Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Total Phenolic Content, Total Flavonoid Content and Antioxidant Activity of P. grandidieri Leaf Extracts

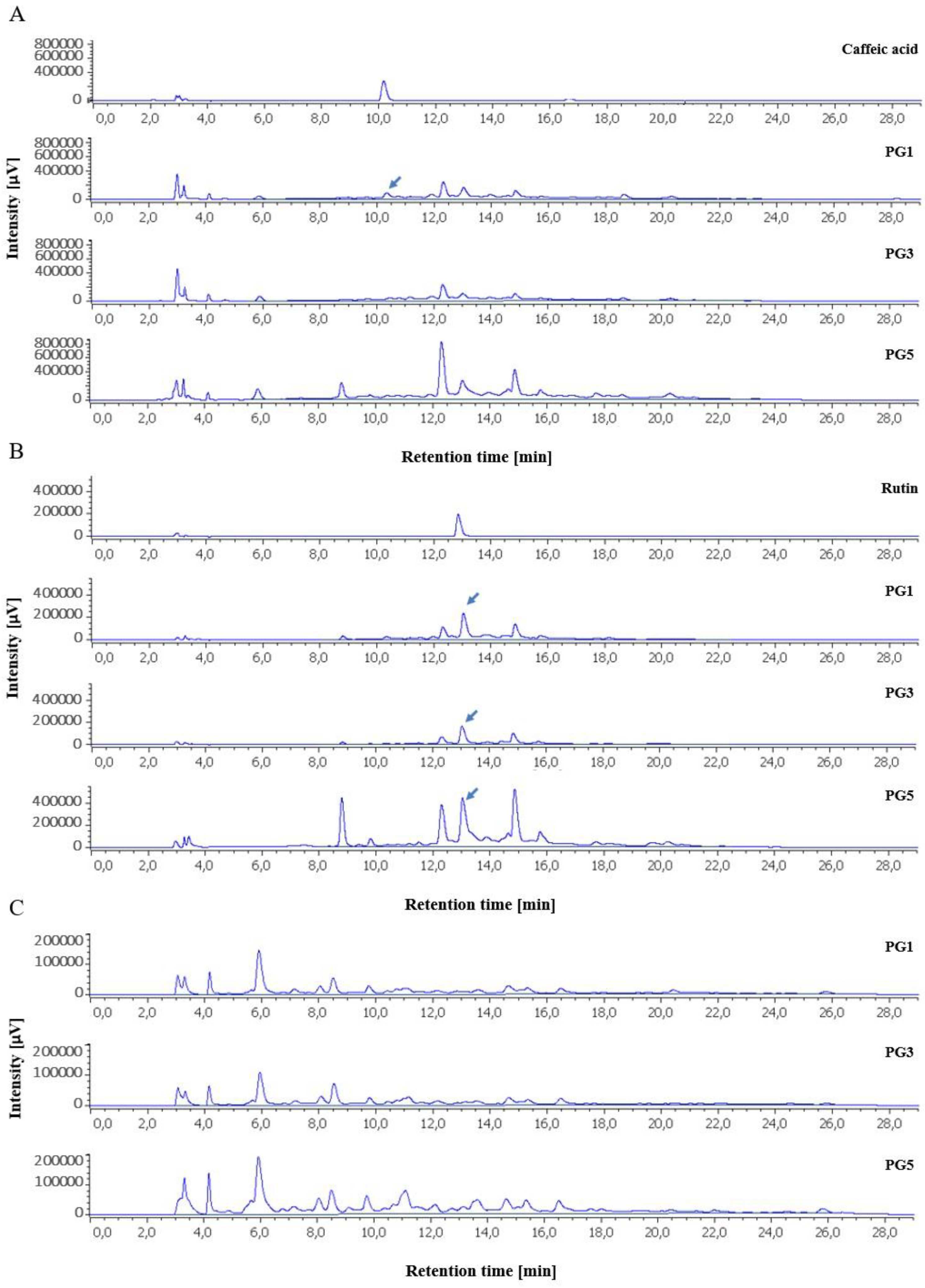

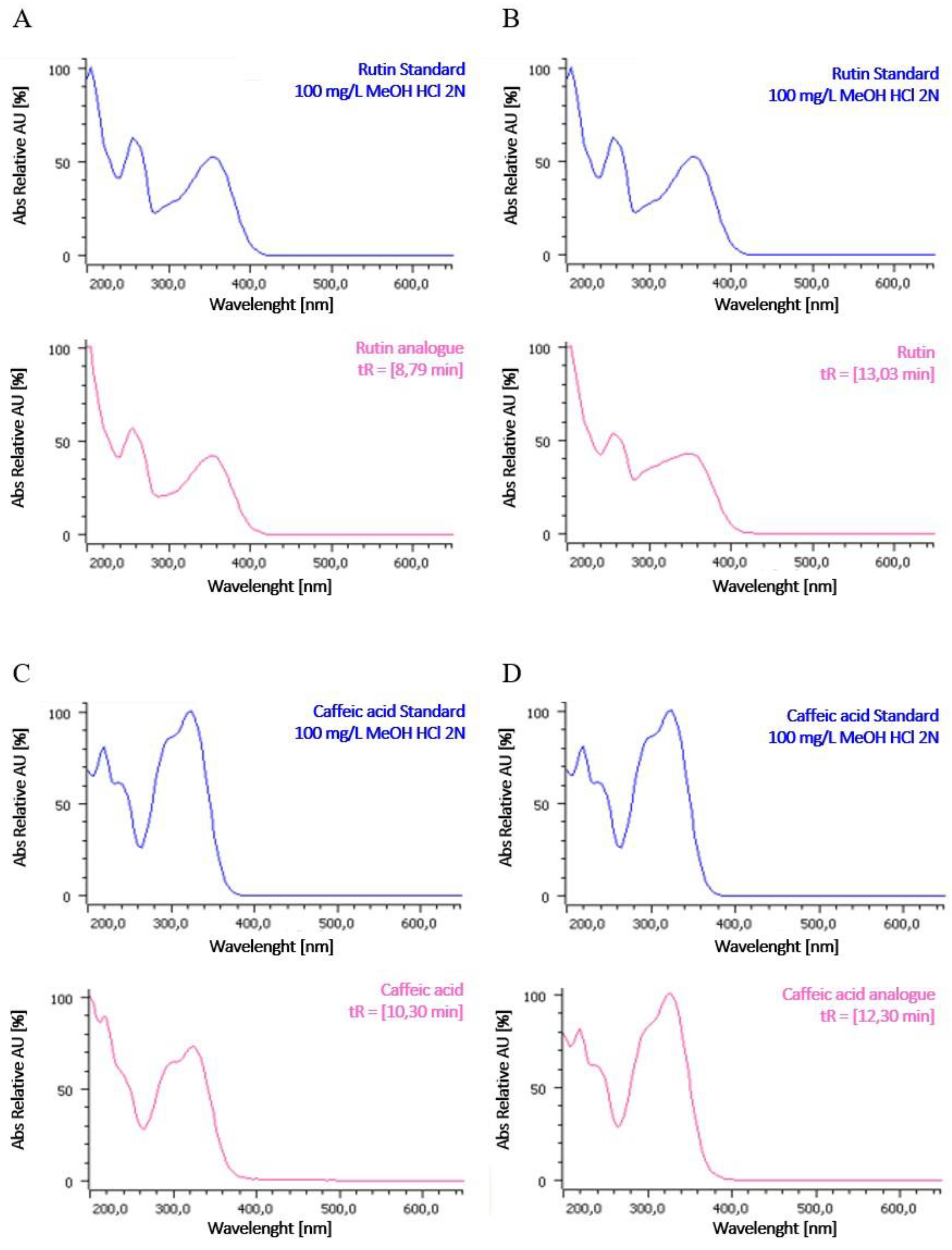

2.2. HPLC Profile of P. grandidieri Leaf Extracts

| PG1 | PG 2 | PG 3 | PG4 | PG5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC | Total phenolic content (CGAE) (evaluated at 280 nm) | 15.81±1.28a | 5.33 ±0.37b | 14.05 ±1.14a | 15.51 ±0.96a | 17.14 ±1.57a |

