Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of the Feedstock

2.2. Preparation of the Adsorbent

2.2.1. Thermal Activation of Red Mud

2.2.2. Chemical Activation of Red Mud

2.3. Characterization of Adsorbents

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) - Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis (EDX)

2.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.3. X-ray Diffusion

2.3.4. Surface and Textural Characterization

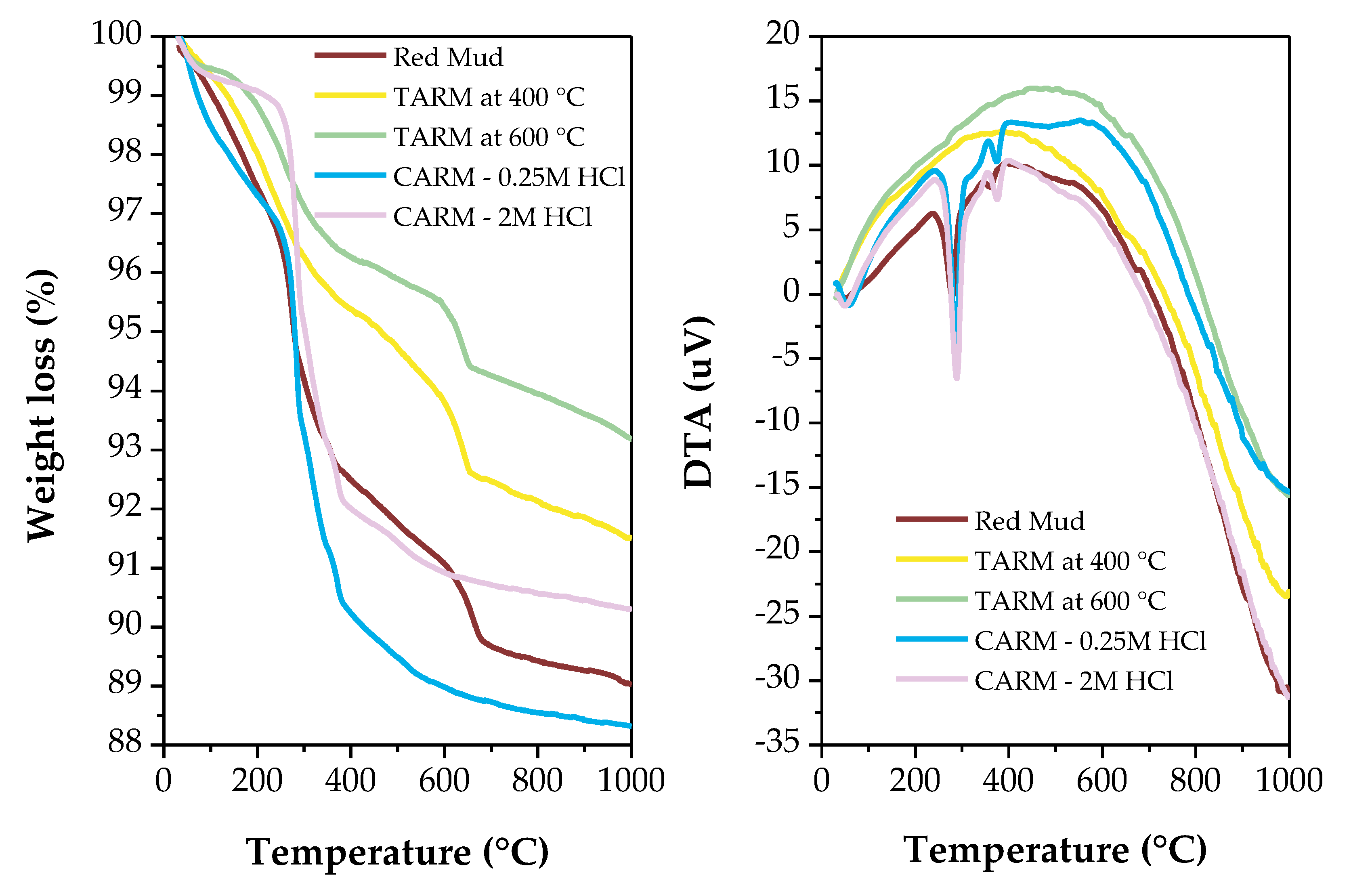

2.3.5. Thermal Analysis

2.4. Experimental Procedure for the Adsorption of Carboxylic Acids

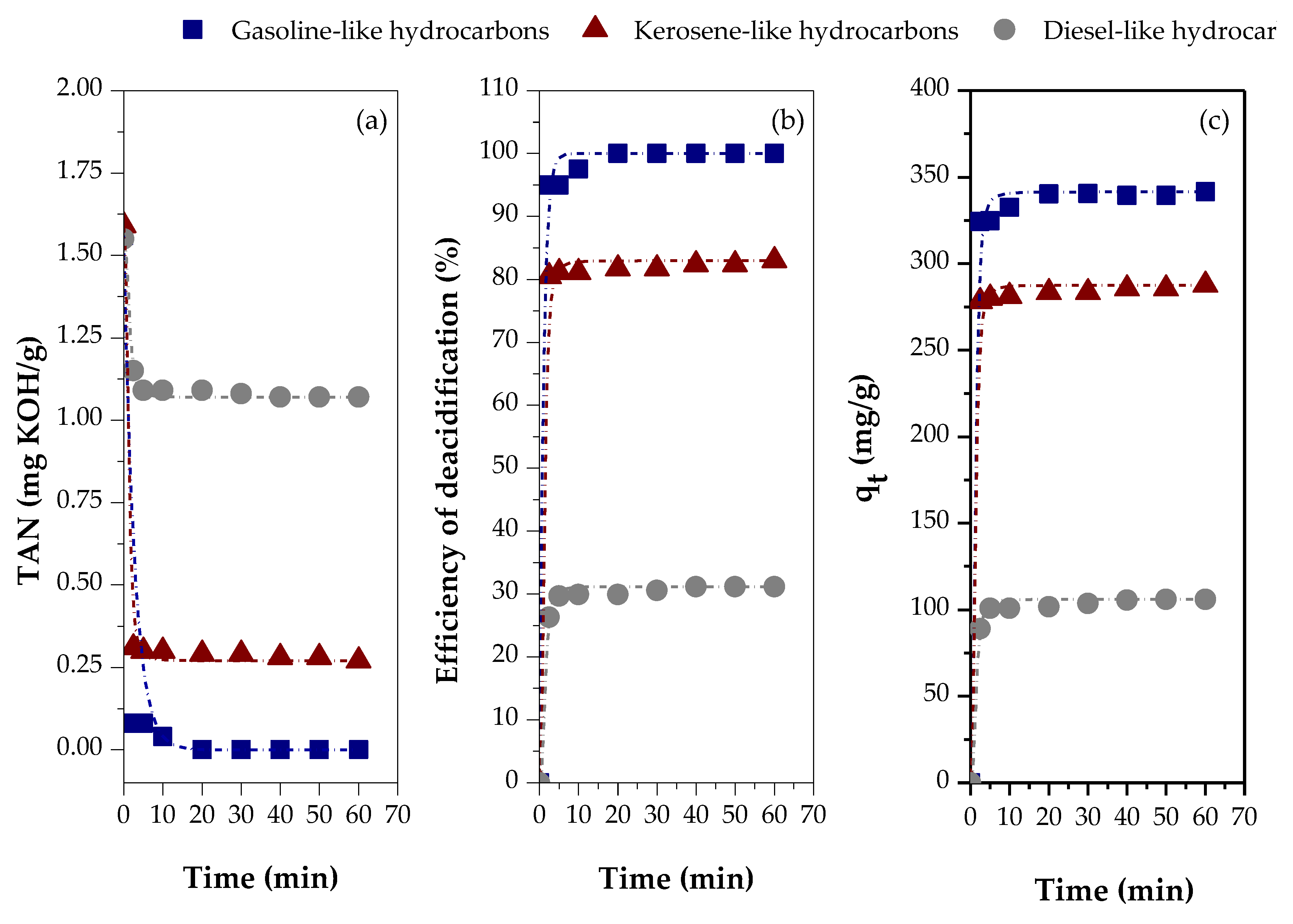

2.4.1. Effect of the Type of Feedstock

- gasoline-like hydrocarbons (cut-off temperature range: 90-160 °C; TAN = 1.56 mg KOH/g)

