1. Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the deadliest cancers in the world, spotlighting the need for improved therapeutics to combat this disease. The chance of developing lung cancer in one’s lifetime is 1 in 16.5. Around 234,580 cases of lung cancer are diagnosed each year in just the U.S. alone (Lung Cancer Statistics | How Common Is Lung Cancer?, n.d.). When a lung tumor develops, its cancer cells can travel through the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to seed new tumors in other tissues, known as metastasis. Some common sites of metastasis are the liver, bones, brain, and adrenal glands (Where Does Metastatic Lung Cancer Spread To?, n.d.).

Of the 234,580 cases of lung cancer diagnosed in the U.S. over 125,070 were lethal (Lung Cancer Statistics | How Common Is Lung Cancer?, n.d.). The survival rate is dependent on two factors: the type of lung cancer and the location of the tumor. Localized lung cancer is within the lungs, while distant lung cancer spreads to other distant parts of the body. The 5-year survival rate of localized non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was 64%, while the distant survival rate was only 8%; the 5-year survival rate of localized small cell lung cancer (SCLC) was 29%, while the distant survival rate was only 3% (Lung Cancer Survival Rates | 5-Year Survival Rates for Lung Cancer, n.d.).

There are two primary reasons why lung cancer is so deadly. Firstly, the disease is hard to detect. Patients are usually asymptomatic in the early stages and can live with lung cancer for years without noticing a change. Because of this, when the symptoms start showing, the cancer has often already metastasized to other parents of the body, making treatment much more difficult (Lung Cancer 2019). Another cause of lung cancer’s high mortality stems from the fact that the patients tend to be older. In the United States, 68% of lung cancer patients are diagnosed after 65 years of age, and 14% are diagnosed after 80 years of age. Seniors are likely to have chronic health conditions already, and surgery to remove the tumor can be considered too risky (Venuta et al. 2016).

Because lung cancer can escape the immune system until it is severe, preventative measures such as vaccines should be a key priority. Cancer cells can evade immune attacks by exploiting checkpoint proteins on immune cells. For instance, tumor cells can increase the expression of checkpoint inhibitors like PD-L1, which binds to PD-1 on T cells, leading to their exhaustion (Salehi-Rad & Dubinett 2019). Lung cancer vaccines train the immune cells to recognize and attack the cancerous cells. These vaccines can also be used with other drugs to make them more effective. Not only can these vaccines be used before a patient gets lung cancer, but they can also be used during treatment (Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer | Penn Medicine | Philadelphia, PA, n.d.).

