Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Reagent and Materials

2.2. Equipment

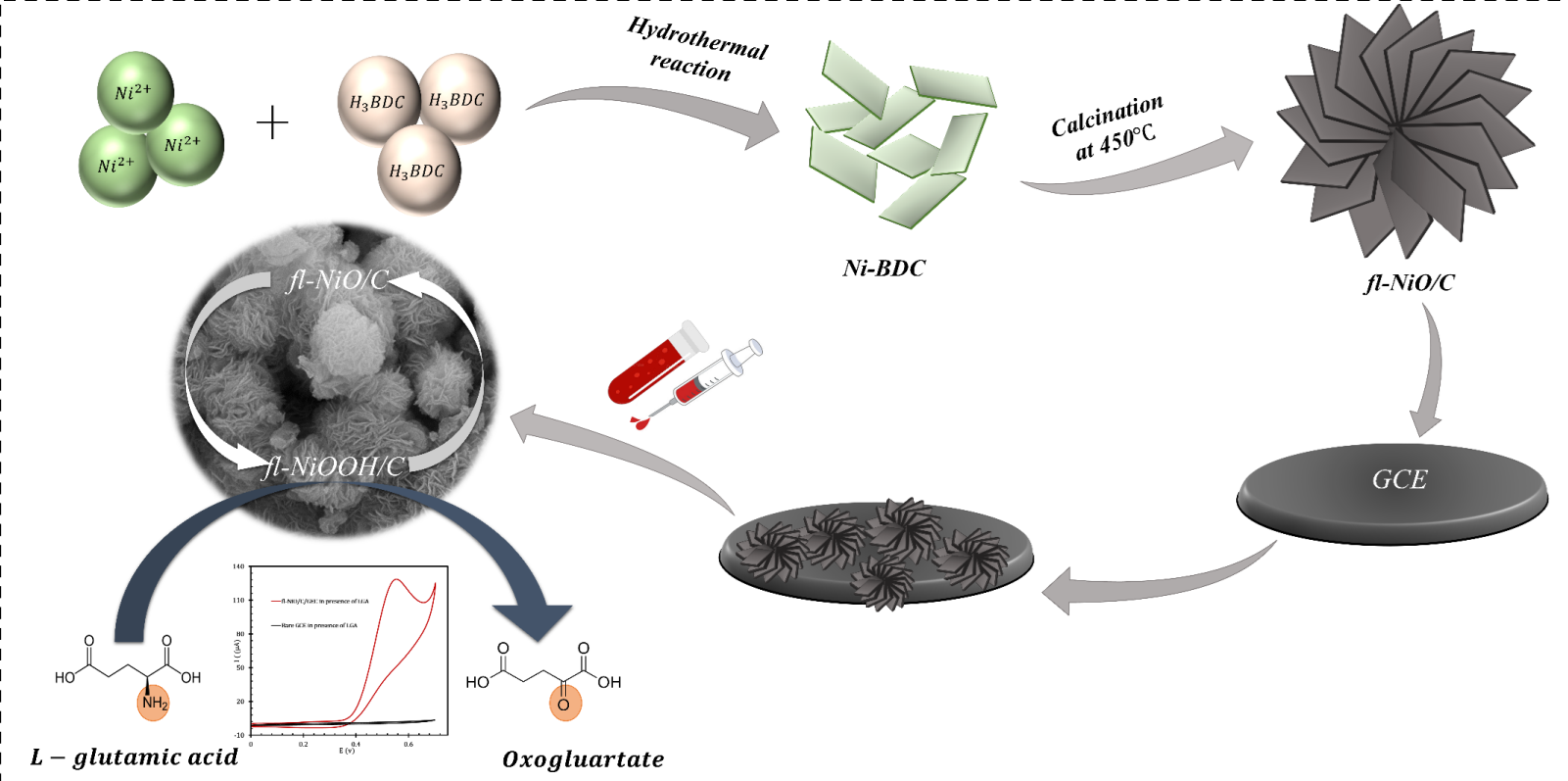

2.3. Preparation of Ni-BDC MOF as a Precursor

2.4. Preparation of fl-NiO/C Microsphere

2.5. Preparation of fl-NiO/C/GCE

3. Results and Discussion

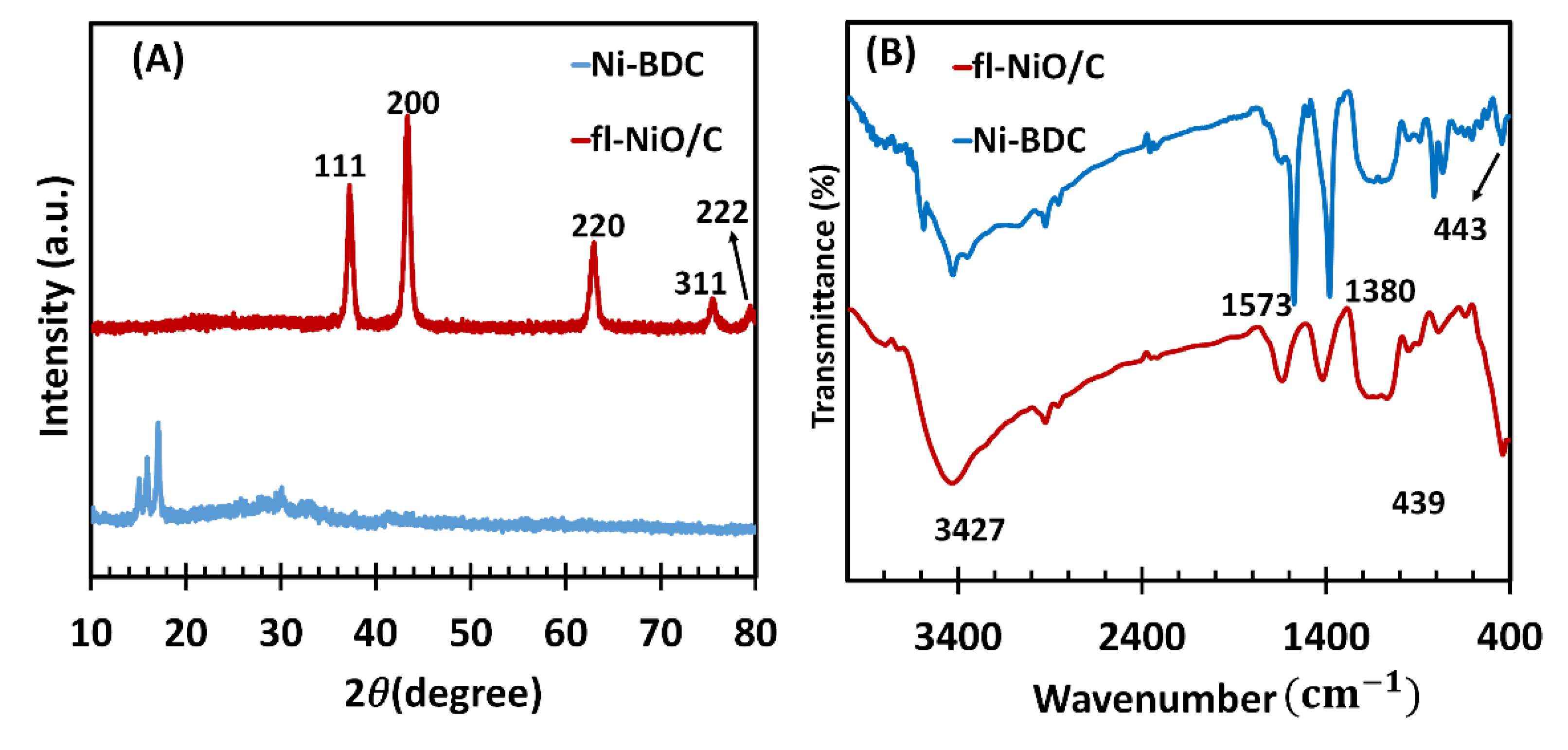

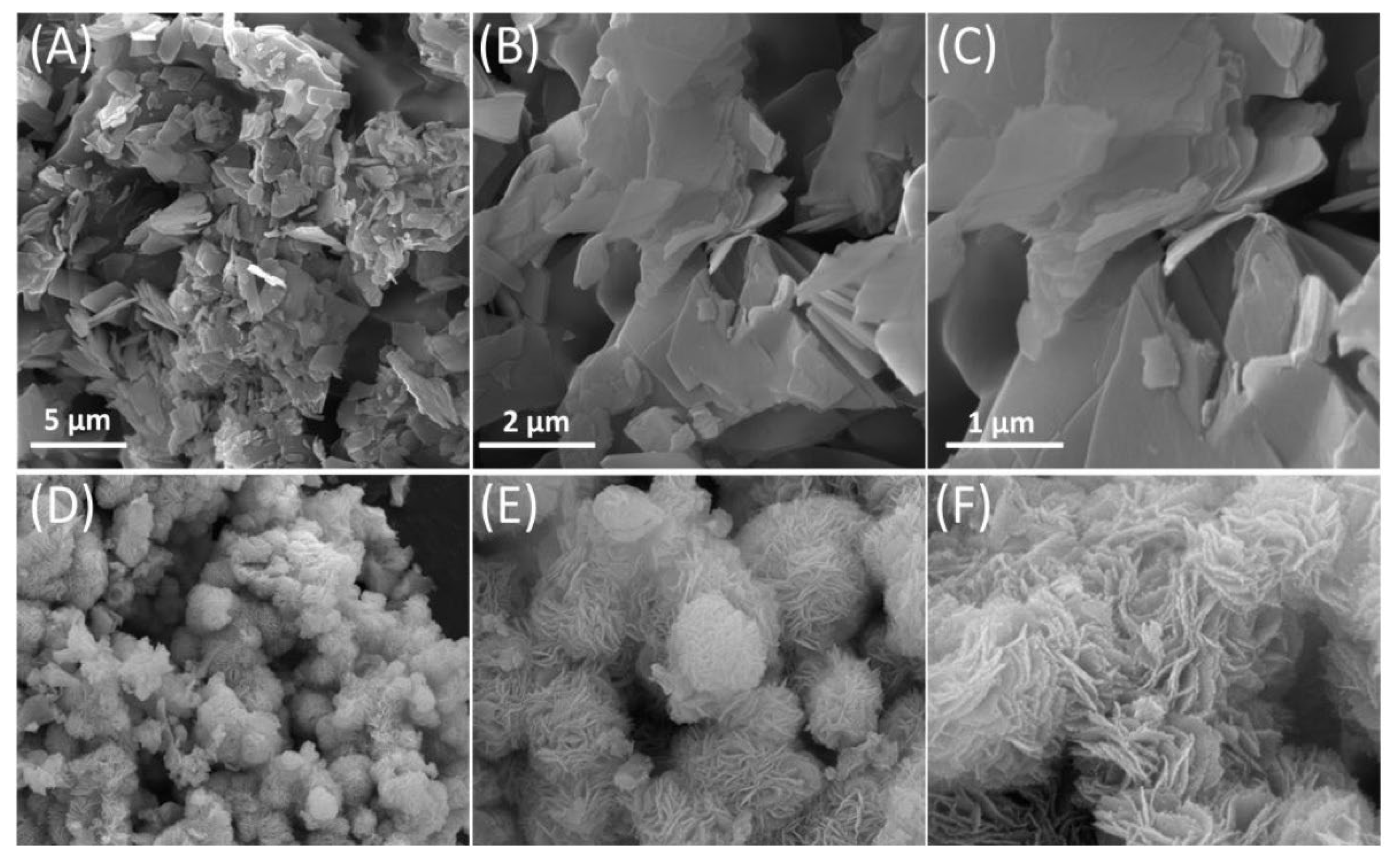

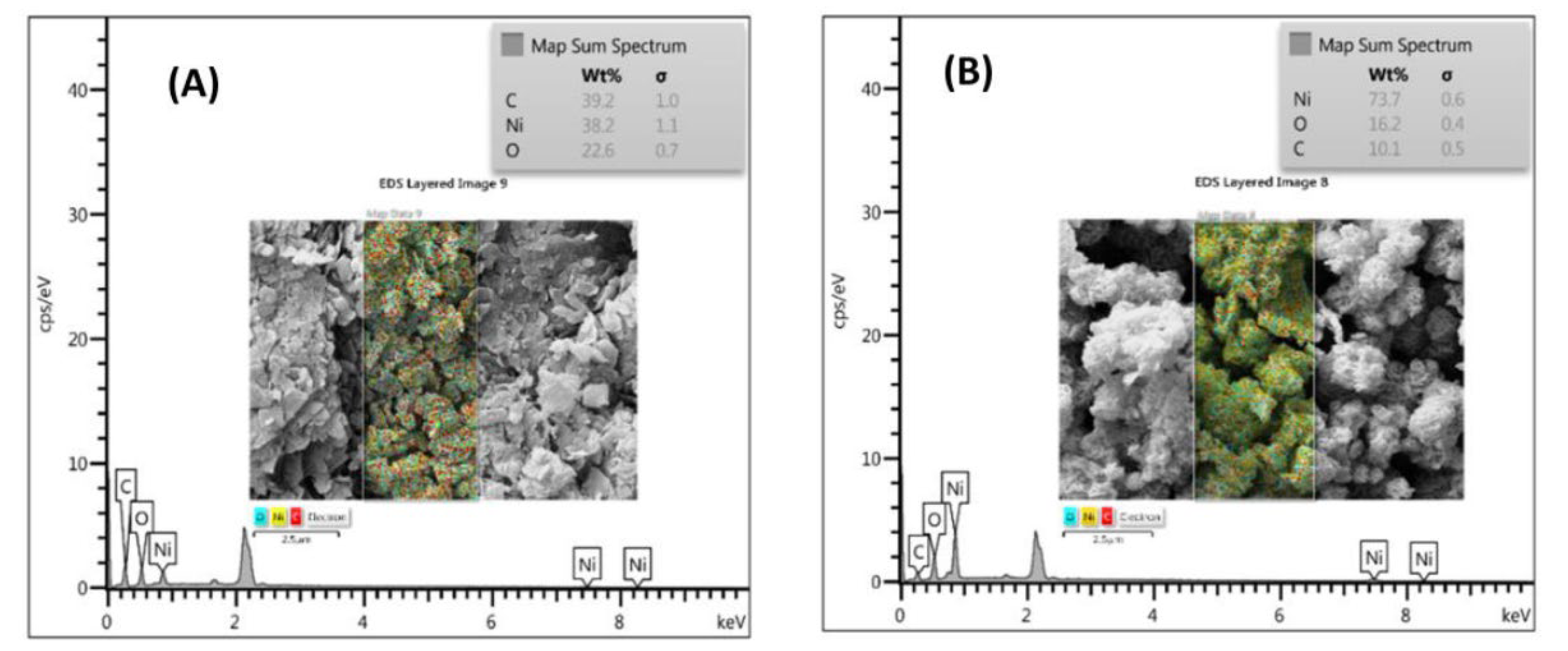

3.1. Material Characterization

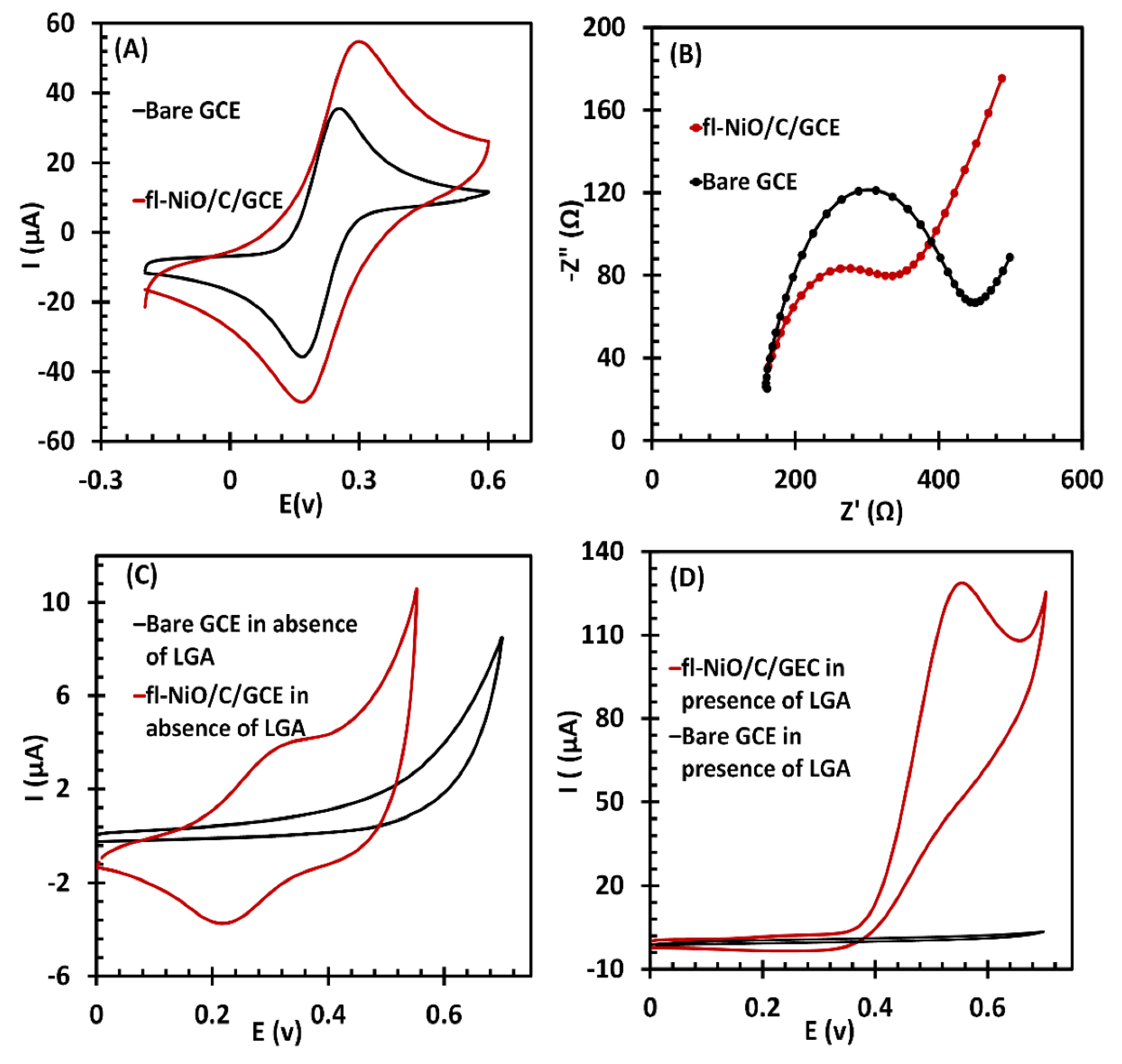

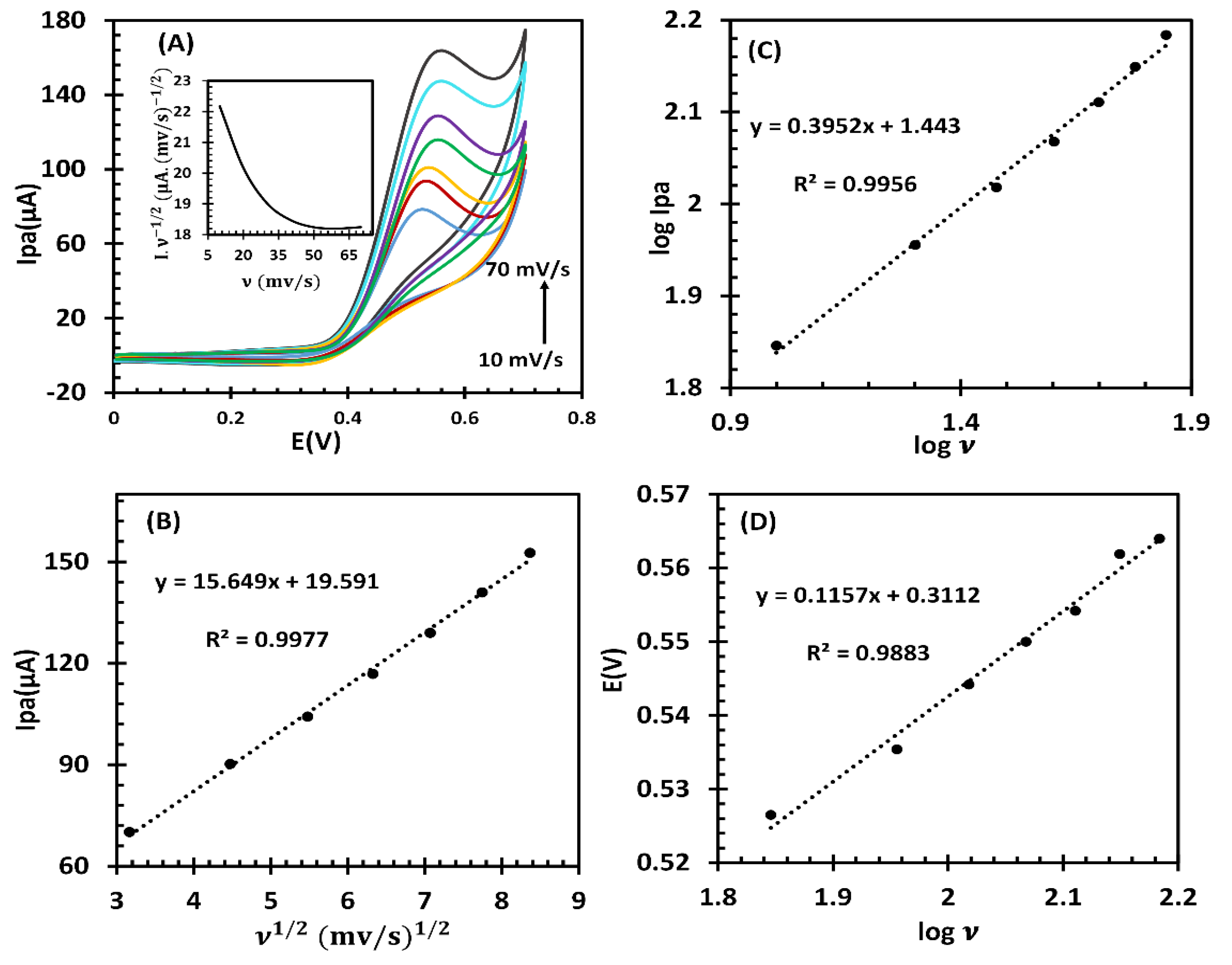

3.2. Electrochemical Behaviour of the fl-NiO/C/GCE

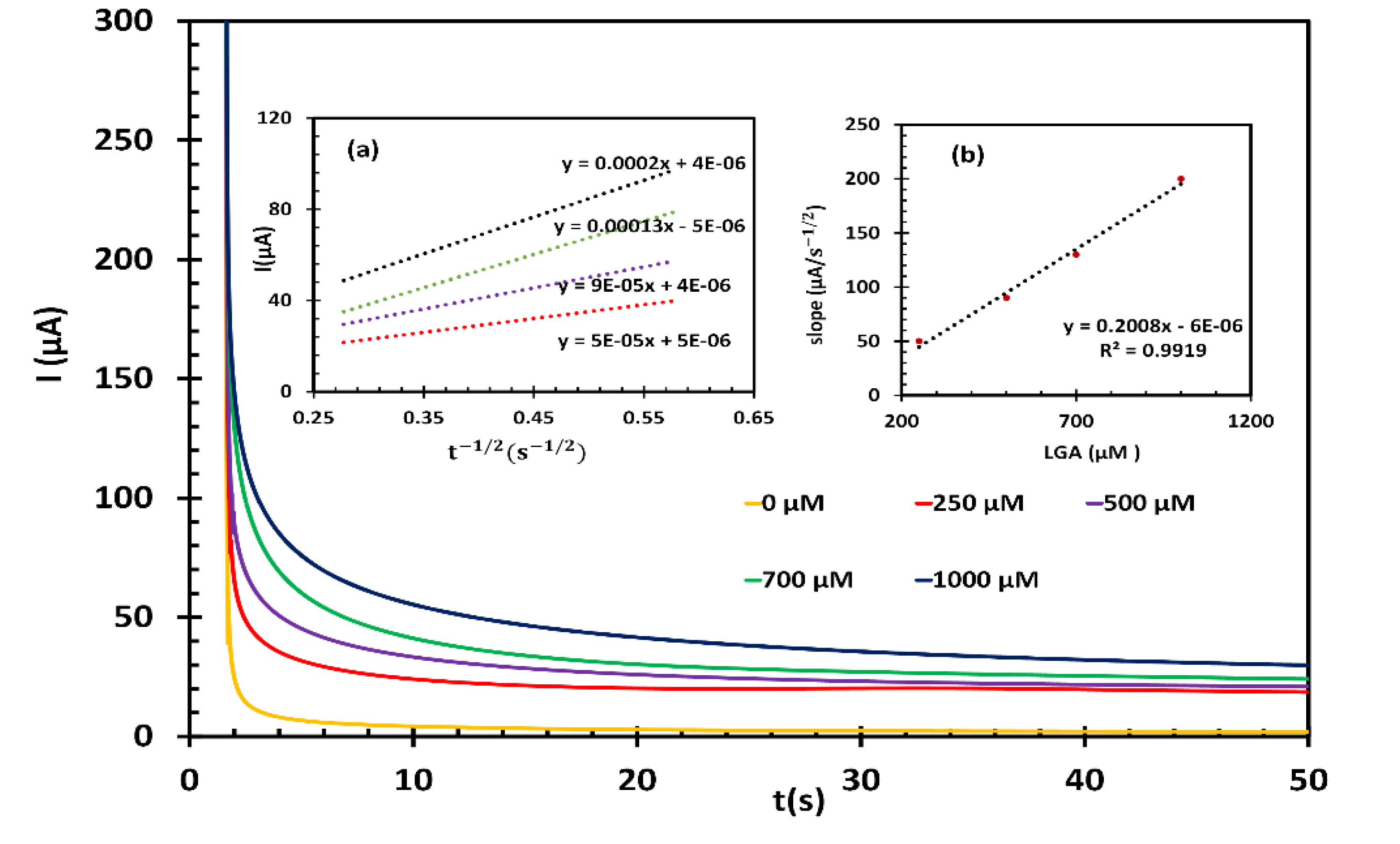

3.3. Chronoamperometric Measurements

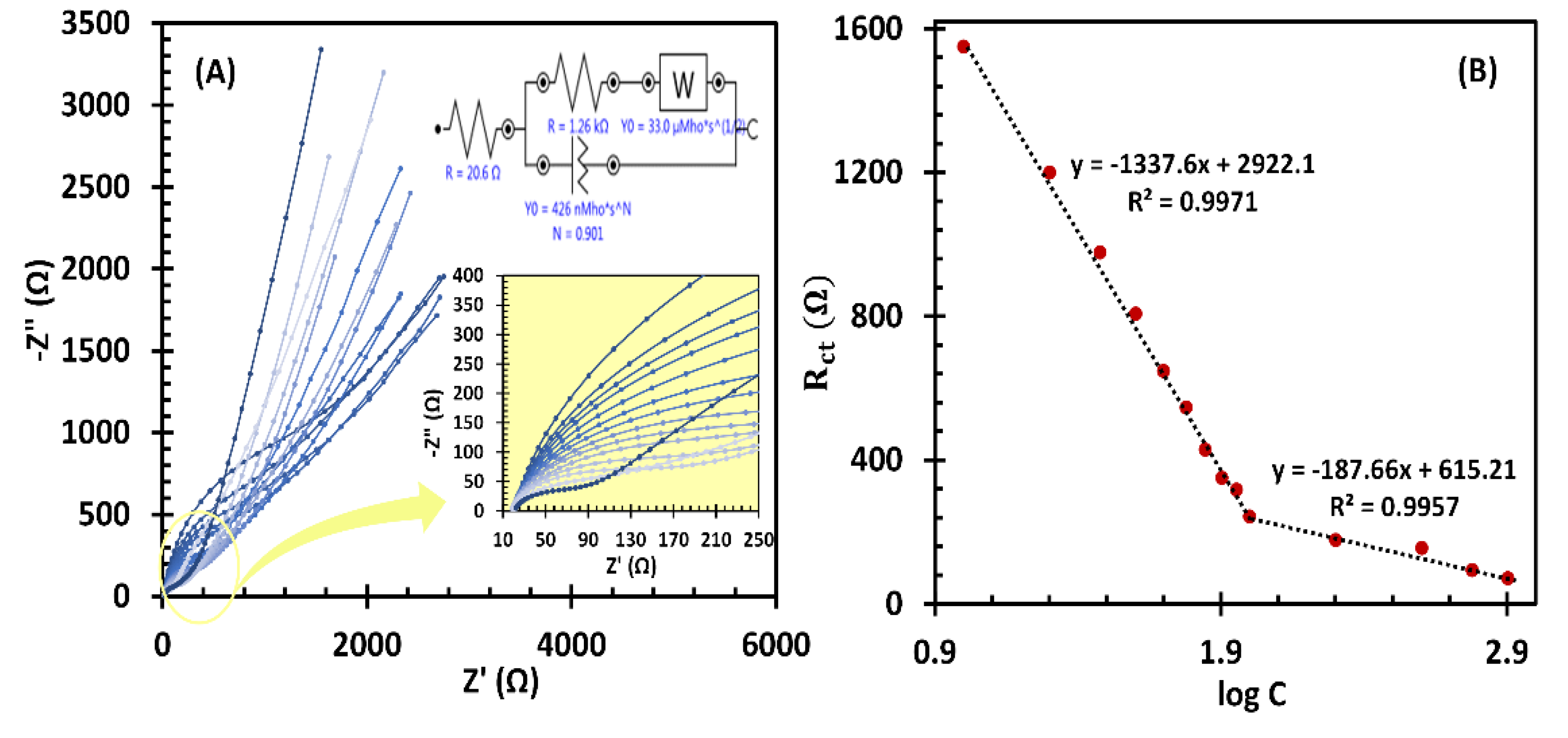

3.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) Measurements

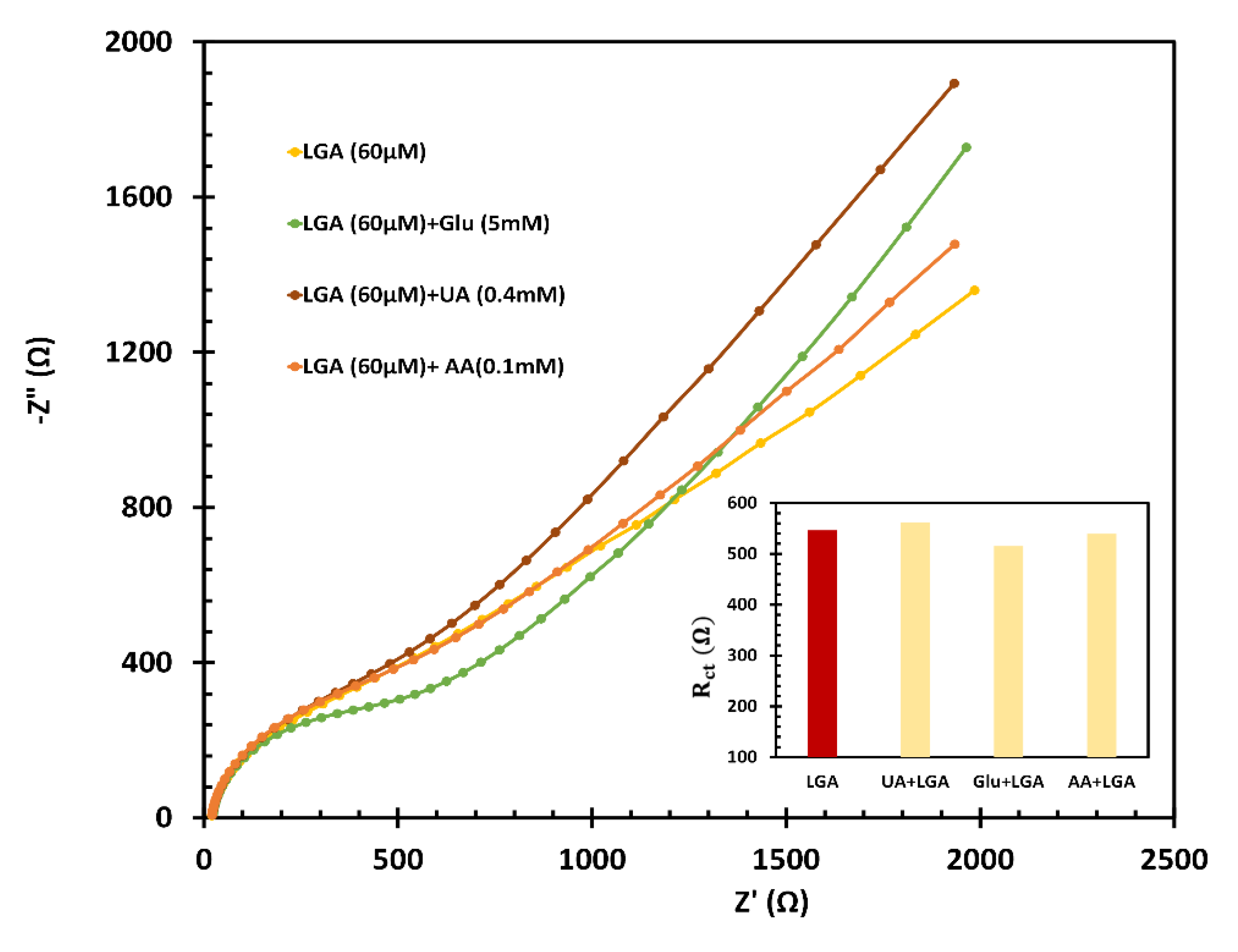

3.5. Interference Study of Biosensor

3.6. Stability, Reproducibility and Repeatability

3.7. Utilizing the Sensor for Real Sample Analysis

4. Conclusions

Data availability

Supplementary Materials

Author contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schultz, J.; Uddin, Z.; Singh, G.; Howlader, M.M. Glutamate Sensing in Biofluids: Recent Advances and Research Challenges of Electrochemical Sensors. Analyst. 2020, 145, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, F.; Sobrino, T.; Ramos-Cabrer, P.; Argibay, B.; Agulla, J.; Pérez-Mato, M.; Rodríguez-González, R.; Brea, D.; Castillo, J. Neuroprotection by Glutamate Oxaloacetate Transaminase in Ischemic Stroke: