Section 1. Introduction

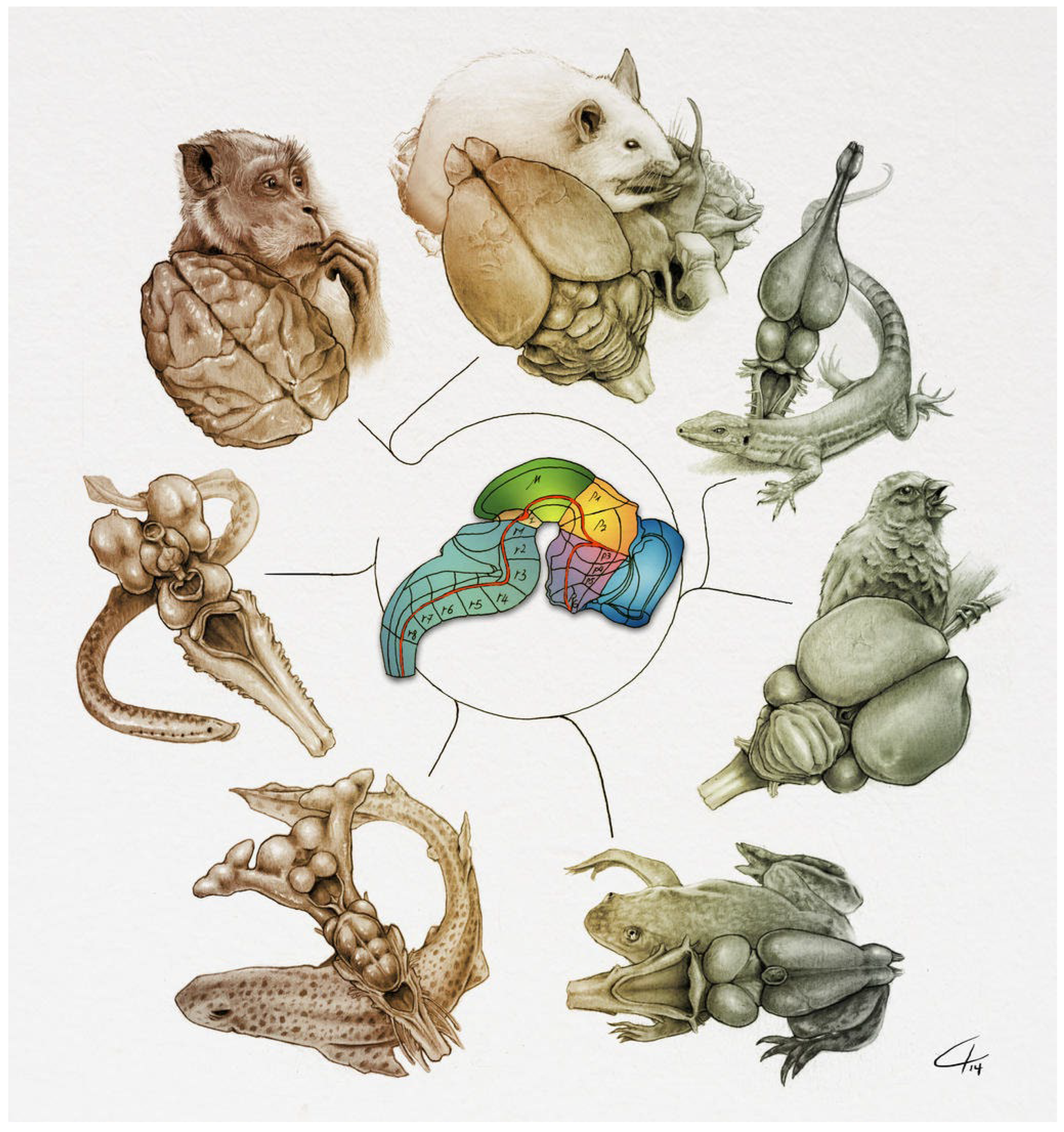

The evolution of the central nervous system (CNS) represents one of the most extraordinary examples of biological innovation in the history of life on Earth, embodying both the remarkable plasticity of evolutionary processes and the incremental nature of complex trait development (Striedter et al., 2014). The vertebrate nervous system, with its intricate architecture and sophisticated information processing capabilities, emerged through a series of evolutionary transitions that transformed a simple nerve cord into the most complex biological structure known to science – the human brain. Understanding this evolutionary trajectory not only illuminates our biological heritage but also provides crucial insights into modern human neurobiology and its associated pathologies (Rakic, 2009).