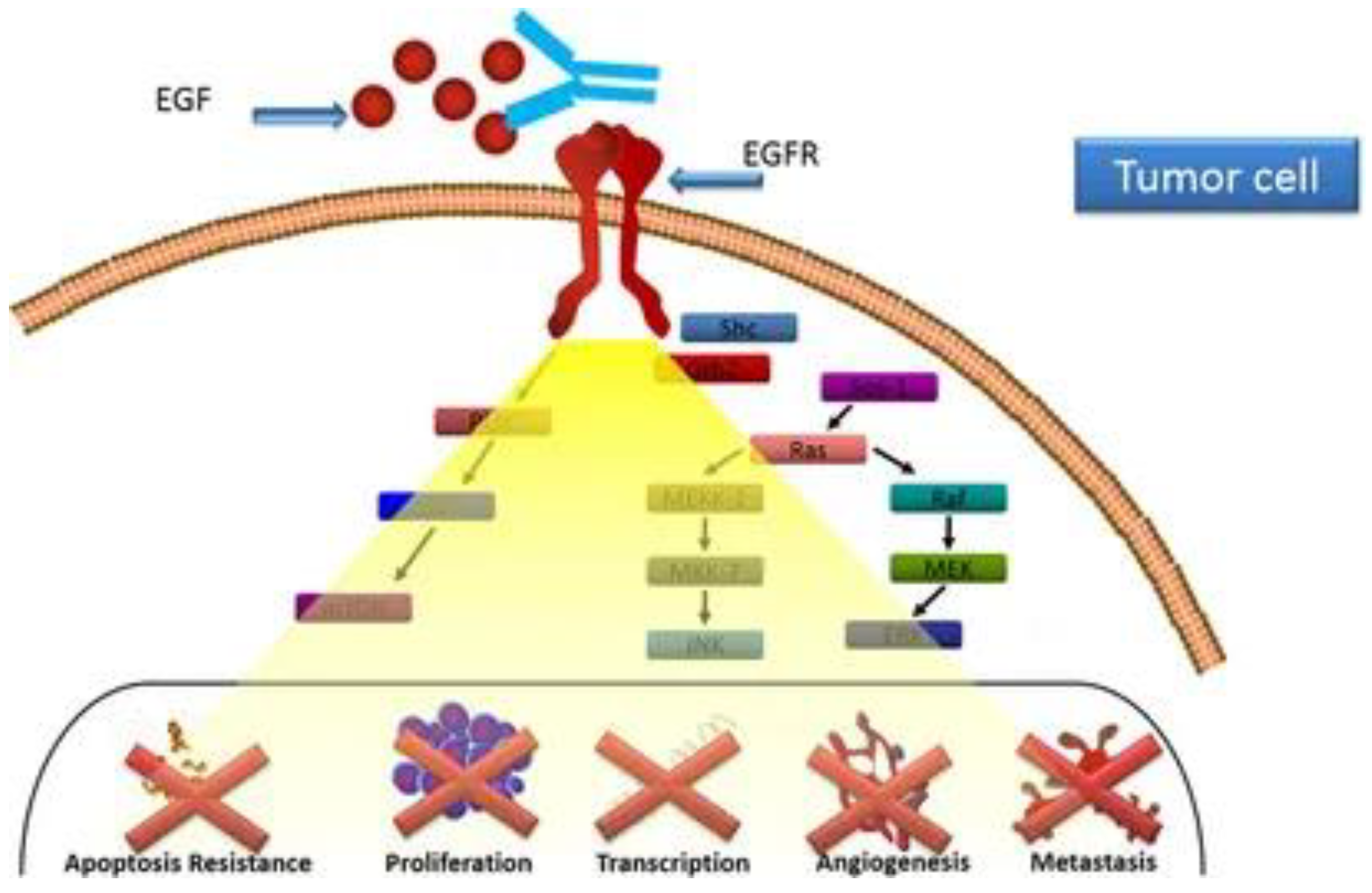

One vaccine that has promise is the CIMAvax-EGF (Mitsudomi 2014). This vaccine relies on the formation of antibodies against EGF. EGF is one of the seven known ligands of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR). EGFR is an oncogene and, when overly expressed, alters the regulation of the cell cycle, blocks apoptosis, aids in angiogenesis (formation of new blood vessels), and increases the invasiveness of tumor cells (Mitsudomi 2014). The vaccine works by separating EGF to cause hormonal castration, which is effective in hormone-dependent tumors (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). Since NSCLC is known to be a primary estrogen receptor (ER) positive tumor type, it’s a possible target (Smida et al. 2020).

Figure 1.

Anti-EGF antibodies produced in response to CIMAvax-EGF prevent EGFR activation and block the interaction of the EGF–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Saavedra & Crombet 2017).

Figure 1.

Anti-EGF antibodies produced in response to CIMAvax-EGF prevent EGFR activation and block the interaction of the EGF–epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Saavedra & Crombet 2017).

The vaccine targets the immune system by inducing anti-EGF antibodies. This helps reduce the circulating EGF, decreasing the probability of the remaining EGF binding to EGFR, which can help prevent the mutated EGFR from activating (García et al. 2008; Rodríguez et al. 2010).

This paper aims to provide a comprehensive review of the literature on CIMAvax-EGF, an EGF-based vaccine developed for patients with lung cancer and those at risk of developing lung cancer. Due to the high mortality associated with late-stage detection of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the trial is designed to evaluate the vaccine's capacity as a preventive therapy as well as its potential to impact overall survival, particularly in patients with advanced NSCLC. The paper will examine clinical trials and the current evidence for the vaccine's wider effect on lung cancer mortality and potential impact in combination with other therapies.

2. Methods

This paper aims to investigate a promising lung cancer vaccine for NSCLC. To do this, a predefined set of search phrases was surveyed to find papers in Google Scholar that matched. Initially, the keywords “lung cancer vaccine” were entered. Reviewing these articles showed a promising lung cancer vaccine called CIMAvax-EGF. Using this vaccine as a keyword, CIMAvax-EGF was searched through Google Scholar.

