Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

23 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Current Approach to Disruptive Technologies

3. From Disruptive to Invasive Technologies

3.1. Research Philosophy of the Study

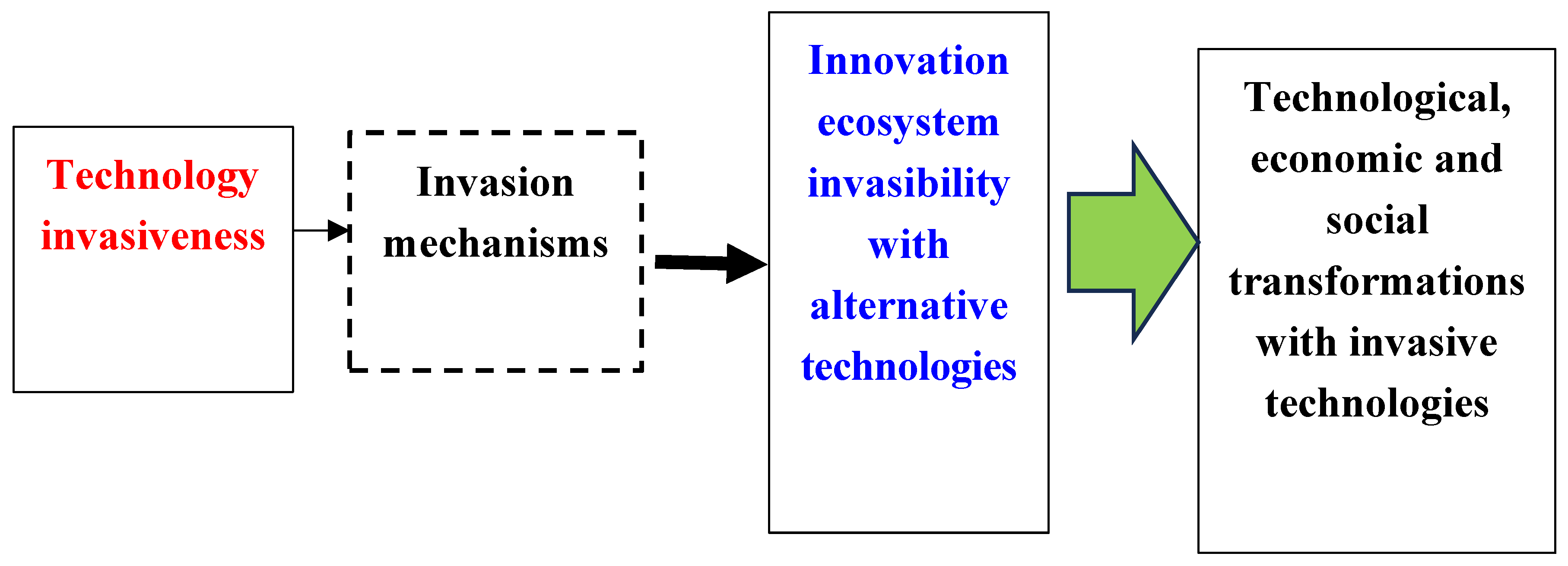

3.2. Theory of Invasive Technologies

- -

- Invasion is an elements that bursts and spreads in a space, occupying the position of other elements in system.

- -

- Invasive technologies can replace, in a specific system, other technologies in several life cycles, producing new technologies and innovations that have the potential to spread in different domains and sectors leading to technological, economic and social change on the invaded environment (‘impacts’)

- Postulates

- -

- Invasive technologies is a driver of technological and social change

- -

- Invasive behaviour ⇒ technological evolution

- -

- Invasive technologies change system and have an adaptive behaviour to different systems and at the same time eliminate the less suitable technologies, leaving the more suitable ones to survive.

- Predictions of the theory of invasive technologies

- ■

- Technological change =f(invasive technologies)

- ■

- Rate of growth of invasive technology i in a system S is > 2 × rate of growth in alternative technologies j, j=1, …, m

- ■

- Invasive technology (i) is better adapted than alternative technologies (j) in S, if and only if (i) is able to spread, survive and produce new innovations in S than is (j) over time.

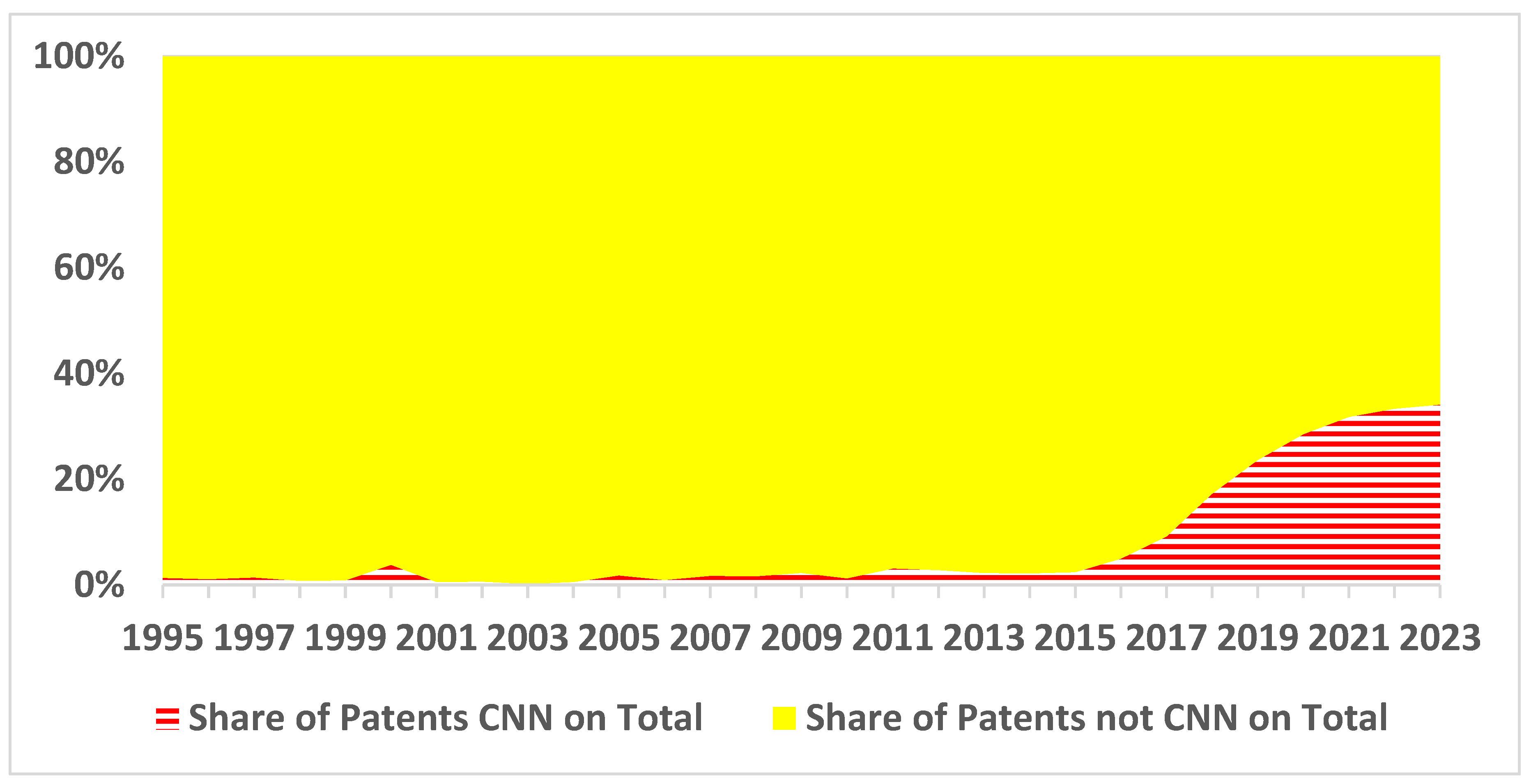

3.3. Research Setting to Test the Theoretical Prediction of Invasive Technologies: Case study Of Transformers Technologies

3.4. Study Design

- ■

- Logic structure of search string

- ■

- Transformers, period under study 2017-2023

- ■

- Convolutional Neural networks, in short CNN, period under study before 2017, year of the emergence of Transformers

- ■

- Measures and sources of data

- ■

- Samples

- r= rate of exponential growth of technology from 0 to t period

- P0 is the patents to the time 0

- Pt is the patents to time t.

