Submitted:

18 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Polymeric Nanocomposite (PNC) Preparation

2.2.2. Filament Fabrication and FDM 3D-Printing

3. Characterization Tests

3.1. Attenuated Total Reflection—Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

3.2. Thermal Analysis

3.3. Rheological Characteristics

3.4. Electrical Characteristics

3.5. Mechanical Properties

3.6. Morphology and Electrochemical Performance

4. Results and Discussion

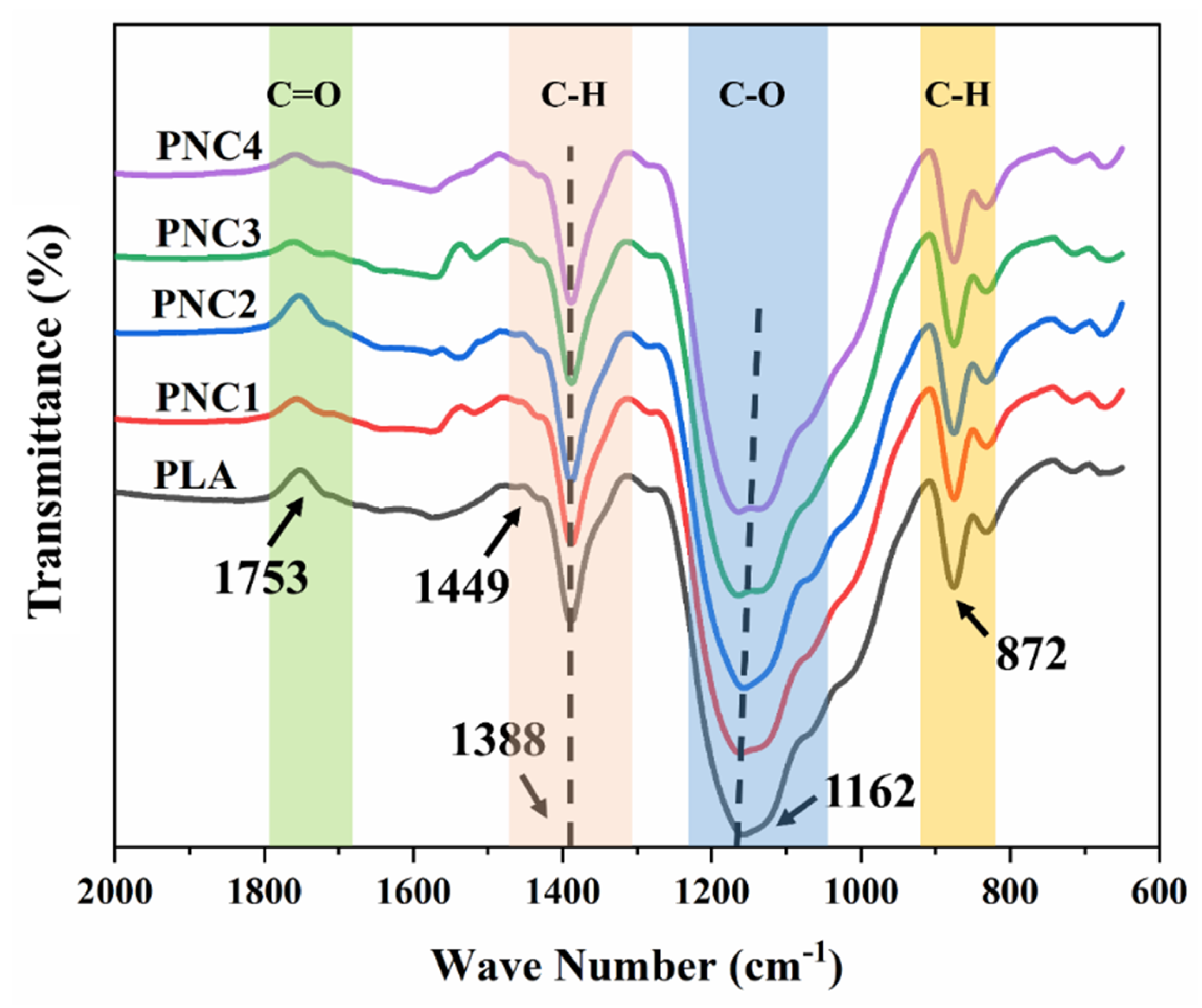

4.1. FT-IR Spectroscopy

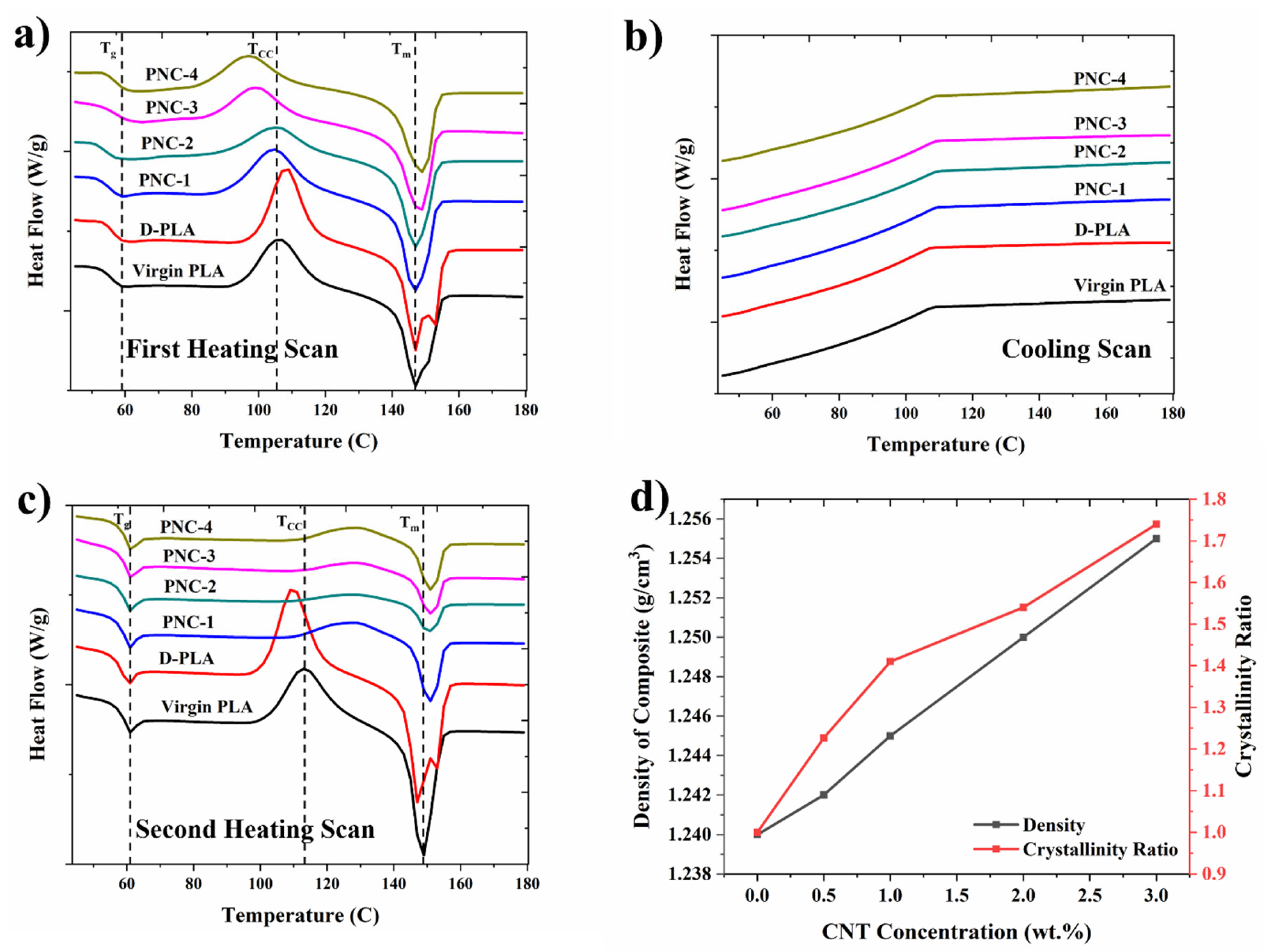

4.2. Thermal Analysis