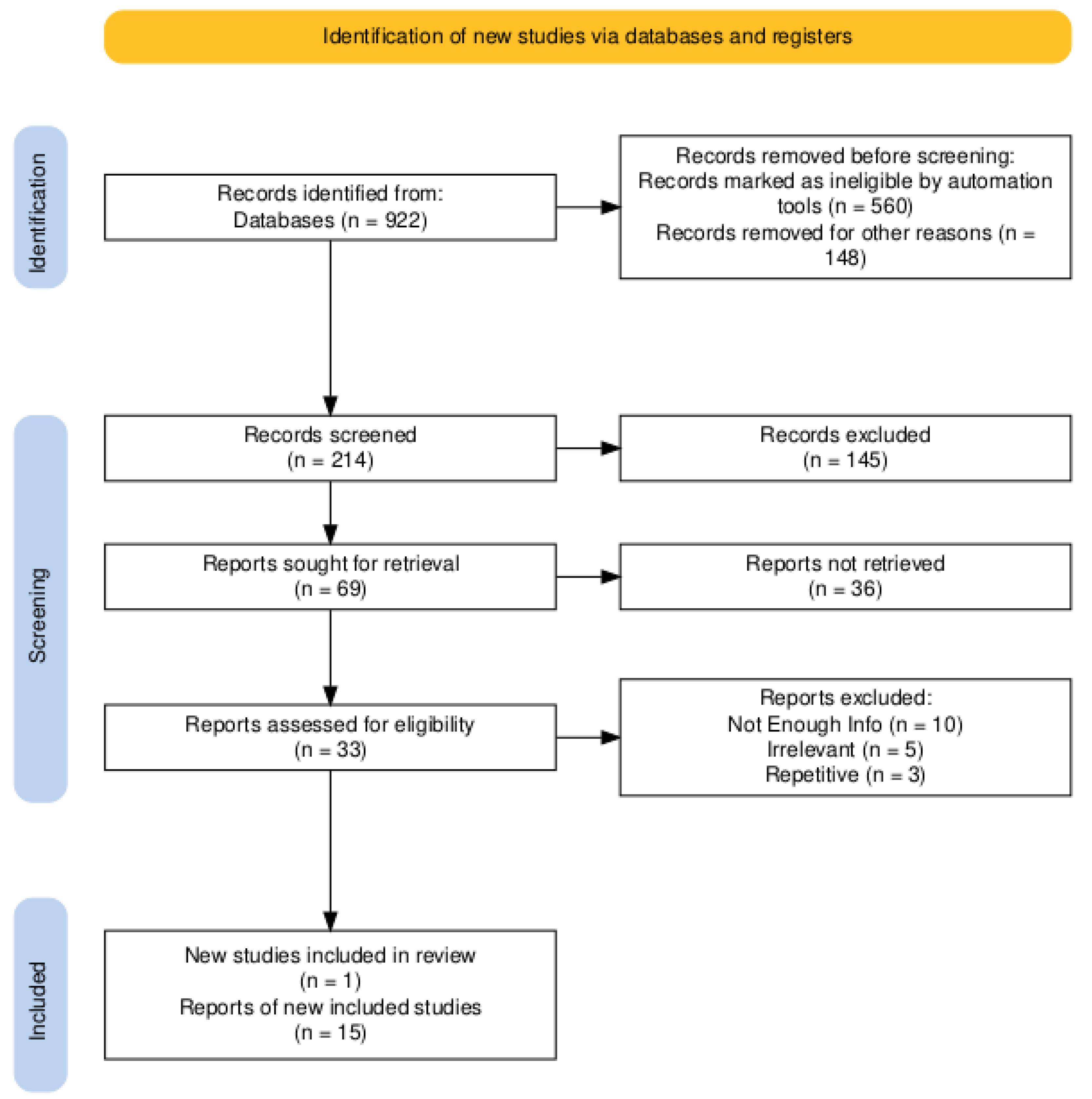

First, 922 studies were found. To find the most up-to-date results, only papers after 2020 were studied, which removed 560 papers. 148 papers were in a language other than English and were removed, leaving 214 papers. Briefly reading the titles and abstracts of the papers, 145 of these papers seemed like they needed to be more relevant and were removed leaving 69 papers. Of these papers, 36 were not easily accessible, so they were removed. The remaining 33 papers were analyzed in depth. Ten of these papers didn’t have enough information, five others were still irrelevant to the topic, and three had the same information as one of the previous articles. This left 15 papers that were used for their results. One extra article was found during this process and added. The flowchart below demonstrates this process.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram used to conduct the review.

