1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a result of a physical assault to the brain and is a major cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in developed countries. In addition, the prevalence of TBI has risen dramatically in recent years due to terrorism, wars and armed conflicts worldwide. It has been estimated that TBI results in a global economic burden of approximately $US400 billion yearly spent on TBI-related medical care, hospitalization, and rehabilitation (Maas et al., 2017). The frequency of TBI is highest among children and young adults due to accidents, violence and sports, and it is more frequent in males than females (Daugherty et al., 2019). Impact of TBI arises from the mechanical stress caused by a primary injury, followed by progressive damage of the brain parenchyma through secondary injury mechanisms. Multiple biochemical cascades are triggered by brain damage, resulting in ROS production alongside blood loss and hypoxia (Pun et al., 2011). A number of intricate pathophysiological processes, including the release of cytokines, activation of chemoreceptors, neuroinflammation, cell injury and death, can be triggered in TBI. It also causes oxidative stress and various cerebrovascular dysfunctions which often result in substantial impairment of cerebral blood flow autoregulation (Gardner and Zafonte, 2016).In a blast, the explosion can induce TBI by a direct pressure wave to the skull or through excessive pressure in the vascular system (Kabu et al., 2015; Meabon et al., 2016; Phipps et al., 2020). These mechanisms potentially induce the brain to enter a phase of rapid acceleration-deceleration and rotation, often seen in whiplash, resulting in widespread axonal damage and neuronal death. In particular, blast TBI has devastating effects on the brain’s vasculature and triggers intra-cranial hypertension and edema. In the aftermath of a blast exposure, brain damage symptoms are characterized by cerebrovascular injury, inflammation, neuronal death and synaptic loss. Depending on the site and severity of brain injury TBI can cause long-lasting cognitive-behavioral symptoms such as memory deficits, executive function impairment, confusion, decrease in consciousness, dizziness, concentration difficulties, slurred speech, compromised motor functions, and emotional disturbance as well as neurological symptoms such as epilepsy (Georges and Booker, 2017; Girgis et al., 2016; Schimmel et al., 2017). TBI can also lead to long-term complications which may encompass reduction of life expectancy, neurotrauma, seizure disorders, psychiatric disorders, and onset of neurodegenerative diseases (Lu et al., 2012; Bramlett and Dietrich, 2015; Gardner et al., 2015; Graham and Sharp, 2019). In addition to the blast, combustion smoke exposure on the retina may cause increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, aquaporin 4, nitric oxide synthases, and enhanced vascular permeability (Zou et al., 2009) causing glaucomatous injury (Xue et al., 2006a; Xue et al., 2006b).

Since the primary injury can only be managed through prevention, treatment for TBI has until recently been focused on the alleviation of secondary injuries by targeting the mechanisms of oxidative damage either by inhibiting lipid peroxidation or through enzymatic scavenging of superoxide radicals (Lu et al., 2003; Di Pietro et al., 2020). Antioxidants are ideal therapeutic agents to mitigate TBI pathologies due to their biocompatibility and effectiveness in scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the prevention of oxidative damage (Kumar et al., 2020). However, current therapies based on the above strategy have failed to show satisfactory efficacy in clinical trials due to their reduced BBB permeability, hydrophobicity, short half-life, and poor bioavailability in the brain (Forman and Zhang, 2021). On the other hand, hydrophilic carbon clusters may be used as therapeutic, high-capacity antioxidants. (Samuel et al., 2014) As a novel antioxidant therapeutic possibility for TBI, nanoparticles have become more widely used in recent years (Kumar et al., 2020; Takahashi et al., 2020). Nanoparticles can enhance the delivery of antioxidants by improving their efficacy and blood brain barrier permeability, prolonging their half-life, and enhancing their targeting specificity (Bony and Kievit, 2019; Padmanabhan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

Our labs developed a biologically compatible class of oxidized carbon nanoparticles, poly-ethylene-glycol-functionalized hydrophilic carbon clusters (PEG-HCCs), as prospective neuroprotective agents for TBI (Marcano et al., 2013). However, functional and structural improvement is observed when treated with a catalytic carbon nano-antioxidant in experimental TBI complicated by hypotension and resuscitation (Mendoza et al., 2019). These particles were initially thought to act solely as high capacity catalytic superoxide dismutase mimetics (Samuel et al, 2015), but more recently were discovered to have more general enzymatic activities including the ability to span the electron transfer complexes in mitochondria (Derry et al, 2019) and oxidize hydrogen sulfide to protective polysulfides (Derry et al., 2024), all actions that would favor neuroprotection, demonstrated in both in vitro and in vivo models. Furthermore, PEG itself has the ability to restore the integrity of cell membranes (Shi, 2013), but accounts for less than 10% of the superoxide actions of the PEG-HCCs (Samuel et al, 2015a; Samuel et al., 2015b). Moreover, carbon particles improve cerebro-vascular dysfunction post TBI given their antioxidant nature (Bitner et al., 2012). These multiple catalytic features are consistent with PEG-HCCs acting as redox mediators, also termed nanozymes (Derry et al., 2019).

Based on an in vitro study, PEG-HCCs efficiently reduce intracellular oxidative stress and improve brain endothelial cell viability (Bitner et al., 2013). Moreover, antioxidant carbon particles are known to improve cerebrovacular dysfunction following TBI (Bitner et al., 2012). In an acute TBI model, PEG-HCCs were notably effective in TBI complicated by hypotension, a common co-morbid condition associated with head trauma (Mendoza et al., 2019).

Keeping the aforesaid PEG-HCC concerns in mind, we have used an open blast rat TBI model in a real time battle scenario to investigate the neuroprotective efficacy of a sub-class of PEG-HCCs.

2. Material and Methods

Preparation of PEG-HCC Nanoparticles

The PEG-HCC, developed by Tour, Kent and colleagues (Jacob et al. 2010., Bitner et al., 2012; Marcano et al., 2013; Sahni et al, 2013; Samuel et al, 2014) and used in the present experiment was prepared 3-5 days prior to the experiments at the Department of Chemistry, Rice University, as previously described and characterized (Tour et al., 2017) and it was transferred to the experimental site in Singapore by courier post immediately after its preparation. Prior work indicates that these particles are stable at ambient temperatures.

Animals

Thirty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing 320-350g each, 3 months of age, were used for the study. 28 animals were exposed to open blast (16 PEG and 12 SALINE group animals) and 6 animals, not exposed to the blast and not exposed to treatment, served as controls (CONTROL group). 16 rats were intraperitoneally (IP) injected with PEG-HCC dissolved in saline (PEG group, dosage: see below), whereas the other 12 animals were injected with pure saline as a vehicle control (SALINE group). Half of the animals in each group (PEG eight animals and SALINE six animals) were sacrificed on Day 3 after the blast, whereas the other half of the animals were sacrificed on Day 14 for collection of brains.

All handling and care of animals in this study adhered to the guidelines stipulated by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (IACUC) of the Defence Science Organisation National Laboratories (project approval number: DSO/IACUC/13-141), and of the Singapore Experimental Medical Centre (project approval number: 2013/SHS/0862). Measures were taken to minimize the number of rats used and their suffering, as per the principles of the 3R’s.

Blast Exposure

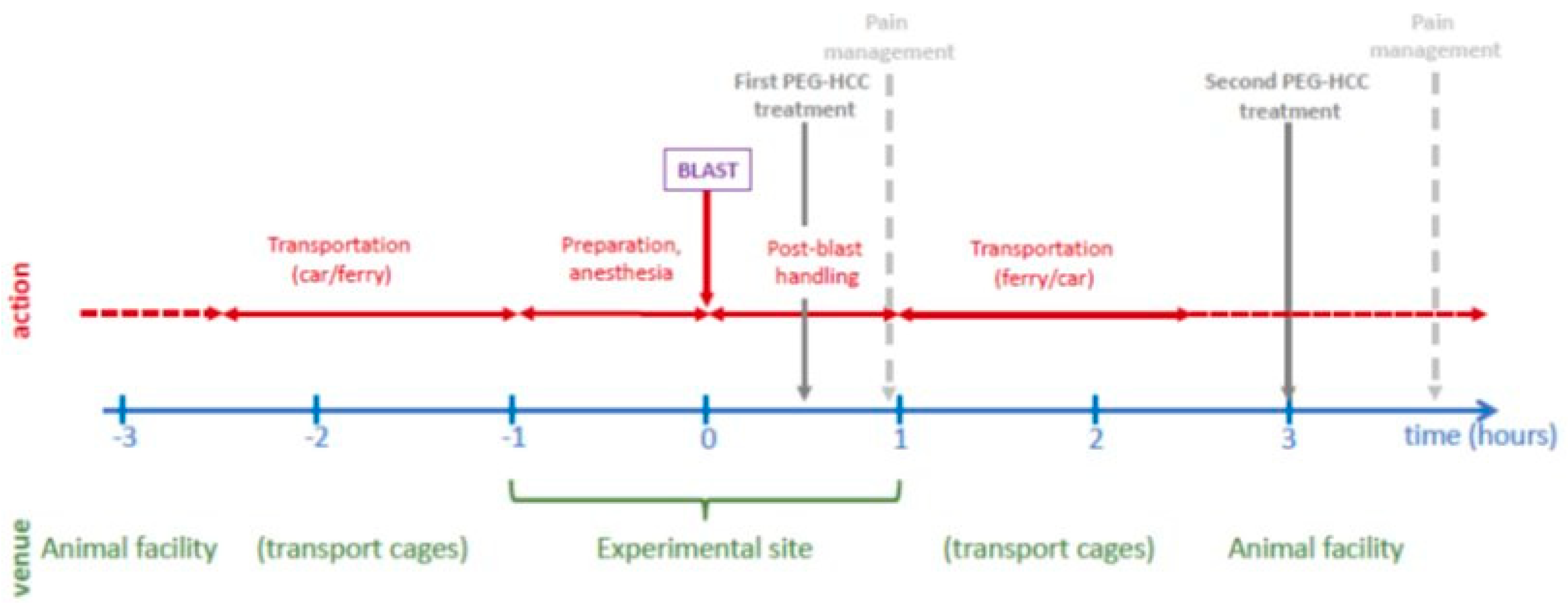

The blast experiments were performed in an experimental site dedicated to open blast explosions. The animals were transported from their housing facility to the site and back via land and sea transport; the temporal sequence of the events on the experimental day are shown in

