Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Novelty and Scientific Contributions

1.2.1. Dynamical Variational Principles

1.2.2. Positive Feedback Model of Self-Organization

1.2.3. Average Action Efficiency (AAE)

1.2.4. Agent-Based Modeling (ABM)

1.2.5. Intervention and Control in Complex Systems

1.2.6. Average Action-Efficiency as a Predictor of System Robustness:

1.2.7. Philosophical Contribution

1.2.8. Novel Conceptualization of Evolution as a Path to Increased Action Efficiency:

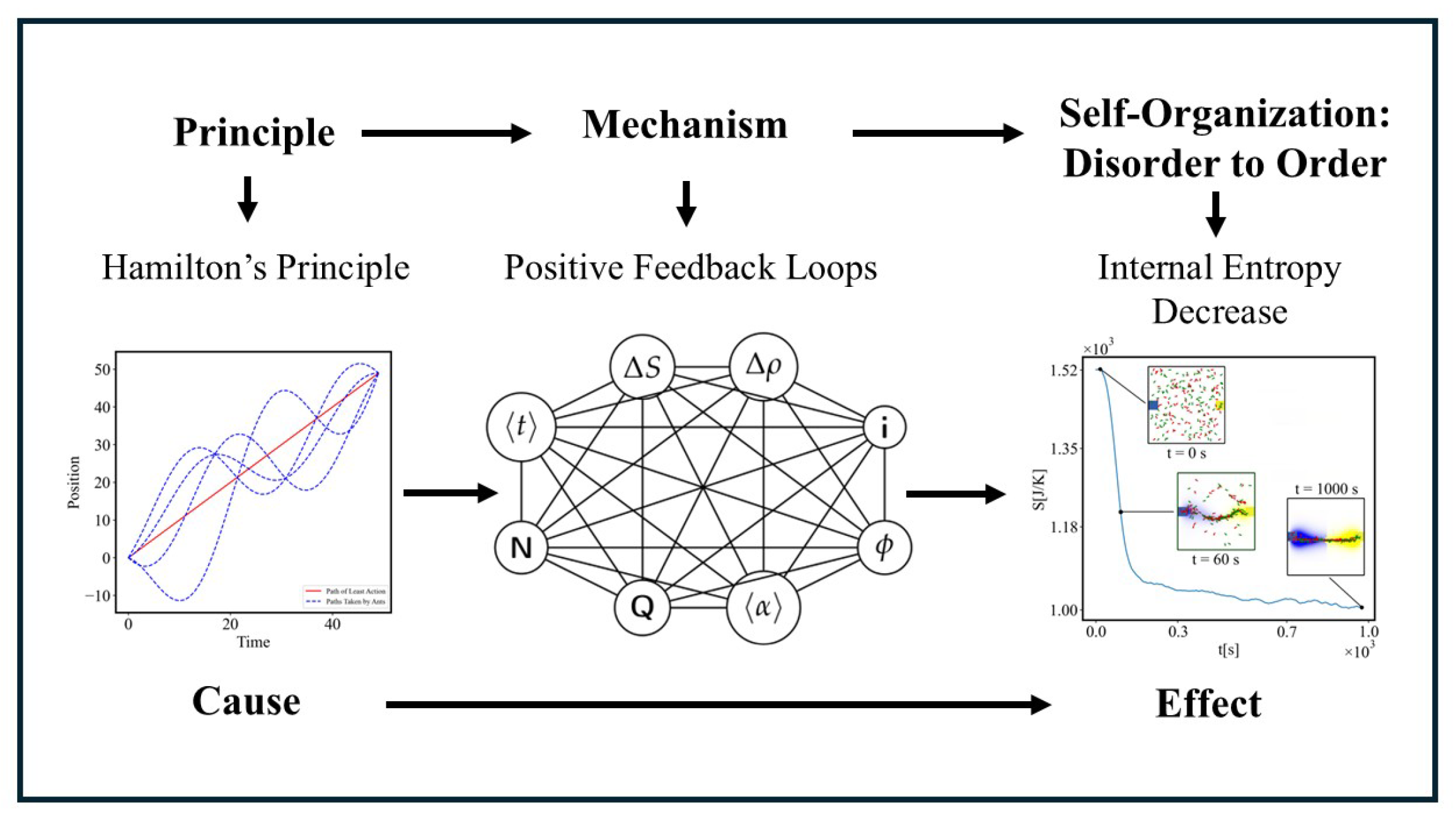

1.3. Overview of the Theoretical Framework

1.4. Hamilton’S Principle and Action Efficiency

1.5. Mechanism of Self-Organization

1.6. Negative Feedback

1.7. Unit-Total Dualism

1.8. Unit Total Dualism Examples

1.9. Action Principles in this Simulation, Potential Well

1.10. Research Questions and Hypotheses

- How can a dynamical variational action principle explain the continuous self-organization, evolution, and development of complex systems?

- Can Average Action Efficiency (AAE) be a measure of the level of organization of complex systems?

- Can the proposed positive feedback model accurately predict the self-organization processes in systems?

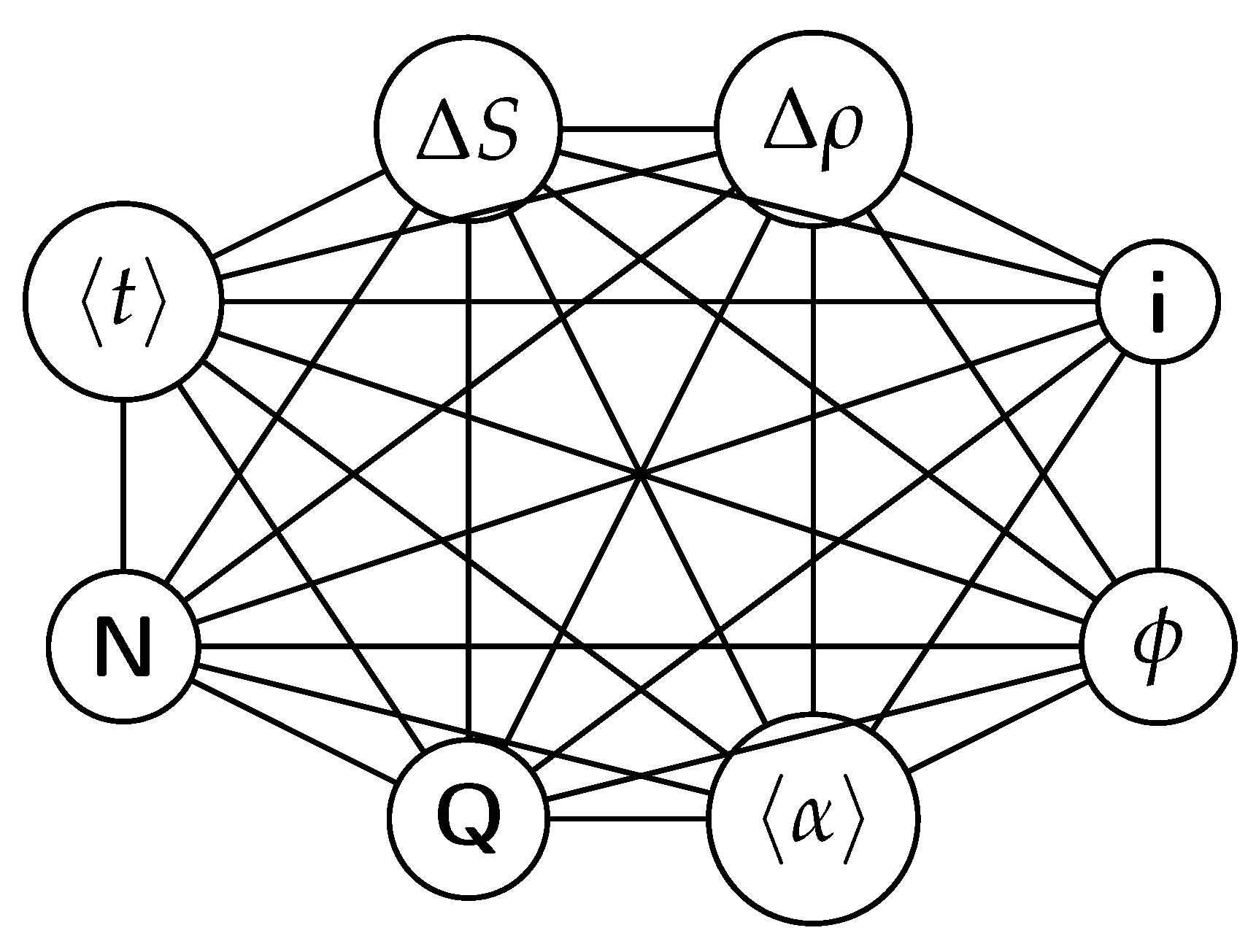

- What are the relationships between various system characteristics, such as AAE, total action, order parameters, entropy, flow rate, and others , and how do the simulation results compare with real-world data?

- A dynamical variational action principle may explain the continuous self-organization, evolution and development of complex systems.

- AAE may a valid and reliable measure of organization that can be applied to complex systems.

- The model may accurately predict the most organized state based on AAE.

- The model may predict the power-law relationships between system characteristics that can be quantified, and they can compare to the results of some real-world systems.

1.11. Summary of the Specific Objectives of the Paper

2. Building the Model:

2.1. Hamilton’s Principle of Stationary Action for a System

2.2. An Example of True Action Minimization: Conditions

- The agents are free particles, not subject to any forces, so the potential energy is a constant and can be set to be zero because the origin for the potential energy can be chosen arbitrarily, therefore . Then, the Lagrangian L of the element is equal only to the kinetic energy of that element:where m is the mass of the element, and v is its speed.

- We are assuming that there is no energy dissipation in this system, so the Lagrangian of the element is a constant:

- The mass m and the speed v of the element are assumed to be constants.

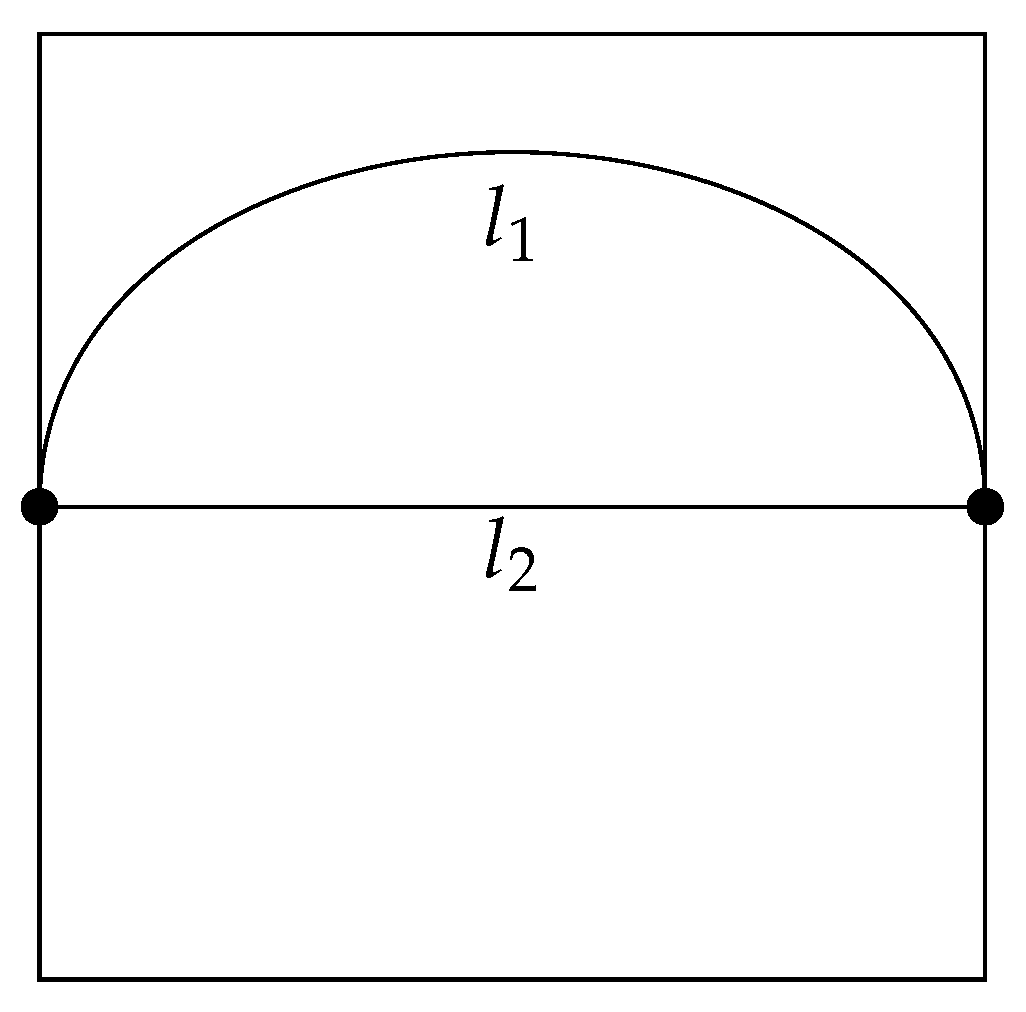

- The start point and the end point of the trajectory of the element are fixed at opposite sides of a square (see Figure A1). This produces the consequence that the action integral cannot become zero, because the endpoints cannot get infinitely close together:

- The action integral cannot become infinity, i.e., the trajectory cannot become infinitely long:

- In each configuration of the system, the actual trajectory of the element is determined as the one with the Least Action from Hamilton’s Principle:

- The medium inside the system is isotropic (it has all its properties identical in all directions). The consequence of this assumption is that the constant velocity of the element allows us to substitute the interval of time with the length of the trajectory of the element.

- The second variation of the action is positive, because , and , therefore the action is a true minimum.

2.3. Building the Model

2.4. Analysis of System States

2.5. Average Action Efficiency (AAE)

2.6. Multi-Agent

2.7. Using Time

2.8. An Example

2.9. Unit-Total (Local-Global) Dualism

3. Simulations Model

- Kinetic Energy (T): In our simulation, the ants have a constant mass m, and their kinetic energy is given by:

- Effective Potential Energy (V): The potential energy due to pheromone concentration at position and time t can be modeled as:

- Minimum: If the second variation of the action is positive, the path corresponds to a minimum of the action.

- Saddle Point: If the second variation of the action can be both positive and negative depending on the direction of the variation, the path corresponds to a saddle point.

- Maximum: If the second variation of the action is negative, the path corresponds to a maximum of the action.

- Kinetic Energy Term : The second variation of the kinetic energy is typically positive, as it involves terms like .

- Potential Energy Term : The second variation of the effective potential energy depends on the nature of . If C is a smooth, well-behaved function, the second variation can be analyzed by examining .

- Kinetic Energy Contribution: Positive definite, contributing to a positive second variation.

- Effective Potential Energy Contribution: Depends on the curvature of . If has regions where its second derivative is positive, the effective potential energy contributes positively, and vice versa.

- The kinetic energy term tends to make the action a minimum.

- The potential energy term, depending on the pheromone concentration field, can contribute both positively and negatively.

3.0.1. Effects of Wiggle Angle and Pheromone Evaporation on the Action

3.1. Considering the Nature of the Action

- Before Changes: In a simpler model without wiggle angles and evaporation, the action might be stationary at certain paths.

- After Changes: With wiggle angle variability and pheromone evaporation, the action is less likely to be stationary. Instead, the system continuously adapts, and the action varies over time.

- Saddle Point: The action is likely to be at a saddle point due to the dynamic balancing of factors. The system may have directions in which the action decreases (due to pheromone decay) and directions in which it increases (due to path variability).

- Minimum: If the system stabilizes around a certain path that balances the stochastic wiggle and the decaying pheromones effectively, the action might approach a local minimum. However, this is less likely in a highly dynamic system.

- Maximum: It is unusual for the action in such optimization problems to represent a maximum because that would imply an unstable and inefficient path being preferred, which is contrary to observed behavior.

3.1.1. Practical Implications

3.2. Dynamic Action

3.2.1. Euler-Lagrange Equation

3.2.2. Updating Parameters

3.2.3. Practical Implementation

3.2.4. Solving the Equations

- Numerical Methods: Usually, these systems are too complex for analytical solutions, so numerical methods (e.g., finite difference methods, Runge-Kutta methods) are used to solve the differential equations governing and .

- Optimization Algorithms: Algorithms like gradient descent, genetic algorithms, or simulated annealing can be used to find optimal paths and parameter updates.

3.3. Specific Details in Our Simulation

3.4. Gradient Based Approach

3.5. Summary

4. Mechanism

4.1. Exponential Growth and Size-Complexity Rule

4.2. a Model for the Mechanism of Self-Organization

4.2.1. Systems with Constant Coefficients:

- For linear systems with constant coefficients, the solutions often involve exponential functions. This is because the system can be expressed in terms of matrix exponentials, leveraging the properties of constant coefficient matrices.

- Even in these cases, if the coefficient matrix is defective (non-diagonalizable), the solutions may include polynomial terms multiplied by exponentials.

4.2.2. Systems with Variable Coefficients:

- When the coefficients are functions of the independent variable (e.g., time), the solutions may involve integrals, special functions (like Bessel or Airy functions), or other non-exponential forms.

- The lack of constant coefficients means that the superposition principle doesn’t yield purely exponential solutions, and the system may not have solutions expressible in closed-form exponential terms.

4.2.3. Higher-Order Systems and Resonance:

- In some systems, especially those modeling physical phenomena like oscillations or circuits, the solutions might involve trigonometric functions, which are related to exponentials via Euler’s formula but are not themselves exponential functions in the real domain.

- Resonant systems can exhibit behavior where solutions grow without bound in a non-exponential manner.

4.3. Model Solutions

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- y and x are the variables.

- k is a constant.

- n is the exponent.

- is a term that accounts for deviations.

