1. Introduction

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome characterized by a dysregulated physiological, pathological, and biochemical response to infection, leading to life-threatening organ dysfunction [

1]. It remains a major cause of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality, accounting for approximately 10% of Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admissions, with in-hospital mortality rates estimated between 10% and 20% [

2]. The complexity of sepsis pathophysiology and its clinical severity necessitate clear diagnostic criteria and effective treatment strategies.

According to Sepsis-3, sepsis is defined as “

a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection” [

1]. Organ dysfunction is operationalized as an acute increase in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score of ≥2 points in the presence of infection [

1]. Septic shock is defined as a subset of sepsis involving: a) persistent hypotension requiring vasopressors to maintain a mean arterial pressure (MAP) ≥65 mmHg, and b) serum lactate >2 mmol/L (18 mg/dL) despite adequate fluid resuscitation.This condition is associated with in-hospital mortality exceeding 40% [

1].

Early recognition and prompt initiation of treatment are essential to improving outcomes in patients with sepsis. Numerous studies underscore the mortality risk associated with delayed treatment. Each hour of delay in antibiotics increased mortality by 4–7% in a cohort of over 35,000 patients [

3]. Survival benefits found when antibiotics administered within the first hour, particularly in septic shock [

4]. Current sepsis guidelines further confirmed that early interventions limit the progression of organ failure [

5]. A 2024 meta-analysis involving 22 studies revealed that ED sepsis alert systems improved adherence to treatment bundles, significantly with positive downstream effects on mortality (reduced by 19%) and organ support [

6].

Τhe heterogeneous clinical presentation of sepsis necessitate simple, rapid, and reliable clinical screening tools. To this end, Sepsis-3 introduced the quick SOFA (qSOFA) score in 2016, a simplified version of the SOFA score designed to facilitate early identification of patients at risk for poor outcomes [

1]. A score of ≥2 suggests an increased risk of mortality and prolonged ICU stay in patients with suspected infection. The qSOFA score is intended for use across diverse settings, including the ED, hospital wards, and prehospital environments.

In addition to qSOFA, several other scoring systems are used for the early identification of sepsis in the ED. Among the most widely studied are the Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria, the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), and the National Early Warning Score (NEWS/NEWS2).

The SIRS criteria originally introduced in the SEPSIS-1 definitions and were used to describe the systemic inflammatory response to infection [

7].

MEWS and NEWS2 incorporate clinical parameters (6 and 7 respectively) while they were not specifically designed for patients with infection, they are broadly employed for detecting clinical deterioration in acutely ill patients [

8,

9].

In 2021, updated international guidelines for sepsis no longer recommend using qSOFA or other early warning scores as single screening tools for sepsis due to concerns over their limited sensitivity and specificity [

5]. Notably, while the recommendation to avoid their use as stand-alone diagnostic tools is strong, the quality of supporting evidence is only moderate, underscoring the ongoing need for further research.

Despite the large number of studies comparing early detection sepsis scores in the ED, considerable heterogeneity persists in terms of sepsis definitions, score thresholds, and selected outcomes [

10]. Moreover, most of these studies are retrospective, a design inherently associated with a higher risk of systematic bias than prospective studies [

11].

The present study aims to overcome these limitations and provide robust evidence regarding whether any scoring system significantly outperforms others in the early identification of ED patients with infection who are at risk for adverse outcomes. The analysis into whether there is a statistically significant difference between the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC) values of the scales in terms of their prognostic ability is, to the best of our knowledge, something that has not been conducted in any previous research to date.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim and Study Design

A prospective observational study designed to compare the prognostic accuracy of four clinical scoring systems, SIRS, MEWS, NEWS2, and qSOFA in predicting 28-day in-hospital mortality and ICU stay ≥3 days among patients presenting to the ED with suspected infection. A convenience sampling method was used.

2.2. Study Population

The study cohort comprised adult patients (≥18 years) who presented to the ED with suspected infection and had complete follow-up data available either during their ED stay or subsequent hospital admission. The inclusion of adults only was based on the fact that the evaluated scoring systems were designed for and extensively studied in adult populations [

1,

7,

8,

9].

