Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Ethics Committee

2.2. Patient Population

2.3. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Treatment duration

3.3. Treatment Response

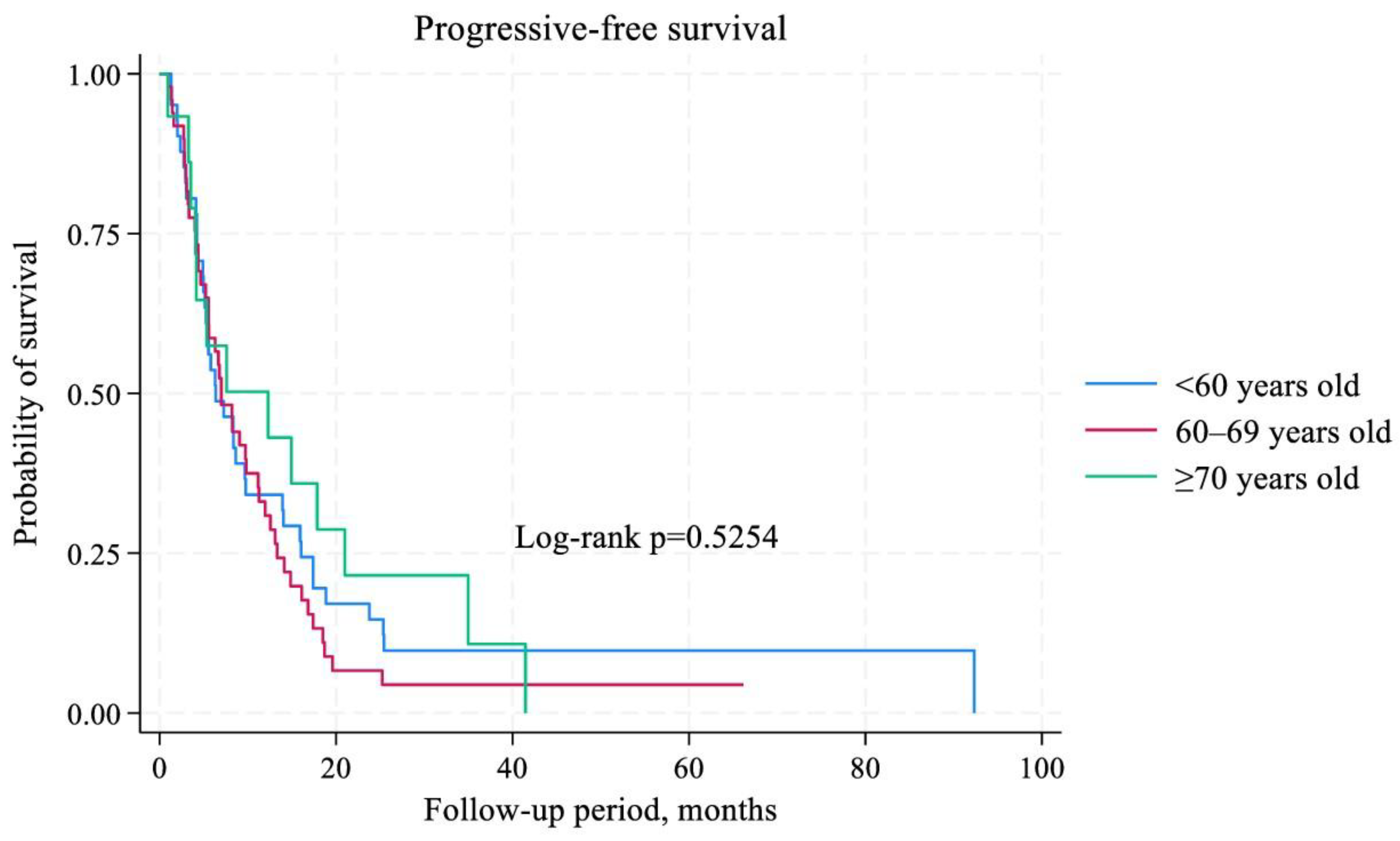

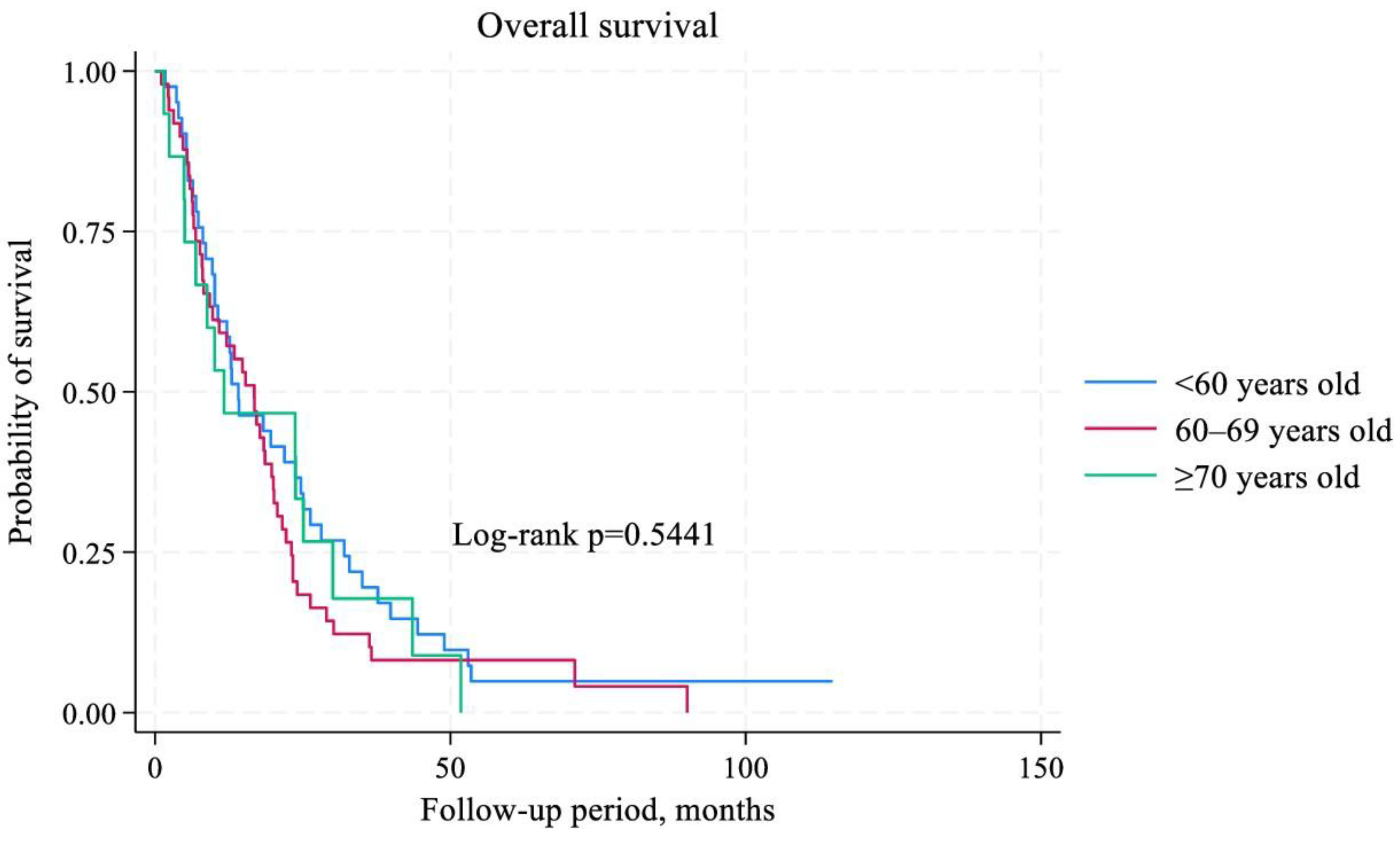

3.4. Survival Analysis

3.5. Independent Predictors of Survival

3.6. Immune-Related Adverse Events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SIOG | International Society of Geriatric Oncology |

| ICI | Immune checkpoint inhibitor |

| mNSCLC | Metastatic non-small cell lung cancer |

References

- Pilleron S, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E, Vignat J, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Bray F, Sarfati D. Estimated global cancer incidence in the oldest adults in 2018 and projections to 2050. Int J Cancer. 2021 Feb 1;148(3):601-608. [CrossRef]

