1. Introduction

Neurotransmitters play a pivotal role in a large variety of neurophysiological functions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. For example,

dopamine (DA) is involved in several neurophysiological processes such as motor control, reward, motivation and cognitive function [

5,

6,

7,

8] whereas

serotonin (

5-Hydroxytryptamine (

5-HT)) plays a significant role in several neural signal processes such as memory, long-term potentiation as well as cardiovascular and gastrointestinal functions [

9,

10,

11,

12]. The disruption of the secretion and uptake of

DA and

5-HT at synapses is considered as causative factor towards several psychiatric and neurological disorders [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Further, while

5-HT is a major target for pharmacological treatment, its involvements in mood disorders as well as neuroplasticity is still of significant research and clinical interest [

16].

Glutamate and

lactate, two closely related neurotransmitters, are involved in the metabolic pathways of the central nervous system (CNS), with

glutamate being the most extensive free-standing amino acid in the brain with its increased presence identified as a potential cause for significant neuronal cell damage or epileptic seizure [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Given their significant roles, the understanding of electrochemical neural signaling enabled by neurotransmitters could, therefore, help develop a more complete picture of brain functions and better insight into some key neurological disorders [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Further, integration of neurochemical sensing with electrophysiological recording and stimulation is of fundamental importance in elucidating the relationship between electrical and electrochemical signaling and their role in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders [

27,

28,

29]. This increased understanding could also inform the design of novel closed-loop treatment platforms enabled by neurochemical feedback [

30,

31,

32]. Therefore, there is a continuing research need for developing new electrode technology for detection of these neurotransmitters

in vivo.

From a detection point of view, neurotransmitters can be broadly classified into two general groups, i.e., electroactive and non-electroactive. For example,

dopamine, serotonin, and adenosine are electroactive species that can electrochemically oxidize forming

quinone groups [

33,

34,

35]. Techniques such as fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) can then be used for direct detection of such electroactive species through their respective signature redox peaks. On the other hand, neurotransmitters such as

glutamate,

lactate,

acetylcholine, and

gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) are non-electroactive and are, therefore, inherently unsuitable for direct detection through voltammetry techniques. For this and several other reasons such as no requirement for specialized equipment and post-processing of data, most works reported in the literature in the detection of such non-electroactive neurotransmitters had used amperometric techniques [

36,

37]. However, the major drawback of amperometric technique is its non-selectivity, which – in the context of simultaneous detection of multiple neurotransmitters – makes it impractical for such needs. This has given rise to the exploration of FSCV for detection of

glutamate along with other neurotransmitters such as

dopamine. In one such reported work, GlutOx-chitosan hydrogels were electrodeposited on carbon-fiber microelectrodes (CFM) where enzymatic generation of electroactive hydrogen peroxide helped detect

glutamate [

38]. However, carbon-fiber microelectrodes have their own shortcomings such as lack of mechanical sturdiness and inconsistent composition and surface adsorption properties that have in turn limited their repeatability and reliability [

39].

To address these gaps, recent works have introduced a lithographically patternable array of carbon-based microelectrodes that have shown promises in neurotransmitter detections. Among these, glassy carbon (GC) has emerged as a compelling material of choice for microelectrodes used in the detection of electroactive neurotransmitters, such as

DA and

5-HT at concentrations as low as 10 nM [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. Further, due to its surface that is rich with electrochemically active functional groups, good adsorption characteristics, and its antifouling properties, GC has been demonstrated to be useful for not only electrophysiological recording and stimulation, but also for multi-site simultaneous detection of the electroactive neurotransmitters,

DA and

5-HT in a stable and repeatable manner [

45,

46]. However, for the indirect detection of non-electroactive neurotransmitters such as

glutamate,

lactate, and the like, surface functionalization of the microelectrodes is required. One such possibility is the immobilization of

glutamate oxidase (

GluOx) enzyme on the surface of microelectrodes to enable catalysis of the chemical reaction between

L-glutamate, oxygen, and water to produce the electroactive byproduct

hydrogen peroxide that is detectable through voltammetry (

L-glutamate + oxygen + water → oxoglutarate + ammonia + hydrogen peroxide). In lieu of

GluOx,

glutamate dehydrogenase could also be used for detection of

glutamate [

47,

48,

49]. In this study, we extend the application of GC to detection of non-electroactive neurotransmitters and present the immobilization of

GluOx on lithographically patterned GC microelectrodes for establishing the indirect electrochemical

in vitro detection of

glutamate. The same platform could be used for the detection of other neurotransmitters through the appropriate surface functionalization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microfabrication of Microelectrodes

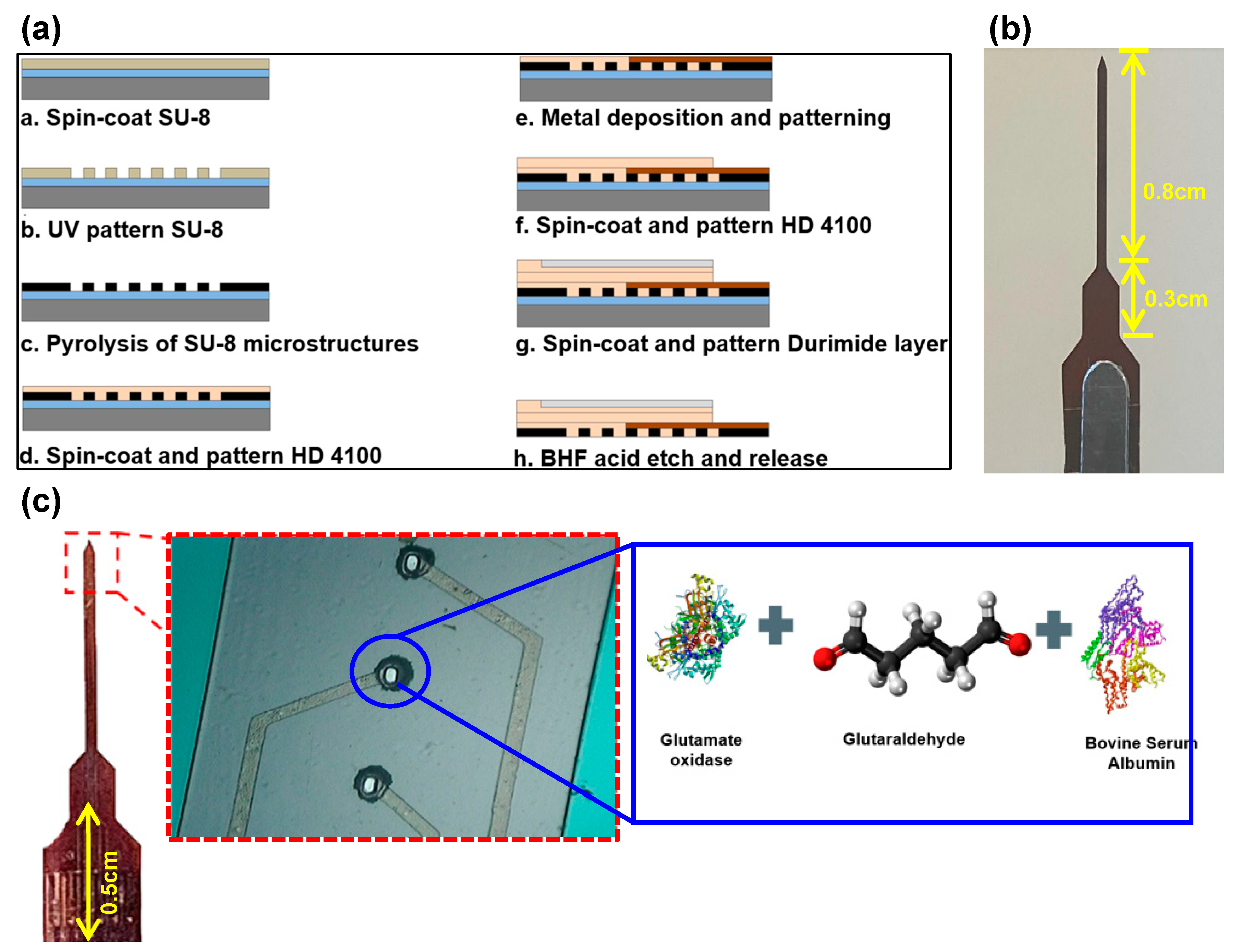

A 1.6 cm long penetrating neural probe with four GC microelectrodes of 30 μm x 60 μm size was microfabricated. As described elsewhere, the microfabrication process for the probe shown in

