Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions

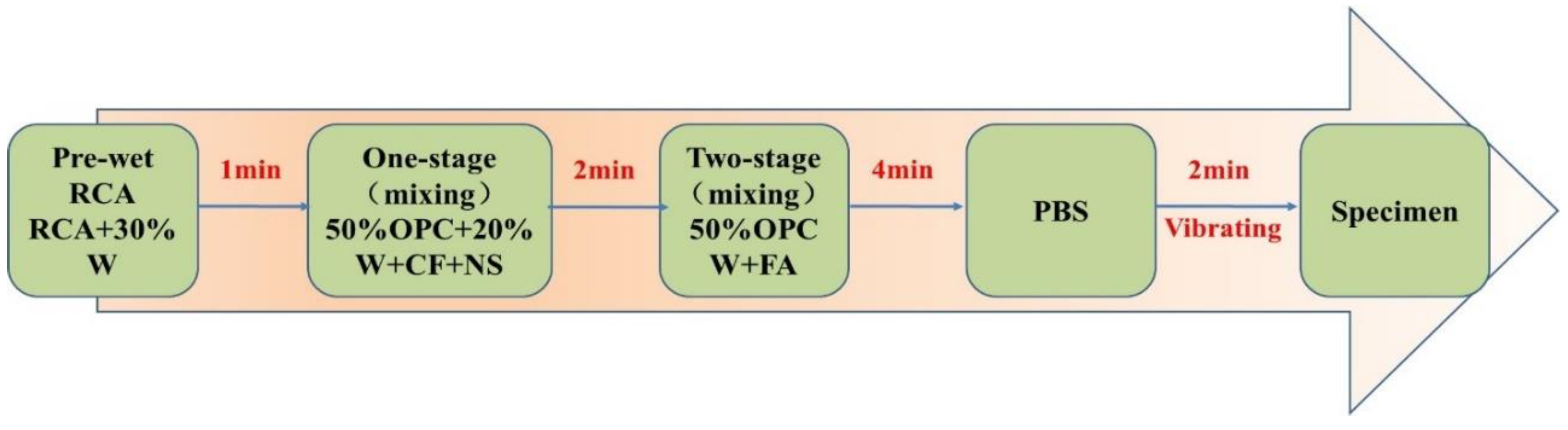

2.3. Specimen Preparation

2.4. Testing Methods

2.4.1. Mechanical Properties

2.4.2. Microscopic Testing

3. Results and Discussion

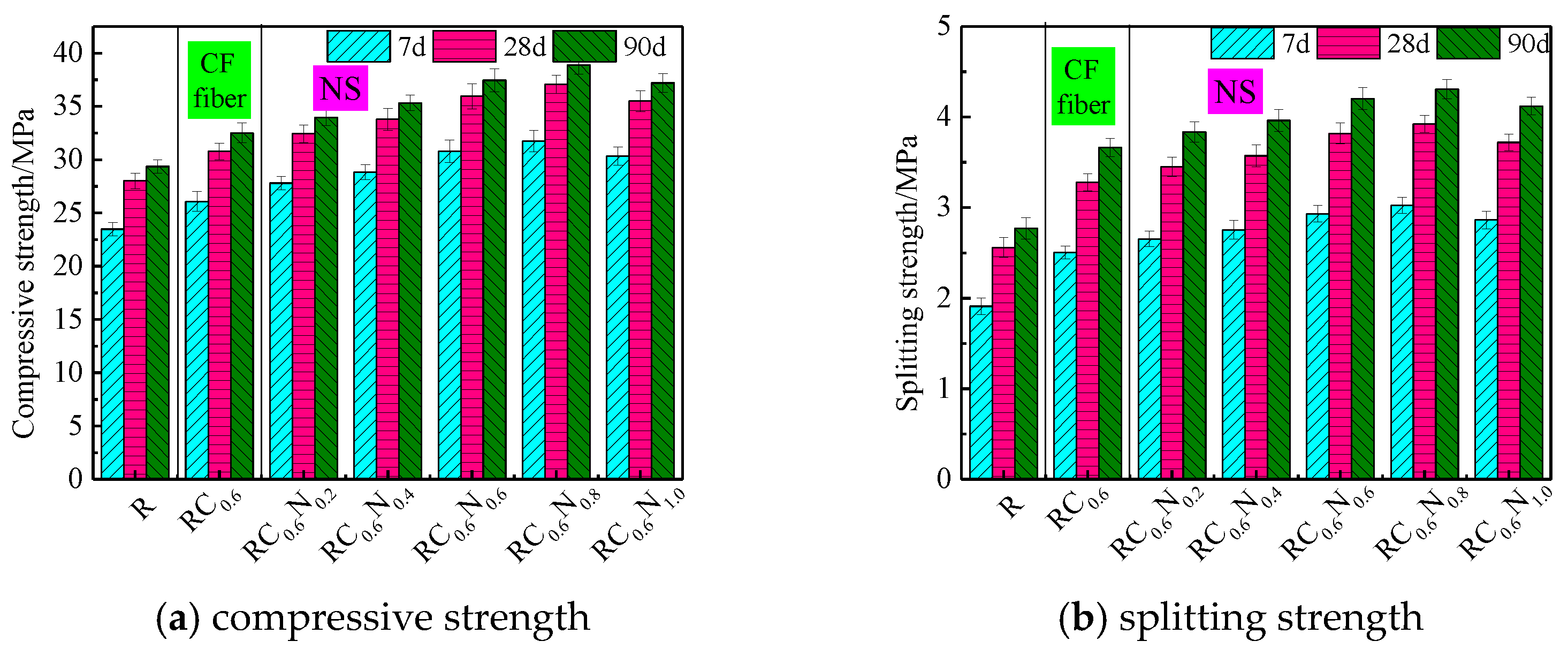

3.1. Effect of CF and NS on Mechanical Properties of RAC

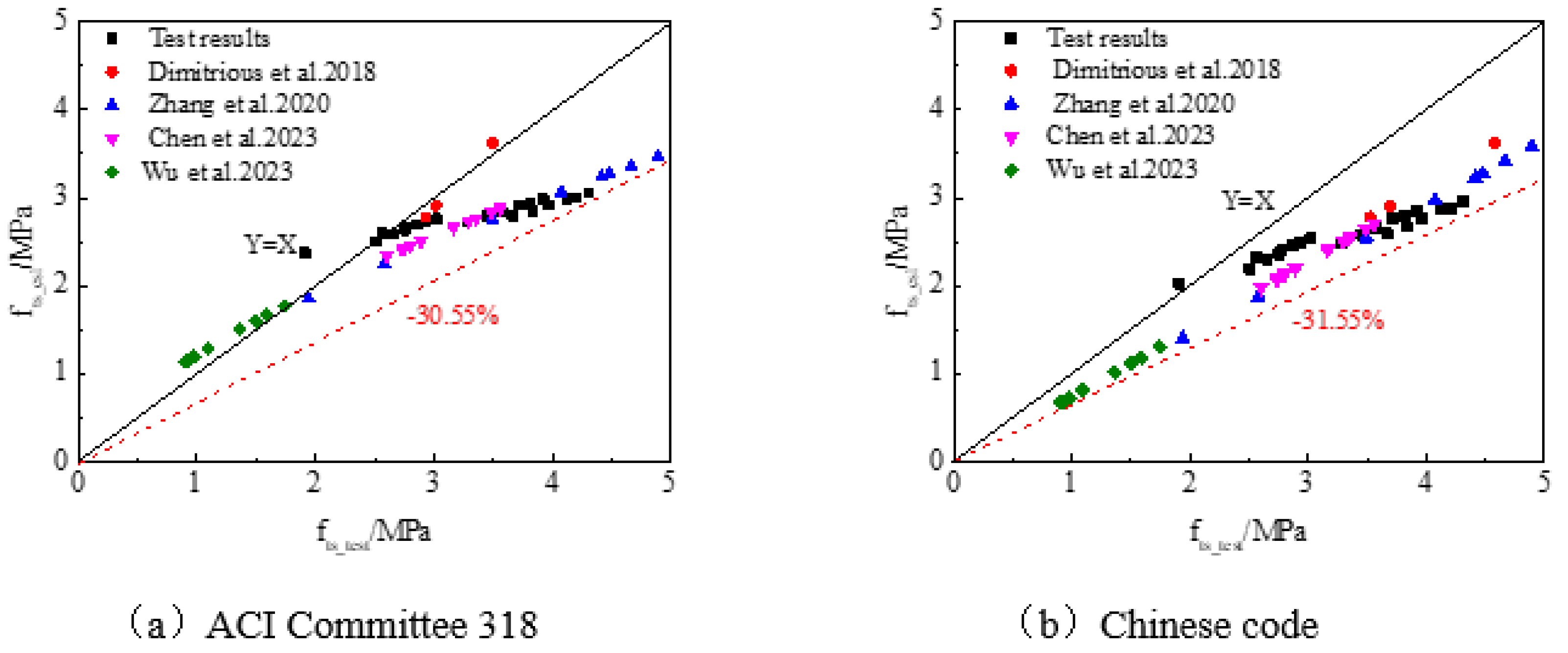

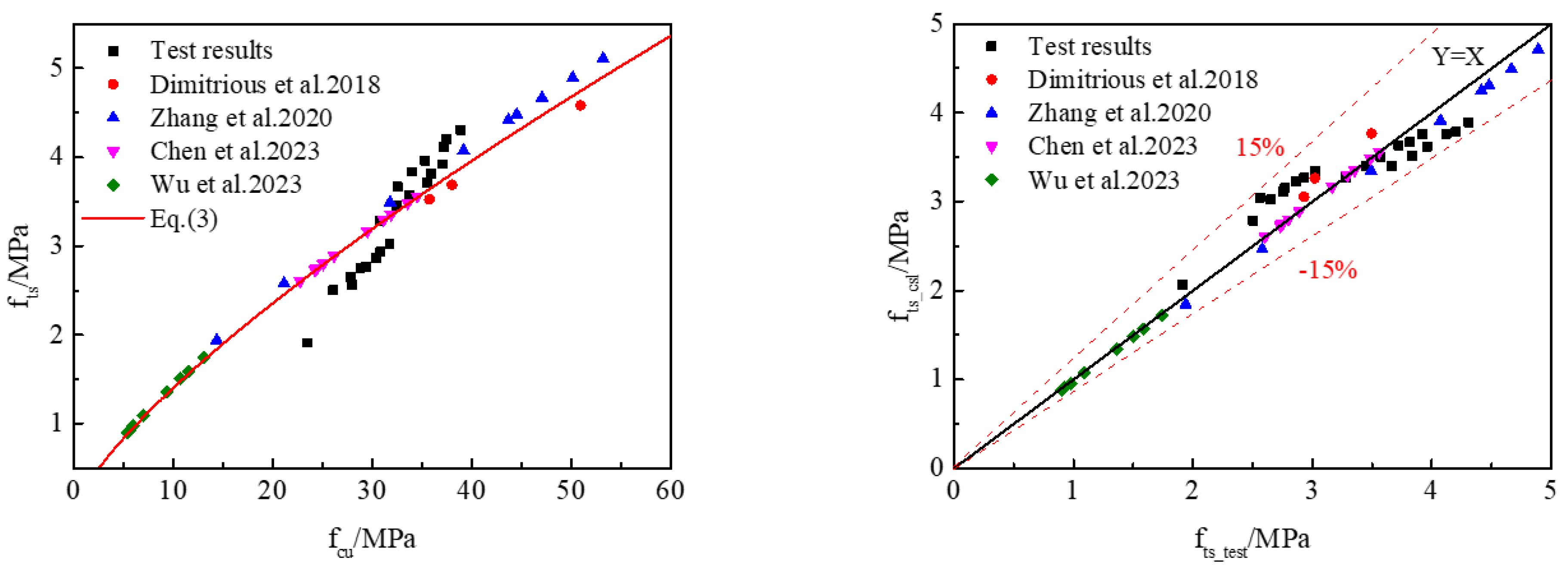

3.2. The Relationship Between Compressive Strength and Splitting Tensile Strength of RAC

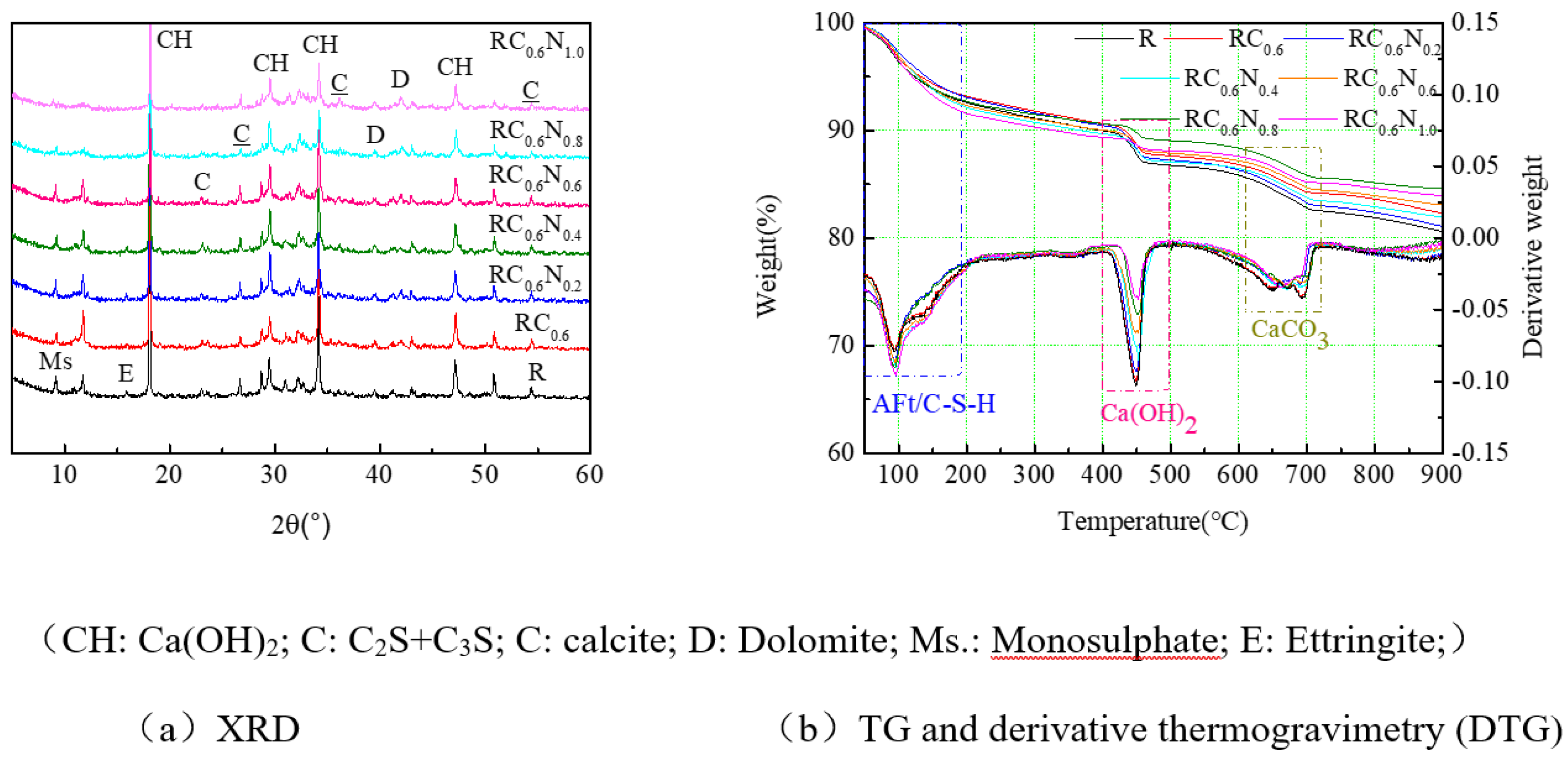

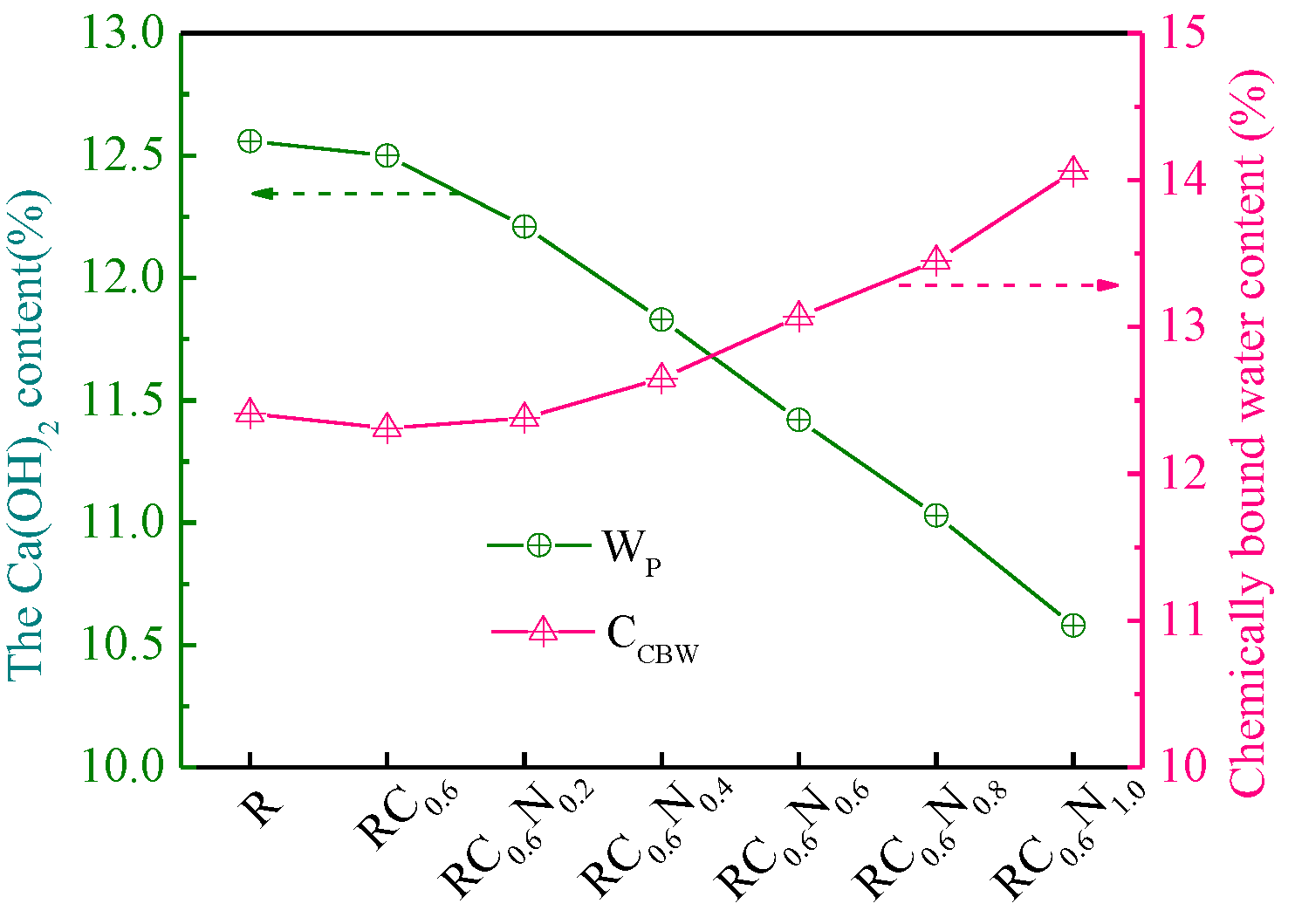

3.3. Effect of CF/NS on Hydration Products of Cement

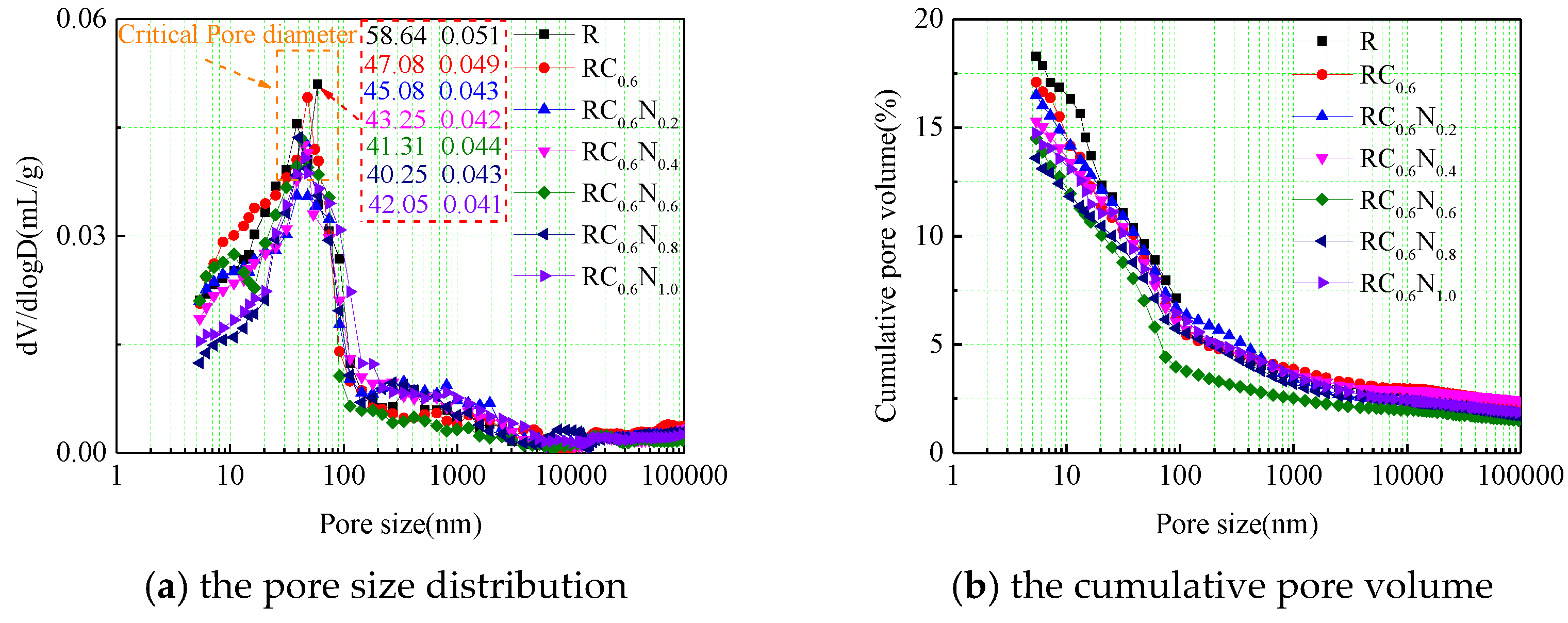

