Submitted:

11 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

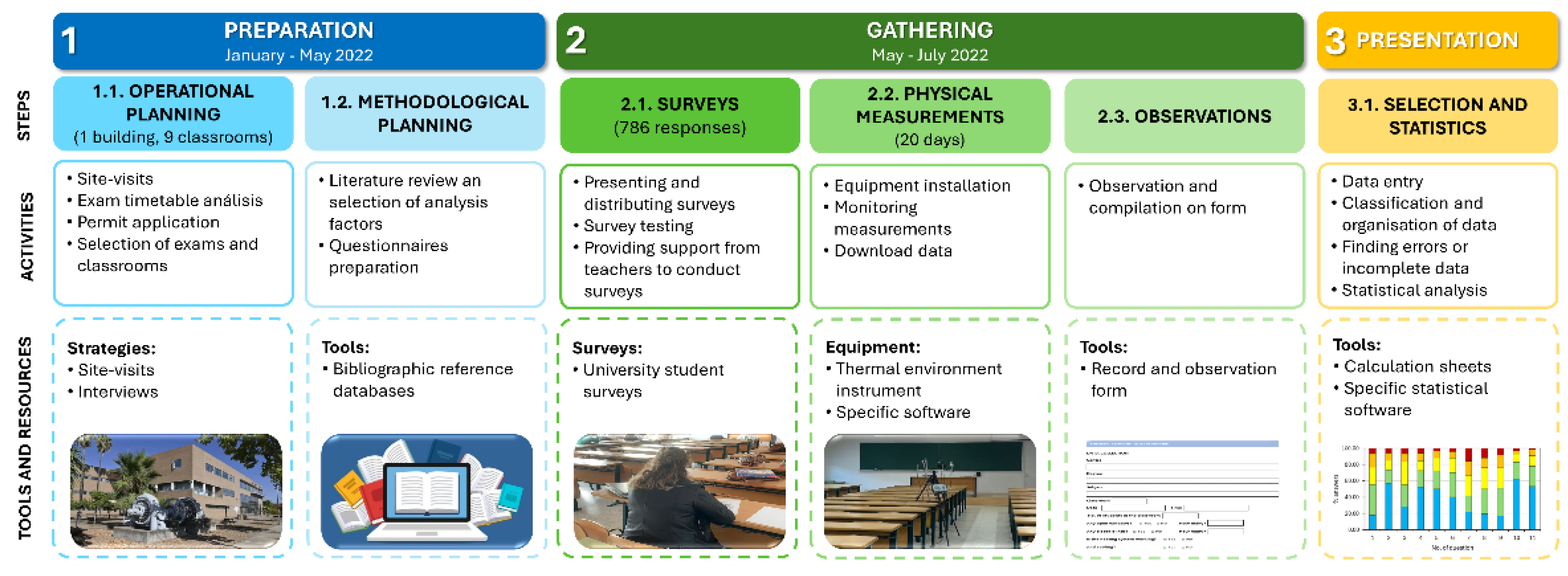

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation Stage

2.1.1. Operational planning

2.1.1. Methodological Planning

2.2. Data Collection Stage

2.2.1. Surveys

2.2.2. Physical Measurements

2.2.3. Observations

2.3. Data Reporting Stage

2.3.1. Statistics Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

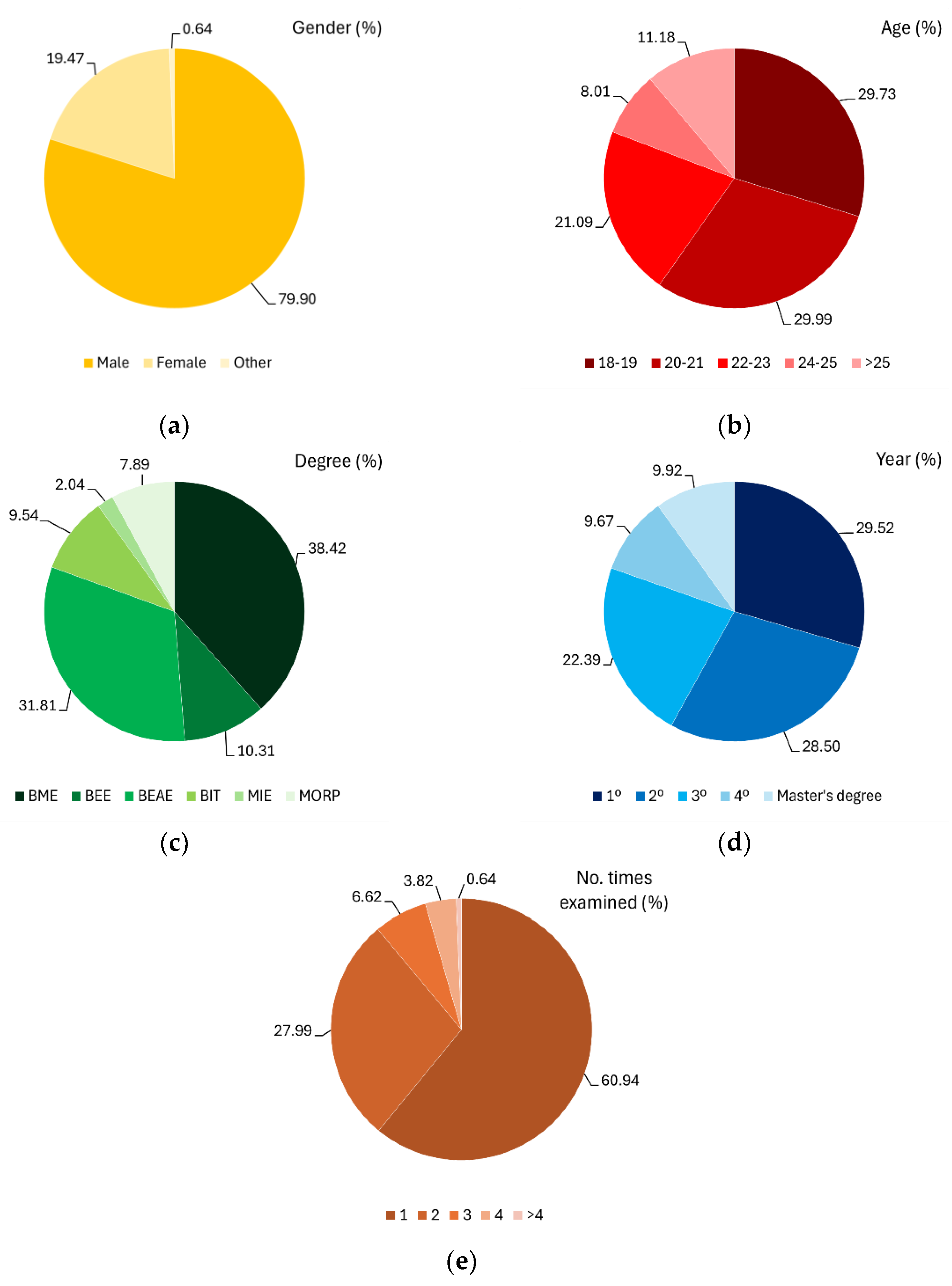

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Data Analysis

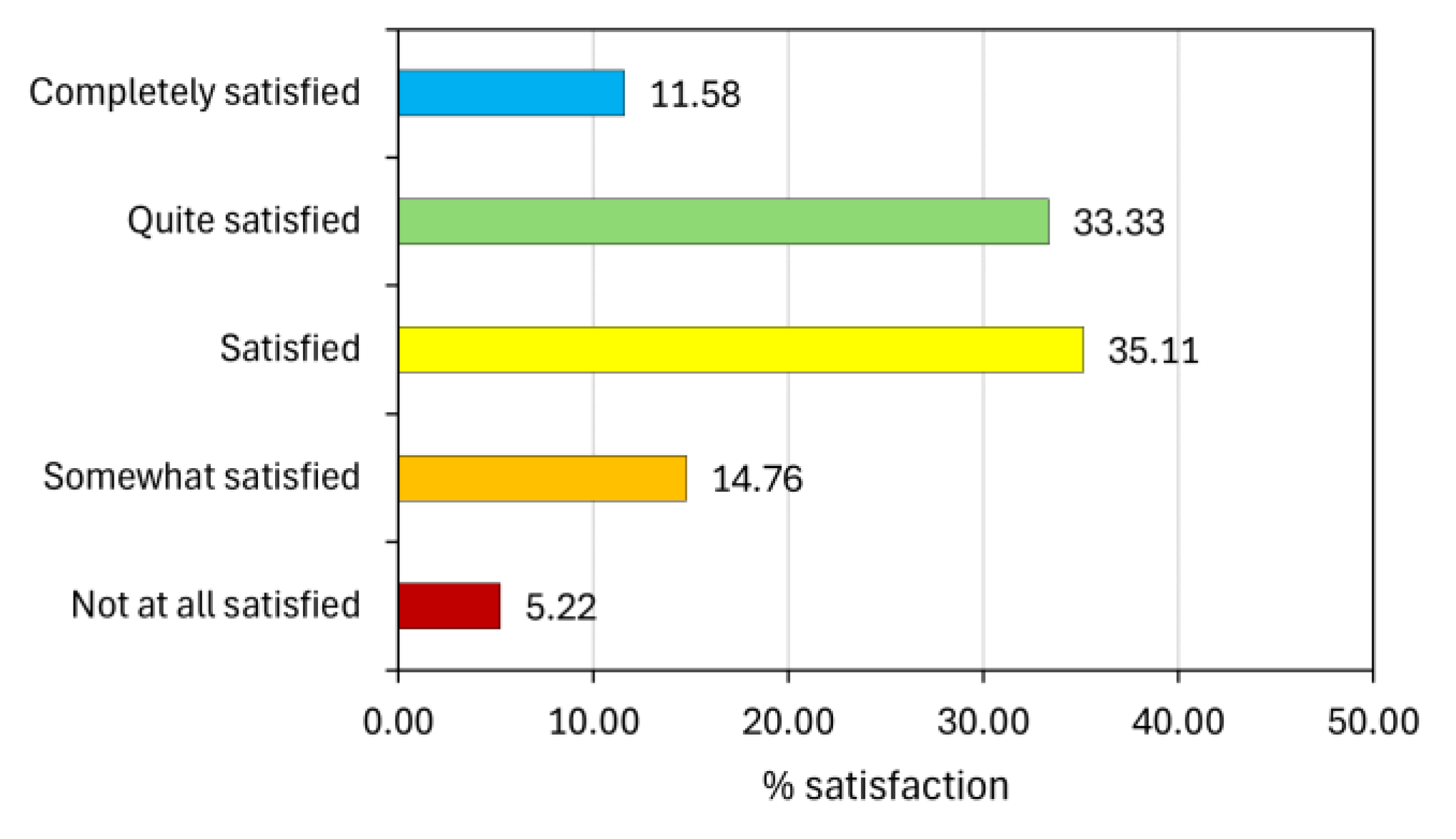

3.2.1. Scale of Satisfaction with the Exams

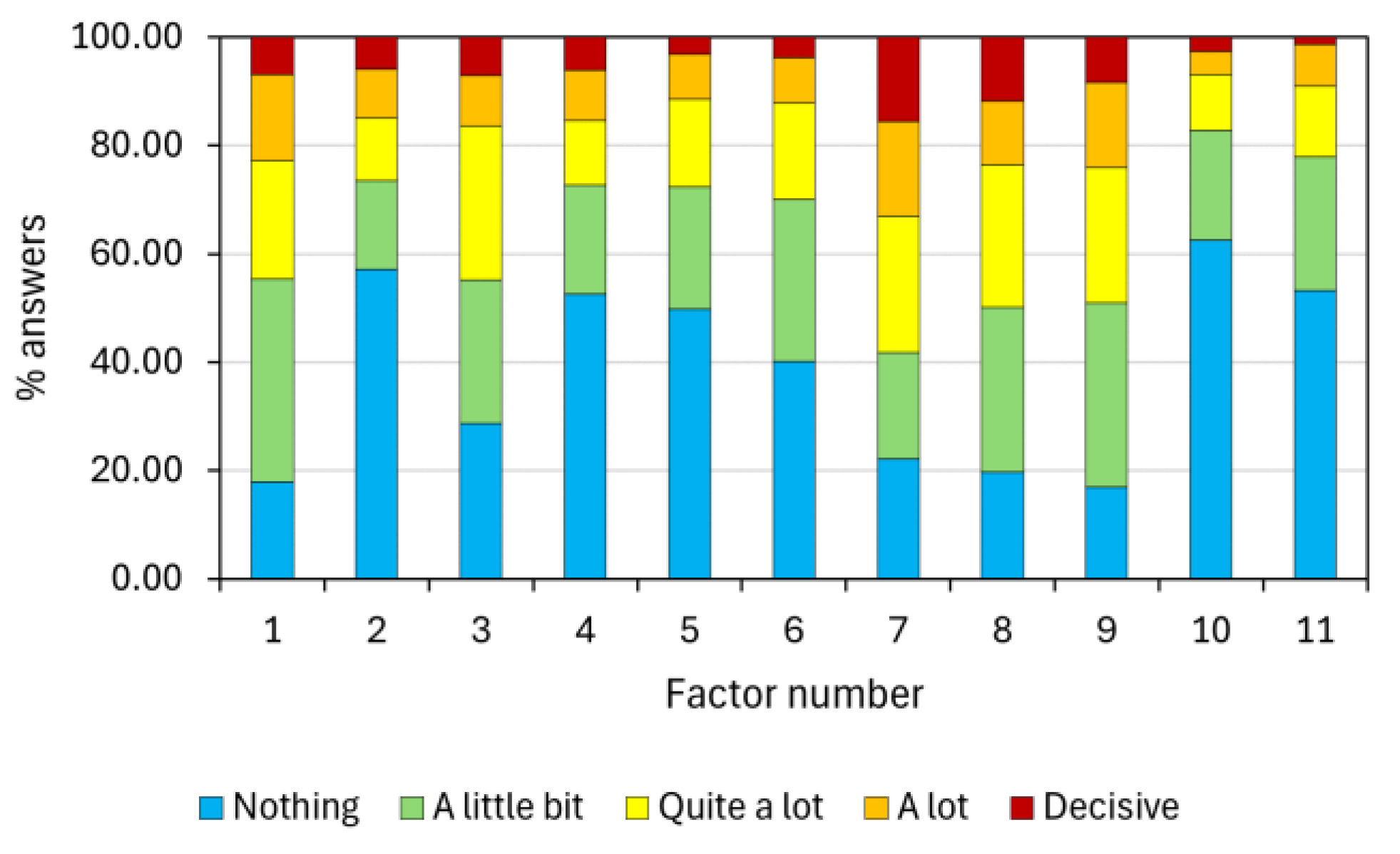

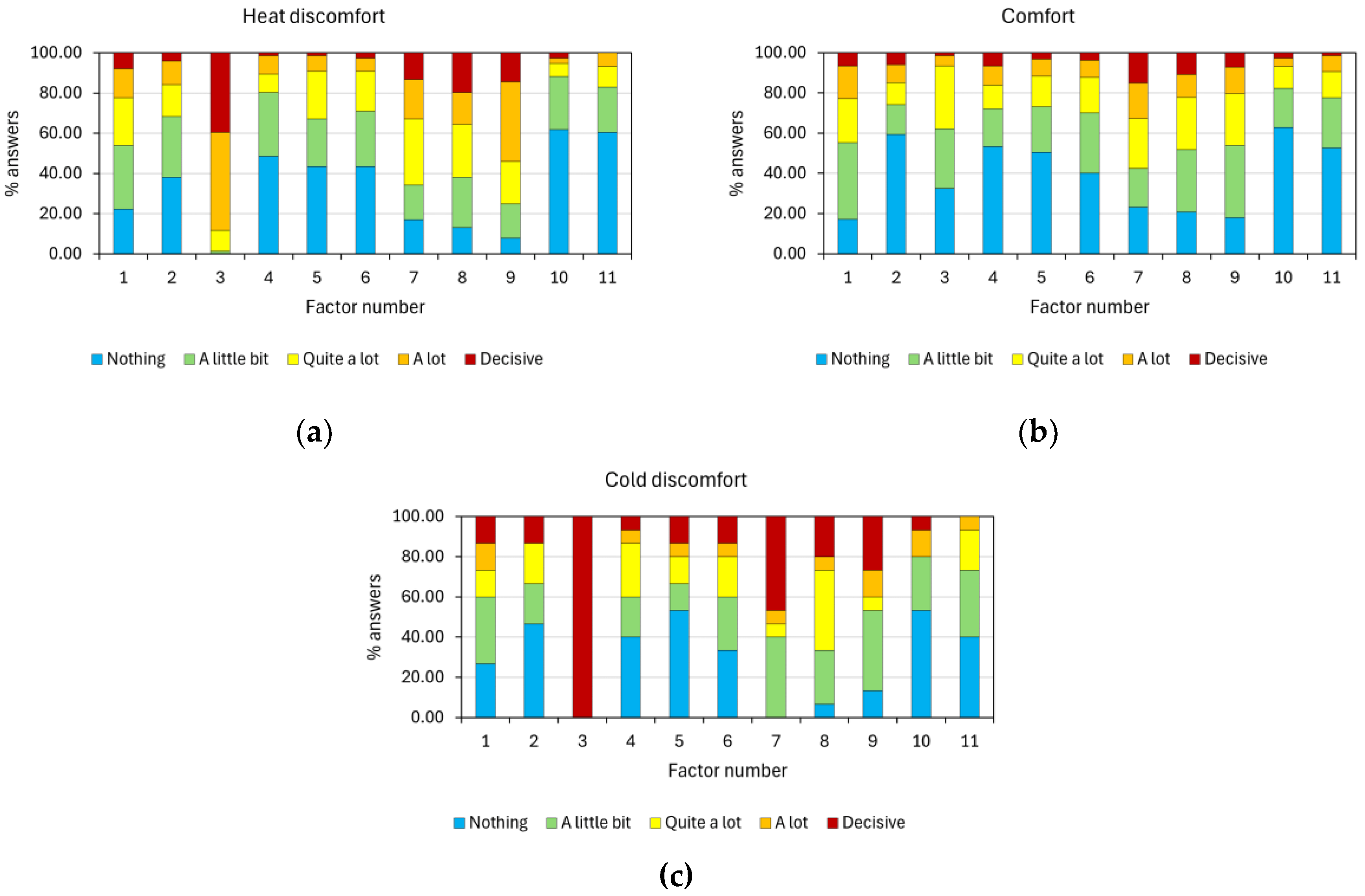

3.2.2. Factors Negatively Influencing Academic Performance

3.2.3. Analysis of the Internal Structure of Factors Influencing Academic Performance

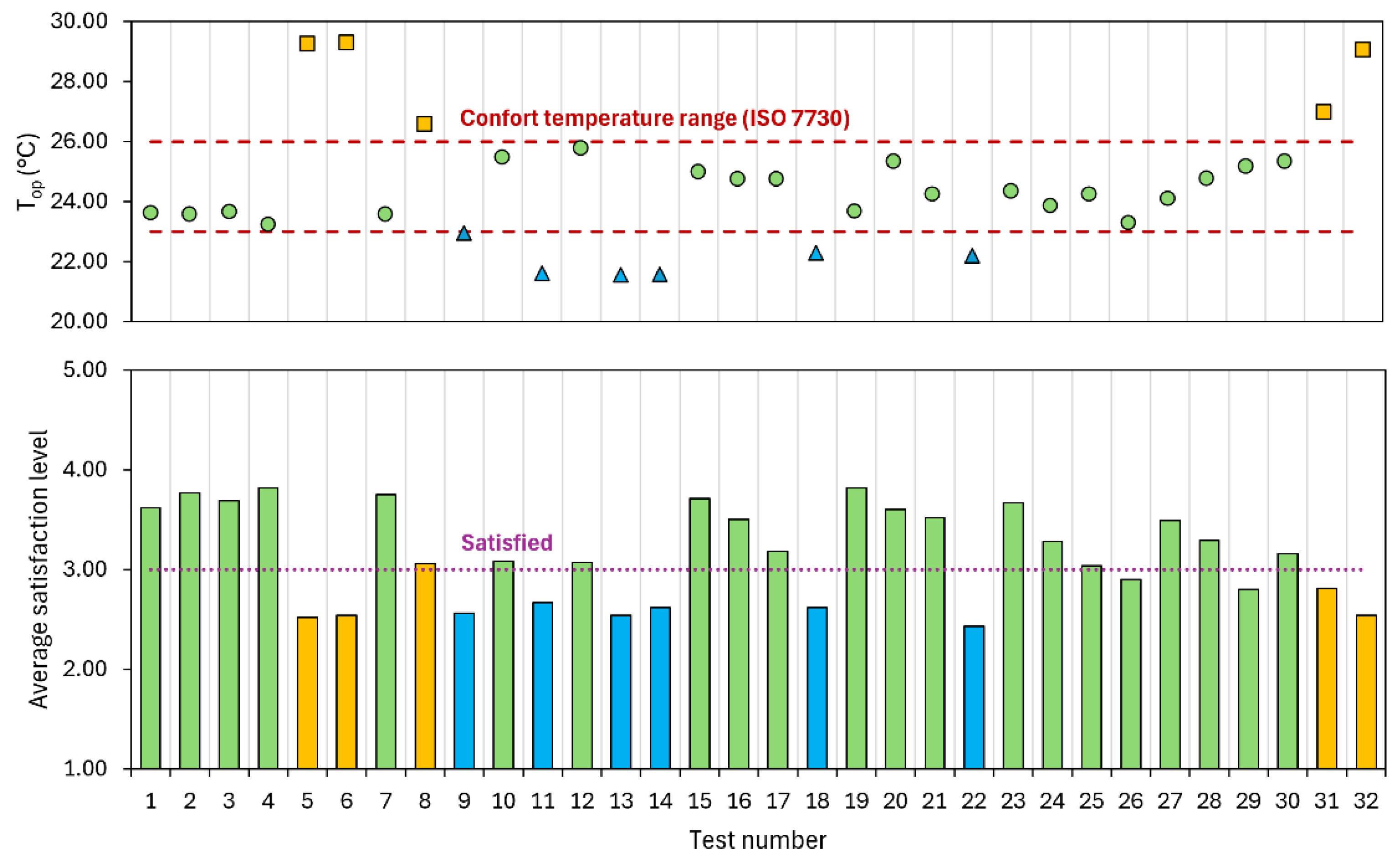

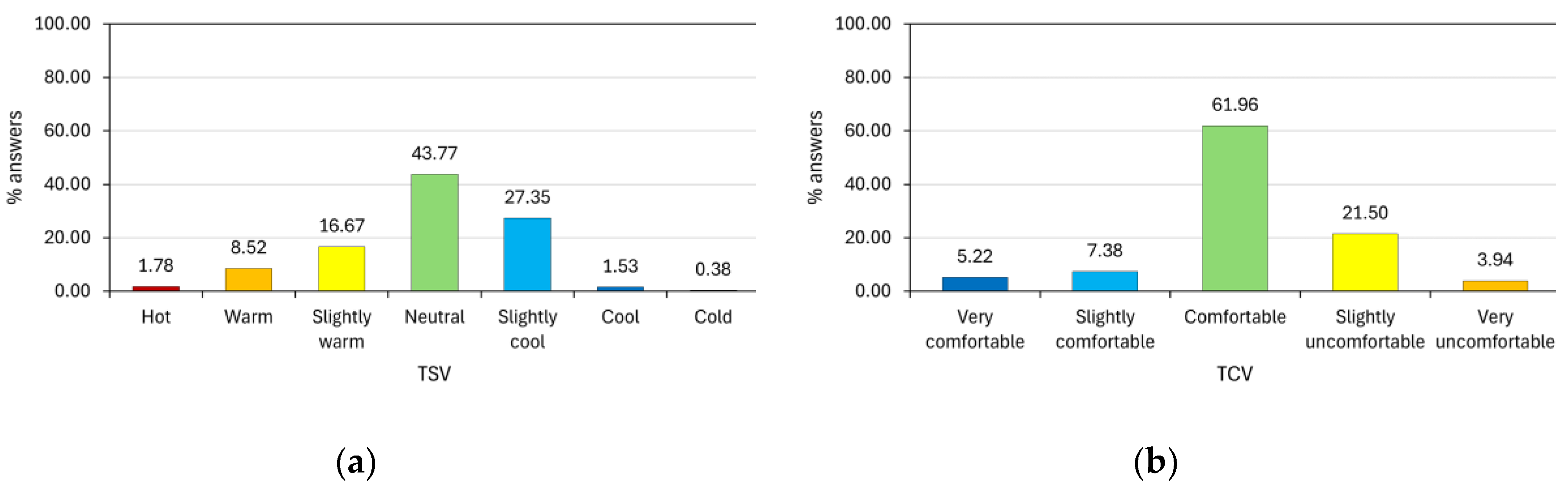

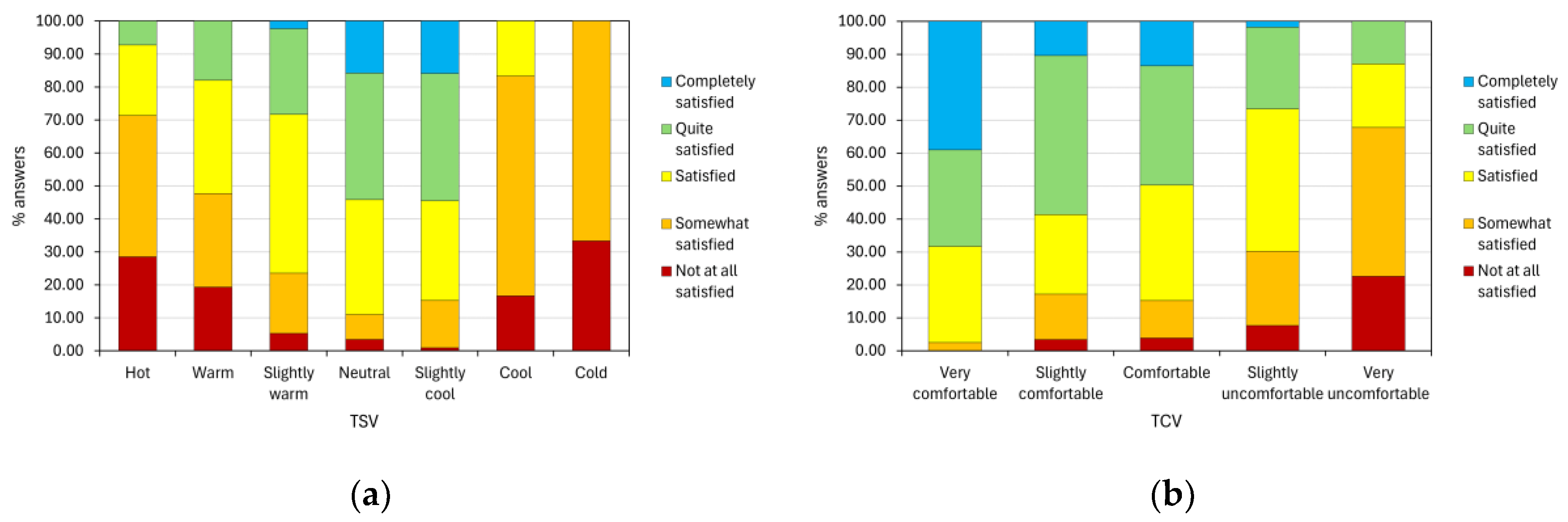

3.2.4. Environmental Conditions and Thermal Comfort

4. Conclusions, Implications and Limitations

References

- Azziz, N.H.A.; Saad, S.A.; Yazid, N.M.; Muhamad, W.Z.A.W. Factors Affecting Engineering Students Performance: The Case of Students in Universiti Malaysia Perlis. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the International Conference on Mathematics, Engineering and Industrial applications 2018 (ICoMEIA 2018); 2018; p. 020030. [Google Scholar]

