Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

23 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

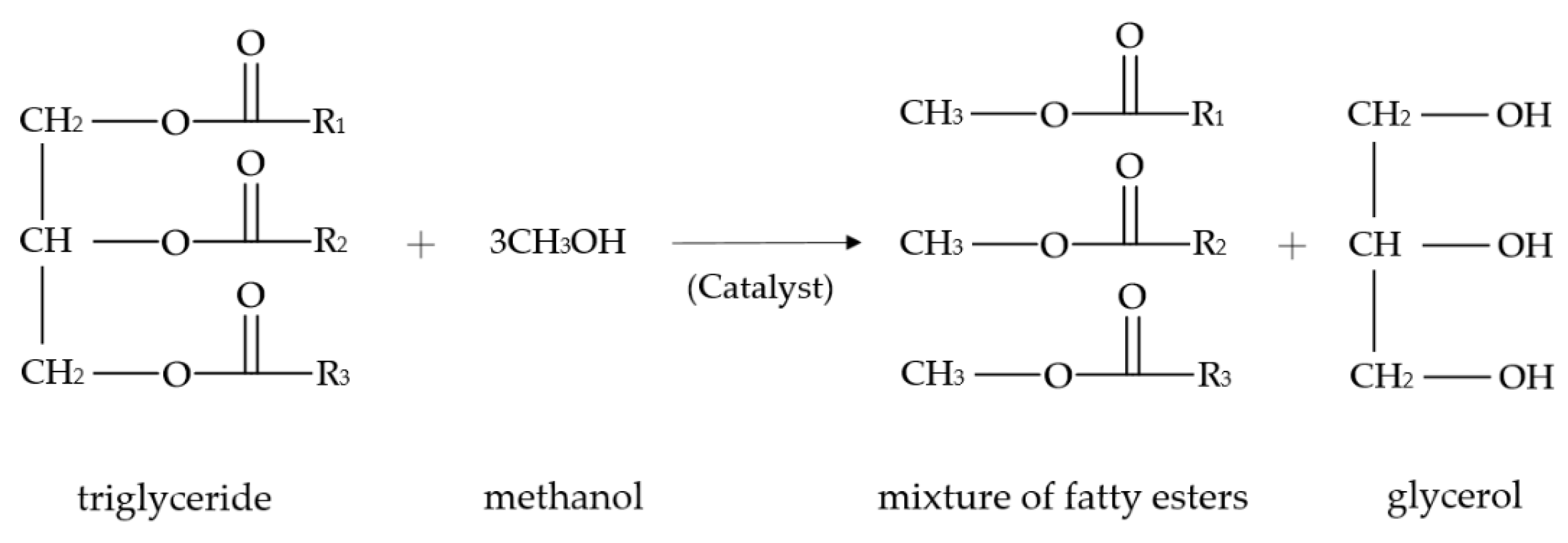

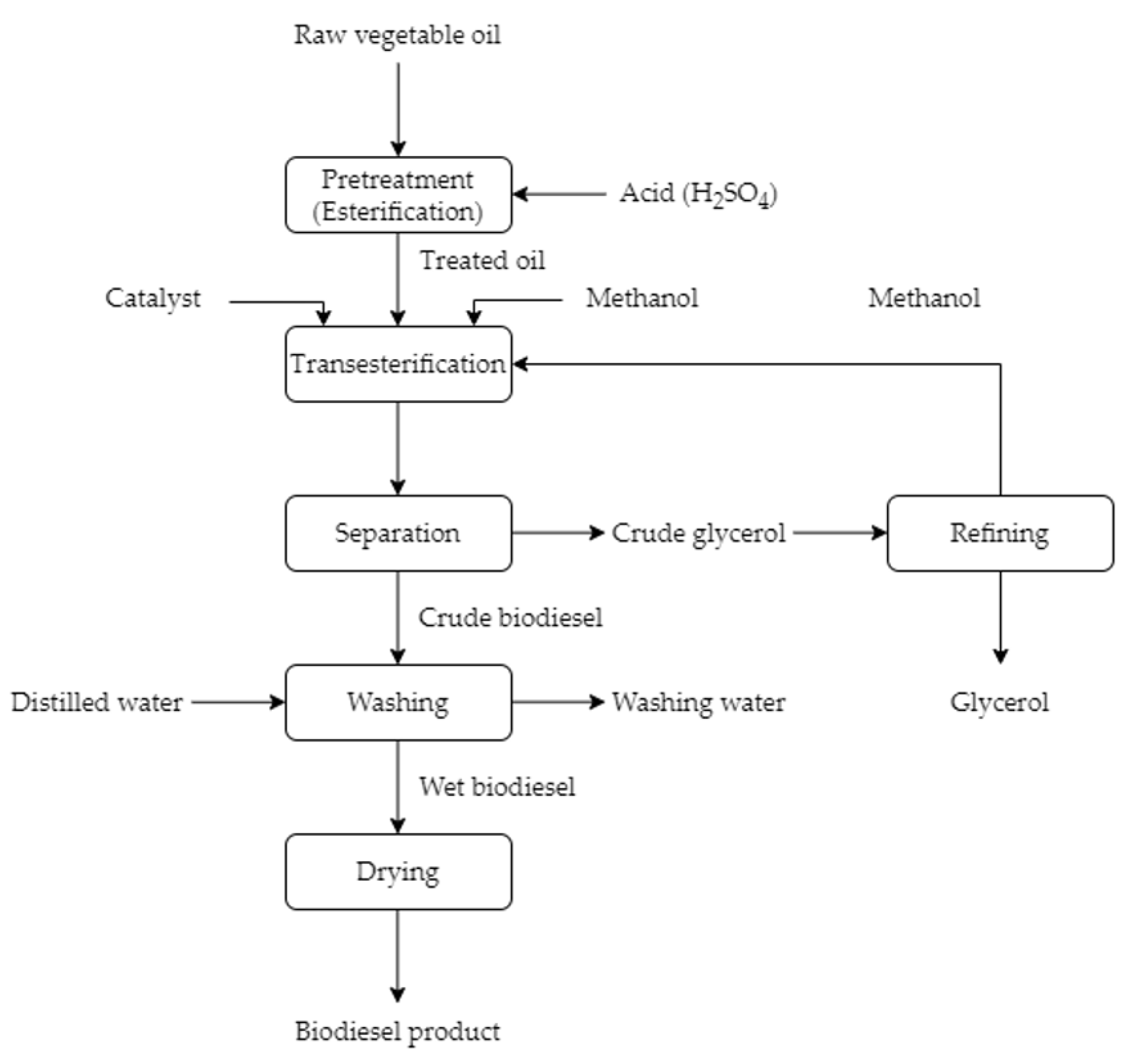

2. An Overview of Biodiesel Production Processes

3. Overview of Solid Heterogeneous Catalysts for Biodiesel Production

4. Biomass Potassium-Rich Ash as a Green Catalyst for Biodiesel Production

- (1)

-

Ash elements with acidic feature and high melting pointsThey include Si, Al, Fe, Na and Ti. For example, melting point of silicon dioxide (SiO2) is about 1700°C.

- (2)

-

Ash elements with base feature and less volatiles at high temperatureThey can refer to Ca and Mg. In the case of calcium oxide, its melting point is as high as over 2,500°C.

- (3)

-

Ash elements with base feature and more volatiles at high temperatureThey can involve K, P and S. For instance, melting point of potassium oxide (K2O) is approximately 400°C.