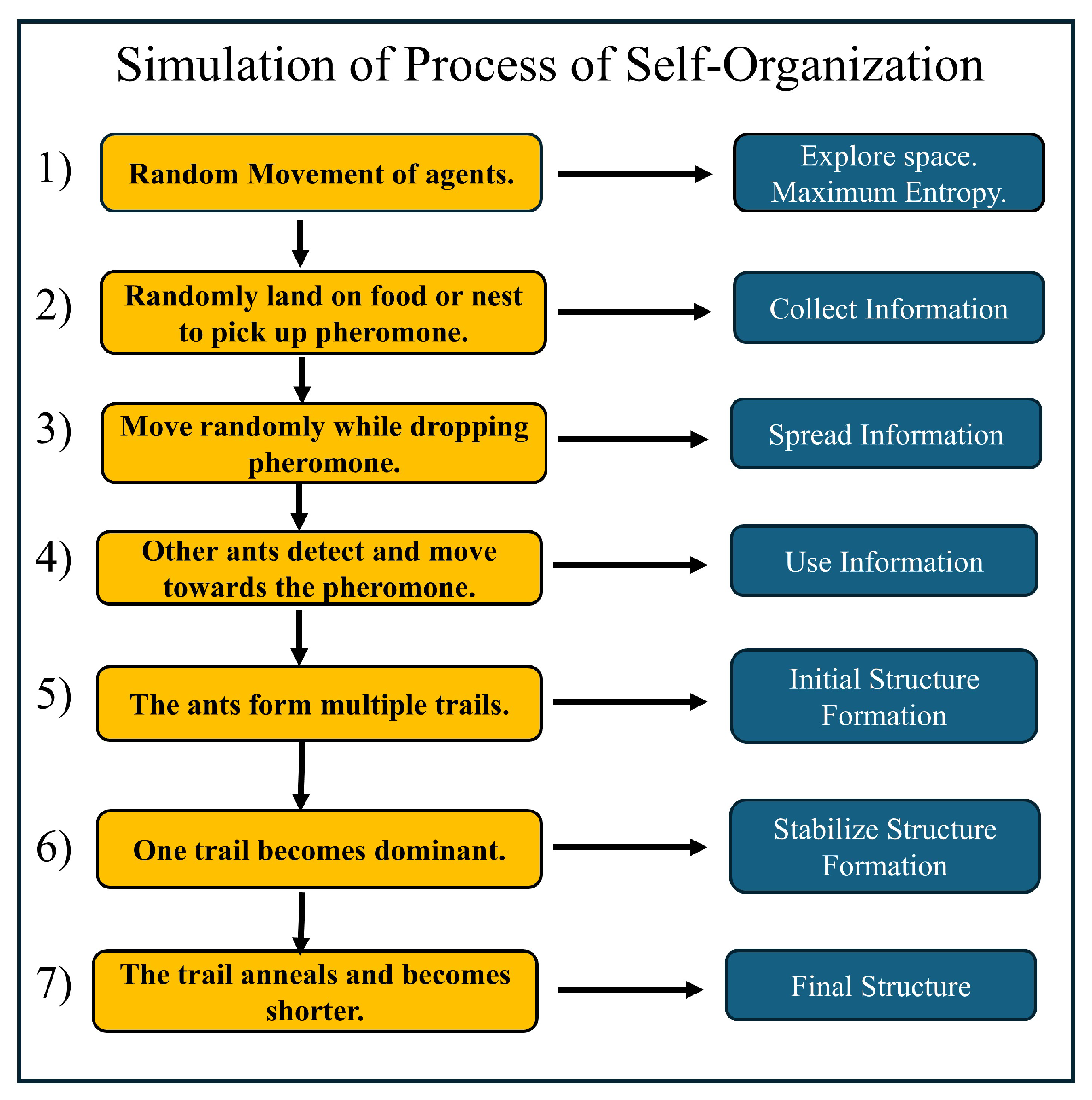

5. Simulation Methods

5.1. Agent-Based Simulations Approach

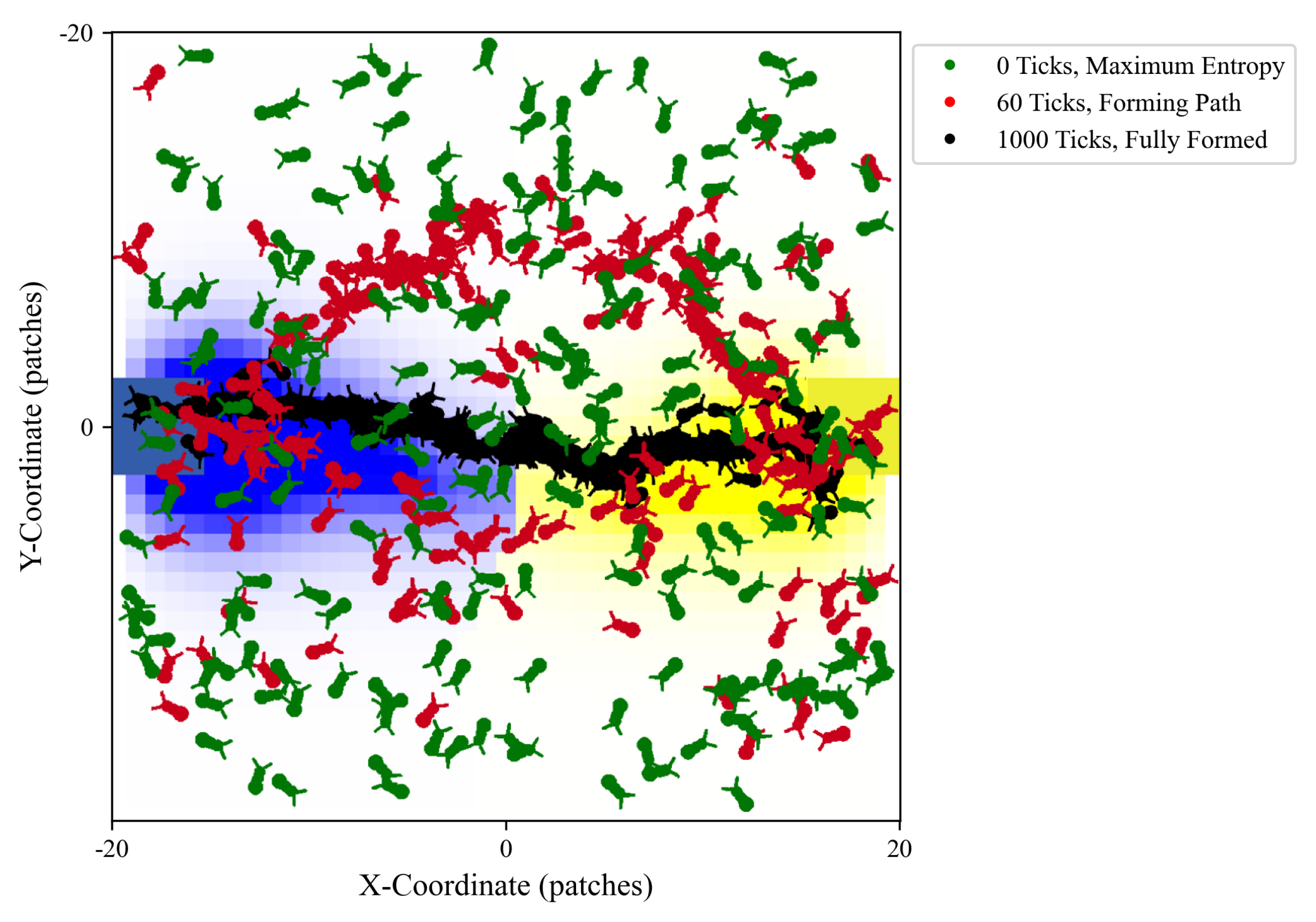

5.2. Illustration of the simulation

5.2.1. Flow diagram

5.2.2. Stages of Self-Organization in the Simulation

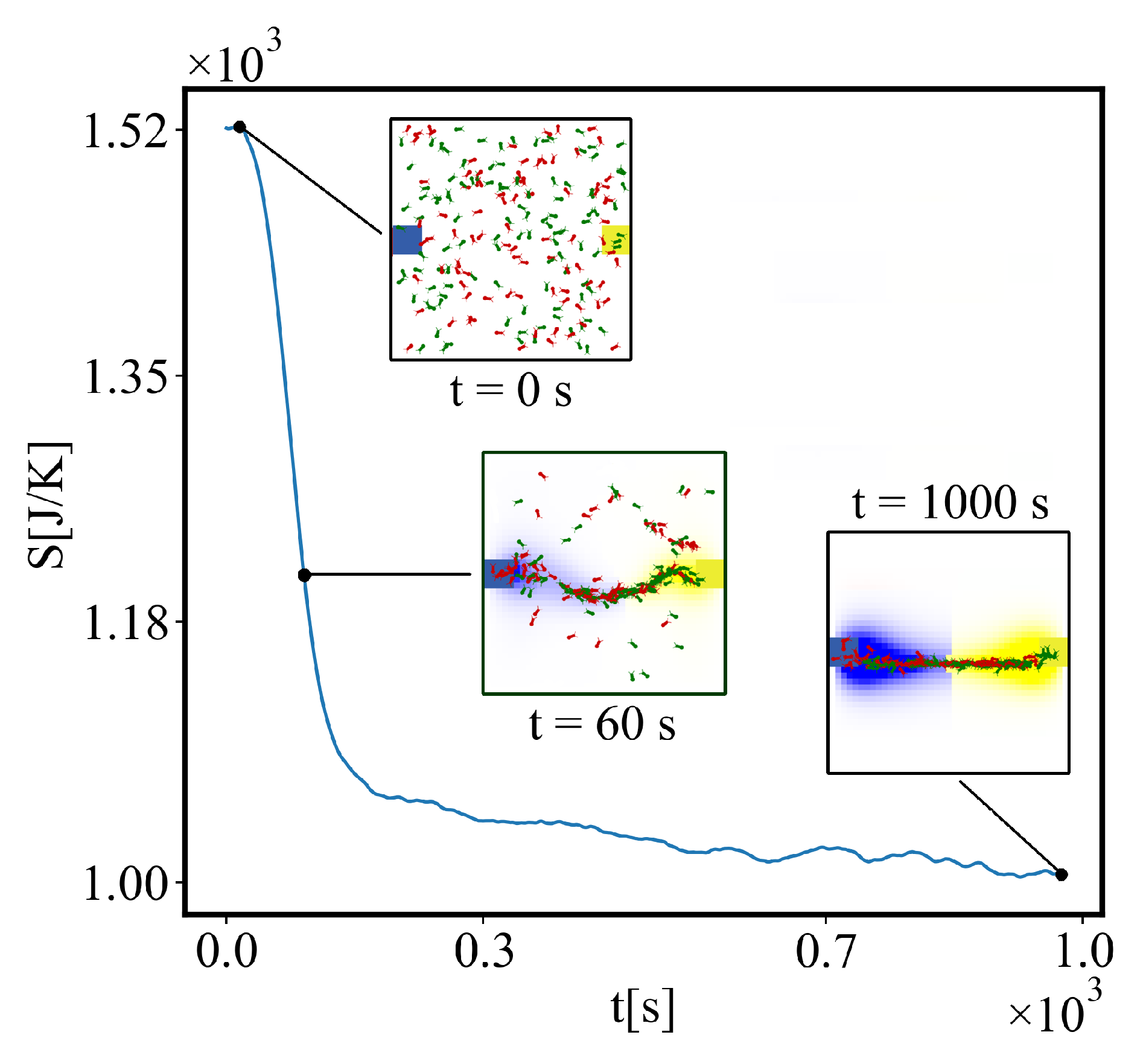

5.2.3. Time Evolution of Self-Organization

- Upper Insert (First Tick): Shows the initial state, where the ants (green and red) are randomly distributed, representing maximum entropy and a lack of order. The nest is indicated by a blue square, and the food by a yellow square.

- Middle Insert (Tick 60): Depicts the transition phase, where ants begin exploring multiple possible paths between the nest and food, leading to a reduction in entropy as structure starts forming.

- Lower Insert (Final Tick): Displays the final state, where the ants converge on the most efficient single path, minimizing entropy and achieving a highly organized system.

