Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Introductory Remarks - Construction of Equilibrium Size Distribution Taking into Account the Growth and Mortality Rates of Trees and the Desired/Assumed Share of a Given Species in the Particular Woodland Community Type

2.2.2. Division of the Białowieża Forest into Sustainability Units

2.2.3. Determination of the Actual Diameter Distributions of Tree Species Occurring in Individual Sustainability Units

2.2.4. Determination of Model, Species-Specific Tree-Size Distributions in Particular Sustainability Units

2.2.5. Comparison of Theoretical vs. Real Diameter Distributions: Calculation of Deficit and Surplus (Total and Effective) Trees of Individual Species; Determining the Approximate Size of Regeneration Spots

3. Results

3.1. Number and Size Distribution of Sustainability Units

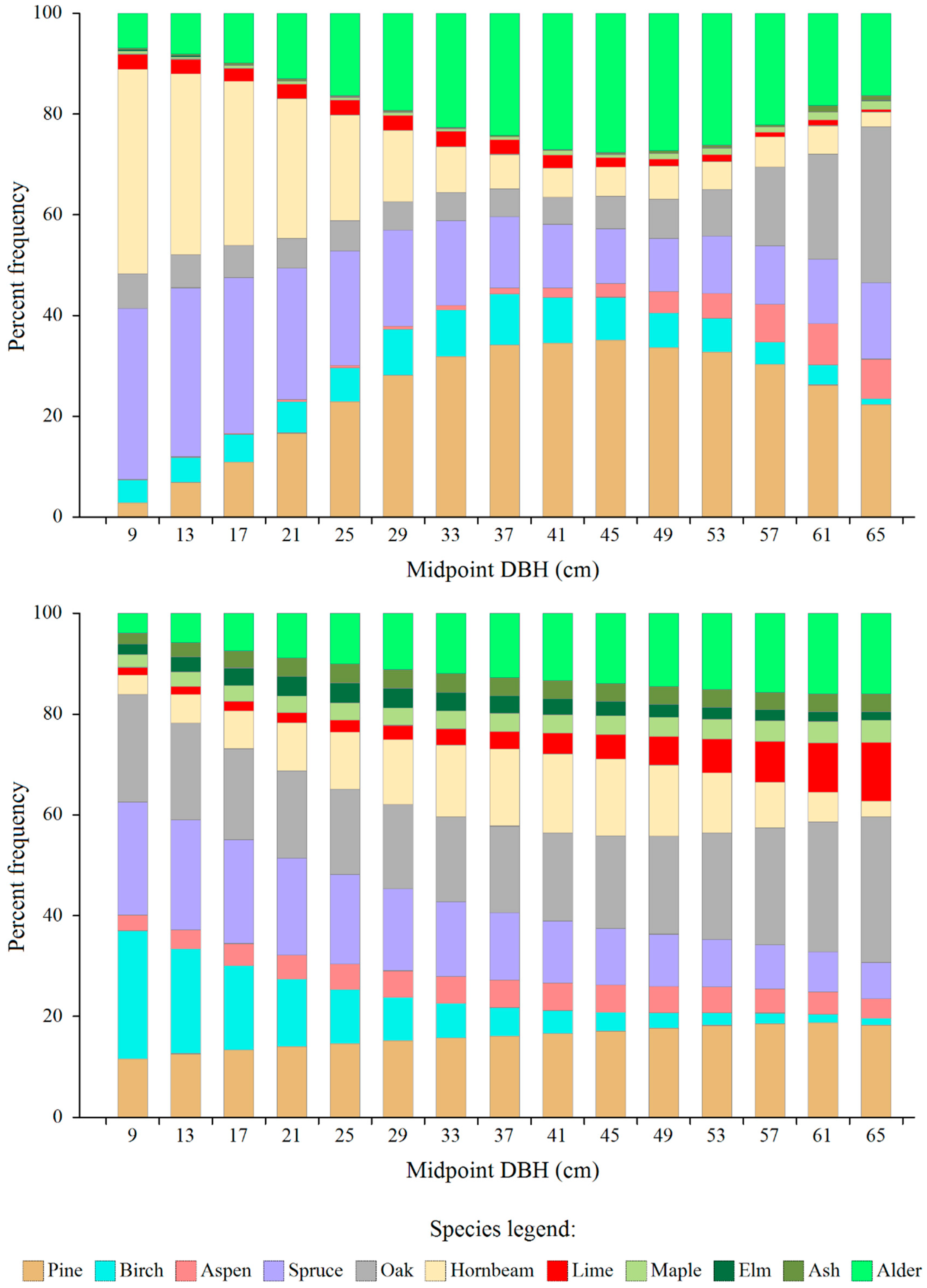

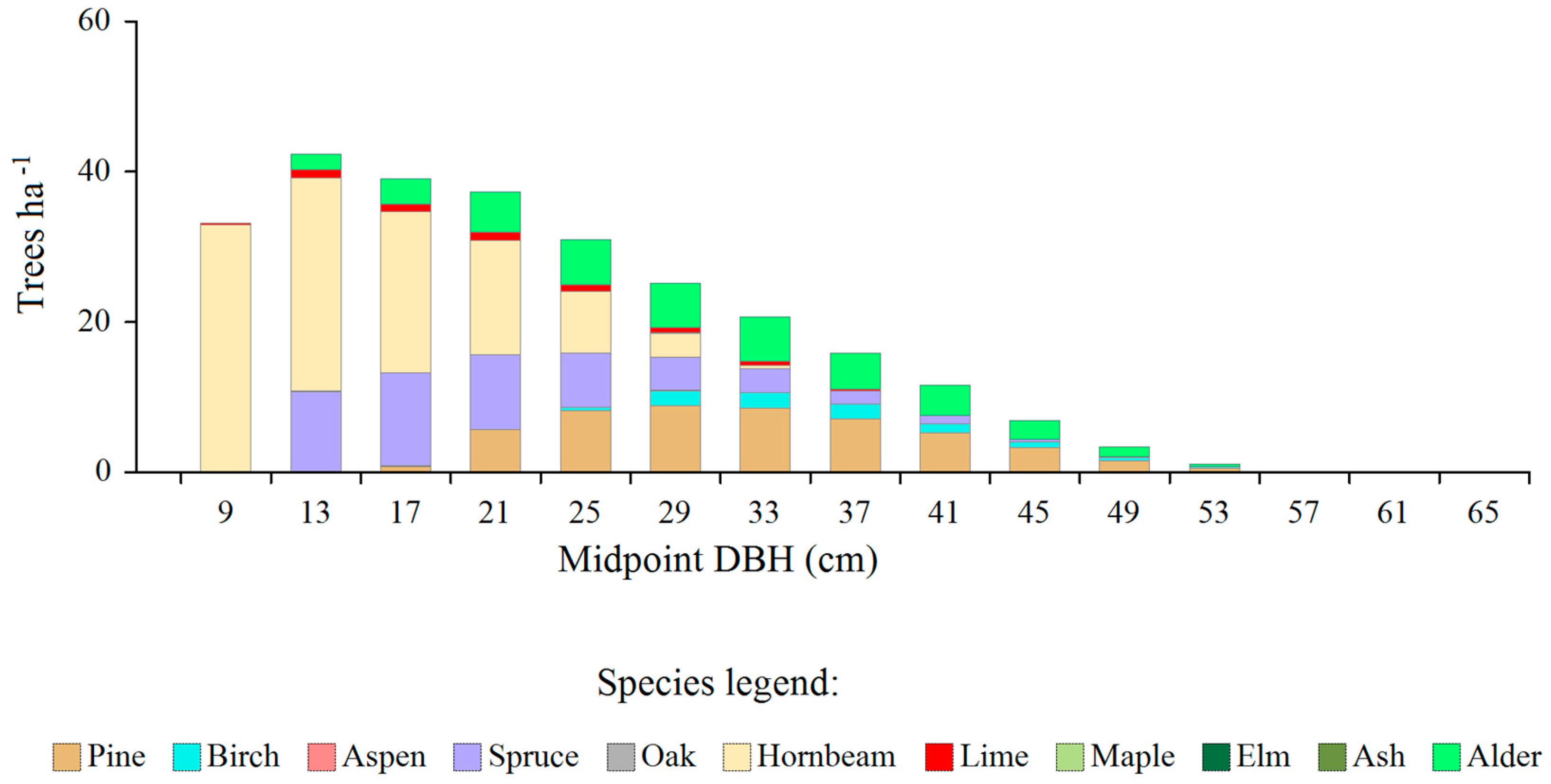

3.2. Actual Tree Diameter Distributions of Individual Species in the Sustainability Units (Determined on the Basis of Their Occurrence in Major Woodland Community Types)