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

2.3. Data Collection Tool

A custom-designed data collection form was developed for this study to ensure standardized documentation. The form included the following data fields: demographic information, arrival and triage times, relevant medical history, vital signs and physical examination findings, laboratory test results. In this form also recorded the scores of the four scales that were being compared.

To minimize bias, all clinical scores (SIRS, MEWS, NEWS2, and qSOFA) were calculated at the time of patient presentation based solely on available data, before any knowledge of outcomes such as mortality or ICU stay. Outcome data were collected separately after hospitalization, ensuring that score calculation was blinded to final clinical outcomes.

SIRS scale define a positive result as the presence of at least two of the following: a) body temperature >38°C or <36°C, b) heart rate >90 beats/min, c) respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO₂) <32 mmHg, and d) white blood cell count (WBC) >12,000/mm³, <4,000/mm³, or >10% immature (band) forms [

7].

MEWS scale evaluates six physiological parameters: temperature, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, respiratory rate, level of consciousness (based on the AVPU scale: Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive), and urine output-although the latter is typically omitted in ED settings [

8,

12]. The total score ranges from 0 to 17, with a score ≥ 4 indicating increased risk.

NEWS scale and its updated version NEWS2 incorporate seven variables: respiratory rate, saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO₂), use of supplemental oxygen, SBP, heart rate, temperature, and neurological status (AVPU scale) [

9]. The score ranges from 0 to 20, with a score ≥ 5 indicating increased risk. NEWS2 refining SpO₂ assessment in patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory disease, targeting an SpO₂ range of 88–92%.

qSOFA scale comprises three criteria: altered mental status with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score <15, systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≤100 mmHg, and respiratory rate ≥22 breaths/min [

1,

13]. A score of ≥2 suggests an increased risk of mortality and prolonged ICU stay in patients with suspected infection.

In summary, the following cutoff values were used to define a positive score: SIRS ≥ 2, MEWS ≥ 4, NEWS2 ≥ 5, and qSOFA ≥ 2.

2.4. Study Setting and Duration

The study was carried out at a general hospital in the Attica region, Greece, with a medium capacity of approximately 400–450 beds. The hospital offers 24/7 emergency services across most specialties, except neurology, orthopedics, gynecology, and pediatrics. The absence of pediatric care facilitated the exclusion of patients under 18 years of age.

The data collection period spanned from December 1, 2023, to December 1, 2024, with patient screening and initial evaluation occurring at ED triage.

2.5. Study Procedures and Outcome Measures

Eligible patients were initially assessed during triage in the ED. Inclusion was based on clinical suspicion of infection, as determined by a combination of subjective symptoms, objective findings, and relevant medical history. The decision to include a patient was made by the ED triage physician, and data collection was performed by the researchers.

To minimize time-related variability, only patients assessed within one hour of ED arrival were included. Patients evaluated after one hour were excluded, as delays can significantly influence the values of the clinical scores [

14,

15].

In cases where the presence of infection was initially uncertain, patients were provisionally included and later excluded if alternative diagnoses were confirmed, either during their ED stay or post-admission.

Infection confirmation was based on one or more of the following criteria (in order of priority):

Diagnosis coded as infection using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) [

16]

Positive microbiological cultures within 24 hours of presentation

Pathogen identification via molecular or rapid antigen detection methods (e.g., influenza test)

Urine microscopy showing significant pyuria

Abnormal WBC counts (>12,000/mm³, <4,000/mm³, or >10% immature neutrophils)

Radiographic evidence consistent with infection

Initiation of antibiotics within the first 24 hours

The criteria for infection were established based on the rationale of the study, the commonly accepted standards in everyday clinical practice, and those used by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) [

17]. WBC count was selected due to its established use as a criterion for infection in the SIRS scale [

7]. When infection status remained uncertain, the case was discussed with the attending physician, whose clinical judgment guided final inclusion or exclusion.

For patients discharged from the ED without further diagnostic testing, inclusion was based solely on clinical findings and the ED physician’s judgment.

Follow-up was conducted using the hospital’s electronic health records system. Data were collected on laboratory results, hospital or ICU admission, duration of hospitalization, 28-day in-hospital mortality.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To evaluate the prognostic performance of each clinical scoring system for the primary outcomes (28-day in-hospital mortality and ICU stay of ≥3 days) the following metrics were calculated: sensitivity, specificity, overall accuracy, positive prognostic value (PPV), negative prognostic value (NPV), and AUROC.

