Submitted:

26 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

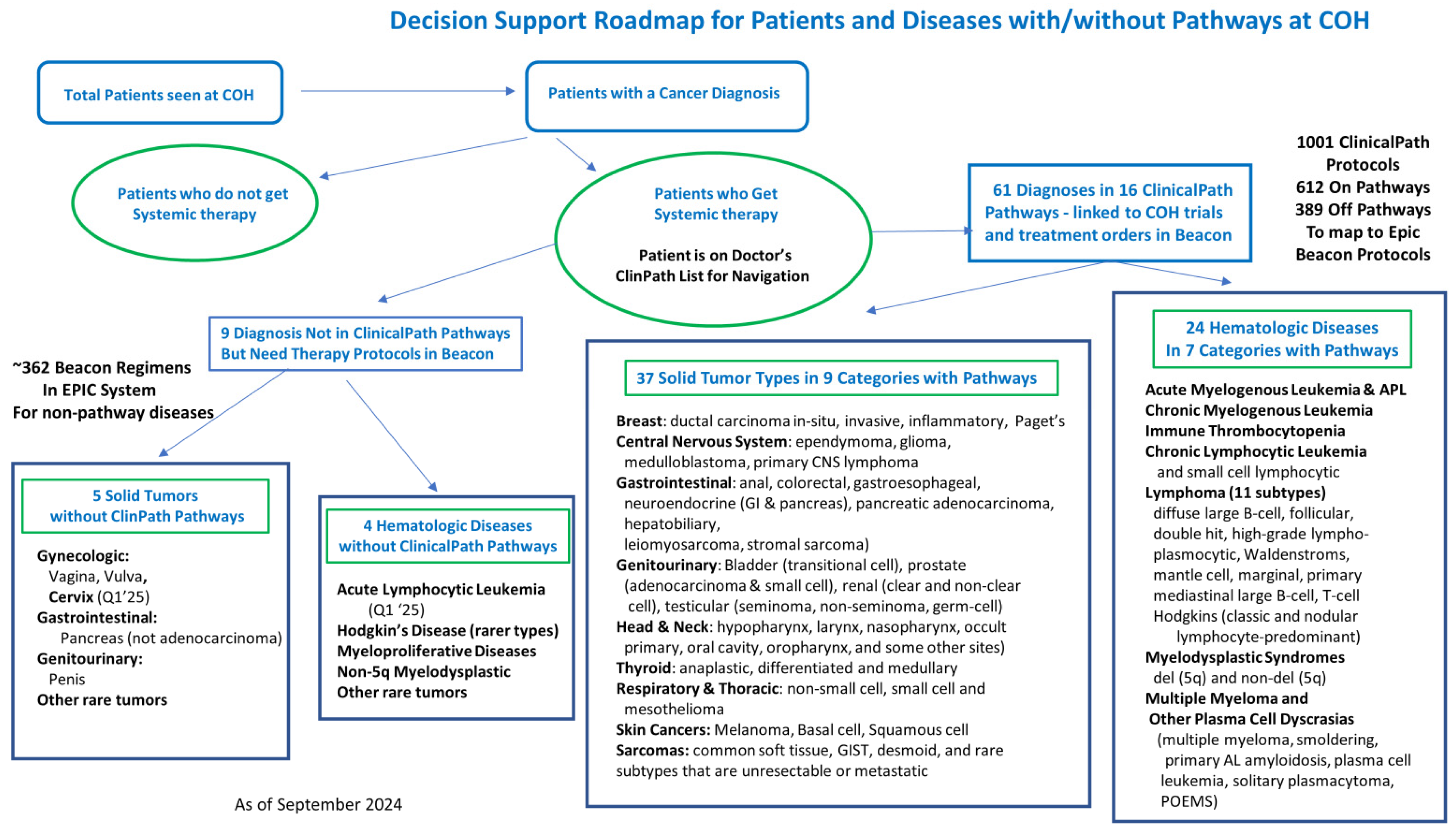

3.1.1. Enterprise Pathways and Protocols Program Development:

- Program Leadership: Our executive sponsor is our Chief Clinical Officer. He appointed a medical director who co-leads the program with the program’s clinical pharmacist. They work with the program manager as a core team. They actively interact with the clinical pharmacy, IT, ClinicalPath, Beacon leadership, department chairs, faculty, and nursing leadership.

- Program charter codified the membership, meetings, objectives, reporting structure, scope of work, and deliverables. The core team developed the charter, which was reviewed and approved by the medical oncology, hematology, and radiation oncology departments and the governance committee.

- A Governance Committee was formed with multidisciplinary stakeholders across the enterprise. They meet quarterly and oversee pathway and Beacon protocol policies, standardize Beacon order components, update antiemetic guidelines, ensure regulatory compliance, support resources to meet the program goals, and review analytics to document our high-quality care.