5. Conclusions and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perera, F. Pollution from fossil-fuel combustion is the leading environmental threat to global pediatric health and equity: Solutions exist. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista. Biodiesel Consumption Worldwide from 2004 to 2023, with a Forecast until 2030. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1440983/worldwide-consumption-of-biodiesel/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Rahman, M.A. Valorization of harmful algae E. compressa for biodiesel production in presence of chicken waste derived catalyst. Renew. Energy 2018, 129 (Part A), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Caland, L.B.; Silveira, E.L.C.; Tubino, M. Determination of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium cations in biodiesel by ion chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 718, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balat, M.; Balat, H. A critical review of bio-diesel as a vehicular fuel. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49(10), 2727–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirbas, A. Progress and recent trends in biodiesel fuels. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50(1), 14–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helwani, Z.; Othman, M.R.; Aziz, N.; Fernando, W.J.N.; Kim, J. Technologies for production of biodiesel focusing on green catalytic techniques: A review. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90(12), 1502–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandari, V.; Devarai, S.K. Biodiesel production using homogeneous, heterogeneous, and enzyme catalysts via transesterification and esterification reactions: A critical review. Bioenerg. Res. 2022, 15, 935–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hama, S.; Kondo, A. Enzymatic biodiesel production: An overview of potential feedstocks and process development. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 135, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christopher, L.P.; Kumar, H.; Zambare, V.P. Enzymatic biodiesel: Challenges and opportunities. Appl. Energy 2014, 119, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veljković, V.B.; Stamenković, O.S.; Tasić, M.B. The wastewater treatment in the biodiesel production with alkali-catalyzed transesterification. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuru, S.M.Y.; Delhiwala, Y.; Koorla, P.B.; Mekala, M. A review on the biodiesel production: Selection of catalyst, pre-treatment, post treatment methods. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2(1), 100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atadashi, I.M.; Aroua, M.K.; Abdul Aziz, A.R.; Sulaiman, N.M.N. The effects of catalysts in biodiesel production: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19(1), 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhul, A.M.; Kalam, M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Rizwanul Fattah, I.M.; Reham, S.S.; Rashed, M.M. State of the art of biodiesel production processes- a review of the heterogeneous catalyst. RSC Adv., 2015, 5, 101023–101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, A.L.; Ronconi, C.M.; Mota, C.J.A. Heterogeneous basic catalysts for biodiesel production. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 2877–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardhiah, H.H.; Ong, H.C.; Masjuki, H.H.; Lim, S.; Lee, H.V. A review on latest developments and future prospects of heterogeneous catalyst in biodiesel production from non-edible oils. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 67, 1225–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, A.; Dhir, A.; Mahla, S.K.; Mohapatra, S.K. An overview of solid base heterogeneous catalysts for biodiesel production. Catal. Rev. 2018, 60(4), 594–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambhulkar, D.K.; Ugwekar, R.P.; Bhanvase, B.A.; Barai, D.P. (2020). A review on solid base heterogeneous catalysts: Preparation, characterization and applications. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2020, 209(4), 433–484.