- Ferrat E, Paillaud E, Caillet P, Laurent M, Tournigand C, Lagrange JL, Droz JP, Balducci L, Audureau E, Canouï-Poitrine F, Bastuji-Garin S. Performance of Four Frailty Classifications in Older Patients With Cancer: Prospective Elderly Cancer Patients Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Mar;35(7):766-777. [CrossRef]

- Kudlova N, De Sanctis JB, Hajduch M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Apr 10;23(8):4168. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Liang Q, Ren Y, Guo C, Ge X, Wang L, Cheng Q, Luo P, Zhang Y, Han X. Immunosenescence: molecular mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 May 13;8(1):200. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, De Benedictis G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000 Jun;908:244-54. [CrossRef]

- Santoro A, Bientinesi E, Monti D. Immunosenescence and inflammaging in the aging process: age-related diseases or longevity? Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Nov;71:101422. [CrossRef]

- Gulla S, Reddy MC, Reddy VC, Chitta S, Bhanoori M, Lomada D. Role of thymus in health and disease. Int Rev Immunol. 2023;42(5):347-363. [CrossRef]

- Goronzy JJ, Weng NP. The immunology and cell biology of T cell aging. Semin Immunol. 2023 Nov;70:101843. [CrossRef]

- Dale W, Klepin HD, Williams GR, Alibhai SMH, Bergerot C, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Hopkins JO, Jhawer MP, Katheria V, Loh KP, Lowenstein LM, McKoy JM, Noronha V, Phillips T, Rosko AE, Ruegg T, Schiaffino MK, Simmons JF Jr, Subbiah I, Tew WP, Webb TL, Whitehead M, Somerfield MR, Mohile SG. Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic Cancer Therapy: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023 Sep 10;41(26):4293-4312. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda S, Kitagawa Y, Okui J, Okamura A, Kawakubo H, Takemura R, Muto M, Kakeji Y, Takeuchi H, Watanabe M, Doki Y. Old age and intense chemotherapy exacerbate negative prognostic impact of postoperative complication on survival in patients with esophageal cancer who received neoadjuvant therapy: a nationwide study from 85 Japanese esophageal centers. Esophagus. 2023 Jul;20(3):445-454. [CrossRef]

- Kim SY, Halmos B. Choosing the best first-line therapy: NSCLC with no actionable oncogenic driver. Lung Cancer Manag. 2020 Jul 24;9(3):LMT36. [CrossRef]

- Choucair K, Naqash AR, Nebhan CA, Nipp R, Johnson DB, Saeed A. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: The Unexplored Landscape of Geriatric Oncology. Oncologist. 2022 Sep 2;27(9):778-789. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi O, Imai H, Minemura H, Suzuki K, Wasamoto S, Umeda Y, Osaki T, Kasahara N, Uchino J, Sugiyama T, Ishihara S, Ishii H, Naruse I, Mori K, Kotake M, Kanazawa K, Minato K, Kagamu H, Kaira K. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitor monotherapy in pretreated elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2020 Apr;85(4):761-771. [CrossRef]

- Al-Danakh A, Safi M, Jian Y, Yang L, Zhu X, Chen Q, Yang K, Wang S, Zhang J, Yang D. Aging-related biomarker discovery in the era of immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer patients. Front Immunol. 2024 Mar 15;15:1348189. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam G, Das S, Paul S, Rakshit S, Sarkar K. Clinical relevance and therapeutic aspects of professional antigen-presenting cells in lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2022 Sep 29;39(12):237. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Chen L, Fu D, Liu W, Puri A, Kellis M, Yang J. Antigen presenting cells in cancer immunity and mediation of immune checkpoint blockade. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2024 Aug;41(4):333-349. [CrossRef]