Figure 1a involved spin-coating of SU-8 negative photoresist (Microchem, MA) on a silicon wafer (with 0.5 μm thick oxide layer) at 1200 rpm for 55 s and soft-baking at 65°C for 10 min and 95°C for 20 min followed by UV exposure at ~400 mJ/cm

2 [

50]. This was followed by a post-exposure bake at 65°C for 1 min and 95°C for 5 min, development of SU-8 for 3–5 min and curing at 150°C for 30 min. Pyrolysis was done at 1000°C in an inert N

2 environment following protocols described elsewhere [

50,

51,

52]. Subsequently, 5 µm layer of photo-patternable polyimide (HD 4100) (HD Microsystems, DE, USA) was spin-coated on top of the GC microelectrodes at 2500 rpm for 45 s, soft baked at 90°C for 3 min and at 120°C for 3 min, then cooled down to room temperature, and patterned through UV exposure at ~400 mJ/cm

2. Then, the polyimide layer was partially cured at 300°C for 60 min under N

2 environment. Following, Pt metal traces with Ti adhesion layer were patterned using a metal lift-off process. For electrical insulation, an additional 6 µm of polyimide HD 4100 was spin-coated (300 rpm), patterned (400 mJ/cm

2), and cured (350°C for 90 min) under N

2 environment. An additional 30 µm thick layer of polyimide (Durimide 7520, Fuji Film, Japan) was spin-coated (800 rpm, 45 s) and then patterned (400 mJ/cm

2) on top of the insulation layer to reinforce the penetrating portion of the device (

Figure 1b). Once the probes were released from the carrier substrate using a BHF bath, the GC microelectrodes were plasma etched (120W for 45 s) and then functionalized through drop-casting of a thin coat of an enzyme mix.

2.2. Functionalization of Microelectrodes

As shown in

Figure 1c, the surface functionalization process consisted of preparing an enzyme immobilization matrix made of

glutamate oxidase (

GluOx), a catalytic enzyme,

glutaraldehyde (a reagent from the aldehyde family that allows a rapid ionic immobilization of the enzyme on the GC microelectrode surface), and

bovine serum albumin (

BSA) which provides stability to the enzyme and the reagent mixture.

L-glutamic acid (≥99%),

L-glutamate oxidase (from S

treptomyces sp.), and

bovine serum albumin (≥ 96%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). In addition,

glutaraldehyde (25% solution distillation purified) was purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (PA, USA). Before mixing,

GluOx,

glutaraldehyde, and

BSA were brought to room temperature. Then, the

GluOx enzyme was dissolved in 1 μL of DI water. Separately, 0.01g of

BSA was placed in a microcentrifuge tube and 985 μL of DI water added to it. The mix was then vortexed at low rpm. Subsequently, 5 μL of

glutaraldehyde was added. This mixture of

BSA/glutaraldehyde was then transferred into a 500 μL microcentrifuge tube, 1 μL of

GluOx was added to it and it was vortexed again at slow rpm. This was followed by dry storage of the immobilization matrix at room temperature to ensure a successful crosslinking between the enzyme,

glutaraldehyde and

BSA. Finally, 10 μL of the immobilization matrix was then extracted and pipetted for drop-casting of a thin coat over the surface of the GC microelectrodes.

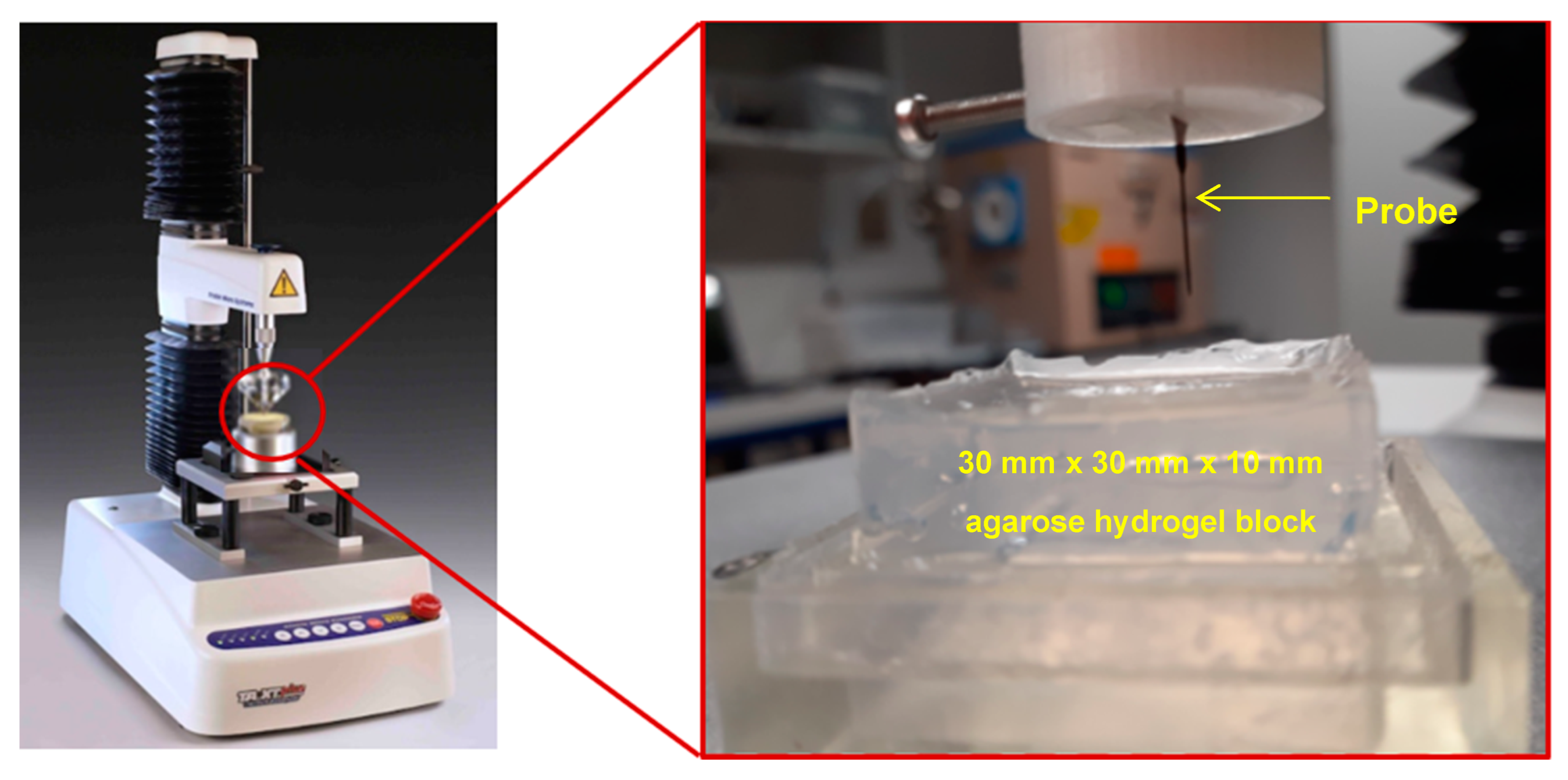

2.3. Mechanical Characterization

The mechanical stability of the probes and their penetration ability were tested using a TA.XT plusC Texture Analyzer (TA) (Stable Micro Systems Products). To determine an appropriate agarose gel concentration that models the modulus of brain tissue, a compression calibration test was first carried out as explained in the accompanying supplementary document (Section S1) [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Once the relevant concentration of agarose gel was determined, penetration tests of the

in vitro model medium were carried out using the GC probes presented in

Figure 1. For this, a holder for the GC probe was designed, 3D printed and mounted on the probe of the TA (

