Introduction

Coastal sedimentary nearshore environments inherently exhibit a dynamic nature, displaying variations in both time and space. These environments are comprised of both sub- and supra-aqueous zones, and their morphology is shaped by the existing geology, topography, sediment supply and sea level, and forced by a range of oceanographic and geologic processes [

1]. These processes occur on both short and long-term time-scales and drive geomorphic evolution, and they include sea level rise; tides and currents; storm magnitude, frequency, direction, and duration; wind, climatic cycles (e.g. Southern Annular Mode); sand type and supply; and tectonic uplift and subsidence of the coastal zone [

2].

Forecasting the evolution of nearshore sedimentary environments as they respond to variations in oceanographic and geologic processes is crucial for ensuring the resilience of coastal areas in the context of climate change. Predictive models like Delft3D and X-beach have been utilised to aid understanding of shoreline change. However, these models are limited by the costly input of up-to-date medium-resolution (1-10m) bathymetric grids and the validation of model outputs through repeat bathymetric surveys [

1]. Conventionally, echo sounders and airborne Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) bathymetric systems have been utilised to capture these datasets. These are high-precision technologies that are essential for obtaining precise bathymetric information (i.e. within a few centimetres) [

3,

4], capable of meeting International Hydrographic Organization Standards for Hydrographic Survey [

5]. However, these methods have inherent limitations in terms of cost and time constraints [

6] and the dynamic nature of the nearshore potentially renders the outputs dataset outdated shortly after the survey has concluded. These cost and time restraints often result in spatially sparse bathymetric observations being interpolated over large distances, with vertical uncertainty being introduced [

7]. In contrast, satellite-derived bathymetry (SDB) is cost-effective, non-intrusive, able to survey remote locations, capable of extensive coverage, spatially and temporally continuous, and repeatable at user-defined intervals [

8]. Hence, it is a more efficient mechanism for obtaining bathymetric information, albeit with large error margins (root mean square error (RMSE) ~1m) [

1,

6,

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, SDB may not be suitable for all applications, such as maritime construction or port surveys; however, it is well-suited for coastal monitoring and modelling purposes, where its utility is maximised.

SDB is inferred from both passive and active space-borne sensors, although, more commonly from passive imaging sensors [

12]. Passive methods (the focus of this research) relate water leaving radiance to depth based on the Beer-Lambart Law (Eq. 1) which proposes an exponential relationship between the attenuation of light in water and water depth [

13]. This law suggests that the remaining water leaving radiance (

Id) in a medium (pure water) is a function of incident light intensity (I

0) and reduces with increased passage (

p). It is also dependent on the specific attenuation coefficient (

k) which varies with wavelength. This is expressed by:

Along with SDB being limited by depth, SDB is also limited by other factors that prohibit electromagnetic energy from interacting with the seafloor and being reflected to space-based sensors, including excess turbidity, high sea-states, sea-surface reflectance, and atmospheric scattering [

14]. Complex mixed bottom types with spatially variant albedo further contribute to increased uncertainties.

Within optical SDB literature, there are two major approaches commonly cited; empirical and analytical (physics-based) approaches [

12,

15]. Analytical approaches are based on the radiative transfer of light within a water body and require the input of multiple

in situ measurements, including water quality parameters and seafloor albedo [

15]. Hence, the approach is limited by the requirement of simultaneous

in situ measurements distributed throughout the surveyed area at the time of image capture to account for the fluctuating and spatially variant nature of the nearshore environment [

8,

15].

Empirical approaches, rather than solving depth based on the physics of light attenuation through a defined medium, typically employ linear and non-linear regressions to estimate depth based solely on corresponding depth observations and the reflectance of single or multiple bands [

12]. Traditional empirical approaches in contrast to analytical approaches are simpler to implement and although not as accurate as analytical approaches in heterogeneous environmental conditions, do produce quality results in homogenous environments and at depths less than 20m [

15].

