1. Introduction

Immunotherapy is now the method of choice for a great number of cancers, and almost all the techniques employ ability of specific molecules to enhance the anti-tumor response of a patient. Some of such molecules serve as adjuvants that are able to recognize tumor-associated antigens and participate in their presentation by dendritic cells. This function is typical of HSP70 molecular chaperone convincingly proved to elicit antigen-presenting activity leading to the activation of both innate and adaptive immune response [

1,

2]. It is well established that HSP70 or its particular peptides linked to tumor antigens work efficiently in numerous anti-cancer vaccine constructs whose efficacy has been established in pre-clinical and clinical trials [

3,

4,

5]. Notably, pure recombinant HSP70 alone was employed in cell and animal tumor models and demonstrated the ability to generate powerful immune response towards melanoma tumor [

6,

7]. In our studies human recombinant HSP70 was also employed to increase the recognizability of C6 glioblastoma cells in vitro and in vivo [

8] which was probably related to the ability of the chaperone to bind phosphatidylserine component of plasma membrane and penetrate living cells [

9,

10]. It was found that HSP70 entering melanoma and colon cancer cells displaced its intracellular counterpart and expulsed the latter being in soluble or embodied in exosomes; in the latter form HSP70 demonstrated greater immunogenic and anti-tumor activity [

11,

12]. The data prompted us to use instead of free form the protein inserted in plant vesicles obtained from grapefruit which were demonstrated to hold considerable amounts of the active chaperone [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recombinant HSP70 Preparation

Recombinant human HSP70 was purified from

E. coli (strain BL21 DE3) transformed with a pMS-Hsp70 plasmid, as previously described [

14]. The HSP70 solution was further detoxified by incubation with Detoxi-Gel Endotoxin Remover Resin (Thermo Scientific, USA) and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 µm filter (Millipore, USA). According to the E-Toxate assay (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), the level of lipopolysaccharide in the final HSP70 preparation was lower than 0.25 U/mL. The protein concentration was determined using Bradford reagent (BioRad, USA).

2.2. Isolation of Vesicles from Fruit Parts of Citrus x paradisi (Grapefruits) and Loading of Grapefruit-Derived Vesicles with Proteins

For isolation of grapefruit-derived extracellular vesicles (GEV) the sequential ultracentrifugation method was applied as described earlier [

13]. The size of GEVs and their concentration in suspensions were determined by Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) using the NanoSight LM10 (Malvern Instruments) analyzer, equipped with a blue laser (45 mW at 405 nm) and a C11440-5B camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Japan). Recording and data analysis were performed using the NTA software 2.3. The following parameters were evaluated during the analysis of recordings monitored for 60 s: the average hydrodynamic diameter, the mode of distribution, the standard deviation, and the concentration of vesicles in the suspension.

A combination of passive and active cargo loading was used. Recombinant human HSP70 protein at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL was mixed with suspension of GEVs at a final concentration of ~3×1012 particles/mL and incubated overnight at 4°C. Then, the mixture was sonicated at a frequency of 35 kHz for 15 min at RT by the Bandelin SONOREX SUPER ultrasonic bath (Bandelin Electronic GmbH & Co. KG) at room temperature, and incubated for additional 90 min at 4°C. To remove the excess of free protein, the vesicles were purified using ultrafiltration through a 100-kDa filter (Amicon, Millipore) ten times with washing by PBS. The obtained suspension of HSP70-loaded grapefruit vesicles (GEV-HSP70) was adjusted to the starting volume of the initial suspension of GEVs with PBS and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 µm filter (Millipore, USA). The final concentration of loaded GEVs was established by NTA.

