Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

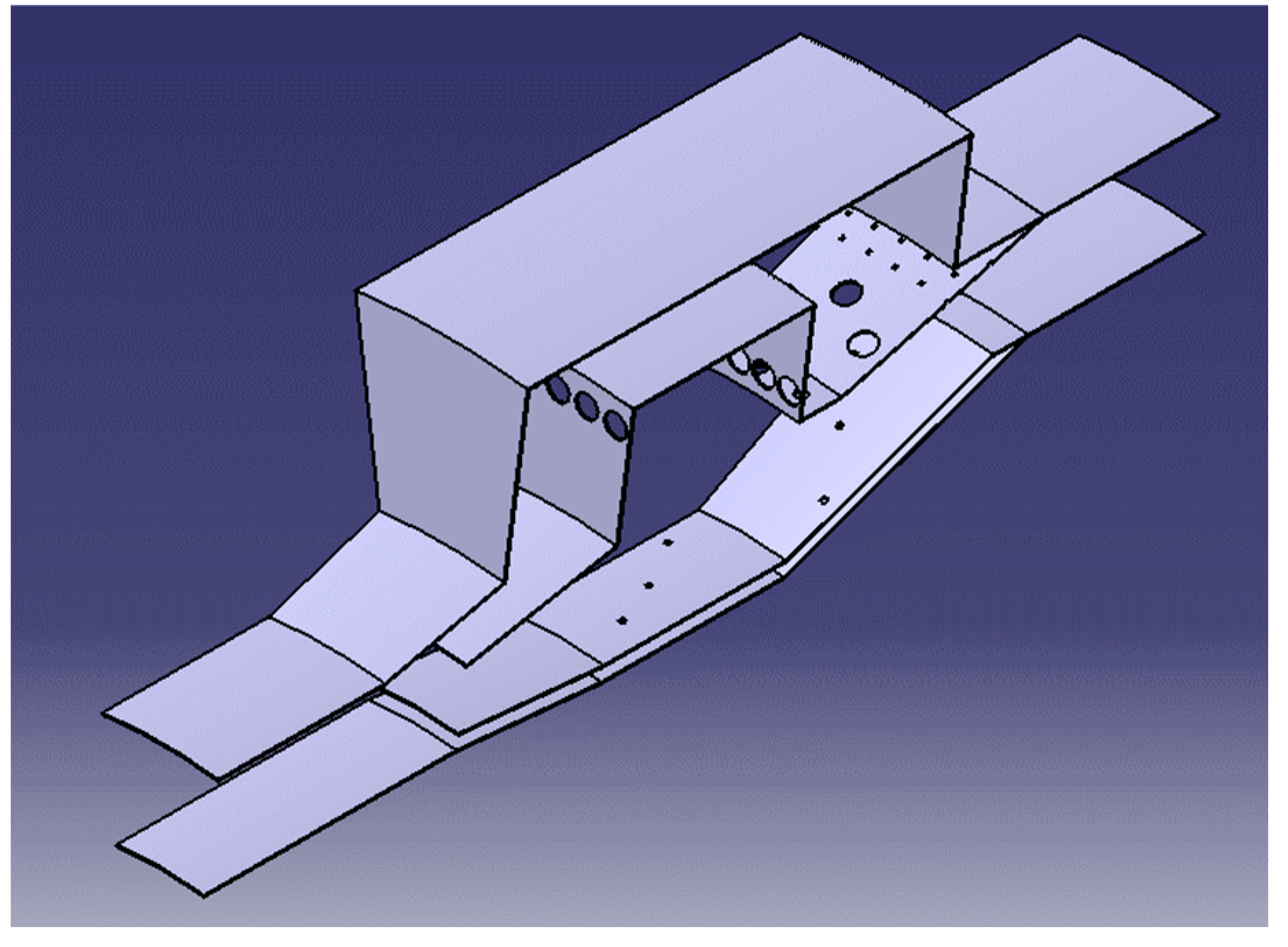

2. Materials and Methods

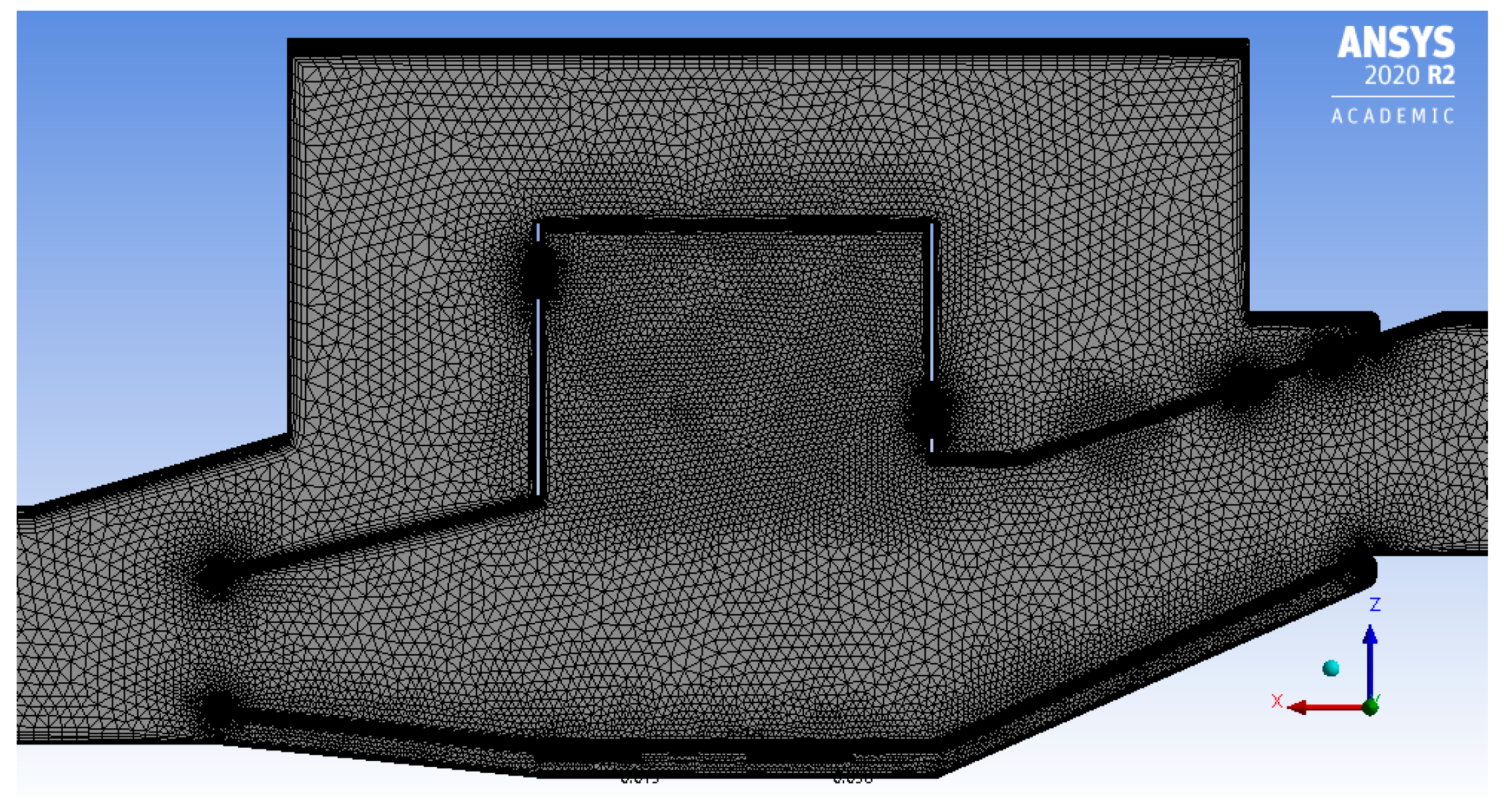

