1. Introduction

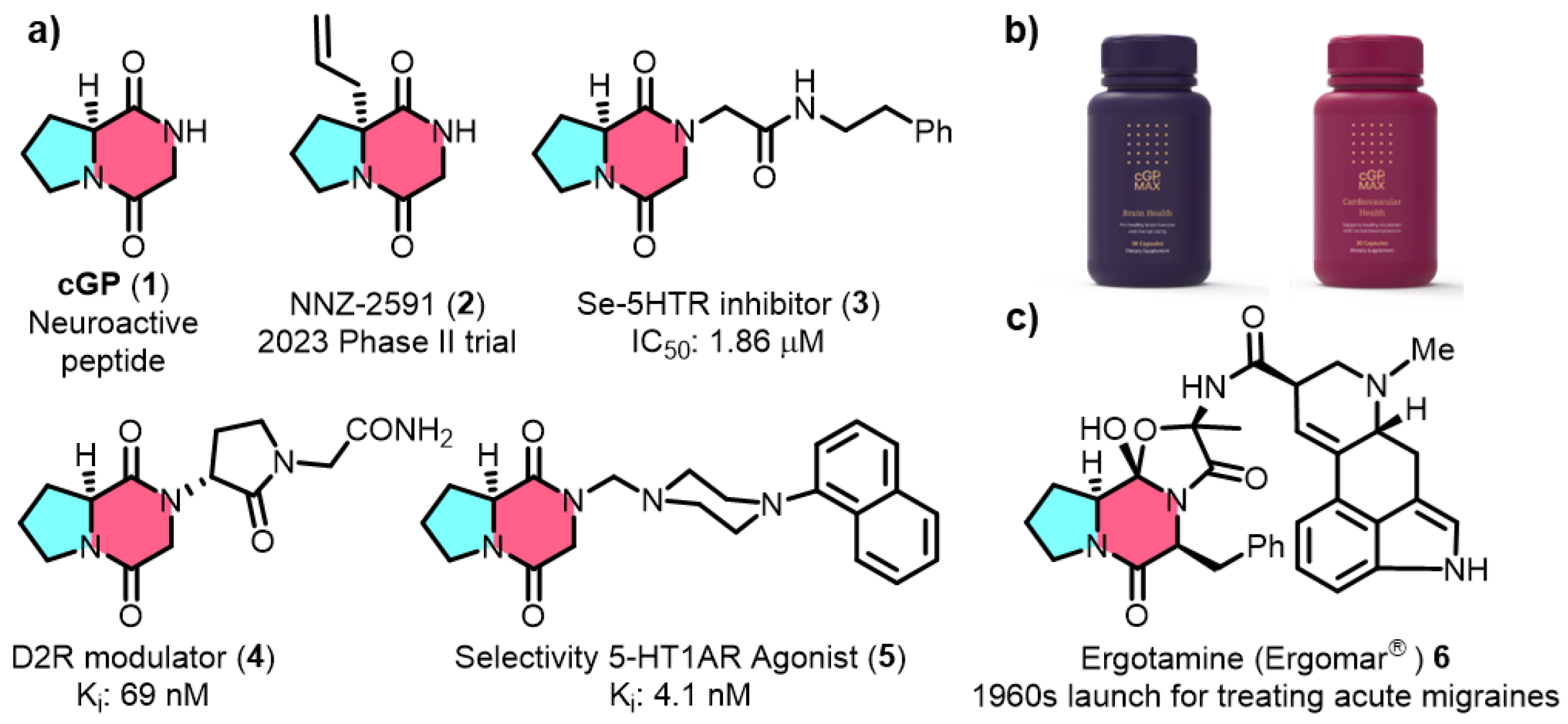

Cyclic glycine-proline (cGP, 1,

Figure 1) is a widely studied marine-derived cyclic peptide characterized by a conformationally constrained diketopiperazine (DKP) core. [

1,

2] Known for its neuroprotective properties, cGP has shown great potential for therapeutic applications, particularly in treating neurological disorders by modulating insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) homeostasis. [

3] The pharmaceutical promise of cGP is further exemplified by its inclusion in drug candidates like NNZ-2591 (2,

Figure 1a), which is currently in Phase II clinical trials for treating Prader-Willi syndrome and Angelman syndrome, underscoring its importance in modern drug development. [

4] In addition, cGP is utilized in nutraceutical products such as cGPMAX™ for cognitive and cardiovascular health in older adults (

Figure 1b). [

5] Beyond its role in IGF-1 regulation, cGP is a valuable building block for preclinical drug candidates (

Figure 1c, 3-5) with a wide range of biological activities and is structurally incorporated into the clinical acute migraine medication ergotamine (Ergomar®). [

6,

7,

8,

9] Compound 3, built on the cGP scaffold, enhances serotonin receptor inhibition with an IC50 of 1.86 µM—two orders of magnitude better than the prototype. Other cGP-derived molecules, such as the D2R modulator (4) and CSP-2503 (5), demonstrate strong bioactivity, further establishing cGP as a key component in drug discovery.

