1. Introduction

The rapid evolution of the Internet of Things (IoT) has profoundly reshaped our understanding of technology and its integration into society. No longer a mere collection of isolated, disconnected devices, IoT has evolved into a sophisticated network of interconnected systems augmented by Artificial Intelligence (AI), forming what is now termed the Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) [

1]. This convergence allows devices to collect, process, and share data and to perform real-time decision-making and autonomous actions. The AIoT paradigm holds immense potential to revolutionize industries, enhance human capabilities, bridge the digital divide in remote areas, and address pressing global challenges through innovative solutions. However, this increasing complexity also introduces scalability, adaptability, resilience, and sustainability challenges demanding robust strategies to ensure successful and ethical deployment.

Intelligence derives from Latin inter-lĕgo, literally “collecting in between” and therefore features a choice and suggests an action; it is considered the ensemble of the psychic and mental faculties that allow humans to think, understand and explain facts/actions, elaborate symbolic models of reality, it includes awareness and self-awareness [

2]. In cybernetics, AI represents an inadequate representation of human intellectual activity (regarding learning, recognition, and choice). Traditional definitions of intelligence focus on an agent's capacity to acquire and apply knowledge and skills, facilitating problem-solving, decision-making, and adaptation. Building on this foundation, collective intelligence has been conceptualized as an aggregation of individual knowledge within a collective, enabling achievements beyond the capabilities of any single agent [

3]. However, these conventional definitions prove inadequate in complex environments characterized by high uncertainty, interdependent elements, and unpredictable dynamics. Their emphasis on stable knowledge and individual problem-solving fails to address the challenges of rapidly evolving conditions.

To better address the needs of complex environments, we redefine intelligence as "the capacity to efficaciously enhance future possibilities under uncertainty by identifying patterns and learning from them, expanding the diversity of potential futures, and increasing outcome viability through adaptive information processing." This view of intelligence is not a means to achieve certainty or control but is rather a dynamic capability that preserves flexibility and adaptability. Success in this framework stems from maintaining open options and continuously evolving in response to changing conditions, rather than relying on static knowledge repositories. This approach is close to the agile framework adopted in project management and offers a proven, higher efficacy when uncertainty is found [

4].

This reconceptualization necessarily transforms our understanding of collective intelligence. While [

5] describes this as the shared intelligence emerging from multi-agent collaboration or competition, we propose a more comprehensive definition that explicitly acknowledges complexity. Hence, "collective intelligence in complex environments emerges as a network of processes arising from interactions among autonomous agents. These processes enable intelligent functionality through the recognition and acquisition of relevant information, dynamic filtering and organization of data, development of flexible, actionable strategies under uncertainty, and continuous adaptation to emerging conditions." This understanding of collective intelligence aligns with what Yolles and Fink [

6] term "process intelligence" - "a network of processes that manifest information efficaciously through semantic channels thereby allowing meaning to arise from the manifested content in a receiving trait system." A trait system in this context refers to a structured set of characteristics that define the system's capabilities and behaviors. This structured set arises under certain conditions from the interactions between autonomous, interacting agents in a population from which emerges agency - an avatar of a complex adaptive system. This emergent agency possesses an information structure that can be represented through Simon's [

7] concept of system hierarchy. Each level in this hierarchy can be characterized by distinct formative traits that orient their functionality, creating a nested arrangement of trait systems. This hierarchical organization means that process intelligence operates not just at the collective level, but across multiple interconnected layers, each with its own trait-based capabilities for receiving and processing information. Recent studies highlight how this multi-level organization can develop autonomously, for example the universe of concepts represented by large language models (LLMs) whose structure has revealed three levels: an “atomic” scale of limited sets of words connected in small clusters; an intermediate “cerebral” scale of words ensembles where knowledge fields are localized in space; a “galactic” scale that reveals spatial anisotropy as well [

8].

To effectively model this form of collective intelligence, the metacybernetic paradigm [

9] is adopted, an advanced framework extending cybernetic theory to systems of increasing complexity, where the focus is on how cybernetic systems are conceptualized, reflecting on cybernetics itself. The framework uses Mindset Agency Theory (MAT) (and its elaboration through metacybernetics [

6,

9,

10] to represent emergent collective intelligence in living systems. These arise as “process intelligences” which act as organizing forces that recursively form as a manifestation of the interactions of diverse agents. MAT builds on Varela’s [

11,

12] concept of autopoiesis as expanded by Eric Schwarz [

13] while integrating Piaget’s [

14] learning model. Process intelligences function within a system hierarchy [

7] connecting a hierarchy of control systems each operationalized for information flows by specialized agents. The integration of these operations gives agency self-organization and development by continuous adaptive learning through internal and external imperatives delivered by process intelligences. Technically, agencies are living systems, but not in the Aristotelian sense still accepted by many biologists today [

15]. Rather, in complex adaptive systems a definition of generic living systems is more appropriate.

The first level of operative intelligence in metacybernetics aligns with Varela’s [

11,

12] autopoiesis—a self-sustaining process in which systems maintain their structure and operational boundaries. Generic living systems are also symbolic in that they can depict living in terms of abstract information and having functionality associated with cognitive, affective and semiotic processes. The promise of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) exemplifies these symbolic systems, performing life-like activities by processing information and interpreting meaning autonomously [

16].

Metacybernetics offers a compelling framework for conceptualizing collective intelligence cybernetically, emphasizing reflexivity, self-regulation, and adaptability as substrate principles [

9]. These ideas are central to the design of intelligent systems within the Internet of Things (IoT) and the Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) environments, where the ability of systems to autonomously adapt to dynamic conditions is paramount. Reflexivity, as applied to IoT, enables systems to monitor and adjust their states in response to environmental inputs, a capability exemplified by digital twins [

17]. Digital twins, as virtual representations of physical assets, provide real-time updates and simulations that allow systems to dynamically optimize their operations, mimicking reflexive processes found in living systems. When paired with AI, these systems transition from reactive to predictive and prescriptive functionalities, advancing their capacity to adapt [

18].

Self-regulation within Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) systems underscores the parallels between synthetic and living systems. By maintaining stability and balance in complex and dynamic environments, these systems exhibit homeostatic behaviors. For instance, smart grids autonomously balance electricity supply and demand, redistributing energy as needed to ensure network stability, thus reflecting biological principles of self-regulation [

19]. The integration of decentralized architecture enhances this capability by introducing redundancy, making the systems more resilient to disruptions [

20]. Similarly, adaptability in AIoT systems illustrates their capacity to evolve in response to changing conditions. Precision agriculture demonstrates this principle through the deployment of IoT sensors that collect data on environmental factors, which AI platforms analyze to provide actionable insights. Over time, these systems improve their recommendations, akin to the evolutionary adaptation seen in natural organisms [

21].

The application of higher-order cybernetic principles enriches IoT and AIoT systems by introducing learning, co-evolution, and the integration of human users as active participants in feedback loops. This is particularly evident in adaptive learning platforms, where systems evolve their strategies based on student progress, fostering a symbiotic relationship between human learners and AI tutors. For instance, Kubotani et al. [

22] proposes a reinforcement learning-based adaptive tutoring system that models virtual students with fewer interactions, enhancing the learning experience through personalized instruction. Projects such as Cyborg Nest extend this interaction into the realm of sensory augmentation, where cybernetic implants merge biological and technological systems, enabling co-adaptive feedback loops that enhance human perception and decision-making. Cyborg Nest developed the North Sense, a semi-permanent body implant that vibrates when the wearer faces north, effectively providing a new sensory experience.