Figure 2.

PRISMA Flow Diagram used to conduct the review.

3. Results

3.1. Impact on Survival

Most NSCLC patients have a higher expression level of EGFR (40-80%); consequently, vaccinations targeting EGFR, such as CIMAvax-EGF, are regarded as an essential immunotherapeutic approach. (Tasdemir et al. 2019; Su et al. 2023).

Results from CIMAvax-EGF in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients who had received prior frontline chemotherapy showed that the median overall survival for both vaccinated and unvaccinated patients was 12.43 and 9.43 months, respectively. Furthermore, the long-term survival rates for vaccinated and non-vaccinated individuals were 37% and 20% after two years and 23% and 0% after five years, respectively (Mussafi et al. 2022).

However, these results only occur when many doses are administered. Using a Harrington-Fleming test, a significant overall survival benefit was observed in populations of patients who received at least four vaccine doses (Xu et al. 2023).

Certain categories had significant differences between vaccination and control. Significant differences were observed between vaccinated patients and those in the control group, particularly in tumor stage and smoking history. There was also a trend toward a difference in histologic subtype. Overall, patients with stage IV cancer, active smokers, and those with squamous cell carcinomas benefited the most from CIMAvax-EGF compared to those who were not vaccinated (Saavedra et al. 2018).

Different groups had better results than others. Regarding performance status, the median overall survival for patients with an ECOG-0 was 29 months, whereas the median overall survival for those with an ECOG-1 at diagnosis was 11 months. When overall survival was broken down by age, patients under 65 had a median overall survival of 16.7 months, whereas patients over 65 had a median overall survival of 12.2 months (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.).

3.2. Testing Efficacy

In a Phase III trial, a significant proportion of patients (78.8%) met the good antibody response (GAR) condition associated with longer survival. The patients developing a GAR have shown a significant survival benefit (median survival time (MST) = 27.28 months) compared to controls (Saavedra & Crombet 2017).

After five and twelve months post-vaccination, respectively, the median binding inhibition capability was 20 and 40%. Moreover, EGFR phosphorylation was inhibited by post-immune sera. This means that the blood serum collected from an immunized individual could block the phosphorylation of EGFR, which prevents the activation and signal pathway from starting. After five and twelve months, the median phosphorylation inhibition was 65 and 85%, respectively (Saavedra & Crombet 2017).

Prolonged vaccination has raised levels of anti-EGF antibodies that can keep serum EGF levels undetectable (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). Patients with an [EGF] > 870 pg/ml have been shown to have a lower survival rate. CIMAvax-EGF has been shown to increase the survival of patients with this concentration or higher compared with controls with the same EGF serum level (14.66 months vs 8.63 months) (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). When comparing just the vaccine effects for patients with a high [EGF] vs a low [EGF], the patients with a lower EGF concentration had a higher survival rate (7.3 months vs 6.2 months) (Carrodeguas et al. 2022).

The clinical benefits of CIMAvax-EGF were linked to certain immunosenescence markers, including the proportion of CD8+CD28− cells, CD4 cells, and the CD4/CD8 ratio after initial chemotherapy. A study revealed that patients treated with CIMAvax-EGF who had a CD4+ T cell count over 40%, CD8+CD28− T cell counts below 24%, and a CD4/CD8 ratio greater than 2 following first-line platinum-based chemotherapy experienced a significantly longer median survival compared to similar patients who did not receive CIMAvax-EGF (Lorenzo-Luaces et al. 2020).

3.3. Combinations

Resistance to cancer vaccines in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a major obstacle despite their potential benefits. This resistance can occur in two main ways: intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic resistance involves factors within the tumor, such as mutations in pathways that help control the immune response, loss of tumor antigens, changes in how antigens are processed, loss of HLA expression, epigenetic modifications, and increased levels of immunosuppressive molecules. Extrinsic resistance is caused by factors outside the tumor, including immunosuppressive cells and cytokines that inhibit the activation of T cells. Lung cancer cells also produce various immunosuppressive substances that can interfere with the immune system’s ability to fight the cancer. Identifying and presenting lung tumor-associated antigens correctly could enable the immune system to target lung tumors effectively (Xiang et al. 2024).