An evaluation of SDB dataset quality in an optically shallow, mixed bottom, low wave energy coastal environment derived from diverse space-borne multi-spectral sensors, each possessing unique spectral properties and spatial resolutions, and estimated using different empirical techniques, would greatly assist coastal practitioners both globally and locally, enabling the capture of optimised, cost-effective, spatially, and temporally extensive bathymetric grids. This would increase the capacity to monitor and model coastal sedimentary responses to sea level rise in similar environments and enable coastal practitioners to best manage beach amenity, coastal infrastructure, and coastal ecology on optically shallow, mixed bottom, low wave energy coasts. However, such studies are currently limited in number and scope, warranting further investigation.

Review papers of existing literature do provide meta-analysis of the mean correlation coefficient and RMSE values of many major derivation techniques in a range of coastal environments [

3,

12]. However, these reviews are constrained by the limited publication of spectral information used in the SDB derivations and the extensive timescale of the sourced literature, leading to a disparity in imaging quality (spatially, spectrally, and radiometrically). More recent work by Evagorou

et al. [

6] made significant headway in determining an optimised SDB derivation method for a similar environment by empirically testing the best combination of input satellite imagery, input spectral bands, and derivation techniques. However, Evagorou

et al. [

6] utilised conventional PlanetScope 4-band imagery instead of exploring the potentially superior PlanetScope SuperDove constellation, which offers enhanced spectral resolution in the visible spectrum [

16]. This highlights the need for further investigation to fully leverage these advancements.

Furthermore, the relationship between the number of input bands, their spatial resolution, and their specific spectral properties (central wavelength and bandwidth) with output SDB dataset quality remains unknown. Evagorou

et al. [

6] identified that the impact of spatial resolution of satellite imagery on SDB quality should be a subject of future work. Similarly, the influence of improved spectral sampling of the visible spectrum on dataset quality remains uncertain. While most studies traditionally use green and blue wavelengths for SDB derivations due to their lower absorption by the water column than other visible wavelengths [

17,

18,

19], recent observations suggest that providing more input spectral data to machine learning algorithms enhances accuracy, prompting a shift towards the use of hyper-spectral data for SDB derivations [

20,

21]. Questions remain as to whether this applies to SDB derivations performed with traditional derivation techniques.

This research aims to enhance the accuracy of optical SDB datasets utilising empirical techniques in an optically shallow, mixed bottom, low wave energy coastal environment. The study determines an optimal SDB derivation method based on a selection of the best-performing combination of three critical variables; the input satellite imagery, each with unique spatial resolutions and spectral properties (Sentinel-2, Pleiades Neo & PlanetScope SuperDove); the input spectral bands utilised in the SDB derivation; and the empirical derivation technique itself (multiband linear and band ratio). Furthermore, the research aims to describe how the number of input bands, their spatial resolution, and their specific spectral properties (central wavelength and bandwidth) influence dataset quality (RMSE).

The objectives are as follows:

Identification of the optimal combination of variables for generating accurate bathymetric datasets within a small sub-site.

Determination of a parsimonious model to estimate dataset quality (RMSE) based on predictor variables spatial resolution and spectral suitability of input bands. Where spectral suitability is a metric of spectral resolution given the coastal water application.

Validation of the optimised SDB dataset performance across diverse conditions within a broader study site, including different bottom types and varying depths.

Materials and Methods

Study Area—Adelaide Metropolitan Coast

The research was conducted along the Adelaide Metropolitan Coastline located within the Gulf St Vincent, extending from the water line to 3km offshore (100km

2) (

Figure 1). The sediments in the region are characterised by mixed terrigenous-carbonate sands, dominated by biogenic carbonate including bryozoans, coralline algae, molluscs and foraminifera [

22]. Sediments are transported northward by longshore drift, driven by oblique wave impact upon the coast at a rate of 100,000m

3/yr [

23,

24]. Multiple bottom types are present, including, seagrass meadow

(Posidonia and

Amphibolis), bare sand, and limestone reefs [

23].