- kerosene-like hydrocarbons (cut-off temperature range: 160-245 °C; TAN=1.59 mg KOH/g)

- diesel-like hydrocarbons (cut-off temperature range: 245-340 °C; TAN = 1.55 mg KOH/g)

2.4.2. Effect of the Adsorbent

2.4.3. Effect of Free Fatty Acid Content on Feedstock

2.4.4. Effect of Adsorbent Amount

2.4.5. Effect of Activation Temperature

2.4.6. Effect of Acid Solution Concentration

2.4.7. Adsorption Kinetics

2.5. Kinetic Modeling

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Adsorbents

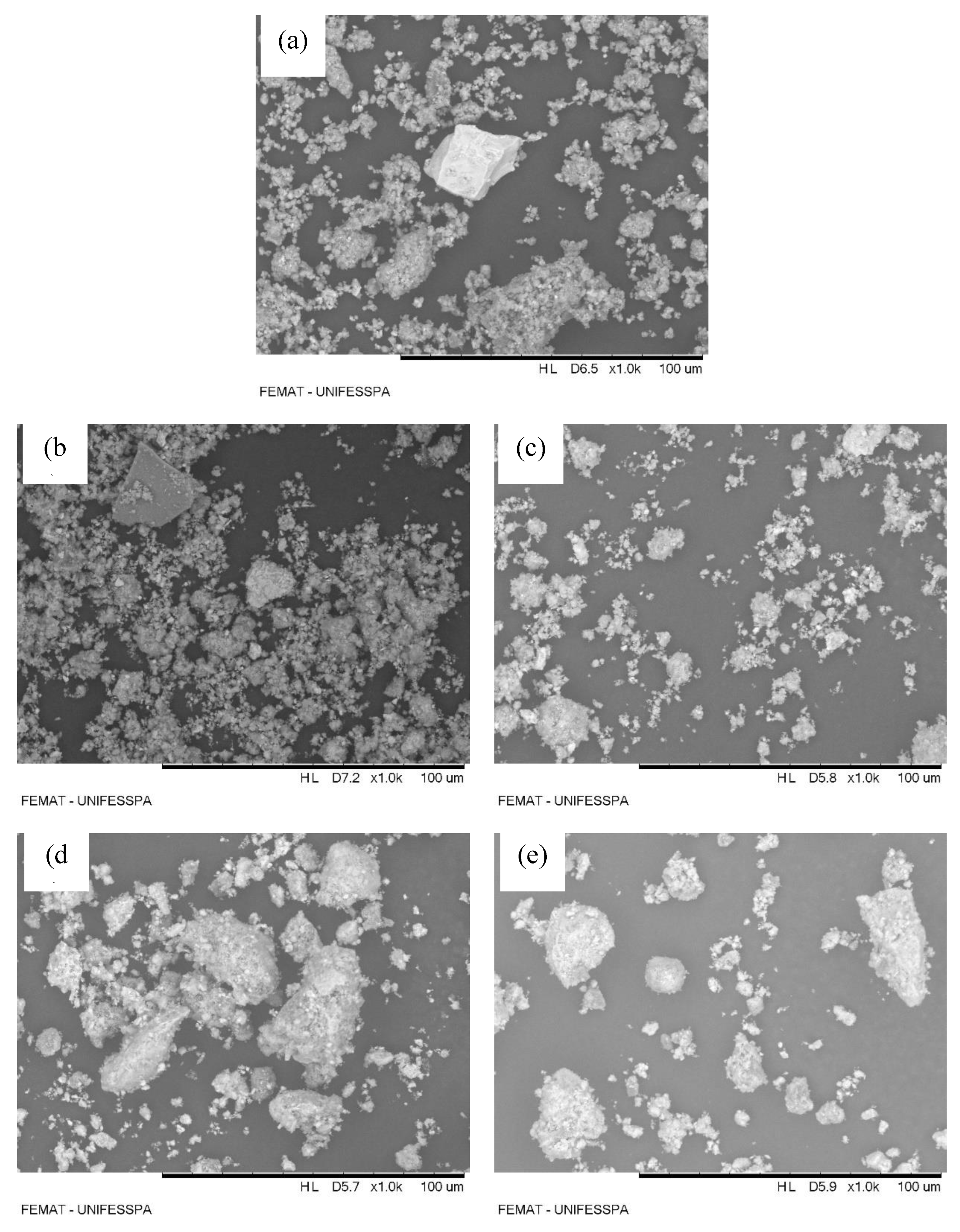

3.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) - Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis (EDX)