The notion of synthetic living systems aligns seamlessly with the evolution of IoT networks, where the behavior of devices increasingly mirrors that of living organisms. Swarm robotics, inspired by the collective intelligence of social insects, employs IoT-enabled communication and decentralized decision-making to achieve complex tasks such as search-and-rescue operations. These systems embody metacybernetic principles, operating collectively in ways that surpass the capabilities of their individual components. Living Architecture, another example, integrates IoT sensors and actuators into adaptive materials and designs, enabling buildings to respond autonomously to environmental changes. Walls equipped with IoT technology could dynamically adjust their thermal conductivity or transparency to optimize energy efficiency while catering to occupant preferences, reflecting an intersection of technology and synthetic life. While these advancements promise significant technological and societal benefits, they also necessitate careful consideration of ethical and sustainability implications. Reflexive IoT systems must navigate the complexities of data privacy and ethical decision-making, particularly when their autonomous actions impact human lives. Moreover, the adoption of nature-inspired principles in IoT design underscores the importance of minimizing resource usage and fostering sustainability, akin to the closed-loop efficiency observed in natural ecosystems. By embracing the principles of metacybernetics, IoT and AIoT systems are poised to transcend their traditional roles, evolving into dynamic, adaptable, and sustainable systems that not only emulate the complexity of living organisms but also align with human and ecological needs.

These diverse projects share a commitment to self-organizing structures that harness the power of collective intelligence to adapt, respond, and evolve. For instance, Collective Intelligence Platforms use decentralized networks where emergent behaviors facilitate collaborative decision-making and dynamic group adaptation [

3]. In the field of manufacturing, Holonic Manufacturing Systems demonstrate how decentralized control enables holons—semi-autonomous units—to self-organize to meet production demands, offering resilience and flexibility in the face of ever-changing conditions [

23]. These projects, along with many others, highlight the transformative potential of cybernetic principles in fostering adaptable, resilient systems that can respond to the complex demands of modern society.

Despite the significant advancements made in this area, current IoT frameworks still face significant challenges, as many systems struggle to maintain resilience across complex, multi-agent environments, where diverse components must interact in real time to address unpredictable events. To overcome these limitations, this paper introduces COgITOR [

24,

25], a novel fourth-order cybernetic physical system designed to simulate a cyberfluid state (a fluid with agents that have cybernetic properties) model within IoT. The COgITOR project addressed advanced reflexive mechanisms, holonomic memory and computing [

26], and energy-harvesting capabilities [

27] to establish a regenerative, adaptive, and resilient system—qualities often found in natural ecosystems. COgITOR originally perceived the application of Pavlovian principles of learning to its colloidal suspensions [

26], but in Cyberfluid media this has been superseded by the ideas of process intelligence that derives from Piaget’s concept of Operative Intelligence, and reframed as Varela’s [

11] and Maturana and Varela’s [

28] autopoiesis.

Modelling COgITOR using the metacybernetics of an extended MAT framework conceptualizes it as a fifth-order cybernetic model that we shall call Cogitor5. This shift reflects the idea of collective intelligence as a dynamic, adaptive system, providing a transformative approach for intelligent systems that aligns with the principles of living, adaptive networks. Simulating cyberfluid media offers a new paradigm for IoT development, setting a higher standard for resilience and adaptability. Through its integration of Cogitor5, cyberfluid media can offer scalable, self-regulating systems that can meet the demands of increasingly complex environments.

Cyberfluid media aligns IoT systems with evolutionary, emergent processes. This integration of Cogitor5 through simulations offers an unprecedented opportunity to rethink how we conceptualize and design intelligent, adaptive systems—systems that can continuously evolve, adapt, and flourish even as they respond to future uncertainties.

The structure of this paper will develop in the following way. It begins with an exploration of COgITOR and its conceptualization of Quantization, laying the foundation for understanding the dynamics of complex systems within the context of Cogitor5. Next, the core cybernetic principles underpinning the Cogitor5 modelling process will be introduced, demonstrating how feedback mechanisms, self-regulation, and adaptability can be integrated into IoT systems. This leads to a discussion of metacybernetic modeling, which provides a higher-order framework that enables more dynamic, self-organizing behaviors within intelligent systems. The paper will then focus on the concept of agency character, examined through MAT. Finally, the paper will draw a comparison between self-morphing in Cogitor5 and the adaptability of stem cells, illustrating how IoT systems, like biological entities, can reorganize and evolve to meet new challenges. This progression aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of how advanced cybernetic principles can transform the design and functionality of IoT systems, enabling them to operate as dynamic, resilient, and self-adaptive systems capable of responding to complex, ever-changing environments.

2. COgITOR

COgITOR is an advanced cybernetic framework designed as a fourth-order regenerative agency, capable of dynamically responding to a diverse range of stimuli, particularly of electric nature, and includes conventional liquids as solvents, solid nanoparticles as dispersoids, and eventually gels, all confined within a soft artificial skin [

29]. Its adaptability allows COgITOR to function effectively in complex and unpredictable environments. Based on the substrate principle of quantization, COgITOR emulates quantum-inspired behaviors by representing a complex adaptive system populated by nanoparticle agents interacting within a fluid medium. These agents remain autonomous and distinct, contributing to agency functionality by forming a responsive field of interaction that adapts to environmental demands. Furthermore, their nanometric dimensions induce the quantization of their electronic wavefunctions and opens the door to quantum phenomena [

30], particularly when using magnetic nanoparticles whose spins are free to fluctuate at room temperature [

31]. Such random arrangement of spins can enable average field anisotropies and can convey collective behavior, one example of which is the collective response of the magnetic colloid to an external magnetic field, well known to occur in ferrofluids [

32].

Inspired by biological cells, COgITOR mimics the decentralized, self-regenerative capacities observed in cellular systems. Each agent operates independently while engaging in sophisticated inter-agent communication, akin to intercellular interactions, enabling the system to dynamically self-organize. Operating at the nanoscale, agents' behaviors are influenced, as said, by quantum effects. This unique dynamic enables agents to perform a range of tasks, including pressure sensing [

33], computation [

34], data storage [

35], and energy harvesting [

36]. When integrated with specialized electronics, COgITOR's infrastructure supports advanced robotics and a wide array of applications that rely on precise and adaptive functionality.

Changes at the nanoscale ripple through the COgITOR system, enhancing adaptability through non-linear dynamics. Reflexive feedback loops further bolster this adaptability, allowing COgITOR to self-repair and maintain efficacy even in extreme conditions, such as intense magnetic fields and ionizing radiation, conditions found in space [

37]. Its self-healing architecture ensures resilience by fostering coevolutionary dynamics among agents, creating an ecosystem-like stability characterized by emergent properties like those observed in natural ecological systems.

Designed to withstand challenging environments, COgITOR's distributed, self-healing architecture is designed to enhance fault tolerance, creating effective performance even within volatile environments. The agents maintain complex patterns of interaction, where minor changes at the nanoscale can trigger significant agency responses. Through quantum phase coherence, agents self-organize in reaction to environmental shifts, forming stable configurations that mirror the resilience found in ecosystems. Transitions between these configurations are guided by discrete quantum energy states, reinforcing adaptability and responsiveness. Minor shifts in the quantized energy of a nanoparticle can influence its magnetism, conductivity, and / or optical properties, having influences throughout the system and impacting agency behavior. This cross-scale interaction underscores COgITOR's deterministic chaotic and fractal structure [

37], where small, localized changes can lead to far-reaching effects that enhance system adaptability.

An important emergent property of COgITOR's quantum-driven interactions is its capacity to represent agent coevolution. This dynamic facilitates adaptive interactions between various species of colloidal and nanoparticle agents, paralleling ecological processes in natural systems. In complex environments, agents not only inhabit their surroundings but actively shape them through mutual interactions, creating a neoecosystem (rather than just an ecosystem that does not necessarily suggest complexity). This interplay fosters stability and resilience, allowing the agency to respond robustly to environmental fluctuations.