Figure 1. Blast was carried out offshore in an isolated experimental military site. A total of 120 kg of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) with a penta-erythritol tetra-nitrate (PETN) booster was detonated at a height of 1 m. Three metal cages were set up at a distance of 15-17 meters and at a height of 1, 2 and 3 meter(s), respectively, from the blast source with a pressure transducer adjacent to each cage (Pun et al., 2011). In the blasts the peak blast overpressure values in the cages were between 13.0 psi (89.6 kPa) and 75.2 psi (518.5 kPa) (average: 23.9±16.2 psi or 164.8±11.7 kPa) and the impulse ranged between 46.3 psi/msec and 116.9 psi/msec (average: 68.3±19.0 psi/msec). Anesthesia was induced immediately before transportation to the blast site.

Under continuing anesthesia (Ketamine (150 mg/kg) and Xylazine (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally), rats were subjected to explosive blast overpressure after being secured to the custom-made wire caging with Velcro. The anesthetized animals were placed in such a way that their head was facing the direction of the blast pressure. Body armor was placed on the animals to protect them from the shock waves. The ears of the animals were taped down with surgical micropore tape to prevent direct blast pressure to the tympanic membrane. In addition, aqueous gel was spread on the whiskers, eye and face region and any parts of the body which were exposed to the air to prevent any instances of burn injury. When all the animals were in position, the blast protocol proceeded. Following the blast exposure, the animals were immediately removed from the cage and assessed for any gross or penetrating facial and body injuries. The animals were returned to their individual home cages approximately 90 min after the blast exposure. Animals were allowed to recover from anesthesia and the physiological conditions of animals regarding any weight loss, distress, pain, or suffering were monitored continuously after injury.

Treatment Protocol and Immediate Post-Blast Management

Animals received the first dose of the PEG-HCC treatment (2 mg/kg body weight) 30-40 minutes after the blast (i.e. within the “golden hour” of human trauma (Lerner et al., 2001; Clarke et al., 2002)) at the experimental site and received the second dose (2 mg/kg body weight) 150 minutes after the first dose (i.e. 3 hours after the blast) in their “home environment” (the animal house). Sterile physiological saline solution or drug (2 mg/kg of body weight) was injected in 0.5 ml volume IP. While intravenous (IV) injection provides a more rapidly available therapy, IP injection was selected given the difficulties in maintaining IV in the field, thus may be more realistic should a mass casualty event occur. Note that IP PEG-HCC injection has a slow uptake that peaks around 36 hours (Huq et al, 2016). Carprofen (4 mg/kg) was provided subcutaneously for pain management during drug treatment at 90 minutes post-injury. During the whole process the animal was maintained under anesthesia until transport back to home cage. All animals survived the blast and transport.

Chronic Post Blast Management

After animal recovery, the rats were monitored for their physical activities. The animals were allowed free access to food and water. For the first 2 days post-blast, the individually numbered animals in the CONTROL and PEG groups were monitored closely for their behavior and food intake. The animals were regularly weighed and recorded for their weight loss/gain. No animals showed any sign of severe illness or stress that required further treatment or euthanasia. On the third day, half of the animals were sacrificed, and their brains were harvested. On the fourteenth day the remaining animals were sacrificed, and their brains were harvested.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry (IHC) exploration of the effects of the open blast explosion and the therapeutic effects of PEG-HCC on brain tissue, six antibodies were selected with a dilution of 1:1000, focusing on various biochemical-cellular outcome measures critically important for the interpretation of the efficacy of PEG-HCC on the post-blast tissue damage: (1) neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (Provider: Abcam, Host: Rabbit), measuring neuronal death (Gundersen et al., 1987; West et al., 1991); (2) inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) (Provider: Abcam, Host: Rabbit), measuring nitric oxide (NO) production via nitric oxide synthase (NOS) up- or downregulation (Kaur et al., 1999); (3) 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase (CNPase) (Provider: BioLegend, Host: Mouse), measuring myelin integrity (Gravel et al., 1996); (4) ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) (Provider: Abcam, Host: Goat), an indicator of microglia activation (Zheng et al., 2022) (5) glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) (Provider: Genetex, Host: Rabbit), measuring levels of neuroinflammation (Middeldorp and Hol, 2011); (6) rat endothelial cell antigen 1 (RECA-1) (Provider: Thermo, Host: Mouse), a cell surface antigen which is expressed by all rat endothelial cells and indicates endothelial loss or reconstruction (Eng et al., 2000; Cattin et al., 2015).

From the euthanized animals on Day 3, the brains of eight (8) “PEG animals” and six (6) “SALINE animals” were used for IHC studies, and similarly, from the animals euthanized on Day 14, eight (8) “PEG animals” and six (6) “SALINE animals” were used for IHC studies. The six CONTROL animals were euthanized under identical conditions and their brains were harvested in an identical manner. The statistical analysis is based on the number of animals used in this study.

Brains were preserved by flash freezing. Frozen brains were sectioned at 14 μm thickness and subjected to a TBS-Triton (TBST) wash. For immunofluorescence experiments, sections were incubated with 3% BSA for 30 minutes to block nonspecific binding before incubation with the primary antibody (NeuN, RECA-1, iNOS, CNPase, Iba1 and GFAP, respectively) overnight at 4

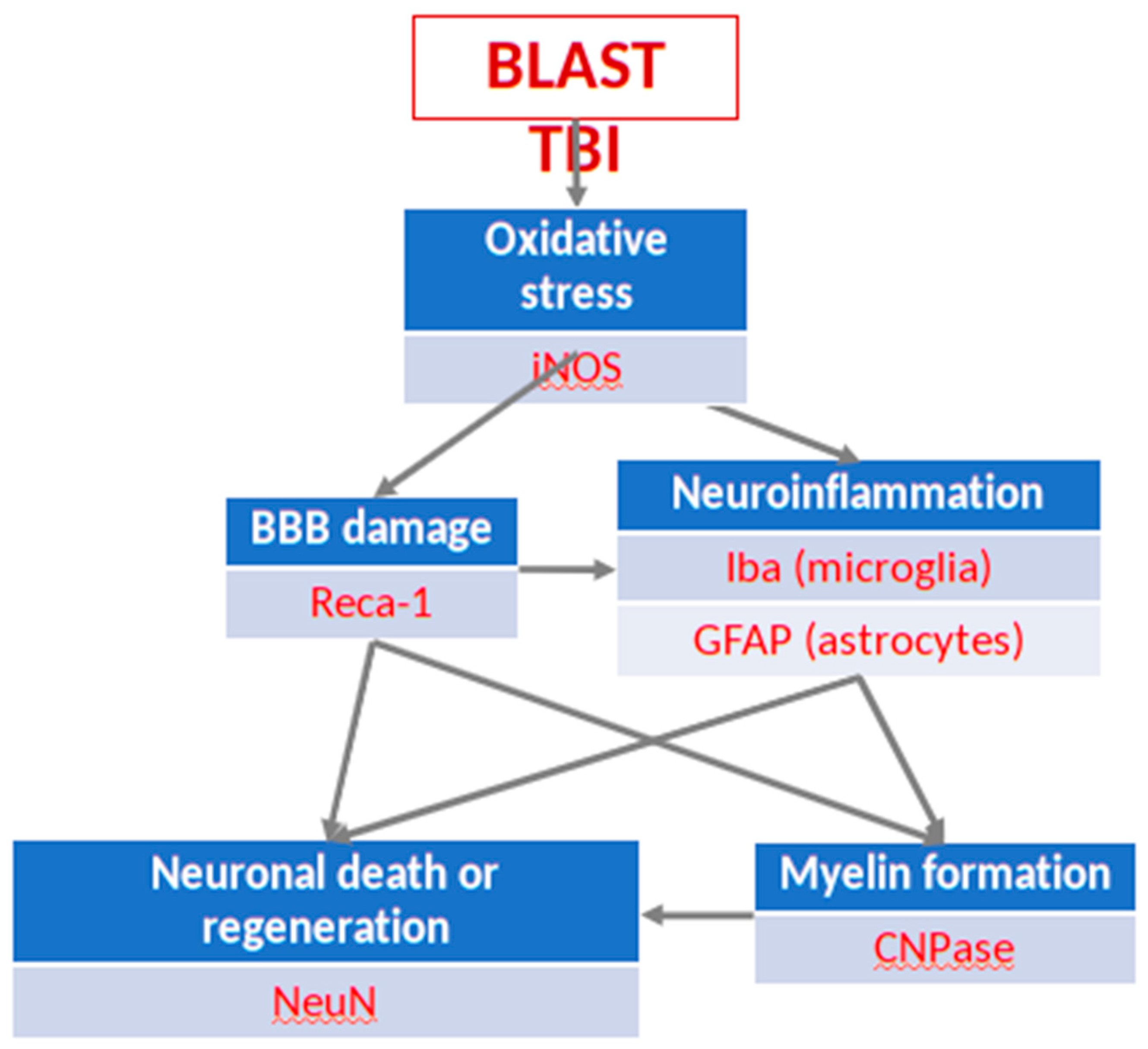

oC. Slides were washed with TBST before incubation with species specific fluorescent secondary antibodies for 1 hour at room temperature, washed with TBST, counter stained with DAPI and mounted with Vectashield anti-fade mounting medium. The selection of primary antibodies followed the selection of the outcome measures which we aimed to explore and interpret in detail, whereby the selected outcome measures represent landmark events in the pathophysiological processes following a TBI impact on brain tissue (

Figure 2). For the experiments, cortical samples were taken from the frontal, parietal and temporal lobes, however, in the case of NeuN IHC samples were also taken from the hippocampus and the dentate gyrus.

