Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection [

1]. Septic shock is a critical condition characterized by persistent hypotension and tissue hypoperfusion due to underlying circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities, despite adequate fluid resuscitation, with symptoms varying depending on the affected system [

2]. Pneumonia is one of the leading causes of sepsis. Studies have shown that sepsis related to pneumonia is associated with higher mortality rates compared to sepsis caused by other infections [

3].

Procalcitonin (PCT) is used as a biomarker in various inflammatory conditions such as sepsis, severe burns, acute pancreatitis, and postoperative infections. C-reactive protein (CRP), produced in response to specific pro-inflammatory cytokines, is another crucial marker of infection. It is widely used to assess the prognosis of patients with conditions like acute pancreatitis, pulmonary infections, malignant tumors, and gout arthritis, reflecting the severity of the disease [

4].

In cases of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), which is a component of sepsis, there is often an increase in blood leukocyte counts [

5]. Recent sepsis studies utilizing transcriptomic analysis have provided evidence of significant changes in the leukocyte transcriptomes of septic patients. The leukocytes of intensive care unit (ICU) patients show a highly altered transcriptome, with 70-80% of all RNA transcripts being significantly different [

6]. Particularly in critically ill patients with community-acquired pneumonia, transcriptomic analysis of circulating leukocytes has identified an immunosuppressive state associated with a higher mortality rate in the sepsis response [

7]. Such studies support the understanding that sepsis can lead to profound and persistent immunosuppression.

PCT, CRP, and leukocyte count are among the most commonly used biomarkers in the diagnosis of sepsis and septic shock [

8]. While there is limited data on the prognostic role of these biomarkers, some studies have emphasized that changes in PCT and CRP levels can be indicative of the outcome in sepsis [

9]. However, there is no clear consensus in the literature regarding the superiority of one biomarker over the others. The potential of CRP, PCT, and leukocyte count changes, either individually or in combination, to predict prognosis in patients with sepsis and septic shock remains a subject of interest. We believe that a dynamic approach to evaluating these biological markers may provide more insight into the outcomes of patients with sepsis. This study aims to assess the impact of changes in CRP, PCT, and leukocyte counts on the prognosis of patients admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of pneumosepsis and pneumonia-related septic shock, and to explore whether any of these markers have a superior predictive value in forecasting prognosis.

Materials and Methods

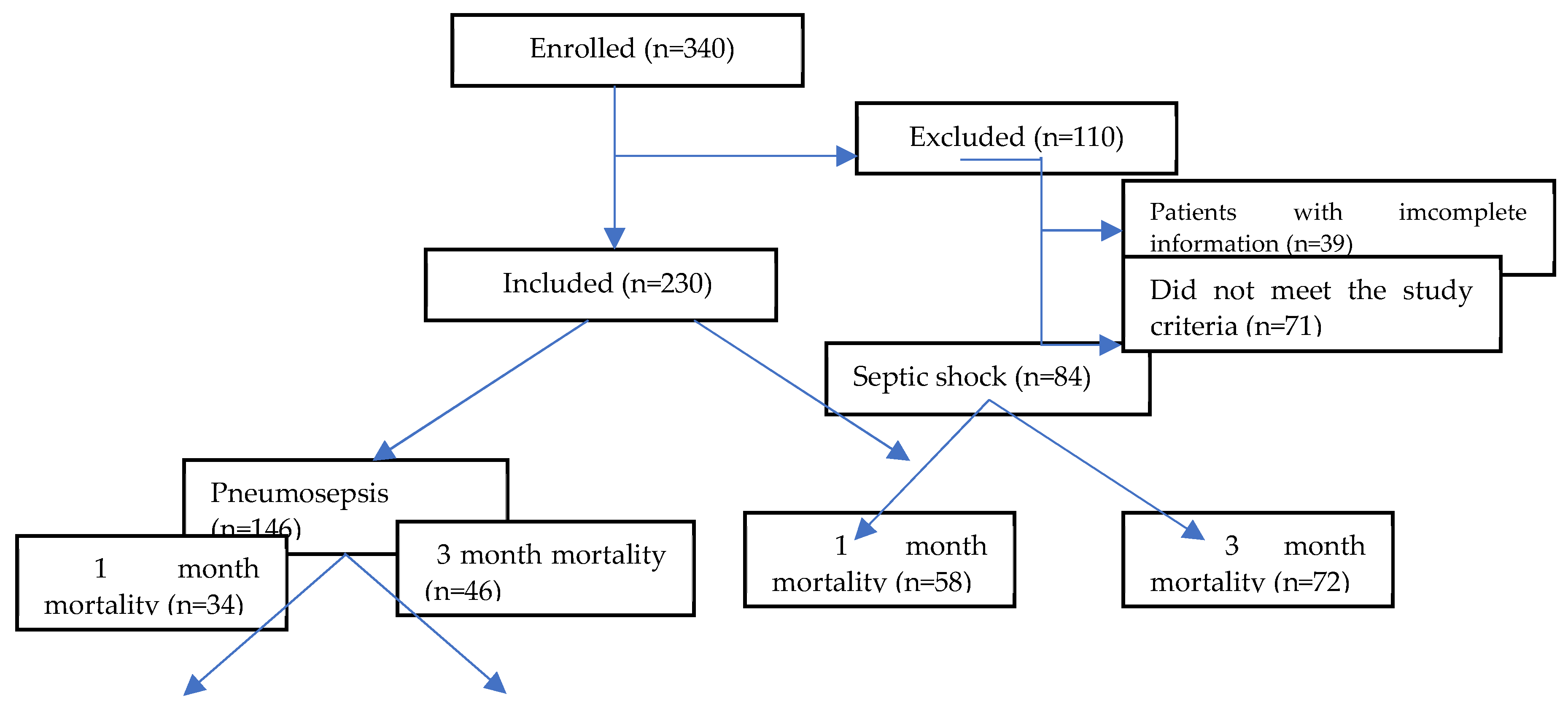

This study included 230 patients admitted to the adult, tertiary ICU at the University of Health Sciences Ankara Atatürk Sanatorium Training and Research Hospital with a diagnosis of pneumosepsis and pneumonia-related septic shock between April 1, 2022, and December 31, 2023. After obtaining approval from the institution’s Scientific Studies Ethics Committee, with approval number 2024-BÇEK/57 dated April 24, 2024, the patients’ hospital information management system records and files were retrospectively reviewed.

