1. Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a two faceted injury. After the initial trauma on the brain, the secondary injury is elicited by a severe inflammatory response and breakdown of the blood brain barrier (BBB) that leads to continued damage to the tissue. The progression of the secondary injury manifest as altered motor, sensory or cognitive skills or psychological changes [

1,

2,

3]. One clinical study reported 30% of patients who receive a moderate to severe injury became worse in the following 5 consecutive years post injury [

4]. Lifelong cost associated with TBI total approximately

$76.5 billion in direct and indirect expenses [

5]. Moderate to severe TBIs result in hospitalization where patients are monitored for intracranial pressure, blood flow, and excitotoxicity. Surgical interventions include removing blood clots, decompressive craniectomy, implantation of monitoring device and/or implantation of ventriculoperitoneal shunts to relieve pressure. Currently there is no established drug therapy targeting the underlying progressive pathophysiology damage in TBI, but symptoms are managed through use of steroids, anti-anxiety, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, diuretics, muscle relaxants or stimulants [

6,

7]. Current preclinical research is focused on diminishing the inflammatory reaction initiated by the secondary injury.

Preclinical therapies for TBI focus to reducing the deleterious effects of the inflammatory reaction in the microenvironment [

7]. The secondary injury is characterized by the breakdown of the BBB, infiltration and activation of monocytes/macrophages, inflammation, axonal injury, apoptosis, and activation of glial cells [

8,

9]. After injury the BBB increases permeability and facilitates infiltration of pro-inflammatory phenotypic monocytes/macrophages [

9,

10]. Astrocytes, a type of glial cell, rapidly activate by upregulating the expression of glial fibrillar acidic protein (GFAP), an intermediate filament protein, and form a barrier that limits neurotrauma by preserving neuronal synapses, reduce the spread of inflammatory cytokines, reduce excitotoxicity and supports the recovery of the extracellular matrix [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Activation of astrocytes leaded to the formation of glial scar which causes detrimental effects such as reduced neuronal plasticity, inhibition of axonal extension, decreased ability for regeneration with the release of inhibitory growth molecules such as chondroitin and keratan sulfate proteoglycans, and the promotion of cytotoxic edema [

10,

11,

12,

17,

18,

19,

20]. By 10-14 days-post-injury (DPI) there is a decrease in the number of infiltration of macrophages and number of activated astrocytes at the site of injury, but the detrimental results from the glial scar can be observed [

8,

21,

22,

23]. It is notable that multiple studies have shown that blocking macrophage entry and eliminating astrocyte activity completely after injury did not improve neurological outcomes [

8,

16,

24]. This leads to the potential for anti-inflammatory therapeutics in the acute phase to limit activation of glial cells and modulate the molecular components of injury induced inflammation [

24,

25]. Assessment of remaining tissue during this resolution phase can indicate the ramifications of acute neuroinflammation and effectiveness of treatments [

26].

Dexamethasone, a synthetic glucocorticoid steroid, has previously been investigated to limit the neuroinflammatory reaction from TBI [

27,

28]. Several studies indicate the potential to decrease pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, reduce neuronal damage, and decrease activation of astroglia [

29,

30]. Unfortunately, systemic administration of high doses required for therapeutic effect negatively impact multiple organs and organ systems [

31]. Furthermore, when used to treat TBI patients clinically, there was an observed significant increase in risk of infection, chance of disability and mortality rate [

32,

33,

34].

To overcome the severe side effects associated with high dose systemic administration of DX, we developed a polyethylene glycol-bis-acryloyloxy acetate (PEG-bis-AA) hydrogel for local and sustained delivery of dexamethasone (DX) and reported that PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treated animals exhibited significantly improved motor function by rotarod test and cognitive function by Morris water maze test compared to untreated TBI animals and reduced inflammatory response, apoptosis, and lesion volume compared to untreated TBI animals at 14 DPI in a rat mild controlled cortical impact (CCI) TBI model [36, 39]. We also reported that PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment can improve motor function and inhibits secondary injury in a rat moderate CCI TBI model (35). It was observed that hydrogel treatment attenuated lesion volume, GFAP expression, apoptosis, and macrophages infiltration and increased neuronal survival and M2 macrophages in a rat moderate CCI TBI model at 7 DPI (Acute injury phase). These results suggest that local and sustained release of DX hydrogels can improve recovery in moderate TBI, likely through a reduction in secondary injury. In this study, we evaluated PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on cognitive function recovery by Morris Water Maze (MWM) test and secondary injury by histological analysis at 14 DPI (Chronic injury phase) in a rat moderate CCI TBI model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PEG-Bis-AA/HA-DXM Hydrogel Preparation

PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogels were prepared as previously described [35,36, 39]. Briefly, PEG-bis-AA and HA-DXM were dissolved in Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer saline (PBS) without Ca++ and Mg+ and to a final concentration of 6% (w/v) and 0.72% w/v, respectively. Irgacure 2959 (I-2959, 10% (w/v) dissolved in ethanol) was added for a final concentration of 0.1% w/v. Hydrogel discs were photopolymerized between two coverslips separated by 0.5 mm spacers using low intensity UV light (365 nm, 10 mW/cm2, Black-Ray B100-AP, Upland, CA, USA) for 5 minutes per side (16 µL of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM macromer solution/ gel). PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogels were 5 mm diameter, 0.5 mm thick and contain 3 μg of DX/hydrogel. Hydrogels were stored in PBS at 4°C overnight before tested for therapeutic efficacy in moderate TBI model.

2.2. Animal Care and Surgical Procedure

Twenty Male Sprague Dawley rats (8-9 weeks, Charles River, Wilmington, MA) between 290-350 g were randomly assigned to one of three groups: 1) Normal group: no surgery, 2) Untreated TBI group, and 3) PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM gel treated group (3 μg of DX/hydrogel). Rats were housed in 12-hour light/dark cycle in Godley-Snell Research Center (GSRC) at Clemson University (animal use protocol 2020-047). All animal care, maintenance and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Clemson University.

Generation of the moderate CCI injury models in rats was performed as described in our previous publication [

35]. Briefly, rats were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The head was secured in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) and the surgical area was scrubbed with alcohol and betadine. Under aseptic conditions, a midline incision was performed and the skull was cleared of connective tissue. A 6 mm craniectomy was performed using a trephine burr, over the right hemisphere (midpoint 3.0 mm lateral, 1.0 mm caudal to bregma) without disruption of the dura. A moderate CCI injury was generated using a TBI impactor (Precision Systems and Instrumentation) armed with a 5 mm blunt end tip at the set velocity of 4 m/sec, a depth of 2.5 mm below the surface of the parietal cortex, dwell time of 250 msec [

35]. A polypropylene ring (approximately 7 mm in diameter, 3.5 mm in height) was secured using acrylic resin (Ortho-Jet BCA, Lang Dental Manufacturing Company, Inc) to frame the craniectomy site and maintain gel positioning. Hydrogels were placed on the top of injured cortex. The incision site was sutured using 4-0 vicryl suture and the rats were recovered.

