1. Introduction

Zeolites have been successfully employed as catalysts in numerous reactions due to their stable and well-ordered structure, high surface area and tunable acidity. However, their microporous structure imposes diffusive restrictions and makes them susceptible to deactivation by fouling and coke deposition. To overcome these limitations, several techniques have been developed to synthesize hierarchical zeolites, which combine microporous and mesoporous pore networks [

1,

2,

3]. These methods include syntheses in the presence of a template [

4,

5], alkaline treatments [

4,

6,

7,

8], steaming [

4], layering [

9] and pillaring [

9,

10].

Originally developed as a purification method [

11], the treatment of zeolites with alkaline solutions has become a widespread method to generate mesoporosity and improve the overall mass-transfer through the structure. This procedure removes selectively silicon atoms and its speed and extent increases in zeolites containing low aluminum contents. This behavior is attributed to the difference in solubility of silica and alumina at pH values above 9.5 [

12,

13], to the point where Al atoms prevent the dissolution of neighboring Si atoms [

14]. Thus, the optimum range for the application of this method is Si/Al = 15-50. Framework defects are also attacked preferentially. Therefore, the main variables to be considered are Si/Al ratio of the parent material, temperature, duration, the alkali used and its concentration. Early studies by Ogura et al [

15] set the conditions to treat MFI zeolites avoiding significant loss of material. Later, Groen et al. [

16,

17,

18] explored a wide range of variables and their influence on the structural properties, finding that the alkaline treatment did not affect the acidity of the materials. Tzoulaki et al. [

4] also found no influence of the alkaline treatment on the Brønsted acid sites in the micropores but reported an increase in site accessibility. Further steaming of the treated zeolite led to a decrement in acid sites concentration.

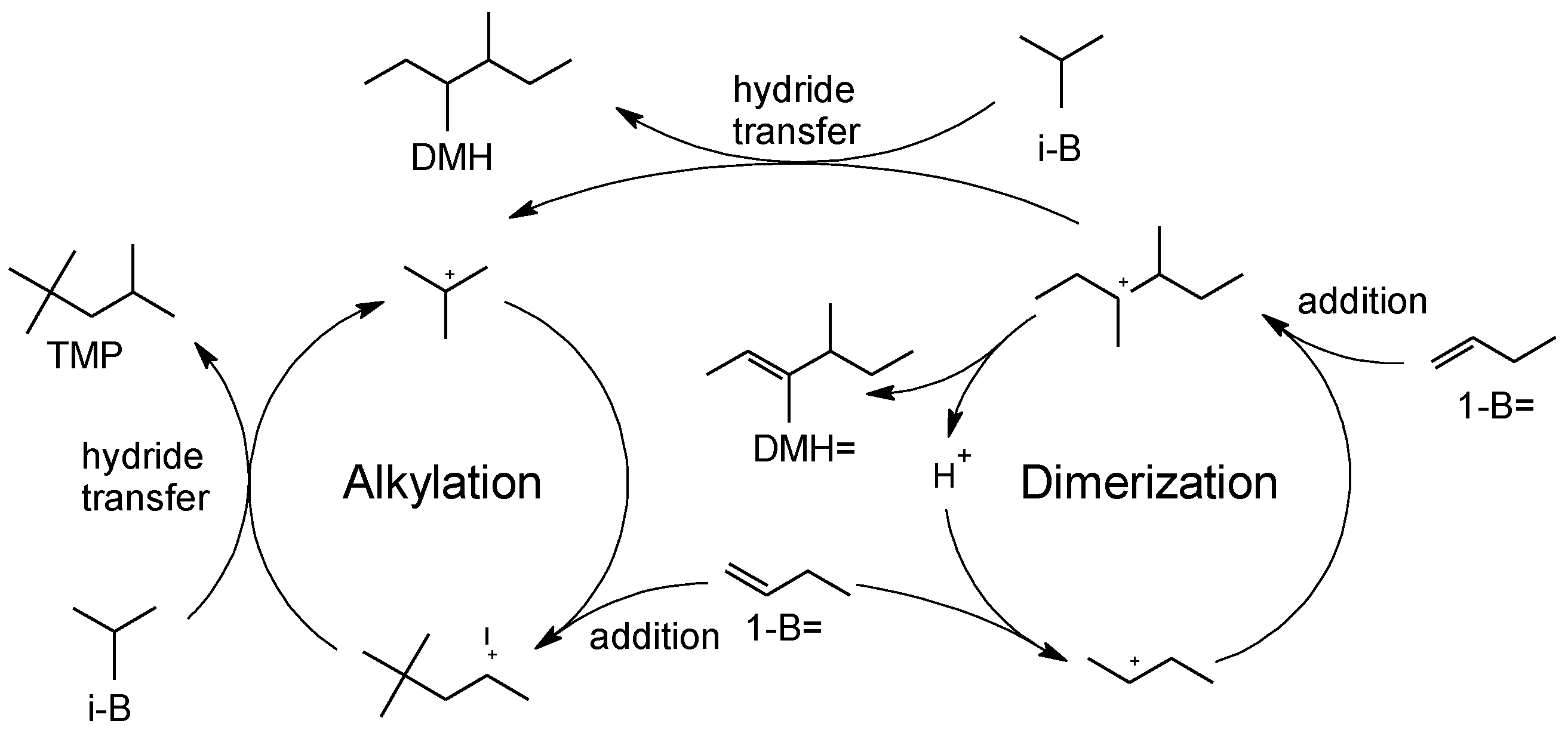

The alkylation of isobutane with butenes is a reaction of addition, which yields trimethylpentanes (TMP) as products of interest (

Scheme 1). This mixture of multibranched isoparaffins (also known as alkylated product) present high octane number (RON and MON), low vapor pressure and null sulfur content, making it an interesting stream for gasoline blending. The reaction is catalyzed by strong acids, and current industrial units typically operate either with HF or with H

2SO

4 [

19,

20]. However, these processes are costly and hazardous due to the requirement of separation and treatment of spent acid, as well as the maintenance of important mitigation system in case of spill or leak. Several solid acid catalysts have been developed to overcome these issues, including heteropolyacids [

21,

22], zirconia [

23,

24] and zeolites as MOR [

25], *BEA [

24,

26,

27], EMT [

28,

29], MFI [

30] and FAU [

28,

29,

31]. Among them, 12-member ring zeolites have shown the best performance due to their larger pore sizes. Nonetheless, they lack the stability to be applied at industrial scale. The deactivation mechanism consists in coke deposition, where the main factors influencing it are the porous structure and the acidity of the solids [

32]. The first one affects the diffusion rate of coke precursors and the ease of pore blockage. The latter allows the cracking of heavy species, thus preventing coke deposition. MFI zeolites have shown poor performance in the alkylation reaction, prevailing the dimerization reaction over alkylation. This is attributed to the impossibility to accommodate the bulkier transition state for the hydride transfer, the key step in the production of TMP. However, MFI zeolites present good cracking capacity, an important feature to prevent deactivation.

In a previous work [

33] the activity and accessibility of an alkaline-treated MFI zeolite (Si/Al = 15) was assessed. Since the Si/Al ratio was on the low end of feasibility for the treatment [

16], harsh conditions were necessary to develop mesoporosity. In consequence, extensive aluminum removal occurred and acidity was greatly affected, negatively impacting the catalytic activity. In this work, a parent material with a higher Si/Al ratio (40) was employed, in order to moderate the treatment conditions and provide a better preservation of the active sites. Therefore, it is proposed to evaluate the effect of the modification of the porous structure by alkaline treatment on the structural and acidic properties, and the impact on the activity for the alkylation of isobutane with 1-butene.

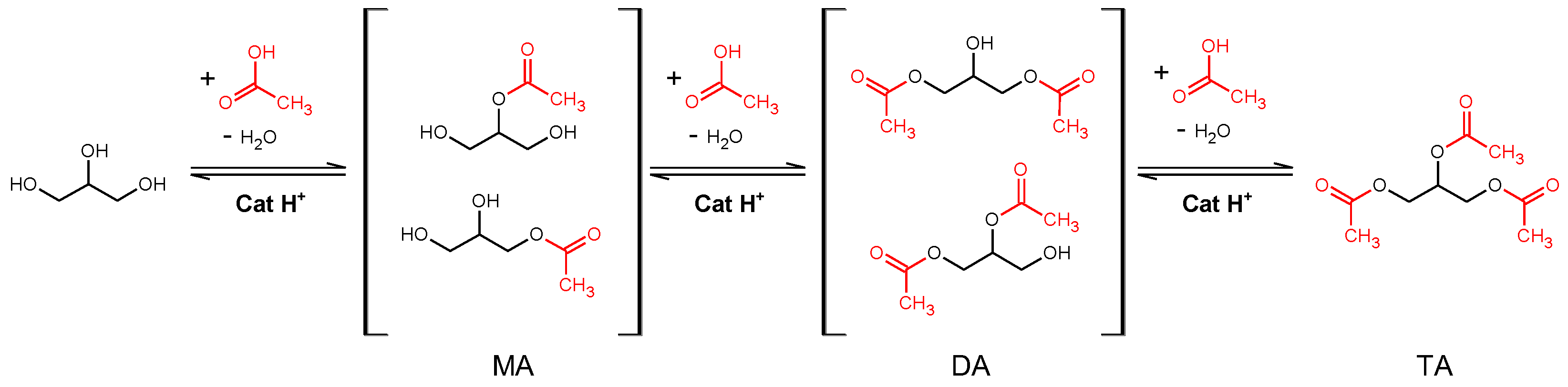

The esterification of glycerol with acetic acid is also employed as a test reaction (

Scheme 2). This reaction consists of three steps catalyzed by acid sites, yielding successively monoacetins (MA), diacetins (DA) and triacetin (TA). In this case, both reactants have small kinetic diameters, and they are able to penetrate the porous structure. However, their products are bulkier and present low accessibility to zeolitic structures. Therefore, studying the effect of treated catalyst on the reaction rate for each product can serve as an indicator of the accessibility of the acid sites and the characteristics of the generated mesopores.