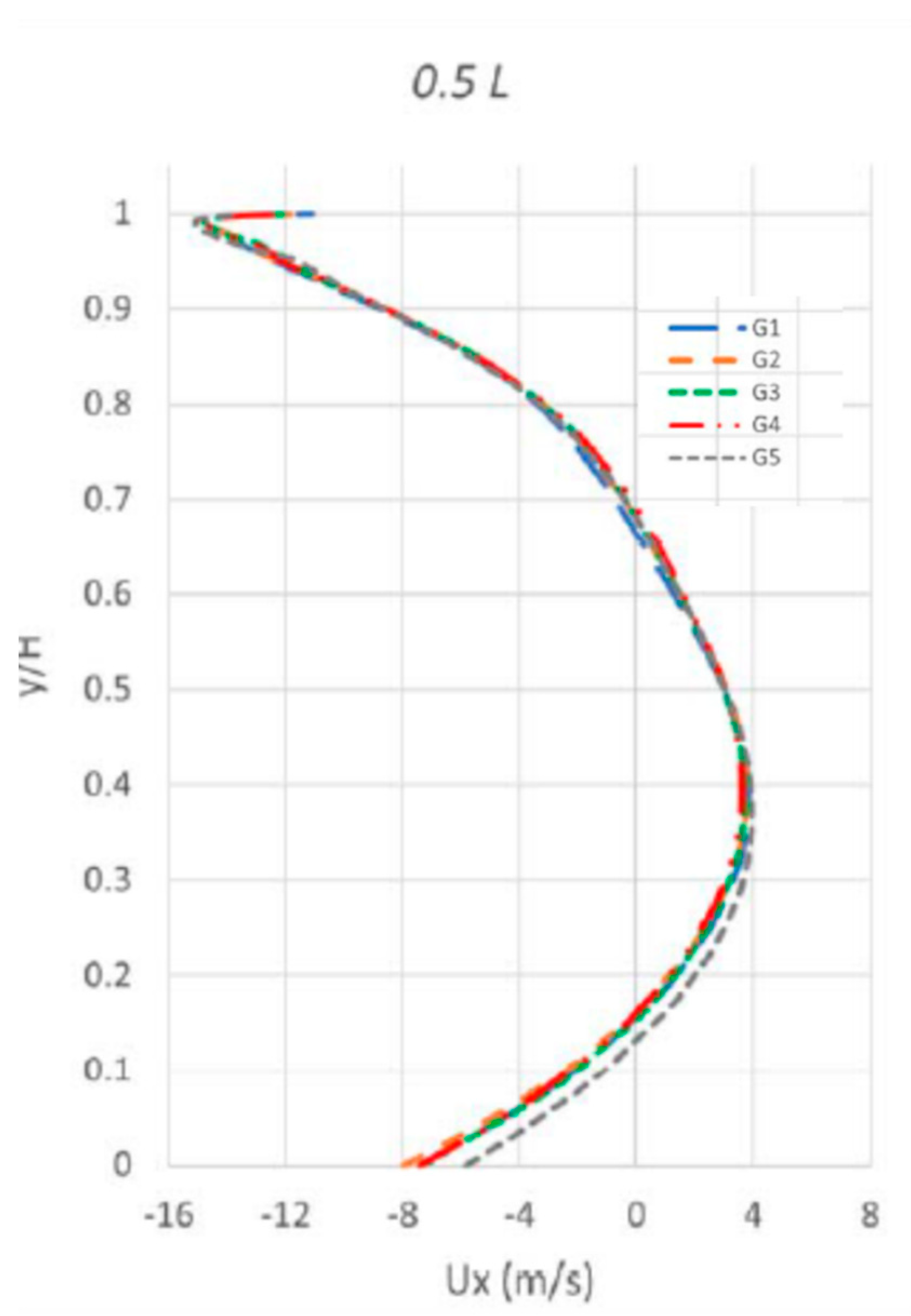

Numerical Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

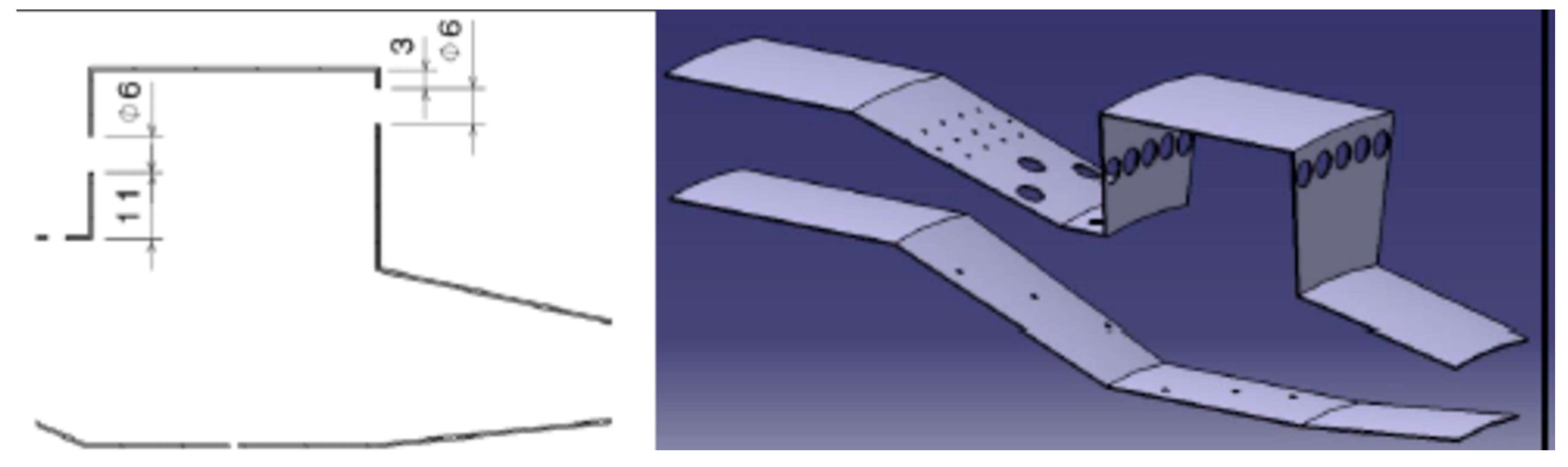

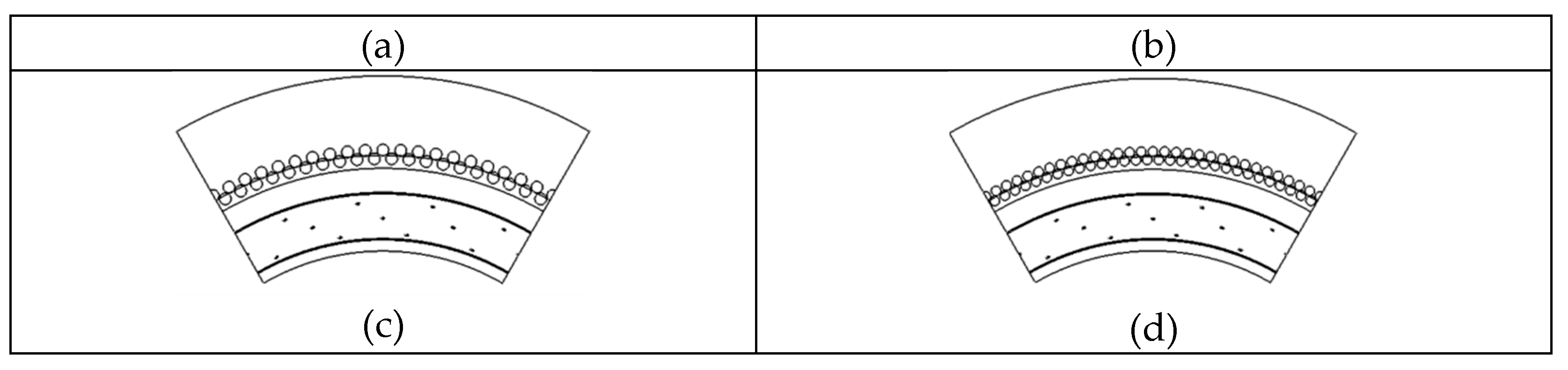