Image Analysis, Statistical Analysis and Data Presentation

Slides were imaged with the ZEISS LSM-800 Microscope and fluorescent positive cells were quantified with Image-J software (NIH). The statistical analysis is based on the above number of animals. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-way ANOVA Test. All data are presented as mean ± SD. A p-value of less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant for all comparisons. During the image analysis procedure, the area of labelled cells or compartments within the whole field of view (1 x 1mm square) was measured and expressed as a proportion of the total number of cells within the whole field. For each experiment the value obtained in the control conditions was regarded as 100%, whereas all other values were normalized to it. Thus, in the Figures the averaged data are expressed in relative terms (in %) (the colored columns) and the relevant SD values are indicated by “empty boxes” on top of the colored columns. The frames in Figures 3–10 show representative areas from within each of the respective 1 x 1 mm fields of view.

3. Results

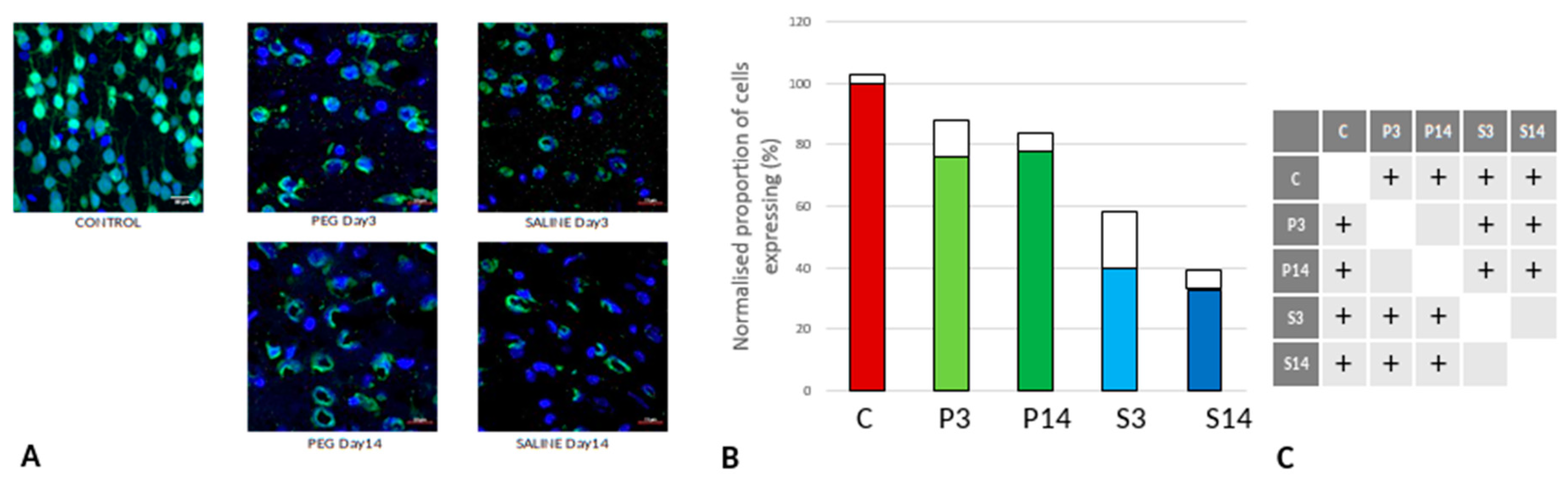

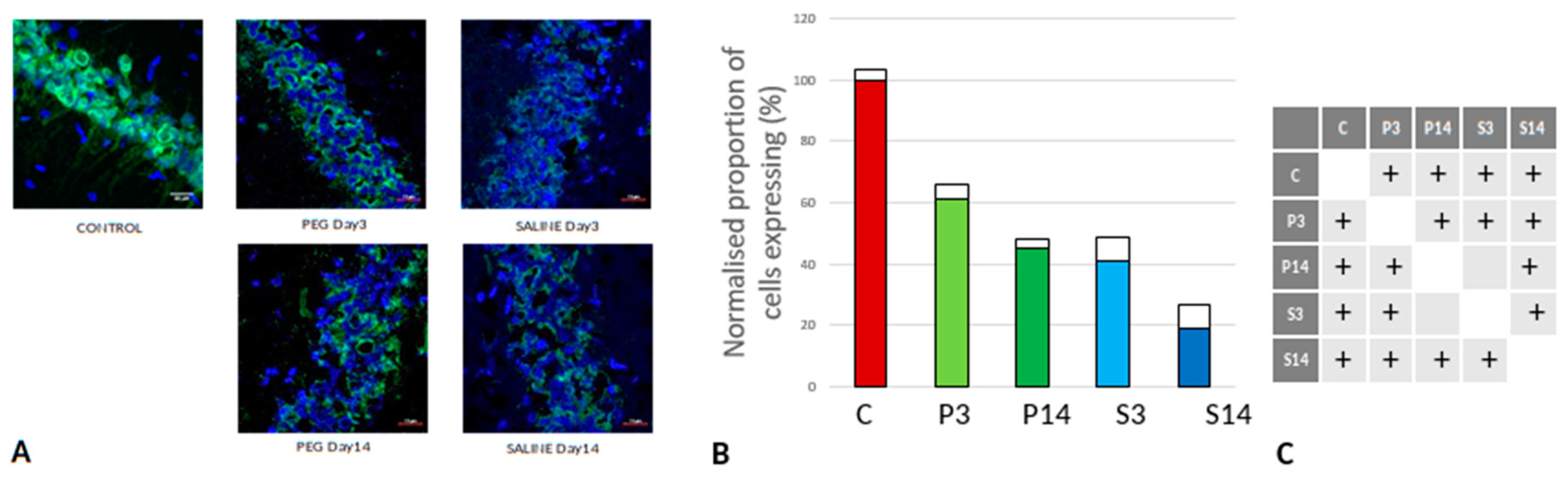

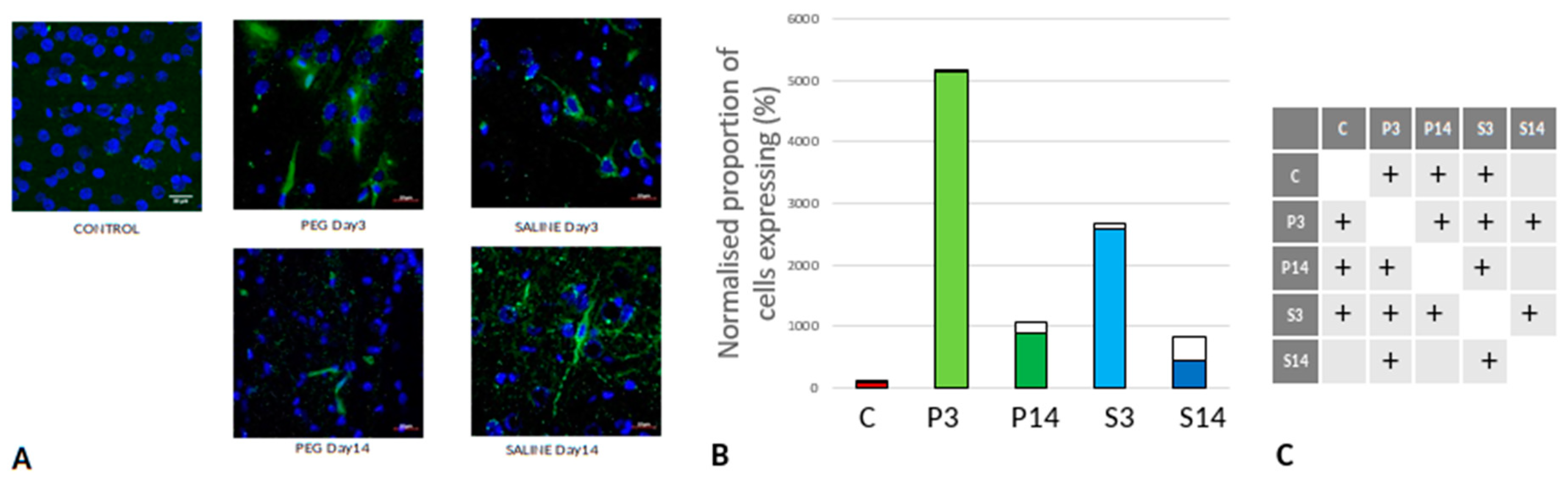

Quantification of Neuronal Loss

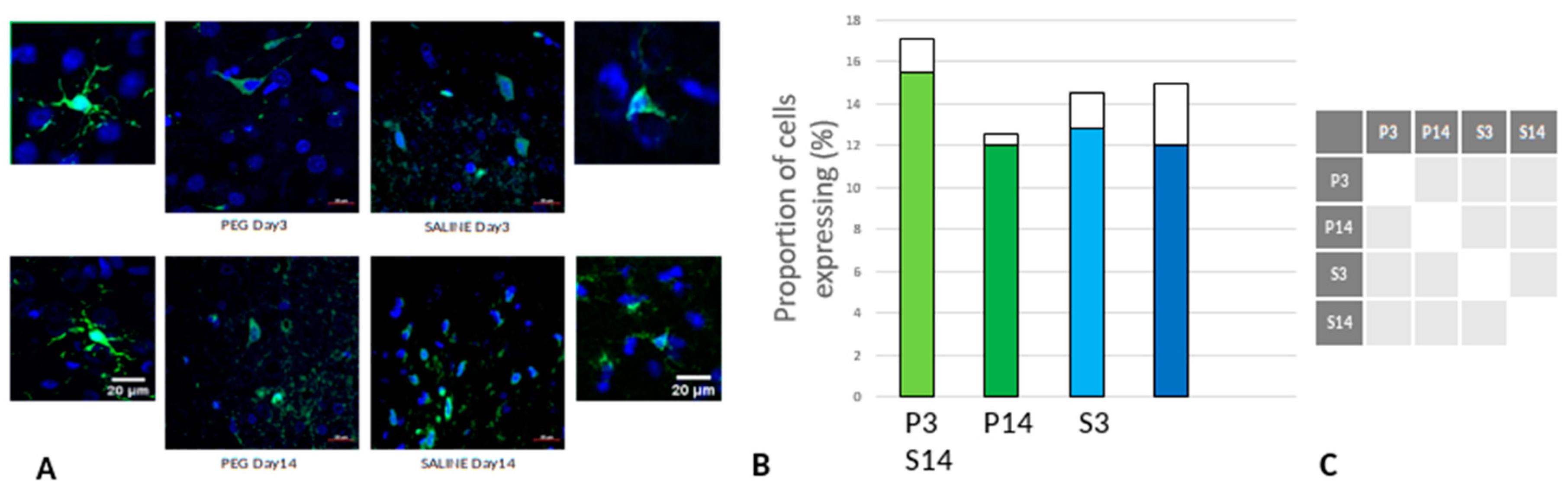