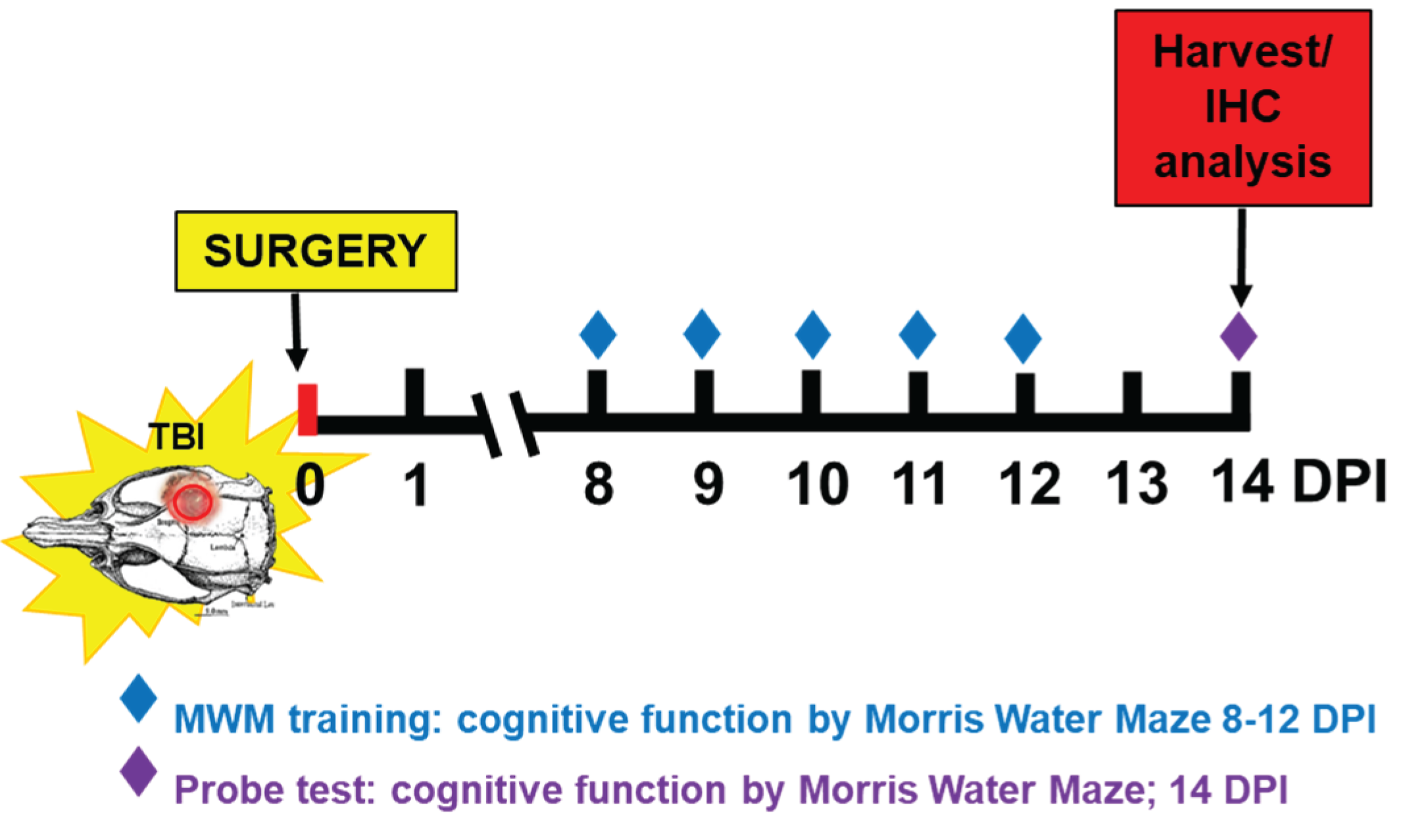

2.3. Cognitive Function by Morris Water Maze (MWM) Test

MWM test was performed from 8 DPI after the incision had healed. MWM test was comprised of 4 trials per day over a 5-day training period with a final “probe test” at 14 DPI (

Scheme 1).

A circular pool (183 cm diameter) filled with water was maintained at 25°C and located in a dimly lit room. Non-toxic black paint, Prang (Dixon Ticonderoga company, FL, USA) was added to the water to make it dark and opaque. To evaluate spatial learning and memory function, visual cues are placed around the pool within the line of sight of the rats. A circular platform (15 cm diameter) was placed in a fixed location in the pool (south-west quadrant, SW) and submerged 2 cm below the water surface. Training began at 8 DPI and were continued for 5 consecutive days (4 acquisition trials/day). For each trial, the rat was released from a randomized starting point (north-west (NW), north (N), north-east (NE), east (E), south-east (SE)) facing the side of the pool. Rats were allowed to find the hidden platform within 60 seconds. If the rat found the platform, the rat would remain on the platform for 10 sec before being placed in its home cage. If the rat failed to find the platform within 60 sec, the rat was guided to the platform and allowed 10 sec to remain on the platform. During the trials, the swim paths were recorded using a video tracking system (SMART, Panlab, Harvard Apparatus) and the searching time to find the platform was recorded. For the probe test, the target platform was removed from the tank and the time required for rats to find platform and stay on the platform 1 second was recorded as a latency time. Video recording and analysis was performed using the PanLab SMART 3.0 software. [

37,

38].

2.4. Tissue Harvest and Histology Preparation

Brain tissue was harvested at 14 DPI after MWM test. Before sacrifice, rats were deeply sedated with an IP injection of EUTHASOL® (150mg/Kg pentobarbital sodium, Virbac, Westlake, TX). A midline thoracotomy was performed, and the rats were transcardially perfused with ice cold 0.9% saline to remove blood followed by cold 4% paraformaldehyde solution (PFA). Brain was isolated and post-fixed in PFA for 24 hours at 4°C. The isolated brains were rinsed using PBS before saturating in increasing concentration of sucrose (10, 20, and 30 % in PBS). Saturated brains were stored in 4°C until ready for sectioning. Cryosectioning was performed on a Leica CM cryostat (CM1950, Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). Brains were removed from 30% sucrose and rinsed in PBS before embedded in TrekTissue OCT compound (Fisher HealthCare, REF 4585, Huston, TX). Tissue was flash frozen in Freeze-It (Fisher Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and allowed to be at -20°C for two hour before sectioning. Coronal sections were made at 30 µm thickness and stored in cryoprotectant (30% sucrose, 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone, and 30% ethylene glycol in 1X PBS) at -20 °C until ready for histological analysis.

2.5. Histological Analysis

2.5.1. Lesion Volume Analysis

Lesion volume was determined using Nissl staining of sequential sections at 0.36 mm intervals within the lesion. Brain sections were washed in three changes of 0.1 M PBS, mounted on charged slides, and left to air dry overnight. The next day sections washed in two changes of DI H

2O before stained in 1% cresyl violet for 5 minutes. The stained sections were then dehydrated in increased concentrations of alcohol (50, 70, 90 100%) before the tissue was optically cleared in xylene, coverslipped with dibutylphthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX) mounting media (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) and allowed to cure at room temperature. Brightfield images were taken using the 10X objective on a Keyence All-in-One fluorescence microscope (Keyence BZ-X810, Osaka, Japan). Using ImageJ open source software the area of lesion per section was measured and the total volume of the brain lesion was determined using Cavalieri’s equation of approximation [

39].

2.5.2. Inflammatory Response and Astrogliosis by Immunohistochemistry

To evaluate the effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel on macrophage infiltration, astrogliosis, and neuron cell survival at 14 DPI, IHC staining was performed as previously described in our previous publication [

35]. Briefly, sections were identified at the epicenter and +/-0.72 mm, +/-2.44 mm, +/-2.26 mm and +/-2.98 mm to the epicenter (total 9 sections/rat; Normal n= 5; TBI (untreated) n = 9; TBI + PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM n = 8). Free floating sections were washed in three changes of 0.1M PBS before blocking in 0.1% Tween 20 (BP337-500, Fisher Chemical, Waltham, MA), 1% BSA (Rockland antibodies & assays, Limerick, PA), and 4 % normal goat serum (ab7481, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were permeabilized in PBST (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20) before overnight incubation at 4°C in primary antibody solution (PBST with 1% BSA) rocking. Primary antibodies included Anti-GFAP antibody targeting glial fibrillary acidic protein in astrocytes (ab7260, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), Anti-NeuN antibody, clone A60 targeting neuronal cells (MAB 377, Millipore Sigma, Temecula, CA), Anti-Macrophage/monocyte antibody, clone ED1 (MAB1435, Millipore Sigma, Temecula, CA); and ARG1/Arginase 1 Antibody (E-2) (SC-271430, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Double staining was performed with GFAP (1:500 dilution) / NeuN (1:200 dilution) and ED1 (1:200 dilution, monocyte/macrophage marker) / Arg1 (1:250 dilution, M2 phenotype marker). The following day, sections washed in PBST before incubated for 2 hours at room temperature in secondary antibody solution (PBST supplemented with 1 % BSA). Secondary antibodies were AF488 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:250, A-11008, ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and Cy3 conjugated goat anti-mouse (1:200, 115-165-003, Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA). After incubation, the sections were washed with 2 changes of PBST, a final wash with 0.1 M PBS, before coverslipped with VECTASHIELD Vibrance antifade mounting media with DAPI (H-1800, ThermoFisher Scientific, Eugene, OR). Images were taken of the perilesional cortex (using 10X objective) using Keyence BX-810 All- in -One fluorescence microscope. Analysis was performed using ImageJ. ED1

+ and Arg1

+ cells were identified with the DAPI overlay and normalized to area (mm

2). NeuN positive cells were identified using a DAPI overlay and reported as a percentage of DAPI. GFAP expression was analyzed as fluorescent intensity and normalized to the corresponding location on an uninjured brain.

2.5.3. Apoptosis by TUNEL Assay

Apoptotic cells were detected using a ApopTag ® Plus Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis detection kit (S7111, Millipore) for terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end (TUNEL) labeling at 14 DPI (

Scheme 1). Sections were again identified at the epicenter, +/-0.72 mm, +/-2.44 mm, +/-2.26 mm and +/-2.98 mm to the epicenter (total 9 sections/rat) and mounted to silane coated slides (63411-01, Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA). Sections were washed in 3 changes of 0.1 M PBS. Staining for cell death was carried out according to the manufacture’s specifications using material provided in their kit.