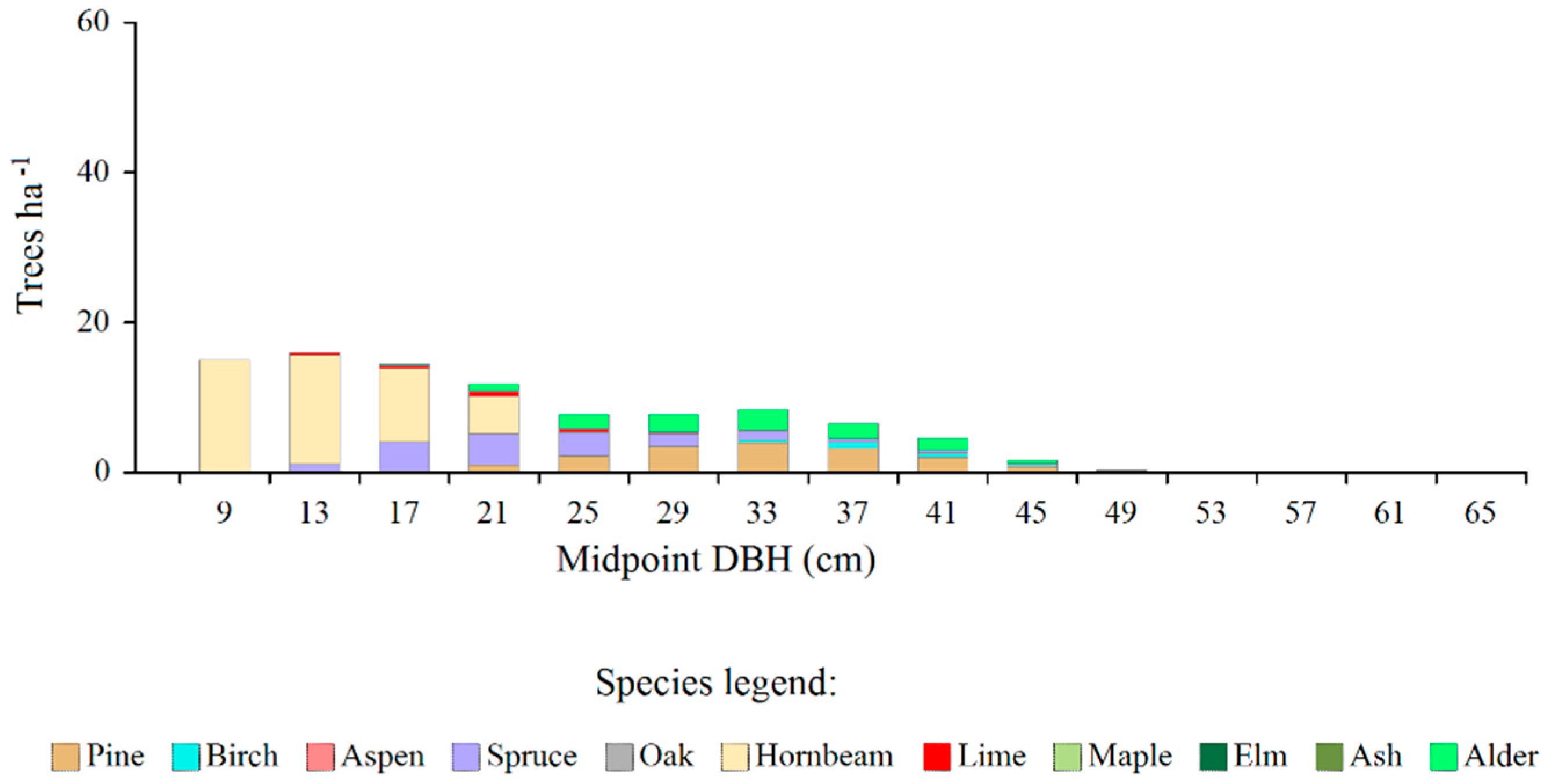

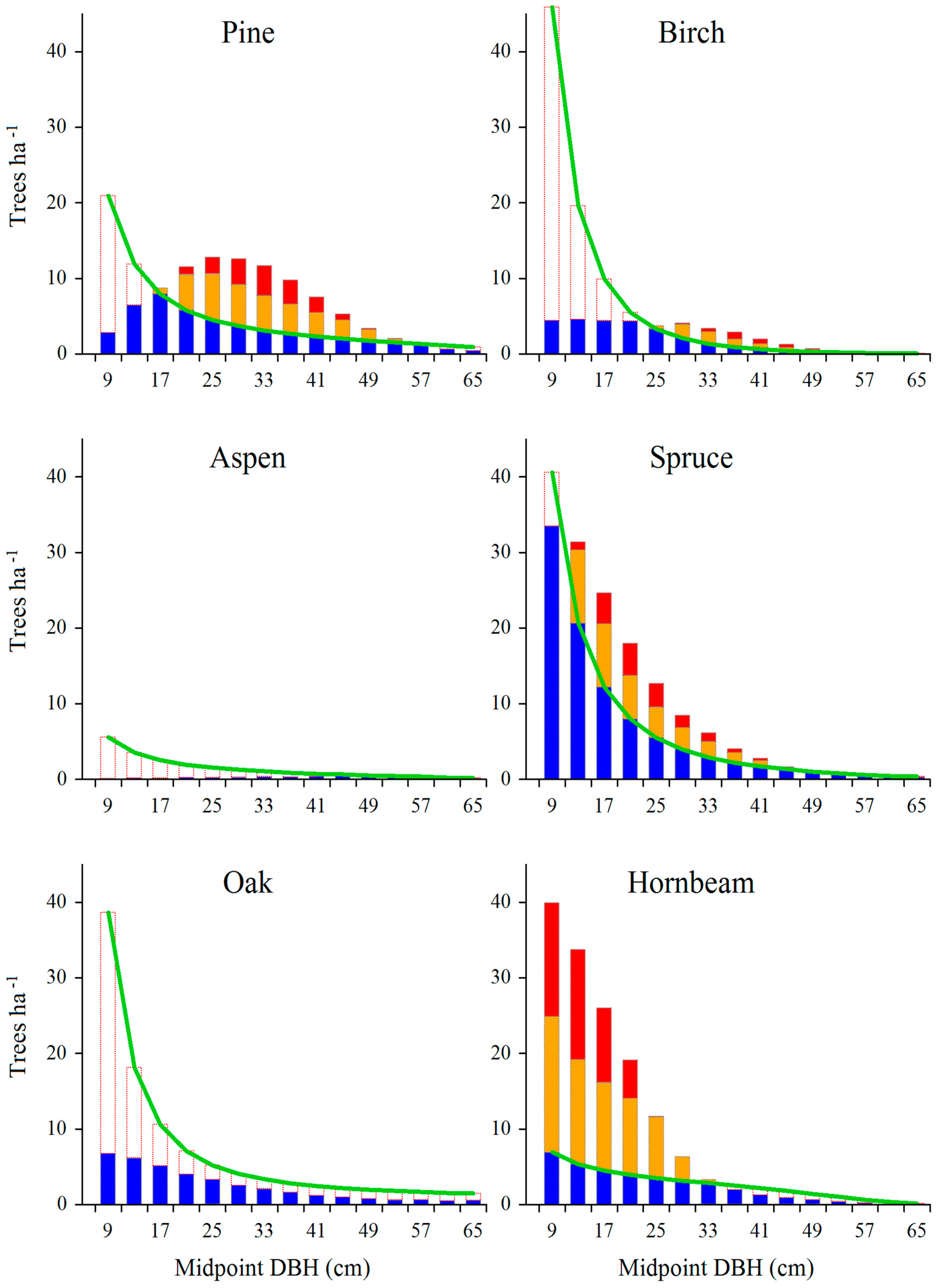

3.3. Model (Target, Desirable), Species-Specific Tree Diameter Distributions of Particular Species in Sustainability Units (Taking into Account the Assumed Role of Particular Tree Species in a Given Sustainability Unit)

