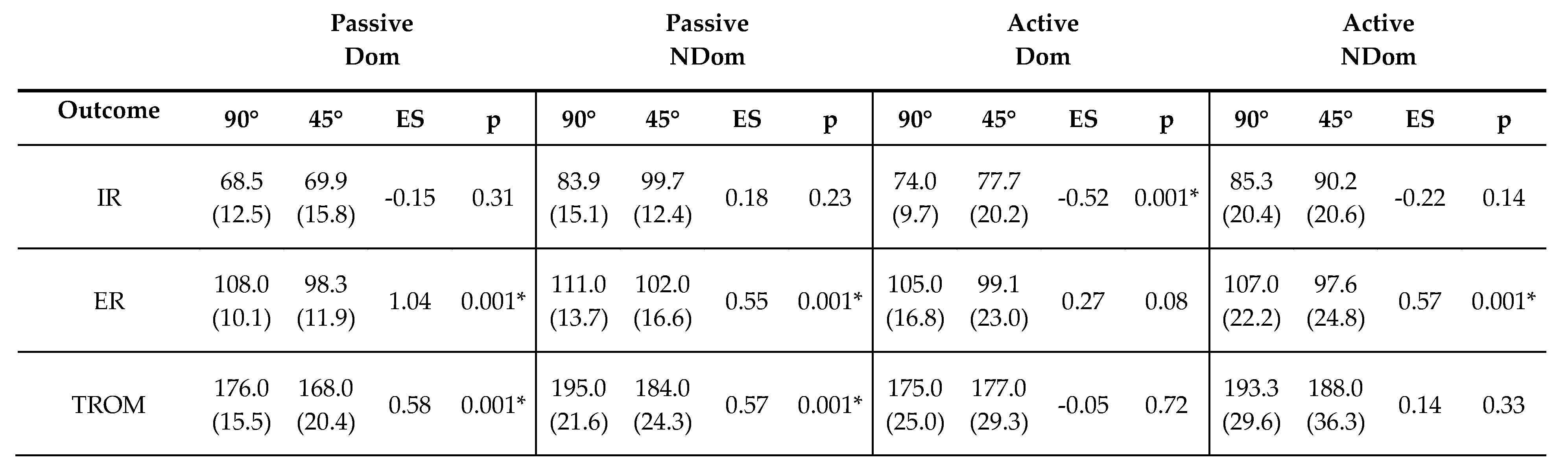

The results in the present study showed significant differences for all rotational movements between dominant and non-dominant side (

Figure 2 and 3). In line with previous research on tennis players, IR was significantly lower in dominant side [

31,

32,

34,

37,

38]. In contrast, ER degrees were not greater in the dominant side (

Figure 3). These differences could be caused by the absence of pain or injury in the glenohumeral joint of the participants in the present study, as one of the inclusion criteria was not suffering any pain or injury two weeks prior the testing day. Nevertheless 67.4% of the tennis players in the present study reported having shoulder injury story and 25.5% shoulder pain during practice. Another possible explanation is that 86% of the participant were involved in a shoulder injury prevention program, which could enhance the strength and stability of the shoulder complex and reduce ER asymmetries [

39,

40]

First aim of this study was, add information about IR in the range of movement than often occurs in tennis players, at 45° of glenohumeral abduction and in an active condition. Therefore, we could compare the results of the IR of the dominant and non-dominant shoulders developed at 45° and 90° of abduction and in an active and passive conditions. When comparing the results of passive condition developed at 90° we can see that the values for IR of the present study are higher than previous studies [

32]. A possible explanation for these results is the fact that we did not use the goniometer and there was the possibility to push the glenohumeral harder than other researchers who need to move the goniometer arms while the participants were moving the forearm, causing a limitation in the range of movement. In the present study we added and extra 10° in comparison with previous studies [

32]by bringing the glenohumeral joint to the maximal passive internal or external position without causing any pain. Other possible explanation is that in previous similar studies, subjects had shoulder pain or reported to have an injury when they were assessed, and these could cause IR restrictions [

31,

32]. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, there’s no previous studies to compare the 45°rotational ranges of movement developed in tennis players.