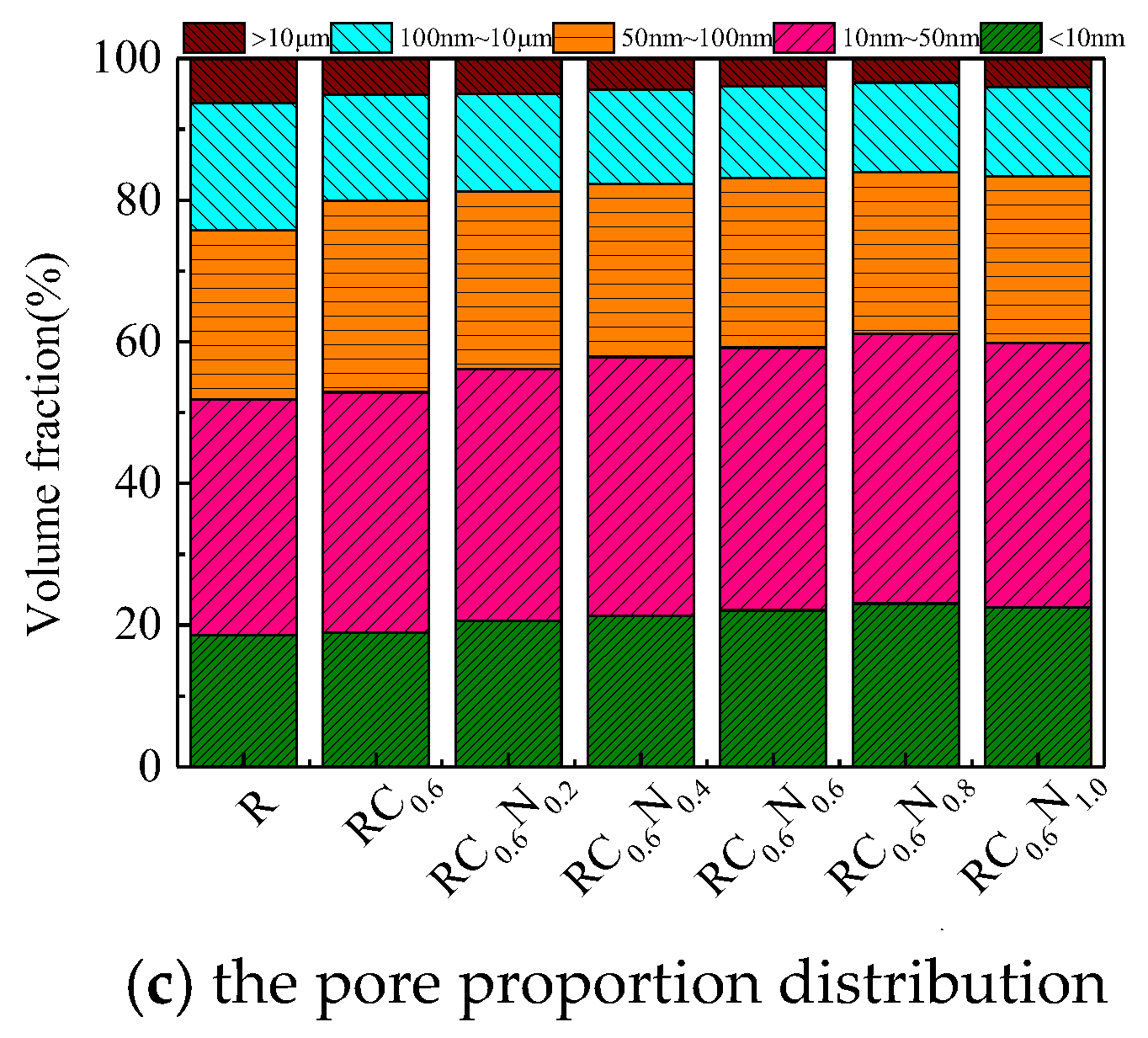

3.4. Effect of CF Fibers/NS on Pore Structures of RAC Samples

3.5. Microstructure Analysis

3.6. Action Mechanism of CF and NS

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akhtar, A.; Sarmah, A.K. Construction and demolition waste generation and properties of recycled aggregate concrete: A global perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.-B.; Bui, Q.-B. Recycled aggregate concretes – A state-of-the-art from the microstructure to the structural performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 257, 119522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, P.; Garcia-Troncoso, N.; Mo, K.H.; Ling, T.