- Granier C, Gey A, Roncelin S, Weiss L, Paillaud E, Tartour E. Immunotherapy in older patients with cancer. Biomed J. 2021 Jun;44(3):260-271. [CrossRef]

- Tang S, Qin C, Hu H, Liu T, He Y, Guo H, Yan H, Zhang J, Tang S, Zhou H. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Cells. 2022 Jan 19;11(3):320. [CrossRef]

- Fasano M, Corte CMD, Liello RD, Viscardi G, Sparano F, Iacovino ML, Paragliola F, Piccolo A, Napolitano S, Martini G, Morgillo F, Cappabianca S, Ciardiello F. Immunotherapy for head and neck cancer: Present and future. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2022 Jun;174:103679. [CrossRef]

- Yang YN, Wang LS, Dang YQ, Ji G. Evaluating the efficacy of immunotherapy in gastric cancer: Insights from immune checkpoint inhibitors. World J Gastroenterol. 2024 Aug 28;30(32):3726-3729. [CrossRef]

- Li H, Lin S, Wang Y, Shi Y, Fang X, Wang J, Cui H, Bian Y, Qi X. Immunosenescence: A new direction in anti-aging research. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024 Nov 15;141:112900. [CrossRef]

- Smith A, Boby JM, Benny SJ, Ghazali N, Vermeulen E, George M. Immunotherapy in Older Patients with Cancer: A Narrative Review. Int J Gen Med. 2024 Jan 30;17:305-313. [CrossRef]

- Sun YM, Wang Y, Sun XX, Chen J, Gong ZP, Meng HY. Clinical Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Older Non-small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2020 Sep 23;10:558454. [CrossRef]

- Arias Ron D, Areses Manrique MC, Mosquera Martínez J, García González J, Afonso Afonso FJ, Lázaro Quintela M, Fernández Núñez N, Azpitarte Raposeiras C, Amenedo Gancedo M, Santomé Couto L, García Campelo MR, Muñoz Iglesias J, Ruiz Bañobre J, Vilchez Simo R, Casal Rubio J, Campos Balea B, Carou Frieiro I, Alonso-Jaudenes Curbera G, Anido Herranz U, García Mata J, Fírvida Pérez JL. Efficacy and safety of Nivolumab in older patients with pretreated lung cancer: A subgroup analysis of the Galician lung cancer group. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021 Apr;12(3):410-415. [CrossRef]

- Luciani A, Marra A, Toschi L, Cortinovis D, Fava S, Filipazzi V, Tuzi A, Cerea G, Rossi S, Perfetti V, Rossi A, Giannetta L, Sala L, Finocchiaro G, Pizzutilo EG, Carelli S, Agustoni F, Cergnul M, Zonato S, Siena S, Bidoli P, Ferrari D. Efficacy and Safety of Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Patients Aged ≥ 75 Years With Non-small-cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): An Italian, Multicenter, Retrospective Study. Clin Lung Cancer. 2020 Nov;21(6):e567-e571. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein MRL, Nipp RD, Muzikansky A, Goodwin K, Anderson D, Newcomb RA, Gainor JF. Impact of Age on Outcomes with Immunotherapy in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2019 Mar;14(3):547-552. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Wang Q, Xie J, Chen M, Liu H, Zhan P, Lv T, Song Y. The Predictive Value of Clinical and Molecular Characteristics or Immunotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Oncol. 2021 Sep 7;11:732214. [CrossRef]

- Mebarki S, Pamoukdjian F, Pierro M, Poisson J, Baldini C, Widad Lahlou, Taieb J, Fabre E, Canoui-Poitrine F, Oudard S, Paillaud E. Safety and efficacy of immunotherapy according to the age threshold of 80 years. Bull Cancer. 2023 May;110(5):570-580. [CrossRef]

- Tagliamento M, Frelaut M, Baldini C, Naigeon M, Nencioni A, Chaput N, Besse B. The use of immunotherapy in older patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2022 May;106:102394. [CrossRef]

- Huang X, Wu S, Chen S, Qiu M, Zhao Y, Wei J, He J, Zhao W, Tan L, Su C, Zhou S. Prognostic impact of age in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients undergoing first-line checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy and chemotherapy treatment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024 May 10;132:111901. [CrossRef]

