1. Introduction

The success of restorations in terms of retention is dependent on the physical properties of luting cements, or dental cement. Solubility is one of the most critical factors in assessing the effectiveness and quality of luting cements in restorative dentistry [1]. Luting cements fill the space between tooth and restoration and protect them from harmful effects of occlusal force as well as and serve as a barrier against leakage. Dental luting cements at the margin of restoration are in constant contact with the oral flow and are subject to dissolution. Therefore, ideal dental luting cements will be determined by being resistant to disintegration and dissolution and by avoiding an environment susceptible to plaque and bacterial accumulation, secondary caries, and debonding of restoration [1]. In pediatric dentistry, stainless steel crowns (SSC) are frequently utilized to restore primary teeth or permanent teeth and require the use of dental luting cement. SSC has high clinical success records in terms of retention. However, one of the critical failures of the SSC restoration could have been caused by cementation associated problems including choice of materials and techniques [1]. Conventionally, a SSC is cemented using zinc phosphate, GI, RMGI, or resin-based cement. It has been studied that GI cement is superior to RMGI cement, followed by resin cement in terms of potential demineralization inhibition. However, RMGI demonstrated an equally successful clinical outcome as GI cements in terms of bond strength (P<0.124) [1,2]. This narrative review summarizes and compares solubilities of GI, RMGI and Resin cements in various pH values and storage periods to recommend use of luting agent with lowest solubility for routine use in dental practice.

2. Materials and Methods

Zinc Phosphate Cement

As shown in

Figure 1. Zinc Phosphate Cement (ZPC) was first used in 1878 as the “gold standard” for cementation of restorations with years of clinical success [6-10]. Strengths of zinc phosphate cement include high compressive strength of up to 104 mega pascals and fair working time of about 45 seconds [7]. This cement is used to lute metal and metal-ceramic full-coverage crowns and fixed partial dentures [6-8]. However, ZPC demonstrated disadvantages of high solubility in saliva, low tensile strength, and the potential for hypersensitivity due to low pH at the time of cementation [7].

Glass Ionomer Cement

Glass Ionomer (GI) Cement was formulated in 1969 by Wilson and Kent [11] and became the most frequently used definitive luting cement by the 1990s. Advantages of GI cement include ease of mixing, flow, ability to adhere to tooth and base metals, ability to release fluoride, transparency, high strength, and relatively low cost. GI cement also has a lower propensity to change size with a low thermal expansion coefficient. GI cement comes in the powder-liquid form and its physical properties can vary depending on powder-to-liquid mixing ratio, therefore, following the manufacturer’s recommendation is highly critical. There are encapsulated cements available containing consistent ratios that can eliminate this potential variability and difficulty of use and ensure accurate, recommended proportions. GIC has a low pH that can cause hypersensitivity after cementation [6-9].

Resin Modified Glass Ionomer

RMGI is a hybrid material introduced in the 1980s and is made by adding water-soluble polymerizable resin components to conventional GI cement. Advantages of RMGI include high fracture resistance, favorable physical and mechanical properties, strong bonding to enamel and dentin as well as higher resistance to wear. RMGI cements were made in attempts to overcome the weakness of conventional GI cements in relatively lower strength and high solubility. This material is easy to use, exhibits less film thickness, and has favorable esthetic properties. RMGI cement manifested superior physical and mechanical properties over conventional GI cement [10].

Resin Cement

Resin cement is the most recently developed dental cement. Unlike other luting cement derived from powder and liquid mixture to form a hydrogel, resin cement forms a polymer matrix to fill and seal the gap between the tooth and the restoration [11]. Earlier resin cement has experienced failures due to a high degree of polymerization shrinkage and inadequate enamel and dentin bonding. Modern resin cements are more predictable and adaptable to be used in many different cases [11]. The use of resin cement is ideal in many cases due to its versatility, low thermal expansion, high compressive and tensile strengths, and ideal aesthetic qualities. However, there are also downfalls such as difficulty with removing excess cement and technique sensitivity [11]. In delivering metal and metal-ceramic restorations, resin-luting cement, such as Rely X Unicem, is equally effective in performance as conventional ZPC [12]. Resin cement can either be adhesive or self-adhesive [12]. Adhesive cement requires acid-etching of the tooth with phosphoric acid prior to the application of adhesive components [13]. Self-adhesive cement does not require acid-etching and adhesive application [13]. At this time, there has not been sufficient long-term clinical data to support the routine use of resin cement over conventional luting cement yet [11].