- T= t−0

- Trends of invasive technology i at t are analyzed with the following log-linear model:

- yt is patents of invasive technologies

- t=time

- ut = error term

- (a = constant; b=coefficient of regression)

4. Empirical Evidence: Test of Prediction in Invasive Technologies

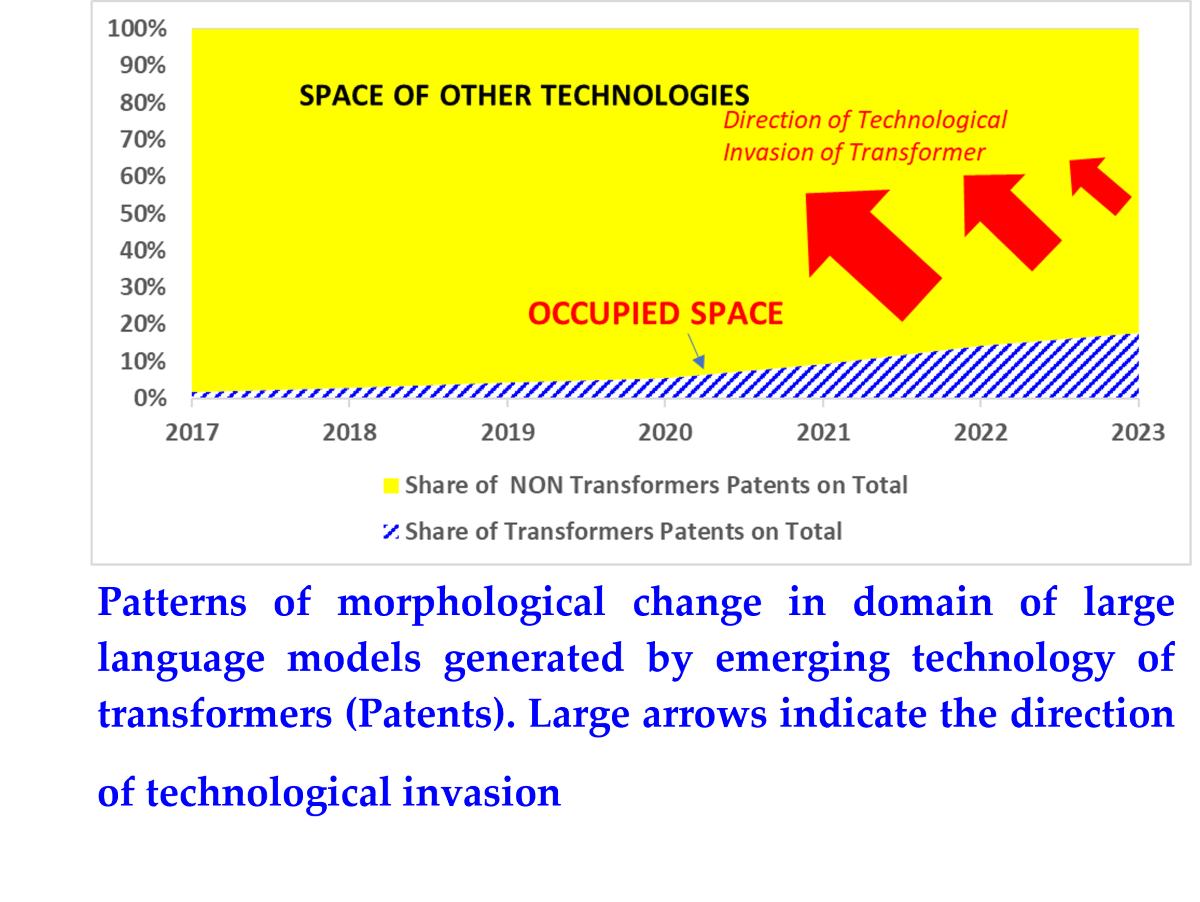

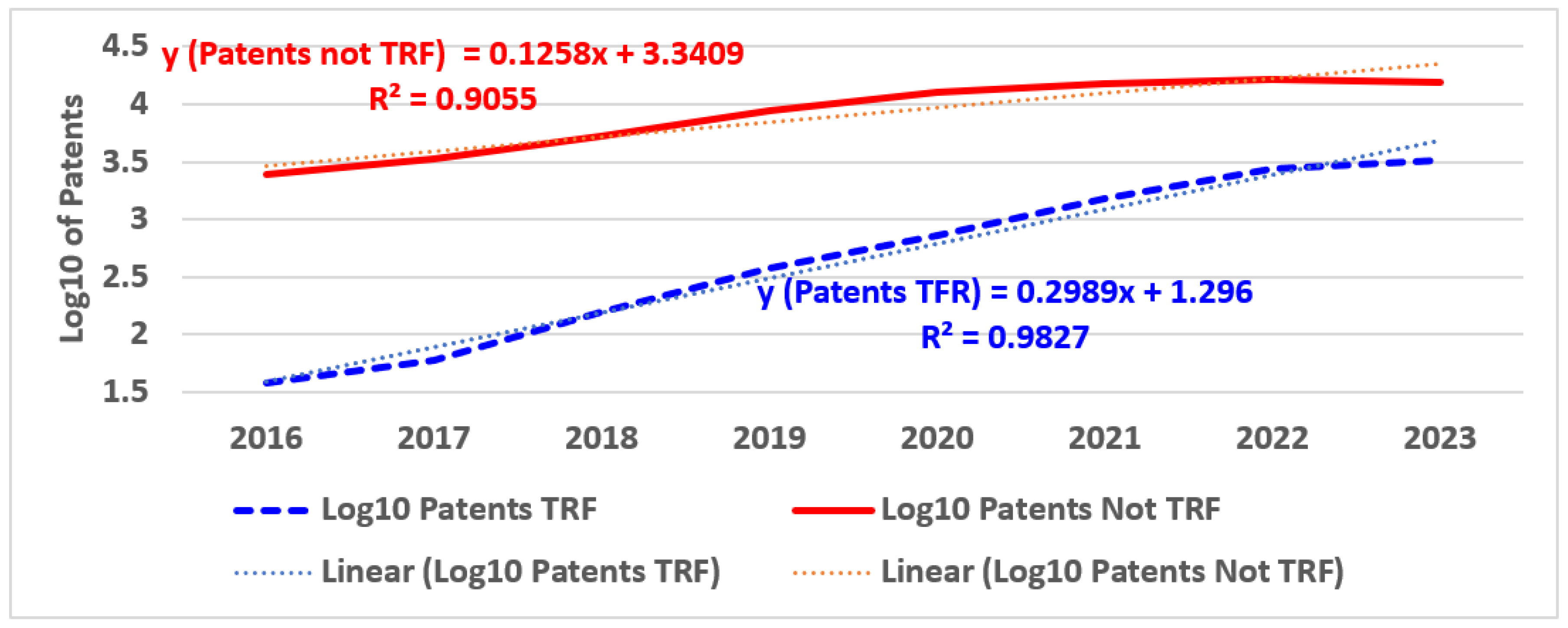

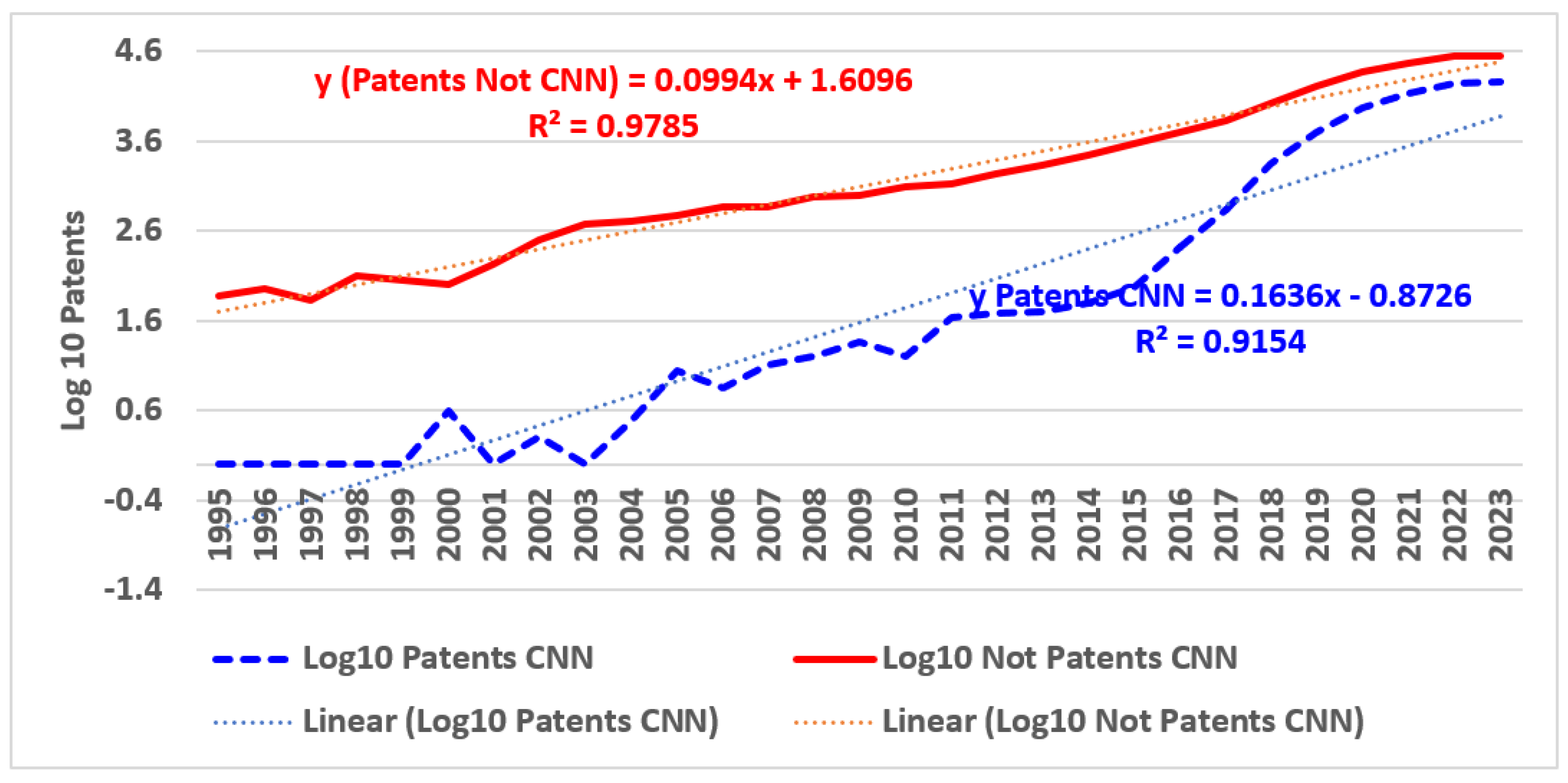

4.1. Pattens of Temporal and Morphological Change in Technologies

5. Analysis of Findings

5.1. Explanation of Empirical Evidence of Invasive Technologies

- Pervasiveness to propagate in many sectors

- Technical improvement that reduce costs in products and processes

- Product and process innovation spawning

| Disruptive technologies | Invasive technologies | |

|---|---|---|

| Technological type | General Purpose Technologies | Disruptive + General Purpose Technologies |

| Technical characteristic | Pervasiveness and cost reduction | Pervasiveness and innovation spawning |

| Business strategy | Exploitation | Exploration and exploitation (ambidexterity) |

| Evolutionary patterns | Mutualistic interaction | Symbiotic interaction |

| Rate of growth | Rapid | Accelerate |

| Period of diffusion | Medium run | Shot run |

| Current Example | 5G technology | Generative Pretraining Transformers |

5.1. Most Important Drivers of Technological Invasion

- (a)

- scientific and technological advances and interaction between fields

- (b)

- socio-economic activities

- (c)

- environmental turbulence and threats (wars, conflicts, emergencies, etc.)

- (d)

- societal awareness, values, lifestyle

- (e)

- cooperation, legislation & agreements, technological strategies at national and corporate level

6. Concluding Remarks

6.1. Theoretical Implications

- Properties of invasive technologies

- ○

- ITi has a very rapid growth, acceleration

- ○

- ITi disrupts the use of other technologies.

- ○

- ITi invades and captures the scientific space of other technologies

- ○

- ITi creates new dynamic capabilities (the organization’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments; Teece et al. 1997)

- -

- Moreover, other characteristics of invasive technologies are:

- -

- Pervasiveness over time and space in the short run

- -