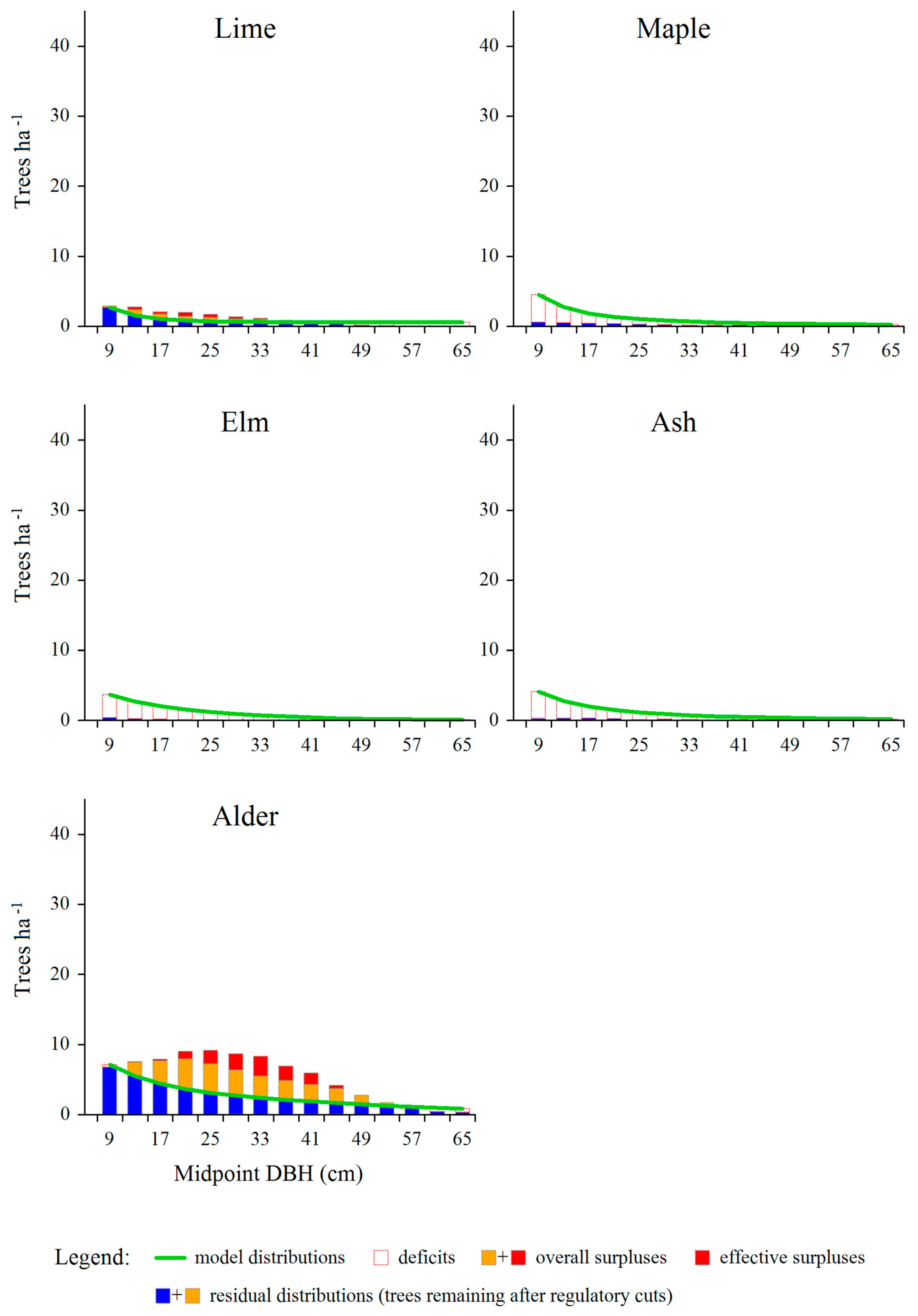

3.4. Total Number of Surplus and Deficit Trees

3.5. Effective Surpluses

3.6. Estimated Area of Regeneration Spots (Regeneration Patches) (Required to Reduce Species-Specific Deficits in the Smallest Diameter Class)

4. Discussion

4.1. Balanced Demography of Tree Population: A Key to Maintain High Natural Values of Woodland Communities

4.2. Common Deviations Between Actual and Theoretical Tree Size Distributions in Białowieża Forest: Major Causes and Implications

4.3. Looking for an Efficient Conservation Strategy of Białowieża Woodland Communities: A Passive or an Active Approach?

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kannan, R. , James, D.A. Effects of climate change on global biodiversity: a review of key literature. Trop. Ecol.