- Ramos MJ, Mendes AS, Romão R, Febra J, Araújo A. Immunotherapy in Elderly Patients-Single-Center Experience. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Dec 27;16(1):145. [CrossRef]

- Bogani G, Cinquini M, Signorelli D, Pizzutilo EG, Romanò R, Bersanelli M, Raggi D, Alfieri S, Buti S, Bertolini F, Bonomo P, Marandino L, Rizzo M, Monteforte M, Aiello M, Tralongo AC, Torri V, Di Donato V, Giannatempo P. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the optimal treatment duration of checkpoint inhibitoRS in solid tumors: The OTHERS study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2023 Jul;187:104016. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Kim DW, Kim M, Lee Y, Ahn HK, Cho JH, Kim IH, Lee YG, Shin SH, Park SE, Jung J, Kang EJ, Ahn MJ. Long-term outcomes in patients with advanced and/or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer who completed 2 years of immune checkpoint inhibitors or achieved a durable response after discontinuation without disease progression: Multicenter, real-world data (KCSG LU20-11). Cancer. 2022 Feb 15;128(4):778-787. [CrossRef]

| Variables | <60 years, n=41 | 60–69 years, n=49 | ≥70 years, n=15 | χ2 (р) |

| Sex, n (%) Male Female |

34 (82,9) 7 (17,1) |

43 (87,8) 6 (12,2) |

12 (80,0) 3 (20,0) |

0,7101 (0,701) |

| Histology, n (%) Adenocarcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma |

26 (63,4) 15 (36,6) |

24 (49,0) 25 (51,0) |

8 (53,3) 7 (46,7) |

1,9068 (0,385) |

| Metastasis in the brain, n (%) Absent Present |

40 (97,6) 1 (2,4) |

48 (98,0) 1 (2,0) |

15 (100,0) 0 (0,0) |

0,3587 (0,836) |

| Metastasis in the lung, n (%) Absent Present |

21 (51,2) 20 (48,7) |

28 (57,1) 21 (42,9) |

7 (46,7) 8 (53,3) |

0,6272 (0,731) |

| Metastasis in the pleura, n (%) Absent Present |

39 (95,1) 2 (4,9) |

47 (95,9) 2 (4,1) |

7 (46,7) 8 (53,3) |

30,3724 (0,0001) |

| Metastasis in the liver, n (%) Absent Present |

33 (80,5) 8 (19,5) |

34 (69,4) 15 (30,6) |

9 (60,0) 6 (40,0) |

2,7177 (0,257) |

| Metastasis in the bones, n (%) Absent Present |

31 (75,6) 10 (24,4) |

29 (51,2) 20 (40,8) |

12 (80,0) 3 (20,0) |

3,8553 (0,145) |

| Treatment line, n (%) First Second |

36 (87,8) 5 (12,2) |

43 (87,8) 6 (12,2) |

14 (93,3) 1 (6,7) |

0,3921 (0,822) |

| Immunotherapy regimen, n (%) ICIs monotherapy Chemoimmunotherapy |

17 (41,5) 24 (58,5) |

16 (32,7) 33 (67,3) |

5 (33,3) 10 (66,7) |

0,8122 (0,666) |

| Type of ICIs, n (%) Atezolizumab Pembrolizumab |

18 (43,9) 23 (56,1) |

16 (32,7) 33 (67,3) |

5 (33,3) 10 (66,7) |

0,3187 (0,517) |

| irAE, n (%) Absent Present |

34 (82,9) 7 (17,1) |

38 (77,6) 11 (22,4) |

6 (40,0) 9 (60,0) |

8,0142 (0,018) |

| Age groups | The median duration of ICI treatment (range), months | р |

| <60 years, n=41 | 7,8 (1,3–20,0) | 0,9718 |

| 60–69 years, n=49 | 7,6 (1,0–18,7) | |

| ≥70 years, n=15 | 8,8 (1,0–24,0) |

| Treatment response | <60 years, n (%) | 60–69, n (%) | ≥70 years, n (%) | χ2 (р) |

