Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

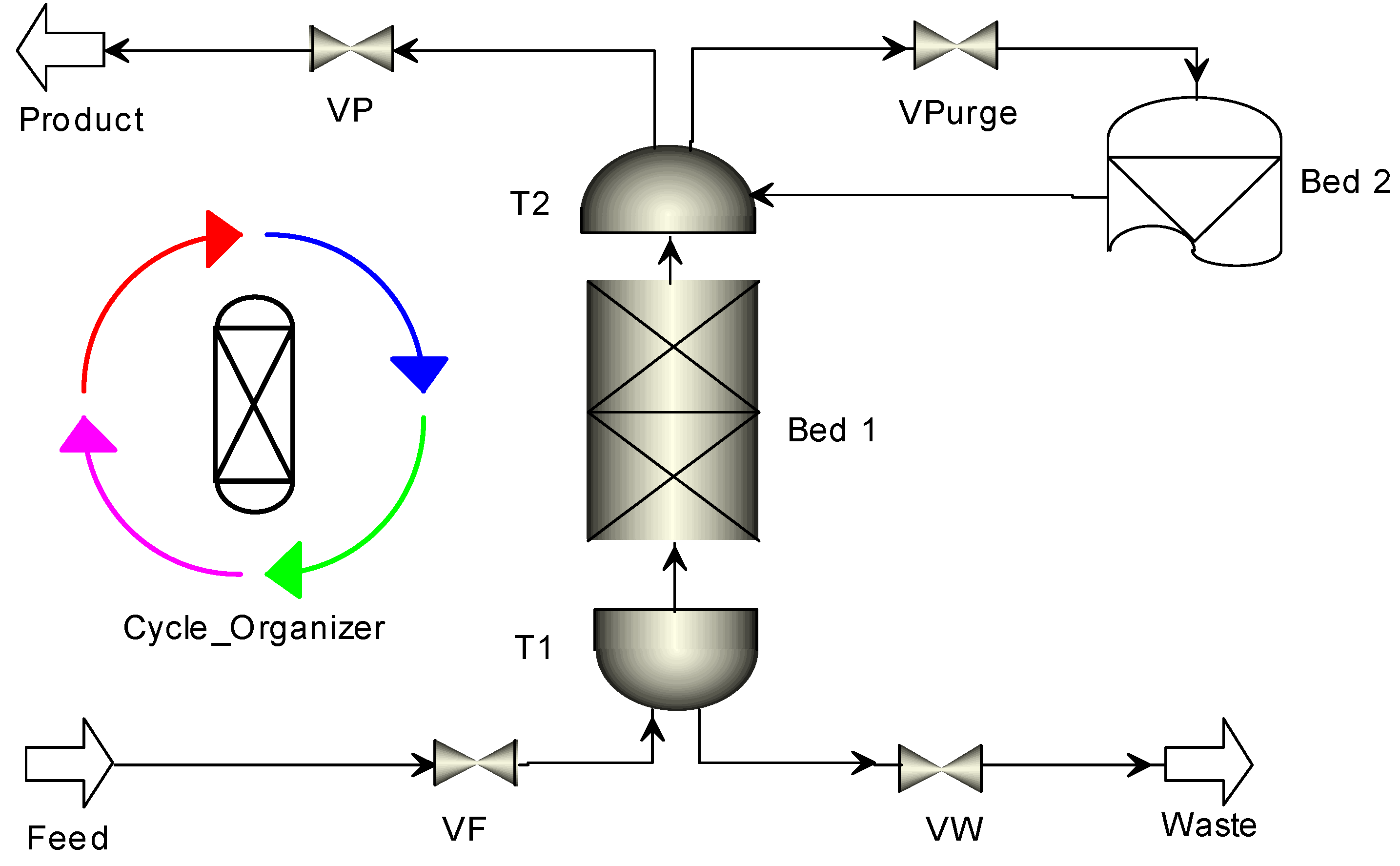

2.1. Mathematical Model for PSA Process