3. Results

3.1. Retention from Luting Cement

An in-vitro study using 55 extracted primary first molars was conducted to compare the retentive ability of four luting cements in cementing SSC [14]. Luting cements included in the experiment were resin, GI, zinc phosphate, and polycarboxylate cement. Success of restoration depends on appropriate luting cement selection that considers the mechanical properties. By filling in the empty space between tooth and restoration, luting cements provide retention and adhesion. Polycarboxylate cement showed maximum retentive strength and zinc phosphates demonstrated the lowest retentive strength in this study. This study found that there was no significant difference between resin cement and GI cement concerning their ability to be retentive [14]. As retentive strength is found to be comparable between GI and resin cement and considering that SSCs are in constant exposure to the oral environment and dynamic oral fluids, it is strongly advised to examine how solubility will affect the success of SSC cementation.

Furthermore, retention of luting cement used to cement permanent crowns was examined in a review of crown pull-off tests. A total of 18 studies that performed pull-off tests on extracted teeth were reviewed. Cements compared were zinc phosphate, GI (Ketac-Cem), and resin cement (Panavia and RelyX Unicem). The studies used extracted molars and premolars and prepared them for either metal alloy crowns (16 studies) or ceramic crowns (2 studies). Resin based cement demonstrated higher failure stress compared to GI with average percentage difference of 32.2% (P=0.03) and GI had higher failure stress compared to zinc phosphate cement with average percentage difference of 25.1% (P=0.02). Resin cement demonstrated superior retention during the pull-off test, however, previous studies have declared that different properties of cement including shrinkage, expansion, water uptake, and water solubility can heavily affect cementation success [15].

3.2. Solubility of RMGI vs. Resin Cement

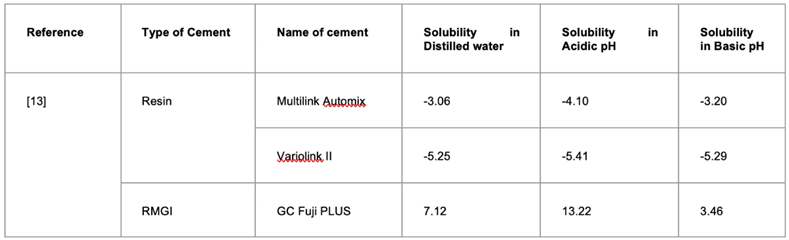

A study performed by Gavranović-Glamoč et al., compared RMGI (GC Fuji Plus) and two resin cements (Multilink Automix and Variolink II). Samples were prepared according to ISO standard 4049:2009 which defines specific requirements for dental polymer-based restorative materials [13]. Teflon molds are used to shape luting cement into disk shapes. RMGI specimens were prepared with a polyester film and metal film. The second metal plate is put on top to eliminate surplus material and metal plates are held together by clamps and immediately placed in a sealed environment kept at 37±1ºC for 60 minutes. All samples were then refined and polished with ultra-fine silicon carbide paper until a uniform diameter was met. For dual cure resins, metal plates were replaced by glass plates to polymerize specimens. After materials were prepared into disks, all samples were then stored in desiccators with silicate gel and stored in an incubator for 22 hours. After 22 hours, samples were all together placed in another desiccator that was kept at a stable temperature of 23±1ºC for two hours, then weighed on an analytical balance until constant mass was obtained.