The HSP70 protein amount in the samples of GEV-HSP70 was determined by western blotting. The purified samples of GEV-HSP70 were incubated at 4 °C for 30 minutes with 20 µL of lysis buffer (7M urea, 2M thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 1% DTT). The same number (2×10

11) of vesicles isolated from grapefruit (without loading procedure) was analyzed in parallel. The protein samples were diluted in Laemmli buffer (BioRad, USA), subjected to 10 % SDS-PAGE containing 0.1 % SDS, and transferred to the PVDF membrane (Thermo Scientific) using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System (BioRad, USA). Immunoblotting was performed according to the Blue Dry Western protocol [

15]. Mouse monoclonal antibodies to HSP70 (clone 8D1, patent # Ru2722398) were used as primary antibodies at 1:500 dilution. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse polyclonal antibody (CLOUD-CLONE CORP, USA) were used as secondary antibodies at 1:5,000 dilution. Chemiluminescent detection of the protein bands was performed with Clarity Western ECL Blotting Substrate (Bio-Rad, USA) and ChemiDoc System (BioRad, USA). Aliquots of recombinant human HSP70 protein (in range from 0.2 to 2 µg) were used as a positive immunodetection control.

2.3. Cryo-Electron Microscopy

Direct visualization of the grapefruit-derived vesicles and loaded GEVs was performed by Cryo-EM as described previously [

13,

16]. The aqueous solution of the sample was applied on glow-discharged lacey carbon EM grid, which was then plunge-frozen into the precooled liquid ethane with Vitrobot Mark IV (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA). The samples were studied using a cryo-electron microscope Titan Krios 60-300 TEM/STEM (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA), equipped with TEM direct electron detector Falcon II (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) and Cs image corrector (CEOS, Germany) at accelerating voltage of 300 kV. To minimize radiation damage during image acquisition low-dose mode in EPU software (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) was used. The resulting micrographs of GEVs were analyzed using the open-source image analysis and processing program ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA).

2.4. Cells

HCT116 and DLD1 human colon cancer cells were obtained from the Cell Culture Collection, Institute of Cytology of the RAS (St. Petersburg, Russia). Mouse colon carcinoma CT-26 cells were kindly provided by Prof. G. Multhoff (Technical University of Munchen, Germany). Cultured CT-26 cells were stably transfected with pHIV-iRFP720-E2A-Luc plasmid as previously described [

12]. The resulting СT26

iRFP720-E2A-Luc cells expressed near far-red fluorescent protein (ex. 698 nm/em. 720 nm) and luciferase. To assess the activation of the antitumor immune response in vitro, a culture of natural killer (NK) cells was used. NK-92 cells were kindly provided by Dr. Elena Kovalenko (Shemyakin-Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioohganic Chemistry, RAS (Moscow, Russia).

HCT116 and DLD1 cells were cultured in DMEM-F12 (BioLot, Russia) containing 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and CT-26 or CT-26iRFP720-E2A-Luc cells were grown in RPMI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone, USA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (PanEco, Russia) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere with 90% humidity. The number and viability of cells were estimated on a LUNA-II™ Automated Cell Counter (Logos Biosystems, South Korea), after mixing the cell suspension with trypan blue (1:1).

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity assay was performed with the aid of xCELLigence RTCA system (Agilent, USA). This impedance-based assay carries out label-free, real-time high-throughput analysis of cell growth and lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity [

17]. Since NK cells and other lymphocytes are non-adhesive, they do not possess impedance [

17], therefore a change in electrical signal relates only to adherent tumor cells. To evaluate the sensitivity of cancer cells (incubated with soluble recombinant HSP70 or HSP70 in composition of GEVs) to cytotoxic lymphocytes, intact CT-26 mouse colon cancer cells and HCT116 or DLD1 human colon cancer cell were seeded in the wells of an E-plate at concentrations of 5×10

3 cells/well and incubated during 18 h at standard condition. Then HSP70 (50 μg/mL or 5 μg/mL), or the GEVs loaded with recombinant HSP70 (0.5×10

12 GEVs/mL, concentration of loaded HSP70 ~2,5 μg/mL), or GEVs without loading (0.5×10

12 GEVs/mL), were added. 18 h later, effector cells isolated from the spleen of C3HA mice (3×10

5 cells/well) or human NK-92 cells (1×10

6 cells/well) were added with exchange of culture medium and recording was carried out over the next 48 h. Samples were duplicated within each experiment. The experiments were repeated three times.