The biosynthesis of cGP via biological processes is still a vital area of interest despite the development of synthetic methods for cGP and their compounds. [

10,

11] Despite promising bio-enzymatic production using engineered

Escherichia coli, strong biosynthesis from amino acids like protein and glutamine continues to face major difficulties in terms of protein relationship development and selectivity. [

12,

13,

14] This has spurred research into natural metabolic processes, particularly in marine fungi, which exhibit special physiological abilities in harsh conditions. [

15,

16]

Mangrove-derived fungi, such as

Penicillium and

Aspergillus species, have emerged as promising sources of cGP due to their rich secondary metabolite production under marine conditions. [

17] These fungi offer a sustainable and possibly high-yield alternative for cyclic peptide production. However, to harness their full capacity, efficient screening of wild strains is necessary to facilitate gene cluster mining and identify biosynthetic pathways that can be optimized for industrial applications. [

18]

Advanced analytical techniques such as Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) have become essential to support this exploration. [

19] High-resolution mass spectrometry method provides the specificity, sensitivity, and precision needed to quantify small molecules in complex mixtures. [

20,

21,

22] By using a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer offer superior mass accuracy, resolution, and ease of data acquisition compared to traditional HPLC, making them indispensable tools in metabolomics and natural product discovery.

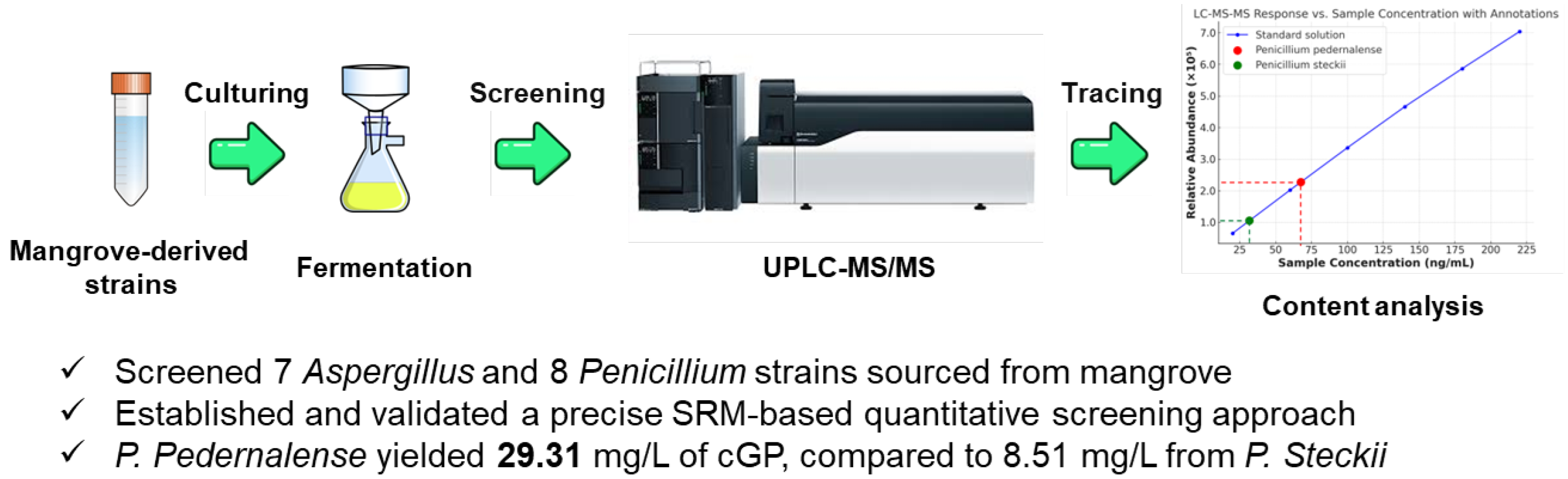

In this study, we aim to develop a robust UPLC-MS/MS method utilizing a SRM method to quantify cGP in fungal fermentation extracts. This approach will be applied to Penicillium and Aspergillus strains to assess their biosynthetic capacity, offering new insights into sustainable cGP production and laying the foundation for upcoming biology and drug development applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Marine-derived fungal strains, including species of Penicillium and Aspergillus, were obtained from the low-temperature (−20 °C) strain storage of the Xiamen Key Laboratory of Marine Natural Product Resources, Xiamen Medical College, China. Cyclic glycine-proline (≥98% purity) was purchased from Bide Pharmatech Co. Ltd. Analytical grade chemicals such as methanol and ethyl acetate were used throughout the study.

2.2. Fungal Strain Culture and Fermentation, and Sample Preparation

A total of 15 fungal strains, were utilized in this study. The strains were initially activated on sterilized Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and then sealed and incubated at 28 °C for 4 days. Once the spores had matured, approximately 1 cm³ of the culture was transferred to a 1 L Erlenmeyer flask containing 500 mL of sterilized PDB (Potato Dextrose Broth) liquid medium, among them, a blank control of PDB medium was set up as a reference. The cultures were then incubated at 28 °C with shaking at 180 rpm for 7 days.

