1. Introduction

Mortality and morbidity from pneumonia-induced sepsis remains high despite advances in critical care, understanding of the pathophysiology, and in treatment strategy [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Early recognition and risk stratification are necessary to improve the outcomes in patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis [

5,

6]. However, definitive and accurate prognostic indicators for pneumonia-induced sepsis have not been found.

Increased percentages of immature granulocytes in systemic circulation are regarded as indicators of increased myeloid cell production and are associated with infection of systemic inflammation[

7,

8]. However, the measurement is difficult to obtain in clinical practice because manual measurement is neither accurate nor reproducible[

9]. Nahm

et al. suggested that the delta neutrophil index (DNI), which represents the differences in leukocyte subfractions assessed by an automated blood cell analyzer, may be useful [

10]. The DNI reflects the fraction of circulating immature granulocytes based on the differences between the leukocyte differentials measured in the myeloperoxidase (MPO) reactions and the nuclear lobularity of white blood cells. Recent studies showed a strong correlation of DNI with the manual immature granulocyte count, in addition to a strong correlation with disseminated intravascular coagulation scores, positive blood culture rates, and mortality in patients with suspected sepsis [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

However, little is known about the clinical usefulness of DNI in assessing the prognosis of patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis in the ICU. In this study, we evaluated the clinical utility of DNI in ICU patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis as an indicator of 28 day-mortality.

2. Materials AND Method

2.1. Patients

This retrospective study included patients admitted to the medical ICU of Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital between July 2022 and March 2024. Pneumonia patients with sepsis or septic shock were included. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 18 years or stayed in the ICU for less than 24 hours. Permission was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital to review.

2.2. Data Collection

Epidemiological and clinical data available at the time of ICU admission were collected from patients’ medical records. Data included age, sex, comorbid conditions, severity of illness score, laboratory values, and therapeutic interventions performed during the stay in the ICU, such as vasopressor use, renal replacement therapy, or tracheostomy. Further, 28-day mortality and cause of death were evaluated.

Blood samples for the analyses of DNI and other laboratory parameters were obtained within the first 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours after ICU admission. Blood samples were analyzed at the time of ICU admission, and an automatic cell analyzer (ADIVA 2120 Hematology System, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Forchheim, Germany) was used to calculate DNI. This hematologic analyzer is flow cytometry-based and analyzes WBCs by MPO and lobularity/nuclear density channels. After red blood cell lysis, the tungsten-halogen-based optical system of the MPO channel measured cell size and stain intensity in order to count and differentiate granulocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes based on size and MPO content. Next, the laser diode-based optical system of the lobularity/nuclear density channel countered and classified the cells according to size, lobularity, and nuclear density. The resulting data were inserted in the following formula to determine DNI:

DNI = leukocyte subfraction assayed in the MPO channel by cytochemical reaction minus the leukocyte subfraction counted in the nuclear lobularity channel by reflected light beam [

10].

2.3. Definitions

We defined sepsis as "life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection," and septic shock as "a subset of sepsis characterized by particularly profound circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities, clinically confirmed by the requirement of vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure of 65 mm Hg or greater in the absence of hypovolemia and a serum lactate level greater than 2 mmol/L (>18 mg/dL)[

3,

17]. Patient severity can be identified as Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II Scoring System[

18]. We defined DNI 1 as DNI at 24 hours of ICU admission, DNI 2 as DNI at 48 hours of ICU admission, and DNI 3 as DNI at 72 hours of ICU admission.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, whereas the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Prognostic factors for 28-day mortality were evaluated. Variables with p < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were considered in the multivariable analyses to include potential variables with clinical significance. Multivariate logistic regression analysis results were reported as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) were constructed, and the area under the curve (AUC) was evaluated. We also evaluated cut off value of prognostic factor. Our study made an effort to predict the optimum cut point based on time-to-event through using the technique of Contal and O’Quigley. All tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using the PASW statics software version 22 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL)

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

During the study period, 227 patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis. The main demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age was 74 ± 13.7 years. Sixty six patients were male. The main underlying diseases were Diabetes Mellitus (124, 54.6 %), Hypertension (79, 34.8%), and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (36, 15.9%). One hundred sixteen (51.1%) patients were diagnosed with septic shock. One hundred twenty nine patients received mechanical ventilation and twenty five patients received renal replacement therapy. The median duration of mechanical ventilation was 4.5 (2–80) days. The median duration of ICU stay was 7 (1–90) days. Forty-six (51.7%) patients had microbiologically documented pneumonia. Comorbidities were present in 124 SPs (81.5%), with 45 patients having more than two comorbidities. Causative pathogens were identified in 87 SPs (57.2%), with Acinetobacter baumannii being the most common pathogen in patients discharged from hospitals (8.6%), while Streptococcus pneumoniae was the predominant pathogen in community-acquired pneumonia cases (5.2%).