The fundamental organization of the vertebrate nervous system emerged over 500 million years ago, during the Cambrian period, when the first vertebrates diverged from their chordate ancestors (Holland et al., 2013). This ancient origin is reflected in the deep homology of neural development across vertebrates, evidenced by shared genetic networks and developmental patterns that persist from lampreys to humans (Sugahara et al., 2017). The basic blueprint – a hollow nerve cord that develops through neurulation and becomes regionalized along its anterior-posterior axis – represents a conserved feature that has been elaborated upon throughout vertebrate evolution (Northcutt, 2002).

The emergence of neural crest cells marked a pivotal innovation in vertebrate evolution, contributing to the development of novel sensory systems and enhanced cephalization (Green et al., 2015). This multipotent cell population, unique to vertebrates, enabled the development of sophisticated sensory organs and complex cranial ganglia, fundamentally altering the way early vertebrates could interact with their environment (Bronner and LeDouarin, 2012). The neural crest's contribution to the development of a "new head" in vertebrates represents one of the most significant evolutionary innovations in animal history, providing the foundation for the elaborate sensory and cognitive capabilities of modern vertebrates (Northcutt and Gans, 1983).

The progressive elaboration of brain regions throughout vertebrate evolution reflects a series of adaptive responses to various ecological and behavioral challenges. The development of the telencephalon, particularly its pallial derivatives, represents a crucial innovation that set the stage for the evolution of complex cognitive abilities (Striedter, 2005). The emergence of the dorsal pallium, which would eventually give rise to the mammalian neocortex, established a neural substrate capable of sophisticated information processing and integration (Aboitiz and Montiel, 2015).

The transition from aquatic to terrestrial environments posed new sensory and motor challenges that drove significant modifications in brain organization. The evolution of the amniote brain was marked by expansions in various sensory and motor areas, reflecting the demands of terrestrial life (Butler and Hodos, 2005). These modifications included the elaboration of visual and motor processing centers, as well as the development of more sophisticated systems for spatial navigation and environmental mapping (Nieuwenhuys et al., 2014).

Section 1.1 Mammalian Radiation

The mammalian radiation brought about perhaps the most dramatic modifications in brain organization seen in vertebrate evolution. The emergence of the six-layered neocortex represented a quantum leap in neural processing capabilities (Kriegstein et al., 2006). This unique structure, characterized by its columnar organization and extensive horizontal connectivity, provided a neural substrate capable of processing and integrating information in increasingly sophisticated ways (Harris and Shepherd, 2015). The expansion of the neocortex was accompanied by the development of new circuits for emotional processing and memory formation, centered on the elaboration of the limbic system and its connections with cortical areas (LeDoux, 2012).

The primate lineage witnessed further dramatic developments in brain organization, particularly in the expansion and specialization of association cortices (Buckner and Krienen, 2013). The emergence of extended periods of development and the expansion of neural progenitor populations contributed to the remarkable enlargement of the primate brain, particularly in areas involved in higher-order cognitive processing (Geschwind and Rakic, 2013). The evolution of sophisticated social cognition networks, including mirror neuron systems and theory of mind circuits, reflects the increasing importance of social intelligence in primate evolution (Rizzolatti and Craighero, 2004).

Section 1.2 The Human Brain

The human brain represents the culmination of these evolutionary trends, with several unique features that distinguish it from other primate brains. The dramatic expansion of the prefrontal cortex, particularly its dorsolateral regions, provided the neural substrate for advanced executive functions and abstract reasoning (Teffer and Semendeferi, 2012). The enhancement of language-related areas, including Broca's and Wernicke's areas, enabled the development of complex linguistic abilities that fundamentally altered human cognitive capabilities (Friederici, 2011). The emergence of extended networks supporting consciousness and self-awareness represents one of the most remarkable achievements of vertebrate brain evolution (Dehaene and Changeux, 2011).