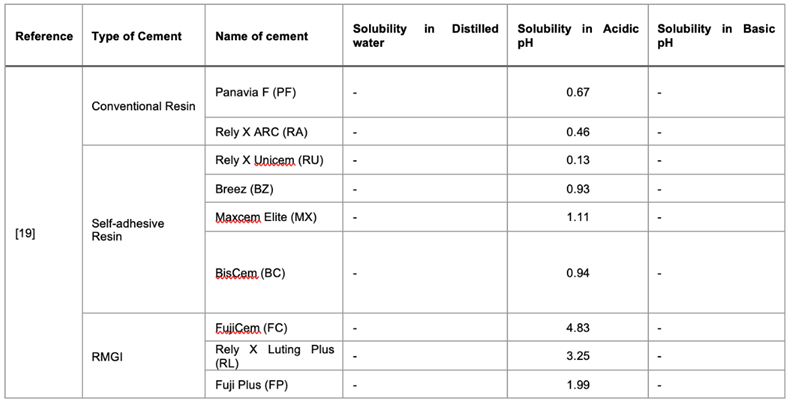

The solubility of the luting cement in question was compared with three different pH values. Solution 1 was distilled water, solution 2 represented a pH value of 7.4 to reflect slightly basic artificial saliva, and finally, solution 3 had a pH value of 3.0 to reflect an acidic environment. Samples were then submerged in solutions prepared for each testing condition and solubility was measured at five time periods of 24 hours, 48 hours, 72 hours, 96 hours, and 168 hours. Samples were taken out of the solution, rinsed out with water, air-dried for 15 seconds, and weighed sixty seconds after being taken out of the corresponding storage solution to record the measured mass. The formula used to calculate solubility (Wsl) was Wsl = (m1-m3) / V where m1 is the mass of specimens before submersion, m3 is the mass of samples after drying, and V represents the volume of specimens [13]. Results are summarized in

Table 1.

When the solubility of GC Fuji Plus (RMGI) was compared to resin cement: Multilink Automix and Variolink II in solution with pH 7.4 and pH 3.0, GC Fuji plus showed statistically significant higher solubility in comparison with Variolink II and Multilink Automix in all solutions, except in solution of pH 7.4 where no statistically significant difference in solubility was confirmed between Multilink and GC Fuji Plus. In the acidic (pH 3.0) solution, Multilink showed higher solubility compared to Variolink II with a p-value < 0.016 and GC Fuji Plus showed significantly higher values of solubility in pH 3.0 solution (P< 0.009) [13].

Table 1. Finding: RMGI cement exhibited statistically significant higher solubility compared to Resin cements in distilled water and acidic pH (P<0.009) and no significance in pH 7.4 solution between RMGI and Multilink cement (P=0.024).

3.3. Solubility of Resin vs. RMGI vs. GI

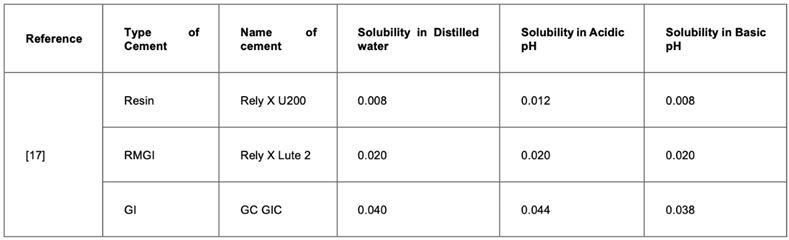

In another in vitro study done by Mehta et al. [17], a total of eight luting cements were compared. Interestingly, this study compared both permanent dental luting cement as well as temporary luting cement to suggest the use of certain cement in situations where temporary cement is needed [17]. Permanent cements that were compared are Rely X lute 2, Zinc phosphate, zinc polycarboxylate, Rely X U-200, and GI cement G.C (Fuji). Temporary cements compared were zinc oxide eugenol (ZOE), Oratemp NE, and Temposil. Each material was prepared to equal sizes (20 mm by 1.5 mm) using a similar method as the above studies, following the manufacturer’s recommendation when mixing. Samples were then submerged in solutions of varying pH values (3, 5, 7, or 9) and weighed to test for dissolution at 24 hours, 72 hours, 7 days, and 28 days. Results are shown in