2.2. BBD Method for PSA Process

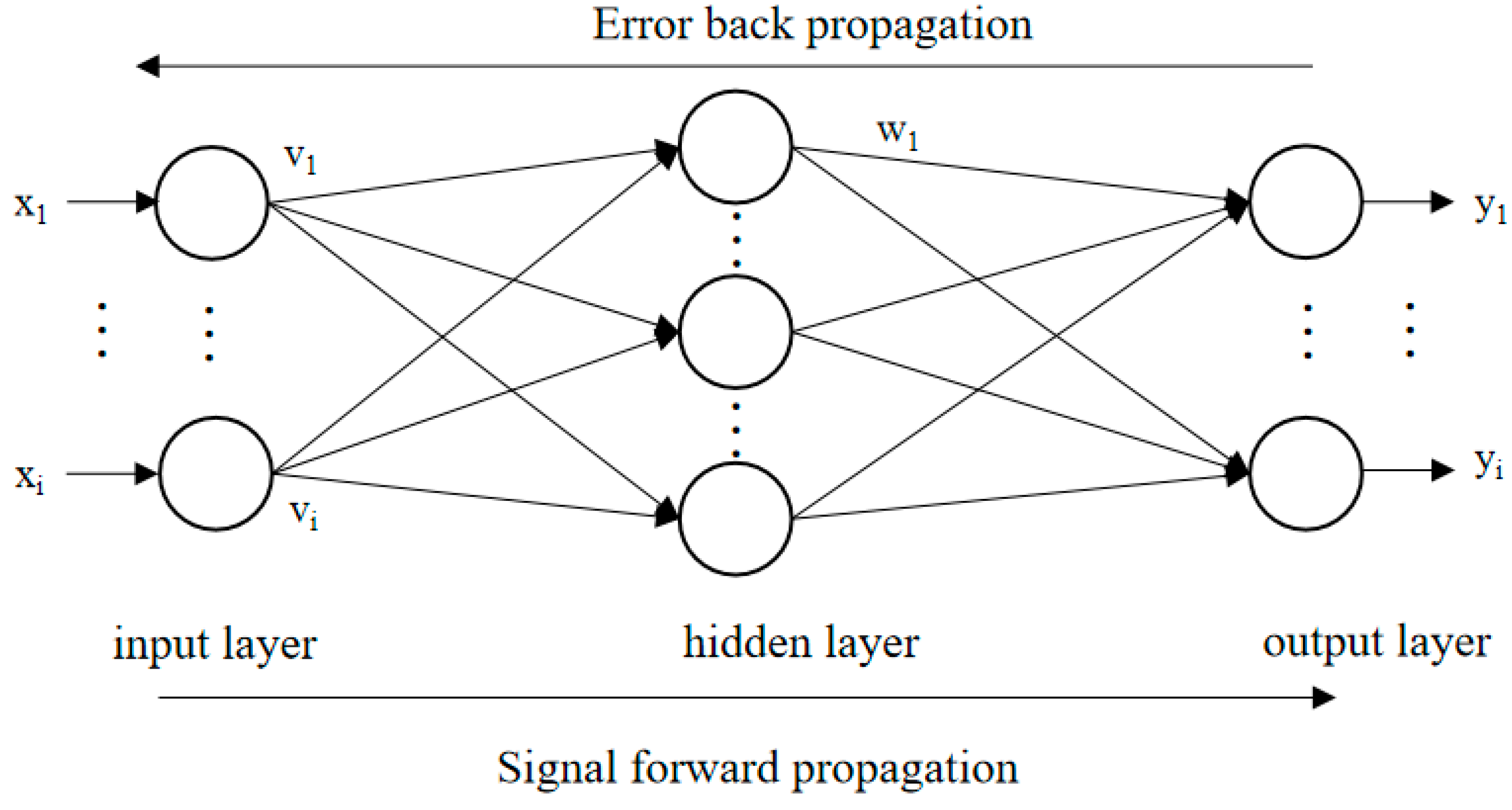

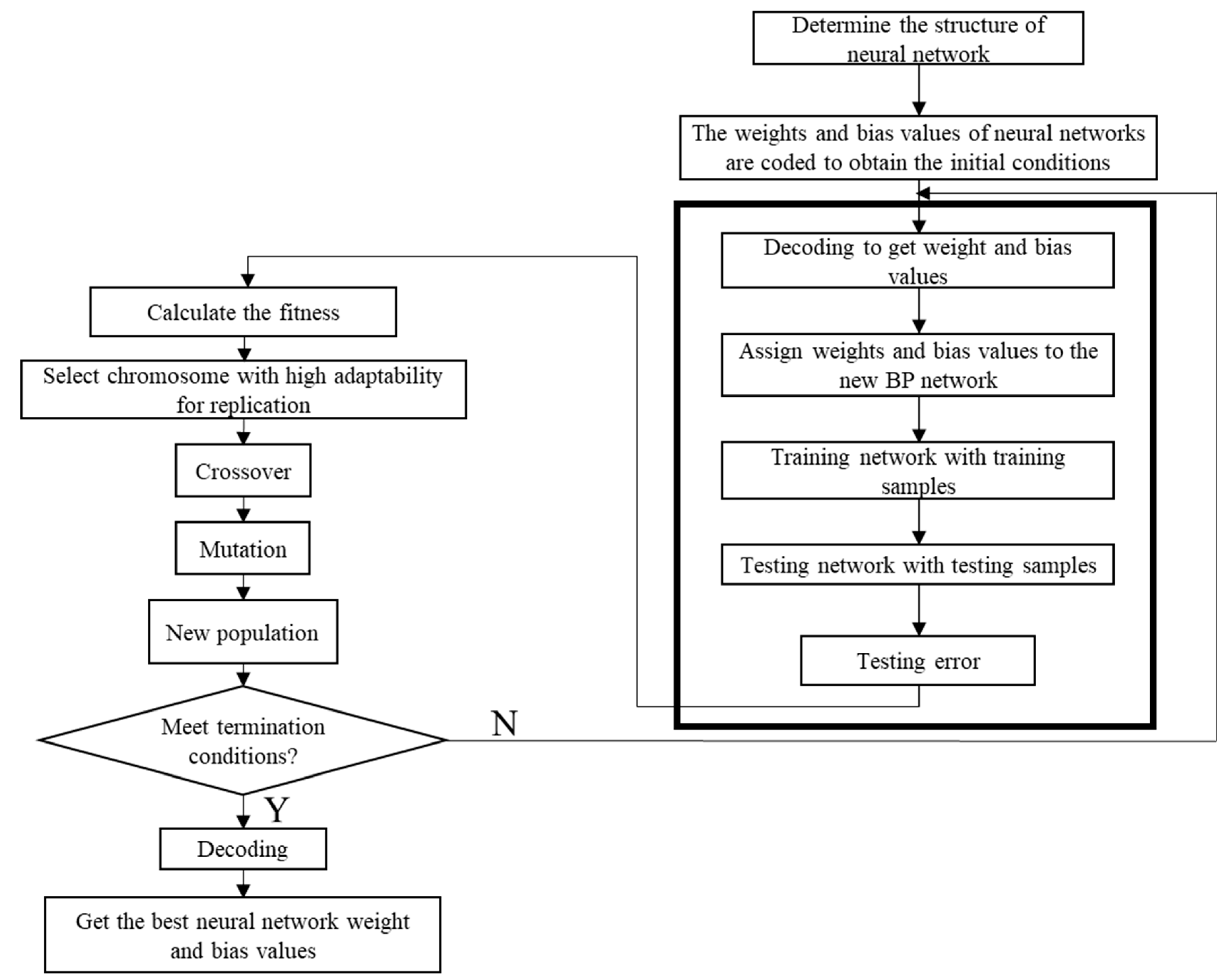

2.3. BPNN-GA for Optimization