-C. Roles of enhanced ITZ in improving the mechanical properties of concrete prepared with different types of recycled aggregates. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Chong, L.; Xie, Z. Performance enhancement of recycled concrete aggregate – A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, P.; Ding, X.; Xue, S.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, T. Influence of the incorporation of recycled coarse aggregate on water absorption and chloride penetration into concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 239, 117845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yan, L.; Fu, Q.; Kasal, B. A Comprehensive Review on Recycled Aggregate and Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolan, T.L.P.; Borges, P.M.; Silvestro, L.; da Silva, S.R.; Possan, E.; Andrade, J.J.d.O. Durability of concrete incorporating recycled coarse aggregates: carbonation and service life prediction under chloride-induced corrosion. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Pham, P.N.; Liu, C.; Zhuge, Y. The synergistic effects of fibres on mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete: A comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wen, T.; Tian, L. Size effects in compressive and splitting tensile strengths of polypropylene fiber recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stynoski, P.; Mondal, P.; Marsh, C. Effects of silica additives on fracture properties of carbon nanotube and carbon fiber reinforced Portland cement mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, W.; Geng-Sheng, J.; Bing-Liang, L.; Lei, P.; Ying, F.; Ni, G.; Ke-Zhi, L. Dispersion of carbon fibers and conductivity of carbon fiber-reinforced cement-based composites. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 15122–15132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Niu, D. Insight into dynamic compressive response of carbon nanotube/carbon fiber-reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhuang, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y. Mechanical properties of carbon fiber reinforced concrete (CFRC) after exposure to high temperatures. Compos. Struct. 2020, 256, 113072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, K.-Z.; Li, H.-J.; Jiao, G.-S.; Lu, J.; Hou, D.-S. Effect of carbon fiber dispersion on the mechanical properties of carbon fiber-reinforced cement-based composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 487, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ma, G.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y. Flexural behavior of carbon fiber-reinforced concrete beams under impact loading. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Luo, Y.; Yu, X.T.; Wang, L.J.; Wong, W.S. Experimental study on mechanical properties and microstructure of carbon fiber reinforced nano metakaolin recycled concrete. China Measurement & Test 2023, 1–9. (in chinese).

- Fu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Niu, D. Effects of nanosilica on microstructure and durability of cement-based materials. Powder Technol. 2022, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q.F.A. B, Z.Z. A, X.Z. A, W.X. A, D.N.A. B, Effect of nano calcium carbonate on hydration characteristics and microstructure of cement-based materials: A review.