-

Disease Teams were formed for each disease or disease subtype at the preference of the disease lead and department chairs. The teams are led by an academic faculty member appointed by the department chair. They consist of a clinical pharmacy and nursing disease expert, as well as any interested faculty across the enterprise who wants to attend. Attendance from physicians, APP, nursing, and pharmacy representatives from the CA community, CAP sites, and the Duarte and Irvine academic sites is welcomed. Epic Beacon and IT staff are encouraged to attend as well. COH has disease teams for pathway and non-pathway diseases as follows:

- ▪

-

Solid Tumors:

- Breast, GU, GI by subtype, Gynecology, Head and Neck, Lung, Melanoma and Skin, Brain, Sarcoma and Soft tissue, Thyroid

- ▪

-

Hematology:

- Lymphoma by subtype, ITP, Myelodysplasia/myeloproliferative, Myeloma and plasma cell diseases, CML, AML, ALL, CAR-T, BMT.

- Overseeing Beacon protocol builds, identifying and prioritizing builds

- Providing content for regimen builds, validating builds when done, and sending to COH’s P&T committee for final approval before going live in Epic

- Reviewing ClinicalPath updates and any pathway issues

- Reviewing COH clinical trials in the ClinicalPath system

- Regulatory review of Beacon orders biannually

- Reviewing any analytics of interest on pathway choices and clinical trial accruals

3.2.1. Establishing Standard Components for Beacon Protocols for the City of Hope Enterprise

3.3.1. Current State Gap Analyses and Time Impact Surveys

-

Gap Analysis and prioritization for missing protocols was performed to determine the number of Beacon orders missing from our Epic system. City of Hope’s Epic system has 1100 Beacon protocols built. Built protocols were matched against the 612 on pathway regimens in the ClinicalPath system as of April 2024. This matching identified 326 regimens missing from the current Beacon protocol builds. These 326 regimens were divided into their respective disease pathways. The disease leads and pharmacists were then surveyed to determine the usage frequency to prioritize getting them built. The prioritization criteria were divided into four categories based on order frequencies: priority 1: once every 1-4 weeks; priority 2: 1-3 months; priority 3: 4-12 months; or priority 4, rare or not currently used. This resulted in 36 priority 1, 75 priority 2, 89 priority 3 beacon protocols, and 126 noted to be used rarely or not needed. Results are shown in Table 3.Table 3. Survey Results of Prioritization of ClinicalPath associated Beacon protocol builds.

Priority by usage frequency Number of regimens (n=326) 1-Use once every 1-4 weeks 36 2-Use once every 1-3 months 75 3-Use once every 4-12 months 89 4-Not currently or rarely used 126