- Wilson, E.O. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. 2016. New York, NY: Liveright Publishing Corp.

- IPBES. Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 2019. IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. DOI. [CrossRef]

- Sala, O.E.; Chapin, F.S.; Armesto, J.J.; Berlow, E.; Bloomfield, J.; Dirzo, R.; Huber-Sanwald, E.; Huenneke, L.F.; Jackson, R.B.; Kinzig, A.; Leemans, R.; Lodge, D.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Oesterheld, M.; Poff, N.L.; Sykes, M.T.; Walker, B.H.; Walker, M.; Wall, D.H. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100. Science. 2000, 287(5459), 1770–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkening, J.L.; Magness, D.R.; Thompson, L.M.; Lynch, A.J. A brave new world: Managing for biodiversity conservation under ecosystem transformation. Land. 2023, 12, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galatowitsch, S.; Frelich, L.; Phillips-Mao, L. Regional climate change adaptation strategies for biodiversity conservation in a midcontinental region of North America. Biol. Conserv. 2009, 142, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Bringing nature back into our lives. 2020. European Commission. Brussels.

- Pötzelsberger, E.; Bauhus, J.; Muys, B.; Wunder, S.; Bozzano, M.; Farsakoglou, A.-M.; Schuck, A.; Lindner, M.; Lapin, K. Forest biodiversity in the spotlight – what drivers change? 2021. European Forest Institute. [CrossRef]

- Muys, B.; Angelstam, P.; Bauhus, J.; Bouriaud, L.; Jactel, H.; Kraigher, H.; Müller, J.; Pettorelli, N.; Pötzelsberger, E.; Primmer, E.; Svoboda, M.; Thorsen, B.J.; Van Meerbeek, K. Forest Biodiversity in Europe. 2022. From Science to Policy 13. European Forest Institute. [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B. Białowieża Forest as a biodiversity spot (In Polish with English Summary). Sylwan. 2017, 12, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B. Conservation of forest biodiversity: a segregative or an integrative approach? Sylwan. 2022, 7, 470–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götmark, F. Habitat management alternatives for conservation forests in the temperate zone: Review, synthesis, and implications. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2013, 306, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampoorter, E.; Barbaro, L.; Jactel, H.; Baeten, L.; Boberg, J.; Carnol, M.; Castagneyrol, B.; Charbonnier, Y.; Dawud, S.M.; Deconchat, M.; Smedt, P.D.; Wandeler, H.D.; Guyot, V.; Hättenschwiler, S.; Joly, F.-X.; Koricheva, J.; Milligan, H.; Muys, B.; Nguyen, D.; Ratcliffe, S.; Raulund-Rasmussen, K.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; van der Plas, F.; Keer, J.V.; Verheyen, K.; Vesterdal, L.; Allan, E. Tree diversity is key for promoting the diversity and abundance of forest-associated taxa in Europe. Oikos. 2020, 129, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FOREST EUROPE. The State of Europe’s Forests. 2020. Forest Europe Liason Unit. Bratislava. Slovakia.

- Ohse, B.; Compagnoni, A.; Farrior, C.E.; McMahon, S.M.; Salguero-Gómez, R.; Rüger, N.; Knight, T.M. Demographic synthesis for global tree species conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2023, 6, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, V.H.; Joyce, L.A.; McNulty, S.; Neilson, R.P.; Ayres, M.P.; Flannigan, M.D.; Hanson, P.J.; Irland, L.C.; Lugo, A.E.; Peterson, Ch.J.; Simberloff, D.; Swanson, F.J.; Stocks, B.J.; Wotton, B.M. Climate Change and Forest Disturbances: Climate change can affect forests by altering the frequency, intensity, duration, and timing of fire, drought, introduced species, insect and pathogen outbreaks, hurricanes, windstorms, ice storms, or landslides. Bioscience. 2001, 51, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palik, B.; Engstrom, R.T. Species composition. In: Hunter Jr, M.L. (ed.). Maintaining Biodiversity in Forest Ecosystems. 2004. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge. Pp. 65-94.

- Ellison, A.M.; Bank, M.S.; Clinton, B.D.; Colburn, E.A.; Elliott, K.; Ford, C.R.; Foster, D.R.; Kloeppel, B.D.; Knoepp, J.D.; (. ..), Webster, J.R. Loss of foundation species: consequences for the structure and dynamics of forested ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2005, 3, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonman, C.C.F.; Serra-Diaz, J.M.; Hoeks, S. Guo W.-Y.; Enquist B.J.; Maitner B.; Malhi Y.; Merow C.; Buitenwerf R.; Svenning J.-Ch. More than 17,000 tree species are at risk from rapid global change. Nat. Commun, 1038; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Faliński, J.B.; Mułenko, W. Cryptogamous plants in the forest communities of Białowieża National Park. Phytocoenosis 1996, 8, 75–110. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.; Butler, J.; Green, T. The value of different tree and shrub species to wildlife. Brit. Wildl. 2006, 1, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Senn-Irlet, B. Welches sind pilzreiche Holzarten? Wald und Holz 2008, 10, 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Faliński, J.B. Vegetation dynamics in temperate lowland primeval forests. Ecological studies in Białowieża Forest. Dr W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht/Boston/Lancaster. Geobotany.

- Okołów, Cz.; Karaś, M.; Bołbot, A. (Eds.) Białowieski Park Narodowy. Poznać. Zrozumieć. Zachować. 2009. Białowieski Park Narodowy. Białowieża.