3.2. Factors Associated with 28-Day Mortality

The 28-day mortality was 20.3% (46/226). The clinical and laboratory values of survivors and non-survivors were compared in

Table 2. In univariate analysis, age (

p=0.05), DNI 1 (

p =0.01), DNI 2 (

p=0.00), DNI 3 (

p=0.00), lactic acid (

p =0.00) were significantly associated with 28-day mortality (

Table 2). In multivariate analysis, lactate (adj. OR. 0.86, 95% CI: 0.78-0.95,

p =0.002), and DNI 3 (adj. OR. 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89-0.99,

p = 0.048) were the risk factors for 28-day mortality (

Table 3). In the higher DNI 3 group (≥ 2.6), 67.4% of the patients died within 28 days, whereas in the lower DNI 3 group (< 2.6 ), 32.6 % of patients died during the first 28 days (

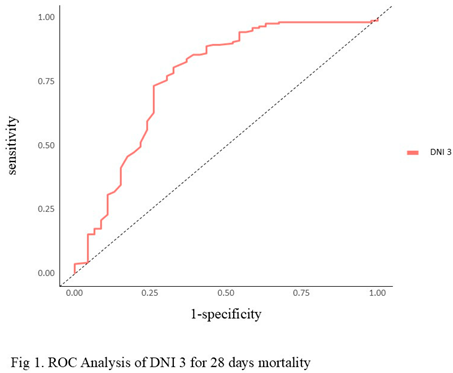

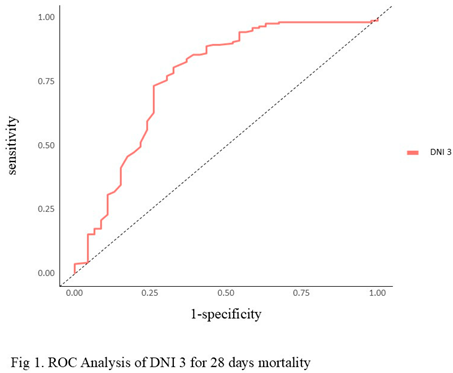

p = 0.00). Using a cutoff value of 2.6%, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) of the DNI 3 in sepsis were found to be 69%, 73.9%, 77.9%, and 64.1%, respectively (Figure 1). DNI 3 were more specific predicter for 28days mortality. The area under the curve of DNI 3 was 0.781 (95% CI 0.694-0.868), whereas DNI 1 (0.647, 95 % CI 0.558-0.736), DNI 2 (0.721, 95% CI 0.63-0.81), Lactic acid (0.655, 95% CI 0.553-0.756) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Univariable analysis in Survivor vs Nonsurvivor in 28 days mortality.

Table 2.

Univariable analysis in Survivor vs Nonsurvivor in 28 days mortality.