CIMAvax-EGF is typically given after patients complete first-line chemotherapy (CTP), but starting the vaccine earlier might be more beneficial since it takes time to produce a neutralizing response. CIMAvax-EGF has been administered alongside platinum-based chemotherapy or even before CTP. Combining CTP with cancer vaccines resulted in added benefits, such as reducing immunosuppressive cells, enhancing antigen release, altering the tumor environment, and increasing T-cell activity in tumors (Saavedra & Crombet 2017).

A Phase I/II research study with nivolumab (a drug used in PD-1 blockade) and CIMAvax in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) revealed interim results that, except for one patient who received nivolumab alone, 44% of patients had an objective response rate (ORR) of 3+ and no adverse events (AE) of 3+. In contrast, the nivolumab monotherapy only had an ORR of 23% (Mussafi et al. 2022).

3.4. Side Effects

In a study, 78.3% of the participants experienced adverse events to the vaccine, and 59.4% of the treated patients had vaccine-related events, totaling 1,200 incidents. The most common side effects included injection-site pain (46.6%), fever (36.5%), vomiting (23.3%), and headache (22.5%). Severe (grade 3) adverse events were reported in 3.6% of patients, with some experiencing headache, difficulty breathing, injection-site reactions, elevated eosinophil levels, fever, chills, tremors, and joint pain. However, no patient experienced the most severe (grade 4) adverse events (Rodriguez et al. 2016).

Table 1.

Summary of Results.

Table 1.

Summary of Results.

| Study/Parameter |

Vaccinated Group |

Control/Unvaccinated Group |

Observations |

| Median Overall Survival (Months) |

12.43 |

9.43 |

CIMAvax-EGF improved median survival by three months in advanced NSCLC patients (Mussafi et al. 2022). |

| Long-term Survival (2 years) |

0.37 |

0.2 |

The vaccinated group had nearly double the 2-year survival rate (Mussafi et al. 2022). |

| Long-term Survival (5 years) |

0.23 |

0 |

Significant 5-year survival benefit observed in vaccinated patients (Mussafi et al. 2022). |

| Survival in Patients Receiving ≥ 4 Doses |

Significant improvement observed |

N/A |

Benefits were seen in those who received at least four doses (Harrington-Fleming test) (Xu et al. 2023). |

| Stage IV, Smokers, Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

Significant benefits in these subgroups |

Lesser benefit |

Vaccinated patients in these categories showed the most improvement compared to controls (Saavedra et al. 2018). |

| ECOG-0 Patients (Median Survival) |

29 months |

N/A |

Patients with ECOG-0 performance status had significantly longer survival (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.). |

| ECOG-1 Patients (Median Survival) |

11 months |

N/A |

Lower median survival for ECOG-1 patients, but still better with vaccination (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.). |

| Survival for Age <65 (Median) |

16.7 months |

N/A |

Younger patients (<65 years) showed better survival outcomes (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.). |

| Survival for Age >65 (Median) |

12.2 months |

N/A |

Older patients (>65 years) had lower but improved survival with vaccination (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.). |

| GAR (Good Antibody Response) Survival |

27.28 months (GAR group) |

N/A |

Significant survival advantage in patients with GAR (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). |

| EGFR Phosphorylation Inhibition |

65-85% inhibition (5-12 months post-vax) |

N/A |

Blood serum from vaccinated patients could inhibit EGFR phosphorylation, helping to block tumor growth (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). |

| Survival for High EGF Concentration |

14.66 months |

8.63 months |

CIMAvax-EGF increased survival in patients with high EGF levels compared to controls (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). |

| Nivolumab + CIMAvax (Objective Response) |

44% |

23% (nivolumab alone) |

A combination of CIMAvax and nivolumab had higher response rates than nivolumab alone (Mussafi et al. 2022). |

| Side Effects (Overall Adverse Events) |

78.3% (adverse events) |

N/A |

59.4% of patients experienced vaccine-related events; injection-site pain and fever were the most common (Rodriguez et al. 2016). |

| Severe Side Effects (Grade 3) |

0.036 |

N/A |

Severe adverse events like headache and difficulty breathing were rare; no Grade 4 side effects were observed (Rodriguez et al. 2016). |

4. Discussion

Given the high expression levels of EGFR in a substantial portion of NSCLC patients, the potential of CIMAvax-EGF as a significant immunotherapeutic option for advanced NSCLC is very high (Tasdemir et al. 2019; Su et al. 2023).