There were significant differences between the IR developed at 45° or at 90°. Our results showed IR values at 45° of abduction are lower than at 90°. This difference can be attributed to several biomechanical factors. In the 45° position, the posterior shoulder capsule, as well as the posterior deltoid, are in a less restrictive position. This allows the posterior rotator cuff to be more stretched, which may limit the ability to internally rotate [

7,

24]. In contrast, at 90° of abduction, the tension on these structures’ decreases, which may facilitate greater internal rotation due to better alignment and less restriction in movement[

31,

32,

41]. In addition, the 90° abduction position can optimize shoulder biomechanics, allowing for greater activation of internal rotator muscles, such as the subscapularis, which contributes to an increase in IR values[

16,

41]. Therefore, it is critical to consider shoulder position when assessing internal rotation, as this can have significant implications in the rehabilitation and training of athletes.

There were no significant differences when the internal rotation was evaluated actively at 90° and 45°. A possible reason could be that when the assessment was done actively, the tennis players compensated the range of movement with the internal rotation musculature, which use to be well strengthened in professional tennis players, and the force of gravity. Moreover, when we assessed internal rotation passively the shoulder forward thrust was blocked, and in the seated active assessment this lock was not possible.

When comparing the differences in the TROM of the glenohumeral joint at 90° and 45° of abduction, we found significant differences. These variations can be attributed to several biomechanical and physiological factors affecting joint mechanics. First, the position of the arm influences the tension and length of the muscles and ligamentous structures surrounding the glenohumeral joint. At 90°, muscles such as the supraspinatus and infraspinatus are in a different position of contraction and stretch compared to 45°, which can alter the TROM [

6,

41,

42]. Furthermore, at 90° the effect of gravity is greater, which may restrict passive movement due to a greater load on the stabilizing structures [

6,

43]. At 45°, the articular surfaces may align more favorably, allowing for a greater passive range of motion. This variation in congruency can result in differences in the distribution of forces within the joint, directly affecting the range of motion of the glenohumeral joint [

24,

43].

Identifying these differences in passive TROM between 90° and 45° is crucial in clinical assessment and rehabilitation. A thorough understanding of how these positions affect shoulder mobility will allow clinicians to develop more accurate and personalized assessment protocols for recovery from shoulder injuries because this means that passively measuring the ROM of the Glenohumeral at 90° will give very different data to those that can be developed at 45°. However, it seems that when the amplitude is actively performed, there are no significant differences or important effect measurements in both the dominant and the non-dominant at 90° and 45°.

The asymmetric rotational ROM have been considered a specific adaptation in tennis players caused by the high repetitive loading forces generated by strokes, mainly the serve and groundstrokes. Each sport technique involves different joint amplitudes and different angles of work of the muscles around the joint. When a joint changes its physiological neutral position, the efficiency of all the muscles that pass through it changes, the working angle changes the torque and, with it, the efficiency of the muscles passing through the joint [

1,

24].

There were significant differences in external rotation at 90° and 45° considering the dominant and non-dominant side. Assessment of the ER at 90° and 45° showed significant differences between the dominant and non-dominant sides in both active and passive conditions. We found lower ER at 45° for both active and passive conditions. It is important to notice that in active actions at 45°, the supraspinatus is totally activated to develop the first 30° of an abduction, and the posterior deltoid started to contract to perform the rest the abduction until 45°, when it starts its participation in the ER movement of the humerus. Therefore, these statistically significant influence can be explained for the position of the arm, because there is an influence of the available motion of the glenohumeral joint. At 90°, the external rotator muscles, such as the infraspinatus and teres minor, are more active and stiffer. This may restrict ER compared to the position at 45°, where the muscle mechanics allow greater freedom of movement [

32,

41,

44]. In addition, at 90°, scapular stabilisation plays a crucial role; any dysfunction in this area can result in a significant decrease in range of motion [

41]. Thus, we must consider both active and passive conditions to obtain a complete evaluation of tennis players. Additionally, we considered important knowing the ER in the angle at which most tennis actions are repeated at 45°, as glenohumeral ER restrictions at 45° generate biomechanical problems around the waist that, if not detected at time, can cause future GIRD and/or symptomatic injuries to tennis players [

31,

34,

44].