- Rockstraw, D.A. Use of the Fundamentals of Engineering Exam as an Engineering Education Assessment Tool. Chem. Eng. Law Forum 2013 - Core Program. Area 2013 AIChE Annu. Meet. Glob. Challenges Eng. a Sustain. Futur. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, A.B.; Hebets, E.A.; Cleland, T.A.; Fitzpatrick, C.L.; Hauber, M.E.; Stevens, J.R. Embracing Multiple Definitions of Learning. Trends Neurosci. 2015, 38, 405–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalaeng, C.; Subongkod, M.; Sinlapasawet, W. Individual Competency Casual Factors Affecting Performance of Academic Personnel in Higher Education Institution. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 237, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, A.; Bravo-Adasme, N.; Araya, P.; Ormeño, V. Why University Students Are Technostressed with Remote Classes: Study-Family Conflict, Satisfaction with University Life, and Academic Performance. Telemat. Informatics 2023, 80, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharin, M.; Ismail, W.R.; Ahmad, R.R.; Majid, N. Factors Affecting Students’ Academic Performance Using Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP). In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Research and Education in Mathematics (ICREM7); IEEE, August 2015; pp. 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Dai, M.; Mathis, R. The Influences of Student- and School-Level Factors on Engineering Undergraduate Student Success Outcomes: A Multi-Level Multi-School Study. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2022, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Barroso, G.; González-Domínguez, J.; García-Sanz-Calcedo, J.; Zamora-Polo, F. Analysis of Learning Motivation in Industrial Engineering Teaching in University of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botejara-Antúnez, M.; Sánchez-Barroso, G.; González-Domínguez, J.; García-Sanz-Calcedo, J. Determining the Learning Profile of Engineering Projects Students from Their Characteristic Motivational Profile. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloposki, T.; Virtanen, V.; Clavert, M. From a Final Exam to Continuous Assessment on a Large Bachelor Level Engineering Course. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, D. Effective and Efficient Use of the Fundamentals of Engineering Exam for Outcomes Assessment. Educ. Div. 2017 - Core Program. Area 2017 AIChE Annu. Meet. 2017, 2017, 632–652. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.K.; Ooka, R.; Rijal, H.B.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Mahapatra, S. Progress in Thermal Comfort Studies in Classrooms over Last 50 Years and Way Forward. Energy Build. 2019, 188–189, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almoslamani, Y. The Impact of Learning Strategies on the Academic Achievement of University Students in Saudi Arabia. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. Gulf Perspect. 2022, 18, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, S.; Bukhsh, Q. A Study of Factors Affecting Students’ Performance in Examination at University Level. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 2042–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Gul, R.; Zeb, M. A Qualitative Inquiry of University Student’s Experiences of Exam Stress and Its Effect on Their Academic Performance. Hum. Arenas 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruutmann, T.; Kipper, H. Teaching Strategies for Direct and Indirect Instruction in Teaching Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th International Conference on Interactive Collaborative Learning; IEEE, September 2011; pp. 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridharan, K.; Raju, R. Impact of Teaching Strategies: Demonstration and Lecture Strategies and Impact of Teacher Effect on Academic Achievement in Engineering Education. Int. J. Educ. Sci. 2016, 14, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapranos, P. Teaching and Learning in Engineering Education – Are We Moving with the Times? Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 102, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Sanchez, C. Written Exams: How Effectively Are We Using Them? Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 228, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido, C.; Jiménez, J.-L.; Navarro, Y. Students’ Continuity Norms in the University and Exam Calendar: Do They Affect University Academic Performance? / Normas de Permanencia y Calendario de Exámenes: ¿afectan Al Rendimiento Académico Universitario? Cult. y Educ. 2019, 31, 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzilek, J.; Zdrahal, Z.; Vaclavek, J.; Fuglik, V.; Skocilas, J. Exploring Exam Strategies of Successful First Year Engineering Students. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge; ACM: New York, NY, USA, March 23, 2020; pp. 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K.J.; Cross, K.J. Board 73: Student Perceptions of Engineering Stress Culture. In Proceedings of the 2019 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.; Alvi, M.S.I.; Saeed, M.-D. Analysis of Factors Affecting the Stress Level of Engineering Students. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2010, 26, 681–686. [Google Scholar]