3. Results

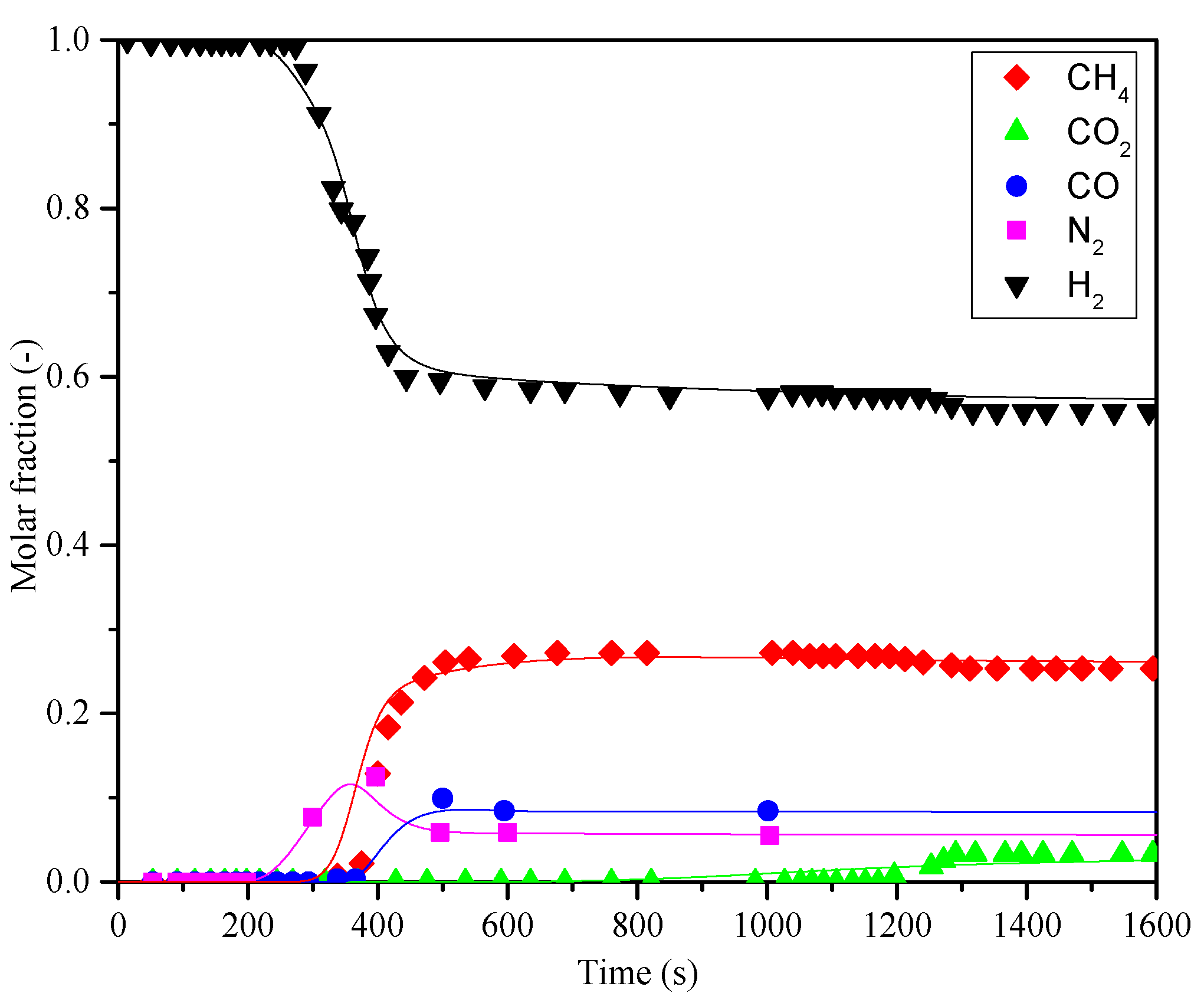

3.1. Subsection

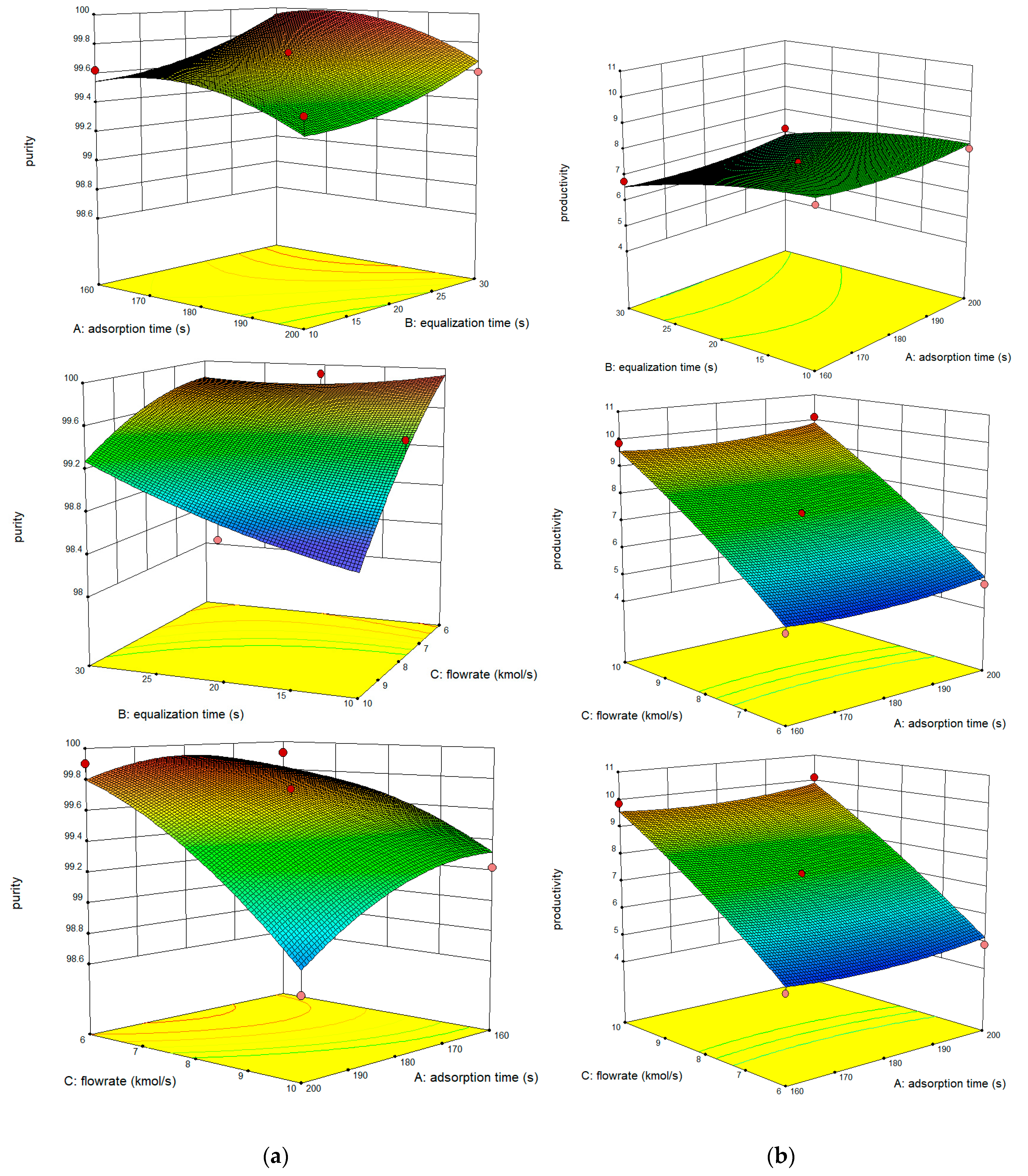

3.2. Prediction by BBD Method