| Variables |

Survivors (N=181) |

Non survivors (N=46) |

p-value |

| Age |

73.1 ± 13.8 |

77.6 ± 13.1 |

0.05 |

| Sex (Male, %) |

115 (63.5) |

35 (76.1) |

0.15 |

| Septic shock |

98 (54.1) |

28 (60.9) |

0.09 |

| Severity scores |

|

|

|

| APACHE |

21.7 ± 5.9 |

23.3 ± 6.1 |

0.10 |

| Treatment in ICU |

|

|

|

| MV |

97 (53.6) |

32 (69.6) |

0.07 |

| CRRT |

19 (10.5) |

22 (47.8) |

0.82 |

| ECMO |

2 (1.1) |

2 (4.3) |

0.57 |

| ILA |

3 (1.6) |

2 (4.3) |

0.64 |

| Tracheostomy |

69 (38.1) |

18 (39.1) |

0.98 |

| Laboratory findings |

|

|

|

| WBC(103/ul) |

12998.0 ± 7834.8 |

14132.0 ± 8001.2 |

0.39 |

| Neutrophil (%) |

80.5 ± 14.5 |

73.6 ± 22.0 |

0.05 |

| DNI 1(%) |

5.8 ± 12.4 |

11.4 ± 13.8 |

0.01 |

| DNI 2(%) |

3.8 ± 9.2 |

14.5 ± 17.1 |

0.00 |

| DNI 3(%) |

2.3 ± 8.6 |

14.9 ± 19.0 |

0.00 |

| Hb (g/dl) |

11.8 ± 3.2 |

11.5 ± 2.5 |

0.48 |

| Platelet(103/ul) |

248.3 ± 138.0 |

229.9 ± 116.8 |

0.36 |

| Na (mEq/L) |

136.9 ± 9.9 |

138.4 ± 10.4 |

0.39 |

| K(mEq/L) |

4.6 ± 0.9 |

4.1 ± 0.8 |

0.06 |

| BUN (mg/dl) |

36.8 ± 25.0 |

26.3 ± 19.3 |

0.07 |

| Cr(mg/dl) |

1.5 ± 1.3 |

1.4 ± 2.4 |

0.53 |

| AST(IU/L) |

140.5 ± 460.2 |

48.8 ± 52.8 |

0.18 |

| ALT(IU/L) |

68.0 ± 226.5 |

34.8 ± 77.3 |

0.33 |

| BNP (pg/ml) |

128.5 ± 106.5 |

124.7 ± 109.4 |

0.83 |

| CRP(mg/dl) |

6.0 ± 14.6 |

5.0 ± 17.5 |

0.69 |

| Procalcitonin(ng/ml) |

446.8 ± 546.4 |

352.3 ± 569.0 |

0.32 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) |

5.5 ± 5.6 |

2.8 ± 2.9 |

0.00 |

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of predictive factors for 28-day mortality.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of predictive factors for 28-day mortality.

| Variables |

Adj Odds ratio ( 95% CI) |

p-value |

| Age |

0.97 (0.95, 1) |

0.052 |

| Sex |

2.07 (0.86, 5.03) |

0.106 |

| DNI 1 |

1.04 (0.98, 1.1) |

0.17 |

| DNI 2 |

0.98 (0.9, 1.06) |

0.596 |

| DNI 3 |

0.94 (0.89, 0.99) |

0.043 |

| Lactic acid |

0.86 (0.78, 0.95) |

0.002 |

3.3. The Subgroup Analysis of the Delta Neutrophil Index (DNI) as Predictor of 28 Days Mortality

Patients were classified into subgroups according to age (≥70 or < 70 ). Interestingly, age ≥70 group did not show statistically significant difference of DNI 1 values between survivor and non survivor group, in univariate analysis. Age < 70 group showed statistically significant difference DNI 1values between survivor and non survivor group. DNI2 and DNI 3 showed statistically significant difference DNI 1values between survivor and non survivor group in all age (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study showed that DNI, which reflects the number of circulating granulocyte precursors in the blood, at 72 hours after ICU admission, can be a useful prognostic factor for 28-day mortality in patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis. In our study, DNI was higher in the non-survivor group than in the survivor group throughout the treatment period, although statistical significance was confirmed only at 72 hours from ICU admission. These findings agree with some previous reports. Kim

et al. reported that in patients with gram negative bacteremia, the risk of early mortality was greatest when DNI remained higher than the initial value until three days after the onset of bacteremia[

19]. Lee

et al. reported that a cut-off DNI of 2% at 72 hours after the onset of neonatal sepsis was associated with the 7-day mortality rate [

20]. Lim

et al. reported that the DNI on postoperative day 3 was the best predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis caused by peritonitis[

20].

Recent studies suggest that sepsis impairs innate immunity of patients[

21,

22]. Neutrophil paralysis in sepsis results in the failure of neutrophils to migrate to the site of infection and causes inappropriate neutrophil sequestration in remote organs[

23]. We proposed that neutrophil paralysis in sepsis may cause a rapid and early production of immature neutrophils to compensate for the deficiency of active neutrophil. Since higher DNI levels correlate with increased numbers of immature neutrophils, patients with higher DNI levels may have more dysregulated immune functions. Those patients who maintain a high DNI until 72 hours after start of treatment may have sustained dysregulation of immunity. Thus, patients with higher DNI levels may have worse prognosis in the pathogenesis of pneumonia sepsis. Therefore, DNI at 72 hours could be an alarming marker to check the patient’s status again and to consider other treatment strategies.