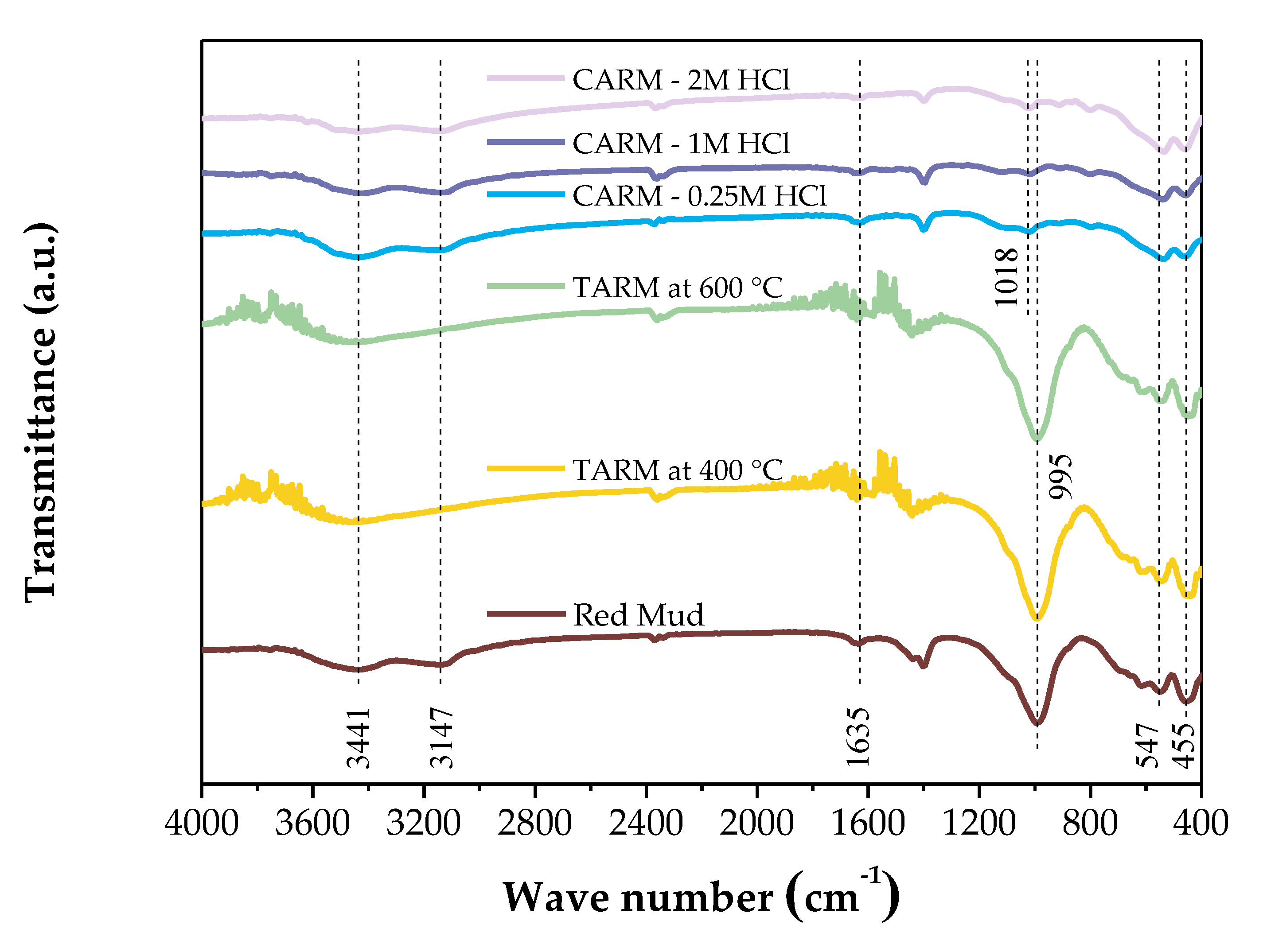

3.3.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

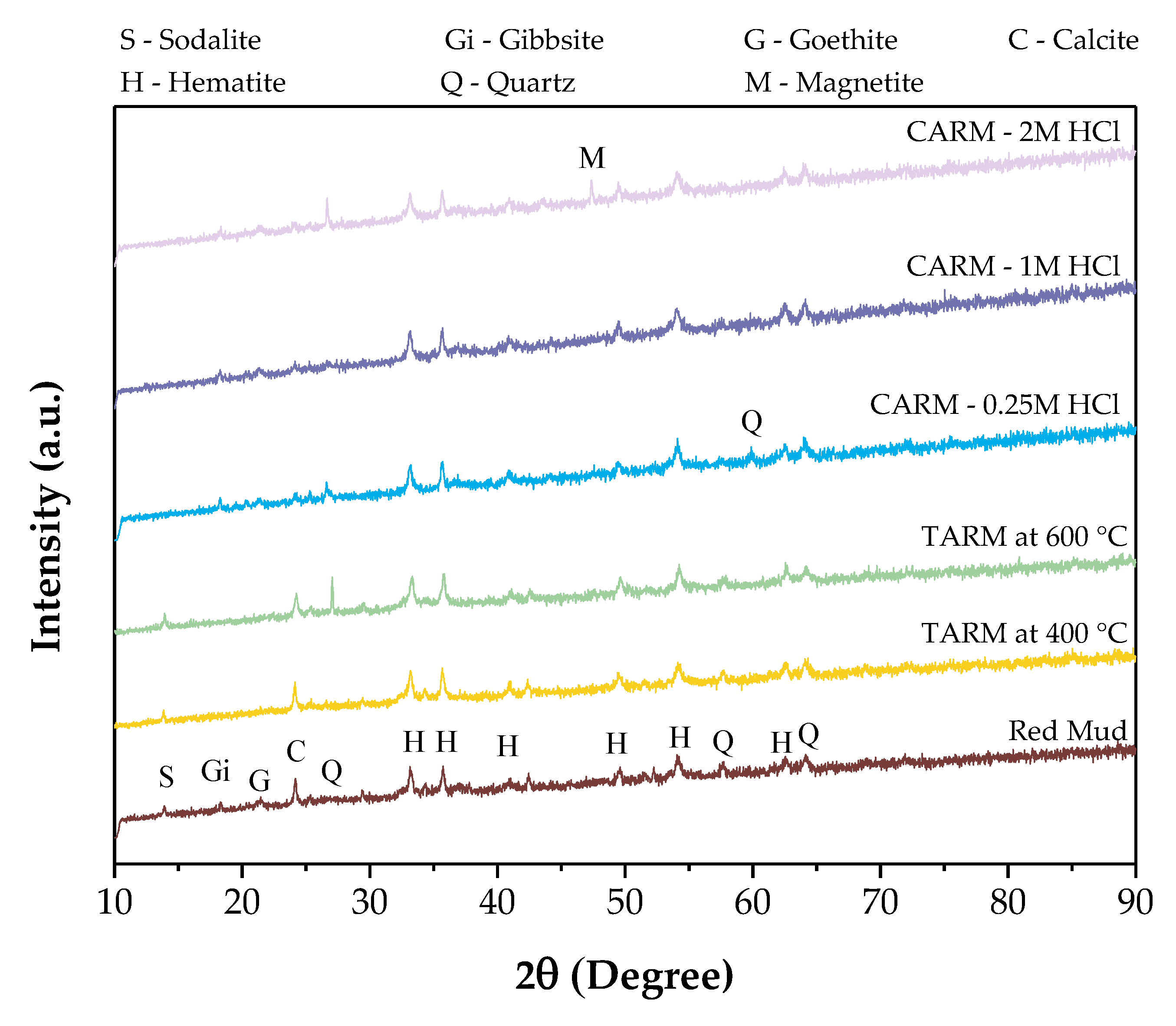

3.3.3. X-ray Diffusion (XRD)

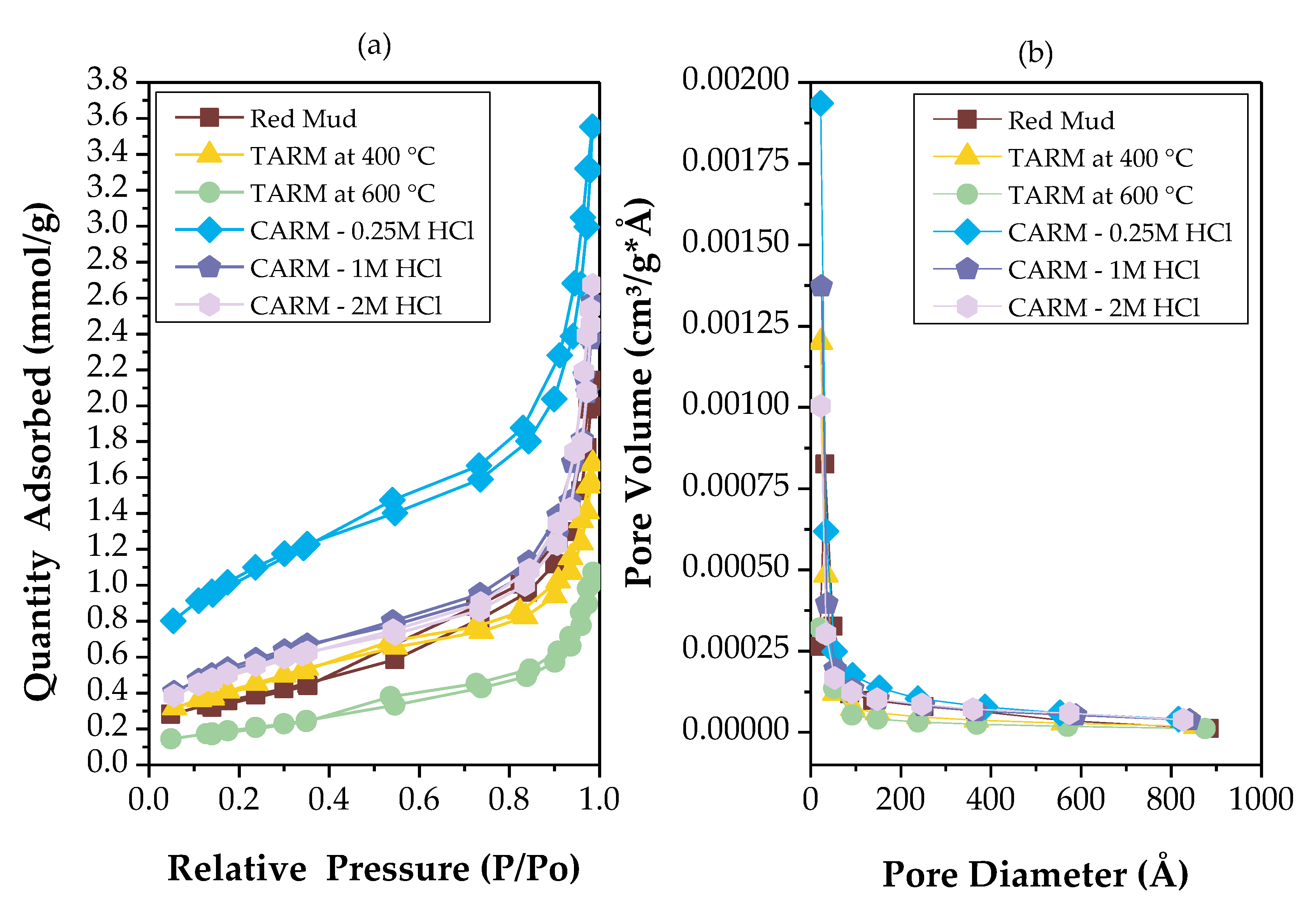

3.3.4. Surface and Textural Characterization

| Specific area (BET) | Volume of mesopores (BJH desorption) |

Average pore diameter (BJH desorption) |

|

| m2/g | cm3/g | Å | |

| Red Mud | 29.7024 | 0.075554 | 78.099 |

| TARM at 400 °C | 35.2450 | 0.060928 | 58.565 |

| TARM at 600 °C | 16.0152 | 0.037911 | 68.464 |