Briefly, sections were post-fixed for 5 minutes in pre-cooled (-20°C) ethanol: acetic acid solution (2:1 solution), before washed with PBST 3 changes for 5 minutes each. Sections were treated with the equilibration buffer and incubated with TdT enzyme diluted in primary antibody dilutant (PBST with 1% BSA) solution (7:3 dilution) at 37°C for 1 hour. Following incubation, the sections were submerged in stop/wash buffer for 10 minutes and washed with PBS. The fluorescein-labeled anti-digoxigenin conjugate was applied and allowed to incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature protected from light. The slides were washed in PBS before coverslipped with VECTASHIELD Vibrance antifade mounting media with DAPI (H-1800, ThermoFisher Scientific, Eugene, OR). The perilesional cortex was imaged using a Keyence BX-810 fluorescence microscope with the 10X objective. TUNEL+ identified using the DAPI overlay and results are presented as percent TUNEL+ cells.

3. Results

3.1. PEG-Bis-AA/HA-DXM Improves Cognitive Function

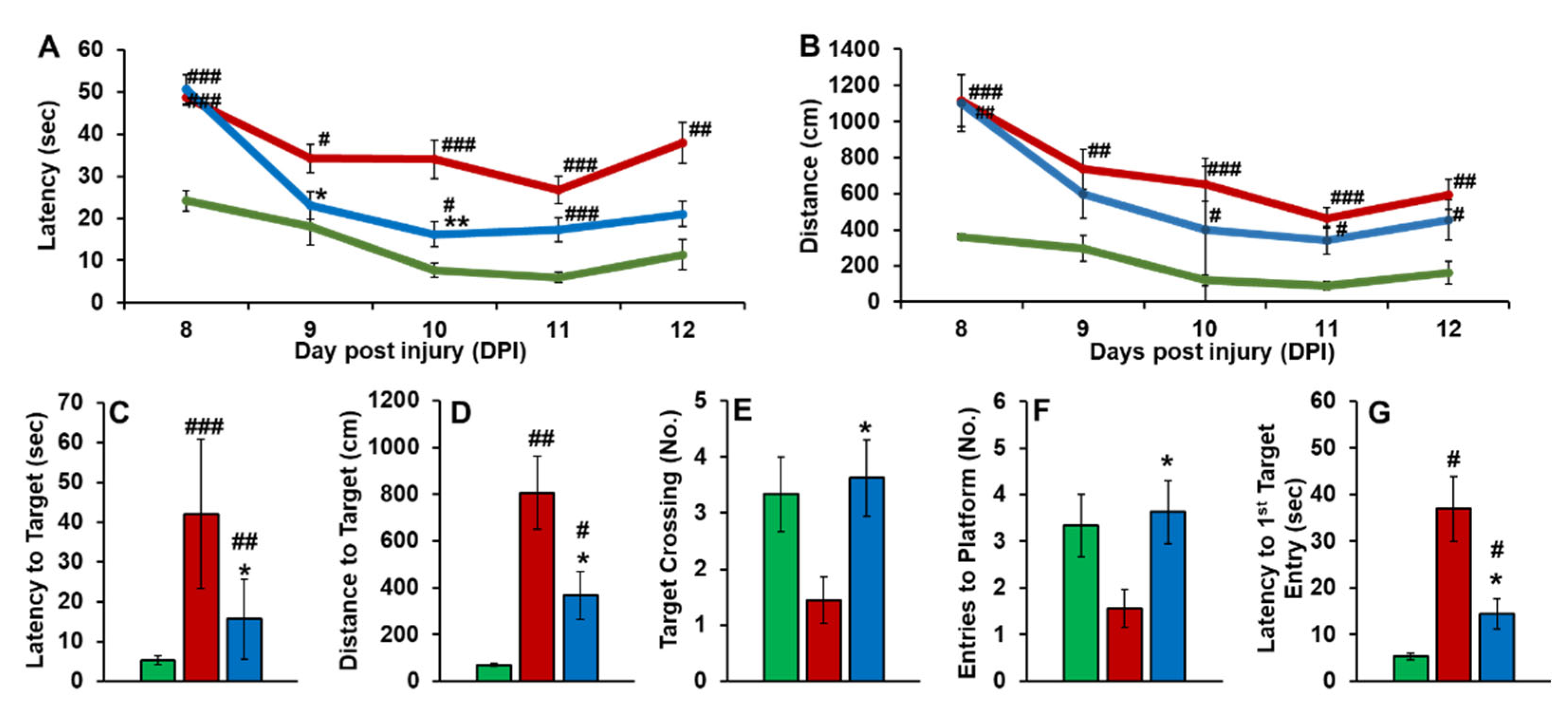

The effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on cognitive function recovery was evaluated by MWM test. During the training days, PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM treated rats showed decreased time to find the hidden target (

Figure 1A) and decreased distance to find hidden target (

Figure 1B) compared to that in untreated TBI group. For the probe test on 14 DPI, PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM treated rats showed significantly shorter latency to target (

Figure 1C), decreased distance to find the hidden target (

Figure 1D), increased number of target crossings (

Figure 1E), increased number of entry to the platform zone (

Figure 1F), and decreased latency to 1st entry of target zone (

Figure 1G) compared to those in untreated TBI rats, respectively.

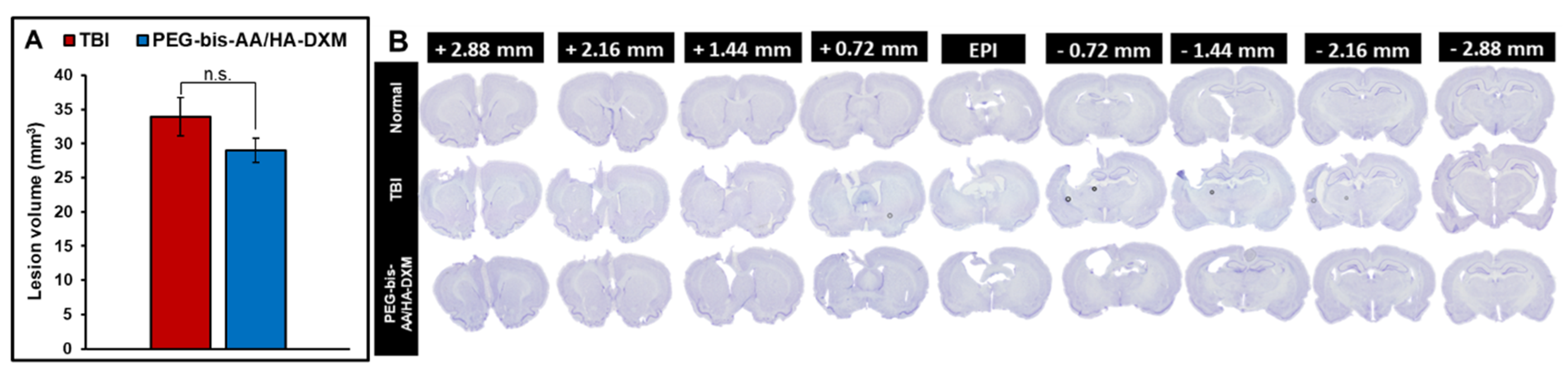

3.2. PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM reduces lesion volume

The effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on lesion volume was determined using cavalier’s formula of approximation based on area of lesion on serial sections. PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment groups showed slightly decreased lesion volume compared to that in TBI untreated group even though it was not significantly different (

Figure 2).