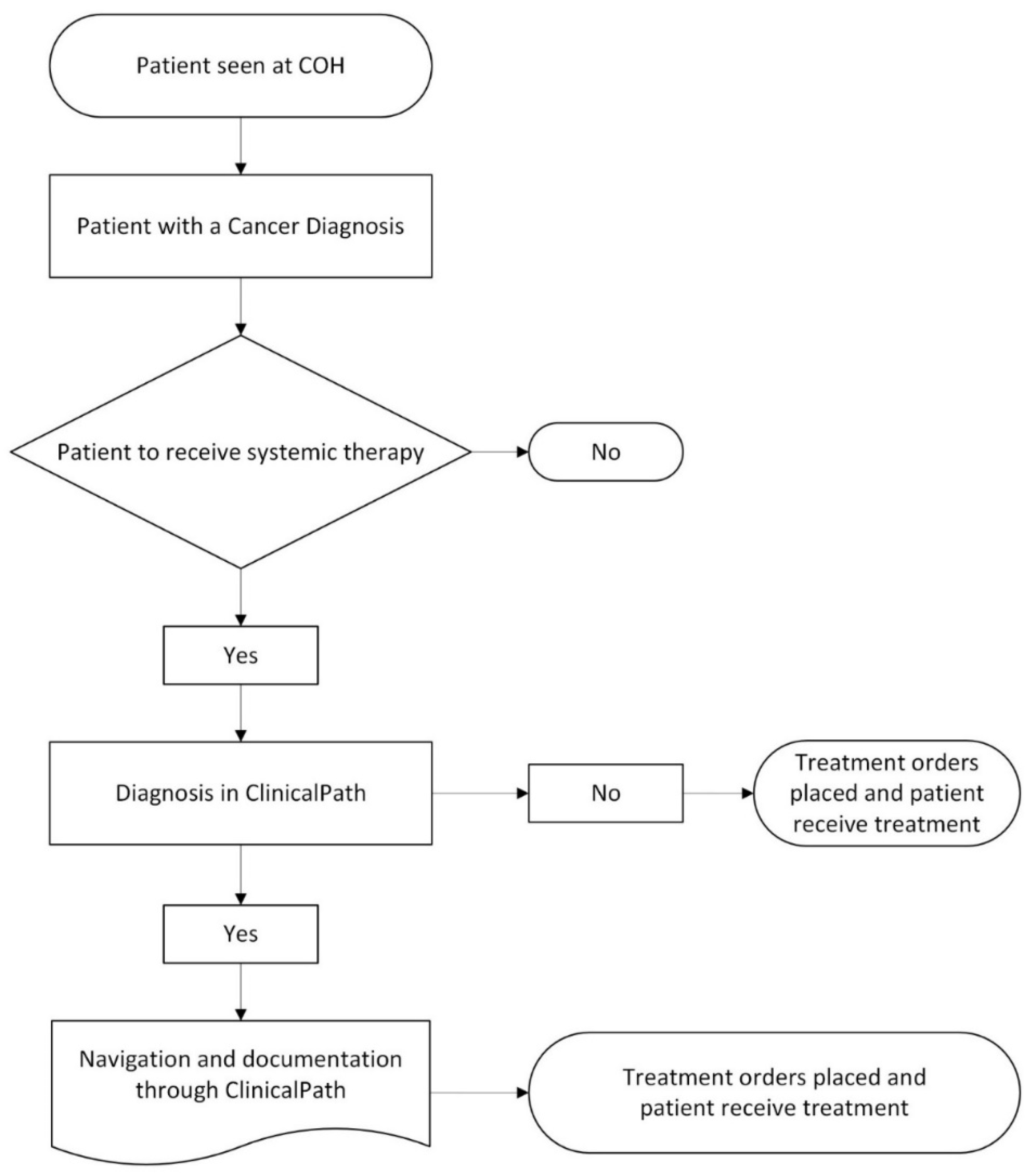

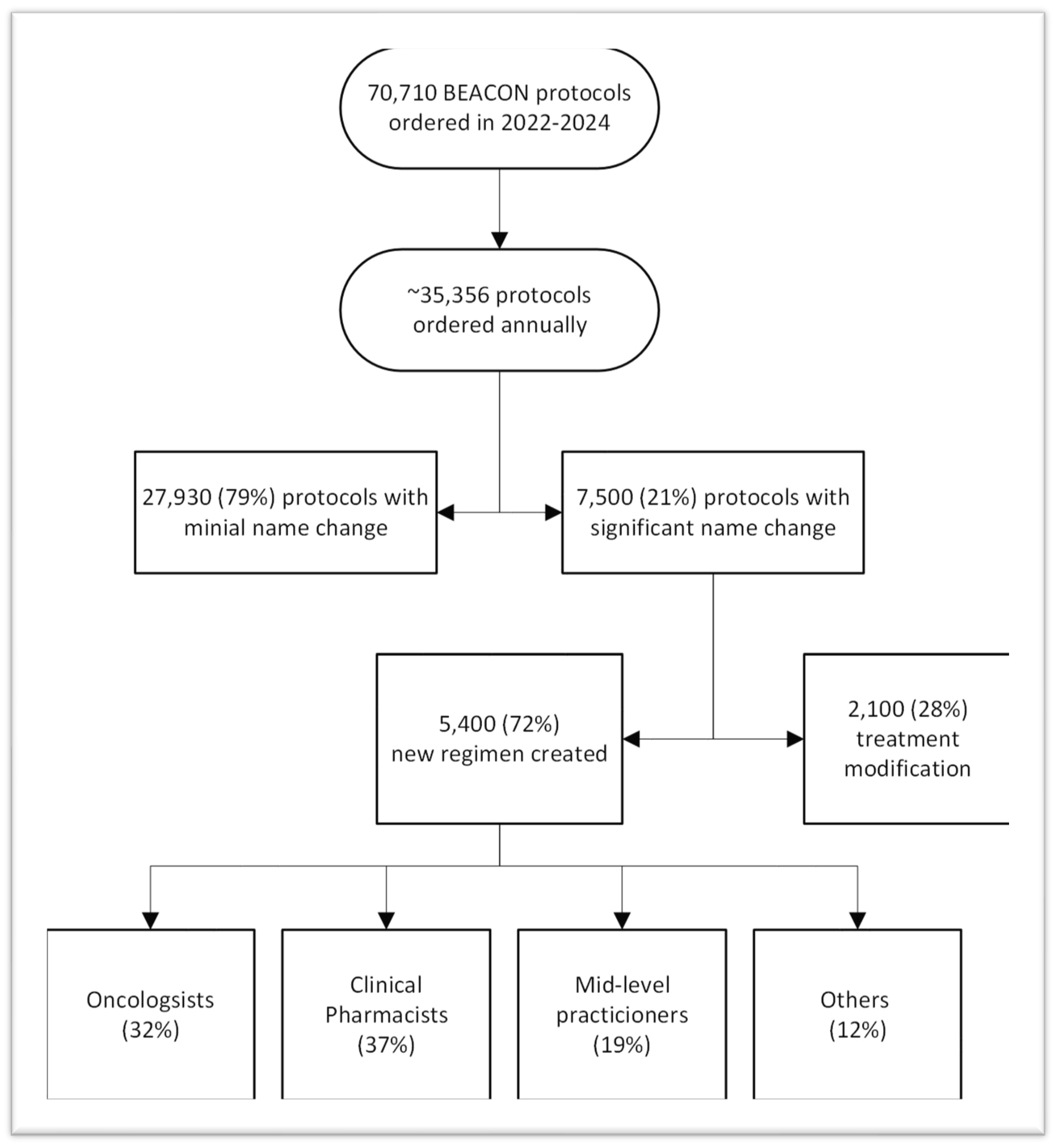

- Gap Analysis of Beacon orders built on the fly over two years was performed to understand the impacts of unbuilt protocols. The Epic system showed over 35,500 protocols were ordered annually, with 7500 being built or modified by clinicians or pharmacists. 5400 Beacon protocols were created, while 2100 were made by modifying existing protocols to create the needed treatment. The number and staff who built the missing protocols are shown in Figure 3. The 7500 protocols built or modified represent 21% of all Beacon protocols. Many protocols were built several times by different staff who needed to get their patients treated. We heard from one pharmacist who built a the same regimen ten times over a few months for different patients.