| CARM - 0.25M HCl | 84.3290 | 0.120262 | 65.597 |

| CARM - 1M HCl | 45.9749 | 0.093173 | 79.569 |

| CARM - 2M HCl | 43.1754 | 0.096185 | 89.011 |

2.3.5. Thermal Analysis

3.2. Adsorption Kinetics and Kinetic Modeling

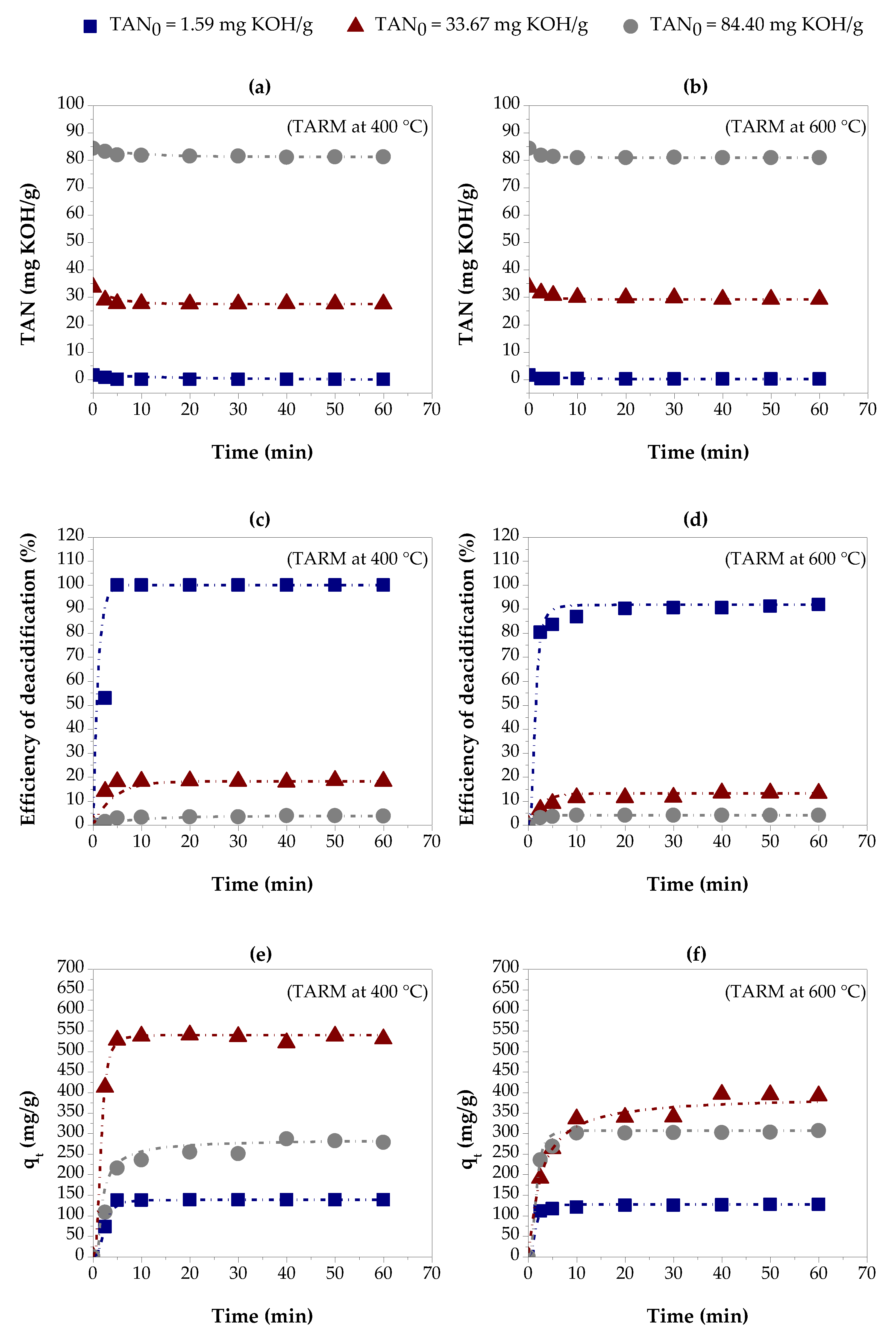

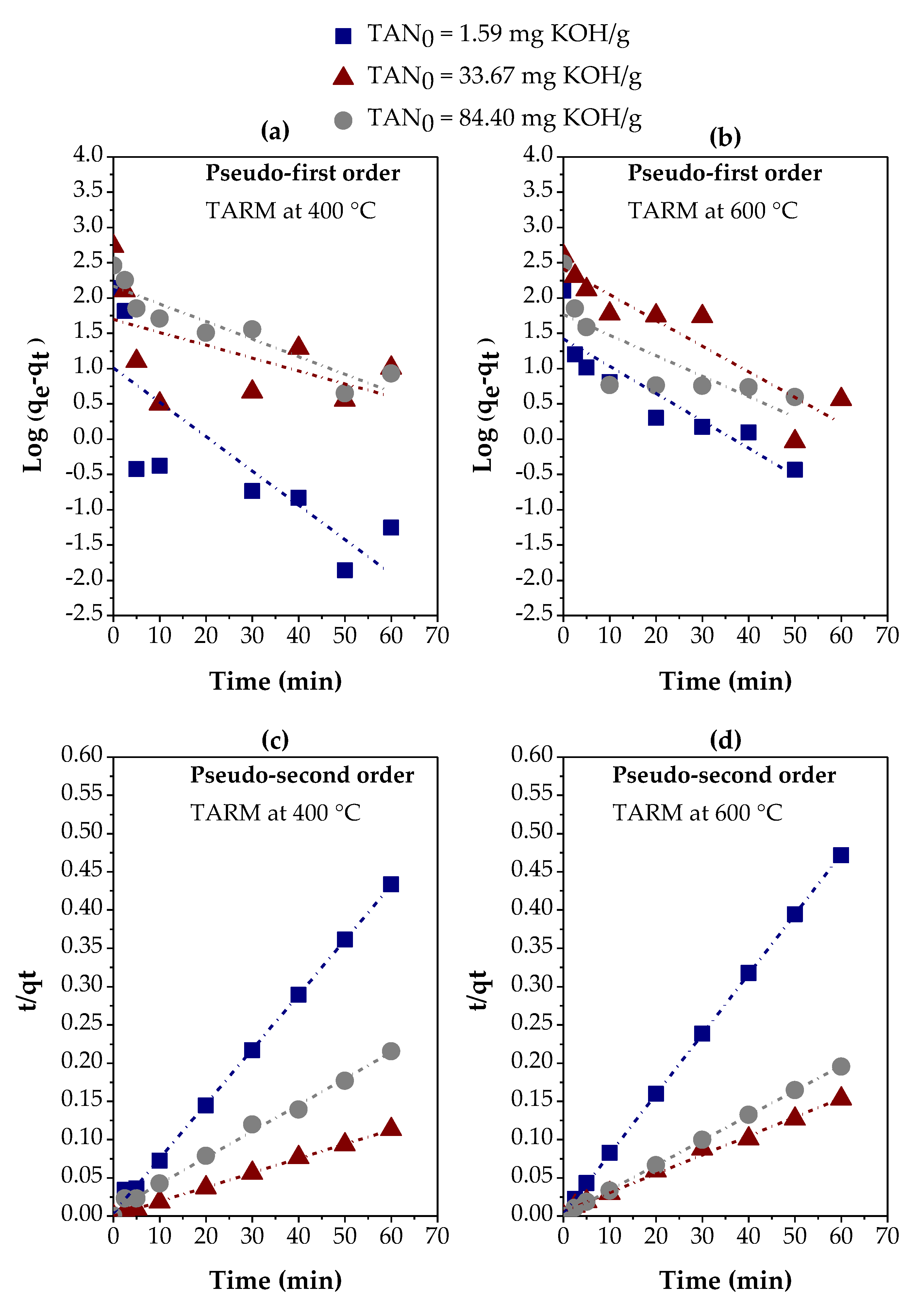

3.2.1. Thermally Activated Red Mud

| Variables evaluated | Adsorption kinetic parameters | ||||

| Adsorbent: | TARM at 400 °C | ||||

| Initial concentrations (mg KOH/g) | Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) |