Table 2. Comparison within the temporary cement groups demonstrated that Temposil had the lowest solubility after 28 days and ZOE showed the greatest solubility. Temposil at differing pH values showed that solubility was greatest after 28 days in pH 3 and least in distilled water. For Oratemp NE and ZOE, solubility was highest in the pH 3 solution and least in the pH 9 solution. In the permanent cement group, Rely X U-200 had the least amount of solubility at 28 days, followed by Rely X lute-2, RMGI, Zinc polycarboxylate, and zinc phosphate which demonstrated the highest solubility among the permanent cement materials. Interestingly, for GI cement, solubility was highest at pH 3.0 and lowest at pH 9, while for Rely X U-200, solubility was highest at pH 5 and lowest at pH 9. Zinc phosphate and polycarboxylate cements showed similar solubility results with the highest solubility at pH 3 and the lowest in distilled water [17]. These results were intriguing in that between the same type of materials, the highest and lowest solubility results were different at different pH levels.

Table 2. Finding: Rely X U-200 resin cement demonstrated least amount of solubility at the end of 28 days test period followed by Rely X Lute 2 (RMGI) and lastly, GC GIC (final weight – initial weight).

3.4. Solubility of Resin vs. GI

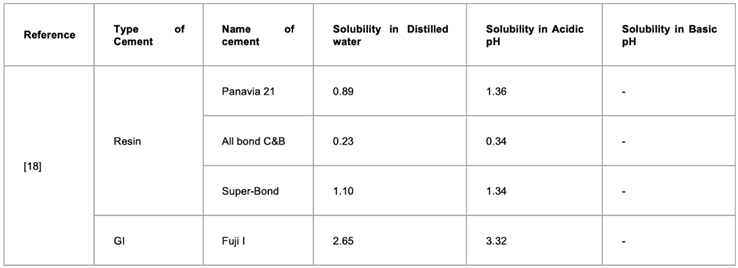

Yoshida et al., have stated that one of the most crucial properties of luting materials that must be considered is their ability to resist dissolution and disintegration. To represent conditions of the oral cavity as closely as possible in vitro, pH values 5.7 and lactic acid solution at pH 4.0 were tested for comparison. Materials tested were resin (Panavia 21, All bond C&B, Super-Bond) and GI cement Fuji I. Results are presented in

Table 3. It should be mentioned that Panavia and All bond both had filler components and the super-bond did not contain fillers. Results of the experiment reinforced that resin cement had the lowest solubility compared to GI cement and that all cement types showed markedly increased solubility in an acidic environment of pH 4.0 [18-20].

Table 3. Finding: All resin cements showed lower solubility compared to GI cement and all cement types showed highest solubility in acidic solution.

3.6. Oral Salivary pH Change After Consumption of Soft Drinks in Children

Sanchez and Preliasco have studied the salivary pH change of children after the consumption of soft drinks [20]. pH changes after consumption of different soft drinks including Coca-cola, Sprite, Ades N, and Chocolate milk were examined and results indicated that pH values showed a statistically significant drop. It was also demonstrated that a dropped pH value was maintained between 5.5 and 6.2 [20]. Another study done on forty-five 12-year-old children from public schools in Itatiba, Brazil measured salivary pH upon consumption of acidic beverages. The authors explained that upon contact with saliva, the acid in the beverage releases hydrogen ions and results in a decrease of salivary pH. Immediately after intake, pH reduced to 6.26 and slowly increased over 15 minutes. At 15 minutes after consumption of an acidic soft drink, salivary pH was 6.64 on average and the results were statistically significant [21]. These results demonstrate that salivary pH is significantly affected by the beverages we consume and this reduction in pH lasts for at least 15 minutes in children. It is important to consider these results as numerous studies have found that a large percentage of young children consume sugary soft drinks daily [22]. According to above mentioned studies, significantly higher cement solubility was observed in acidic conditions. Considering the salivary pH decrease upon consumption of soft drinks, association of pH decrease and increase of dental cement solubility should be further evaluated.

4. Discussion

From the studies and experiments reviewed in this article, consistent overall results were observed across the board. Resin cement had the highest resistance to dissolution and disintegration, followed by RMGI cement and GI cement. All samples were prepared similarly, in the shape of a disk between about 15 mm - 20 mm diameter by 1.5 mm thickness [13,17,18,19]. While studies were conducted using a varying range of pH values and sample immersion periods, the overall trend was similar in that all luting cements had increased solubility in more acidic conditions and with increased storage periods (

Table 4).