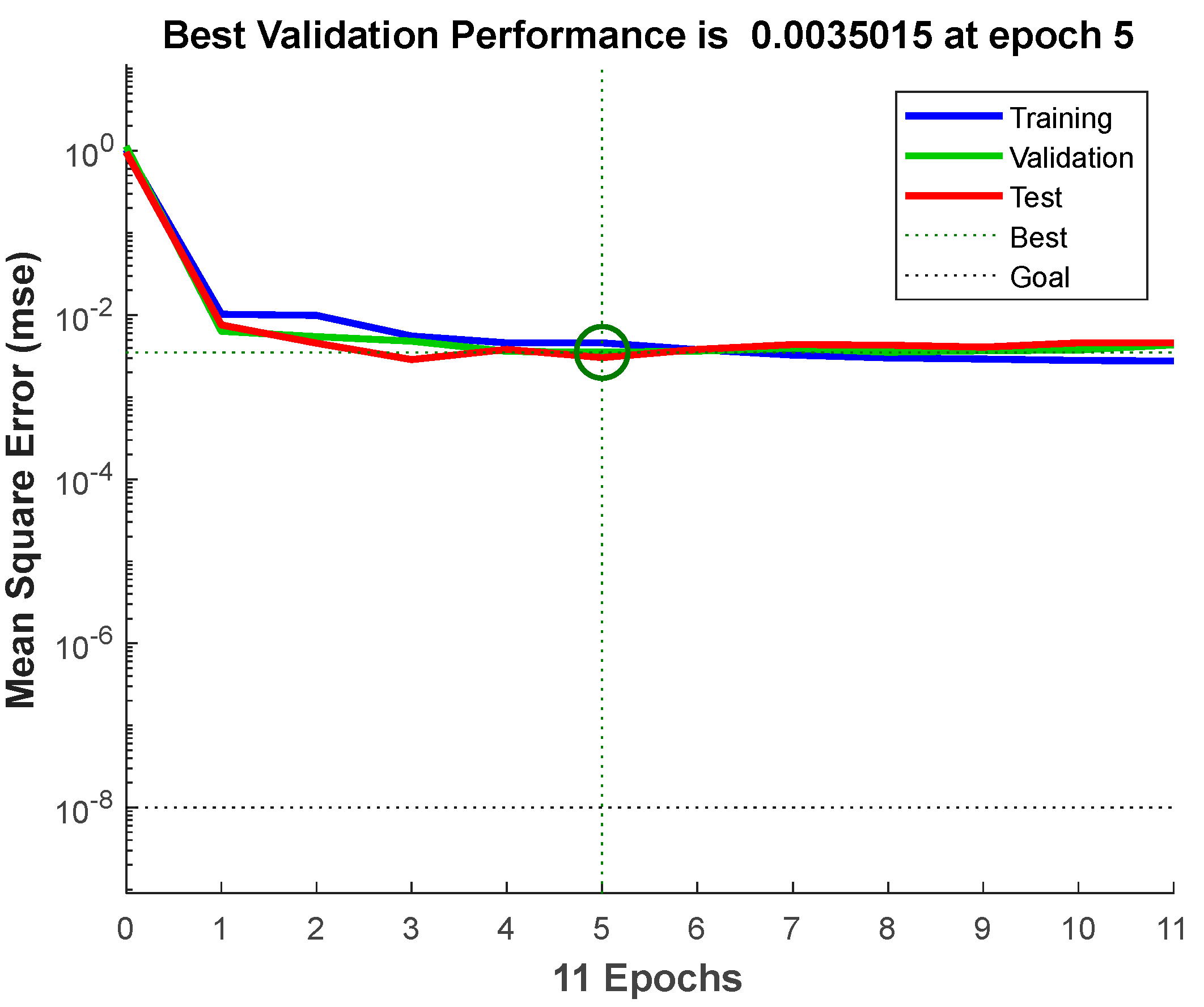

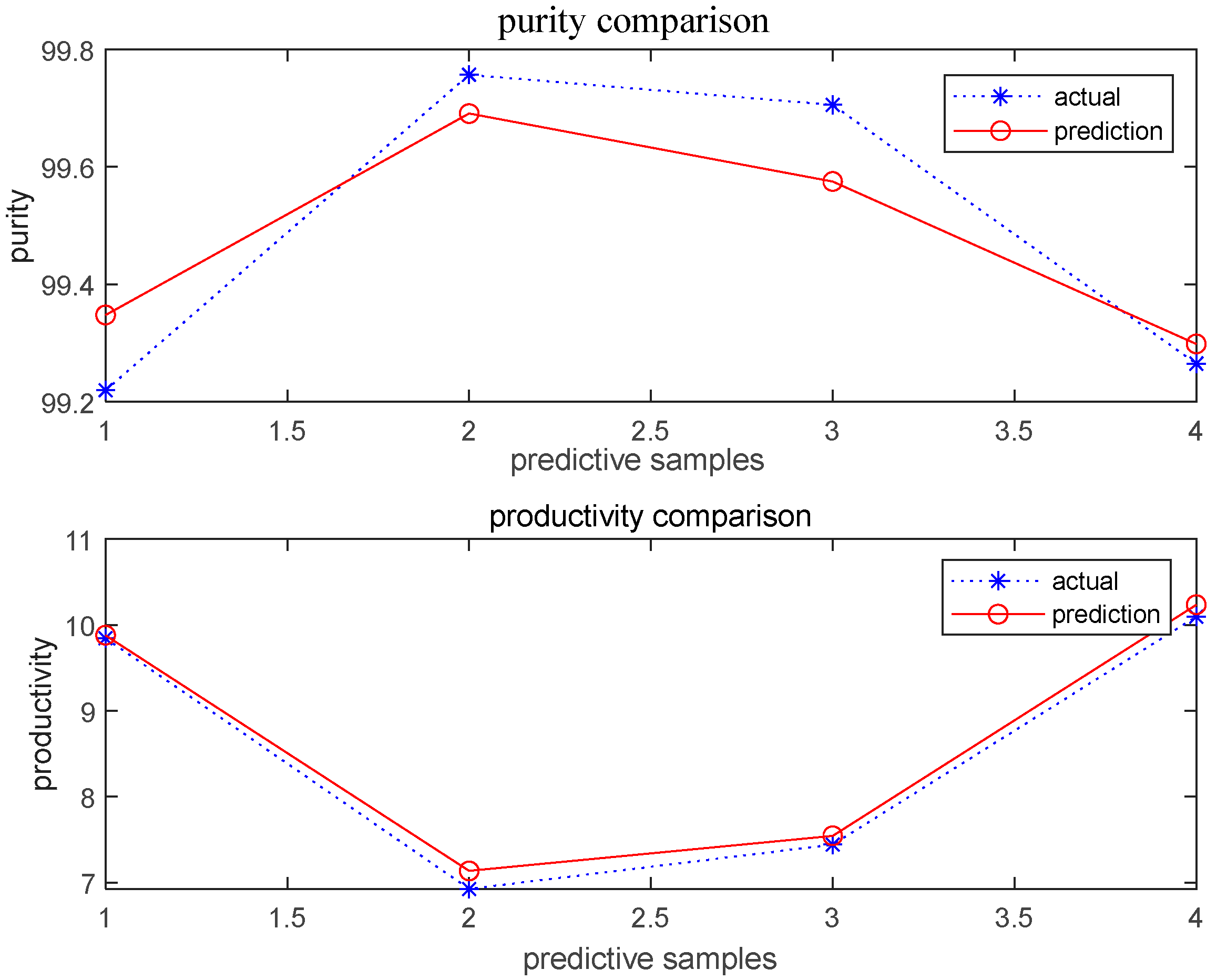

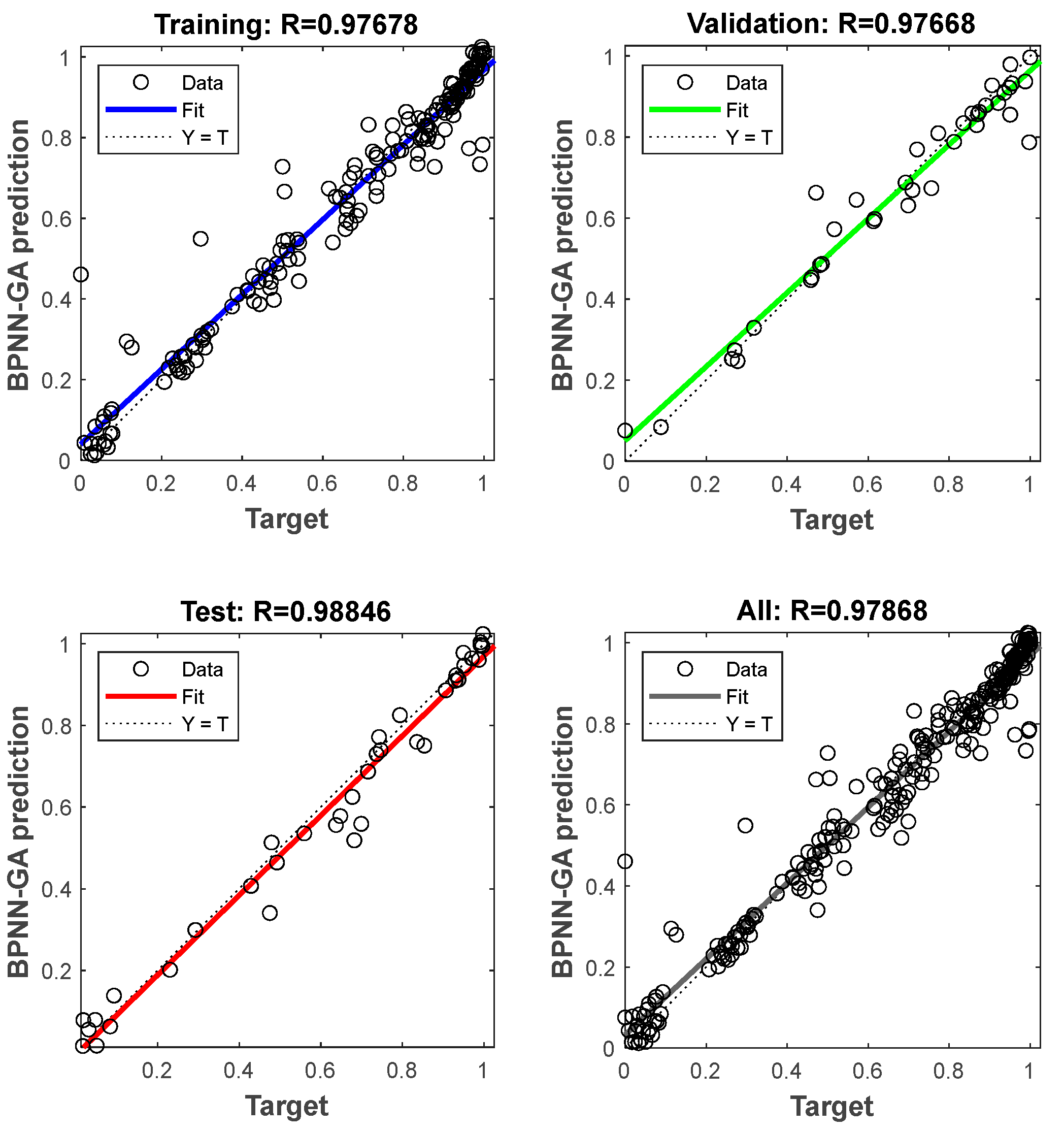