2.6. Animal Experiments

All in vivo experiments were carried out following the requirements of the Institute of Cytology of Russian Academy of Sciences Ethic Committee (Identification number F18-00380). Male C3HA mice were obtained from the Scientific and Production Enterprise “Nursery of Laboratory Animals” of the Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Pushchino, Russia). BALB/c mice were purchased from Biomedical Technology Research Center (Nizhniy Novgorod, Russia).

Male BALB/c mice were used for subcutaneous CT-26 tumor formation. The mice were divided into 4 groups (18 animal/group) and subcutaneously injected with 2×105 СT26iRFP720-E2A-Luc cells (hereafter referred to as CT-26) per mouse. The cells were previously mixed with: (i) cultural medium (“Untreated” group); (ii) HSP70 (50µg/mouse, “HSP70” group); (iii) GEVs loaded with HSP70 (4 x1011 loaded vesicles/mouse, quantity of loaded HSP70 ~ 2 μg/ mouse, “GEV-HSP70” group); (iiii) GEVs (4 x1011 vesicles/mouse, “GEV” group).

Tumor formation in animals of the experimental groups was assessed every 3 days starting from the eighth day after the injection of CT-26 cells using direct measurement of the tumor node with a caliper. The tumor volume was estimated using the formula: , where L is the length, or the largest dimension, and D is the width, or the smallest dimension.

Tumor growth rate was also estimated by weighing tumors taken from 8 control and treated animals on day 21 after engrafting; blood and spleens were collected on the same day. Tumors were photographed and weighed. Blood plasma was frozen at -80oC before of cytokine measurement by ELISA, while spleens were used immediately. Five random СT26iRFP720-E2A-Luc-injected mice from each group were subjected to bioimaging with the use of the IVIS Spectrum imaging system (Perkin-Elmer, UK) on day 21.

The lifespan of four experimental groups of animals, each consisting of 10 mice, was assessed daily for 3 months, with the fact of death of each animal recorded. Survival curves were established according to the method of Kaplan-Meier and compared using a Mantel-Cox method.

To estimate the specific cytotoxic activity, the splenocytes of mice from all experimental groups were used. For the precise analysis of the total or specific CD8+ cell response, we firstly isolated spleen cells from animals belonging to appropriate treatment groups and further divided each into two groups. One group was incubated with Dynabeads FlowComp™ Mouse CD8 (Invitrogen, USA) to isolate CD8+ cells and the other comprised the total lymphocyte fraction. These cell populations were used as effector cells, which were added to CT-26 cells at a ratio of 100:1. Cell viability was analyzed using the xCELLigence equipment as described above.

The collected blood of 5 animals from each group was centrifuged for 1 hour at 3,000xg at +4°C to obtain blood plasma. The level of cytokines TGFB-1 and IL-10 in the blood plasma of experimental animals was assessed using the ELISA Kit for Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGFb1) (Cloud-Clone Corp., Chine) and ELISA Kit for Interleukin 10 (IL10) (Cloud-Clone Corp, Chine) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All the probes were triplicated.

2.7. Statistics

Visualization and analysis of the obtained data was carried out in GraphPad Prism 9.5.1 software. For multiple comparisons of group means, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test was used. To process data on the survival of experimental animals, the Kaplan-Meier estimate was used. Analysis of the results of western-blotting and Cryo-EM was carried out using freely available software ImageJ. Data are presented as mean ± SD.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Native and HSP70-Loaded GEVs

First, we analyzed particle concentration and size of GEVs as well as their morphology and integrity before and after the loading procedure. Using NTA method we showed that there were no significant changes in the median particle size after loading. Thus, the most common particles had a size of 58±7 nm before and 56±6 nm after the loading (

Figure 1А, B), but the concentration of particles decreased by 1.5-2 times.