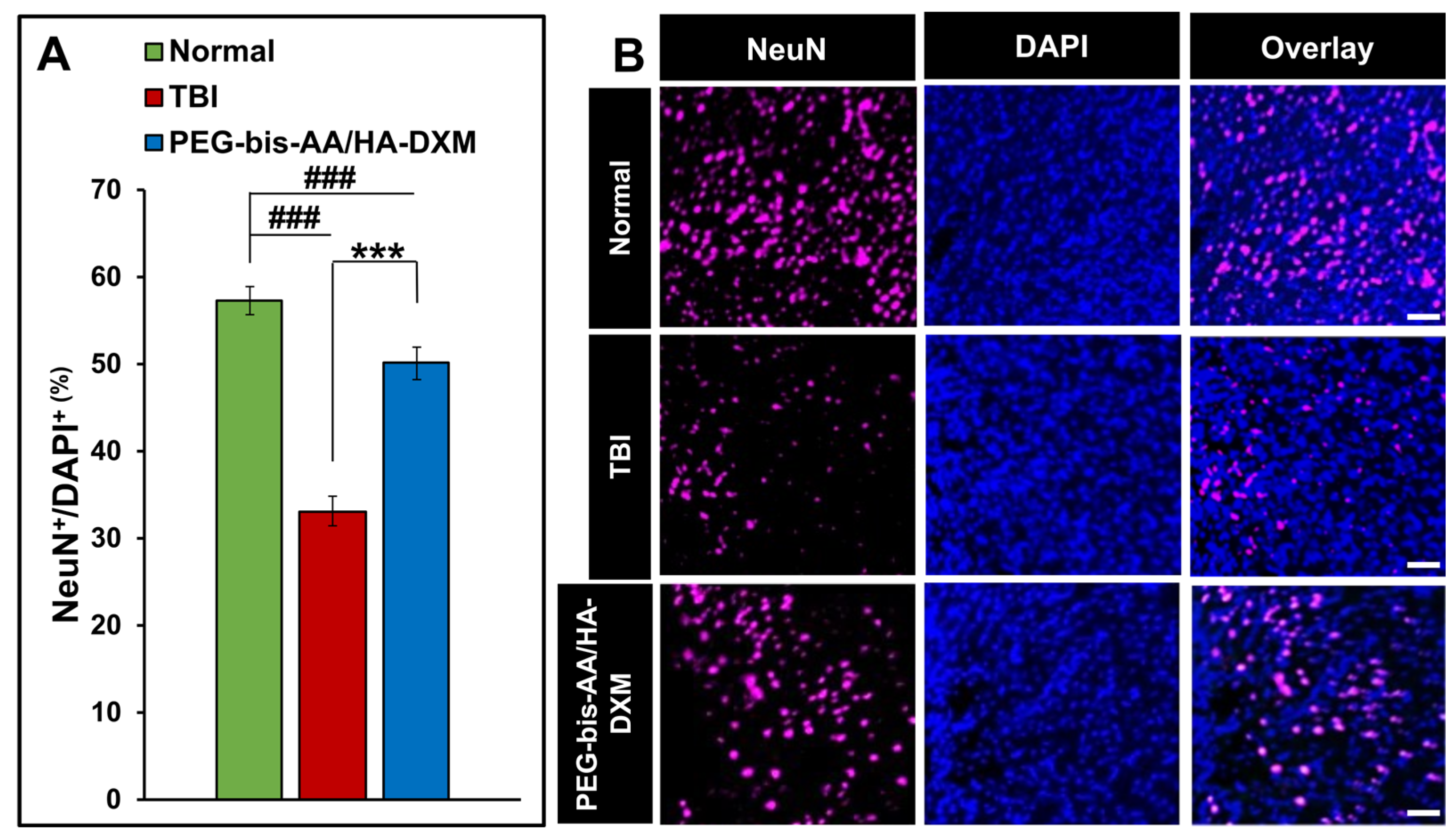

3.3. PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM Improves Neuronal Cell Survival

The effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on neuronal cell survival was evaluated by IHC using antibody against NeuN. The percentage of NeuN

+ cells in PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM treated groups was significantly increased compared to that in untreated TBI group (p <0.001) (

Figure 4A).

Figure 4B shows the representative images of NeuN

+ cells in various groups.

Figure 3.

Effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel on neuronal survival by NeuN staining. A) % NeuN+ cells normalized number of total cells (DAPI+). Data presented mean +/- SEM TBI untreated group (n=9), and PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM gel treated group (n=8); ### p < 0.001 compared to Normal; *** p < 0.001 compared to TBI. B) Representative images of NeuN+ cells in various groups. Scale bar = 500 μm.

Figure 3.

Effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel on neuronal survival by NeuN staining. A) % NeuN+ cells normalized number of total cells (DAPI+). Data presented mean +/- SEM TBI untreated group (n=9), and PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM gel treated group (n=8); ### p < 0.001 compared to Normal; *** p < 0.001 compared to TBI. B) Representative images of NeuN+ cells in various groups. Scale bar = 500 μm.

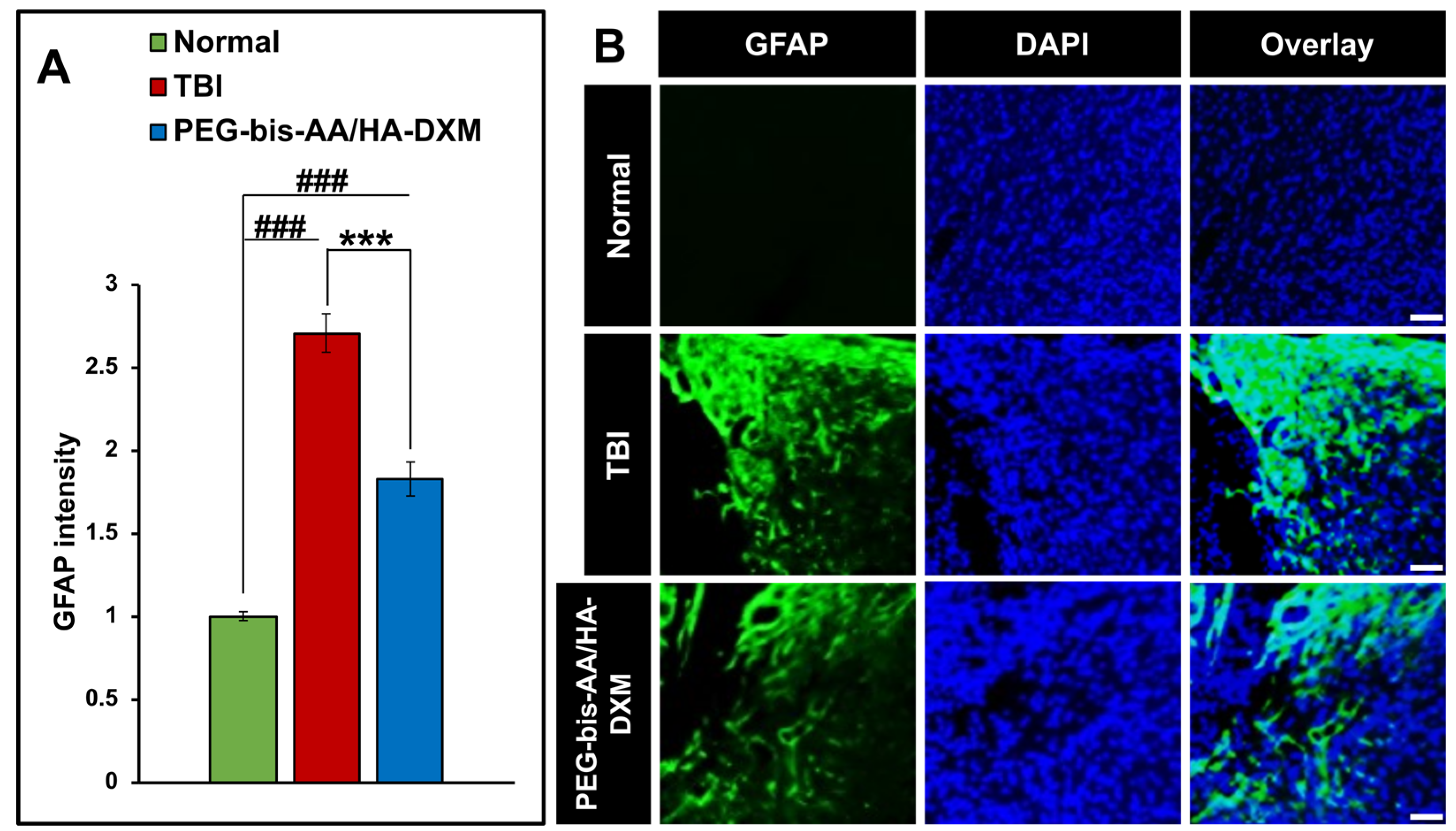

3.4. PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM Reduces Astrogliosis

The effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on astrogliosis was evaluated by intensity of GFAP

+ cells on the stained sections. We observed that PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treated group showed significantly lower intensity of GFAP

+ cells compared to that in the untreated TBI group (

Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel on astrogliosis. A) GFAP intensity normalized to area (mm2). Data presented mean +/- SEM. TBI untreated group (n=9), and PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM gel treated group (n=8); ###p < 0.001 compared to normal; ***p < 0.001 compared to TBI. B) Representative images of GFAP+ cells in various groups. Scale bar = 500 μm.

Figure 4.

Effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel on astrogliosis. A) GFAP intensity normalized to area (mm2). Data presented mean +/- SEM. TBI untreated group (n=9), and PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM gel treated group (n=8); ###p < 0.001 compared to normal; ***p < 0.001 compared to TBI. B) Representative images of GFAP+ cells in various groups. Scale bar = 500 μm.