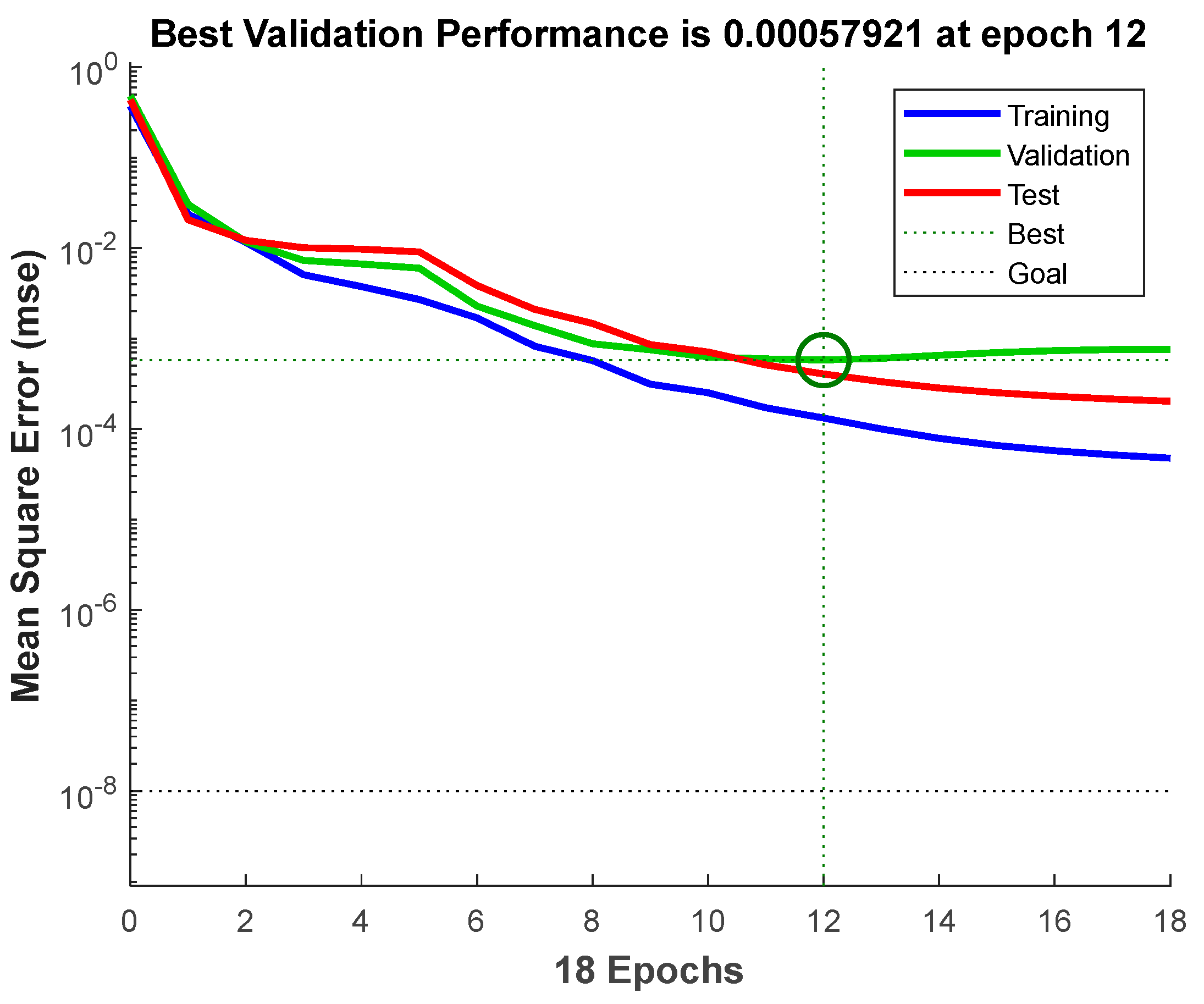

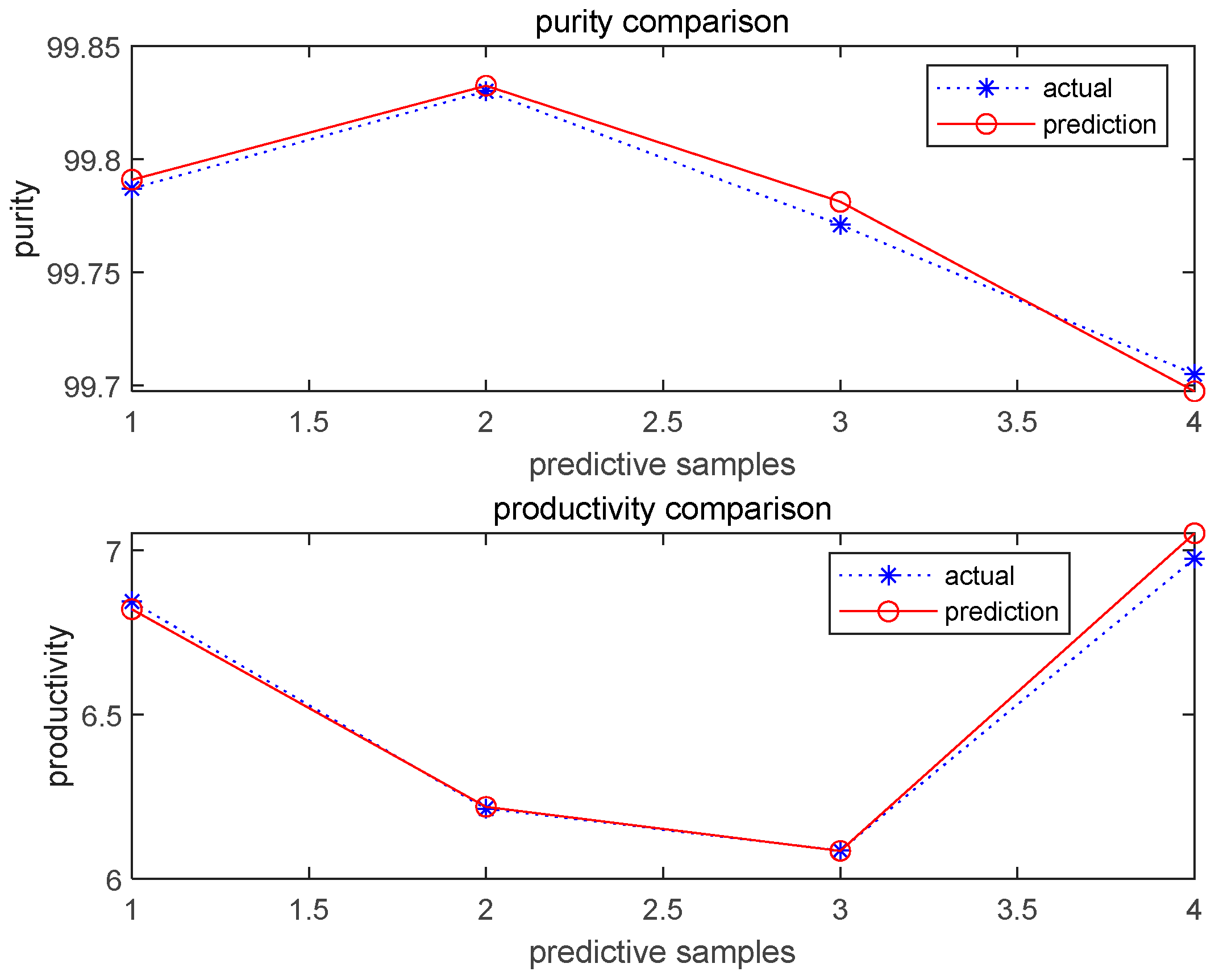

3.3. Prediction by BPNN-GA Model

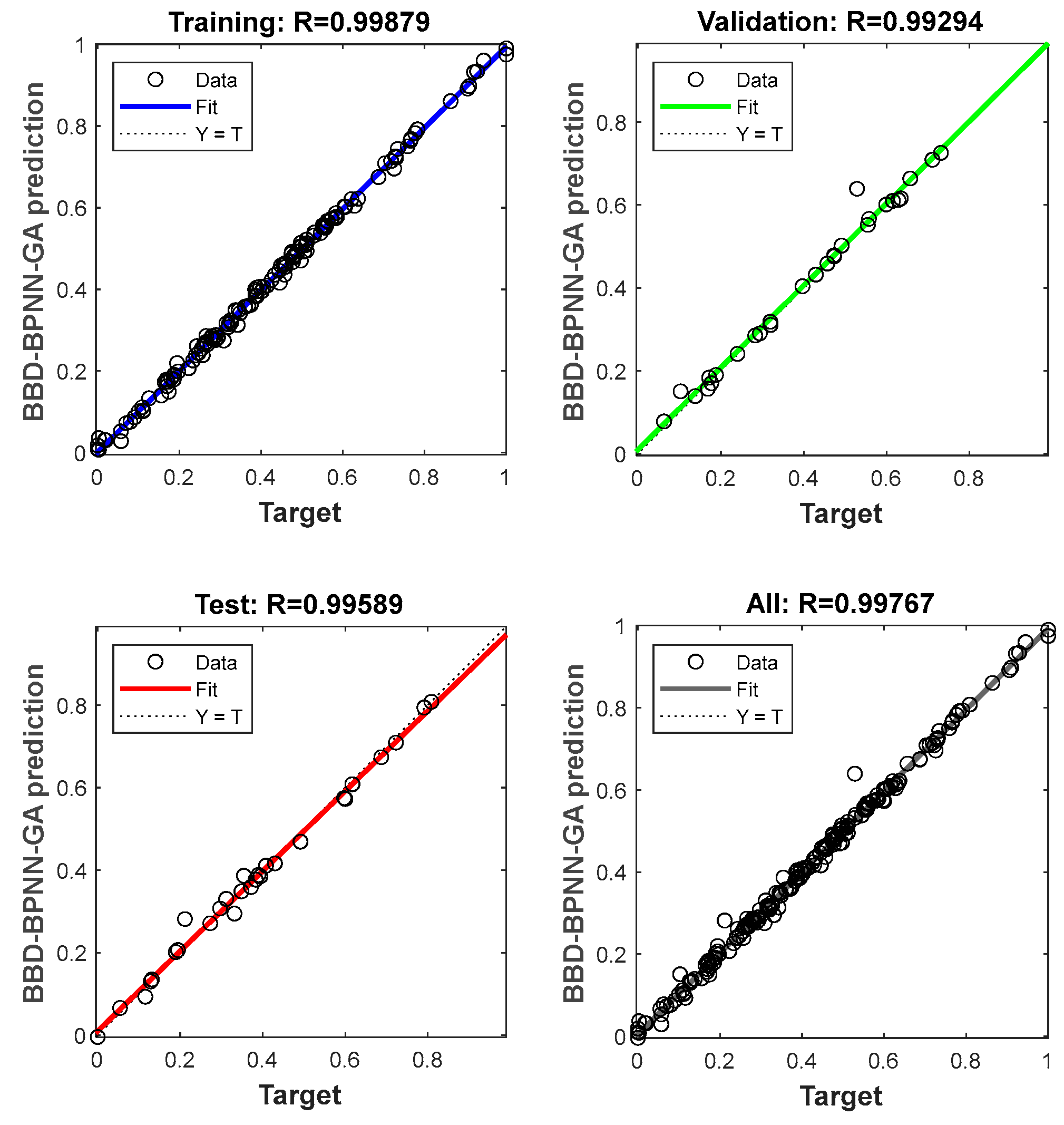

3.4. Rediction by BBD-BPNN-GA Model

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| cross-section area of column wall, m2 | |