The study using Cryo-EM demonstrated that native GEVs have a predominantly spherical shape, surrounded by a lipid bilayer with the average particle size 53±20 nm. Double vesicles and particles with impaired membrane integrity were occasionally encountered (

Figure 1C). The GEV-HSP70 showed the appearance of some contaminants, debris in the sample, as well as an increase in the number of vesicles with impaired integrity. At the same time, the average size of the analyzed particles did not change and was 55 ± 18 nm (

Figure 1D). Thus, using the NTA and Cryo-EM methods it was shown that the loading procedure does not significantly change the overall morphology and size of GEVs.

The loading efficiency of human recombinant HSP70 into GEVs was quantified using WB with anti-HSP70 antibodies (

Figure 1E, F). Lysed GEV-HSP70 in an amount of 10

11 particles/lane were applied to the WB, as well as rHSP70 in an amount from 0.2 μg to 2 μg per lane. Using ImageJ software, we established linear standard curve (R = 0.92), according to the equation of which it was found that 1011 particles contain approximately 0.5 μg of protein. Thus, in all animal experiments, the administered 4×10

11 GEV-HSP70- corresponded to about 2 μg of recombinant HSP70 per dose, and in vitro experiments used approximately 0.5 μg/well, but not more than 1 μg/well of the protein.

3.2. Recombinant HSP70 Loaded into GEVs Effectively Stimulates Immune Cell Activity In Vitro

Recently we have demonstrated that mouse exosomal HSP70 as well as a soluble HSP70 were able to pull out intracellular chaperone on cancer cell surface and activate the cytotoxic response of natural killer (NK) cells [

12]. In this study, we tested the immunomodulatory activity of GEV-HSP70 in several colon cancer models.

At first, to test whether GEV-HSP70 are also capable to sensitize cancer cells to cytotoxic cells we used two human colon carcinoma cells, HCT-116 and DLD1, incubated with GEV-HSP70, in cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) assay using xCELLigence technique. It is shown that the pre-incubation of human colon cancer cells with GEV-HSP70 resulted in to a 2-3-fold reduction of cell index which indicated increase of sensitivity of tumor cells to cytotoxic NK-92 cells (

Figure 2 A, B).

Then we compared the immunomodulatory activity of GEV-HSP70 and HSP70 in mouse CT-26 colon carcinoma cells in vitro. CT-26 cells were preincubated with rHSP70 (10 μg/well), as well as with GEV-HSP70 (10

11 particles/well, containing about 0.5 μg of rHSP70), then naïve lymphocytes obtained from the spleens of C3HA mice (

Figure 2C) or NK-92 cells (

Figure 2D) were added and cytotoxic activity was monitored in real time using the xCELLigence technique. We observed an increase in the toxic effect of СTL both to cells incubated with HSP70 in free form or GEV-HSP70 (

Figure 2C, E). Of note the effect was equal for cells that were co-incubated with free HSP70 (10 μg), the amount of which was 20 times higher than in GEV-HSP70 (about 0.5 μg of HSP70). Similar result was obtained when NK-92cells were used. The effect of natural killer cells was observed after 10 hours of co-incubation, and cell survival decreased by 50% (

Figure 2D, F). To test the assumption that accumulation of rHSP70 in mouse cells is more efficient when the protein is encapsulated in vesicles, free rHSP70 was also previously added to the cells in an amount of 1 μg, which approximately corresponds to its content in GEV-HSP70 samples. It was shown that the amount of free HSP70 comparable to that loaded in GEVs does not lead to NK cell activation, as do unloaded GEVs (

Figure 2D, F).

Thus, we have shown that the addition of HSP70 in free form and as part of GEVs increases the sensitivity of human (HCT-116, DLD1) or mouse (CT-26) colon cancer cells to mouse cytotoxic lymphocytes and human NK-92 cells. Moreover, as part of GEVs, HSP70 caused activation of antitumor immunity as compared with the amount of protein that was 20 times less than when added in free form.