To compare the discriminatory ability of each scoring system, pairwise AUROC comparisons were performed using the DeLong test, which accounts for the correlated nature of the AUROCs derived from the same patient population [

18,

19].

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. However, to adjust for multiple comparisons (six pairwise comparisons in total) and control for Type I error due to multiple testing, the Bonferroni correction was used, yielding a corrected alpha level of 0.0083 (i.e., 0.05/6).

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29.0.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

Between December 1, 2023, and December 1, 2024, a total of 918 patients presenting to the ED were screened for suspected infection. Of these, 566 patients met the initial inclusion criteria. After excluding 36 patients with final diagnoses inconsistent with infection, 530 patients were included in the final analysis.

The mean age of the cohort was 63.7 years (SD ±18.5, range 18–101), and 53.96% were female. The most frequent site of infection was the lower respiratory tract (55.6%), followed by the urinary tract (24.9%).

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Clinical Scores and Outcomes

The proportions of patients with positive screening results were SIRS ≥2: 52.8%, MEWS ≥4: 25.3%, NEWS2 ≥5: 48.3% and qSOFA ≥2: 18.3%. The primary clinical outcomes observed for 28-day in-hospital mortality was 8.7% (n=46) and for ICU stay ≥3 days was 4.3% (n=23).

3.3. Prognostic Performance for 28-Day In-Hospital Mortality

The performance metrics of each scoring system for predicting 28-day mortality are presented in

Table 2.

SIRS demonstrated the highest sensitivity (89.13%) but low specificity (43.39%), resulting in frequent false positives and a low positive predictive value (PPV, 13.02%).

MEWS showed moderate sensitivity (60.87%) and good specificity (78.10%), with an overall accuracy of 76.60%.

NEWS2 achieved the highest sensitivity (97.83%) with strong negative predictive value (NPV, 99.64%) but moderate specificity (56.4%).

qSOFA achieved the highest overall accuracy (84.91%), with strong specificity (86.16%) and NPV (96.98%), though sensitivity was moderate (71.74%).