- Frady, K.; Brown, C.; High, K.; Hughes, C.; O’Hara, R.; Huang, S. Developing Two-Year College Student Engineering Technology Career Profiles. In Proceedings of the 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access Proceedings; ASEE Conferences; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, K.B.; Paysnick, A.A. Identity, Stress, and Behavioral and Emotional Problems in Undergraduates: Evidence for Interaction Effects. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2014, 55, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurford, D.P.; Ivy, W.A.; Winters, B.; Eckstein, H. Examination of the Variables That Predict Freshman Retention. Midwest Q. (Pittsb). 2017, 58, 248–251,302–317. [Google Scholar]

- Behere, S.P.; Yadav, R.; Behere, P.B. A Comparative Study of Stress Among Students of Medicine, Engineering, and Nursing. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2011, 33, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, N.; Murthy, P.; Kumar, Dn.; Chaudhury, S. Perceived Stress, Anxiety, and Coping States in Medical and Engineering Students during Examinations. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2019, 28, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, K.J.; Cross, K.J. Engineering Stress Culture: Relationships among Mental Health, Engineering Identity, and Sense of Inclusion. J. Eng. Educ. 2021, 110, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, M.B.; Golbin, R.A.; Velos, S.P.; Pocong, F.Q.; Bate, G.P.; South, P.E. Direct and Indirect Factors Affecting Course Repetition: A Secondary Data Analysis.; 2020.

- Tafreschi, D.; Thiemann, P. Doing It Twice, Getting It Right? The Effects of Grade Retention and Course Repetition in Higher Education. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2016, 55, 198–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arifin, M.; Widowati, W.; Farikhin, F.; Gudnanto, G. A Regression Model and a Combination of Academic and Non-Academic Features to Predict Student Academic Performance. TEM J. 2023, 12, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M. Effects of Academic and Nonacademic Factors on Undergraduate Electronic Engineering Program Retention. Walden Diss. Dr. Stud. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, C.F.; Cascallar, E.; Kyndt, E. Socio-Economic Status and Academic Performance in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukierman, U.R.; Aguero, M.; Silvestri, S.; Gonzalez, M.; Drangosch, J.; Gonzalez, C.; Ferrando, D.P.; Dellepiane, P. A Student-Centered Approach to Learning Mathematics and Physics in Engineering Freshmen Courses. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Engineering Education Forum - Global Engineering Deans Council (WEEF-GEDC); IEEE, November 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rincón Leal, L.; Vergel Ortega, M.; Paz Montes, L.S. Mobile Devices for the Development of Critical Thinking in the Learning of Differential Equations. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1408, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asino, T.I.; Pulay, A. Student Perceptions on the Role of the Classroom Environment on Computer Supported Collaborative Learning. TechTrends 2019, 63, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, M.; Galand, B.; Frenay, M. Transition from High School to University: A Person-Centered Approach to Academic Achievement. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2017, 32, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T. Predictors of Academic Performance and Education Programme Satisfaction in Occupational Therapy Students. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 79, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandarillas, M.A.; Elvira-Zorzo, M.N.; Rodríguez-Vera, M. The Impact of Parenting Practices and Family Economy on Psychological Wellbeing and Learning Patterns in Higher Education Students. Psicol. Reflexão e Crítica 2024, 37, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, M.; Abraham, C.; Bond, R. Psychological Correlates of University Students’ Academic Performance: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E. Can Higher Education Compensate for Society? Modelling the Determinants of Academic Success at University. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2016, 37, 970–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, J.; Sampaio, B. Family Background and Students’ Achievement on a University Entrance Exam in Brazil. Educ. Econ. 2013, 21, 38–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, W. Social and Cultural Capital and Learners’ Cognitive Ability: Issues and Prospects for Educational Relevance, Access and Equity towards Digital Communication in China. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 15549–15563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvias, D.; Katsis, A.; Limakopoulou, A. School Achievement and Family Background in Greece: A New Exploration of an Omnipresent Relationship. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2012, 22, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realyvásquez-Vargas, A.; Maldonado-Macías, A.A.; Arredondo-Soto, K.C.; Baez-Lopez, Y.; Carrillo-Gutiérrez, T.; Hernández-Escobedo, G. The Impact of Environmental Factors on Academic Performance of University Students Taking Online Classes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Mexico. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvanathan, M.; Hussin, N.A.M.; Azazi, N.A.N. Students Learning Experiences during COVID-19: Work from Home Period in Malaysian Higher Learning Institutions. Teach. Public Adm. 2023, 41, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A. University Students Online Learning System during COVID-19 Pandemic: Advantages, Constraints and Solutions 2020.