However, cut-off values of DNI for predicting mortality varied. In our study, the optimal cut-off DNI for predicting mortality was 3%. The higher DNI group (≥3), measured 72 hours after ICU admission, showed significantly higher 28-day mortality (P = 0.00) than the lower DNI group (<3). Similarly, Lee at al reported that a cut-off DNI of 2% at 72 hours after onset of neonatal sepsis was associated with the 7-day mortality rate[

20]. However, a previous study by Kim

et al. reported that the optimal cut-off DNI for predicting mortality was 7.6% in patients with gram negative bacteremia[

19]. Furthermore, Park

et al. reported that a DNI >6.5% was a good predictor of severe sepsis and septic shock within 24 hours of admission to an ICU [

12]. Therefore, further evaluation of the adequate cut-off value of DNI is needed.

We demonstrated that the DNI correlated with the severity of pneumonia-induced sepsis in the ICU. DNI values were higher in the septic shock group compared to the sepsis group. Previously, Park et al. showed DNI may be used as a marker of disease severity in critically ill patients with sepsis[

12]. Given that the process of granular leukocyte differentiation starts from immature granulocyte formation, the change in DNI may have preceded the change in absolute numbers of WBCs or neutrophils, thus contributing to predicting the development of septic shock. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to identify patients who are at risk of developing septic shock before the signs of organ dysfunction or circulatory failure appear.

Interestingly, in our study, elderly patients (≥70), a DNI 1 did not show statistical significance between the survival group and the non survival group. It could be several explanations related to the immune system and its response in aging individuals: First theory is immune depression in old age group. Immunosenescence refers to the gradual deterioration of the immune system associated with aging. In older individuals, both the innate and adaptive immune responses tend to weaken, which means that their bodies may not mount the same level of response to infection as younger people do[

24]. A lower DNI in older adults could be due to a decreased production of neutrophils, particularly immature granulocytes, during infections or inflammatory processes. The bone marrow in older individuals may not respond as robustly to signals that normally stimulate neutrophil production[

25]. Second theory is older individuals often experience chronic low-grade inflammation, sometimes referred to as "inflammaging." This persistent, low-level inflammation might lead to a baseline activation of the immune system, which can mask or reduce the body's capacity to produce a surge of neutrophils in response to acute infections[

26]. This state of chronic immune activation could potentially lead to lower increases in immature neutrophils, resulting in a lower DNI when acute infection occurs. Third theory is older adults often have multiple comorbid conditions (e.g., diabetes, chronic kidney disease) that can affect their immune response and ability to produce neutrophils. Certain medications commonly used in older populations, such as immunosuppressants or corticosteroids, can also blunt the body's inflammatory response and neutrophil production. These factors can contribute to a lower DNI in older patients, as their overall immune response may be suppressed or altered by both their underlying conditions and treatments.

Although our study suggests the prognostic value of DNI in pneumonia-induced sepsis patients, several limitations exist. First, this study was conducted retrospectively in a single center; therefore, the possibility of selection bias remains. Secondly, the elevation of immature granulocytes is not specific for infection and may be observed in various other conditions such as myeloproliferative disorder, chronic inflammatory disorders, tissue damage, acute hemorrhage, and neoplasia. Thirdly, because we evaluated only short-term mortality, it is still questionable whether DNI 3 can predict long-term outcome in patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis. Therefore, more studies with large number of patients are required to validate the clinical usefulness of DNI as a severity and prediction marker of pneumonia –induced sepsis.

5. Conclusion

These data shed new light on the role of the DNI in pneumonia-induced sepsis. DNI measured 72 hours after ICU admission may serve as a useful prognostic marker for 28-day mortality in patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis in the ICU. Especially, patients with higher DNI 3 (≥ 2.6) showed higher 28-day mortality than patients with lower DNI 3 (< 2.6) group. There was not a study on the clinical usefulness of DNI in assessing the prognosis of patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis in the ICU. Early detection and treatment initiation is essential for improving the treatment outcome in pneumonia-induced sepsis. Therefore, the identification of reliable biomarkers for diagnosis and guidance of treatment in sepsis patients is required. Our data show the usefulness of DNI at 72 hours as a prognostic marker in patients with pneumonia-induced sepsis in the ICU. Based on these results, we suggest that increased DNI value should alert clinicians to apply more aggressive therapy.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: S-Y P. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: S-Y M Drafting of the manuscript: S-Y M, Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Y- B P, Y-S K, C-W H, S-H P, J-W L, S-Y P, Statistical analysis: S-Y M , S-Y P, Administrative, technical, or material support: none. Supervision: S-Y M, Y-B P, Y-S K, C-W H, S-H P, J-W L, S-Y P , All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board of each institution approved the study protocol. Informed consent was obtained before data collection. The study was therefore performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. This is a retrospective study conducted from a de-identified database, and informed consent of participation is waived by the Institutional Review Board of Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital, Republic of Korea (IRB No. 2022-03-015-006)