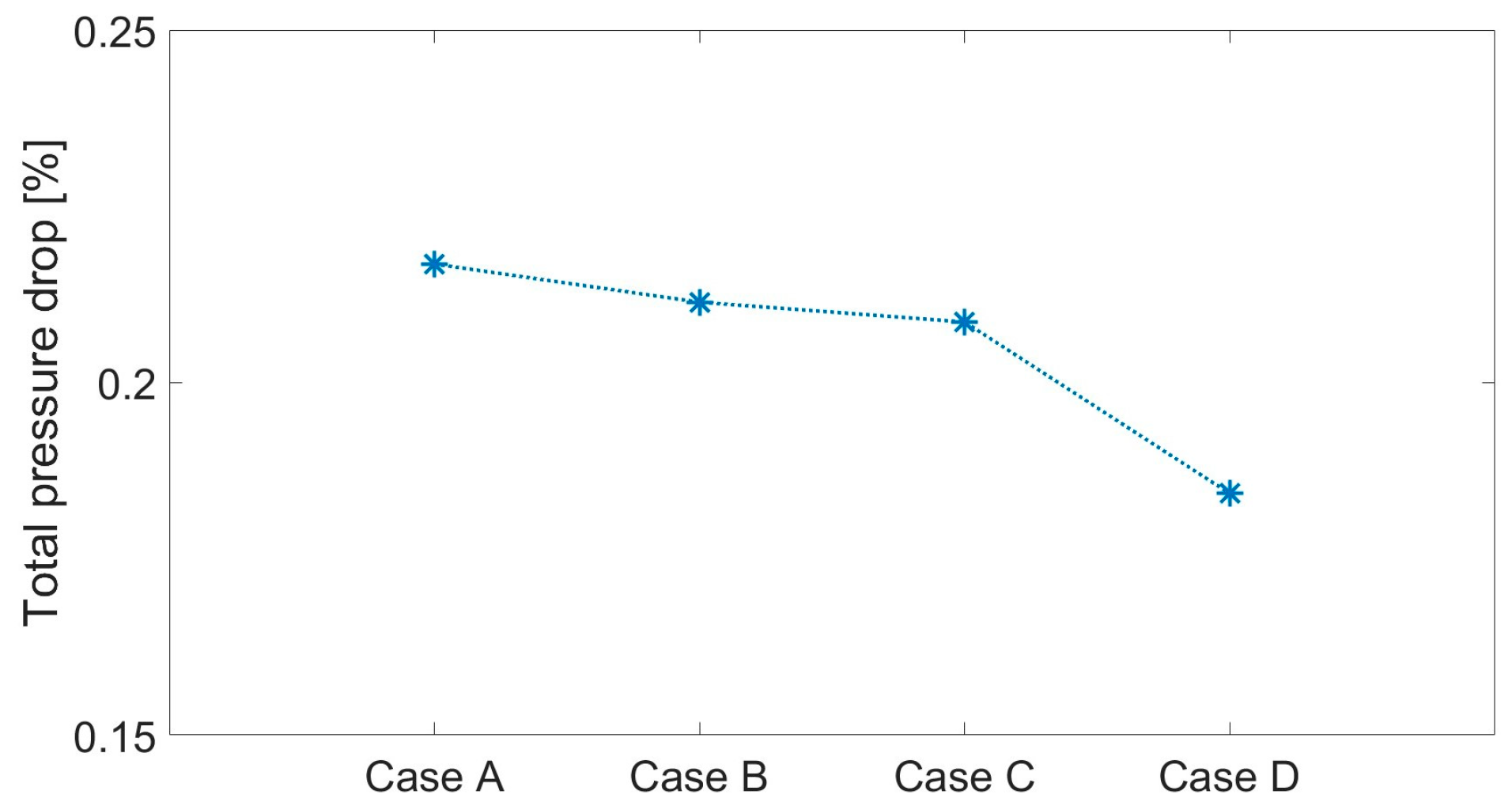

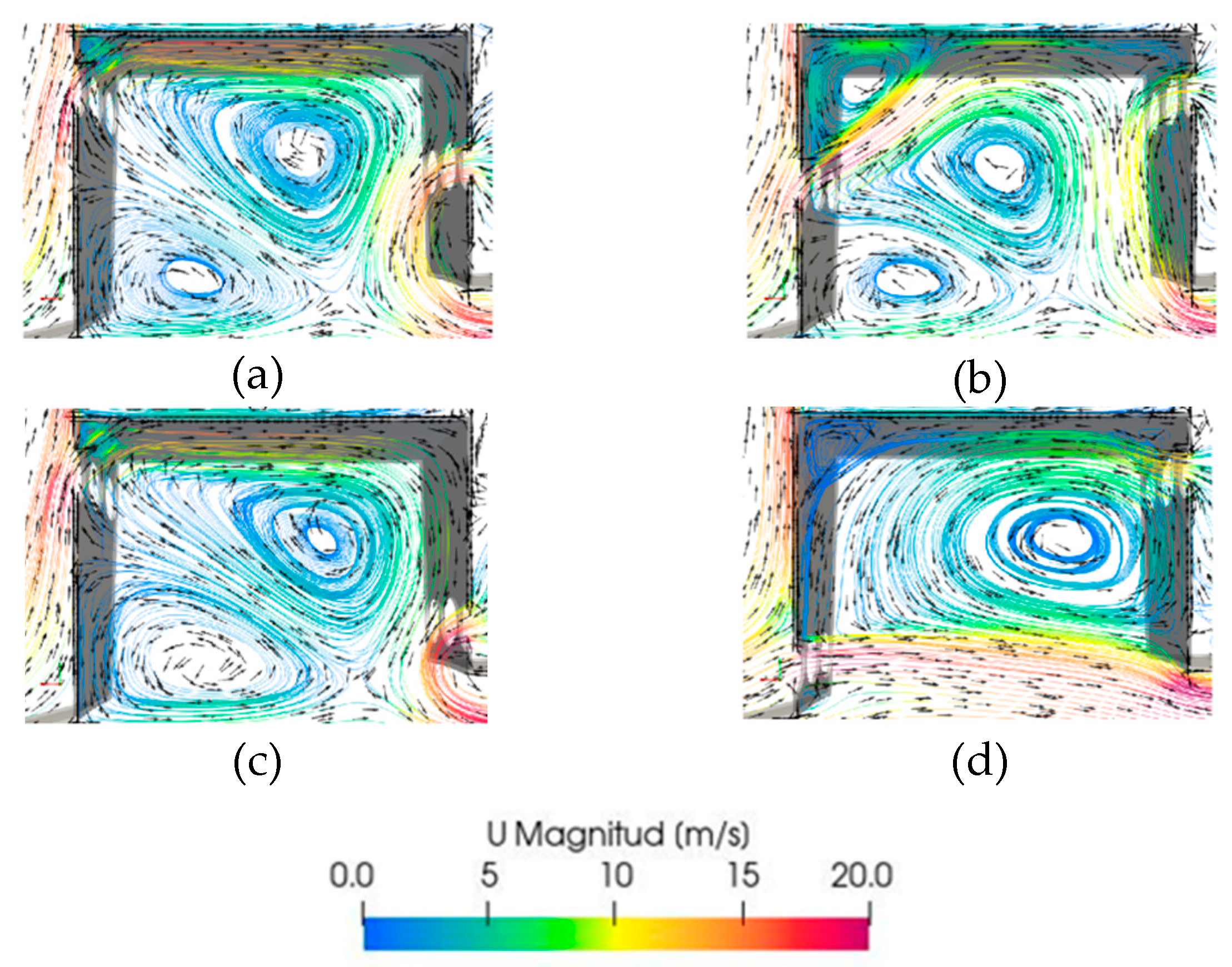

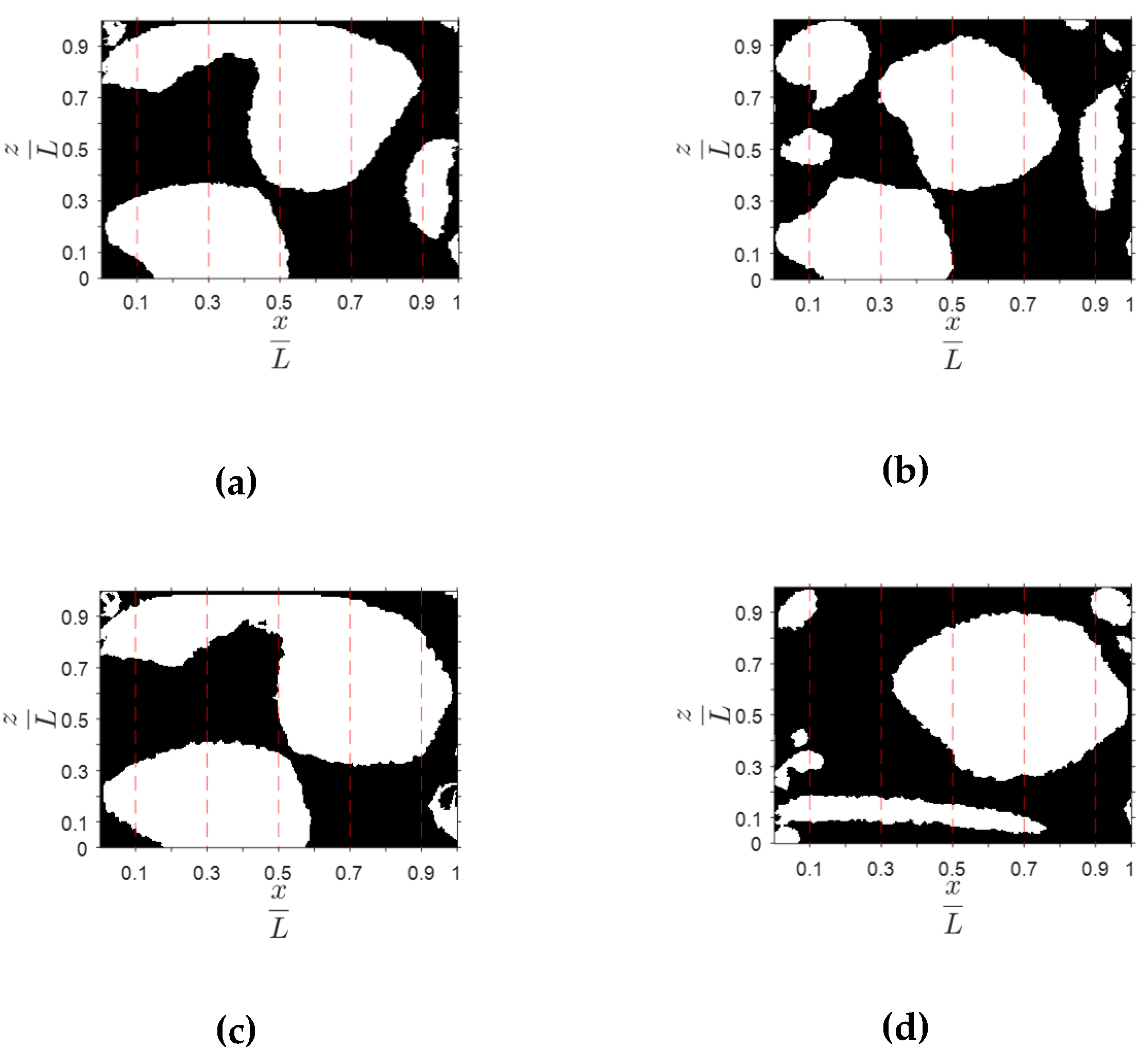

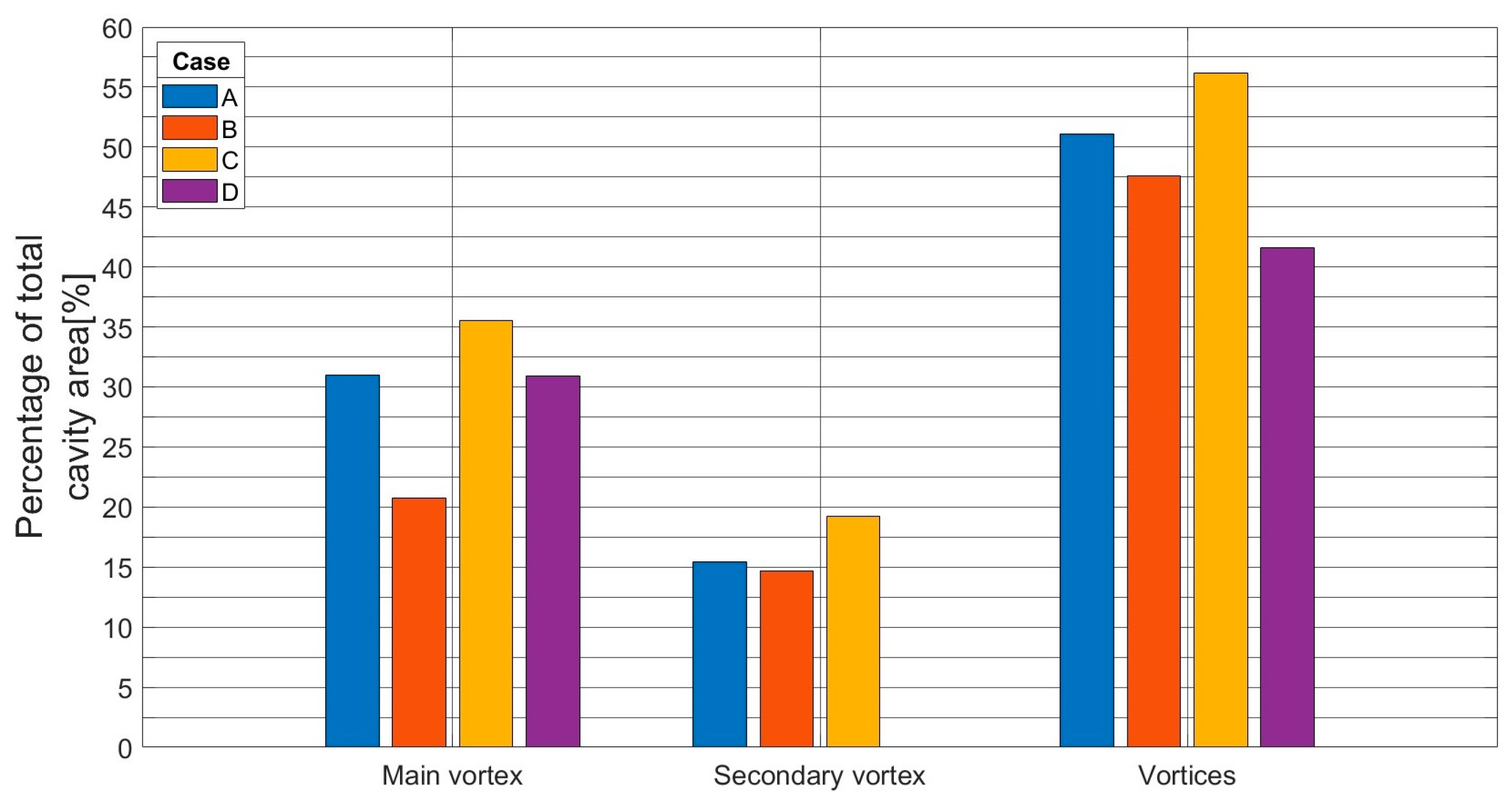

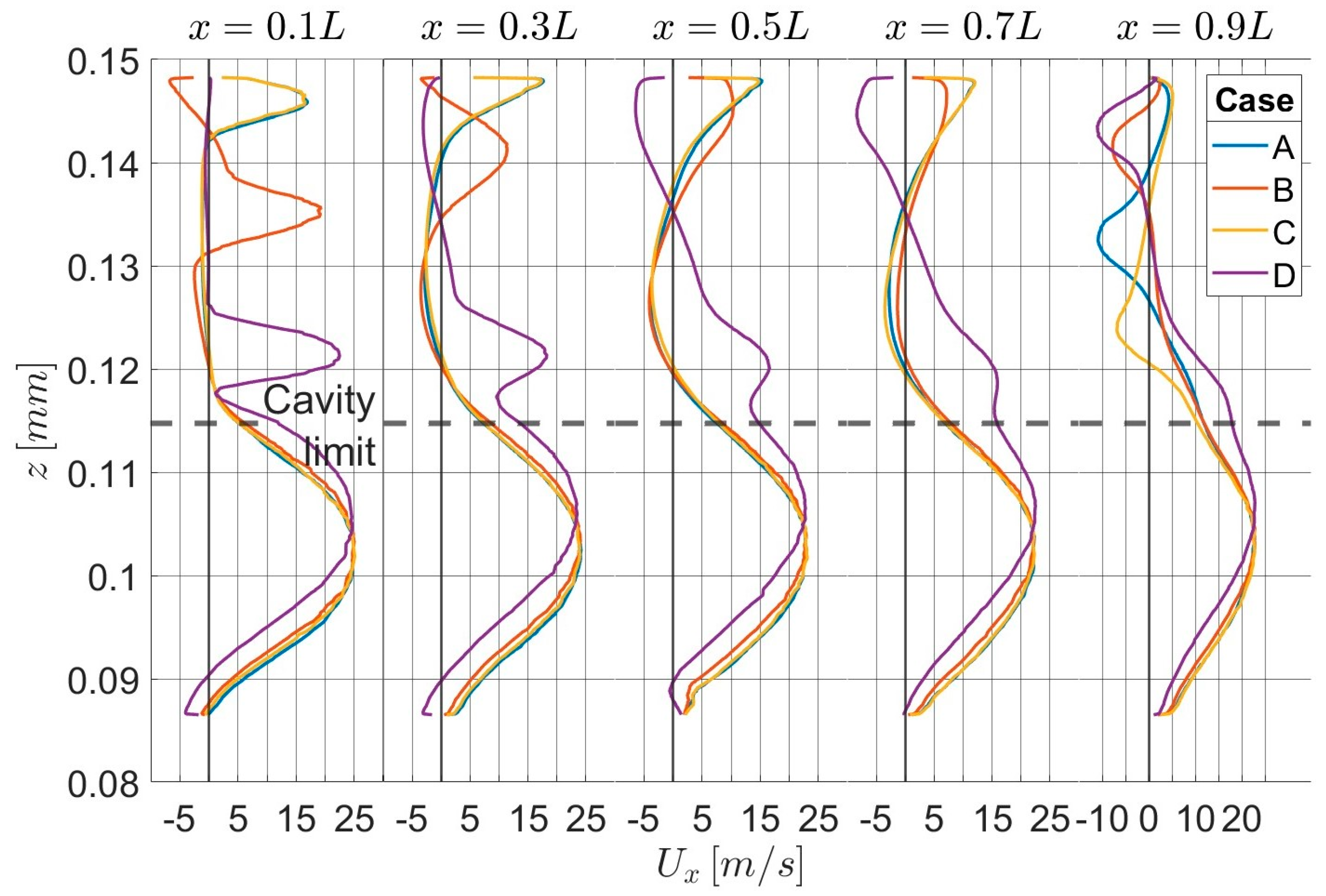