The survival benefits observed in patients treated with CIMAvax-EGF are noteworthy. Patients who received the vaccine showed a median overall survival of 12.43 months compared to 9.43 months in unvaccinated patients. Furthermore, long-term survival rates were considerably higher among vaccinated patients, with 37% surviving after two years and 23% after five years, compared to only 20% and 0% among unvaccinated patients (Mussafi et al. 2022). These findings suggest that CIMAvax-EGF may provide substantial long-term survival benefits, particularly when multiple doses are administered. Specifically, the Harrington-Fleming test indicated a significant overall survival advantage in patients who received at least four vaccine doses (Xu et al. 2023).

The differential impact of CIMAvax-EGF across patient subgroups is also noteworthy. Patients with stage IV cancer, active smokers, and those with squamous cell carcinoma showed the most pronounced benefits from vaccination. This suggests that CIMAvax-EGF may be particularly effective in these high-risk populations (Saavedra et al. 2018). The variation in outcomes based on performance status and age further underscores the importance of patient selection in maximizing the therapeutic benefits of CIMAvax-EGF. For instance, patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 had a median overall survival of 29 months, significantly higher than the 11-month median survival observed in patients with an ECOG-1 status. Similarly, younger patients (under 65 years) experienced better outcomes than older patients, indicating that age may be a factor in response to the vaccine (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.).

Many studies have proven the efficacy of CIMAvax-EGF. A Phase III trial demonstrated that a significant proportion of patients (78.8%) achieved a good antibody response (GAR), a condition strongly associated with longer survival. Patients who developed a GAR had a median survival time of 27.28 months, significantly longer than that of the control group (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). Another study found that prolonged vaccination decreased EGFR phosphorylation by 85% in twelve months (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). Furthermore, the vaccine increased levels of anti-EGF antibodies, which could maintain serum EGF levels at undetectable levels, further contributing to survival benefits (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). This effect was particularly evident in patients with serum EGF concentrations above 870 pg/ml, where CIMAvax-EGF significantly increased survival compared to controls (Saavedra & Crombet 2017; Carrodeguas et al. 2022).

Another critical finding is the relationship between CIMAvax-EGF's clinical benefits and specific immunosenescence (immune system deterioration) markers, such as the proportions of CD8+CD28− cells, CD4 cells, and the CD4/CD8 ratio. Patients with favorable immunosenescence profiles after initial chemotherapy, such as higher CD4+ T cell counts, lower CD8+CD28− T cell counts, and a higher CD4/CD8 ratio, experienced significantly longer median survival compared to similar patients who did not receive CIMAvax-EGF (Lorenzo-Luaces et al. 2020). This can be used as another way to test the vaccine's efficacy.

However, overcoming resistance to cancer vaccines, particularly in NSCLC, remains a critical issue. Both intrinsic and extrinsic resistance mechanisms can undermine the efficacy of CIMAvax-EGF. Intrinsic resistance involves tumor-related factors such as mutations and loss of tumor antigens, while extrinsic resistance is driven by the immunosuppressive environment created by the tumor and surrounding tissues (Xiang et al. 2024). Addressing these resistance mechanisms may involve strategic combinations of CIMAvax-EGF with other therapies, such as chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors, to enhance vaccine efficacy (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). CTP has been found to reduce immunosuppressive cells, which can then be combined with the vaccine to produce the best results (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). Another combination from a Phase I/II study combining nivolumab with CIMAvax-EGF is promising, showing a higher objective response rate than nivolumab monotherapy, with a favorable safety profile (Mussafi et al. 2022).

Finally, the safety profile of CIMAvax-EGF is generally acceptable, with most adverse events being mild to moderate. The most common side effects include injection-site pain, fever, vomiting, and headache, with severe (grade 3) adverse events being relatively rare. Importantly, no patients experienced grade 4 adverse events, indicating that CIMAvax-EGF is a well-tolerated treatment option for most patients (Rodriguez et al. 2016).

5. Conclusions

Lung cancer is one of the deadliest cancers, with around 234,580 new cases diagnosed annually in the U.S. resulting in approximately 125,070 deaths each year (Where Does Metastatic Lung Cancer Spread To?, n.d.). The survival rate varies based on the type and spread of the cancer, with localized non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) having a 5-year survival rate of 64%, which drops significantly if the cancer spreads (Lung Cancer Survival Rates | 5-Year Survival Rates for Lung Cancer, n.d.)l.