The intricate nature of these systems is amplified by their non-linear dynamics. Minor disturbances can have significant consequences, complicating predictions about agency responses to external stresses. This unpredictability highlights the importance of a coevolutionary understanding to maintain agency neoecological balance. Reflexivity is central here, allowing the system to enhance or mitigate changes and thereby improve adaptability. Through these coevolutionary interactions, agents collectively reinforce resilience, ensuring a robust and flexible structure.

These interactions reflect neoecological dynamics, where agents influence each other through entanglement and superposition, adapting via mutual quantum-state modifications. This coevolutionary process yields emergent properties, in other words system-wide characteristics arising from collective interactions rather than isolated actions. Consequently, COgITOR's stability is reinforced, augmenting its ability to adapt swiftly to environmental shifts. This emergent behavior also facilitates the development of novel properties that can enhance its viability in changing environments.

3. Metacybernetics

The cybernetics of complex systems is an appropriate approach to model relationships among diverse entities [

38]. At its core, neoecology examines how different agencies, each defined by their respective populations of agents, interact not only with one another but also with the environment that surrounds them. This derives from a paradigm known as third order cybernetics [

13,

39]. The perspective that this approach generates extends into the realm of neoecology, which pushes the boundaries of traditional biological study by embracing the principles of complexity. Neoecology offers a broader representation of life by framing ecosystems in terms of complex adaptive systems that exhibit dynamic and evolving behaviors.

In this context, a diverse population of agents that share relatable structural and functional characteristics can be classed as an agency population. Agency extends beyond mere categorization, however, as it may contain distinct characteristics that allow for the differentiation of sub-populations. This differentiation leads to the definition of species within an agency ecosystem. Neoecosystems deepen this exploration by emphasizing the necessity of moving beyond solely biological frameworks, thereby incorporating the potentially vast complexities of adaptive systems that govern interactions among various entities.

Agencies can exist as part of a larger neoecosystem or are themselves defined as neoecosystems through their populations of agents. A neoecosystem, by definition, is not static but rather a dynamic community composed of these autonomous agencies, each interacting with one another and with their physical surroundings. This interplay facilitates interactive influences where agents affect each other's behaviors and the broader dynamics of the neoecosystem. Agencies function through autopoiesis, described by biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela [

28]. An agency, functioning as an avatar of a complex adaptive system, embodies the characteristics of a generic living system defined by its capacity for self-production. This concept emphasizes that even as agencies maintain their unique identities, they are also engaged in the ongoing processes that allow them to sustain themselves, adapt, and flourish.

While an environment may have a plurality of agencies, focusing specifically on one reveals the complex inner automatisms that define its existence. Here, understanding the internal processes, adaptive mechanisms, and interactions with its immediate environment becomes paramount. Each agency, despite functioning as a complex adaptive system, remains responsive to external stimuli. This responsiveness illustrates the agency’s ability to evolve and adapt, illustrating the dynamic interplay between its innate processes and the influences of the surrounding world.

The study of these interactions through cybernetics explores the information structures and processes associated with control and behavioral trajectories and outcomes. Cybernetics is inherently transdisciplinary, concentrating on systems and reflexivity, and investigating various self-attributes like self-regulation and self-reflection. Neocybernetics advances this discourse by focusing specifically on complex adaptive systems and their emergent behaviors. It emphasizes the mutual interactions and feedback loops among agents, unveiling the underlying dynamic structures and processes that enable self-organization within these systems.

Metacybernetics is a theory that embraces ontological distinct cybernetic orders, where the highest agency order is indicative of the paradigm that drives it. Ontology is divided into ordinary and fundamental realms [

40]. Ordinary ontology pertains to the tangible entities we encounter daily, pertaining to the physical space-time. In contrast, fundamental ontology ventures into more abstract territory, examining the underlying principles and abstract entities that form the foundation of existence itself, including consciousness. This distinction allows philosophers to deal with the concrete and the conceptual, bridging the gap between what we can see and touch and what exists beyond sensory perception.

The relationship between ordinary and fundamental ontology can be manifested in complexity, as embraced by critical realism, by distinguishing between the realms of superstructure and substructure. This is illustrated by Bhaskar [

41] who introduces the concept of transcendental realism, which seeks to resolve traditional philosophical problems by differentiating the empirical from the real, and the observable from the underlying mechanisms. Bhaskar's critical realism posits that our understanding of reality is stratified, with different layers of mechanisms and structures that underpin observable phenomena.

By distinguishing between ordinary and fundamental ontology, critical realism acknowledges the multi-layered nature of reality, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis of both the empirical world and the deeper, often unseen structures that govern it. This framework provides a robust methodology for exploring how the visible and tangible aspects of our world (superstructure) are influenced by the underlying, often abstract principles (substructure) that form the basis of existence. Bhaskar's work enables philosophers to bridge the gap between the tangible and the conceptual, enhancing our understanding of both realms through a unified approach.

The superstructure, grounded in ordinary ontology, encompasses the tangible elements that define our experiences, such as the physical structures we perceive and interact with continually. In contrast, the substructure aligns with fundamental ontology, representing the intangible foundations underlying these tangible realities. Together, they form a hierarchical system: substructural hierarchies signify levels of control, while the superstructure reflects varying levels or focuses of activity. Critical realism provides a valuable means of examining the interactions between empirical reality (what can be observed and measured), actual reality (what exists independently of observation, particularly as evidenced by quantum field theory and quantum mechanics), and the often-hidden causal mechanisms driving these phenomena. This framework underscores the layered complexity of existence, where multiple strata of reality influence and shape one another. The distinction between tangible and intangible structures is central to this understanding. The tangible includes everything we can physically observe, measure, or experience, from material objects to measurable phenomena. Conversely, the intangible represents what cannot be directly measured or observed but underpins and informs the tangible.

4. Cybernetic Orders and Metacybernetic Model

The word cybernetics has a proto-Indo-European origin, and recalls the concept of governing; its first documented occurrence goes back to Plato (Πλάτων, 346 B.C.), in ancient Greek: κυβϵρνητική τεχνη, literally the art of the pilot. It is an interdisciplinary field focusing on control and communication through information flow through reflexivity [

42]. In complex systems, it can represent adaptive and non-deterministic interactions, yielding insights into how such systems evolve and respond to their environments. Ontologically organized into orders of cybernetics that add layers of meaning to a system's operational framework, the principle of parsimony guides which order a cybernetic system might take, considering that the simpler explanation of its control and information processes might be the best option.