3.3. Antitumor Effect of HSP70 and GEV-HSP70 in a Mouse Model of Colorectal Cancer

Next, we analyzed the effect of GEV-HSP70 on the tumor growth of СT-26 cells in vivo. A single administration of the GEV, GEV-HSP70 (2 μg HSP70/dose) and HSP70 (50µg) was used at the same time as tumor cells were inoculated subcutaneously to male Babl/c mice.

For three weeks after inoculation of tumor cells, either intact or in the presence of GEV, HSP70, or GEV-HSP70, we have measured the volume of growing tumors. We observed a delay in tumor growth in the “HSP70” and ‘GEV-HSP70’ groups; their average size on the last day of measurement was significantly lower from the size in the “Untreated” group or in the “GEV” group (2.0 ± 0.2 for “GEV-HSP70” or 1.0 ± 0.4 for “HSP70” groups vs 3.4 ±0.6 and 2.7 ±0.4 cm3 for “Untreated” and “GEV” groups respectively) (

Figure 3A).

Then tumors from eight animals from each group were isolated (

Figure 3B) and weighed (

Figure 3C). Again, the weight of tumors from the “Untreated” group or from the “GEV” group varied signifficantly from the “HSP70” and “GEV-HSP70” groups (0.5 ± 0.3 and 0.5 ± 0.2 g for “GEV-HSP70” and “HSP70” respectevly vs 1.1 ±0.4 and 0.9 ±0.3 g for “Untreated” and “GEV” groups respectevly). It was also shown that the average tumor luminiscence in “GEV-HSP70” was 4.0-fold less than in “Untreated” group and 5.8-fold less than in “GEV” group. The luminescence of tumors from the “HSP70” group was not statistically different from that in the “GEV-HSP70” group (

Figure 3D, E).

Animal survival of ten remainig mice in each group was monitored over a 90-day period, which showed a 3-fold increase in lifespan for animals in the “HSP70” and “GEV-HSP70” groups compared to the control groups (

Figure 3F). The average life span in the two control groups, “Untreated” and “GEV”, was 32.3 ± 5.4 and 29.8 ± 4.8 days respectively while in the “GEV-HSP70” and “HSP70” groups, 3 mice in each group survived the observation time (90 days) and the remaining had average lifespan 42.2 ±9.6 and 45.9 ±9.0 days.

The data obtained indicate that the delivery of HSP70 into CT-26 tumor cells as part of grapefruit vesicles leads to a decrease in the tumor growth as well as, tumor weight or size, as well as an increase in the life expectancy of experimental animals compared to the control group with the same efficiency, as free rHSP70 in 25-fold exceeding quantities.

3.4. The Antitumor Effect of HSP70 and GEV-HSP70 in a Mouse Model of Colon Carcinoma Is Due to the Activation of a Specific Immune Response