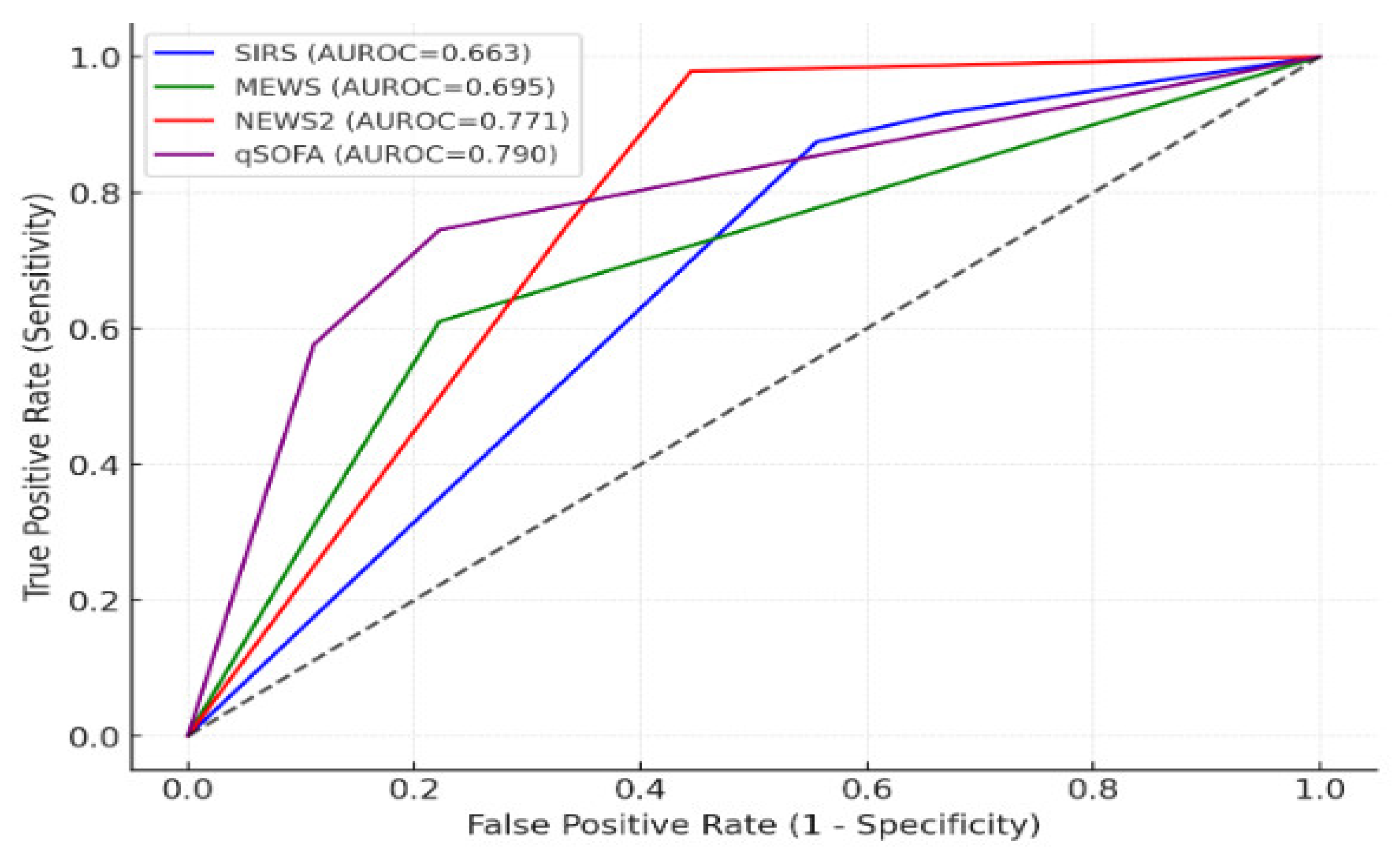

Pairwise comparisons using the DeLong test (

Table 3,

Figure 1) revealed that NEWS2 significantly outperformed SIRS (p=0.0005) and MEWS (p=0.003). qSOFA significantly outperformed SIRS (p=0.0002) and MEWS (p=0.003). No statistically significant difference was observed between NEWS2 and qSOFA (p=0.15).

3.4. Prognostic Performance for ICU Stay ≥3 Days

The performance metrics for predicting ICU stays of ≥3 days are presented in

Table 4.

SIRS exhibited high sensitivity (86.96%) but poor specificity (41.81%) and low overall accuracy (44.29%).

MEWS achieved moderate sensitivity (65.22%) and good specificity (76.5%), with an overall accuracy of 76.01%.

NEWS2 demonstrated very high sensitivity (91.30%) and NPV (99.26%), but with moderate specificity (53.65%) and overall accuracy (55.57%).

qSOFA showed the highest specificity (82.8%) and accuracy (81.04%), although sensitivity was moderate (56.52%).