- Faliński, J.B. Zielone grądy i czarne bory Białowieży. Część tekstowa. 1977. Instytut Wydawniczy Nasza Księgarnia. Warszawa.

- Faliński, J.B. Concise geobotanical atlas of Białowieża Forest. Phytocoenosis. Supplementum Cartographiae Geobotanicae. 1994, 6, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Gamfeldt, L.; Snäll, T.; Bagchi, R.; Jonsson, M.; Gustafsson, L.; Kjellander, P.; Ruiz-Jaen, M.C.; Fröberg, M.; Stendahl, J.; Philipson, C.D.; Mikusiński, G.; Andersson, E.; Westerlund, B.; Andrén, H.; Moberg, F.; Moen, J.; Bengtsson, J. Higher levels of multiple ecosystem services are found in forests with more tree species. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, C.R.; Lorimer, C.G. A demographic approach to evaluating tree population sustainability. Forests 2017, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Pommerening, A.; Miścicki, S.; Drozdowski, S.; Żybura, H. A common lack of demographic equilibrium among tree species in Białowieża National Park (NE Poland): evidence from long-term plots. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 27, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Drozdowski, S.; Bielak, K.; Czacharowski, M.; Zajączkowski, J.; Buraczyk, W.; Gawron, L. A demographic equilibrium approach to stocking control in mixed, multiaged stands in the Białowieża Forest, Northeast Poland. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2021, 481, 118694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, L.; Langvall, O.; Pommerening, A. Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) H. Karst.) selection forests at Siljansfors in Central Sweden. Trees, Forests and People, 0392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, W. Vegetation landscapes of Białowieża Forest. Phytocoenosis. Supplementum Cartographiae Geobotanicae. 1994, 6, 35–87. [Google Scholar]

- Więcko, E. Puszcza Białowieska. 1984. PWN. Warszawa.

- BULiGL. Forest management plans for Białowieża, Browsk and Hajnówka Forest Districts for years 2021-2030 (In Polish). 2021. BULiGL. Białystok.

- Salk, T.T.; Frelich, L.E.; Sugita, S.; Calcote, R.; Ferrari, J.B.; Montgomery, R.A. Poor recruitment is changing the structure and species composition of an old-growth hemlock-hardwood forest. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1998–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Liocourt, F. De l’amenagement des sapinieres. Bulletin trimestriel -, 1898. [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, C.G.; Frelich, L.E. A simulation of equilibrium diameter distributions of sugar maple (Acer saccharum). B. Torrey Bot. Club. 1984, 111, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Lian, J.; Li, B.; Ye, J.; Yao, X. Tree size distributions in an old-growth temperate forest. Oikos. 2009, 118, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, J.-P. Dynamique et conditions d’equilibre de peuplements jardin es sur les stations de la hêtraie a sapin. Schweiz. Z. Forstw. 1975, 126, 637–671. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, J.-P. Modelling the demographic sustainability of pure beech plenter forests in Eastern Germany. Ann. For. Sci. 2006, 63, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, D.A.; Duncan, R.P.; Allen, R.B.; Truscott, J. Disturbances prevent stem size-density distributions in natural forests from following scaling relationships. Ecol. Lett. 2003, 6, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohyama, T.S.; Potts, M.D.; Kohyama, T.I.; Rahman Kassim, A.; Ashton, P.S. Demographic properties shape tree size distribution in a Malaysian rain forest. Am. Nat. 2015, 185, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolibok, L.; Brzeziecki, B. An analysis of selected allometric relationships for main tree species of the Białowieża National Park (In Polish with English summary). Sylwan. 2000, 6, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Landau, H.C.; Condit, R.S.; Harms, K.E.; Marks, Ch.O.; Thomas, S.C.; Bunyavejchewin, S.; Chuyong, G.; Co, L.; Davies, S.; (. ..), Ashton, P. Comparing tropical forest tree size distributions with the predictions of metabolic ecology and equilibrium models. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, J.B.; Cain, M.D.; Guldin, J.M.; Murphy, P.A.; Shelton, M.G. Uneven-Aged Silviculture for the Loblolly and Shortleaf Pine Forest Cover Types. 1996. General Technical Report SO-118. USDA Forest Service. Southern Research Stadion. Asheville, NC. USA.

- Buongiorno, J.; Kolbe, A.; Vasievich, M. Economic and Ecological Effects of Diameter-Limit and BDq Management Regimes: Simulation Results for Northern Hardwoods. Silva Fenn. 2000, 34(3), 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancino, J.; von Gadow, K. Stem number guide curves for uneven-aged forests development and limitations. In: von Gadow, K.; Nagel J.; Saborowski, J. (eds.) Continuous Cover Forestry. 2002. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Pp.: 163-174.

- O’Hara, K.L.; Gersonde, R.F. Stocking control concepts in uneven-aged silviculture. Forestry. 2004, 2, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducey, M.J. The Reverse-J and Beyond: Developing Practical, Effective Marking Guides. In Proceedings of Implementing Uneven-Aged Management in New England: Is it practical? Fox Research and Demonstration Forest, Hillsborough, NH, USA, 13 April 2006; Caroline, A. Ed.: U.N.H. Cooperative Extension: Durham, NH, USA. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Drozdowski, S.; Bielak, K.; Gawron, L.; Buraczyk, W. Promoting diverse forest stand structure under lowland conditions (In Polish with English summary). Sylwan. 2013, 8, 597–606. [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara, K.L. Multiaged Silviculture. Managing for Complex Forest Stand Structures. 2014. Oxford. Oxford University Press.