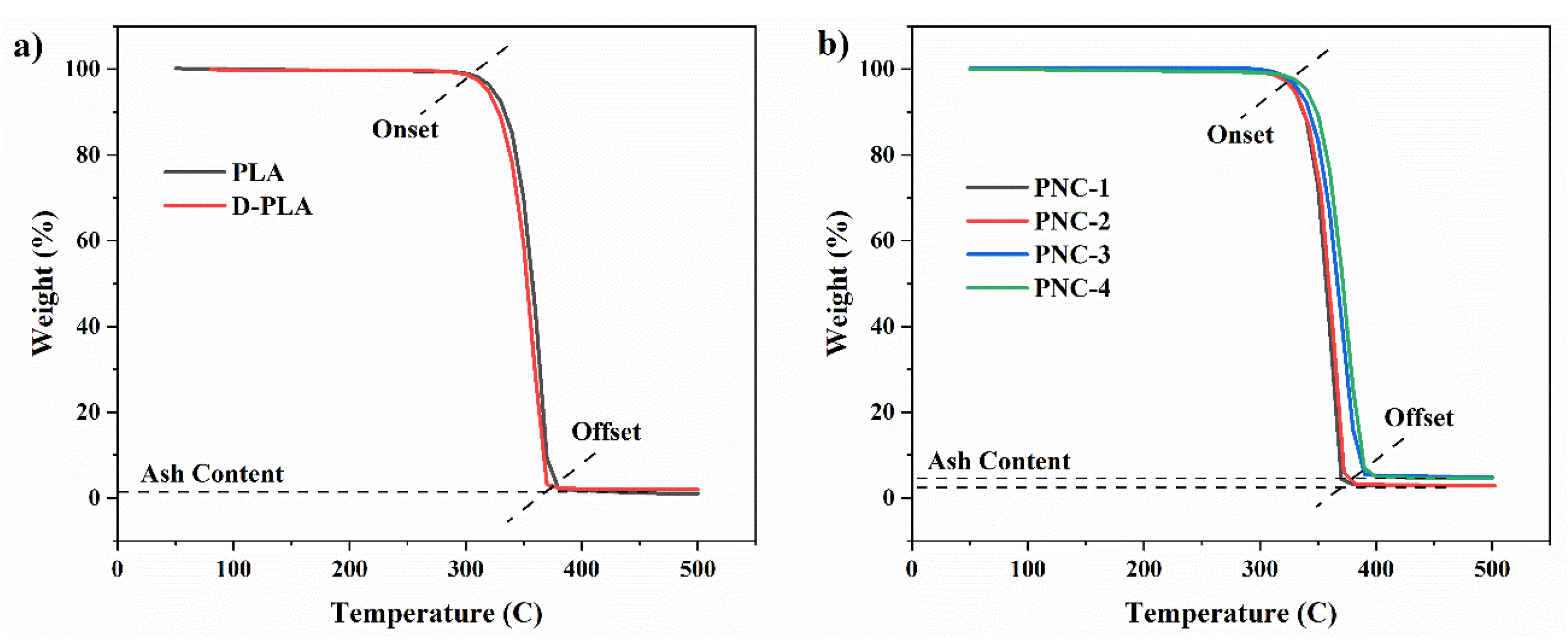

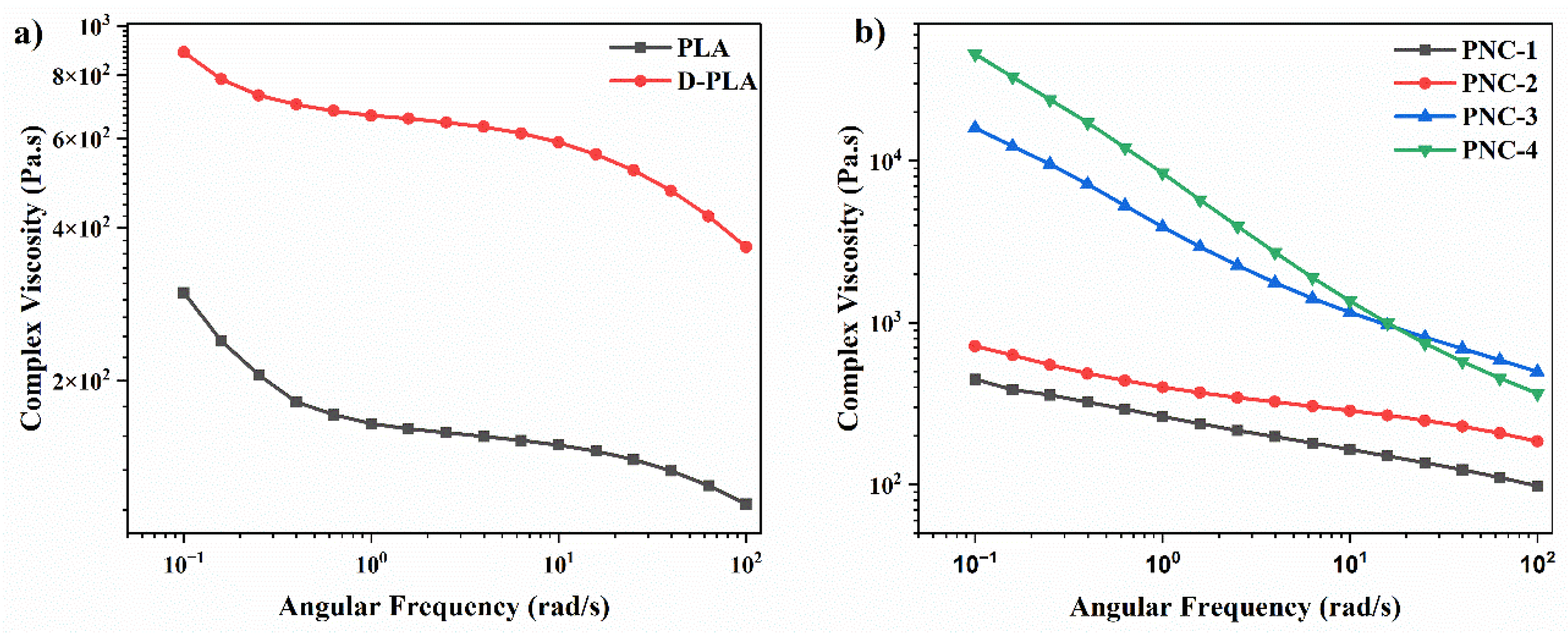

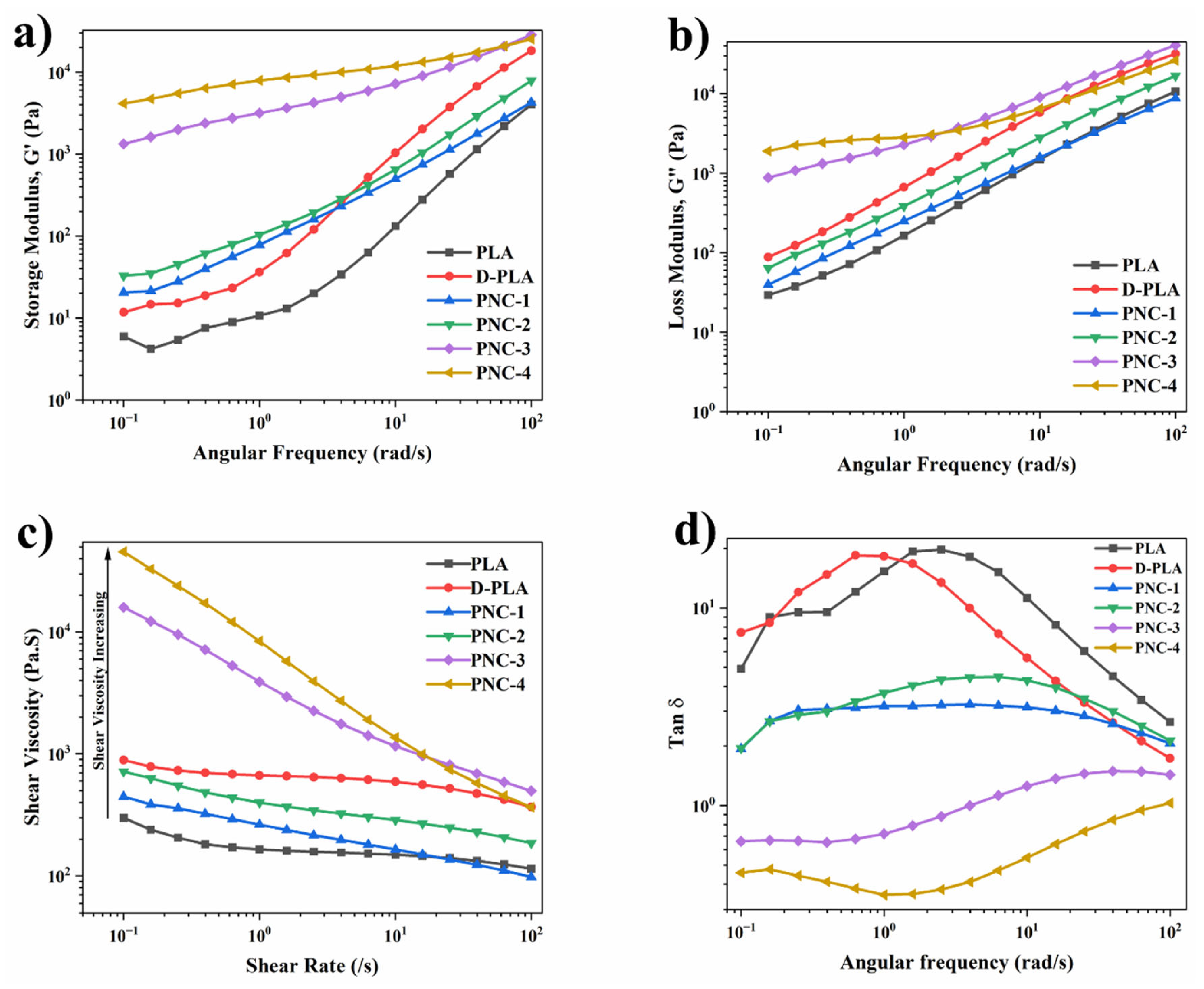

4.3. Rheology Characteristics of FDM 3D Printed PNCs

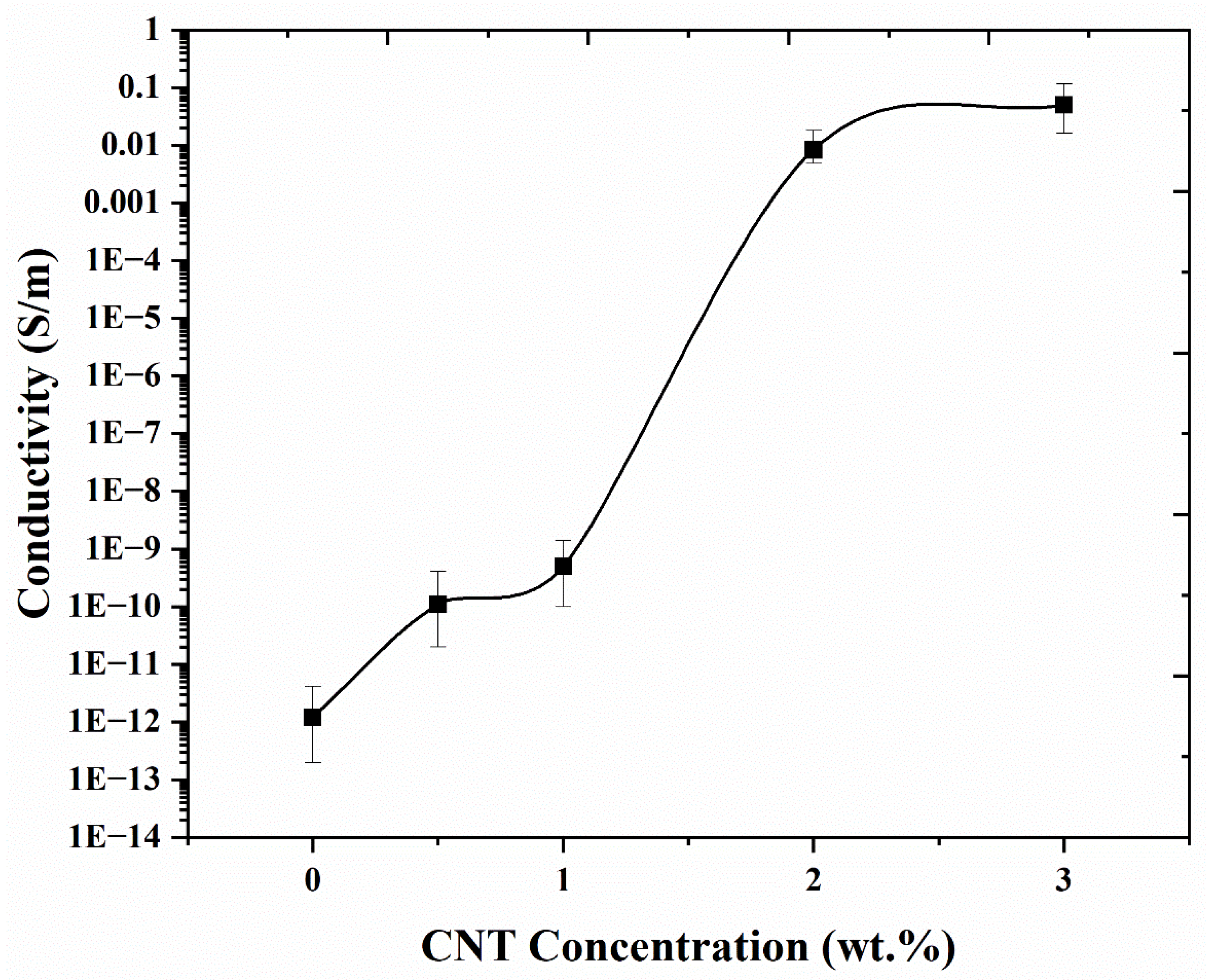

4.4. Electrical Conductivity of FDM 3D Printed PNCs

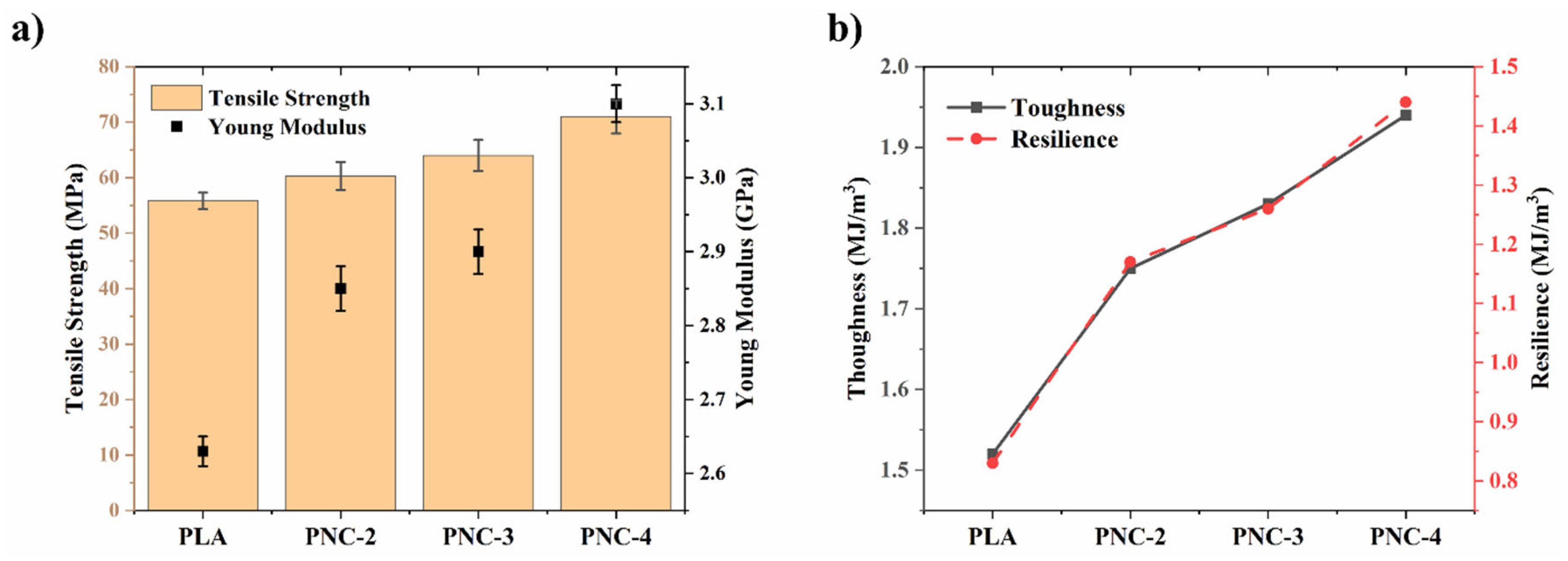

4.5. Mechanical Characteristics of FDM 3D Printed Specimens

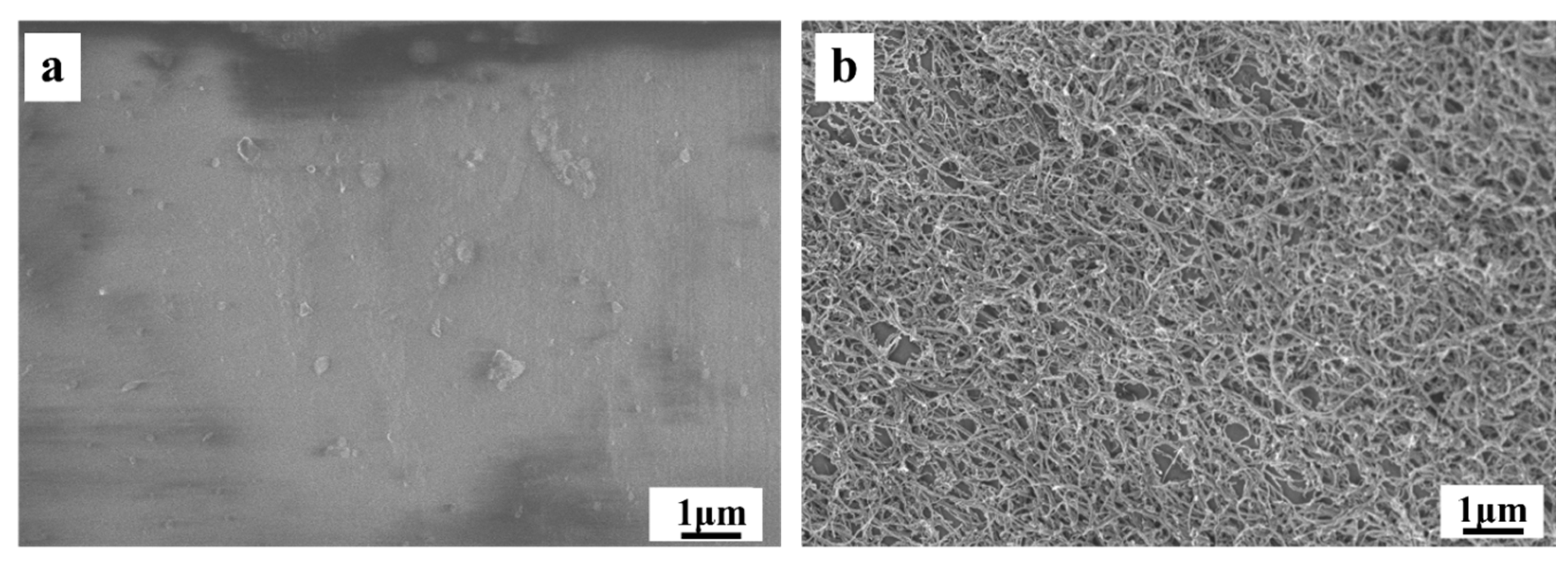

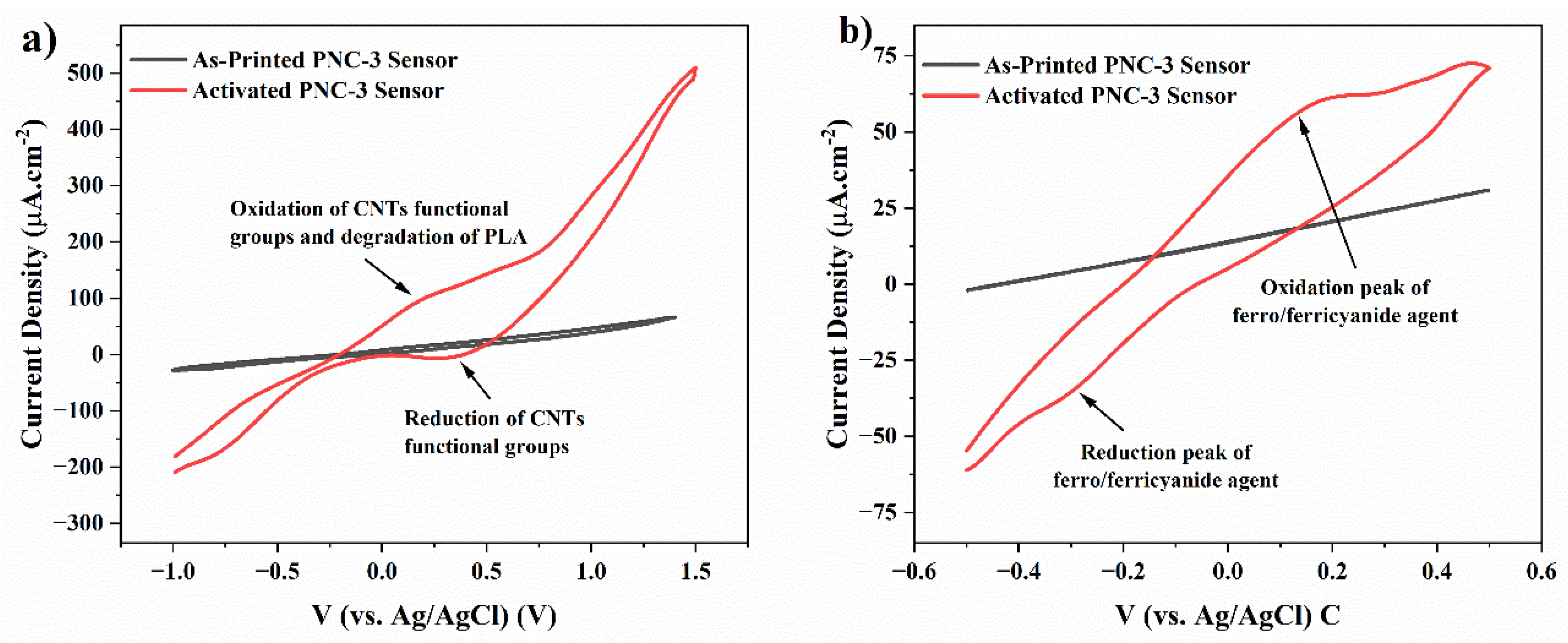

4.6. Electrochemical Performance and Morphology

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Erdem A, Yildiz E, Senturk H, Maral M (2023) Implementation