- Adaptation to a wide range of market applications and environmental conditions

- -

- Interaction with manifold technologies

- -

- Associations with different activities in science and society

- (1)

- invasiveness of technologies

- (2)

- invasibility of innovation ecosystems and

- (3)

- recurrent (patterns of the technologies) × (ecosystem interactions) that may support a technological invasion syndrome based on a set of concurrent aspects that usually form an identifiable pattern.

6.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

- (a)

- exploration activities when rate of growth, and uncertainty in research fields and technology is higher. However, organizations that focus only on exploration face the risk of wasting resources on research topics and emerging technologies that may fail and never be developed, so a stage to gate model can reduce failure risk and foster the development of new technology in these contexts (Coccia, 2023);

- (b)

- an exploitation approach to innovation strategy when rate of growth is lower with consequential more stable technological trajectories.

6.3. Limitations and Development of Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abernathy W. J., Clark K. B. 1985. Innovation: Mapping the winds of creative destruction. Research Policy, Volume 14, Issue 1, pp. 3-22. [CrossRef]

- Adner R. 2002. When Are Technologies Disruptive: A Demand-Based View of the Emergence of Competition. Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23 (2002), pp. 667. [CrossRef]

- Adner R., Zemsky P. 2005. Disruptive Technologies and the Emergence of Competition. The RAND Journal of Economics, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Summer), pp. 229-254.

- Amarlou, A., & Coccia, M. (2023). Estimation of diffusion modelling of unhealthy nanoparticles by using natural and safe microparticles. Nanochemistry Research, 8(2), 117-121. [CrossRef]

- Anastopoulos I., Bontempi E., Coccia M., Quina M., Shaaban M. 2023. Sustainable strategic materials recovery, what’s next? Next Sustainability, VSI: Sustainable strategic materials recovery_Editorial, n. 100006. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, B.W., 2009. The Nature of Technology. What it is and How It Evolves. Allen Lane–Penguin Books, London.