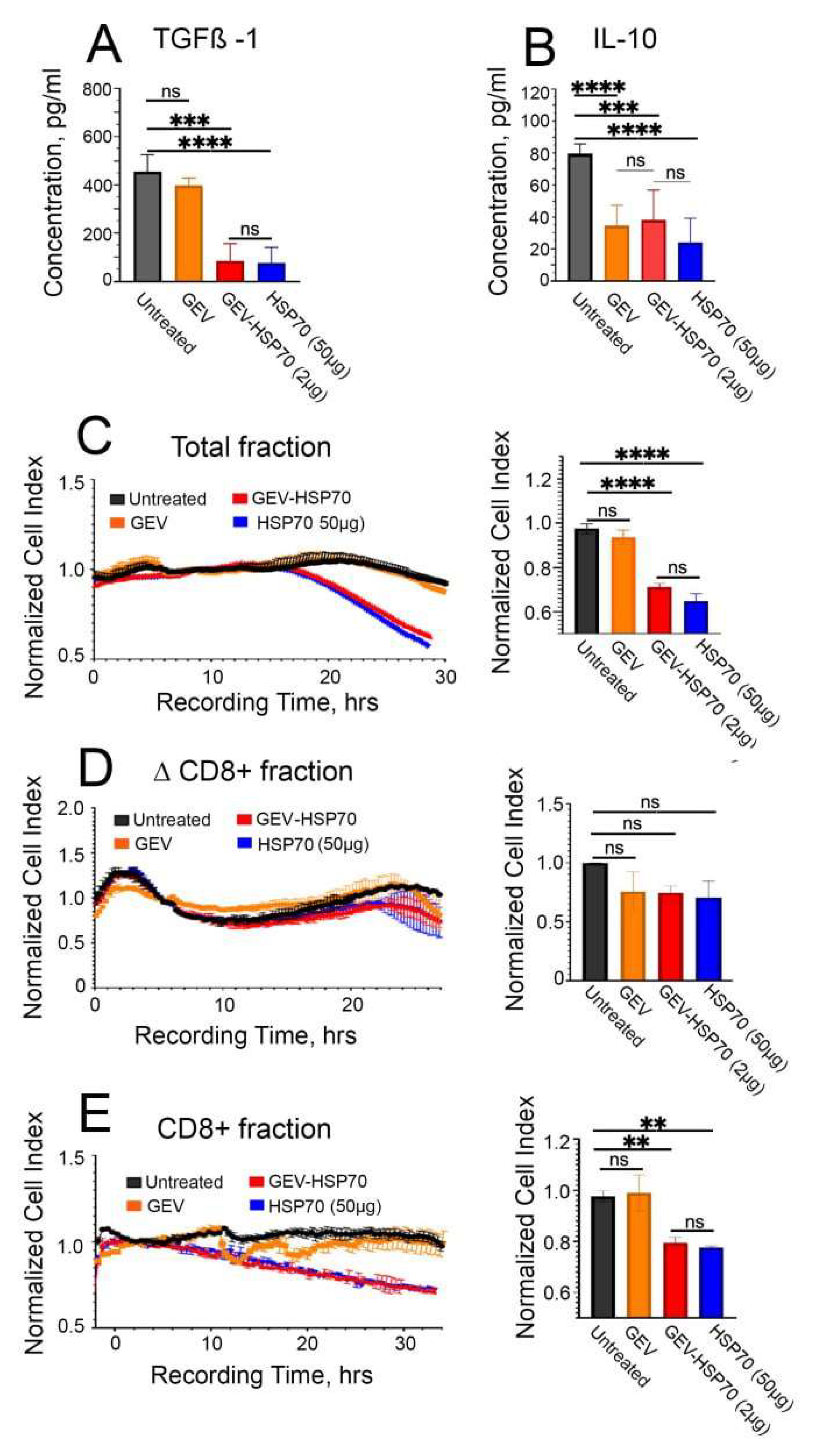

To analyze if the immune response possibly stimulated in animals by HSP70 administration, blood samples were collected on the 21 day of tumor growth, followed by ELISA assay for TGFβ-1 and IL10. It was shown that in the blood of mice of the “HSP70” and “GEV-HSP70” groups, there was a significant reduction in the levels of IL-10 and TGFβ-1 compared to the “Untreated” group (

Figure 4A, B). It is also worth noting that the in “GEV” group we observed 2-fold decrease in the level of pro-inflammatory IL-10 in the blood.

In order to further verify that the observed in vivo antitumor effects are related to the activation of a specific immune response, the proliferative activity of CT-26 cells was assessed during their co-incubation with the total fraction of lymphocytes obtained from the spleens of mice of experimental and control groups, as well as during co-cultivation of CT-26 cells with a fraction of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes obtained from the total lymphocyte fraction using the DynabeadsFlowComp™ Mouse CD8 kit. Cell viability and proliferative activity were assessed using the xCellLigence system. It was shown that after the addition of total lymphocytes or CD8+ T cells, obtained from HSP70 or GEV-HSP70 groups of mice CT-26 cell viability was reduced by 30% and 20%, respectively (

Figure 4C, E). Lymphocyte fractions depleted of CD8+ cells, for which no stimulatory or cytotoxic effect was observed, were also used as a control (

Figure 4D). The data obtained indicate that specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes are involved in the observed in vivo antitumor effect of HSP70, both in free form and loaded into GEVs.