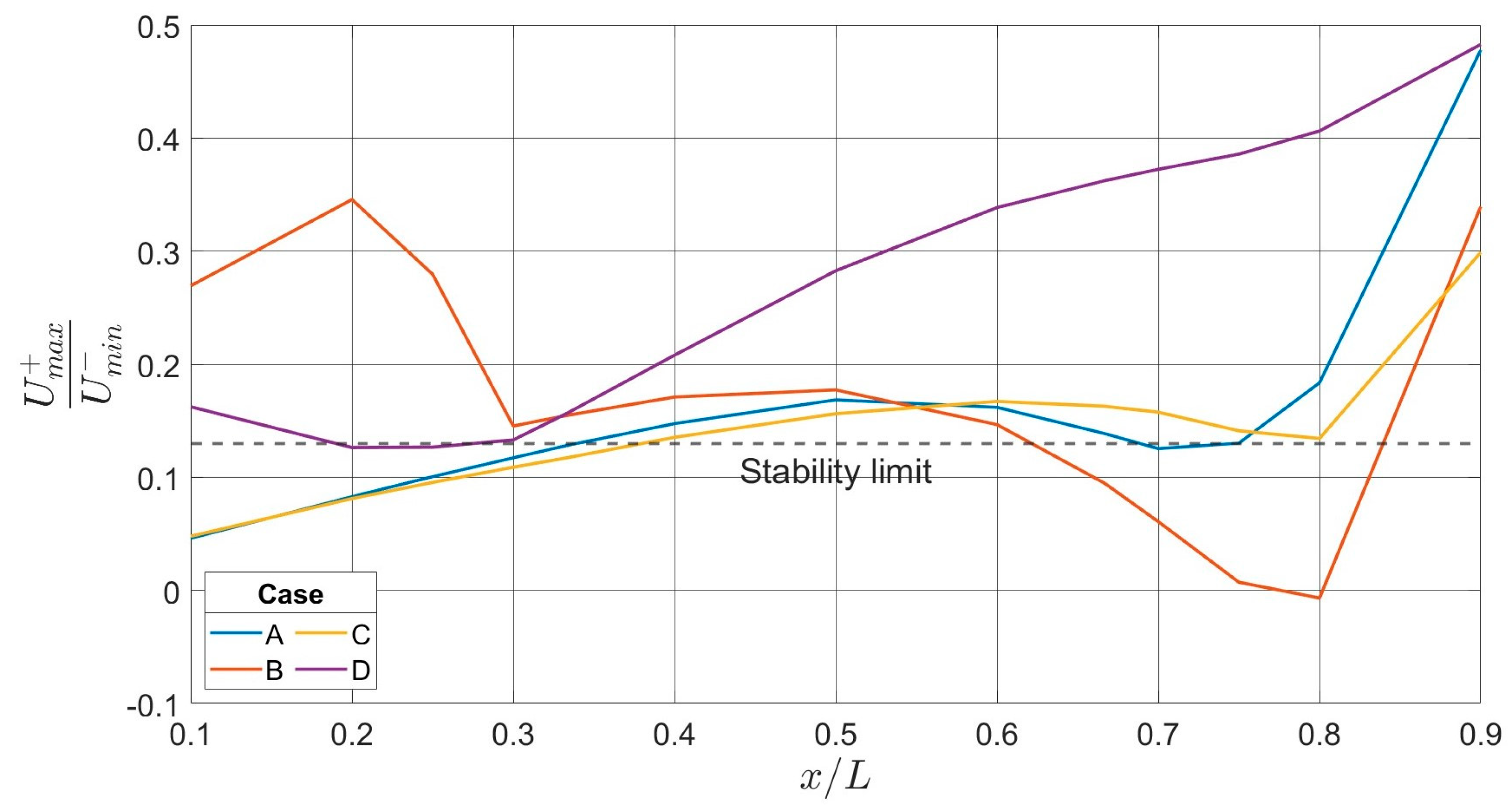

3.1. Results and Discussion for Cases A, B, C, D.

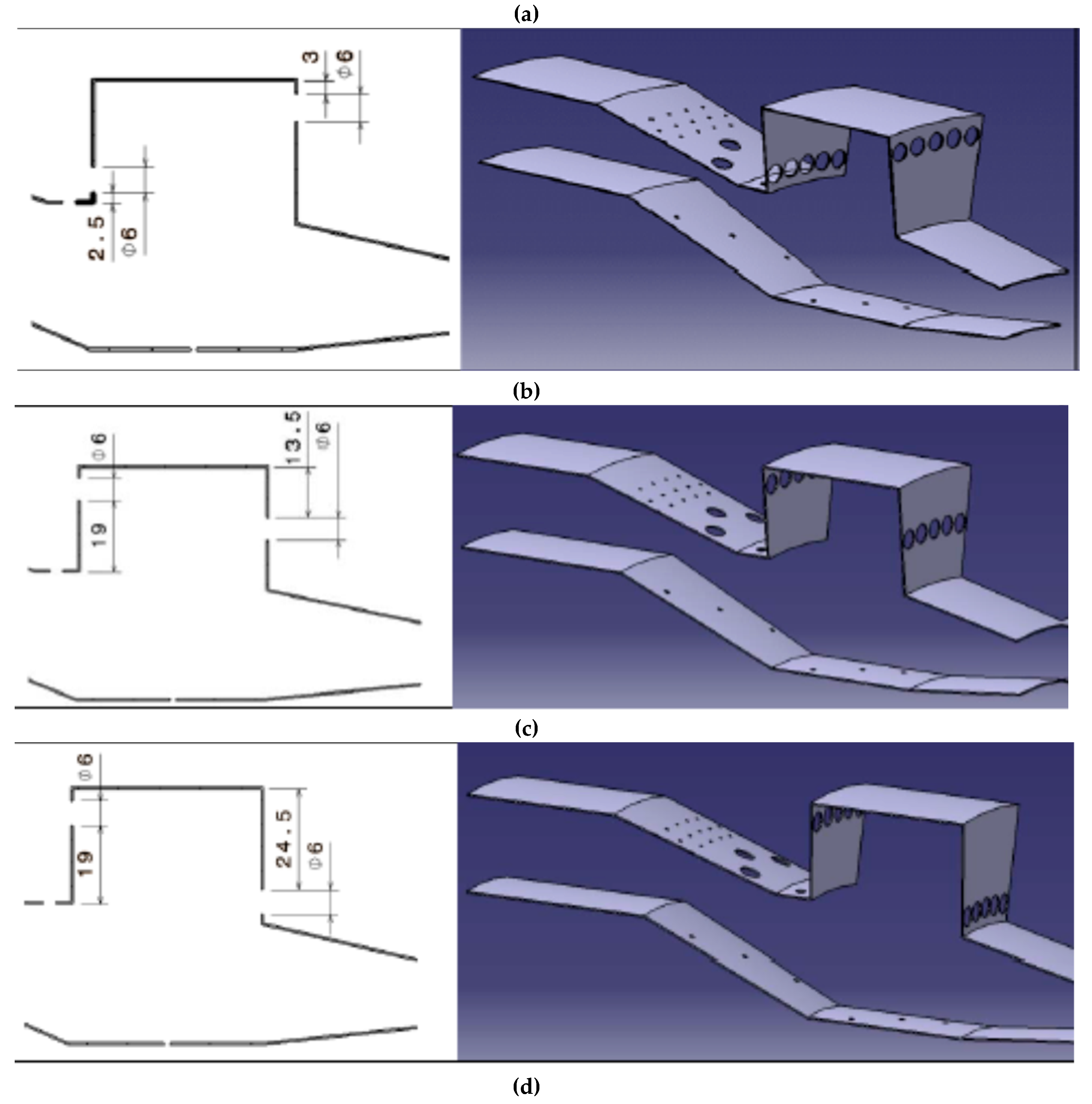

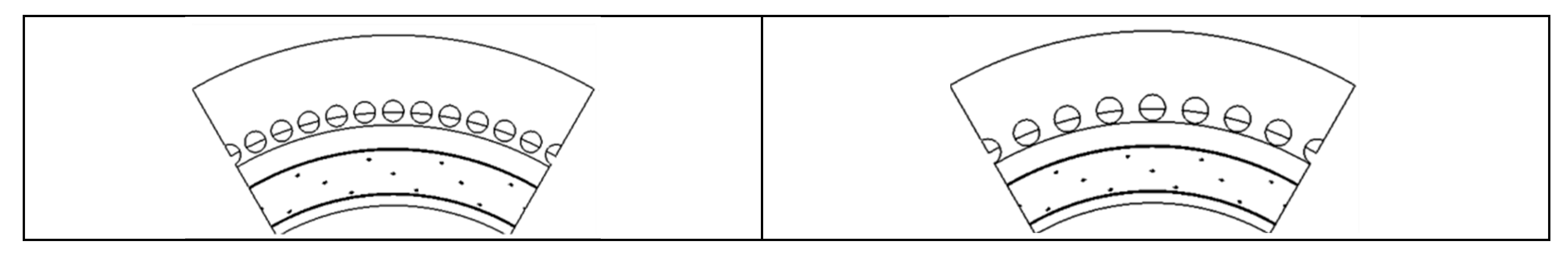