- Myyry, L.; Joutsenvirta, T. Open-Book, Open-Web Online Examinations: Developing Examination Practices to Support University Students’ Learning and Self-Efficacy. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 2015, 16, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.P. Adding Authenticity to Controlled Conditions Assessment: Introduction of an Online, Open Book, Essay Based Exam. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, S.G.; Heppard, C.J. Using Open-Book Exams to Enhance Student Learning, Performance, and Motivation. J. Eff. Teach. 2016, 16, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Y.N.; Husaini, A.; Syufiza, N.; Shukor, A. Factors Affecting Students’ Academic Performance: A Review. RES Mil. 2022, 12, 284–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kwabena, A.; Baafi, R. School Physical Environment and Student Academic Performance. Adv. Phys. Educ. 2020, 10, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurainan, A.M.; Mat Nazir, E.N.; Md Sabri, S. The Impact of Facilities Management on Students’ Academic Achievement. J. Intelek 2021, 16, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perks, T.; Orr, D.; Al-Omari, E. Classroom Re-Design to Facilitate Student Learning: A Case Study of Changes to a University Classroom. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2016, 16, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Chang, T.-S. Effects of Class Size and Attendance Policy on University Classroom Interaction in Taiwan. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2016, 53, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, I.Y. Class Size and Student Performance at a Public Research University: A Cross-Classified Model. Res. High. Educ. 2010, 51, 701–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, I.; Wan Yusoff, W.Z. Influence of Facilities Performance on Student’s Satisfaction in Northern Nigerian Universities. Facilities 2019, 37, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohel Parvez, M.; Tasnim, N.; Talapatra, S.; Ruhani, A.; Hoque, A.S.M.M. Assessment of Musculoskeletal Problems among Bangladeshi University Students in Relation to Classroom and Library Furniture. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2022, 103, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, C.M.; Coronado, M.C.; Medina, J.M. Thermal Comfort in Educational Buildings: The Classroom-Comfort-Data Method Applied to Schools in Bogotá, Colombia. Build. Environ. 2021, 194, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarreal Arroyo, Y.P.; Peñabaena-Niebles, R.; Berdugo Correa, C. Influence of Environmental Conditions on Students’ Learning Processes: A Systematic Review. Build. Environ. 2023, 231, 110051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, H.W.; Lechner, S.C.M.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Mobach, M.P.; Kort, H.S.M. Understanding How Indoor Environmental Classroom Conditions Influence Academic Performance in Higher Education. Facilities 2024, 42, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, S.; Weil, B. The Relationship between Comfort Perceptions and Academic Performance in University Classroom Buildings. J. Green Build. 2016, 11, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, T.; Kim, J.; Yeom, S. A Psychophysiological Effect of Indoor Thermal Condition on College Students’ Learning Performance through EEG Measurement. Build. Environ. 2020, 184, 107223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, P.; Miranda, M.T.; Montero, I.; Sepúlveda, F.J.; Valero-Amaro, V. Critical Review of the Literature on Thermal Comfort in Educational Buildings: Study of the Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Indoor Air 2023, 2023, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, E.; Zhang, D.; Hamida, A.; García-Sánchez, C.; Jonker, L.; de Boer, A.R.; Bruijning, P.C.J.L.; Linde, K.J.; Wouters, I.M.; Bluyssen, P.M. Ventilation and Thermal Conditions in Secondary Schools in the Netherlands: Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic Control and Prevention Measures. Build. Environ. 2023, 229, 109922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.J.; de la Hoz-Torres, M.L.; Martínez-Aires, M.D.; Ruiz, D.P. Thermal Perception in Naturally Ventilated University Buildings in Spain during the Cold Season. Buildings 2022, 12, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Vidal, I.; Martín-Garín, A.; González-Quintial, F.; Rico-Martínez, J.M.; Hernández-Minguillón, R.J.; Otaegi, J. Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Classrooms at the University of the Basque Country through a User-Informed Natural Ventilation Demonstrator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría-Sala, A.; Clèries Tardío, E.; Casals, L.C.; Macarulla, M.; Salom, J. CO2 Concentrations and Thermal Comfort Analysis at Onsite and Online Educational Environments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus, T.; Moldovan, R.; Albu, H.; Beu, D. Impact of Pandemic Safety Measures on Students’ Thermal Comfort—Case Study: Romania. Buildings 2023, 13, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.T.; Romero, P.; Valero-Amaro, V.; Arranz, J.I.; Montero, I. Ventilation Conditions and Their Influence on Thermal Comfort in Examination Classrooms in Times of COVID-19. A Case Study in a Spanish Area with Mediterranean Climate. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 240, 113910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de la Hoz-Torres, M.L.; Aguilar, A.J.; Costa, N.; Arezes, P.; Ruiz, D.P.; Martínez-Aires, M.D. Reopening Higher Education Buildings in Post-epidemic COVID-19 Scenario: Monitoring and Assessment of Indoor Environmental Quality after Implementing Ventilation Protocols in Spain and Portugal. Indoor Air 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, P.; Valero-Amaro, V.; Isidoro, R.; Miranda, M.T. Analysis of Determining Factors in the Thermal Comfort of University Students. A Comparative Study between Spain and Portugal. Energy Build. 2024, 308, 114022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Mino, L. A Study on Student Perceptions of Higher Education Classrooms: Impact of Classroom Attributes on Student Satisfaction and Performance. Build. Environ. 2013, 70, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.M.; Coronado, M.C.; Medina, J.M. Classroom-Comfort-Data: A Method to Collect Comprehensive Information on Thermal Comfort in School Classrooms. MethodsX 2019, 6, 2698–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018 51 2018, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JBI <i>JBI Manual for Evidence, Synthesis</i>; Aromataris, E. JBI JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI, 2020; ISBN 9780648848806.

- Cross, K.J.; Jensen, K.J. Work in Progress: Understanding Student Perceptions of Stress as Part of Engineering Culture. Am. Soc. Eng. Educ. Conf. Proc. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gratchev, I.; Howell, S.; Stegen, S. Academics’ Perception of Final Examinations in Engineering Education. Australas. J. Eng. Educ. 2024, 29, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fojcik, M.; Fojcik, M.; Stafsnes, J.A.; Pollen, B. Identification of School Depended Factors, Which Can Affect Students’ Performance on Assessments.; 21 June 2019; pp. 146–150.

- Arnold, I. Resitting or Compensating a Failed Examination: Does It Affect Subsequent Results? Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivin, J.S.G.; Song, Y.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, P. Temperature and High-Stakes Cognitive Performance: Evidence from the National College Entrance Examination in China; Cambridge, MA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, H.W.; Krijnen, W.P.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Mobach, M.P.; Kort, H.S.M. Positive Effects of Indoor Environmental Conditions on Students and Their Performance in Higher Education Classrooms: A between-Groups Experiment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Patel, P.C. Weather and High-Stakes Exam Performance: Evidence from Student-Level Administrative Data in Brazil. Econ. Lett. 2021, 199, 109698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.C.; Mui, K.W.; Wong, L.T.; Chan, W.Y.; Lee, E.W.M.; Cheung, C.T. Student Learning Performance and Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) in Air-Conditioned University Teaching Rooms. Build. Environ. 2012, 49, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y. How Does Indoor Physical Environment Differentially Affect Learning Performance in Various Classroom Types? Build. Environ. 2023, 234, 110189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.M. Effects of Heat on Mathematics Test Performance in Vietnam. Asian Econ. J. 2022, 36, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.L. A Simple Model to Determine the Efficient Duration of Exams. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2021, 81, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fengler, M.; Ostafichuk, P.M. Successes with Two-Stage Exams in Mechanical Engineering. Proc. Can. Eng. Educ. Assoc. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhute, V.J.; Campbell, J.; Kogelbauer, A.; Shah, U. V; Brechtelsbauer, C. Moving to Timed Remote Assessments: The Impact of COVID-19 on Year End Exams in Chemical Engineering at Imperial College London. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 2760–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-F.; Tsai, C.-Y. The Impact of School Classroom Chair Depth and Height on Learning Tasks. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Sapri, M.; Sipan, I. Academic Buildings and Their Influence on Students’ Wellbeing in Higher Education Institutions. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 115, 1159–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, F.; Soto, G.M. Does the Exam Calendar Affect the Probability of Success? In Proceedings of the INTED2015 Proceedings; 2015; pp. 3617–3625. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, I.; Tena, J. de D. The Impact of Instruction Time and the School Calendar on Academic Performance: A Natural Experiment.; 2021.

- Manzano Agugliaro, F.; Salmerón-Manzano, E.; Martínez, F.; Nievas-Soriano, B.; Zapata-Sierra, A.J. Impact Analysis on Academic Performance of the Change in the Extraordinary Resit Exam Period of September Análisis Del Impacto En Los Resultados Académicos Del Cambio de La Convocatoria Extraordinaria de Exámenes de Septiembre. ESPIRAL. Cuad. DEL Profr. 2023, 16, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.G.; Baars, G.J.A.; Hermus, P.; van der Molen, H.T.; Arnold, I.J.M.; Smeets, G. Changes in Examination Practices Reduce Procrastination in University Students. Eur. J. High. Educ. 2022, 12, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonis, S.A.; Hudson, G.I. Performance of College Students: Impact of Study Time and Study Habits. J. Educ. Bus. 2010, 85, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Mora, C.; García, J.A.; Molina, A. What Is the Key to Academic Success? An Analysis of the Relationship between Time Use and Student Performance / ¿Dónde Está La Clave Del Éxito Académico? Un Análisis de La Relación Entre El Uso Del Tiempo y El Rendimiento Académico. 2016, 28, 157–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grave, B.S. The Effect of Student Time Allocation on Academic Achievement. Educ. Econ. 2011, 19, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezigalla, A.; Eleragi, A.; Elkhalifa, M.; Mohammed, A. Comparison between Students’ Perception and Examination Validity, Reliability and Items Difficulty: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sudan J. Med. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photopoulos, P.; Tsonos, C.; Stavrakas, I.; Triantis, D. Preference for Multiple Choice and Constructed Response Exams for Engineering Students with and without Learning Difficulties. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer Supported Education; SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications, 2021; pp. 220–231.