of 3D printing technologies to electrochemical and optical biosensors developed for biomedical and pharmaceutical analysis. J Pharm Biomed Anal 230:115385. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpour-Haratbar A, Zare Y, Rhee KY (2022) Electrochemical biosensors based on polymer nanocomposites for detecting breast cancer: Recent progress and future prospects. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 309:102795. [CrossRef]

- Son MH, Park SW, Sagong HY, Jung YK (2022) Recent Advances in Electrochemical and Optical Biosensors for Cancer Biomarker Detection. BioChip J 2022 171 17:44–67. [CrossRef]

- Thakur PS, Sankar M (2022) Nanobiosensors for biomedical, environmental, and food monitoring applications. Mater Lett 311:131540. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Islam MN, He R, et al. (2023) Recent Advances in 3D Printed Sensors: Materials, Design, and Manufacturing. Adv Mater Technol 8:2200492. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi J, Fayazfar H (2021) Highly sensitive determination of doxorubicin hydrochloride antitumor agent via a carbon nanotube/gold nanoparticle based nanocomposite biosensor. Bioelectrochemistry 139:107741. [CrossRef]

- Han T, Kundu S, Nag A, Xu Y (2019) 3D Printed Sensors for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Sensors 2019, Vol 19, Page 1706 19:1706. [CrossRef]

- Karimi N, Fayazfar H (2023) Development of highly filled nickel-polymer feedstock from recycled and biodegradable resources for low-cost material extrusion additive manufacturing of metals. J Manuf Process 107:506–514. [CrossRef]

- Tan LJ, Zhu W, Zhou K (2020) Recent Progress on Polymer Materials for Additive Manufacturing. Adv Funct Mater 30:2003062. [CrossRef]

- Martins P, Pereira N, Lima AC, et al. (2023) Advances in Printing and Electronics: From Engagement to Commitment. Adv Funct Mater 33:2213744. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A, Faber H, Khosla A, Anthopoulos TD (2023) 3D printed electrochemical devices for bio-chemical sensing: A review. Mater Sci Eng R Reports 156:100754. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi J, Rizvi G, Fayazfar H (2024) Sustainable 3D printing of enhanced carbon nanotube-based polymeric nanocomposites: green solvent-based casting for eco-friendly electrochemical sensing applications. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 131:4825–4837. [CrossRef]