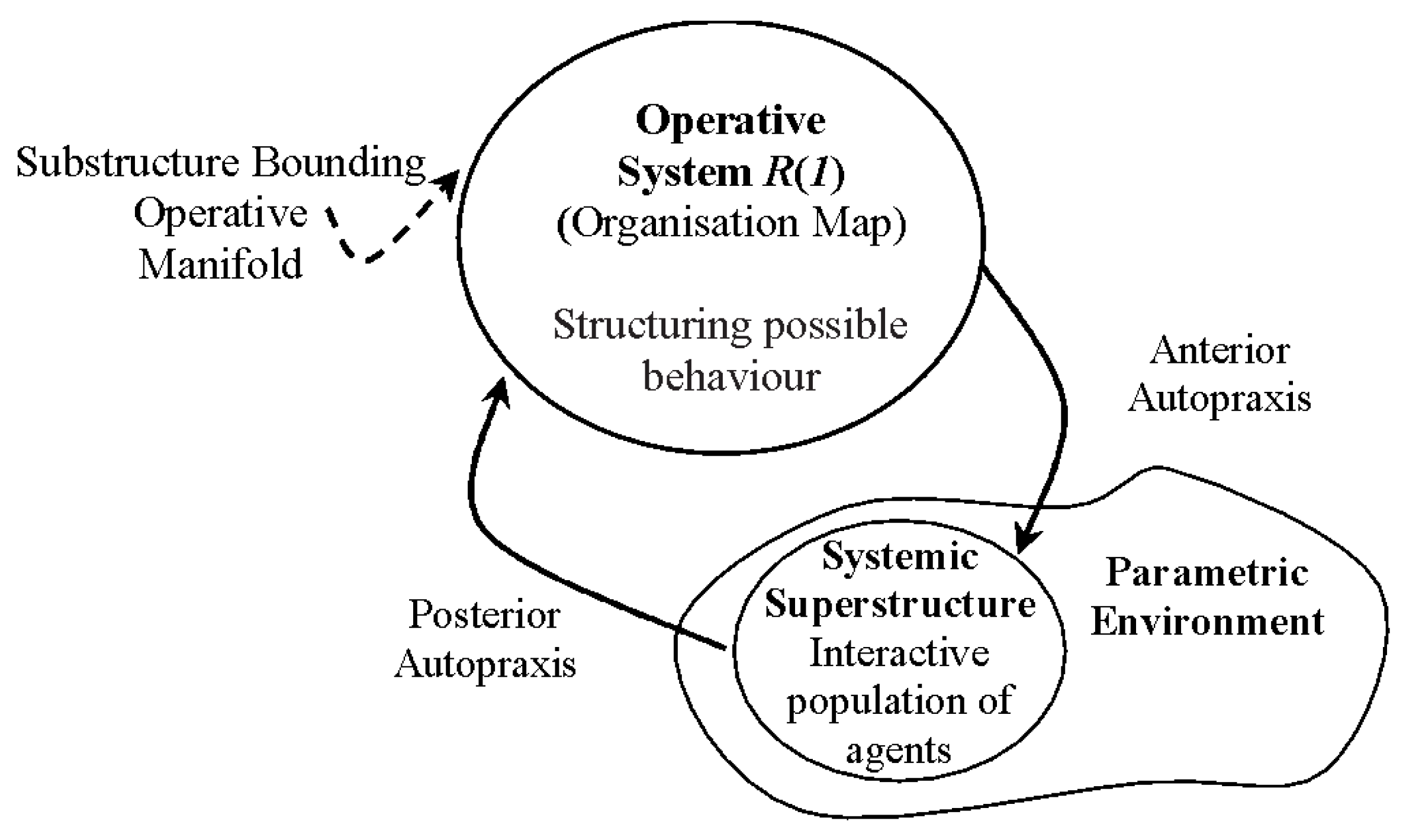

First-order cybernetics emphasizes the agency interactions with external control mechanisms that regulate inputs and outputs to ensure stability, and was introduced by Wiener [

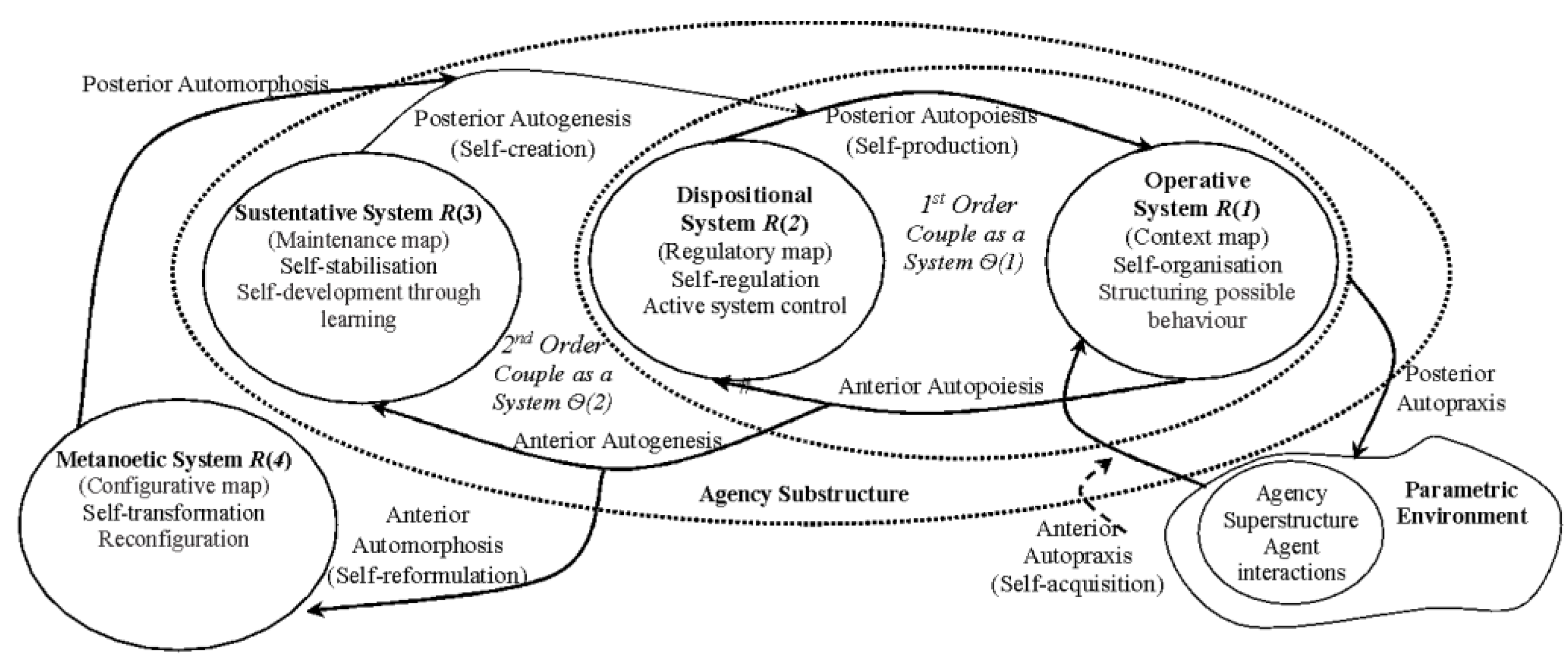

42]. In this order, the referent system R(1) operates as a closed loop, responding to external stimuli without self-awareness or understanding of its environment. The participating observer acts only as an external influence, limited to agency monitoring and control. This cybernetic order has an operative system that defines a potential for possible behaviors conforming to a set of intangible rules, this behavior manifesting in the superstructure. This system is governed by substructural information that arises as rule, superstructurally manifested through its operative shell. Events within the superstructure reflect the underlying information structure and respond dynamically to environmental parameters (such as temperature and humidity) that affect system behavior. Interactive agents engage and adapt within the superstructure, shaping outcomes through interdependent relationships. The operative system engages with what we shall call autopraxis that refers to the influence on the agency or on the environment on agency (see

Figure 1). It has a dual trajectory: posterior autopraxis indicates the agency influences on the environment through its agents; anterior pragmatosis is the reverse reflexivity. As an illustration, a geological system has the agents of topography, geology, and hydrology that deliver a first-order control mechanism regulating water flow within a river basin. The topology directly influences the movement of water. Geology directly influences the environment's permeability, erosion, and channel formation, affecting how water interacts with the underlying rock formations and sedimentary deposits. Hydrology governs the processes through which water moves within the landscape, including precipitation, evaporation, infiltration, runoff, and groundwater flow, influencing the overall water balance and distribution within the basin. Environmental influences like temperature and humidity influence the way in which agency behavior develops.

