Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials

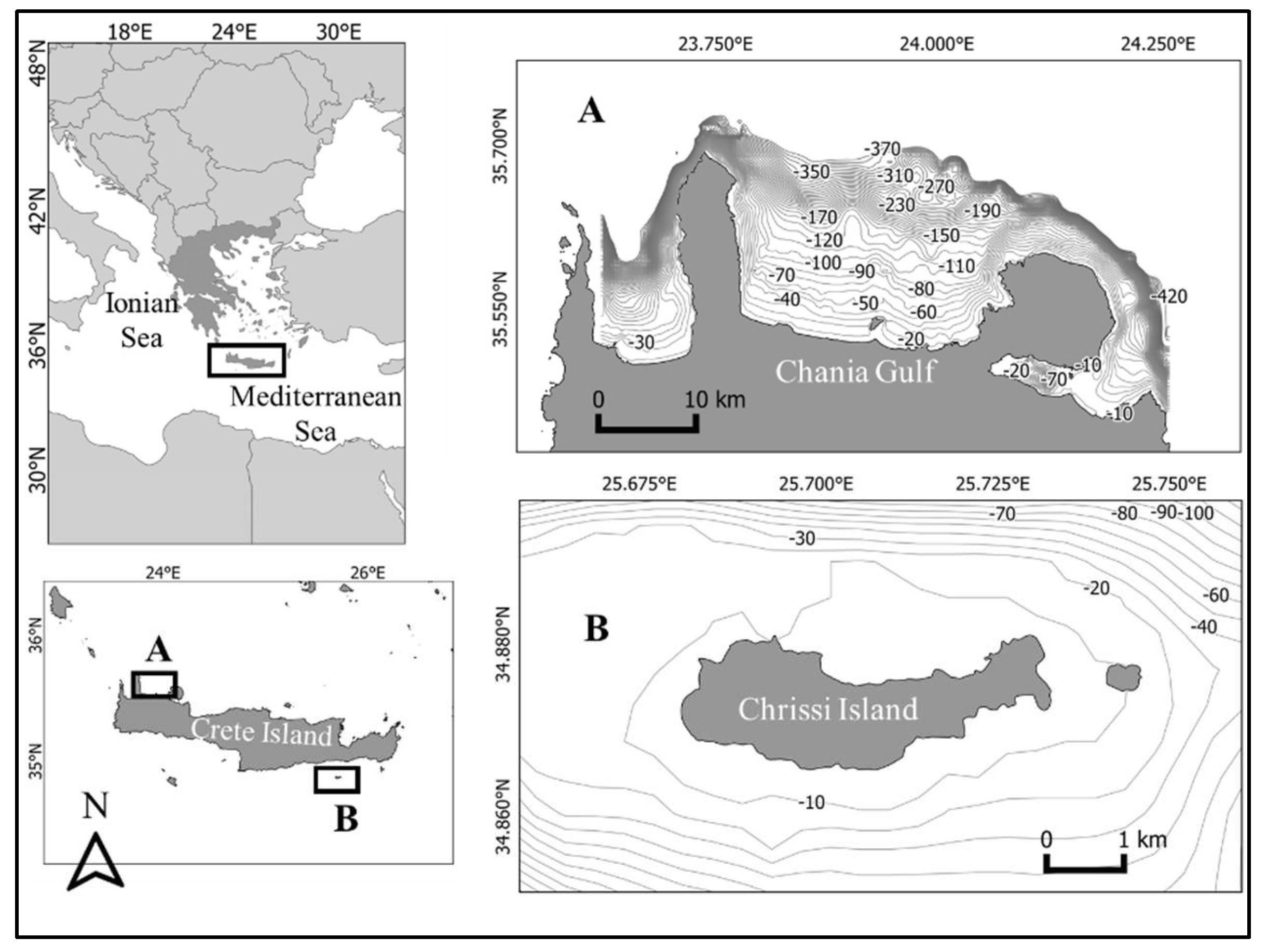

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Satellite Data

2.3. Field Data

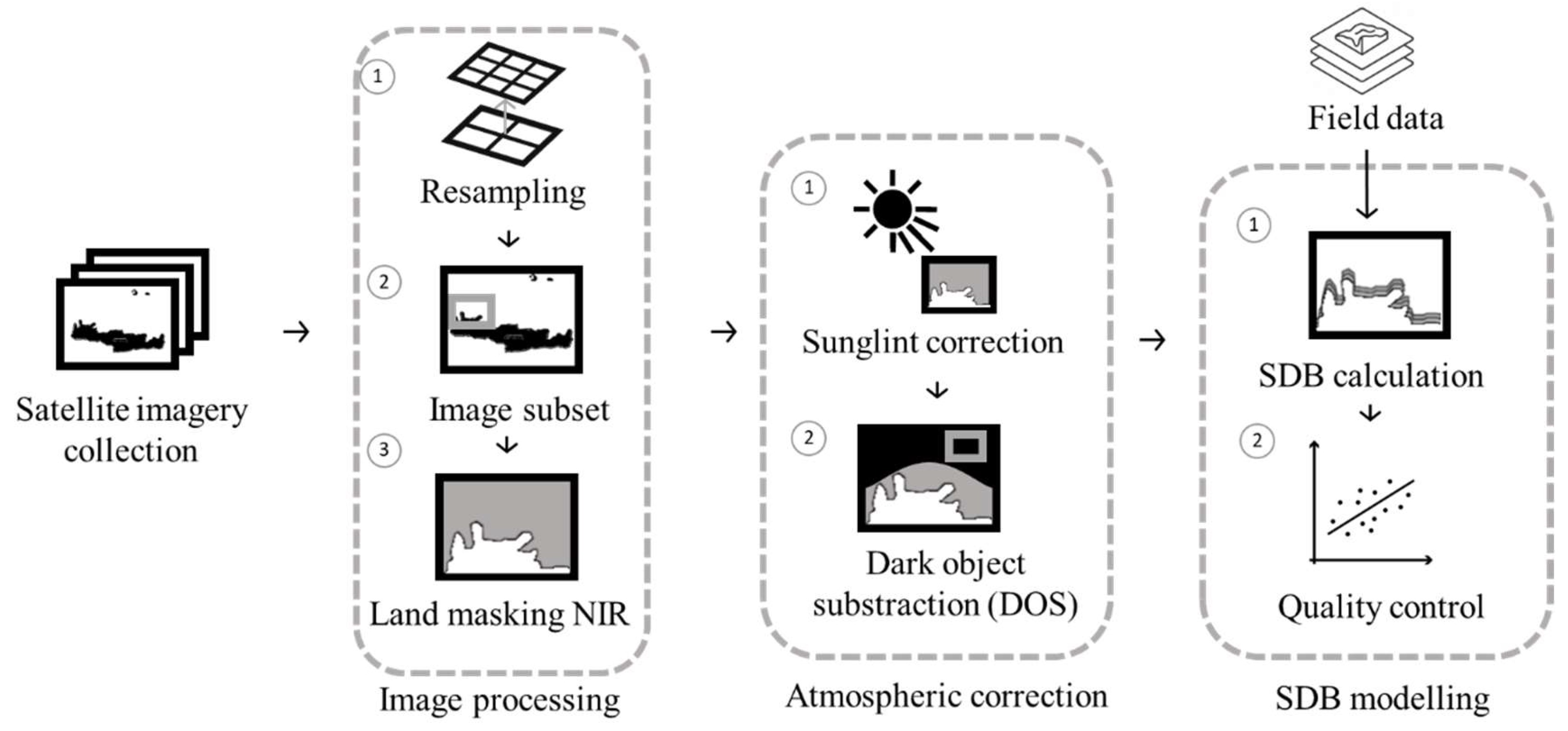

3. Methods

3.1. Empirical Satellite-Derived Bathymetry (SDB)

3.2. Kalman Filter (KF) Smoothing

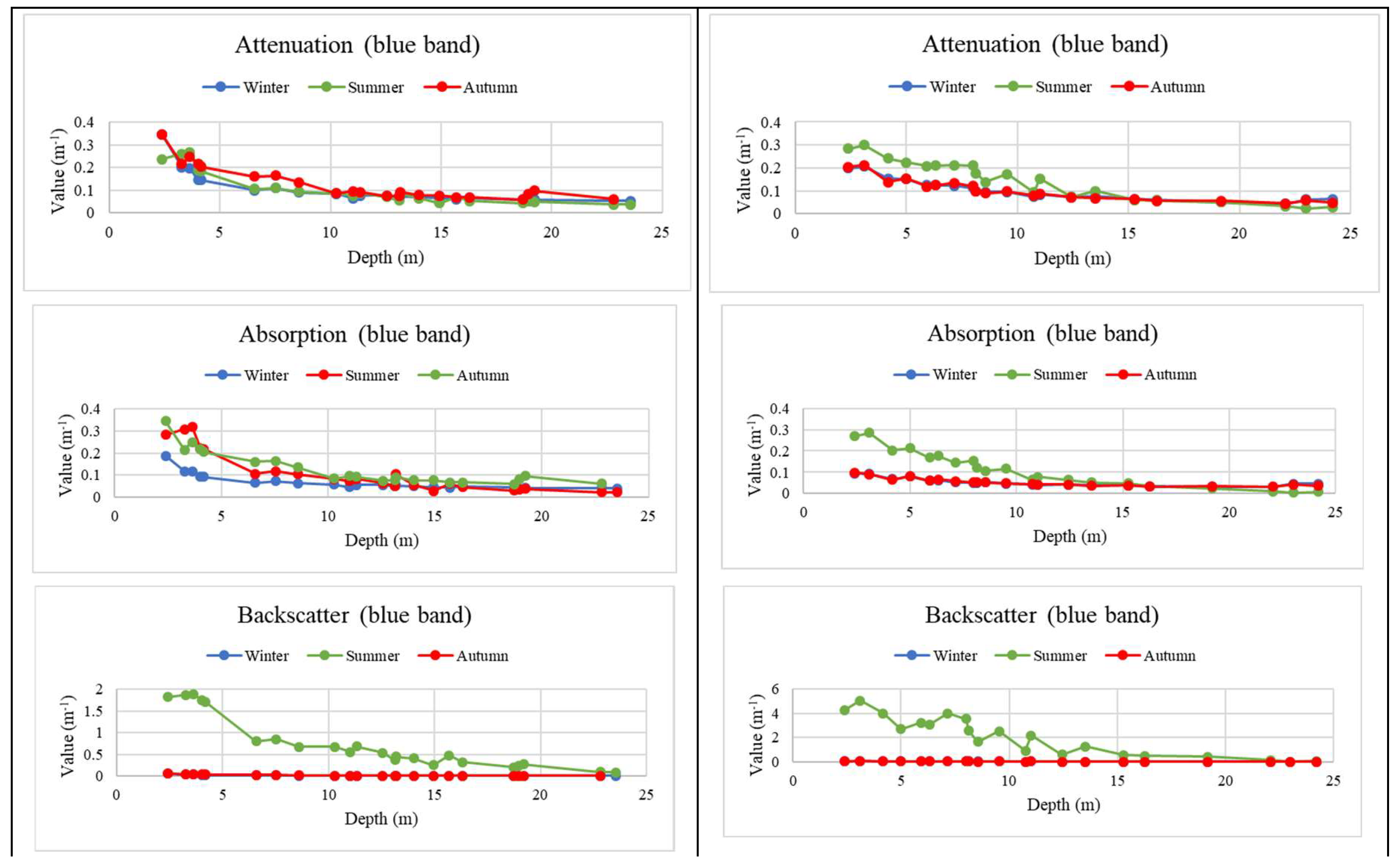

3.3. Water Optical Properties

3.3. Workflow

4. Results and Discussion

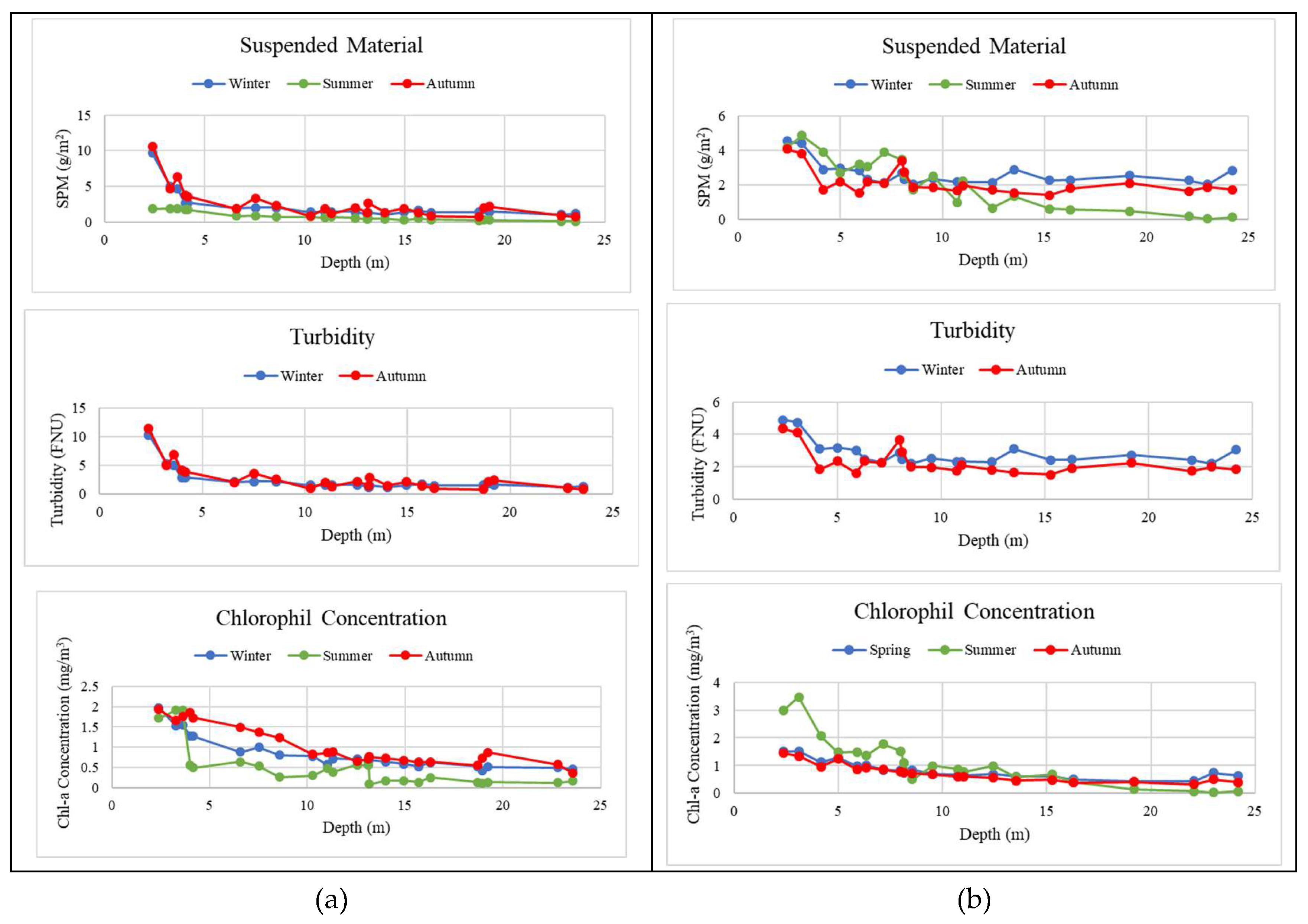

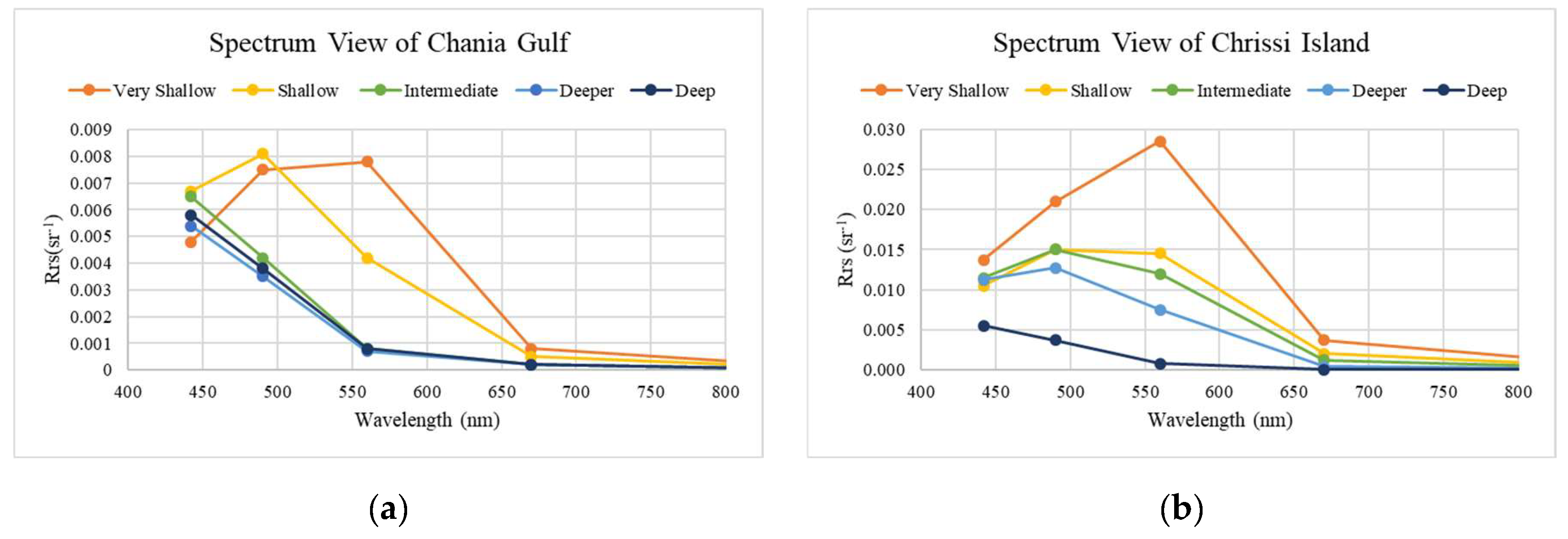

4.2. Water Optical Properties Analysis

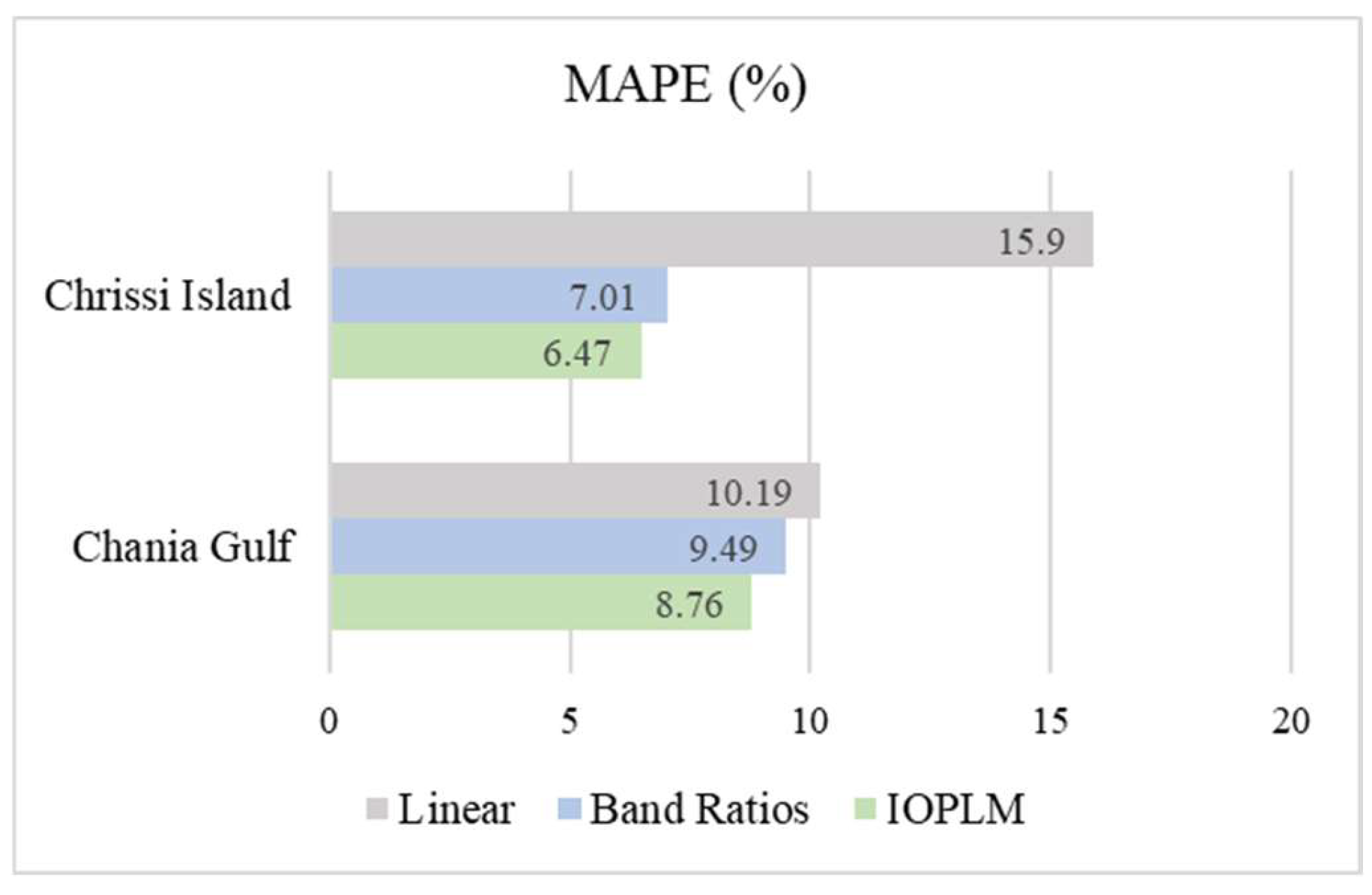

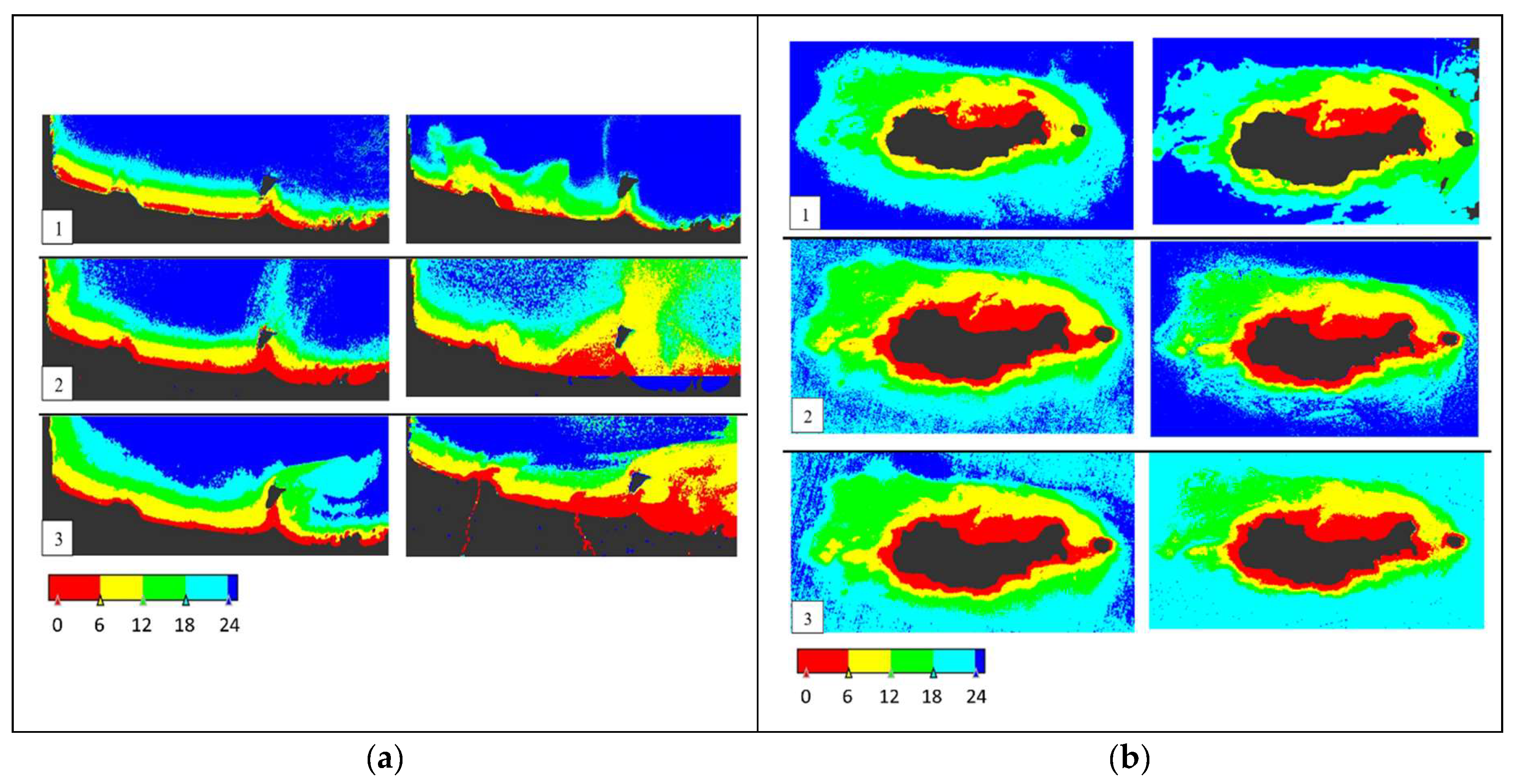