-

Three studies were conducted to estimate the time spent by staff in building Beacon protocols ad hoc. While the findings varied, all three studies revealed a significant daily time commitment from clinicians, clinical pharmacists, advanced practice providers (APPs), nurses (RNs), and others. The potential time savings, as reported, by having Beacon orders built in Epic could be redirected towards seeing a significantly higher number of new or follow-up patients and providing more comprehensive care to those patients. For instance, the CA and CAP community site study revealed that the 250 hours per month were being used by physicians to build Beacon orders. This could translate into 63 more new patients being seen monthly across those sites, assuming that for every 4 hours saved, at least one new patient could be seen. This revelation carries significant implications for accelerating access to high-quality cancer care, a top priority for our enterprise.

- ○

-

The first study estimated the physician’s time to build the Beacon orders. It is based on the Epic order study discussed above. Given that 7500 annual ad hoc Beacon protocols were built and based on the time experienced builders take to create or modify Beacon orders, estimates of the time used were made. Treatment plan modifications included the time to change orders in Beacon and to review and ensure the accuracy of the changes. Experienced Beacon order builders estimate the time needed to be 5 to 40 minutes, depending on the complexity of the modifications or new builds. When the combined MD, APP, RN, and PharmD times were evaluated, it was estimated that at least 128 hours per month were being wasted on these tasks that could be centralized. This data was primarily from the California network and academic sites, containing only 6 months of CAP site data as they transitioned to Epic in October 2023. Table 4 shows how the estimated wasted time was calculated.Table 4. Estimated monthly staff time to build or modify unbuilt Beacon orders based on Epic study.

Role % Time Editing Beacon Orders Estimated hours/month

Editing Beacon OrdersEstimated hours/year

Editing Beacon OrdersMD 32% 30.8-50.8 369-610 PharmD 37% 35.6-58.8 427-705 APP 19% 18.3-30.2 219-362 RN 3% 2.9-4.8 35-57 Others 9% 8.7-14.3 104-172 Total Hours Used: 96-159 1154-1906

- ○

- The second study of medical oncologists’ and hematologists’ time estimates to build Beacon orders was based on emails and discussions with the regional site leads for the California community network and CAP sites. They were asked to survey their doctors about the time their doctors were using each clinic day to build or modify orders that were not available. Based on the number of doctors and time spent at each site, monthly totals were calculated for wasted time per MD. Making the conservative assumption that for every 4 hours freed from creating orders, a doctor could see at least one new patient, the new patient potential for all the doctors at each community site was calculated. This conservative estimate shows that at least 63 more new patients could be seen monthly at the network sites across four states to better serve patients. Results are shown in Table 5.

- ○

- The third study was done to report the time clinical pharmacists spent building or editing Beacon orders that were not in our system. The clinical pharmacist program lead (YL) spoke to the clinical pharmacists at each of the sites with clinical pharmacists to gather their hours per day spent editing unbuilt Beacon orders. These pharmacists were those working at Duarte and Lennear, Irvine academic outpatient clinics, and the three CAP sites. This showed significant daily, weekly, and monthly use of our pharmacist’s time, conservatively estimated at 40 hours per day of clinical pharmacist time across the enterprise which could be used to better serve patients and the organization. Results are shown in Table 6.

3.4.1. Evaluating the Time and Staffing Required by Staff to Build Standardized Beacon Protocols

- Resource analysis has considered personnel needed for program management, leadership, clinical coordination, and technical support to maintain the EHR workload, catch up on current needs and plan for future growth. Program leadership includes an MD medical director leading the pathway and protocol program and an informal pharmacist with clinical oncology knowledge coordinating interdisciplinary teamwork among specialties to ensure program development fits COH’s practice and standards. To recover the current deficit and maintain program growth, sufficient technical support is required to build BEACON protocols for on- and off-pathway regimens.

- The core team worked with the IT and Epic Beacon staff to understand the time it takes to build beacon protocols with the standardized components for our Epic system. They reviewed data from the 2020 project to build 106 oral regimens over 6 months to meet QOPI and other oral CPOE standards as has been discussed. The medical director and an informatics pharmacist collected the clinical content from faculty disease leads, community oncologists, and clinical pharmacists, then worked with the budgeted beacon analyst builders. They were able to complete 94 protocol builds (84 moved into production and 10 pending Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) approval) plus 25 other protocols using an average of 9.38 hours of Beacon analyst time per protocol.