5.3. Program Summary

5.4. Analysis Summary

5.5. Average Path Length

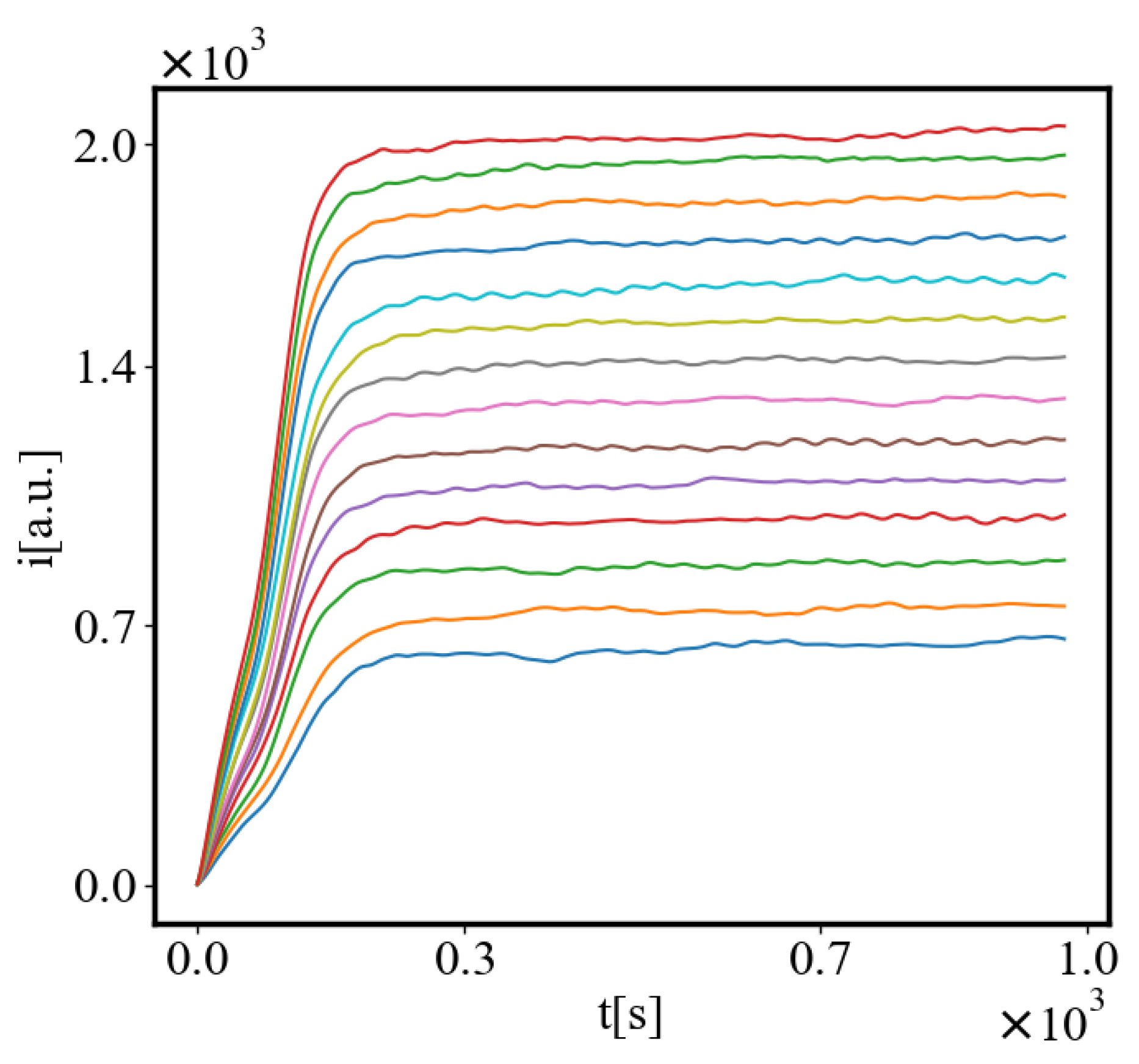

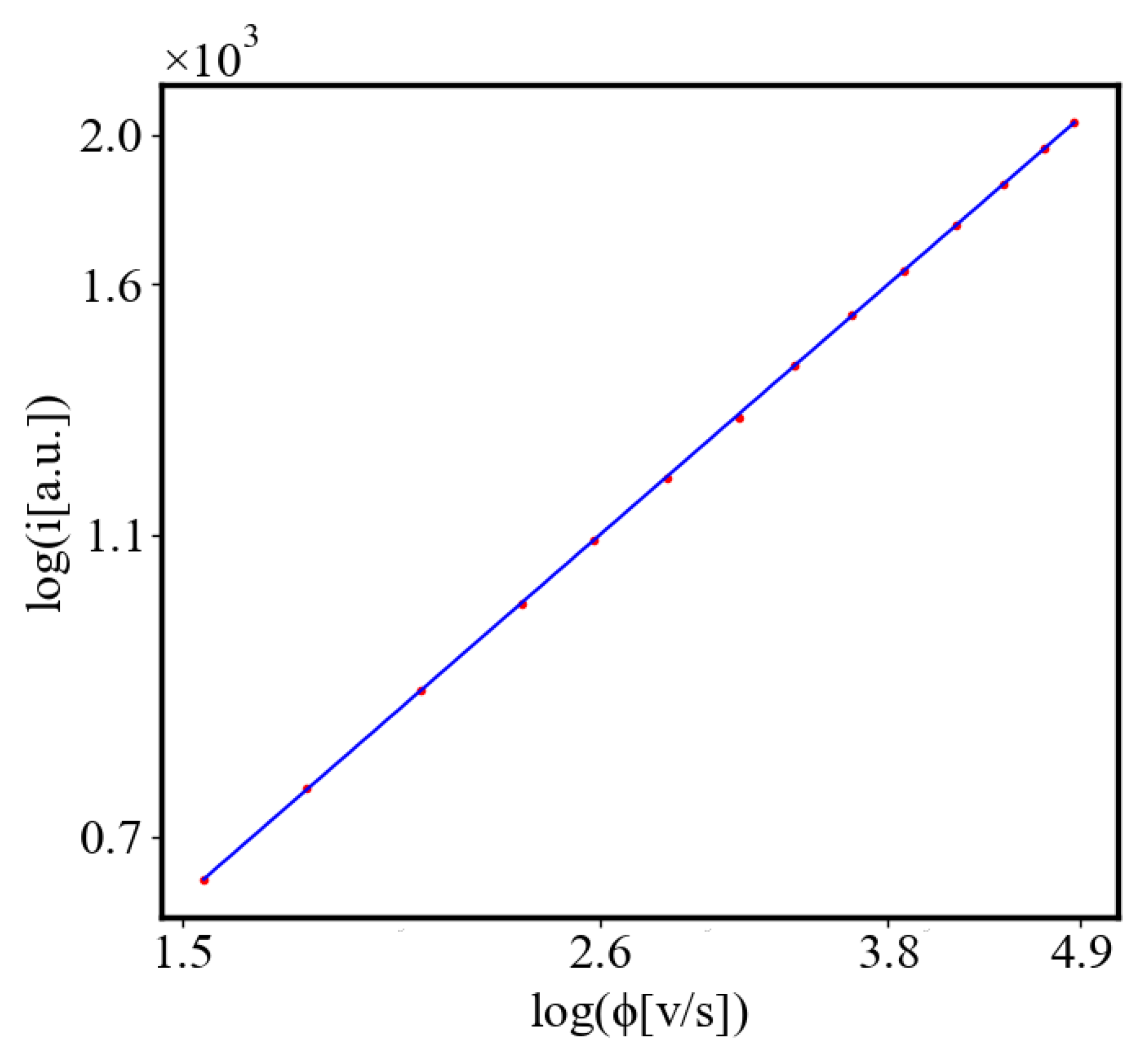

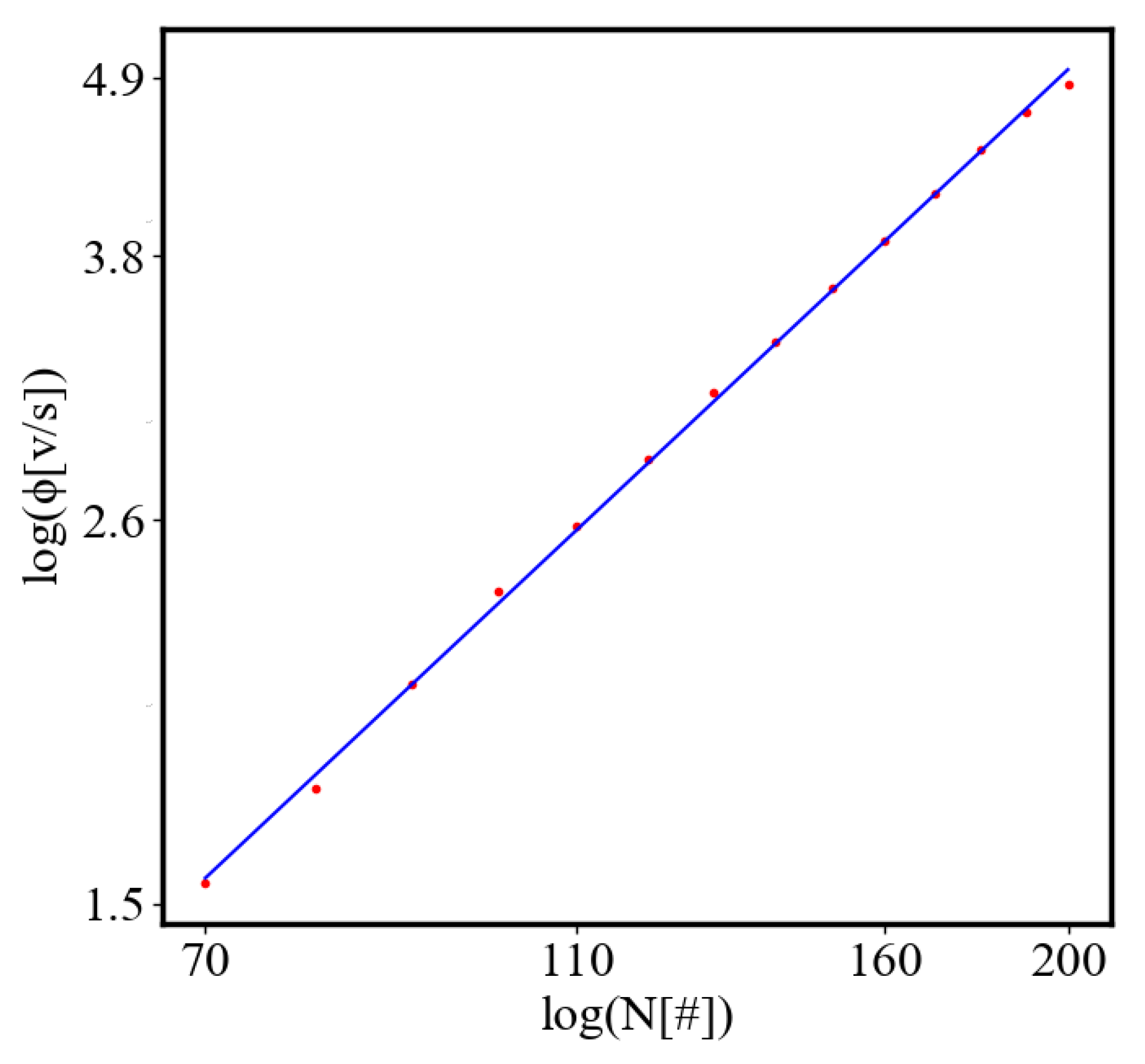

5.6. Flow Rate

5.7. Final Pheromone

5.8. Total Action

5.9. Average Action Efficiency

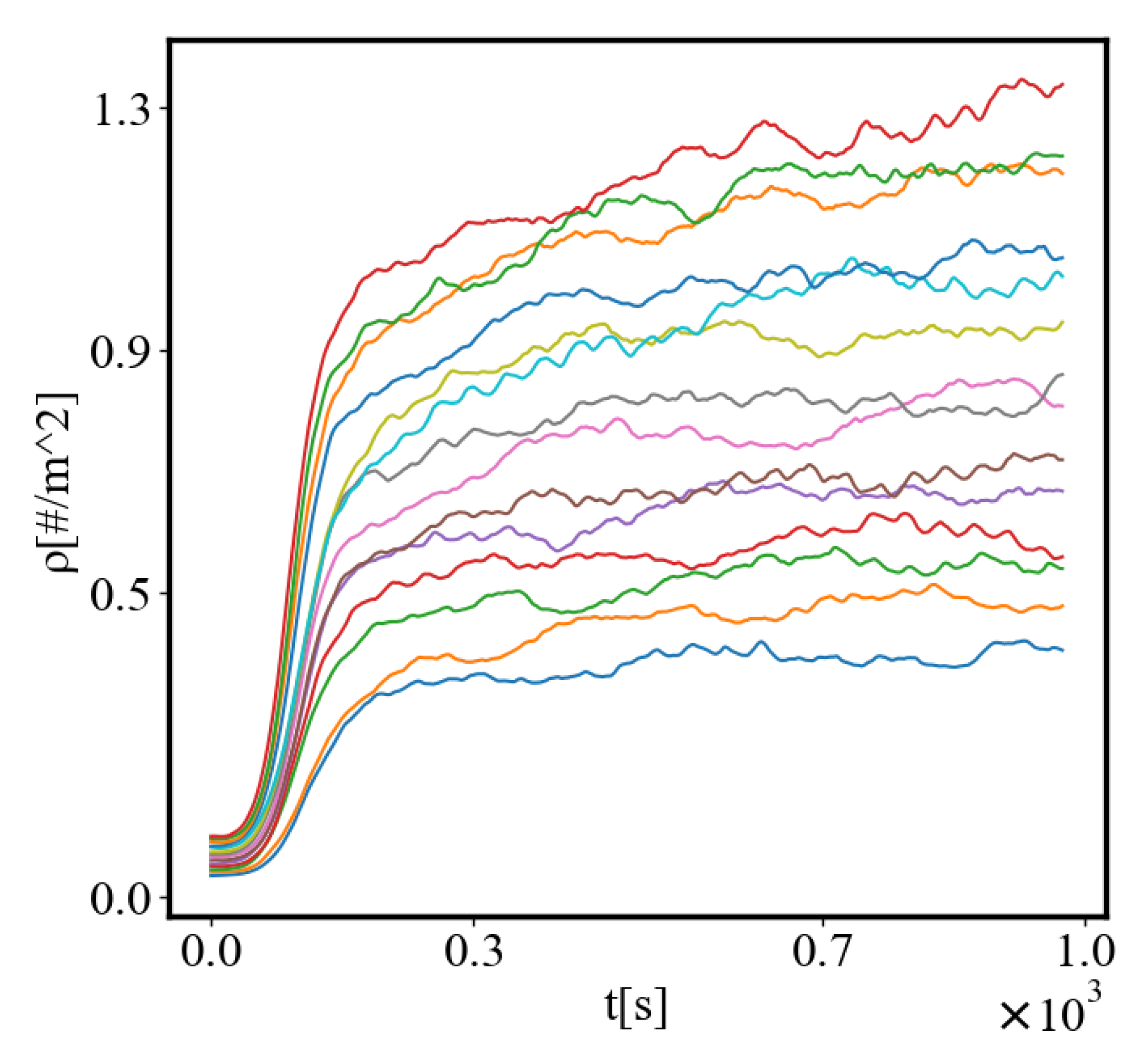

5.10. Density

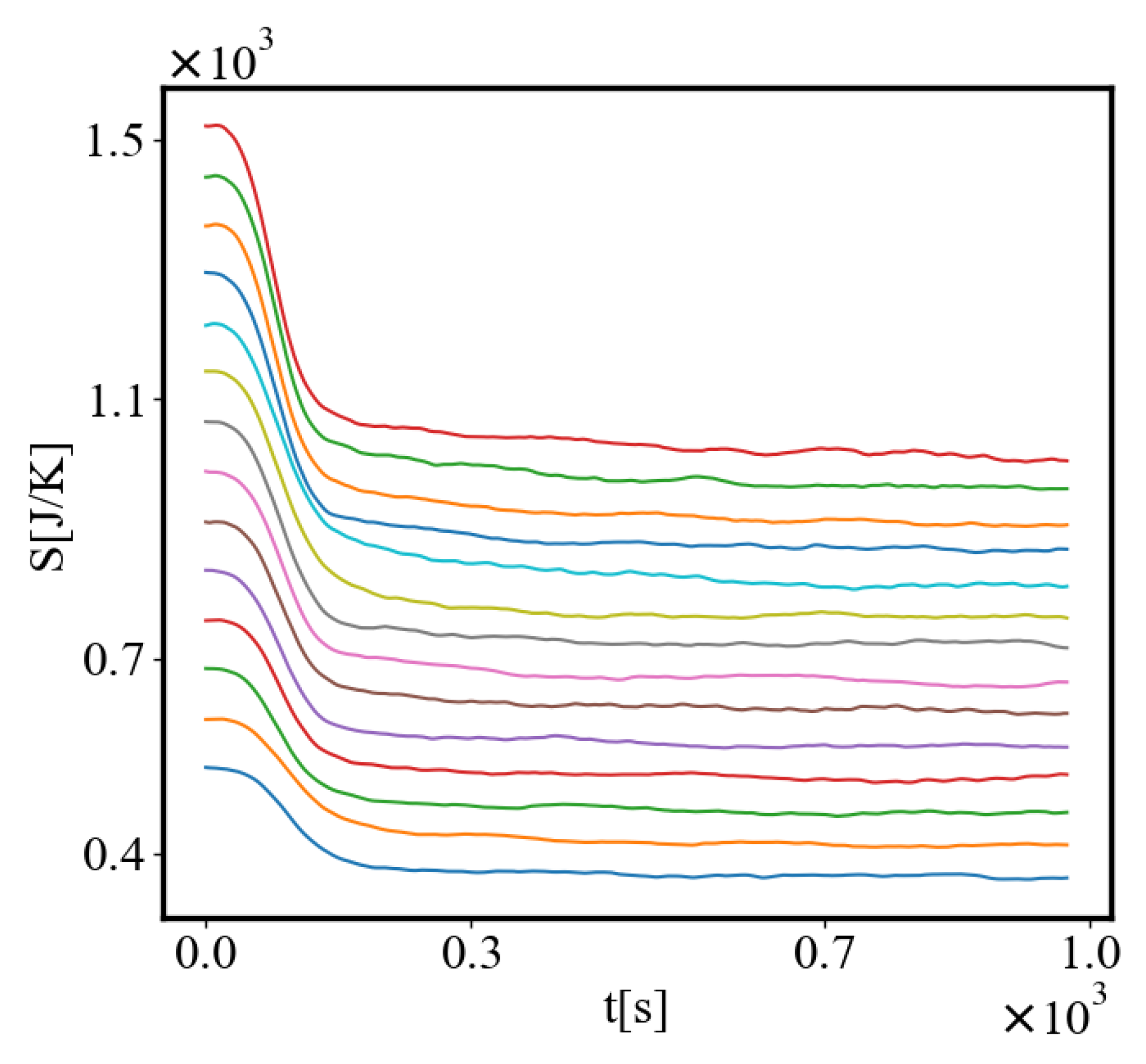

5.11. Entropy

5.12. Unit Entropy

5.13. Simulation Parameters

5.14. Simulation Tests

5.14.1. World Size

5.14.2. Estimated Path Area

6. Results

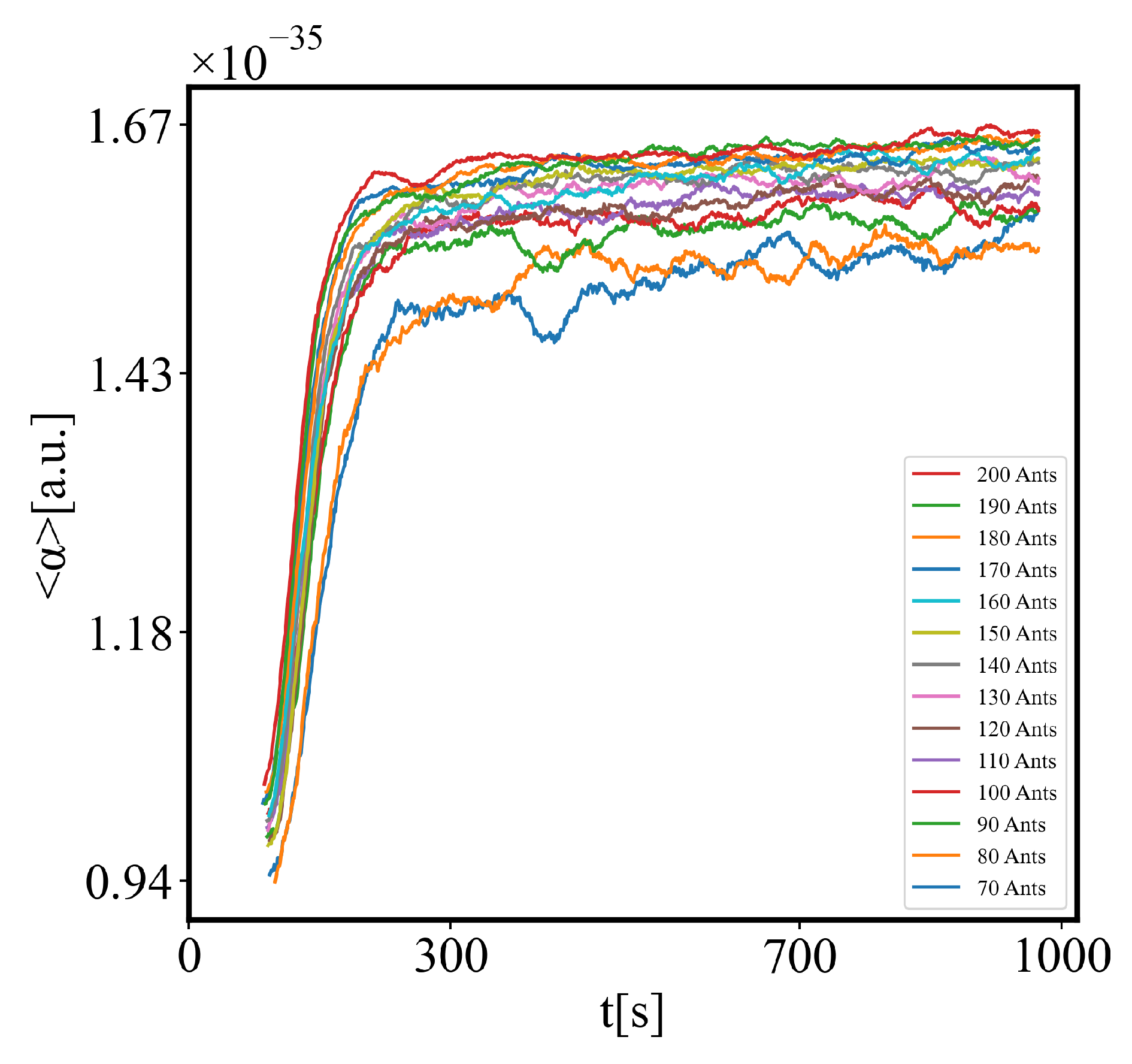

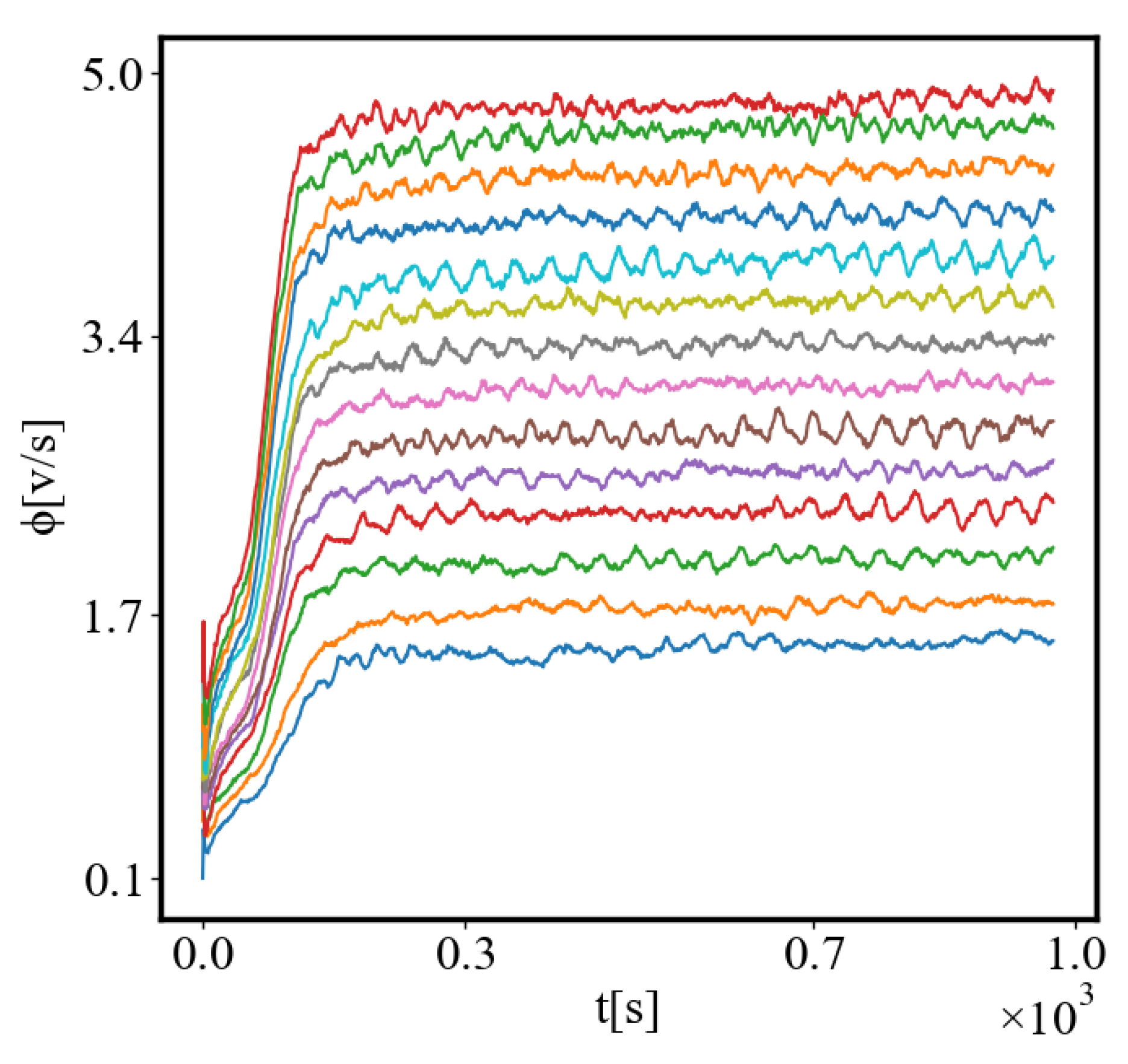

6.1. Time Graphs

6.1.1. a Note on the Rate of Self-Organization as a Function of the Size of the System