| ORR: Yes (n=54) No (n=51) |

19 (35,2) 22 (43,1) |

27 (50,0) 22 (43,1) |

8 (14,8) 7 (13,8) |

0,7112 (0,701) |

| DCR: Yes (n=91) No (n=14) |

35 (38,5) 6 (42,9) |

43 (47,3) 6 (42,9) |

13 (14,2) 2 (14,2) |

0,1103 (0,946) |

|

Variables |

PFS | OS | ||||

| HR | 95% CI | р | HR | 95% CI | р | |

| Age (<60 versus 60-69 versus ≥70 years old) | 1,27 | 0,89–1,81 | 0,184 | 1,21 | 0,86–1,70 | 0,254 |

| Sex (male versus female) | 1,37 | 0,58–3,23 | 0,460 | 1,12 | 0,45–2,76 | 0,804 |

| Histology (adenocarcinoma versus squamous cell carcinoma) | 0,92 | 0,56–1,51 | 0,759 | 1,17 | 0,70–1,94 | 0,539 |

| Metastasis in the brain (absent versus present) | 0,59 | 0,07–4,50 | 0,616 | 0,48 | 0,06–3,71 | 0,485 |

| Metastasis in the lung (absent versus present) | 1,34 | 0,83–2,16 | 0,225 | 1,12 | 0,71–1,77 | 0,618 |

| Metastasis in the pleura (absent versus present) | 0,85 | 0,27–1,51 | 0,693 | 1,45 | 0,64–3,25 | 0,364 |

| Metastasis in the liver (absent versus present) | 1,33 | 0,78–2,25 | 0,290 | 1,10 | 0,66–1,82 | 0,710 |

| Metastasis in the bones (absent versus present) | 1,03 | 0,65–1,64 | 0,879 | 0,86 | 0,53–1,40 | 0,555 |

| Treatment line (first versus second) | 0,50 | 0,22–1,16 | 0,111 | 0,65 | 0,25–1,72 | 0,396 |

| Immunotherapy regimen (ICI monotherapy versus chemoimmunotherapy) | 0,77 | 0,45–1,33 | 0,362 | 1,78 | 1,00–3,17 | 0,051 |

| Type of ICI (Atezolizumab versus Pembrolizumab) | 1,37 | 0,81–2,30 | 0,230 | 1,64 | 0,98–2,75 | 0,056 |

| irAE (absent versus present) | 1,00 | 0,56–1,80 | 0,985 | 0,82 | 0,45–1,51 | 0,534 |

| ORR (yes versus no) | 2,64 | 1,27–5,48 | 0,009 | 1,54 | 0,74–3,23 | 0,245 |

| DCR (yes versus no) | 2,43 | 0,91–6,51 | 0,076 | 1,61 | 0,61–4,22 | 0,330 |

| Duration of ICI treatment (≥8,0 versus <8,0 months) | 41,09 | 12,99–129,99 | 0,0001 | 6,61 | 3,07–14,22 | 0,0001 |

| irAE | <60 years old | 60–69 years old | ≥70 years old |

| Pruritus | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Hypothyroidism | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Hyperthyroidism | 2 (4,9%) | 2 (4,1%) | 2 (13,3%) |

| Hepatitis | 1 (2,4) | 1 (2,0%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Nephritis | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Colitis | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Arthralgia | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Myalgia | 0 (0,0%) | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Bullous pemphigus | 1 (2,4%) | 0 (0,0%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Onycholysis | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Optic neuritis | 1 (2,4%) | 0 (0,%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Rash | 1 (2,4%) | 0 (0,0%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Aseptic bone necrosis | 1 (2,4%) | 0 (0,0%) | 0 (0,0%) |

| Infusion reaction | 0 (0,0%) | 1 (2,0%) | 1 (6,7%) |

| Total number of irAE of any grade of toxicity | 7 (17,1%) | 11 (22,4%) | 9 (60,0%) |

| Number of irAE ≥ grade 3 of toxicity | 5 (12,2%) | 3 (6,1%) | 1 (6,7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).