Following incubation, the fungal mycelium was separated from the culture broth and extracted three times with 200 mL of ethyl acetate. The combined organic phases were concentrated under reduced pressure, yielding crude ethyl acetate extract. Subsequently, ultrasound-assisted extraction of the mycelium was performed using 200 mL methanol for 30 minutes, followed by centrifugation and three additional extractions. The combined methanol extracts were evaporated to dryness, producing a crude methanol extract. The methanol residue was mixed with 100 mL of water and further extracted three times with 100 mL of ethyl acetate. The ethyl acetate layers and methanol residues were combined and concentrated to yield the crude metabolite. The blank control was extracted using the same post-treatment as described above.

A 10 mg portion of both the crude extract and reference extract was dissolved in chromatographic-grade methanol to prepare test and reference solutions, each with a concentration of 20.0 μg/mL. This solution was then filtered through a 0.22 µm microporous membrane into a small vial for subsequent UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

2.3. UPLC-MS/MS Methods

For the SRM (Selected Reaction Monitoring) assay, a Shimadzu Nexera X2 LC-30AD UHPLC system was coupled to a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer for the separation and detection of target metabolites. A Shim-pack XR-ODS Ⅲ column (75 × 2 mm i.d., 1.6 μm) was employed for the target dipeptide separation at 35 °C. Mobile phase A consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water, while mobile phase B in methanol. A linear gradient elution was used as follows: 0~4 min, 5~40% B; 4~4.5 min, 40~100% B; 4.5~6.5 min, 100% B; 6.5~6.6 min, 100~5% B; 6.6~10 min, 5% B, with a flow rate of 0.3 µL/min.

Key MS parameters included a spray voltage of 4Kv, gas flow rates (nebulizer: 2 L/min, heating: 10 L/min, dry gas: 10 L/min), Interface temperature of 300 °C, desolvation line (DL) temperature of 250 °C. For the product ion scan, the precursor ion was set at m/z 155.00, with a scan range of 20~200 and a time interval of 0.2 s.

2.4. Data and Statistical Analysis

All experiments were conducted in triplicate or sextuplicate, and results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The relative standard deviation (RSD) was calculated to assess intra- and inter-day precision, spike-recovery. Calibration curves were generated across a concentration range of 20~220 ng/mL, with R² > 0.999 indicating excellent linearity. Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism 9.0, with a p-value of <0.05 considered significant.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Fungal Strain Growth and Morphology