Figure 2). The agarose gel block shown in

Figure 2 had a length of 30 mm, width of 30 mm, thickness of 10 mm, and area of 900 mm

2. The same speed of loading of 2 mm/s was used for the penetration test as well, with a 0.5 kg weight load cell.

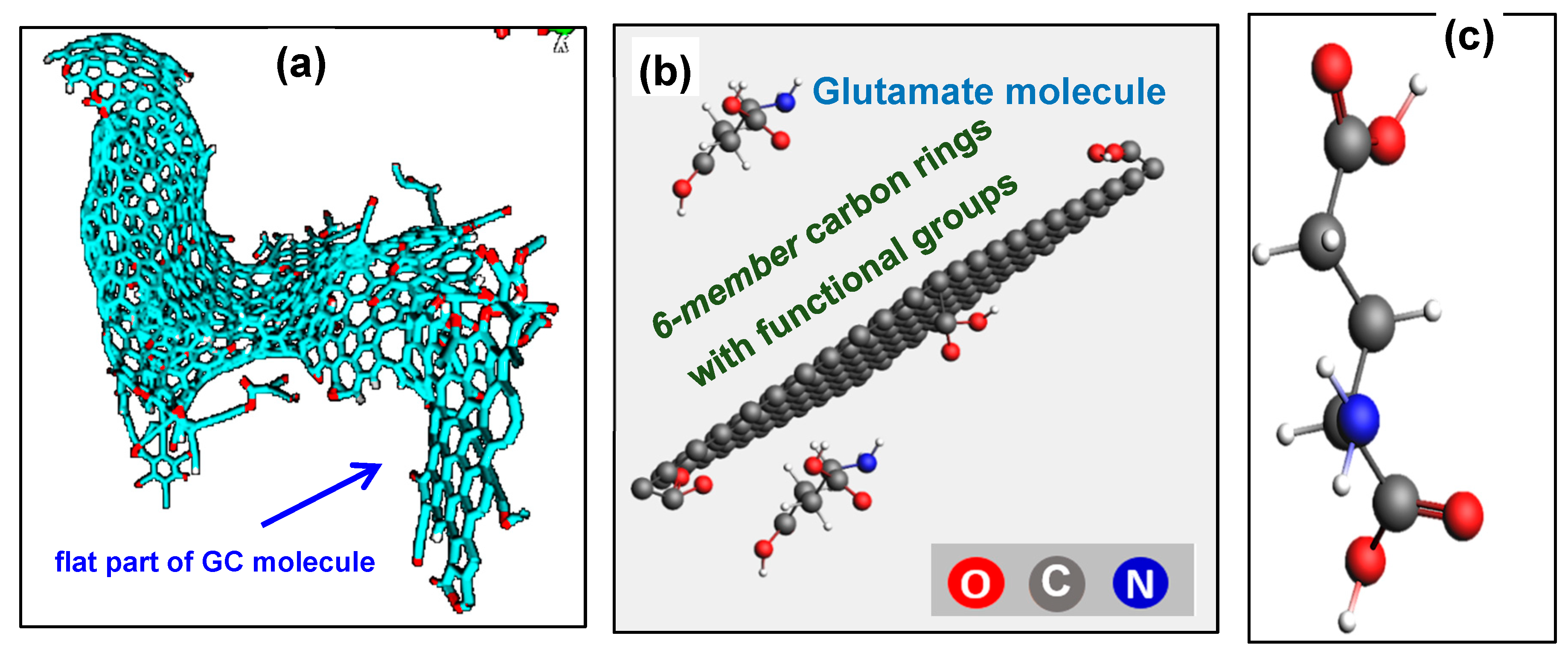

2.4. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Modeling

To understand the interaction between

glutamate and the immobilized enzyme mix with the surface of GC microelectrodes and investigate if covalent bonds were formed, a chemical simulation was performed using molecular dynamics (MD) modeling software. We used ReaxFF software from SCM-ReaxFF, a tool for modeling chemical reactions with a reactive force field [

57]. Briefly, in this reactive force field formulation of ReaxFF, a pre-determined potential energy function allows for the calculation of the force experienced by any atom, given the positions of all its surrounding atoms at a given time step. The forces acting on each atom at each time step are computed using molecular mechanics force fields. The position and velocity of each atom and energy contributions to the potential are then updated using Newton’s Equations of Motion. The total force consists of the energy associated with forming bonds between atoms, the valence angle strain and torsional angle strain, and electrostatic and dispersive contributions between all atoms. The starting model of the molecular structure of GC was the nanostructure that was reported in our recent work consisting of a flat graphitic domain with graphene-like

6-membered carbon rings and a cage-like component [

58]. For simplicity, the simulation cell used here (

25 Å x 25 Å x 25 Å) with a density of 1.19 g/mL models only the flat component consisting of 144 graphene-like

6-membered carbon rings as shown in

Figure 3. Four functional groups (

carbonyl,

carboxyl, hydroxyl, and

epoxy) were considered attached to this carbon molecule. The

5- and

7-membered carbon rings that form the periphery of the cagey component along with 6

-membered carbon rings are expected to have similar chemical interactions and are not included in the model to save computational expenses.

With regard to modeling

GluOx which is a relatively large protein structure, the significantly high computational resources required could be a limiting factor. However, since all proteins and amino acids contain both

C- and

N-terminal domains, the amino acid

glutamate can be taken as a smaller representation of the large molecule of

GluOx, thereby achieving a more efficient way of predicting chemical interactions between the key amino acid components and the carbon surface. This is further supported by the fact that

glutamate is one of seven amino acids present in the active site of

GluOx, suggesting that it plays an essential role in the production of

H2O2. A full list of key amino acids that are present in the active site, along with their functional groups, are listed in Table S1 for completeness. With this reasoning,

glutamate (C

5H

9NO

4) molecule was added to the simulation cell. Two temperature cases (27

oC and 37

oC) and two voltage bias cases (0 V and 0.4 V) were considered. All models were analyzed using a temperature damping constant of

100 fs and a pressure damping constant of 500 fs with constant volume and temperature conditions through the constant temperature and volume (NVT) Berendsen thermostat [

59,

60].

2.5. FTIR Spectroscopy

To determine the presence of functional groups and, by correlation, the strength of the bond between the GC microelectrode surface and the immobilized functionalization mix, FTIR-ATR spectroscopy was carried out using a Nicolet iS50 FTIR Spectrometer equipped with a Smart iTR diamond ATR cell (Thermo Scientific, Court Vernon Hills, IL, USA). Three types of samples were analyzed: a bare GC microelectrode that was used as control, a plasma-etched GC microelectrode (120W for 45 s) with a coating of GluOx mixture containing glutaraldehyde and BSA, and a GC microelectrode with a GluOx mixture without glutaraldehyde and BSA. Each sample was washed with methanol, dried, and placed on the diamond cell, followed by recordings of 128 spectral scans that were subsequently compiled from 4 diagonal areas of the microelectrodes.

2.6. Voltammetry

Indirect detection of glutamate through direct electrochemical detection of the conversion product H2O2 was performed with a WaveNeuro Potentiostat System (Pine Research, NC). The surface functionalized GC microelectrode was used as the working electrode with a standard Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The electrolyte solution was phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (0.01 M, pH 7.4; Sigma Aldrich, USA). A waveform consisting of triangle scan at scan rate of 400 V/s from −0.5 V to +1.3 V with a holding potential of -0.5 V with respect to Ag/AgCl reference electrode was used. The duration of each scan was 9 ms and the frequency was 10 Hz. The same voltage waveform was applied to microelectrodes at 60 Hz for 1 hour prior to the start of each experiment for preconditioning. Known concentrations of glutamate (10 nM – 1.6 μM) were then infused over 5 sec while changes in current were recorded for 30 s. For a control experiment, a separate probe with no surface functionalization was subjected to the same waveform.