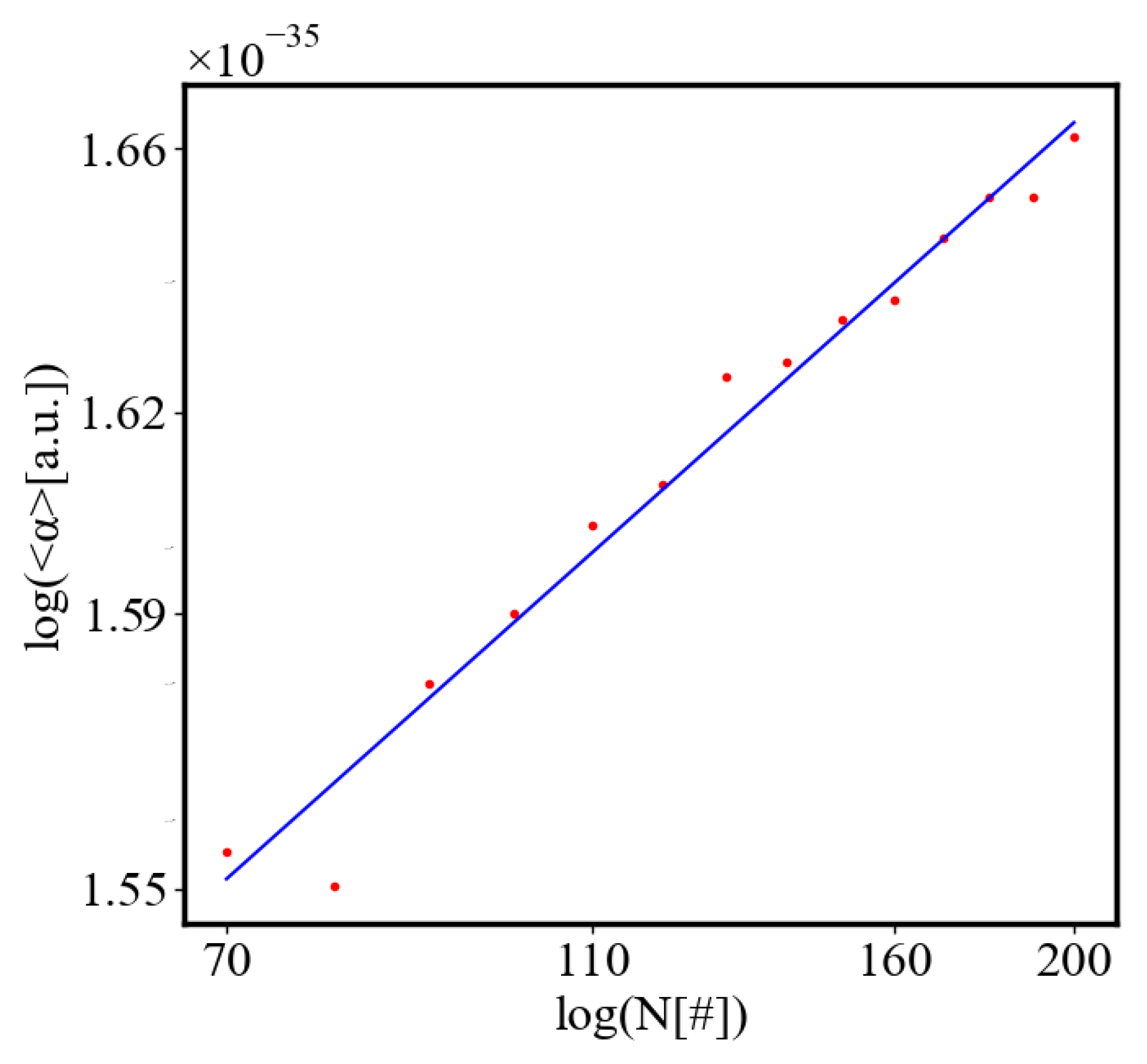

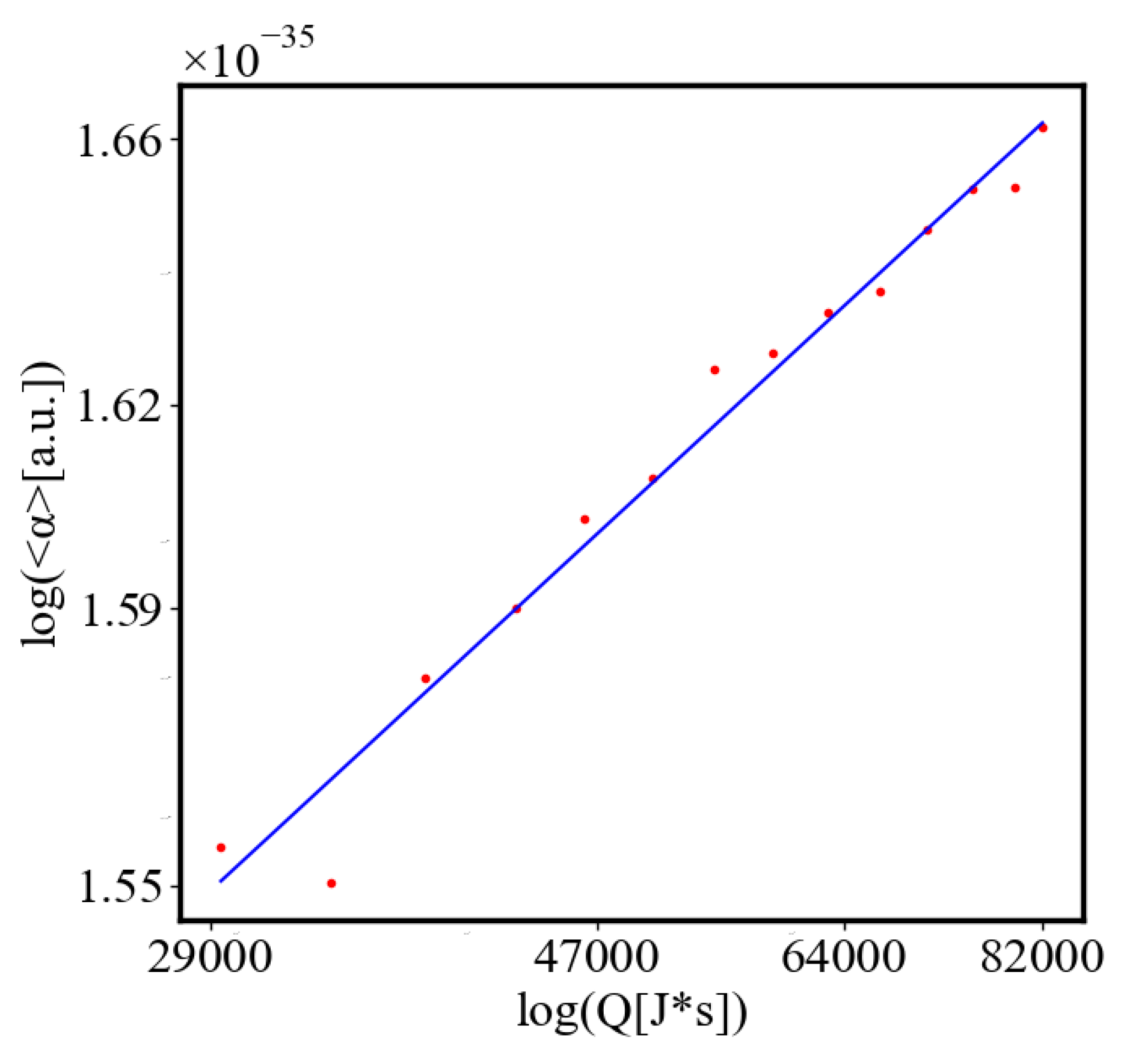

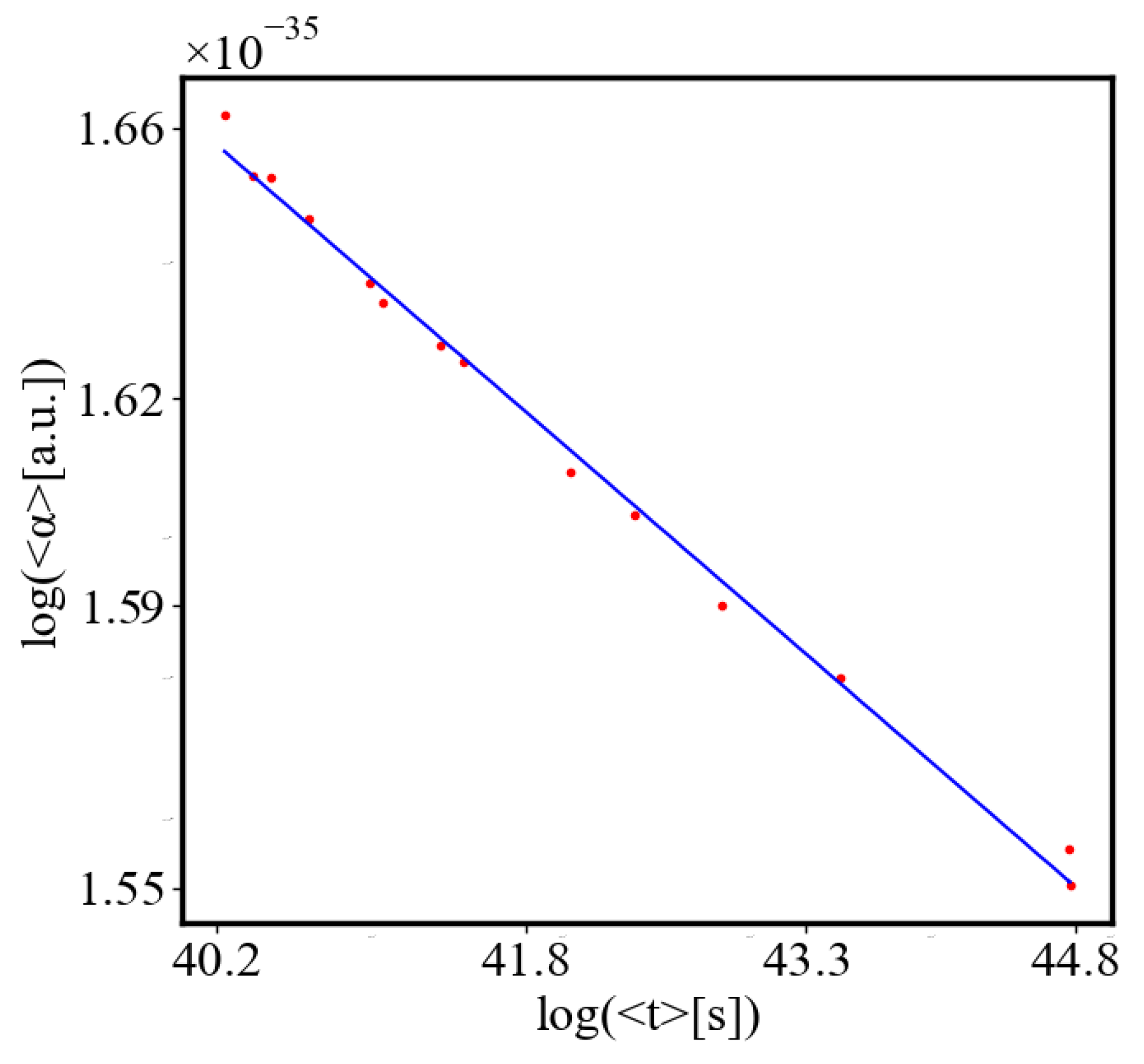

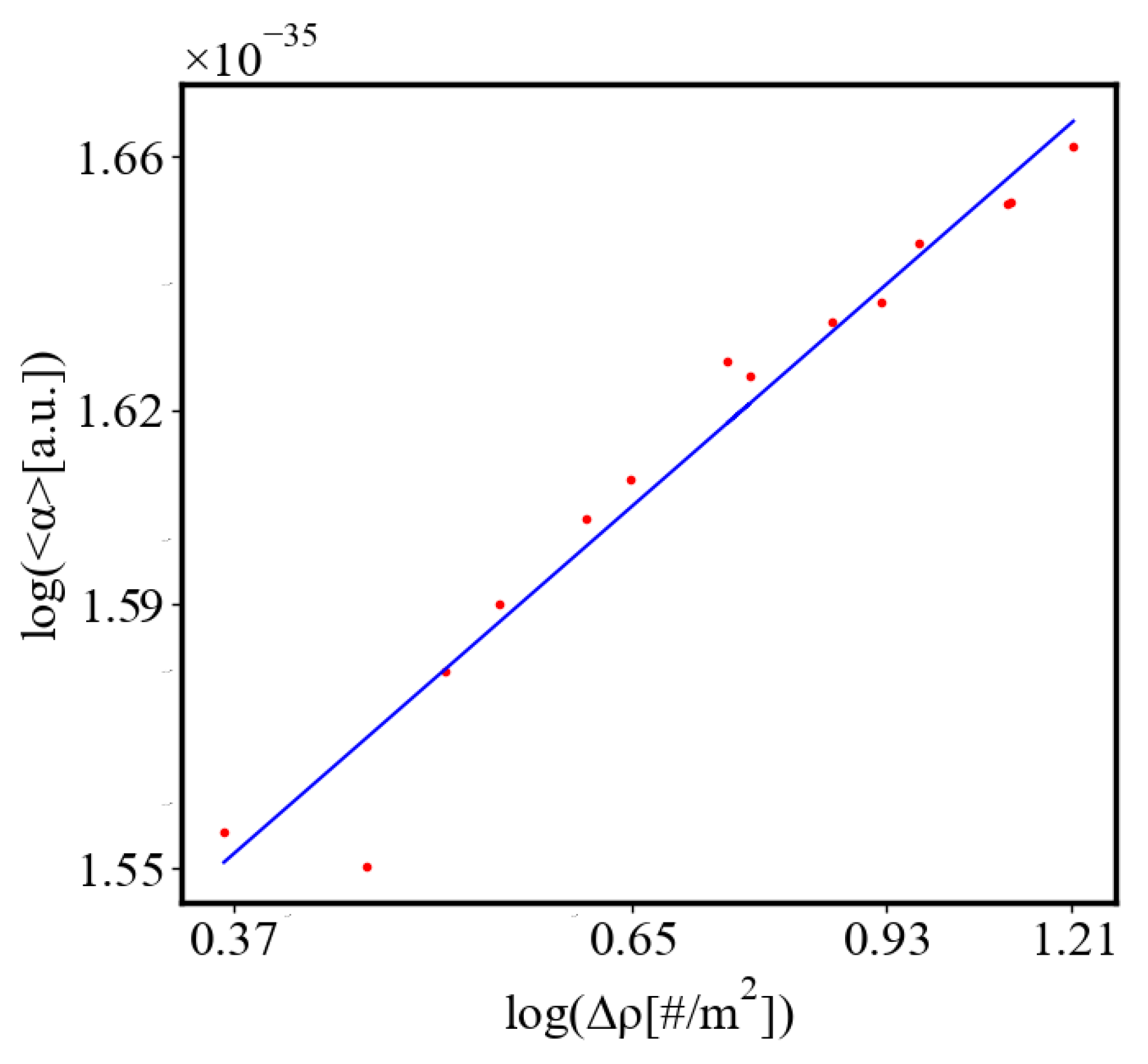

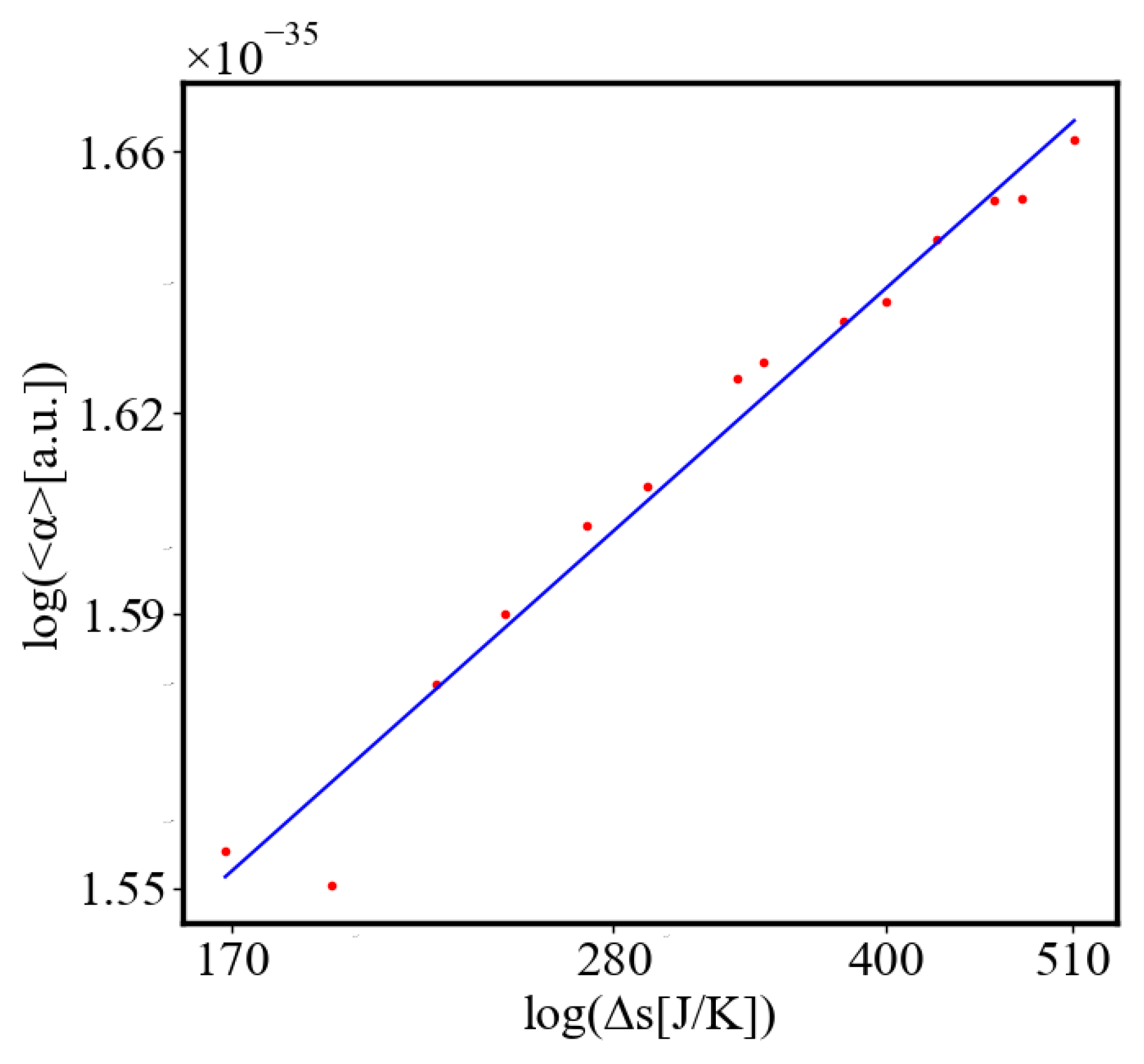

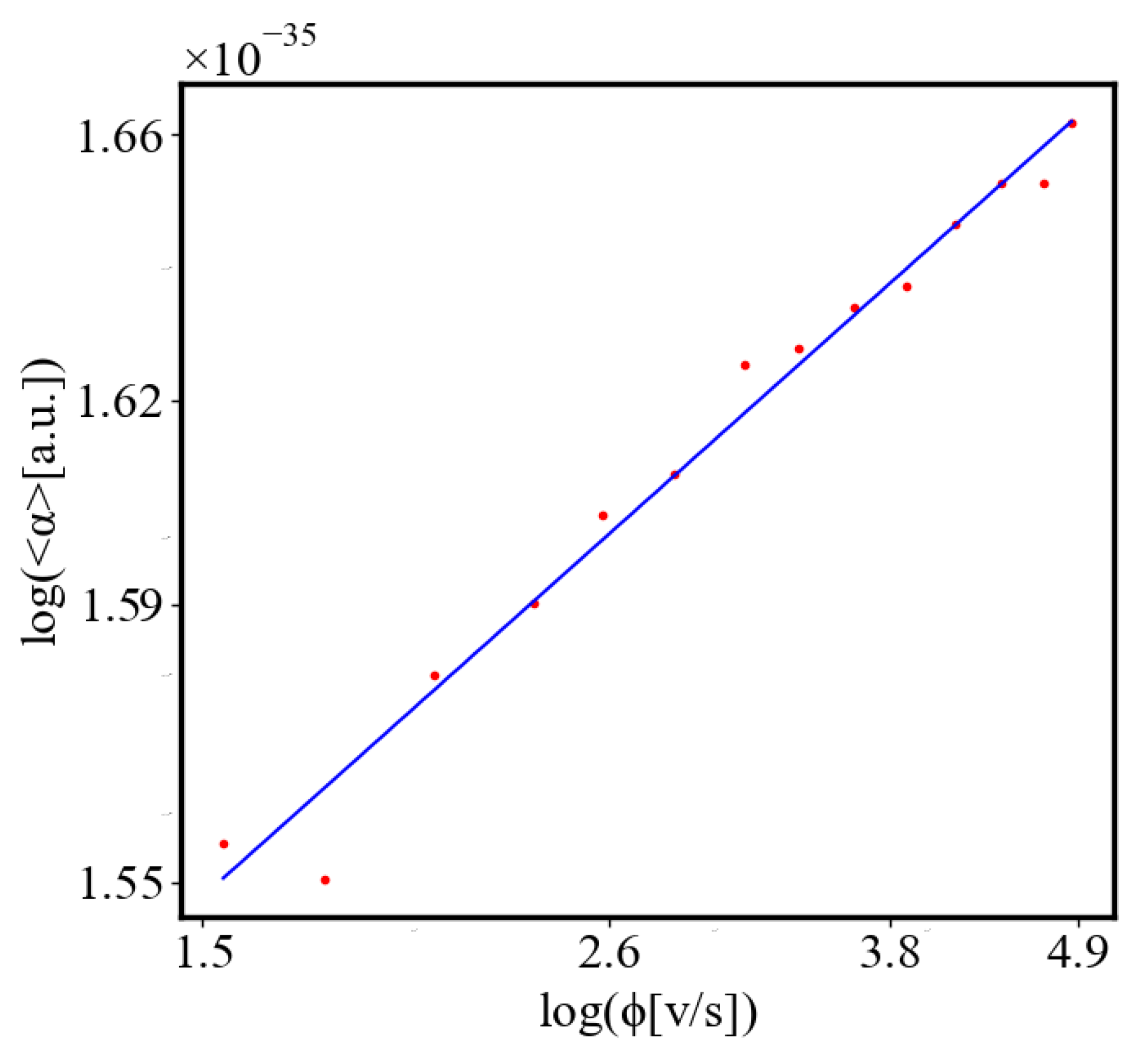

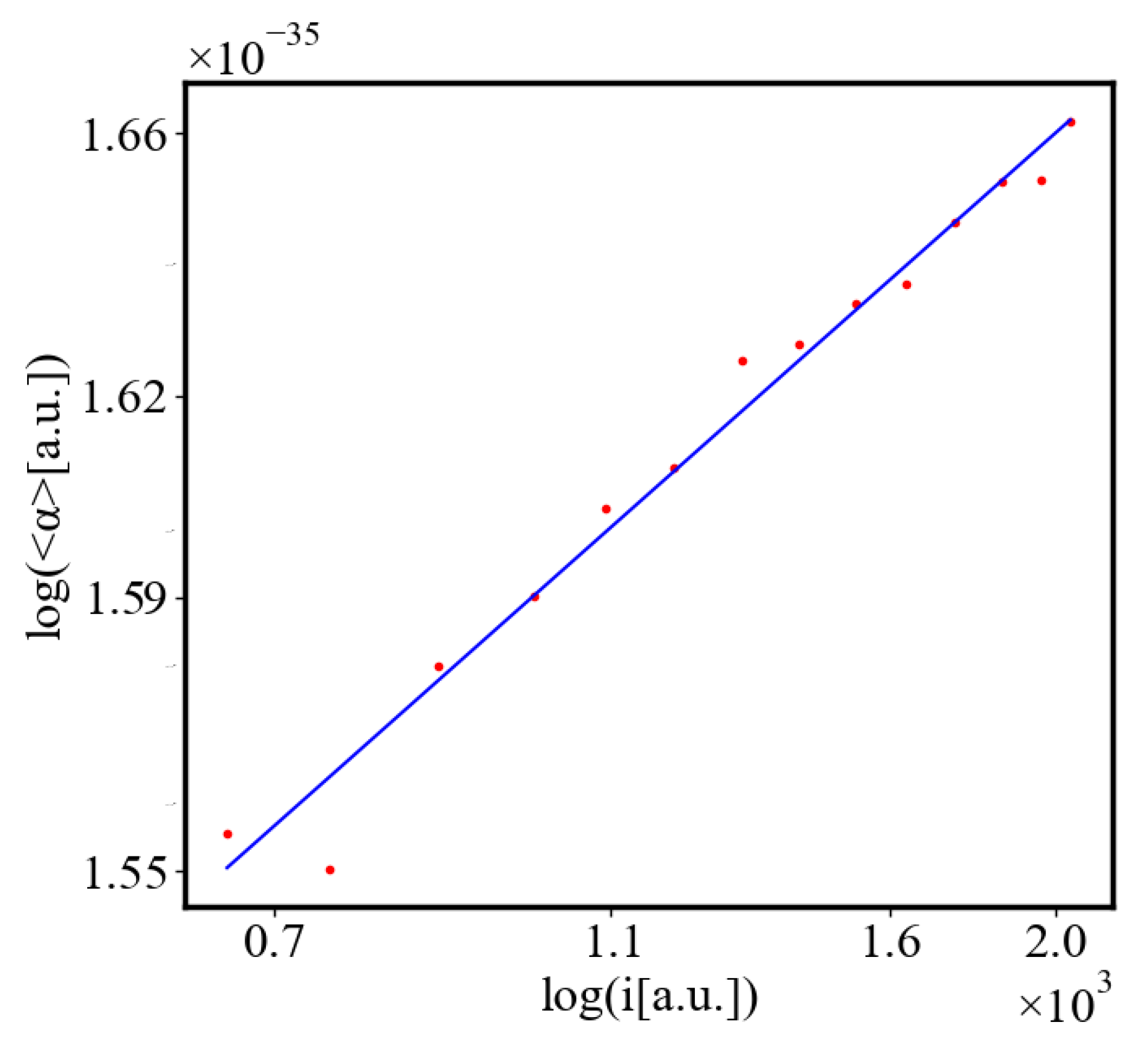

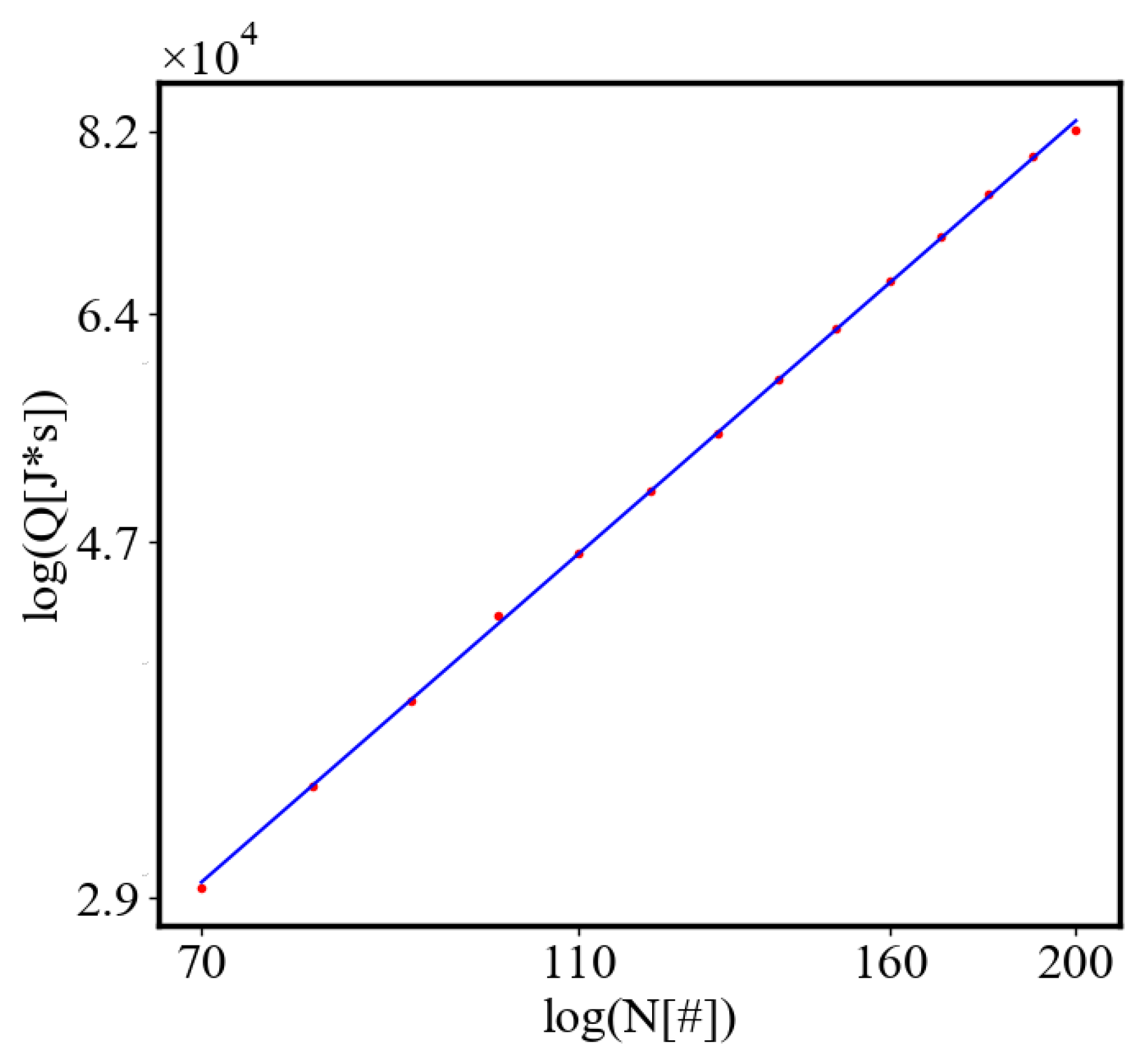

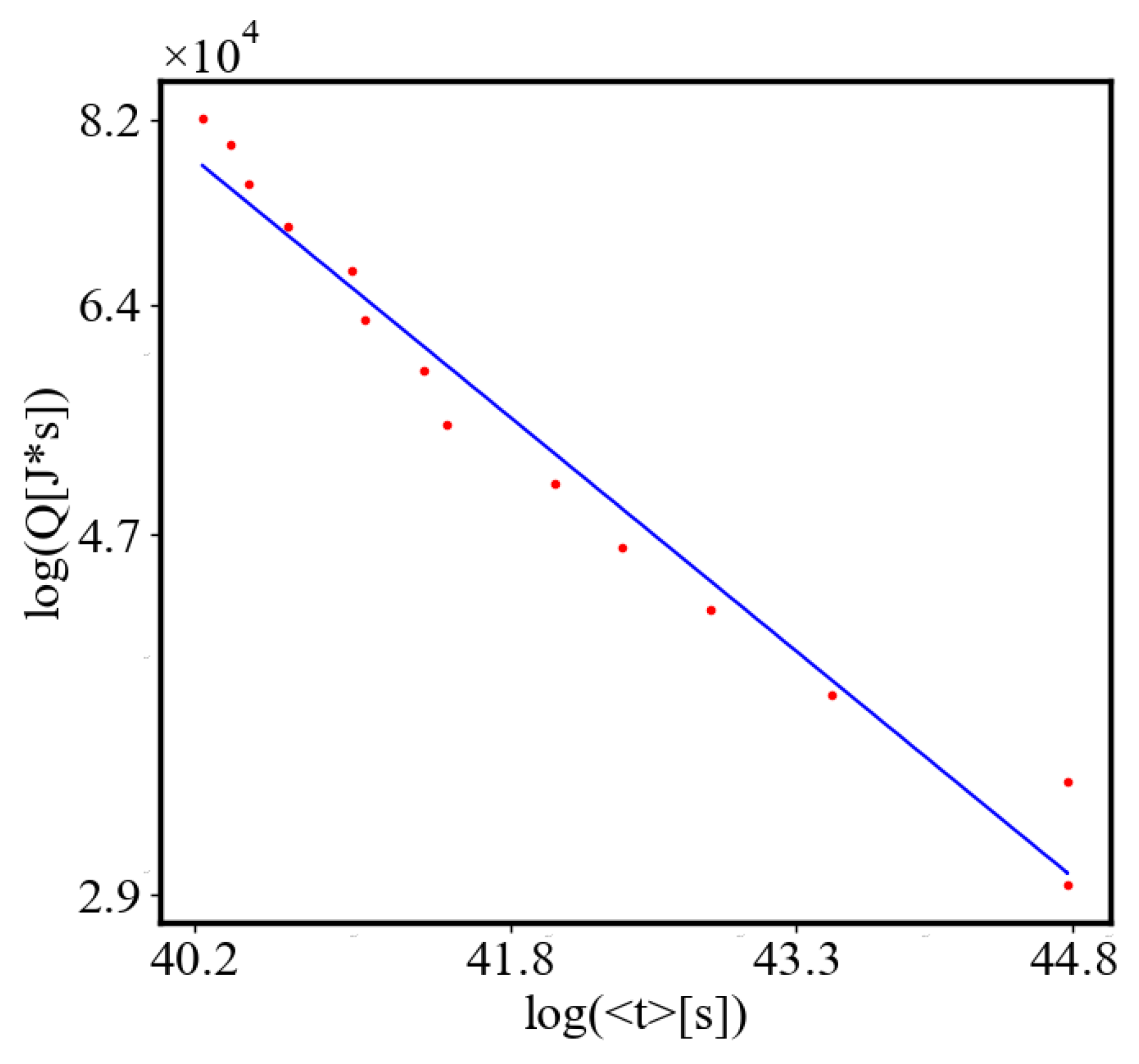

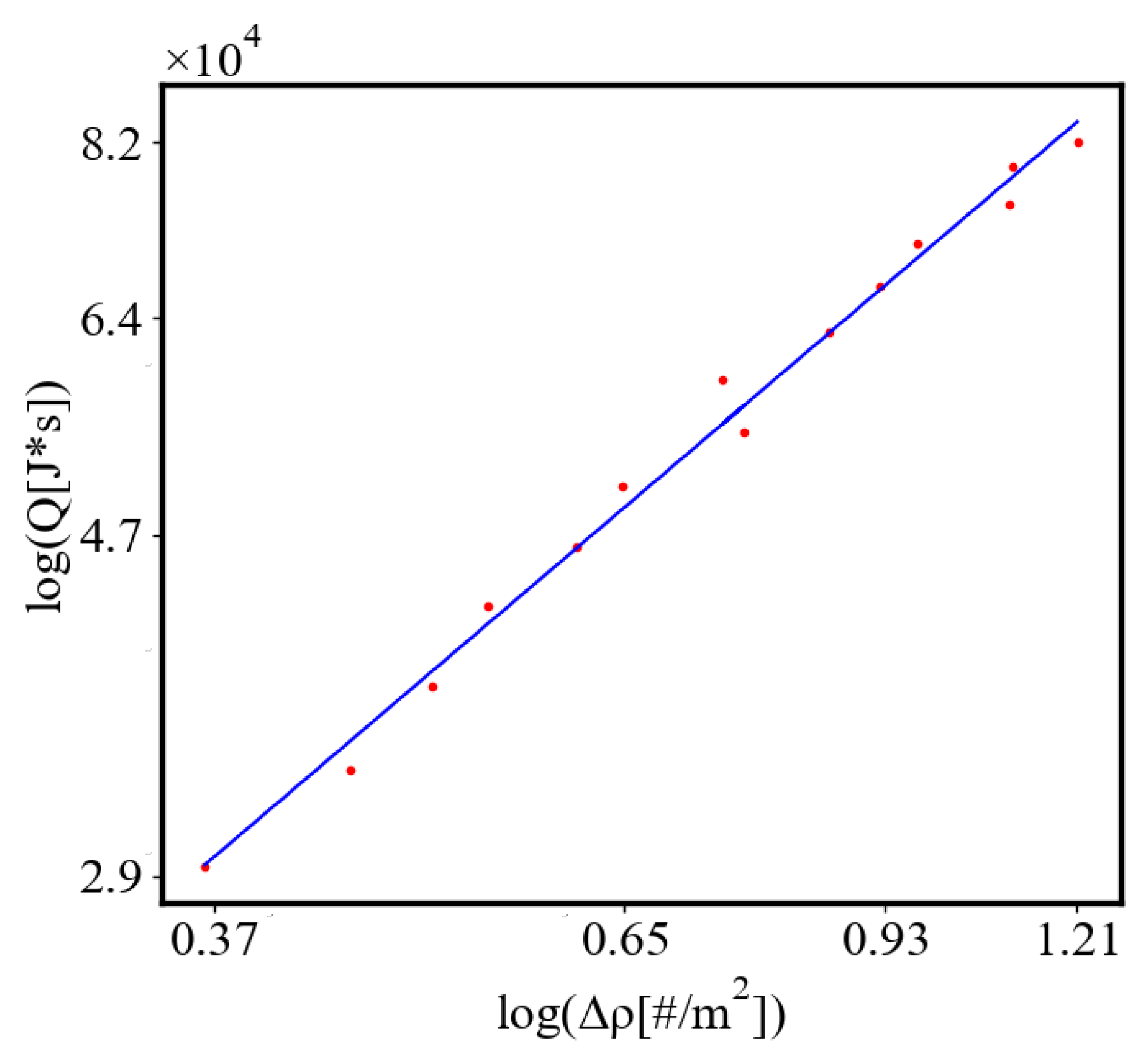

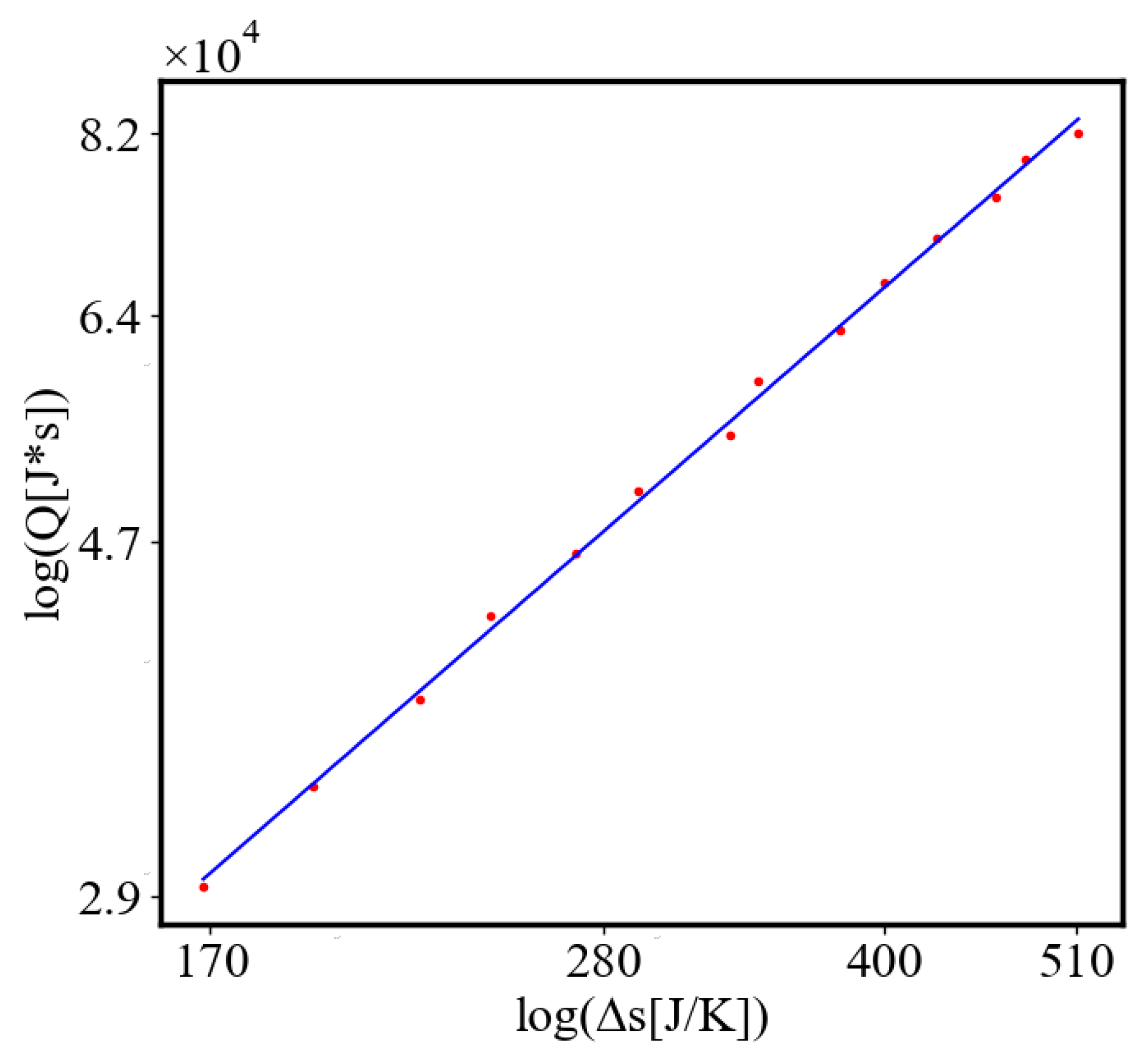

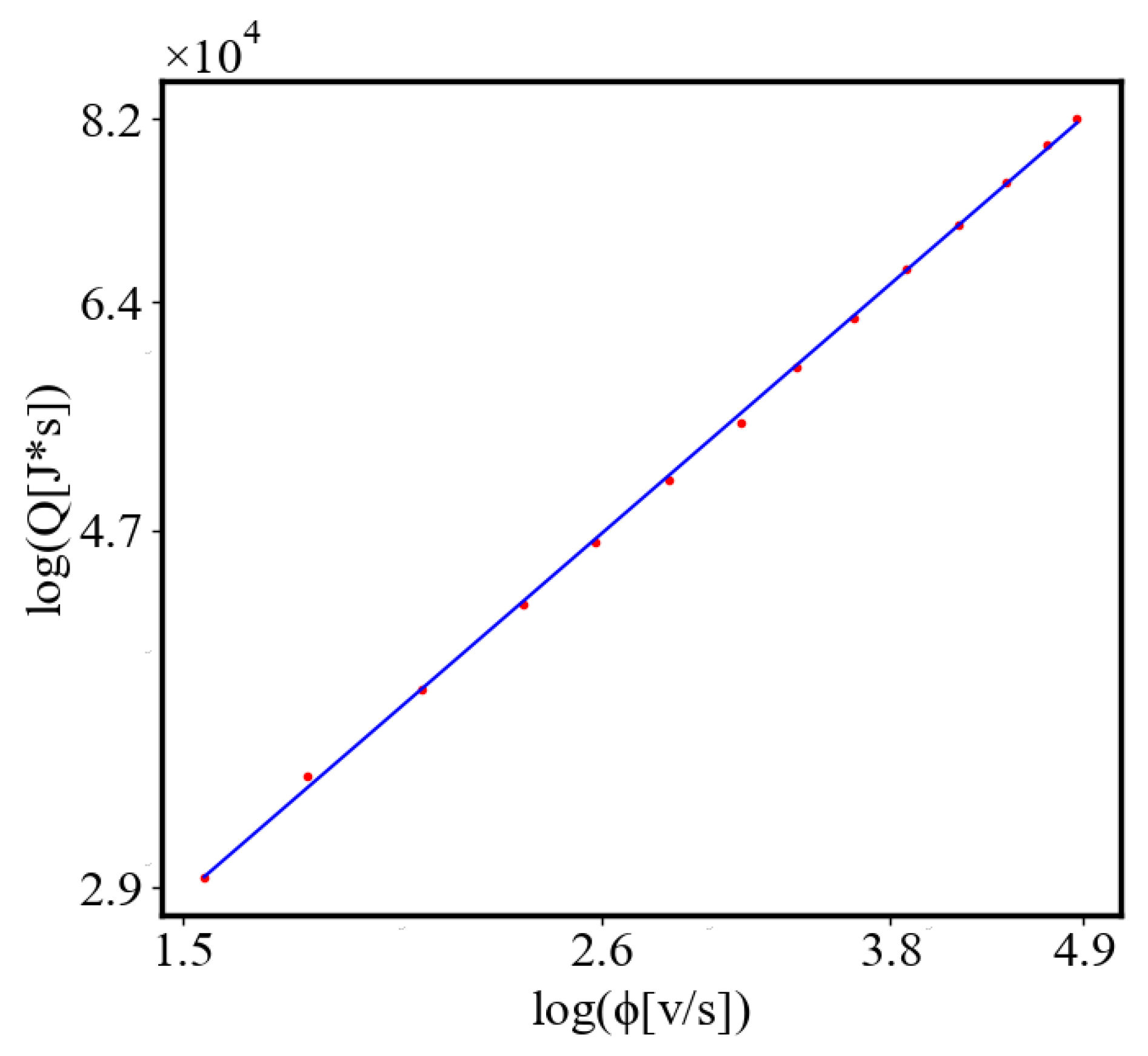

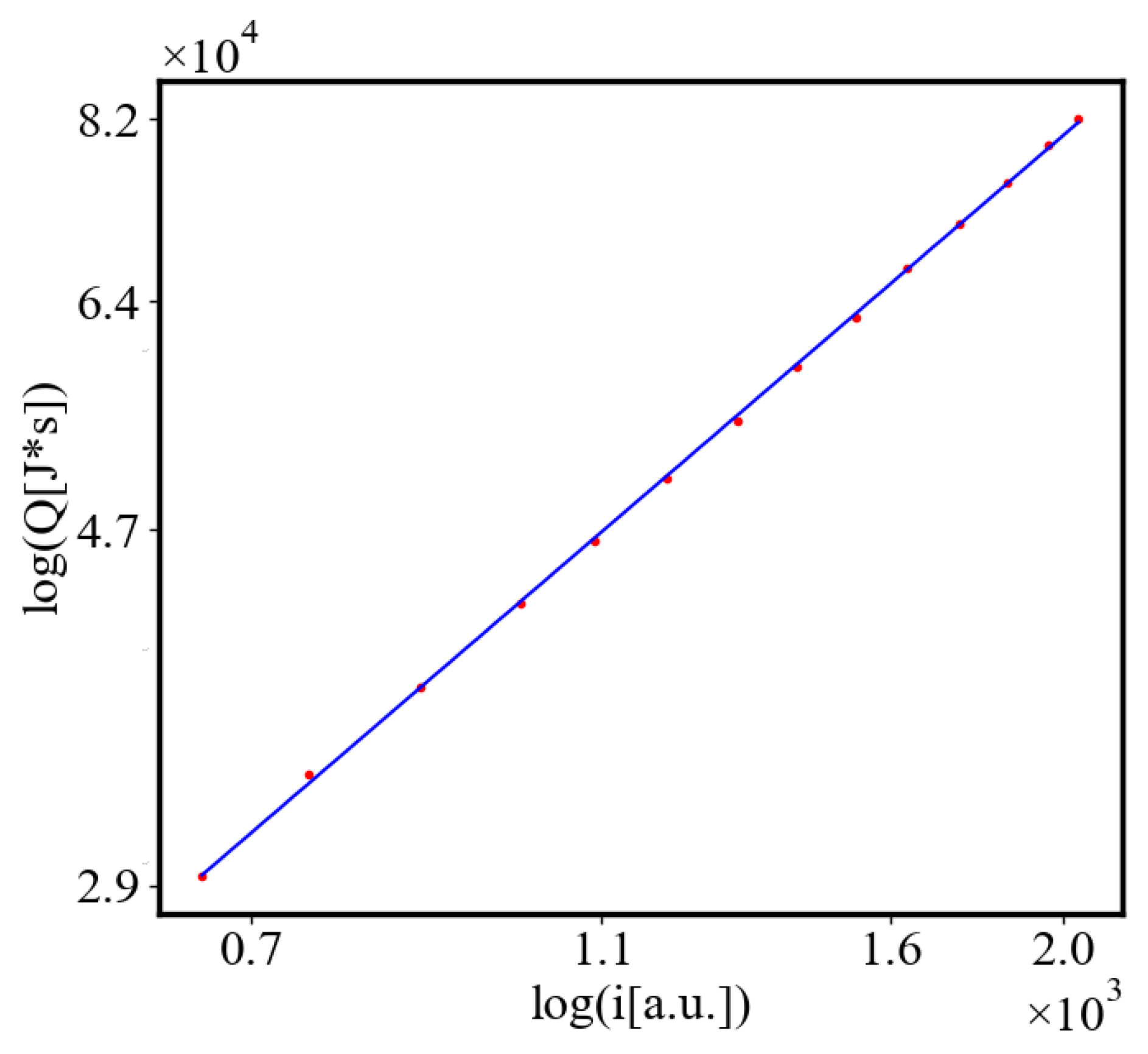

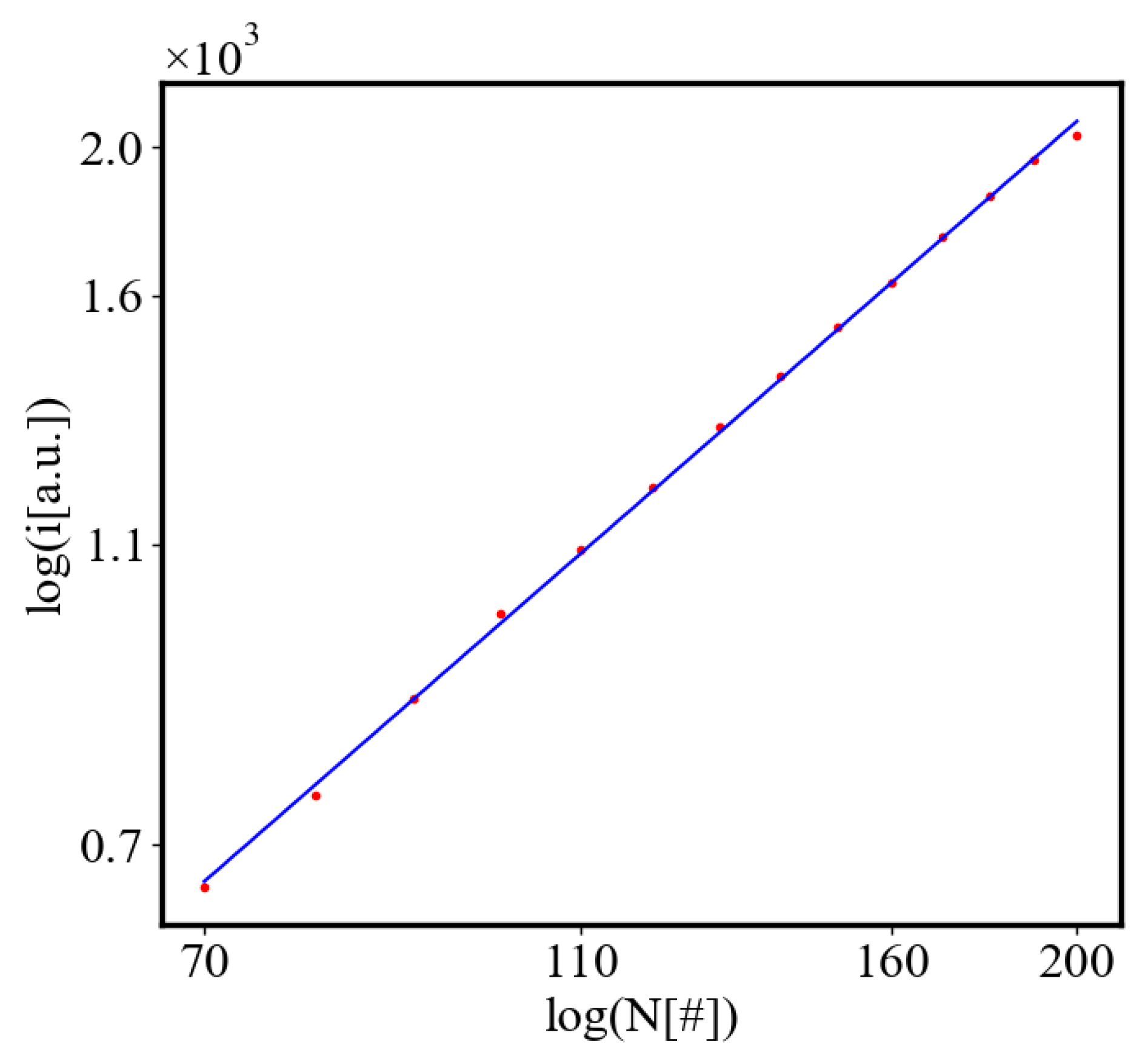

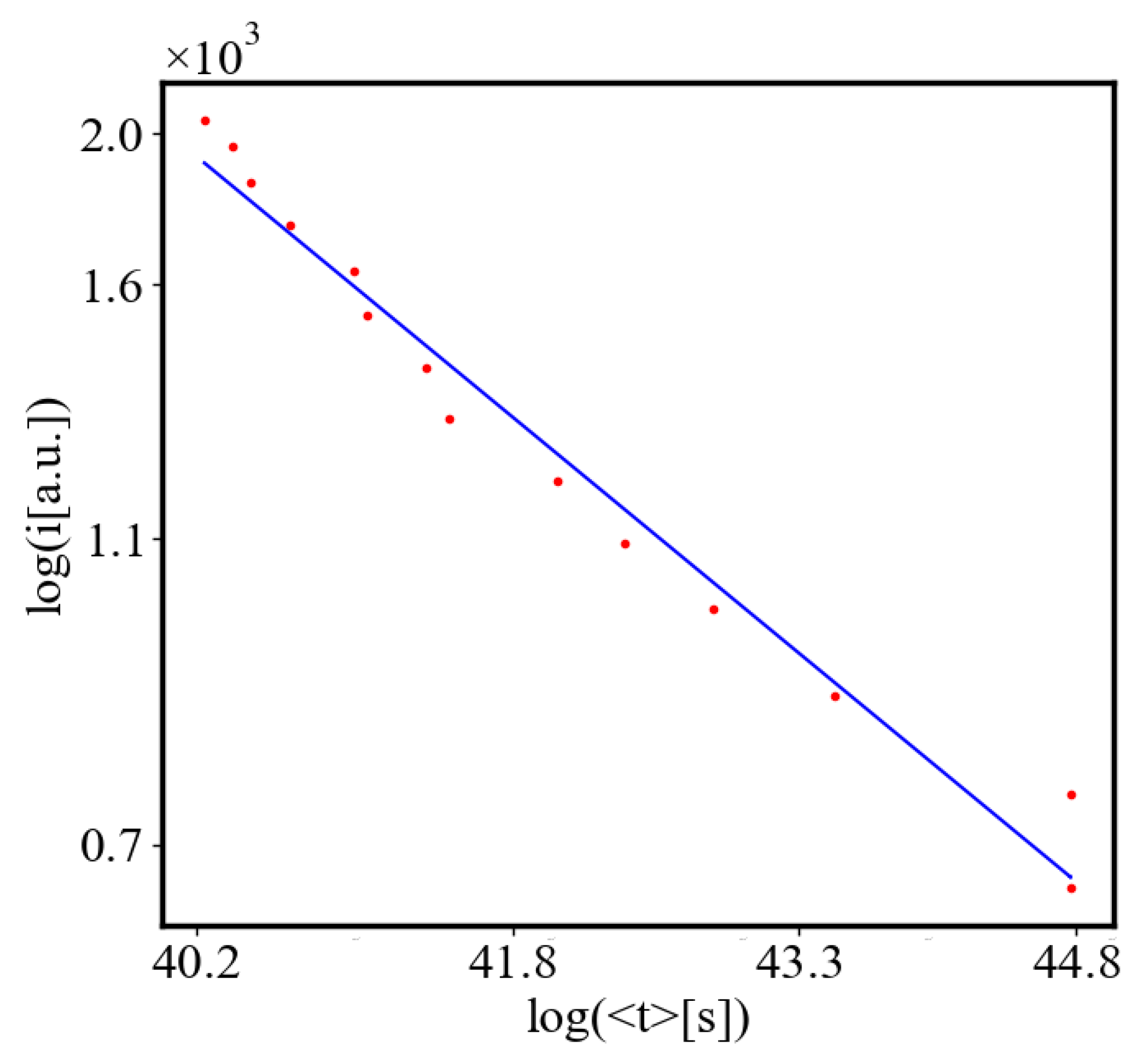

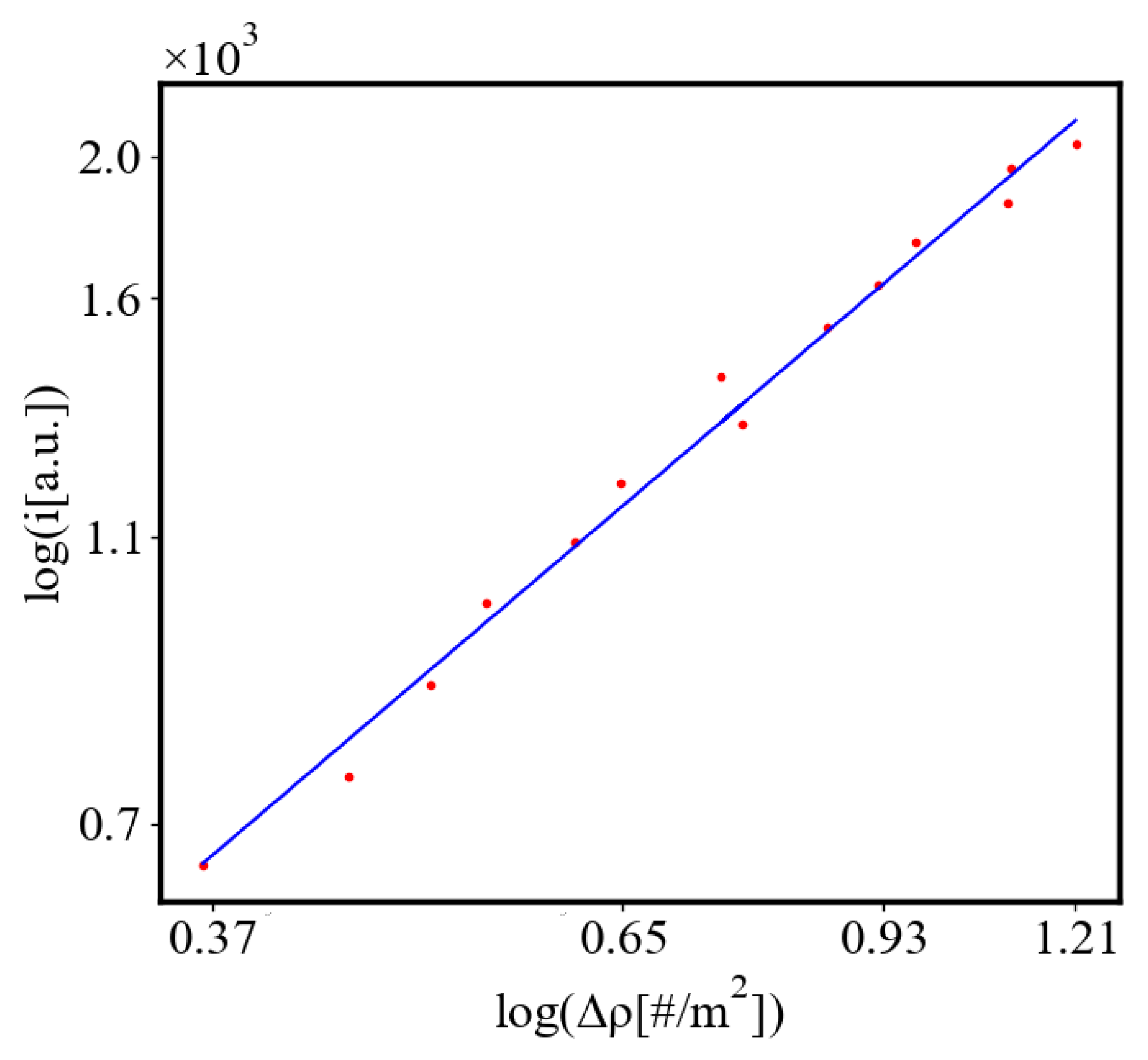

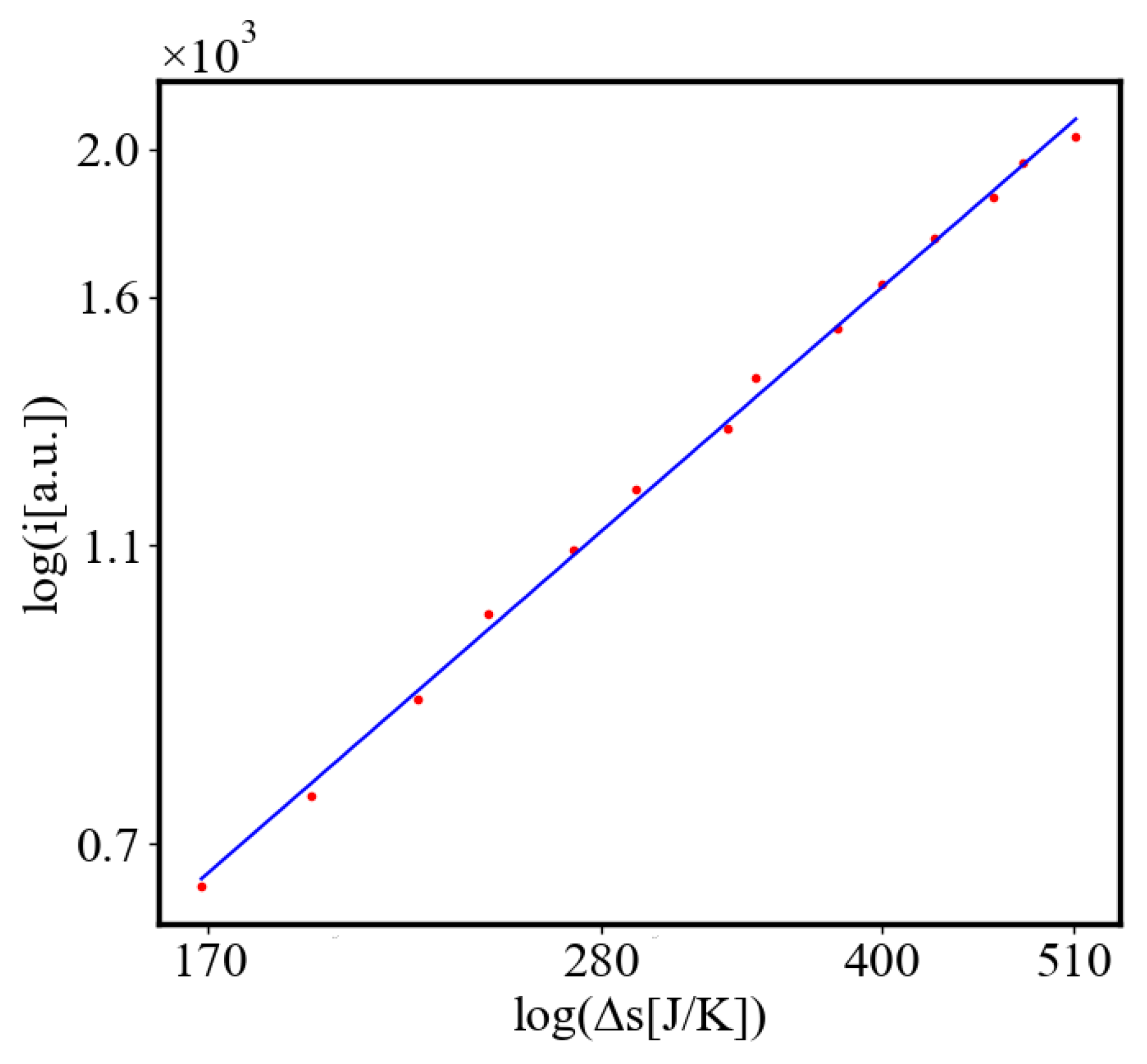

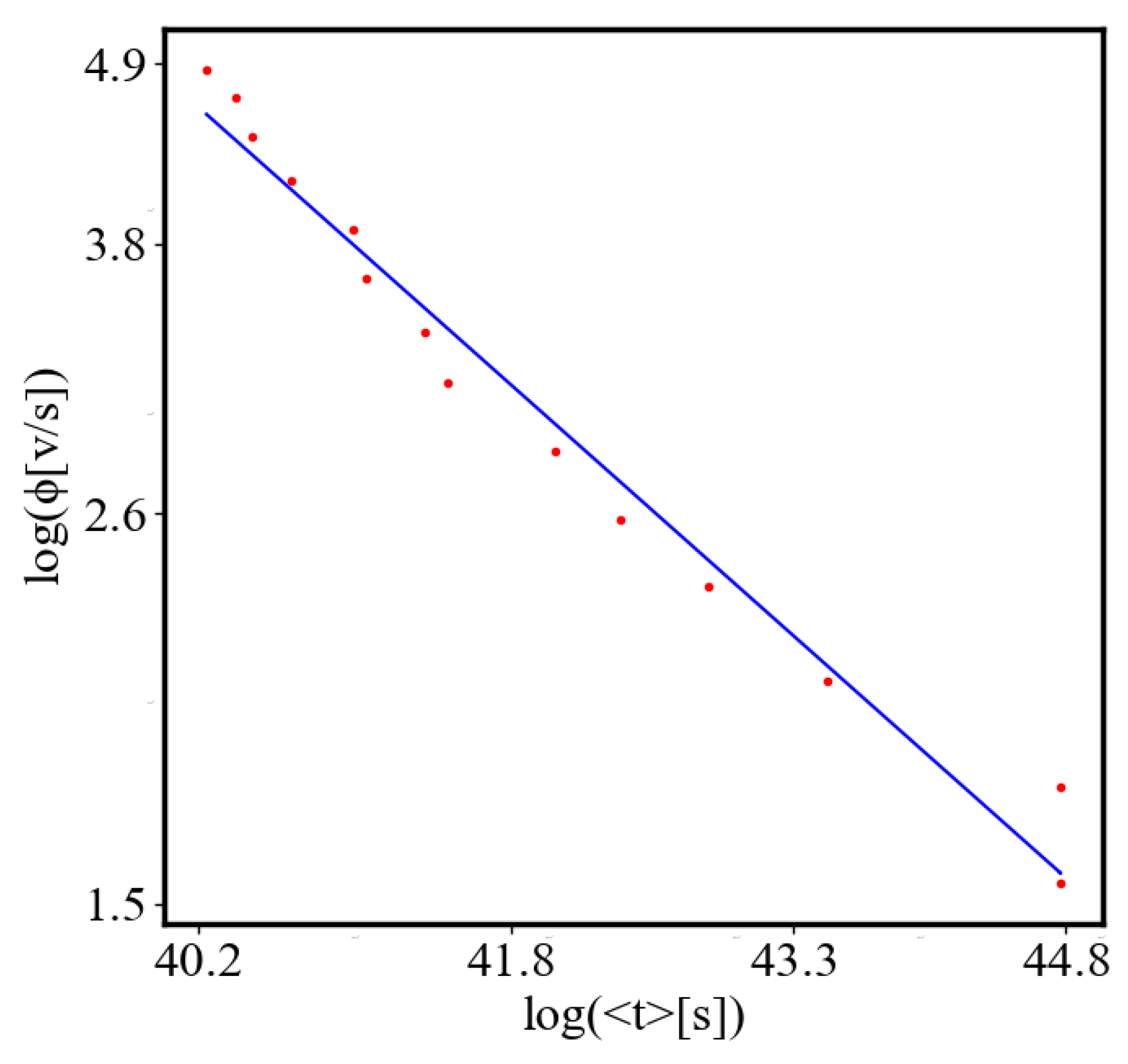

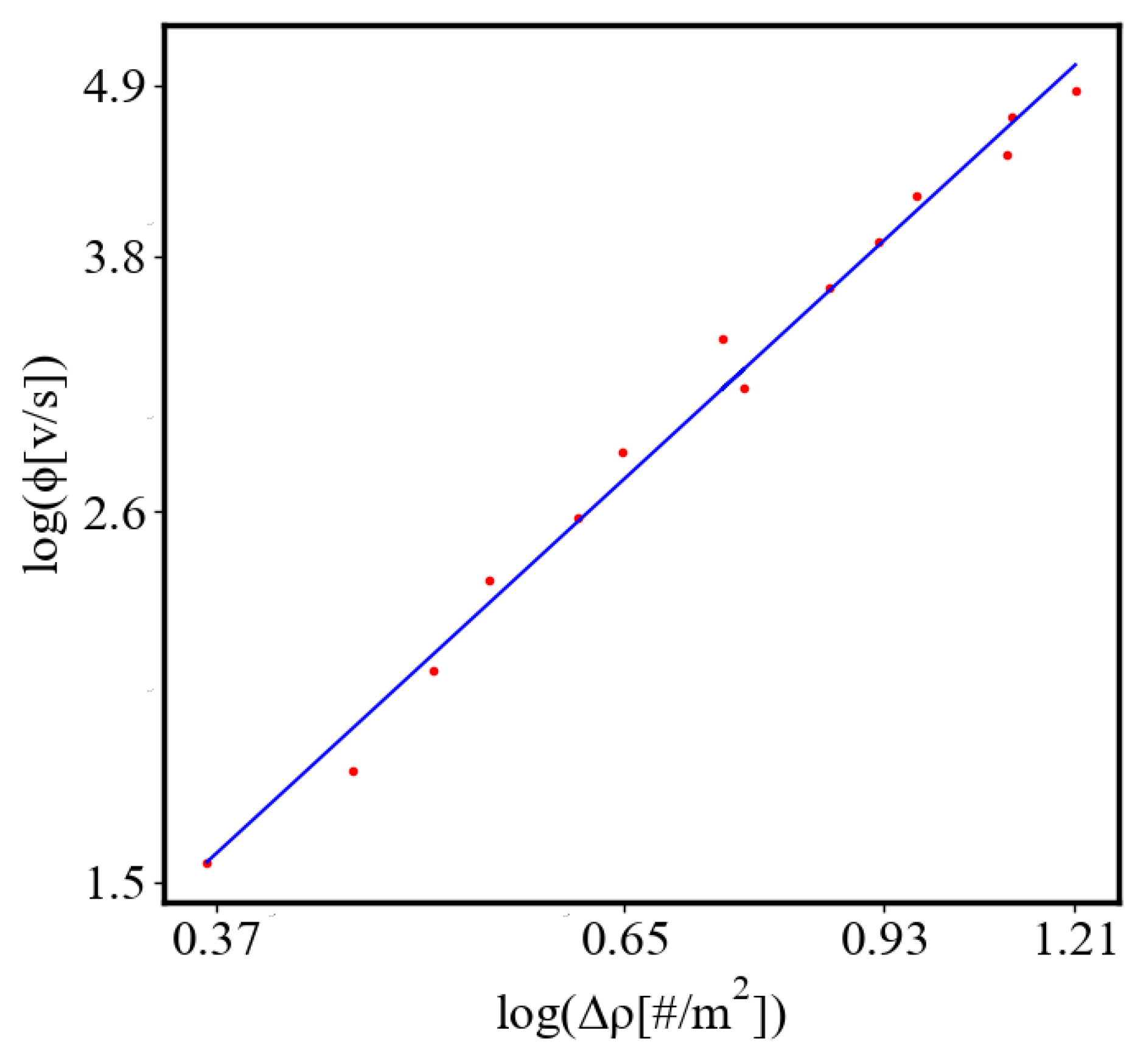

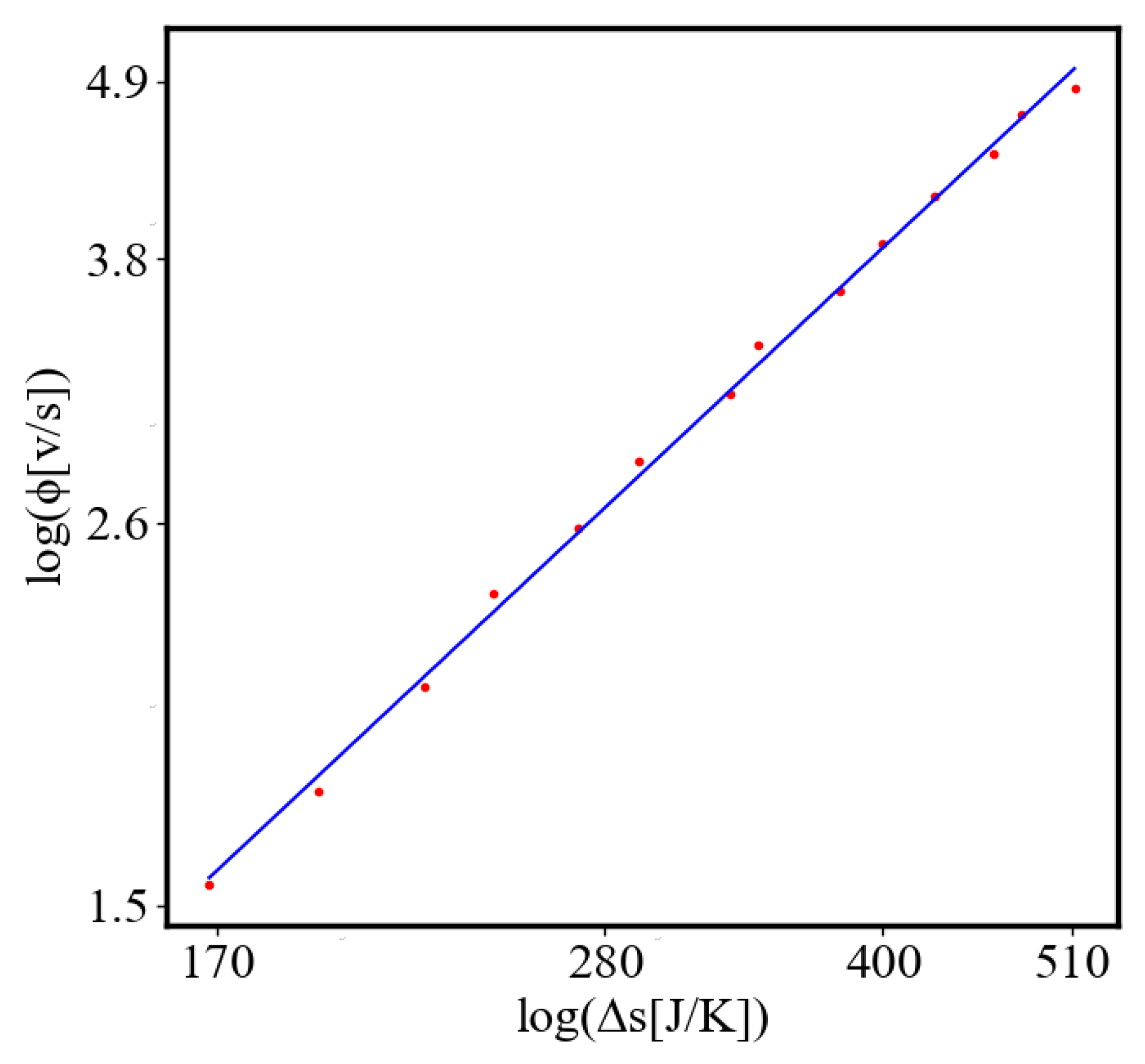

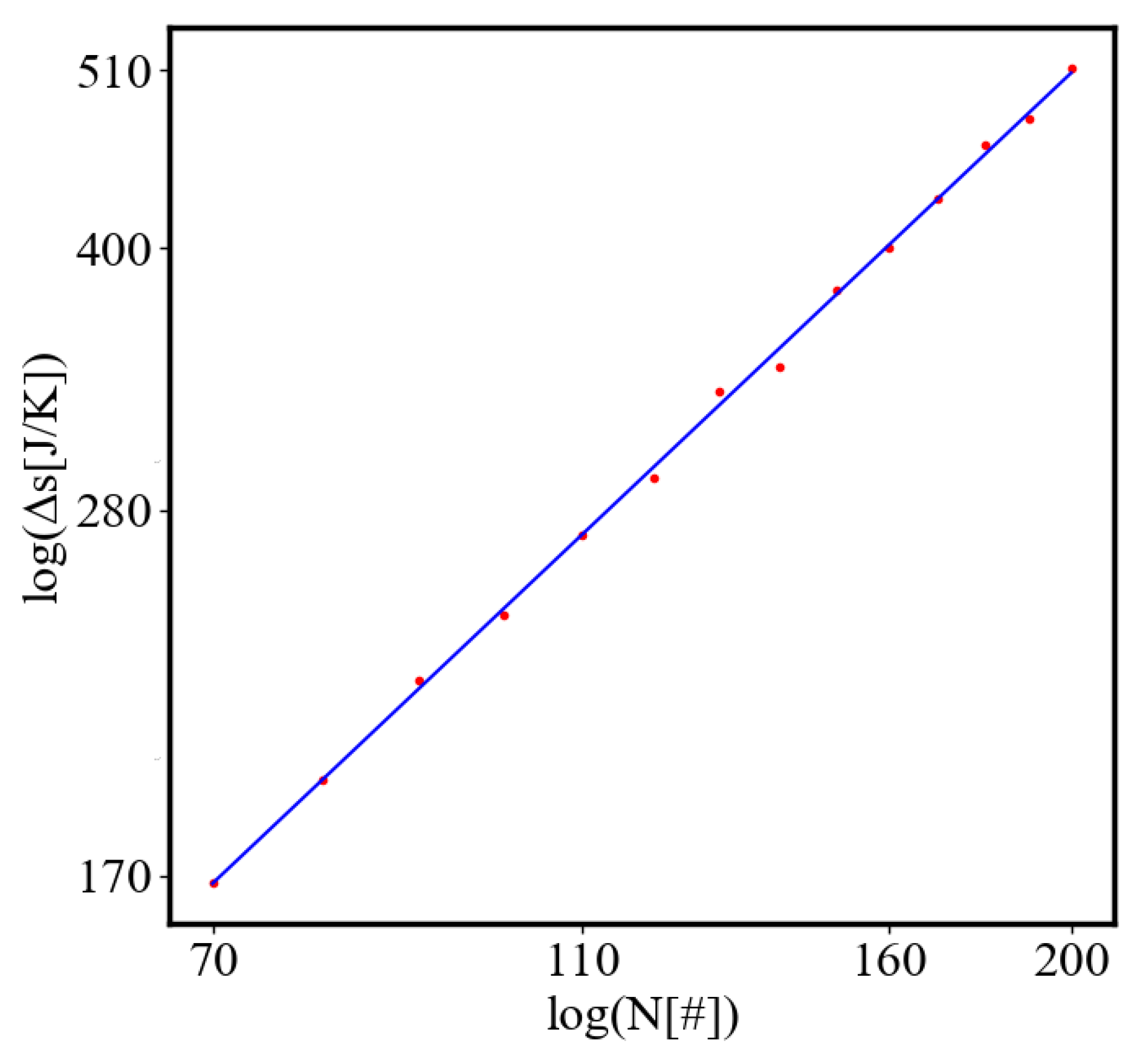

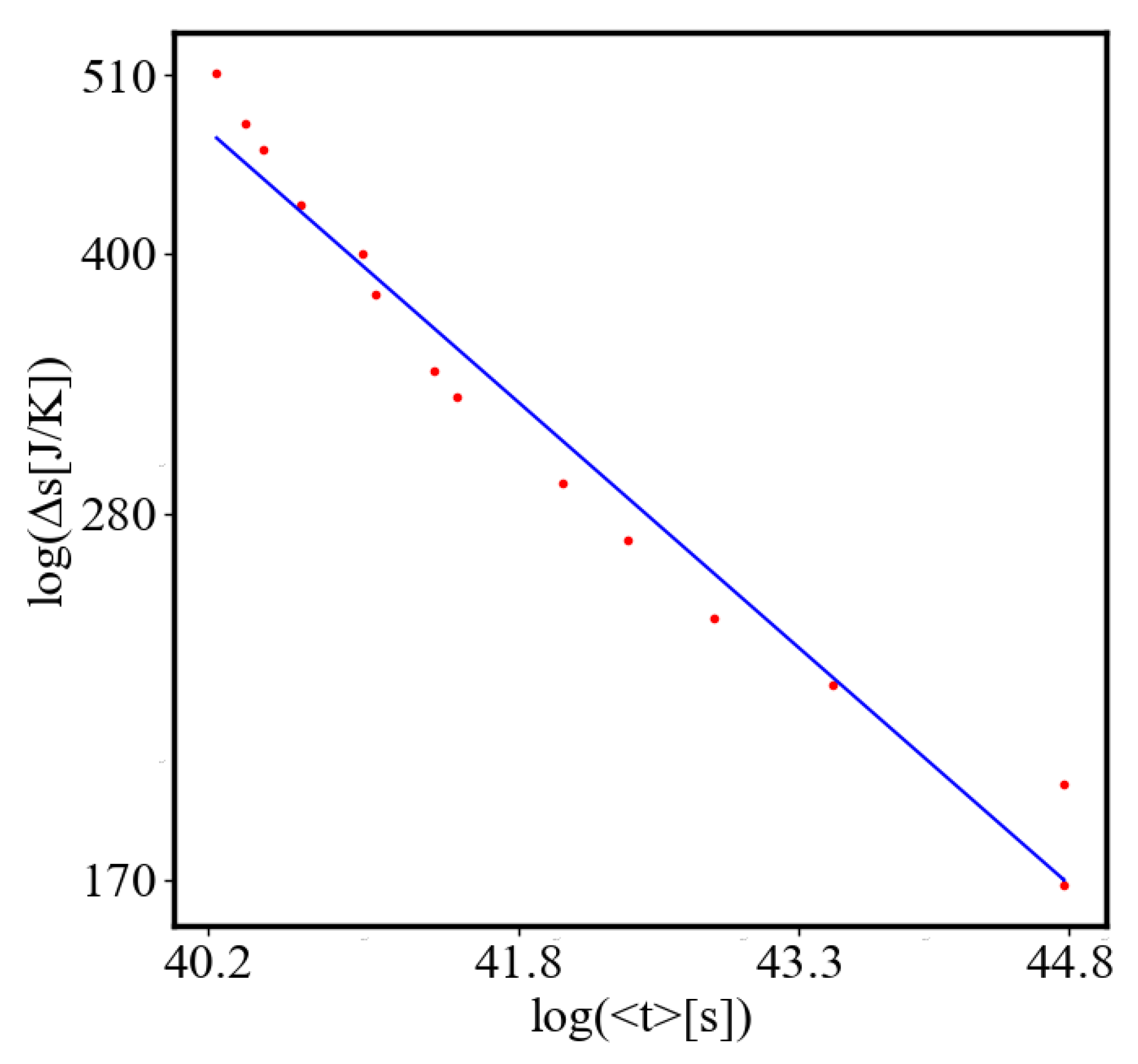

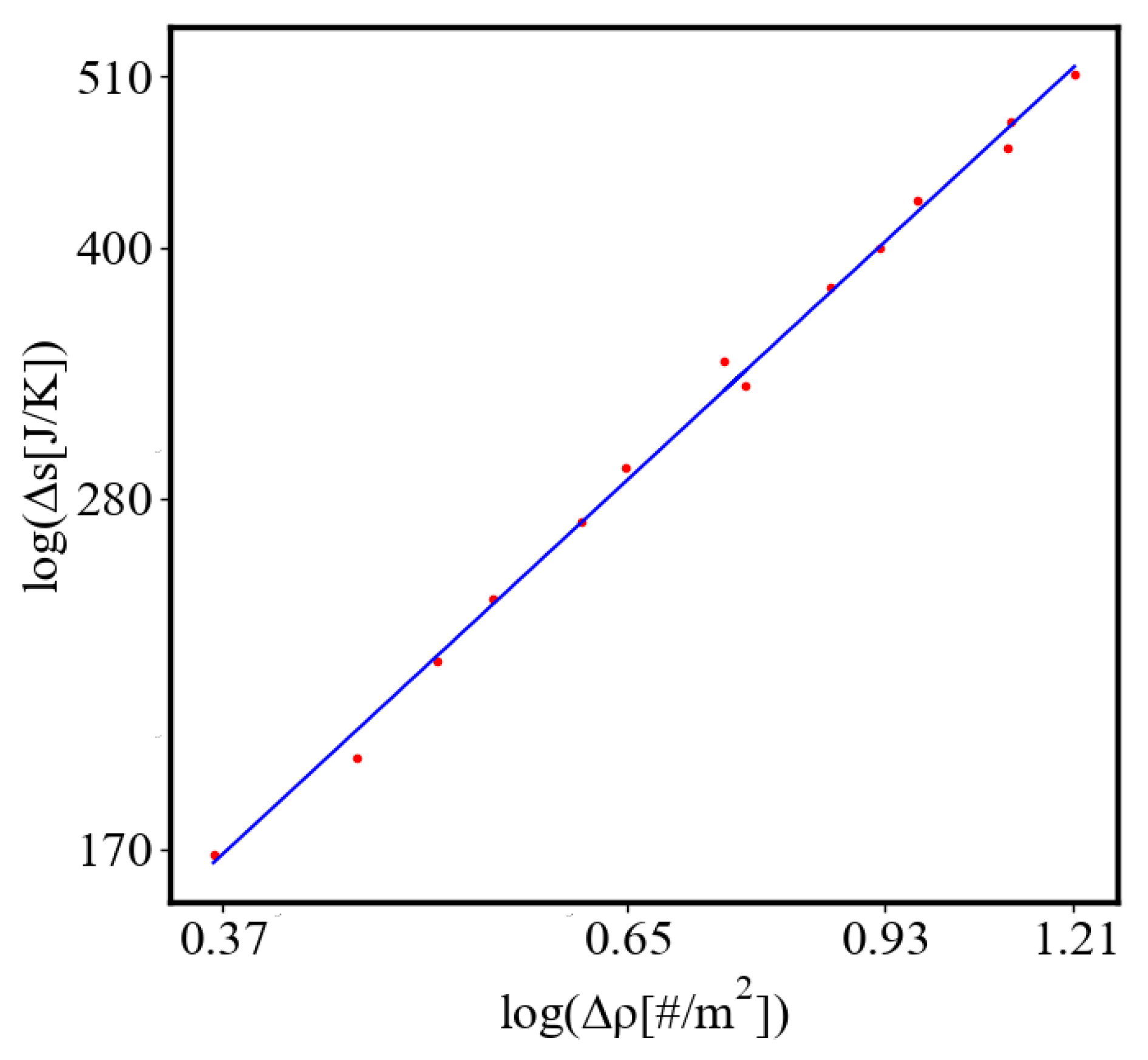

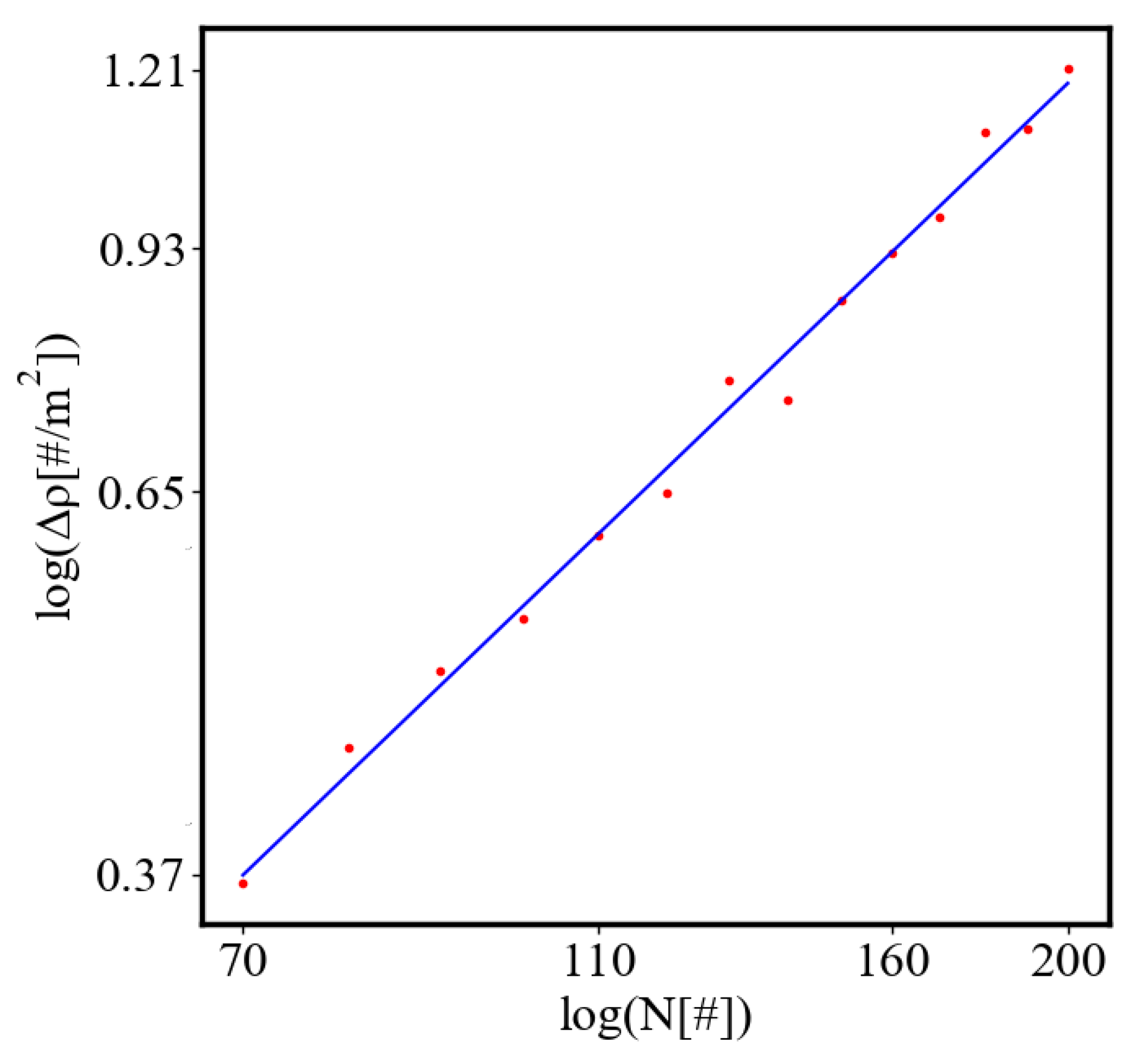

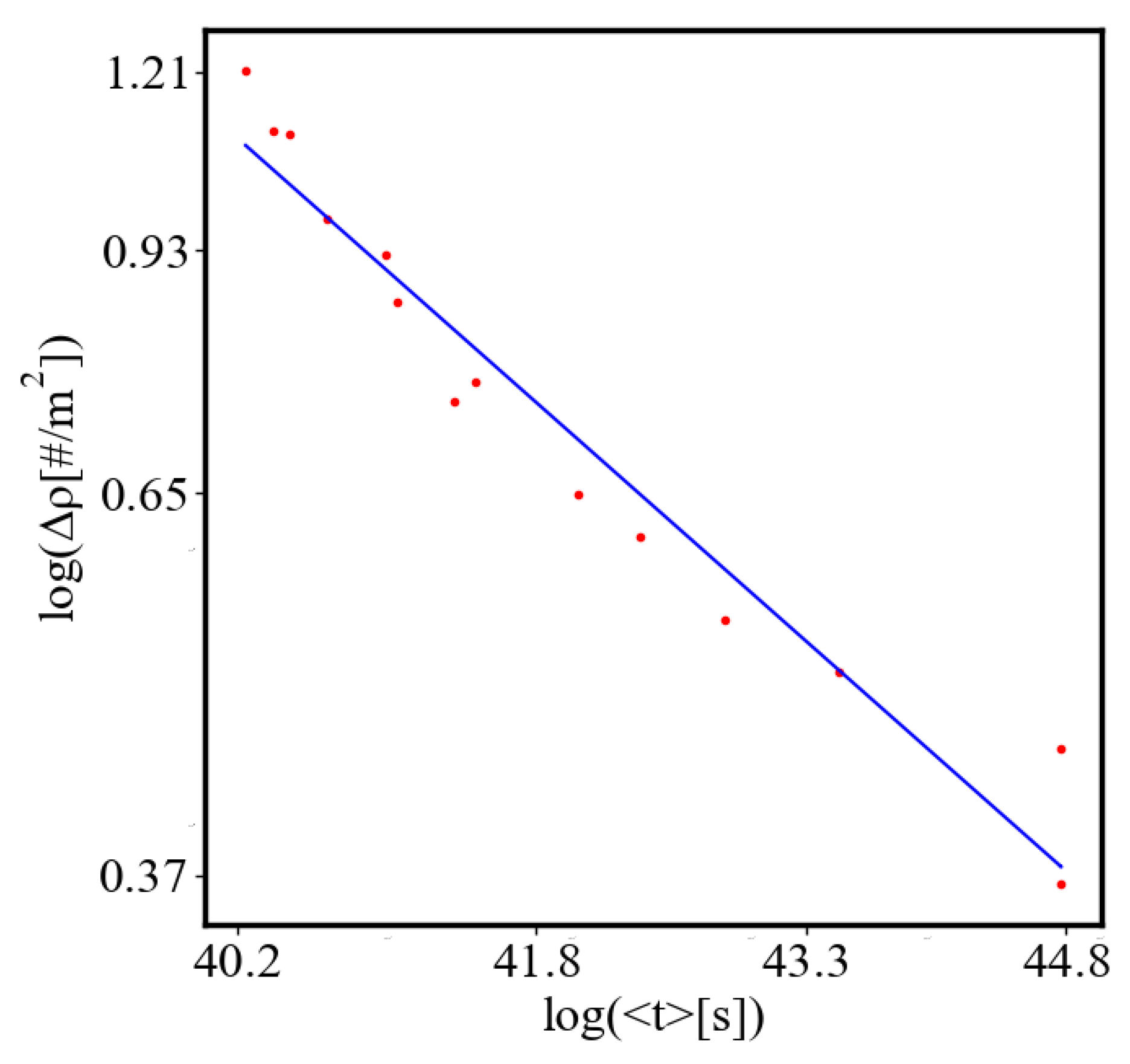

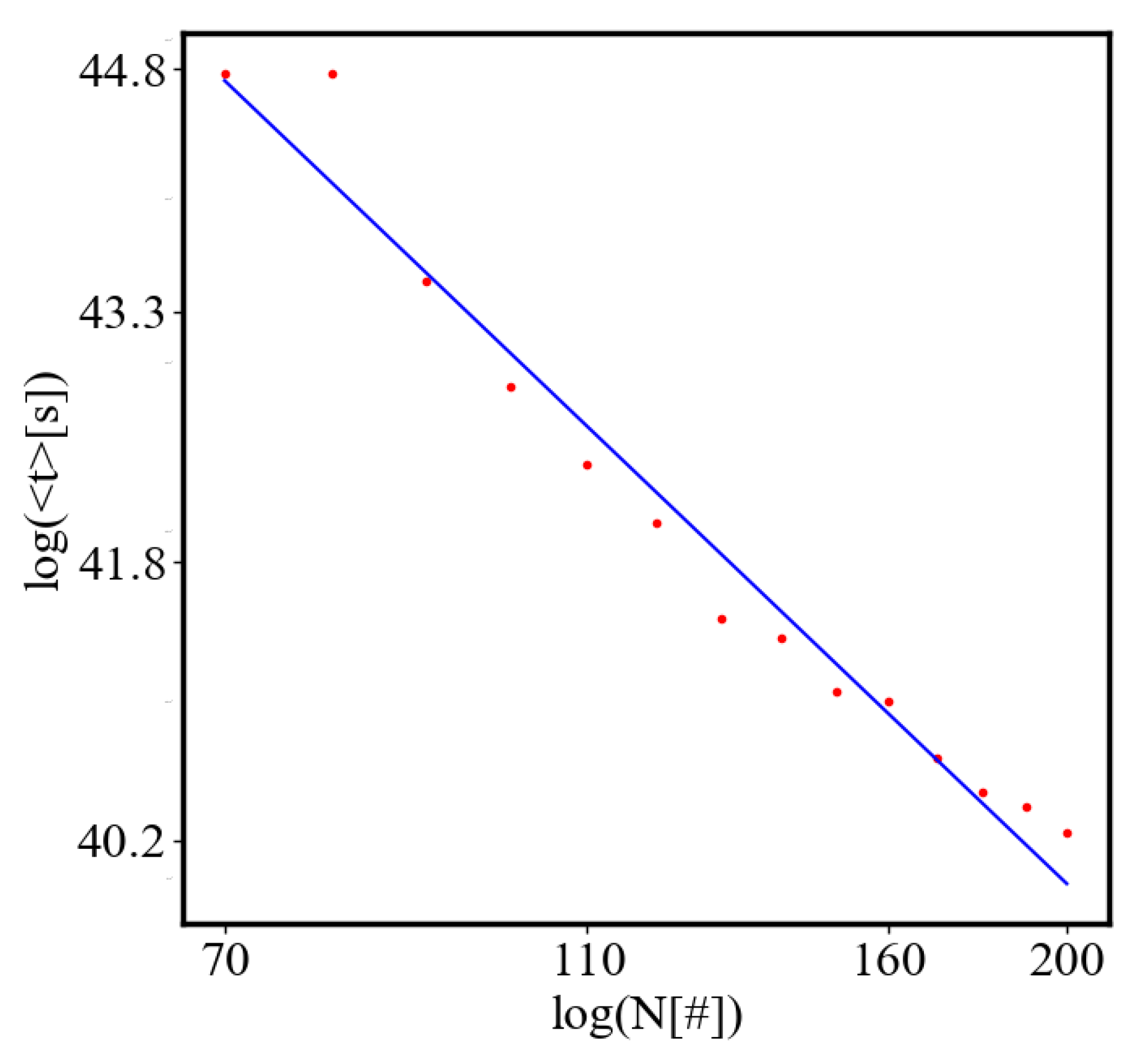

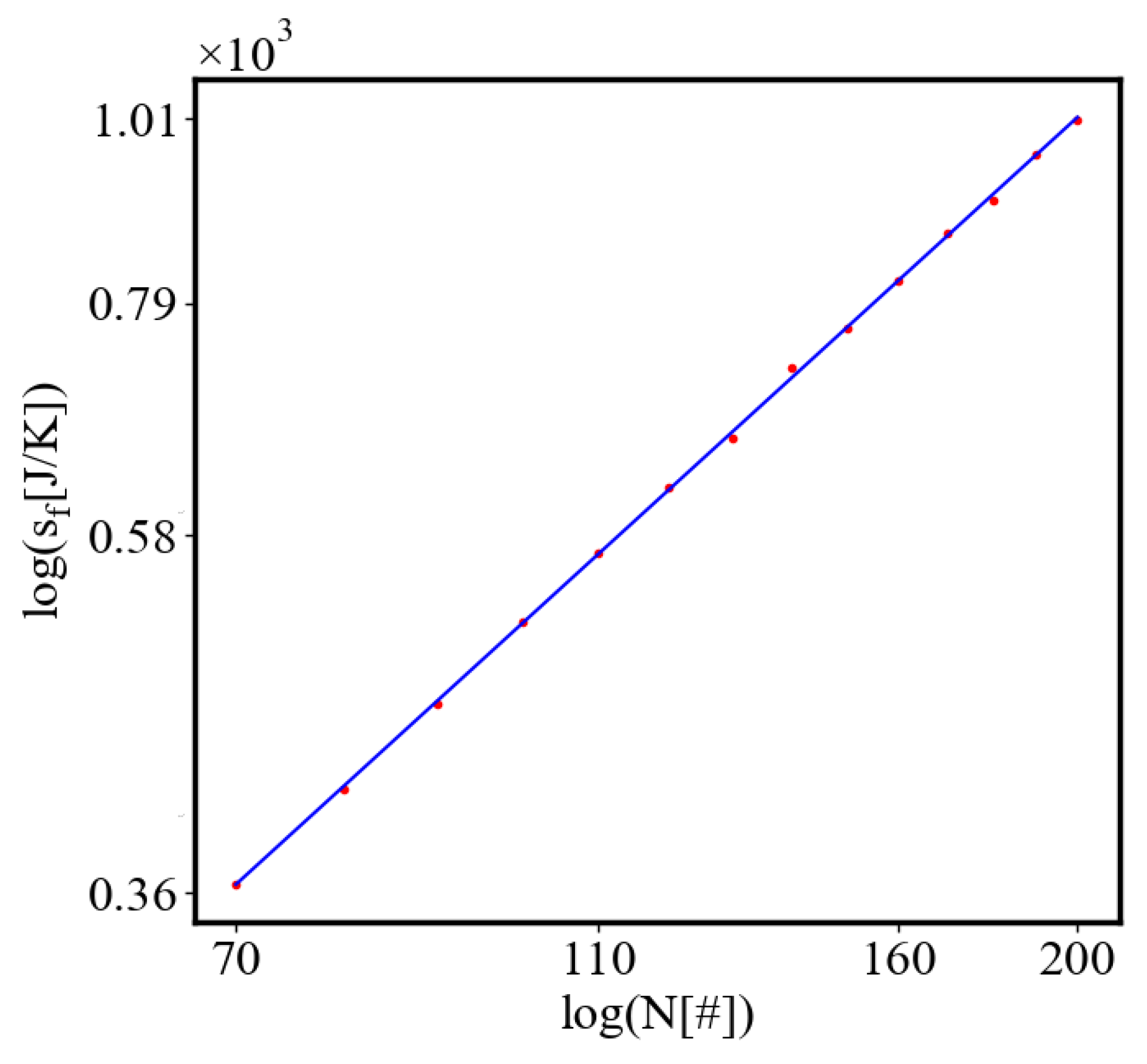

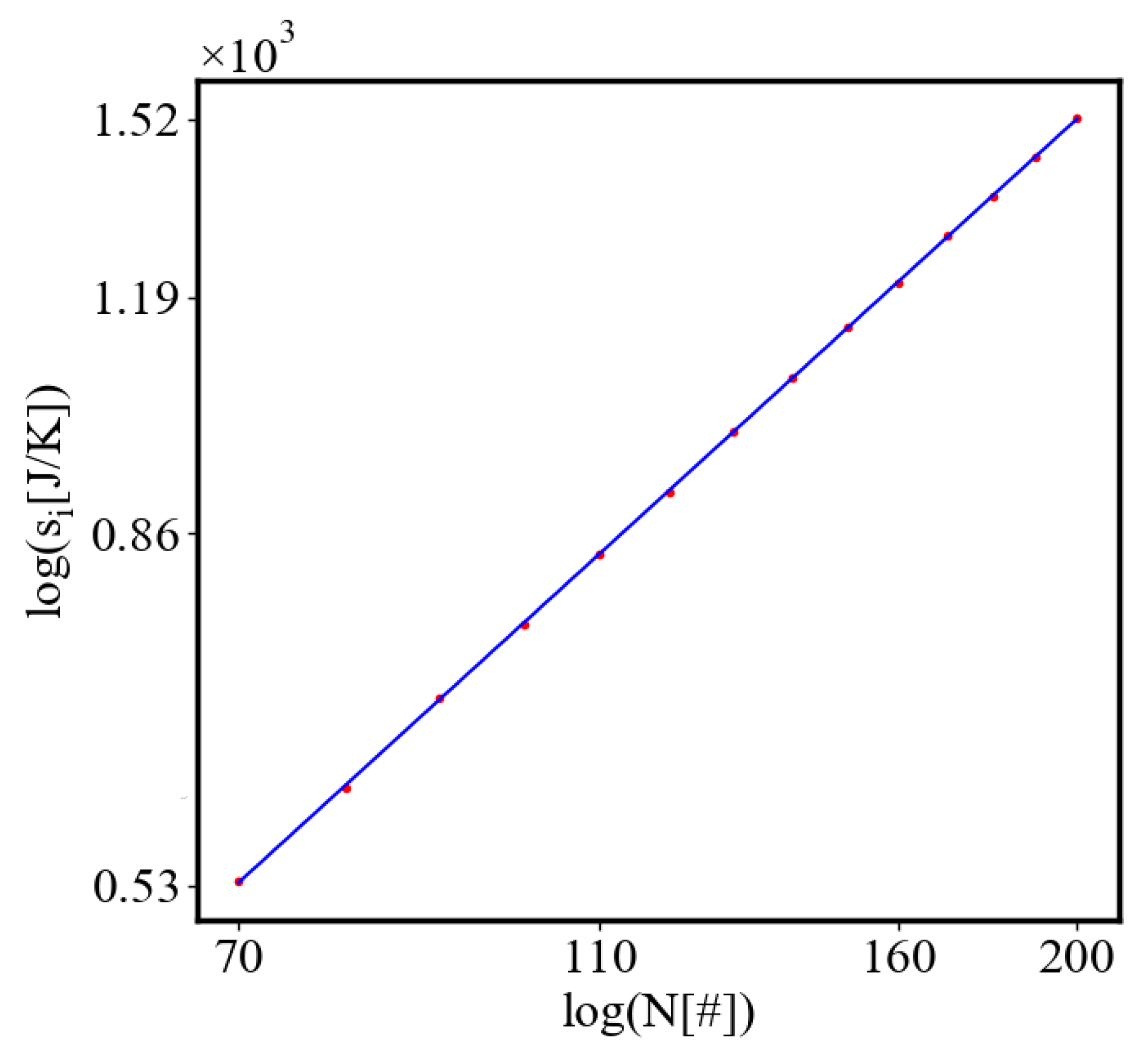

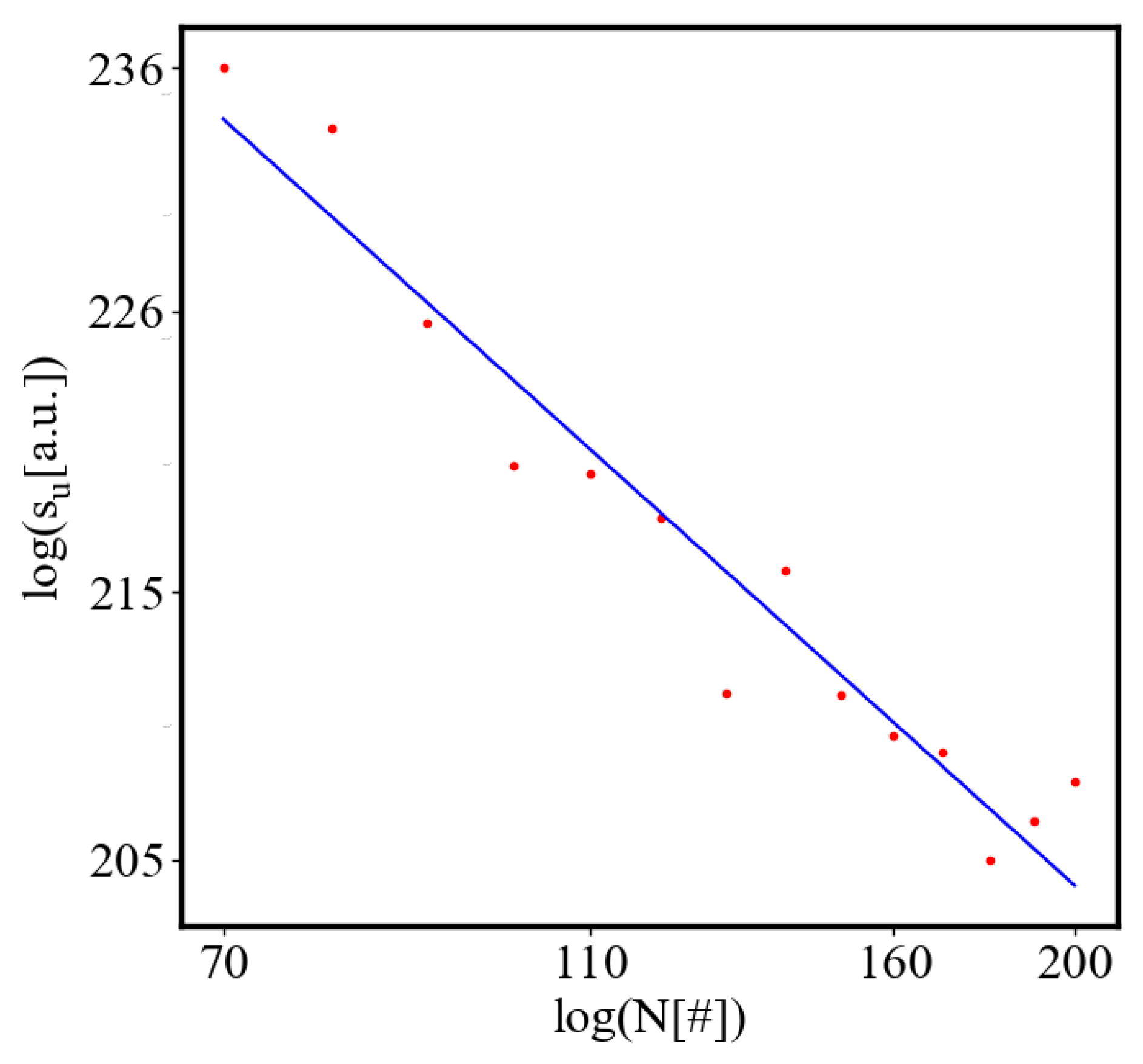

6.2. Power Law Graphs

6.2.1. Size-Complexity rule

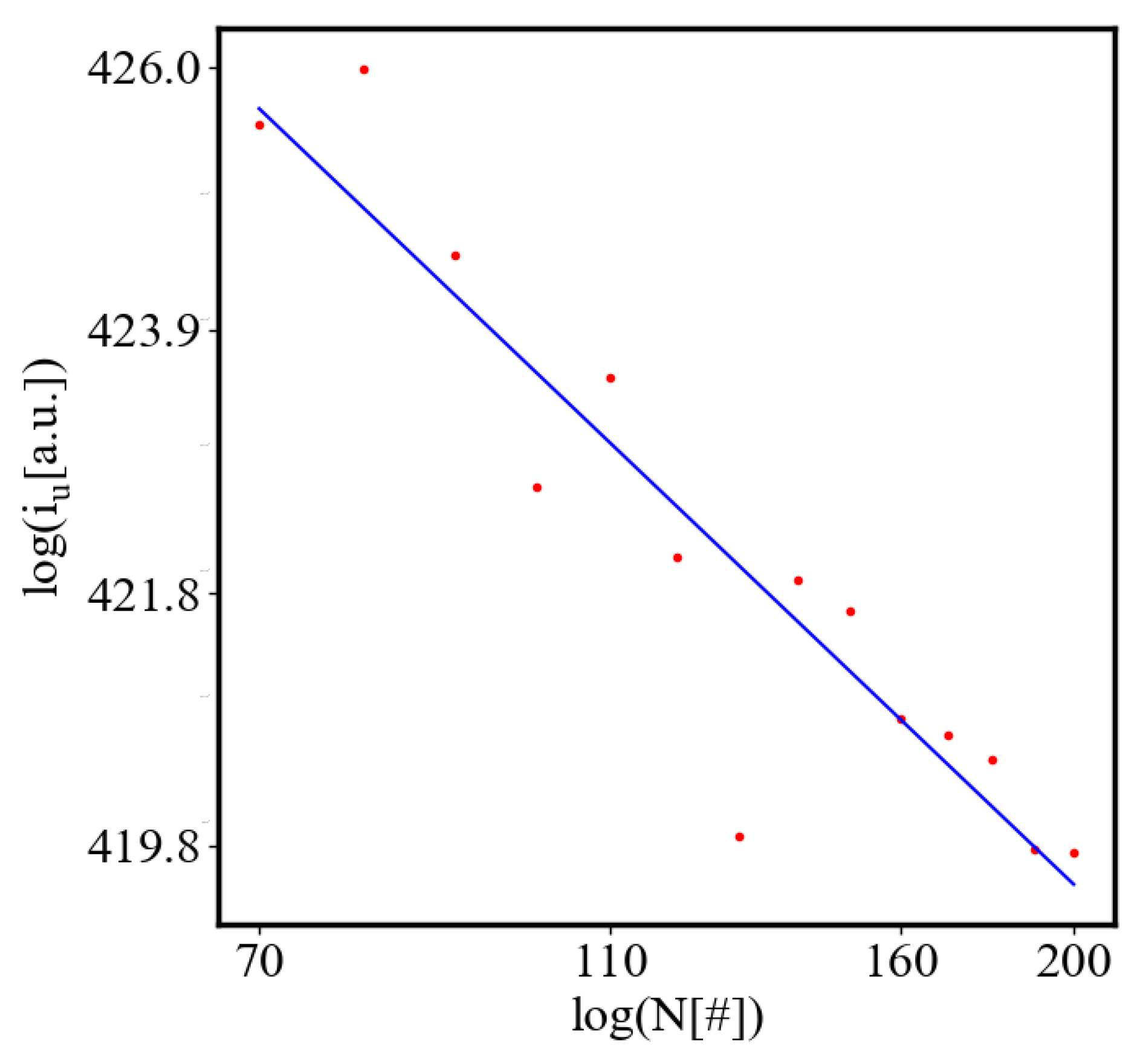

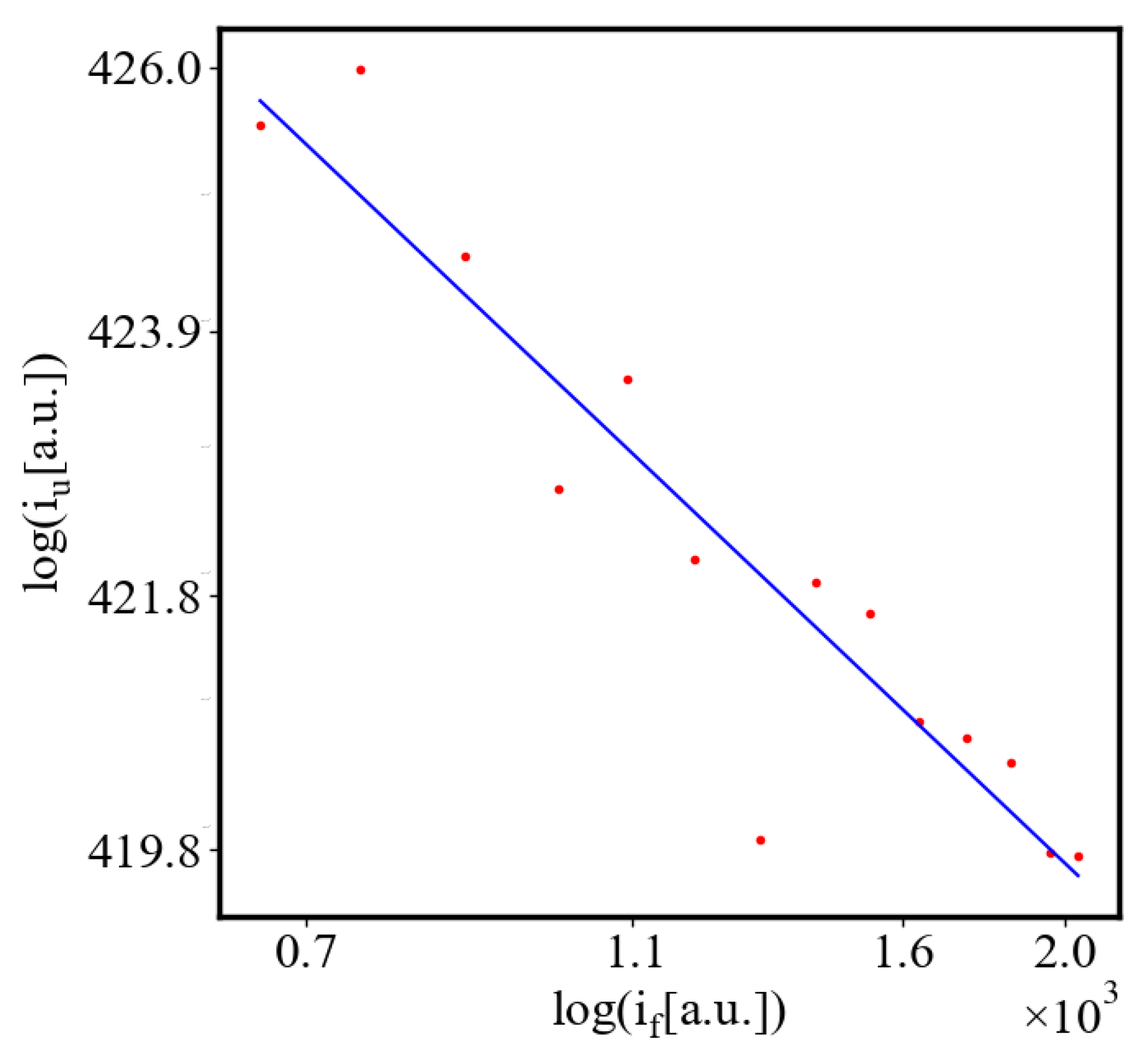

6.2.2. Unit-Total Dualism

6.2.3. the Rest of the Characteristics

6.3. Comparison with Literature Data for Real Systems

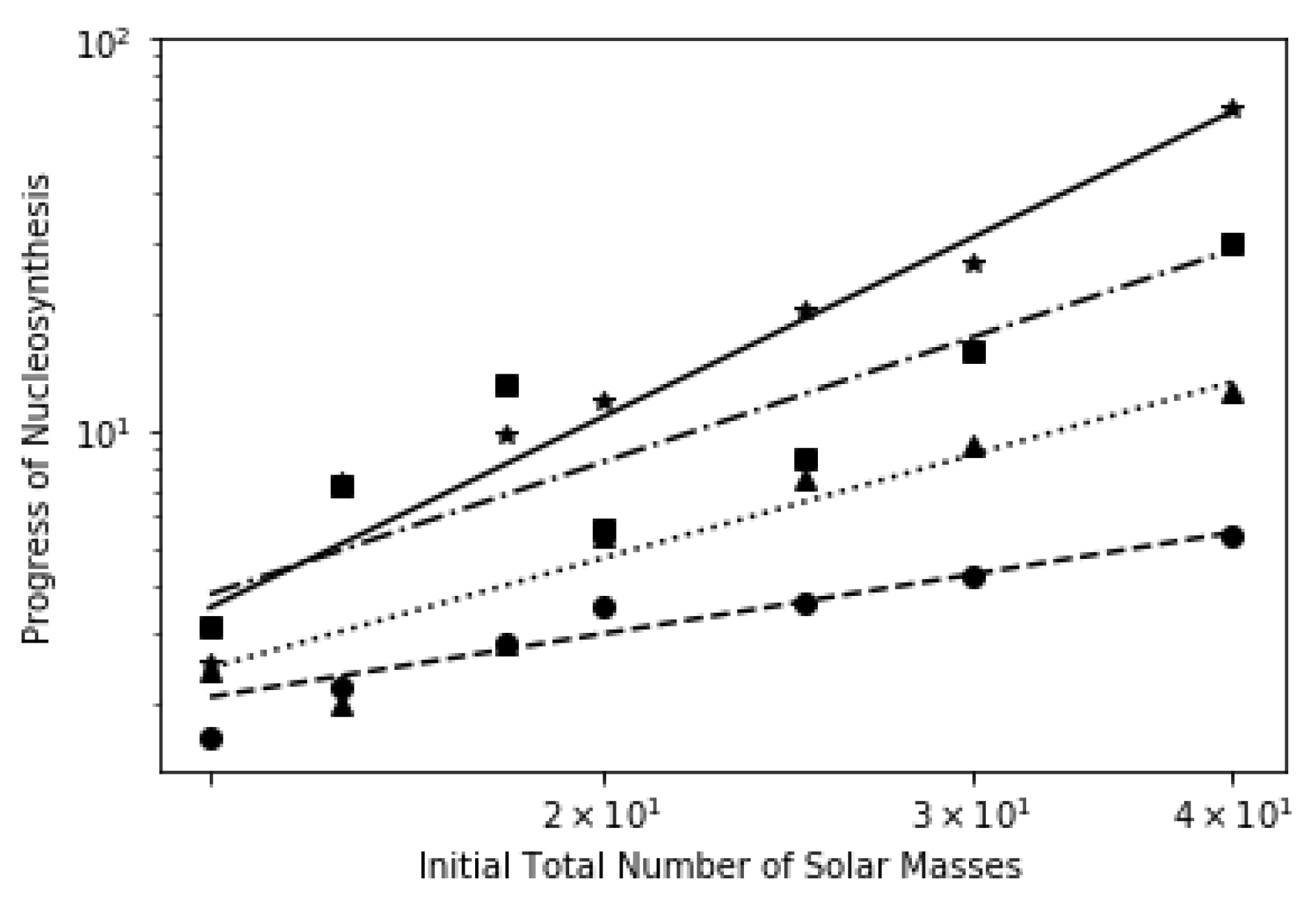

6.3.1. Stellar Evolution

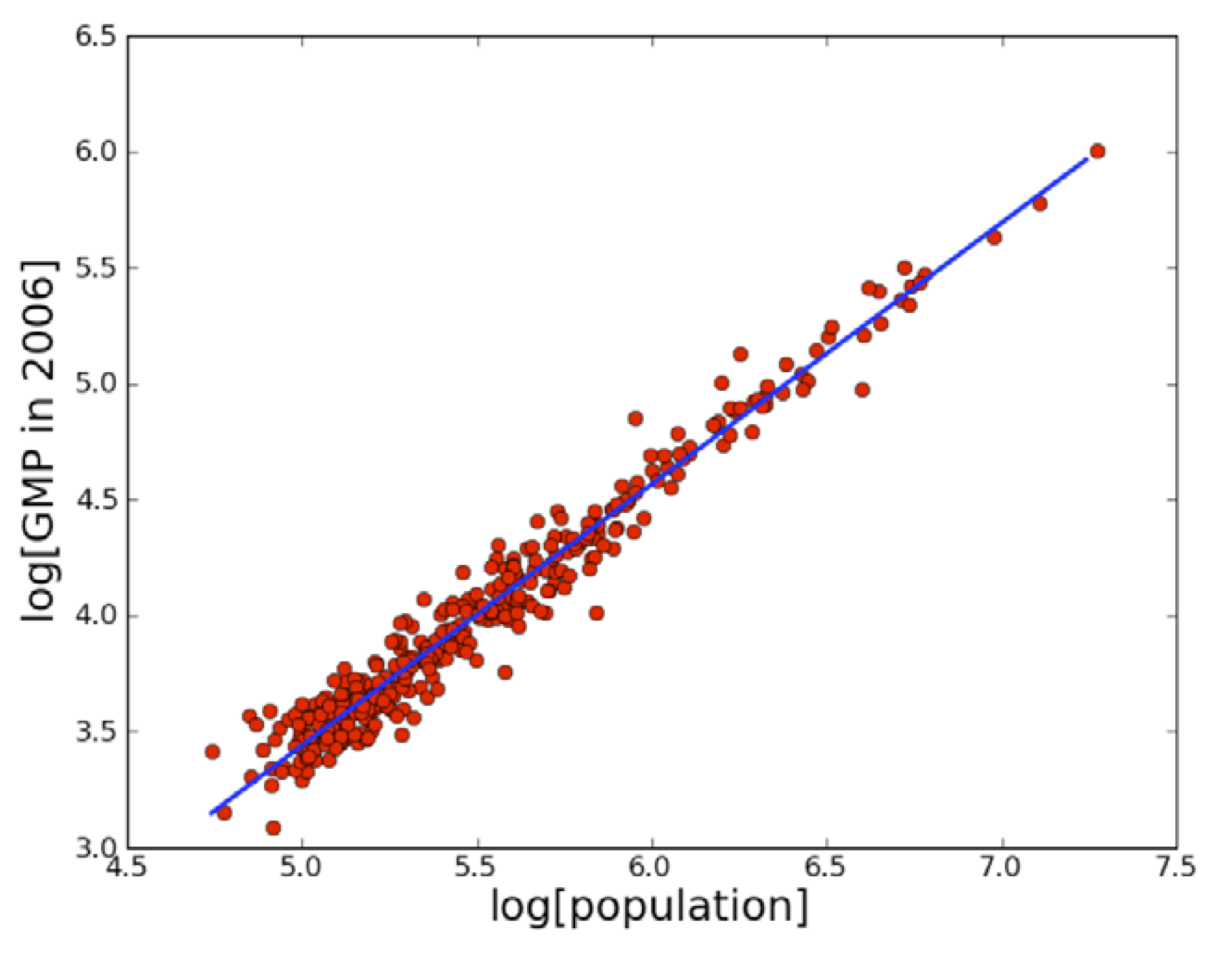

6.3.2. Evolution of Cities

6.3.3. Further Confirmation with Literature Data

6.4. A Table Presenting the Fit Values for the Power Law Relationships in the Simulation

| variables | a | b | |

| vs. Q | |||

| vs. i | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. N | |||

| Q vs. i | |||

| Q vs. | |||

| Q vs. | |||

| Q vs. | |||

| Q vs. | |||

| Q vs. N | |||

| i vs. | |||

| i vs. | |||

| i vs. | |||

| i vs. | |||

| i vs. N | |||

| vs. | 0.873 | ||

| vs. N | 0.864 | ||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. N | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. N | |||

| vs. N | |||

| vs. N | |||

| vs. N | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. | |||

| vs. N | |||

| vs. N |

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

8.0.1. Future Work

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Prigogine, I. Introduction to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes, 2nd ed.; Interscience Publishers/John Wiley and Sons: New York, 1961.

- Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. Modern thermodynamics: from heat engines to dissipative structures; John Wiley and sons, 2014.

- Sagan, C. Cosmos; Random House: New York, 1980.

- Chaisson, E.J. Cosmic evolution; Harvard University Press, 2002.

- Kurzweil, R. The singularity is near: When humans transcend biology; Penguin, 2005.

- Azarian, B. The romance of reality: How the universe organizes itself to create life, consciousness, and cosmic complexity; Benbella books, 2022.

- Walker, S.I. Life as No One Knows It: The Physics of Life’s Emergence; Riverhead Books: New York, USA, 2024. Published on August 6, 2024.

- Bejan, A. The physics of life: the evolution of everything; St. Martin’s Press, 2016.

- Georgiev, G.Y. The development: From the atom to the society; Sofia, 1993. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Call Number: III 186743.

- Georgiev, G.Y. Personal Journal, 1986. L12, p.23.

