Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

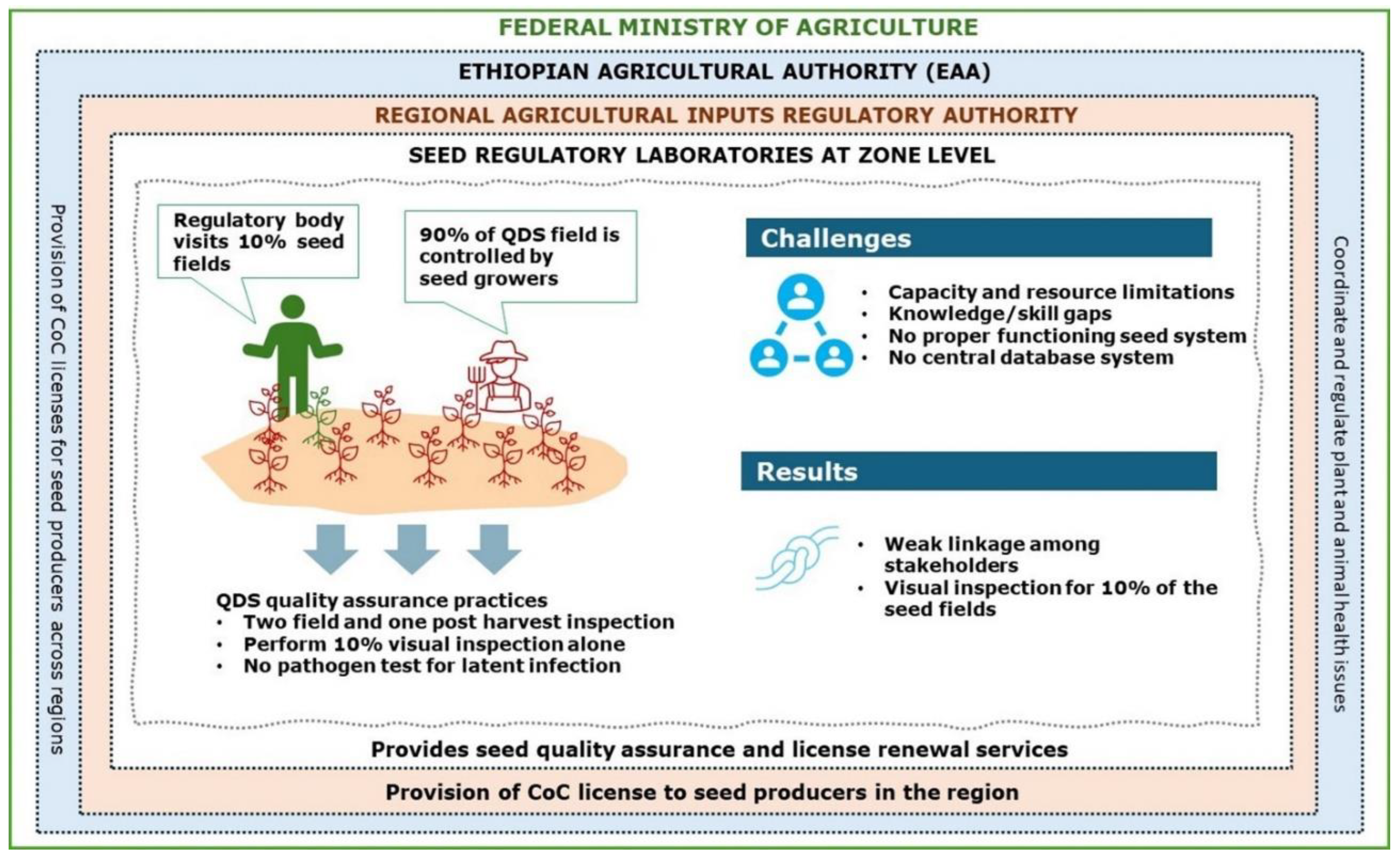

2.1. Description of Seed Regulatory Laboratories

2.2. Data Collection

Literature Review

Seed Regulatory Laboratory Managers and Technician Interviews

2.3. Analytical Framework

3. Results

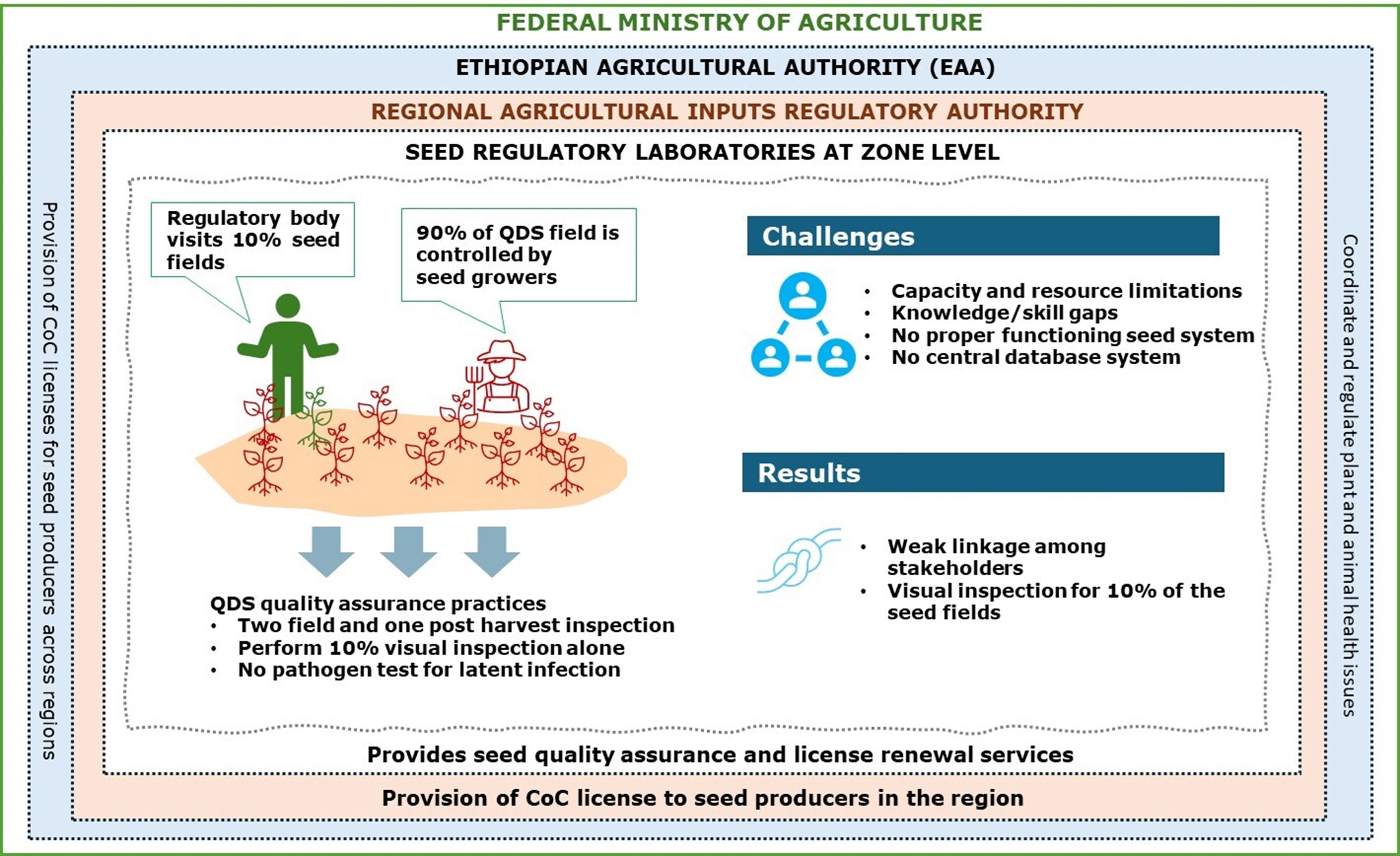

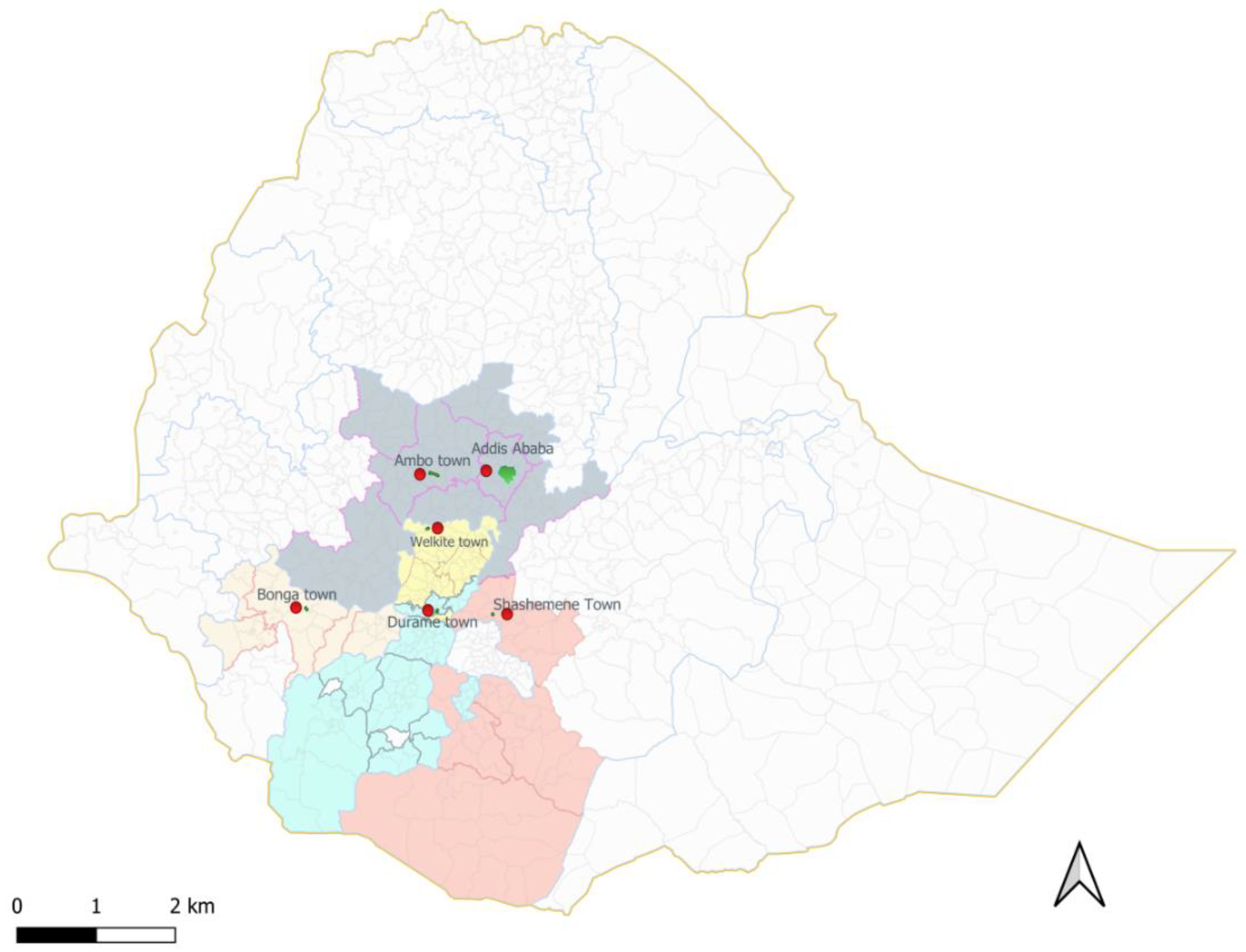

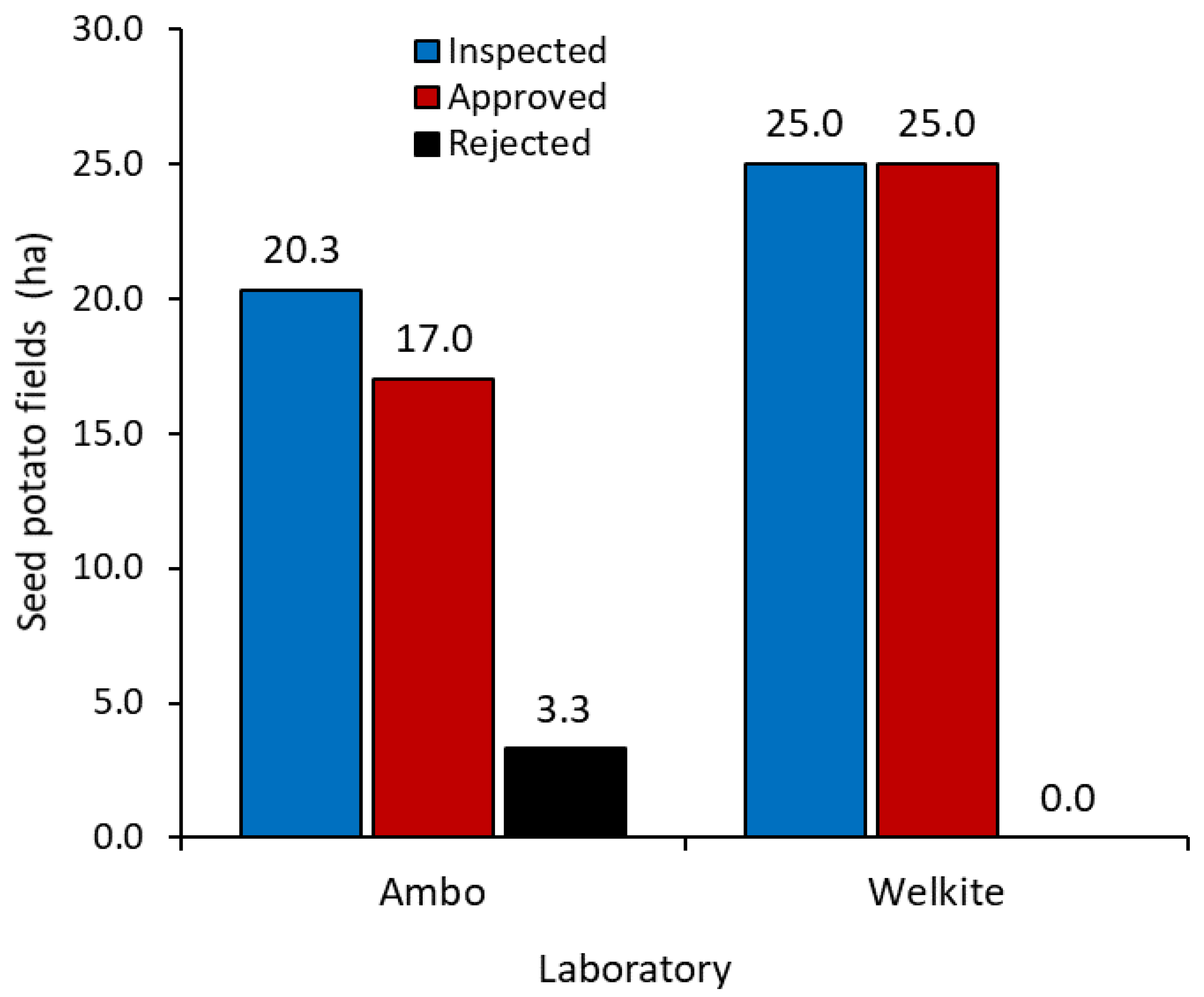

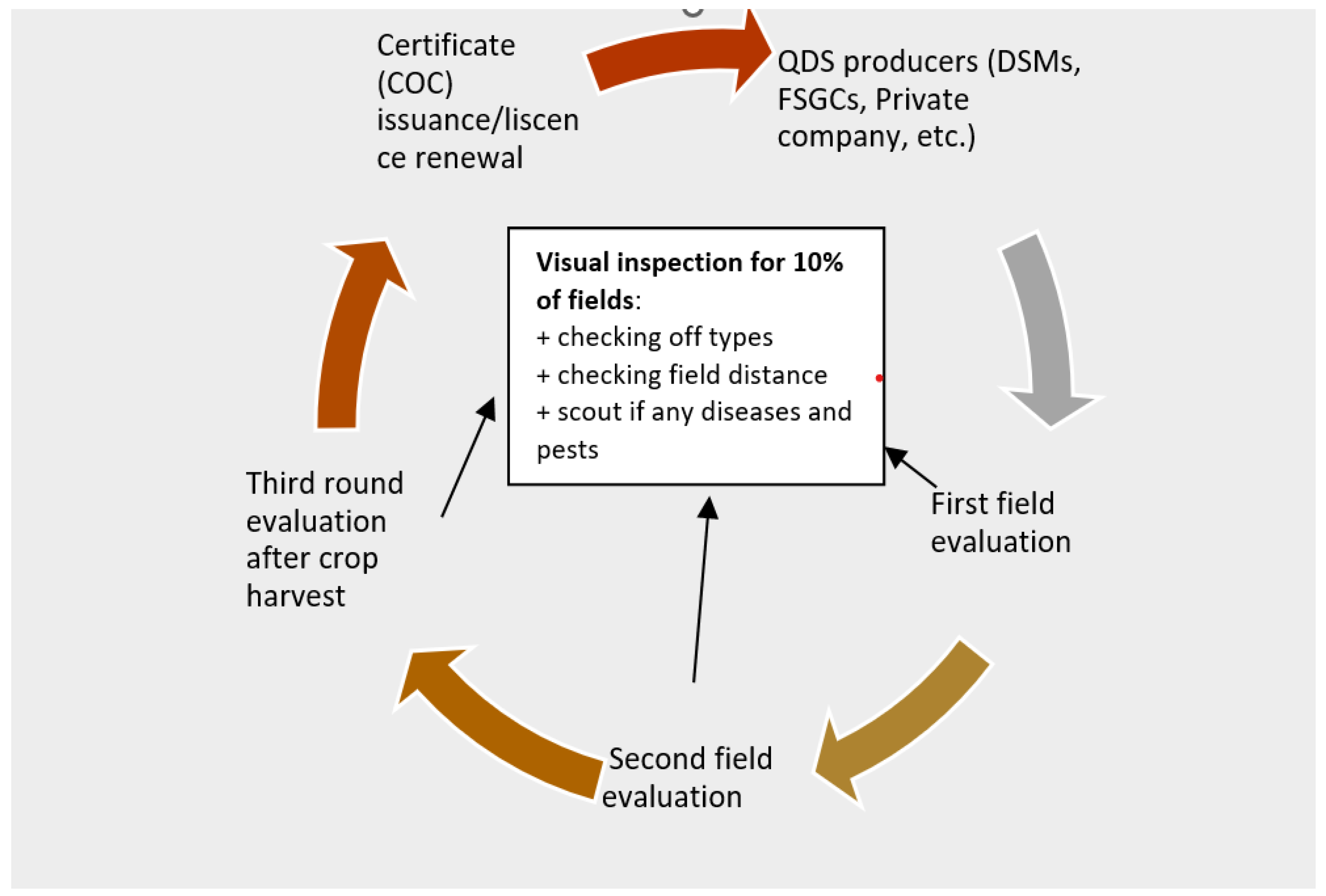

3.1. Seed Quality Assurance Practices in Ethiopia

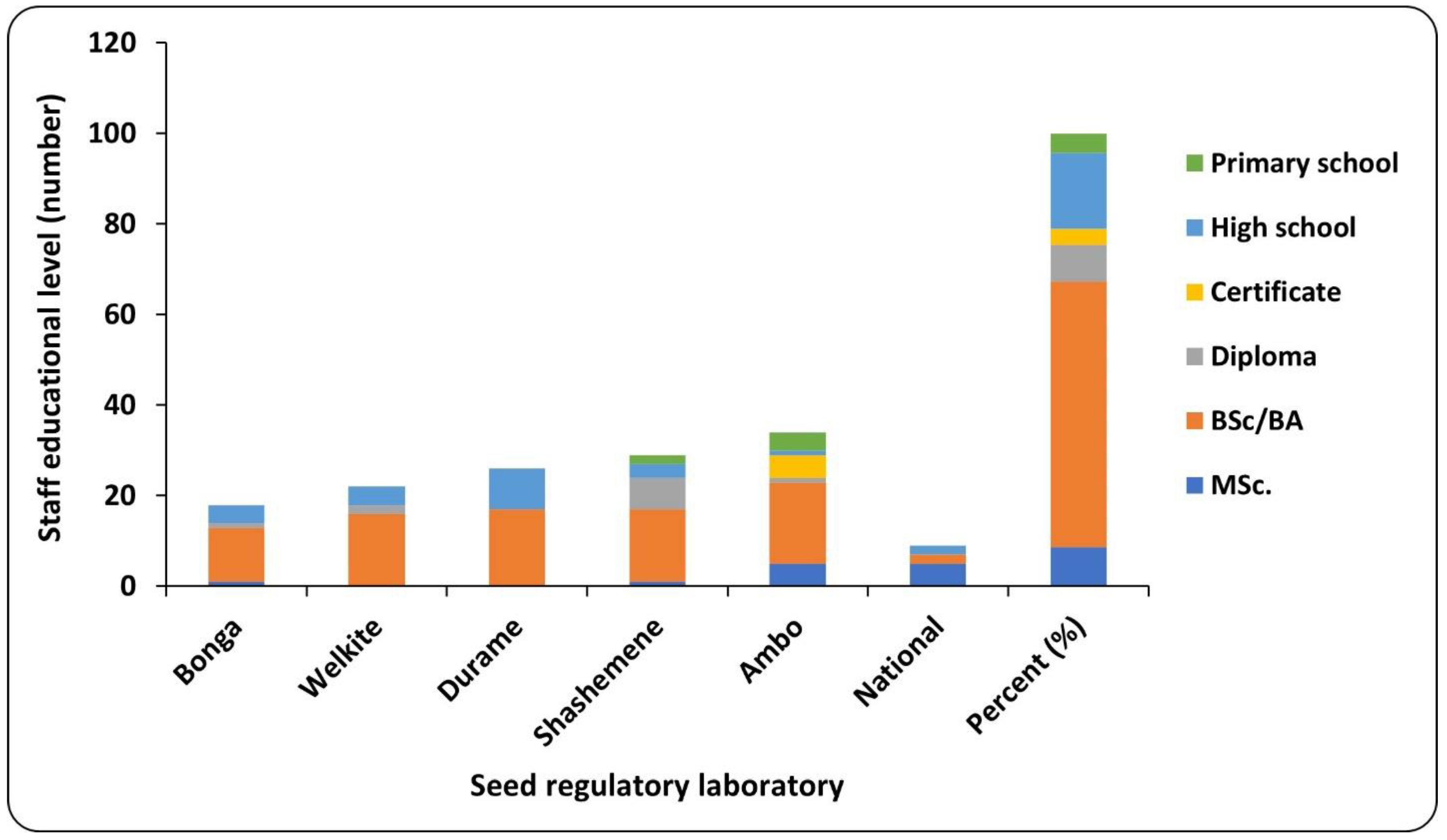

3.2. Human Resource Capacity and Gender Disaggregation

3.3. Physical Infrastructure, Logistics and Seed Testing Facilities