Two main factors contribute to lung cancer's high mortality: its difficulty in early detection and the age of patients, with most being over 65, often making surgery too risky (Venuta et al. 2016; Lung Cancer 2019). As a result, preventative measures like vaccines are crucial. CIMAvax-EGF is a promising vaccine targeting the Epidermal Growth Factor (EGF), which plays a role in cancer cell growth. By inducing the production of anti-EGF antibodies, CIMAvax-EGF aims to prevent EGF from binding to its receptor, potentially stopping cancer progression (Mitsudomi 2014). This vaccine could be used both preventatively and during treatment.

A systematic review was conducted using Google Scholar to find information about CIMAvax-EGF. The results were filtered from 2020 to find the most up-to-date information later. The process was then repeated to find the most relevant information.

CIMAvax-EGF shows significant promise for treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) due to its ability to target the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) (Tasdemir et al. 2019; Su et al. 2023). Studies have demonstrated survival benefits, with vaccinated patients having a median overall survival of 12.43 months compared to 9.43 months in unvaccinated individuals. Long-term survival rates were also higher, particularly in patients receiving multiple doses (Mussafi et al. 2022).

CIMAvax-EGF is particularly effective in high-risk groups, such as those with stage IV cancer, active smokers, and squamous cell carcinoma patients (Saavedra et al. 2018). The vaccine's effectiveness is further enhanced in patients with good performance status and younger age (Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario - PMC, n.d.). A Phase III trial revealed that 78.8% of patients achieved a good antibody response (GAR), leading to longer survival (Saavedra & Crombet 2017). Prolonged vaccination also decreased EGFR phosphorylation and maintained undetectable serum EGF levels, contributing to survival benefits (Saavedra & Crombet 2017).

The vaccine's efficacy is linked to favorable immunosenescence markers, with patients showing better immune profiles experiencing longer survival (Lorenzo-Luaces et al. 2020; Carrodeguas et al. 2022). However, resistance to the vaccine remains a challenge, potentially addressed by combining CIMAvax-EGF with other therapies like chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors. For example, in conjunction with CIMAvax, nivolumab has shown a higher ORR than nivolumab alone (Mussafi et al. 2022).

CIMAvax-EGF is generally well-tolerated, with most side effects being mild to moderate, making it a viable treatment option for many patients (Rodriguez et al. 2016).

Lung cancer has a very high mortality. Clearly, the available treatments are not enough to treat it and prevent people from dying. Because of this, vaccines must be pursued. As shown, CIMAvax-EGF seems to be a very effective vaccine as it targets the underlying issue that causes cancer with incredible results. With minimal side effects, this vaccine should be administered adjuvantly and neoadjuvantly. This vaccine also boosts other treatments available. For example, combining it with immune checkpoint inhibitors makes the inhibitor more potent. This vaccine can be a big step forward in battling lung cancer and preventing lung cancer from taking so many lives.

References

- Carrodeguas, R. A. O. Monteagudo, G. L. Guerra, P. P. Sanchez, L. Cárdenas, L. Álvarez, I. Salomón, E. E. Díaz, M. Menéndez, Y. Lobaina, L. Columbié, J. C. Camacho, K. Corella, M. Fardales, N. Parra, J. Viada, C. Saavedra, D. Santos, O. & Ramos, T. C. 2022 766P Levels of serum EGF concentration as biomarker of response of CIMAvax-EFG vaccine: Survival evaluation of advanced NSCLC patients treated in primary health care scenario. Annals of Oncology 33, S892. [CrossRef]

- García, B. Neninger, E. de la Torre, A. Leonard, I. Martínez, R. Viada, C. González, G. Mazorra, Z. Lage, A. & Crombet, T. 2008 Effective Inhibition of the Epidermal Growth Factor/Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Binding by Anti–Epidermal Growth Factor Antibodies Is Related to Better Survival in Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients Treated with the Epidermal Growth Factor Cancer Vaccine. Clinical Cancer Research, 14(3), 840–846. [CrossRef]

- Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer | Penn Medicine | Philadelphia, PA. (n.d.). Penn Medicine - Abramson Cancer Center. Retrieved August 2 2024, from https://www.pennmedicine. 2 August.