| Langmuir isotherm parameter, 1/atm | |

| heat capacity of gas phase, J/(mol•K) | |

| specific heat capacity of adsorbent, J/(kg•K) | |

| specific heat capacity of column wall, J/(kg•K) | |

| axial dispersion coefficient, s/m2 | |

| heat transfer coefficient with inner wall of column, W/(m2•K) | |

| heat transfer coefficient with outer wall of column, W/(m2•K) | |

| axial thermal dispersion coefficient, W/(m•K) | |

| pressure, atm | |

| equilibrium adsorption amount, mol/kg | |

| dynamic adsorption amount of component , mol/kg | |

| saturation adsorption amount for each component, mol/kg | |

| average isosteric heat of adsorption, cal/mol | |

| universal gas constant, 8.314 J/(mol•K) | |

| bed inside radius, m | |

| bed outside radius, m | |

| particle radius, m | |

| time, s | |

| temperature of adsorption bed, K | |

| atmosphere temperature, K | |

| wall temperature, K | |

| axial physical velocity, m/s | |

| axial Darcy’s velocity, m/s | |

| mass transfer coefficient of component , 1/s | |

| molar fraction of component in the gas phase | |

| axial position in the bed, m | |

| Greek Symbols | |

| interparticle void fraction | |

| total void fraction | |

| dynamic viscosity, m/kg/s | |

| adsorption bed density, kg/m3 | |

| gas phase density, kg/m3 | |

| pellet density, kg/m3 | |

| wall density, kg/m3 |

References

- Xie, X.Y.; Awad, O.I.; Xie, L.L.; Ge, Z.Y. Purification of hydrogen as green energy with pressure-vacuum swing adsorption (PVSA) with a two-layers adsorption bed using activated carbon and zeolite as adsorbent. Chemosphere 2023, 338, 139347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golmakani, A.; Fatemi, S.; Tamnanloo, J. Investigating PSA, VSA, and TSA methods in SMR unit of refineries for hydrogen production with fuel cell specification. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 176, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Muthukumar, P. Experimental investigation on hydrogen transfer in coupled metal hydride reactors for multistage hydrogen purification application. Appl. Energ. 2024, 363, 123076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achomo, M.A.; Kumar, A.; Muthukumar, P.; Peela, N.R. Experimental studies on hydrogen production from steam reforming of methanol integrated with metal hydride-based hydrogen purification system. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.T.; Yang, D.F.; Guan, M.J.; Li, Q. Study of supramolecular organic frameworks for purification of hydrogen through molecular dynamics simulations. Sep. Purif. Technol, 1261. [Google Scholar]

- Ganley, J. Pressure swing adsorption in the unit operations laboratory. Chem. Eng. Educ. 2018, 52, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrun, M.H.V.; Bono, A.; Othman, N.; Zaini, M.A.A. Carbon dioxide removal from biogas through pressure swing adsorption - A review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 183, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, A.A.; Othman, M.R.; Helwani, Z.; Kim, J. An overview of biogas upgrading via pressure swing adsorption: Navigating through bibliometric insights towards a conceptual framework and future research pathways. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2024, 306, 118268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, D.; Güngör, A.; Atakan, B. Hydrogen production and separation in fuel-rich operated HCCI engine polygeneration systems: Exergoeconomic analysis and comparison between pressure swing adsorption and palladium membrane separation. Appl. Energy Combust. Sci. 2023, 13, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Bao, C.; Zhou, F. Modeling study on a two-stage hydrogen purification process of pressure swing adsorption and carbon monoxide selective methanation for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2023, 64, 25171–25184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.T.; Lu, J.B.; Abed, A.N.; Nag, K. Simulation of CO2 capture from natural gas by cyclic pressure swing adsorption process using activated carbon. Chemosphere 2023, 329, 138583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, I.C.C.; Pinheiro, L.S.; Gonalves, D.V. Multiscale design of a pressure swing adsorption process for natural gas purification. Adsorption 2021, 27, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, Y.; Habib, E.; Falamaki, C. Competitive adsorption equilibrium isotherms of CO, CO2, CH4, and H2 on activated carbon and zeolite 5A for hydrogen purification. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 61, 3420–3427. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, F.V.S.; Grande, C.A.; Ribeiro, A.M. Adsorption of H2, CO2, CH4, CO, N2 and H2O in activated carbon and zeolite for hydrogen production. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 44, 1045–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, F.V.S.; Grande, C.A.; Rodrigues, A.E. Activated carbon for hydrogen purification by pressure swing adsorption: Multicomponent breakthrough curves and PSA performance. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Grande, C.A.; Lopes, F.V.S. Four beds pressure swing adsorption for hydrogen purification: Case of humid feed and activated carbon beds. AIChE 2009, 55, 2292–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacem, M.; Pellerano, M.; Delebarre, A. Pressure swing adsorption for CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4 separation: Comparison between activated carbons and zeolites performances. Fuel Process Technol. 2015, 138, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N.; Xiao, J.S.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R. Single-and double-bed pressure swing adsorption processes for H2/CO syngas separation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2019, 44, 26405–26418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.M.; Grande, C.A.; Lopes, F.V.S.; Loureiro, J.M. A parametric study of layered bed PSA for hydrogen purification. Chem. Eng. Sc. 2008, 63, 5258–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, N.; Schell, J.; Marx, D.; Mazzotti, M. A parametric study of a PSA process for pre-combustion CO2 capture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 104, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.R.; Lee, J.M. Multi-objective optimization of hydrogen production process and steam reforming reactor design. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2023, 48, 29928–29941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, C.M.; Martins, M.A.F.; Rodrigues, A.E.; Loureiro, J.M. A novel standpoint of pressure swing adsorption processes multi-objective optimization: An approach based on feasible operation region mapping. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 178, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subraveti, S.G.; Pai, K.N.; Rajagopalan, A.K.; Wilkins, N.S. Cycle design and optimization of pressure swing adsorption cycles for pre-combustion CO2 capture. Appl. Energ. 2019, 254, 113624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararao, B.; Gupta, S.K. Multiobjective optimization of the dynamic operation of an industrial steam reformer using the jumping gene adaptations of simulated annealing. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2006, 1, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararao, B.; Gupta, S.K. Multi-Objective Optimization of pressure swing adsorbers for air separation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 3751–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankararao, B.; Yoo, C.K. Development of a robust multi-objective simulated annealing algorithm for solving multi-objective optimization problems. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 6728–6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uebbing, J.; Biegler, L.T.; Struckmann, L.R.; Sager, S.; Sundmacher, K. Optimization of pressure swing adsorption via a trust-region filter algorithm and equilibrium theory. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2021, 151, 107340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Zheng, M.Y.; Liu, G.L.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Q. Graphical method for simultaneous optimization of the hydrogen recovery and purification feed. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2016, 41, 2631–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.Y.; Cheng, A.D.; Wu, X.M.; Ruan, X.H. Optimization of the hydrogen production process coupled with membrane separation and steam reforming from coke oven gas using the response surface methodology. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2023, 48, 26238–26250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.Y.; Long, W.Q.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, G.; Wang, Y.J.; Lu, M.F. Multi-objective optimization of methanol reforming reactor performance based on response surface methodology and multi-objective particle swarm optimization coupling algorithm for on-line hydrogen production. Energ. Convers. Manag. 2024, 307, 118377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kombe, E.Y.; Lang, N.; Njogu, P.; Malessa, R. Process modeling and evaluation of optimal operating conditions for production of hydrogen-rich syngas from air gasification of rice husks using aspen plus and response surface methodology. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.N.; Bénard, P.; Chahine, R.; Yang, T.Q.; Xiao, J.S. Optimization of pressure swing adsorption for hydrogen purification based on Box-Behnken design method. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2021, 46, 5403–5417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, F.; Arshad, M.Y.; Saeed, M.A.; Ali, U. Integrated process for simulation of gasification and chemical looping hydrogen production using Artificial Neural Network and machine learning validation. Energ. Convers. Man. 2023, 296, 117702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.X.; Shen, Y.H.; Guan, Z.B.; Zhang, D.H.; Tang, Z.L.; Li, W.B. Multi-objective optimization of ANN-based PSA model for hydrogen purification from steam-methane reforming gas. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2021, 46, 11740–11755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, C.M.; Nogueira, I.B.R. Optimizing CO2 capture in pressure swing adsorption units: A deep neural network approach with optimality evaluation and operating maps for decision-making. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streb, A.; Mazzotti, M. Performance limits of neural networks for optimizing an adsorption process for hydrogen purification and CO2 capture. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2022, 166, 107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kani, G.T.; Ghahremani, A. Optimal design of heat pipes for city gate station heaters by applying genetic and Bayesian optimization algorithms to an artificial neural network model. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 55, 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Ahmad, I.; Kano, M.; Caliskan, H. Prediction and optimization of exergetic efficiency of reactive units of a petroleum refinery under uncertainty through artificial neural network-based surrogate modeling. Process Saf. Environ. 2023, 177, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Silva, J.; Rodrigues, A. A General Package for the Simulation of Cyclic Adsorption Processes. Adsorption 1999, 5, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereno, C.; Rodrigues, A. Can steady-state momentum equations be used in modeling pressurization of adsorption beds? Gas. Sep. Purif. 1993, 7, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Aghilesh, K.; Nair, A.; Ram, S. Response surface methodology and artificial neural network modelling for the performance evaluation of pilot-scale hybrid nanofiltration (NF) & reverse osmosis (RO) membrane system for the treatment of brackish ground water. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 278, 111497. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Lee, C.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.H. Optimization of photocatalytic ceramic membrane filtration by response surface methodology: Effects of hydrodynamic conditions on organic fouling and removal efficiency. Chemosphere 2024, 356, 141885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jee, J.G.; Kim, M.B.; Lee, C.H. Adsorption characteristics of hydrogen mixtures in a layered bed: binary, ternary, and five-component mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 868–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, C.H. Adsorption dynamics of a layered bed PSA for H2 recovery from coke oven gas. AIChE 2010, 44, 1325–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; You, Y.W.; Lee, D.G. Layered two- and four-bed PSA processes for H2 recovery from coal gas. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 68, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.; Yang, J.; Lee, C.H. Effects of feed composition of coke oven gas on a layered bed H2 PSA process. Adsorption 2001, 7, 339–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