- Shinyama K (2018) Influence of Electron Beam Irradiation on Electrical Insulating Properties of PLA with Soft Resin Added. Polymers (Basel) 10:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Lalabadi M, Jafari SM (2021) Bio-nanocomposites of graphene with biopolymers; fabrication, properties, and applications. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 292:102416. [CrossRef]

- Shameem MM, Sasikanth SM, Annamalai R, Raman RG (2021) A brief review on polymer nanocomposites and its applications. Mater Today Proc 45:2536–2539. [CrossRef]

- Carroccio SC, Scarfato P, Bruno E, et al. (2022) Impact of nanoparticles on the environmental sustainability of polymer nanocomposites based on bioplastics or recycled plastics—A review of life-cycle assessment studies. J Clean Prod 335:130322. [CrossRef]

- Karimi F, Karimi-Maleh H, Rouhi J, et al. (2023) Revolutionizing cancer monitoring with carbon-based electrochemical biosensors. Environ Res 239:117368. [CrossRef]

- Ma PC, Siddiqui NA, Marom G, Kim JK (2010) Dispersion and functionalization of carbon nanotubes for polymer-based nanocomposites: A review. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 41:1345–1367. [CrossRef]

- Soni SK, Thomas B, Kar VR (2020) A Comprehensive Review on CNTs and CNT-Reinforced Composites: Syntheses, Characteristics and Applications. Mater Today Commun 25:101546. [CrossRef]

- Mi D, Zhao Z, Bai H (2023) Improved Yield and Electrical Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Carbon Nanotube Composites by Shear and Anneal. Materials (Basel) 16:. [CrossRef]

- Khan T, Irfan MS, Ali M, et al. (2021) Insights to low electrical percolation thresholds of carbon-based polypropylene nanocomposites. Carbon N Y 176:602–631. [CrossRef]

- Ong YT, Tan SH (2019) Carbon nanotube-based biodegradable polymeric nanocomposites: 3Rs (Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle) in the design. Handb Ecomater 4:2787–2802. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov E, Kotsilkova R, Xia H, et al. (2019) PLA/Graphene/MWCNT Composites with Improved Electrical and Thermal Properties Suitable for FDM 3D Printing Applications. Appl Sci 2019, Vol 9, Page 1209 9:1209. [CrossRef]

- Mora A, Verma P, Kumar S (2020) Electrical conductivity of CNT/polymer composites: 3D printing, measurements and modeling. Compos Part B Eng 183:107600. [CrossRef]

- Ke K, Wang Y, Liu XQ, et al. (2012) A comparison of melt and solution mixing on the dispersion of carbon nanotubes in a poly(vinylidene fluoride) matrix. Compos Part B Eng 43:1425–1432. [CrossRef]

- Spinelli G, Lamberti P, Tucci V, et al. (2018) Morphological, Rheological and Electromagnetic Properties of Nanocarbon/Poly(lactic) Acid for 3D Printing: Solution Blending vs. Melt Mixing. Mater 2018, Vol 11, Page 2256 11:2256. [CrossRef]

- Kim HG, Hajra S, Oh D, et al. (2021) Additive manufacturing of high-performance carbon-composites: An integrated multi-axis pressure and temperature monitoring sensor. Compos Part B Eng 222:109079. [CrossRef]

- Junpha J, Wisitsoraat A, Prathumwan R, et al. (2020) Electronic tongue and cyclic voltammetric sensors based on carbon nanotube/polylactic composites fabricated by fused deposition modelling 3D printing. Mater Sci Eng C 117:111319. [CrossRef]

- Torkelson TR, Oyen F, Rowe VK (1976) The toxicity of chloroform as determined by single and repeated exposure of laboratory animals. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 37:697–705. [CrossRef]

- Schlosser PM, Bale AS, Gibbons CF, et al. (2014) Human Health Effects of Dichloromethane: Key Findings and Scientific Issues. Environ Health Perspect 123:114–119. [CrossRef]

- Vergaelen M, Verbraeken B, Van Guyse JFR, et al. (2020) Ethyl acetate as solvent for the synthesis of poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline). Green Chem 22:1747–1753. [CrossRef]

- Han W, Rao D, Gao H, et al. (2022) Green-solvent-processable biodegradable poly(lactic acid) nanofibrous membranes with bead-on-string structure for effective air filtration: “Kill two birds with one stone.” Nano Energy 97:107237. [CrossRef]

- Jubinville D, Sharifi J, Mekonnen TH, Fayazfar H (2023) A Comparative Study of the Physico-Mechanical Properties of Material Extrusion 3D-Printed and Injection Molded Wood-Polymeric Biocomposites. J Polym Environ 31:3338–3350. [CrossRef]

- Dealy JM, Wissbrun KF (1999) Melt Rheology and Its Role in Plastics Processing. Melt Rheol Its Role Plast Process. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D638, Standard test method for tensile properties of plastics.