Second-order cybernetics shifts focus to the symbolic observer’s role in shaping agency internal states, orientation, and behavioral potentials, highlighting the interplay between internal dispositions and external influences, and was introduced by H. von Foerster [

43]. In this cybernetic order, in addition to the operative system R(1) there is a dispositional system R(2) which provides regulatory and trajectorial control transferred to the operative system through autopoiesis. The model highlights the operational dynamics that facilitate self-regulation and adaptive behavior. Agents interact within the supersystem guided by the rules of the operative system. The couple between disposition and the operative system is defined by Ѳ(1), a system in its own right, with dispositional and operative parts forming an interactive dynamic couple. It provides a pattern/fractal for higher-order cybernetics. Autopoiesis is normally identified with living systems, but this 2

nd order model can only function instrumentally—driven by external stimuli while operating within predefined regulatory strategies. There is no self-consciousness involved in this layer. An example of a second-order cybernetic system is Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Third-order cybernetics introduces the concept of sustentation, emphasizing the homeostatic maintenance of the system through reflexive processes that govern its states and dynamic relationships within the meta-system influence, and was introduced by V. Lepskiy [

39]. In this cybernetic order, the sustentative system R(3) sustains or maintains agency, providing support and enabling viability. Though second-order cybernetics systems have been argued to represent living systems through autopoiesis, following Eric Schwarz [

13], they require third-order functionality where there is sufficient complexity. Additionally, all agency systems in the ontological hierarchy require adaptive learning, delivered by process intelligence. Adaptive learning is a recursive process that reformulates agency aspects and control structures across multiple levels of the agency hierarchy, enhancing the capacity of agency to adapt, develop, and even evolve in response to internal and external dynamics. Areas of pragmatic application and situational diagnosis of this model have included the market economy, viruses, modelling consciousness, ecosystem dynamics, personality mindsets, and organizational mindsets, all seen as living systems. An example is any living system, like a biological stem cell, a social organization, or Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) when and if it becomes available.

Fourth-order cybernetics is concerned with metanoesis, where reflexivity facilitates profound structural transformations, leading to a fundamental shift in the system’s self-concept and orientation, and was introduced into physical systems by Chiolerio [

29]. Fourth-order cybernetics are "Metanoetic," a term that derives from the Greek word "metanoia" meaning transformation or reformulation. It regulates at a higher order level the Ѳ(2) system which in turn regulates the Ѳ(1) system. The term automorphosis refers to the agency ability to self-reformulate as it changes its structural form. An example might be the COgITOR colloidal system. However, setting COgITOR within a 5

th order metacybernetic frame results in a 5

th order model, Cogitor5.

Figure 2.

A Fourth-Order Cybernetic Agency with 4 ontologically Independent Systems of Control.

Figure 2.

A Fourth-Order Cybernetic Agency with 4 ontologically Independent Systems of Control.

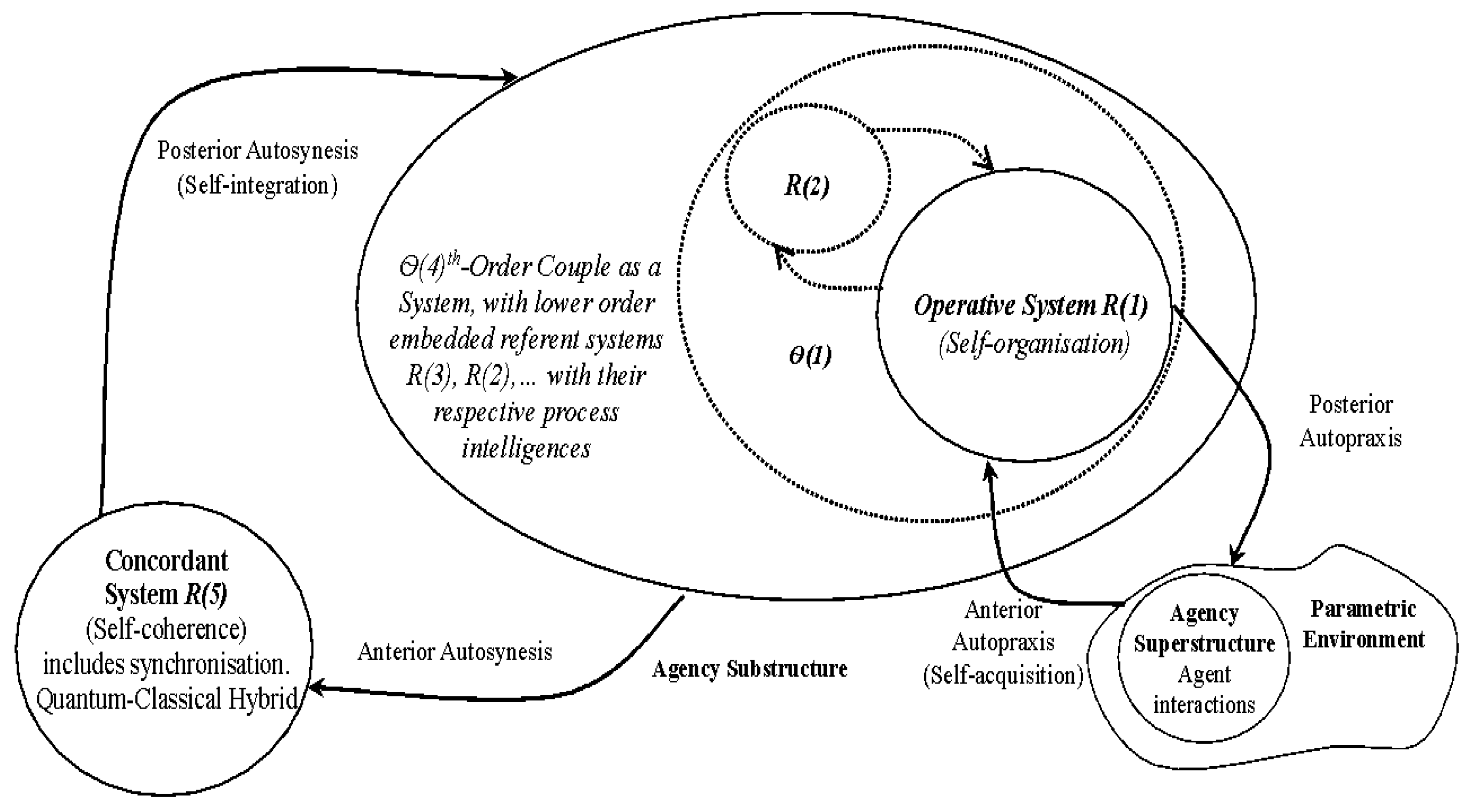

5. A Fifth-order Cybernetic Agency: Cogitor5

In this theory our ontological interest focuses on the fifth-order cybernetic agency. Each system in the hierarchy is called a referent system symbolized by R(n), where n= 1,2,3,… and where in our case n=5. The highest order in a cybernetic agency satisfies the Holographic Principle [

44] which derives from quantum information theory. A higher-order system embodies the concept of a boundary that encapsulates information about the lower systems. This boundary is a holographic screen that represents how the overarching control and organizational structure of the agency can inform and regulate the behaviors and interactions of its constituent lower systems. By aligning with the Holographic Principle, which posits that information in a higher-dimensional space can be represented in a lower-dimensional boundary, this model emphasizes the interconnectedness and interdependence of various levels of agency. In Cogitor5, the higher-order referent system R(5) defines the nature and meaning of agency containing information about the lower systems and governs their functions and adaptations, illustrating how complex behaviors emerge from the interactions at different levels of the hierarchy. This arises from a Principle of Information Parsimony which argues that a system in a hierarchy contains only the essential information required for control and communicative information flow of the systems hierarchically below it, ensuring that each lower system only processes the information relevant to its immediate function. This distribution prevents information overload and fosters more efficient operation, enhancing self-regulation and adaptability. Thus, the higher-order system acts as a holographic representation of the entire agency, capturing the essence of the interactions and information flow within the system hierarchy while optimizing information processing at every level through this parsimonious principle. Each system in the system hierarchy is populated by specialized agents responsible for their local agency control processes.

