Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

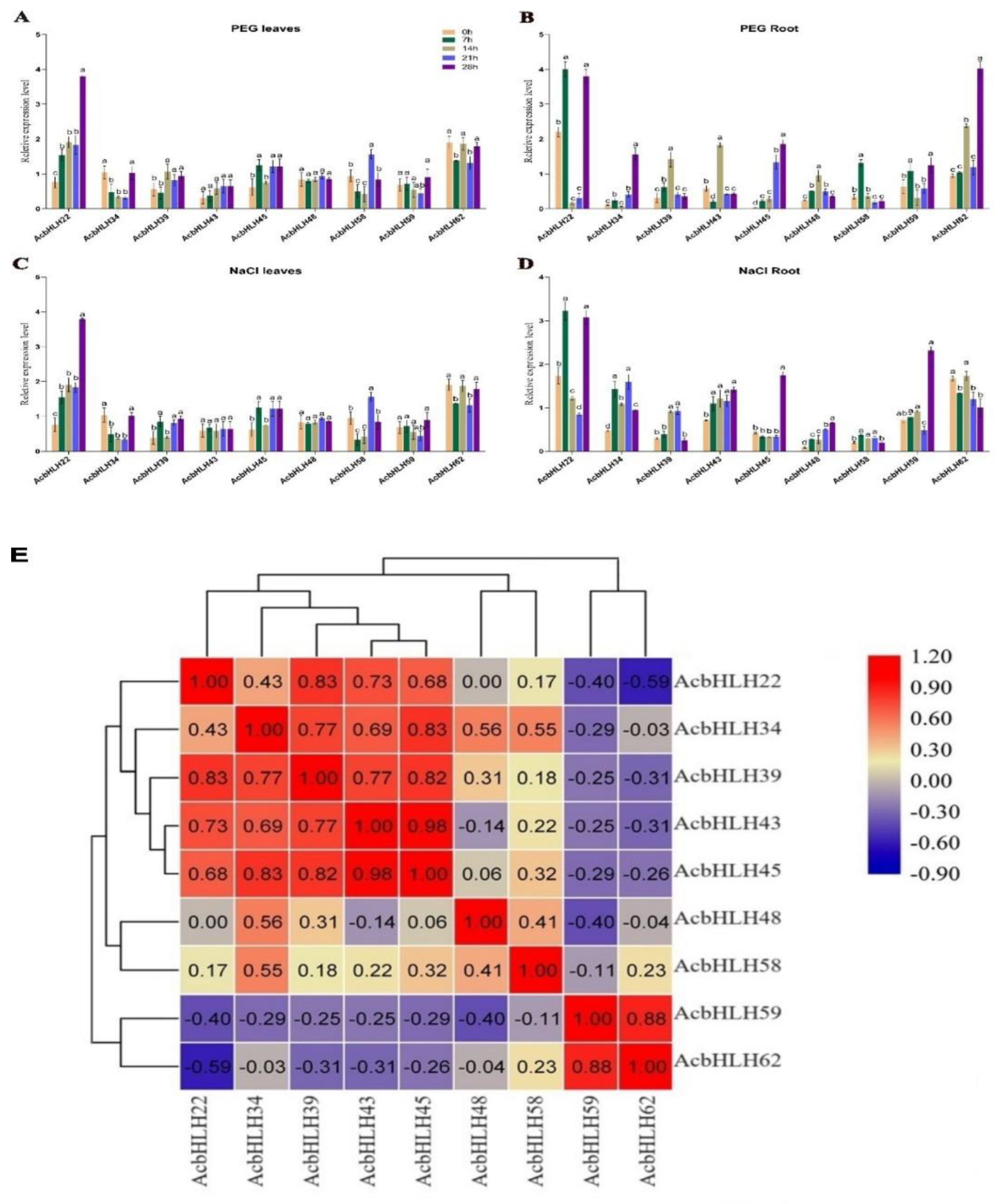

The basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor family, is the second-largest superfamily in plants after MYB, which plays a significant role in the physiological processes of plant growth, tissue development, and environmental variation. However, the systematized study of the bHLH transcription factor family has not yet been conducted in A. catechu. Herein, we conducted genome genome-wide investigation of AcbHLH genes located on 16 chromosomes of A. catechu. A phylogenic tree was constructed to adjudge their homology of genes, and 24 subgroups were identified. Finally, we analyzed the dynamic changes of gene-expression levels of nine AcbHLH genes in response to drought and salt in leaves and roots. The expression patterns of 9 AcbHLH genes show differences in leaves and roots. Under stress conditions induced by salt and drought, AcbHLH22, AcbHLH62 and AcbHLH45 are significantly upregulated in both leaves and roots. In conclusion, this study will substantially contribute to the foundation for exploring the role of the bHLH superfamily in A.catechu in dealing with abiotic stresses.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Identification of bHLH genes in A.catechu