| Flavonoids | Flavan-3-ols and Flavanones (CNE) (evaluated at FDL 280-330 nm) | 3.55 ±0.15a | 2.34 ±0.15c | 2.51 ±0.39c | 1.29 ±0.30d | 3.09 ±0.16b |

| Flavonols and flavones (CRE) (evaluated at 360 nm) | 6.61 ±0.40c | 2.11 ±0.2e | 5.31 ±0.58d | 7.48±0.28b | 8.77 ±0.58a | |

2.3. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of P. grandidieri Leaf Extracts

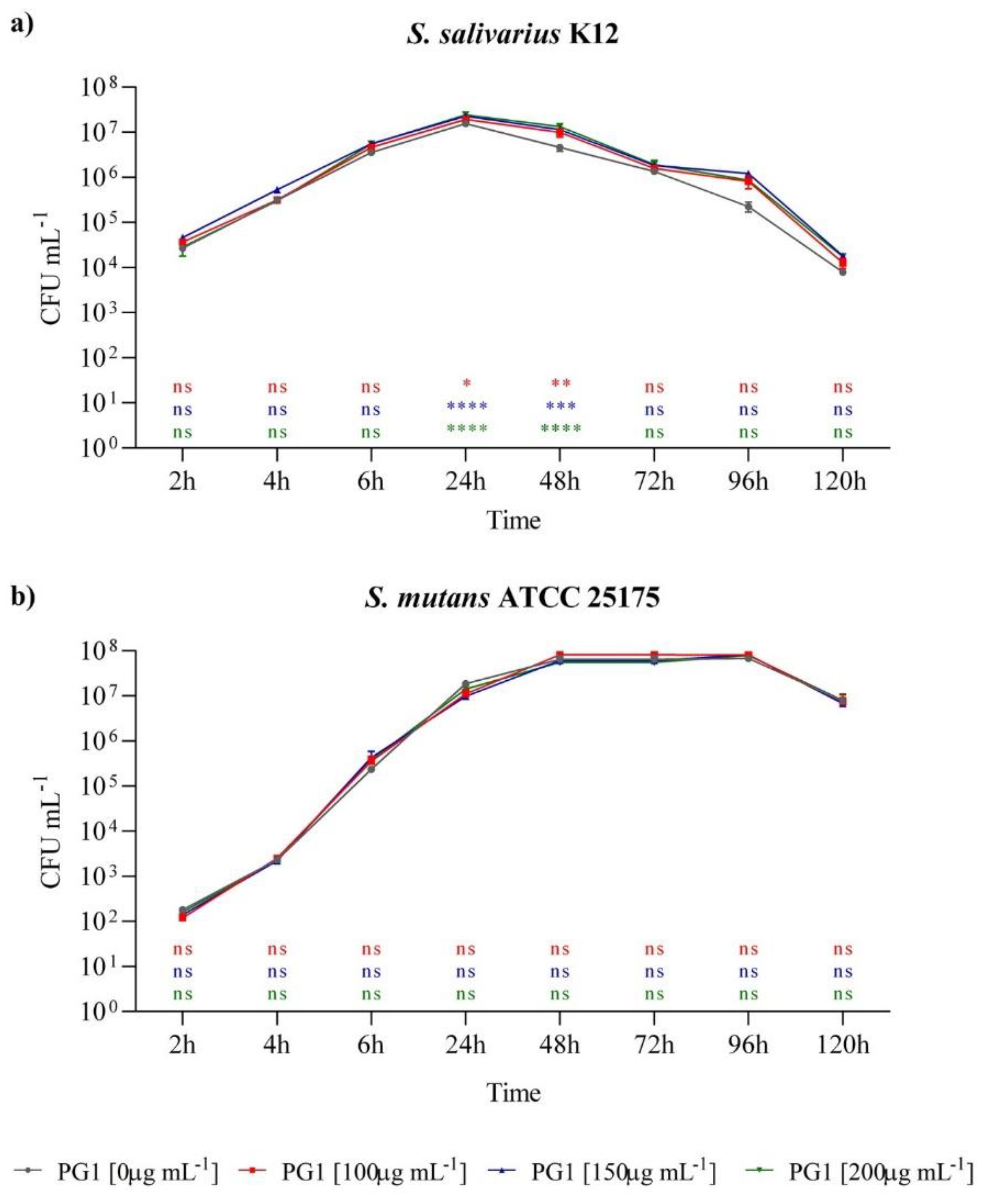

2.4. In Vitro Prebiotic Effect of P. grandidieri Aqueous Extract on Streptococcus salivarius

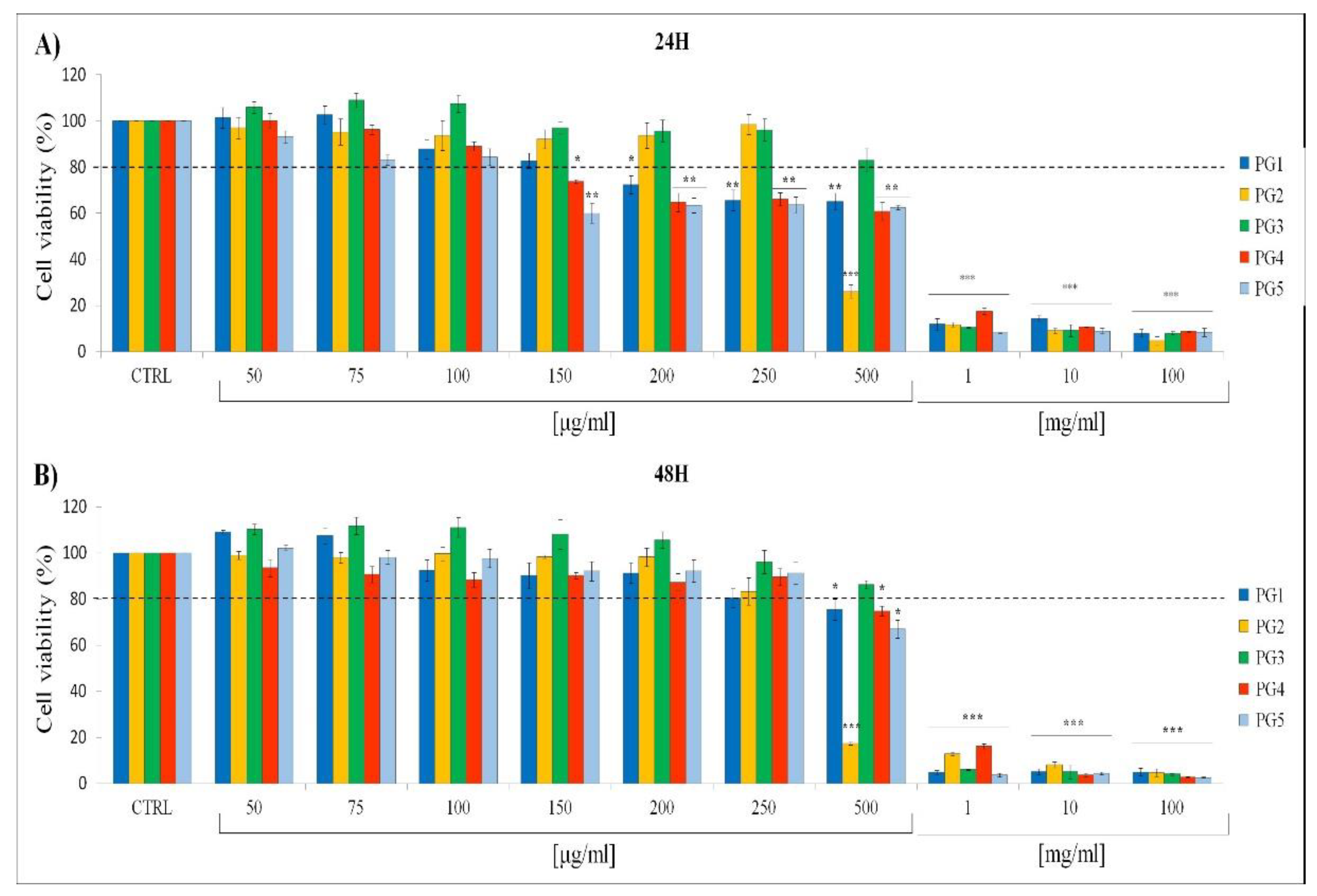

2.5. In Vitro Cytotoxic Effects of P. grandidieri Leaf Extracts

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Solutions

4.2. Sample collection and extraction

| Extract | Solvent | Ratio (w/v) | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG1 | H2O | 1:50 | 25°C | 24 |

| PG2 | H2O | 1:50 | 60°C | 6 |

| PG3 | H2O | 1:50 | 60°C | 24 |

| PG4 | EtOH 70% | 1:10 | 25°C | 4 |

| PG5 | EtOH 70% | 1:10 | 25°C | 24 |

4.3. Total Phenolic Content

4.4. Total Flavonoid Content

4.5. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

4.6. HPLC/DAD/FL Analysis

4.7. Identification of Polyphenols

4.8. Antibacterial Assay

4.9. Fitness Assay

4.10. Cell Culture and Treatment

4.11. In Vitro Cell Viability Studies

