Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Animals

Brain Slice Preparation

Electrophysiological Recordings

5-HT Uncaging

Immunohistochemistry

Image Acquisition

Calculations and Analyses

Results

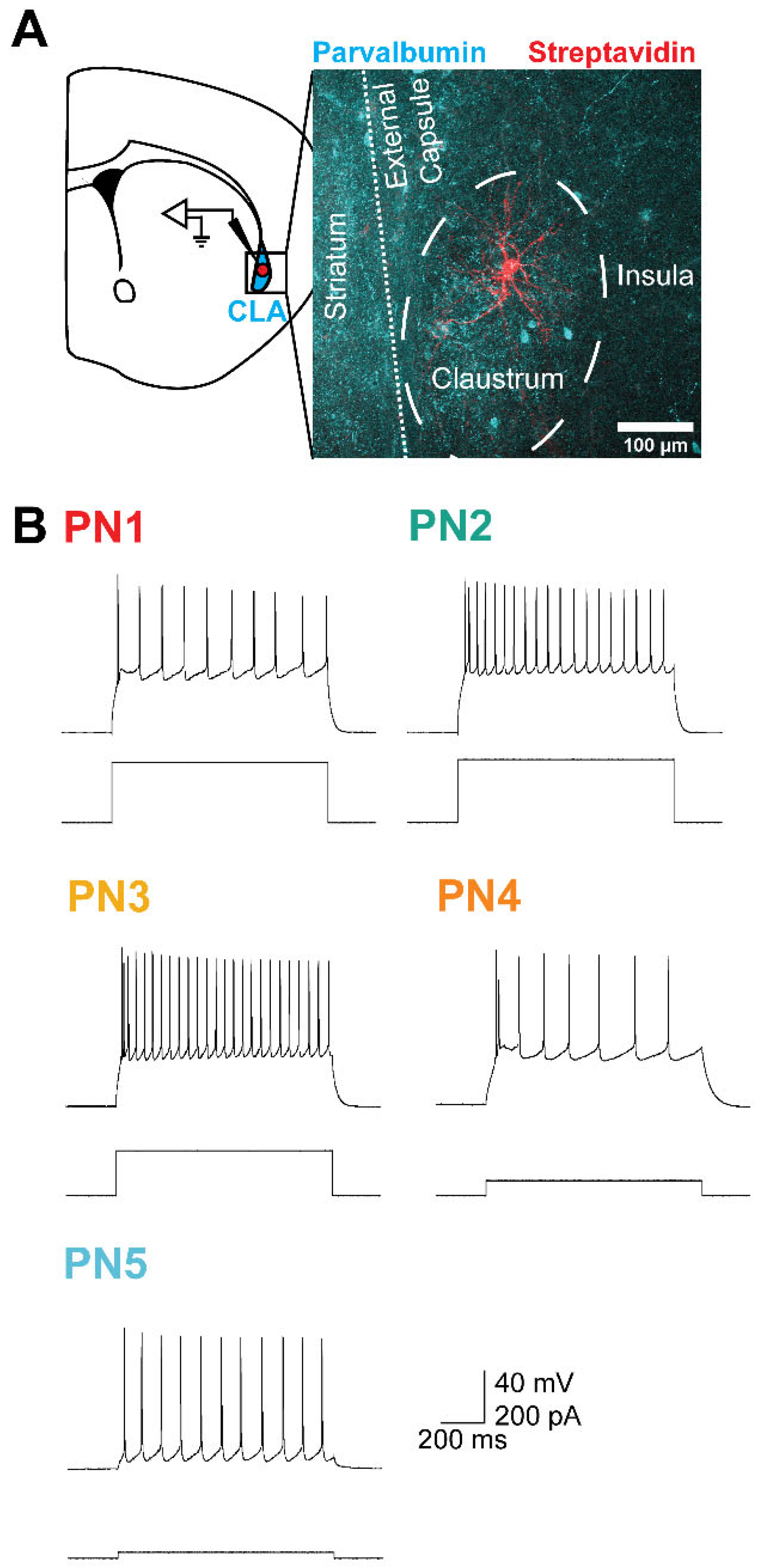

Identification of Claustral PNs

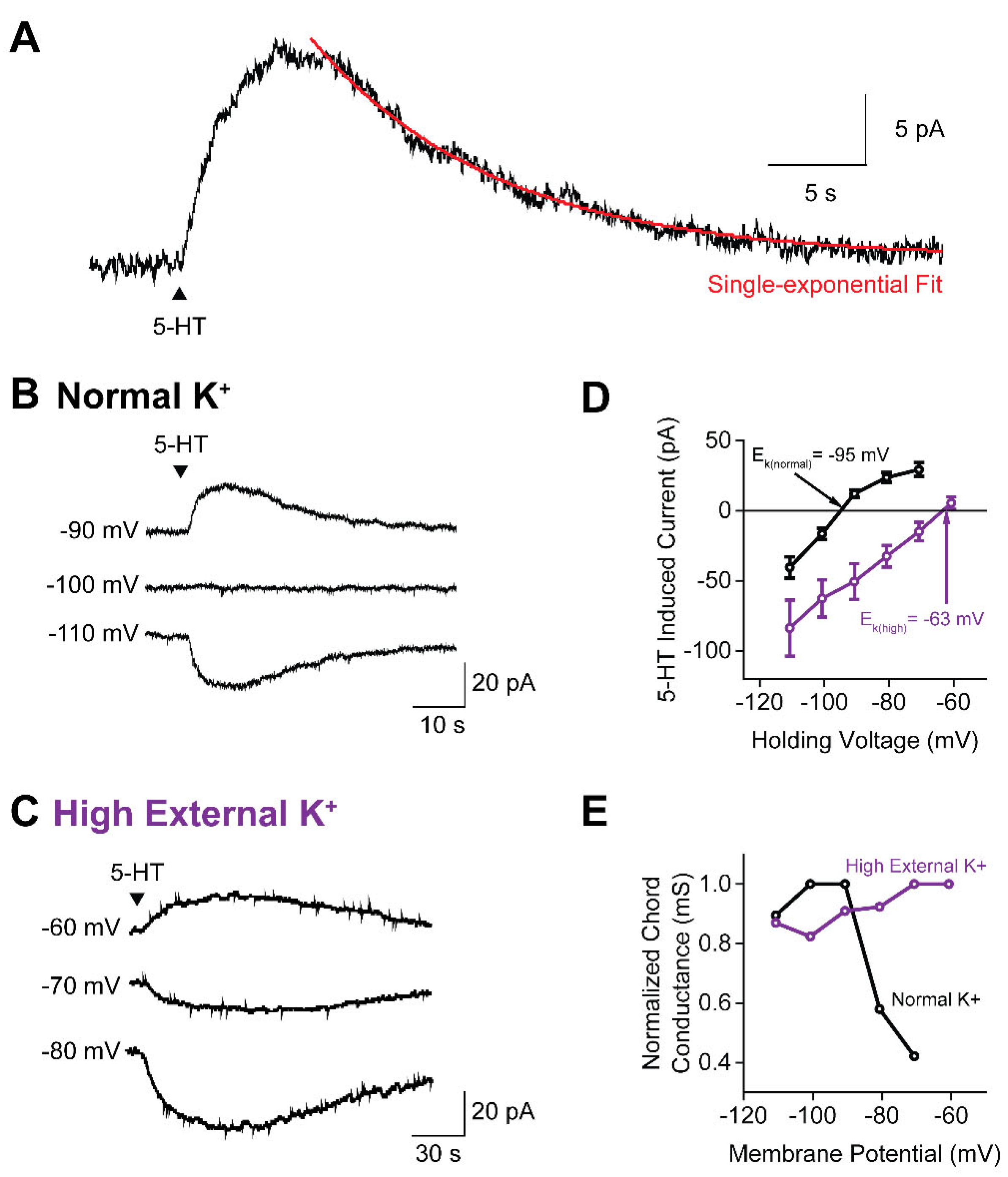

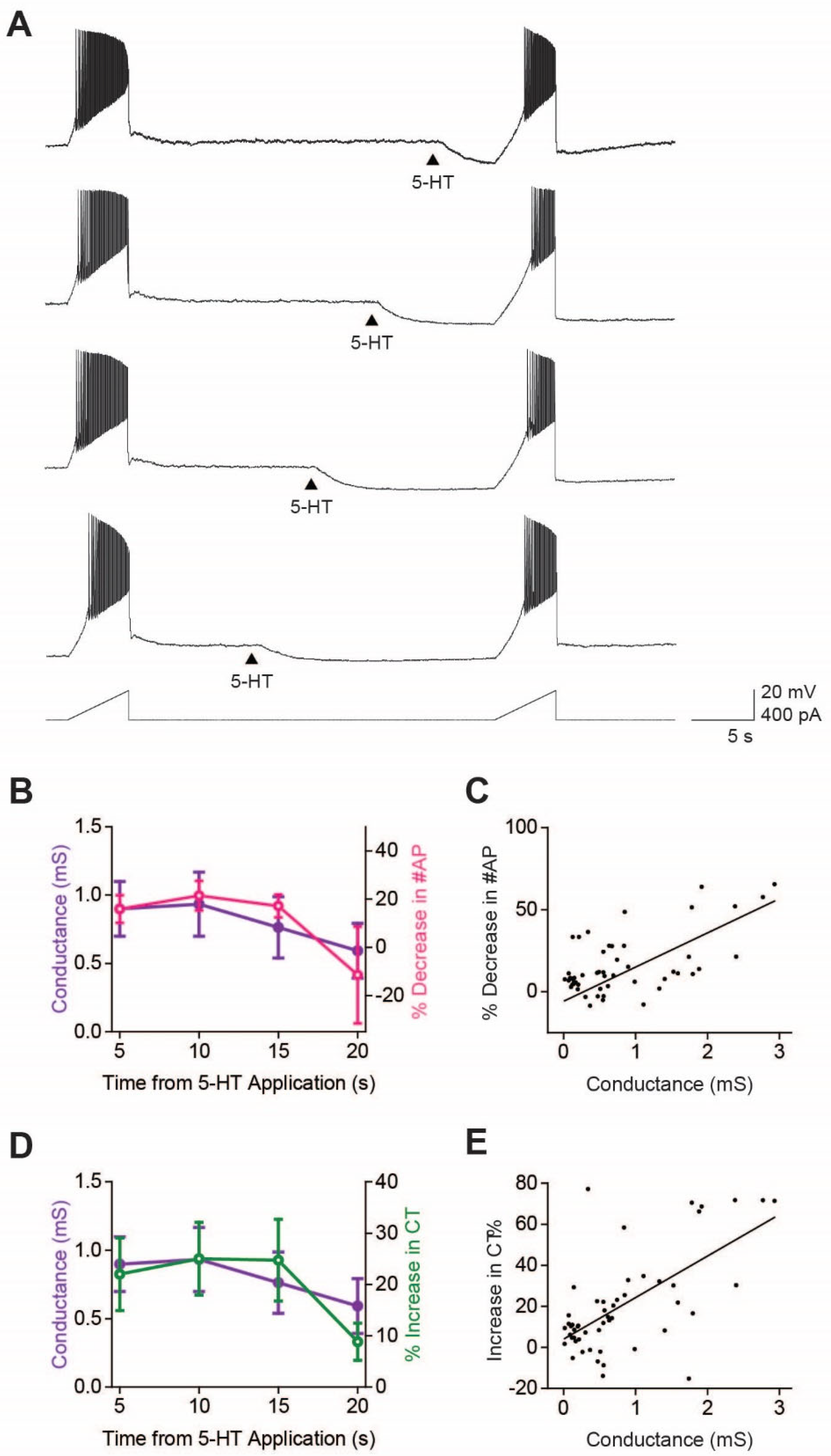

Claustral PNs Are Inhibited by a K+ Conductance Increase

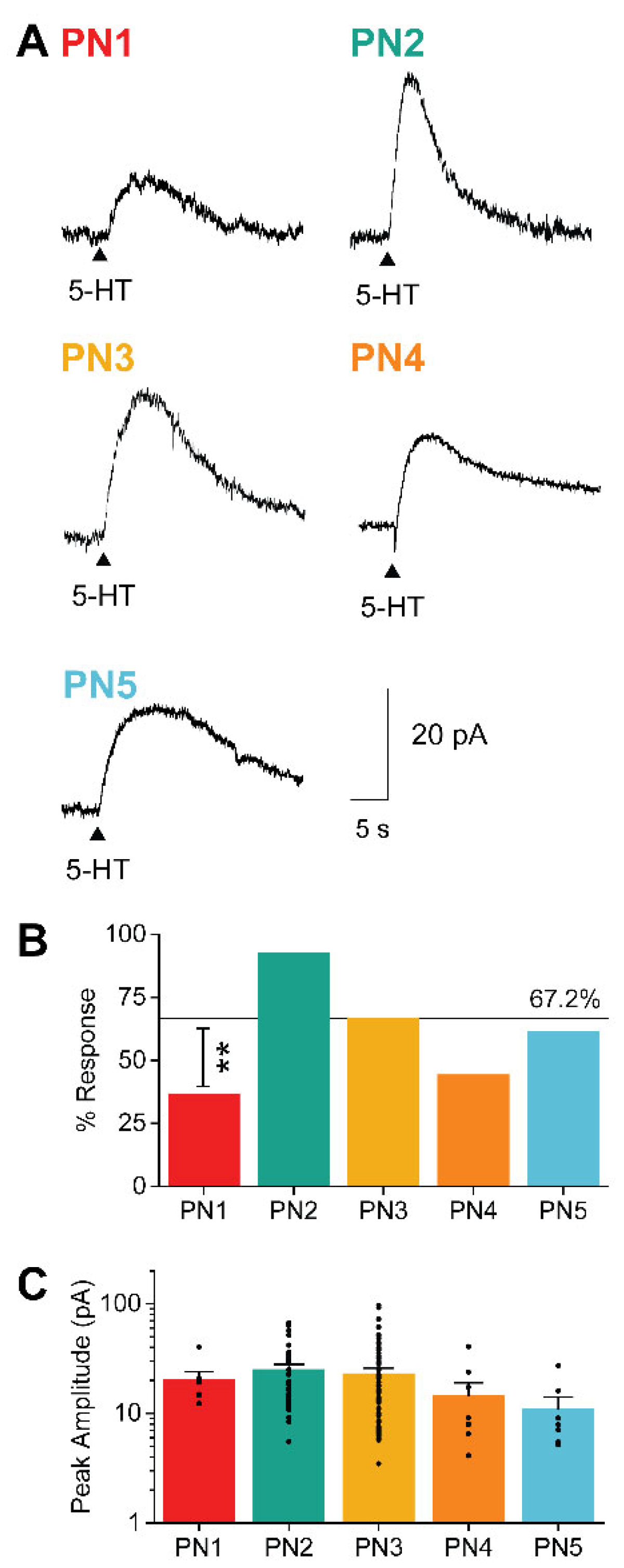

Claustral PN Subtypes Differ in Probability of 5-HT Responses