According to the Turkish Thoracic Society’s Consensus Report on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in Adults [

10], patients diagnosed with pneumonia who developed sepsis and septic shock related to pneumonia and were admitted to the ICU were included in the study. The inclusion criteria required patients to be over 18 years of age, monitored in the ICU for more than 24 hours, and to have received standard sepsis treatment according to the sepsis guidelines. The diagnosis and treatment of sepsis and septic shock followed the 2021 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines [

1].

Patients who were excluded from the study included those under 18 years of age, those who stayed in the ICU for less than 24 hours, those with extrapulmonary infections, immunocompromised patients (such as those with hematological malignancies, HIV, neutropenia <1000 cells/mL, or those who received chemotherapy or radiotherapy within the previous 45 days), patients with rheumatologic diseases, those with non-infectious causes of high inflammatory states such as pancreatitis, trauma, or major surgery, and patients with incomplete serum biomarker data (

Figure 1).

The study recorded various patient data, including age, gender, Body Mass Index (BMI), comorbidities, whether the patients were in sepsis or septic shock at the time of ICU admission, 1-month and 90-day mortality rates, length of ICU stay, discharge status to either a ward or an external facility, need for dialysis post-sepsis, need for invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation during ICU stay and the duration of such support, whether patients admitted with sepsis or septic shock required inotropic agent support during their ICU stay, and whether they received monotherapy or combination therapy with antibiotics at the time of ICU admission.

The severity of the illness was assessed using the CURB-65 score [confusion; blood urea nitrogen (BUN) > 20 mg/dL or urea > 42.8 mg/dL; respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min; systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg or diastolic ≤ 60 mmHg; and age ≥ 65 years], evaluated prior to ICU admission. Additionally, the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) score, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, and Charlson Comorbidity Index score (CCIS) were evaluated within the first 24 hours after ICU admission.

The levels of CRP, PCT, and leukocytes were recorded on the day of ICU admission and subsequently on days 3, 7, and 10 of ICU follow-up. Other laboratory parameters recorded at the time of admission included hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), creatinine, urea, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin, and albumin levels.

The CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels measured on days 1, 3, 7, and 10 of ICU follow-up were compared with other parameters in terms of significance. To determine whether the combined elevation of CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels or their individual elevations were more significant for mortality, the reference ranges of our hospital were used as a baseline. According to our hospital’s reference ranges, a CRP level >5 mg/L was considered elevated CRP, a PCT level >0.25 ng/mL was considered elevated PCT, leukocytosis was defined as a leukocyte count >12x10^3/µL, and leukopenia was defined as a leukocyte count <4x10^3/µL.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed by using SPSS for Windows, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Whether the distribution of continuous variables was normal or not was determined by the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. Levene test was used for the evaluation of homogeneity of variances.

Unless specified otherwise, continuous data were described as median (IQR (Q3:75. Persentile – Q1;25. Persentile) for skewed distributions. Categorical data were described as a number of cases (%). Statistical analysis differences in not normally distributed variables between two independent groups were compared by Mann Whitney U test. Statistical analysis differences in not normally distributed variables between three independent groups were compared by Kruskal wallis test. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test or fisher’s exact test. İt was evaluated degrees of relation between variables with spearman correlation analysis.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the association between mortality the risk factors findings.

First of all it was used one variable univariate logistic regression with risk factors that is thought to be related with mortality risk factors that has p-value < 0.25 univariate variable logistic regression was included to model on multivariable logistic regression. Enter model used in multivariable logistic regression. Whether every independent variables were significant on model was analyzed with Wald statistic on multivariable logistic regression. Whether every independent variables were significant on model was analyzed with t statistic on multivariable lineer regression.

It was accepted p-value <0.05 as significant level on all statistical analysis.

Results

Between April 1, 2022, and December 31, 2023, the data of 340 patients with pneumosepsis/septic shock were reviewed, and 230 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Among these patients, 131 (57%) were male, with a median age of 73 years (range 18-95, IQR: 20) and a median BMI of 24.9 kg/m² (range 13.8-52, IQR: 6). The median scores for the scoring systems calculated on the day of ICU admission were as follows: CCIS:6, CURB-65:3, APACHE-II: 24, and SOFA score:7. Of the patients, 146 (63.5%) were admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of pneumosepsis, while 84 (36.5%) were admitted with pneumonia-related septic shock.