3.4. Challenges for Effective Seed Quality Assurance in Ethiopia

4. Discussion

4.1. Seed Quality Assurance Mechanisms in Ethiopia

4.2. Seed Quality Assurance Standards in Ethiopia

4.3. Implications for Integrated Seed Sector Development

- o

- Focus on developing high-yield, disease-resistant seed varieties that are well-suited to local conditions.

- o

- Encourage local initiatives to enhance the availability and accessibility of quality seeds within communities.

- o

- Provide comprehensive training on best practices in seed production, post-harvest handling, and storage techniques.

- o

- Improve extension services to effectively disseminate knowledge about quality assurance, seed management and innovative practices to farmers.

- o

- Ensure that policies facilitate seed access, distribution, and regulation while also safeguarding farmers’ rights.

- o

- Foster collaboration between the government, private sector, the industry, and NGOs to drive investment and innovation in potato seed systems.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- NAIP (National Agricultural Investment Plan), 2022. National Agricultural Investment Plan 2021-2030. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Agriculture, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 105p. 20231005145754.pdf (nepad.org) [Accessed on 20 March 2024].

- Mellor, J.W., Dorosh, P., 2010. Agriculture and the economic transformation of Ethiopia. Ethiopia Strategy Support Program 2, working paper 010, 45pp.

- Worldometer, 2024. Population/Ethiopia-population/. Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world. [Accessed on January 3, 2024].

- Diriba, G., 2020. Agricultural and Rural Transformation in Ethiopia: Obstacles, Triggers and Reform Considerations. Policy Working Paper 01/2020. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. https://eea-et.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Policy.

- Yigezu, W.G., 2021. The challenges and prospects of Ethiopian agriculture. Cogent Food and Agriculture, 7(1):1923619. [CrossRef]