3. Results and Discussion

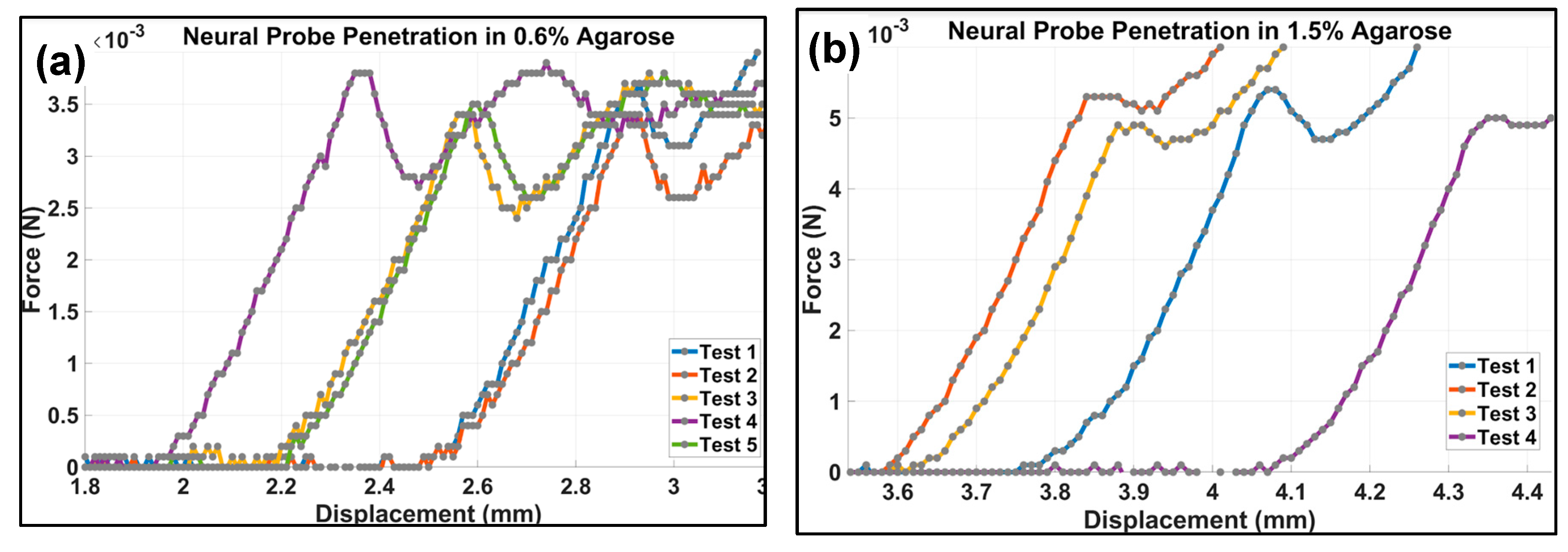

3.1. Mechanical Characterization

Figure 4 shows the force-displacement plots for the penetration force test with the neural probe for agarose hydrogel of 0.6% concentration, which was found to be a good model for brain tissue (Section S2). The first clearly identifiable peak shown in

Figure 4 corresponds to the first section of the neural probe penetrating the surface of the gel. The penetration force is then the first maximum of the force-displacement curve. The force needed for penetration of the 0.6% agarose hydrogel simulating the brain tissue was 0.0035 ± 0.00015 N (

n = 5) while for the 1.5% agarose hydrogel, the penetration force was 0.0051 ± 0.00028 N (

n = 4).

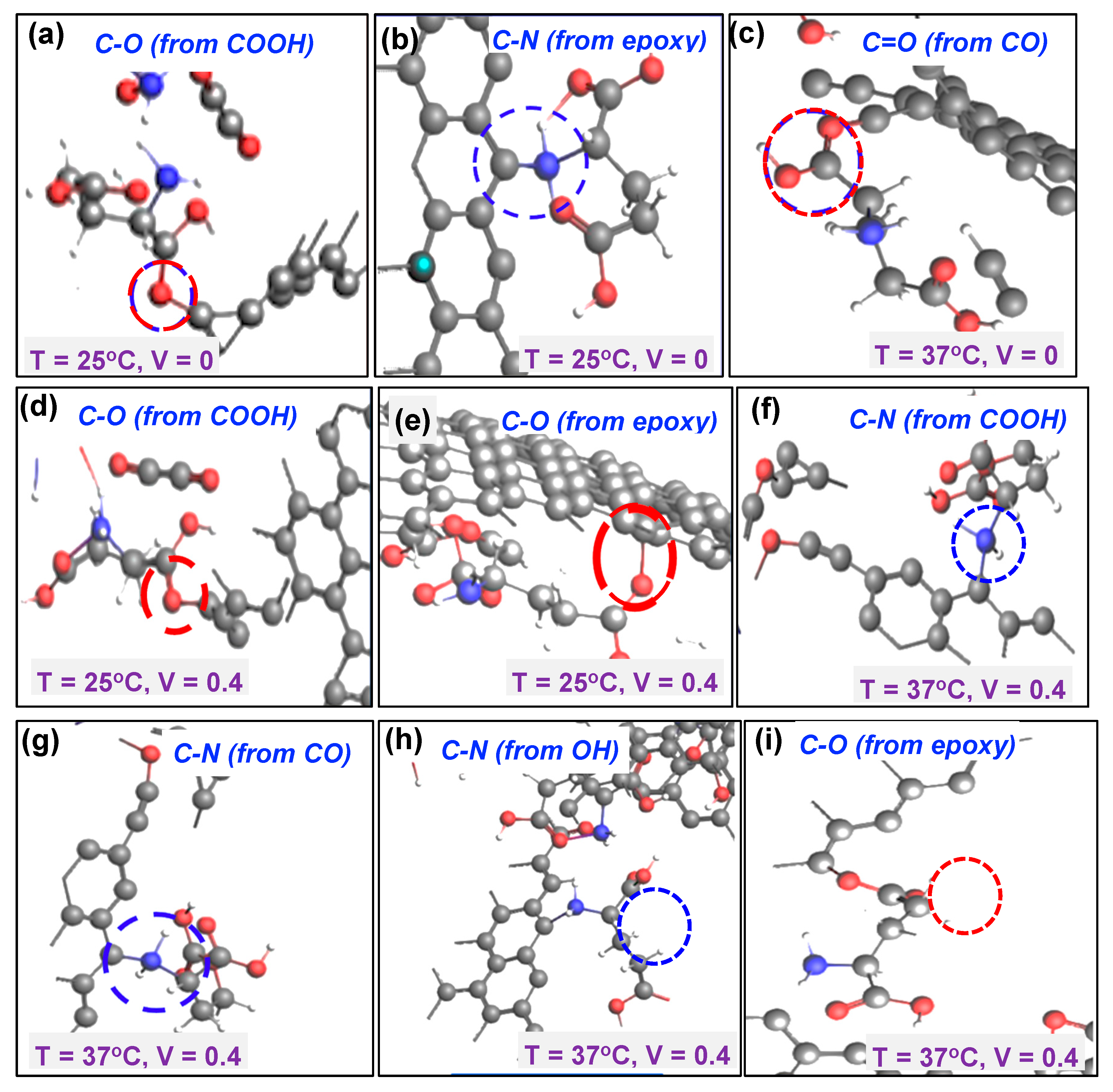

3.2. Molecular Dynamics Modeling

We explored the interaction of the functional groups (

COOH, CO, OH, and O) on the carbon microelectrode material with

glutamate and the immobilized enzyme mix. For this, we considered the effect of electrical bias (0V, 0.4 V), temperature (25

oC and 37

oC), type of functional groups, number of molecules of

glutamate, and the lattice of the

6-member carbon ring group on this interaction. Several potential interactions with functional groups to produce covalent bonds were explored. As shown in

Figure 5a, the

carboxyl (COOH) functional group was observed to interact with

glutamate at a temperature of 25°C with no electrical bias with the

glutamate molecule forming a carbon-oxygen (

C-O) covalent bond with the functionalized GC microelectrode surface. This interaction occurred due to the donation of electrons by

glutamate. The epoxide group was observed to facilitate the formation of a strong carbon-nitrogen (

C-N) covalent bond between nitrogen molecule from

glutamate and the carbon molecule of the microelectrode (

Figure 5b). However, at this temperature and 0 voltage bias, no interactions were observed for

carbonyl (CO) and

hydroxyl (OH) functional groups. Considering a slightly higher temperature of 37

oC, the carbonyl functional group (

CO) results in a

C=O covalent bond (

Figure 5c).