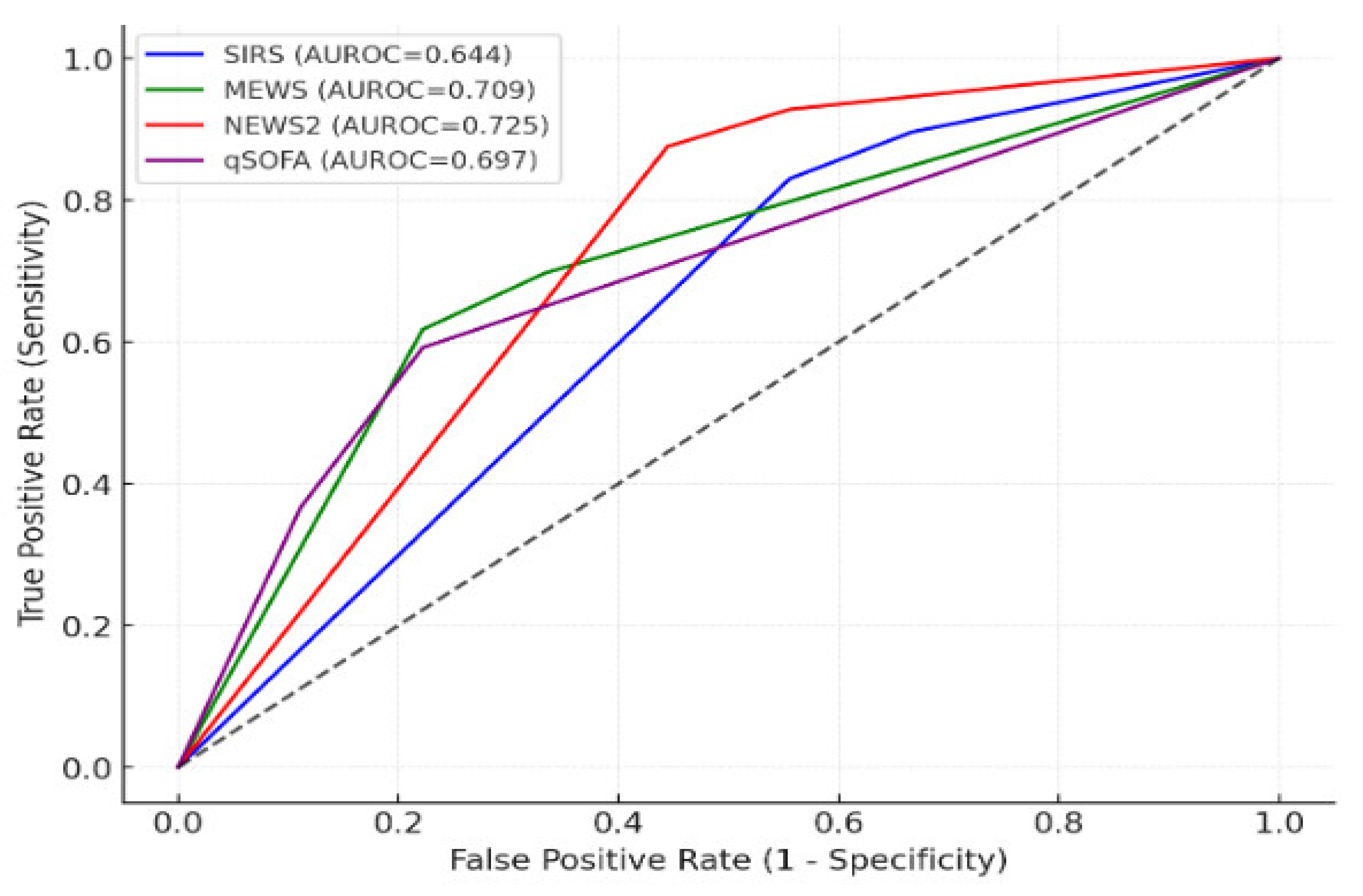

Pairwise comparisons (

Table 5,

Figure 2) showed that NEWS2 significantly outperformed SIRS (p=0.001). MEWS significantly outperformed SIRS (p=0.024) and no significant differences were found between NEWS2 and MEWS (p=0.563), or between NEWS2 and qSOFA (p=0.314).

3.5. Summary of Key Findings

qSOFA demonstrated the highest overall prognostic accuracy for both outcomes, although its moderate sensitivity suggests it may miss some early cases.

NEWS2 demonstrated excellent sensitivity and NPV, making it particularly useful for ruling out patients at low risk, albeit with slightly lower specificity.

SIRS showed high sensitivity but poor specificity, limiting its utility as a standalone prognostic tool.

MEWS offered moderate balanced performance but was outperformed by both NEWS2 and qSOFA.

4. Discussion

In this study, we compared the prognostic performance of four commonly used scoring systems -SIRS, MEWS, NEWS2, and qSOFA- in predicting clinical outcomes among 530 patients presenting to the ED with suspected infection. Our findings suggest that qSOFA and NEWS2 demonstrated greater prognostic performance for both 28-day in-hospital mortality and ICU stay ≥3 days compared to SIRS and MEWS.

Although qSOFA showed a slightly higher AUROC than NEWS2 for mortality prediction, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.15). This indicates that while both qSOFA and NEWS2 offer improved prognostic accuracy relative to SIRS and MEWS, the marginal difference between qSOFA and NEWS2 may not correspond to clinically significant superiority. Similarly, both qSOFA and NEWS2 significantly outperformed SIRS and MEWS in predicting prolonged ICU stays, with no statistically significant difference between the two higher-performing scores.