- Paczoski, J. Lasy Białowieży. 1930. PROP. Poznań.

- Matuszkiewicz, W. Zespoły leśne Białowieskiego Parku Narodowego. Annales UMCS. Lublin – Polonia. Supplementum VI. Sectio C.

- Sokołowski, A. Lasy Puszczy Białowieskiej. 2004. CILP. Warszawa.

- Seastedt, T.R.; Hobbs, R.J.; Suding, K.N. Management of novel ecosystems: are novel approaches required? Front. Ecol. Environ. 2008, 10, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.; Neilson, R.P.; Lenihan, J.M.; Drapek, R.J. Global patterns in the vulnerability of ecosystems to vegetation shifts due to climate change. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 6, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, M.; Schaich, H.; Bürgi, M.; Konold, W. Climate change and nature conservation in Central European forests: A review of consequences, concepts and challenges. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanke, H.; Finley, A.O.; Domke, G.M.; Weed, A.S.; MacFarlane, D.W. Over half of western United States’ most abundant tree species in decline. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Dai, Z.; Fang, P.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L. A Review: Tree Species Classification Based on Remote Sensing Data and Classic Deep Learning-Based Methods. Forests. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.D.; Manion, P.D.; Faber-Langendoen, D. Diameter distributions and structural sustainability in forests. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2006, 222, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowiak, M.K.; Nagel, L.M.; Webster, C.R. Spatial scale and stand structure in northern hardwood forests: implications for quantifying diameter distributions. For. Sci. 2008, 54(5), 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, J.-Ph. Der Plenterwald. 2001. Parey Buchverlag. Berlin. Germany.

- Zajączkowski, J.; Brzeziecki, B.; Perzanowski, K.; Kozak, I. Impact of potential climate changes on competitive ability of main forest tree species in Poland (In Polish with English summary). Sylwan. 2013, 157(4), 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brang, P.; Spathelf, J.; Larsen, B.; Bauhus, J.; Bončìna, A.; Chauvin, Ch.; Drössler, L.; García-Güemes, C.; Heiri, C.; Kerr, G.; Lexer, M.J.; Mason, B.; Mohren, F.; Mühlethaler, U.; Nocentini, S.; Svoboda, M. Suitability of close-to-nature silviculture for adapting temperate European forests to climate change. Forestry. 2014, 87, 492–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borecki, T.; Brzeziecki, B. Silvicultural analysis of post-Century stands in the Białowieża Forest (In Polish with English summary). Sylwan. 2001, 7, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Pautasso, M.; Aas, G.; Queloz, V.; Holdenrieder, O. European ash (Fraxinus excelsior) dieback - A conservation biology challenge. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 158, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Zajączkowski, J.; Bolibok, L. Tree species and forest stands. In: Matuszkiewicz J.M.; Tabor J. (ed.). Inventory of selected natural and cultural elements of the Białowieża Forest (in Polish). 2023. Instytut Badawczy Leśnictwa. Sękocin Stary. Pp.: 159-391. [CrossRef]

- Temperli, C.; Veblen, T.T.; Hart, S.J.; Kulakowski, D.; Tepley, A.J. Interactions among spruce beetle disturbance, climate change and forest dynamics captured by a forest landscape model. Ecosphere. 2015, 6(11), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, M.B.; Roloff, G.J.; Henry, C.R.; Hartman, J.P.; Donovan, M.L.; Farinosi, E.J.; Starking, M.D. Rethinking Northern Hardwood Forest Management Paradigms with Silvicultural Systems Research: Research-Management Partnerships Ensure Relevance and Application. J. Forest. 1093; 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ngugi, M.R.; Neldner, V.J.; Dowling, R.M.; Li, J. Recruitment and demographic structure of floodplain tree species in the Queensland Murray-Darling basin, Australia. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2021, 1, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Keczyński, A.; Zajączkowski, J.; Drozdowski, S.; Gawron, L.; Buraczyk, W.; Bielak, K.; Szeligowski, H.; Dzwonkowski, M. Threatened tree species of the Białowieża National Park (the Strict Reserve) (In Polish with English summary). Sylwan. 2012, 4, 252–261. [Google Scholar]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Andrzejczyk, T.; Żybura, H. Natural regeneration of trees in the Białowieża Forest (In Polish with English summary). Sylwan. 2018, 11, 883–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuijper, D.P.J.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Brzeziecki, B.; Churski, M. ; Jędrzejewsk,i W.; Żybura, H. Fluctuating ungulate density shapes tree requirement in natural stands of the Białowieża Primeval Forest, Poland. J. Veg. Sci, 1082; 21. [Google Scholar]

- Kuijper, D.P.J.; Cromsigt, J.P.G.M.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Miścicki, S.; Churski, M.; Jędrzejewski, W.; Kweczlich, I. Bottom-up versus top-down control of tree regeneration in the Białowieża Primeval Forest, Poland. J. Ecol. 2010, 98(4), 888–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszkiewicz, J.M. Changes in the forest associations of Poland’s Białowieża Primeval Forest in the second half of the 20th century. Czas. Geogr. 2011, 82, 69–105. [Google Scholar]

- Akçakaya, H.R.; Sjögren-Gulve, P. Population viability analyses in conservation planning: an overview. Ecol. Bull. 2000, 48, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines on Closer-to-Nature Forest Management. 2023. Commission Staff Working Document. Brussels. 27.7.2023. SWD(2023) 284 final.