2. Materials and Methods

Portions of a commercial MFI zeolite (CBV-8014, NH4-form, Si/Al = 40) were contacted with aqueous NaOH solutions (0.05 to 1 M), at different temperatures (298, 318 and 338 K). The solution to solid ratio was 30 ml of solution per gram of zeolite. Typically, the solution was preheated to the desired temperature in a beaker in a thermostatic bath equipped with magnetic stirring, then the corresponding amount of zeolite was added and the treatment was carried out for 30 min. Then, the beaker was quenched in a 273 K water bath to stop the reaction. The solid was centrifuged, washed with distilled water several times, and then dried overnight in an oven at 353 K. In order to restore the acidity, the solid was contacted with NH4NO3 0.5 M solution (20 ml per gram of zeolite) at 353 K under reflux for 2.5 h. It was then filtered, dried and calcined at 823 K (2 h, 1.5 K min-1) under air flow. This ion exchange was repeated. Samples were labeled Z40(M/T) where M was the alkali concentration and T was the treatment temperature. A sample treated for 60 min instead of 30 had the suffix “-1h”.

For reference, a portion of the parent material (Si/Al = 40) as well as an MFI Si/Al = 15 (CBV-3020E) were calcined under the same conditions and labeled Z40 and Z15, respectively.

Textural properties were obtained by N2-sorptometry using a Micromeritics ASAP-2020 equipment. Samples were outgassed at 523 K for 8 h, and the measurements were carried out at 77 K in the range of P/P° from 5×10-3 to 0.975. Surface area was estimated with the BET model, micropore volume and external area were estimated with the t-plot method using Harkins-Jura equation for the film thickness. Pore size distribution was derived from the method of Broekhoff and De Boer (BdB).

Crystallographic information was obtained by X-ray diffraction (XRD), with a Shimadzu XD-D1 device. Scans were performed in the range of 2θ from 5 to 60° with a speed of 2° min-1. Relative values of elemental composition were obtained by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with a Shimadzu EDX-720 in energy dispersion mode. Samples were analyzed in solid state.

The nature of the acid sites was studied by infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), using pyridine as a probe molecule. Samples were pressed into self-supporting wafers and placed in a cell. First, they were outgassed under vacuum at 723 K (1 h, 10 K min-1). Then, they were cooled down to 423 K and pyridine was injected. After 1 h, the samples were outgassed under vacuum (1 h, 423 K). Last, they were cooled down to room temperature and the spectra were recorded.

The amount of acid sites in the samples and their strength profile were determined by temperature-programmed desorption of bases (TPD). Pyridine (Py) and collidine (Col) were employed as probe molecules to test the accessibility of the sites. Typically, 10 mg of sample were placed in a quartz tube and pretreated under N2 flow (30 cm3 min-1, 1h, 623 K, 12 K min-1). Then, it was cooled down to 423 K and the catalyst bed was inundated with the liquid probe. After 30 min of contact, carrier gas was restored and the sample was purged for 1 h. Then the analysis was carried out, heating at 12 K min-1 to 1023 K and measuring the desorption of base with an FID coupled with a methanator for better precision. Dynamic adsorption-desorption experiments were carried out with the same setup. After the pretreatment, the sample was stabilized at 383 K and pulses of 1-butene (3 vol% in N2) were sent every 20 s, with the outlet of the reactor connected to the detector. After a sequence of 40 pulses, a TPD was performed to quantify the amount of 1-butene remnant in the sample.

Catalytic tests for the alkylation of isobutane with butenes in gas phase were carried out in a fixed bed reactor (5 mm i.d. × 70 mm), loaded with 200 mg of sample previously sieved, with granulometry between 0.420 and 0.177 mm (40-80 US standard mesh). Pretreatment was carried out in situ under N2 flow at 723 K for 1 h. The reaction mixture consisted in isobutane and 1-butene (both 99.5%, Indura) in proportion 16:1. It was loaded in a pressurized tank and fed to a vaporizer at 393 K where it was mixed with the carrier gas and fed to the reactor. The products were sampled with a multiloop valve and later analyzed with a GC equipped with an FID and a ZB-1 column (100 m). Coke deposition after the reaction was determined by temperature-programmed oxidation (TPO) in a setup similar to TPD. The sample was loaded in a quartz cell and heated from 298 to 1023 K at 12 K min-1 under O2 flow (5 vol% in N2, 30 cm3 min-1), and the CO and CO2 were quantified employing an FID coupled with a methanator.

The esterification of glycerol with acetic acid was tested in a batch reactor, in a thermostatted bath under stirring and reflux. Typically, 5 g of glycerol (99.5%, Ciccarelli) and 200 mg of catalyst were loaded and preheated to 393 K. Then 19.6 g of acetic acid (99.5%, Ciccarelli) were added. The mixture was sampled at regular intervals for GC analyses, which employed an HP-FFAP column (30 m).

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Treatment Conditions

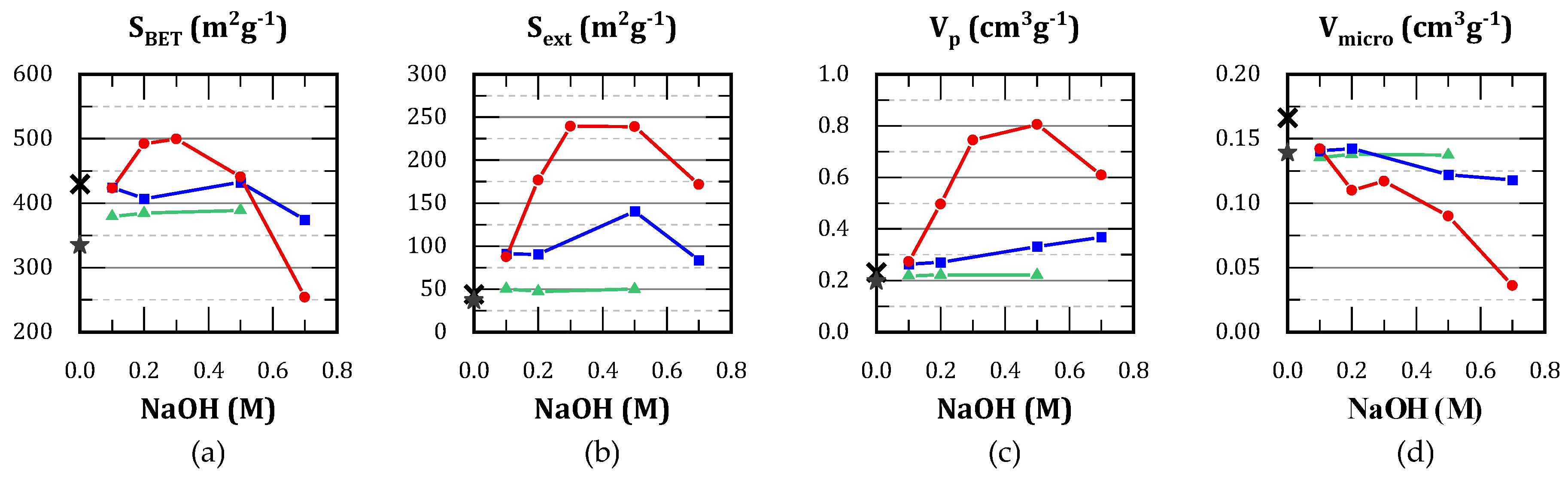

A screening of treatment conditions was conducted, varying the alkali concentration between 0.05 and 0.7 M, and the temperature between 25 and 65 °C. For the most advantageous condition, an additional test was carried out, extending the duration to 1 h. The textural properties and Si/Al ratios are shown in

Table 1, while the most representative results are represented in

Figure 1.

The treatment at 25 ºC was ineffective and no significant mesoporosity was obtained. The development of mesoporosity (by surface and volume) was observed from 45 ºC. This was enhanced at 65 ºC, but accompanied by a decrement in micropore volume. Furthermore, the optimum alkali concentration in order to generate mesopores was found between 0.2 and 0.5 M. Treatment with 0.7 M solution was detrimental for both the generation of mesopores as well as the preservation of preexistent micropores.