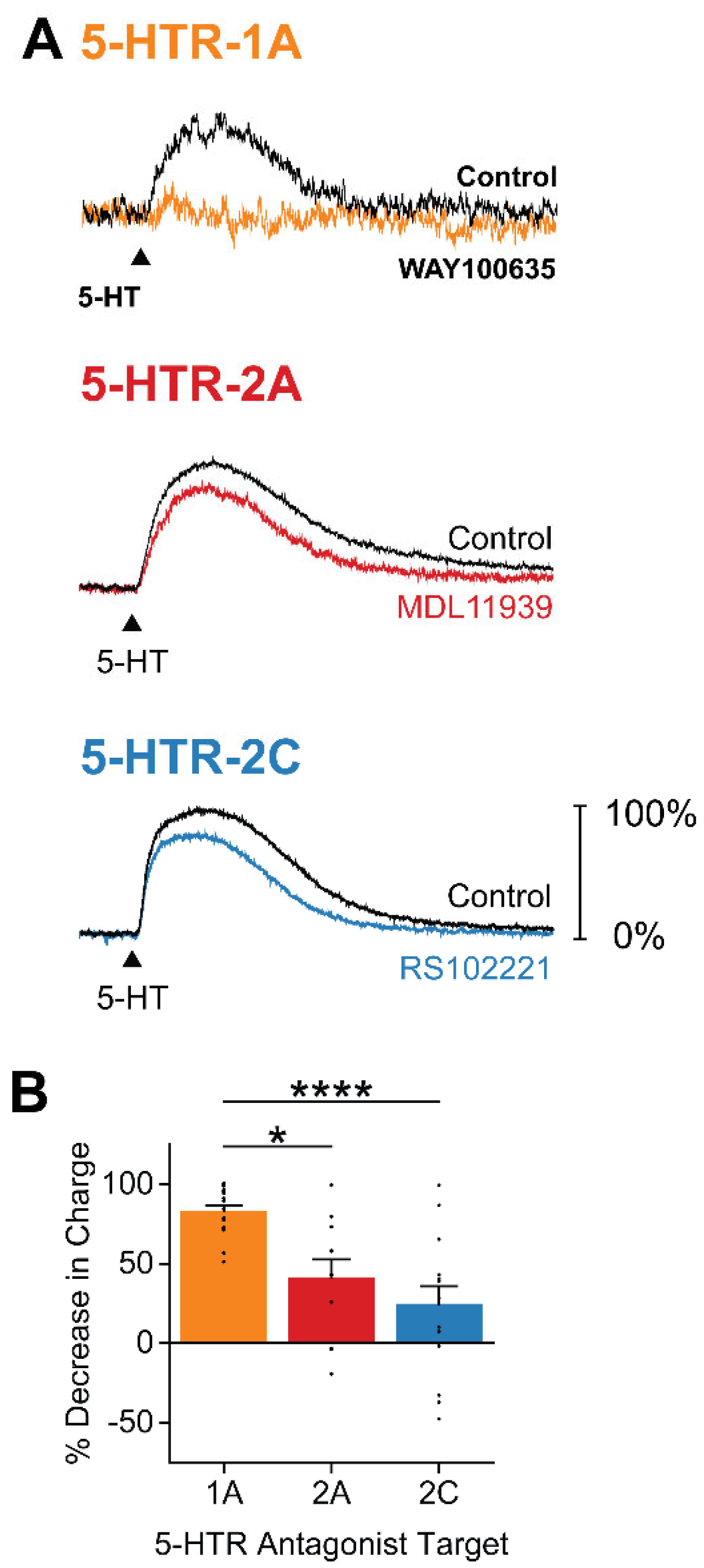

5-HT Responses Are Generated by Multiple Types of 5-HTRs

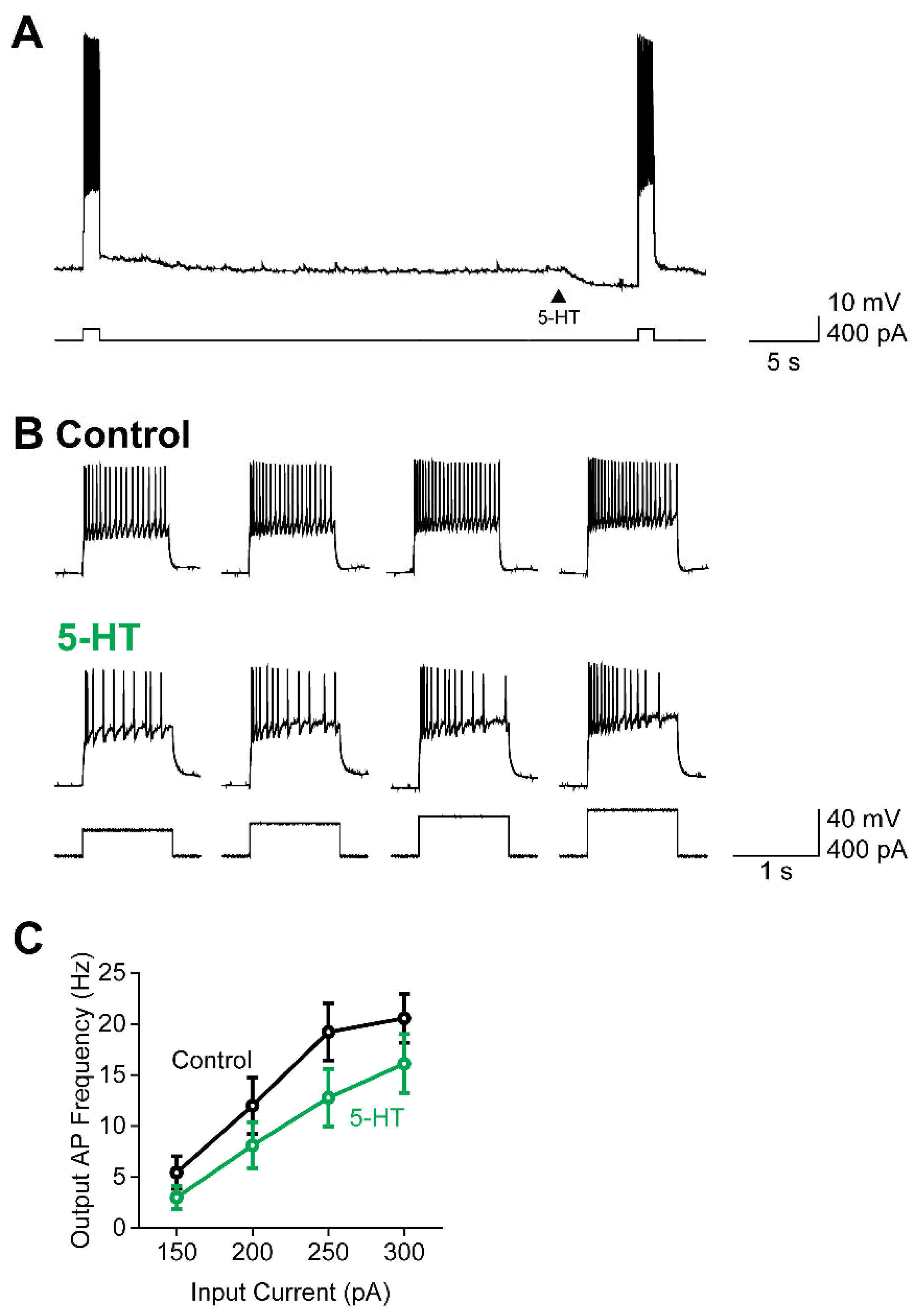

Actions of 5-HT on AP Firing

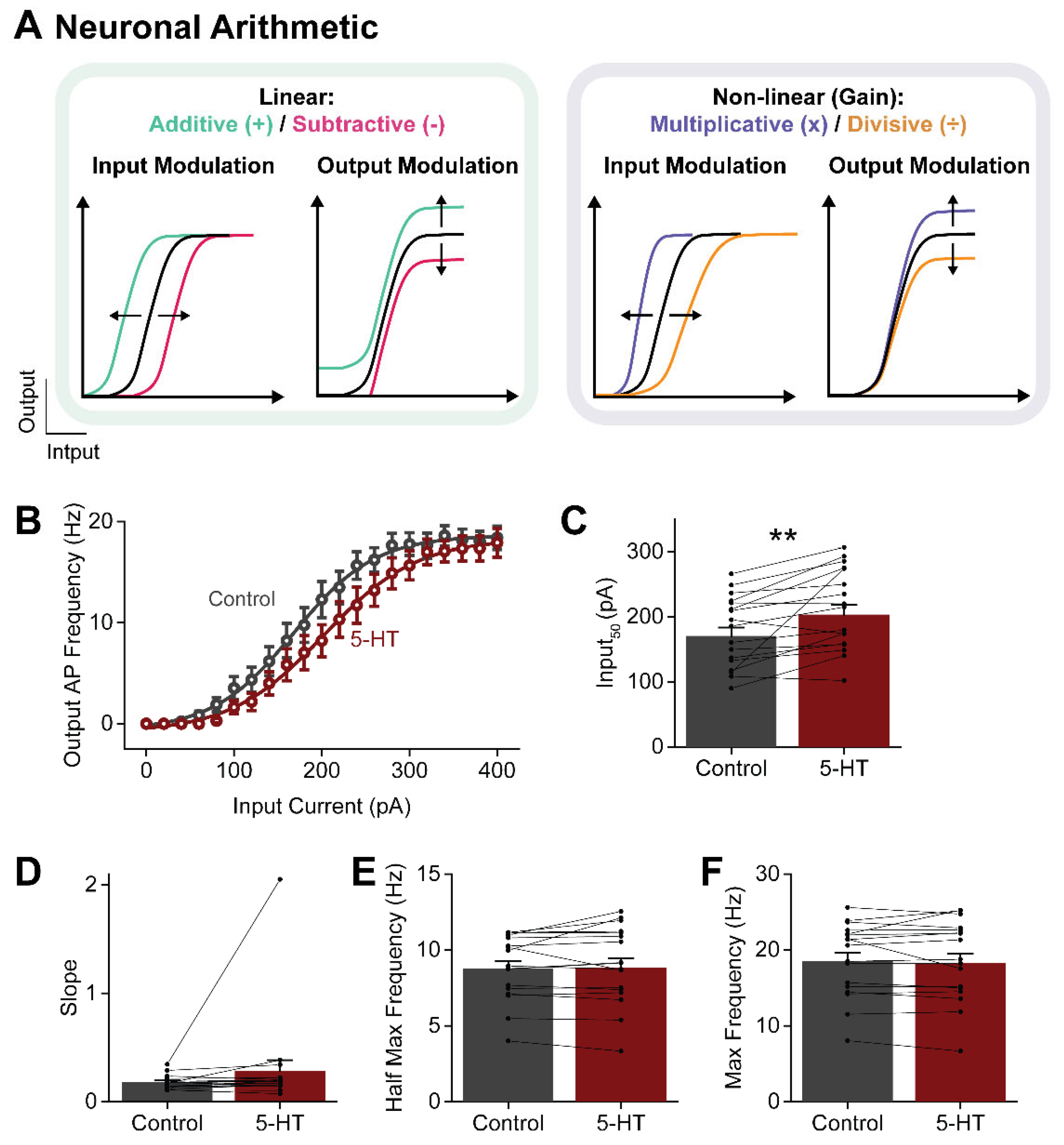

5-HT Causes a Subtractive Reduction in PN Output

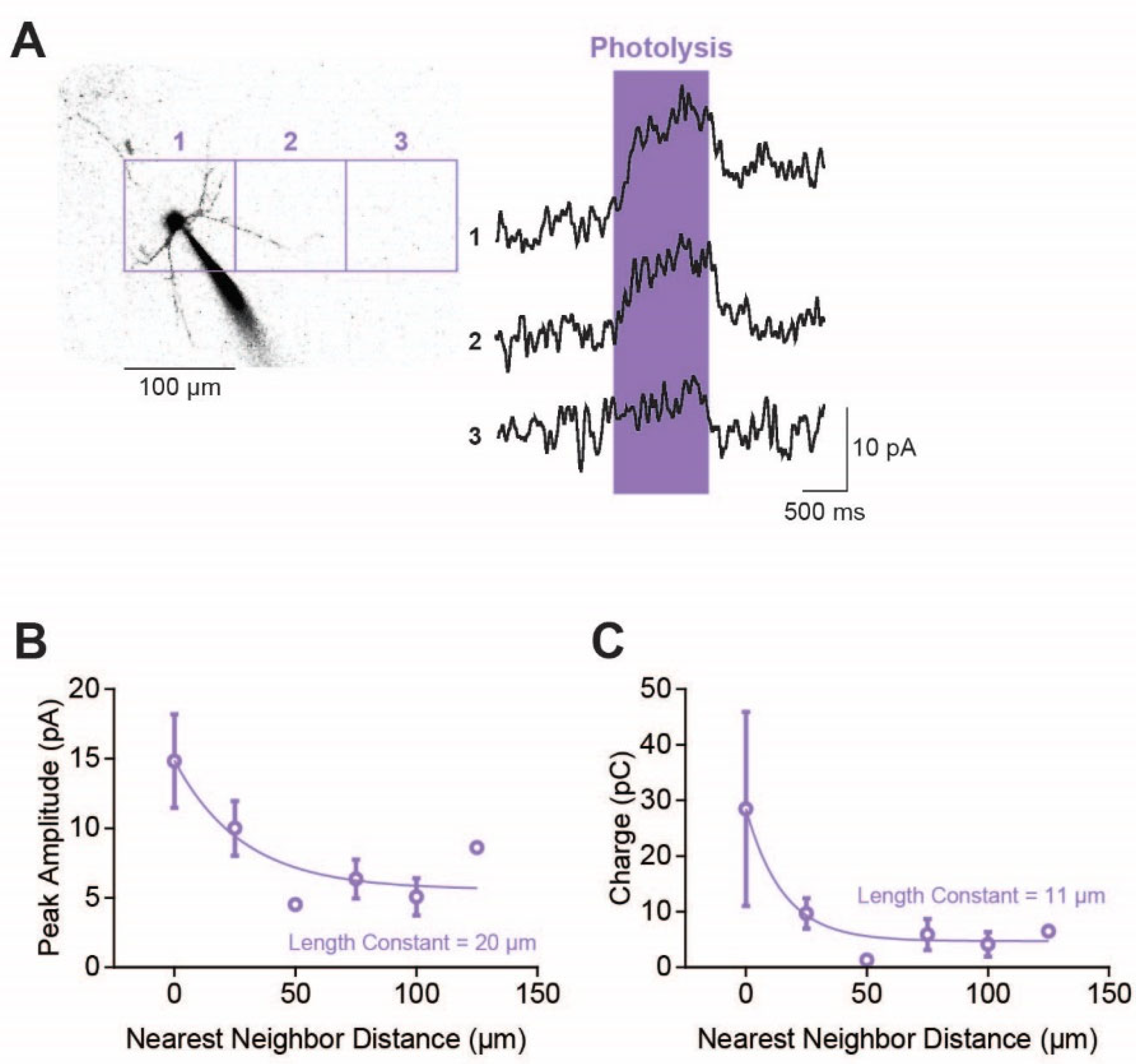

5-HTRs Are Distributed Throughout Claustral PN Compartments

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

References

- Torgerson, C.M., Irimia, A., Goh, S.Y.M., and Van Horn, J.D. (2015). The DTI connectivity of the human claustrum. Hum. Brain Mapp. 36, 827-838. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Ng, L., Harris, J.A., Feng, D., Li, Y., Royall, J.J., Oh, S.W., Bernard, A., Sunkin, S.M., Koch, C., and Zeng, H. (2017). Organization of the connections between claustrum and cortex in the mouse. The Journal of comparative neurology 525, 1317-1346. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Xie, P., Gong, H., Zhou, Z., Kuang, X., Wang, Y., Li, A.-a., Li, Y., Liu, L., Veldman, M.B., et al. (2019). Complete single neuron reconstruction reveals morphological diversity in molecularly defined claustral and cortical neuron types. bioRxiv, 675280. [CrossRef]

- Zingg, B., Dong, H.-W., Tao, H.W., and Zhang, L.I. (2018). Input–output organization of the mouse claustrum. The Journal of comparative neurology 526, 2428-2443. [CrossRef]

- Sherk, H. (1986). The claustrum and the cerebral cortex. In Sensory-motor areas and aspects of cortical connectivity, E.G. Jones, and A. Peters, eds. (Springer), pp. 467-499. [CrossRef]