4.1. SDB Model

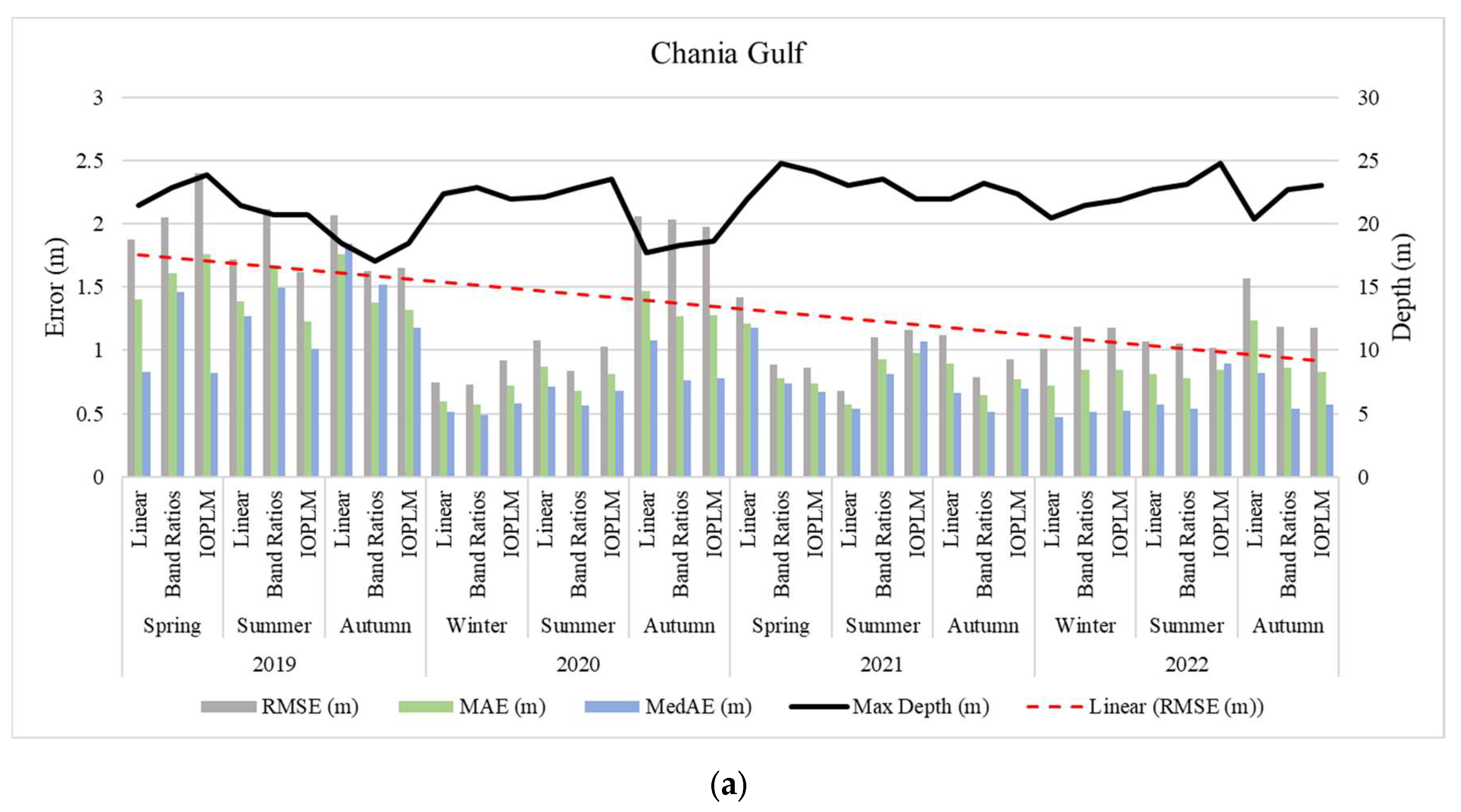

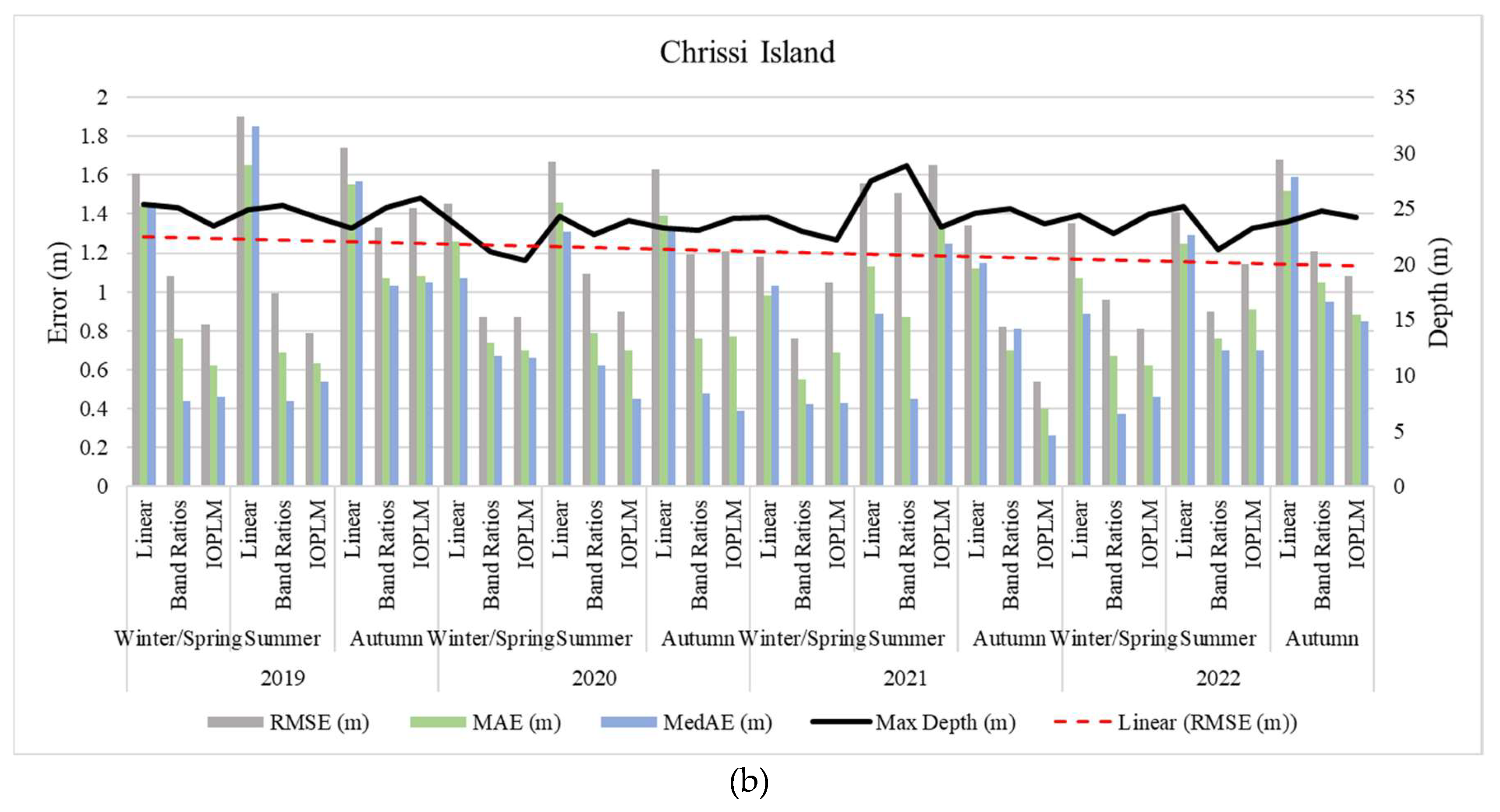

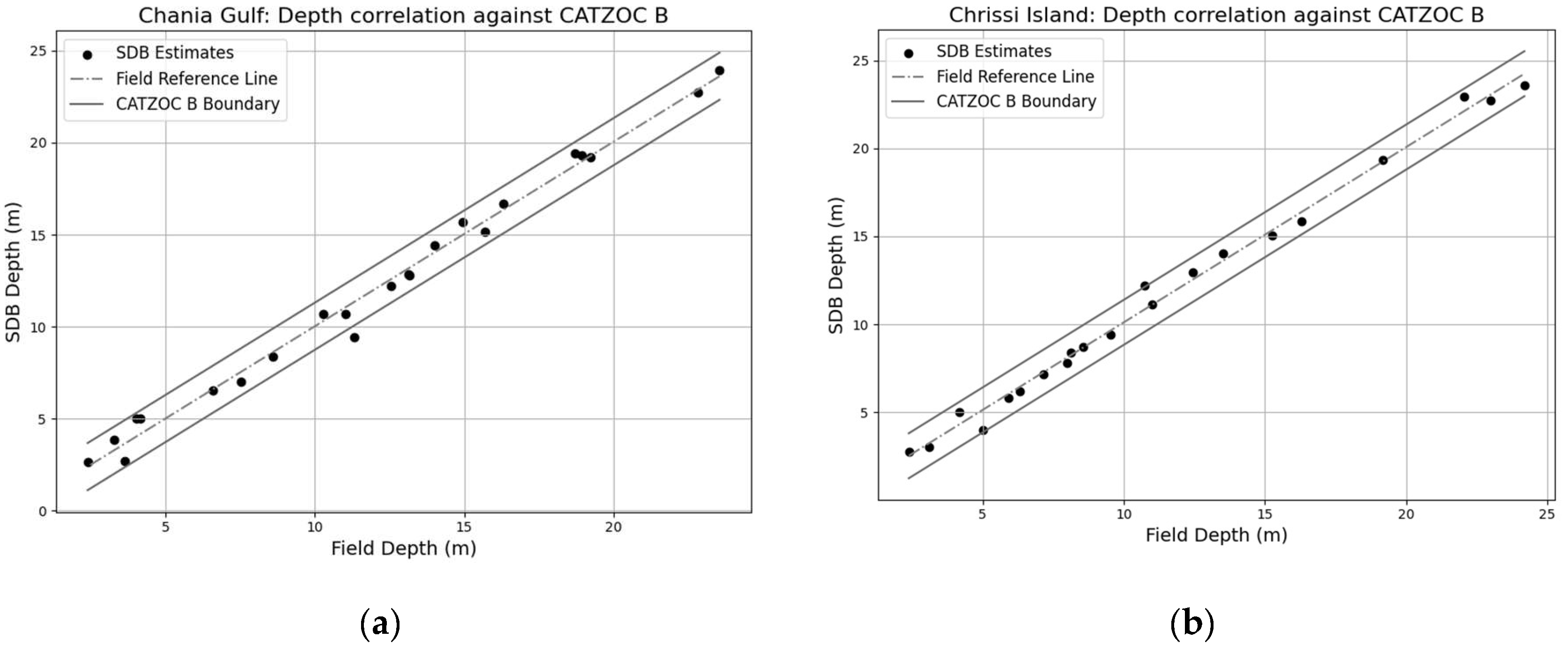

4.3. Assessment of Model Accuracy

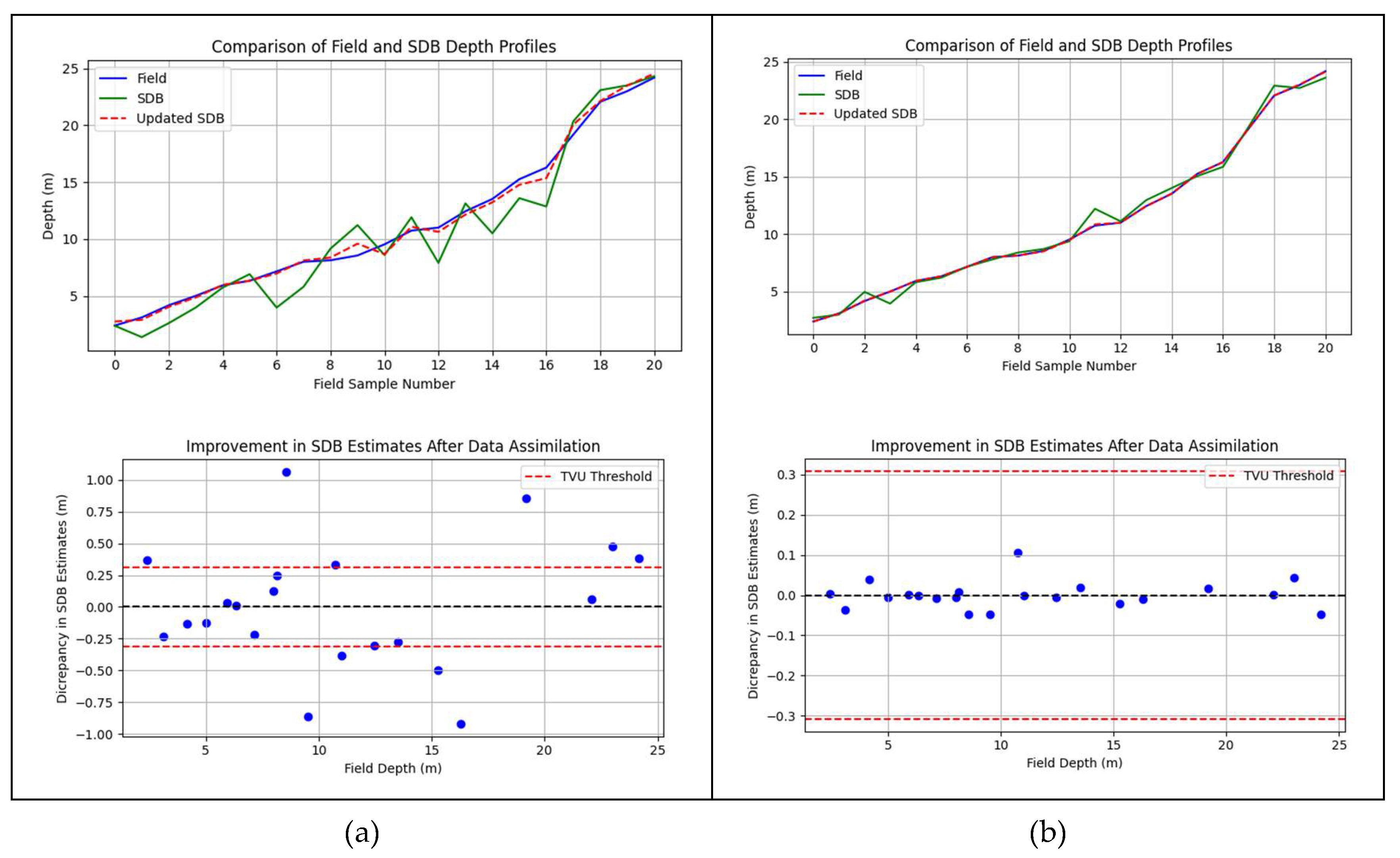

4.4. Kalman Filter (KF)

5. Conclusions

6. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashphaq, M.; Srivastava, P.K.; Mitra, D. Review of Near-Shore Satellite Derived Bathymetry: Classification and Account of Five Decades of Coastal Bathymetry Research. J. Ocean Eng. Sci. 2021, 6, 340–359. [CrossRef]