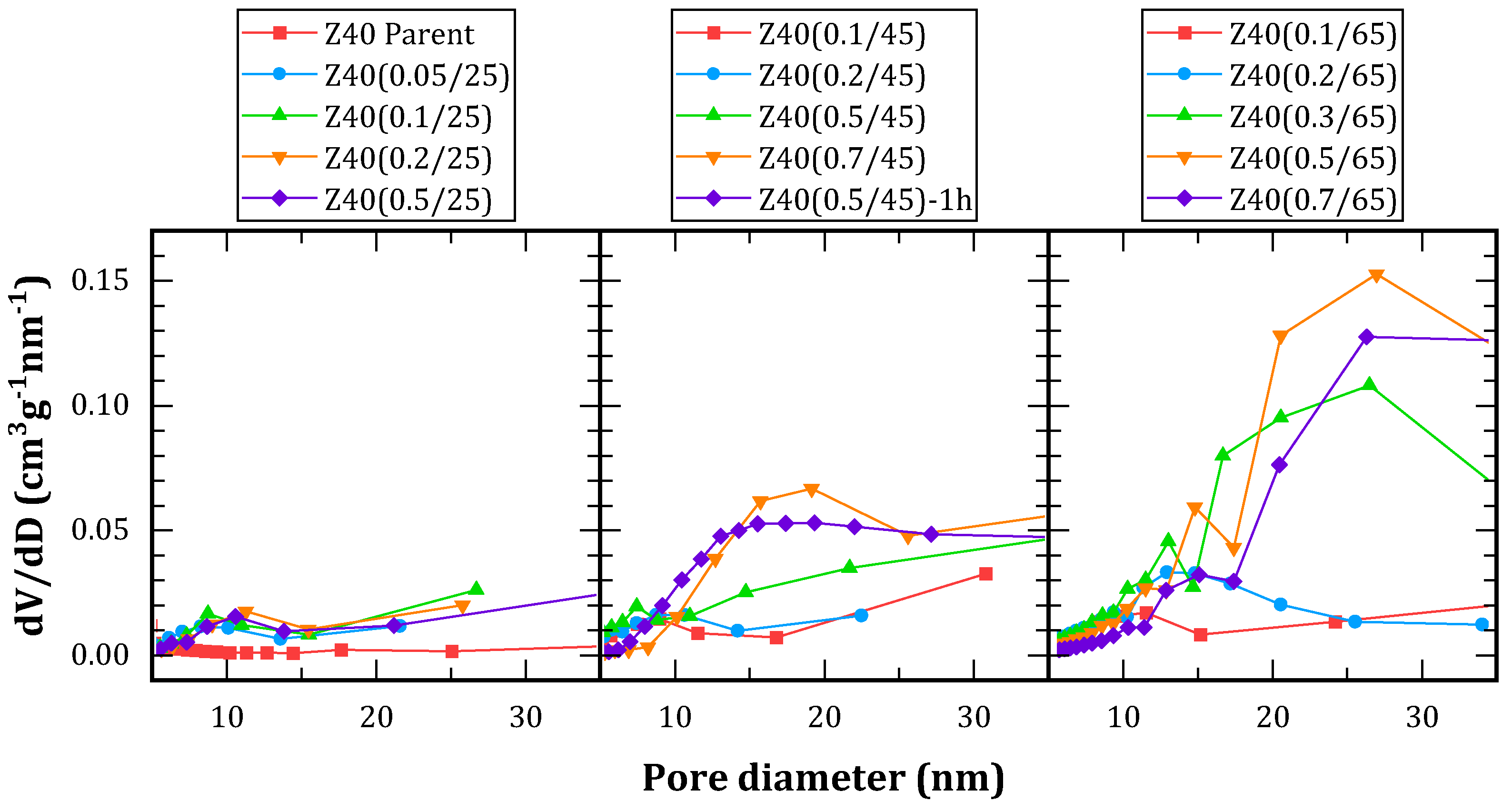

Figure 2 shows the pore-size distributions obtained by BdB method. Treatments conducted at 25 ºC resulted in a poor development of porosity, displaying narrow distributions centered around 9 nm. Conversely, treatments at 65 ºC resulted excessively aggressive towards the framework, leading to broader distributions, characterized by a main peak centered between 20 and 30 nm accompanied by a secondary peak between 10 and 15 nm. Moreover, a loss of material between 75 and 95% was observed during the treatment, indicating the collapse of the framework.

Treatments conducted at 45 ºC were more moderate, with a loss between 45 and 85% of the initial solid. Among them, Z40(0.7/45) and Z40(0.5/45)-1h had the most uniform pore-size distributions.

When comparing Z40(0.5/45) and Z40(0.5/45)-1h, it can be seen that the extended treatment time led to a consistent reduction of the Si/Al ratio (about 40% for every 30 min). This was accompanied by an increment in mesopore volume, without a notable decrement in micropore volume but with a decrement in mesopore area. This would indicate a broadening of the pores, consistent with the distributions shown in

Figure 2. Moreover, the loss of solid increased from 45 % to 67 %.

In general, increments in treatment duration led to pore broadening. The same effect was observed with alkali concentration, but more pronounced. When comparing Z40(0.7/45) and Z40(0.5/45)-1h, the latter presented 80% higher pore volume but only 22% higher surface area. Si/Al ratio is much lower for the latter, indicating a higher desilication. Regarding the temperature of the treatment, it represents a compromise between selectivity for silicon removal and the overall kinetics. Higher temperatures accelerate the generation of mesoporores, but also lead to aluminum removal.

After the alkaline treatments, the acidity of the materials was restored via cationic exchange with NH

4NO

3 in order to recover their catalytic properties.

Table 2 shows the results for selected materials. For comparative purposes, theoretical amounts of acid sites were estimated as a function of Si/Al ratio. The canonic unit cell for MFI framework obeys to the formula H

nAl

nSi

96-nO

192·16H

2O. For every n, Si/Al ratio equals (96 – n)/n and the amount of acid sites (in mmol g

-1) equals 1000n/PM(n), where PM(n) is the formular weight of the unit cell in g mol

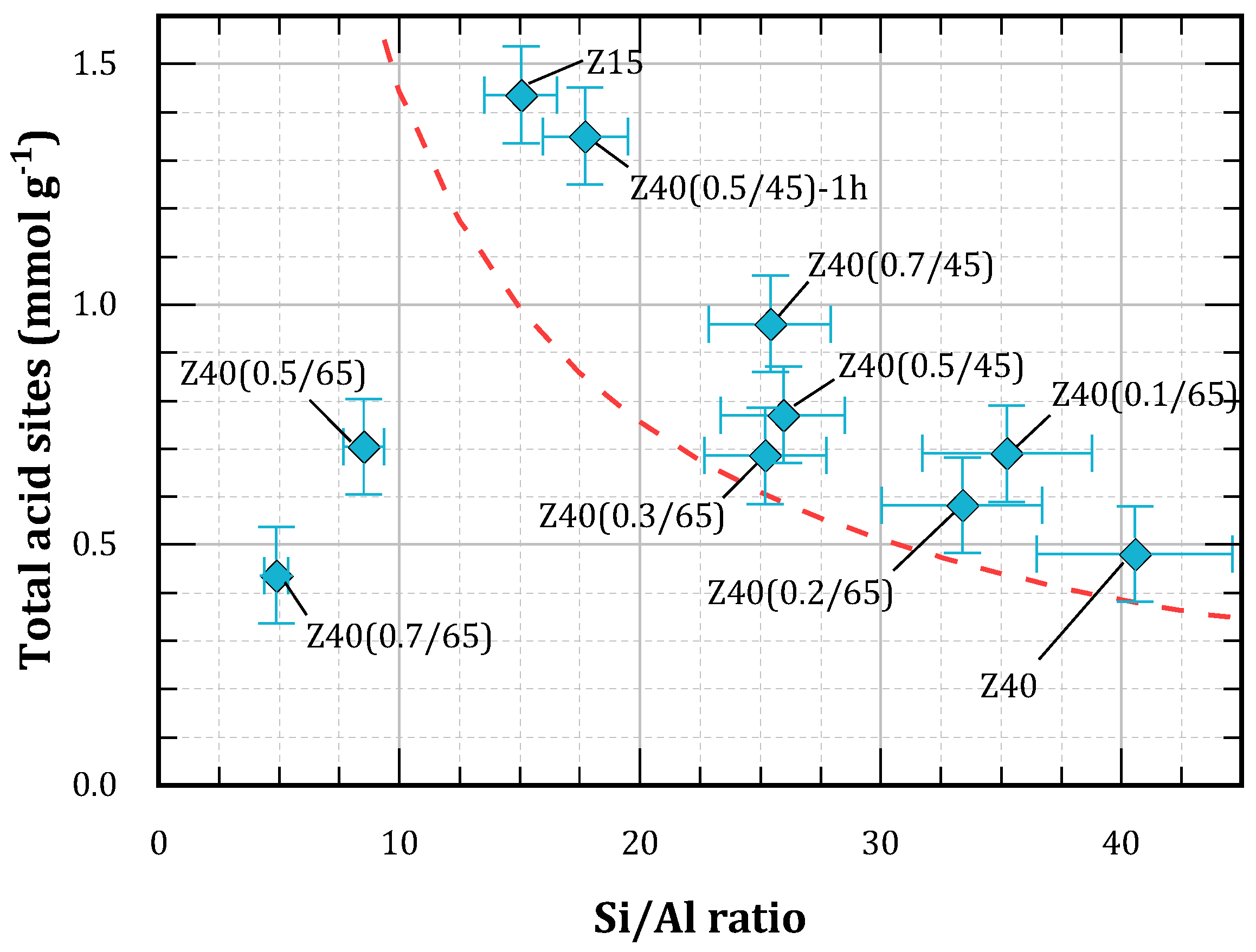

-1, since it is assumed that every framework Al gives one acid site. This theoretical curve was generated for n between 2 and 30, and plotted in

Figure 3, toghether with the values reported for the treated materials in

Table 2.