Section 1.3 Neuroplasticity

Recent research has revealed that the evolution of the human brain involved not only quantitative changes in size and neuron number but also qualitative modifications in neural organization and connectivity. The human brain exhibits unique patterns of gene expression, particularly in areas involved in higher-order cognition (Sousa et al., 2017). These molecular innovations have contributed to changes in synaptic organization, dendritic complexity, and neural plasticity that distinguish human neural circuits from those of other primates (Geschwind and Rakic, 2013).

The evolution of enhanced neural plasticity and extended developmental periods in humans has had profound implications for learning and cultural transmission. The human brain's prolonged period of postnatal development, coupled with its remarkable plasticity, enables the acquisition of complex cultural knowledge and skills that have become essential to human survival and success (Henrich, 2017). This biological foundation for cultural learning represents a unique adaptation that has allowed humans to develop and transmit increasingly sophisticated technologies and social systems (Boyd et al., 2011).

Section 1.4 Evolutionary Medicine

Understanding the evolutionary history of the vertebrate CNS has important implications for modern medicine and neuroscience. Many neurological and psychiatric disorders can be better understood in light of evolutionary history, as they often involve disruptions to conserved neural systems or recent evolutionary innovations (Geschwind and Rakic, 2013). The study of brain evolution also provides insights into the constraints and opportunities that shaped human cognitive evolution, informing our understanding of both normal brain function and pathological conditions (Striedter et al., 2014).

The field of evolutionary neuroscience continues to be transformed by new technologies and approaches. Advanced imaging techniques, including high-resolution microscopy and non-invasive brain imaging, are revealing previously unknown aspects of brain organization across species (Rilling, 2014). Comparative genomics and transcriptomics are illuminating the molecular basis of brain evolution, identifying key genetic changes that contributed to the emergence of novel neural features (Sousa et al., 2017). The integration of developmental biology with evolutionary studies is providing new insights into the mechanisms by which evolutionary changes in neural development gave rise to innovations in brain structure and function (Geschwind and Rakic, 2013).

The study of vertebrate brain evolution also raises important questions about the nature of consciousness and cognitive complexity. The gradual emergence of increasingly sophisticated neural systems challenges simplistic notions about the uniqueness of human consciousness and suggests a continuum of cognitive capabilities across vertebrates (Feinberg and Mallatt, 2016). This evolutionary perspective has important implications for our understanding of animal cognition and raises ethical considerations about our treatment of other species (Low et al., 2012).

Section 1.5 Looking to the Future

Looking to the future, several key questions remain in our understanding of vertebrate CNS evolution. These include the precise mechanisms by which novel neural circuits emerge, the relationship between structural and functional innovations in brain evolution, and the role of developmental modifications in generating evolutionary change in neural systems (Striedter et al., 2014). Addressing these questions will require continued integration of multiple scientific disciplines, including developmental biology, computational neuroscience, comparative neuroscience, and evolutionary genetics.

The evolution of the vertebrate central nervous system thus represents a remarkable example of how gradual modifications over millions of years can give rise to structures of extraordinary complexity and capability. From the simple nerve cord of early chordates to the sophisticated human brain, this evolutionary journey illuminates both the conservative nature of biological evolution and its capacity for remarkable innovation. As we continue to unravel this history, we gain not only a deeper understanding of our biological heritage but also crucial insights into the nature of human consciousness and cognition.

This intricate evolutionary narrative provides an essential framework for understanding both normal brain function and neurological disorders, while also raising profound questions about the nature of mind and consciousness. As we look to the future, continued research into the evolution of the vertebrate nervous system promises to yield new insights that will inform both basic science and clinical practice, while deepening our appreciation for the remarkable achievement that is the human brain.

Section 2. Discussion

The evolutionary trajectory of the vertebrate central nervous system presents a remarkable example of how incremental changes over geological time can produce structures of extraordinary complexity. This discussion synthesizes current understanding of the major transitions in CNS evolution while highlighting areas of ongoing research and debate.