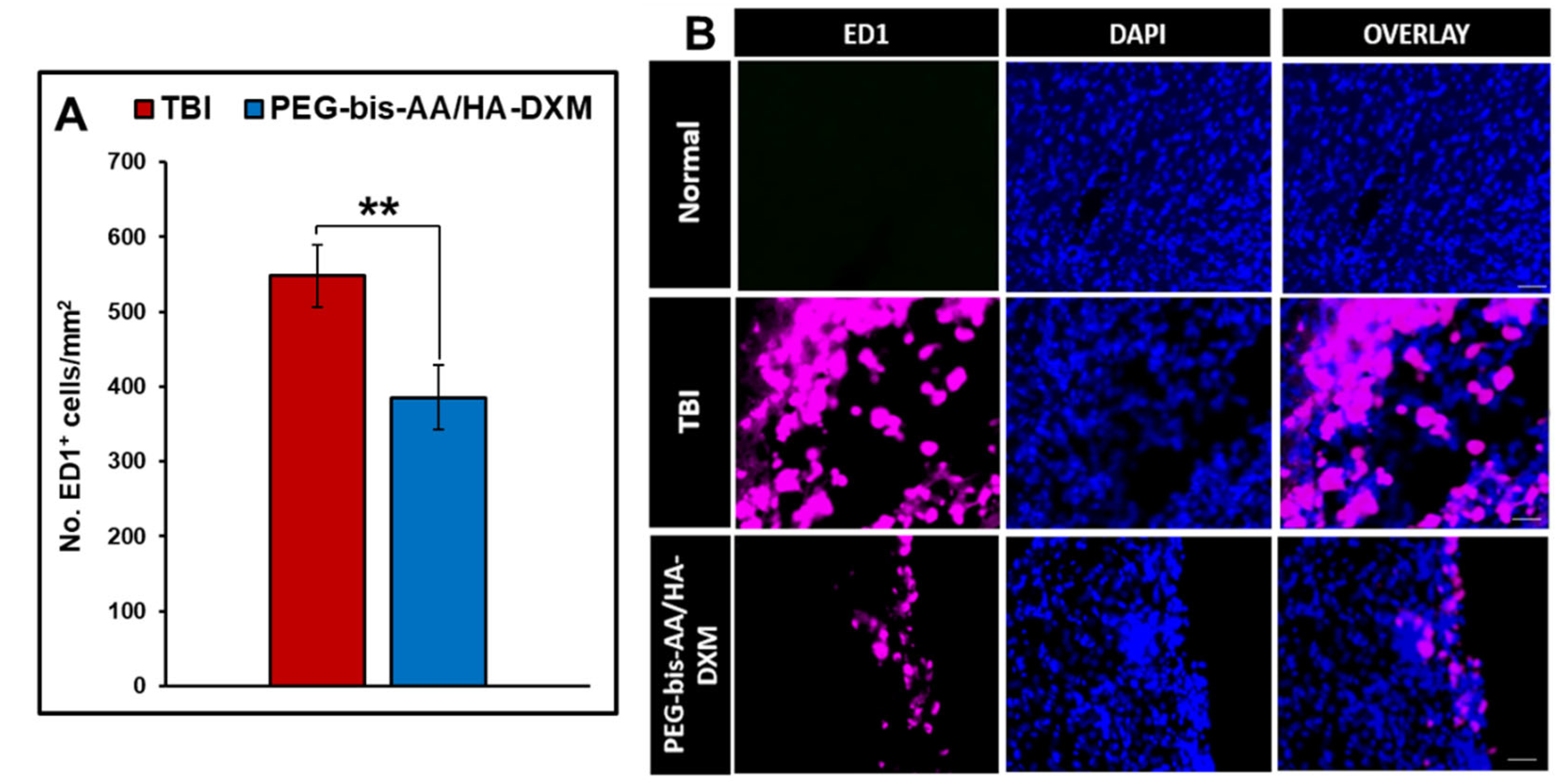

3.5. Effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on Inflammatory Responses

The effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on inflammatory response was evaluated by IHC using antibody against ED1. The number of ED1+ cells in PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treated groups showed significantly decreased compared to that in untreated TBI group (

p < 0.01) (

Figure 5A).

Figure 5B shows representative images of ED1+ cells in various groups.

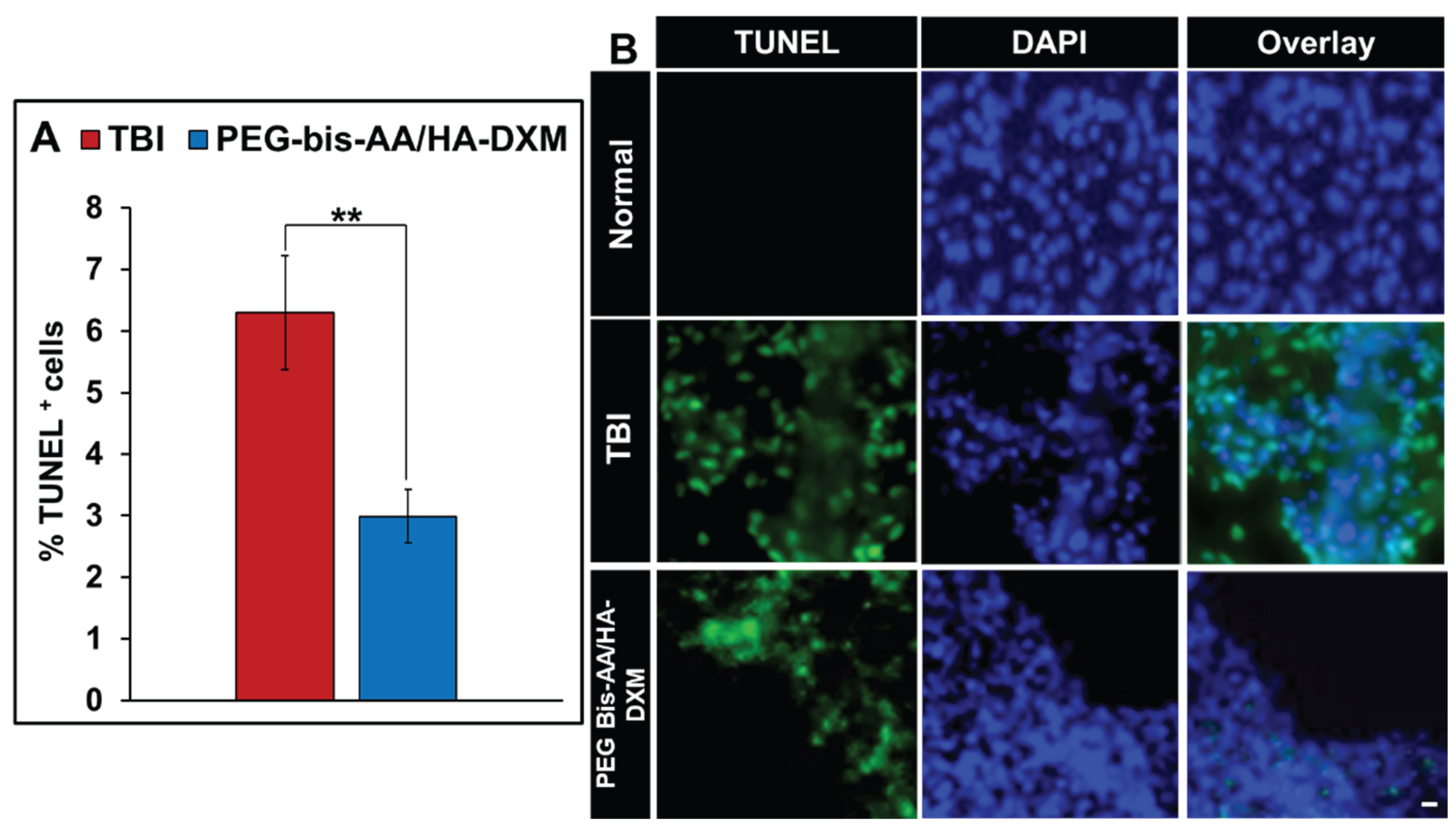

3.6. Effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on Apoptosis

The effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining. The percentages of TUNEL + cells in PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment group was significantly decreased compared to that in untreated TBI group (P<0.01)(

Figure 6A).

Figure 6B shows representative images of TUNEL+ cells in various groups.

4. Discussion

TBI worsens progressively over the time in addition to mechanical primary injury due to secondary injury including edema, inflammation, astrogliosis, oxidative stress, and excitotoxicity. One of major neuronal cell death after TBI is neuroinflammation and many preclinical research focuses on minimizing the damage from the inflammatory reaction [

7,

40]. Glucocorticoid including dexamethasone are potent anti-inflammatory drugs and dexamethasone have showed promising results in decreasing proinflammatory cytokine expression, reducing histological markers for neurotrauma and strengthening the BBB through interaction with tight junction proteins, adherens junction and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in preclinical studies [

29,

30,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Conversely, the high systemic doses of dexamethasone showed a high mortality rate and severe deleterious side effects which has effectively decreased enthusiasm in steroid treatment for TBI in clinical studies [

32]. In addition, other studies using higher dose of DX administered resulted in aggravation of cognitive function impairment by MWM compared to TBI (untreated) [

56,

57] intraperitoneally Zhang et al., treated CCI TBI rats with high dose DX for 7 consecutive days (10 mg/kg for the first three days, 5 mg/kg on day 4, 2 mg/kg on day 5–6 and 1 mg/kg on day 7) and reported that aggravated the neurological and spatial learning impairment induced by TBI [

56]. Chen et al., reported that TBI rats received high dose of DX (0.5–10 mg/kg) showed increase neuronal apoptosis in hippocampus and aggravate retrograde memory deficits induced by TBI [

57].