Fifth-order agencies operate at an intangible level as information fields that regulate coherence, synchronization, and adaptability within complex systems. Inspired by the work of authors like John von Neumann and Roy Frieden, these systems leverage the power of information to shape their behavior and evolution. Fifth-order systems can exhibit emergent properties and adapt to changing conditions by treating information as a fundamental entity. Cogitor5 draws on principles from quantum mechanics, information theory, and statistical physics to acquire intrinsic information that will permit efficacious process intelligence performance, while acting as a hybrid connector between the quantum and classical realms.

Drawing upon recent advancements in Informational Realism [

45], particularly the Fisher Information Field Theory, we propose that Cogitor5's phase space model serves as the critical boundary where the holographic principle operates. This allows the fifth-order system to access both classical and quantum dimensions. Specifically, since quantum processes occur within the corporeal (C) field, as elaborated by Yolles [

45], Cogitor5's boundary condition provides it with unique access to both classical and quantum phenomena, facilitating a more comprehensive approach to collective intelligence.

The highest-order system within this agency is concordance, conceptualized here as a metaphorical meta-bosonic control field. Concordance functions holographically, simulating a high-level quantum-inspired information model that governs coherence and synchronization across both quantum-like and classical systems. For this system to act as a meta-bosonic field, it must be understood as a control layer that harmonizes principles of quantum behavior with the classical mechanics underpinning agency. This system engages algorithmic representations to emulate requisite quantum phenomena such as entanglement (interconnectedness across distances), coherence (consistent phase relationships), and superposition (simultaneous multi-state existence) within a scalable, multi-level cybernetic framework. In the limit that brings to classical physics, the concordant system R/5) falls back into the Parametric Environment responsible for Autopragmatosys, while in the case of a pure quantum physical system, it adds a totally new layer, whose possibilities encompass phenomena that are not necessarily described in the Agency Superstructure.

To understand the notion of a meta-bosonic field, consider that a bosonic field is mediated by particles (bosons) that possess unique properties, such as the ability to occupy the same quantum state and exhibit collective coherence [

46,

47]. For example, in a laser, photons (which are bosons) are in a collective state, and their phase remains coherent, producing their characteristic coherent light. Similarly, a meta-bosonic field serves as a synchronization mechanism, orchestrating coherence across the system’s hierarchical structure. This orchestration is achieved through algorithms that govern lower-level structures by creating imperatives for action, which flow through the system’s process intelligences [

46]. These control imperatives enhance adaptive learning capacities and ultimately facilitate interactions across both quantum-inspired and classical domains [

47]. The concordance system thus functions as a dynamic, overarching structure, ensuring alignment and coherence throughout the agency’s operations. It is important to understand that this model operates at a conceptual level.

The fifth-order structure of the concordance system bridges quantum-inspired and classical elements, acting as a hybrid interface that transitions between purely quantum and purely classical domains. It facilitates complex interactions among colloidal nanoparticles, solvent molecules, and other agents. This design maintains coherence in lower-order systems by simulating entanglement-like relationships, ensuring synchronized states across the lower-level systems. By adapting principles from quantum information theory to a cybernetic context, the system enables consistent synchronization and adaptability throughout the hierarchy, promoting coherent communication among its simulated components. The concordance system embodies quantum-inspired features applied within its framework to support synchronized, adaptive behaviors of colloidal and nanoparticle agents:

● Entanglement Simulation: algorithms simulate entanglement-like coherence, allowing states to synchronize across hierarchies. This feature supports interconnected behaviors among agents, mirroring correlations found in actual quantum systems.

● State Flexibility: in this simulated environment, agents can occupy multiple potential states, allowing them to fluidly adjust to evolving system requirements. This flexibility enables colloidal and nanoparticle agents to adapt their functions responsively, reinforcing coherence across hierarchical levels without reliance on actual quantum dependencies.

● Collaborative Adaptability: the system promotes interactions that enhance adaptability, drawing inspiration from the functionality of quantum coherence in enabling collective organization. This collaborative adaptability helps agents align their actions with overarching system goals, ensuring coordinated behavior while maintaining the distinct functions of each order of agency.

Process intelligences play an important part in this model. Autosynesis, or self-integration, is the unification of various aspects of self into a whole, providing the concordance system with a framework for autonomous information processes. This enables cross-level coherence and adaptability through self-reflective integration. It does this through dynamic data integration, where autosynesis models continuous data aggregation and integration, maintaining coherence across system levels through feedback loops. This dynamic data integration enhances adaptive learning within the simulation.

Autosynesis also involves self-reflective agents that can assess outcomes through the frameworks provided by the concordance system, supporting self-directed adaptation that enhances overall coherence. Autosynesis is enabled, at a physical level, by reflective processes within coherent states experienced by the components of the system under study. These states facilitate a form of shared communication, rather than the directional communication we typically encounter in daily life. This shared communication operates according to the Principle of Information Parsimony.

An illustrative quantum analogy can be introduced by considering Schrödinger’s Cat. In quantum mechanics, Schrödinger’s Cat illustrates superposition, existing in multiple states until observed. Similarly, the agents of the concordance system can exist in several potential states, remaining “unactualized” until specific conditions necessitate a decision. This analogy draws on quantum superposition to highlight decision trajectories and complexity within the simulation. Emergence is also an attribute, especially with respect to decision-making. Emergence influences this by dynamically altering possibilities and boundaries within the classical components of agency. Examples include the superposition of options: like quantum uncertainty, the system maintains multiple potential outcomes, shaped by ongoing interactions among agents [

48]. Another is resolution through emergence, where emergent properties redefine options and adapt decision trajectories based on evolving interactions. This aspect is well known in physics as the symmetry-breaking condition [

49].

Interconnectedness and entanglement is another, where higher-level decisions reverberate through the system, enabling connectivity among physically separated agents [

48]. Environmental influence is also an important attribute, where inputs from the environment to the operative system are internalized at lower systemic levels, where they are assimilated (taken in) and accommodated (system restructuring) [

14]. Through this process, operative intelligences facilitate transitions from potential to actualized orientations and decisions at all levels, thereby supporting responsive and adaptive operative behavior.

The concordance system, as a hybrid interface, integrates quantum-like coherence with classical functionality, facilitating coherent interactions across simulated levels. Meta-strategies embedded in the system enable adaptive decision-making by evaluating multiple pathways and dynamically adjusting to uncertainty and change. This approach provides flexibility that surpasses traditional frameworks, leveraging emergent properties to guide decisions under complex conditions.

Figure 3.

A Fifth-order Cogitor5 Cybernetic Agency.

Figure 3.

A Fifth-order Cogitor5 Cybernetic Agency.

The fifth-order structure of the concordance system R(5) provides an important hybrid agency interface, blending quantum-inspired and classical elements. This maps complex interactions among agents enabling coherence and synchronization across various levels. Inspired by the work of von Neumann [

50] and Frieden [

51], the system uses information as a fundamental entity, enabling it to exhibit emergent properties and adapt to changing conditions. The interplay between order and chaos, guided by the system's underlying information structure, enables it to balance stability and innovation.