K1 (min-1) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) |

R2 | ||

| 1.59 | 138.4875 | 0.1120 | 10.1962 | 0.58263 | |

| 33.67 | 539.9592 | 0.0420 | 49.6718 | 0.17397 | |

| 84.40 | 286.7990 | 0.0574 | 146.5784 | 0.83256 | |

| Initial concentrations (mg KOH/g) | Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg. min) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) | hi (mg/g. min) |

R2 | |

| 1.59 | 138.4875 | 0.0126 | 140.2525 | 246.9136 | 0.99885 |

| 33.67 | 539.9592 | 0.0157 | 531.9149 | 4434.4718 | 0.99953 |

| 84.40 | 286.7990 | 0.0015 | 290.6977 | 127.3885 | 0.99424 |

| Adsorbent: | TARM at 600 °C | ||||

| Initial concentrations (mg KOH/g) | Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) | K1 (min-1) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) | R2 | ||

| 1.59 | 127.2400 | 0.0891 | 26.2894 | 0.79762 | |

| 33.67 | 395.1952 | 0.0839 | 257.9942 | 0.83183 | |

| 84.40 | 307.2286 | 0.0669 | 58.0524 | 0.53732 | |

| Initial concentrations (mg KOH/g) | Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qe (exp.) (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg. min) |

qe (calc.) (mg/g) |

hi (mg/g. min) |

R2 | |

| 1.59 | 127.2400 | 0.0214 | 127.7139 | 349.6503 | 0.99993 |

| 33.67 | 395.1952 | 0.0010 | 404.8583 | 168.9189 | 0.99344 |

| 84.40 | 307.2286 | 0.0070 | 307.6923 | 666.6667 | 0.99977 |

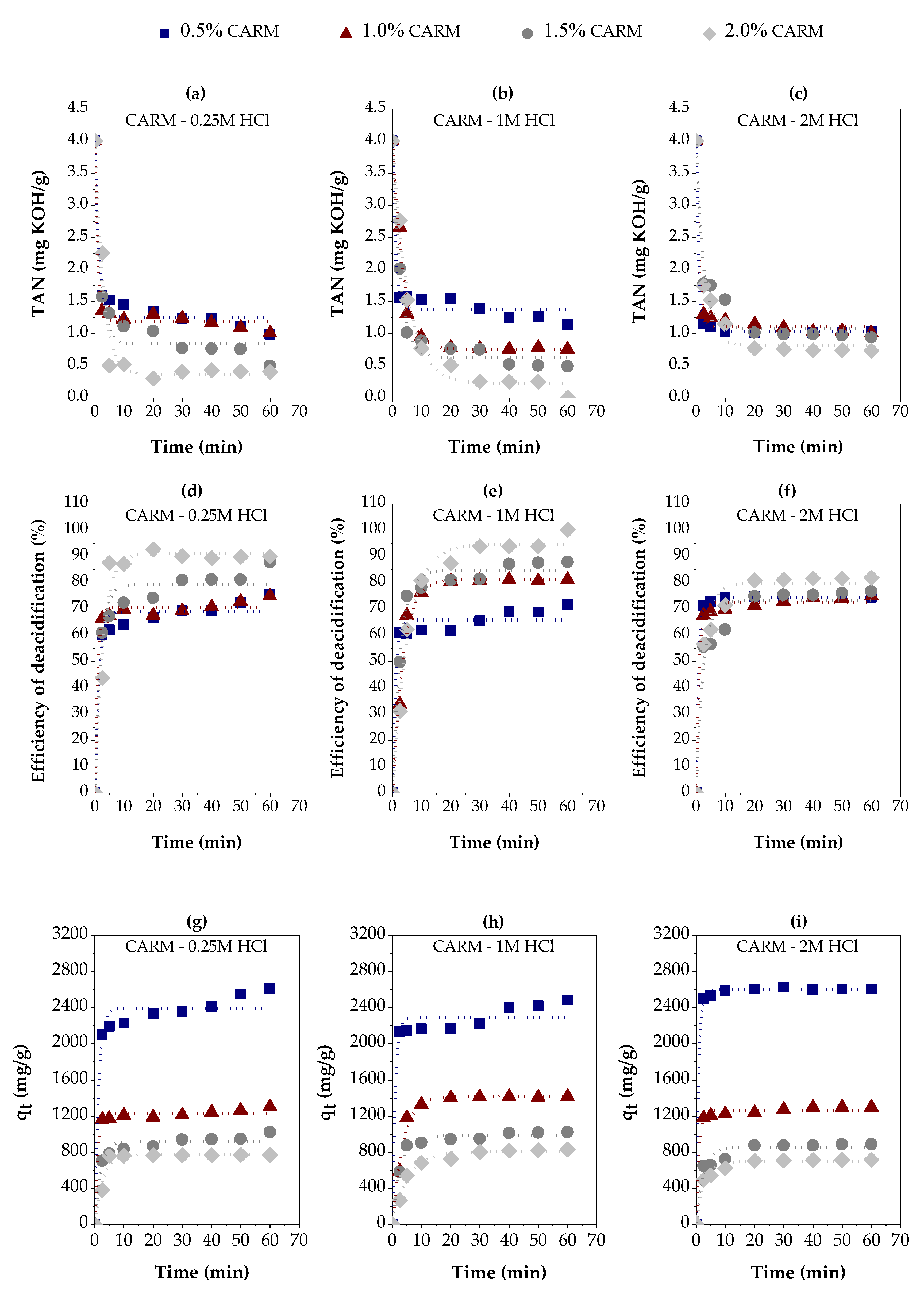

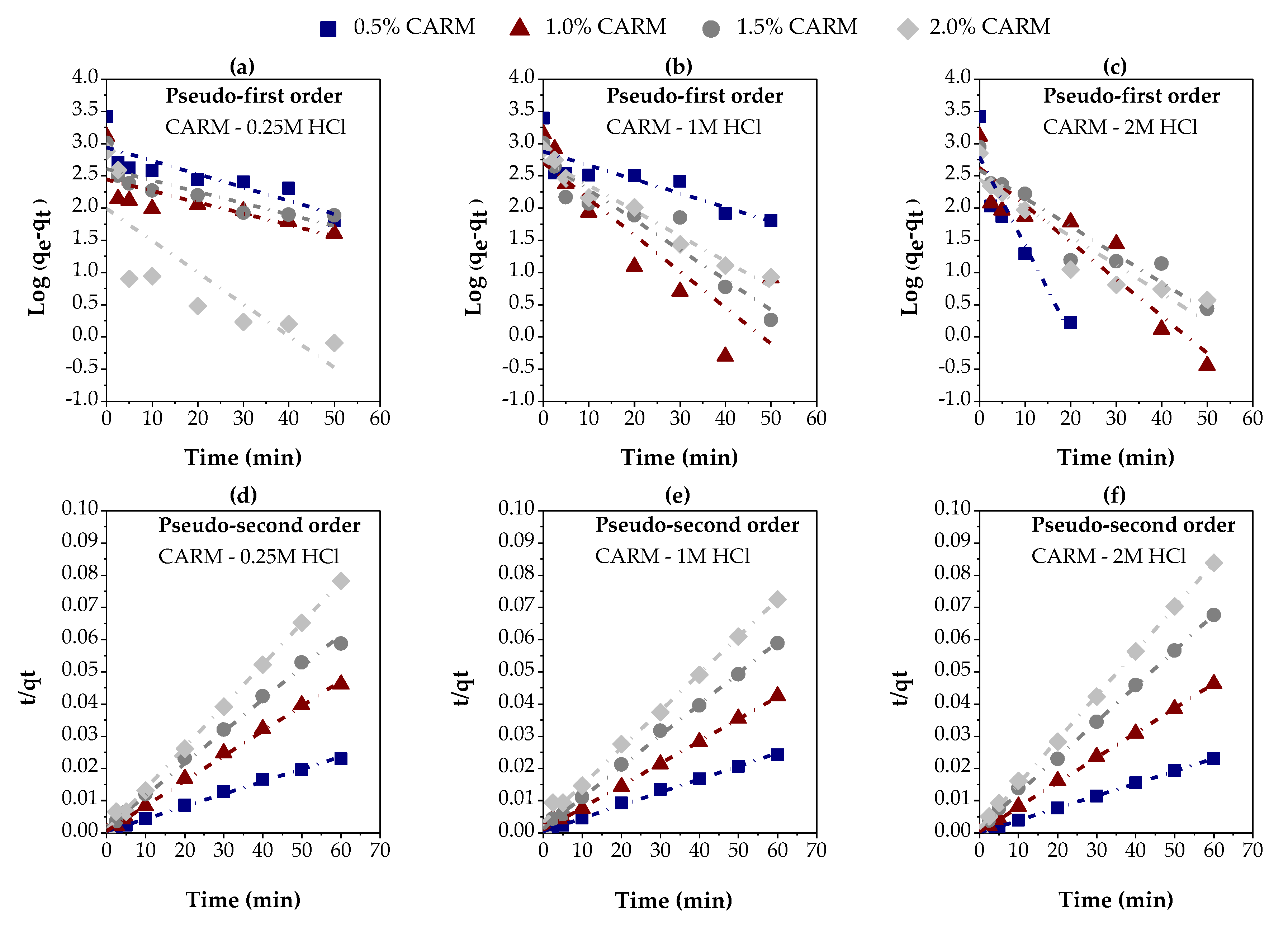

3.2.2. Chemically Activated Red Mud

| Variables evaluated | Adsorption kinetic parameters | ||||

| Adsorbent: | CARM – 0.25M | ||||

| Adsorbent percentage (%) | Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) |

K1 (min-1) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) |

R2 | ||

| 0.5 | 2611.1537 | 0.0476 | 872.7905 | 0.68024 | |

| 1.0 | 1303.0062 | 0.0406 | 276.7897 | 0.45663 | |

| 1.5 | 1021.1287 | 0.0408 | 404.5573 | 0.70295 | |

| 2.0 | 767.3193 | 0.1136 | 97.2120 | 0.61839 | |

| Adsorbent percentage (%) | Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg. min) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) | hi (mg/g. min) |

R2 | |