In our previous published works, we demonstrated that local and sustained delivery of low dose DX (3 ug /rat) by PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel can improve motor and cognitive function and reduce secondary injury in a rat mild CCI TBI model [36, 39]. We also demonstrated that local and sustained delivery of DX by PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel can improve motor function and reduce secondary injury at 7 DPI (acute phase injury) in a rat moderate CCI TBI model ( ref). In this study, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel on cognitive function and secondary injury at 14 DPI (Chronic injury phase) in a rat moderate CCI TBI model. We observed a decrease in latency to target and distance to target in PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment over the training days when compared to TBI untreated. Increased visuospatial pattern recognition decreases latency to target and distance to target indicating a potential increase in recovery in the treatment group [

37]. On 9, 10, and 11 DPI of training the group treated with PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM indicated a faster latency to find hidden platform compared to the TBI untreated group (

Figure 1A). This observation was also seen on 12 DPI (final day of training) when comparing distance traveled between PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treated and untreated rats. During the probe test, hydrogel treatment group had a significantly decreased latency to target and distance to target, and an increase in number of target crossing (

Figure 1C-D). These results are similar to those using this hydrogel treatment in a mild CCI model [

39] and indicated local low dose DX treatment by hydrogel as an effective therapeutic strategy for the TBI repair.

After cognitive function testing at 14 DPI, we investigated the effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM on secondary injury by histological analysis. We first observed that lesion volume was decreased in hydrogel treated group compared to that in untreated TBI group even though it was not significantly different (

Figure 2). In our previous study, we observed a significant decrease in the lesion volume at 7DPI in moderate CCI TBI model [

35]. In our other previous study in a rat mild injury model, we observed that significant decrease in lesion volume at 7 DPI, while a non-significant decrease at 14 DPI [

36,

39]. This indicated the hydrogel treatment may show higher impact in acute phase more than chronic phase.

For the neuronal survival, we observed that hydrogel treated groups showed a significantly higher percentage of NeuN

+ cells compared to that in untreated TBI group (

Figure 3). This suggests a neuroprotective characteristic of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel and this result is consistent with our previous study in a mild CCI TBI model for neuroprotective effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel [

39].

Increased astrocytes activation after injury can lead to glial scar formation that reduce neuronal plasticity and function [

22,

58]. Although there are benefits of gliosis in the acute phase, reducing the global astrocytic activity in acute phases may increase regenerative properties of the tissue long term [

14,

15,

16,

59]. In moderate TBI, astrocyte activity begins to resolve at 14 DPI time point [

22]. The PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treated group showed a significantly reduced fluorescent intensity by GFAP+ cells compared to that in untreated TBI group (

Figure 4). This result was consistent with the results we overserved at 7 DPI in the moderate injury model [

35]. We think that reduction in astrocyte activity in the early days could lead to greater synaptic plasticity in the area that could indicate further recovery or ability to recover functional activity in the tissue.

We also observed the number of ED1

+ cells in the PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment group was significantly lower compared to that in untreated TBI group (

Figure 5). This result is also consistent with our previous study in a mild CCI injury model in which there is a significant decrease in ED1

+ cells at 14 DPI [

39]. We believe that local sustained delivery of low dose dexamethasone by hydrogel can reduce the number of infiltration of macrophages in the lesion site and can be potential therapy for TBI [

10,

12,

64].

Apoptosis is one of key features of secondary injury and continues due to prolonged neuroinflammation [

61,

62,

63]. We evaluated the effect of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on apotosis. We observed that significant decrease in TUNEL

+ cells in PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM treatment group compared to that in the untreated TBI group (

Figure 6). Additionally, this significant decrease was also observed in our previous published studies in which there is a significant decrease in TUNEL

+ cells at 7 DPI time point [

35] in the moderate injury model as well as at 7 and 14 DPI in the mild injury model [

36,

39]. This suggests our PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment has a strong neuroprotective efficacy against the apoptotic pathway after TBI.

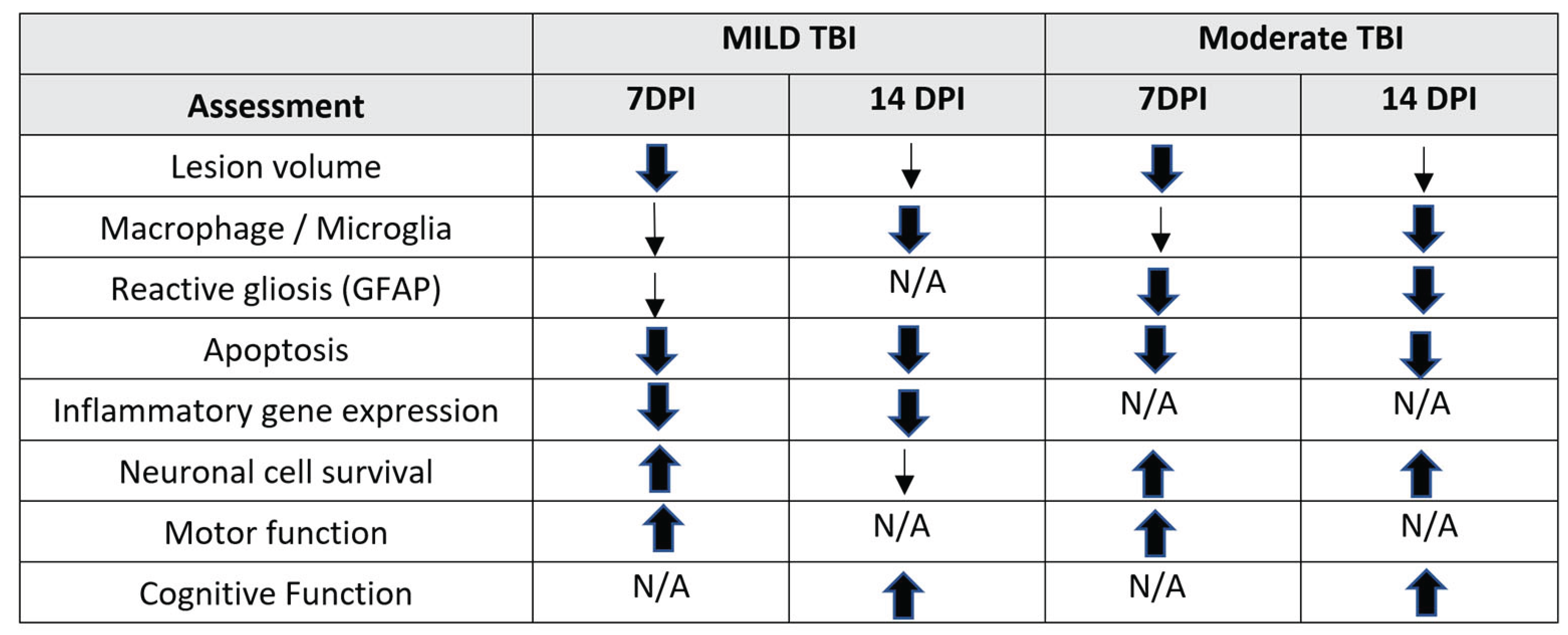

In summary, we observed many benefits of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on increasing neuronal survival, decreasing neuroinflammation, and improving cognitive function recovery in a rat moderate injury model. We also have observed improved motor functional recovery and reduced secondary injury at 7 DPI in a rat moderate injury model [

35]. The key findings of this study and our previous published studies are summarized in Table I. Overall, the results perpetuated the continued interest in the clinical potential of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel for TBI.

Table 1.

Key findings from PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on functional recovery and secondary injury observed in a rat mild and moderate CCI TBI model.

Table 1.

Key findings from PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel treatment on functional recovery and secondary injury observed in a rat mild and moderate CCI TBI model.