Section 2.1 Evolutionary Innovations and Their Significance

The emergence of a centralized nervous system represents one of the most significant innovations in animal evolution, fundamentally altering how organisms process and respond to environmental information (Arendt et al., 2016). The basic organization of the vertebrate CNS, with its hollow neural tube and segmented structure, reflects and is limited by ancient evolutionary origins that predate the vertebrate radiation. However, the subsequent elaboration of this basic plan through various innovations has produced the remarkable diversity of vertebrate nervous systems observed today (Holland and Holland, 2021).

The development of neural crest cells stands as a pivotal innovation that distinguishes vertebrates from their chordate relatives. These multipotent cells have contributed to numerous vertebrate-specific features, including elaborate sensory systems and enhanced cephalization (Green and Bronner, 2018). Recent research has revealed that the gene regulatory networks controlling neural crest development are remarkably and topologically conserved across vertebrates, suggesting that modifications to these networks' deployment, rather than wholesale innovation, drove many aspects of vertebrate brain evolution (Martik and Bronner, 2017).

Section 2.2 Developmental Constraints and Opportunities

The evolution of the vertebrate CNS has been shaped by both developmental constraints and opportunities. The conservation of basic developmental pathways across vertebrates suggests strong selective pressure to maintain certain aspects of neural development (Puelles and Ferran, 2012). However, modifications to these pathways, particularly through changes in timing and spatial deployment of conserved developmental programs, have enabled significant evolutionary innovations (Striedter and Northcutt, 2020).

Recent studies in evolutionary developmental biology have highlighted the importance of changes in neural progenitor behavior in driving brain evolution. Modifications to the cell cycle length, symmetric versus asymmetric division patterns, and the timing of neurogenesis have contributed significantly to variations in brain size and organization across vertebrate lineages (Namba and Huttner, 2017). The expansion of outer radial glial cells in the primate lineage, for example, represents a key innovation that enabled the dramatic expansion of the neocortex (Florio and Huttner, 2014).

Section 2.3 The Role of Gene Regulation and Expression

Comparative genomic studies have revealed that changes in gene regulation, rather than the evolution of new genes, have played a primary role in vertebrate brain evolution. The emergence of new enhancer elements and modifications to existing regulatory networks has enabled the elaboration of brain structures while maintaining basic developmental programs (Reilly et al., 2015). Recent research has identified specific enhancer elements that contributed to the expansion of the human neocortex, highlighting the importance of regulatory evolution in human brain development (de la Torre-Ubieta et al., 2018).

The evolution of novel patterns of gene expression in specific brain regions has contributed to the emergence of new neural circuits and capabilities. Comparative transcriptomic studies have revealed human-specific patterns of gene expression in various brain regions, particularly in areas associated with higher cognitive functions (Sousa et al., 2017). These molecular innovations have implications for understanding both human cognitive evolution and neurological disorders.

Section 2.4 Structural and Functional Integration

The evolution of the vertebrate CNS has involved not only the emergence of new structures but also the integration of these structures into functional networks. The development of sophisticated connectivity patterns, particularly in the mammalian brain, has enabled increasingly complex information processing and behavioral responses (Buckner and Krienen, 2013). The evolution of long-range connectivity patterns in the primate brain, for example, has contributed to the emergence of distributed networks supporting higher cognitive functions (Markov et al., 2014).

Recent research using advanced imaging techniques has revealed that the human brain exhibits unique patterns of structural and functional connectivity compared to other primates. The expansion of association networks and the emergence of novel connectivity patterns in the human brain have contributed to our species' unique cognitive capabilities (Rilling et al., 2008). These findings highlight the importance of considering not only individual structures but also their integration into functional networks when studying brain evolution.

Section 2.5 Adaptive Significance and Selective Pressures

The evolution of increasingly complex nervous systems raises questions about the selective pressures that drove these changes. The "social brain hypothesis" suggests that the demands of living in complex social groups played a crucial role in driving primate brain evolution (Dunbar and Shultz, 2007). However, recent research has highlighted the importance of considering multiple selective pressures, including ecological factors, dietary changes, and technological innovation, in shaping human brain evolution (DeCasien et al., 2017).