Informed Consent Statement

The need for obtaining informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

References

- Restrepo M.I.; Mortensen E.M.; Velez J.A.; Frei C.; Anzueto A. A comparative study of community-acquired pneumonia patients admitted to the ward and the ICU. Chest. 2008,133,610-7. [CrossRef]

- Yu H.; Rubin J.; Dunning S.; Li S.; Sato R. Clinical and economic burden of community-acquired pneumonia in the Medicare fee-for-service population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012, 60, 2137-43.

- Watkins R.R.; Lemonovich TL. Diagnosis and management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2011, 83,1299-306.

- Aliberti S.; Amir A.; Peyrani P.; Mirsaeidi M.; Allen M.; Moffett BK. Incidence, etiology, timing, and risk factors for clinical failure in hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2008,134, 955-62. [CrossRef]

- Huttunen R.; Aittoniemi J. New concepts in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of bacteremia and sepsis. J Infect. 2011, 63, 407-19. [CrossRef]

- Chiwon Ahn W.K.; Tae Ho Lim.; Youngsuk Cho.; Kyu-Sun Choi.; Bo-Hyoung Jang. The delta neutrophil index (DNI) as a prognostic marker for mortality in adults with sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SCIENTIFIC REPORTS. 2018,26. [CrossRef]

- Mare TAea. The diagnostic and prognostic significance of monitoring blood levels of immature neutrophils in patients with systemic inflammation. Crit. Care. 2015, Feb 25,19(1), 57.

- Cavallazzi R.; Bennin, C.-L.; Hirani, A.; Gilbert, C.; & Marik, P. E. Review of A Large Clinical Series: Is the Band Count Useful in the Diagnosis of Infection?. J. Intensive Care Med. 2010,25,353–7. [CrossRef]

- PJ C. Clinical utility of the band count. Clin Lab Med. 2002, Mar, 101-36.

- Nahm C.H.; Choi J.W.; Lee J. Delta neutrophil index in automated immature granulocyte counts for assessing disease severity of patients with sepsis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2008, 38, 241-6.

- Seok Y.; Choi J.R.; Kim J.; Kim YK.; Lee J.; Song J. Delta neutrophil index: a promising diagnostic and prognostic marker for sepsis. Shock. 2012, 37, 242-6.

- Park BH.; Kang YA.; Park MS.; Jung WJ.; Lee SH.; Lee SK. Delta neutrophil index as an early marker of disease severity in critically ill patients with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011, 11, 299.

- Kim H.; Kim Y.; Kim KH.; Yeo CD.; Kim JW.; Lee HK. Use of delta neutrophil index for differentiating low-grade community-acquired pneumonia from upper respiratory infection. Ann Lab Med. 2015, 35, 647-50.

- Goag EKL.; J. W. Roh.; Y. H. Leem.; A. Y. Kim.; S. Y. Song.; Chung, K. S. A Simplified Mortality Score Using Delta Neutrophil Index and the Thrombotic Microangiopathy Score for Prognostication in Critically Ill Patients. Shock. 2018,4 9 ,39-43.

- Kim H.; Kong T.; Chung S.P.; Hong J.H.; Lee JW.; Joo Y. Usefulness of the Delta Neutrophil Index as a Promising Prognostic Marker of Acute Cholangitis in Emergency Departments. Shock. 2017,47,303-12.

- Hwang Y.J.; Chung S.P.; Park Y.S.; Chung H.S.; Lee H.S.; Park J.W. Newly designed delta neutrophil index-to-serum albumin ratio prognosis of early mortality in severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med. 2015,33,1577-82.

- Goncalves-Pereira J.; Conceicao C.; Povoa P. Community-acquired pneumonia: identification and evaluation of nonresponders. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2013,1,5-17. [CrossRef]

- Rhodes A.; Evans LE.; Alhazzani W.; Levy MM.; Antonelli M.; Ferrer R. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med. 2017,43,304-77.

- Kim H.W.; Jin S.J.; Kim S.B.; Ku N.S.; Jeong S.J. Delta neutrophil index as a prognostic marker of early mortality in gram negative bacteremia. Infection & chemotherapy. 2014,46,94-102.