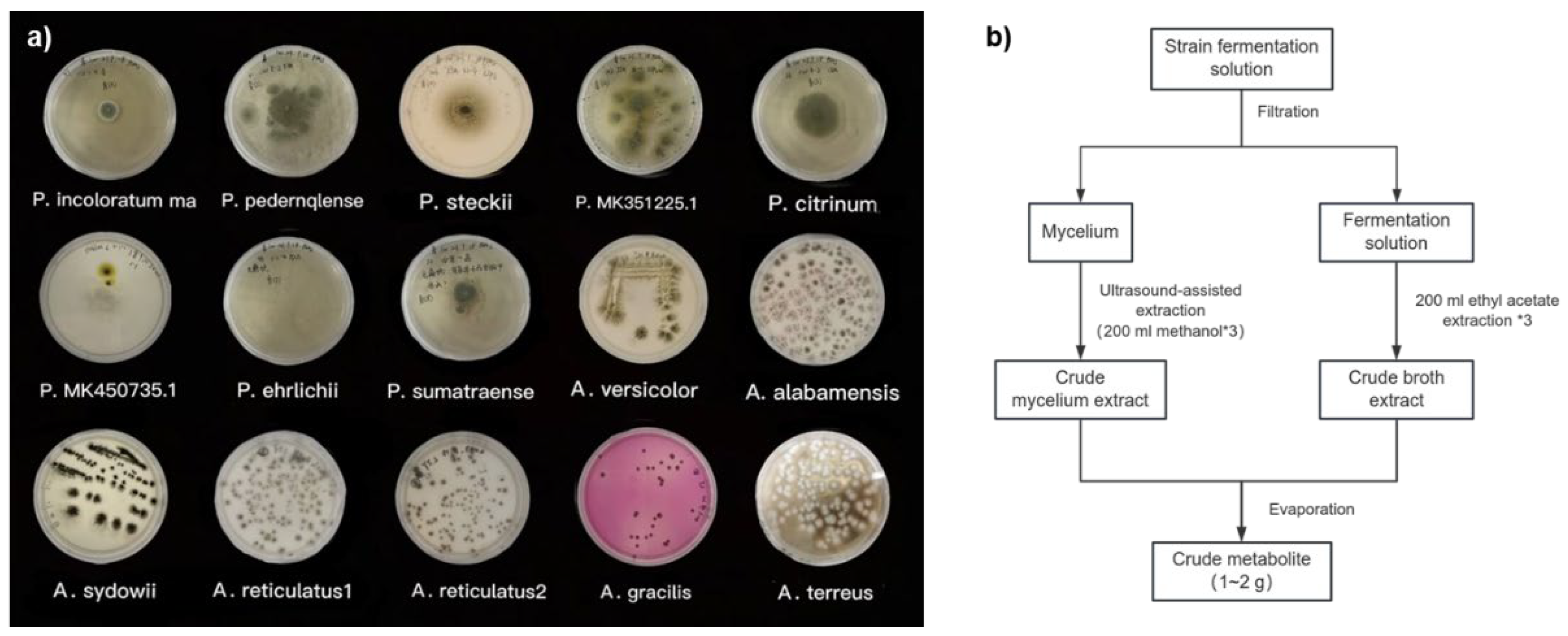

The 15-marine mangrove-sourced fungal strains, comprising 7

Aspergillus and 8

Penicillium species, displayed distinct growth patterns on PDA. Colony diameters ranged from 20 to 45 mm, and the texture varied from cottony to woolly, with abundant aerial mycelia. Both genera formed mycelial pellets that were either spherical or oval, with minor morphological differences in shape and structure. However,

Aspergillus strains were characterized by fast-growing, dense mycelial networks, while

Penicillium strains exhibited slower growth with more loosely branched mycelia [

23].

After seven days of fermentation, crude ethyl acetate and methanol extracts were obtained for further analysis, as outlined in the workflow shown in

Figure 3. These findings suggest that marine-derived fungi, especially from mangrove ecosystems, have great promise for secondary metabolite production under controlled fermentation conditions.

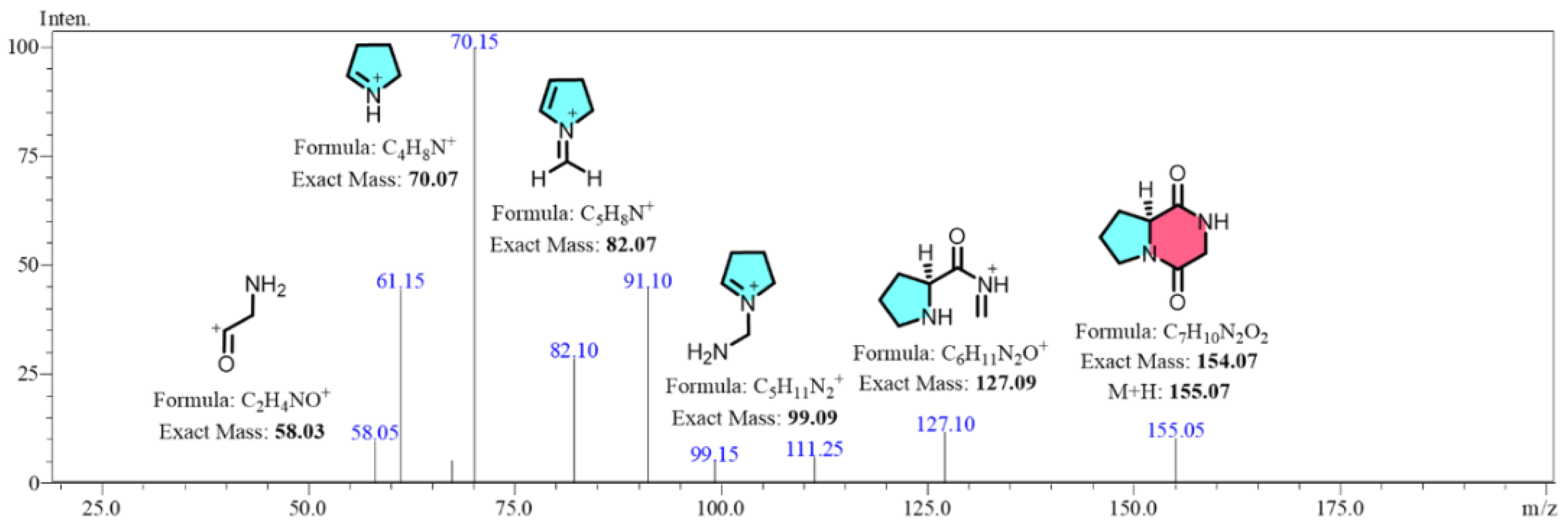

3.2. Monitoring and Quantification of cGP

Building on the research of Furtado [

23], which characterized the secondary mass spectrum of cGP derivatives from

Aspergillus fumigatus, it was confirmed that the main product ions of cGP differ significantly from those of its derivatives due to their unique fragmentation patterns. For example, the product ion at m/z 70 is almost absent in the derivatives, while a distinct ion at m/z 82 remains characteristic of cGP. This allowed us to leverage these highest response strength of ion fragments in Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) mode for effective quantification of cGP, avoiding interference from homologous compounds.