- Atlan, G., Terem, A., Peretz-Rivlin, N., Groysman, M., and Citri, A. (2017). Mapping synaptic cortico-claustral connectivity in the mouse. The Journal of comparative neurology 525, 1381-1402. [CrossRef]

- Crick, F.C., and Koch, C. (2005). What is the function of the claustrum? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 360, 1271-1279. [CrossRef]

- Atilgan, H., Doody, M., Oliver, D.K., McGrath, T.M., Shelton, A.M., Echeverria-Altuna, I., Tracey, I., Vyazovskiy, V.V., Manohar, S.G., and Packer, A.M. (2022). Human lesions and animal studies link the claustrum to perception, salience, sleep and pain. Brain 145, 1610-1623. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J., Smith, J.B., and Lee, A.K. (2020). The Anatomy and Physiology of Claustrum-Cortex Interactions. Annu Rev Neurosci 43, 231-247. [CrossRef]

- Madden, M.B., Stewart, B.W., White, M.G., Krimmel, S.R., Qadir, H., Barrett, F.S., Seminowicz, D.A., and Mathur, B.N. (2022). A role for the claustrum in cognitive control. Trends Cogn Sci 26, 1133-1152. [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.L.L., Nair, A., and Augustine, G.J. (2021). Changing the Cortical Conductor's Tempo: Neuromodulation of the Claustrum. Front Neural Circuits 15, 658228.

- Jouvet, M. (1999). Sleep and serotonin: an unfinished story. Neuropsychopharmacology 21, 24-27. [CrossRef]

- Monti, J.M. (2010). The role of dorsal raphe nucleus serotonergic and non-serotonergic neurons, and of their receptors, in regulating waking and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Sleep Med Rev 14, 319-327. [CrossRef]

- Portas, C.M., Bjorvatn, B., and Ursin, R. (2000). Serotonin and the sleep/wake cycle: special emphasis on microdialysis studies. Prog. Neurobiol. 60, 13-35. [CrossRef]

- Atlan, G., Matosevich, N., Peretz-Rivlin, N., Yvgi, I., Chen, E., Kleinman, T., Bleistein, N., Sheinbach, E., Groysman, M., Nir, Y., and Citri, A. (2021). Claustral projections to anterior cingulate cortex modulate engagement with the external world. bioRxiv, 2021.2006.2017.448649. [CrossRef]

- Narikiyo, K., Mizuguchi, R., Ajima, A., Shiozaki, M., Hamanaka, H., Johansen, J.P., Mori, K., and Yoshihara, Y. (2020). The claustrum coordinates cortical slow-wave activity. Nat. Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Norimoto, H., Fenk, L.A., Li, H.H., Tosches, M.A., Gallego-Flores, T., Hain, D., Reiter, S., Kobayashi, R., Macias, A., Arends, A., et al. (2020). A claustrum in reptiles and its role in slow-wave sleep. Nature 578, 413-418. [CrossRef]

- Olaghere Da Silva, U., Morabito, M., Canal, C., Airey, D., Emeson, R., and Sanders-Bush, E. (2010). Impact of RNA editing on functions of the serotonin 2C receptor in vivo. Front. Neurosci. 4.

- Kinsey, A.M., Wainwright, A., Heavens, R., Sirinathsinghji, D.J., and Oliver, K.R. (2001). Distribution of 5-ht(5A), 5-ht(5B), 5-ht(6) and 5-HT(7) receptor mRNAs in the rat brain. Brain research. Molecular brain research 88, 194-198. [CrossRef]

- Mengod, G., Nguyen, H., Le, H., Waeber, C., Lubbert, H., and Palacios, J.M. (1990). The distribution and cellular localization of the serotonin 1C receptor mRNA in the rodent brain examined by in situ hybridization histochemistry. Comparison with receptor binding distribution. Neuroscience 35, 577-591. [CrossRef]

- Pompeiano, M., Palacios, J.M., and Mengod, G. (1994). Distribution of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptor family mRNAs: comparison between 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors. Brain research. Molecular brain research 23, 163-178. [CrossRef]

- Rioux, A., Fabre, V., Lesch, K.P., Moessner, R., Murphy, D.L., Lanfumey, L., Hamon, M., and Martres, M.P. (1999). Adaptive changes of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in mice lacking the serotonin transporter. Neurosci Lett 262, 113-116. [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.P., and Dorsa, D.M. (1996). Colocalization of serotonin receptor subtypes 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT6 with neuropeptides in rat striatum. The Journal of comparative neurology 370, 405-414. [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.E., Seroogy, K.B., Lundgren, K.H., Davis, B.M., and Jennes, L. (1995). Comparative localization of serotonin1A, 1C, and 2 receptor subtype mRNAs in rat brain. The Journal of comparative neurology 351, 357-373. [CrossRef]

- Hamada, S., Senzaki, K., Hamaguchi-Hamada, K., Tabuchi, K., Yamamoto, H., Yamamoto, T., Yoshikawa, S., Okano, H., and Okado, N. (1998). Localization of 5-HT2A receptor in rat cerebral cortex and olfactory system revealed by immunohistochemistry using two antibodies raised in rabbit and chicken. Brain research. Molecular brain research 54, 199-211. [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T., Gehlert, D., McCabe, R., Barnett, A., and Wamsley, J. (1986). D-1 dopamine receptors in the rat brain: a quantitative autoradiographic analysis. J. Neurosci. 6, 2352-2365.

- Gawliński, D., Smaga, I., Zaniewska, M., Gawlińska, K., Faron-Górecka, A., and Filip, M. (2019). Adaptive mechanisms following antidepressant drugs: focus on serotonin 5-HT2A receptors. Pharmacol. Rep. 71, 994-1000. [CrossRef]

- Vertes, R.P. (1991). A PHA-L analysis of ascending projections of the dorsal raphe nucleus in the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology 313, 643-668. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Hannesson, D.K., Saucier, D.M., Wallace, A.E., Howland, J., and Corcoran, M.E. (2001). Susceptibility to kindling and neuronal connections of the anterior claustrum. J. Neurosci. 21, 3674-3687.

- Peyron, C., Petit, J.M., Rampon, C., Jouvet, M., and Luppi, P.H. (1998). Forebrain afferents to the rat dorsal raphe nucleus demonstrated by retrograde and anterograde tracing methods. Neuroscience 82, 443-468. [CrossRef]

- Muzerelle, A., Scotto-Lomassese, S., Bernard, J.F., Soiza-Reilly, M., and Gaspar, P. (2016). Conditional anterograde tracing reveals distinct targeting of individual serotonin cell groups (B5–B9) to the forebrain and brainstem. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 535-561. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.E., and Baizer, J.S. (2007). Neurochemically defined cell types in the claustrum of the cat. Brain Res. 1159, 94-111. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.A., and Nichols, C.D. (2016). Psychedelics recruit multiple cellular types and produce complex transcriptional responses within the brain. EBioMedicine 11, 262-277. [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacol. Rev. 68, 264-355. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, F.S., Krimmel, S.R., Griffiths, R., Seminowicz, D.A., and Mathur, B.N. (2020). Psilocybin acutely alters the functional connectivity of the claustrum with brain networks that support perception, memory, and attention. NeuroImage, 116980. [CrossRef]

- Snider, S.B., Hsu, J., Darby, R.R., Cooke, D., Fischer, D., Cohen, A.L., Grafman, J.H., and Fox, M.D. (2020). Cortical lesions causing loss of consciousness are anticorrelated with the dorsal brainstem. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 1520-1531. [CrossRef]

- Chia, Z., Silberberg, G., and Augustine, G.J. (2017). Functional properties, topological organization and sexual dimorphism of claustrum neurons projecting to anterior cingulate cortex. Claustrum 2, 1357412. [CrossRef]

- Graf, M., Nair, A., Wong, K.L.L., Tang, Y., and Augustine, G.J. (2020). Identification of mouse claustral neuron types based on their intrinsic electrical properties. eNeuro 7, ENEURO.0216-0220.2020.

- Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., Preibisch, S., Rueden, C., Saalfeld, S., Schmid, B., et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676-682. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Arshadi, C., Günther, U., Eddison, M., Harrington, K.I.S., and Ferreira, T.A. (2021). SNT: a unifying toolbox for quantification of neuronal anatomy. Nat. Methods 18, 374-377. [CrossRef]

- Backstrom, J.R., Chang, M.S., Chu, H., Niswender, C.M., and Sanders-Bush, E. (1999). Agonist-directed signaling of serotonin 5-HT2C receptors: differences between serotonin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). Neuropsychopharmacology 21, 77s-81s. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K., Sugino, H., Akazawa, H., Amada, N., Shimada, J., Futamura, T., Yamashita, H., Ito, N., McQuade, R.D., Mørk, A., et al. (2014). Brexpiprazole I: in vitro and in vivo characterization of a novel serotonin-dopamine activity modulator. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 350, 589-604. [CrossRef]

- Sodickson, D.L., and Bean, B.P. (1998). Neurotransmitter activation of inwardly rectifying potassium current in dissociated hippocampal CA3 neurons: Interactions among multiple receptors. J. Neurosci. 18, 8153-8162.

- del Burgo, L.S., Cortes, R., Mengod, G., Zarate, J., Echevarria, E., and Salles, J. (2008). Distribution and neurochemical characterization of neurons expressing GIRK channels in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 510, 581-606. [CrossRef]

- Jaén, C., and Doupnik, C.A. (2005). Neuronal Kir3.1/Kir3.2a channels coupled to serotonin 1A and muscarinic m2 receptors are differentially modulated by the ‘short’ RGS3 isoform. Neuropharmacology 49, 465-476. [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, A., Corradetti, R., and Mlinar, B. (2015). Pharmacological characterization of 5-HT1A autoreceptor-coupled GIRK channels in rat dorsal raphe 5-HT neurons. PLoS One 10, e0140369.

- Ciranna, L. (2006). Serotonin as a modulator of glutamate- and GABA-mediated neurotransmission: implications in physiological functions and in pathology. Curr Neuropharmacol 4, 101-114.

- Nichols, D.E., and Nichols, C.D. (2008). Serotonin receptors. Chemical reviews 108, 1614-1641. [CrossRef]

- Palchaudhuri, M., and Flügge, G. (2005). 5-HT1A receptor expression in pyramidal neurons of cortical and limbic brain regions. Cell Tissue Res. 321, 159-172. [CrossRef]

- Pazos, A., Probst, A., and Palacios, J.M. (1987). Serotonin receptors in the human brain--III. Autoradiographic mapping of serotonin-1 receptors. Neuroscience 21, 97-122. [CrossRef]

- el Mansari, M., and Blier, P. (1997). In vivo electrophysiological characterization of 5-HT receptors in the guinea pig head of caudate nucleus and orbitofrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology 36, 577-588. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L., Sohn, D., Thorberg, S.-O., Jackson, D.M., Kelder, D., Larsson, L.-G., Rényi, L., Ross, S.B., Wallsten, C., Eriksson, H., et al. (1997). The pharmacological characterization of a novel selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor antagonist, NAD-299. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283, 216-225.

- Tang, Z.-Q., and Trussell, L.O. (2015). Serotonergic regulation of excitability of principal cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J. Neurosci. 35, 4540-4551.

- Zhang, Z. (2003). Serotonin induces tonic firing in layer V pyramidal neurons of rat prefrontal cortex during postnatal development. J. Neurosci. 23, 3373-3384.

- Austgen, J.R., Dantzler, H.A., Barger, B.K., and Kline, D.D. (2012). 5-Hydroxytryptamine 2C receptors tonically augment synaptic currents in the nucleus tractus solitarii. J Physiol 108, 2292-2305. [CrossRef]

- Bocchio, M., Fucsina, G., Oikonomidis, L., McHugh, S.B., Bannerman, D.M., Sharp, T., and Capogna, M. (2015). Increased serotonin transporter expression reduces fear and recruitment of parvalbumin interneurons of the amygdala. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 3015-3026. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-C., Liang, Y.-C., Lee, C.-C., Wu, M.-Y., and Hsu, K.-S. (2009). Repeated cocaine administration decreases 5-HT2A receptor-mediated serotonergic enhancement of synaptic activity in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 1979-1992. [CrossRef]

- Aloyo, V.J., and Harvey, J.A. (2000). Antagonist binding at 5-HT(2A) and 5-HT(2C) receptors in the rabbit: high correlation with the profile for the human receptors. European journal of pharmacology 406, 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Knight, A.R., Misra, A., Quirk, K., Benwell, K., Revell, D., Kennett, G., and Bickerdike, M. (2004). Pharmacological characterisation of the agonist radioligand binding site of 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 370, 114-123. [CrossRef]

- Pehek, E.A., Nocjar, C., Roth, B.L., Byrd, T.A., and Mabrouk, O.S. (2006). Evidence for the Preferential Involvement of 5-HT2A Serotonin Receptors in Stress- and Drug-Induced Dopamine Release in the Rat Medial Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 265-277. [CrossRef]

- Nair, A., Teo, Y.Y., Augustine, G.J., and Graf, M. (2023). A functional logic for neurotransmitter corelease in the cholinergic forebrain pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 120, e2218830120. [CrossRef]

- White, M.G., and Mathur, B.N. (2018). Claustrum circuit components for top-down input processing and cortical broadcast. Brain Struct. Funct. 223, 3945-3958. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, K.A., and Cardin, J.A. (2020). Mechanisms underlying gain modulation in the cortex. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 21, 80-92. [CrossRef]

- Silver, R.A. (2010). Neuronal arithmetic. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 11, 474-489. [CrossRef]

- Celada, P., Puig, M.V., and Artigas, F. (2013). Serotonin modulation of cortical neurons and networks. Front. Integr. Neurosc. 7.

- Savalia, N.K., Shao, L.-X., and Kwan, A.C. (2021). A dendrite-focused framework for understanding the actions of ketamine and psychedelics. Trends Neurosci. 44, 260-275. [CrossRef]

- Ellis-Davies, G.C.R. (2019). Two-photon uncaging of glutamate. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 10.

- Pettit, D.L., Wang, S.S., Gee, K.R., and Augustine, G.J. (1997). Chemical two-photon uncaging: a novel approach to mapping glutamate receptors. Neuron 19, 465-471. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.S., and Augustine, G.J. (1995). Confocal imaging and local photolysis of caged compounds: dual probes of synaptic function. Neuron 15, 755-760. [CrossRef]

- Kasai, H., Ucar, H., Morimoto, Y., Eto, F., and Okazaki, H. (2023). Mechanical transmission at spine synapses: Short-term potentiation and working memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol 80, 102706. [CrossRef]

- Rea, A.C., Vandenberg, L.N., Ball, R.E., Snouffer, A.A., Hudson, A.G., Zhu, Y., McLain, D.E., Johnston, L.L., Lauderdale, J.D., Levin, M., and Dore, T.M. (2013). Light-activated serotonin for exploring its action in biological systems. Chemistry & biology 20, 1536-1546. [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N., Blackiston, D.J., Rea, A.C., Dore, T.M., and Levin, M. (2014). Left-right patterning in Xenopus conjoined twin embryos requires serotonin signaling and gap junctions. The International journal of developmental biology 58, 799-809.

- Escobar, C., and Salas, M. (1995). Dendritic branching of claustral neurons in neonatally undernourished rats. Biology of the neonate 68, 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Spauschus, A., Lentes, K., Wischmeyer, E., Dissmann, E., Karschin, C., and Karschin, A. (1996). A G-protein-activated inwardly rectifying K+ channel (GIRK4) from human hippocampus associates with other GIRK channels. J Neurosci 16, 930-938.

- Wickman, K., Karschin, C., Karschin, A., Picciotto, M.R., and Clapham, D.E. (2000). Brain localization and behavioral impact of the G-protein-gated K+ channel subunit GIRK4. J Neurosci 20, 5608-5615.