- Lee SM E.H.; Namgung R.; Park M.S.; Park K.I.; Lee C. Usefulness of the delta neutrophil index for assessing neonatal sepsis. Acta paediatrica. 2013,102,e13-6.

- Hotchkiss R.S.; Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. The lancet infectious disease. 2013,13,260-8. [CrossRef]

- Willem Joost Wiersinga J.L.; Duncan R Cranendonk, and Tom van der Poll. Host innate immune responses to sepsis. Virulence. 2014, Jan, 36-44. [CrossRef]

- Alves-Filho J.C.; Spiller F.; Cunha FQ. Neutrophil paralysis in sepsis. Shock. 2010, 34, Suppl 1,15-21. [CrossRef]

- Kelci Straka M-LT.; Summer Millwood.; James Swanson.; and, Kuhlman K.R. Aging as a Context for the Role of Inflammation in Depressive Symptoms. frontier in psychiatry, 2021,11,1-13. [CrossRef]

- Kristof Van Avondt.; Jan-Kolja Strecker.; Claudia Tulotta.; Jens Minnerup.; Christian Schulz.; Oliver Soehnlei. Neutrophils in aging and aging-related pathologies. Immunological Reviews. 2023,314,357–375. [CrossRef]

- Claudio Franceschi.; Paolo Garagnani.; Paolo Parini.; Cristina Giuliani.; Aurelia Santoro. Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2018,14,576-90. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients with pneumonia sepsis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients with pneumonia sepsis.

| Variables |

Values (n=227) |

| Age, mean (SD) |

74 ± 13.7 |

| Sex (Male) (N, %) |

150 (66.1%) |

| Septic shock (N, %) |

116 (51.1%) |

| Cormobidities(N, %) |

|

| DM |

124(54.6 %) |

| HTN |

79 (34.8%) |

| Heart Disease |

32 (14.1%) |

| Stroke |

14 (6.2%) |

| COPD |

36(15.9%) |

| IPF* |

12(4.8%) |

| Dementia |

24(10.6%) |

| Chronic Liver Disease |

27 (11.9%) |

| Solid cancer |

32 (14.1%) |

| Severity on ICU admission |

|

| APACHE II (SD) |

22.0 ± 5.9 |

| Treatment in ICU(N, %) |

|

| Mechanical ventilation |

129 (56.8%) |

| Tracheostomy |

87 (38.3%) |

| CRRT |

25 (11.0 %) |

| ECMO |

5 (2.2%) |

| ILA |

4(1.7%) |

| Laboratory findings (SD) |

Values |

| WBC(103/ul) |

13227.8 ± 7864.3 |

| Hb (g/dl) |

11.8 ± 3.1 |

| Platelet (103/ul) |

244.6 ± 133.9 |

| Neutrophil(%) |

79.1 ± 16.5 |

| DNI 1 (%) |

6.9 ± 12.9 |

| DNI 2 (%) |

5.9 ± 12.0 |

| DNI 3 (%) |

4.9 ± 12.5 |

| Na (mEq/L) |

137.2 ± 10.0 |

| K(mEq/L) |

4.2 ± 0.8 |

| BUN (mg/dl) |

28.4 ± 21.0 |

| Cr(mg/dl) |

1.4 ± 2.2 |

| AST(IU/L) |

67.4 ± 213.9 |

| ALT( IU/L) |

41.5 ± 123.1 |

| BNP (pg/ml) |

371.7 ± 564.5 |

| CRP(mg/dl) |

125.4 ± 108.6 |

| Procalcitonin(ng/ml) |

5.2 ± 16.9 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) |

3.4 ± 3.8 |

Table 4.

Age -subgroup analysis of DNI for 28 days mortality.

Table 4.

Age -subgroup analysis of DNI for 28 days mortality.

| |

Coeff.(95%CI) |

P value |

| DNI 1 |

|

|

| ≥70 |

-4.23 (-9.2,0.73) |

0.097 |

| <70 |

-11.67 (-19.6,-3.74) |

0.005 |

| DNI 2 |

|

|

| ≥70 |

-8.93 (-13.43,-4.43) |

< 0.001 |

| <70 |

-19.38 (-25.83,-12.94) |

<0.001 |

| DNI 3 |

|

|

| ≥70 |

-10.47 (-14.74,-6.2) |

< 0.001 |

| <70 |

-23.76 (-31.67,-15.86) |

< 0.001 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).