The site was chosen for several compelling reasons. Primarily, the coastline experiences low wave breaker energy, as Kangaroo Island blocks large swells generated in the Southern Ocean [

25]. Typical significant wave height (Hs) ranging from 0.01 to 0.5m (

Figure 1). These conditions are favourable for SDB applications, as increased wave action leads to increased whitewash and suspended sediments, both of which reduce the penetration of sunlight into the water column. Secondarily, this site benefits from the availability of annual nearshore bathymetric surveys conducted by the South Australian Coast Protection Board, contributing a substantial dataset that serves as valuable ground truth for evaluating the accuracy and reliability of the optimised SDB datasets. Additionally, this coastline is both heavily developed and significantly impacted by erosion on the downdrift side of artificial structures. To maintain beaches in this contested environment sand nourishment, sand recycling and sand bypassing are being utilised [

26]. Therefore, this was a valuable opportunity to bolster bathymetric data collection capability in a vulnerable coastal environment.

While SDB technology enables surveying of extensive coastlines, to optimise workflow a smaller representative 1.2km

2 sub-site was selected 5km south of the Port Adelaide River Mouth (

Figure 1). The choice of this sub-site was based on several criteria, including, access to existing satellite imagery in the region; the representativeness of the sub-site in terms of bottom type characteristics and slope, ensuring it aligned with the broader Adelaide coast's characteristics; and the ability to capture bathymetric LiDAR data in that location.

Figure 1.

Insert A depicts the study site’s regional setting within the Australian continent. Insert B displays the study site’s regional location, centred around the Gulf St Vincent along with a wave rose depiction of local swell conditions recorded over the past two years [

27]. The broader study site’s spatial extent and bathymetric contours [

28] are depicted in insert C. Also within insert C is a red rectangle displaying the location of the sub-site.

Figure 1.

Insert A depicts the study site’s regional setting within the Australian continent. Insert B displays the study site’s regional location, centred around the Gulf St Vincent along with a wave rose depiction of local swell conditions recorded over the past two years [

27]. The broader study site’s spatial extent and bathymetric contours [

28] are depicted in insert C. Also within insert C is a red rectangle displaying the location of the sub-site.

Multi-Resolution Optical Datasets

The study utilised wavelengths within the visible spectrum associated with satellite imagery from three distinct spaceborne multi-spectral instruments: Sentinel-2 (10m), PlanetScope SuperDove (3m), and Pléiades Neo (1.2m), offering unique spatial resolutions (pixel size) and spectral resolutions (number of bands and sampled portion of electromagnetic spectrum) (

Table 1). In addition to selection based upon unique spatial and spectral resolutions, these satellites were chosen in part due to cost and the availability of archival imagery simultaneous with

in situ data collection (Section 2.3). Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope SuperDove satellite imagery were obtained freely from Copernicus Browser and Planet Explorer archives respectively; in the case of the PlanetScope SuperDove, this data is only free of charge with an education and research license. Pleiades Neo imagery was obtained from AirBus through a tasked capture, with a reduced cost for research purposes. Further sensor technical details are provided in

Appendix A.

To obtain the best quality imagery the following criteria were considered:

The prevalence of cloud cover within the imagery.

The date of image capture relative to in situ data collection (16th of January 2024 – see Section 2.3).

Visible effects of sunglint over water.

Visible effects of sea state.

Visible effects of turbidity.

Considering the above criteria, an optimal multi-spectral image from each satellite provider was chosen, the details of which are listed in

Table 2. These three multi-spectral images were collected within twelve minutes, ensuring minimal variability in environmental conditions. To facilitate fair comparison, each image was obtained at an equivalent surface reflectance level. All datasets were then reprojected to the Geocentric Datum of Australia 2020 (GDA2020) with a Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) projection centred around zone 54 south.

Figure 2.

The spatial distribution of cross-shore profiles extending 1.5km seaward at 1km intervals. Profiles are numbered from 200001 in the north to 200029 in the south.