- Hirpa, A., Meuwissen, M. P., Tesfaye, A., Lommen, W. J., Oude Lansink, A., Tsegaye, A., Struik, P. C., 2010. Analysis of seed potato systems in Ethiopia. Am. J. Pot Res, 87:537–552. [CrossRef]

- Tarekegn, K., Mogiso, M., 2020. Assessment of improved crop seed utilization status in selected districts of Southwestern Ethiopia. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 6(1):1816252. [CrossRef]

- Demo, P., Lemaga, B., Kakuhenzire, R., Schulz, S., Borus, D., Barker, I., Woldegiorgis, G., Parker, M.L., Schulte-Geldermann, E., 2015. Strategies to improve seed potato quality and supply in Sub-Saharan Africa: Experience from interventions in five countries. In: Low J, Nyongesa M, Quinn S and Parker M (Eds), Potato and sweet potato in Africa: Transforming the value chains for food and nutrition security. CABI, Nosworthy Way Wallingford, Oxford shire OX10 8DE, UK. Pp. 155-167. [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Y., Almekinders, C.J.M., Schulte, R.P.O., Struik, P.C., 2019. Potatoes and livelihoods in Chencha, southern Ethiopia. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 88:105-111. [CrossRef]

- Wubet, G.K., Zemedu, L., Tegegne, B., 2022. Value chain analysis of potato in Farta District of south Gondar zone, Amhara national state of Ethiopia. Heliyon, 8:e09142. [CrossRef]