The energetic costs associated with maintaining large brains have also played a crucial role in shaping CNS evolution. The human brain, despite comprising only about 2% of body weight, consumes approximately 20% of the body's energy budget at rest (Aiello and Wheeler, 1995). This high energetic cost suggests that the benefits of increased cognitive capability must have substantially outweighed the metabolic costs during human evolution (Navarrete et al., 2011).

Section 2.6 Implications for Human Cognition and Behavior

The evolutionary history of the vertebrate CNS has important implications for understanding human cognition and behavior. The layered nature of brain evolution, with new structures and capabilities building upon ancient foundations (Montgomery, 2024), helps explain both the capabilities and limitations of human cognitive processes (Anderson, 2010). This evolutionary perspective provides insights into why certain cognitive tasks are easier or more difficult for humans to perform and helps explain various cognitive biases and limitations(Montgomery, 2024a).

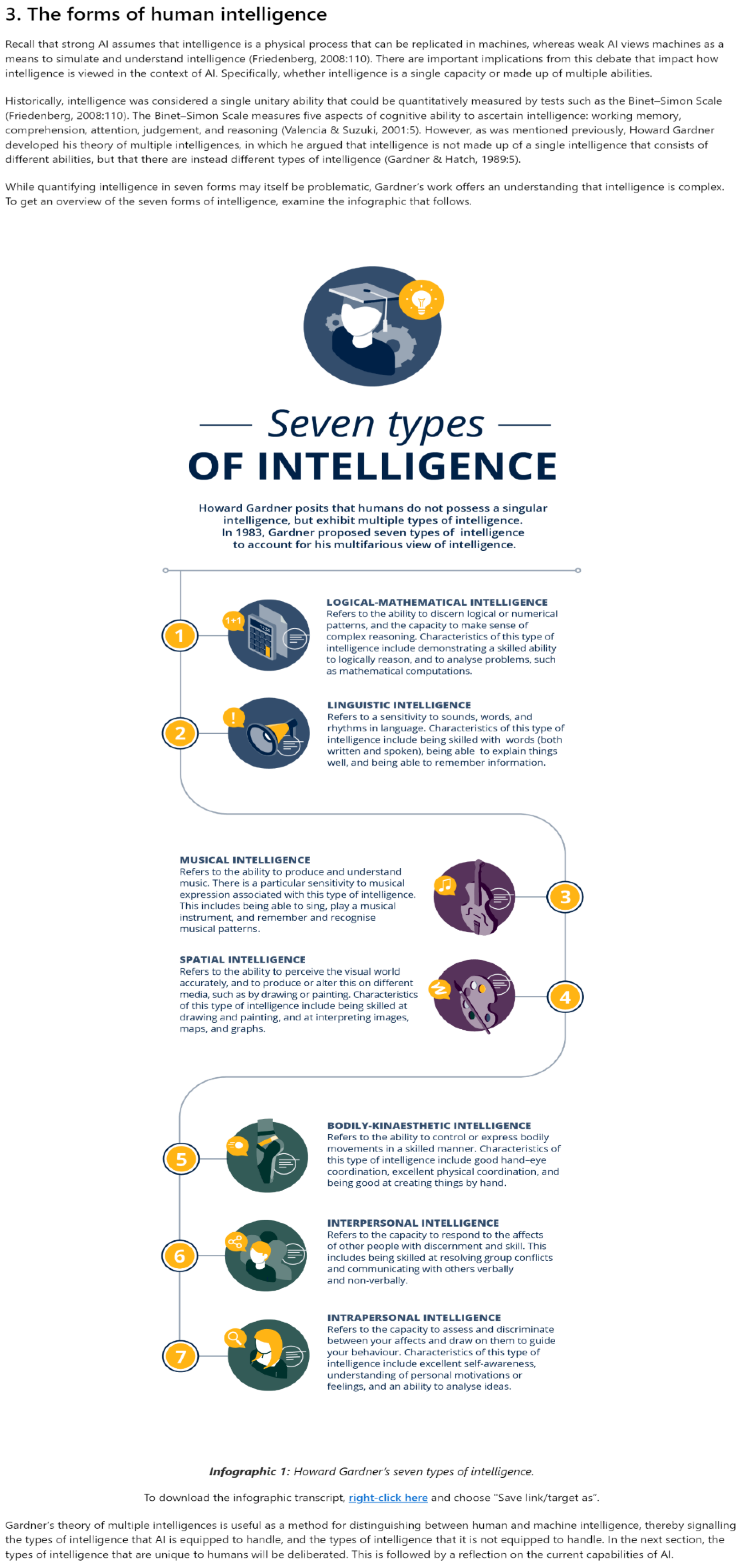

Figure 1.

Gardner´s Theory of Multiple Types of Human Intelligence. Source: Oxford University.

Figure 1.

Gardner´s Theory of Multiple Types of Human Intelligence. Source: Oxford University.

The extended period of human brain development, with its prolonged period of plasticity, represents a key adaptation that enables the acquisition of complex cultural knowledge and skills (Henrich, 2017). This biological foundation for cultural learning has enabled humans to develop and transmit increasingly sophisticated technologies and social systems, fundamentally altering our species' evolutionary trajectory (Boyd et al., 2011).

Section 2.7 Clinical and Medical Implications

Understanding the evolutionary history of the vertebrate CNS has important implications for medical practice and the treatment of neurological disorders. Many neurological and psychiatric conditions can be better understood when viewed through an evolutionary lens, as they often involve disruptions to either conserved neural systems or recent evolutionary innovations (Geschwind and Rakic, 2013).

The study of brain evolution also provides insights into why certain neural systems may be particularly vulnerable to dysfunction. The relatively recent evolution of complex cognitive capabilities in humans may help explain why these functions are often disrupted in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders (Crow, 1997). This evolutionary perspective can inform both our understanding of disease mechanisms and approaches to treatment.

Section 2.8 Methodological Advances and Future Directions