- Rizwanul Fattah, I.M.; Ong, H.C.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Mofijur, M.; Silitonga, A.S.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Ahmad, A. State of the art of catalysts for biodiesel production. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 101. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar, M.; Karmegam, N.; Gundupalli, M.P.; Gebeyehu, K.B.; Asfaw, B.T.; Chang, S.W.; Ravindran, B.; Awasthi, M.K. Heterogeneous base catalysts: Synthesis and application for biodiesel production – A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 331, 125054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, M.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Govindasamy, S.; Aravamudhan, A. Heterogeneous nanocatalysts for sustainable biodiesel production: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 104876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, M.; Ahmad, M.; Zafar, M.; Munir, M.; Mujtaba, M.M.; Sultana, S.; Rozina, S.; El-Khatib, S.E.; Soudagar, M.E.M.; Kalam, M.A. Prospects of catalysis for process sustainability of eco-green biodiesel synthesis via transesterification: A state-of-the-art review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurfitri, I.; Maniam, G.P.; Hindryawati, N.; Yusoff, M.M.; Ganesan, S. Potential of feedstock and catalysts from waste in biodiesel preparation: A review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 74, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, S.; Nath, B.; Kalita, P. Application of agro-waste derived materials as heterogeneous base catalysts for biodiesel synthesis. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy, 2018, 10, 043105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwaha, A.; Rosha, P.; Mohapatra, S.K.; Mahla, S.K.; Dhir, A. Waste materials as potential catalysts for biodiesel production: Current state and future scope. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 181, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.E.; Lim, S.; Pang, Y.L.; Ong, H.C.; Lee, K.T. Synthesis of biomass as heterogeneous catalyst for application in biodiesel production: State of the art and fundamental review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 92, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, S.Y.; Periasamy, L.A.; Goh, C.M.H.; Tan, Y.H.; Mubarak, N.M.; Kansedo, J.; Khalid, M.; Walvekar, R.; Abdullah, E.C. Biodiesel synthesis using natural solid catalyst derived from biomass waste — A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2020, 81, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagumalai, A.; Mahian, O.; Hollmann, F.; Zhang, W. Environmentally benign solid catalysts for sustainable biodiesel production: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, M.; Ayoub, M.; Shamsuddin, R.B.; Mukhtar, A.; Saqib, S.; Zahid, I.; Ameen, M.; Ullah, S.; Al-Sehemi, A.G.; Ibrahim, M. A review on the waste biomass derived catalysts for biodiesel production. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroa, S.; Inambao, F. A review of sustainable biodiesel production using biomass derived heterogeneous catalysts. Eng. Life Sci. 2021, 21(12), 790–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswarlu, K. Ashes from organic waste as reagents in synthetic chemistry: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 3887–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.A.F.d.; de Oliveira, A.d.N.; Esposito, R.; Len, C.; Luque, R.; Noronha, R.C.R.; Rocha Filho, G.N.d.; Nascimento, L.A.S.d. Glycerol and catalysis by waste/low-cost materials—A review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabgan, W.; Jalil, A.A.; Nabgan, B.; Jadhav, A.H.; Ikram, M.; Ul-Hamid, A.; Ali, M.W.; Hassan, N.S. Sustainable biodiesel generation through catalytic transesterification of waste sources: a literature review and bibliometric survey. RSC Adv. 2022, 12(3), 1604–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parida, S.; Singh, M.; Pradhan, S. Biomass wastes: A potential catalyst source for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2022, 18, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, D.T. , Shibeshi, N.T.; Reshad, A.S. Heterogeneous catalysts from metallic oxides and lignocellulosic biomasses ash for the valorization of feedstocks into biodiesel: An Overview. Bioenerg. Res. 2023, 16, 1361–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, S.; Changmai, B.; Vanlalveni, C.; Chhandama, M.V.L.; Wheatley, A.E.H.; Rokhum, S.L. Biomass waste-derived catalysts for biodiesel production: Recent advances and key challenges. Renew. Energy 2024, 223, 120031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutia, G.P.; Phukan, K. Biomass derived heterogeneous catalysts used for sustainable biodiesel production: A systematic review. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, P.K.; Singh, A.K.; Ganachari, S.V.; Pengadeth, D.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Biobased heterogeneous renewable catalysts: Production technologies, innovations, biodiesel applications and circular bioeconomy. Environ. Res. 2024, 261, 119745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansir, N.; Teo, S.H.; Rashid, U.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H. Efficient waste Gallus domesticus shell derived calcium-based catalyst for biodiesel production. Fuel 2018, 211, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, H.; Ong, H.C.; Amini, Z.; Masjuki, H.H.; Mofijur, M.; Su, C.H.; Anjum Badruddin, I.; Khan, T.M.Y. An overview of biodiesel production via calcium oxide based catalysts: Current state and perspective. Energies 2021, 14, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Shukla, S.K.; Wang, R. Enabling catalysts for biodiesel production via transesterification. Catalysts 2023, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezekannagha, C.B. , Onukwuli, O.D., Nwabueze, O.H.; Nnanwube, I.A. Heterogeneous base catalyst from hybrid banana-and-plantain peels in papaya seed oil (Carica papaya) methyl-ester synthesis. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 1935–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G.; Morgan, T.J. An overview of the organic and inorganic phase composition of biomass. Fuel 2012, 94, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Vassileva, C.G.; Vassilev, V.S. Advantages and disadvantages of composition and properties of biomass in comparison with coal: An overview. Fuel 2015, 158, 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; He, Y.; Yu, X.; Banks, S.W.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R.; Bridgwater, A.V. Review of physicochemical properties and analytical characterization of lignocellulosic biomass. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Oyedeji, O.; Leal, J.H.; Donohoe, B.S.; Semelsberger, T.A.; Li, C.; Hoover, A.N.; Webb, E.; Bose, E.A.; Zeng, Y.; Williams, C.L.; Schaller, K.D.; Sun, N. Ray, A.E.; Tanjore, D. Characterizing variability in lignocellulosic biomass: A review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8059–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Niu, Y.; Tan, H.; Wang, X. Short review on the origin and countermeasure of biomass slagging in grate furnace. Front. Environ. Res. 2014, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. Assessing slagging propensity of coal from their slagging indices. J. Energy Inst. 2018, 91, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, J.; Balas, M.; Lisy, M.; Lisa, H.; Milcak, P.; Elbl, P. An overview of slagging and fouling indicators and their applicability to biomass fuels. Fuel Process. Technol. 2021, 217, 106804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, F.; Su, X.; Behrendt, F.; Gao, Z.; Wang, H. Evaporation rate of potassium chloride in combustion of herbaceous biomass and its calculation. Fuel 2019, 257, 116021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori-Boateng, C.; Lee, K.T. The potential of using cocoa pod husks as green solid base catalysts for the transesterification of soybean oil into biodiesel: Effects of biodiesel on engine performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 220, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbenga, A.G.; Mohammed, A.; Ajakaye, O.N. Biodiesel production in Nigeria using cocoa pod ash as a catalyst base. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Investig. 2013, 2(15), 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Betiku, E.; Etim, A.O.; Pereao, O.; Ojumu, T.V. Two-Step Conversion of Neem (Azadirachta indica) Seed oil into fatty methyl esters using a heterogeneous biomass-based catalyst: An example of cocoa pod husk. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 6182–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odetoye, T.E.; Amusan, G.S. Cocoa pod ash as bio-based catalyst for biodiesel production from waste chicken fat. CIGR J. 2019, 21(4), 144–151. [Google Scholar]