Figure 2.

The spatial distribution of cross-shore profiles extending 1.5km seaward at 1km intervals. Profiles are numbered from 200001 in the north to 200029 in the south.

Figure 3.

The frequency distribution of in situ depth data resampled to the pixel size of PlanetScope SuperDove cells (3m) within the sub-site. The distribution is identified as bimodal. Some transparency has been applied to the calibration symbology so an overlap between the two classes may be observed.

Figure 3.

The frequency distribution of in situ depth data resampled to the pixel size of PlanetScope SuperDove cells (3m) within the sub-site. The distribution is identified as bimodal. Some transparency has been applied to the calibration symbology so an overlap between the two classes may be observed.

Figure 4.

An overview of technical methods followed to generate and assess the quality of SDB datasets. .

Figure 4.

An overview of technical methods followed to generate and assess the quality of SDB datasets. .

Figure 5.

The frequency distribution of in situ depth data resampled to the pixel size of PlanetScope SuperDove cells (3m) within the study site.

Figure 5.

The frequency distribution of in situ depth data resampled to the pixel size of PlanetScope SuperDove cells (3m) within the study site.

Figure 6.

Before (A) and after (B) the sunglint correction is applied over Pleiades Neo RGB satellite imagery. The imagery is stretched using a minimum/maximum stretch over the displayed extent.

Figure 6.

Before (A) and after (B) the sunglint correction is applied over Pleiades Neo RGB satellite imagery. The imagery is stretched using a minimum/maximum stretch over the displayed extent.

Figure 7.

Depiction of the impact of sunglint correction in shallow water where NIR bottom reflectance is present. Spectral profiles are extracted from the Pleiades Neo multi-spectral image along profile 200015. Spectral profiles have been extracted before sunglint correction was applied, and after sunglint correction was applied. Associated Pleiades Neo RGB satellite imagery is stretched using a minimum/maximum stretch over the marine inundated areas in the displayed extent.

Figure 7.

Depiction of the impact of sunglint correction in shallow water where NIR bottom reflectance is present. Spectral profiles are extracted from the Pleiades Neo multi-spectral image along profile 200015. Spectral profiles have been extracted before sunglint correction was applied, and after sunglint correction was applied. Associated Pleiades Neo RGB satellite imagery is stretched using a minimum/maximum stretch over the marine inundated areas in the displayed extent.

Figure 8.

A depiction of the bathymetric LiDAR surface generated seaward of the shoreline at the time of multi-spectral image capture and its comparison with available SoNAR data within the sub-site (Profile 200004) captured on the same day. All elevations given are in relation to Australian Height Datum (AHD) (m). Pleiades Neo red-green-blue (RGB) imagery underlies the bathymetric raster.

Figure 8.

A depiction of the bathymetric LiDAR surface generated seaward of the shoreline at the time of multi-spectral image capture and its comparison with available SoNAR data within the sub-site (Profile 200004) captured on the same day. All elevations given are in relation to Australian Height Datum (AHD) (m). Pleiades Neo red-green-blue (RGB) imagery underlies the bathymetric raster.

Figure 9.

Comparison between TPXO 9 global tide model and the observed sea-surface height along the length of the study site.

Figure 9.

Comparison between TPXO 9 global tide model and the observed sea-surface height along the length of the study site.

Figure 10.

Boxplots depicting RMSE values for different combinations of satellite imagery and derivation techniques. mean (x̄), third quartile (Q3), and maximum.

Figure 10.

Boxplots depicting RMSE values for different combinations of satellite imagery and derivation techniques. mean (x̄), third quartile (Q3), and maximum.

Figure 11.

Depth at time of image capture inferred from the optimised derivation (multiband linear technique on PlanetScope SuperDove using, G-alt, G and Y Bands) plotted against validation data present within the sub-site.

Figure 11.

Depth at time of image capture inferred from the optimised derivation (multiband linear technique on PlanetScope SuperDove using, G-alt, G and Y Bands) plotted against validation data present within the sub-site.