An Experimental Study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2011, 31, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, H.S.; Dodd, P.R. Glutamate–Glutamine Cycling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurochem. Int. 2007, 50, 1052–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.H.; Hazell, A.S. Excitotoxic Mechanisms and the Role of Astrocytic Glutamate Transporters in Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurochem. Int. 2006, 48, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, D.W.; Austin, M.C.; Pierri, J.N.; Sampson, A.R.; Lewis, D.A. Decreased Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase67 Messenger RNA Expression in a Subset of Prefrontal Cortical γ-Aminobutyric Acid Neurons in Subjects With Schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2000, 57, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liimatainen, S.; Peltola, M.; Sabater, L.; Fallah, M.; Kharazmi, E.; Haapala, A.M.; Dastidar, P.; Knip, M.; Saiz, A.; Peltola, J. Clinical Significance of Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase Antibodies in Patients with Epilepsy. Epilepsia 2010, 51, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, I.R.; Kostic, M.; Ljubisavljevic, S. The Role of Glutamate and Its Receptors in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neural Transm. 2014, 121, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bartolomeis, A.; Buonaguro, E.F.; Iasevoli, F. Serotonin–Glutamate and Serotonin–Dopamine Reciprocal Interactions as Putative Molecular Targets for Novel Antipsychotic Treatments: From Receptor Heterodimers to Postsynaptic Scaffolding and Effector Proteins. Psychopharmacol. 2012 2251 2012, 225, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadpour, F.; Mazloum-Ardakani, M. Electro-Assisted Self-Assembly of Mesoporous Silica Thin Films: Application to Electrochemical Sensing of Glutathione in the Presence of Copper. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2022, 26, 2329–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadpour, F.; Zhang, X.W.; Mazloum-Ardakani, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Majdi, S.; Ewing, A.G. Vesicular Release Dynamics Are Altered by the Interaction between the Chemical Cargo and Vesicle Membrane Lipids. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 10273–10278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinap, S.; Hajeb, P. Glutamate. Its Applications in Food and Contribution to Health. Appetite 2010, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monge-Acuña, A.A.; Fornaguera-Trías, J. A High Performance Liquid Chromatography Method with Electrochemical Detection of Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid, Glutamate and Glutamine in Rat Brain Homogenates. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 183, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, J.; Zhou, M. Microplate-Based Fluorometric Methods for the Enzymatic Determination of l-Glutamate: Application in Measuring l-Glutamate in Food Samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 1999, 402, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, K.; Voehringer, P.; Ferger, B. Rapid Analysis of GABA and Glutamate in Microdialysis Samples Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography and Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Neurosci. Methods 2009, 182, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lada, M.W.; Vickroy, T.W.; Kennedy, R.T. High Temporal Resolution Monitoring of Glutamate and Aspartate in Vivo Using Microdialysis On-Line with Capillary Electrophoresis with Laser-Induced Fluorescence Detection. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 4560–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Awual, M.R. Non-Enzymatic Simultaneous Detection of l -Glutamic Acid and Uric Acid Using Mesoporous Co 3 O 4 Nanosheets. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 80511–80521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadlaghani, A.; Farzaneh, M.; Kinser, D.; Reid, R.C. Direct Electrochemical Detection of Glutamate, Acetylcholine, Choline, and Adenosine Using Non-Enzymatic Electrodes. Sensors 2019, Vol. 19, Page 447 2019, 19, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoggin, J.L.; Tan, C.; Nguyen, N.H.; Kansakar, U.; Madadi, M.; Siddiqui, S.; Arumugam, P.U.; DeCoster, M.A.; Murray, T.A. An Enzyme-Based Electrochemical Biosensor Probe with Sensitivity to Detect Astrocytic versus Glioma Uptake of Glutamate in Real Time in Vitro. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 126, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, B.; Pundir, C.S. An Amperometric Glutamate Biosensor Based on Immobilization of Glutamate Oxidase onto Carboxylated Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes/Gold Nanoparticles/Chitosan Composite Film Modified Au Electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 47, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatkina, O.V.; Soldatkin, O.O.; Kasap, B.O.; Kucherenko, D.Y.; Kucherenko, I.S.; Kurc, B.A.; Dzyadevych, S.V. A Novel Amperometric Glutamate Biosensor Based on Glutamate Oxidase Adsorbed on Silicalite. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaivosoja, E.; Tujunen, N.; Jokinen, V.; Protopopova, V.; Heinilehto, S.; Koskinen, J.; Laurila, T. Glutamate Detection by Amino Functionalized Tetrahedral Amorphous Carbon Surfaces. Talanta 2015, 141, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özel, R.E.; Ispas, C.; Ganesana, M.; Leiter, J.C.; Andreescu, S. Glutamate Oxidase Biosensor Based on Mixed Ceria and Titania Nanoparticles for the Detection of Glutamate in Hypoxic Environments. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2014, 52, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, M.; Hasan, M.; Mathewson, A.; Razeeb, K.M. Disposable Sensor Based on Enzyme-Free Ni Nanowire Array Electrode to Detect Glutamate. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 40, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamal, M.; Chakrabarty, S.; Shao, H.; McNulty, D.; Yousuf, M.A.; Furukawa, H.; Khosla, A.; Razeeb, K.M. A Non Enzymatic Glutamate Sensor Based on Nickel Oxide Nanoparticle. Microsyst. Technol. 2018, 24, 4217–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Asiri, A.M.; Awual, M.R. Non-Enzymatic Simultaneous Detection of l -Glutamic Acid and Uric Acid Using Mesoporous Co 3 O 4 Nanosheets. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 80511–80521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, Z.; Mazloum-Ardakani, M.; Asadpour, F.; Yavari, M. Highly Efficient Enzyme-Free Glutamate Sensors Using Porous Network Metal–Organic Framework-Ni-NiO-Ni-Carbon Nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 59246–59257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Yang, T.; Lei, D.; Zhang, G.; Mei, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Q.; Wang, T. Preparation of 3D Flower-like NiO Hierarchical Architectures and Their Electrochemical Properties in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 90, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Yang, H.; Cheng, Y.; Lin, Y. MOFs Derived Flower-like Nickel and Carbon Composites with Controllable Structure toward Efficient Microwave Absorption. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 154, 106772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Sun, W.; Lv, L.P.; Kong, S.; Wang, Y. Microwave-Assisted Morphology Evolution of Fe-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Derived Fe2O3 Nanostructures for Li-Ion Storage. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4198–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumilar, G.; Kaneti, Y.V.; Henzie, J.; Chatterjee, S.; Na, J.; Yuliarto, B.; Nugraha, N.; Patah, A.; Bhaumik, A.; Yamauchi, Y. General Synthesis of Hierarchical Sheet/Plate-like M-BDC (M = Cu, Mn, Ni, and Zr) Metal–Organic Frameworks for Electrochemical Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensing. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 3644–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, C.; Xiong, P.; Li, Y.; Wei, M. Zn-Doped Ni-MOF Material with a High Supercapacitive Performance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 19005–19010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Jha, R.; Ravikant, C. Investigating the Structural, Electrochemical, and Optical Properties of p-Type Spherical Nickel Oxide (NiO) Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2020, 144, 109488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, V.; Senthil Kumar, S.M.; Thangamuthu, R. Synthesis and Characterization of NiO Nanoplatelet and Its Application in Electrochemical Sensing of Sulphite. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 744, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, A.J.; Faulkner, L.R.; Swain, E.; Robey, C. Fundamentals and Applications; ISBN 0471043729.