In the next set of simulations, the effect of electrical bias was explored under temperatures of 27

oC and 37

oC. In the case of temperature of 25

oC, similar outcomes as for the 0 V bias case were observed (

Figure 5d,e). However, at the temperature of 37

oC, all the four functional groups were observed to enable formation of a covalent bond between

glutamate and the carbon microelectrode surface. In the case of carboxyl group, increasing the temperature to 37°C combined with electrical bias at 0.4 V resulted in a carbon-nitrogen (

C-N) bond (

Figure 5f). Similarly, for carbonyl group, increasing the temperature to 37°C led to carbon-nitrogen (

C-N) bond as shown in

Figure 5g, demonstrating the effect of elevated temperature for forming bonds. For hydroxyl group, a carbon-nitrogen (

C-N) bond was observed, while in the case of epoxide group, an immediate attachment of

glutamate through a carbon-oxygen (C-O) bond was observed. A summary of the interactions is presented in

Table 1.

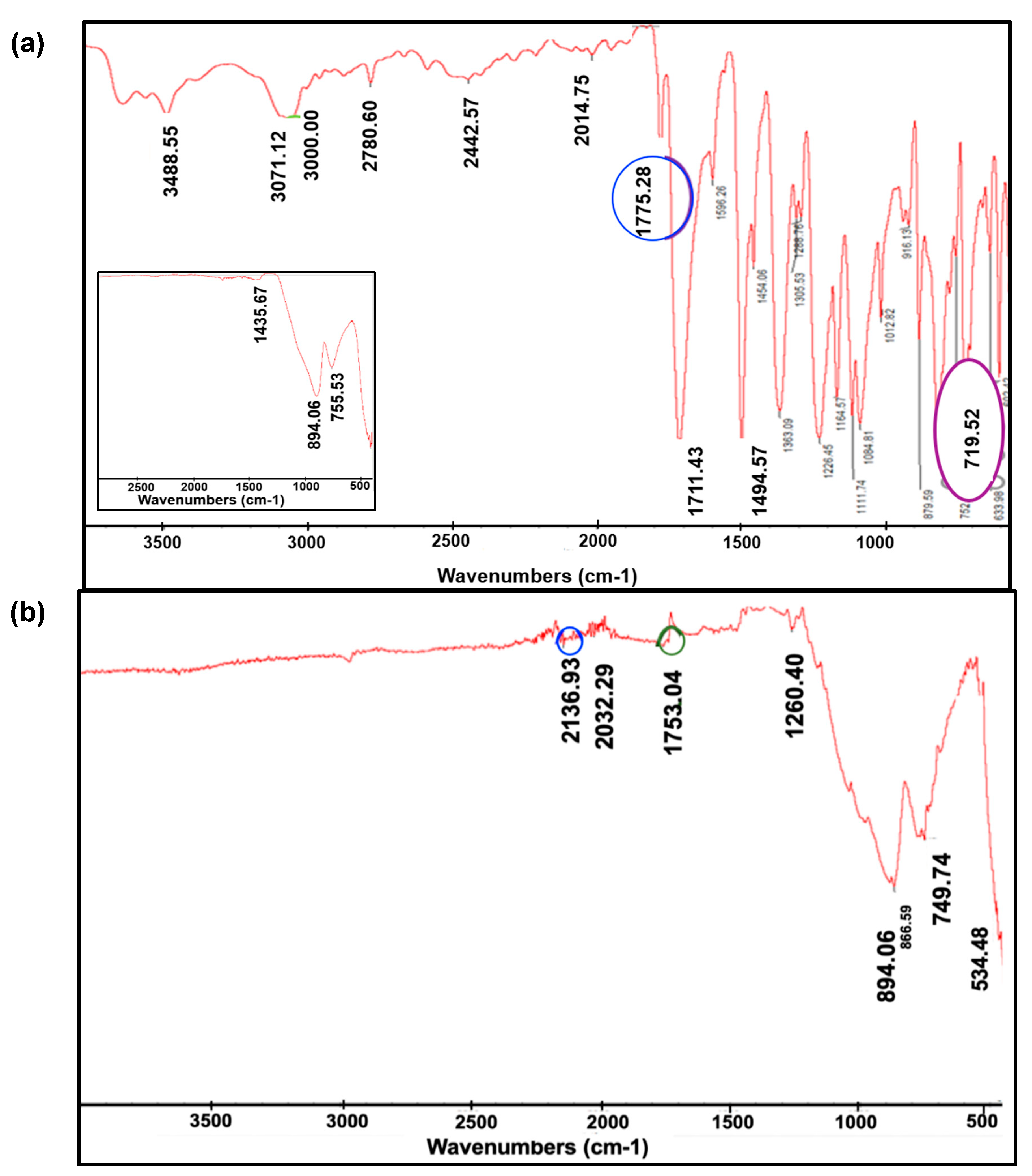

3.3. FTIR Characterization

For the bare GC control specimen (inset in

Figure 6a), three clear and distinct peaks that ranged between

1435.67 cm-1 - 755.53 cm-1 were detected, representing

C-O stretch with a single bond [

61]. The second sample had its bare GC surface plasma-etched at

120 W for

45 seconds before coating it with

glutamate oxidase mixture.

Figure 6a summarizes several peaks for the

glutamate oxidase sample on top of GC: the first peak at

3488.55 cm-1 corresponds to the amine stretch (

N-H) that potentially originated from unreacted amino groups in

glutamate oxidase and

L-glutamate [

62], while the peak at

3071.12 cm-1 corresponds to alkenyl (

C-H) stretch and its neighbor peak of

3000 cm-1 corresponds to unsaturated alkene (

C=C) compounds. Carboxylic acid (

C=O) peaks are represented by stretch in the region of

1775.28 cm-1 - 719.52 cm-1 while (

C-H) bending vibration with single or multiple absorption bands is represented by

719.52 cm-1 [

63]. For the third sample that was coated with

glutamate oxidase, more peaks were detected as shown in

Figure 6b where the characteristic absorption ranged between

2136.93 cm-1 -

534.48 cm-1. The highest fingerprint was

2136.9 cm-1 that is a triple bond between carbon and nitrogen stretch

(C≡N), and the second peak was

1753.04 cm-1 which corresponds to an aldehyde

C=O stretch; this one, in particular, is derived from the

glutaraldehyde present on the surface of the microelectrode from the enzyme mixture [

64].