As cell survival, cell loss and cell regeneration are key biomarkers of the post-traumatic mechanisms in brain parenchyma, NeuN (an indicator of neuronal population) was used to visualize the loss of neurons following the blast impact. NeuN is a soluble nuclear protein which can serve as a neuronal marker by binding to the DNA in post-mitotic neurons of the vertebrate nervous system (Mullen et al., 1992; Wolf et al., 1996). In the cortex and hippocampal regions (CA1 and dentate gyrus) a significant neuronal loss was observed in the vehicle control (SALINE-treated) compared to the PEG-HCC groups which indicates the protection of neurons by PEG-HCC treated animals. The brain regions such as cortex (

Figure 3), dentate gyrus (

Figure 4) and hippocampus (

Figure 5) showed significant neuroprotection by PEG-HCC compared to SALINE groups.

However, a significant reduction of neurons even with PEG-HCC was found compared to control, which clearly depicts damage caused by the blast. The protective impact of PEG-HCC in cortex lasted up to 14 days, while in the dentate gyrus and hippocampus, the protective effect is reduced at 14 days but remained significantly higher than with saline, indicating that the neuroprotection continued and sustained the injured cells.

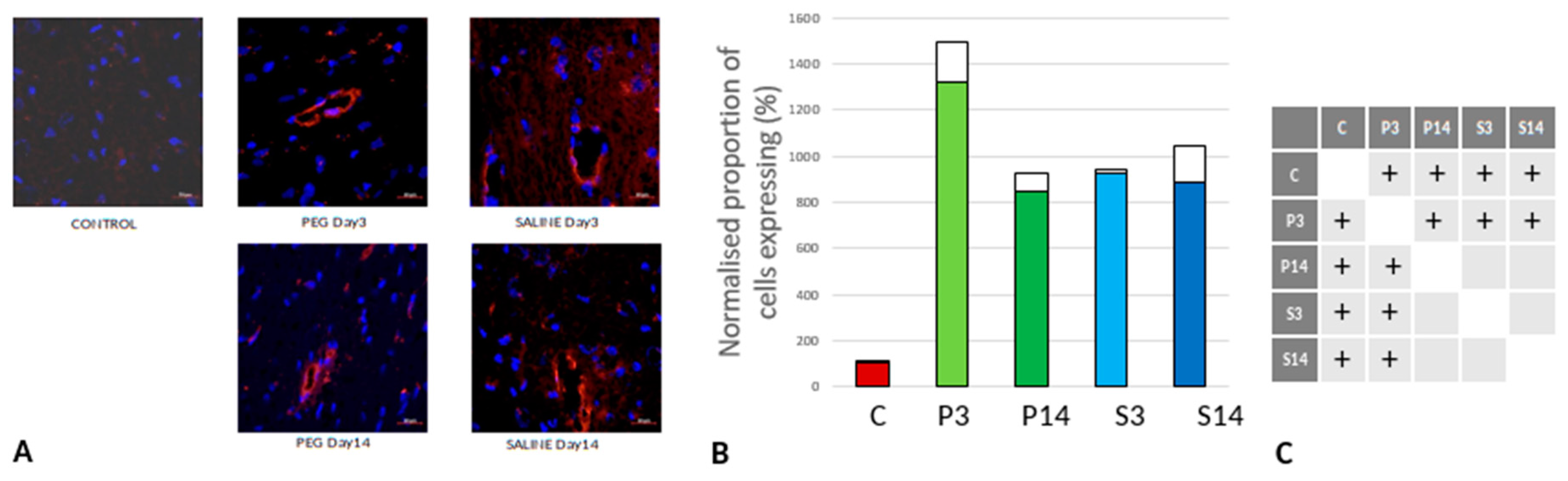

Quantification of BBB Damage

On day 3, RECA-1 increased significantly with PEG-HCC compared to SALINE, indicating a higher endothelial activity to repair the BBB damage. At day 14, the endothelial activity had fallen to the same level as in SALINE indicating a transitory stimulation of endothelial activity by PEG-HCC (

Figure 6).