- Odude, V.O.; Adesina, A.J.; Oyetunde, O.O.; Adeyemi, O.O.; Ishola, N.B.; Etim, A.; Betiku, E. Application of agricultural waste-based catalysts to transesterification of esterified palm kernel oil into biodiesel: A case of banana fruit peel versus cocoa pod husk. Waste Biomass Valor. 2019, 10, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatundun, E.A.; Borokini, O.O.; Betiku, E. Cocoa pod husk-plantain peel blend as a novel green heterogeneous catalyst for renewable and sustainable honne oil biodiesel synthesis: A case of biowastes-to-wealth. Renew. Energy 2020, 166, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, T.F.; Eyibio, U.; Emberru, E.R.; Balogun, T.A. Optimization conversion of beef tallow blend with waste used vegetable oil for fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) synthesis in the presence of bio-base derived from Theobroma cacao pod husks. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falowo, A.O.; Betiku, E. A novel heterogeneous catalyst synthesis from agrowastes mixture and application in transesterification of yellow oleander-rubber oil: Optimization by Taguchi approach. Fuel 2022, 312, 122–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatayo, O.A.; Sunday, O.D.; Olaluwoye, O.S. Production and characterization of biodiesel from castor seed oil using cocoa pod ash as catalyst. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2024, 47, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarigan, J.B.; Perangin-angin, S.; Debora, S.; Manalu, D.; Sari, R.N.; Ginting, u.; Sitepu, E.K. Application of waste cocoa pod husks as a heterogeneous catalyst in homogenizer-intensified biodiesel production at room temperature. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betiku, E.; Okeleye, A.A.; Ishola, N.B.; Osunleke, A.S.; Ojumu, T.V. Development of a novel mesoporous biocatalyst derived from kola nut pod husk for conversion of kariya seed oil to methyl esters: A Case of synthesis, modeling and optimization studies. Catal. Lett. 2019, 149, 1772–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil; U. P.; Patil, S.U. Enhanced biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using potash-enriched natural base catalyst. Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 5, 352–366. [Google Scholar]

- Vadery, V.; Narayanan, B.N.; Ramakrishnan, R.M.; Cherikkallinmel, S.K.; Sugunan, S.; Narayanan, D.P.; Sasidharan,S. Room temperature production of Jatropha biodiesel over coconut husk ash. Energy 2014, 70, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, P.U.; Wang, S.; Khanday, W.A.; Li, S.; Tang, T.; Zhang, L. Box-Behnken Optimization of the transesterification reaction of glycerol to glycerol carbonate on catalyst derived from calcined palm oil ash. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 2676–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changmai, B.; Sudarsanam, P.; Rokhum, S.L. Biodiesel production using a renewable mesoporous solid catalyst. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 145, 111911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.; Kalita, P.; Das, B.; Basumatary, S. Highly efficient renewable heterogeneous base catalyst derived from waste Sesamum indicum plant for synthesis of biodiesel. Renew. Energy 2020, 151, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, S.; Nath, B.; Das, B.; Kalita, P.; Basumatary, B. Utilization of renewable and sustainable basic heterogeneous catalyst from Heteropanax fragrans (Kesseru) for effective synthesis of biodiesel from Jatropha curcas oil. Fuel 2020, 286, 119357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldiehy, K.S.H.; Gohain, M.; Daimary, N.; Borah, D.; Mandal, M.; Deka, D. Radish (Raphanus sativus L.) leaves: A novel source for a highly efficient heterogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production using waste soybean cooking oil and Scenedesmus obliquus oil. Renew. Energy 2022, 191, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, I.M.; Orlando, A.R.L. Paes, O.A.R.L.; Maia, P.J.S.; Souza, M.P.; Almeida, R.A.; Silva, C.C.; Duvoisin, S.; de Freitas, F.A. New heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production from waste tucumã peels (Astrocaryum aculeatum Meyer): Parameters optimization study. Renew. Energy 2019, 130, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, S.D.S.; Pessoa, W.A.G.; Sá, I.S.C.; Takeno, M.L.; Nobre, F.X.; Pinheiro, W.; Manzato, L.; Iglauer, S. Bioresource Technology pineapple (Ananás comosus) leaves ash as a solid base catalyst for biodiesel synthesis. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 312, 123–569. [Google Scholar]