- De Bari, B.; Dixon, J.; Kondepudi, D.; Vaidya, A. Thermodynamics, organisms and behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2023, 381, 20220278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- England, J.L. Self-organized computation in the far-from-equilibrium cell. Biophysics Reviews 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.I.; Davies, P.C. The algorithmic origins of life. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 2013, 10, 20120869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, S.I. The new physics needed to probe the origins of life. Nature 2019, 569, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, G.; Georgiev, I. The least action and the metric of an organized system. Open systems & information dynamics 2002, 9, 371. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, G.Y.; Gombos, E.; Bates, T.; Henry, K.; Casey, A.; Daly, M. Free Energy Rate Density and Self-organization in Complex Systems. In Proceedings of ECCS 2014; Springer, 2016; pp. 321–327.

- Georgiev, G.Y.; Henry, K.; Bates, T.; Gombos, E.; Casey, A.; Daly, M.; Vinod, A.; Lee, H. Mechanism of organization increase in complex systems. Complexity 2015, 21, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, G.Y.; Chatterjee, A.; Iannacchione, G. Exponential Self-Organization and Moore’s Law: Measures and Mechanisms. Complexity 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.H.; Georgiev, G.Y. Self-Organization in Stellar Evolution: Size-Complexity Rule. In Efficiency in Complex Systems: Self-Organization Towards Increased Efficiency; Springer, 2021; pp. 53–80.

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics. Physical Review 1957, 106, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. Complexity Measures - an Article about Simplicity and Complexity. Complexity 1995, 1, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yockey, H.P. Information Theory, Evolution, and The Origin of Life; Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Crutchfield, J.P.; Feldman, D.P. Information Measures, Effective Complexity, and Total Information. Physical Review E 2003, 67, 061306. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.L.; Beer, R.D. Information-Theoretic Measures for Complexity Analysis. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science 2010, 20, 037115. [Google Scholar]

- Ay, N.; Olbrich, E.; Bertschinger, N.; Jost, J. Quantifying Complexity Using Information Theory, Machine Learning, and Algorithmic Complexity. Journal of Complexity 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Three approaches to the quantitative definition of information. Problems of Information Transmission 1965, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassberger, P. Toward a quantitative theory of self-generated complexity. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1986, 25, 907–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, S.M. Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1991, 88, 2297–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Goldberger, A.L.; Peng, C.K. Multiscale entropy analysis of complex physiologic time series. Physical review letters 2002, 89, 068102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizier, J.T.; Prokopenko, M.; Zomaya, A.Y. Local information transfer as a spatiotemporal filter for complex systems. Physical Review E 2008, 77, 026110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosso, O.A.; Larrondo, H.A.; Martin, M.T.; Plastino, A.; Fuentes, M.A. Distinguishing noise from chaos. Physical Review Letters 2007, 99, 154102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maupertuis, P.L.M.d. Essay de cosmologie; Netherlands, De l’Imp. d’Elie Luzac, 1751.