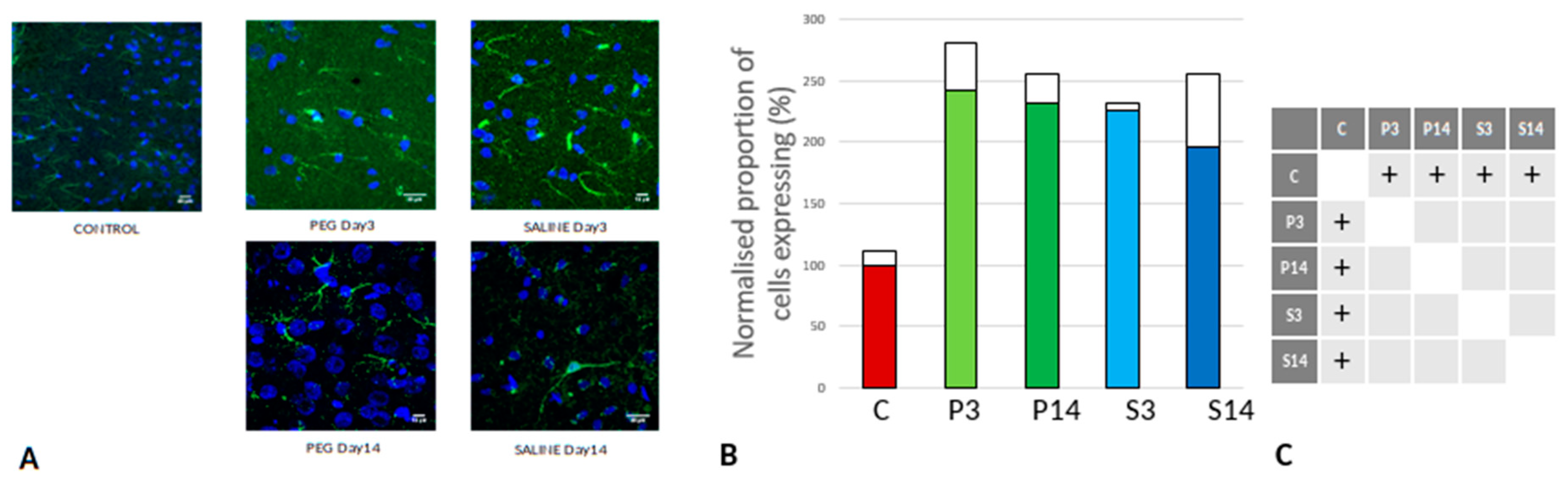

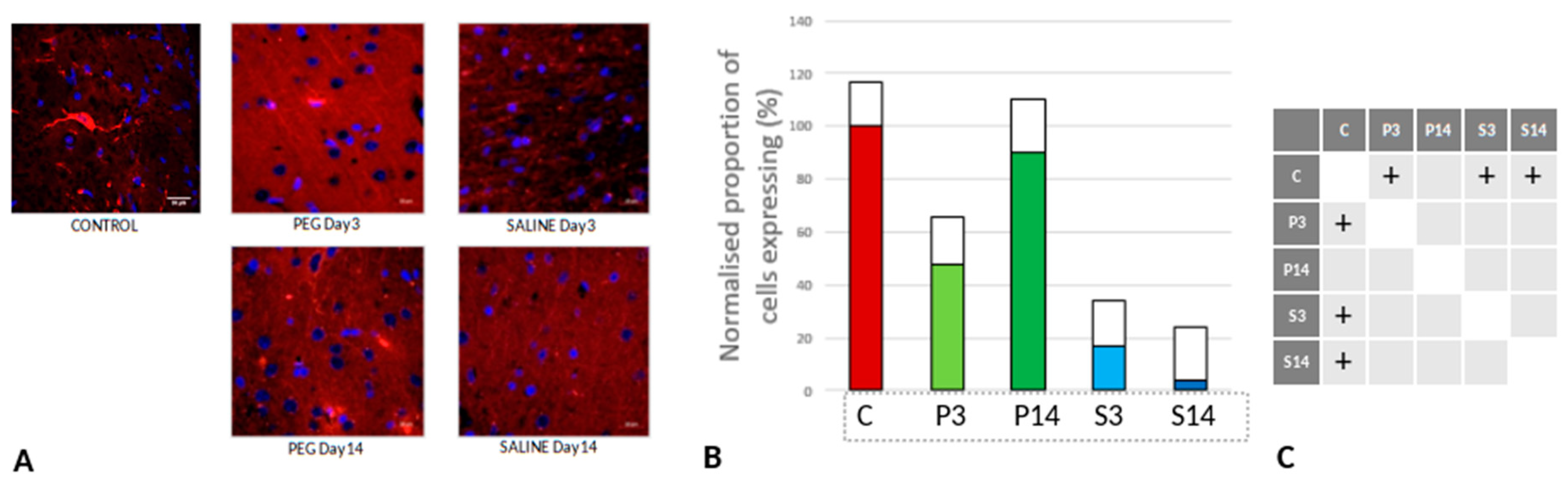

Quantification of Inflammation

Iba1 is a neuroinflammation marker expressed in microglia and an indicator of microglia activation (Ito et al., 1998; Ohsawa et al., 2004). The control group data are missing in this case due to technical reasons; nonetheless, no significant difference in the number of the Iba1+ microglia was observed across the PEG and SALINE groups (

Figure 7).

However, whereas the well ramified versions of microglial cells were the dominant cell forms in the PEG groups (3 days and 14 days), the ameboid forms of microglial cells were the dominant cell forms in the SALINE groups. GFAP is a neuroinflammatory marker expressed in astrocytes and is an indicator of astrocytic activation (Middeldorp and Hol, 2011). GFAP activity significantly increased in the PEG and the saline groups compared to the control (

Figure 8).

Visually, hypertrophy and ramifications were observed in the SALINE group as compared to PEG, showing substantial astrogliosis. On the 14th day PEG-HCC treated brain clearly showed the slow recovery/repair process of astrocytes. Brightly stained artifacts found in the slices could possibly indicate glial scar formation. Although there is no significant difference in Iba1 or GFAP between PEG-HCC and SALINE groups, there was a clear morphological difference which indicates that PEG-HCC has a protective effect even after 14 days.

Quantification of iNOS-Positive Glial Cells

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) is an inflammatory biomarker expressed in proinflammatory M1 microglia. Following TBI, iNOS is expressed in response to inflammatory stimuli and is a major producer of nitric oxide (NO). NO can react with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, a powerful toxic oxidant involved in secondary tissue injury. Thus, it is an indicator of inflammation and oxidative damage after TBI (Nathan et al., 1994; Colton et al., 1987).

Figure 9 depicts the anti-iNOS IF labelling of brain sections from rats treated with PEG or saline following injury. iNOS was clearly induced in both PEG and SALINE groups although the induction of iNOS was significantly lower in the SALINE group at day 3 compared to the PEG group. At day 14 the levels of iNOS had been greatly reduced with no significant difference between PEG and SALINE although the PEG levels were still significantly raised compared to CONTROL. The lower level of induction of iNOS in the SALINE group indicates a partial impairment of the inflammatory response that is alleviated in the PEG group.

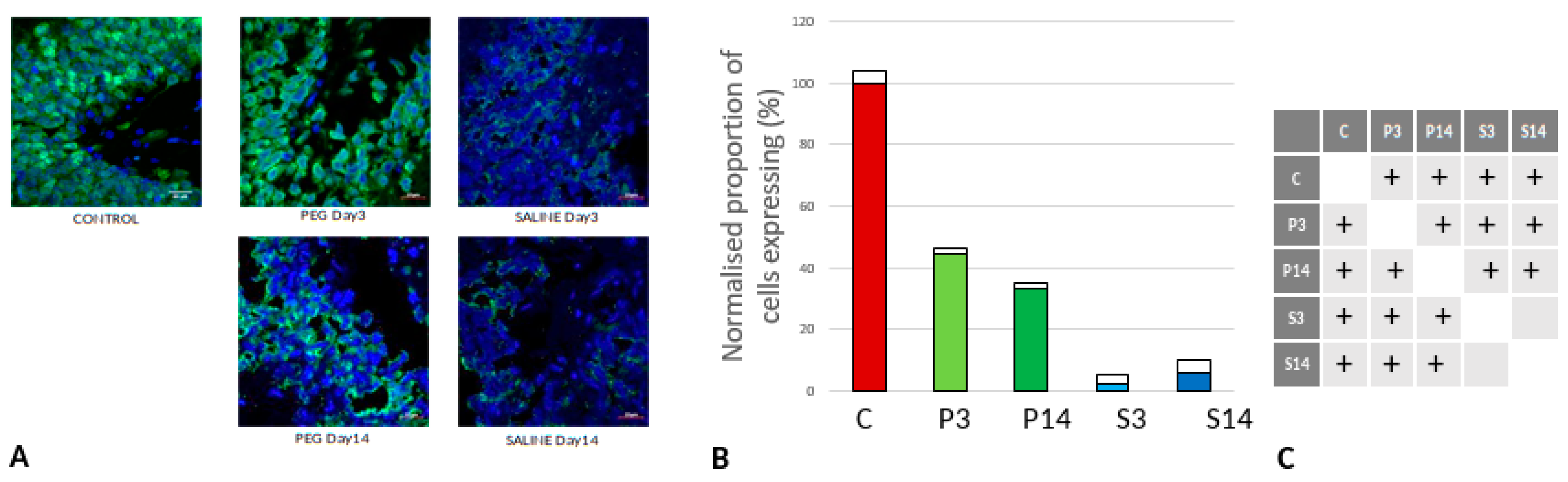

Quantification of Oligodendrocyte Regeneration

CNPase is expressed in oligodendrocytes and is an indicator of myelin integrity. An increase in CNPase is an indicator of oligodendrocyte regeneration (Baumann et al., 2001; Dyer et al., 1988). CNPase was significantly reduced at day 3 but returned to normal levels at day 14 with PEG-HCC whereas they remained at very low levels with Saline (

Figure 10). These observations are a clear indication of protection of myelin regeneration by PEG-HCC.

4. Discussion

We report here an open blast TBI model that offers a clinically realistic injury and treatment paradigm (Pun et al., 2011). Histological markers of injury demonstrated evidence of multiple parameters of injury, some mitigated significantly by PEG-HCC treatment. Based on our recent observations, PEG-HCCs can exert a promising role in preventing the oxidative stress mediated cell death by detoxifying ROS (such as SO and OH radicals) (Samuel et al., 2015). In addition, PEG-HCC treatment decreased hydrogen peroxide levels after the reperfusion of a transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) in hyperglycemic rats (Fabian et al., 2018). On the other hand, PEG-HCC scavenges the OH and SO radicals when T lymphocytes specifically internalize the PEG-HCCs. These mechanisms decrease T cell mediated inflammation in an MS (multiple sclerosis) animal model (Hug et al., 2016). When neurons are incubated with sodium cyanide (a mitochondrial complex IV inhibitor), PEG-HCC protects neuronal cells from the hydrogen peroxide toxicity (Derry et al., 2019). Additionally, PEG-HCCs are capable of selectively transforming harmful superoxide radicles to dioxygen and hydrogen peroxide faster than the single active site enzymes, thereby playing a role in cytoprotection (Samuel et al., 2015).

To date, there are no FDA approved therapies for treatment of traumatic brain injury. Here, we studied the pathological consequences of blast TBI and showed how PEG-HCC protects neurons against TBI-caused damage by using immunostainings of injury related markers. Our findings from a rat open blast TBI model provided evidence for neuroprotective effects of PEG-HCC when administered within the golden hour after the blast, even with IP dosing that may not provide the drug immediately available to the brain. We infer that acute dosage of PEG-HCC as used in this study provided a significant protective effect but not complete protection with some of the effects enduring for the 14 day experimental period.