- Louvart, P.; Cook, H.; Smithers, C.; Laporte, J. A New Approach to Satellite-Derived Bathymetry: An Exercise in Seabed 2030 Coastal Surveys. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, R.P.; Holderied, K.; Spring, S.; Sinclair, M. Determination of Water Depth with High-Resolution Satellite Imagery over Variable Bottom Types. 2003, 48, 547–556.

- Lyzenga, D. Passive Remote-Sensing Techniques for Mapping Water Depth and Bottom Features. Appl. Opt. 1978. [CrossRef]

- Jupp, D. International Journal of Remote Reconstruction of Sand Wave Bathymetry Using Both Satellite Imagery and Multi-Beam Bathymetric Data : A Case Study of the Taiwan Banks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Symposium on Remote Sensing of the Coastal Zone; Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, 1988.

- Lee, Z.; Carder, K.L.; Arnone, R.A. Deriving Inherent Optical Properties from Water Color: A Multiband Quasi-Analytical Algorithm for Optically Deep Waters. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 5755. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J. Shallow Water Bathymetry Based on Inherent Optical Properties Using High Spatial Resolution Multispectral Imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Streftaris, N.; Zenetos, A.; Papathanassiou, E. Globalisation in Marine Ecosystems: The Story of Non-Indigenous Marine Species across European Seas. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 2005, 43, 419–453. [CrossRef]

- Mandlburger, G. A Review of Active and Passive Optical Methods in Hydrography. Int. Hydrogr. Rev. 2022, 28, 8–52. [CrossRef]

- Chaikalis, S.; Parinos, C.; Möbius, J.; Gogou, A.; Velaoras, D.; Hainbucher, D.; Sofianos, S.; Tanhua, T.; Cardin, V.; Proestakis, E.; et al. Optical Properties and Biochemical Indices of Marine Particles in the Open Mediterranean Sea: The R/V Maria S. Merian Cruise, March 2018. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Drakopoulou, P.; Kapsimalis, V.; Parcharidis, I.; Pavlopoulos, K. Retrieval of Nearshore Bathymetry in the Gulf of Chania, NW Crete, Greece, from WorldWiew-2 Multispectral Imagery. 2018, 54. [CrossRef]

- .

- 2022; 13. ESA S2 MSI ESL Team COPERNICUS SPACE COMPONENT SENTINEL OPTICAL IMAGING MISSION PERFORMANCE CLUSTER SERVICE Sentinel-2 Annual Performance Report-Year 2022; 2023;

- Lyzenga, D. Shallow-Water Bathymetry Using Combined Lidar and Passive Multispectral Scanner Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1985, 6, 115–125. [CrossRef]

- Philpot, W.D. Bathymetric Mapping with Passive Multispectral Imagery. Appl. Opt. 1989, 28, 1569. [CrossRef]

- .

- Ribeiro, M.I. Kalman and Extended Kalman Filters : Concept , Derivation and Properties. In Institute for Systems and Robotics Lisboa Portugal; 2004; p. 42.

- Mobley, C.D.; Stramski, D.; Paul Bissett, W.; Boss, E. Optical Modeling of Ocean Waters: Is the Case 1 - Case 2 Classification Still Useful? Oceanography 2004, 17, 60–67. [CrossRef]

- Mobley, C.D. The Oceanic Optics Book. Int. Ocean Colour Coord. Gr. Dartmouth, NS, Canada 2022, 924. [CrossRef]

- Mavraeidopoulos, A.K. Satellite Derived Bathymetry with No Use of Field Data. Int. Sci. Conf. Des. Manag. Harb. Coast. Offshore Work. 2023, 1–8.