- Etim, A.O.; Musonge, P. Synthesis of a highly efficient mesoporous green catalyst from waste Avocado peels for biodiesel production from used cooking–baobab hybrid oil. Catalysts 2024, 14, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, A.O.; Betiku, E.; Ajala, S.O.; Olaniyi, P.J.; Ojumu, T.V. Potential of ripe plantain fruit peels as an ecofriendly catalyst for biodiesel synthesis: optimization by artificial neural network integrated with genetic algorithm. Sustainability 2018, 10, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, B.; Das, B.; Kalita, P.; Basumatary, S. Waste to value addition: Utilization of waste Brassica nigra plant derived novel green heterogeneous base catalyst for effective synthesis of biodiesel. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 239, 118112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohain, M.; Laskar, K.; Paul, A.K.; Daimary, N.; Maharana, M.; Goswami, I.K.; Hazarika, A.; Bora, U.; Deka, D. Carica papaya stem: A source of versatile heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production and C–C bond formation. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumari, K.; Rokhum, L. A sustainable protocol for production of biodiesel by transesterification of soybean oil using banana trunk ash as a heterogeneous catalyst. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2020, 10, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, G.; Das, D.; Rajkumari, K.; Rokhum, L. Exploiting waste: Towards a sustainable production of biodiesel using: Musa acuminata peel ash as a heterogeneous catalyst. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2365–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleman-Ramirez, J.L.; Moreira, J.; Torres-Arellano, S.; Longoria, A.; Okoye, P.U.; Sebastian, P.J. Preparation of a heterogeneous catalyst from moringa leaves as a sustainable precursor for biodiesel production. Fuel 2021, 284, 118–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keke, M.; Rockson-Itiveh, D.E.; Ozioko, F.C.; Adepoju, T.F. Hetero-alkali catalyst for production of biodiesel from domesticated waste: (used waste oil). ABUAD Int. J. Nat. Appl. Sci. 2023, 3(2), 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, T.F. Synthesis of biodiesel from Pig fat oil - Neem oil blend using the mixture of two agricultural wastes: palm kernel shell husk (PKSH) and fermented kola nut husk (FKNH). Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 149, 112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohain, M.; Devi, A.; Deka, D. Musa balbisiana Colla peel as highly effective renewable heterogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Shrivastava, S.; Sharma, V.; Srivastava, P.; Shankhwar, V.; Sharma, A.; Srivastava, S.K.; Agarwal, D.D. Karanja seed shell ash: A sustainable green heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, A.; Sankaranarayanan, P. Biodiesel production and parameter optimization: an approach to utilize residual ash from sugarcane leaf, a novel heterogeneous catalyst, from Calophylluminophyllum oil. Renew. Energy 2020, 153, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladinovic, M.R.; Zduji, M.V.; Veljovi, D.N.; Krsti, J.B.; Bankovi, I.B.; Veljkovi, V.B.; Stamenkovi, O.S. Valorization of walnut shell ash as a catalyst for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miladinovic, M.R.; Krstic, J.B.; Zdujic, M.V.; Veselinovic, L.M.; Veljovic, D.N.; Bankovic-Ilic, I.B.; Stamenkovic, O.S.; Veljkovic, V.B. Transesterification of used cooking oil catalyzed by hazelnut shell ash. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, E.K.L.; Gonçalves, M.A.; Da Luz, P.T.S.; Da Rocha Filho, G.N.; Zamian, J.R.; Da Conceiç, L.R.V. Acai seed ash as a novel basic heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel synthesis: optimization of the biodiesel production process. Fuel 2021, 299, 120887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouran, A.; Aghel, B.; Nasirmanesh, F. Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using wheat bran ash as a sustainable biomass. Fuel 2021, 295, 120542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.; Abdullah, M.O.; Hua, T.Y.; Nolasco-Hip´olito, C. Techno-economical and energy analysis of sunflower oil biodiesel synthesis assisted with waste ginger leaves derived catalysts. Renew. Energy 2021, 168, 815–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| K-containing salt | Melting temperature (°C) | Boiling temperature (°C) |