4. Discussion

Multifaceted function of HSP70 chaperone in tumor growth and immune response to cancer is well established and there are hundreds of publications dedicated to this topic [

18]. In addition to its protective activity HSP70 was shown to leave cancer cells or enter them; when occurring exogenously HSP70 by binding tumor antigens or variety of other polypeptides is able to regulate immune response to cancer cells by triggering the mechanisms of innate and adaptive immunity [

2].

HSP70 releases from tumor cells in free form or within extracellular vesicles (EV) [

2,

19]. HSP70-containing EVs or exosomes strongly affect tumor progression by promoting activity of Tregs or inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells, which help the tumor to avoid immune surveillance [

20,

21]. On the contrary, the antitumor activity of HSP70-bearing EVs from heat-treated CT-26 and B16 melanoma cells was demonstrated, which was associated with the enhancement of strong Th1 immune response [

4]. Additionally, the strong anti-tumor effects of exosomes from mouse colon carcinoma MC38 cells was accompanied by the conversion of regulatory T cells into Th17 cells [

22]. Our earlier data demonstrated that EVs from tumor cells loaded with HSP70 caused high antitumor immune responses in mouse B16 melanoma and CT-26 colon carcinoma-bearing mice, activating CD8+ dependent immune response [

12]. Taking into account that tumor exosomes may be dangerous to apply as a therapeutic agent, we loaded grapefruit vesicles with pure HSP70 and found that they efficiently activated innate pro-tumor immunity to colorectal cancer cells in vitro and slowed down tumor growth and increased the survival of tumor-bearing animals in vivo, stimulating specific anti-tumor CD8+ dependent immunity, which was accompanied by a reduction in the amount of pro-tumor cytokines, TGFβ-1 and IL-10.

5. Conclusions

Summarizing the results of all experiments performed, we can conclude that the HSP70 protein activates the antitumor immune response in models of colorectal cancer, both in vitro and in vivo. Recombinant HSP70 protein can be loaded into grapefruit vesicles while maintaining its functionality. Moreover, in both cell and animal models, HSP70 in the composition of GEVs has the same antitumor effect as a 20-fold greater amount of the chaperone in its free form.

Author Contributions

Methodology, L.G., E.K. and B.M.; validation, L.G. and E.K.; formal analysis, L.G.; investigation, L.G., E.K., S.E. and E.P.; writing - Original Draft, L.G., I.G., T.S.; data curation, E.K.; visualization, S.E.; supervision, A.K., B.M., I.G. and T.S.; funding acquisition, A.K. and T.S.; conceptualization, B.M., I.G. and T.S.; writing - review and editing, B.M., I.G. and T.S.; project administration, I.G. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation project 19-74-20146-p (cryo-ЕМ, NTA, cell culture experiments). This work was partially (animal experiments) supported by Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the RF (Project 075-15-2021-1360).

Acknowledgments

We thank Eugeniy Yastremskiy and Roman Kamyshinsky for an assistant with cryo-ЕМ experiments. We also thank Anastasia Nikitina for her assistance in conducting experiments using laboratory animals. The authors acknowledge the support and the use of resources of the Resource Center for Probe and Electron Microscopy at the NRC “Kurchatov Institute”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Author 1, A.B.; Author 2, C.D. Title of the article. Abbreviated Journal Name Year, Volume, page range Cuzzubbo S. et al. Cancer Vaccines: Adjuvant Potency, Importance of Age, Lifestyle, and Treatments. Front. Immunol 2021, Volume 11. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; et al. Diversity of extracellular HSP70 in cancer: advancing from a molecular biomarker to a novel therapeutic target. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noessner, E.; et al. Tumor-Derived Heat Shock Protein 70 Peptide Complexes Are Cross-Presented by Human Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5424–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho J. et al. MHC independent anti-tumor immune responses induced by Hsp70-enriched exosomes generate tumor regression in murine models. Cancer Lett. 2009, Volume 275, № 2, page 256–265. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; et al. Multi-chaperone-peptide-rich mixture from colo-carcinoma cells elicits potent anticancer immunity. Cancer Epidemiol 2010, Volume 34, № 4 page 494–500. [CrossRef]