- Goldstein, H. Classical Mechanics; Addison-Wesley, 1980.

- Taylor, J.C. Hidden unity in nature’s laws; Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Lauster, M. On the Principle of Least Action and Its Role in the Alternative Theory of Nonequilibrium Processes. In Variational and Extremum Principles in Macroscopic Systems; Elsevier, 2005; pp. 207–225.

- Nath, S. Novel molecular insights into ATP synthesis in oxidative phosphorylation based on the principle of least action. Chemical Physics Letters 2022, 796, 139561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bersani, A.M.; Caressa, P. Lagrangian descriptions of dissipative systems: a review. Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids 2021, 26, 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, R.G. Entropy production selects nonequilibrium states in multistable systems. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 14437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M.; Seleznev, V.D. Maximum entropy production principle in physics, chemistry and biology. Physics reports 2006, 426, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M. Maximum entropy production principle: History and current status. Physics-Uspekhi 2021, 64, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R. Information theory explanation of the fluctuation theorem, maximum entropy production and self-organized criticality in non-equilibrium stationary states. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 2003, 36, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C. Maximum entropy production and the fluctuation theorem. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 2005, 38, L371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Physical review 1957, 106, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. II. Physical review 1957, 108, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, U. Entropy generation: Minimum inside and maximum outside. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2014, 396, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, U.; Grazzini, G. The second law today: using maximum-minimum entropy generation. Entropy 2015, 17, 7786–7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay-Balmaz, F.; Yoshimura, H. A Lagrangian variational formulation for nonequilibrium thermodynamics. Part II: continuum systems. Journal of Geometry and Physics 2017, 111, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay-Balmaz, F.; Yoshimura, H. From Lagrangian mechanics to nonequilibrium thermodynamics: A variational perspective. Entropy 2019, 21, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay-Balmaz, F.; Yoshimura, H. Systems, variational principles and interconnections in non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2023, 381, 20220280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaila, V.R.; Annila, A. Natural selection for least action. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2008, 464, 3055–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annila, A.; Salthe, S. Physical foundations of evolutionary theory 2010.