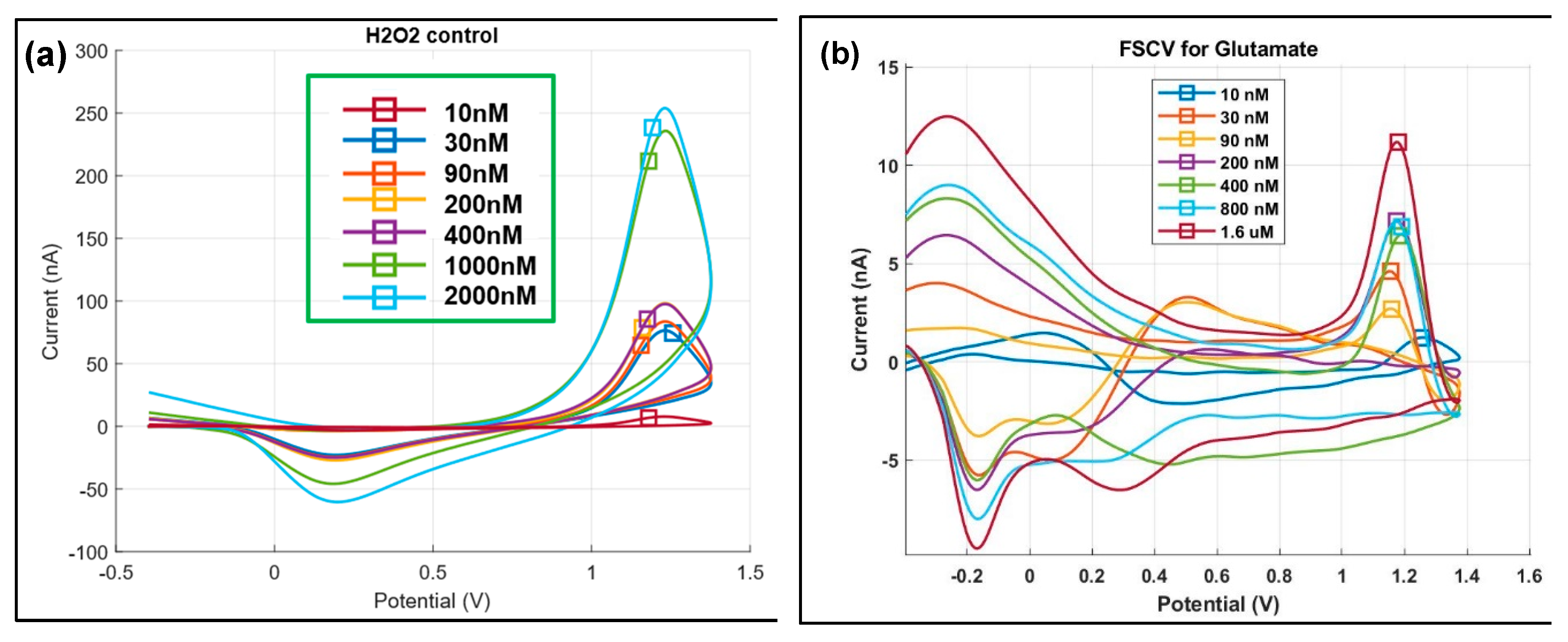

3.4. In Vitro Glutamate Detection through Voltammetry

As described earlier, due to the non-electroactive nature of

glutamate, background-subtracted FSCV for

glutamate was performed indirectly through the immobilization of

glutamate oxidase (

GluOx) enzyme on the surface of GC microelectrodes. The

GluOx enabled catalysis of chemical reaction between

L-glutamate, oxygen, and water to produce an electroactive byproduct (

H2O2) that is readily detectable through voltammetry. Since typical FSCV runs result in accelerated oxidation and reduction of electroactive and non-electroactive species on the electrode surface and hence form an electrical double layer, the background currents (BC) were subtracted before the peaks could be identified [

63]. As a control, the first set of experiments involved injecting solution of

H2O2 on bare GC microelectrode at varying concentrations over a period of 25 minutes (Table S2).

Figure 7a shows the resulting redox peaks in a background-subtracted FSCV for

H2O2 with oxidation occurring at 1.2V and reduction at -0.2V [

66]. As the second set of control experiment, FSCV was carried out on bare GC electrodes where

glutamate of varying concentration was injected. However, there was no redox peaks observed for this control experiment. On the other hand, for the actual experiment, another probe was used where

glutamate of varying concentration (10 nM – 1.6 μM) was injected to PBS solution. This was done over a period of 30 minutes as shown in Table S2, with sufficient time provided in-between each step to allow for stabilization of FSCV data collection.

Figure 7b shows the resulting background-subtracted FSCV plots indicating that the GC microelectrode was able to detect the

glutamate conversion byproduct

H2O2 obtained at a

glutamate concentration as low as

10 nM with

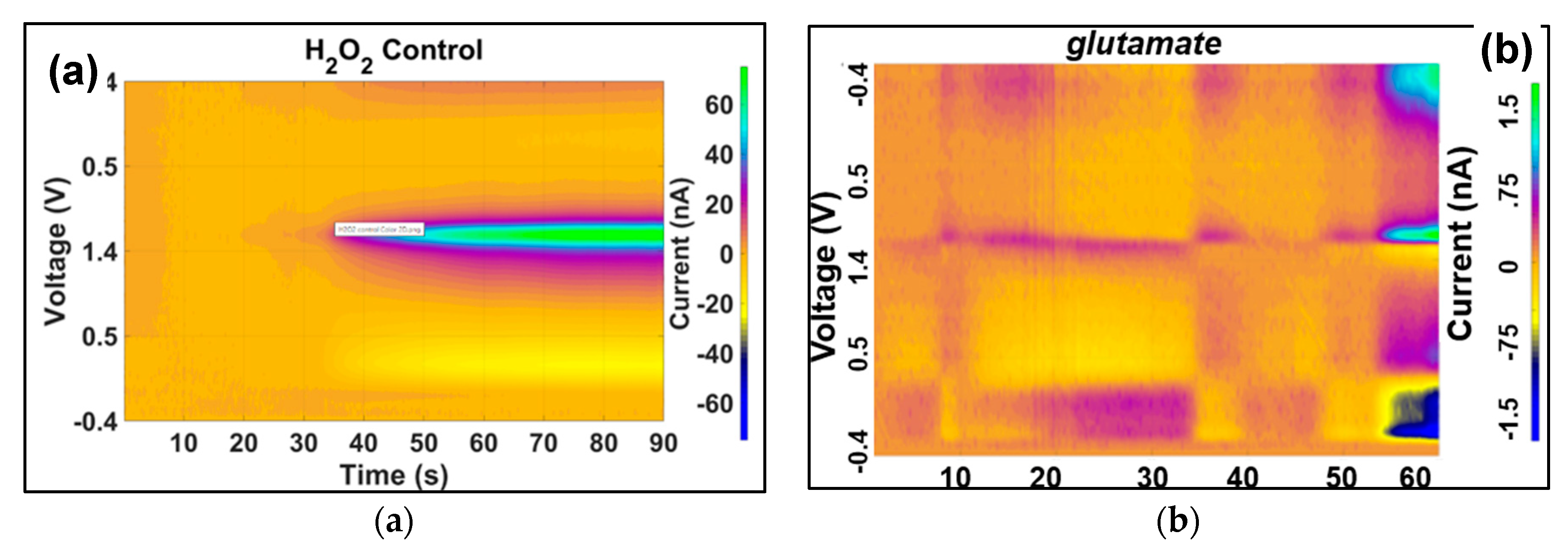

an oxidation peak at 1.2 V and reduction peak at -0.2 V. False-color plot of

Figure 8a shows the transient oxidation and reduction of 200 nM of

H2O2 injected to PBS solution (control). The false-color plot for injection of 10 nM of

glutamate to PBS PBS solution is shown in

Figure 8b.

4. Discussions and Conclusion

While GC has been demonstrated to be effective in detecting electroactive neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin at concentrations as low as 10 nm, its potential use for non-electroactive ones like glutamate has been so far unexplored. Against a background of a long-term research interest in the simultaneous detection of multiple neurotransmitters using GC voltammetry electrodes located on the same probe, the extension of this capability of GC to such detection of non-electroactive analytes like glutamate carries potential for significant contribution in the broader research discipline of neurochemistry. In this regard, the first obstacle that had to be addressed in extending its capability to glutamate was the integrity of the needed surface functionalization. Two approaches were sought to demonstrate formation of covalent bond between the carbon surface and the enzymes used for surface functionalization, i.e., FTIR and reactive molecular dynamics (MD) modeling. FTIR confirmed the existence of C-O stretch with a single bond, an aldehyde/carboxylic/carbonyl C=O stretch, alkenyl C-H bending, a triple bond between nitrogen and carbon stretch (C≡N), an amine stretch (N-H) that potentially originated from unreacted amino groups in glutamate oxidase and L-glutamate. On the other hand, MD modeling predicted C-O and C=O bonds arising due to carboxyl (COOH) and epoxy (O) functional groups at 25oC and 37oC and no bias conditions. However, in the presence of a nominal voltage bias of 0.4 V and temperature of 37oC, carboxyl, carbonyl (CO), and hydroxyl (OH) groups were observed to interact with glutamate forming a C-N bond. The absence of amine stretch (N-H) in the MD simulation could be explained by the absence of unreacted amino groups in the model.