Significantly higher solubility reported of RMGI cement in an acidic solution compared to resin cement may be attributed to the hydrophilic nature of RMGI cement. RMGI cement showed significantly higher solubility than resin cement [13]. However, containing the resin matrix in its composition, RMGI cement can limit the diffusion of the solvent into the cement and therefore, exhibit less solubility compared to conventional GI cement [23].

Yoshida et al. showed a pH change of distilled water (original pH 5.7) and lactic acid solution after 30 days of sample suspension [18]. According to the data, distilled water and acidic solution where resin cements were suspended showed no change in pH over 30 days. However, distilled water that contained conventional luting cements showed an increase in pH to nearly 7.0 at the end of the 30 days. This result occurred due to intermediates being formed during the dissolution of luting cement material. More specifically, zinc and magnesium are released from zinc phosphate and polycarboxylate cement, and aluminum and silicon are released from GI cement. This explains the increase in pH of the two solutions that contained the conventional luting cement. On the contrary, resin cement demonstrated no change in pH due to only minimal release of methacrylate monomers into the solutions. This additionally goes to show that resin cements experience markedly less solubility in both distilled water and lactic acid solutions. When solubility data is collected and the relationship between solubility and immersion period is evaluated by regression analysis, a statistically significant positive correlation is shown. This linear relationship can help to estimate solubilities over an extended period. The authors predicted that the three conventional luting cements will disintegrate within two years. On the other hand, resin cements are expected to completely break down between 3 to 9 years for Super-bond and All bond, whereas Panavia 21 was estimated to take 35 years to dissolve by 5%. This result is interesting and leaves questions regarding the role of fillers and composition of resin cement and what component has affected the relationship of rate of dissolution to this extent [23].

5. Conclusions

Reiterating the fact that the success of restorations is dependent upon luting cements, these results apply not only to permanent teeth but also to primary teeth that are restored by stainless steel crowns and strip crowns. Considering the large percentage of children with sugary carbonated beverage intake that is shown to lower salivary pH for up to 15 minutes after consumption, the solubility of dental cementing materials in contact with such beverages should also be examined. When selecting luting cement to cement restorations, clinicians need to consider all aspects of luting cement including physical and mechanical properties, biocompatibility, water sorption, and solubility. The water solubility of dental cement has shown to have a critical impact on restoration success and therefore, future studies should focus on better replication of dynamic oral cavity environments to test dental cement materials in different solutions such as carbonated beverages and sports drinks that are frequently consumed by the public, in shorter intervals to determine the solubility of different dental luting cement.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization and reviewing articles, D.Y.K and K.C.; methodology, D.Y.K and K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y.K.; writing—review and editing, D.Y.K, N.A., N.L., and K.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kimberly Carr, Dr. Ping Zhang, and Dr. Janice Jackson (University of Alabama, Birmingham) for comments on the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Waly AS, Souror YR, Yousief SA, Alqahtani WMS, El-Anwar MI. (2020). Pediatric Stainless-Steel Crown Cementation Finite Element Study. Eur J Dent. 2021 Feb;15(1):77-83. Epub 2020 Oct 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yilmaz Y, Gurbuz T, Eyuboglu O, Belduz N. The repair of pre-veneered posterior stainless steel crowns. Pediatr Dent. 2008 Sep-Oct;30(5):429-35. PMID: 18942604.

- Maletin A, Knežević MJ, Koprivica DĐ, Veljović T, Puškar T, Milekić B, Ristić I. (2023). Dental Resin-Based Luting Materials—Review. Polymers. 15(20):4156.

- Lad, P.P.; Kamath, M.; Tarale, K.; Kusugal, P.B. (2014). Practical clinical considerations of luting cements: A review. J. Int. Oral Heal. 6, 116–120.