- Zaidi, S.A.; Khan, M.A.; Naqvi, T. A review on the properties of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) modified with nano-silica. Mater. Today: Proc. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.C.; Lv, Y.; He, H.C.; Zhou, Y. , Effect of Nano-silica on mechanical properties and hydration of foamed concrete in the cement-fly ash system. Bulletin of the chinese ceramic society 2019, 38, 1390–1394. (in chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ghafari, E.; Costa, H.; Júlio, E.; Portugal, A.; Durães, L. The effect of nanosilica addition on flowability, strength and transport properties of ultra high performance concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 59, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Zhou, B.; Xiao, J. , Pore structure and chloride diffusivity of recycled aggregate concrete with nano-SiO2 and nano-TiO2. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 150, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivasankaran, U.; Raman, S.; Nallusamy, S. Experimental Analysis of Mechanical Properties on Concrete with Nano Silica Additive. J. Nano Res. 2019, 57, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.H.; Guo, X.N.; Han, R.C. Effect of nano-SiO2 and polypropylene fibers on the mechanical properties and microscopic properties of all coal gangue aggregate concrete. Acta Materiae Compositae Sinica 2024, 41, 1402–1419. (in chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Niu, D.; Su, L.; Luo, Y.; Huang, D.; Luo, D. Experimental study on mechanical properties and durability of basalt fiber reinforced coral aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 237, 117628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Wang, S.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Li, B.; Zhou, Y. Mechanical properties and pore structure of recycled aggregate concrete made with iron ore tailings and polypropylene fibers. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ai, Y.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, S.; Wei, Y.; Xu, X.; Fan, T. Potential use of nano calcium carbonate in polypropylene fiber reinforced recycled aggregate concrete: Microstructures and properties evaluation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yu, N.; Li, Y. Methods for improving the microstructure of recycled concrete aggregate: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, J.P.; Maso, J.C.; Bourdette, B. , Interfacial transition zone in concrete. Advanced Cement Based Materials 1995, 2, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Shi, C.; Guan, X.; Zhu, J.; Ding, Y.; Ling, T.-C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. Durability of recycled aggregate concrete – A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 89, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Xu, W.; Bu, M.; Guo, B.; Niu, D. Effect and action mechanism of fibers on mechanical behavior of hybrid basalt-polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete. Structures 2021, 34, 3596–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.W.; Kong, X.Q.; Gao, H.D.; Liu, H.X. Research on the mechanical properties and microstructure of recycled aggregate concrete with high content polypropylene fiber. Concrete.

- Bagherzadeh, R.; Sadeghi, A.-H.; Latifi, M. Utilizing polypropylene fibers to improve physical and mechanical properties of concrete. Text. Res. J. 2011, 82, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.W.; Ali, A.A.M.; Zidan, R.S. Properties of high strength polypropylene fiber concrete containing recycled aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 118010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, F.Z.; Shahjalal; Islam, K.; Tiznobaik, M.; Alam, M.S. Mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete containing crumb rubber and polypropylene fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 225, 983–996. [CrossRef]

- Erdem, S.; Hanbay, S.; Güler, Z. Micromechanical damage analysis and engineering performance of concrete with colloidal nano-silica and demolished concrete aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xing, F.; Gong, G.; Hu, B.; Guo, M. , An industrial applicable method to improve the properties of recycled aggregate concrete by incorporating nano-silica and micro-CaCO3. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 259, 120920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. X., W. G., Fourie, Compressive behaviour of fibre-reinforced cemented paste backfill.

| Compositions | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 | SiO2 | LOI | Compressive strength/MPa | Flexural strength/MPa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | 18.80 | 5.15 | 3.345 | 57.83 | 0.916 | 3.95 | 18.80 | 3.95 | 3d | 28d | 3d | 28d |

| Fly ash | 50.96 | 29.38 | 4.21 | 6.58 | 1.13 | 0.481 | 50.96 | 2.79 | 26.5 | 45.3 | 5.6 | 7.8 |

| Mixture | C | FA | W | S | CA | PBS | CF | NS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 |

| RC0.6 | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 2.28(0.6wt%) | 0 |

| RC0.6N0.2 | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 2.28(0.6wt%) | 0.76(0.2wt%) |

| RC0.6N0.4 | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 2.28(0.6wt%) | 1.52(0.4wt%) |

| RC0.6N0.6 | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 2.28(0.6wt%) | 2.28(0.6wt%) |

| RC0.6N0.8 | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 2.28(0.6wt%) | 3.04(0.8wt%) |

| RC0.6N1.0 | 380 | 120 | 237 | 720 | 900 | 3.8 | 2.28(0.6wt%) | 3.8(1.0wt%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).