- Assael, Yannis; Sommerschield, Thea; Shillingford, Brendan; Bordbar, Mahyar; Pavlopoulos, John; Chatzipanagiotou, Marita; Androutsopoulos, Ion; Prag, Jonathan; de Freitas, Nando (2022). Restoring and attributing ancient texts using deep neural networks. Nature. 603 (7900): 280–283. [CrossRef]

- Baotian He B., Li Y. 2022. Multi-future Transformer: Learning diverse interaction modes for behaviour prediction in autonomous driving, IET Intelligent Trasport Systems. [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.M., 2014. Complexity, social complexity, and modeling. J. Archaeol. Method Theory 21, 306–324. [CrossRef]

- Basalla, G., 1988. The History of Technology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Bettencourt, L. M., Kaiser, D. I. & Kaur, J. 2009. Scientific discovery and topological transitions in collaboration networks. Journal of Informetrics 3, 210–221. [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal DA. 2006. Interactions between resource availability and enemy release in plant invasion. Ecology Letters 9: 887–895. [CrossRef]

- Boccaccio, C., Comoglio, 2006. P. Invasive growth: a MET-driven genetic programme for cancer and stem cells. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 637–645 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Bowler, D. E., & Benton, T. G. (2005). Causes and consequences of animal dispersal strategies: relating individual behaviour to spatial dynamics. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 80(2), 205–225. [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S. R. (2023). "Eight Things to Know about Large Language Models". arXiv:2304.00612 [cs.CL].

- Bresnahan, T.F. and Trajtenberg, M. (1995) ‘General purpose technologies: ‘engines of growth’?’, Journal of Econometrics, Annals of Econometrics, Vol. 65, No. 1, pp.83–108. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A., Ko, J., Hu, S.J., Koren, Y., 2007. Co-evolution of product families and assembly systems. CIRP Ann. Manuf. Technol. 56 (1), 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Burger, B., Kanbach, D.K., Kraus, S., Breier, M. and Corvello, V. (2023), "On the use of AI-based tools like ChatGPT to support management research", European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 26 No. 7, pp. 233-241. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese G, Coccia M, Rolfo S (2005) Strategy and market management of new product development: evidence from Italian SMEs. Int J Prod Dev 2(1–2):170–189. [CrossRef]

- Calvano E. 2007. Destructive Creation. SSE/EFI Working Paper Series in Economics and Finance, No 653, December.

- Cavaleri MA, Sack L. 2010. Comparative water use of native and invasive plants at multiple scales: a global meta-analysis. Ecology 91: 2705–2715. [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, E., Ferrari E., Coccia M. 2015. Likely technological trajectories in agricultural tractors by analysing innovative attitudes of farmers. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, vol. 15, n. 2, pp. 158–177. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z., Y. Song, Y. Ma, G. Li, R. Wang and H. Hu 2023. "Interaction in Transformer for Change Detection in VHR Remote Sensing Images," in IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 61, pp. 1-12, 2023, Art no. 3000612. [CrossRef]

- Christensen C. 1997. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Christensen C. 2006. The ongoing process of building a theory of disruption. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23, 39–55. [CrossRef]

- Christensen C., Raynor, M. 2003. The Innovator’s Solution. Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

- Christensen C., Raynor, M. and McDonald, R. 2015. What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review. December, pp. 44-53.

- Christensen C., Raynor, M. and McDonald, R. 2015. What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review. December, pp. 44-53.

- Christensen C.M. 1997. The Innovator's Dilemma. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chun YJ, van Kleunen M, Dawson W. 2010. The role of enemy release, tolerance and resistance in plant invasions: linking damage to performance. Ecology Letters 13: 937–946. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2003. Metrics of R&D performance and management of public research labs," IEMC '03 Proceedings. Managing Technologically Driven Organizations: The Human Side of Innovation and Change, 2003, pp. 231-235. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2004. Spatial metrics of the technological transfer: analysis and strategic management, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 16, n. 1, pp. 31-52. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2005. A Scientometric model for the assessment of scientific research performance within public institutes. Scientometrics, vol. 65, n. 3, pp. 307-321. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2005. Measuring Intensity of technological change: The seismic approach, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, vol. 72, n. 2, pp. 117-144. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2005. Metrics to measure the technology transfer absorption: analysis of the relationship between institutes and adopters in northern Italy. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialization, vol. 4, n. 4, pp. 462-486. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2006. Analysis and classification of public research institutes, World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, vol. 3, n. 1, pp.1-16. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2008. New organizational behaviour of public research institutions: Lessons learned from Italian case study. International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, vol. 2, n. 4, pp. 402–419. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2008. Spatial mobility of knowledge transfer and absorptive capacity: analysis and measurement of the impact within the geoeconomic space, The Journal of Technology Transfer, vol. 33, n. 1, pp. 105-122. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2009. What is the optimal rate of R&D investment to maximize productivity growth? Technological Forecasting & Social Change, vol. 76, n. 3, pp. 433-446. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2010. Foresight of technological determinants and primary energy resources of future economic long waves. International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy, vol. 6, n. 4, pp. 225–232. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2010. Public and private R&D investments as complementary inputs for productivity growth. International Journal of Technology, Policy and Management, vol. 10, n. 1/2, pp. 73-91. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2010. Spatial patterns of technology transfer and measurement of its friction in the geo-economic space. International Journal of Technology Transfer and Commercialisation, vol. 9, n. 3, pp. 255-267. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2012. Converging genetics, genomics and nanotechnologies for groundbreaking pathways in biomedicine and nanomedicine. Int. J. Healthcare Technology and Management, vol. 13, n. 4, pp. 184-197. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2012. Evolutionary trajectories of the nanotechnology research across worldwide economic players, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 24, n.10, pp. 1029-1050. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2014. Converging scientific fields and new technological paradigms as main drivers of the division of scientific labour in drug discovery process: the effects on strategic management of the R&D corporate change, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 26, n. 7, pp. 733-749. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2014. Socio-cultural origins of the patterns of technological innovation: What is the likely interaction among religious culture, religious plurality and innovation? Towards a theory of socio-cultural drivers of the patterns of technological innovation, Technology in Society, vol. 36, n. 1, pp. 13-25. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2015. General sources of general purpose technologies in complex societies: Theory of global leadership-driven innovation, warfare and human development, Technology in Society, vol. 42, August, pp. 199-226. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2015. Spatial relation between geo-climate zones and technological outputs to explain the evolution of technology. Int. J. Transitions and Innovation Systems, vol. 4, nos. 1-2, pp. 5-21. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2015. Technological paradigms and trajectories as determinants of the R&D corporate change in drug discovery industry. Int. J. Knowledge and Learning, vol. 10, n. 1, pp. 29–43. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2016. Radical innovations as drivers of breakthroughs: characteristics and properties of the management of technology leading to superior organizational performance in the discovery process of R&D labs, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 28, n. 4, pp. 381-395. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2016. The relation between price setting in markets and asymmetries of systems of measurement of goods, The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, vol. 14, part B, November, pp. 168-178. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2017. Sources of disruptive technologies for industrial change. L’industria –rivista di economia e politica industriale, vol. 38, n. 1, pp. 97-120. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2017. Sources of technological innovation: Radical and incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firms. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 29, n. 9, pp. 1048-1061. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2017. The Fishbone diagram to identify, systematize and analyze the sources of general purpose technologies. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences, vol. 4, n. 4, pp. 291-303. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2017. The source and nature of general purpose technologies for supporting next K-waves: Global leadership and the case study of the U.S. Navy's Mobile User Objective System, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, vol. 116, pp. 331-339. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2017a. Disruptive firms and industrial change, Journal of Economic and Social Thought, vol. 4, n. 4, pp. 437-450. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2017b. Varieties of capitalism’s theory of innovation and a conceptual integration with leadership-oriented executives: the relation between typologies of executive, technological and socioeconomic performances. Int. J. Public Sector Performance Management, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 148–168. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. A Theory of the General Causes of Long Waves: War, General Purpose Technologies, and Economic Change. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, vol. 128, March, pp. 287-295 (S0040-1625(16)30652-7). [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. An introduction to the methods of inquiry in social sciences, J. Adm. Soc. Sci. - JSAS – vol. 5, n. 2, pp. 116-126. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. Classification of innovation considering technological interaction, Journal of Economics Bibliography, vol. 5, n. 2, pp. 76-93. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. Competition between basic and applied research in the organizational behaviour of public research labs, J. Econ. Lib., vol. 5, n. 2, pp. 118-133. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. Disruptive firms and technological change, Quaderni IRCrES-CNR, vol., 3, n. 1, pp. 3-18, ISSN (print): 2499-6955, ISSN (online): 2499-6661. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. General properties of the evolution of research fields: a scientometric study of human microbiome, evolutionary robotics and astrobiology, Scientometrics, vol. 117, n. 2, pp. 1265-1283. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018. Optimization in R&D intensity and tax on corporate profits for supporting labor productivity of nations, The Journal of Technology Transfer, vol. 43, n. 3, pp. 792-814. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018a. An introduction to the theories of institutional change, Journal of Economics Library, vol. 5, n. 4, pp. 337-344. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018a. Theorem of not independence of any technological innovation, Journal of Economics Bibliography, vol. 5, n. 1, pp. 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2018a. Theorem of not independence of any technological innovation, J. Econ. Bib. – JEB, vol. 5, n. 1, pp. 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. A Theory of classification and evolution of technologies within a Generalized Darwinism, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 31, n. 5, pp. 517-531. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Artificial intelligence technology in oncology: a new technological paradigm. ArXiv.org e-Print archive, Cornell University, USA. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.06871.