| 0.5 | 2611.1537 | 0.0003 | 2585.3020 | 2094.1751 | 0.99645 |

| 1.0 | 1303.0062 | 0.0011 | 1286.8589 | 1770.1872 | 0.99836 |

| 1.5 | 1021.1287 | 0.0006 | 1002.4399 | 628.9308 | 0.99524 |

| 2.0 | 767.3193 | 0.0019 | 781.2500 | 1129.7150 | 0.99855 |

| Adsorbent: | CARM – 1M | ||||

| Adsorbent percentage (%) | Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) | K1 (min-1) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) | R2 | ||

| 0.5 | 2483.3156 | 0.0500 | 757.7047 | 0.65831 | |

| 1.0 | 1415.9153 | 0.1296 | 506.9557 | 0.72991 | |

| 1.5 | 1018.8573 | 0.1074 | 564.1181 | 0.89368 | |

| 2.0 | 828.4279 | 0.0907 | 559.1135 | 0.96124 | |

| Adsorbent percentage (%) | Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qe (exp.) (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg. min) |

qe (calc.) (mg/g) |

hi (mg/g. min) |

R2 | |

| 0.5 | 2483.3156 | 0.0003 | 2471.4975 | 2069.6564 | 0.99649 |

| 1.0 | 1415.9153 | 0.0005 | 1452.2852 | 1137.7341 | 0.99758 |

| 1.5 | 1018.8573 | 0.0007 | 1035.9549 | 769.2308 | 0.99839 |

| 2.0 | 828.4279 | 0.0004 | 869.5652 | 298.5075 | 0.99502 |

| Adsorbent: | CARM – 2M | ||||

| Adsorbent percentage (%) | Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) | K1 (min-1) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) | R2 | ||

| 0.5 | 2605.8142 | 0.3173 | 629.3178 | 0.8355 | |

| 1.0 | 1298.3432 | 0.1324 | 418.7936 | 0.86549 | |

| 1.5 | 887.1661 | 0.1007 | 390.1486 | 0.88176 | |

| 2.0 | 715.5132 | 0.1018 | 277.1214 | 0.85928 | |

| Adsorbent percentage (%) | Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qe (exp.) (mg/g) | K2 (g/mg. min) |

qe (calc.) (mg/g) |

hi (mg/g. min) |

R2 | |

| 0.5 | 2605.8142 | 0.0066 | 2609.7600 | 44778.3917 | 0.99997 |

| 1.0 | 1298.3432 | 0.00017 | 1305.3075 | 2854.8916 | 0.99973 |

| 1.5 | 887.1661 | 0.0009 | 900.9009 | 751.8797 | 0.99883 |

| 2.0 | 715.5132 | 0.0013 | 729.9270 | 714.2857 | 0.99935 |

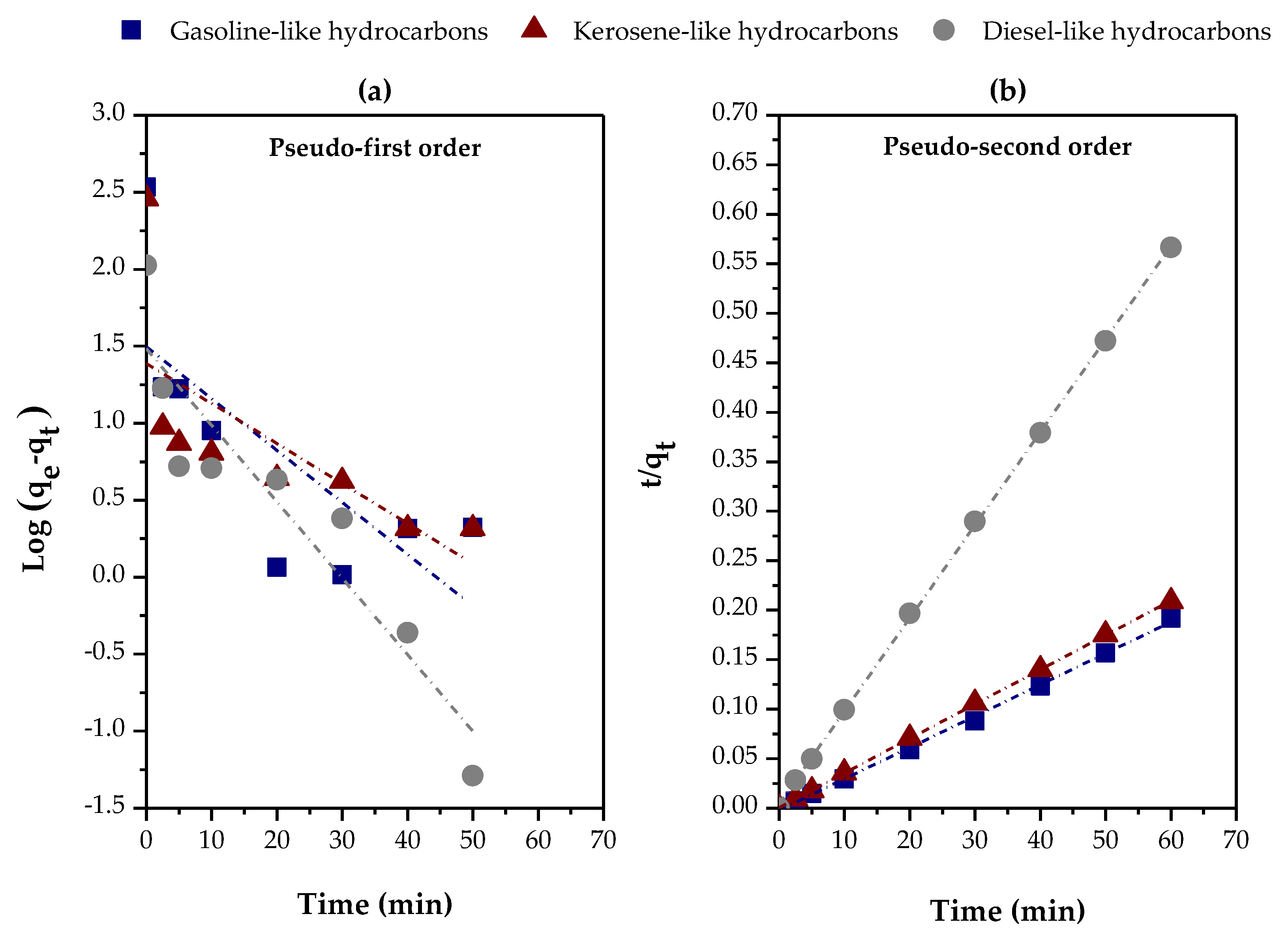

3.2.3. Effect of the Type of Feed

| Variables evaluated | Adsorption kinetic parameters | ||||

| Distilled fraction | Pseudo-first order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) |