5. Conclusions

We observed an increase in cognitive function recovery as determined by MWM test. Through histological analysis, we observed a significant decrease in macrophage infiltration, astrogliosis, apoptosis, and an increase in neuronal survival. These results support previous observations obtained in a rat mild CCI injury model and at 7 DPI in a rat moderate CCI TBI model. These findings support the continued development of PEG-bis-AA/HA-DXM hydrogel as a local sustained treatment of low dose dexamethasone after TBI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J. L. K.W, and D.S.,; methodology, J. L., K.W, and; C.E.J.; validation, J.S.L.; formal analysis, C.E.J, and B.E.; investigation, J. L., K.W, C.E.J., and B.E.; resources, J. L. K.W, A.S., and D.S; data curation, C.E.J., and B.E.; writing—original draft preparation, C.E.J.; writing—review and editing, C.E.J. and J. L.; visualization, C.E.J.; supervision, J. L. and K.W.; project administration, J.S.L.; funding acquisition, J. L., K.W. and D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by US Department of Army and Combat Casualty Care Research Program under award number W81XWH-20-C-0114. This study was partly supported by Bioengineering Center for Regeneration and Formation of Tissues (SC BioCRAFT) Voucher Program at Clemson University funded by NIH/NIGMS P30GM131959.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Research was conducted under an IACUC-approved animal use protocol (animal use protocol 2020-047) at Godley-Snell Research Center of Clemson University, an AAALAC International accredited facility with a Public Health Services Animal Welfare Assurance and in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act and other federal statutes and regulations relating to laboratory animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Mr. Zack Johnson and Ms. Krista Henry for surgical assistance and animal care. Dr. Patrick Gerard, Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, Clemson University for his assistance with statistical analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TBI |

Traumatic Brain Injury |

| DX |

Dexamethasone |

| PEG-bis-AA |

Polyethylene glycol-bis-(acryloyloxy acetate) |

| HA-DXM |

Dexamethasone-conjugated hyaluronic acid |

| CCI |

Controlled cortical impact |

| BBB |

Blood brain barrier |

| GFAP |

Glial fibrillar acidic protein |

| NeuN |

Neuronal nuclei |

| DPI |

Days-post-injury |

| MWM |

Morris water maze |

| IHC |

Immunohistochemistry |

| PBS |

Phosphate buffer saline |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| IACUC |

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| IP |

Intraperitoneal |

| PFA |

Paraformaldehyde |

| DI H2O |

Deionized H2O |

| DPX |

Dibutylphthalate polystyrene xylene |

| BSA |

Bovine serum albumin |

| TUNEL |

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end |

| DAPI |

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

References

- Reekum, R. van; Cohen, T.; Wong, J. Can Traumatic Brain Injury Cause Psychiatric Disorders ? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2000, 12, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.E.; Jaffee, M.S.; Leskin, G.A.; Stokes, J.W.; Felix, O.; Fitzpatrick, P.J. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-like Symptoms and Mild Traumatic Brain Injury. 2007, 44, 895–919. [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, S.; Machamer, J.; Fann, J.R.; Temkin, N.R. Rates of Symptom Reporting Following Traumatic Brain Injury. 2010, 401–411. [CrossRef]

- Masel, B.E.; DeWitt, D.S. Traumatic Brain Injury: A Disease Process, Not an Event. J Neurotrauma 2010, 27, 1529–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, E.A.; Corso, P.S.; Miller, T.R. The Incidence and Economic Burden of Injuries in the United States; 2009; Vol. online edn.

- Carney, N.; Totten, A.M.; O’Reilly, C.; Ullman, J.S.; Hawryluk, G.W.J.; Bell, M.J.; Bratton, S.L.; Chesnut, R.; Harris, O.A.; Kissoon, N.; et al. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery 2017, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, D.; Aisen, M. Traumatic Brain Injury. Handbook of Secondary Dementias 2006, 26, 83–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, T.G.; Puvanachandra, N.; Horner, C.H.; Polito, A.; Ostenfeld, T.; Svendsen, C.N.; Mucke, L.; Johnson, M.H.; Sofroniew, M. V; Site, F.; et al. Leukocyte Infiltration, Neuronal Degeneration, and Neurite Outgrowth after Ablation of Scar-Forming, Reactive Astrocytes in Adult Transgenic Mice. 1999, 23, 297–308.

- Alam, A.; Thelin, E.P.; Tajsic, T.; Khan, D.Z.; Khellaf, A.; Patani, R.; Helmy, A. Cellular Infiltration in Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginhoux, F.; Greter, M.; Leboeuf, M.; Nandi, S.; See, P.; Gokhan, S.; Mehler, M.F.; Conway, S.J.; Ng, L.G.; Stanley, E.R.; et al. Primitive Macrophages. Science (1979) 2010, 701, 841–845. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Alvarez-Croda, D.M.; Stoica, B.A.; Faden, A.I.; Loane, D.J. Microglial/Macrophage Polarization Dynamics Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 2016, 33, 1732–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes Are Induced by Activated Microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.L.; Gallo, V. The Diversity and Disparity of the Glial Scar. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, U.; Li, L.; Pekna, M.; Berthold, C.; Blom, S.; Eliasson, C.; Renner, O.; Bushong, E.; Ellisman, M.; Morgan, T.E.; et al. Absence of Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein and Vimentin Prevents Hypertrophy of Astrocytic Processes and Improves Post-Traumatic Regeneration. 2004, 24, 5016–5021. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J.E.; Imura, T.; Song, B.; Qi, J.; Ao, Y.; Nguyen, T.K.; Korsak, R.A.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Sofroniew, M. V STAT3 Is a Critical Regulator of Astrogliosis and Scar Formation after Spinal Cord Injury. 2008, 28, 7231–7243. [CrossRef]

- Pekny, M.; Johansson, C.B.; Eliasson, C.; Stakeberg, J.; Wallén, Å.; Perlmann, T.; Lendahl, U.; Betsholtz, C.; Berthold, C.; Frisén, J. Abnormal Reaction to Central Nervous System Injury in Mice Lacking Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein and Vimentin. 1999, 145, 503–514.

- Furman, J.L.; Sompol, P.; Kraner, S.D.; Pleiss, M.M.; Putman, E.J.; Dunkerson, J.; Abdul, H.M.; Roberts, K.N.; Scheff, S.W.; Norris, C.M. Blockade of Astrocytic Calcineurin/NFAT Signaling Helps to Normalize Hippocampal Synaptic Function and Plasticity in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Neuroscience 2016, 36, 1502–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, E.J.; Tapanes, S.A.; Loris, Z.B.; Balu, D.T.; Sick, T.J.; Coyle, J.T.; Liebl, D.J. Enhanced Astrocytic D-Serine Underlies Synaptic Damage after Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2017, 127, 3114–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shi, Y.; Pu, H.; Leak, R.K.; Liou, A.K.F.; Badylak, S.F.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Implantation of Brain-Derived Extracellular Matrix Enhances Neurological Recovery after Traumatic Brain Injury. Cell Transplant 2017, 26, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Overexpression of Long Noncoding RNA Malat1 Ameliorates Traumatic Brain Injury Induced Brain Edema by Inhibiting AQP4 and the NF - κ B / IL - 6 Pathway. Journel of Cellular Biochemistry 2019, 17584–17592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, J.; Miller, J.H. Regeneration beyond the Glial Scar. Nat Rev Neurosci 2004, 5, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Iliff, J.J.; Yang, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Chen, M.J.; Giese, R.N.; Wang, B. ‘ Hit & Run ’ Model of Closed-Skull Traumatic Brain Injury ( TBI ) Reveals Complex Patterns of Post-Traumatic AQP4 Dysregulation. 2013, 834–845. [CrossRef]

- Gyoneva, S.; Ransohoff, R.M. Inflammatory Reaction after Traumatic Brain Injury : Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Cell – Cell Communication by Chemokines. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2015, 36, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlosberg, D.; Benifla, M.; Kaufer, D.; Friedman, A. Blood–Brain Barrier Breakdown as a Therapeutic Target in Traumatic Brain Injury. Nature Publishing Group 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.W.; Mcgeachy, M.J.; Bayır, H.; Clark, R.S.B.; Loane, D.J.; Kochanek, P.M. The Far-Reaching Scope of Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourdias, T.; Mori, N.; Dragonu, I.; Cassagno, N.; Boiziau, C.; Aussudre, J.; Brochet, B.; Moonen, C.; Petry, K.G.; Dousset, V. Differential Aquaporin 4 Expression during Edema Build-up and Resolution Phases of Brain Inflammation. 2011, 1–16.

