Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Bases

2.1. Fundamental Notions

2.2. Agency and Autonomy

3. Causality as Information

3.1. Intrinsic Information

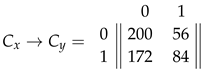

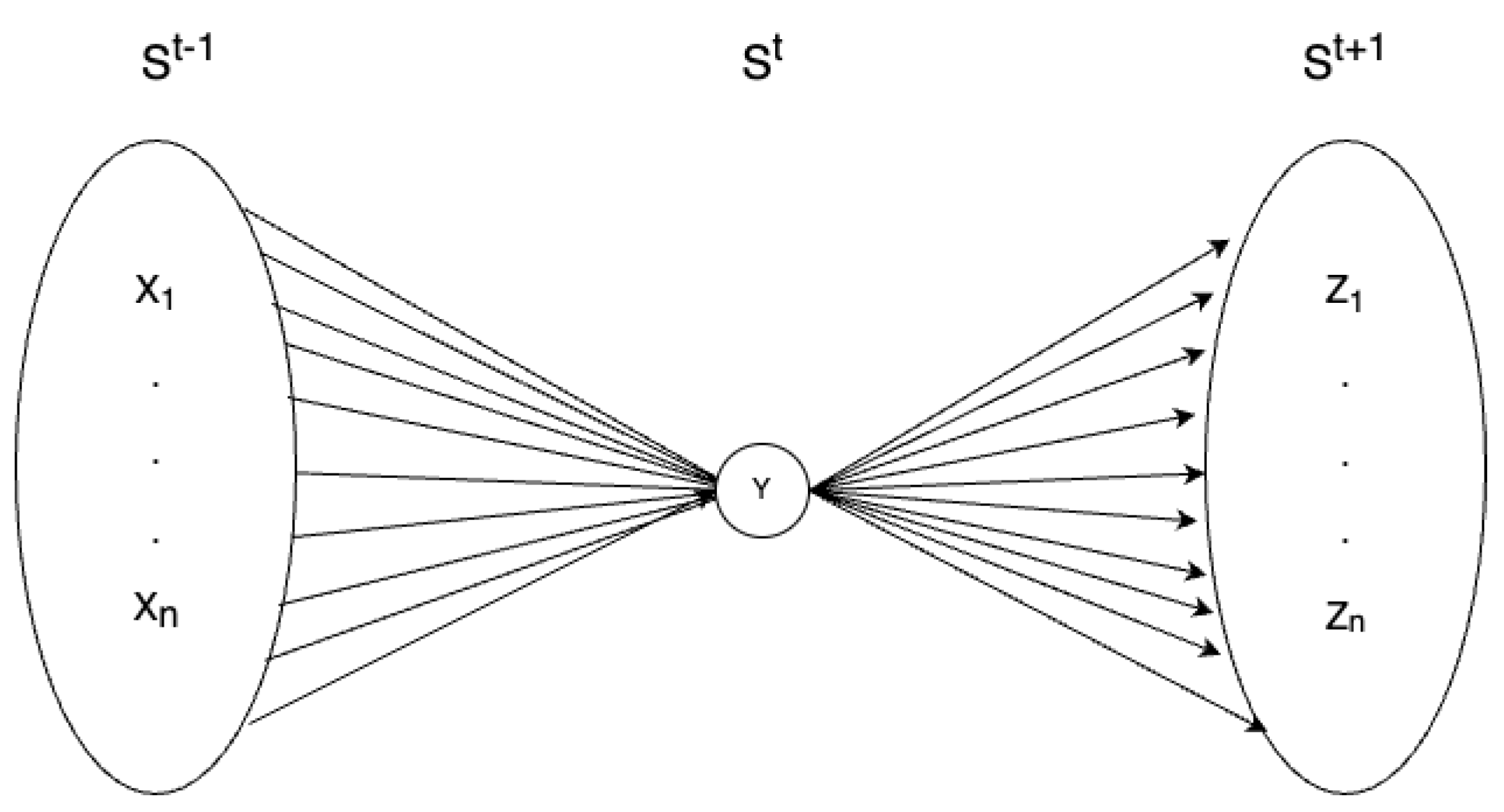

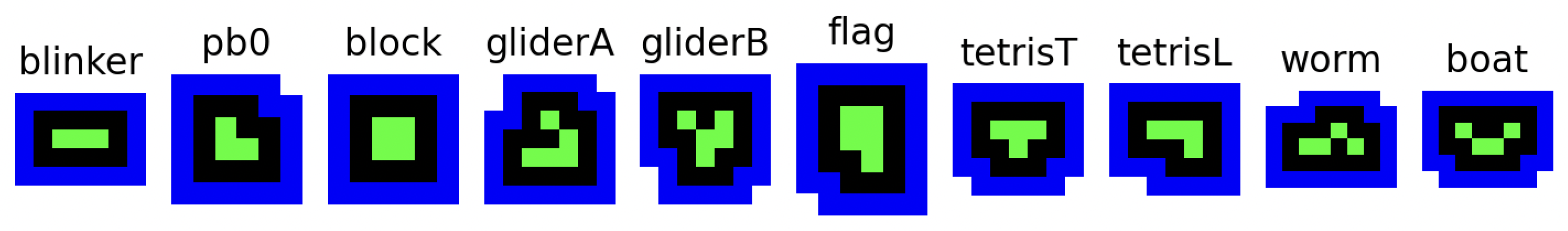

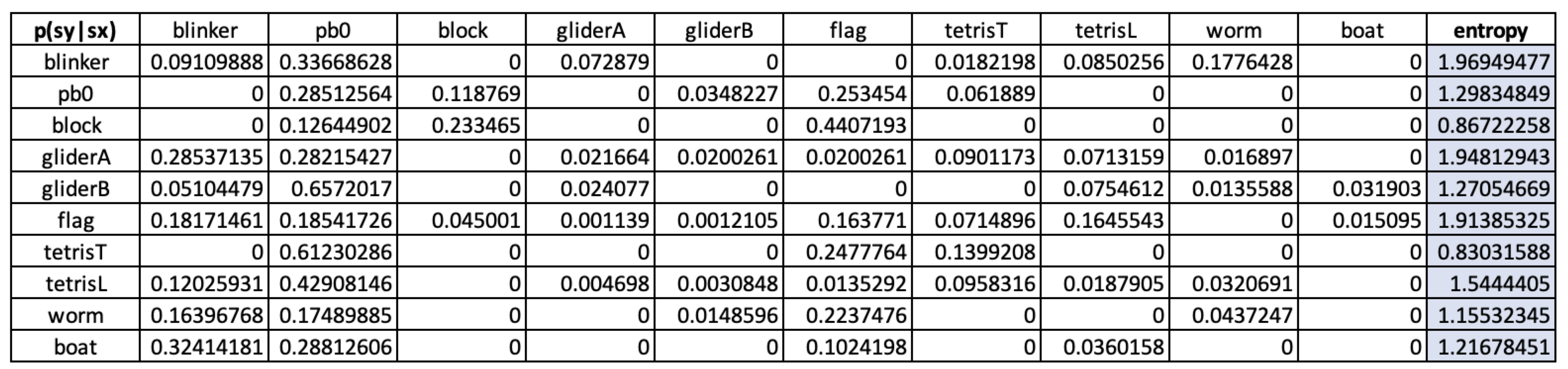

3.2. Cause-Effect Information in the Game of Life

4. Under-Determination as Latent Agency

4.1. Some Considerations

4.2. Coming back to GoL

4.3. A More Complex Case from GoL

5. Discussion and Concluding Remarks

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baltieri, M.; Iizuka, H.; Witkowsi, O.; Sinapayen, L.; Suzuki, K. Hybrid Life: Integrating biological, artificial, and cognitive systems. WIREs Cognitive Science 2023, e1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tallis, R. Freedom: An impossible reality; Agenda Publishing Limited, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Libet, B.; Gleason, C.A.; Right, E.W.; Pearl, D.K. TIME OF CONSCIOUS INTENTION TO ACT IN RELATION TO ONSET OF CEREBRAL ACTIVITY (READINESS-POTENTIAL): THE UNCONSCIOUS INITIATION OF A FREELY VOLUNTARY ACT. Brain 1983, 106, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. Mind in a physical world: an essay on the mind-problem and mental causation; MIT Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Churchland, P.; Suhler, C. Agency and Control: The Subcortical Role in Good Decisions. In Moral Psychology, Volume 4: Free Will and Moral Responsibility, Walter Sinnott-Armstrong; The MIT Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dennet, D. Elbow Room: The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting; The MIT Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, T.T. Neurocognitive free will. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2019, 286, 20190510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavazza, A. Why Cognitive Sciences Do Not Prove That Free Will Is an Epiphenomenon. Frontiers in Psychology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, K.; Villalobos, M. The apparent (Ur-)Intentionality of Living Beings and the Game of Content. Philosophia 2015, 43, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, H.; Mitchell, K. Naturalasing agent causation. Entropy 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandiaran, X.; Di Paolo, E.; Rohde, M. Defining Agency: Individuality, Normativity, Asymmetry, and Spatio-temporality in Action. Adaptive Behavior 2009, 17, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G.; Sealander, A.; Marzen, S.; Levin, M. From