K1 (min-1) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) |

R2 | ||

| Gasoline-like hydrocarbons | 341.4678 | 0.0776 | 31.3574 | 0.47678 | |

| Kerosene-like hydrocarbons | 287.5675 | 0.1144 | 30.4103 | 0.84354 | |

| Diesel-like hydrocarbons | 105.9485 | 0.0598 | 24.3961 | 0.41922 | |

| Distilled fraction | Pseudo-second order | ||||

| qe (exp) (mg/g) |

K2 (g/mg. min) |

qe (calc) (mg/g) |

hi (mg/g. min) |

R2 | |

| Gasoline-like hydrocarbons | 341.4678 | 0.0047 | 315.4574 | 462.9630 | 0.99837 |

| Kerosene-like hydrocarbons | 287.5675 | 0.0219 | 287.3563 | 1806.7011 | 0.99994 |

| Diesel-like hydrocarbons | 105.9485 | 0.0208 | 106.4963 | 236.4066 | 0.99979 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 2023; 1. International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Outlook 2023; Paris, 2023.

- Stedile, T.; Ender, L.; Meier, H.F.; Simionatto, E.L.; Wiggers, V.R. Comparison between Physical Properties and Chemical Composition of Bio-Oils Derived from Lignocellulose and Triglyceride Sources. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 50, 92–108. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Lei, H.; Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Ahring, B. Liquid–Liquid Extraction of Biomass Pyrolysis Bio-Oil. Energy & Fuels 2014, 28, 1207–1212. [CrossRef]

- Naji, S.Z.; Tye, C.T.; Abd, A.A. State of the Art of Vegetable Oil Transformation into Biofuels Using Catalytic Cracking Technology: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Process Biochemistry 2021, 109, 148–168.

- Lima, D.G.; Soares, V.C.D.; Ribeiro, E.B.; Carvalho, D.A.; Cardoso, É.C. V; Rassi, F.C.; Mundim, K.C.; Rubim, J.C.; Suarez, P.A.Z. Diesel-like Fuel Obtained by Pyrolysis of Vegetable Oils. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2004, 71, 987–996. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, Z.; Cai, Q.; Guo, L. Catalytic Conversion of Carboxylic Acids in Bio-Oil for Liquid Hydrocarbons Production. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 45, 138–143. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; DiMaggio, C.; Wang, H.; Mohan, S.; Kim, M.; Yang, L.; O. Salley, S.; Y. Simon Ng, K. Catalytic Conversion of Triglycerides to Liquid Biofuels Through Transesterification, Cracking, and Hydrotreatment Processes. Current Catalysis 2012, 1, 41–51.

- Bridgwater, A. V Review of Fast Pyrolysis of Biomass and Product Upgrading. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 38, 68–94. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y.H.; Loh, S.K.; Chin, B.L.F.; Yiin, C.L.; How, B.S.; Cheah, K.W.; Wong, M.K.; Loy, A.C.M.; Gwee, Y.L.; Lo, S.L.Y.; et al. Fractionation and Extraction of Bio-Oil for Production of Greener Fuel and Value-Added Chemicals: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 397, 125406. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. High-Efficiency Separation of Bio-Oil. In Biomass Now - Sustainable Growth and Use; Matovic, M.D., Ed.; InTech, 2013; pp. 401–418.

- Huber, G.W.; Iborra, S.; Corma, A. Synthesis of Transportation Fuels from Biomass: Chemistry, Catalysts, and Engineering. Chem Rev 2006, 106, 4044–4098. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, R.H.; Yin, R.Z.; Mei, Y.F. Upgrading of Bio-Oil from Biomass Fast Pyrolysis in China: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 24, 66–72. [CrossRef]

- Xiu, S.N.; Shahbazi, A. Bio-Oil Production and Upgrading Research: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4406–4414. [CrossRef]

- Shamsul, N.S.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Rahman, N.A. Conversion of Bio-Oil to Bio Gasoline via Pyrolysis and Hydrothermal: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 80, 538–549. [CrossRef]

- Baloch, H.A.; Nizamuddin, S.; Siddiqui, M.T.H.; Riaz, S.; Jatoi, A.S.; Dumbre, D.K.; Mubarak, N.M.; Srinivasan, M.P.; Griffin, G.J. Recent Advances in Production and Upgrading of Bio-Oil from Biomass: A Critical Overview. J Environ Chem Eng 2018, 6, 5101–5118. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.; Maheria, K.C.; Dalai, A.K. Bio-Oil Valorization: A Review. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews 2013, 23, 91–106. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gunawan, R.; Mourant, D.; Hasan, M.D.M.; Wu, L.; Song, Y.; Lievens, C.; Li, C.-Z. Upgrading of Bio-Oil via Acid-Catalyzed Reactions in Alcohols — A Mini Review. Fuel Processing Technology 2017, 155, 2–19. [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Li, H.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, W.; Huang, H. Bio-Oil Upgrading by Emulsification/Microemulsification: A Review. Energy 2018, 161, 214–232. [CrossRef]

- Gharib, J.; Pang, S.; Holland, D. Synthesis and Characterisation of Polyurethane Made from Pyrolysis Bio-Oil of Pine Wood. Eur Polym J 2020, 133. [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.R.; Antoniosi Filho, N.R. Production and Characterization of the Biofuels Obtained by Thermal Cracking and Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Vegetable Oils. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2009, 86, 338–347. [CrossRef]

- Mancio, A.A.; da Mota, S.A.P.; Ferreira, C.C.; Carvalho, T.U.S.; Neto, O.S.; Zamian, J.R.; Araújo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; Machado, N.T. Separation and Characterization of Biofuels in the Jet Fuel and Diesel Fuel Ranges by Fractional Distillation of Organic Liquid Products. Fuel 2018. [CrossRef]

- Da Mota, S.A.P.; Mancio, A.A.; Lhamas, D.E.L.; de Abreu, D.H.; da Silva, M.S.; dos Santos, W.G.; de Castro, D.A.R.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Ara?jo, M.E.; Borges, L.E.P.; et al. Production of Green Diesel by Thermal Catalytic Cracking of Crude Palm Oil (Elaeis Guineensis Jacq) in a Pilot Plant. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2013. [CrossRef]

- Stanford, J.P.; Hall, P.H.; Rover, M.R.; Smith, R.G.; Brown, R.C. Separation of Sugars and Phenolics from the Heavy Fraction of Bio-Oil Using Polymeric Resin Adsorbents. Sep Purif Technol 2018, 194, 170–180. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shao, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H. Upgrading of Bio-Oil: Removal of the Fermentation Inhibitor (Furfural) from the Model Compounds of Bio-Oil Using Pyrolytic Char. Energy and Fuels 2013, 27, 5975–5981. [CrossRef]

- Church, A.L.; Hu, M.Z.; Lee, S.J.; Wang, H.; Liu, J. Selective Adsorption Removal of Carbonyl Molecular Foulants from Real Fast Pyrolysis Bio-Oils. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 136, 105522. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, D.; Yang, X.; Babadi, A.A.; Wang, S.; Gong, X. Selective Adsorption of Carbonyl Compounds from Bio-Oil by Seaweed-Derived Carbon: A Theoretical Study. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2023, 173. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shen, Q.; Wu, H. Adsorption Characteristics of Bio-Oil on Biochar in Bioslurry Fuels. Energy and Fuels 2017, 31, 9619–9626. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Chen, H.; Zhu, H.; Lin, Z.; Wu, G.; Gao, W.; Zhang, H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Enhanced Adsorption of Bio-Oil on Activated Biochar in Slurry Fuels and the Adsorption Selectivity. Fuel 2023, 338, 127224. [CrossRef]

- Widjaja, C.; Djojorahardjo, Y.; Kurniawan, A.; Soetaredjo, F.E. BIOREFINERY CONCEPT ON JACKFRUIT PEEL WASTE: BIO-OIL UPGRADING. 2018, 13.