Neurons undergo necrosis during primary injury, and continue to undergo apoptosis due to the continuous effects of secondary injury (Royo et al., 2003). Blast-induced TBI can be due to a direct blast wave to the skull or overpressure from the vascular system due to disruptions in BBB integrity following blast exposure (Kabu et al., 2015). The direct blast wave may whiplash the brain in a violent motion inside the skull resulting in diffuse axonal damage that eventually causes neuronal death. Higher NeuN immunoreactivity in the PEG-HCC groups indicates neuroprotection after treatment, potentially by inhibition of neuroinflammation activated by necrotic cell bodies, thus preventing inflammation-activated apoptosis. Additionally, we observed increased NeuN immunoreactivity in the cortex region at 14 days than at 3 days post-treatment, which is a probable sign of healing. However, after 14 days, DG and CA1 of hippocampus showed a decline in NeuN immunoreactivity, suggesting that the effects of PEG-HCC may only be transient. Neuronal damage greatly increases iNOS expression, with peak concentrations reaching 1–2 days after TBI. In response to the cytokines, iNOS is predominantly expressed in glial cells. During inflammation, NO is continually produced by iNOS until the synthase is degraded (Garry et al., 2015). By inhibiting ferroptosis (iron dependent cellular death), iNOS keeps the M1 microglia cells alive. Consequently, TBI increases neuroinflammation whereas treatment with L-NIL (iNOS inhibitor) alleviates the inflammatory process and elevates the expression of ferroptosis proteins (Qu et al., 2022).

The blast model used in this study was chosen to give principal focus on direct effects on the brain. With the rat lying prone with the head fixed facing the blast in an open field, the dominant effect would be a primary blast injury on the brain with minimal higher order blast injuries from penetration, acceleration/deceleration or blood loss. The blast would result in an energy wave travelling through the brain in a rostral to dorsal direction affecting all parts of the brain. With an open field there would be minimal reflections amplifying or focusing the blast force. Since the rest of the animal bodies were protected by body armour, there would be minimal indirect effects on the brain through the respiratory or circulatory systems (Bryden et al., 2019; Cernak, 2015). At the site of blast exposure, the level of the blast force the rats were exposed to (blast overpressure 89.6 – 518.5 kPa, mean 164.8 kPa) was non-lethal. In humans, this level of blast force would cause concussion and long-term effects such as PTSD. (Rosenfeld et al., 2013; Champion et al., 2009)

In a previous study using a similar blast model, animals that survived the explosion exhibited noticeable alterations in brain structure, metabolism, and inflammation, indicating potential damage to the brain. The persistence of certain structural changes even in later stages is concerning, suggesting these changes could be long-lasting and result in significant functional impairments (Pun et al., 2011). Standard clinical imaging tools typically lack the sensitivity to detect ultrastructural changes in the brain resulting from mild blast traumatic brain injury. Therefore, the absence of obvious changes in routine clinical assessments does not guarantee the absence of injuries. In our previous study, histopathological examinations revealed ultrastructural changes in animals that were not detectable by standard clinical imaging tools (Pun et al., 2011).

Our previous findings also demonstrate a dose-response relationship between blast overpressure and observed changes especially in large animals (i.e. NHP). For instance, animals exposed to higher levels of blast showed more pronounced behavioural deficits, scalp hematomas (no subarachnoid haemorrhage or subdural haemorrhage was observed), and histopathological changes compared to those exposed to lower levels of blast (Lu et al., 2012).

We used Iba1 and GFAP antibodies to detect the activated microglia and reactive astrocytes in order to examine the activation of this inflammation pathway. Though there was no discernible difference between the PEG and SALINE groups in terms of numbers of glial cells, we observed changes in microglia morphology. As seen in

Figure 7A, microglia exist in its ramified resting state in the PEG treated group and in an activated amoeboid state in the SALINE group. In their typical ramified shape, microglia constantly survey for debris and foreign bodies. Microglia become activated and convert to their phagocytic amoeboid state in response to the severe injury. These amoeboid microglia are responsible for the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Kettenmann et al., 2011; Stoll et al., 1999). When compared to PEG, the GFAP-positive reactive astrocytes showed some cellular hypertrophy and a higher degree of ramification in SALINE groups, indicating an elevated astrogliosis. Acute CNS injury causes astrocyte morphological alteration and changes in molecular expression as well as the formation of glial scars. If the triggering mechanism has been resolved, there is a possibility for resolution and neuroprotection in mild astrogliosis, resulting in no overlap of reactive astrocytes and glial scars (Sofroniew, 2009). Our observations on the state of the neuroinflammatory cells is consistent with a recently published blast overpressure experiment by Toklu and colleagues who reported a change in morphology for microglia and GFAP for animals exposed to a single blast, and an increase in immunoreactivity in the frontal cortex for those exposed to repeated blasts (Toklu et al., 2018). In another investigation, there was no increased GFAP expression in brain cortex homogenates of rats with body armour (Svetlov et al., 2010). In a previous study, it was shown that torso protection reduces the intensity of MPO, a neutrophil infiltration marker indicating oxidative stress, when compared to animals with or without head protection (Cernak, 2010). These findings emphasize the importance of systemic reactions and how they affect neuroinflammation markers.

CNPase was chosen as a myelin-producing oligodendrocyte marker because it is abundantly expressed in oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells (Sprinkle, 1989). The myelin marker CNPase is related to oligodendrocyte maturation and is widely expressed in pre-myelinating and myelinating oligodendrocytes (Trapp et al., 1988; Verrier et al., 2013). We observed an increased level of CNPase expression in PEG groups which may be related to oligodendrocyte regeneration. Oxidative stress from TBI can cause the oligodendrocytes to undergo apoptosis. Because of extremely poor glutathione production, oligodendrocytes are very susceptible to damage caused by oxidative stress (Thorburne & Juurlink, 1996). Apoptosis can also be induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines released by the amoeboid reactive microglia. At day 14 the SALINE group animals show a drop in CNPase expression. This may highlight an endogenous mechanism that replaces the oligodendrocyte population through the proliferation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. A few groups reported an increase in the number of Olig2+ cells after injury (Dent et al., 2015; Flygt at al., 2013). Our findings indicate that between days 3 and 14 of post-TBI the PEG-treated groups showed a significant increase in oligodendrocytes. It is apparent that the PEG-HCC accelerated the oligodendrogenesis process. We also note the higher CNPase expression in PEG-treated groups 3 days post-TBI, when compared to the saline-treated group at the same time point. This led us to infer that PEG plays a clear role in protecting the oligodendrocytes from undergoing apoptosis, possibly through its antioxidant properties discussed above.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated qualitatively and quantitatively that PEG-HCC (Tour et al., 2017) is involved in neuroprotection after traumatic brain injury in an open blast rat model. The blast model used focuses on direct blast effects and injuries of the brain. The blast would result in a short standing energy wave that progressed with very high energy through the whole brain resulting in direct lesions, spalling and shearing effects. Blast loads create very brief acceleration durations that may cause distinct neurophysiological outcomes. We used our existing patented PEG-HCCs with antioxidant properties to treat oxidative stress caused by TBI (Tour et al., 2017). Previous studies have indicated that PEG-HCC can recover and maintain the brain’s structural and homeostatic environment by reducing neuronal and glial cell death. The different states of activation of microglia and astrocytes seen across time in the various cohorts of the study indicate the intricate and complex roles of PEG-HCCs in the management of neuroinflammation and neuronal and glial death. Our current experimental data support the efficacy of our carbon clusters PEG-HCC against the post-TBI effects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the contributions by Mathangi Palanivel, Zoey Fong Lai Guan, Dustin James, Siti Nabilah Binte Hamidon, Najwa Talib, Chinnasamy Gandhimathi, Padmalosini Muthukumaran as well as the support from NTU’s Imaging Probe Development Platform (IPDP) and Cognitive Neuroimaging Centre (CONIC). We thank Stefan Siwko, PhD for editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

Drs. Tour and Kent’s respective institutions own the intellectual property for the PEG-HCCs. JMT and TAK are co-founders of Gerenox Inc. TAK is an officer. Conflicts of interest are managed by the Technology Transfer offices of their respective institutions.

Abbreviations

BBB - blood-brain-barrier; CA1 – CA1 layer of the hippocampus; CNPase - 2’,3’-cyclic-nucleotide 3’-phosphodiesterase; CNS - central nervous system; DAPI - 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DG – dentate gyrus; GFAP - glial fibrillary acidic protein; Iba1 - Ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule 1; IHC – immunohistochemistry; iNOS - inducible nitric oxide synthase; IP – intraperitoneal; NeuN - neuronal nuclei; PEG-HCCs - Poly-ethylene-glycol-functionalized hydrophilic carbon clusters; PETN - penta-erythritol tetra-nitrate; RECA-1 - rat endothelial cell antigen 1; ROS - reactive oxygen species; TBI - traumatic brain injury; TBST - tris-buffered saline with 0.1% tween® 20 detergent; TNT - 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene

References

- Baumann, N.; Pham-Dinh, D. Biology of Oligodendrocyte and Myelin in the Mammalian Central Nervous System. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 871–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlin, J.M.; Leonard, A.D.; Pham, T.T.; Sano, D.; Marcano, D.C.; Yan, S.; Fiorentino, S.; Milas, Z.L.; Kosynkin, D.V.; Price, B.K.; et al. Effective Drug Delivery, In Vitro and In Vivo, by Carbon-Based Nanovectors Noncovalently Loaded with Unmodified Paclitaxel. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4621–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitner, B.R.; Marcano, D.C.; Berlin, J.M.; Fabian, R.H.; Cherian, L.; Culver, J.C.; Dickinson, M.E.; Robertson, C.S.; Pautler, R.G.; Kent, T.A.; et al. Hydrophilic carbon clusters as therapeutic, high-capacity antioxidants. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8007–8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitner, B.R.; Marcano, D.C.; Berlin, J.M.; Fabian, R.H.; Cherian, L.; Culver, J.C.; Dickinson, M.E.; Robertson, C.S.; Pautler, R.G.; Kent, T.A.; et al. Antioxidant Carbon Particles Improve Cerebrovascular Dysfunction Following Traumatic Brain Injury. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8007–8014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobadilla, A.D.; Samuel, E.L.G.; Tour, J.M.; Seminario, J.M. Calculating the Hydrodynamic Volume of Poly(ethylene oxylated) Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Hydrophilic Carbon Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. B 2012, 117, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bony BA, Kievit FM. A role for nanoparticles in treating traumatic brain injury. Pharmaceutics 2019;11(9):473. Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Long-Term Consequences of Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Status of Potential Mechanisms of Injury and Neurological Outcomes. J Neurotrauma 2015;32(23):1834-1848.