In general, these results obtained through reactive MD modeling are consistent with what was recently reported in a simulation work regarding the binding properties of pristine graphene and graphene derivatives with

glutamate where the bond formations were driven mainly by the same four functional groups, i.e.,

COOH,

carbonyl,

hydroxyl, and

epoxy [

65]. Further, simulation based on molecular docking mechanisms between the functional groups and carbon (in the form of graphene) also demonstrated that the

COOH functional group presented the highest stability among the four groups considered. The observation that all functional groups located on the surface of the electrode formed some sort of covalent bond with

glutamate at a physiologically relevant temperature of 37

oC with a nominal voltage bias is very encouraging and builds a case for the effectiveness of GC as a

glutamate sensing electrode material. The presence of these bonds also points to a potential durability of this surface functionalization. In addition, for fast detection of analytes with low-detection limits, diffusion and then subsequent adsorption of the analytes on the surface of the electrode are important and critical components. While prior work on the diffusion of glutamate towards carbon surfaces is missing in the literature, the demonstration of adsorption through bond formation here is an important outcome that further supports the effectiveness of GC for sensing

glutamate at low detection limits.

With the presence of strong covalent bonds between surface of GC electrode and the functionalization enzyme established, the next task was demonstrating the validity and effectiveness of indirect voltammetric detection of glutamate through its by-product of H2O2. The evidence presented in this research indicates strong correlations between H2O2 and glutamate, enabling detection of 10 nM concentration of glutamate, an important milestone. In general, therefore, the data presented here from the in vitro detection of glutamate are promising, with the modified GC electrodes capable of detecting a wide range of concentrations of the byproduct of enzymatic glutamate conversion. Testing penetration of the probe in agarose gel based in vitro brain models confirmed that the probe used in this experiment is appropriate for brain penetration. Validation of the in vitro data presented here through in vivo testing, demonstration of detection of other non-electroactive neurotransmitters such as lactate, and – more importantly - the simultaneous detection of electroactive and non-electroactive neurotransmitters on the same probe will form a natural extension of this current work.

Author Contributions

S.L.G fabricated the devices, implemented the microfabrication process, analyzed the results and wrote the materials and methods and results sections of the paper; S.N helped set up the molecular dynamics simulations; A.O helped in microfabrication; J.B helped with plots and analysis; O.N.C helped with SEM imaging; R.M.W. helped set up the molecular dynamics simulations; A.R helped in microelectrode characterization; B.K.C and A.G helped in microfabrication; K.P.G helped with FTIR; J.L helped with MATLAB plots; S.I.B designed and carried out the mechanical characterizations; C.F helped with chemistry of glutamate oxidase and glutamate as they relate to MD modeling, S.S.K reviewed the manuscript; and S.K. formulated the concept, supervised the project, structured the outline of the paper, edited the manuscript, and wrote the introduction, discussion and conclusion section of the paper.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on research work supported by the Center for Neurotechnology (CNT), a National Science Foundation Engineering Research Center (EEC-1028725). S.I.B. and S.S.K acknowledge funding from the Independent Research Fund Denmark (Grant no. 8022-00215B).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Si, B.; Song, E. Recent Advances in the Detection of Neurotransmitters. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskarjov, M.; Seja, P.; E Heron, S.; Williams, T.C.; Ahmad, F.; Iona, X.; Oliver, K.L.; E Grinton, B.; Vutskits, L.; E Scheffer, I.; et al. A variant of KCC 2 from patients with febrile seizures impairs neuronal Cl − extrusion and dendritic spine formation. Embo Rep. 2014, 15, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotharius, J.; Brundin, P. Pathogenesis of parkinson's disease: dopamine, vesicles and α-synuclein. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 932–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gründer, G., and P. Cumming. 2016. “Computational Neuroanatomy of Schizophrenia.” The Neurobiology of Schizophrenia 1: 263–82. [CrossRef]

- Wise, R.A. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haber, S.N.; Knutson, B. The Reward Circuit: Linking Primate Anatomy and Human Imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology 2009, 35, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryczko, D.; Dubuc, R. Dopamine and the Brainstem Locomotor Networks: From Lamprey to Human. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felger, J.C.; Treadway, M.T. Inflammation Effects on Motivation and Motor Activity: Role of Dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 42, 216–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pithadia, A. 5-Hydroxytryptamine Receptor Subtypes and their Modulators with Therapeutic Potentials. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2009, 1, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.E. 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP): Natural Occurrence, Analysis, Biosynthesis, Biotechnology, Physiology and Toxicology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, R.; Rivas-Santisteban, R.; Lillo, J.; Camps, J.; Navarro, G.; Reyes-Resina, I. 5-Hydroxytryptamine, Glutamate, and ATP: Much More Than Neurotransmitters. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 667815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründer, G., & Cumming, P. (2016). “The Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia: Current Status,” In T. Abel & T. Nickl-Jockschat (Eds.), The Neurobiology of Schizophrenia (pp. 109–124). Elsevier Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Fakhoury, M. Revisiting the Serotonin Hypothesis: Implications for Major Depressive Disorders. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 53, 2778–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schloss, P.; Williams, D.C. The serotonin transporter: a primary target for antidepressant drugs. J. Psychopharmacol. 1998, 12, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yohn, C.N.; Gergues, M.M.; Samuels, B.A. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol. Brain 2017, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celada, P.; Puig, M.V.; Artigas, F. Serotonin modulation of cortical neurons and networks. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Danbolt, N.C. Glutamate as a neurotransmitter in the healthy brain. J. Neural Transm. 2014, 121, 799–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramadan, S.; Lin, A.; Stanwell, P. Glutamate and glutamine: a review of in vivo MRS in the human brain. NMR Biomed. 2013, 26, 1630–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker-Haliski, M.; White, H.S. Glutamatergic Mechanisms Associated with Seizures and Epilepsy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a022863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statstrom, C. E, and L. Carmant. 2016. “Seizures and Epilepsy: An Overview.” Epilepsy: The Intersection of Neurosciences, Biology, Mathematics, Engineering, and Physics, 65–77. [CrossRef]

- Beghi, E. The Epidemiology of Epilepsy. Neuroepidemiology 2019, 54, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, A.M.; Pal, R.; Michealis, E.K.; Lunte, C.E.; Lunte, S.M. Neurochemical investigation of multiple locally induced seizures using microdialysis sampling: Epilepsy effects on glutamate release. Brain Res. 2019, 1722, 146360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Lozano, C.S.; Dallapiazza, R.F.; Lozano, A.M. Current and future directions of deep brain stimulation for neurological and psychiatric disorders. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 131, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, S.P.; Maksymetz, J.; Conn, P.J. Targeting Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors for the Treatment of Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 1006–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Marques, T.R.; Howes, O.D. Schizophrenia—An Overview. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, E.R., & Schwartz J.H., & Jessell T.M., & Siegelbaum S.A., & Hudspeth A.J., & Mack S(Eds.), (2014). Principles of Neural Science, Fifth Edition. McGraw Hill.

- Ludwig, Parker E, Vamsi Reddy, and Matthew Varacallo. 2022. “Neuroanatomy, Central Nervous System (CNS).” In StatPearls Publishing. Treasure Island (FL).

- Obien, M.E.J.; Deligkaris, K.; Bullmann, T.; Bakkum, D.J.; Frey, U. Revealing neuronal function through microelectrode array recordings. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereda, A.E. Electrical synapses and their functional interactions with chemical synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozorgzadeh, B.; Schuweiler, D.R.; Bobak, M.J.; Garris, P.A.; Mohseni, P. Neurochemostat: A Neural Interface SoC With Integrated Chemometrics for Closed-Loop Regulation of Brain Dopamine. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2015, 10, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahn, P.J.; Mallory, G.W.; Khurram, O.U.; Berry, B.M.; Hachmann, J.T.; Bieber, A.J.; Bennet, K.E.; Min, H.-K.; Chang, S.-Y.; Lee, K.H.; et al. A neurochemical closed-loop controller for deep brain stimulation: toward individualized smart neuromodulation therapies. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bath, B.D.; Michael, D.J.; Trafton, B.J.; Joseph, J.D.; Runnels, P.L.; Wightman, R.M. Subsecond Adsorption and Desorption of Dopamine at Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 5994–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.H.; Oh, Y.; Shin, H.; Park, C.; Blaha, C.D.; Bennet, K.E.; Kim, I.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Jang, D.P. Multi-waveform fast-scan cyclic voltammetry mapping of adsorption/desorption kinetics of biogenic amines and their metabolites. Anal. Methods 2018, 10, 2834–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadlaghani, A.; Farzaneh, M.; Kinser, D.; Reid, R.C. Direct Electrochemical Detection of Glutamate, Acetylcholine, Choline, and Adenosine Using Non-Enzymatic Electrodes. Sensors 2019, 19, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, S.L.; Ronkainen, N.J. “Enzyme-Based Electrochemical Glutamate Biosensors.” In Electrochemical Sensors Technology, Rahman, M. M.; Asiri, A. M., Eds.; InTech, 2017.