The results showed that in asymptomatic tennis players, an increased workload and stiffness of the internal rotators of the glenohumeral joint resulted in a restriction of the ER. The anterior muscles stiffness pulls the major tubercle of the humerus to IR and, therefore the humeral head have a posterior displacement, the opposite as the biomechanical throwing technique reported for the pitchers [

12,

15,

18,

28]. This change in the neutral position of the humeral head reduce the torque of the posterior rotator cuff, increasing the work that they must do to externally rotate the humerus during the glenohumeral abduction. Thus, the external rotation produced is not enough to avoid the collision between the major tubercle of the humerus and the acromion and the impingement of the subacromial space is repeated in every overhead action of these athletes, and with it all the pathology that the repetitive impingement can develop [

45,

46]. For this reason, it will be so important to take GERD into account in the evaluation of tennis players.

The variation in passive mobility between 90° and 45° angles can be explained through the concept of muscle tension and joint coaptation. At 45°, the alignment of joint structures may be more favourable, allowing a greater range of motion without the restrictions imposed by muscle tension [

6,

23,

26,

44]. This suggests that measurements in different positions may provide complementary information on joint health and muscle function.

Depending on whether the evaluation is done at 90°, 45°, active or passive we can see how this can influence the precision, reproducibility and accuracy of the measurement, but may not be related to glenohumeral motion. It is inappropriate to assume that all these variables are the same on both sides, since the motion of the elbow, scapular, pronation and supination scapular are manifestly different on the dominant and non-dominant sides [

41]. Previous study assessed passive glenohumeral IR and ER in a seated position on elite tennis players and found decreased dominant IR and increased dominant ER [

44]. These results were like studies that have assessed passive glenohumeral ROM in a supine position [

32,

41,

42]. Nevertheless, there still a lack of studies that compare a different angles and conditions for evaluating the glenohumeral ROM in tennis players.

Absolute IR degrees, at 45° and 90° of abduction were lower on the dominant side than on the non-dominant side in both active and passive conditions. However, active and passive ER at 45° and 90° were grater on the non-dominant side than on the dominant side. Our results are mostly in line with previous research except for the greater ER in the non-dominant side [

10,

22,

31,

32,

34,

41]. This discrepancy could be associated with the fact than most of the previous studies in tennis players were developed in injured or painful shoulders, and in the present study the participants state being free of shoulder pain. As is well knowns that in a painful tennis shoulder the increase in the ER on the dominant side is an adaptation to the restrictions in the IR on the painful dominant side [

15,

24,

44] our findings suggest that a detection of a restriction in the non-dominant shoulder could be a sign of a possible biomechanical problem that may tigger future problems in the dominant limb.

The association with GIRD and an increased risk of shoulder injuries in tennis athletes is highly reported. Moreover, an increased side-to-side shoulder IR difference and a decrease in the ER/IR ratio have reported to have significant relationship with the years of tennis practice [

10]. The fundamental reason behind these differences lies in the functional adaptation of the dominant shoulder. Athletes and individuals who perform unilateral movements use to develop greater strength and neuromuscular control in the dominant arm, which can lead to an imbalance in flexibility and range of motion. In this regard, repeated use of the dominant arm in activities requiring strength and precision may result in greater stiffness of muscles and connective tissues compared to the non-dominant side, which may be freer to develop optimal range of motion [

31,

32,

44].

Although previous studies imply a relationship between upper extremity injury and GIRD in overhead athletes, this is the first study to consider GERD as a method for detecting possible GIRD in tennis players.