- Coccia M. 2019. Comparative Institutional Changes. A. Farazmand (ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Comparative Theories of the Evolution of Technology. In: Farazmand A. (eds) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Destructive technologies as driving forces of new technological cycles for industrial and corporate change, Journal of Economic and Social Thought, Vol 6, No. 4, pp. 252-277. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Intrinsic and extrinsic incentives to support motivation and performance of public organizations, Journal of Economics Bibliography, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 20-29. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. New Patterns of Technological Evolution: Theory and Practice, ©KSP Books, ISBN: 978-605-7602-88-6.

- Coccia M. 2019. Technological Parasitism. Journal of Economic and Social Thought, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 173-209. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. The theory of technological parasitism for the measurement of the evolution of technology and technological forecasting, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 141, pp. 289-304. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Theories of Revolution. In: Farazmand A. (eds) Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Theories of the evolution of technology based on processes of competitive substitution and multi-mode interaction between technologies. Journal of Economics Bibliography, vol. 6, n. 2, pp. 99-109. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. What is technology and technology change? A new conception with systemic-purposeful perspective for technology analysis, Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 145-169. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019. Why do nations produce science advances and new technology? Technology in society, vol. 59, November, n. 101124, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2019a. Killer Technologies: the destructive creation in the technical change. ArXiv.org e-Print archive, Cornell University, USA. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1907.12406.

- Coccia M. 2020. Asymmetry of the technological cycle of disruptive innovations. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 32, n. 12, p. 1462-1477. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020. Comparative Concepts of Technology for Strategic Management. In: Farazmand A. (eds), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer Nature. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020. Deep learning technology for improving cancer care in society: New directions in cancer imaging driven by artificial intelligence. Technology in Society, vol. 60, February, pp. 1-11, art. n. 101198. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020. Destructive Technologies for Industrial and Corporate Change. In: Farazmand A. (eds), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020. Fishbone diagram for technological analysis and foresight. Int. J. Foresight and Innovation Policy, Vol. 14, Nos. 2/3/4, pp. 225-247. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020. The evolution of scientific disciplines in applied sciences: dynamics and empirical properties of experimental physics, Scientometrics, n. 124, pp. 451-487. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020a. Deep learning technology for improving cancer care in society: New directions in cancer imaging driven by artificial intelligence. Technology in Society, vol. 60, February, pp. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020b. Destructive Technologies for Industrial and Corporate Change. In: Farazmand A. (eds), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer, Cham, Springer. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2020c. The evolution of scientific disciplines in applied sciences: dynamics and empirical properties of experimental physics, Scientometrics, n. 124, pp. 451-487. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2021. Effects of human progress driven by technological change on physical and mental health, STUDI DI SOCIOLOGIA, 2021, N. 2, pp. 113-132. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2021. Technological Innovation. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Edited by George Ritzer and Chris Rojek. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2022. Disruptive innovations in quantum technologies for social change. Journal of Economics Bibliography, vol. 9, n.1, pp. 21-39. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2022. Probability of discoveries between research fields to explain scientific and technological change. Technology in Society, vol. 68, n. 101874. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2022. Technological trajectories in quantum computing to design a quantum ecosystem for industrial change, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023. High potential of technology to face new respiratory viruses: mechanical ventilation devices for effective healthcare to next pandemic emergencies, Technology in Society, vol. 73, n. 102233. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023. Innovation Failure: Typologies for appropriate R&D management. Journal of Social and Administrative Sciences - J. Adm. Soc. Sci., vol. 10, n.1-2 (March-June), pp.10-30. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023. New directions of technologies pointing the way to a sustainable global society. Sustainable Futures, vol. 5, December, n. 100114. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023. New Perspectives in Innovation Failure Analysis: A taxonomy of general errors and strategic management for reducing risks. Technology in Society, vol. 75, n. 102384. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M. 2023. Promising technologies for fostering simultaneous environmental and socioeconomic sustainability. Journal of Economic and Social Thought - J. Econ. Soc. Thoug., vol. 10, n.1-2 (March-June), pp. 28-47. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., 2018. Disruptive firms and technological change, Quaderni IRCrES-CNR, vol., 3, n. 1, pp. 3-18. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Bellitto M. 2018. Human progress and its socioeconomic effects in society, Journal of Economic and Social Thought, vol. 5, n. 2, pp. 160-178. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Benati I. 2018. Comparative Models of Inquiry, A. Farazmand (ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Benati I. 2018. Comparative Studies. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance –section Bureaucracy (edited by Ali Farazmand). Chapter No. 1197-1, pp. 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Bontempi E. 2023. New trajectories of technologies for the removal of pollutants and emerging contaminants in the environment. Environmental Research, vol. 229, n. 115938. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Falavigna G., Manello A. 2015. The impact of hybrid public and market-oriented financing mechanisms on scientific portfolio and performances of public research labs: a scientometric analysis, Scientometrics, vol. 102, n. 1, pp. 151-168. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Finardi U. 2012. Emerging nanotechnological research for future pathway of biomedicine. International Journal of Biomedical nanoscience and nanotechnology, vol. 2, nos. 3-4, pp. 299-317. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Finardi U. 2013. New technological trajectories of non-thermal plasma technology in medicine. Int. J. Biomedical Engineering and Technology, vol. 11, n. 4, pp. 337-356. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Finardi U., Margon D. 2012. Current trends in nanotechnology research across worldwide geo-economic players, The Journal of Technology Transfer, vol. 37, n. 5, pp. 777-787. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Ghazinoori S., Roshani S. 2023. Evolutionary Pathways of Ecosystem Literature in Organization and Management Studies. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Mosleh M., Roshani S., 2022. Evolution of quantum computing: Theoretical and innovation management implications for emerging quantum industry. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Mosleh M., Roshani S., 2024. Evolution of Quantum Computing: Theoretical and Innovation Management Implications for Emerging Quantum Industry. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, vol. 71, pp. 2270-2280. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Rolfo S. 2000. Ricerca pubblica e trasferimento tecnologico: il caso della regione Piemonte in Rolfo S. (eds) Innovazione e piccole imprese in Piemonte, FrancoAngeli Editore, Milano (Italy), pp. 236-256. ISBN: 9788846418784.