Recent technological advances have dramatically enhanced our ability to study brain evolution. New imaging techniques, including high-resolution microscopy and non-invasive brain imaging, are revealing previously unknown aspects of brain organization across species (Rilling, 2014). Advances in single-cell genomics and transcriptomics are providing unprecedented insights into the molecular basis of brain evolution and development (Trapnell, 2015).

The integration of multiple approaches, including comparative genomics, developmental biology, and neuroscience, is essential for understanding the complex process of brain evolution. Future research directions should focus on:

Elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying major evolutionary transitions in brain development

Understanding how changes in neural circuit organization contribute to cognitive evolution

Investigating the relationship between brain evolution and disease susceptibility

Exploring the role of plasticity and environmental interactions in shaping brain evolution

Section 2.9 Philosophical and Ethical Implications

The study of vertebrate brain evolution raises important philosophical questions about the nature of consciousness and cognitive complexity. The gradual emergence of increasingly sophisticated neural systems challenges simple dichotomies between "conscious" and "unconscious" organisms and suggests a continuum of cognitive capabilities across vertebrates (Feinberg and Mallatt, 2016).

This evolutionary perspective has important implications for how we think about animal consciousness and cognition. Recent research suggesting sophisticated cognitive capabilities in various vertebrate species raises ethical questions about our treatment of other animals and our responsibilities toward them (Low et al., 2012).

Section 2.10 Emerging Challenges and Opportunities

Several key challenges remain in our understanding of vertebrate CNS evolution. These include:

The difficulty of inferring neural function from fossil evidence

The complexity of relating genetic changes to modifications in neural circuit organization

The challenge of understanding how developmental changes translate into evolutionary innovations

The need to better understand the relationship between structural and functional changes in brain evolution (Montgomery, 2024b)

However, these challenges also present opportunities for future research. New technologies and approaches, including:

Advanced imaging techniques

Comparative genomics and transcriptomics

Sophisticated computational modeling

Novel experimental approaches in developmental biology

promise to provide new insights into these long-standing questions.