- Bryden, D.W.; I Tilghman, J.; Hinds, S.R. Blast-Related Traumatic Brain Injury: Current Concepts and Research Considerations. J. Exp. Neurosci. 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattin, A.-L.; Burden, J.J.; Van Emmenis, L.; Mackenzie, F.E.; Hoving, J.J.; Calavia, N.G.; Guo, Y.; McLaughlin, M.; Rosenberg, L.H.; Quereda, V.; et al. Macrophage-Induced Blood Vessels Guide Schwann Cell-Mediated Regeneration of Peripheral Nerves. Cell 2015, 162, 1127–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernak. Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. In: Kobeissy, editor. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis (NCBI Bookshelf); 2015. Chapter 45, Blast Injuries and Blast-Induced Neurotrauma.

- Champion, H.R.; Holcomb, J.B.; Young, L.A. Injuries From Explosions: Physics, Biophysics, Pathology, and Required Research Focus. J. Trauma: Inj. Infect. Crit. Care 2009, 66, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.R.; Trooskin, S.Z.; Doshi, P.J.; Greenwald, L.; Mode, C.J. Time to Laparotomy for Intra-abdominal Bleeding from Trauma Does Affect Survival for Delays Up to 90 Minutes. 2002, 52, 420–425. [CrossRef]

- Colton, C.A.; Gilbert, D.L. Production of superoxide anions by a CNS macrophage, the microglia. FEBS Lett. 1987, 223, 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty J, Waltzman D, Sarmiento K, et al. Traumatic brain injury–related deaths by race/ethnicity, sex, intent, and mechanism of injury—United States, 2000–2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68(46):1050.

- Derry, P.J.; Nilewski, L.G.; Sikkema, W.K.A.; Mendoza, K.; Jalilov, A.; Berka, V.; McHugh, E.A.; Tsai, A.-L.; Tour, J.M.; Kent, T.A. Catalytic oxidation and reduction reactions of hydrophilic carbon clusters with NADH and cytochrome C: features of an electron transport nanozyme. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 10791–10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, P.J.; Nilewski, L.G.; Sikkema, W.K.A.; Mendoza, K.; Jalilov, A.; Berka, V.; McHugh, E.A.; Tsai, A.-L.; Tour, J.M.; Kent, T.A. Catalytic oxidation and reduction reactions of hydrophilic carbon clusters with NADH and cytochrome C: features of an electron transport nanozyme. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 10791–10807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietro, V.; Yakoub, K.M.; Caruso, G.; Lazzarino, G.; Signoretti, S.; Barbey, A.K.; Tavazzi, B.; Lazzarino, G.; Belli, A.; Amorini, A.M. Antioxidant Therapies in Traumatic Brain Injury. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer CA, Benjamins JA. Organization of oligodendroglial membrane sheets. I. Association of myelin basic protein and 2',3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphohydrolase with cytoskeleton. J Neurosci Res. 1988 Mar;19(3):267-78. [CrossRef]

- Eng, L.F.; Ghirnikar, R.S.; Lee, Y.L. Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein: GFAP-Thirty-One Years (1969–2000). Neurochem. Res. 2000, 25, 1439–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, R.H.; Derry, P.J.; Rea, H.C.; Dalmeida, W.V.; Nilewski, L.G.; Sikkema, W.K.A.; Mandava, P.; Tsai, A.-L.; Mendoza, K.; Berka, V.; et al. Efficacy of Novel Carbon Nanoparticle Antioxidant Therapy in a Severe Model of Reversible Middle Cerebral Artery Stroke in Acutely Hyperglycemic Rats. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, C.E. Neurons, glia, and plasticity in normal brain aging. Neurobiol. Aging 2003, 24, S123–S127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman HJ, Zhang. H Targeting oxidative stress in disease: promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20;689-709.

- Gardner A, Zafonte R. Neuroepidemiology of traumatic brain injury. Handb. Clin. Neurol 2016;138:207-223.

- Gardner RC, Burke JF, Nettiksimmons J, et al. Traumatic brain injury in later life increases risk for P arkinson disease. Ann. Neurol 2015;77(6): 987-995.

- Garry, P.; Ezra, M.; Rowland, M.; Westbrook, J.; Pattinson, K. The role of the nitric oxide pathway in brain injury and its treatment — From bench to bedside. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 263, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girgis, F.; Pace, J.; Sweet, J.; Miller, J.P. Hippocampal Neurophysiologic Changes after Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Potential Neuromodulation Treatment Approaches. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham NS, Sharp J. Understanding neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury: from mechanisms to clinical trials in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2019;90:1221-1233.

- Gravel, M. , Peterson, J., Yong, V.W., Kottis, V., Trapp, B., & Braun, P.E. (1996). Overexpression of 2',3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase: Role in oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 44(2), 104-117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, H.J.G.; Jensen, E.B. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction*. J. Microsc. 1987, 147, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huq, R.; Samuel, E.L.G.; Sikkema, W.K.A.; Nilewski, L.G.; Lee, T.; Tanner, M.R.; Khan, F.S.; Porter, P.C.; Tajhya, R.B.; Patel, R.S.; et al. Preferential uptake of antioxidant carbon nanoparticles by T lymphocytes for immunomodulation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, srep33808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.L.; Chatlos, T.; Gorse, K.M.; Lafrenaye, A.D. Neuronal Membrane Disruption Occurs Late Following Diffuse Brain Trauma in Rats and Involves a Subpopulation of NeuN Negative Cortical Neurons. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, D.; Imai, Y.; Ohsawa, K.; Nakajima, K.; Fukuuchi, Y.; Kohsaka, S. Microglia-specific localisation of a novel calcium binding protein, Iba1. Mol. Brain Res. 1998, 57, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabu, S.; Jaffer, H.; Petro, M.; Dudzinski, D.; Stewart, D.; Courtney, A.; Courtney, M.; Labhasetwar, V. Blast-Associated Shock Waves Result in Increased Brain Vascular Leakage and Elevated ROS Levels in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0127971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, C.; Singh, J.; Moochhala, S.; Lim, M.K.; Lu, J.; A Ling, E. Induction of NADPH diaphorase/nitric oxide synthase in the spinal cord motor neurons of rats following a single and multiple non-penetrative blasts. . 1999, 14, 417–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, C.; Sivakumar, V.; Yong, Z.; Lu, J.; Foulds, W.; Ling, E. Blood–retinal barrier disruption and ultrastructural changes in the hypoxic retina in adult rats: the beneficial effect of melatonin administration. J. Pathol. 2007, 212, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettenmann, H.; Hanisch, U.-K.; Noda, M.; Verkhratsky, A. Physiology of Microglia. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 461–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Bhardwaj, K.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Bhardwaj, S.; Bhatia, S.K.; Verma, R.; Kumar, D. Antioxidant Functionalized Nanoparticles: A Combat against Oxidative Stress. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, E.B.; Moscati, R.M. The Golden Hour: Scientific Fact or Medical “Urban Legend”? Acad. Emerg. Med. 2001, 8, 758–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Moochhala S, Shirhan M, Ng KC, Teo AL, Tan MH, Moore XL, Wong MC, Ling EA. Neuroprotection by aminoguanidine after lateral fluid-percussive brain injury in rats: a combined magnetic resonance imaging, histopathologic and functional study. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:253–263.

- Lu, J.; Ng, K.C.; Ling, G.; Wu, J.; Poon, D.J.F.; Kan, E.M.; Tan, M.H.; Wu, Y.J.; Li, P.; Moochhala, S.; et al. Effect of Blast Exposure on the Brain Structure and Cognition inMacaca fascicularis. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 1434–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.I.R.; Menon, D.K.; Adelson, P.D.; Andelic, N.; Bell, M.J.; Belli, A.; Bragge, P.; Brazinova, A.; Büki, A.; Chesnut, R.M.; et al. Traumatic brain injury: Integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 987–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcano, D.C.; Bitner, B.R.; Berlin, J.M.; Jarjour, J.; Lee, J.M.; Jacob, A.; Fabian, R.H.; Kent, T.A.; Tour, J.M. Design of Poly(ethylene Glycol)-Functionalized Hydrophilic Carbon Clusters for Targeted Therapy of Cerebrovascular Dysfunction in Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neurotrauma 2013, 30, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meabon, J.S.; Huber, B.R.; Cross, D.J.; Richards, T.L.; Minoshima, S.; Pagulayan, K.F.; Li, G.; Meeker, K.D.; Kraemer, B.C.; Petrie, E.C.; et al. Repetitive blast exposure in mice and combat veterans causes persistent cerebellar dysfunction. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 321ra6–321ra6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, K.; Mendoza, K.; Derry, P.J.; Derry, P.J.; Cherian, L.M.; Cherian, L.M.; Garcia, R.; Garcia, R.; Nilewski, L.; Nilewski, L.; et al. Functional and Structural Improvement with a Catalytic Carbon Nano-Antioxidant in Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury Complicated by Hypotension and Resuscitation. J. Neurotrauma 2019, 36, 2139–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza K, Derry PJ, Cherian LM. Functional and Structural Improvement with a Catalytic Carbon Nano-Antioxidant in Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury Complicated by Hypotension and Resuscitation. J. Neurotrauma 2019;36(13):2139-2146.