From

Figure 3 it can be seen that non-treated zeolites as well as those subjected to moderate treatment lie above the theoretical curve. This can be attributted to the presence of framework deffects as well as extra-framework aluminum (EFAL) species. On the other hand, the solids obtained after more severe treatments exhibit lower amounts of acid sites compared with the theoretical curve. Presumably, this is due to the loss of the structure and partial framework collapse, consistent with the cristallinity values obtained by XRD.

3.2. Evaluation of the Accessibility of the Acid Sites

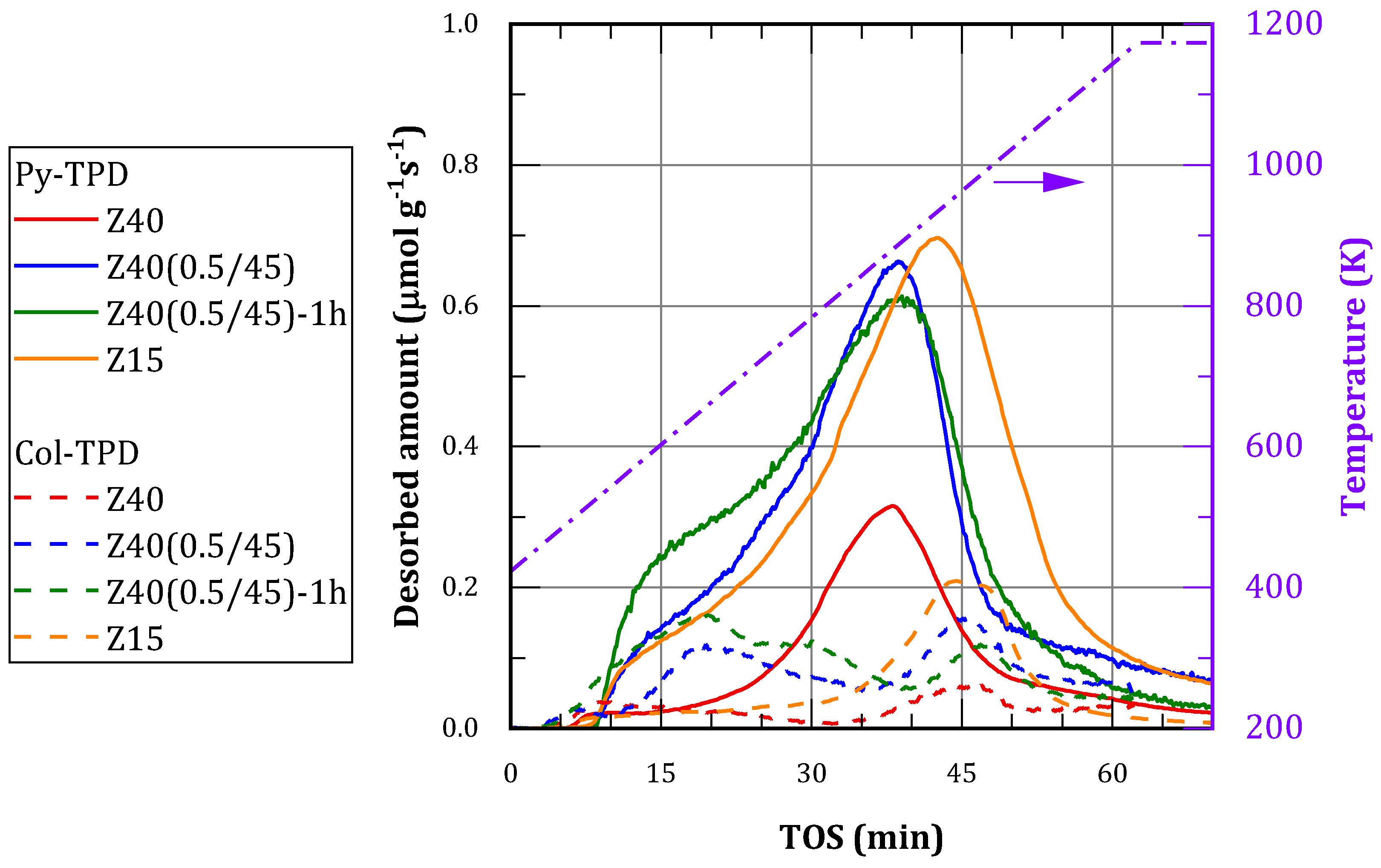

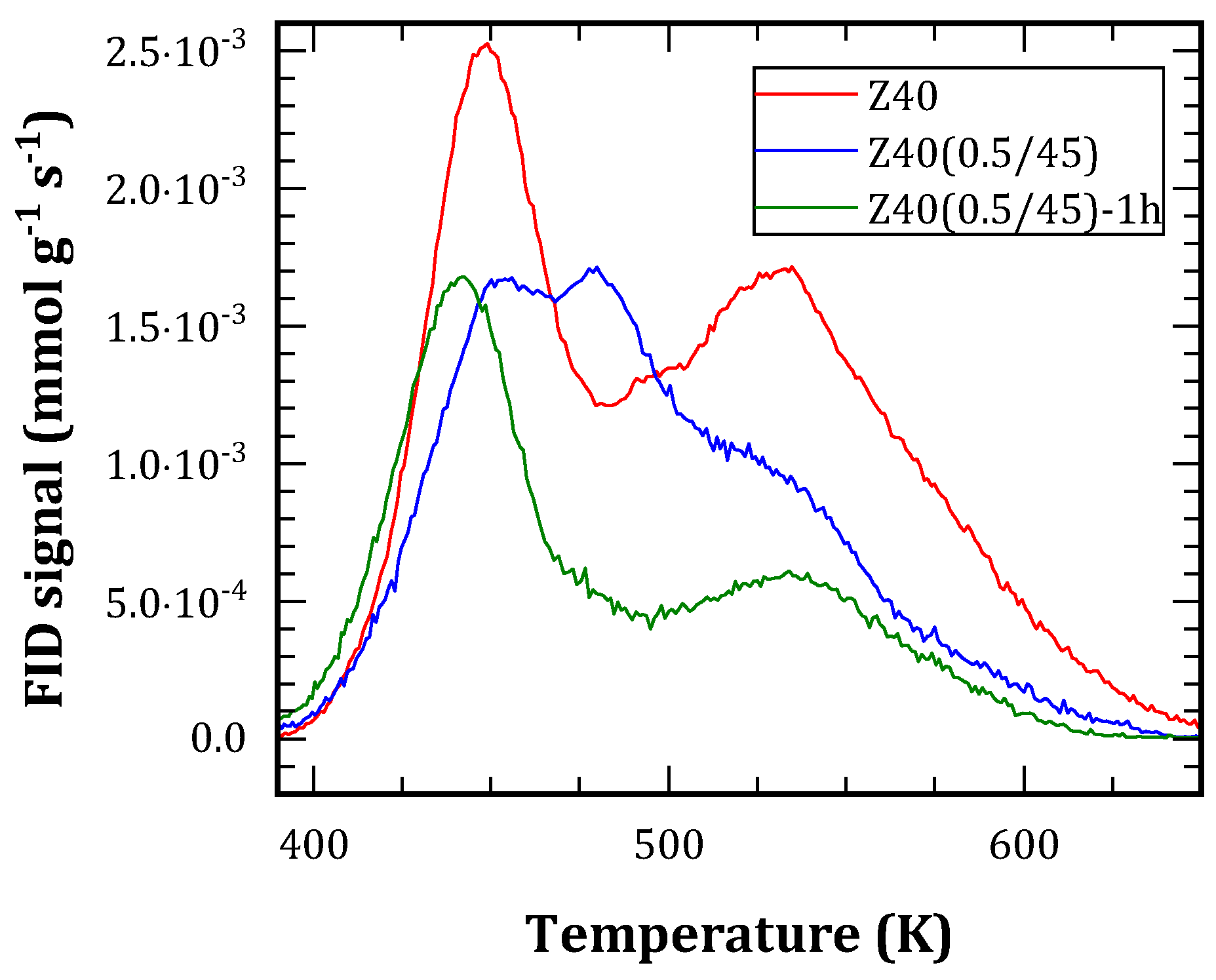

The location and accessibility of the acid sites was studied in order to correlate the catalytic performance with the amount of acid sites and the development of mesoporosity. Two probe molecules were employed for that purpose: pyridine (Py) and collidine (Col). Py has a kinetic diameter about 5.4 Å and is just small enough to diffuse through the micropores of MFI zeolites. Col (2,4,6-trimethylpyridine) has a bigger kinetic diameter (7.4 Å), therefore, it can diffuse through mesopores but it is not able to enter the micropores of the zeolites. The TPD profiles with both probe molecules are presented in

Figure 4. The integration of these profiles results in the amounts of acid sites included in

Table 2, where Py-TPD corresponds to total acid sites and Col-TPD to external acid sites (i.e., those located in the mesopores and the outer area of the particles).