- Clemmer, R.; Gordon, K.; Vale, J. Will That Be on the Exam? - Student Perceptions of Memorization and Success in Engineering. Proc. Can. Eng. Educ. Assoc. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doghonadze, N.; Demir, H. Critical Analysis of Open-Book Exam for University Students. In Proceedings of the ICERI2013 Proceedings; IATED; 2013; pp. 4851–4857. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-C.; Lai, Y.-L. A Brief Review of Researches on the Use of Graphing Calculator in Mathematics Classrooms. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2015, 14, 163–172. [Google Scholar]

- Bouck, E.C.; Bouck, M.K.; Hunley, M. The Calculator Effect. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 2015, 30, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S.K.; Eisenberg, D. Mental Health and Academic Attitudes and Expectations in University Populations: Results from the Healthy Minds Study. J. Ment. Heal. 2018, 27, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceijas, C.; Waldhäusl, S.; Lambert, N.; Cassar, S.; Bello-Corassa, R. Determinants of Health-Related Lifestyles among University Students. Perspect. Public Health 2017, 137, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.M.; Kuśnierz, C.; Bokszczanin, A. Examining Anxiety, Life Satisfaction, General Health, Stress and Coping Styles During COVID-19 Pandemic in Polish Sample of University Students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2020, 13, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jokhadar, A.; Alnusairat, S.; Abuhashem, Y.; Soudi, Y. The Impact of Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) in Design Studios on the Comfort and Academic Performance of Architecture Students. Buildings 2023, 13, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmana, A.; Jamaluddin, A.S. The Effects of Mental Health Issues and Academic Performance. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 6, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.; Chapman, C.; Richardson, T.; Elliott, P.; Roberts, R. The Relationship between Mental and Physical Health: A Longitudinal Analysis with British Student. J. Public Ment. Health 2022, 21, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2017: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. 2017.

- McCartney, K.J.; Fergus Nicol, J. Developing an Adaptive Control Algorithm for Europe. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, M.S.J.; Talukdar, T.H.; Singh, M.K.; Baten, M.A.; Hossen, M.S. Status of Thermal Comfort in Naturally Ventilated University Classrooms of Bangladesh in Hot and Humid Summer Season. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 32, 101700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO ISO 7730:2005. Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment — Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. 2005.

- ISO ISO 7726:1998. Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment Instruments for Measuring Physical Quantities. 1998.

- Tenza-Abril, A.J.; López, I.; Andreu Vallejo, L.; Vives Bonete, I.; Vicente Pastor, A. de; López Moraga, A.; García Andreu, C.; Saval Pérez, J.M.; Rivera Page, J.A.; Ibáñez Gosálvez, J.F. Análisis Del Número de Matrículas Medias En El Grado de Ingeniería Civil Para La Propuesta de Mejoras En El Plan de Estudios; Alicante (España), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.-J. Effects of the Distribution of Occupants in Partially Occupied Classrooms. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 140, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Morera, L.; Ruiz-Bustos, R.; Cejas-Molina, M.A.; Olivares-Olmedilla, J.L.; García-Hernández, L.; Palomo-Romero, J.M. Understanding Why Women Don’t Choose Engineering Degrees. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2021, 31, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Iglesias, E.; Epifanio, I.; Estrade, S.; Mas de les Valls, E. Gender Perspective in STEM Disciplines in Spain Universities. In; 2022; pp. 165–179.

- Neematia, N.; Hooshangib, R.; Shuridehc, A. ScienceDirect International Conference on Current Trends in ELT An Investigation into the Learners ’ Attitudes towards Factors Affecting Their Exam Performance : A Case from Razi University.; 2014.

- Granados-Ortiz, F.-J.; Gómez-Merino, A.I.; Jiménez-Galea, J.J.; Santos-Ráez, I.M.; Fernandez-Lozano, J.J.; Gómez-de-Gabriel, J.M.; Ortega-Casanova, J. Design and Assessment of Survey in a 360-Degree Feedback Environment for Student Satisfaction Analysis Applied to Industrial Engineering Degrees in Spain. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigopoulos, G. Assessment and Feedback as Predictors for Student Satisfaction in UK Higher Education. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Comput. Sci. 2022, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, K.L.; Heilly, S.D.; Ehlinger, E. Colds and Influenza-Like Illnesses in University Students: Impact on Health, Academic and Work Performance, and Health Care Use. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 40, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Cengage, 2019; ISBN 9781473756540.

- Brink, H.W.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Mobach, M.P.; Kort, H.S.M. Classrooms’ Indoor Environmental Conditions Affecting the Academic Achievement of Students and Teachers in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Wargocki, P.; Lian, Z. Quantitative Measurement of Productivity Loss Due to Thermal Discomfort. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Ruiz, P.; Barbadilla-Martín, E.; Guadix, J.; Muñuzuri, J. A Field Study on Adaptive Thermal Comfort in Spanish Primary Classrooms during Summer Season. Build. Environ. 2021, 203, 108089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgnati, S.P.; Ansaldi, R.; Filippi, M. Thermal Comfort in Italian Classrooms under Free Running Conditions during Mid Seasons: Assessment through Objective and Subjective Approaches. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 2010-2024 | Before 2010 |

| Document type | Papers and congress communications | Doctoral dissertations, books, reports, etc. |

| Publication stage | Final publication | Papers under review |

| Language | English | Other language |

| Item no. | Identified factor | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Level of nervousness | [15,23,25,28,29,30,31,78,79,80] |

| 2 | Pressure from failed exam attempts | [30,31,81] |

| 3 | Classroom environmental conditions | [61,62,63,64,74,82,83,84,85,86,87] |

| 4 | Family/personal situation | [34,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] |

| 5 | Exam duration | [88,89,90] |

| 6 | Table and chair comfort | [55,58,59,74,91,92] |

| 7 | Coincidence or closeness in time with other exams | [20,21,93,94,95,96,97] |

| 8 | Exam preparation | [6,13,21,97,98,99] |

| 9 | Exam difficulty | [1,10,14,19,100,101,102] |

| 10 | Tools used (calculators, notes, etc.) | [35,36,49,50,51,103,104,105] |

| 11 | Health condition (physical or mental) | [22,29,64,92,106,107,108,109,110,111] |

| Evaluation | Question | Answer choice | Scale | Evaluation clustering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensation (TSV) | How would you describe the classroom climate during exam? | Hot | +3 | Heat discomfort |

| Warm | +2 | |||

| Slightly warm | +1 | Comfort | ||

| Neutral | 0 | |||

| Slightly cool | -1 | |||

| Cool | -2 | Cold discomfort | ||

| Cold | -3 | |||

| Satisfaction (TCV) | During the exam, how did you feel, in relation to the classroom climate? | Very comfortable | +2 | Comfort |

| Slightly comfortable | +1 | Neutral | ||

| Comfortable | 0 | |||

| Slightly uncomfortable | -1 | |||

| Very uncomfortable | -2 | Discomfort |

| Total | Regular exam period | Special exam period | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of days analysed | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| No. of exams | 32 | 20 | 12 |