- Haug, R., Hella, J. P., Mulesa, T. H., Kakwera, M. N., Westengen, O. T., 2023. Seed systems development to navigate multiple expectations in Ethiopia, Malawi and Tanzania. World Development Sustainability, 3: 100092. [CrossRef]

- Mulesa, T. H., Dalle, S. P., Makate, C., Haug, R., Westengen, O. T., 2021. Pluralistic seed system development: a path to seed security? Agronomy, 11 (2):372. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, S., Woldegiorgis, G., Hailariam, G., Abdurahman, A., van de Haar, J., Shiferaw, W., 2013. Sustainable seed potato production in Ethiopia: from farm-saved to quality declared seed. In: Woldegiorgis G, Schulz S, Berihun B (Eds). Proceedings of the National Workshop on Seed Potato Tuber Production and Dissemination: Experiences, Challenges and Prospects, 12-14 March 2012, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia, Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research and Amhara Regional Agricultural Research Institute, pp. 60-71. Available at. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/57048.

- Tessema, L., Negash, W., Kakuhenzire, R., Alemu, G. B., Hussen, E. S., Fentie, M. E., 2023a. Seed health trade-offs in adopting quality declared seed in potato farming systems. Crop Science, 64(3):1340-1348. [CrossRef]

- Nigussie, M., Kalsa, K., Ayana, A., Alemu, D., Hassena, M., Zeray, T., Adam, A., Mengistu, A., 2020. "Status of Seed Quality Control and Assurance in Ethiopia: Required Measures for Improved Performance." Technical report. [CrossRef]

- Alemu, D., Bishaw, Z., Zeray, T., Ayana, A., Hassena, M., Sisay, D. T., Kalsa, K. K., 2023. National Seed Sector Coordination in Ethiopia: Status, Challenges, and Way Forward. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/377395995.

- Tessema, L., Kakuhenzire, R., Seid, E. Negash K., McEwan M., 2024. The bacterial wilt burden in the seed potato system in Ethiopia: a case of Oromia and Southern Nations’ regions. Indian Phytopathology, 77 (2). [CrossRef]

- Getnet, M., Teshome, A., Snel, H., Alemu, D., 2023. Potato seed system in Ethiopia: challenges, opportunities, and leverage points. Stichting Wageningen Research Ethiopia, Addis Ababa. SWRE-RAISE-FS-23-025.

- Etherton, B. A., Choudhury, R. A., Alcala Briseno, R. I., Mouafo-Tchinda, R. A., Plex Sula, A. I., Choudhury, M., Adhikari, A., Lei, S.L., Kraisitudomsook, N., Buritica, J.R., Cerbaro, V.A., Ogero, K., Cox, C.M., Walsh, S.P., Andrade-Piedra, J.L., Omondi, B. A., Navarrete, I., McEwan, M.A., Garrett, K. A., 2024. Disaster plant pathology: Smart solutions for threats to global plant health from natural and human-driven disasters. Phytopathology®, 114(5), 855-868. [CrossRef]

- Benson, T., Spielman, D., Kassa, L., 2014. Direct Seed Marketing Program in Ethiopia in 2013: An Operational Evaluation to Guide Seed-sector Reform. IFPRI Discussion Paper 01350, 68p. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272300332.

- Wimalasekera, R., 2015. Role of Seed Quality in Improving Crop Yields. In: Hakeem, K. (eds) Crop Production and Global Environmental Issues. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Bentley, J. W., Andrade-Piedra, J., Demo, P., Dzomeku, B., Jacobsen, K., Kikulwe, E., Kromann, P., Kumar, P. L., McEwan, M., Mudege, N., Ogero, K., Okechukwu, R., Orrego, R., Ospina, B., Sperling, L., Walsh, S., Thiele, G., 2018. Understanding root, tuber, and banana seed systems and coordination breakdown: A multistakeholder framework. Journal of Crop Improvement, 32(5), 599–621. [CrossRef]

- Tessema, L., Kakuhenzire, R., McEwan, M., 2023b. Latent bacterial wilt and viral infection burden in the seed potato system in Ethiopia: policy implications for seed potato. Policy Brief 02. International Potato Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10568/132185.

- Spielman, D.J., Gatto, M., Wossen, T., McEwan, M., Abdoulaye, T., Maredia, M.K., Hareau, H., 2021. Regulatory Options to Improve Seed Systems for Vegetatively Propagated Crops in Developing Countries. IFPRI Discussion Paper 02029. 55p. available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstractid=3868901.