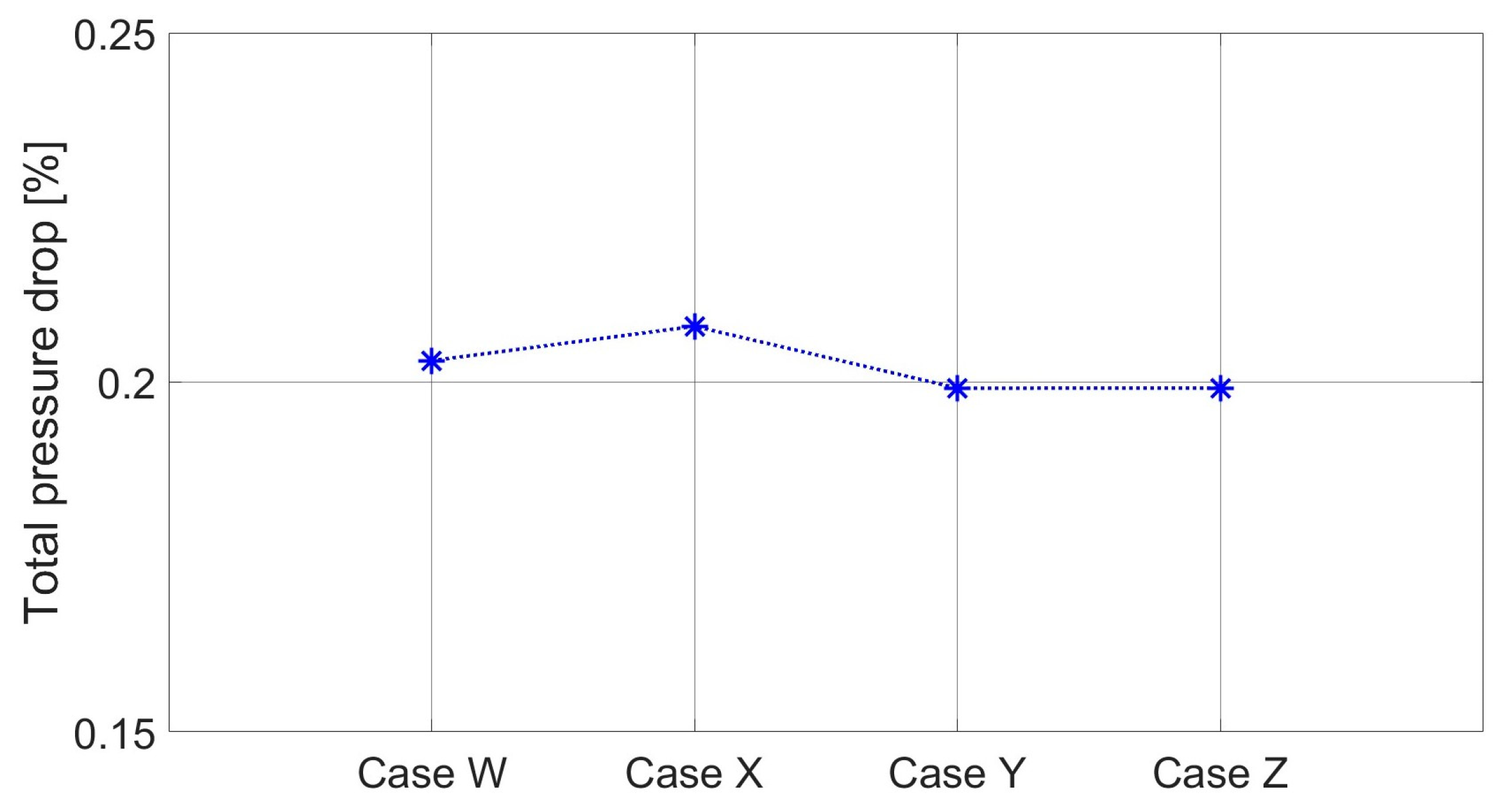

3.2. Results and Discussion for Cases W, X, Y, Z.

4. Conclusions

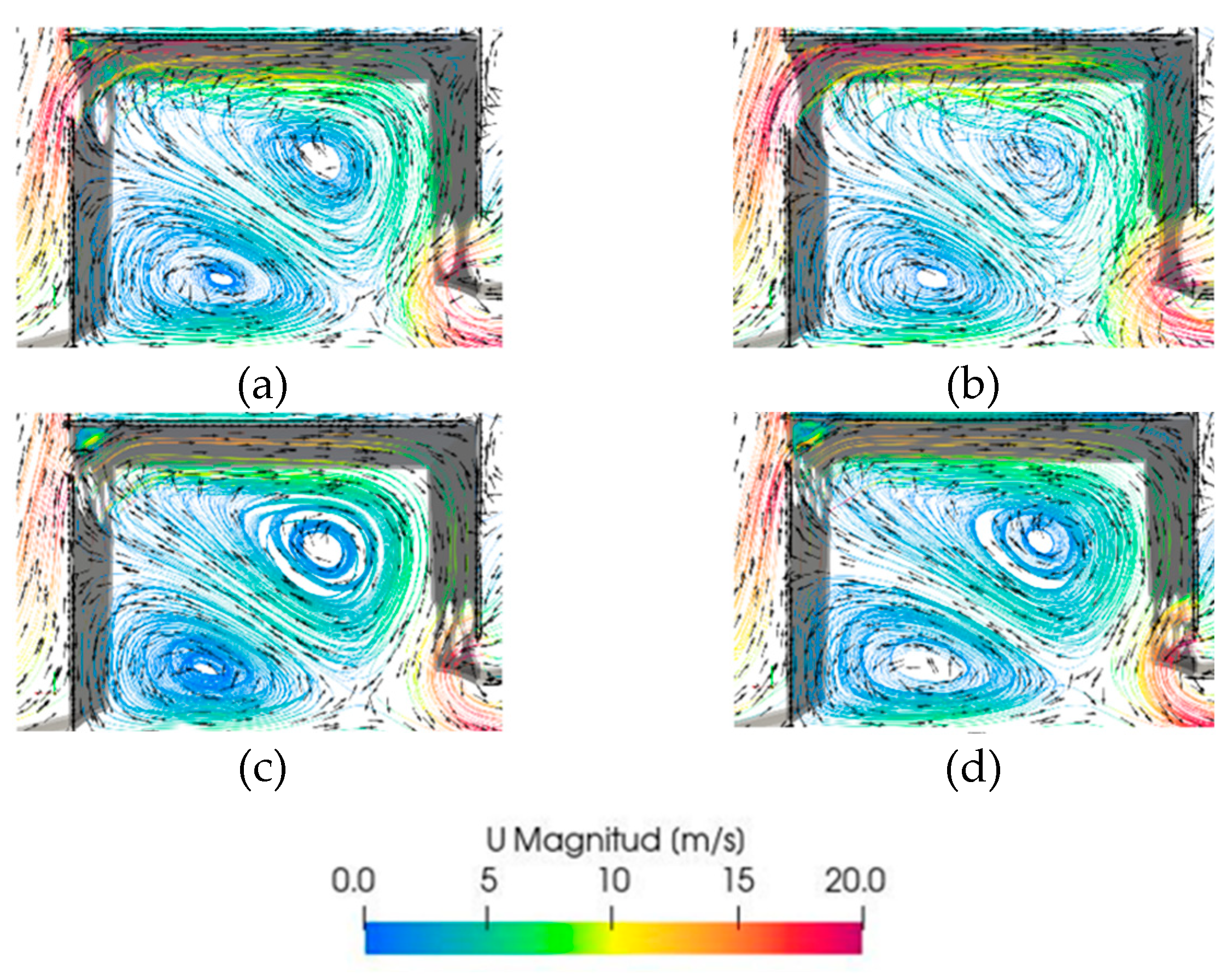

- When the air injection holes are located at the top of the fore wall of the TVC (Cases A and C) two recirculation zones are presented in the cavity. Even more, this location allows the biggest vortex in the cavity.