- Masaka, N.; Yoneda, S.; Masaka, K. (2021). An up to 43-year longitudinal study of fixed prosthetic restorations retained with 4-META/MMA-TBB resin cement or zinc phosphate cement. J. Prosthet. Dent. 129, 83–88. [CrossRef]

- Heboyan, A., Vardanyan, A., Karobari, M. I., Marya, A., Avagyan, T., Tebyaniyan, H., Mustafa, M., Rokaya, D., & Avetisyan, A. (2023). Dental Luting Cements: An Updated Comprehensive Review. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 28(4), 1619. [CrossRef]

- Leung, G. K., Wong, A. W., Chu, C. H., & Yu, O. Y. (2022). Update on Dental Luting Materials. Dentistry journal, 10(11), 208. [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.E. (2007). Dental cements for definitive luting: A review and practical clinical considerations. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 51, 643–658. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.D., & Kent, B.E. (2007). The glass-ionomer cement, a new translucent dental filling material. Journal of Applied Chemistry and Biotechnology, 21, 313-313.

- Hill, E. E., & Lott, J. (2011). A clinically focused discussion of luting materials. Australian dental journal, 56 Suppl 1, 67–76. [CrossRef]

- Bharali, K., Das, M., Jalan, S., Paul, R., & Deka, A. (2017). To Compare and Evaluate the Sorption and Solubility of Four Luting Cements after Immersion in Artificial Saliva of Different pH Values. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences, 9(Suppl 1), S103–S106. [CrossRef]

- Dhanpal P., Yiu C., King N., Tay F., Hiraishi N. (2009). Effect of temperature on water sorption and solubility of dental adhesive resins. J. Dent. 2009;37:122–132. [CrossRef]

- Gavranović-Glamoč, A., Ajanović, M., Kazazić, L., Strujić-Porović, S., Zukić, S., Jakupović, S., Kamber-Ćesir, A., & Berhamović, L. (2020). Evaluation of Solubility of Luting Cements in Different Solutions. Acta medica academica, 49(1), 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Parisay I, Khazaei Y. (2018). Evaluation of retentive strength of four luting cements with stainless steel crowns in primary molars: An in vitro study. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2018 May-Jun;15(3):201-207. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yanikoğlu, N., & Yeşil Duymuş, Z. (2007). Evaluation of the solubility of dental cements in artificial saliva of different pH values. Dental materials journal, 26(1), 62–67. [CrossRef]

- Ch'ikwa Kijae Hakhoe chi. (1967). Revised American National Standards Institute/American Dental Association Specification No. 8 for Zinc Phosphate Cement. The Journal of the Korea Research Society for Dental Materials, 2(3), 64–67.

- Mehta, S., Kalra, T., Kumar, M., Bansal, A., Avasthi, A., & Malik, S. S. (2020). To evaluate the solubility of different permanent and temporary dental luting cements in artificial saliva of different ph values at different time intervals—an in vitro study. Dental Journal of Advance Studies, 8(03), 092–101. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K., Tanagawa, M., & Atsuta, M. (1998). In-vitro solubility of three types of resin and conventional luting cements. Journal of oral rehabilitation, 25(4), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Labban, N., AlSheikh, R., Lund, M., Matis, B. A., Moore, B. K., Cochran, M. A., & Platt, J. A. (2021). Evaluation of the Water Sorption and Solubility Behavior of Different Polymeric Luting Materials. Polymers, 13(17), 2851. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, G. A., & Fernandez De Preliasco, M. V. (2003). Salivary pH changes during soft drinks consumption in children. International journal of paediatric dentistry, 13(4), 251–257. [CrossRef]

- Almenara, O., Rebouças, A., Cavalli, A., Durlacher, M., Oliveira, A., Flório, F., & Zanin, L. (2016). Influence of soft drink intake on the salivary ph of schoolchildren. Pesquisa Brasileira Em Odontopediatria e Clínica Integrada, 16(1), 249–255. [CrossRef]

- Mensink GBM, Schienkiewitz A, Rabenberg M, Borrmann A, Richter A, Haftenberger M. (2018). Consumption of sugary soft drinks among children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the cross-sectional KiGGS Wave 2 study and trends. J Health Monit. 2018 Mar 15;3(1):31-37. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yoshida, K., Tanagawa, M., & Atsuta, M. (1998). In-vitro solubility of three types of resin and conventional luting cements. Journal of oral rehabilitation, 25(4), 285–291. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).