It has been demonstrated that changes in positioning among measurements can reduce the reliability of these measurements. Normative values should be established with methods that could be used on non-athlete populations. Nevertheless, most normative values have been established for testing positions using non-functional methodologies [

32]. For this reason, we have used the inertial measurement units (IMUs), which have demonstrated to be reliable and valid devices to assess the glenohumeral range of motion into more functional movements. We encourage future researchers to assess the glenohumeral ROM with IMU sensors as these devices enhance the ecological validity of these kind of studies, as the classical goniometer take more time and has demonstrated to be less reliable than these sensors [

47]. Moreover, only one researcher is needed to assess each athlete to obtain the most accurate normative values.

Most of the literature establishing criteria for addressing the painful athletes shoulder comes from biomechanics and pathology of the baseball pitcher [

11,

15,

48]. Nevertheless, the technical requirement and the injury ethology in the pitcher is very different than other overhead athlete as a tennis player. To the best of our knowledge there is a lack of studies about the shoulder injury etiology in the specific technical movements in tennis. For this reason, this study could be useful for take a specific normative value in tennis players at 45° of abduction.

Most of the previous studies considered the GIRD as an index for injury prevention, but there’s still a lack of knowledge about normative values for GERD. In tennis players, before we are able to observe a GIRD, there is a decrease in glenohumeral external rotation, caused by the higher load on internal rotation muscles across practice, the strength and conditioning sessions and matches [

1,

13].The current GIRD paradigm has been defined on pitchers and is based on a retraction of the posterior capsule and anteriorization of the humeral head [

48]. However, the paradigm on the etiology of GIRD doesn’t consider that an increased work of the internal rotator muscles causes its stiffness. Therefore, this stiffness will trigger a restriction of ER range of movement. When the GERD is maintained during days, the anterior muscles of the shoulder complex will get shortened, and this will bring the humerus to a position of internal rotation, causing a displacement of the humeral head to posterior, not anterior as is described on the pitchers. The displacement of the humerus to IR will reduce the attachment angle of the posterior rotator cuff, reducing its torque to produce glenohumeral external rotation and, thus reducing the efficiency of the posterior rotator cuff. Suddenly the posterior rotator cuff will have to develop more displacement of the humeral head to escape from the subacromial impingement. The increment of the displacement produces an increased work, fatigue and tightness of these muscles. Thus, when this situation stays over the time, it will be a biofeedback that will trigger the posterior rotation cuff atrophy, weakness and shortness and, finally we will observe an IR restriction [

27].

Most of the previous studies about glenohumeral rotational ROM are focused on passive conditions and used a gyroscope or the goniometer [

1,

8,

15,

24,

25]. Nevertheless, all tennis strokes are performed quickly and in active conditions. For this reason, we assessed the glenohumeral rotation in an active condition and used another method to evaluation, avoiding the problems reported in previous studies when a single researcher perform the measurements with a goniometer or when there are needed two observers to assess one shoulder [

1,

12,

13,

25]. The use of the IMUs allow to develop the assessed range of movement without a restriction on the assessment position, condition neither the velocity of the observed movement. Nevertheless, further research is needed to assess the glenohumeral rotational motion at different angular velocities.