- Sedai, B.; Zhou, J.L.; Fakhri, N.; Sayari, A.; Baker, R.T. Solid Phase Extraction of Bio-Oil Model Compounds and Lignin-Derived Bio-Oil Using Amine-Functionalized Mesoporous Silicas. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2018, 6, 9716–9724. [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; Choi, W.; Genuino, D.A.; Capareda, S.C. Development of Rice Straw Activated Carbon and Its Utilizations. J Environ Chem Eng 2018, 6, 5221–5229. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Katz, L.; Qiu, S. Adsorptive Selectivity and Mechanism of Three Different Adsorbents for Nitrogenous Compounds Removal from Microalgae Bio-Oil. Ind Eng Chem Res 2019, 58, 3959–3968. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.; Costa, A.L.H.; Chiaro, S.S.X.; Delgado, B.E.P.C.; de Figueiredo, M.A.G.; Senna, L.F. Carboxylic Acid Removal from Model Petroleum Fractions by a Commercial Clay Adsorbent. Fuel Processing Technology 2013, 112, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.P.; Senna, L.F. de; Lago, D.C.B. do; Jr, P.F. da S.; Dias, E.G.; Figueiredo, M.A.G. de; Chiaro, S.S.X. Characterization of Commercial Ceramic Adsorbents and Its Application on Naphthenic Acids Removal of Petroleum Distillates. 2007, 10, 219–225.

- Wu, W.-L.; Tan, Z.-Q.; Wu, G.-J.; Yuan, L.; Zhu, W.-L.; Bao, Y.-L.; Pan, L.-Y.; Yang, Y.-J.; Zheng, J.-X. Deacidification of Crude Low-Calorie Cocoa Butter with Liquid–Liquid Extraction and Strong-Base Anion Exchange Resin. Sep Purif Technol 2013, 102, 163–172. [CrossRef]

- Deboni, T.M.; Batista, E.A.C.; Meirelles, A.J.A. Equilibrium, Kinetics, and Thermodynamics of Soybean Oil Deacidification Using a Strong Anion Exchange Resin. Ind Eng Chem Res 2015, 54, 11167–11179. [CrossRef]

- Manuale, D.L.; Torres, G.C.; Badano, J.M.; Vera, C.R.; Yori, J.C. Adjustment of the Biodiesel Free Fatty Acids Content by Means of Adsorption. Energy & Fuels 2013, 27, 6763–6772. [CrossRef]

- Lagergren, S. About the Theory of So-Called Adsorption of Soluble Substances. 1898.

- Ho, Y.-S.; McKay, G. Kinetic Models for the Sorption of Dye from Aqueous Solution by Wood. Process safety and environmental protection 1998, 76, 183–191.

- Antunes, M.L.P.; Conceição, F.T.; Navarro, G.R.B.; Fernandes, A.M.; Durrant, S.F. Use of Red Mud Activated at Different Temperatures as a Low Cost Adsorbent of Reactive Dye. Engenharia Sanitaria e Ambiental 2021, 26, 805–811. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Liang, W.; Ma, L.; Ma, C. Properties and Characterization of Red Mud Modified by Hydrochloric, Sulfuric, and Nitric Acid for the Catalytic Oxidation of Toluene. J Environ Chem Eng 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, P.; Silvetti, M.; Enzo, S.; Melis, P. Study of Sorption Processes and FT-IR Analysis of Arsenate Sorbed onto Red Muds (a Bauxite Ore Processing Waste). J Hazard Mater 2010, 175, 172–178. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, D.-Y. Physical and Chemical Properties of Sintering Red Mud and Bayer Red Mud and the Implications for Beneficial Utilization. Materials 2012, 5, 1800–1810. [CrossRef]

- Castaldi, P.; Silvetti, M.; Santona, L.; Enzo, S.; Melis, P. XRD, FTIR, and Thermal Analysis of Bauxite Ore-Processing Waste (Red Mud) Exchanged with Heavy Metals. Clays Clay Miner 2008, 56, 461–469, . [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.C.M.; do Nascimento, R.A.; Amador, I.C.B.; Santos, T.C. de S.; Martelli, M.C.; de Faria, L.J.G.; Ribeiro, N.F. da P. Chemically Activated Red Mud: Assessing Structural Modifications and Optimizing Adsorption Properties for Hexavalent Chromium. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2021, 628. [CrossRef]

- Kurtoğlu, S.F.; Soyer-Uzun, S.; Uzun, A. Tuning Structural Characteristics of Red Mud by Simple Treatments. Ceram Int 2016, 42, 17581–17593. [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure and Applied Chemistry 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [CrossRef]

- Brunauer, E.; Journal, T. ) Reyerson and Cameron; UTC, 1937; Vol. 69.

- Suzuki, Motoyuki. Adsorption Engineering; Elsevier, 1989; ISBN 0444988025.

- Sushil, S.; Batra, V.S. Catalytic Applications of Red Mud, an Aluminium Industry Waste: A Review. Appl Catal B 2008, 81, 64–77.

- Liu, Q.; Xin, R.; Li, C.; Xu, C.; Yang, J. Application of Red Mud as a Basic Catalyst for Biodiesel Production. J Environ Sci (China) 2013, 25, 823–829. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.C.S. Modificação do resíduo de bauxita gerado no processo Bayer por tratamento térmico. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade de São Paulo, 2012.

- Al-Asheh, S.; Banat, F.; Abu-Aitah, L. Adsorption of Phenol Using Different Types of Activated Bentonites. Sep Purif Technol 2003, 33, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Jean Baptiste, B.M.; Daniele, B.K.; Marie Charlène, E.; Larrissa Canuala, T.T.; Antoine, E.; Richard, K. Adsorption Mechanisms of Pigments and Free Fatty Acids in the Discoloration of Shea Butter and Palm Oil by an Acid-Activated Cameroonian Smectite. Sci Afr 2020, 9, e00498. [CrossRef]

- López-Velandia, C.; Moreno-Barbosa, J.; Sierra-Ramirez, R.; Giraldo, L.; Moreno-Piraján, J. Adsorption of Volatile Carboxylic Acids on Activated Carbon Synthesized from Watermelon Shells. Adsorption Science and Technology 2014, 32, 227–242. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, B.; Liu, Q.; Wu, C.; Li, Z. Preparation of Porous Biochar from Heavy Bio-Oil for Adsorption of Methylene Blue in Wastewater. Fuel Processing Technology 2022, 238, 107485. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Wongrod, S.; Vinitnantharat, S. Adsorption Kinetics of Cadmium and Lead by Biochars in Single- and Bisolute Brackish Water Systems. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 45262–45276. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dong, X.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Duan, W.; Park, J.; Gao, L.; Lu, Y. Comparative Study on the Adsorption Characteristics of Heavy Metal Ions by Activated Carbon and Selected Natural Adsorbents. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Machado, N.T.; Mota, A. de A.M. da; Santanna, J. da S.; Gama, V. de J.P. da; Zamian, J.R.; Borges, L.E.P.; Mota, S.A.P. da Catalytic Cracking of Palm Oil: Effect of Catalyst Reuse and Reaction Time of the Quality of Biofuels-like Fractions. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16. [CrossRef]

- Poling, B.E.; Prausnitz, J.M.; O’connell, J.P. The Properties of Gases and Liquids; Mcgraw-hill New York, 2001; Vol. 5.

- Shou, J.; Qiu, M. Adsorption Kinetics of Phenol in Aqueous Solution onto Activated Carbon from Wheat Straw Lignin. Desalination Water Treat 2016, 57, 3119–3124. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).