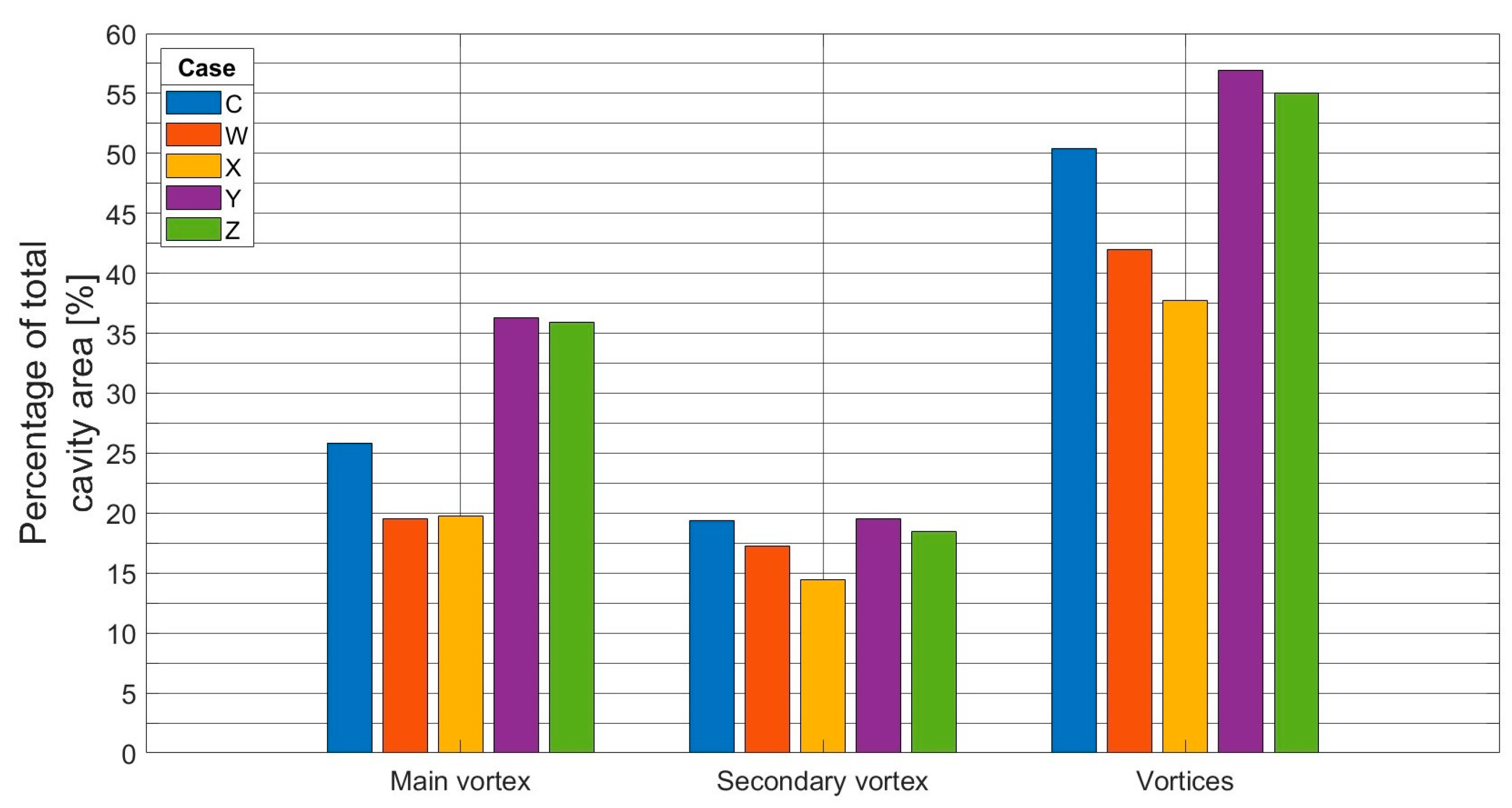

- The area occupied by the main vortex in the cavity diminishes if the diameter for the airflow holes increases. The Y configuration with diameter of 0.0042mm produces the largest vortex.

- Only changing the diameter in the airflow injection holes does not impact the position and size of the secondary vortex.

- Augmenting the diameter size of the airflow injection holes produces a higher portion of mass flow in the cavity.

- The flow distribution for the Y case is the most optimal for a RQL operation scheme.