- Rocha DP, Rocha RG, Castro SVF, et al. (2022) Posttreatment of 3D-printed surfaces for electrochemical applications: A critical review on proposed protocols. Electrochem. Sci. Adv. 2:e2100136. [CrossRef]

- Park SG, Abdal-Hay A, Lim JK (2015) Biodegradable poly(lactic acid)/multiwalled carbon nanotube nanocomposite fabrication using casting and hot press techniques. Arch Metall Mater 60:1557–1559. [CrossRef]

- De Bortoli LS, de Farias R, Mezalira DZ, et al. (2022) Functionalized carbon nanotubes for 3D-printed PLA-nanocomposites: Effects on thermal and mechanical properties. Mater Today Commun 31:103402. [CrossRef]

- Zhang C, Lan Q, Zhai T, et al. (2018) Melt crystallization behavior and crystalline morphology of Polylactide/Poly(ε-caprolactone) blends compatibilized by lactide-caprolactone copolymer. Polymers (Basel) 10:. [CrossRef]

- Petrovics N, Kirchkeszner C, Patkó A, et al. (2023) Effect of crystallinity on the migration of plastic additives from polylactic acid-based food contact plastics. Food Packag Shelf Life 36:101054. [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos L, Klonos PA, Terzopoulou Z, et al. (2021) Comparative study of crystallization, semicrystalline morphology, and molecular mobility in nanocomposites based on polylactide and various inclusions at low filler loadings. Polymer (Guildf) 217:123457. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Yin D, Liu W, et al. (2020) Fabrication of biodegradable poly (lactic acid)/carbon nanotube nanocomposite foams: Significant improvement on rheological property and foamability. Int J Biol Macromol 163:1175–1186. [CrossRef]

- Ali F, Ishfaq N, Said A, et al. (2021) Fabrication, characterization, morphological and thermal investigations of functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes reinforced epoxy nanocomposites. Prog Org Coatings 150:105962. [CrossRef]

- Jubinville D, Sharifi J, Fayazfar H, Mekonnen TH (2023) Hemp hurd filled PLA-PBAT blend biocomposites compatible with additive manufacturing processes: Fabrication, rheology, and material property investigations. Polym Compos 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Xu Z, Niu Y, Yang L, et al. (2010) Morphology, rheology and crystallization behavior of polylactide composites prepared through addition of five-armed star polylactide grafted multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Polymer (Guildf) 51:730–737. [CrossRef]

- Lamberti P, Spinelli G, Kuzhir PP, et al. (2018) Evaluation of thermal and electrical conductivity of carbon-based PLA nanocomposites for 3D printing. AIP Conf Proc 1981:. [CrossRef]

- Vidakis N, Petousis M, Kourinou M, et al. (2021) Additive manufacturing of multifunctional polylactic acid (PLA)—multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) nanocomposites. Nanocomposites 7:184–199. [CrossRef]

| Code Chart | PLA (wt.%) | MWCNTs-COOH (wt.%) |

|---|---|---|

| PLA | 100 | 0 |

| D-PLA | 100 | 0 |

| PNC-1 | 99.5 | 0.5 |

| PNC-2 | 99 | 1 |

| PNC-3 | 98 | 2 |

| PNC-4 | 97 | 3 |

| Printing Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Nozzle diameter | 0.4 mm |

| Nozzle temperature | 200 ℃ |

| Bed temperature | 60 ℃ |

| Infill density | 100 % |

| Layer height | 0.2 mm |

| Raster angle | 45° |

| Print speed | 10 mm/s |

| Flow rate | 100 % |

| First Heating Cycle | Second Heating Cycle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg (℃) | TCC (℃) | Tm (℃) | %XCr | Tg (℃) | TCC (℃) | Tm (℃) | %XCr | |

| PLA | 59 | 106 | 147 | 6.96 | 61 | 113 | 149 | 4.1 |

| D-PLA | 59 | 108 | 147* | 3.49 | 61 | 109 | 147* | 3 |

| PNC-1 | 59 | 106 | 146 | 5.3 | 61 | 127 | 151 | 3.68 |

| PNC-2 | 59 | 105 | 147 | 14.95 | 61 | 128 | 151 | 4.23 |

| PNC-3 | 60 | 99 | 148 | 15.78 | 61 | 129 | 151 | 4.62 |

| PNC-4 | 60 | 97 | 149 | 16.45 | 61 | 130 | 151 | 5.22 |

| Zero Shear Viscosity (Pa.S) | R2 | |

|---|---|---|

| PLA | 3.03×105 | 0.93 |

| D-PLA | 9.39×102 | 0.96 |

| PNC-1 | 1.76×105 | 0.99 |

| PNC-2 | 2.81×105 | 0.99 |

| PNC-3 | 6.46×105 | 0.99 |

| PNC-4 | 1.6×105 | 0.99 |

| PLA | PNC-2 | PNC-3 | PNC-4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 55.8±1.4 | 60.5±2.35 | 63.9±2.8 | 71±3.2 |

| Tensile Modulus (GPa) | 2.63±0.1 | 2.84±0.05 | 2.9±0.1 | 3.1±0.07 |

| Elongation at Break (%) | 4.1±0.2 | 5.32±0.5 | 6.5±0.3 | 7.1±0.2 |

| Toughness (MJ/m3) | 1.52±0.01 | 1.75±0.03 | 1.83±0.01 | 1.94±0.02 |

| Resilience (MJ/m3) | 0.83±0.01 | 1.17±0.02 | 1.26±0.01 | 1.44±0.04 |

| Nanocomposite feedstock preparation method | CNTs wt.% and related Conductivity (S.m-1) | Percolation Threshold Onset | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Wt.% | Conductivity (S.m-1) | ||

| Solution Casting using Ethyl Acetate | 1×10-10 | 5×10-10 | 8.3×10-3 | 5×10-2 | 1 | 5×10-10 | Our Work |

| Melt Extrusion | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1×10-2 | 1.5 | 1×10-8 | [46] |

| Melt Extrusion | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7.8×10-4 | 1.5 | 1.4×10-8 | [23] |

| Melt Extrusion | 5×10-7 | 1.5×10-3 | 3×10-3 | 1 | 0.5 | 5×10-7 | [24] |

| Mechanical Mixing of PLA Powder with CNTs | 1×10-9 | 5×10-5 | N/A | N/A | 0.5 | 1×10-9 | [47] |

| Solution Casting using DCM | N/A | 1×10-4 | 1×10-1 | 5×10-1 | N/A | N/A | [27] |

| Solution Casting using Chloroform* | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).