reinforcement learning to agency: Frameworks for understanding basal cognition. BioSystems 2024, 235, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Etxeberria, A. Agency in Natural and Artificial Systems. Artificial Life 2005, 11, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biehl, M.; Virgo, N. Bayesian ghosts in a machine? ALIFE 2023: Ghost in the Machine: Proceedings of the 2023 Artificial Life Conference, 2023, p. 96. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Agency in Physics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.05300v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, A.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Liu, K.; 2, M.M.; Cui, P. Emergence and Causality in Complex Systems: A Survey of Causal Emergence and Related Quantitative Studies. Entropy 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biehl, M.; Virgo, N. Interpreting systems as solving POMDPs: a step towards a formal understanding of agency. In Buckley, C.L., et al. Active Inference. IWAI 2022, Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1721.; Springer, Cham, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Froese, T. Irruption Theory: A Novel Conceptualization of the Enactive Account of Motivated Activity. Entropy 2023, 25, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H.; Varela, F. Autopoiesis: the organization of the living. [De maquinas y seres vivos. Autopoiesis: la organizacion de lo vivo]. 7th edition from 1994; Editorial Universitaria, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H. Tha organization of the living: A theory of the living organization. International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 1975, 7, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F. Principles of Biological Autonomy; North Holland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F. Patterns of life: Intertwining identity and cognition. Brain cognition 1997, 34, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience; The MIT Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F. Preface from Francisco J. Varela Garcia to the second edition. In De Mâquinas y seres vivos. Autopoiesis: la organizaciôn de lo vivo; chapter Preface; Editorial Universitaria, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, E. Autopoiesis, adaptivity, teleology, agency. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 2005, 4, 429–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandiaran, X. Autonomy and Enactivism: Towards a Theory of Sensorimotor Autonomous Agency. Topoi 2017, 36, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, R. An integrated Perspective on the Constitutive and Interactive Dimensions of Autonomy. Proceedings of the ALIFE 2020: The 2020 Conference on Artificial Life, 2020, pp. 202–209. [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Silverman, D.; Villalobos, M. Introduction: The Varieties of Enactivism. Topoi 2017, 36, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. Embodied and Enactive approaches to Cognition; Cambridge University Press, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmann, T.; Di Paolo, E. The sense of agency - a phenomenological consequence of enacting sensorimotor schemes. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 2017, 16, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennett, D.C. Intentional Systems. The Journal of Philosophy 1971, 68, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennet, D.C. The intentional stance in theory and practice. In Machiavellian intelligence: Social expertise and the evolution of intellect in monkeys, apes, and humans; Byrne, R.W., Whiten, A., Eds.; Clarendon Press/Oxford University Press, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl, M.; Kanai, R. Dynamics of a Bayesian Hyperparameter in a Markov Chain. In Verbelen, T., Lanillos, P., Buckley, C.L., De Boom, C. (eds) Active Inference. IWAI 2020. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1326; Springer, Cham, 2020.

- Virgo, N.; Biehl, M.; McGregor, S. Interpreting Dynamical Systems as Bayesian Reasoners. In Kamp, M., et al. Machine Learning and Principles and Practice of Knowledge Discovery in Databases. ECML PKDD 2021. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 1524; Springer, Cham, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hutto, D.; Myin, E. Radicalizing Enactivism. Basic minds without content; MIT Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Villalobos, M.; Silverman, D. Extended functionalism, radical enactivism and the autopoietic theory of cognition: prospects for a full revolution in cognitive science. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 2018, 17, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F. Two Principles for Self-Organization. In Self-Organization and Management of Social Systems; Ulrich, H., Probst, G.J.B., Eds.; Springer Series on Synergetics, vol 26; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Virgo, N.; Harvey, I. Adaptive growth processes: a model inspired by Pask’s ear. Artificial Life XI, 2008.