Py-TPD profiles resulted similar in shape, with different magnitude in correspondence with changes in Si/Al ratio. Strong acid sites predominate, with a maximum between 850 and 950 K. There are also considerable amounts of moderate acid sites, seen as a shoulder of the main peak with a center in the range 650-750 K. Finally, there are weak acid sites, associated with a desorption maxima below 550 K.

Since desilication decreases Si/Al ratio and leads to an increment in the amount of acid sites, in order to assess the effect of the treatment on the acidity Z40(0.5/45)-1h is compared with commercial zeolite Z15. Therefore, it was observed that the treated material exhibited a higher proportion of moderate sites and fewer strong sites. The desorption peak is shifted to lower temperatures for Z40(0.5/45)-1h, indicating that sites in Z15 are stronger.

Col-TPD profiles showed that the alkaline treatment increases the amount of accessible acid sites. Despite being most of those weak or moderate acid sites, the amount of accessible strong sites increased as well. The amount of accessible sites in treated zeolites resulted higher than those found in Z15, but the latter are predominantly strong.

The density of external acid sites was computed as the quotient between the amount of acid sites accessible to Col and the external area (

Table 2). This value was diminished after alkaline treatment due to the superposition of two factors: (i) the alkali attacked the surface, affecting its crystallinity and leaching some isolated Al atoms. (ii) the external area increased with the generation of mesopores. Therefore, it can be concluded that the generated mesopores provide additional external area but there is not a significant amount of strong acid sites present.

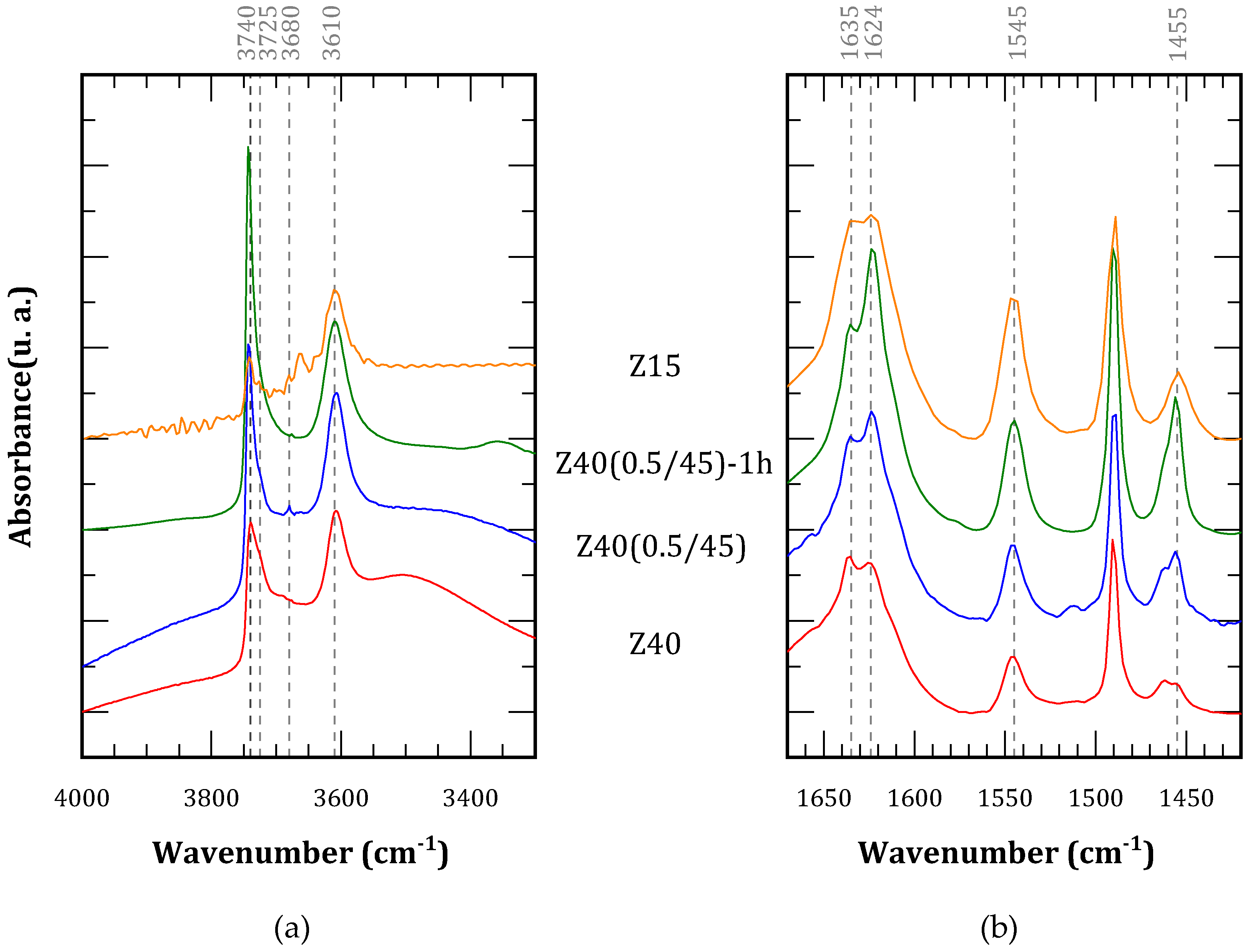

The nature of the acid sites was further explored by infrared spectroscopy.

Figure 5(a) shows the spectra of the activated samples in the OH region. The alkaline treatment leads to a rise in the bands associated with terminal silanols (3740 cm

-1) and nested silanols (3725 cm

-1), as well as the appearance of a small signal at 3680 cm

-1, associated with EFAL [

34]. Therefore, desilication treatment leads to an increment in defect sites, as well as limited removal of Al atoms which later deposit as extra-framework species. The spectra after pyridine adsorption and outgassing are shown in

Figure 5(b). The bands associated with Brønsted acid sites (1635 and 1545 cm

-1) resulted more intense for treated materials than the parent zeolite (Z40), but not as intense as Z15. On the other hand, the bands associated with Lewis acid sites (1624 and 1455 cm

-1) increased sharply in treated materials, and were more intense than Z15. The results of quantification, based on the bands located at 1545 and 1455 cm

-1 are included in

Table 2. Since Lewis acid sites increased more markedly than Brønsted acid sites, the overall result is a decrement in the proportion of the latter, from around 80% in parent material to less than 70% in treated materials Z40(0.5/45) and Z40(0.5/45)-1h.

3.3. Dynamic Adsorption Experiments

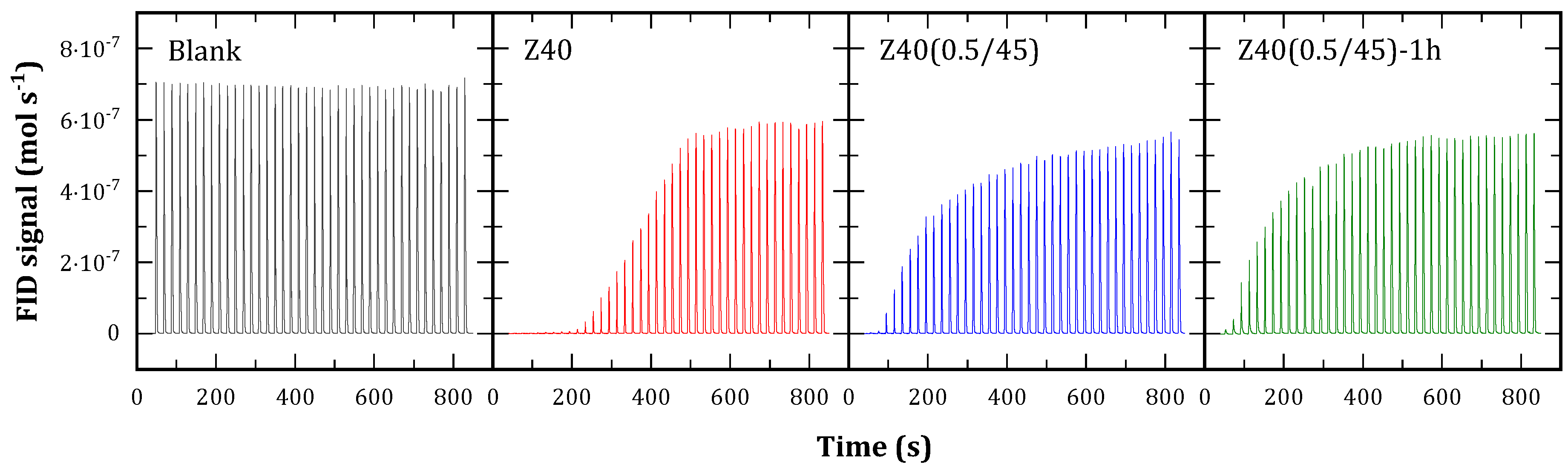

The interaction of the solid with one reactant (1-butene) was analyzed by dynamic adsorption. The experiments consisted in trains of pulses of 1-butene sent to a cell at 110 °C loaded with catalyst while, the outlet was monitored by FID. The results are presented in

Figure 6. Z40 adsorbs the pulses completely for the first 200 s, and then reducing the uptake until saturation. Z40(0.5/45) and Z40(0.5/45)-1h adsorbed 1-butene more slowly, indicating comparatively weaker acid sites. This agrees with previous results [

33,

35]. Once stabilized, the amplitude of the peaks is lower than the blank test due to a widening, caused by the diffusion of the reactant through the solid. The integration of the profiles shows that Z40 adsorbed 3.56 mmol of butene per gram of solid, while Z40(0.5/45) and Z40(0.5/45)-1h adsorbed 1.93 and 1.99 mmol g

-1, respectively.