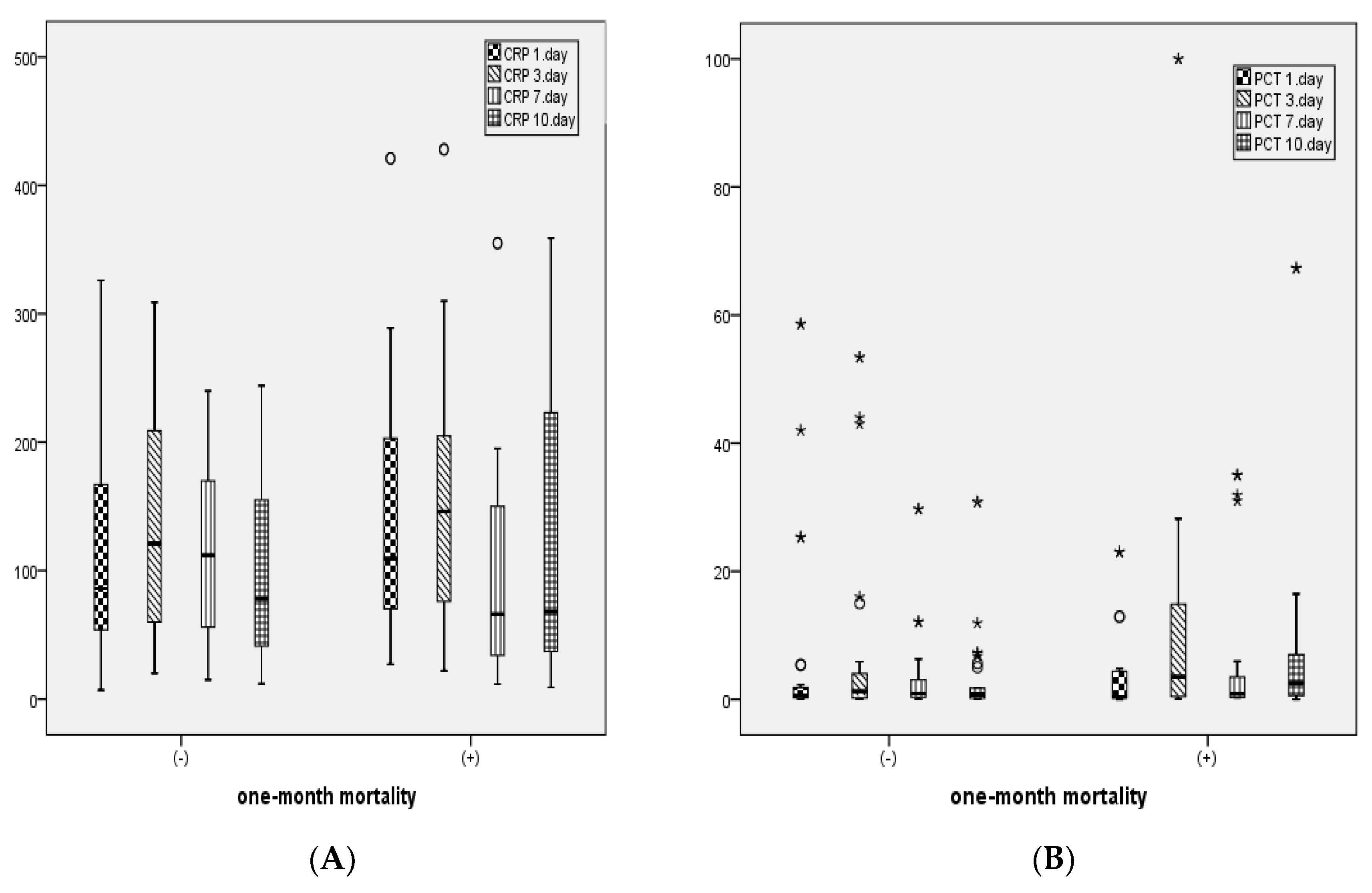

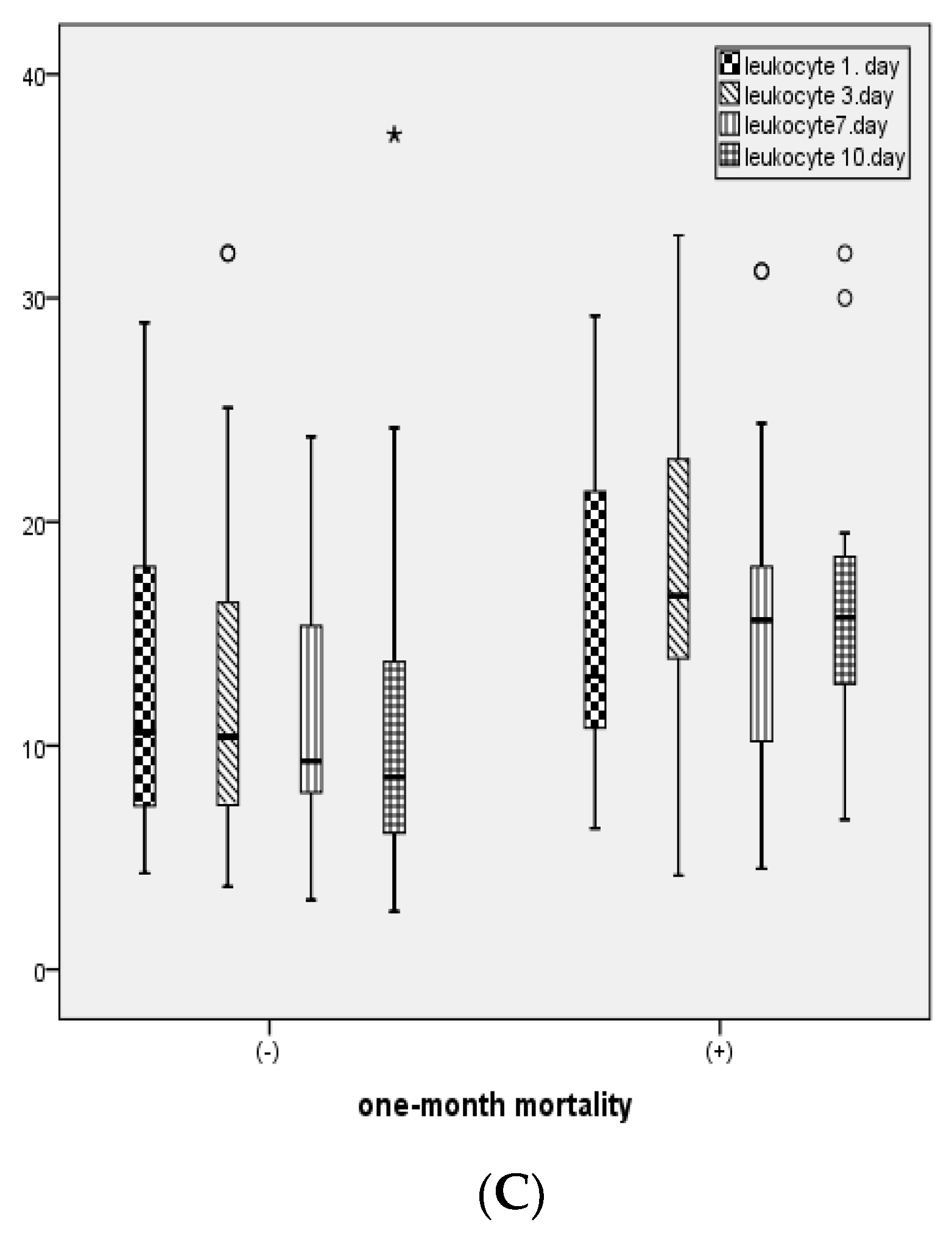

The median CRP values measured during ICU follow-up were as follows: Day 1: 109.5 mg/L (range 7-478, IQR: 127), Day 3: 117 mg/L (range 3-428, IQR: 120), Day 7: 78 mg/L (range 3-355, IQR: 111), Day 10: 74 mg/L (range 9-359, IQR: 120). The median PCT values during ICU follow-up were: Day 1: 0.88 ng/mL (range 0.01-89, IQR: 3.73), Day 3: 1 ng/mL (range 0.01-100, IQR: 4.75), Day 7: 0.71 ng/mL (range 0.01-35, IQR: 2.36), Day 10: 1.07 ng/mL (range 0.01-67.3, IQR: 3.65). The median leukocyte counts during ICU follow-up were: Day 1: 11.55 x10³/µL (range 1-57, IQR: 10.80), Day 3: 10.80 x10³/µL (range 1.7-60.4, IQR: 8.86), Day 7: 10.0 x10³/µL (range 2.5-31.2, IQR: 7.6), Day 10: 11.2 x10³/µL (range 2.6-37.3, IQR: 9.40). Among the 230 patients, 92 (40%) had positive 1-month mortality, and 118 (51.3%) had positive 3-month mortality.

In patients with 1-month mortality, the proportion of male patients, CCIS, CURB-65, APACHE II, and SOFA scores, duration of mechanical ventilation (MV), incidence of septic shock, and the need for inotropic support were found to be statistically significantly higher compared to those without mortality (p<0.05). Additionally, BMI and discharge rates were statistically significantly lower in patients with 1-month mortality compared to those who survived (p<0.05) (

Table 1).

In patients with 3-month mortality, the proportion of male patients, CCIS, CURB-65, APACHE II, SOFA scores, MV duration, incidence of septic shock, and the need for inotropic support were also found to be statistically significantly higher compared to those without mortality (p<0.05). Similarly, BMI and discharge rates were statistically significantly lower in patients with 3-month mortality compared to those who survived (p<0.05) (

Table 1).

In patients with 1-month mortality, CRP levels on days 1 and 3, PCT levels on days 3 and 10, leukocyte counts on days 3 and 10, ALT, and total bilirubin levels were statistically significantly higher, while albumin levels were statistically significantly lower compared to those without mortality (

Table 2).