- Shin, M.; Wang, Y.; Borgus, J.R.; Venton, B.J. Electrochemistry at the Synapse. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 12, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimble, L.C.; Twiddy, J.S.; Berger, J.M.; Forderhase, A.G.; McCarty, G.S.; Meitzen, J.; Sombers, L.A. Simultaneous, Real-Time Detection of Glutamate and Dopamine in Rat Striatum Using Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. ACS Sensors 2023, 8, 4091–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manciu, F.S.; Oh, Y.; Barath, A.; Rusheen, A.E.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Hodges, D.; Guerrero, J.; Tomshine, J.; Lee, K.H.; Bennet, K.E. Analysis of Carbon-Based Microelectrodes for Neurochemical Sensing. Materials 2019, 12, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swinya, D.L.; Swinya, D.L.; Martin-Yerga, D.; Martin-Yerga, D.; Walker, M.; Walker, M.; Unwin, P.R.; Unwin, P.R. Surface Nanostructure Effects on Dopamine Adsorption and Electrochemistry on Glassy Carbon Electrodes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 13399–13408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Honarvarfard, E.; Torabi, F.; Maleki, H.; Baharifar, H.; Faridbod, F.; Larijani, B.; Khorramizadeh, M.R. Electrochemical detection of serotonin: A new approach. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 501, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, A.; Asrat, T.; Liu, F.; Wonnenberg, P.; Zestos, A.G. Carbon Nanotube Yarn Microelectrodes Promote High Temporal Measurements of Serotonin Using Fast Scan Cyclic Voltammetry. Sensors 2020, 20, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Atcherley, C.W.; Pathirathna, P.; Samaranayake, S.; Qiang, B.; Peña, E.; Morgan, S.L.; Heien, M.L.; Hashemi, P. In Vivo Ambient Serotonin Measurements at Carbon-Fiber Microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 9703–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castagnola, E.; Vahidi, N.W.; Nimbalkar, S.; Rudraraju, S.; Thielk, M.; Zucchini, E.; Cea, C.; Carli, S.; Gentner, T.Q.; Ricci, D.; et al. In Vivo Dopamine Detection and Single Unit Recordings Using Intracortical Glassy Carbon Microelectrode Arrays. MRS Adv. 2018, 3, 1629–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnola, E.; Thongpang, S.; Hirabayashi, M.; Nava, G.; Nimbalkar, S.; Nguyen, T.; Lara, S.; Oyawale, A.; Bunnell, J.; Moritz, C.; et al. Glassy carbon microelectrode arrays enable voltage-peak separated simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotonin using fast scan cyclic voltammetry. Anal. 2021, 146, 3955–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamy, B.E.K.; Venton, B.J. Carbon nanotube-modified microelectrodes for simultaneous detection of dopamine and serotonin in vivo. Analyst 2007, 132, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Van der Zeyden, M.; Oldenziel, W.H.; Cremers, T.I.; Westerink, B.H. Microsensors for in vivo Measurement of Glutamate in Brain Tissue. Sensors 2008, 8, 6860–6884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Zeyden, M.; Oldenziel, W.H.; Rea, K.; Cremers, T.I.; Westerink, B.H. Microdialysis of GABA and glutamate: Analysis, interpretation and comparison with microsensors. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2008, 90, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; Wu, P.; Chen, G.; Cai, C.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, Z. Low potential detection of glutamate based on the electrocatalytic oxidation of NADH at thionine/single-walled carbon nanotubes composite modified electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 1751–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vomero, M.; Castagnola, E.; Ciarpella, F.; Maggiolini, E.; Goshi, N.; Zucchini, E.; Carli, S.; Fadiga, L.; Kassegne, S.; Ricci, D. Highly Stable Glassy Carbon Interfaces for Long-Term Neural Stimulation and Low-Noise Recording of Brain Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vomero, M.; van Niekerk, P.; Nguyen, V.; Gong, N.; Hirabayashi, M.; Cinopri, A.; Logan, K.; Moghadasi, A.; Varma, P.; Kassegne, S. A novel pattern transfer technique for mounting glassy carbon microelectrodes on polymeric flexible substrates. J. Micromechanics Microengineering 2016, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbalkar, S.; Castagnola, E.; Balasubramani, A.; Scarpellini, A.; Samejima, S.; Khorasani, A.; Boissenin, A.; Thongpang, S.; Moritz, C.; Kassegne, S. Ultra-Capacitive Carbon Neural Probe Allows Simultaneous Long-Term Electrical Stimulations and High-Resolution Neurotransmitter Detection. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisgaard, S.I.; Nguyen, L.Q.; Bøgh, K.L.; Keller, S.S. Dermal tissue penetration of in-plane silicon microneedles evaluated in skin-simulating hydrogel, rat skin and porcine skin. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2023, 155, 213659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomfret, R.; Miranpuri, G.; Sillay, K. The Substitute Brain and the Potential of the Gel Model. Ann. Neurosci. 2013, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budday, S.; Ovaert, T.C.; Holzapfel, G.A.; Steinmann, P.; Kuhl, E. Fifty Shades of Brain: A Review on the Mechanical Testing and Modeling of Brain Tissue. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2020, 27, 1187–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Boakye-Yiadom, S.; Cronin, D. Comparison of porcine brain mechanical properties to potential tissue simulant materials in quasi-static and sinusoidal compression. J. Biomech. 2019, 92, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Duin, A.C.T.; Dasgupta, S.; Lorant, F.; Goddard, W.A. ReaxFF: A Reactive Force Field for Hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 9396–9409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery-Walsh, R.; Nimbalkar, S.; Bunnell, J.; Galindo, S.L.; Kassegne, S. Molecular dynamics simulation of evolution of nanostructures and functional groups in glassy carbon under pyrolysis. Carbon 2021, 184, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senftle, T., Hong, S., Islam, M. et al. “The ReaxFF Reactive Force-Field: Development, Applications and Future Directions”, NPI Comput Mater 2, 15011 (2016).

- Russo, M. F. Jr and van Duin, A. C. T. “Atomistic-Scale Simulations of Chemical Reactions: Bridging from Quantum Chemistry to Engineering,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 269, 1549–1554 (2011).

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Oktiani, R.; Ragadhita, R. How to Read and Interpret FTIR Spectroscope of Organic Material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mureşan-Pop, M, I Kacsó, X Filip, E Vanea, G. Borodi, N. Leopold, I. Bratu, and S. Simon. 2011. “Spectroscopic and Physical-Chemical Characterization of Ambazone-Glutamate Salt.” Spectroscopy 26 (2): 115–28. [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, V.; Keesey, R.; Madden, D.R. Ligand−Protein Interactions in the Glutamate Receptor. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 8693–8697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batra, B.; Pundir, C. An amperometric glutamate biosensor based on immobilization of glutamate oxidase onto carboxylated multiwalled carbon nanotubes/gold nanoparticles/chitosan composite film modified Au electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 47, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonel, M.Z.; González-Durruthy, M.; Zanella, I.; Fagan, S.B. Interactions of graphene derivatives with glutamate-neurotransmitter: A parallel first principles - Docking investigation. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 88, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanford, A.L.; Morton, S.W.; Whitehouse, K.L.; Oara, H.M.; Lugo-Morales, L.Z.; Roberts, J.G.; Sombers, L.A. Voltammetric Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide at Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 5205–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).