After the equilibration of the catalyst with 1-butene, a TPD was performed yielding the profiles shown in

Figure 7. They present three main contributions, which are assigned as:

425-450 K: butenes, being possible the isomerization of 1-butene.

450-525 K: light olefins, from polymerization reactions.

500-575 K: species released from coke, coincident with those observed typically in TPO experiments.

The total desorbed species represented between 30 and 50% of the adsorbed 1-butene considering the carbon atoms. Therefore, there is coke remaining on the solids, which is not released due to the use of N2 as carrier gas.

Regarding the profiles, treated materials were less acidic, thus adsorbed less 1-butene and, consequently, presented smaller desorption as well. In relative terms, the high-temperature contribution was reduced. This can be attributed to a lower ability to crack the coke precursors due to their weaker acid sites.

3.4. Catalytic Evaluation

3.4.1. Isobutane/1-Butene Alkylation

The catalysts were tested for the alkylation of isobutane with butenes in gas phase. Although 1-butene was employed as a reactant, it can undergo rapid isomerization to cis- and trans-2-butene. Both isomers were detected among the products, and therefore they can act as alkylating agents.

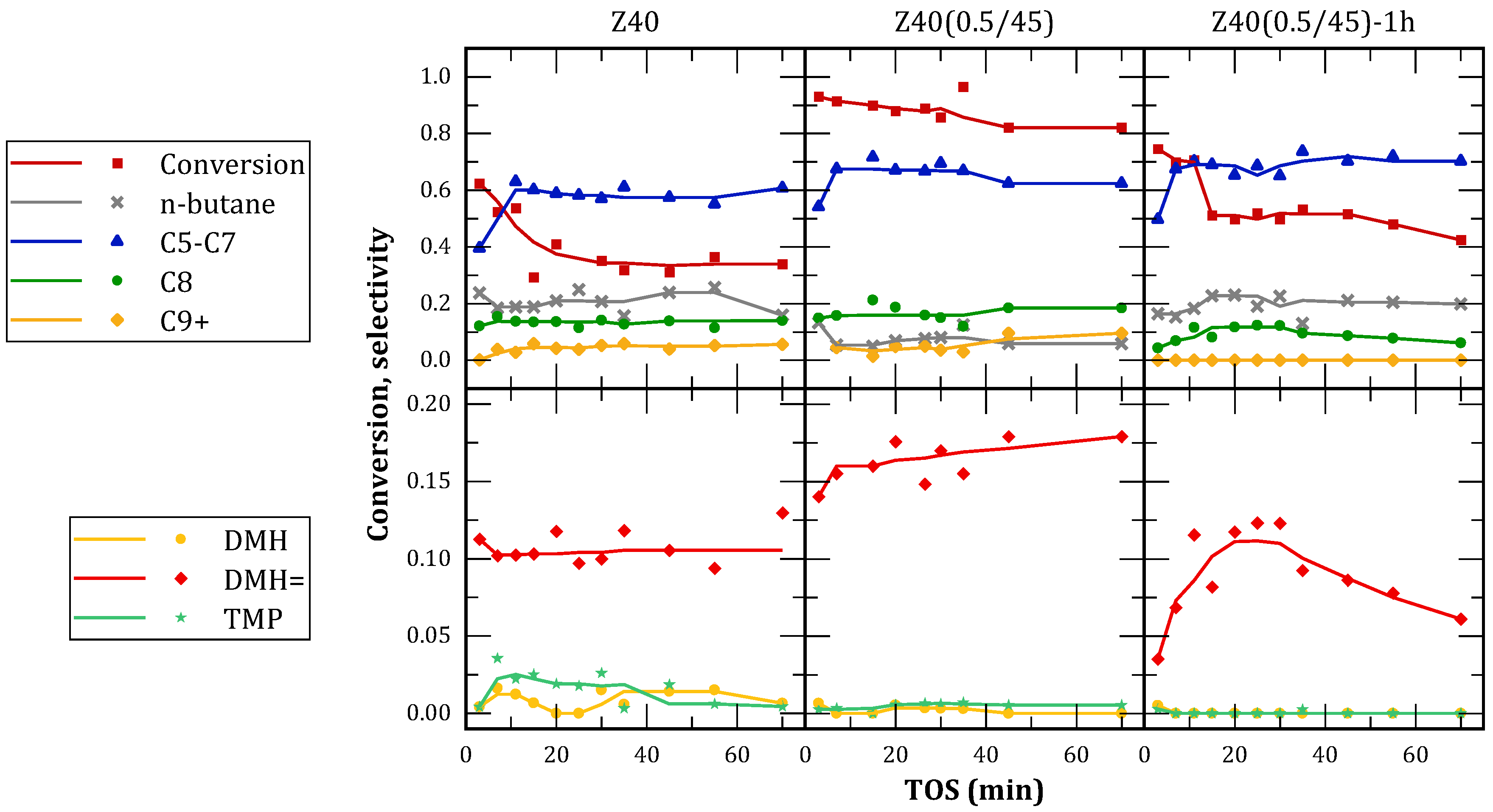

The results of butenes conversion and selectivity to different hydrocarbon fractions as a function of time on stream (TOS) are shown in

Figure 8. All catalysts presented a reduction of conversion with TOS, due to deactivation caused by coke deposition. However, the treated catalysts showed delayed deactivation and higher residual activity after deactivation. This behavior is attributed to their mesoporous structure, which facilitated the diffusion of coke precursors, as well as preventing pore-mouth blocking by providing alternate routes for reactants and products. Z40(0.5/45) also provided a higher initial conversion (over 90%), indicating a good proportion of strong acid sites. This material presented lower coke deposition at the end of the reaction, likely due to the enhanced diffusion of coke precursors. Z40(0.5/45)-1h presented an intermediate behavior between the latter and the parent zeolite, indicating that the extension of the alkaline treatment was detrimental for the catalytic activity.

MFI zeolites have been previously studied for this reaction, resulting in low yields to trimethylpentanes (TMP) due to their channel structure [

25]. In this case, it is observed that the selectivity of the parent zeolite is replicated by the treated catalysts: In the C5+ fraction there is a predominance of C5-C7 products, formed by oligomerization followed by cracking. Approximately 10-20% of C8 compounds were obtained, almost entirely DMH=. The presence of these compounds suggests a predominance of butene dimerization, and a low hydride transfer activity. The observed DMH= compounds are responsible of the formation of C9+ hydrocarbons, that act as coke precursors.

As mentioned above, the microporous channels in MFI zeolites impose steric hindrances that limit the formation of multibranched compounds. Consequently, Z40 was more selective towards dimerization and polymerization reactions, while the formation of TMP was hindered. Treated materials presented similar product distributions, therefore, no contribution of the mesopores was observed to the formation of TMP. These results suggest, in agreement with accessibility tests, that the generated mesopores by alkaline treatment do not have active sites for this reaction on their surface. These results agree with those obtained by Sazama et al. [

36], who studied n-hexane isomerization and found that shape-selectivity in zeolites was not affected by secondary mesoporosity.

Particularly, the parent material Z40 produced the highest proportion of TMP, which is attributed to the presence of accessible strong sites located at the pore-mouths. After the alkaline treatment, these sites close to the external surface were attacked and consequently lost. The remaining accessible sites are then weak and presumably, Lewis acid sites associated with EFAL originated by redeposition of removed aluminum.