Figure 12.

A depiction of the optimal SDB surface within the sub-site which represents depth at the time of image capture and a comparison with available tidally corrected validation data along profile 200004. Pleiades Neo RGB imagery underlies the bathymetric raster.

Figure 12.

A depiction of the optimal SDB surface within the sub-site which represents depth at the time of image capture and a comparison with available tidally corrected validation data along profile 200004. Pleiades Neo RGB imagery underlies the bathymetric raster.

Figure 13.

A 3D representation of the model explaining the greatest variance, incorporating both spectral suitability and pixel size (m). RMSE (m) = 0.1748 + 0.1934 * (Spectral Suitability) + 0.0268 * (Pixel Size (m)).

Figure 13.

A 3D representation of the model explaining the greatest variance, incorporating both spectral suitability and pixel size (m). RMSE (m) = 0.1748 + 0.1934 * (Spectral Suitability) + 0.0268 * (Pixel Size (m)).

Figure 14.

Validation of the optimised dataset across the entire study site using calibration data obtained within the sub-site. The dashed box encapsulates 9.6% of observations where the SDB surface markedly underestimated depth (2-2.75m), these observations are associated with a discrete, higher-albedo sandy substrate in the south of the site. .

Figure 14.

Validation of the optimised dataset across the entire study site using calibration data obtained within the sub-site. The dashed box encapsulates 9.6% of observations where the SDB surface markedly underestimated depth (2-2.75m), these observations are associated with a discrete, higher-albedo sandy substrate in the south of the site. .

Figure 15.

An illustration and quality assessment of the optimised derivation method applied across the entire study site. The first pane depicts the optimised surface restricted between 0.5m and 5m depth at time of image capture.The second pane presents an enlarged view of the three profiles (200001, 200014, 200027) and presents raw imagery, bottom type classification, and the optimised SDB dataset. The third pane details the cross-shore bathymetry from both the satellite derivation and the true depth across the three profiles, along with the difference between the two survey methods on the secondary axis. The landward extent of ‘non-sand’ pixels is shown with the magenta dashed line.Some gaps exist in the SDB estimation because of depth being restricted between 0.5-5m.

Figure 15.

An illustration and quality assessment of the optimised derivation method applied across the entire study site. The first pane depicts the optimised surface restricted between 0.5m and 5m depth at time of image capture.The second pane presents an enlarged view of the three profiles (200001, 200014, 200027) and presents raw imagery, bottom type classification, and the optimised SDB dataset. The third pane details the cross-shore bathymetry from both the satellite derivation and the true depth across the three profiles, along with the difference between the two survey methods on the secondary axis. The landward extent of ‘non-sand’ pixels is shown with the magenta dashed line.Some gaps exist in the SDB estimation because of depth being restricted between 0.5-5m.

Figure 16.

A depiction of the impact of environmental factors (depth and bottom type) upon dataset quality (mean residual error - m). The figure shows mean residual errors (m) recorded in 1m depth classes and grouped by their bottom type.

Figure 16.

A depiction of the impact of environmental factors (depth and bottom type) upon dataset quality (mean residual error - m). The figure shows mean residual errors (m) recorded in 1m depth classes and grouped by their bottom type.