- Mavraeidopoulos, A.K.; Oikonomou, E.; Palikaris, A.; Poulos, S. A Hybrid Bio-Optical Transformation for Satellite Bathymetry Modeling Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Chavez, P.S. An Improved Dark-Object Subtraction Technique for Atmospheric Scattering Correction of Multispectral Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 1988, 24, 459–479. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.A.; Lee, Z.P.; Ustin, S.L. Influence of Atmospheric and Sea-Surface Corrections on Retrieval of Bottom Depth and Reflectance Using a Semi-Analytical Model: A Case Study in Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii. Appl. Opt. 2008, 47. [CrossRef]

- Traganos, D.; Poursanidis, D.; Aggarwal, B.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Reinartz, P. Estimating Satellite-Derived Bathymetry (SDB) with the Google Earth Engine and Sentinel-2. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Hedley, J.D.; Harborne, A.R.; Mumby, P.J. Simple and Robust Removal of Sun Glint for Mapping Shallow-Water Benthos. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 2107–2112. [CrossRef]

- 2 August 2021; 26. RBINS ACOLITE User Manual (QV - August 2,2021); Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS), Belgium, 2021;

- Vanhellemont, Q. Adaptation of the Dark Spectrum Fitting Atmospheric Correction for Aquatic Applications of the Landsat and Sentinel-2 Archives. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 225, 175–192. [CrossRef]

- Doerffer, R.; Schiller, H. The MERIS Case 2 Water Algorithm. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2007, 28, 517–535. [CrossRef]

- Brockman, C.; Doerffer, R.; Peters, M.; Stelzer, K.; Embacher, S.; Ruescas, A. Evolution of the C2RCC Neural Network for Sentinel 2 and 3 for the Retrieval of Ocean Colour Products in Normal and Extreme Optically Complex Waters. 2004, 1–14.

- Hollingsworth, A.; Engelen, R.J.; Textor, C.; Benedetti, A.; Boucher, O.; Chevallier, F.; Dethof, A.; Elbern, H.; Eskes, H.; Flemming, J.; et al. Toward a Monitoring and Forecasting System for Atmospheric Composition: The GEMS Project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2008, 89, 1147–1164. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, I.; Stumpf, R.P. Atmospheric Correction for Satellite-Derived Bathymetry in the Caribbean Waters: From a Single Image to Multi-Temporal Approaches Using Sentinel-2A/B. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 11742. [CrossRef]

- Nechad, B.; Ruddick, K.G.; Neukermans, G. Calibration and Validation of a Generic Multisensor Algorithm for Mapping of Turbidity in Coastal Waters. Remote Sens. Ocean. Sea Ice, Large Water Reg. 2009 2009, 7473, 74730H. [CrossRef]

- Nechad, B.; Ruddick, K.G.; Park, Y. Calibration and Validation of a Generic Multisensor Algorithm for Mapping of Total Suspended Matter in Turbid Waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 854–866. [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) or Mean Absolute Error (MAE)? -Arguments against Avoiding RMSE in the Literature. Geosci. Model Dev. 2014, 7, 1247–1250. [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J.; Matsuura, K. Advantages of the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) over the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) in Assessing Average Model Performance. Clim. Res. 2005, 30, 79–82. [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S. Accuracy Measures: Theoretical and Practical Concerns. Int. J. Forecast. 1993, 9, 527–529. [CrossRef]

- I: S-44 6th Edition, 2020; 37. IHO S-44 6th Edition: IHO Standards For Hydrographic Surveys; Monaco, 2020;

- Ghorbanidehno, H.; Lee, J.; Farthing, M.; Hesser, T.; Kitanidis, P.K.; Darve, E.F. Novel Data Assimilation Algorithm for Nearshore Bathymetry. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2019, 36, 699–715. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Pertiwi, A.P.; Traganos, D.; Lagomasino, D.; Poursanidis, D.; Moreno, S.; Fatoyinbo, L. Space-Borne Cloud-Native Satellite-Derived Bathymetry (SDB) Models Using ICESat-2 And Sentinel-2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, H.; Nadaoka, K.; Nakamura, T. Towards Benthic Habitat 3D Mapping Using Machine Learning Algorithms and Structures from Motion Photogrammetry. 2020.

- Herrmann, J.; Magruder, L.A.; Markel, J.; Parrish, C.E. Assessing the Ability to Quantify Bathymetric Change over Time Using Solely Satellite-Based Measurements. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

| Year | Season | Sensing Date (UTC time) | Cloud Coverage (%) | Sun Zenith Angle (degree) | Sun Azimuth Angle (degree) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 19-Mar-2019 / 09:10:46 | 0.2309 | 39.50 | 149.45 | |

| 2019 | Summer | 21-Aug-2019 / 09:10:50 | 0.1704 | 27.70 | 140.30 |

| Autumn | 25-Oct-2019 / 09:10:48 | 0 | 48.36 | 163.00 | |

| Winter | 23-Jan-2020 / 09:10:41 | 0.8564 | 57.44 | 157.70 | |

| 2020 | Summer | 30-Aug-2020 / 09:10:51 | 0 | 30.28 | 145.03 |

| Autumn | 13-Nov-2020 / 09:10:51 | 0.9878 | 54.27 | 164.79 | |

| Spring | 13-Mar-2021 / 09:10:47 | 0.1587 | 41.63 | 150.29 | |

| 2021 | Summer | 30-Aug-2021 / 09:10:49 | 0 | 30.21 | 144.91 |

| Autumn | 24-Oct-2021 / 09:10:49 | 0 | 48.20 | 162.93 | |

| Winter | 11-Feb-2022 / 09:10:42 | 0.3548 | 52.44 | 154.67 | |

| 2022 | Summer | 20-Aug-2022 / 09:10:19 | 0 | 27.53 | 139.93 |

| Autumn | 04-Oct-2022 / 09:10:54 | 1.3555 | 41.31 | 158.50 |

| SDB Method | Metric | Value (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Linear | RMSE | 1.81 |

| RMSE updated | 0.47 | |

| MAE | 1.48 | |

| MAE updated | 0.37 | |

| MedAE | 1.16 | |

| MeadAE updated | 0.30 | |

| IOPLM | RMSE | 0.54 |

| RMSE updated | 0.05 | |

| MAE | 0.40 | |

| MAE updated | 0.04 | |

| MedAE | 0.27 | |

| MeadAE updated | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).