- Sayama, H. Construction theory, self-replication, and the halting problem. Complexity 2008, 13, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanczyz, M.; Ikegami, T. Chemical basis for minimal cognition. Artificial Life 2010, 16, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, R. Bittorio revisited: Structural coupling in the Game of Life. Adaptive Behavior 2020, 28, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M.; Ward, D. Living Systems: Autonomy, Autopoiesis and Enaction. Philosophy & Technology 2015, 28, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, D.; Myin, E. Evolving Enactivism. Basic Minds Meet Content; MIT Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Di Paolo, E.; Burhmann, T.; Barandarian, X. Sensorimotor Life: An enactive proposal; Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Friston, K. Am I Self-Conscious? (Or Does Self-Organization Entail Self-Consciousness?). Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowes, S. Naturally Minded: Mental Causation, Virtual Machines, and Maps; Springer Verlag, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, T.; Di Paolo, E. The enactive approach. Theoretical sketches from cell to society. Pragmatics and Cognition 2011, 19, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albantakis, L.; Barbosa, L.; Findlay, G.; Grasso, M.; Haun, A.M.; Marshall, W.; Mayner, W.G.P.; Zaeemzadeh, A.; Boly, M.; Juel, B.E.; Sasai, S.; Fujii, K.; Isaac David, J.H.; Lang, J.P.; Tononi, G. Integrated information theory (IIT) 4.0: Formulating the properties of phenomenal existence in physical terms. PLoS Computational Biology 2023, 19, e1011465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D. Strong and Weak Emergence. In The Re-Emergence of Emergence: The Emergentist Hypothesis from Science to Religion; Oxford University Press, 2011; pp. 244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, D. Autonomy, Consciousness, and Freedom. The Amherst Lecture in Philosophy 2019, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Froese, T.; Taguchi, S. The Problem of Meaning in AI and Robotics: Still with Us after All These Years. Philosophies 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea, I. On motivating irruptions: the need for a multilevel approach at the interface between life and mind. Adaptive Behavior 2023, 32, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, T. To Understand the Origin of Life We Must First Understand the Role of Normativity. Biosemiotics 2021, 14, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H. Preface from Humberto Maturana Romesîn to the second edition. In De Mâquinas y seres vivos. Autopoiesis: la organizaciôn de lo vivo; chapter Preface; Editorial Universitaria, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H. Autopoiesis, Structural Coupling and Cognition: A history of these and othe notions in the biology of cognition. Cybernetics and Human Knowing 2002, 9, 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Beer, R. Autopoiesis and Cognition in the Game of Life. Artificial Life 2004, 10, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, R. The Cognitive Domain of Glider in the Game of Life. Artificial Life 2014, 20, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell, P. Understanding Bateson and Maturana: Toward a Biological Foundation for The Social Sciences. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 1985, 11, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W. An introduction to cybernetics; J. Wiley, New York, 1956.

- Maturana, H. Everything said is said by an observer. In Gaia: A way of knowing; Thompson, W.I., Ed.; Lindisfarne Press: New York, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Beeson, I. Implications of the Theory of Autopoiesis for the discipline and practice of Information Systems. In Russo, N.L., Fitzgerald, B. De Gross, J.I. (eds) Realining Research and Practice in Information Systems Development. IFIP - The international Federation for Information Processing, vol. 66; Springer, Boston, MA, 2017.

- Seth, A. Being you: A new science of consciousness; Faber and Faber Ltd, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an echology of mind: Collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution and epistemologyC; Jason Aronson, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Tononi, G. An Information Integration Theory of Consciousness. BMC Neuroscience 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduzzi, D.; Tononi, G. Integrated Information in Discrete Dynamical Systems: Motivation and Theoretical Framework. PLoS Comput Biol. 2008, 4, e1000091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oizumi, M.; Albantakis, L.; Tononi, G. From the Phenomenology to the Mechanisms of Consciousness: Integrated Information Theory 3.0. PLOS Computational Biology 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tononi, G.; Koch, C. Consciousness: here, there and everywhere? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2015, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautz, A. What is the Integrated Information Theory of Consciousness. A Catalogue of Questions. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2019, 26, 188–215. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, B.; Zhang, J.; Lyu, A.; Wu, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Liu, K.; Mou, M.; Cui, P. Emergence and Causality in Complex Systems: A Survey of Causal Emergence and Related Quantitative Studies. Entropy 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, O.; López, C. What does ’Information’ Mean in Integrated Information Theory. Entropy 2018, 20, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediano, P.; Seth, A.; Barret, A. Measuring Integrated Information: Comparison of Candidate Measures in Theory and Simulation. Entropy 2018, 21, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D. The Combination Problem for Panpsychism. In Brüntrup Godehard & Jaskolla Ludwig (eds.), Panpsychism; Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Tsuchiya, N.; Taguchi, S.; Saigo, H. Using category theory to asses the relationship between consciousness and integrated information theory. Neuroscience Research 2016, 107, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerig, A.; Schurger, A.; Hess, K.; Herzog, M. The unfolding argument: Why IIT and other causal structure theories cannot explain consciousness. Consciousness and Cognition 2019, 72, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merker, B.; Williford, K.; Rudrauf, D. The Integrated Information Theory of consciousness: A case of mistaken identity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2021, May, 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, I.; Mudumba, R.; Srinivasan, N. In search of lost time: Integrated information theory needs constraints from temporal phenomenology. Philosophy and the Mind Sciences 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northoff, G.; Zilio, F. From Shorter to Longer Timescales: Converging Integrated Information Theory (IIT) with the Temporo-Spatial Theory of Consciousness (TTC). Entropy 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.; Husbands, P.; Ghosh, A.; White, B. Frame by frame? A contrasting research framework for time experience. ALIFE 2023: Ghost in the Machine: Proceedings of the 2023 Artificial Life Conference. MIT Press, 2023, p. 75. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M.; Di Paolo, E. Integrated information in the thermodynamic limit. Neural Networks 2019, 114, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediano, P.; Rosas, F.; Bor, D.; Seth, A.; Barret, A. The strength of weak integrated information theory. Trends on Cognitive Sciences 2022, 26, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosas, F.; Mediano, P.; Jensen, H.; Seth, A.; Barret, A.; Carthart-Harris, R. Reconciling emergences: An information-theoretic approach to identify causal emergence in multivariate data. PLOS. Computational Biology 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varley, T.F. Flickering Emergences: The Question of Locality in Information-Theoretic Approaches to Emergence. Entropy 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubner, Y.; Tomasi, C.; Guibas, J. A Metric for Distributions with Applications to Image Databases. Proceedings of the 1998 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Bombay, India, 1998.