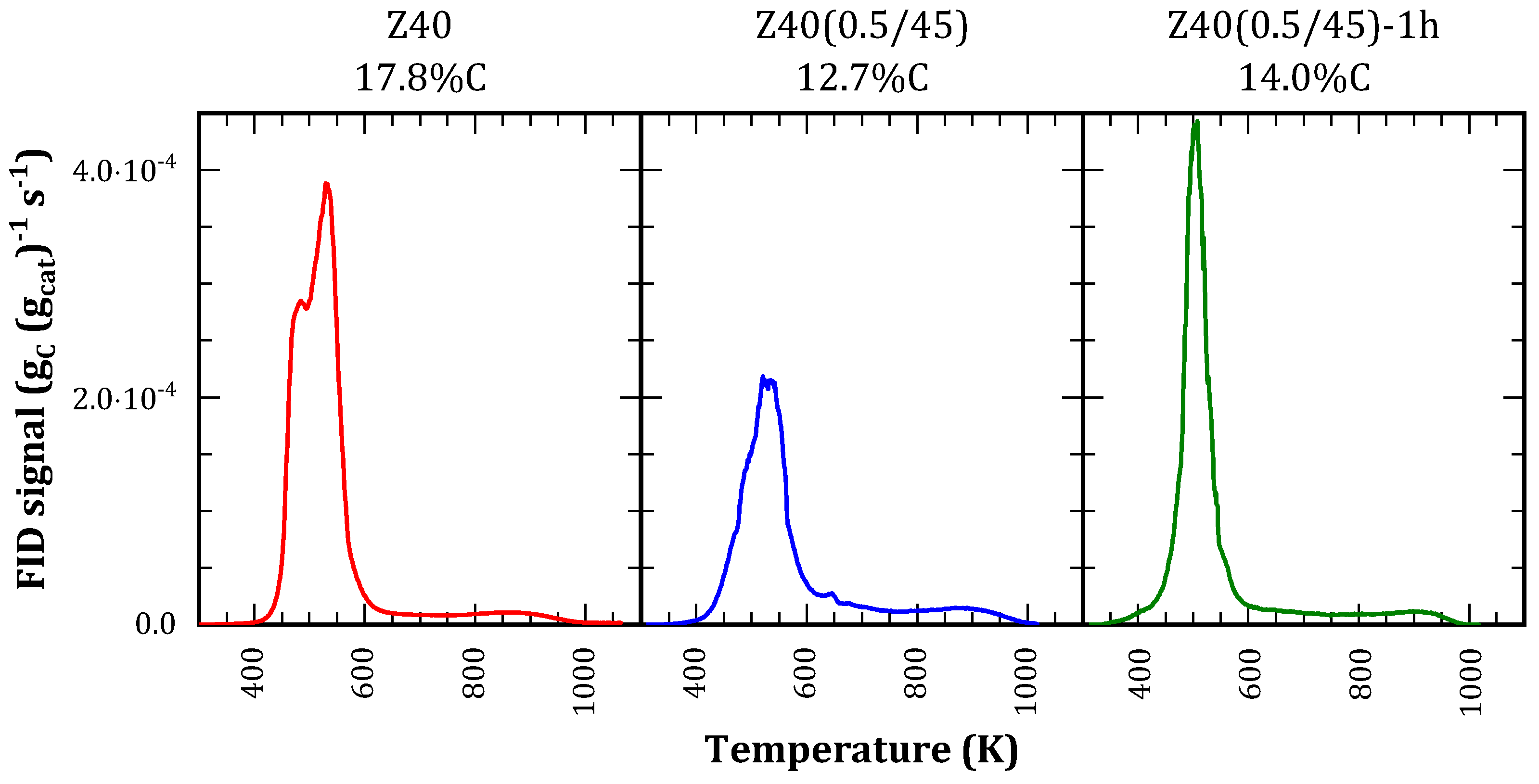

TPO profiles (

Figure 9) presented two distinctive regions, corresponding to alifatic coke (300-650 K) and aromatic coke (650-1000 K). The latter is produced by an aromatization process during the analysis [

32], and it represents a minor contribution to the profile. Higher amounts indicate the presence of strong acid sites and a more efficient use of the catalyst surface, as observed in FAU zeolites [

37].

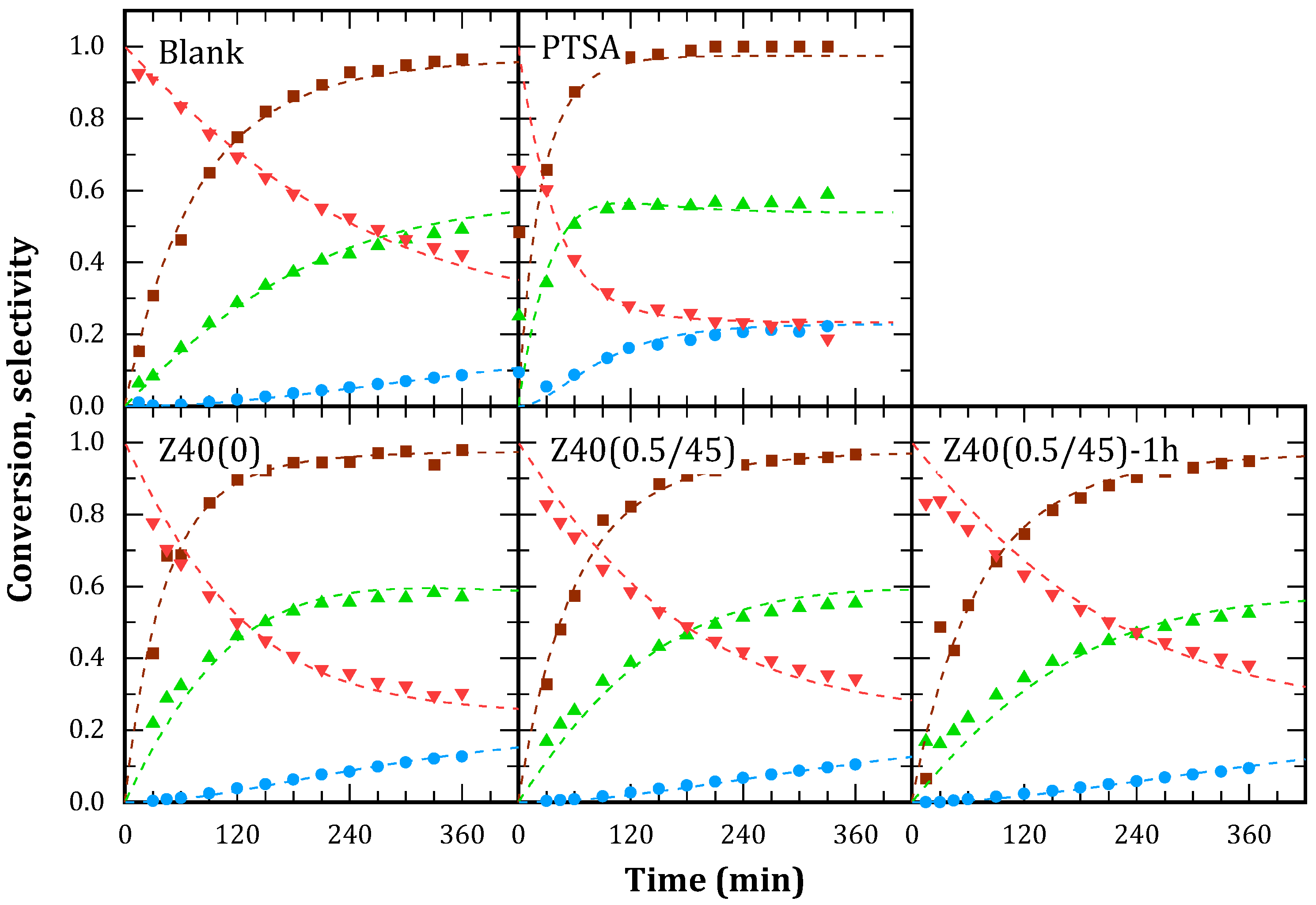

3.4.2. Glycerol Esterification with Acetic Acid

The catalysts were also tested for the esterification of glycerol with acetic acid to obtain mono-, di- and triacetin (MA, DA and TA, respectively). This reaction takes place under different conditions than the alkylation reaction (liquid phase, polar reactants) but requires as well acid sites and large pores due to the increasing kinetic diameter of the successive products. Therefore, a contrast is provided regarding the effect of the alkaline treatment and the generation of mesopores.

Glycerol conversion and selectivities to MA, DA and TA are shown in

Figure 10 for the catalysts and the blank test, since there is an intrinsic reaction rate between the reactant in absence of catalyst. As a comparison, the reaction with a homogeneous strong acid (p-toluenesulfonic acid, PTSA) is provided.

Blank test reached 90% glycerol conversion after 4 h, yielding predominantly MA. After 6 h, DA selectivity was 50% and TA, 10%. PTSA (added in a quantity equivalent to the acid sites of the average of the solids) reached 90% glycerol conversion in 1 h and selectivities equilibrated after 6 h, with the proportion MA:DA:TA around to 23:55:22.

Solid catalysts reported similar yields to the blank test. Particularly, higher initial reaction rates were observed and the crossing point of MA and DA selectivities shifted to lower reaction times. TA selectivity curves did not present significant changes. Overall, this would indicate a catalytic effect on the first stage of the reaction, with some effect on the second stage by equilibrium displacement.

4. Discussion

The generation of mesopores by alkaline treatment, while preserving parent material crystallinity, is only possible within narrow ranges of alkali concentration and temperature, and with a limited duration. Under adequate conditions, pores with diameters around 10 nm were formed, and mesopore volume increased by 300%. The amount of acid sites increased due to selective removal of silicon atoms. Nonetheless, desorption of bases of different kinetic diameters revealed that these mesopores lack active sites on their surface, which are partially amorphized due to alkali attack. Additionally, some aluminum is incidentally removed during treatment and redeposits in the mesopores as EFAL, originating accessible weak Lewis acid sites.