- From the time impact survey of physicians and clinical pharmacists discussed previously, expert clinical pharmacists noted that even modifying Beacon orders and reviewing their accuracy can take 5-40 minutes, depending on the complexity of the protocol. For new protocol builds, the time to build consists of the time to gather the clinical content for each applicable component of the order, the time to build the protocol in the Epic system, the time for MD, PharmD, and RN review and validation of the Epic build, then time for any edits and re-review for validation before a the final protocol order is sent to COH’s monthly Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee for final approval. After that, an approved protocol can be activated across all of our Epic sites. An alternative methodology is for an experienced oncology pharmacist to be trained and certified as an Epic builder. They can then gather the clinical content and build the initial Epic order with all its components to avoid any back-and-forth between the clinical content provider and the Beacon analyst builder. Oncology pharmacists are the most experienced in the many nuances and details needed to build a complete oncology order protocol, but few have Epic Beacon builder certification. Thus, most organizations have clinical pharmacists or clinicians provide the content and then work with an Epic Beacon analyst builder until they are satisfied with the Beacon protocol. A disease team of an MD, RN, and PharmD then reviews the final order for any edits and their approval so it can be sent to the P&T committee for final approval and movement into the Epic system.

- The core team estimated the additional staffing needed to catch up and maintain our Beacon protocols. This was calculated to catch up 400 unbuilt protocols (326 prioritized from the ClinicalPath pathways and 71 requests for updates from clinicians to IT) and to provide the biannual protocol review for the current 1100 Beacon protocols. New protocol builds are estimated to require an average of 4 hours of PharmD time, ranging from 2 to 10 hours. Updates to current protocols are estimated to take 1.5 hours of PharmD time, and protocol review and standardization, including the updated new antiemetic regimens, is estimated to take 2 hours per protocol. Thus, the catch-up work would require 3907 hours of PharmD time: (400 protocols x4 hours)+ (71 protocols x 1.5 hours) + (1100 protocols x 2 hours), which would require two full-time PharmDs. For the Maintenance of Beacon protocols, we estimated 220 new protocols annually take an average of 4 hours of PharmD time (with a range of 2-10 hours), 200 clinician requests for updates or modifications annually take an average of 1.5 hours of PharmD time and the ongoing biannual review of half of what will be 1500 Beacon protocols means 750 protocols need to be reviewed annually at 2 hours of PharmD time each. Thus, for the Maintenance of Beacon Protocols, it will take 2750 hours of PharmD time: (225x4) + (200 x 1.5) + 750 x2), which would require 1.5 full-time PharmDs. The results are shown in Table 7.

- Going through a similar process for the Beacon analyst builders and Willow analyst builders along with the project manager, an overall recommendation was made for the added resources needed to catch up and maintain our Beacon protocols. These recommendations are shown in Table 8. The total budget for the catch-up work was estimated to be $1.9 million dollars over 14 months. The total budget for the annual maintenance work was estimated to be $1.1 million dollars.

- A benchmarking study was conducted on staffing to build and maintain Beacon protocols at two large cancer organizations, and it was compared to COH’s current and proposed staffing. Two COH staff who had recently transitioned from two large, multi-state, multi-site Epic Beacon using cancer programs gathered information about the number of Beacon protocols and the resources used to build and maintain them. Results, comparing the current and proposed additional resources for Beacon protocols at City of Hope, are shown in Table 9. The benchmarking study supports the need for additional staff to catch up and maintain COH’s Beacon orders.

3.5.1. Recommendations for Updated Enterprise Antiemetic Standards for Oral and IV Dominant Regimens:

- The clinical pharmacy team recommended that the following medications be standardized for the antiemetic regimens to meet HEC, MEC, LEC, and MIN needs in our Beacon protocols consistent with the latest NCCN guidelines, site and disease team needs. Table 10 shows the recommended drugs for the oral and IV dominant antiemetic protocols by emetogenic risk category.

- The antiemetic doses are then further adjusted when NK1 RA medications need to be deleted, or steroids adjusted or when partnered with one of the four chemotherapy regimens where steroid dosing needs to be coordinated with hypersensitivity and emetogenic prevention. Table 11 shows the different modifications of the antiemetic drug dosing to be built.

- These combinations resulted in 24 standardized regimens for antiemetics that can be added to Beacon protocols. These 24 regimens will be built in two ways: as oral dominant or oral plus day of therapy IV regimens to meet different payer and care needs. These regimens were developed with enterprise pharmacy input and then reviewed and approved by medical oncology, hematology, and nursing departments. Building these pre- and post-medication protocols will be prioritized for addition to all new Beacon protocols. They will also be added to the current Beacon protocols as they are reviewed biannually or earlier, pending resource availability.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005 Apr 2;330(7494):765. [CrossRef]

- Pawloski PA, Brooks GA, Nielsen ME, Olson-Bullis BA. A Systematic Review of Clinical Decision Support Systems for Clinical Oncology Practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019 Apr 1;17(4):331-338. [CrossRef]

- Weingart SN, Zhang L, Sweeney M, Hassett M. Chemotherapy medication errors. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr;19(4):e191-e199. [CrossRef]

- Weese, J.; Citrin, L.Y.; Shamah, CJ, Bjegovich-Weidman, M.; Twite, K.A.; Sanchez, F.A., Preparing for Value-Based Cancer Care in a Multisite, Integrated Healthcare System. Oncology Issues 2017, November, 32(6): pp. 44-50. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Hewitt M, Simone JV, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Improving the Quality of Cancer Care: Addressing the Challenges of an Aging Population; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine. Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Levit L, Balogh E, Nass S, Ganz PA, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2013 Dec 27. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Assessing and Advancing Progress in the Delivery of High-Quality Cancer Care: Proceedings of a Workshop. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [CrossRef]

- Charles Settles. A History of Meaningful Use. https://technologyadvice.com/blog/healthcare/history-of-meaningful-use-2015/ (accessed on 8-1-24).