Autosynesis, a key concept within the concordance system, refers to the self-integration of various aspects of the system. This process empowers the system with a robust capacity for autonomous information processing, enabling cross-level coherence and adaptability. By continuously aggregating and processing information, autosynesis sustains coherence across system levels through feedback loops, enhancing adaptive learning. Agents within the system can assess and adapt their strategies over time, promoting self-directed adaptation and reinforcing overall coherence. By leveraging the power of information and embracing quantum-inspired principles, the concordance system offers a promising framework for designing, understanding and developing the complex systems of the future. This aspect is of paramount importance for the development of the AIoT systems, that could embed quantum devices and manifest a quantum coherent state.

The nature of the concordance system brings to mind bosonic properties which are evident in certain quantum systems. In quantum field theory, bosons are particles that follow Bose-Einstein statistics and can occupy the same quantum state, allowing for collective behaviors reminiscent of the coordinated actions mapped in the concordance system. This illustrates how agents can synchronize their behaviors, allowing for enhanced collective decision-making processes through mechanisms that emulate the interactions seen with bosons. Analogies to quantum mechanics are important in illustrating the simulated properties of this system. One prominent example is Schrödinger's Cat, which embodies the concept of superposition. Similarly, agents within the concordance framework can inhabit various potential states, remaining "unactualized" until specific conditions necessitate a decision. This reflects the intricate decision pathways that emerge in the simulations.

Emergence is another essential attribute informing decision-making. It allows for the dynamic redefinition of possibilities and constraints among classical components of agency, enabling agents to explore multiple potential outcomes. By maintaining a state of superposition (representing quantum uncertainty) agents benefit from the capacity to engage in complex interactions and adaptations. As emergent phenomena take shape, decisions resolve by reshaping options and trajectories based on evolving interactions. Additionally, the principles of interconnectedness and entanglement suggest that decisions made at higher-order levels are manifested throughout the system, ensuing connectivity among agents. Inputs from the environment become assimilated and tailored at lower levels, enhancing adaptive behaviors across all degrees of agency.

As a hybrid interface, the concordance system seamlessly blends quantum-like coherence with classical operational functionality, thereby enabling coherent interactions among its simulated levels. The incorporation of embedded meta-strategies bolsters adaptive decision-making through the evaluation of multiple pathways and the ability to react thoughtfully to uncertainties and changes in the environment. This strategic flexibility surpasses traditional frameworks, using emergent properties to guide decisions in complex situations. In this context, several process intelligences are at play, beside the already discussed Authosynesis. Autopraxis represents an agent’s ability to autonomously identify and integrate relevant information from its surroundings, enhancing decision-making processes and adaptability. Autopoiesis facilitates the ongoing operation and adaptation of the system by ensuring the production and maintenance of its components, with a focus on self-organization. Autogenesis describes a more advanced form of adaptive facilitation, linking operational and dispositional systems to foster the evolution and creation of new operational forms. Finally, Automorphosis reflects the agent's capacity for profound transformation, achieving heightened complexity or functionality in response to environmental changes. Notably, these process intelligences operate with both posterior and anterior orientations. The posterior orientation emphasizes sourcing relevant data, guiding agents to inform their adaptive behaviors effectively. In contrast, the anterior orientation focuses on R(n) structures, which are influenced by reflexive feedback. This proactive approach allows the system to anticipate potential scenarios based on current data trends and emerging factors, thereby enhancing performance in evolving contexts.

The interplay between these orientations fosters a dynamic environment where insights from source data and proactive adaptations converge. By leveraging both orientations, the concordance system enriches coherence and adaptability among its agents, ultimately reinforcing the overall efficacy of its framework. This integrative approach enables ongoing refinement of operational strategies, ensuring that agents remain responsive to both relevant data and the broader context. Consequently, the concordance system creates a resilient environment for navigating complexity, enhancing adaptability in the face of changing conditions.

6. Agency Character

Agency character can be pragmatically determined from various aspects, which are dimensions of functionality that construct it. According to Yolles [

10], these aspects are cognition, affect, and spirit. Cognition refers to the functionality of an agent, encompassing reasoning, information processing, and trajectory-formation or decision-making. It enables the agent to analyze its internal and external environments, interpret data, and make informed choices. Cognition provides the agency capacity for understanding, learning, and adapting to complex conditions. Affect, on the other hand, is the sentience functionality of an agent, representing its awareness and subjective experiences. It relates to the agent’s ability to respond to stimuli with valence (positive or negative emotional states) and arousal (intensity of emotional or physiological reactions). Affect influences an agent's adaptive responses and regulation of internal states in relation to external circumstances. Finally, spirit represents the balancing functionality of an agent, integrating cognition and affect to ensure coherence, stability, and adaptability. It reflects the agent’s capacity to maintain equilibrium between its cognitive and affective processes, facilitating long-term survival, trajectory formation, and overall coherence in its interactions with the environment.

In this framework, spirit can be understood as the orientation that guides the agent, while affect defines the trajectory, determining the nature of cognition. The integration of these elements—spirit as the direction and affect as the emotional energy or momentum—shapes the agent’s approach to decision-making, ensuring that its actions are not only reactive but also purposeful and adaptive in a dynamically changing environment. This dynamic interplay between cognition, affect, and spirit is fundamental for achieving a balanced and functional agency that adapts to both internal states and external challenges.

In considering human beings as agencies, we might ponder where consciousness comes from. Consciousness might arise from the synergy between cognition and affect, as described by Yolles [

52], where cognition processes information and affect provides emotional context, shaping the agent’s awareness and responsiveness to its environment. The interaction between these dimensions results in a level of consciousness that enables the agent not only to react to stimuli but to engage meaningfully with its surroundings. This synthesis is crucial for the agent to interpret, respond to, and adapt to environmental changes, driving the system’s evolution and ensuring its resilience in the face of dynamic challenges.

Through the recursive and emergent interactions of cognition, affect, and spirit, agency develops a dynamic, adaptive consciousness. This consciousness allows the agent to navigate uncertainty, make informed decisions, and evolve in response to its environment, achieving long-term stability and coherence. As the system interacts with external and internal forces, it continuously refines its behaviors, ensuring that its actions align with both immediate needs and long-term goals. This synthesis of cognitive processing, affective regulation, and spiritual orientation enables the agency to thrive within complex, changing environments, ensuring ongoing adaptability and evolutionary success. When referring to consciousness, it should be realized that this is not absolute, as explained by Bitbol and Luisi [

53], and later by Bielecki [

54] as shown in

Table 1. They argue that there are levels of consciousness that can range from some null conditions to some collective consciousness.

We might speculatively explore the relationships between the aspects of a clearly regenerative cell and the Cogitor5 agency, as shown in

Table 2. This provides a conceptual framework comparing two distinct types of agency, stem Cell and Cogitor5, examining how they exhibit adaptive behavior, responsiveness, and organizational coherence under complexity. By exploring these agencies, the table aims to illustrate how different entities, whether biological or synthetic, process information, react to environmental stimuli, maintain stability, and develop emergent properties akin to consciousness.

Stem Cell Agency is a biologically rooted model, highlighting cellular processes such as decision-making, environmental responsiveness, and self-regulation through biochemical interactions. This agency demonstrates a form of primitive cognition, “affect”, and coherence, where cellular responses align with the broader needs of organismal health. Stem cells showcase a rudimentary awareness, responding adaptively to damage and modulating their behavior according to biochemical signals. This biological foundation illustrates a form of agency that, while not conscious in the human sense, still demonstrates fundamental elements of awareness and adaptation.