- Coccia M., Rolfo S. 2008. Strategic change of public research units in their scientific activity, Technovation, vol. 28, n. 8, pp. 485-494. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Roshani S. 2024. General laws of funding for scientific citations: how citations change in funded and unfunded research between basic and applied sciences. Journal of Data and Information Science, 9(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Roshani S. 2024. General laws of funding for scientific citations: how citations change in funded and unfunded research between basic and applied sciences. Journal of Data and Information Science, 9(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Roshani S., Mosleh M. 2021. Scientific Developments and New Technological Trajectories in Sensor Research. Sensors, vol. 21, no. 23: art. N. 7803. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Wang L. 2015. Path-breaking directions of nanotechnology-based chemotherapy and molecular cancer therapy, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 94(May):155–169. [CrossRef]

- Coccia M., Wang L. 2016. Evolution and convergence of the patterns of international scientific collaboration, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 113, n. 8, pp. 2057-2061. Available online: www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1510820113.

- Coccia M., Watts J. 2020. A theory of the evolution of technology: technological parasitism and the implications for innovation management, Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, vol. 55, n. 101552. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M. 2024. Variability in Research Topics Driving Different Technological Trajectories. Preprints 2024, 2024020603. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M., Roshani, S. 2024. Research funding and citations in papers of Nobel Laureates in Physics, Chemistry and Medicine, 2019-2020. Journal of Data and Information Science, 9(2), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Coccia, M.; Roshani, S.; Mosleh, M. 2022. Evolution of Sensor Research for Clarifying the Dynamics and Properties of Future Directions. Sensors, 22(23), 9419. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.G., Franzoni, C. and Veugelers, R. (2015) ‘Going radical: producing and transfering disruptive innovation’, The Journal of Technology Transfer, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp.663–669.

- Crane D. 1972. Invisible Colleges: Diffusion of Knowledge in Scientific Communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Daehler CC. 2003. Performance comparisons of co-occurring native and alien invasive plants: implications for conservation and restoration. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 34: 183–211. [CrossRef]

- Dawkins R. 1983. "Universal Darwinism." In Evolution from Molecules to Man, edited by D. S. Bendall, 403–425. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- de Visser, K. E., & Joyce, J. A. (2023). The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer cell, 41(3), 374–403. [CrossRef]

- Dell Technologies 2023. Transformer (machine learning model). Available online: https://infohub.delltechnologies.com/l/generative-ai-in-the-enterprise/transformer-models/ (accessed on December 2023).

- Den Hartigh, E., Ortt, J.R., Van De Kaa, G., Stolwijk, C.C.M. 2016. Platform control during battles for market dominance: The case of Apple versus IBM in the early personal computer industry. Technovation, 48-49, pp. 4–12. [CrossRef]

- Denning, S. 2018. Succeeding in an increasingly Agile world. Strategy and Leadership, 46(3), pp. 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Devlin J.; Chang, Ming-Wei; Lee, Kenton; Toutanova, Kristina (October 11, 2018). BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv:1810.04805v2 [cs.CL].

- Dosi G. 1988. Sources, Procedures, and Microeconomic Effects of Innovation. Journal of Economic Literature, 26(3), 1120–1171. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2726526.

- Duncan, R. (1976). The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. Killman, R. H., L. R. Pondy, and D. Sleven (eds.) The Management of Organization. New York: North Holland. 167-188.

- Essl, F., Dullinger, S., Rabitsch, W., Hulme, P. E., Hülber, K., Jarošík, V., Kleinbauer, I., Krausmann, F., Kühn, I., Nentwig, W., Vilà, M., Genovesi, P., Gherardi, F., Desprez-Loustau, M. L., Roques, A., & Pyšek, P. (2011). Socioeconomic legacy yields an invasion debt. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(1), 203–207. [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H., Leydesdorff, L. (1998). A Triple Helix of University—Industry—Government Relations: Introduction. Industry and Higher Education, 12(4), 197-201. [CrossRef]

- Farrell C. J. 1993. A theory of technological progress. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 44 (2): 161-178. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J. C., & Pry, R. H. (1971). A Simple Substitution Model of Technological Change. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 3,75-88. [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, S., Bergstrom, C. T., Börner, K., Evans, J. A., Helbing, D., Milojević, S., Petersen, A. M., , F., Sinatra, R., Uzzi, B., Vespignani, A., Waltman, L., Wang, D., & Barabási, A. L. 2018. Science of science. Science, 359(6379), eaao0185. [CrossRef]

- Foster R.N. 1986. Innovation: the attacker's advantage. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Freeman C. 1974. The economics of industrial innovation. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

- Garud R., Simpson B., Langley A., Tsoukas H. 2015. (Eds.), The Emergence of Novelty in Organizations, Oxford University Press.

- Gholizadeh H.; Rakotoarivony M.N.A.; Hassani K.; Johnson K.G.; Hamilton R.G.; Fuhlendorf S.D.; Schneider F.D.; Bachelot B. 2024. Advancing our understanding of plant diversity-biological invasion relationships using imaging spectroscopy. Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 304, n. 114028. [CrossRef]

- Guimera, R., Uzzi, B., Spiro, J. & Amaral, L. 2008. Team assembly mechanisms determine collaboration network structure and team performance. Science 308, 697–702. [CrossRef]

- Henderson R. 2006. The Innovator’s Dilemma as a Problem of Organizational Competence. Journal of Product Innovation Management, vol. 23, pp. 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Hicks D., Isett K. 2020. Powerful Numbers: exemplary quantitative studies of science that had policy impact. Quantitative Studies of Science. Available online: http://works.bepress.com/diana_hicks/54/.

- Hill, C., Rothaermel, F. 2003. The performance of incumbent firms in the face of radical technological innovation. Academy of Management Review, vol. 28, pp. 257–274. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G. M. 2002. “Darwinism in Economics: From Analogy to Ontology.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 12: 259–281. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, G. M., and T. Knudsen. 2006. “Why we Need a Generalized Darwinism, and why Generalized Darwinism is not Enough.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 61 (1): 1–19.