- Definitive Healthcare, Most Common hospital HER systems by market share. January 2024. https://www.definitivehc.com/blog/most-common-inpatient-ehr-systems. (accessed on 8-1-2024).

- Epic Company Facts. 8-28-2024 https://www.epic.com. (accessed on 8-1-2024).

- Srinivasamurthy SK, Ashokkumar R, Kodidela S, Howard SC, Samer CF, Chakradhara Rao US. Impact of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) on the incidence of chemotherapy-related medication errors: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021 Aug;77(8):1123-1131. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi R, Kazemi A, Moghaddasi H, Arjmandi Rafsanjani K, Bahoush G. Specifications of Computerized Provider Order Entry and Clinical Decision Support Systems for Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review. Chemotherapy. 2018;63(3):162-171. [CrossRef]

- Kukreti V, Cosby R, Cheung A, Lankshear S. Computerized Prescriber Order Entry Guideline Development Group. Computerized prescriber order entry in the outpatient oncology setting: from evidence to meaningful use. Curr Oncol. 2014 Aug;21(4):e604-12. [CrossRef]

- Meisenberg BR, Wright RR, Brady-Copertino CJ. Reduction in chemotherapy order errors with computerized physician order entry. J Oncol Pract. 2014 Jan;10(1):e5-9. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman JM, Baker DK, Howard SC, Laver JH, Shenep JL. Safe and successful implementation of CPOE for chemotherapy at a children’s cancer center. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2011 Feb;9 Suppl 3:S36-50. [CrossRef]

- Connelly TP, Korvek SJ. Computer Provider Order Entry. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470273/. (accessed on 8-1-2024).

- Aziz, M. T., Ur-Rehman, T., Qureshi, S., & Bukhari, N. I. (2015). Reduction in chemotherapy order errors with computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems. Health Information Management Journal, 44(3), 13–22. [CrossRef]

- Shulman LN, Miller RS, Ambinder EP, Yu PP, Cox JV. Principles of Safe Practice Using an Oncology EHR System for Chemotherapy Ordering, Preparation, and Administration, Part 1 of 2. J Oncol Pract. 2008 Jul;4(4):203-206. [CrossRef]

- Shulman LN, Miller RS, Ambinder EP, Yu PP, Cox JV. Principles of Safe Practice Using an Oncology EHR System for Chemotherapy Ordering, Preparation, and Administration, Part 2 of 2. J Oncol Pract. 2008 Sep;4(5):254-257. [CrossRef]

- Cheng CH, Chou CJ, Wang PC, Lin HY, Kao CL, Su CT. Applying HFMEA to prevent chemotherapy errors. J Med Syst. 2012 Jun;36(3):1543-51. [CrossRef]

- Meisenberg BR, Wright RR, Brady-Copertino CJ. Reduction in chemotherapy order errors with computerized physician order entry. J Oncol Pract. 2014 Jan;10(1):e5-9. [CrossRef]

- The Joint Commission, Sentinel Even Alert: Safe use of health information technology. TheJointCommission, 54, March 31, 2015 https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_54_hit_4_26_16.pdf. (accessed on 8-1-2024).

- Castlight Health. Results of the 2014 Leapfrog Hospital Survey: Computerized Physician Order Entry. 2015 Leapfrog Reports. https://www.leapfroggroup.org/sites/default/files/Files/2014LeapfrogReportCPOE_Final.pdf (accessed on 8-1-2024).

- The Leapfrog group. Guidance for the 2024 Leaspfrog CPOE Evaluation Tool. https://www.leapfroggroup.org/sites/default/files/Files/CPOE%20Tool%20Guidance%202pdf?token=pbjoOfz9 (accessed on 8-7-2024).

- Naseralallah L, Stewart D, Price M, Paudyal V. Prevalence, contributing factors, and interventions to reduce medication errors in outpatient and ambulatory settings: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2023 Dec;45(6):1359-1377. [CrossRef]

- Weingart SN, Zhang L, Sweeney M, Hassett M. Chemotherapy medication errors. Lancet Oncol. 2018 Apr;19(4):e191-e199. [CrossRef]

- Institute for Safe Medication Practices. IMPS’s Guidelines for Standard Order Sets. 2010. https://www.ismp.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2018-01/StandardOrderSets.pdf. (accessed on 9-1-2024).

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Computerized Provider Order Entry with Decision Support in SAFER Guidelines p1-45, 2016. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/safety/safer-guides (accessed on 9-11-2024).