These findings must be interpreted in the context of outcome prevalence. A prevalence of 10–20% is often desirable in clinical prediction model studies to ensure sufficient power [

20]. In our study, 28-day in-hospital mortality had a prevalence of 8.7%, which is considered reasonably robust. However, the prevalence of ICU stay ≥3 days was lower (4.3%), which may have limited the statistical power for that outcome. Importantly, outcome prevalence directly affects PPV and NPV. With lower prevalence, PPV tends to decrease, making it less likely that a high-risk classification by the score truly reflects adverse outcomes [

21]. Nevertheless, both outcomes evaluated are clinically significant, and even with relatively low prevalence, the prognostic information provided remains valuable for patient triage and resource allocation.

Our findings are consistent with those of Ruan et al. [

11], who conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on prospective ED studies comparing qSOFA and SIRS. Their analysis concluded that qSOFA has higher specificity but lower sensitivity than SIRS for predicting mortality. Despite this trade-off, the simplicity and rapid applicability of qSOFA make it a practical tool for early identification of high-risk patients in emergency settings. Importantly, the authors also noted that qSOFA cannot fully replace SIRS, particularly due to the risk of missing early sepsis cases that have not yet developed overt organ dysfunction.

Several retrospective studies have also shown superior prognostic performance of NEWS/NEWS2 compared to other scales, especially for predicting mortality and ICU admission [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, as with all risk scores, no single tool provides both high sensitivity and specificity across all clinical contexts. Adjusting cutoff thresholds to increase sensitivity inevitably reduces specificity, and vice versa.

Based on the findings of our study, qSOFA and NEWS2 emerged as the most effective tools for predicting adverse outcomes in the ED setting.

The qSOFA score, composed of only three variables, is quick to calculate, requires no laboratory testing, and is especially suited for resource-limited environments [

28]. Its high specificity and NPV make it useful for identifying patients at low risk of deterioration. However, qSOFA is not designed to detect early sepsis and may miss patients in the initial stages, before organ dysfunction manifests. As such, it is best used as a triage flag-prompting closer monitoring, early resuscitation, and escalation of care when positive.

NEWS2, which incorporates a broader range of vital signs and considers oxygen requirements, is more comprehensive and better suited to ongoing patient monitoring. It performs well in predicting deterioration but may overestimate risk in patients with chronic conditions, such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), leading to potential overtreatment or alarm fatigue.

The MEWS scale is a simpler tool that tracks vital signs and mental status but demonstrated inferior performance compared to qSOFA and NEWS2. It may be prone to false positives, which can strain clinical workflows and reduce its reliability in identifying truly high-risk patients.

The SIRS criteria remain widely used and familiar, particularly among general medical staff. However, SIRS lacks specificity and often flags stable or mildly unwell patients. Its high false-positive rate reduces its value as a standalone screening tool. Nevertheless, SIRS may still play a supportive role when used in combination with more specific tools like NEWS2 or qSOFA.

According to our findings, we propose a pragmatic workflow for sepsis screening in the ED:

Use qSOFA as an initial triage tool for rapid risk stratification.

If qSOFA is positive, initiate urgent monitoring and early intervention.

Use NEWS2 for continuous monitoring, especially during the ED stay or inpatient follow-up.

Combine clinical scores with clinical judgment, laboratory data (e.g., lactate, CRP), and microbiological findings to confirm diagnosis and guide treatment decisions.

This study has several notable strengths. First, the use of a robust sample size (n = 530) enhances the reliability and statistical power of the findings. Second, the application of the DeLong test, a well-established non-parametric method for comparing correlated AUROC values, strengthens the validity of the comparative analysis among the scoring systems.

However, certain limitations must be acknowledged. As this was a single-center study using a convenience sample, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. While AUROC values provide valuable insights into overall discriminatory performance, they may not fully capture clinically relevant trade-offs between sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, factors that are critical for decision-making in real-world emergency care settings.

Future research should aim to validate these findings across multicenter cohorts and diverse healthcare environments and should also assess the impact of these scoring systems on clinical decision-making, patient outcomes, and resource utilization.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the superior prognostic performance of qSOFA and NEWS2 compared to SIRS and MEWS in predicting adverse clinical outcomes, including 28-day in-hospital mortality and prolonged ICU stay ≥3 days in patients presenting to the ED with suspected infection. While qSOFA showed a modest AUROC advantage over NEWS2, the difference was not statistically significant, suggesting that both scores offer comparable prognostic value.