- Weng, L. What is Wasserstein distance? https:/lilianweng.github.io/posts/2017-08-20-gan/what-is-wasserstein-distance.

- Weisstein, E. Moore Neighborhood. From MathWorld–A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/MooreNeighborhood.html.

- Gardner, M. Mathematical Games: The Fantastic Combinations of John Conway’s New Solitaire Game ’Life’. Scientific American 1970, 223, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlekamp, E.; Conway, J.; Guy, R. Winning ways for your mathematical plays, vol. 2; Academic Press: New York, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A.; Varela, F. Life after Kant: Natural purposes and the autopoietic foundations of biological individuality. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 2002, 1, 97–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, M. Autopoiesis, free energy, and the life-mind continuity thesis. Synthese 2018, 195, 2519–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, R. Characterizing Autopoiesis in the Game of Life. Artificial Life 2015, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, R. On the Origins of Gliders. Proceedings of the ALIFE 2018: The 2018 Conference on Artificial Life. ALIFE2018: The 2018 Conference on Artificial Life. Tokyo, Japan., 2018, pp. 67–74. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.; Husbands, P. A saucerful of secrets: Open-ended organizational closure in the Game of Life. ALIFE 2024: Proceedings of the 2024 Artificial Life Conference. MIT Press, 2024, p. 4. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M.; Palacios, S. Autopoietic theory, enactivism, and their incommensurable marks of the cognitive. Synthese 2021, 198, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, P. Autopoiesis and Knowing: Reflections on Maturana’s Biogenic Explanation of Cognition. Cybernetics And Human Knowing 2004, 11, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

| Total | |||

| 28 | 0 | 28 | |

| 0 | 56 | 56 | |

| 172 | 0 | 172 | |

| 0 | 28 | 28 | |

| 0 | 56 | 56 | |

| 172 | 0 | 172 | |

| Total | 372 | 140 | 512 |

| Total | |||

| 2 | 28 | 28 | 56 |

| 3 | 0 | 112 | 112 |

| q | 344 | 0 | 344 |

| Total | 372 | 140 | 512 |

| blinker | 0.633 | 1.322 | tetrisL=0.381 | =0.030 |

| pb0 | 1.583 | block=0.389 | =0.089 | |

| block | 0.570 | flag=0.687 | block=0.133 | |

| gliderA | 0.235 | 1.251 | tetrisL=0.151 | =0.011 |

| gliderB | 0.767 | 1.340 | tetrisL=0.266 | =0.065 |

| flag | 0.644 | 0.949 | =0.352 | =0 |

| tetrisT | 2.060 | flag=0.591 | tetrisT=0.525 | |

| tetrisL | 1.352 | 1.853 | flag=1.139 | =0.120 |

| worm | 0.986 | 0.929 | worm=0.524 | =0.095 |

| boat | 1.445 | 1.314 | flag=0.740 | tetrisL=0.373 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).