| Potassium bicarbonate, KHCO3 |

> 100 (decomposition) | NA |

|

Potassium carbonate, K2CO3 |

891 | NA |

|

Potassium chloride, KCl |

770 | 1,413 |

|

Potassium fluioride, KF |

846 | 1,505 |

|

Potassium hydroxide, KOH |

406 | 1320 |

|

Potassium nitrate, KNO3 |

334 | 400 (decomposition) |

|

Potassium oxide, K2O |

400 | NA |

|

Potassium phosphate, K3PO4 |

253 | 450 |

| Potassium silicate, K2SiO3 |

> 300 | NA |

|

Potassium sulfate, K2SO4 |

1,069 | 1,687 |

| Potassium Sulfide, K2S |

400 | NA |

| Biomass type | Chemical ash composition (wt%) | Sum (wt%) | |||||||||

| SiO2 | CaO | K2O | P2O5 | Al2O3 | MgO | Fe2O3 | SO3 | Na2O | TiO2 | ||

| Bamboo whole | 9.92 | 4.46 | 53.38 | 20.33 | 0.67 | 6.57 | 0.67 | 3.68 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 100.00 |

| Bana grass | 38.59 | 4.09 | 49.08 | 3.14 | 0.92 | 1.96 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 100.00 |

| Buffalo gourd grass | 8.73 | 14.74 | 41.40 | 10.96 | 1.88 | 5.24 | 0.90 | 9.89 | 6.20 | 0.06 | 100.00 |

| Alfalfa straw | 7.87 | 24.87 | 38.14 | 10.38 | 0.10 | 14.10 | 0.41 | 2.62 | 1.49 | 0.02 | 100.00 |

| Mint straw | 23.49 | 17.63 | 32.01 | 5.77 | 5.57 | 6.90 | 2.82 | 3.50 | 1.98 | 0.33 | 100.00 |

| Almond hulls | 11.21 | 9.75 | 63.90 | 6.17 | 2.52 | 4.00 | 0.92 | 0.41 | 1.06 | 0.06 | 100.00 |

| Almond shells | 16.96 | 11.55 | 53.48 | 4.93 | 2.99 | 4.51 | 2.78 | 0.93 | 1.76 | 0.11 | 100.00 |

| Coffee husks | 14.65 | 13.05 | 52.45 | 4.94 | 7.07 | 4.32 | 2.06 | 0.53 | 0.66 | 0.27 | 100.00 |

| Cotton husks | 10.93 | 20.95 | 50.20 | 4.05 | 1.32 | 7.59 | 1.92 | 1.72 | 1.31 | 0.01 | 100.00 |

| Grape marc | 9.53 | 28.52 | 36.84 | 8.80 | 2.63 | 4.77 | 1.77 | 6.29 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 100.00 |

| Olive residue | 22.26 | 12.93 | 42.79 | 6.09 | 4.10 | 5.84 | 1.99 | 3.73 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 100.00 |

| Pepper residue | 15.39 | 10.02 | 35.32 | 11.19 | 8.39 | 4.55 | 3.38 | 10.61 | 1.05 | 0.10 | 100.00 |

| Plum pits | 3.64 | 14.86 | 45.51 | 20.40 | 0.11 | 11.79 | 0.69 | 2.51 | 0.47 | 0.02 | 100.00 |

| Soya husks | 2.01 | 25.26 | 36.00 | 5.79 | 8.74 | 8.38 | 2.95 | 4.37 | 6.26 | 0.24 | 100.00 |

| Sunflower husks | 23.66 | 15.31 | 28.53 | 7.13 | 8.75 | 7.33 | 4.27 | 4.07 | 0.80 | 0.15 | 100.00 |

| Walnut blows | 6.41 | 27.64 | 34.67 | 10.28 | 2.25 | 14.34 | 1.05 | 2.33 | 0.92 | 0.11 | 100.00 |

| Walnut hulls & blows | 8.29 | 20.03 | 39.65 | 7.52 | 2.92 | 16.21 | 1.37 | 2.71 | 1.19 | 0.11 | 100.00 |

| Walnut shells | 23.32 | 16.72 | 33.03 | 6.21 | 2.40 | 13.51 | 1.50 | 2.20 | 1.00 | 0.10 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).