The simplicity and rapid applicability of qSOFA make it especially well-suited for initial triage, particularly in resource-limited or high-throughput emergency settings. In contrast, NEWS2 provides the advantage of continuous patient monitoring, although it may overestimate risk in certain patient populations, such as those with chronic comorbidities.

Overall, SIRS and MEWS were less effective, with SIRS notably associated with a high false-positive rate, reducing its utility as a stand-alone screening tool. Despite the relatively low prevalence of ICU admission in our cohort, the consistent prognostic strength of qSOFA and NEWS2 supports their clinical relevance in early risk stratification.

An optimal ED workflow would involve qSOFA for initial triage, NEWS2 for ongoing monitoring, and integrating clinical judgment with laboratory and microbiological data for diagnostic confirmation and escalation of care.

Further studies are needed to validate this workflow in multicenter or real-world ED settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.X. and S.T.; Methodology, D.X, and M.K.; Software, D.X. and M.K; Validation, M.K and V.Kal.; Formal Analysis, D.X., and V.Kar.; Investigation, D.X., K.T, A.S and V.Kar; Resources, D.X.; Data Curation, D.X., V.Kar.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.X.; Writing – Review & Editing, D.X.; Visualization, M.K.; Supervision, A.M, A.I and S.T; Project Administration, D.X,. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of SISMANOGLIO GENERAL HOSPITAL OF ATTICA (22264/09-11-2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as all data were obtained as part of standard care and involved no identifiable personal information.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from X.D. (the first author). The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| SIRS |

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| MEWS |

Modified Early Warning Score |

| NEWS2 |

National Early Warning Score 2 |

| qSOFA |

quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| AUROC |

Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve |

| SOFA |

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| MAP |

Mean Arterial Pressure |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale |

| SBP |

Systolic Blood Pressure |

| PaCO2

|

Partial pressure of Carbon dioxide |

| AVPU |

Alert Voice Pain Unresponsive |

| WBC |

White Blood Cells |

| SpO₂ |

Saturation of peripheral Oxygen |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| ECDC |

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| PPV |

Positive Prognostic Value |

| NPV |

Negative Prognostic Value |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

References

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, Y.; Lemachatti, N.; Krastinova, E.; van Laer, M.; Claessens, Y.E.; Avondo, A.; Occelli, C.; Feral-Pierssens, A.L.; Truchot, J.; Ortega, M.; et al. Prognostic Accuracy of Sepsis-3 Criteria for In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Suspected Infection Presenting to the minimizency Department. JAMA 2017, 317, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, C.W.; Gesten, F.; Prescott, H.C.; Friedrich, M.E.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Phillips, G.S.; Lemeshow, S.; Osborn, T.; Terry, K.M.; Levy, M.M. Time to Treatment and Mortality during Mandated Emergency Care for Sepsis. N Engl J Med 2017, 376, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, Y.; Kang, D.; Ko, R.E.; Lee, Y.J.; Lim, S.Y.; Park, S.; Na, S.J.; Chung, C.R.; Park, M.H.; Oh, D.K.; et al. Time-to-antibiotics and clinical outcomes in patients with sepsis and septic shock: a prospective nationwide multicenter cohort study. Crit Care 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.; Rhodes, A.; Alhazzani, W.; Antonelli, M.; Coopersmith, C.M.; French, C.; Machado, F.R.; McIntyre, L.; Ostermann, M.; Prescott, H.C.; Schorr, C.; et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med 2021, 47, 1181–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ko, R.; Lim, S.Y.; Park, S.; Suh, G.Y.; Lee, Y.J. Sepsis Alert Systems, Mortality, and Adherence in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bone, R.; Balk, R.A.; Frank, B.; Cerra, R.; Dellinger, P.; Fein, A.M.; Knaus, W.A.; Schein, R.M.H.; Sibbald, W.J. Definitions for Sepsis and Organ Failure and Guidelines for the Use of Innovative Therapies in Sepsis. Chest 1992, 101, 1644–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner-Thorpe, J.; Love, N.; Wrightson, J.; Walsh, S.; Keeling, N. The Value of Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) in Surgical In-Patients: A Prospective Observational Study. The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England 2006, 88, 571–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2: Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS; Updated report of a working party; RCP: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-86016-682-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sabir, L.; Ramlakhan, S.; Goodacre, S. Comparison of qSOFA and Hospital Early Warning Scores for prognosis in suspected sepsis in emergency department patients: a systematic review. Emergency Medicine Journal 2021, 39, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Dianshan, K.; Dalin, L. Prognostic Accuracy of qSOFA and SIRS for Mortality in the Emergency Department: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Emergency Medicine International 2022, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenhouse, C.; Coates, S.; Tivey, M.; Allsop, P.; Parker, T. Prospective Evaluation of a Modified Early Warning Score to Aid Earlier Detection of Patients Developing Critical Illness on a General Surgical Ward. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2000, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, C.W.; Liu, V.X.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Brunkhorst, F.M.; Rea, T.D.; Scherag, A.; Rubenfeld, G.; Kahn, J.M.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Escobar, G.J.; Angus, D.C. Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Jo, I.J.; Lee, S.U.; Lee, T.R.; Yoon, H.; Cha, W.C.; Sim, M.S.; Shin, T.G. Low Accuracy of Positive qSOFA Criteria for Predicting 28-Day Mortality in Critically Ill Septic Patients During the Early Period After Emergency Department Presentation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2018, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latten, G.H.P.; Polak, J.; Merry, A.H.H.; Muris, J.W.M.; ter Maaten, J.C.; Olgers, T.J.; Cals, J.W.L.; Stassen, P.M. Frequency of Alterations in qSOFA, SIRS, MEWS and NEWS Scores during the Emergency Department Stay in Infectious Patients: A Prospective Study. Int J Emerg Med 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision.; Fifth edition, World Health Organization, 2016.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Point prevalence survey of healthcare associated infections and antimicrobial use in European acute care hospitals, ECDC, Sweden, 2024. [CrossRef]