- Tadesse, Y., Almekinders, C.J.M., Griffin, D., Struik, P.C., 2020. Collective Production and Marketing of Quality Potato Seed: Experiences from Two Cooperatives in Chencha, Ethiopia. Forum for Development Studies, 47(1): 139-156. [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, S., Lie, R., van Mierlo, B., Struik, P.C., Lemaga, B., Leeuwis, C., 2020. Analysis of a monitoring system for bacterial wilt management by seed potato cooperativs in Ethiopia: Challenges and future direction. Sustainability, 12:3580. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B. D., Mays, M. Z., Martz, W., Castro, K. M., DeWalt, D. A., Pignone, M. P., Hale, F. A., 2005. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med, 2005(3):514-522. [CrossRef]

- Maroya, N., Balogum, M., Aighewi, B., Mignouna, D.B., Kumar, P.L., Asiedu, R., 2022. Transforming yam seed system in West Africa. Pp.421-452. In: G. Thiele et al. (eds.), Root, Tuber and Banana Food System Innovations. [CrossRef]

- Sulle, E., Pointer, R., Kumar, L., McEwan, M., 2022. Inventory of novel approaches to seed quality assurance mechanisms for vegetatively propagated crops (VPCs) in seven African countries. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA). International Potato Center (CIP). 48 p. [CrossRef]

| Inspection stage | Yes/No | Reasons |

| Early vegetative (30-50 days after planting) | Yes | To check crop emergence status, isolation distance, and varietal purity |

| Flowering (55-70 days) | Yes | To check off types, insect pests, bacterial diseases, viruses, etc. |

| Postharvest (in store) |

Yes | To assess seed quality, disease presence, mechanical damage, cracking, storage conditions |

| Human Resource | Male | Female | Total | Percent |

| Zonal laboratory managers | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3.6 |

| Seed testing managers | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Seed testing lab technicians | 10 | 7 | 17 | 12.3 |

| Field seed inspectors | 18 | 5 | 23 | 16.7 |

| Certification officers | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Seed quality controllers | 5 | 2 | 7 | 5.1 |

| Product quality inspectors | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Plant pathologist (BSc.) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Human resource managers | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3.6 |

| Estate managers | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1.4 |

| Planning and evaluation | 4 | 0 | 4 | 3.0 |

| Procurement assistants | 8 | 12 | 20 | 14.5 |

| Financial inspection and audit | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2.2 |

| Support staff | 6 | 6 | 12 | 8.7 |

| Records officers | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3.6 |

| ICT assistants | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 |

| Security guards | 10 | 4 | 14 | 10.1 |

| Drivers | 10 | 0 | 10 | 7.3 |

| Secretaries | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3.0 |

| Total | 91(65.9) | 47(34.1) | 138 | 100 |

| Equipment | Bonga | Welkite | Durame | Shashemene | Ambo | National |

| Refrigerators | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Deep freezers | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Oven dries | 2 | 2(1) | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Seed counters | 2(1) | 2(2) | 2 | 3(2) | 0 | 0 |

| Microscopes | 2 | 4(2) | 2(1) | 1 | 2(1) | 2 |

| Seed potato graders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PCR machines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Centrifuge machine | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shaker/incubators | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2(1) | 0 |

| ELISA plate reader | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BW-ELISA kits | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BW & viruses pocket testing kits | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Magnifying lens | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Analytical balances | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2(1) | 1 | 0 |

| Moisture testers | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Autoclaves | 1 | 1(1) | 0 | 1 | 1(1) | 0 |

| Laminar flow hoods | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Growth chambers | 0 | 2(2) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Grinding machine | 0 | 2(1) | 0 | 2(1) | 0 | 0 |

| Logistics | Bonga | Welkite | Durame | Shashemene | Ambo | National |

| Own building | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Vehicle (N) | 2(1) | 3(2) | 3(1) | 2(1) | 2(1) | 0 |

| Computer | 9(2) | 15(5) | 10 | 13(3) | 14(2) | 1 |

| Printer | 6 | 6 | 5(1) | 2 | 6(2) | 1 |

| Photocopier | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Scanner | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| LCD projector | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Element of seed quality assurance | Challenges observed |

| Organization of the seed regulatory authority |

|

| Rules and standards |

|

| Data collection for seed quality assurance |

|

| Decision-making by zonal seed regulatory bodies |

|

| Enforcement of rules compliance with QDS standards |

|

| Communication across seed regulatory authority |

|

| Resource for seed quality assurance |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).