| No. of classrooms | 9 | 9 | 3 |

| No. of surveys | 786 | 487 | 299 |

| Avg. number of students per exam | 24.56 | 24.35 | 24.92 |

| Max. number of students per exam | 71 | 71 | 46 |

| Min. number of students per exam | 4 | 4 | 7 |

| Total variance explained 1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial eigenvalues | Extraction sums of charges squared | Rotational sums of squared loads | ||||||

| Total | % of variance | % accumulated | Total | % of variance | % accumulated | Total | % of variance | % accumulated | |

| 1 | 4.454 | 40.491 | 40.491 | 4.454 | 40.491 | 40.491 | 2.780 | 25.270 | 25.270 |

| 2 | 0.997 | 9.065 | 49.556 | 0.997 | 9.065 | 49.556 | 1.846 | 16.778 | 42.048 |

| 3 | 0.926 | 8.414 | 57.970 | 0.926 | 8.414 | 57.970 | 1.536 | 13.964 | 56.012 |

| 4 | 0.890 | 8.087 | 66.057 | 0.890 | 8.087 | 66.057 | 1.105 | 10.045 | 66.057 |

| 5 | 0.760 | 6.913 | 72.970 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.673 | 6.120 | 79.090 | ||||||

| 7 | 0.557 | 5.063 | 84.153 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.510 | 4.635 | 88.788 | ||||||

| 9 | 0.456 | 4.144 | 92.932 | ||||||

| 10 | 0.436 | 3.960 | 96.892 | ||||||

| 11 | 0.342 | 3.108 | 100.000 | ||||||

| Rotated component matrix 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Component | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Level of nervousness | 0.618 | 0.344 | 0.047 | 0.067 |

| Pressure from failed exam attempts | 0.619 | 0.374 | 0.018 | 0.147 |

| Classroom environmental conditions | 0.156 | 0.064 | 0.070 | 0.931 |

| Family/personal situation | 0.331 | 0.744 | 0.163 | 0.023 |

| Exam duration | 0.407 | 0.283 | 0.508 | 0.264 |

| Table and chair comfort | 0.049 | 0.112 | 0.882 | 0.010 |

| Coincidence or closeness in time with other exams | 0.623 | 0.037 | 0.427 | -0.181 |

| Exam preparation | 0.792 | 0.163 | 0.094 | 0.117 |

| Exam difficulty | 0.766 | 0.104 | 0.230 | 0.228 |

| Tools used (calculators, notes, etc.) | 0.314 | 0.430 | 0.552 | 0.203 |

| Health condition (physical or mental) | 0.110 | 0.845 | 0.216 | 0.045 |

| FACTOR 1 Previous conditions |

FACTOR 2 Personal conditions |

FACTOR 3 Material Conditions |

FACTOR 4 Environmental conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level of nervousness Failed exam attempts Coincidence in time with other exams Exam preparation Exam difficulty |

Family/personal situation Health condition |

Exam duration Table and chair comfort |

Environmental conditions under which the exam takes place |

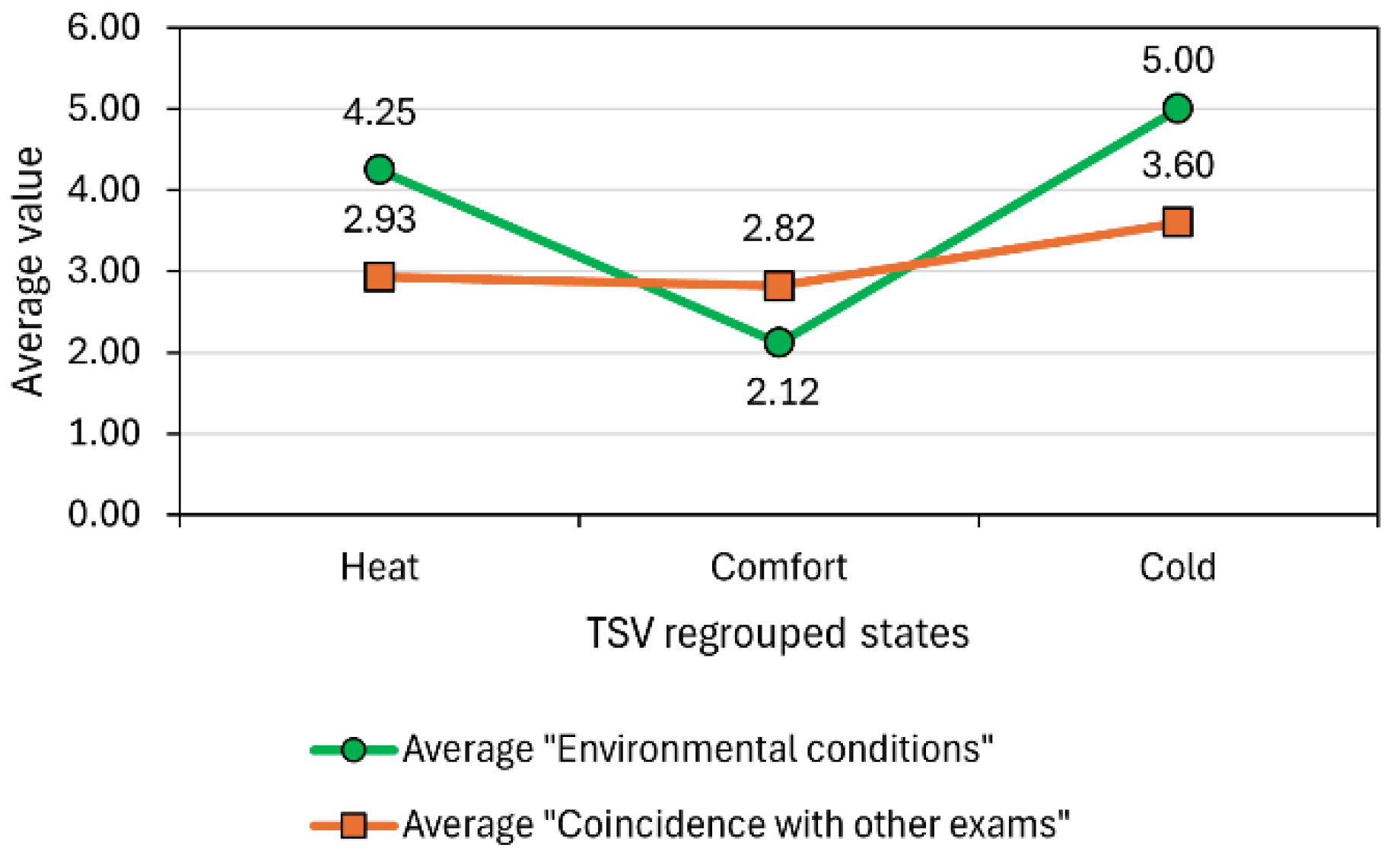

| TSV clustering for assessment | Statistics | Factor number | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Heat discomfort | Mean | 2.59 | 2.12 | 4.25 | 1.83 | 2.09 | 2.02 | 2.93 | 3.00 | 3.31 | 1.64 | 1.63 |

| Median | 2.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 3.00 | 4.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mode | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Comfort | Mean | 2.56 | 1.87 | 2.12 | 1.97 | 1.90 | 2.05 | 2.82 | 2.61 | 2.56 | 1.63 | 1.81 |

| Median | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Mode | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Cold discomfort | Mean | 2.53 | 2.13 | 5.00 | 2.20 | 2.13 | 2.40 | 3.60 | 3.07 | 3.00 | 1.93 | 1.93 |

| Median | 2.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| Mode | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Statistics | TSV clustering for assessment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat discomfort | Comfort | Cold discomfort | |

| Mean | 4.25 | 2.12 | 5.00 |

| Median | 4.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 |

| Mode | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Std. deviation | 0.681 | 0.968 | 0.000 |

| 25 percentile | 4.00 | 1.00 | 5.00 |

| Ranking | 1º | 5º | 1º |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).