- Cole, D.N.; Yung, L. Beyond Naturalness: Rethinking Park and Wilderness Stewardship in an Era of Rapid Change. 1st edition. 2010. Island Press. Washington DC. US.

- Wapner, P. The changing nature of nature: environmental politics in the Anthropocene. Global Environ. Polit. 2014, 14, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeziecki, B.; Hilszczański, J.; Kowalski, T.; Łakomy, P.; Małek, S.; Miścicki, S.; Modrzyński, J.; Sowa, J.; Starzyk, J.R. Problem of a massive dying-off of Norway spruce in the ‘Białowieża Forests’ Forest Promotional Complex (In Polish with English Summary). Sylwan. 2018, 5, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DBH (cm) |

Tree species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | Birch | Aspen | Spruce | Oak | Hornbeam | Lime | Maple | Elm | Ash | Alder | Total | |

| 9 | 2.8 | 4.4 | 0.1 | 33.5 | 6.8 | 39.9 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 6.8 | 98.5 |

| 13 | 6.5 | 4.6 | 0.2 | 31.4 | 6.1 | 33.7 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 7.5 | 93.8 |

| 17 | 8.7 | 4.4 | 0.2 | 24.6 | 5.1 | 26.0 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 7.8 | 79.7 |

| 21 | 11.5 | 4.4 | 0.2 | 18.0 | 4.1 | 19.1 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 9.0 | 68.9 |

| 25 | 12.8 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 12.7 | 3.3 | 11.7 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 9.1 | 55.7 |

| 29 | 12.6 | 4.1 | 0.3 | 8.5 | 2.5 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 8.6 | 44.6 |

| 33 | 11.7 | 3.4 | 0.3 | 6.2 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 8.3 | 36.6 |

| 37 | 9.7 | 2.9 | 0.3 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 6.9 | 28.5 |

| 41 | 7.5 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 5.9 | 21.8 |

| 45 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 15.1 |

| 49 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.8 | 10.1 |

| 53 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 6.3 |

| 57 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 4.0 |

| 61 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 2.4 |

| 65 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| 69 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.8 |

| 73 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| 77 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.7 |

| Ntot | 97.2 | 36.5 | 4.3 | 146.3 | 38.5 | 145.6 | 15.8 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 80.3 | 570.7 |

| Btot | 7.9 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 5.4 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 6.0 | 30.1 |

| B% | 26.2 | 7.3 | 2.0 | 17.9 | 9.6 | 13.6 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 19.9 | 100.0 |

| Tree species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | Birch | Aspen | Spruce | Oak | Hornbeam | Lime | Maple | Elm | Ash | Alder | Total |

| 15.3 | 7.4 | 4.9 | 13.4 | 20.3 | 11.2 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 3.0 | 3.6 | 12.2 | 100.0 |

| Tree species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | Birch | Aspen | Spruce | Oak | Hornbeam | Lime | Maple | Elm | Ash | Alder | Total |

| 3.7 | 1.8 | 1.2 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 3.0 | 24.5 |

| DBH (cm) | Tree species | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | Birch | Aspen | Spruce | Oak | Hornbeam | Lime | Maple | Elm | Ash | Alder | Total | |

| 9 | 21.0 | 45.9 | 5.6 | 40.6 | 38.6 | 6.9 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 7.1 | 180.7 |

| 13 | 11.9 | 19.6 | 3.6 | 20.6 | 18.1 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 5.5 | 94.4 |

| 17 | 7.9 | 9.9 | 2.6 | 12.2 | 10.6 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 4.4 | 59.0 |

| 21 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 3.9 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 3.7 | 41.2 |

| 25 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 1.6 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 30.9 |

| 29 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 24.3 |

| 33 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 19.8 |

| 37 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.5 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 16.5 |

| 41 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 13.9 |

| 45 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 11.8 |

| 49 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 10.0 |

| 53 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.3 | 8.5 |

| 57 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 7.1 |

| 61 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 6.0 |

| 65 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 5.0 |

| Nmod | 71.5 | 90.5 | 21.9 | 102.3 | 103.1 | 40.4 | 13.0 | 16.2 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 40.2 | 529.1 |

| Tree species | Area of growing space for a tree with DBH = 9 cm (GS, in m2)* | Average number of deficit trees in the smallest diameter class (midpoint = 9 cm) (DEF, in trees ∙ ha-1) |

Estimated area of regeneration spots (RS, in ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | 8.13 | 18.14 | 1.64 |

| Birch | 12.55 | 41.45 | 5.91 |

| Aspen | 12.55 | 5.46 | 0.78 |

| Spruce | 10.82 | 9.21 | 1.14 |

| Oak | 6.14 | 31.88 | 2.24 |

| Hornbeam | 25.24 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Lime | 15.98 | 0.58 | 0.11 |

| Maple | 13.29 | 3.92 | 0.60 |

| Elm | 23.10 | 3.30 | 0.87 |

| Ash | 10.75 | 3.82 | 0.47 |

| Alder | 10.14 | 1.06 | 0.12 |

| Total | 118.83 | 13.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).