- DeLong, E.R.; DeLong, D.M.; Clarke-Pearson, D.L. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, 837–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 2006, 27, 8–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G.; Bland, J.M. Statistics Notes: Diagnostic Tests 1: Sensitivity and Specificity. BMJ 1994, 308, 1552–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, P.M. Towards Complete and Accurate Reporting of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy: The STARD Initiative. BMJ 2003, 326, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, S.P.; Perreard, I.; MacKenzie, T.; Calderwood, M. Improvement of Sepsis Identification through Multi-Year Comparison of Sepsis and Early Warning Scores. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2022, 51, 239–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, O.A.; Usman, A.A.; Ward, M.A. Comparison of SIRS, qSOFA, and NEWS for the Early Identification of Sepsis in the Emergency Department. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2019, 37, 1490–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, A.; Alsma, J.; Verdonschot, R.J.C.G.; Rood, P.P.M.; Zietse, R.; Lingsma, H.F.; Schuit, S.CE. Predicting Mortality in Patients with Suspected Sepsis at the Emergency Department; A Retrospective Cohort Study Comparing qSOFA, SIRS and National Early Warning Score. PLOS ONE 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goulden, R.; Hoyle, M.-C.; Monis, J.; Railton, D.; Riley, V.; Martin, P.; Martina, R.; Nsutebu, E. qSOFA, SIRS and NEWS for Predicting Inhospital Mortality and ICU Admission in Emergency Admissions Treated as Sepsis. Emergency Medicine Journal 2018, 35, 345–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Churpek, M.; Snyder, A.; Han, X.; Sokol, S.; Pettit, N.; Howell, M.D.; Edelson, D.P. Quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment, Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, and Early Warning Scores for Detecting Clinical Deterioration in Infected Patients Outside the Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2017, 195, 906–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudd, K.E.; Seymour, C.W.; Aluisio, A.R.; Augustin, M.E.; Bagenda, D.S.; Beane, A.; Byiringiro, J.C.; Chang, C.-C.H.; Colas, L.N.; Day, N.P.J. Association of the Quick Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) Score With Excess Hospital Mortality in Adults With Suspected Infection in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA 2018, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, A.; Evans, L.E.; Alhazzani, W.; Levy, M.M.; Antonelli, M.; Ferrer, R.; Kumar, A.; Sevransky, J.E.; Sprung, C.L.; Nunnally, M.E; et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Intensive Care Medicine 2016, 43, 304–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).