- Hodgson, G. M., and T. Knudsen. 2008. “In Search of General Evolutionary Principles: Why Darwinism is too Important to be Left to the Biologists.” Journal of Bioeconomics 10 (1): 51–69. [CrossRef]

- Hulme PE. 2012. Weed risk assessment: a way forward or a waste of time? Journal of Applied Ecology 49: 10–19. [CrossRef]

- Iacopini I., Milojević S., Latora V. 2018. Network Dynamics of Innovation Processes, Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 120, n. 048301, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Jeschke JM, Aparicio LG, Haider S, Heger T, Lortie CJ, Py_sek P, Strayer DL. 2012. Support for major hypotheses in invasion biology is uneven and declining. NeoBiota 20: 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, B. and Rousseau, P.L. (2005) ‘General purpose technologies’, in Aghion, P. and Durlauf, S.N. (Eds.): Handbook of Economic Growth, Ch. 18, Vol. 1B, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- Kariampuzha, William; Alyea, Gioconda; Qu, Sue; Sanjak, Jaleal; Mathé, Ewy; Sid, Eric; Chatelaine, Haley; Yadaw, Arjun; Xu, Yanji; Zhu, Qian (2023). "Precision information extraction for rare disease epidemiology at scale". Journal of Translational Medicine. 21 (1): 157. PMC 9972634. PMID 36855134. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. A. 2000. Investigations. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kauffman, S. A. 2016. Humanity in a Creative Universe. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kauffman, S. A. 2019. A World Beyond Physics: The Emergence and Evolution of Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kauffman, S. A., A. Gare. 2015. “Beyond Descartes and Newton: Recovering Life and Humanity.” Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 119 (3): 219–244. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S. A., P. Clayton. 2006. “On Emergence, Agency, and Organization.” Biology and Philosophy 21 (4): 501–521. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A., 1996. Investigations: the Nature of Autonomous Agents and the Worlds They Mutually Create. SFI Working Papers. Santa Fe Institute, USA.

- Kessler E. H., Chakrabarti A. K. 1996. Innovation Speed: A Conceptual Model of Context, Antecedents, and Outcomes. The Academy of Management Review, nol. 21, n. 4, pp. 1143-1191. [CrossRef]

- Krakhmal, N. V., Zavyalova, M. V., Denisov, E. V., Vtorushin, S. V., & Perelmuter, V. M. (2015). Cancer Invasion: Patterns and Mechanisms. Acta naturae, 7(2), 17–28. [CrossRef]

- Krinkin K., Shichkina, Y. and Ignatyev, A. 2023. Co-evolutionary hybrid intelligence is a key concept for the world intellectualization", Kybernetes, Vol. 52 No. 9, pp. 2907-2923. [CrossRef]

- Kueffer C. 2010. Transdisciplinary research is needed to predict plant invasions in an era of global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25: 619–620. [CrossRef]

- Kueffer C. 2012. The importance of collaborative learning and research among conservationists from different oceanic islands. Revue d’Ecologie (Terre et Vie) 11 (Suppl.): 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Kueffer, C., Pyšek, P., & Richardson, D. M. (2013). Integrative invasion science: model systems, multi-site studies, focused meta-analysis and invasion syndromes. The New phytologist, 200(3), 615–633. [CrossRef]

- Lehman, N. E., S. A. Kauffman. 2021. “Constraint Closure Drove Major Transitions in the Origins of Life.” Entropy 23 (1): 105. [CrossRef]

- Levit, G., U. Hossfeld, and U. Witt. 2011. “Can Darwinism be “Generalized” and of What use Would This be?” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 21 (4): 545–562. [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, R.G., Bekar, C.T. and Carlaw, K.I. (1998) ‘What requires explanation?’, in Helpman, E. (Ed.): General Purpose Technologies and Long-term Economic Growth, pp.15–54, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Lipsey, R.G., Carlaw, K.I. and Bekar, C.T. (2005) Economic Transformations: General Purpose Technologies and Long Term Economic Growth, pp.131–218, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- M. Coccia, “A theory of classification and evolution of technologies within a Generalised Darwinism,” Technol. Anal. Strategic Manage., vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 517–531, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Asymmetry of the technological cycle of disruptive innovations,” Technol. Anal. Strategic Manage, vol. 32, no. 12, pp. 1462–1477, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Classification of innovation considering technological interaction,” Journal of Economics Bibliography, vol. 5, n. 2, pp. 76-93, 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Comparative Institutional Changes,” in Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, A. Farazmand, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019a, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Destructive Technologies for Industrial and Corporate Change,” in Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, A. Farazmand, Ed., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2020b, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “New Perspectives in Innovation Failure Analysis: A taxonomy of general errors and strategic management for reducing risks,” Technology in Society, vol. 75, p. 102384, Nov. 2023a. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Political economy of R&D to support the modern competitiveness of nations and determinants of economic optimization and inertia,” Technovation, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 370–379, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Radical innovations as drivers of breakthroughs: characteristics and properties of the management of technology leading to superior organisational performance in the discovery process of R&D labs,” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 28, no. 4, pp. 381–395, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Sources of technological innovation: Radical and incremental innovation problem-driven to support competitive advantage of firms,” Technol. Anal. Strategic Manage., vol. 29, no. 9, pp. 1048–1061, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Technological Innovation,” in The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, 1st ed., G. Ritzer, Ed., Wiley, 2021, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Technological trajectories in quantum computing to design a quantum ecosystem for industrial change,” Technol. Anal. Strategic Manage., pp. 1–16, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, “Why do nations produce science advances and new technology?,” Technology in Society, vol. 59, p. 101124, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, S. Roshani, and M. Mosleh, “Evolution of Quantum Computing: Theoretical and Innovation Management Implications for Emerging Quantum Industry,” IEEE Trans. Eng. Manage., pp. 1–11, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccia, S. Roshani, and M. Mosleh, “Scientific Developments and New Technological Trajectories in Sensor Research,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 23, p. 7803,. 2021. [CrossRef]

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2, 71-87. [CrossRef]

- Mario Coccia, “Sources of disruptive technologies for industrial change,” L’industria, no. 1, pp. 97–120, 2017a. [CrossRef]

- Markides C. 2006. Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi Y. (2023) Reinventing search with a new AI-powered Microsoft Bing and Edge, your copilot for the web, Microsoft Feb 7, 2023. Available online: https://blogs.microsoft.com/blog/2023/02/07/reinventing-search-with-a-new-ai-powered-microsoft-bing-and-edge-your-copilot-for-the-web/ (accessed on February 2024).

- Menon P. (2023). Introduction to Large Language Models and the Transformer Architecture. Medium. Available online: https://rpradeepmenon.medium.com/introduction-to-large-language-models-and-the-transformer-architecture-534408ed7e61 (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Moles AT, Flores-Moreno H, Bonser SP, Warton DI, Helm A, Warman L, Eldridge DJ, Jurado E, Hemmings FA, Reich PB, et al. 2012. Invasions: the trail behind, the path ahead, and a test of a disturbing idea. Journal of Ecology 100: 116–127. [CrossRef]

- Mosleh, M., Roshani, S. & Coccia, M. Scientific laws of research funding to support citations and diffusion of knowledge in life science. Scientometrics 127, 1931–1951 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Nelson R.R. 2008. Factors affecting the power of technological paradigms, Industrial and Corporate Change, 17(3), pp.485–497. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, R. 2006. “Evolutionary Social Science and Universal Darwinism.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 16 (5): 491–510. [CrossRef]

- Norton, J. A., & Bass, F. M. (1987). A Diffusion Theory Model of Adoption and Substitution for Successive Generations of High-Technology Products. Management Science, 33(9), 1069–1086. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2631875.

- Núñez-Delgado, Avelino, Zhien Zhang, Elza Bontempi, Mario Coccia, Marco Race, and Yaoyu Zhou. 2023. Editorial on the Topic “New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants” Materials, vol. 16, no. 2: 725. [CrossRef]

- Open AI 2015. "Introducing OpenAI". OpenAI. December 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- OpenAI (2022). Introducing ChatGPT. Available online: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Oppenheimer, R. 1955. "Analogy in Science." Sixty-Third annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA, September 4.