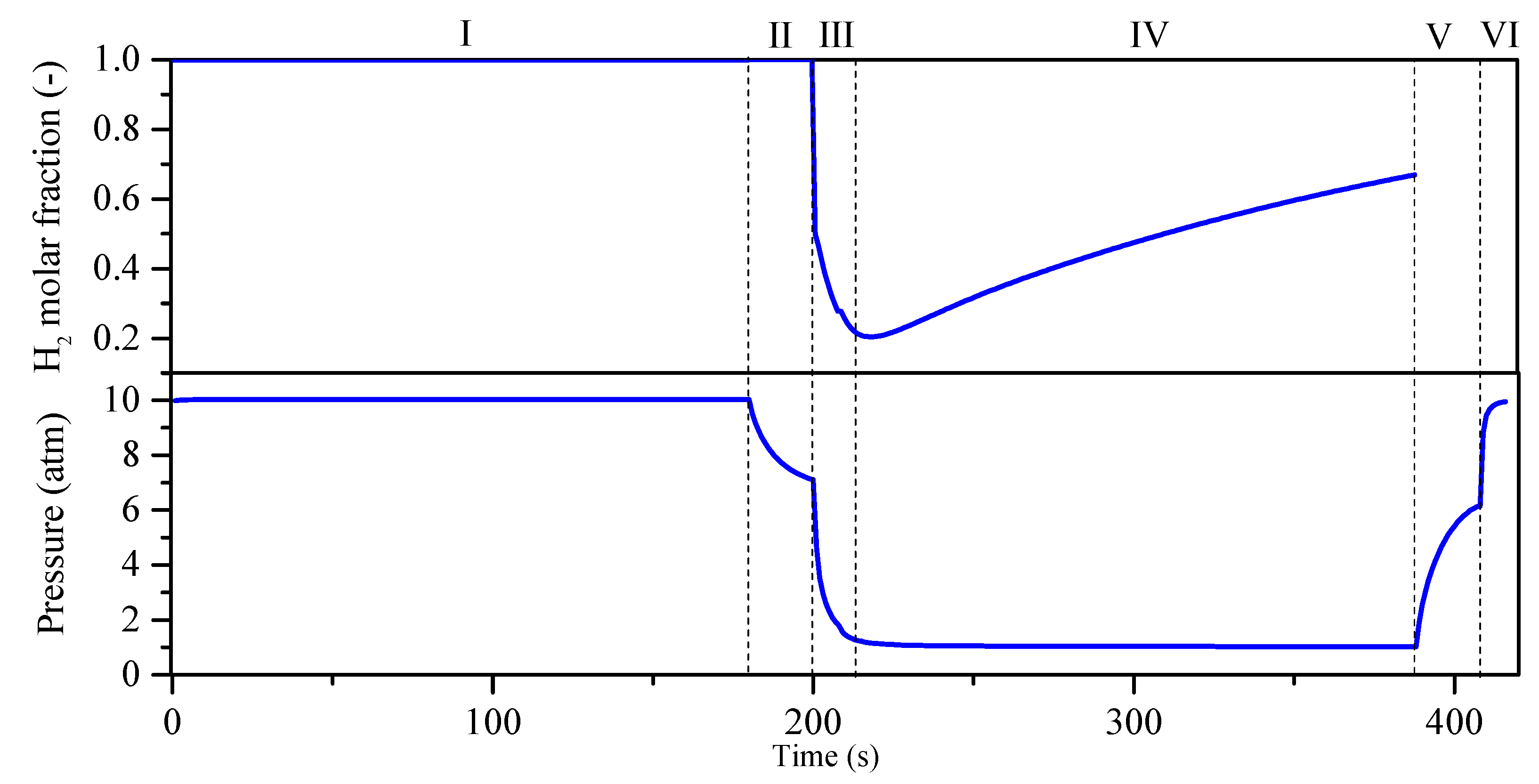

| Step | Ⅰ | Ⅱ | Ⅲ | Ⅳ | Ⅴ | Ⅵ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Bed 1 | AD | DPE | DP | PG | PPE | FP |

| Bed 2 | PG | PPE | FP | AD | DPE | DP |

| Time (s) | 180 | 20 | 8 | 180 | 20 | 8 |

| Factors | Variables and Ranges | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption Time (s) | Pressure Equalization Time (s) | Feed Flow Rate (L/min) | |

| -1 | 160 | 10 | 6 |

| 0 | 180 | 20 | 8 |

| +1 | 200 | 30 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).