In SRM mode, the parent ion with the highest response was predefined, and after collision-induced fragmentation in Q2, specific sub-ions were filtered in Q3 before being transmitted to the detector. The peak areas of these transitions allowed precise analysis of target metabolites within complex secondary mixtures. The optimized conditions for the parent ion at m/z 155.05 involved a Q1 pre-selection deviation of -0.012 Da and collision energies ranging from -21.0 to -22.0 kV. These conditions generated specific sub-ions at m/z 70.15 and m/z 82.10, which exhibited the highest response values and specificity. The Q3 pre-selection deviations for these sub-ions ranged between -0.015 and -0.013 Da, with the ions designated as the quantitative and qualitative ions, respectively. Additionally, alternative sub-ion fragments generated from the parent ion fragmentation, including m/z 58.05, m/z 99.15, and m/z 127.10, are proposed in their structures in

Figure 4.

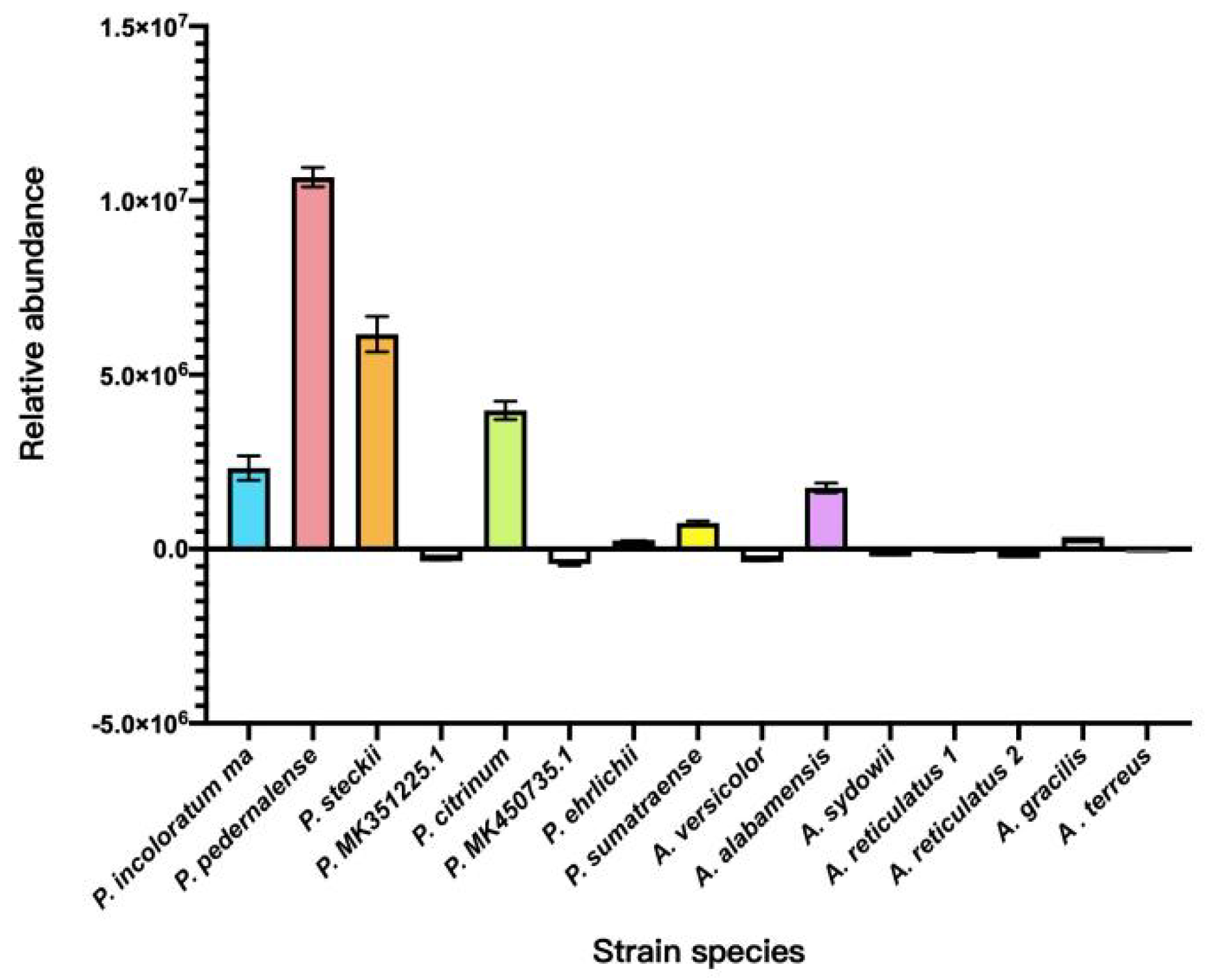

Qualitative analysis of 15 wild-type marine mangrove fungal fermentation extracts using UPLC-MS/MS in SRM mode, based on the characteristic ions of cGP at m/z 70.15 and m/z 82.10, revealed the biosynthetic capacity of these strains. While several strains demonstrated potential for cGP biosynthesis,

Penicillium incoloratum, Penicillium citrinum, and

Aspergillus alabamensis showed notable results. However, the highest abundance of cGP was observed in

Penicillium pedernalense and

Penicillium steckii (

Figure 5).