- Akerblom, I.E.; Slater, E.P.; Beato, M.; Baxter, J.D.; Mellon, L.; Akerblom, I.E.; Slater, E.P.; Beato, M.; Baxter, J.D.; Mellon, P.L. Negative Regulation by Glucocorticoids through Interference with a CAMP Responsive Enhancer Published by : American Association for the Advancement of Science Stable URL : Https://Www. Jstor.Org/Stable/1701515 REFERENCES Linked References Are Available On. 2022, 241, 350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Auphan, N.; DiDonato, J.A.; Rosette, C.; Helmberg, A.; Karin, M. Immunosuppression by Glucocorticoids: Inhibition of NF-ΚB Activity through Induction of IκB Synthesis. Science (1979) 1995, 270, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, E.D. High-Dose Glucocorticoid Treatment Improves Neurological Recovery in Head-Injured Mice. J Neurosurg 1985, 62, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spataro, L.; Dilgen, J.; Retterer, S.; Spence, A.J.; Isaacson, M.; Turner, J.N.; Shain, W. Dexamethasone Treatment Reduces Astroglia Responses to Inserted Neuroprosthetic Devices in Rat Neocortex. Exp Neurol 2005, 194, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetker, D.M.; Reh, D.D. A Comprehensive Review of the Adverse Effects of Systemic Corticosteroids. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2010, 43, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P.; Arango, M.; Balica, L.; Cottingham, R.; El-Sayed, H.; Farrell, B.; Fernandes, J.; Gogichaisvili, T.; Golden, N.; Hartzenberg, B.; et al. Final Results of MRC CRASH, a Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial of Intravenous Corticosteroid in Adults with Head Injury— Outcomes at 6 Months. The Lancet 2005, 365, 1957–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, P.; Roberts, I. Corticosteroids in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Br Med J 1997, 314, 1855–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderson, P.; Roberts, I. Corticosteroids for Acute Traumatic Brain Injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Elliott, B.; Liao, Z.; Johnson, Z.; Ma, F.; Bailey, Z.S.; Gilsdorf, J.; Scultetus, A.; Shear, D.; Webb, K.; et al. PEG Hydrogel Containing Dexamethasone-Conjugated Hyaluronic Acid Reduces Secondary Injury and Improves Motor Function in a Rat Moderate TBI Model. Exp Neurol 2023, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, D.U.; Bae, S.; Macks, C.; Whitaker, J.; Lynn, M.; Webb, K.; Lee, J.S. Hydrogel-Mediated Local Delivery of Dexamethasone Reduces Neuroinflammation after Traumatic Brain Injury. Biomedical Materials (Bristol) 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorhees, C. V.; Williams, M.T. Morris Water Maze: Procedures for Assessing Spatial and Related Forms of Learning and Memory. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheff, S.W.; Baldwin, S.A.; Brown, R.W.; Kraemer, P.J. Morris Water Maze Deficits in Rats Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Lateral Controlled Cortical Impact. J Neurotrauma 1997, 14, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macks, C.; Jeong, D.; Bae, S.; Webb, K.; Lee, J.S. Dexamethasone-Loaded Hydrogels Improve Motor and Cognitive Functions in a Rat Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Model. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 11153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, M.A.; Crandall, M.L.; Patel, M.B. Acute Management of Traumatic Brain Injury. Surgical Clinics of North America 2017, 97, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carola, F.; Silwedel, C.; Golenhofen, N.; Burek, M.; Kietz, S.; Mankertz, J.; Drenckhahn, D. Occludin as Direct Target for Glucocorticoid-Induced Improvement of Blood – Brain Barrier Properties in a Murine in Vitro System. 2005, 2, 475–486. [CrossRef]

- Blecharz, K.G.; Drenckhahn, D.; Fo, C.Y. Glucocorticoids Increase VE-Cadherin Expression and Cause Cytoskeletal Rearrangements in Murine Brain Endothelial CEND Cells. 2008, 1139–1149. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, G.A. Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Multiple Roles in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carola, F.; Kahles, T.; Kietz, S.; Drenckhahn, D. Dexamethasone Induces the Expression of Metalloproteinase Inhibitor TIMP-1 in the Murine Cerebral Vascular Endothelial Cell Line CEND. 2007, 3, 937–949. [CrossRef]

- Zeni, P.; Doepker, E.; Topphoff, U.S.; Huewel, S.; Tenenbaum, T.; Galla, H.J. MMPs Contribute to TNF-α-Induced Alteration of the Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier in Vitro. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007, 293, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.; Holloway, J.L.; Stabenfeldt, S.E. Hyaluronic Acid Biomaterials for Central Nervous System Regenerative Medicine. Cells 2020, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, T.C.; Bg, U.; Fraser-, J.R.E. The Structure and Function of Hyaluronan : An Overview. 1996.

- Liu, X.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, S.; Ding, J.; Chen, Z.; Wu, K.; Wu, X.; Zhou, T.; Zeng, M.; et al. Hyaluronan-Based Hydrogel Integrating Exosomes for Traumatic Brain Injury Repair by Promoting Angiogenesis and Neurogenesis. Carbohydr Polym 2023, 306, 120578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, L.A.; Sweeney, T.M.; Redmon, J.; Persing, J.A.; Ogle, R.O.Y.C. Tissue Interactions With Underlying Dura Mater Inhibit Osseous Obliteration of Developing Cranial Sutures. 1993, 198312322.

- TIAN, W.M.; HOU, S.P.; MA, J.; ZHANG, C.L.; XU, Q.Y.; LEE, I.S.; LI, H.D.; SPECTOR, M.; CUI, F.Z. Hyaluronic Acid–Poly-D-Lysine-Based Three-Dimensional Hydrogel for Traumatic Brain Injury. Tissue Eng 2005, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opperman, L.A.; Sweeney, T.M.; Redmon, J.; Persing, J.A.; Ogle, R.O.Y.C. Tissue Interactions With Underlying Dura Mater Inhibit Osseous Obliteration of Developing Cranial Sutures. 1993, 198312322.

- Opperivian, L.A.; Passarelli, R.W.; Morgan, E.P.; Reintjes, M.; Roy, C. Cranial Sutures Require Tissue Interactions with Dura Mater to Resist Osseous Obliteration In Vitro *. 1995, 10, 1978–1987.

- Cooper, G.M.; Durham, E.L.; Cray, J.J.J.; Siegel, M.I.; Losee, J.E.; Mooney, M.P. Tissue Interactions between Craniosynostotic Dura Mater and Bone. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery 2012, 23, 919–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, N.; Haynesworth, S.E.; Caplan, A.I.; Bruder, S.P. Osteogenic Differentiation of Purified, Culture-Expanded Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells In Vitro. J Cell Biochem 1997, 312, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Lee, H.J.; Lee, J.S.; Webb, K. Cell-Mediated Dexamethasone Release from Semi-IPNs Stimulates Osteogenic Differentiation of Encapsulated Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 2757–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, X.; Wang, L.; Hao, S.; Xu, X.; Niu, F.; He, W.; Liu, B. Dexamethasone Impairs Neurofunctional Recovery in Rats Following Traumatic Brain Injury by Reducing Circulating Endothelial Progenitor Cells and Angiogenesis. Brain Res 2019, 1725, 146469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, K.L.; Yang, S.Y.; Dong, J.F.; Zhang, J.N. Glucocorticoids Aggravate Retrograde Memory Deficiency Associated with Traumatic Brain Injury in Rats. J Neurotrauma 2009, 26, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Yang, L.; Lu, B.; Ma, H.F.; Huang, X.; Pekny, M.; Chen, D.F. Re-Establishing the Regenerative Potential of Central Nervous System Axons in Postnatal Mice. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widestrand, Å.; Faijerson, J.; Wilhelmsson, U.; Smith, P.L.P.; Sihlbom, C.; Eriksson, P.S.; Pekny, M. Increased Neurogenesis and Astrogenesis from Neural Progenitor Cells Grafted in the Hippocampus of GFAP / Vim / Mice Increased Neurogenesis and Astrogenesis from Neural Progenitor Cells Grafted in the Hippocampus of GFAP ؊ / ؊ Vim ؊ / ؊ Mice. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-ballester, C.; Mahmutovic, D.; Rafiqzad, Y.; Korot, A.; Lu, P. Mild Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Disruption of the Blood-Brain Barrier Triggers an Atypical Neuronal Response. 2022, 16. [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, J.K.; Zhao, X.; Pike, B.R.; Hayes, R.L. Temporal Profile of Apoptotic-like Changes in Neurons and Astrocytes Following Controlled Cortical Impact Injury in the Rat Temporal Profile of Apoptotic-like Changes in Neurons and Astrocytes Following Controlled Cortical Impact Injury in the Rat. 1999. [CrossRef]

- Holmin, S.; Mathiesen, T. Characterization of Bax and Bcl-2 in Apoptosis after Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury in the Rat. 2003, 281–288. [CrossRef]

- Holmin, S.; Mathiesen, T. Intracerebral Administration of Interleukin-1 β and Induction of Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Vasogenic Edema. J Neurosurg 2000, 92, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisanu, A.; Lecca, D.; Mulas, G.; Wardas, J.; Simbula, G.; Spiga, S.; Carta, A.R. Dynamic Changes in Pro-and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines in Microglia after PPAR-γ Agonist Neuroprotective Treatment in the MPTPp Mouse Model of Progressive Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol Dis 2014, 71, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).