2.2. Phylogenetic, Multiple Sequence Alignment, and classification of AcbHLH genes

2.3. Analysis of gene structure and conserved domains of AcbHLH genes

2.4. Characterization of cis-acting elements within AcbHLH promoter regions

2.5. Chromosomal distribution and gene duplication of AcbHLH genes

2.6. Analysis of gene duplication events of AcbHLH genes

2.7. Synteny analysis of AcbHLH genes

2.8. The expression patterns of AcbHLH genes differ across tissues

2.9. Effects of different treatments on AcbHLH expression

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Identification of AcbHLH genes in A. catechu

4.2. Analysis of Physicochemical Properties of AcbHLH

4.3. The bHLH Gene Structure, Conserved Motif and Cis-Acting Elements

4.4. Chromosomal distribution and gene duplication

4.5. Evolutionary Relationships and classification of AcbHLH gene family

4.6. RNA-seq data analysis

4.7. Plant materials, growth conditions, and abiotic stress in A. catechu

4.8. Total RNA extraction, cDNA and qRT-PCR

4.9. Statistical analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zhong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chai, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z. Comparative Genomics Analysis of BHLH Genes in Cucurbits Identifies a Novel Gene Regulating Cucurbitacin Biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhac038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Han, P.; Liu, H.; Gong, J.; Zhou, W.; Shi, B.; Liu, A.; Xu, L. Genome-Wide Investigation of BHLH Genes and Expression Analysis under Different Biotic and Abiotic Stresses in Helianthus Annuus L. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, X.; Vega-Léon, R.; Hugouvieux, V.; Blanc-Mathieu, R.; van Der Wal, F.; Lucas, J.; Silva, C. S.; Jourdain, A.; Muino, J. M.; Nanao, M. H. The Intervening Domain Is Required for DNA-Binding and Functional Identity of Plant MADS Transcription Factors. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, N.; Dolan, L. Origin and Diversification of Basic-Helix-Loop-Helix Proteins in Plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010, 27, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Liang, C.; Liu, F.; Hou, X.; Zou, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the BHLH Transcription Factor Family in Pepper (Capsicum Annuum L.). Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 570156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grove, C. A. A Multiparameter Network Reveals Extensive Divergence Between C. Elegans BHLH Transcription Factors: A Dissertation. 2009.

- Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Yao, S.; Li, L.; Huang, R.; Tan, Y.; Ming, R.; Huang, D. Genome-Wide Characterization of the BHLH Gene Family in Gynostemma Pentaphyllum Reveals Its Potential Role in the Regulation of Gypenoside Biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Mendenhall, J.; Huo, Y.; Lloyd, A. TTG1 Complex MYBs, MYB5 and TT2, Control Outer Seed Coat Differentiation. Dev. Biol. 2009, 325, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.; Ma, J.; Wang, S.; Tang, M.; Zhang, B.; Ma, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, G.; Dong, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, X.; Song, C.-P.; Huang, J. Liverwort BHLH Transcription Factors and the Origin of Stomata in Plants. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, 2806–2813e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Tao, R.; Feng, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, D.; Peng, Y.; Wen, X.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H. EIN3 and RSL4 Interfere with an MYB–BHLH–WD40 Complex to Mediate Ethylene-Induced Ectopic Root Hair Formation in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groszmann, M.; Paicu, T.; Alvarez, J. P.; Swain, S. M.; Smyth, D. R. SPATULA and ALCATRAZ, Are Partially Redundant, Functionally Diverging BHLH Genes Required for Arabidopsis Gynoecium and Fruit Development. Plant J. 2011, 68, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivar, P.; Monte, E.; Oka, Y.; Liu, T.; Carle, C.; Castillon, A.; Huq, E.; Quail, P. H. Multiple Phytochrome-Interacting BHLH Transcription Factors Repress Premature Seedling Photomorphogenesis in Darkness. Curr. Biol. 2008, 18, 1815–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Fang, Y.; An, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Wang, L.; Aslam, M.; Cheng, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zheng, P. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the BHLH Gene Family in Passion Fruit (Passiflora Edulis) and Its Response to Abiotic Stress. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Geng, L.; Lin, S.; Ouyang, L.; Jiang, X. RcbHLH59-RcPRs Module Enhances Salinity Stress Tolerance by Balancing Na+/K+ through Callose Deposition in Rose ( Rosa Chinensis ). Hortic. Res. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, L.; Wei, Z.; Zhai, H.; Xing, S.; Wang, Y.; He, S.; Gao, S.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q. The <scp>IbPYL8–IbbHLH66–IbbHLH118</Scp> Complex Mediates the Abscisic Acid-dependent Drought Response in Sweet Potato. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 2151–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Xiang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mao, D.; Luan, S.; Chen, L. BHLH57 Confers Chilling Tolerance and Grain Yield Improvement in Rice. Plant. Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1402–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. K.; Patra, B.; Paul, P.; Liu, Y.; Pattanaik, S.; Yuan, L. BHLH IRIDOID SYNTHESIS 3 Is a Member of a BHLH Gene Cluster Regulating Terpenoid Indole Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Catharanthus Roseus. Plant Direct 2021, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Cao, L.; Jiao, B.; Yang, H.; Ma, C.; Liang, Y. The BHLH Transcription Factor AcB2 Regulates Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Onion ( Allium Cepa L.). Hortic. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Maoz, I.; Gao, X.; Sun, M.; Yuan, T.; Li, K.; Zhou, W.; Guo, X.; Kai, G. SmbHLH60 and SmMYC2 Antagonistically Regulate Phenolic Acids and Anthocyanins Biosynthesis in Salvia Miltiorrhiza. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 42, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad; Hurrah, I. M.; Kumar, A.; Abbas, N. Synergistic Interaction of Two bHLH Transcription Factors Positively Regulates Artemisinin Biosynthetic Pathway in Artemisia Annua L. Physiol. Plant. 2023, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.; Zong, X.; Ren, P.; Qian, Y.; Fu, A. Basic Helix-Loop-Helix (BHLH) Transcription Factors Regulate a Wide Range of Functions in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Duan, X.; Jiang, H.; Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, J.; Liang, W.; Chen, L.; Yin, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D. Genome-Wide Analysis of Basic/Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor Family in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhao, T.; Yang, Y.; Chen, T.; Yang, M.; Yu, W.; Zhang, B. Genome-Wide Analysis of BHLH Transcription Factor and Involvement in the Infection by Yellow Leaf Curl Virus in Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum). BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lv, W.; Zhang, H.; Ma, L.; Li, P.; Ge, L.; Li, G. Genome-Wide Analysis of the Basic Helix-Loop-Helix (BHLH) Transcription Factor Family in Maize. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xiang, L.; Hong, J.; Xie, Z.; Li, B. Genome-Wide Analysis of BHLH Transcription Factor Family Reveals Their Involvement in Biotic and Abiotic Stress Responses in Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.). 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, S.; Yao, W.; Zhou, B.; Li, R.; Jiang, T. Characterization of the Basic Helix–Loop–Helix Gene Family and Its Tissue-Differential Expression in Response to Salt Stress in Poplar. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhao, P.; Kong, N.; Lu, R.; Pei, Y.; Huang, C.; Ma, H.; Chen, Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the Potato BHLH Transcription Factor Family. Genes (Basel). 2018, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Konovalov, D. A.; Fru, P.; Kapewangolo, P.; Peron, G.; Ksenija, M. S.; Cardoso, S. M.; Pereira, O. R.; Nigam, M.; Nicola, S. Areca Catechu—From Farm to Food and Biomedical Applications. Phyther. Res. 2020, 34, 2140–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Yin, H.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Yang, F.; He, C.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Y. The Genome of Areca Catechu Provides Insights into Sex Determination of Monoecious Plants. New Phytol. 2022, 236, 2327–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, C.; Yang, H.; Feng, L.; Chen, X.; Yang, Y.; Yao, X.; Weng, W.; Kong, L. BHLH Transcription Factor Family Identification, Phylogeny, and Its Response to Abiotic Stress in Chenopodium Quinoa. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1171518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Duan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.; Chen, S.; Yang, M.; Ding, Y.; Peng, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yang, H. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Profile Analysis of Trihelix Transcription Factor Family Genes in Response to Abiotic Stress in Sorghum [Sorghum Bicolor (L.) Moench]. BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Huq, E.; Quail, P. H. The Arabidopsis Basic/Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor Family. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1749–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Lai, D.; Yang, H.; Xue, G.; He, A.; Chen, L.; Feng, L.; Ruan, J.; Xiang, D.; Yan, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the BHLH Transcription Factor Family and Its Response to Abiotic Stress in Foxtail Millet (Setaria Italica L.). BMC Genomics 2021, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Jin, X.; Ma, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, M. Basic Helix–Loop–Helix (BHLH) Gene Family in Tartary Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Tataricum): Genome-Wide Identification, Phylogeny, Evolutionary Expansion and Expression Analyses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1478–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Fan, H.-J.; Ling, H.-Q. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the BHLH Gene Family in Tomato. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Hu, Y.; Vannozzi, A.; Wu, K.; Cai, H.; Qin, Y.; Mullis, A.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, L. The WRKY Transcription Factor Family in Model Plants and Crops. CRC. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2017, 36, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jia, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, L.; Li, M. Genome-Wide Identification of the DOF Gene Family Involved in Fruitlet Abscission in Areca Catechu L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.; Ma, H. Genome-Wide Characterization and Analysis of BHLH Transcription Factors Related to Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Fig (Ficus Carica L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 730692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Sun, J.; Wang, C.; Dong, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, X.; Jiao, Z. Genome-Wide Analysis of Basic/Helix-Loop-Helix Gene Family in Peanut and Assessment of Its Roles in Pod Development. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, J. R.; Huang, Z.; Xiang, X. Y.; Xu, W. X.; Wang, J. T.; Chen, J.; Song, L.; Xiao, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Cai, S. Z.; Sun, L. X.; Jiang, C. Z. MfbHLH38, a Myrothamnus Flabellifolia BHLH Transcription Factor, Confers Tolerance to Drought and Salinity Stresses in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, M. A.; Jakoby, M.; Werber, M.; Martin, C.; Weisshaar, B.; Bailey, P. C. The Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor Family in Plants: A Genome-Wide Study of Protein Structure and Functional Diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, A. M.; Swanson, W. J. The Importance of Gene Duplication and Domain Repeat Expansion for the Function and Evolution of Fertilization Proteins. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, G. A.; Hahn, M. W.; Abouheif, E.; Balhoff, J. P.; Pizer, M.; Rockman, M. V; Romano, L. A. The Evolution of Transcriptional Regulation in Eukaryotes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 1377–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavas, M.; Baloğlu, M. C.; Atabay, E. S.; Ziplar, U. T.; Daşgan, H. Y.; Ünver, T. Genome-Wide Characterization and Expression Analysis of Common Bean BHLH Transcription Factors in Response to Excess Salt Concentration. Mol. Genet. genomics 2016, 291, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Ma, Z.; Sun, W.; Huang, L.; Wu, Q.; Tang, Z.; Bu, T.; Li, C.; Chen, H. Genome-Wide Analysis of the NAC Transcription Factor Family in Tartary Buckwheat (Fagopyrum Tataricum). BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakashima, K.; Ito, Y.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Transcriptional Regulatory Networks in Response to Abiotic Stresses in Arabidopsis and Grasses. Plant Physiol. 2009, 149, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, B.; Deyholos, M. K. Functional Characterization of the Arabidopsis BHLH92 Transcription Factor in Abiotic Stress. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2009, 282, 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Tai, H.; Li, S.; Gao, W.; Zhao, M.; Xie, C.; Li, W. B HLH 122 Is Important for Drought and Osmotic Stress Resistance in A Rabidopsis and in the Repression of ABA Catabolism. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Gao, M.; Huang, L.; Wang, Y.; van Nocker, S.; Wan, R.; Guo, C.; Wang, X.; Gao, H. Identification and Expression Analysis of the Apple (Malus× Domestica) Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Transcription Factor Family. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, F.; Filiz, E. Genome-Wide and Comparative Analysis of BHLH38, BHLH39, BHLH100 and BHLH101 Genes in Arabidopsis, Tomato, Rice, Soybean and Maize: Insights into Iron (Fe) Homeostasis. BioMetals 2018, 31, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Feng, R.; Ma, R.; Shen, Z.; Cai, Z.; Song, Z.; Peng, B.; Yu, M. Genome-Wide Analysis of Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Superfamily Members in Peach. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, H.; Liu, H.; Ai, W.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, X. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of the BHLH Transcription Factor Family and Its Response to Abiotic Stress in Mongolian Oak (Quercus Mongolica). Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 1127–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. 20 Years of the SMART Protein Domain Annotation Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D493–D496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; He, Y. Genome-Wide Investigation of WRKY Gene Family in Pineapple: Evolution and Expression Profiles during Development and Stress. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J. D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H. MCScanX: A Toolkit for Detection and Evolutionary Analysis of Gene Synteny and Collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar Reddy, P.; Srinivas Reddy, D.; Sivasakthi, K.; Bhatnagar-Mathur, P.; Vadez, V.; Sharma, K. K. Evaluation of Sorghum [Sorghum Bicolor (L.)] Reference Genes in Various Tissues and under Abiotic Stress Conditions for Quantitative Real-Time PCR Data Normalization. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).