The lack of moderate and strong Brønsted acid sites in the mesopores confines catalytic activity to preexistent micropores. Therefore, shape selectivity of the parent zeolite is preserved in treated materials, as it was demonstrated for the alkylation of isobutane with butenes. Pore sizes plays a key role in selectivity to different C8 products in this reaction, and the materials yielded only dimerization products, since they could not accommodate the bulky intermediate state required for the hydride transfer. This conclusion was further supported by the study of esterification of glycerol with acetic acid, where the solids lacked catalytic activity due to steric hindrances in the micropores. However, in the first case, the existence of mesopores allowed a better diffusion of coke precursors. Therefore, coke deposition was delayed, pore blocking was avoided, and catalytic activity was preserved, increasing the stability of the catalyst for the alkylation reaction system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.G.T. and B.D.C.; methodology, L.G.T.; formal analysis, L.G.T, L.V., B.D.C and C.A.Q; investigation, L.G.T. and L.V.; resources, B.D.C and C.A.Q.; data curation, L.G.T.; writing—original draft preparation, L.G.T.; writing—review and editing, B.D.C.; visualization, L.G.T.; supervision, C.A.Q.; project administration, B.D.C and C.A.Q.; funding acquisition, B.D.C and C.A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANPCyT, project PICT 2018-0364; CONICET project PIP 2022-0345; and Universidad Nacional del Litoral, project CAI+D 2020 50620190100153LI.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bai, R.; Song, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, J. , Creating Hierarchical Pores in Zeolite Catalysts, Trends Chem 2019, 1, 601–611. 1,. [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.P.; Escola, J.M.; Pizarro, P. , Synthesis strategies in the search for hierarchical zeolites, Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42, 4004–4035. 42,. [CrossRef]

- Schwieger, W.; Machoke, A.G.; Weissenberger, T.; Inayat, A.; Selvam, T.; Klumpp, M.; Inayat, A. , Hierarchy concepts: classification and preparation strategies for zeolite containing materials with hierarchical porosity, Chem Soc Rev 2016, 45, 3353–3376. [CrossRef]

- Tzoulaki, D.; Jentys, A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J.; Egeblad, K.; Lercher, J.A. ; On the location, strength and accessibility of Bronsted acid sites in hierarchical ZSM-5 particles, Catal Today 2012, 198, 3–11. 198,. [CrossRef]

- Rownaghi, A.A.; Hedlund, J. , Methanol to gasoline-range hydrocarbons: Influence of nanocrystal size and mesoporosity on catalytic performance and product distribution of ZSM-5, Ind Eng Chem Res 2011, 50, 11872–11878. [CrossRef]

- Sammoury, H.; Toufaily, J.; Cherry, K.; Hamieh, T.; Pouilloux, Y.; Pinard, L. , Desilication of *BEA zeolites using different alkaline media: Impact on catalytic cracking of n-hexane, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2018, 267, 150–163. 267,. [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.; Sohrabi, M.; Falamaki, C. , Improvement of HZSM-5 performance by alkaline treatments: Comparative catalytic study in the MTG reactions, Fuel 2014, 116, 529–537. 116,. [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.B.; Neto, M.M.S.; Oliveira, D.S.; Santos, A.G.D.; Souza, L.D.; Caldeira, V.P.S. , Obtainment of hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolites by alkaline treatment for the polyethylene catalytic cracking, Advanced Powder Technology 2021, 32, 515–523. 32,. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.V.; Vignatti, C.; Garetto, T.; Pulcinelli, S.H.; Santilli, C.V.; Martins, L. , Glycerol dehydration catalyzed by MWW zeolites and the changes in the catalyst deactivation caused by porosity modification, Appl Catal A Gen, 2015, 495, 84–91. 495,. [CrossRef]

- Mardiana, S.; Azhari, N.J.; Ilmi, T.; Kadja, G.T.M. , Hierarchical zeolite for biomass conversion to biofuel: A review, Fuel 2022, 309, 122119. 309,. [CrossRef]

- Kokotailo, G.T.; Jr, A.C.R. , Method for purifying zeolitic material, US Patent 4703025, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, G.; Okura, T.; Goto, K. , Properties of silica in water, Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1957, 12, 123–132. 12,. [CrossRef]

- Iler, R.K. , The Chemistry of Silica: Solubility, Polymerization, Colloid and Surface Properties and Biochemistry of Silica, Wiley, New York, 1979. https://www.wiley.com/en-ar/The+Chemistry+of+Silica:+Solubility,+Polymerization,+Colloid+and+Surface+Properties+and+Biochemistry+of+Silica-p-9780471024040.

- Dessau, R.M.; Valyocsik, E.W.; Goeke, N.H. , Aluminum zoning in ZSM-5 as revealed by selective silica removal, Zeolites 1992, 12, 776–779. 12,. [CrossRef]

- Ogura, M.; Shinomiya, S.Y.; Tateno, J.; Nara, Y.; Kikuchi, E.; Matsukata, M. , Formation of uniform mesopores in ZSM-5 zeolite through treatment in alkaline solution, Chem Lett 2000, 882–883. [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Jansen, J.C.; Moulijn, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. , Optimal aluminum-assisted mesoporosity development in MFI zeolites by desilication, Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2004, 108, 13062–13065. [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Moulijn, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. , Alkaline posttreatment of MFI zeolites. From accelerated screening to scale-up, Ind Eng Chem Res 2007, 46, 4193–4201. 46,. [CrossRef]

- Groen, J.C.; Moulijn, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. , Decoupling mesoporosity formation and acidity modification in ZSM-5 zeolites by sequential desilication-dealumination, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2005, 87, 153–161. 87,. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wilkinson, L.; Ogunde, L.; Todd, R.; Steves, C.; Haydel, S. , Alkylation Technology Study FINAL REPORT for South Coast Air Quality Management District (SCAQMD), California, USA., 09/09/2016.

- Albright, L.F.; In, A.-I.; Catalysis, E.O.; Howath, I.T.; Wiley, J. ; Inc.; Hoboken; USA, 2010: pp. 226–281. [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, T.; Nishimura, T.; Watanabe, H.; Na, K.; Misono, M. , 4.8 Novel Catalysis of Cesium Salt of Heteropoly Acid and its Characterization by Solid-state NMR, Stud Surf Sci Catal 1994, 90, 419–428. 90,. [CrossRef]

- Essayem, N.; Kieger, S.; Coudurier, G.; Védrine, J.C. , Comparison of the reactivities of H3PW12O40 and H4SiW12O40 and their K+, NH4+ and Cs+ salts in liquid phase isobutane/butene alkylation, Stud Surf Sci Catal 1996, 101, 591–600. 101,. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liao, S.; Qian, Z.; Tanabe, K. , Alkylation of isobutane with butenes over solid acid catalysts, Appl Catal A Gen 1994, 107, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Corma, A.; Juan-Rajadell, M.I.; López-Nieto, J.M.; Martinez, A.; Martínez, C. , A comparative study of O42− /ZrO2 and zeolite beta as catalysts for the isomerization of n-butane and the alkylation of isobutane with 2-butene, Appl Catal A Gen 1994, 111, 175–189. 111,. [CrossRef]

- Corma, A.; Martinez, A.; Martinez, C. , Isobutane/2-butene alkylation on MCM-22 catalyst. Influence of zeolite structure and acidity on activity and selectivity, Catal Letters 1994, 28, 187–201. 28,. [CrossRef]

- Flego, C.; Galasso, L.; Kiricsi, I.; Clerici, M.G. ; TG-DSC, UV-VIS-IR Studies on Catalysts Deactivated in Alkylation of Isobutane with 1-Butene, Stud Surf Sci Catal 1994, 88, 585–590. 88,. [CrossRef]

- Unverricht, S.; Ernst, S.; Weitkamp, J. , Iso-Butane/1-Butene Alkylation on Zeolites Beta and MCM-22, Stud Surf Sci Catal 1994, 84, 1693–1700. 84,. [CrossRef]

- Stöcker, M.; Mostad, H.; Rørvik, T. , Isobutane/2-butene alkylation on faujasite-type zeolites (H EMT and H FAU), Catal Letters 1994, 28, 203–209. 28,. [CrossRef]

- Rørvik, T.; Mostad, H.; Ellestad, O.H.; Stöcker, M. , Isobutane/2-butene alkylation over faujasite type zeolites in a slurry reactor. Effect of operating conditions and catalyst regeneration, Appl Catal A Gen 1996, 137, 235–253. 137,. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.F.; Chester, A.W. , Reactions of isobutane with butene over zeolite catalysts, Zeolites 1986, 6, 195–200. 6,. [CrossRef]

- Weitkamp, J. , Isobutane/Butene Alkylation on Cerium Exchanged X and Y Zeolites, Stud Surf Sci Catal 1980, 5, 65–75. 5,. [CrossRef]

- Querini, C.A.; Roa, E. , Deactivation of solid acid catalysts during isobutane alkylation with C4 olefins, Appl Catal A Gen 1997, 163, 199–215. 163,. [CrossRef]

- Tonutti, L.G.; Decolatti, H.P.; Querini, C.A.; Costa, B.O.D. , Hierarchical H-ZSM-5 zeolite and sulfonic SBA-15: The properties of acidic H and behavior in acetylation and alkylation reactions, Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2020, 305, 110284. , 305,. [CrossRef]

- Karge, H.G. , Characterization by IR spectroscopy. In Verified Syntheses of Zeolitic Materials; H. Robson, K.P. Lillerud, Eds.; Elsevier Science, 2001, pp. 69–71. [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.O.D.; Querini, C.A. , Isobutane alkylation with solid catalysts based on beta zeolite, Appl Catal A Gen 2010, 385, 144–152. 385,. [CrossRef]

- Sazama, P.; Pastvova, J.; Kaucky, D.; Moravkova, J.; Rathousky, J.; Jakubec, I.; Sadovska, G. , Does hierarchical structure affect the shape selectivity of zeolites? Example of transformation of n-hexane in hydroisomerization, J Catal 2018, 364, 262–270. 364,. [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.O.D.; Querini, C.A. , Isobutane alkylation with butenes in gas phase, Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 162, 829–835. 162. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).