4.12. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altaf, M.M.; Khan, M.S.A.; Ahmad, I. Diversity of Bioactive Compounds and Their Therapeutic Potential. In New Look to Phytomedicine; Mohd Sajjad, Ahmad Khan, Iqbal Ahmad, Debprasad Chattopadhyay, Eds.; Academic Press, 2019; Pp 15-34, ISBN 9780128146194. [CrossRef]

- Nath, R.; Kityania, S.; Nath, D.; Talkudar, A.D.; Sarma, G. An extensive review on medicinal plants in the special context of economic importance. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2023, 16, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebode, O.; Kandala, N.B.; Chilton, P.J.; Lilford, R.J. Use of traditional medicine in middle-income countries: a WHO-SAGE study. Health Policy Plan 2016, 31, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2014). Antibacterial resistance: global report on surveillance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564748 (accessed on 08 July 2024).

- Abdallah, E.M.; Alhatlani, B.Y.; de Paula Menezes, R.; Martins, C.H.G. Back to Nature: Medicinal Plants as Promising Sources for Antibacterial Drugs in the Post-Antibiotic Era. Plants 2023, 12, 3077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeresham, C. Natural products derived from plants as a source of drugs. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2012, 4, 200––201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Parvin, S.; Reza, A.; Das, S.; Miah, M.M.U.; Karim, S. Potential Role and International Trade of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants in the World. EJFOOD 2023, 5, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.M.; Dinerstein, E. The global 200: Priority Ecoregions for Global. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 2002, 89, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriamparany, J.N.; Brinkmann, K.; Jeannoda, V. Effects of socio-economic household characteristics on traditional knowledge and usage of wild yams and medicinal plants in the Mahafaly region of south-western Madagascar. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanampamaharana, R.H.; Randriamavo-Solo, H.N.A.; Rasoamananjara, J.A.; Rafatro, H. Combination of phytotherapy by using herbal medicine from Paederia thouarsiana leaf crude extract and conventional therapy for the care of painful oral conditions in a clinical dentistry practice. Int. Res. J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, B., Nahar, T.; Khalil, M.I.; Hossain, S. In vitro antibacterial activity of the ethanol extract of Paederia foetida L. (Rubiaceae) leaves Bangladesh. J. Life Sci. 2022, 19, 141–143.