- Ito A. et al. Antitumor effects of combined therapy of recombinant heat shock protein 70 and hyperthermia using magnetic nanoparticles in an experimental subcutaneous murine melanoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 2004, Volume 53, № 1, page 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Geng H. et al. HSP70 vaccine in combination with gene therapy with plasmid DNA encoding sPD-1 overcomes immune resistance and suppresses the progression of pulmonary metastatic melanoma. Int. J. Cancer 2006, Volume 118, № 11. page 2657–2664. [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov M.A. et al. Effective immunotherapy of rat glioblastoma with prolonged intratumoral delivery of exogenous heat shock protein Hsp70. Int. J. Cancer 2014 Volume 135, № 9, page 2118–2128. [CrossRef]

- Schilling D. et al. Binding of heat shock protein 70 to extracellular phosphatidylserine promotes killing of normoxic and hypoxic tumor cells. FASEB J. 2009, Volume 23, № 8, page 2467–2477. [CrossRef]

- Abkin S. V. et al. Hsp70 chaperone-based gel composition as a novel immunotherapeutic anti-tumor tool. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013 Volume 18, № 3. page 391–396. [CrossRef]

- Shevtsov M.A. et al. Exogenously delivered heat shock protein 70 displaces its endogenous analogue and sensitizes cancer cells to lymphocytes-mediated cytotoxicity. Oncotarget 2014, Volume 5, № 10, page 3101–3114. [CrossRef]

- Komarova E.Y. et al. Hsp70-containing extracellular vesicles are capable of activating of adaptive immunity in models of mouse melanoma and colon carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2021, Volume 11, № 1, page 21314. [CrossRef]

- Garaeva L. et al. Delivery of functional exogenous proteins by plant-derived vesicles to human cells in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2021, Volume 11, № 1, page, 6489. [CrossRef]

- Guzhova I. V. et al. Novel mechanism of Hsp70 chaperone-mediated prevention of polyglutamine aggregates in a cellular model of huntington disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, Volume 20, page. 3953–3963. [CrossRef]

- Naryzhny S.N. Blue Dry Western: Simple, economic, informative, and fast way of immunodetection. Anal. Biochem. 2009 Volume 392, page 90–95. [CrossRef]

- Emelyanov A. et al. Cryo-electron microscopy of extracellular vesicles from cerebrospinal fluid. PLoS One. 2020, Volume 15. [CrossRef]

- Peper J.K, et al. An impedance-based cytotoxicity assay for real-time and label-free assessment of T-cell-mediated killing of adherent cells. J. Immunol. Methods. 2014, Volume 405, page 192–198. [CrossRef]

- Mazurakova A. et al. Heat shock proteins in cancer – Known but always being rediscovered: Their perspectives in cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Med. Sci. 2023, Volume 68, № 2. page 464–473. [CrossRef]

- Elmallah M.I.Y. et al. Membrane-anchored heat-shock protein 70 (Hsp70) in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020, Volume 469 page 134–141. [CrossRef]

- Chalmin, F.; et al. Membrane-associated Hsp72 from tumor-derived exosomes mediates STAT3-dependent immunosuppressive function of mouse and human myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao J. et al. Exosomal Hsp70 mediates immunosuppressive activity of the myeloid-derived suppressor cells via phosphorylation of Stat3. Med. Oncol. 2015, Volume 32, № 2, page 35. [CrossRef]

- Guo D. et al. Exosomes from heat-stressed tumour cells inhibit tumour growth by converting regulatory T cells to Th17 cells via IL-6. Immunology. 2018 Volume 154, № 1, page 132–143. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).