- Erwin, S.R., Bristow, B.N., Sullivan, K.E., Kendrick, R.M., Marriott, B., Wang, L., Clements, J., Lemire, A.L., Jackson, J., and Cembrowski, M.S. (2021). Spatially patterned excitatory neuron subtypes and projections of the claustrum. eLife 10, e68967.

- Peroutka, S.J. (1995). 5-HT receptors: past, present and future. Trends in Neurosci. 18, 68-69. [CrossRef]

- Araneda, R., and Andrade, R. (1991). 5-Hydroxytryptamine2 and 5-hydroxytryptamine1A receptors mediate opposing responses on membrane excitability in rat association cortex. Neuroscience 40, 399-412. [CrossRef]

- Puig, M.V., and Gulledge, A.T. (2011). Serotonin and prefrontal cortex function: neurons, networks, and circuits. Mol Neurobiol 44, 449-464. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Wang, X., Liu, P., Jing, S., Du, H., Zhang, L., Jia, F., and Li, A. (2020). Serotonergic afferents from the dorsal raphe decrease the excitability of pyramidal neurons in the anterior piriform cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117, 3239-3247. [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.K., Schmidt, E.F., and Lambe, E.K. (2016). Serotonergic suppression of mouse prefrontal circuits implicated in task attention. eNeuro 3, ENEURO.0269-0216.2016.

- Okada, M., Goldman, D., LINNOILA, M., Iwata, N., Ozaki, N., and Northup, J.K. (2004). Comparison of G-Protein selectivity of human 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A receptors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1025, 570-577. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, J.R., Mukhin, Y.V., Gelasco, A., Turner, J., Collinsworth, G., Gettys, T.W., Grewal, J.S., and Garnovskaya, M.N. (2001). Multiplicity of mechanisms of serotonin receptor signal transduction. Pharmacology & therapeutics 92, 179-212. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, M.V., Dunlap, L.E., Dong, C., Carter, S.J., Tombari, R.J., Jami, S.A., Cameron, L.P., Patel, S.D., Hennessey, J.J., Saeger, H.N., et al. (2023). Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity through the activation of intracellular 5-HT2A receptors. Science 379, 700-706. [CrossRef]

- Burns, C.M., Chu, H., Rueter, S.M., Hutchinson, L.K., Canton, H., Sanders-Bush, E., and Emeson, R.B. (1997). Regulation of serotonin-2C receptor G-protein coupling by RNA editing. Nature 387, 303-308. [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L.W., Iyer, G., Conklin, D.S., Krause, C.M., Marshall, A., Patterson, J.P., Tran, D.P., Jonak, G.J., and Hartig, P.R. (1999). Messenger RNA Editing of the Human Serotonin 5-HT2C Receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology 21, 82-90. [CrossRef]

- Maroteaux, L., Béchade, C., and Roumier, A. (2019). Dimers of serotonin receptors: Impact on ligand affinity and signaling. Biochimie 161, 23-33. [CrossRef]

- Bijak, M., and Misgeld, U. (1997). Effects of serotonin through serotonin1A and serotonin4 receptors on inhibition in the guinea-pig dentate gyrus in vitro. Neuroscience 78, 1017-1026. [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.F., Deisz, R.A., Prince, D.A., and Peroutka, S.J. (1987). Two distinct effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine on single cortical neurons. Brain Res. 423, 347-352. [CrossRef]

- Perrier, J.-F., Alaburda, A., and Hounsgaard, J. (2003). 5-HT1A receptors increase excitability of spinal motoneurons by inhibiting a TASK-1-like K+ current in the adult turtle. J Physiol 548, 485-492. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, Z., Barzan, R., Spoida, K., Surdin, T., Wollenweber, P., Mark, M.D., Herlitze, S., and Jancke, D. (2020). Separable gain control of ongoing and evoked activity in the visual cortex by serotonergic input. eLife 9, e53552.

- Cabrera, R., Filevich, O., García-Acosta, B., Athilingam, J., Bender, K.J., Poskanzer, K.E., and Etchenique, R. (2017). A visible-light-sensitive caged serotonin. ACS Chem Neurosci 8, 1036-1042. [CrossRef]

- Bellot-Saez, A., Stevenson, R., Kékesi, O., Samokhina, E., Ben-Abu, Y., Morley, J.W., and Buskila, Y. (2021). Neuromodulation of astrocytic K(+) clearance. Int J Mol Sci 22, 2520.

- Gantz, S.C., Levitt, E.S., Llamosas, N., Neve, K.A., and Williams, J.T. (2015). Depression of serotonin synaptic transmission by the dopamine precursor L-DOPA. Cell Rep 12, 944-954. [CrossRef]

- Fuxe, K., Dahlström, A.B., Jonsson, G., Marcellino, D., Guescini, M., Dam, M., Manger, P., and Agnati, L. (2010). The discovery of central monoamine neurons gave volume transmission to the wired brain. Prog. Neurobiol. 90, 82-100. [CrossRef]

- Jadi, M., Polsky, A., Schiller, J., and Mel, B.W. (2012). Location-dependent effects of inhibition on local spiking in pyramidal neuron dendrites. PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002550.

- Tremblay, R., Lee, S., and Rudy, B. (2016). Gabaergic interneurons in the neocortex: from cellular properties to circuits. Neuron 91, 260-292. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.R., Runyan, C.A., Wang, F.L., and Sur, M. (2012). Division and subtraction by distinct cortical inhibitory networks in vivo. Nature 488, 343-348. [CrossRef]

- Madden M, Mathur B. (2023). Transclaustral circuit strength is attenuated by serotonin. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 53 PSTR456.20.

- Anderson, T.L., Keady, J.V., Songrady, J., Tavakoli, N.S., Asadipooya, A., Neeley, R.E., Turner, J.R., and Ortinski, P.I. (2024). Distinct 5-HT receptor subtypes regulate claustrum excitability by serotonin and the psychedelic, DOI. Prog Neurobiol 240, 102660. [CrossRef]

- Wong KLL (2021) Serotonergic modulation of the claustrum. Doctoral thesis, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

| Figure | Group(s) and Sample Size | Test/Fit | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suppl. Figure S1 | Control vs KA+GBZ for Charge (n = 13) | Paired t-test | t(12) = 1.47, p =0.17 |

| Figure 3B | Overall response rate(n = 182) | Chi square | X2(1, 182) = 25.1, p = 0.00005 |

| PN1 (n = 19) vs Average Response rate (n = 182) | X2 (1, 201) = 7.12, p = 0.008 | ||

| PN2 (n = 42) vs Average Response rate (n = 182) | X2(1, 272) = 0.001, p = 0.974 | ||

| Figure 3C | PN subtype effect on Peak amplitude (n = 182) | Welch’s ANOVA | F(4, 123) = 3.53, p = 0. 0.023 |

| Pairwise comparison | Tukey’s test | p > 0.05 | |

| Related to Figure 3 | PN subtype effect on Charge(n = 182) | Welch’s ANOVA | F(4, 123) = 7.77, p = 0.0010 |

| Pairwise comparison | Tukey’s test | p > 0.05 | |

| Related to Figure 3 | PN subtype effect on Exponential decay (n = 182) | Welch’s ANOVA | F(4, 122) = 0.35, p = 0.84 |

| Related to Figure 3 | PN subtype effect on Peak time (n = 182) | Welch’s ANOVA | F(4, 123) = 0.26, p = 0.902 |

| Related to Figure 3 | PN subtype effect on Conductance (n = 182) | Welch’s ANOVA | F(4, 123) = 3.53, p = 0. 0.023 |

| Pairwise comparison | Tukey’s test | p > 0.05 | |

| Figure 4B | Drug effect on % decrease in charge (n = 41) | Welch’s ANOVA | F(2, 38) = 15.818, p = .00001 |

| Pairwise comparison | Tukey’s test | 1A vs 2A: p < 0.05$$$1A vs 2C: p < 0.0001$$$2A vs 2C: p = 0.21 | |

| Figure 7C | Control vs 5-HT for Input50 (n = 19) | Paired t-test | t(18) = -3.70, p = 0.0016 |

| Figure 7D | Control vs 5-HT for Slope (n = 19) | Paired t-test | t(18) = -1.12, p = 0.28 |

| Figure 7E | Control vs 5-HT for Output50 (n = 19) | Paired t-test | t(18) = -0.24, p = 0.82 |

| Figure 7F | Control vs 5-HT for OutputMax (n = 19) | Paired t-test | t(18) = 0.59, p = 0.56 |