- Morshed, H.; Islam, M.S.; Parvin, S.; Ahmed, M.U.; Islam, M.S.; Mostofa, A.G.M.; Sayeed, M.S.B. Antibacterial and cytotoxic activity of the methanol extract of Paederia foetida Linn. (Rubiaceae). J. Appl. Pharm. Sci, 2012; 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vicencio, M.C.G. Antibacterial efficacy of leaf extracts of Paederia foetida Linnaeus. J. Chem. Res. Adv. 2021, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, R.K.; Irchhaiya, R.; Dixit, V.; Alok, S. Paederia foetida linn: phytochemistry, pharmacological and traditional uses. IJPSR 2013, 4, 4525–4530. [Google Scholar]

- Giusti, F.; Caprioli, G.; Ricciutelli, M.; Vittori, S.; Sagratini, G. Determination of fourteen polyphenols in pulses by high performance liquid chromatography-diode array detection (HPLC-DAD) and correlation study with antioxidant activity and colour. Food chem. 2017, 221, 689––697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Loosdrecht, A.A.; Nennie, E.; Ossenkoppele, G.J.; Beelen, R.H.; Langenhuijsen, M.M. Cell mediated cytotoxicity against U 937 cells by human monocytes and macrophages in a modified colorimetric MTT assay: A methodological study. J. Immunol. Methods 1991, 141, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyaya, S. Screening of phytochemicals, nutritional status, antioxidant and antibacterial activity of Paederia foetida Linn. from different localities of Assam, India. J. Pharm. Res. 2013, 7, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierschner, J.; Cornil, J.; Egelhaaf, H.J. Optical bandgaps of π-conjugated organic materials at the polymer limit: experiment and theory. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platzer, M.; Kiese, S.; Herfellner, T.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eisner, P. How Does the Phenol Structure Influence the Results of the Folin-Ciocalteu Assay? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alén-Ruiz, F.; García-Falcón, M.S.; Pérez-Lamela, M.C.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Simal-Gándara, J. Influence of major polyphenols on antioxidant activity in Mencía and Brancellao red wines. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Casanella, O.; Moreno-Merchan, J.; Granados, M.; Nuñez, O.; Saurina, J.; Sentellas, S. Total Polyphenol Content in Food Samples and Nutraceuticals: Antioxidant Indices versus High Performance Liquid Chromatography. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anouar, E.H.; Gierschner, J.; Duroux, J.L.; Trouillas, P. UV/Visible spectra of natural polyphenols: a time-dependent density functional theory study. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.B.; Veríssimo, L.; Finimundy, T.; Rodrigues, J.; Oliveira, I.; Gonçalves, J; Fernandes, I.P.; Barros, L.; Heleno, S.A.; Calhelha, R.C. Chemical and Bioactive Screening of Green Polyphenol-Rich Extracts from Chestnut By-Products: An Approach to Guide the Sustainable Production of High-Added Value Ingredients. Foods 2023, 12, 2596. [CrossRef]

- Feng, R.Z.; Wang, Q.; Tong, W.Z.; Xiong, J.; Wei, Q.; Zhou, W.H.; Li, L.X. Extraction and antioxidant activity of flavonoids of Morus nigra. IJCEM 2015, 8, 22328–22336. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, P.P.; Marbaniang, K.; Sen, S.; Dey, B.K.; Talukdar, N.C. A review on phytochemistry of Paederia foetida Linn. Phytomedicine 2023, 3, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhe, W.; Zhang, R.; Peng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Guo, Z.; Xiao, J. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of polyphenolic compounds from Paederia scandens (Lour.) Merr. Using deep eutectic solvent: optimization; identification; and comparison with traditional methods. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 86,106005. [CrossRef]