- DiMarco, PharmD, BCPS, BCOP, Rose; Espinosa, MAT, PharmD, BCOP, Gloria; Miskovsky, PharmD, BCOP, Kelly; and Hemmert, PharmD, Gina, “Oncology Treatment Plan Updates in EPIC-Beacon” (2024). Kimmel Cancer Center Papers, Presentations, and Grand Rounds. Paper 71. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/kimmelgrandrounds/71 (accessed on 9-11-24).

- Busby, L., Sheth, S., Garey, J., Ginsburg, A., Flynn, T., Willen, M., & Kruger, S. (2011). Creating a process to standardize regimen order sets within an electronic health record. Journal of Oncology Practice, 7 (4) p e8-12. [CrossRef]

- Bosserman LD, Verrilli D, McNatt W. Partnering With a Payer to Develop a Value-Based Medical Home Pilot: A West Coast Practice’s Experience. J Oncol Pract. 2012 May;8(3 Suppl):38s-40s. [CrossRef]

- Setareh S, Rabiei R, Mirzaei HR, Roshanpoor A, Shaabani M. Effects of Guideline-based Computerized Provider Order Entry Systems on the Chemotherapy Order Process: A Systematic Review. Acta Inform Med. 2022 Mar;30(1):pp.61-68. [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Díaz-Pallarés M, Pérez-Menéndez-Conde C, Bermejo-Vicedo T. Systematic review of computerized prescriber order entry and clinical decision support. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018 Dec 1;75(23): pp.1909-1921. [CrossRef]

- Bosserman L, Cianfrocca M, Yuh, B, et al., Integrating Academic and Community Cancer Care and Research through Multidisciplinary Oncology Pathways for Value-Based Care: A Review and the City of Hope Experience. J Clin Med. 2021 January;10(2),188. [CrossRef]

- Bosserman L D, Mambetsariev I, Ladbury C., et al., Pyramidal Decision Support Framework Leverages Subspecialty Expertise across Enterprise to Achieve Superior Cancer Outcomes and Personalized, Precision Care Plans. J Clin Med. 2022 Nov 14;11(22):6738. [CrossRef]

- Zon RT, Edge SB, Page RD, Frame JN, Lyman GH, Omel JL, Wollins DS, Green SR, Bosserman LD. American Society of Clinical Oncology Criteria for High-Quality Clinical Pathways in Oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2017 Mar;13(3): pp.207-210. [CrossRef]

- Weese JL, Shamah CJ, Sanchez FA, et al., Use of treatment pathways reduce cost and decrease ED utilization and unplanned hospital admissions in patients (pts) with stage II breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019: 37: 15_suppl, e12012. [CrossRef]

- Weese, JL, Shamah, CJ, Sanchez, FA, et al., Use of treatment pathways reduce cost and increase entry into clinical trials in patients (pts) with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol. 2020; 38:15_suppl, e21000-e21000. [CrossRef]

- Neubauer MA, Hoverman JR, Kolodziej M, et al. Cost effectiveness of evidence-based treatment guidelines for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer in the community setting. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(1):12-18. [CrossRef]

- Hoverman JR, Cartwright TH, Patt DA, et al. Pathways, outcomes, and costs in colon cancer: retrospective evaluations in two distinct databases. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 Suppl):52s-9s. [CrossRef]

- Neubauer M. Clinical pathways: reducing costs and improving quality across a network. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2 Spec No.): SP60-SP61. [CrossRef]

- Gress, Donna & Edge, Stephen & Greene, Frederick & Washington, Mary & Asare, Elliot & Brierley, James & Byrd, David & Compton, Carolyn & Jessup, John & Winchester, David & Amin, Mahul & Gershenwald, Jeffrey. (2017). Principles of Cancer Staging. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Chapter 1. https://www.facs.org/media/xuxfkbpb/principles_cancer_staging.pdf (accessed on 6-2-2024). [CrossRef]

| Treatment Schedule | Treatment Details | Patient Instructions | Nursing Instructions | Supportive Care | Regulatory Requirements |

| Financial Authorization | Drugs, dosing, and scheduling | Education on regimen and home care | Infusion and administration instructions | Neutropenic fever | Oral chemo compliance check |

| Lab & Imaging orders | Dose modification and hold rules | Lab, imaging, and visit schedule | Treatment details-timing, sequencing, mixing | Infection prevention and prophylaxis | REMS program |

| Treatment days | Antiemetic and hypersensitivity orders | Treatment schedule | Treatment parameters for dosing or not | VTE prevention | Hepatitis B/C and TB screening |

| MD & other visits | Specialty Pharmacy use | Fertility preservation info/referrals | Emergency medications & extravasations | TLS prevention | Pregnancy screening |

| Standardized Beacon protocol format |

| Protocol name |

| Protocol description |

| Emetogenicity designation |

| Reference to treatment or landmark trials |

| Display template of orders |

| Sites | # Hematologists | # Medical Oncologists | MD time per day on orders | PharmD help | Total Time per month per MD | New Patient potential per month per site |