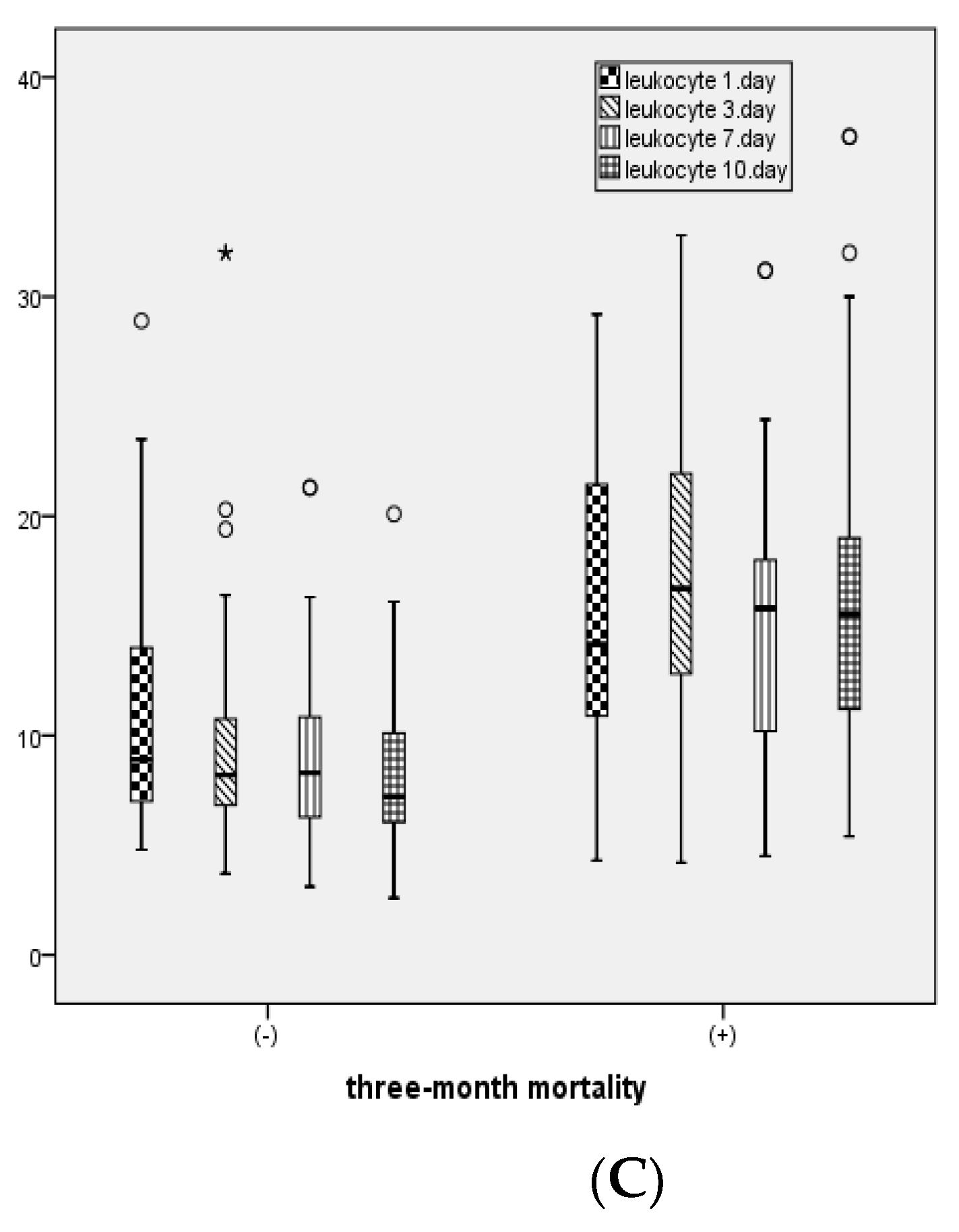

For patients with 3-month mortality, CRP levels on days 1, 3, 7, and 10, PCT levels on days 1, 3, 7, and 10, leukocyte counts on days 1, 3, 7, and 10, as well as AST, ALT, and total bilirubin levels were statistically significantly higher, while albumin levels were statistically significantly lower compared to those without mortality (

Table 2).

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels measured on days 1, 3, 7, and 10 between patients with and without 1-month mortality.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels measured on days 1, 3, 7, and 10 between patients with and without 3-month mortality.

Among the 92 patients with 1-month mortality, 9 (9.8%) had an increase in only one of the CRP, PCT, or leukocyte levels on day 1, 49 (53.3%) had increases in two of these values, and 34 (37.0%) had increases in all three values. No significant relationship was found between the simultaneous increase in CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels on day 1 and 1-month mortality among patients with and without mortality (p=0.09). For the 118 patients with 3-month mortality, 9 (7.6%) had an increase in only one of the CRP, PCT, or leukocyte levels on day 1, 60 (50.8%) had increases in two of these values, and 49 (41.5%) had increases in all three values. A significant relationship was found between the simultaneous increase in CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels on day 1 and 3-month mortality among patients with and without mortality (p<0.05). The concurrent increase in any two or all three of the CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels on day 1 was higher in patients with 3-month mortality compared to those without mortality (p=0.004).

Univariate logistic regression analysis was applied to identify factors predicting 1-month mortality. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered as mortality predictors. It was found that increased age, decreased BMI, male gender, higher CCIS, CURB-65, APACHE-II, and SOFA scores, shorter ICU stay, and increased leukocyte count on day 1 were associated with an increased risk of mortality (p<0.05). Variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, using the Enter method. A model explaining 1-month mortality was established based on the multivariate logistic regression analysis. According to this analysis, lower BMI, male gender, higher CCIS, CURB-65, and APACHE-II scores, and shorter ICU stay were identified as factors that increased the risk of 1-month mortality (p<0.05) (

Table 3).

Similarly, univariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify factors predicting 3-month mortality. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.05 were considered predictors or indicators of mortality. It was found that increased age, decreased BMI, male gender, increased leukocyte count on day 1, and higher CCIS, CURB-65, APACHE-II, and SOFA scores were associated with an increased risk of 3-month mortality (p<0.05). Variables with a p-value of less than 0.25 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, using the Enter method. A model explaining 3-month mortality was established based on the multivariate logistic regression analysis. According to this analysis, increased age, lower BMI, male gender, and higher CCIS, CURB-65, and APACHE-II scores were identified as factors that increased the risk of 3-month mortality (p<0.05) (

Table 4).

Discussion

In this study examining 230 patients admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of pneumosepsis or pneumonia-related septic shock, the primary outcome identified male gender, advanced age, low BMI, and high scores on CCIS, CURB-65, and APACHE-II as significant predictors of mortality. The secondary outcome of the study highlighted that increases in CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels, particularly on day 3, were significant for both 1-month and 3-month mortality. Additionally, among patients with 3-month mortality, the concurrent increase in any two or all three of CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels on day 1 was higher compared to those who did not experience mortality.