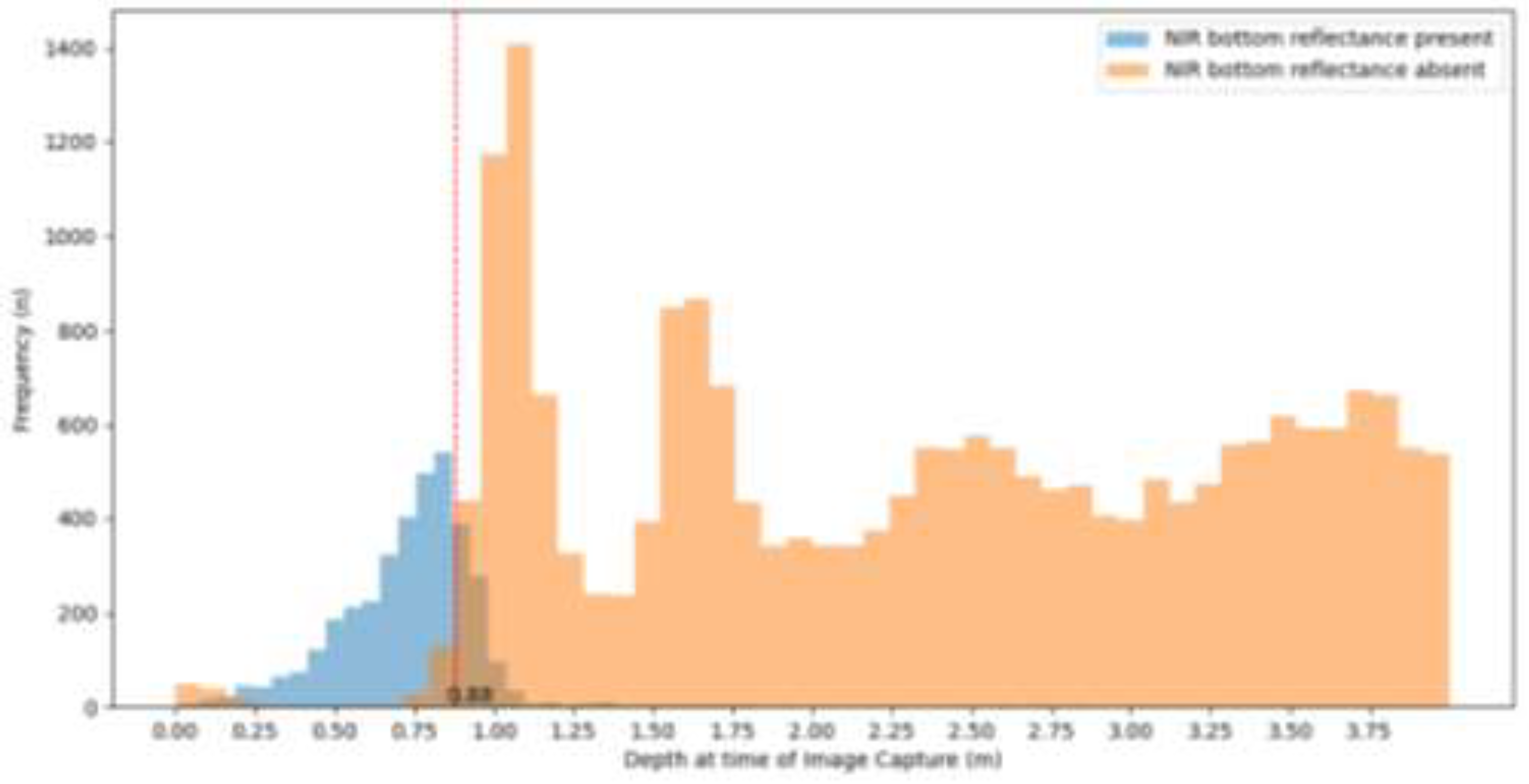

Figure 17.

The frequency distribution of in situ depth data classified by whether the pixel is affected or unaffected by NIR bottom reflectance at time of image capture. Where depth is less than 0.88m most pixel observations were affected by NIR bottom reflectance.

Figure 17.

The frequency distribution of in situ depth data classified by whether the pixel is affected or unaffected by NIR bottom reflectance at time of image capture. Where depth is less than 0.88m most pixel observations were affected by NIR bottom reflectance.

Table 1.

A multi-spectral instrument overview for each of the utilised images within the visible range. Band IDs have been standardised to with a master band ID.

Table 1.