3.3. Method Validation

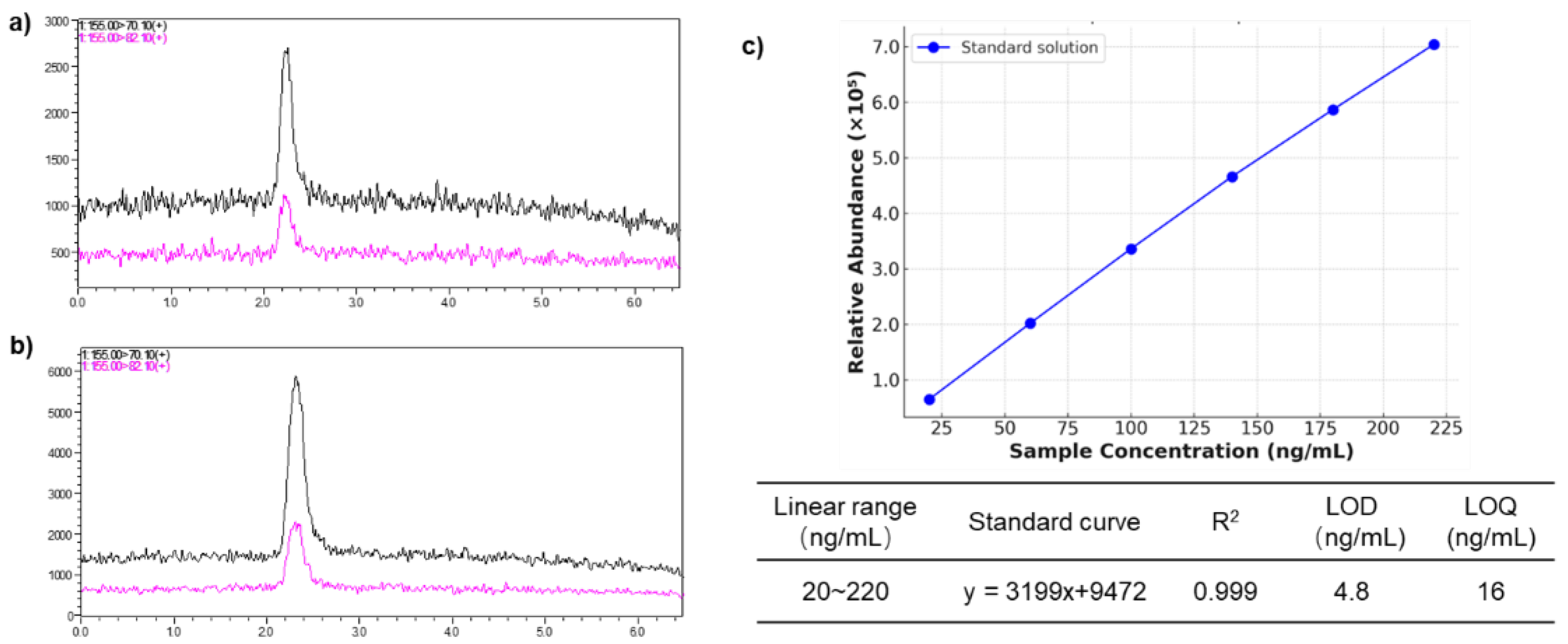

The method was validated in line with FDA guidelines for bioanalytical method validation, focusing on sensitivity, linearity, precision, and accuracy. A highly specific, cost-effective SRM analysis method was developed using a triple quadrupole MS, targeting the quantitative characteristic ions of cGP at m/z 70.15.

The limit of detection (LOD) for cGP was determined to be 4.8 ng/mL, and the limit of quantification (LOQ) was 16.0 ng/mL, based on signal-to-noise ratios of 3 and 10, respectively (

Figure 6). Standard calibration curves were generated in SRM mode by analyzing standard dilutions across a linear concentration range of 20-220 ng/mL. Six concentration levels were analyzed in triplicate to quantify cGP based on relative abundance. The resulting regression equation for the standard curve was Y = 3199X + 9472, with a correlation coefficient of R² > 0.999 (P < 0.0001) (

Figure 6).

The method was also validated for both intra-day and inter-day precision. Intra-day precision (repeatability) was assessed by performing six repeated analyses (n = 6) of a standard solution at specified concentration levels within a single day, with precision expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the replicate measurements. Inter-day precision was evaluated over three separate days within one week to measure reproducibility. The RSD for the repeatability was 1.65% with a mean concentration of 67.45 ng/mL, while the RSD for inter-day precision was 1.54%, with a mean concentration of 67.61 ng/mL—both meeting the acceptance criteria (≤15% deviation). Additionally, recovery was assessed using spiked standard solutions at concentrations of 33.5 ng/mL and 67.0 ng/mL. The recovery ranged from 85.70% to 90.00%, with an RSD of 1.60% to 2.98%, indicating consistent performance across concentration levels. These validation results confirm that the method demonstrates excellent sensitivity, linearity, precision, and recovery, with no observed interference from endogenous components during ionization, further reinforcing the method's reliability.