A study involving 171 patients found that CRP levels measured a few days after admission, rather than initial concentrations, might be more useful in evaluating treatment response and the outcome of sepsis. CRP levels above 100 mg/L on day 3 in the ICU were found to be predictive of mortality

[9]. In another study evaluating patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia in the ICU, a PCT level below 0.95 ng/ml on day 3 in intubated patients was associated with a 95% survival probability [

11]. Hillas et al. found that in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia, those who developed septic shock had higher PCT levels on both day 1 and day 4 compared to other days [

12]. Similarly, our study found that PCT, CRP, and leukocyte levels on day 3 were significantly higher in patients who experienced mortality within 1 and 3 months compared to those who did not. These findings suggest that these three parameters may serve as useful predictors of mortality.

Multiple studies have indicated that changes in PCT and CRP levels, rather than their absolute values, are more successful in predicting treatment response and survival [

9,

11,

13]. A study conducted in Switzerland emphasized that the initial PCT level did not improve clinical scores for predicting mortality, whereas monitoring PCT kinetics and observing decreasing levels during follow-up were more associated with improved clinical outcomes [

14]. Another study found that the kinetics of PCT, CRP, and, to a lesser extent, WBC markers provided additional prognostic information for mortality risk prediction [

15]. In our study, CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels were found to be high on days 1, 3, 7, and 10 in patients with 3-month mortality. This indicates that persistent elevation in these values may influence long-term mortality.

In a study involving patients with severe influenza and bacterial co-infections, initial PCT and CRP levels at ICU admission were not associated with prognosis [

13]. Similarly, multiple studies have confirmed that a single PCT measurement at ICU admission cannot reliably predict the prognosis of critically ill septic patients [

16]. In our study, logistic regression analysis also did not find a significant relationship between CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels on day 1 and 1-month mortality.

In patients presenting to the emergency department with suspected infection and sepsis, leukocyte, CRP, and PCT levels, when evaluated in combination with clinical severity scores, have been shown to be reliable biomarkers for prognosis [

17]. The combination of PCT and CRP is particularly important in the diagnosis and prognosis of bacterial bloodstream infections [

18]. In patients with severe pneumonia, the concurrent elevation of serum PCT, leukocyte, and CRP levels has been associated with mortality [

19]. Our study also found that 3-month mortality was higher in patients who had a concurrent increase in any two or all three of the PCT, CRP, and leukocyte levels compared to those without mortality. This supports the assumption that the assessment of multiple biomarkers may serve as a diagnostic tool in determining prognosis.

A study on patients with septic shock found that mortality was significantly higher in patients with a BMI < 25 kg/m² compared to those with a BMI > 30 kg/m², and lung and fungal infections were more frequently observed [

20]. A meta-analysis examining the role of increased body mass index in sepsis patients also found that patients with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² were associated with a lower risk of mortality [

21]. The significantly higher incidence of sepsis in the low BMI group has been attributed to the protective effects of estrogens derived from adipocytes and the immunomodulatory effects of adiponectin [

22]. In our study, low BMI was found to be an independent risk factor for both 1-month and 3-month mortality. Considering that obesity is a comorbidity generally associated with poor clinical outcomes, this result highlights the importance of large-scale research on the impact of increased body fat tissue on sepsis pathophysiology.

In a study involving 674 sepsis patients, advanced age, along with low BMI, was identified as an independent risk factor affecting in-hospital mortality [

23]. Moreover, studies on sepsis frequently find that mortality is higher in males compared to females [

2,

24]. This has been attributed to the suppressive effects of male sex hormones (androgens) on cell-mediated immune responses, while female sex hormones provide a protective effect under septic conditions [

25]. In our study, both advanced age and male gender were found to be independent risk factors for 1-month and 3-month mortality in patients with pneumosepsis and septic shock. Additionally, the protective effect of estrogen and other sex hormones observed in females supports the relationship between increased BMI and estrogen effects.

A study conducted in the ICUs of a tertiary hospital in China found that the APACHE-II score calculated on the first day after diagnosis was an independent risk factor for mortality [

26]. Another study demonstrated that the CURB-65 score performed better than other severity scores in predicting the risk of death among septic patients [

27]. In a study examining the effectiveness of CURB-65 and APACHE-II scores in assessing sepsis severity and predicting mortality, both scores were found to be successful in predicting mortality. However, since the CURB-65 score is a simple calculation, it has the advantage of being quickly calculated in crowded emergency departments, making it superior to other complex severity scores [

28]. The combination of CRP, PCT, and WBC elevations with a high CURB-65 score further enhances the ability to identify patients at risk of poor clinical outcomes [

15]. In our study, a significant relationship was found between increases in CURB-65 scores and elevations in CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels at different follow-up times. Additionally, CURB-65 and APACHE-II scores were independent predictors of both 1-month and 3-month mortality in patients with pneumosepsis and septic shock. This suggests that the combined use of scoring systems and biomarkers may provide more accurate results in predicting prognosis.

In sepsis patients, the CCIS is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality and also a predictive factor for the development of postoperative sepsis [

29,

30]. A study found that patients with high CCIS were more likely to progress from bacteremia to sepsis [

31]. Furthermore, it has been concluded that the CCIS is a one-year mortality predictor in patients presenting to the emergency department with severe sepsis or septic shock [

32]. In our study, CCIS was found to be a predictor of both 1-month and 3-month mortality. This supports the notion that comorbidity and advanced age worsen the general condition of patients with sepsis and septic shock.

Sepsis is an acute event and has not been associated with long-term mortality due to acute organ dysfunction. However, treatment limitation decisions related to the underlying disease also affect ICU mortality [

33]. In our study, a shorter ICU stay was significantly associated with 1-month mortality. This was attributed to the acute deterioration caused by sepsis and septic shock.