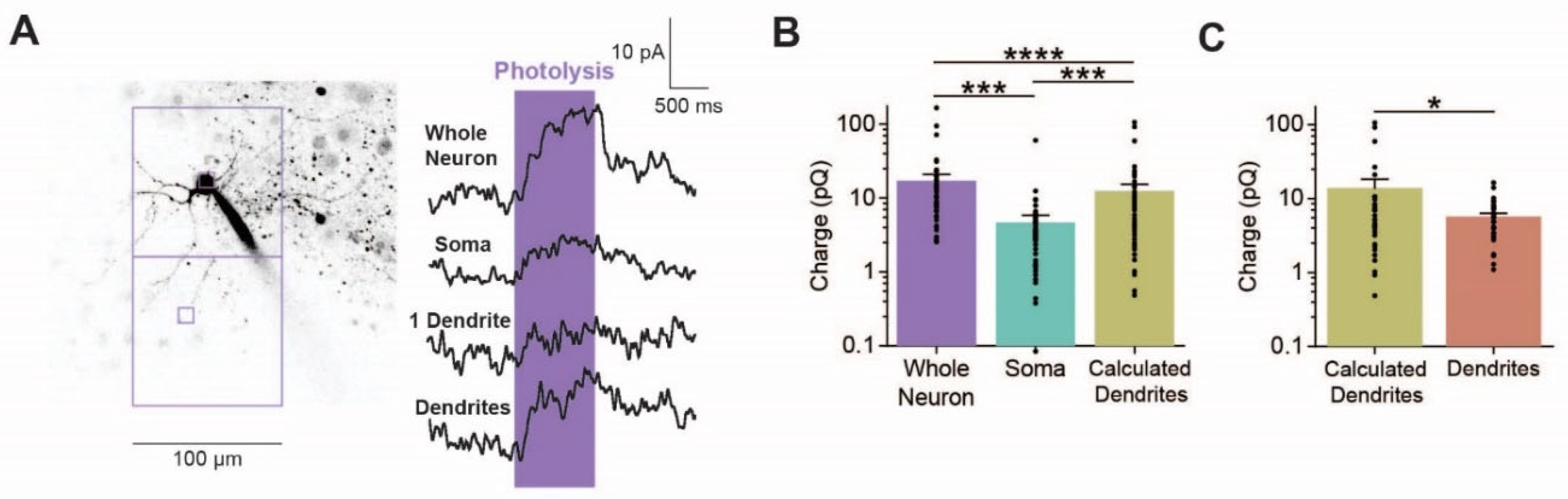

| Figure 9B | Location effect on Charge (n = 50) | One-way repeated ANOVA | F(2, 147) = 4.89, p = 0.008 |

| Whole neuron vs soma for charge (n = 50) | Paired t-test | t(49) = 4.31, p = 0.00008 | |

| Whole neuron vs calculated dendrites for charge (n = 50) | Paired t-test | t(49) = 3.91, p = 0.0002 | |

| Soma vs calculated dendrites for charge (n = 50) | Paired t-test | t(49) = 3.48, p = 0.001 | |

| Figure 9C | calculated dendrites vs dendrites for charge (n = 31) | Paired t-test | t(30) = 2.32, p = 0.03 |

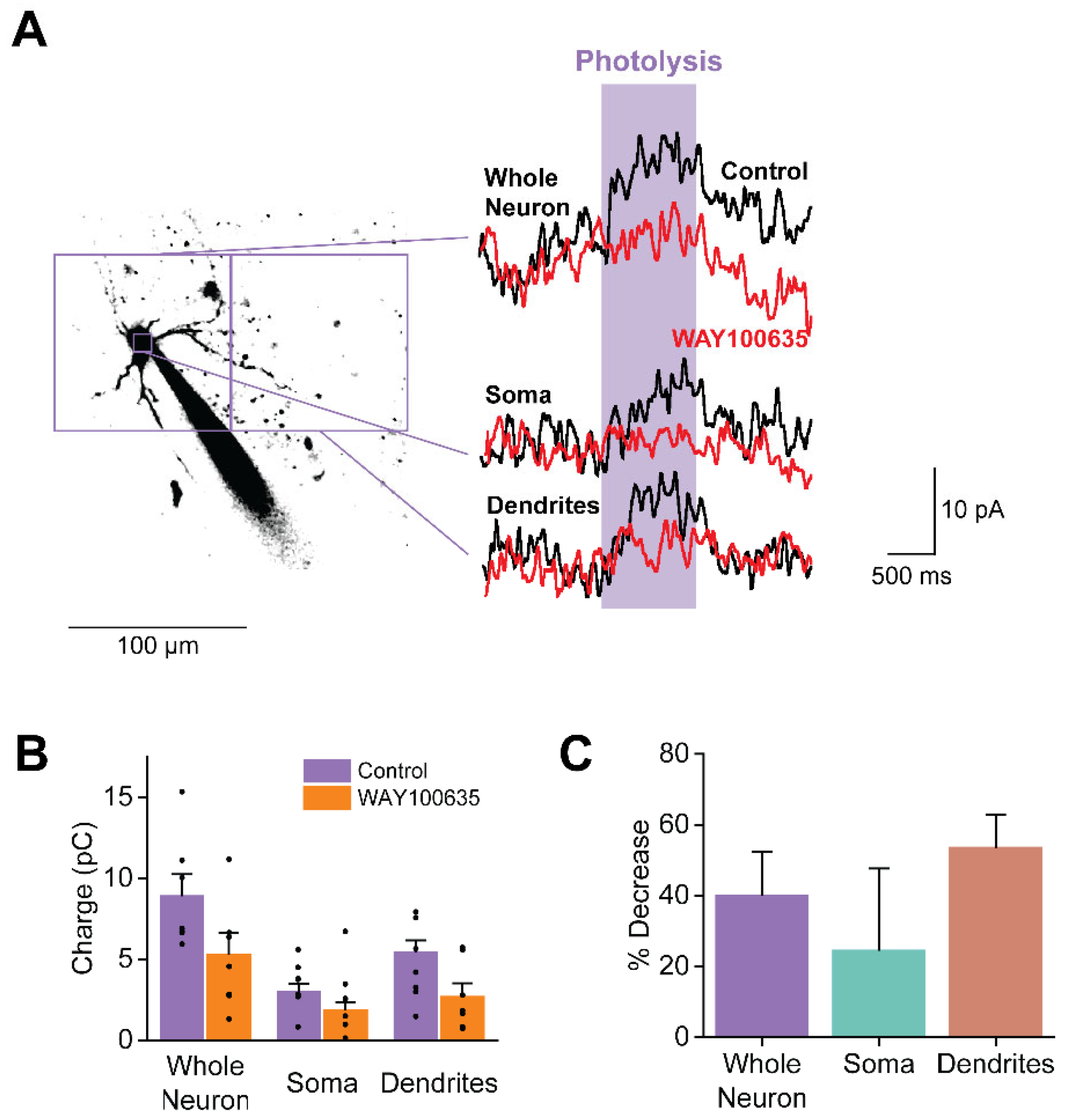

| Figure 10B | Main effect of Drug for 1 s Integral (n = 7) | Two-way repeated ANOVA | F(1, 38) = 11.64, p = 0.002 |

| Main effect of Location Current for 1 s Integral (n = 7) | F(2, 38) = 14.10, p = 0.00003 | ||

| Interaction between Drug and Location for 1 s Integral (n = 7) | F(1, 38) = 13.28, p = 0.000004 | ||

| Figure 10C | Location effect on Charge (n = 7) | One-way repeated ANOVA | F(2, 18) = 0.93, p = 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).