3.4. Results of cGP Content

The validated method demonstrated excellent performance, confirming its effectiveness for quantifying cGP content in marine mangrove-derived fungal extracts. This method was specifically applied to fermentation extracts from

Penicillium pedernalense and

Penicillium steckii, with the results summarized in Table 4. The cGP content in

Penicillium pedernalense was found to be 67.45 ng/mL, while

Penicillium steckii produced 31.71 ng/mL. In terms of production yield,

Penicillium pedernalense exhibited a significantly higher cGP yield (29.31 mg/L) compared to

Penicillium steckii (8.51 mg/L). Both

Penicillium pedernalense and

Penicillium steckii demonstrated productivity levels that are competitive with

filamentous fungus strains, underscoring their feasibility for industrial applications. [

24]

Table 2. Results of cGP content and corresponding fermentation yield.

Table 2. Results of cGP content and corresponding fermentation yield.

| Sample |

Measured content(ng/mL, Mean ± SD) |

Production(mg/L, Mean ± SD) |

| Penicillium pedernalense |

67.45 ± 1.11 |

29.31 ± 0.61a

|

| Penicillium steckii |

31.71 ± 0.31 |

8.51 ± 0.15a

|

| Blank control |

14.15± 0.16 |

-- |

Although wild-type fungal yields can be enhanced through genetic modification and fermentation optimization, the production levels of

Penicillium pedernalense and

Penicillium steckii demonstrate competitive and potentially superior productivity under the conditions tested in this study. Our findings suggest that

Penicillium pedernalense and

Penicillium steckii naturally produce cGP efficiently, even under unoptimized fermentation conditions. Given the challenges associated with the chemical synthesis of cyclic peptides, biosynthetic pathways utilizing marine fungi offer a promising alternative for sustainable production. [

25] Furthermore, the ability to produce significant quantities of cGP opens new avenues for its application in the pharmaceutical and nutraceutical industries.

4. Conclusions

The marine mangrove fungal strains exhibited distinct growth patterns, with Aspergillus forming fast-growing, dense mycelial networks, while Penicillium displayed slower growth with loosely branched mycelia. Following fermentation, crude extracts were obtained for cGP content analysis, which illustrated the capability of marine-derived fungi from mangroves for the production of valuable secondary metabolites.

This work effectively established and validated a UPLC-MS/MS method for the quantification of cyclic glycine-proline (cGP) in fungal extracts obtained from mangroves. The method demonstrated excellent sensitivity, precision, and recovery, confirming its reliability for studying cyclic peptide biosynthesis. Both tested fungals produced significant amounts of cGP, with P.

pedernalense available a superior yield of 29.31 mg/L, demonstrating their feasibility for sustainable production and promising industrial applications in drug development and biotechnology. [

25]

Future research could focus on optimizing fermentation parameters and employing genetic engineering techniques to enhance cGP yields in these strains. [