- Middeldorp, J.; Hol, E.M. GFAP in health and disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011, 93, 421–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, R.J.; Buck, C.R.; Smith, A.M. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. . 1992, 116, 201–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nathan, C.; Xie, Q.-W. Nitric oxide synthases: Roles, tolls, and controls. Cell 1994, 78, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohsawa, K.; Imai, Y.; Sasaki, Y.; Kohsaka, S. Microglia/macrophage-specific protein Iba1 binds to fimbrin and enhances its actin-bundling activity. J. Neurochem. 2004, 88, 844–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, P.; Palanivel, M.; Kumar, A.; Máthé, D.; Radda, G.K.; Lim, K.-L.; Gulyás, B. Nanotheranostic agents for neurodegenerative diseases. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2020, 4, 645–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, H.; Mondello, S.; Wilson, A.; Dittmer, T.; Rohde, N.N.; Schroeder, P.J.; Nichols, J.; McGirt, C.; Hoffman, J.; Tanksley, K.; et al. Characteristics and Impact of U.S. Military Blast-Related Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, P.B.L.; Kan, E.M.; Salim, A.; Li, Z.; Ng, K.C.; Moochhala, S.M.; Ling, E.-A.; Tan, M.H.; Lu, J. Low Level Primary Blast Injury in Rodent Brain. Front. Neurol. 2011, 2, 10063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Peng, W.; Wu, Y.; Rui, T.; Luo, C.; Zhang, J. Targeting iNOS Alleviates Early Brain Injury After Experimental Subarachnoid Hemorrhage via Promoting Ferroptosis of M1 Microglia and Reducing Neuroinflammation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 3124–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, J.V.; McFarlane, A.C.; Bragge, P.; Armonda, R.A.; Grimes, J.B.; Ling, G.S. Blast-related traumatic brain injury. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royo, N.C.; Schouten, J.W.; Fulp, C.T.; Shimizu, S.; Marklund, N.; Graham, D.I.; McIntosh, T.K. From Cell Death to Neuronal Regeneration: Building a New Brain after Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2003, 62, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahni, D.; Jea, A.; Mata, J.A.; Marcano, D.C.; Sivaganesan, A.; Berlin, J.M.; Tatsui, C.E.; Sun, Z.; Luerssen, T.G.; Meng, S.; et al. Biocompatibility of pristine graphene for neuronal interface. J. Neurosurgery: Pediatr. 2013, 11, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, E.L.; Duong, M.T.; Bitner, B.R.; Marcano, D.C.; Tour, J.M.; Kent, T.A. Hydrophilic carbon clusters as therapeutic, high-capacity antioxidants. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, E.L.G.; Marcano, D.C.; Berka, V.; Bitner, B.R.; Wu, G.; Potter, A.; Fabian, R.H.; Pautler, R.G.; Kent, T.A.; Tsai, A.-L.; et al. Highly efficient conversion of superoxide to oxygen using hydrophilic carbon clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, E.L.G.; Marcano, D.C.; Berka, V.; Bitner, B.R.; Wu, G.; Potter, A.; Fabian, R.H.; Pautler, R.G.; Kent, T.A.; Tsai, A.-L.; et al. Highly efficient conversion of superoxide to oxygen using hydrophilic carbon clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 2343–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel SJ, Acosta S Lozano D. Neuroinflammation in traumatic brain injury: A chronic response to an acute injury. Brain Circ 2017;3(3):135.

- Shi, R. Polyethylene glycol repairs membrane damage and enhances functional recovery: a tissue engineering approach to spinal cord injury. Neurosci. Bull. 2013, 29, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stollg, G.; Jander, S. The role of microglia and macrophages in the pathophysiology of the CNS. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999, 58, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Marushima, A.; Nagasaki, Y.; Hirayama, A.; Muroi, A.; Puentes, S.; Mujagic, A.; Ishikawa, E.; Matsumura, A. Novel neuroprotection using antioxidant nanoparticles in a mouse model of head trauma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020, 88, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tour JM, Berlin J, Marcano D, et al. Use of carbon nanomaterials with antioxidant properties to treat oxidative stress. USA Patent 2017; US 9,572, 834 B.

- Trapp BD, Bernier L, Andrews SB, et al. Cellular and subcellular distribution of 2',3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase and its mRNA in the rat central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 1998;51(3):859–868.

- Verrier JD, Jackson TC, Gillespie DG, et al. Role of CNPase in the oligodendrocytic extracellular 2',3'-cAMP-adenosine pathway. Glia 2013;61(10):1595–1606.

- West, M.J.; Slomianka, L.; Gundersen, H.J.G. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in the subdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat. Rec. 1991, 231, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf HK, Buslei R, Schmidt-Kastner R, Schmidt-Kastner PK, Pietsch T, Wiestler OD, Blumcke I. NeuN: a useful neuronal marker for diagnostic histopathology. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996 Aug;44(10):1167-71. doi: 10.1177/44.10.8813085. PMID: 8813085.Xue LP, Lu J, Cao Q, Hu S, Ding P, Ling EA. Müller glial cells express nestin coupled with glial fibrillary acidic protein in experimentally induced glaucoma in the rat retina. Neuroscience. 2006;139:723–732.Xue LP, Lu J, Cao Q, Hu S, Ding P, Ling EA. Müller glial cells express nestin coupled with glial fibrillary acidic protein in experimentally induced glaucoma in the rat retina. Neuroscience. 2006;139:723–732. [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Lu, J.; Cao, Q.; Kaur, C.; Ling, E.-A. Nestin expression in Müller glial cells in postnatal rat retina and its upregulation following optic nerve transection. Neuroscience 2006, 143, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.; Meng, K.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Qu, W.; Chen, D.; Xie, S. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of nanocarriers in vivo and their influences. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 284, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng R, Lee K, Qi Z, Wang Z, Xu Z, Wu X, Mao Y, Neuroinflammation Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Take It Seriously or Not Front. Immun. 2022.

- Zou, Y.; Lu, J.; Poon, D.; Kaur, C.; Cao, Q.; Teo, A.; Ling, E. Combustion smoke exposure induces up-regulated expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, aquaporin 4, nitric oxide synthases and vascular permeability in the retina of adult rats. Neuroscience 2009, 160, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Timeline of the acute experiment.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the acute experiment.

Figure 2.

The post-traumatic events in brain parenchyma, their interrelationships, and the neuronal markers used for their visualization and quantification in the present study.

Figure 2.

The post-traumatic events in brain parenchyma, their interrelationships, and the neuronal markers used for their visualization and quantification in the present study.

Figure 3.

(A) Cortex nuclei immunofluorescence analysis of neurons stained with antibodies to NeuN (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of NeuN (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 3.

(A) Cortex nuclei immunofluorescence analysis of neurons stained with antibodies to NeuN (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of NeuN (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 4.

(A) Dentate gyrus nuclear immunofluorescence analysis labelling neurons with anti-NeuN(green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of NeuN (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 4.

(A) Dentate gyrus nuclear immunofluorescence analysis labelling neurons with anti-NeuN(green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of NeuN (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 5.

(A) Hippocampus nuclear immunofluorescence analysis labelling neurons with NeuN (green) antibodies and counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of NeuN (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 5.

(A) Hippocampus nuclear immunofluorescence analysis labelling neurons with NeuN (green) antibodies and counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of NeuN (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 6.

(A) RECA-1 (green) immunofluorescence labelling of cortical neurons that are counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of RECA-1 (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 6.

(A) RECA-1 (green) immunofluorescence labelling of cortical neurons that are counterstained with DAPI (blue): examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of RECA-1 (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 7.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with Iba1 (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. The smaller frames are higher magnification views showing representative microglia cells. (B) Average number of labelled cells/field of view in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 7.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with Iba1 (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. The smaller frames are higher magnification views showing representative microglia cells. (B) Average number of labelled cells/field of view in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 8.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with GFAP (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of GFAP (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 8.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with GFAP (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of GFAP (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 9.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with iNOS (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of iNOS (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 9.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with iNOS (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of iNOS (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 10.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with CNPase (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of CNPase (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

Figure 10.

(A) Immunofluorescence labelling of neurons that are stained with CNPase (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue) for nuclei in the cortex: examples from the CONTROL (C), PEG (P) and SALINE (S) groups analysed 3 (P3, S3) and 14 (P14, S14) days post-blast. (B) Average levels of CNPase (normalised to the control) in the PEG and SALINE groups. Coloured bar = mean, open bar = 1 S.D. (C) Statistically significant differences (+ refers to p<0.05).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).