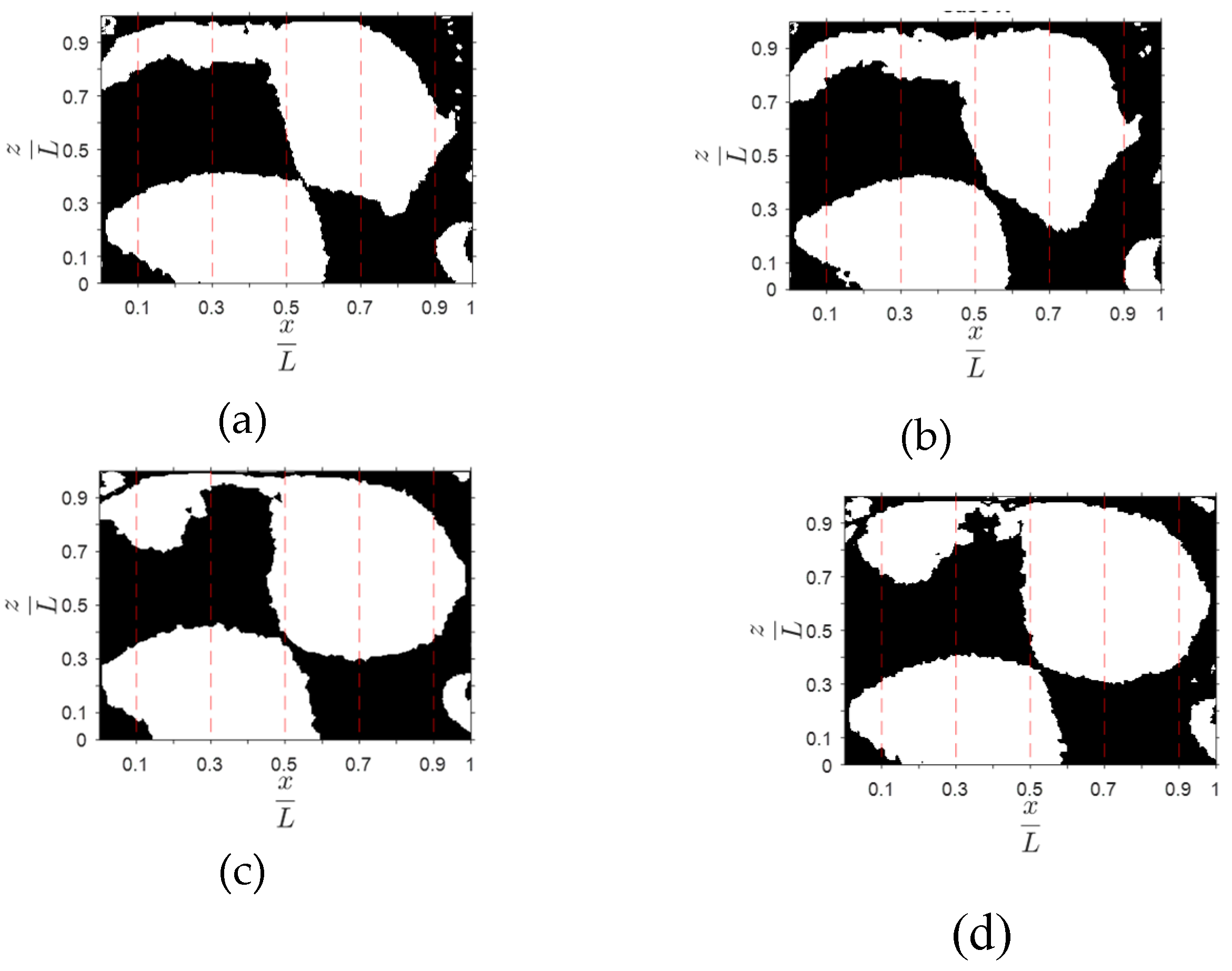

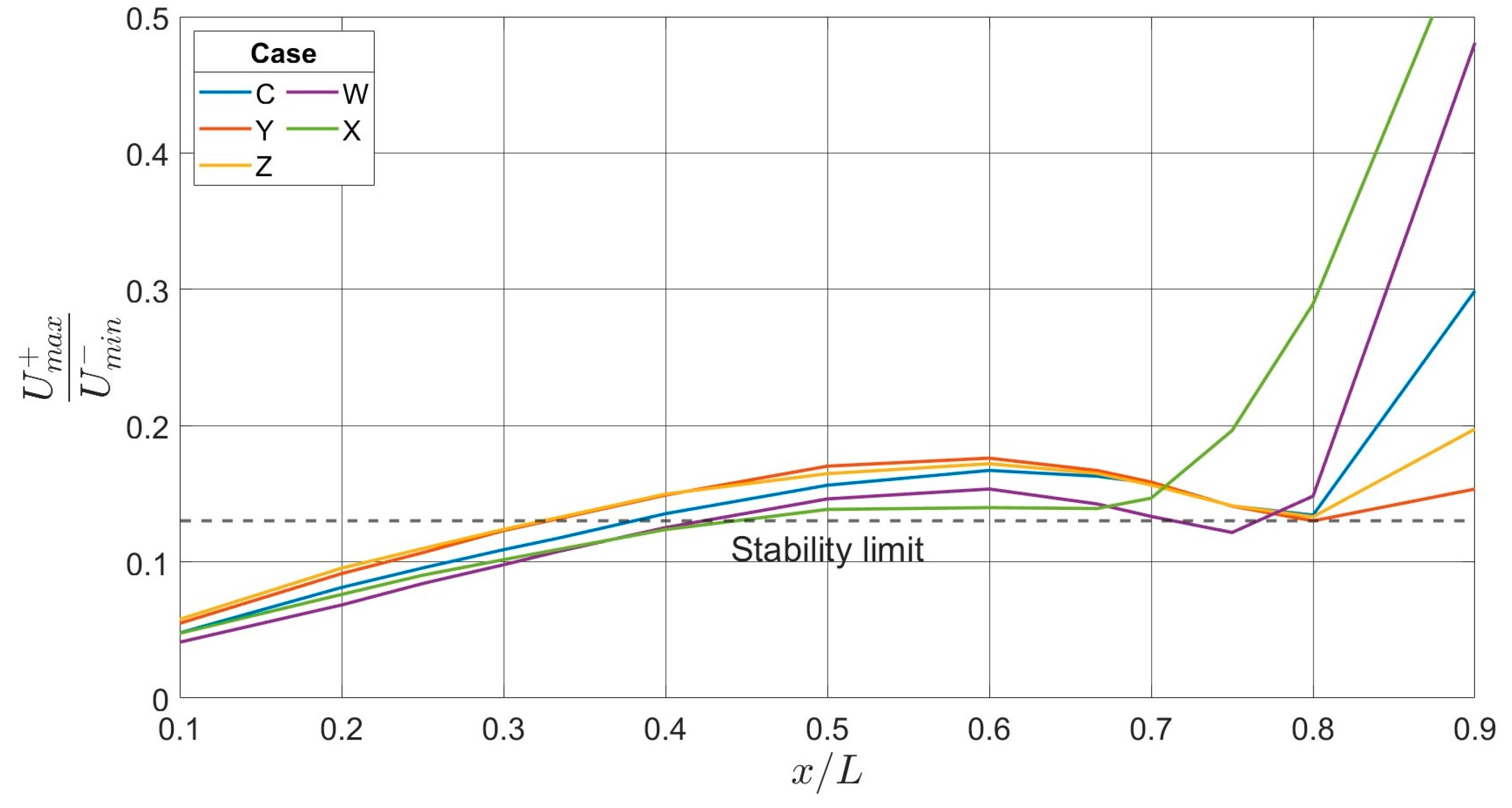

- The recirculation zone does not remain annularly for higher diameter air flow injection holes, contrary, if many small holes are occupied the vortex conserve their flow structure in the cavity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Y. Jin, Y. Li, X. He, J. Zhang, B. Jiang, Z. Wu, Y. Song. Experimental investigations of flow field and combustion characteristics of a model trapped vortex combustor. Appl. Energy. 2014, 134, pp- 257-269. doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.08.029.

- F. Xing, S. Zhang, P. Wang, W. Fan. Experimental investigation of a single trapped-vortex combustor with a slight temperature raise. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2010, 14 (7), pp. 520–525. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jin, X. He, J. Zhang, B. Jiang, Z. Wu. Experimental study on emission performance of an LPP/TVC. Chinese J. Aeronaut. 2012, 25, pp. 335–341. [CrossRef]

- Singhal and R.V. Ravikrishna. Single cavity trapped vortex combustor dynamics-Part 1: Experiments. Int. J. Spray and Combustions Dynamics. 2011, 3 (1), pp. 23-44. [CrossRef]

- 5 V.R. Katta, W.M. Roquemore. Numerical studies on trapped-vortex concepts for stable combustion, ASME-Turbo Asia Conference (1996).

- M. Li, X. He, Y. Zhao, Y. Jin, K. Yao, Z. Ge. Performance enhancement of a trapped-vortex combustor for gas turbine engines using a novel hybrid-atomizer. Appl. Energy. 2018, 216, pp. 286–295. [CrossRef]

- P.K. Ezhil Kumar, D.P. Mishra. Numerical simulation of cavity flow structure in an axisymmetric trapped vortex combustor. Aerospace Science and Technology. 2012, 21, pp. 16-23. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhu, Y. Jin, X. He. Effects of location and angle of primary injection on the cavity flow structure of a trapped vortex combustor model. Optik. 2019, 180, pp. 699–712. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Zhang, F. Hao, W. J. Fan. Combustion and stability characteristics of ultra-compact combustor using cavity for gas turbines. Appl. Energy. 2018, 225, pp. 940–954. [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, W. Fan. Experimental study of entrainment phenomenon in a trapped vortex combustor. Chinese J. Aeronaut. 2013, 26(1) pp. 63–73. [CrossRef]

- Singhal, R.V. Ravikrishna. Single cavity trapped vortex combustor dynamics-Part 2: Simulations. International Journal of Spray and Combustions Dynamics. 2011, 3(1) pp. 45-62. [CrossRef]

- D. Zhao, E. Gutmark, P. de Goey. A review of cavity-based trapped vortex, ultra-compact, high-g, inter-turbine combustors. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 66, pp. 42–82. [CrossRef]

- F. Xing, P. Wang, S. Zhang, J. Zou, Y. Zheng, R. Zhang, W. Fan. Experiment and simulation study on lean blow-out of trapped vortex combustor with various aspect ratios. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2012, 18, pp. 48–55. [CrossRef]

- L. Yu-ying, L. Rui-ming, L. He-xia, Y. Mao-lin. Effects of Fuelling Scheme on the Performance of a Trapped Combustor Rig, 45th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference (2009).

- D. L. Burrus, W. M. Roquemore, A. W. Johnson, D. T. Shouse. Performance Assesssment of a Prototype Trapped Vortex Combustor Concept for Gas Turbine Application, ASME-IGTI, (2001).

- W. M. Roquemore, D. Shouse, D. Burrus, et al. Trapped vortex combustor concept for gas turbine engines, 39th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, (2001). [CrossRef]

- R. Zhang, W. Fan, Q. Shi, W. Tan. Structural design and performance experiment of a single vortex combustor with single-cavity and air blast atomisers. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2014, 39 pp. 95–108. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Mishra, R. Sudharshan. Numerical analysis of fuel-air mixing in a two-dimensional trapped vortex combustor. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2010, 224 (1), pp. 65–75. [CrossRef]

- J-N. Reddy, N.K. Anand, P. Roy. Finite Element and Finite Volume Methods for Heat Transfer and Fluid Dynamics. Cambridge University Press, UK, 2023; pp.

- P. J. Roache. Quantification of uncertainty in computational fluid dynamics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1997, 29, pp. 123–160. [CrossRef]

- I. B. Celik, U. Ghia, P. J. Roache, C. J. Freitas, H. Coleman, P. E. Raad. Procedure for estimation and reporting of uncertainty due to discretization in CFD applications. J. Fluids Eng. Trans. ASME. 2008, 130(7), pp. 0780011–0780014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jin, X. He, J. Zhang, B. Jiang, y Z. Wu. Numerical investigation on flow structures of a laboratory-scale trapped vortex combustor. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 66(1-2), pp. 318–327. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, X. He, Y. Zhao, Y. Jin, Z. Ge, Y. Sun. Dome structure effects on combustion performance of a trapped vortex combustor. Appl. Energy, 2017, 208, pp. 72–82. [CrossRef]

- S. Vengadesan, C. Sony. Enhanced vortex stability in trapped vortex combustor. Aeronaut. J., 2010, 114 (1155) pp. 333–337. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Lefebvre, D. R. Ballal. Gas Turbine Combustions: Alternative Fuels and Emissions. CRC Press. USA, 2010.

- K. K. Agarwal, R. V. Ravikrishna. Experimental and numerical studies in a compact trapped vortex combustor: Stability assessment and augmentation. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2011, 183, pp. 1308–1327. [CrossRef]

- G. S. Elliott, M. Samimy. Compressibility effects in free shear layers. Phys. Fluids A. 1990, 2(7) pp. 1231–1240. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Configuration | Holes by row | |

|---|---|---|

| Original | ||

| W | ||

| X | ||

| Y | ||

| Z |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Element size | |

| Growing rate | |

| Minimum number of cells in the aperture | |

| Skewness | |

| Inflation methods | |

| Inflation layers |

| G1 | G2 | G3 | CG4 | G5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | 7,195,663 | 6,589,762 | 5,863,447 | 5,020,880 | 4,289,118 |

| Negative cells | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Orthogonality | 0.152 | 0.15 | 0.153 | 0.15 | 0.158 |

| Maximum skewness | 0.839 | 0.841 | 0.85 | 0.847 | 0.849 |

| Computing time | 12.92 ℎrs | 11.46 ℎrs | 7.80 ℎrs | 7.4 ℎrs | 7.19 ℎrs |

| Holes diameter | |||||

| Number of holes in the cavity | |||||

| Primary mass flow | |||||

| Secondary mass flow | |||||

| Mass flow through the cavity by the holes | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).