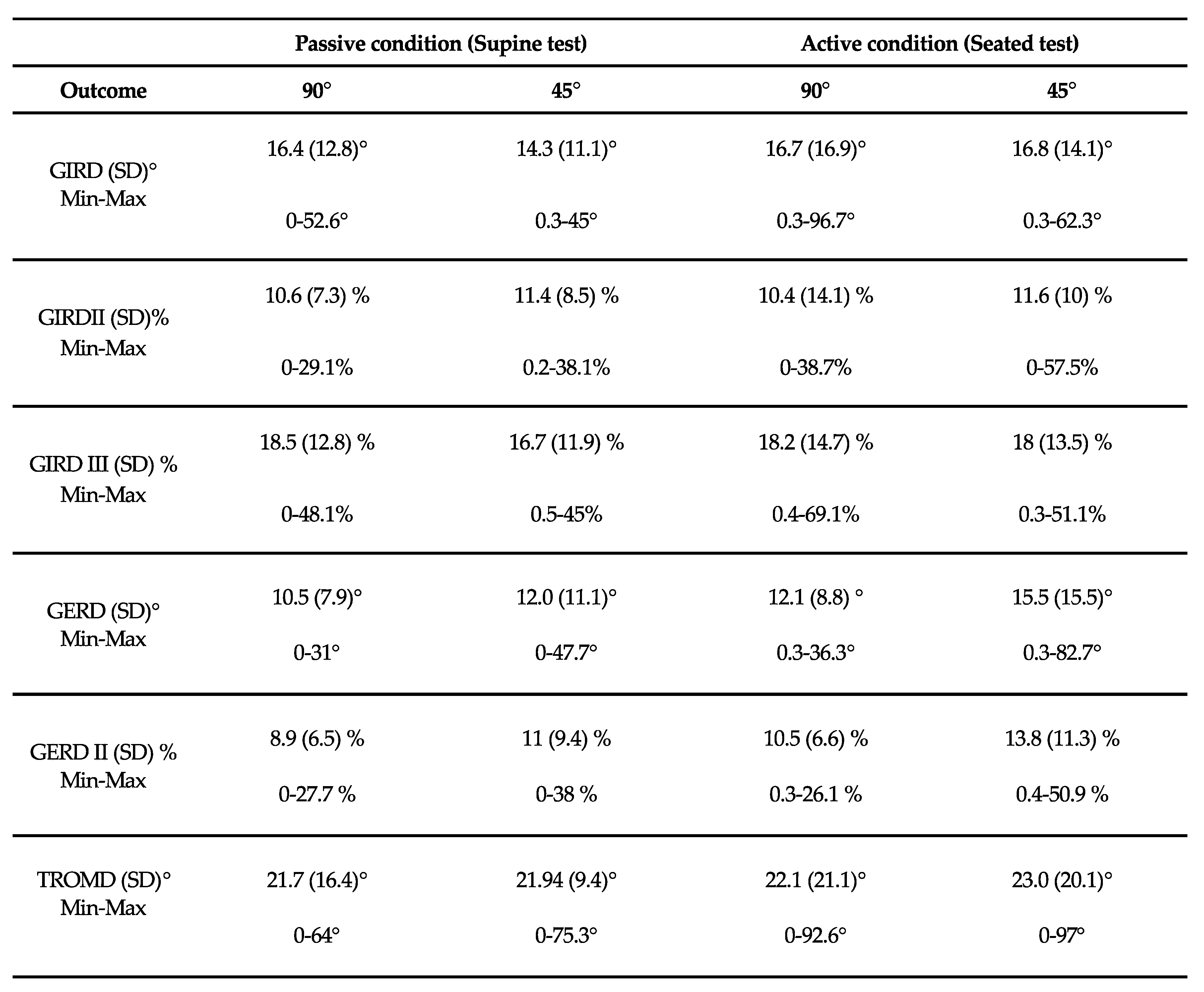

Other important contribution of the present study is considering the GIRD and the GERD as a percentage of deficit between dominant and non-dominant IR, ER and TROM. The results showed that pathological GIRD Type II (a percentage of difference between dominant and non-dominant side >10% of the TROM) while classical GIRD had mean values of 16.4±12.8° at 90° of abduction and for 14.3±11.1° at 45° for passive conditions and 16.7±16.9° at 90° of abduction and for 16.8±14.1° at 45° for active condition (

Table 4). Additionally, all TROMD are greater than the 5° of difference than previous research considers as a risk factor for shoulder injury[

13,

17,

35].

For the time being, the normative reference values provided in the present study may be useful for interpreting GIRD and GERD at 45° and 90° of abduction for active and passive conditions. However, further research is needed to provide more data on specific glenohumeral rotation deficits at 45° and 90° in both active and passive conditions and in different angular velocities. It is essential to know the technique of the athlete we want to analyze, since each sports technique involves different joint amplitudes and different work angles of the muscles that surround the athlete’s joints. Furthermore, in the same sport there may be different styles that completely change the biomechanics of the sporting gesture and, consequently, the angle at which the muscles work and the effort that these muscles are making or how they will adapt to that effort. Normative values of shoulder rotation at 90° and 45° of abduction and active and passive condition could be used in clinical and research settings to contextualize individual test values in comparison to age-matched peers.