Our study has several limitations. First, the retrospective and single-center design of our study limits the generalizability of the results. Second, some patients progressed to septic shock after being admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of sepsis. Similarly, patients who were receiving monotherapy with antibiotics at the time of ICU admission and subsequently experienced worsening of their condition were switched to combination therapy. Therefore, the distinction between sepsis/septic shock; between monotherapy/combination therapy was made only on the day of admission to the ICU. The third limitation was the unclear etiology in patients who developed a dialysis indication after sepsis/septic shock. Fourth, some patients’ CRP, PCT, and leukocyte values on days 3, 7, and 10 could not be recorded due to early mortality in the ICU or transfer to an external facility.

In conclusion, although PCT, CRP, and leukocyte levels measured at the time of admission were not significantly associated with 1-month mortality in patients with pneumosepsis or pneumonia-related septic shock, the persistent elevation of these values, male gender, advanced age, low BMI, and high scores on CCIS, CURB-65, and APACHE-II were significantly associated with 3-month mortality. The concurrent elevation of CRP, PCT, and leukocyte levels is a determinant in predicting long-term prognosis. More homogeneous and large-scale prospective studies will be highly beneficial in clarifying this topic.

Author Contributions

All of the authors declare that they have all participated in the concept, design, literature search, data collection, analyses, writing and that they have approved the final version.

Funding

This study received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical Decision No: 2024-BÇEK/57, dated 24.04.2024, Ankara Ataturk Sanatorium Traning and Research Hospital, Clinical Research Ethics Committee.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All the authors mentioned in the manuscript have agreed for authorship, read and approved the manuscript, and given consent for submission and subsequent publication of the manuscript. The manuscript in part or in full has not been submitted or published anywhere.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C. M.; French, C., Machado, F. R.; Mcintyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Critical care medicine. 2021, 49(11), e1063-e1143. [CrossRef]

- Basodan, N.; Al Mehmadi, A. E.; Al Mehmadi, A. E.; Aldawood, S. M.; Hawsawi, A.; Fatini, F.; Mulla, Z.M.; Nawwab, W.; Alshareef, A.; Almhmadi, A.H.; et al. Septic shock: management and outcomes. Cureus. 2022, 14(12). [CrossRef]

- Kim, W. Y.; Lee, Y. J.; Lim, S. Y.; Koh, S. O.; Choi, W. I.; Kim, S. C.; Chon, G.R.; Kim, J.H.; Kim J.Y.; Lim, J.; et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of pneumonia and sepsis: multicenter study. Minerva Anestesiol. 2013, 79(12), 1356-1365.

- Lu, J.; Yu, X.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Xu, L. Clinical usefulness of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as outcome predictors of septic shock. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2020, 13(11), 8721-8727.

- Collazos, J.; De La Fuente, B.; De La Fuente, J.; García, A.; Gómez, H.; Menéndez, C.; Enríquez, H.; Sánchez, P.; Alonso, M.; López-Cruz, I.; et al. Factors associated with sepsis development in 606 Spanish adult patients with cellulitis. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2020, 20, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Torres, L. K.; Pickkers, P.; van der Poll, T. (2022). Sepsis-induced immunosuppression. Annual review of physiology. 2022, 84(1), 157-181. [CrossRef]

- Davenport, E. E.; Burnham, K. L.; Radhakrishnan, J.; Humburg, P.; Hutton, P.; Mills, T. C.; Rautanen, A.; Gordon, A. C.; Garrard, C.; Hill, A.V.S.; et al. Genomic landscape of the individual host response and outcomes in sepsis: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2016,

4:259–271. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, J.; Khan, S.; Zahra, R.; Razaq, A.; Zain, A.; Razaq, L.; Razaq, M. Role of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as predictors of sepsis and in managing sepsis in postoperative patients: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022, 14(11). [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-A.; Yang, J.H.; Lee, D.; Park, C.-M.; Suh, G.Y.; Jeon, K.; Cho, J.; Baek, S.Y.; Carriere, K.C.; Chung, C.R. Clinical Usefulness of Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein as Outcome Predictors in Critically Ill Patients with Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10(9): e0138150. [CrossRef]

- Sayıner, A.; Babayigit, C.; Azap, A.; Yalci, A.; Coskun, A.S.; Edis, E.C.; Evren, E.; Basara, E.; Demirogen, E.; Altay, F.A.; et al. Turk Toraks Dernegi Erişkinlerde Toplumda Gelisen Pnomoniler Tani ve Tedavi Uzlasi Raporu. Türk Toraks Derg. 2021. ISBN: 978-605-74980-6-9. Web: https://www.toraks.org.tr.

- Boussekey, N.; Leroy, O.; Alfandari, S.; Devos, P.; Georges, H.; Guery, B. Procalcitonin kinetics in the prognosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive care medicine. 2006, 32: 469-472. [CrossRef]

- Hillas, G.; Vassilakopoulos, T.; Plantza, P.; Rasidakis, A.; Bakakos, P. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin as predictors of survival and septic shock in ventilator-associated pneumonia. European Respiratory Journal. 2010. 35(4), 805-811. [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, R.; Moreno, G.; Martín-Loeches, I.; Gomez-Bertomeu, F.; Sarvisé, C.; Gómez, J.; Bodí, M.; Díaz, E.; Papiol, E.; Trefler, S.; et al. Prognostic Value of Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein in 1608 Critically Ill Patients with Severe Influenza Pneumonia. Antibiotics. 2021. 10, 350. [CrossRef]