- Pagliaro M., Coccia M. 2021. How self-determination of scholars outclasses shrinking public research lab budgets, supporting scientific production: a case study and R&D management implications. Heliyon. vol. 7, n. 1, e05998. [CrossRef]

- Parker JD, Torchin ME, Hufbauer RA, Lemoine NP, Alba C, Blumenthal DM, Bossdorf O, Byers JE, Dunn AM, HeckmanRWet al. 2013. Do invasive species perform better in their new ranges? Ecology 98: 985–994. [CrossRef]

- Pelicice, F.M., Agostinho, A.A., Alves, C.B.M. et al. Unintended consequences of valuing the contributions of non-native species: misguided conservation initiatives in a megadiverse region. Biodivers Conserv 32, 3915–3938 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pinaya, Walter H. L.; Graham, Mark S.; Kerfoot, Eric; Tudosiu, Petru-Daniel; Dafflon, Jessica; Fernandez, Virginia; Sanchez, Pedro; Wolleb, Julia; da Costa, Pedro F.; Patel, Ashay (2023). "Generative AI for Medical Imaging: extending the MONAI Framework". arXiv:2307.15208. [CrossRef]

- Porter M.E., 1980, Competitive strategy, Free Press, New York.

- Price, D. 1986. Little science, big science. Columbia University Press.

- Pyšek P, Jaro_s_ık V, Hulme PE, Pergl J, Hejda M, Schaffner U, Vil_a M. 2012. A global assessment of invasive plant impacts on resident species, communities and ecosystems: the interaction of impact measures, invading species’ traits and environment. Global Change Biology 18: 1725–1737. [CrossRef]

- Pyšek P, Richardson DM. 2007. Traits associated with invasiveness in alien plants: where do we stand? In: Nentwig W, ed. Biological invasions. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer, 97–125. [CrossRef]

- Pyšsek P, Jaro_s_ık V,HulmePE,K€uhn I, Wild J, ArianoutsouM,Bacher S, Chiron F, Didziulis V, Essl F, et al. 2010. Disentangling the role of environmental and human pressures on biological invasions across Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 107: 12 157–12 162. [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management, 34, 375-409. [CrossRef]

- Roco, M., Bainbridge, W. 2002. Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance: Integrating From the Nanoscale. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 4, 281–295 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Rogers EM (1962) The Diffusion of Innovations The Free Press, New York.

- Rosenberg, N. 1976. Perspectives on Technology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Roshani S., Coccia M., Mosleh M. 2022. Sensor Technology for Opening New Pathways in Diagnosis and Therapeutics of Breast, Lung, Colorectal and Prostate Cancer. HighTech and Innovation Journal, vol.3, n.3, September, pp. 356-375. [CrossRef]

- Roshani, S., Bagherylooieh, M. R., Mosleh, M., & Coccia, M. (2021). What is the relationship between research funding and citation-based performance? A comparative analysis between critical disciplines. Scientometrics, 126(9), 7859-7874. [CrossRef]

- Sahal D. 1981. Patterns of Technological Innovation. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., Reading, Massachusetts.

- Schreiber, S.J., Ryan, M.E. 2011. Invasion speeds for structured populations in fluctuating environments. Theor Ecol 4, 423–434 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C. 2014. ““Generalized Darwinism” and the Quest for an Evolutionary Theory of Policy-Making.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 24 (3): 479–513. [CrossRef]

- Schuster, P. 2016. “Major Transitions in Evolution and in Technology.” Complexity 21 (4): 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Scopus 2024. Start exploring. Documents. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic#basic (accessed on 9 November 2023).

- Smith MD, Knapp AK, Collins SL. 2009. A framework for assessing ecosystem dynamics in response to chronic resource alterations induced by global change. Ecology 90: 3279–3289. [CrossRef]

- Stoelhorst, J. W. 2008. “The Explanatory Logic and Ontological Commitments of Generalized Darwinism.” Journal of Economic Methodology 15 (4): 343–363. [CrossRef]

- Sun X., Kaur, J., Milojevic' S., Flammini A., Menczer F. 2013. Social Dynamics of Science. Scientific Reports, vol. 3, n. 1069, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., Shuen, A. 1997. Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3088148.

- Tojin T. Eapen,Daniel J. Finkenstadt,Josh Folk,and Lokesh Venkataswamy 2023. How Generative AI Can Augment Human Creativity". Harvard Business Review. June-August, 2023.

- Tria F., Loreto V., Servedio V. D. P., Strogatz S. H. 2014. The dynamics of correlated novelties, Scientific Reports vol. 4, n. 5890, pp. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Tripsas M. 1997. Unraveling the process of creative destruction: Complementary assets and incumbent survival in the typesetter industry. Strategic Management Journal, vol. 18 (Summer Special Issue), pp. 119–142.

- Tushman M., Anderson P. 1986. Technological Discontinuities and Organizational Environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 31, n. 3, pp. 439–465. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi B. 2023. The Rise of Transformers: A Journey through Mathematics and Model Design in Neural Networks. Medium. Available online: https://tyagi-bhaumik.medium.com/the-rise-of-transformers-a-journey-through-mathematics-and-model-design-in-neural-networks-cdc599c58d12 (accessed on February 2023).

- Utterback JM (1994) Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation (Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA).

- Utterback JM, Brown JW (1972) Monitoring for technological opportunities. Business Horizons. 15(October): 5–15.

- Utterback, James M.; Pistorius, Calie; Yilmaz, Erdem 2019. The Dynamics of Competition and of the Diffusion of Innovations. MIT Sloan School Working Paper;5519-18. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/117544.

- Van Kleunen M, Weber E, Fischer M. 2010. A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Ecology Letters 13: 235–245. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani A., Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, Illia Polosukhin 2017. Attention Is All You Need. ArXiv (Computation and Language and machine Learning), arXiv:1706.03762.

- Wagner, A., & Rosen, W. (2014). Spaces of the possible: universal Darwinism and the wall between technological and biological innovation. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface, 11(97), 20131190. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C. 2008. The new invisible college: Science for development. Brookings Institution Press.

- Walker, L.R., Smith, S.D. (1997). Impacts of Invasive Plants on Community and Ecosystem Properties. In: Luken, J.O., Thieret, J.W. (eds) Assessment and Management of Plant Invasions. Springer Series on Environmental Management. Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Wang Mei-Hui, Kot Mark, 2001. Speeds of invasion in a model with strong or weak Allee effects, Mathematical Biosciences, Volume 171, Issue 1, pp. 83-97. [CrossRef]

- Wright G. 1997. Towards A More Historical Approach to Technological Change, The Economic Journal, vol. 107, September, pp. 1560-1566. [CrossRef]

- Ziman J. (ed.) 2000. Technological innovation as an evolutionary process. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA.

| Dependent variable Publications | Constant α |

Coefficient β |

R2 | F | Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Log10 Patents Transformers technology | 1.30*** |

0.30*** (0.016) |

0.98 (0.105) |

339.95*** | 2016-2023 |

| Log10 Patents not Transformers technology | 3.34*** | 0.13*** (0.017) |

0.91 (0.107) |

57.71*** | |

| Log10 Patents CNN technology | −0.87*** | 0.16*** (0.010) |

0.92 (0.431) |

292.05*** | 1995-2023 |

| Log10 Patents not CNN technology | 1.61*** | 0.10*** (0.003) |

0.98 (0.125) |

1227.66*** |

| Transformers | Domain excluded Transformers | |

|---|---|---|

| Patents | Rate% | Rate % |

| r TRF = Exponential growth 2016-2023 | 55.82 | 23.02 |

| r’’ TRF = Exponential growth 2021-2023 | 25.81 | 0.76 |

| CNN | Domain excluded CNN | |

| Patents | Rate% | Rate % |

| r’ CNN = Exponential growth 1995-2023 | 33.84 | 36.11 |

| Generative Pretraining Transformers 2016-2023 |

Convolutional Neural Networks CNN 1995-2023 |

|

| Rate of Exponential growth (patents) | 55.82 | 23.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).