| CA Network | 48 | 0.25 hour | No | 6 hours | 72 hours |

|

| CAP-Chicago | 1 | 8 | 1.5 hours | Yes | 28 hours | 63 hours |

| CAP-Atlanta | 2 | 6 | 1 hour | No | 20 hours | 40 hours |

| CAP-Phoenix | 12 | 1.25 hours | No | 25 hours | 75 hours |

|

Sites with PharmDs |

# of PharmDs |

Time spent per PharmD on Beacon orders |

Comments |

| Duarte (outpatient only) |

17 | 1-1.5 hours/ PharmD | Could free 17-25 hours of PharmD time per day |

| Lennar in Irvine | 1-2 | 1.5-2 hours/ PharmD | Could free 3-4 hours per PharmD per day |

| Chicago | 15 | 1 hour/ PharmD | Could free 15 hours of PharmD time per day based on 50 patients/day |

| Phoenix | 3-4 | .25 hour/PharmD per patient |

It can take 30 minutes per Beacon order for complicated protocols |

| Task | # Protocols | Pharmacist Time Per Protocol | Total Time PharmD | Beacon Builder per Protocol | Total Time Beacon Builder |

| New Protocol Build (most complex treatment plans) |

400 Catch Up Builds 220 Annual New Builds |

4 hours (range 2-10 hrs) 4 hours (range 2-10 hrs) |

1,600 hours 880 hours |

6.5 hours 6.5 hours |

2600 hours 1430 hours |

| Protocol Updates based on requests |

200 annually |

1.5 hours |

300 hours |

4.0 hours |

800 hours |

| Biannual Protocol Review and Antiemetic Updates |

750 (based on 1500 total) |

2 hours |

1500 hours |

2.0 hours |

1500 hours |

| FY25 and FY26Q1 | FY 27 forward | |

| Beacon Protocol Catch-Up Project | ||

| Informatics Pharmacists | 2 FTE (1 have +1 new) | N/A |

| Operations Project Manager | 0.5 FTE new | N/A |

| Epic Beacon Systems Analyst (builder) | 3 FTE new contractor | N/A |

| Epic Willow Systems Analyst (builder) | 1 FTE existing | N/A |

| IT Project Manager | 0.20 FTE contractor | N/A |

| Annual Beacon Protocol Maintenance | ||

| Informatics Pharmacist | 1 FTE new | 3 FTE |

| Operations Project Manager | 0.5 FTE new | 0.5 FTE |

| Epic Beacon Systems Analyst (builder) | 2 FTE existing | 2 FTE |

| Epic Willow Systems Analyst (builder) | 1 FTE existing | 1 FTE |

| IT Project Manager | N/A | |

| COH Current Orders & Staffing | Other NCI Cancer Center Orders & Staffing | Large Integrated Multistate Health System | NEW COH Orders & Staffing Needs | ||

| Active Protocols (total) |

3100 |

~5000 |

2400 |

3500 |

|

|

Standard of Care (SOC) |

1100 | ~1800 | 2400 | 1500 | |

| Beacon Analyst/builder |

1.5 |

2.4-3.2 |

3 |

4.5 (+3) |

|

| Informatics PharmD |

1 |

4-5.2 |

5 |

3 (+2) |

|

| Medication/Willow builder |

2 |

3-4 |

1 |

3 (+1) |

|

|

Clinical Trial Protocols (IRB) |

2000 | ~3000 | ---- | 2000 | |

| Beacon Analyst/builder |

7.8 |

4.8-5.6 |

---- |

No change |

|

| Informatics Pharm/RNs |

14 |

7.8-9 |

---- |

No change |

|

| Medication/Willow builder |

2 |

6-7 |

---- |

No change |

| Drug Class | Medications | HEC | MEC | LEC | MIN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NK1 RA | Outpatient: Aprepitant Inpatient Fosaprepitant |

X | |||

| 5HT3 RA | IV dominant: Palonosetron Oral Dominant: Ondansetron |

X | X | IV or Oral Ondansetron |

PRN Ondansetron |

| Steroid | Dexamethasone * | X4 days | X3 days | ||

| 5H2, 5H3, dopamine, D2 RA |

Olanzapine** |

PRN X4 days |

PRN X3 days |

| Drug | HEC | MEC | LEC | MIN |

| HEC multiday | ||||

| HEC | MEC | LEC | MIN | |

| HEC no NK1 RA | ||||

| HEC min steroid | MIN -min steroid | |||

| Paclitaxel q2-3 week | HEC-Paclitaxel | MEC-Paclitaxel | LEC-Paclitaxel | |

| HEC no NK1 RA-Paclitaxel | ||||

| Paclitaxel weekly | HEC-Paclitaxel weekly | MEC-Paclitaxel weekly | LEC-Paclitaxel weekly | |

| HEC no NK1-Paclitaxel weekly | ||||

| Docetaxel | HEC-Docetaxel | MEC-Docetaxel | LEC-Docetaxel | |

| HEC-no NK1 RA-Docetaxel | ||||

| Pemetrexed | HEC-Pemetrexed | MEC-Pemetrexed | LEC-Pemetrexed | |

| HEC no NK1 RA-Pemetrexed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).