- Schuetz, P.; Suter-Widmer, I.; Chaudri, A.; Christ-Crain, M.; Zimmerli, W.; Mueller, B. Prognostic value of procalcitonin in community-acquired pneumonia. European Respiratory Journal. 2011. 37(2), 384-392. [CrossRef]

- Zhydkov, A.; Christ-Crain, M.; Thomann, R.; Hoess, C.; Henzen, C.; Zimmerli, W.; Mueller, B.; , Schuetz, P.; ProHOSP Study Group. (2015). Utility of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein and white blood cells alone and in combination for the prediction of clinical outcomes in community-acquired pneumonia. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 2015. 53(4), 559-566. [CrossRef]

- Poddar, B.; Gurjar, M.; Singh, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Singh, R.; Azim, A.; Baronia, A. Procalcitonin kinetics as a prognostic marker in severe sepsis/septic shock. Indian journal of critical care medicine: peer-reviewed, official publication of Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine. 2015. 19(3), 140. [CrossRef]

- Magrini, L.; Gagliano, G.; Travaglino, F.; Vetrone, F.; Marino, R.; Cardelli, P.; Salerno, G.; Di Somma, S. Comparison between white blood cell count, procalcitonin and C reactive protein as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of infection or sepsis in patients presenting to emergency department. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine (CCLM). 2014. 52(10), 1465-1472. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; La, M.; Sun, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, D.; Liu, X.; Kang, Y. Diagnostic Value and Prognostic Significance of Procalcitonin Combined with C-Reactive Protein in Patients with Bacterial Bloodstream Infection. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine. 2022. 2022(1), 6989229. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, W. Serum procalcitonin levels in predicting the prognosis of severe pneumonia patients and its correlation with white blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2020. 13(2), 809-815.

- Wacharasint, P.; Boyd, J.H.; Russell, J.A.; Walley, K.R. One size does not fit all in severe infection: obesity alters outcome, susceptibility, treatment, and inflammatory response. Critical care. 2013. 17, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Liu, C.; Huang, C.; Fang, X. The role of increased body mass index in outcomes of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC anesthesiology. 2017. 17, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mica, L.; Vomela, J.; Keel, M.; Trentz, O. The impact of body mass index on the development of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis in patients with polytrauma. Injury. 2012. 45(1), 253-258. [CrossRef]

- Yuzhen, Z. H. E. N. G.; Yanjun, Z. H. E. N. G.; Yi, Z. H. O. U.; Xing, Q. I.; Weiwei, C. H. E. N.; Wen, S. H. I.; Weijun, Z.H.O.U.; Zhitao, Y.A.N.G.; Ying, C.H.E.N.; Enqiang, M.A.O.; et al. The clinical retrospective analysis of 674 hospitalized patients diagnosed with sepsis in a general hospital. Journal of Internal Medicine Concepts & Practice. 2022. 17(04), 278. [CrossRef]

- Suarez De La Rica, A.; Gilsanz, F.; Maseda, E. Epidemiologic trends of sepsis in western countries . Ann Transl Med. 2016. 4:325. [CrossRef]

- Angele, M. K.; Pratschke, S.; Hubbard, W. J.; & Chaudry, I. H. Gender differences in sepsis: cardiovascular and immunological aspects. Virulence. 2014. 5(1), 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Xiao, M.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, X.; Chen, X.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y. (2021). Epidemiology and mortality of sepsis in intensive care units in prefecture-level cities in Sichuan, China: a prospective multicenter study. Med Sci Monit. 2021. 27, e932227-1. [CrossRef]

- Marwick, C. A.; Guthrie, B.; Pringle, J. E.; McLeod, S. R.; Evans, J. M.; Davey, P. G. Identifying which septic patients have increased mortality risk using severity scores: a cohort study. BMC anesthesiology. 2014. 14:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Hatem, S.A.; Haiba, D.E.M.; Sherif, Y.M.; Engy, S.A. CURB-65 versus APACHE II as a Prognostic Score to Assess Severity of Sepsis in Critically Ill Geriatric Patients. Med.J.Cairo Univ. 2021. 89(6):2307-2318. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, K. S.; Hsann, Y. M.; Lim, V.; Ong, B. C. The effect of comorbidity and age on hospital mortality and length of stay in patients with sepsis. Journal of critical care. 2010. 25(3), 398-405. [CrossRef]

- Emami, R. S. H.; Mohammadi, A.; Alibakhshi, A.; Jalali, M.; Ghajarzadeh, M. Incidence of post-operative sepsis and role of Charlson co-morbidity score for predicting postoperative sepsis. Acta Medica Iranica. 2016. 54 (5). 318-322.

- Sinapidis, D.; Kosmas, V.; Vittoros, V.; Koutelidakis, I. M.; Pantazi, A.; Stefos, A.; Katsaros, K. E.; Akinosoglou, K.; Bristianou, M.; Toutouzas, K.; et al. Progression into sepsis: an individualized process varying by the interaction of comorbidities with the underlying infection. BMC infectious diseases. 2018. 18, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Huddle, N.; Arendts, G.; Macdonald, S. P. J.; Fatovich, D. M.; Brown, S. G. A. Is comorbid status the best predictor of one-year mortality in patients with severe sepsis and sepsis with shock?. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. 2013. 41(4), 482-489. [CrossRef]

- Adrie, C.; Francais, A.; Alvarez-Gonzalez, A.; Mounier, R.; Azoulay, E.; Zahar, J. R.; Clec’h, C.; Goldgran-Toledano, D.; Hammer, L.; Descorps-Declere, A.; et al. Model for predicting short-term mortality of severe sepsis. Critical Care. 2009. 13, 1-14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).