- Munkhammar, J. Quantum mechanics from a stochastic least action principle. Foundational Questions Institute Essay 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Hua, Y.C.; Guo, Z.Y. The principle of least action for reversible thermodynamic processes and cycles. Entropy 2018, 20, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.; Pellicer, J.; Manzanares, J.A. Thermodynamics based on the principle of least abbreviated action: Entropy production in a network of coupled oscillators. Annals of Physics 2008, 323, 1844–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Maximum entropy change and least action principle for nonequilibrium systems. Astrophysics and Space Science 2006, 305, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, H.; Ohmura, A.; Lorenz, R.D.; Pujol, T. The second law of thermodynamics and the global climate system: A review of the maximum entropy production principle. Reviews of Geophysics 2003, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niven, R.K.; Andresen, B. Jaynes’ maximum entropy principle, Riemannian metrics and generalised least action bound. In Complex Physical, Biophysical and Econophysical Systems; World Scientific, 2010; pp. 283–317.

- Herglotz, G.B. Lectures at the University of Göttingen. University of Göttingen: Göttingen, Germany 1930.

- Georgieva, B.; Guenther, R.; Bodurov, T. Generalized variational principle of Herglotz for several independent variables. First Noether-type theorem. Journal of Mathematical Physics 2003, 44, 3911–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhang, Y. Noether’s theorem for fractional Herglotz variational principle in phase space. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2019, 119, 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- Beretta, G.P. The fourth law of thermodynamics: steepest entropy ascent. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2020, 378, 20190168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigogine, I. Etude thermodynamique des phénomènes irréversibles. These d’agregation presentee a la taculte des sciences de I’Universite Libre de Bruxelles 1945 1947.

- Lyapunov, A.M. The general problem of the stability of motion. International journal of control 1992, 55, 531–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonner, J.T. Perspective: the size-complexity rule. Evolution 2004, 58, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, R.L. On the relationship between size of population and complexity of social organization. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 1967, 23, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.B. Scale: the universal laws of growth, innovation, sustainability, and the pace of life in organisms, cities, economies, and companies; Penguin, 2017.

- Gershenson, C.; Trianni, V.; Werfel, J.; Sayama, H. Self-organization and artificial life. Artificial Life 2020, 26, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayama, H. Introduction to the modeling and analysis of complex systems; Open SUNY Textbooks, 2015.

- Carlson, J.M.; Doyle, J. Complexity and robustness. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2002, 99, 2538–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution; Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Heylighen, F.; Joslyn, C. Cybernetics and second-order cybernetics. Encyclopedia of physical science & technology 2001, 4, 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jevons, W.S. The coal question; an inquiry concerning the progress of the nation and the probable exhaustion of our coal-mines; Macmillan, 1866.

- Berkhout, P.H.; Muskens, J.C.; Velthuijsen, J.W. Defining the rebound effect. Energy policy 2000, 28, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildenbrand, W. On the" law of demand". Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 1983, pp. 997–1019.