26] Also, studying other fungi that grow in mangroves might help find new sources of cGP or related bioactive compounds, which would help create more environmentally friendly ways for pharmaceuticals. The significance of this study lies in its contribution to sustainable marine biotechnology, particularly through quantitative metabolite tracking for precise strain screening, which can be employed for high-value compound production while eliminating the petrochemical consumptions for conventional synthetic approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-H.C. and L.H.; methodology, J.L..; software, F.Q.; validation, J.L., F.Q. and Y.-H.C.; formal analysis, Z.L.; investigation, J.L. and F.Q.; resources, Y.-H.C. and L.H.; data curation, W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L. and L.H.; writing—review and editing, M.Y.; visualization, Y.-H.C. and L.X.; supervision, Y.-H.C.; project administration, L.H.; funding acquisition, Y.-H.C. and L.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2023D022), the Youth Science Fund of Xiamen (No. 3502Z202372059), Xiamen Natural Science Foundation, grant number(3502Z20227311) and the Xiamen Medical College education teaching reform project (No. XBYX2023017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript and in the Supplementary Information.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support from the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2023D022), the Youth Science Fund of Xiamen (No. 3502Z202372059), Xiamen Natural Science Foundation, grant number(3502Z20227311) and the Xiamen Medical College education teaching reform project (No. XBYX2023017).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Borthwick, A.D. 2,5-Diketopiperazines: Synthesis, reactions, medicinal chemistry, and bioactive natural products. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3641–3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Q.; Li, X.; Wu, S. Structures and biological activities of diketopiperazines from marine organisms: A review. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, J.; Li, F.; Kang, D.; Pitcher, T.; Dalrymple-Alford, J.; Shorten, P.; Singh-Mallah, G. Cyclic glycine-proline (cGP) normalises insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) function: Clinical significance in the ageing brain and in age-related neurological conditions. Molecules 2023, 28, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gizzo, L.; Bliss, G.; Palaty, C.; Kolevzon, A. Caregiver perspectives on patient-focused drug development for Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Alamri, Y.; Liu, K.; MacAskill, M.; Harris, P.; Brimble, M.; Dalrymple-Alford, J.; Prickett, T.; Menzies, O.; Laurenson, A.; et al. Supplementation of blackcurrant anthocyanins increased cyclic glycine-proline in the cerebrospinal fluid of Parkinson patients: Potential treatment to improve insulin-like growth factor-1 function. Nutrients 2018, 10, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Yeom, H.S.; Ryu, J.; Bode, H.B.; Kim, Y. Phenylethylamides derived from bacterial secondary metabolites specifically inhibit an insect serotonin receptor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baures, P.W.; Ojala, W.H.; Costain, W.J.; Ott, M.C.; Pradhan, A.; Gleason, W.B.; Mishra, R.K.; Johnson, R.L. Design, synthesis, and dopamine receptor modulating activity of diketopiperazine peptidomimetics of L-prolyl-L-leucylglycinamide. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 3594–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Rodriguez, M.L.; Morcillo, M.J.; Fernandez, E.; Benhamú, B.; Tejada, I.; Ayala, D.; Viso, A.; Campillo, M.; Pardo, L.; Delgado, M.; et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of a new model of arylpiperazines. 8. computational simulation of ligand-receptor interaction of 5-HT1AR agonists with selectivity over α1-adrenoceptors. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 2548–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajdel, P.; Bednarski, M.; Sapa, J.; Nowak, G. Ergotamine and nicergoline-facts and myths. Pharmacol. Rep. 2015, 67, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, M.; Torres-Hernández, F.; Viveros-Ceballos, J.L. Highly diastereoselective synthesis of cyclic α-aminophosphonic and α-aminophosphinic acids from glycyl-ʟ-Proline 2,5-diketopiperazine. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 2019, 7378–7383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizu, T.; Tokunaga, M.; Fukuda, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Goromaru, T.; Takemoto, S. Molecular capture and conformational change of diketopiperazines containing proline residues by epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate in water. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 69, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiya, S.; Grundmann, A.; Li, S.M.; Turner, G. Improved tryprostatin B production by heterologous gene expression in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2009, 46, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, P.; Correia, I.; Le Chevalier, F.; Dubois, S.; Jacques, I.; Canu, N.; Moutiez, M.; Thai, R.; Gondry, M.; Lequin, O.; et al. Reprogramming Escherichia coli for the production of prenylated indole diketopiperazine alkaloids. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Ying, J.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Ding, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Cyclic dipeptides formation from linear dipeptides under potentially prebiotic earth conditions. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 675821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Cai, R.; Liu, Z.; Cui, H.; She, Z. Secondary metabolites from mangrove-associated fungi: Source, chemistry and bioactivities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 560–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.N.; Cai, J.; Wang, B.; Chen, L.Y.; Pan, C.X.; Chen, S.J.; Huang, G.L.; Zheng, C.J. Secondary Metabolites from the Mangrove-Derived Fungus Penicillium sp. TGM112 and their Bioactivities. Chem. Nat. Compd., 2022, 58, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Lin, J.; Qin, F.; Xu, L.; Luo, L. Exploring Sources, Biological Functions, and Potential Applications of the Ubiquitous Marine Cyclic Dipeptide: A Concise Review of Cyclic Glycine-Proline. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magocha, T.A.; Zabed, H.; Yang, M.; Yun, J.; Zhang, H.; Qi, X. Improvement of industrially important microbial strains by genome shuffling: Current status and future prospects. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 257, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauniyar, N. Parallel reaction monitoring: a targeted experiment performed using high resolution and high mass accuracy mass spectrometry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 28566–28581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hu, X.; Pang, J.; Wang, X.K.; Li, G.Q.; Li, C.R.; Y, X.Y.; You, X.F. Parallel Reaction Monitoring Mass Spectrometry for Rapid and Accurate Identification of β-Lactamases Produced by Enterobacteriaceae. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 784628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.T.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.Y.; Yin, Y.X. Development and evaluation of a parallel reaction monitoring strategy for large-scale targeted metabolomics quantification. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4478–4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.H.; Chang, Y.W.; Ma, C.W.; Luo, L.Z.; Lu, T.J.; Yao, J.Y. Identification of bioactive compounds and inhibitory effects of TNF-α and COX-2 in the extract from cultured three-spot seahorse (H. trimaculatus). Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 12, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furtado, N.A.J.C.; Vessecchi, R.; Tomaz, J.C.; Galembeck, S.E.; Bastos, J.K.; Lopes, N.P.; Crotti, A.E.M. Fragmentation of diketopiperazines from Aspergillus fumigatus by electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS). J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.Z.; Han, H.Y.; Sui, D.; Tan, S.N.; Liu, C.L.; Wang, P.C.; Xie, C.L.; Xia, X.K; Gao, J.M.; Liu, C.W. Efficient production of a cyclic dipeptide (cyclo-TA) using heterologous expression system of filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Chen, Q.H.; Jiang, T.; Cai, Y.W.; Huang, G.L.; Sun, X.P.; Zeng, C.J. Secondary metabolites from the mangrove-derived fungus Penicillium verruculosum and their bioactivities. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2021, 57, 588–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widodo, W.; Billerbeck, S. Natural and engineered cyclodipeptides: Biosynthesis, chemical diversity, and engineering strategies for diversification and high-yield bioproduction. Eng. Microbiol. 2022, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).