Section 2.11 Synthesis and Future Perspectives

The evolution of the vertebrate central nervous system represents one of the most remarkable examples of biological complexity emergence. From the simple nerve cord of early chordates to the sophisticated human brain, this evolutionary journey illuminates both the conservative nature of biological evolution and its capacity for remarkable innovation.

Understanding this history is crucial not only for basic science but also for medical practice and our conception of human nature. As we continue to unravel the complexities of brain evolution, we gain not only a deeper understanding of our biological heritage but also crucial insights into the nature of mind and consciousness.

The field of evolutionary neuroscience stands at an exciting juncture, with new technologies and approaches providing unprecedented opportunities to understand how complex nervous systems evolved. Future research will undoubtedly continue to reveal new insights into this remarkable evolutionary story, while also informing our understanding of human cognition and neurological disease.

The challenge for future research will be to integrate insights from multiple disciplines to build a more complete understanding of how the vertebrate nervous system evolved and continues to evolve. This understanding will be crucial for addressing both basic scientific questions and practical challenges in medicine and human health.

Section 2.12 The Great Cognitive Transition: Evolution of Human-like Intelligence

The emergence of human-like cognitive capabilities represents one of the most profound transitions in the history of life on Earth. While the evolution of basic intelligence spans the entire history of animal life, the development of human-level cognitive abilities occurred with remarkable rapidity in evolutionary terms, primarily within the last 2-3 million years. This extraordinary transformation has sparked intense scientific debate about its timing, causes, and mechanisms (Dunbar and Shultz, 2017).

The foundations for advanced cognition were laid long before the emergence of the human lineage. The mammalian radiation following the end-Cretaceous extinction event saw the evolution of increased brain size relative to body mass and the elaboration of cortical circuits supporting sophisticated sensory processing and motor control (Hoffmann et al., 2014). However, the transition to primate-specific cognitive capabilities marked a significant shift in the evolution of intelligence. The early primate brain showed several key innovations, including enhanced visual processing capabilities and improved hand-eye coordination, laying the groundwork for later cognitive developments (Preuss, 2011).

The emergence of the great apes marked another crucial step toward human-like cognition. Comparative studies between great apes and other primates have revealed significant expansions in areas associated with social cognition, tool use, and abstract thinking. The great ape lineage saw the evolution of more sophisticated mirror neuron systems, enhanced working memory capabilities, and improved executive functions (Rilling, 2014). However, the most dramatic cognitive developments occurred after the split between the human and chimpanzee lineages, approximately 5-7 million years ago.

Several key transitions mark the path toward human-like cognition. The first major shift occurred with the emergence of early Homo species, particularly Homo habilis and Homo erectus. These species showed significant increases in brain size and the first clear evidence of systematic tool use. Archaeological evidence suggests that Homo erectus, in particular, demonstrated cognitive capabilities far beyond those of earlier hominins, including the controlled use of fire, more sophisticated tool manufacturing, and possibly the beginnings of symbolic thought (Stout, 2011).

The period between 800,000 and 200,000 years ago saw another crucial transition. During this time, the brain size of our ancestors approached modern human levels, and archaeological evidence suggests increasingly sophisticated behavioral and technological capabilities. Recent genetic studies have identified several genes involved in brain development that underwent positive selection during this period, including FOXP2, which plays a crucial role in language development, and ASPM and MCPH1, which influence brain size and organization (Enard et al., 2009).

The emergence of modern human cognition, however, appears to have occurred relatively recently, possibly within the last 100,000 years. This period saw an explosion of symbolic behavior, including the creation of complex art, the development of sophisticated tools, and clear evidence of abstract thinking and planning. This "cognitive revolution" coincided with significant changes in human social organization and the emergence of complex cultural systems (Henrich, 2016).

Several theories attempt to explain the rapid evolution of human cognitive capabilities. The "social brain hypothesis" suggests that the primary driver was the need to navigate increasingly complex social relationships (Dunbar, 2009). According to this theory, the challenges of living in large, socially complex groups selected for enhanced cognitive capabilities, including theory of mind, emotional intelligence, and sophisticated communication abilities.