- Saunders, H.D. The Khazzoom-Brookes postulate and neoclassical growth. The Energy Journal 1992, 13, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, A. Stuck in traffic: Coping with peak-hour traffic congestion; Brookings Institution Press, 2000.

- Feynman, R.P. Space-Time Approach to Non-Relativistic Quantum Mechanics. Reviews of Modern Physics 1948, 20, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauß, C.F. Über ein neues allgemeines Grundgesetz der Mechanik.; Walter de Gruyter, Berlin/New York Berlin, New York, 1829.

- LibreTexts. 5.3: The Uniform Distribution, 2023. Accessed: 2024-07-15.

- Kleiber, M.; others. Body size and metabolism. Hilgardia 1932, 6, 315–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettencourt, L.M.; Lobo, J.; Strumsky, D.; West, G.B. Urban scaling and its deviations: Revealing the structure of wealth, innovation and crime across cities. PloS one 2010, 5, e13541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Short Biography of Author

|

Matthew Brouillet is a student at Washington University as part of the Dual Degree program with Assumption University. His major is Mechanical Engineering, and he has experience with computer programming. He developed the NetLogo programs for these simulations and utilized Python code to analyze the data. He is working with Dr. Georgiev to publish numerous papers in the field of self-organization. |

|

Dr. Georgi Y. Georgiev is a Professor of Physics at Assumption University and Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He earned his Ph.D. in Physics from Tufts University, Medford, MA. His research focuses on the physics of complex systems, exploring the role of variational principles in self-organization, the principle of least action, path integrals, and the Maximum Entropy Production Principle. Dr. Georgiev has developed a new model that explains the mechanism, driving force, and attractor of self-organization. He has published extensively in these areas and he has been an organizer of international conferences on complex systems. |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

| ant-speed | 1 patch/tick | Constant speed |

| wiggle range | 50 degrees | random directional change, from -25 to +25 |

| view-angle | 135 degrees | Angle of cone where ants can detect pheromone |

| ant-size | 2 patches | Radius of ants, affects radius of pheromone viewing cone |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

| Diffusion rate | 0.7 | Rate at which pheromones diffuse |

| Evaporation rate | 0.06 | Rate at which pheromones evaporate |

| Initial pheromone | 30 units | Initial amount of pheromone deposited |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

| projectile-motion | off | Ants have constant energy |

| start-nest-only | off | Ants start randomly |

| max-food | 0 | Food is infinite, food will disappear if this is greater than 0 |

| constant-ants | on | Number of ants is constant |

| world-size | 40 | World ranges from -20 to +20, note that the true world size is 41x41 |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

| food-nest-size | 5 | The length and width of the food and nest boxes |

| foodx | -18 | The position of the food in the x-direction |

| foody | 0 | The position of the food in the y-direction |

| nestx | +18 | The position of the nest in the x-direction |

| nesty | 0 | The position of the nest in the y-direction |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).