A multi-spectral instrument overview for each of the utilised images within the visible range. Band IDs have been standardised to with a master band ID.

| |

|

Sentinel-2 (10m) |

PlanetScope SuperDove (3m) |

Pléiades Neo (1.2m) |

| Master Band ID |

Band Name |

Band ID |

Wavelength (nm) |

Band ID |

Wavelength (nm) |

Band ID |

Wavelength (nm) |

| 1 |

Deep Blue |

1 |

Discarded due to 60m resolution |

1 |

431-452 |

1 |

400-450 |

| 2 |

Blue |

2 |

459-525 |

2 |

465-515 |

2 |

450-520 |

| 3 |

Green (alt) |

- |

- |

3 |

513-549 |

- |

- |

| 4 |

Green |

3 |

541-577 |

4 |

547-583 |

3 |

530-590 |

| 5 |

Yellow |

- |

- |

5 |

600-620 |

- |

- |

| 6 |

Red |

4 |

649-680 |

6 |

650-680 |

4 |

620-690 |

Table 2.

Metadata of the satellite imagery used in the study

Table 2.

Metadata of the satellite imagery used in the study

| Satellite |

Product ID |

Acquisition Date |

Acquisition Time (UTC +10:30) |

| Sentinel-2 |

S2A_MSIL2A_20240121T003701_N0510_R059_T54HTG_20240121T030545 |

21st Jan 2024 |

11:07:01 |

| PlanetScope SuperDove |

20240121_004724_68_2478_3B_AnalyticMS_8b |

21st Jan 2024 |

11:17:24 |

| Pléiades Neo |

PNEO3_202401210048521_MS-FS_ORT |

21st Jan 2024 |

11:18:52 |

Table 3.

Published georectification residual error.

Table 3.

Published georectification residual error.

| Satellite Image |

Control Points (n) |

Total XY RMSE (m) |

Total XY RMSE (pixel) |

| Pleiades Neo |

10 |

0.48 |

0.4 |

| PlanetScope SuperDove |

87 |

2.77 |

0.92 |

| Sentinel-2 |

70 |

5.4 |

0.54 |

Table 4.

Logging parameters of local tide gauges.

Table 4.

Logging parameters of local tide gauges.

| Tide Gauge ID |

Type |

Events per second (Hz) |

Duration (min) |

Interval (min) |

| 1, 2, 3 |

RBR virtuso3 |

16 |

1 |

5 |

| 4 |

Data Logger Mindata / Hadar 4500 / 555 |

1 |

1 |

5 |

Table 5.

Ranked candidate MLR models used to explain the impact of predictor variables spectral suitability and pixel size (m) upon the response variable RMSE (m).

Table 5.

Ranked candidate MLR models used to explain the impact of predictor variables spectral suitability and pixel size (m) upon the response variable RMSE (m).

| Derivation Technique |

Observations (n) |

Predictor Variables |

Model Equation |

R2

|

AIC |

ER |

| Multiband Linear |

85 |

Spectral Suitability, Pixel Size (m) |

RMSE (m) = 0.1748 + 0.1934 * (Spectral Suitability) + 0.0268 * (Pixel Size (m)) |

0.78 |

-262.6736 |

1 |

| Spectral Suitability |

RMSE (m) = 0.2563 + 0.1976 * (Spectral Suitability) |

0.49 |

-193.5218 |

7.26×1015

|

| Pixel Size (m) |

RMSE (m) = 0.4334 + 0.0277 * (Pixel Size (m)) |

0.31 |

-168.5168 |

3.38×1020

|

| Band Ratio |

24 |

Spectral Suitability, Pixel Size (m) |

RMSE (m) = 1.6484 + -0.2993 * (Spectral Suitability) + 0.0296 * (Pixel Size (m)) |

0.14 |

16.3757 |

1.312 |

| Spectral Suitability |

RMSE (m) = 1.8404 + -0.3624 * (Spectral Suitability) |

0.08 |

15.8323 |

1 |

| Pixel Size (m) |

RMSE (m) = 1.1969 + 0.0359 * (Pixel Size (m)) |

0.08 |

15.8452 |

1.007 |