- Priyanto, J.A.; Prastya, M.E.; Sinarawadi, G.S.; Datu’salamah, W.; Avelina, T.Y.; Yanuar, A.I.A.; Azizah, E.; Tachrim, Z.P.; Mozef, T. The antibacterial and antibiofilm potential of Paederia foetida Linn. leaves extract. J. Appl. Pharm.Sci. 2022, 12, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunita, M.; Ohiwal, M.; Elfitrasya, M.Z.; Rahawarin, H. Antibacterial activity of Paederia foetida leaves using two different extraction procedures against pathogenic bacteria. Biodiversitas 2023, 24, 5920––5927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, M.; Fu, X.; Ni, Y.; Chen, J.; Jian, S.; Wang, L.; Du, G. Protective effects of Paederia scandens extract on rheumatoid arthritis mouse model by modulating gut microbiota. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 226, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milutinović, M.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.; Rajilić-Stojanović, M. Plant extracts rich in polyphenols as potent modulators in the growth of probiotic and pathogenic intestinal microorganisms. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 688843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Daza, M.C.; Pulido-Mateos, E.C.; Lupien-Meilleur, J.; Guyonnet, D.; Desjardins, Y.; Roy, D. Polyphenol-mediated gut microbiota modulation: toward prebiotics and further. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 689456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Fernández, A.; Zorraquín-Peña, I.; Ferrer, M.D.; Mira, A.; Bartolomé, B.; Gonzalez de Llano, D.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V. Inhibition of oral pathogens adhesion to human gingival fibroblasts by wine polyphenols alone and in combination with an oral probiotic. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 2071–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostro, A.; Roccaro, A.S.; Bisignano, G.; Marino, A.; Cannatelli, M.A.; Pizzimenti, F.C.; Blanco, A.R. Effects of oregano; carvacrol and thymol on Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 56, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, B.; Anwar, F.; Ashraf, M.; Saari, N. Effect of drying techniques on the total phenolic. J. Med. Plants Res. 2012, 6, 161––167. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. Inhibitory effect of phenolic compounds and plant extracts on the formation of advance glycation end products: A comprehensive review. Int. Food Res. 2020, 130, 108933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twetman, S. Are we ready for caries prevention through bacteriotherapy? Braz. Oral Res. 2012, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghomari, O.; Sounni, F.; Massaoudi, Y.; Ghanam, J.; Drissi Kaitouni, L.B.; Merzouki, M.; Benlemlih, M. Phenolic profile (HPLC-UV) of olive leaves according to extraction procedure and assessment of antibacterial activity. Biotechnol. Rep. (Amst.) 2019, 23, e00347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant Phenolics: Extraction; Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyahya, A.; Guaouguaou, F.E.; El Omari, N.; El Menyiy, N.; Balahbib, A.; El-Shazly, M.; Bakri, Y. Anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of Moroccan medicinal plants: Phytochemistry; in vitro and in vivo investigations; mechanism insights; clinical evidences and perspectives. J. Pharm. Anal. 2022, 12, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri, Z.; Fakhri, S.; Nouri, K.; Wallace, C.E.; Farzaei, M.H.; Bishayee, A. Targeting Multiple Signaling Pathways in Cancer: The Rutin Therapeutic Approach. Cancers 2020, 12, 2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojković-Opsenica, D.; Andrić, F.; Šegan, S.; Trifković, J.; Tešić, Ž. Thin-layer chromatography in quantitative structure-activity relationship studies. Journal of Liquid Chromatography & Related Technologies 2018, 41, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.C.; Lee, J.N.; Kim, B.S.; Hyun, C.-G. Anti-Melanogenic Effects of Paederia foetida L. Extract via MAPK Signaling-Mediated MITF Downregulation. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, N.; Parbin, S.; Kausar, C.; Kar, S.; Mawatwal, S.; Das, L.; Deb, M.; Sengupta, D.; Dhiman, R.; Patra, S.K. (2019). Paederia foetida induces anticancer activity by modulating chromatin modification enzymes and altering pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression in human prostate cancer cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 130, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanto, J.A.; Prastya, M.E.; Primahana, G.; Randy, A.; Utami, D.T. Paederia foetida Linn Leaves-Derived Extract Showed Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Properties Against Breast Carcinoma Cell. HAYATI J. Biosci. 2023, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meo, M.C.; De Cristofaro, G.A.; Imperatore, R.; Rocco, M.; Giaquinto, D.; Palladino, A.; Zotti, T.; Vito, P.; Paolucci, M.; Varricchio, E. Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Olive Leaf from Five Italian Cultivars: Effects of Harvest-Time and Extraction Conditions on Phenolic Compounds and In Vitro Antioxidant Properties. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvouet-Grand, A.; Vennat, B.; Pourrat, A.; Legret, P. Standardisation d'un extrait de propolis et identification des principaux constituants [Standardization of propolis extract and identification of principal constituents]. J Pharm Belg. 1994, 49, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Cristofaro, G.A.; Paolucci, M.; Pappalardo, D.; Pagliarulo, C.; Sessini, V.; Lo Re, G. Interface interactions driven antioxidant properties in olive leaf extract/cellulose nanocrystals/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) biomaterials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seruga, M.; Novak, I.; Jakobek, L. Determination of Polyphenols Content and Antioxidant Activity of Some Red Wines by Differential Pulse Voltammetry; HPLC and Spectrophotometric Methods. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1208––1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; MacKinnon, S.; McDonald, J.; Vinqvist, M.; Craft, C.; Howell, A. Phenolics of Vaccinium berries and other fruit crops. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sateriale, D.; Facchiano, S.; Colicchio, R.; Pagliuca, C.; Varricchio, E.; Paolucci, M.; Volpe, M.G.; Salvatore, P.; Pagliarulo, C. In vitro Synergy of Polyphenolic Extracts From Honey; Myrtle and Pomegranate Against Oral Pathogens; S. mutans and R. dentocariosa. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgione, G.; De Cristofaro, G.A.; Sateriale, D.; Pagliuca, C.; Colicchio, R.; Salvatore, P.; Paolucci, M.; Pagliarulo, C. Pomegranate Peel and Olive Leaf Extracts to Optimize the Preservation of Fresh Meat: Natural Food Additives to Extend Shelf-Life. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Kirby, W.; Sherris, J.; Turck, M. (1966). Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disc method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1966, 45, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antibacterial Susceptibility Testing; 32nd ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne; PA; USA; 2022; ISBN 978-1-68440-134-5.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for Dilution Antibacterial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria that Grow Aerobically; Approved Standard-Tenth Edition; CLSI Document M07-A10; Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute: Waine; PA; USA; 2015. Available online: https://clsi.org/media/1632/m07a10_sample.pdf.

| Extract | TPC (mg GAE g−1) | TFC (mg QuercetinE g-1) | % oxidative inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| PG1 | 40.58 ± 4.25a | 30.07 ± 1.09 a | 83.95 ± 0.87a |

| PG2 | 33.05 ± 5.31a | 32.06 ± 0.29 a | 71.53 ± 1.56b |

| PG3 | 37.19 ± 2.66a | 31.76 ± 0.99 a | 77.62 ± 4.20a |

| PG4 | 21.62 ± 2.39b | 19.52 ± 1.41 b | 58.86 ± 4.36c |

| PG5 | 23.23 ± 0.74b | 26.63 ± 3.19 a | 59.09 ± 1.75c |

| Extract | IC20 (24 hours) (μg/ml) | IC20 (48 hours) (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| PG1 | 168±1.8b | 283±1.6c |

| PG2 | 360±2.7d | 258±2.1c |

| PG3 | 528±3.8e | 600±3.2e |

| PG4 | 170±2.5b | 246±1.9c |

| PG5 | 125±2.1a | 240±1.7c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).