Alternative theories emphasize the role of ecological challenges. The "cognitive buffer hypothesis" suggests that enhanced cognitive capabilities (see Fig 1.) evolved as a way to cope with environmental variability and uncertainty (Sol, 2009). This theory points to the ability of human ancestors to colonize diverse environments and adapt to changing conditions as evidence for the selective advantage of enhanced cognitive flexibility.

Recent research has highlighted the crucial role of gene-culture coevolution in the development of human cognitive capabilities. The ability to generate and transmit cultural innovations created new selective pressures favoring enhanced cognitive abilities, which in turn enabled more sophisticated cultural developments. This feedback loop between biological and cultural evolution may help explain the remarkable pace of human cognitive evolution (Boyd et al., 2011).

The evolution of language capabilities played a particularly crucial role in this process. While the exact timing of language evolution remains debated, genetic and archaeological evidence suggests that the capacity for complex language evolved gradually, with crucial developments occurring within the last 200,000 years. The emergence of sophisticated linguistic abilities fundamentally transformed human cognitive capabilities, enabling complex social learning, abstract thinking, and the transmission of sophisticated cultural knowledge (Berwick and Chomsky, 2016).

Recent neuroscientific research has revealed several key features distinguishing the modern human brain from those of other primates. These include expanded association cortices, enhanced connectivity between different brain regions, and modifications to neural development that extend the period of synaptic plasticity (Buckner and Krienen, 2013). These changes support sophisticated cognitive capabilities, including abstract reasoning, mental time travel, and complex problem-solving abilities.

The human brain also shows unique patterns of gene expression, particularly in areas associated with higher cognitive functions. Comparative genomic studies have identified numerous human-specific changes in genes involved in neural development, synaptic function, and brain metabolism. These molecular innovations have contributed to the distinctive features of human cognition, including our capacity for complex language, abstract thought, and cultural learning (Sousa et al., 2017).

Understanding the evolution of human cognitive capabilities has important implications for both basic science and clinical medicine. Many psychiatric and neurological disorders affect cognitive domains that evolved relatively recently, suggesting that these systems may be particularly vulnerable to dysfunction (Montgomery, 2024c). This evolutionary perspective provides crucial insights into both normal cognitive function and pathological conditions (Crow, 2007).

Looking forward, several key questions remain about the evolution of human cognition. How did specific genetic changes translate into enhanced cognitive capabilities? What role did environmental and social factors play in driving cognitive evolution? How did the emergence of cultural transmission systems influence biological evolution? Addressing these questions will require continued integration of multiple scientific disciplines, from paleontology and archaeology to genomics and neuroscience.

The story of human cognitive evolution reminds us that our remarkable mental capabilities emerged through a complex interplay of biological and cultural evolution. This understanding not only illuminates our past but also provides crucial insights into human nature and the future possibilities for human cognitive development.

Section 2.13. Genetic Innovations in Human Cognitive Evolution

The genetic underpinnings of human cognitive evolution represent one of the most fascinating chapters in our species' history. Modern genomic analyses have revealed a complex tapestry of genetic changes that, layer by layer, contributed to the emergence of human cognitive capabilities. These modifications range from large-scale structural changes to subtle regulatory adjustments, each playing a crucial role in shaping our unique mental abilities.

Section 2.13.1 Early Genetic Foundations

The journey toward human cognition began long before our species emerged. Comparative genomic studies have revealed that many of the basic genetic tools for building complex brains were already present in early vertebrates. However, the human lineage has seen significant modifications to these ancient genetic systems. Recent research by Zhang et al. (2021) has identified several waves of gene duplication events that expanded families of neural development genes, particularly those involved in synaptic function and neural circuit formation.

One of the most significant early changes involved genes controlling brain development and size. The evolution of genes like ASPM and MCPH1, crucial regulators of neural progenitor proliferation, represents a key innovation in the primate lineage. Mutations in these genes cause microcephaly in humans, highlighting their essential role in achieving proper brain size. Evans et al. (2018) demonstrated that these genes underwent positive selection during human evolution, with several human-specific variants emerging during critical periods of brain size expansion.