- Sharp, M.; Petersson, M.; Edström, K. A Comparison of the Charge Transfer Kinetics between Platinum and Ferrocene in Solution and in the Surface Attached State. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1980, 109, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trafela, Š.; Zavašnik, J.; Šturm, S.; Rožman, K.Ž. Formation of a Ni(OH)2/NiOOH Active Redox Couple on Nickel Nanowires for Formaldehyde Detection in Alkaline Media. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 309, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Hou, H.; Wu, Y.; Yu, W.; Ji, X.; Shao, L. Nickel Nanoparticles Supported on Nitrogen-Doped Honeycomb-like Carbon Frameworks for Effective Methanol Oxidation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14152–14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youcef, M.; Hamza, B.; Nora, H.; Walid, B.; Salima, M.; Ahmed, B.; Malika, F.; Marc, S.; Christian, B.; Wassila, D.; et al. A Novel Green Synthesized NiO Nanoparticles Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode for Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensing. Microchem. J. 2022, 178, 107332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloum-Ardakani, M.; Amin-Sadrabadi, E.; Khoshroo, A. Enhanced Activity for Non-Enzymatic Glucose Oxidation on Nickel Nanostructure Supported on PEDOT:PSS. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 775, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.; Pletcher, D.; Smith, C. The Oxidation of Alcohols at a Nickel Anode in Alkaline T-Butanol/Water Mixtures. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1977, 124, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.; Chandran, M.; Dhanusuraman, R. A Comprehensive Review on the Electrochemical Parameters and Recent Material Development of Electrochemical Water Splitting Electrocatalysts. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 3843–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.A.; De Vries, M.G.; Cremers, T.I.F.H.; Westerink, B.H.C. The Role of Surface Availability in Membrane-Induced Selectivity for Amperometric Enzyme-Based Biosensors. Sensors Actuators B Chem. 2016, 223, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, A.L.; Carballo, R. Impedimetric Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensor Based on Nickel Hydroxide Thin Film onto Gold Electrode. Sensors Actuators, B Chem. 2016, 228, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, A.; Hatefi-Mehrjardi, A.; Karimi, M.A.; Mohadesi, A. Impedimetric Glucose Biosensing Based on Drop-Cast of Porous Graphene, Nafion, Ferrocene, and Glucose Oxidase Biocomposite Optimized by Central Composite Design. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2022, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T.T.C.; Yao, J.; Chan, W.C. Selective Enzyme Immobilization on Arrayed Microelectrodes for the Application of Sensing Neurotransmitters. Biochem. Eng. J. 2013, 78, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, R.; Gogoi, S.; Barua, S.; Sankar Dutta, H.; Bordoloi, M.; Khan, R. Electrochemical Detection of Monosodium Glutamate in Foodstuffs Based on Au@MoS2/Chitosan Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode. Food Chem. 2019, 276, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M.; Chakrabarty, S.; Shao, H.; McNulty, D.; Yousuf, M.A.; Furukawa, H.; Khosla, A.; Razeeb, K.M. A Non Enzymatic Glutamate Sensor Based on Nickel Oxide Nanoparticle. Microsyst. Technol. 2018, 24, 4217–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrodes | Detection method | Linearity range (mM) |

Sensitivity (μA mM-1 cm-2) |

LOD2 (μM) |

Enzyme | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NiNAE1 |

I-V |

0.50 – 8.00 |

65.0 |

135.00 |

no enzyme |

[23] |

|

NiO/GCE |

amperometric |

1.00 – 8.00 |

11.00 |

272.00 |

no enzyme |

[24] |

|

Au@MoS2/Chitosan/ GCE |

DPV3 |

0.05 μM – 0.20 |

--- |

0.03 |

no enzyme |

[46] |

|

PPy4/Nafion/Chitosan/ GlutOx5 |

amperometric |

0.01−0.88 |

38 |

2.5 |

GlutOx |

[45] |

|

GlutOx/cMWCNT6/AuNP/Chitosan |

CV |

0.005 − 0.5 |

155 |

1.6 |

GlutOx |

[19] |

|

GlutOx/APTES7/ ta-C/P8 |

amperometric |

0.01 – 0.5 |

2.9 |

10.0 |

GlutOx |

[21] |

|

fl-NiO/C/GCE |

EIS |

0.01 – 0.80 |

486.98 |

1.28 |

no enzyme |

This work |

| Blood plasma sample | Method | Found by This sensor (μM) | Found by HPLC (μM) | Recovery% | texperimental |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | EIS | 89.1 | 90.1 | 98.91 | 1.21 |

| II | EIS | 46.0 | 45.1 | 102.13 | 1.27 |

| III | EIS | 30.9 | 31.3 | 99.55 | 1.83 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).