- Lorenzo-Luaces, P. Sanchez, L. Saavedra, D. Crombet, T. Van der Elst, W. Alonso, A. Molenberghs, G. & Lage, A. 2020 Identifying predictive biomarkers of CIMAvaxEGF success in non–small cell lung cancer patients, 20(1), 772. BMC Cancer. [CrossRef]

- Lung cancer: Early signs and symptoms. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/327371. 21 December 2019.

- Lung Cancer Statistics | How Common is Lung Cancer? (n.d.). Retrieved August 3 2024, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/about/key-statistics.html. 2 August.

- Lung Cancer Survival Rates | 5-Year Survival Rates for Lung Cancer. (n.d.). Retrieved August 2 2024, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/lung-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html. 3 August.

- Mitsudomi, T. 2014 Molecular epidemiology of lung cancer and geographic variations with special reference to EGFR mutations. Translational Lung Cancer Research, 3(4). [CrossRef]

- Mussafi, O. Mei, J. Mao, W. & Wan, Y. 2022 Immune checkpoint inhibitors for PD-1/PD-L1 axis in combination with other immunotherapies and targeted therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, P. C. Popa, X. Martínez, O. Mendoza, S. Santiesteban, E. Crespo, T. Amador, R. M. Fleytas, R. Acosta, S. C. Otero, Y. Romero, G. N. de la Torre, A. Cala, M. Arzuaga, L. Vello, L. Reyes, D. Futiel, N. Sabates, T. Catala, M. … Neninger, E. 2016 A Phase III Clinical Trial of the Epidermal Growth Factor Vaccine CIMAvax-EGF as Switch Maintenance Therapy in Advanced Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Clinical Cancer Research 22(15), 3782–3790, 3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, P. C. Rodríguez, G. González, G. & Lage, A. 2010 Clinical development and perspectives of CIMAvax EGF, cuban vaccine for non-small-cell lung cancer therapy. MEDICC Review, 12(1), 17–23.

- Saavedra, D. & Crombet, T. 2017 CIMAvax-EGF: A New Therapeutic Vaccine for Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Frontiers in Immunology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, D. Neninger, E. Rodriguez, C. Viada, C. Mazorra, Z. Lage, A. & Crombet, T. 2018 CIMAvax-EGF: Toward long-term survival of advanced NSCLC. Seminars in Oncology, 45(1), 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Salehi-Rad, R. & Dubinett, S. M. 2019 Understanding the mechanisms of immune-evasion by lung cancer in the context of chronic inflammation in emphysema. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 11(2), 382–385. [CrossRef]

- Smida, T. Bruno, T. C. & Stabile, L. P. 2020 Influence of Estrogen on the NSCLC Microenvironment: A Comprehensive Picture and Clinical Implications. Frontiers in Oncology, 10. [CrossRef]

- Su, S. Chen, F. Xu, M. Liu, B. & Wang, L. 2023 Recent advances in neoantigen vaccines for treating non-small cell lung cancer. Thoracic Cancer, 14(34), 3361–3368, 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Survival of NSCLC Patients Treated with Cimavax-EGF as Switch Maintenance in the Real-World Scenario—PMC. (n.d.). Retrieved August 24 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10088885/.

- Tasdemir, S. Taheri, S. Akalin, H. Kontas, O. Onal, O. & Ozkul, Y. 2019 Increased EGFR mRNA Expression Levels in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. The Eurasian Journal of Medicine, 51(2), 177–185. [CrossRef]

- Venuta, F. Diso, D. Onorati, I. Anile, M. Mantovani, S. & Rendina, E. A. 2016 Lung cancer in elderly patients. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 8(Suppl 11). [CrossRef]

- Where Does Metastatic Lung Cancer Spread To? (n.d.). Moffitt. Retrieved August 2 2024, from https://www.moffitt.org/cancers/lung-cancer/metastatic-lung-cancer/where-does-metastatic-lung-cancer- spread-to/.

- Xiang, Y. Liu, X. Wang, Y. Zheng, D. Meng, Q. Jiang, L. Yang, S. Zhang, S. Zhang, X. Liu, Y. & Wang, B. 2024 Mechanisms of resistance to targeted therapy and immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: Promising strategies to overcoming challenges. Frontiers in Immunology, 15. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Liu, C. Wu, X. & Ma, J. 2023 Current immune therapeutic strategies in advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Chinese Medical Journal 136(15), 1765. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).