In contrast, Cogitor5 Agency reflects a more abstract or cybernetic form of agency, potentially operating within a network or collective system. Rather than relying on biochemical pathways, Cogitor5 Agency adapts to its environment through interactions between its components, exhibiting self-organization and real-time data processing that resemble cognitive functions. This agency adjusts its organizational structure in response to environmental changes, achieving stability and long-term adaptability. Its emergent properties reflect a kind of “cyber-consciousness,” arising from the collective behaviors of its interacting agents, allowing it to respond dynamically and sustain itself over time.

Together Stem Cell Agency and Cogitor5 Agency reveal variations in which agency can manifest across biological and non-biological systems. The

Table 2 comparative approach, which also includes reference to the IoT, demonstrates how adaptive behavior, self-regulation, and emergent awareness are not exclusive to organic life, suggesting a broader definition of agency applicable to different complex system types. This framework thus serves as a foundation for understanding how cognition, affect, and organizational coherence enable complex adaptive responses across diverse entities.

In addition, we can conceptualize the core functionalities of IoT systems and align them with the three agency aspects as outlined in Mindset Agency Theory [

10], identified as cognition, affect and spirit [

55]. Concerning cognition, IoT systems are designed to process environmental data using interconnected sensors, actuators, and networks. This enables them to make decisions or respond intelligently based on input data. While IoT devices lack human reasoning, their capacity to process information and optimize responses reflects a form of cognition. In this context, cognition in IoT represents real-time data collection, processing, and decision-making facilitated by embedded algorithms. For example, IoT-enabled smart home devices such as thermostats adjust temperature settings based on real-time conditions, demonstrating algorithm-driven reasoning. Similarly, machine-to-machine communication (M2M) in IoT systems allows for emergent behaviors where devices work collaboratively to optimize outcomes, reflecting the adaptive decision-making of biological systems like stem cells or cybernetic systems like Cogitor5 agencies. Considering affect, though IoT systems are inherently non-sentient, exhibiting behaviors that can be analogized to affective responses. These systems dynamically adjust to external changes, showcasing characteristics akin to valence (stability vs. instability) and arousal (intensity of response). IoT devices adapt their operations to maintain stability, demonstrating a form of self-regulation in response to environmental stimuli. For instance, smart irrigation systems modify water flow based on soil moisture levels, reflecting the "arousal" dimension of their response. Similarly, adaptive traffic light systems adjust to congestion levels to optimize traffic flow, representing stability as a form of "valence." This dynamic feedback mechanism aligns with the functional role of affect in biological or artificial agents. Finally, the spirit aspect is concerned with balancing cognition and mindset. In IoT this refers to the capacity of IoT systems to balance cognitive functions (data-driven decisions) with affective responses (adaptive behaviors) to maintain overall system stability and functionality. This balance is achieved through interconnected networks and overarching frameworks that ensure coherence and adaptability in response to environmental demands. Examples include industrial IoT systems that optimize factory workflows by balancing production requirements with equipment maintenance needs, ensuring stability and efficiency. Similarly, smart grid technologies use real-time energy usage data and supply inputs to dynamically balance energy loads, maintaining system resilience and harmony. These examples highlight how IoT networks integrate diverse inputs and outputs to achieve a unified and functional system, paralleling the balancing role of spirit in biological and cybernetic systems.

In

Table 3 we outline how both stem cells and Cogitor5 Agency operate as living systems, each characterized by different levels of control and forms of process intelligence. These levels—operative, dispositional, sustentative, metanoetic, and concordance—represent distinct layers where each system organizes itself, adapts to its environment, and sustains coherence. This can be elaborated to include the IoT by considering alignment with the biological concepts described for Stem Cell Agency and then offering thoughtful analogies that bridge biological and technological systems. Providing the following rationale. The IoT entries effectively mirror the operative functions of stem cells, such as task execution, self-organization, and feedback-based adaptation. They emphasize real-time responses and interactions, which are substrate to IoT systems and stem cells. It also demonstrates how IoT systems can emulate the dynamic and adaptive behaviors of biological systems across different orders of complexity, from basic operations (1

st order) to higher-order transformation and integration (4

th and 5

th orders). By incorporating advanced concepts like quantum coherence (5

th order), the IoT entries show that technological systems have the potential to achieve levels of integration and synchronization analogous to hypothesized biological mechanisms. This provides a speculative yet scientifically grounded perspective on the future of IoT.

In

Table 4 we outline the types of process intelligence—autopraxis, autopoiesis, autogenesis, and automorphosis—that enable both stem cells and Cogitor5 Agency systems to function autonomously, adapt to their environments, and sustain ongoing development. This can be extended to IoT. For autopraxis, IoT sensors in system networks parallel stem cell data acquisition through receptors and the supportive role of the extracellular matrix, similar to the contextual framework provided by IoT networks. For autopoiesis, the self-maintaining and self-regenerative nature of IoT networks mirrors the resilience and adaptive self-organization of biological systems. For autogenesis, the concept of self-creation is reflected in IoT's ability to evolve through updates and reconfiguration, reflecting the adaptability seen in stem cells and Cogitor5 agents. Finally, automorphosis has a functional specialization in IoT systems that aligns with adaptive reorganization seen in biological processes, such as differentiation and environmental responsiveness. These entries maintain a logical progression, illustrating how IoT systems emulate and expand upon the capabilities of biological and synthetic agents.

5. Conclusions

The evolution of cybernetic theory has moved from the simple interaction between a system and its environment in first-order cybernetics to the self-regulating and adaptive behaviors in second- and third-order frameworks. The introduction of fourth-order cybernetics, with concepts like metanoesis and automorphosis, marks a significant shift toward systems capable of profound internal transformations. Fifth-order cybernetic agencies, like Cogitor5, represent a leap into quantum-inspired processes, embracing both quantum and classical principles to create highly synchronized, adaptable systems capable of responding to complex environments with quantum efficiency. This progression opens the door to highly advanced AIoT systems that can evolve in real-time, responding to dynamic conditions with heightened precision.

In this evolving framework, agency is defined through three core dimensions: cognition, affect, and spirit [

10]. Cognition pertains to reasoning and information processing, allowing agents to analyze data, make decisions, and adapt to complex environments. Affect relates to the emotional states and reactions of the agent, which influence its behavior and internal regulation. Spirit integrates cognition and affect, ensuring that the agent maintains stability, coherence, and adaptability in an ever-changing environment. This dynamic interplay between cognition, affect, and spirit is key to achieving functional agency, capable of responding effectively to both internal states and external challenges.

Consciousness, according to this framework, arises from the synergy between cognition and affect. It enables agents not only to react to stimuli but also to engage meaningfully with their surroundings, ensuring long-term stability and adaptability. The recursive and emergent nature of cognition, affect, and spirit fosters a dynamic, adaptive consciousness that evolves in response to environmental changes, ensuring the agent's survival and resilience.

A comparative analysis between Stem Cell Agency and Cogitor5 Agency illustrates how agency can manifest across both biological and cybernetic systems. Stem Cells exhibit a basic form of agency through biochemical interactions, self-regulating based on environmental stimuli. In contrast, Cogitor5 Agency operates in a more abstract, cybernetic domain, using real-time data processing and self-organization to adapt to complex environments. This comparison highlights that agency is not exclusive to organic life; it can extend to non-biological systems that exhibit cognitive, affective, and spiritual dimensions.

Furthermore, IoT systems reflect these same dimensions of agency. IoT devices process environmental data via interconnected sensors and algorithms, demonstrating a form of cognition through real-time decision-making and data-driven responses. While IoT systems do not possess human-like consciousness, their ability to process information and adapt to their environment reflects cognitive and adaptive agency behaviors. In the context of IoT, cognition manifests through data collection and processing, affect is reflected in the system’s response to environmental stimuli (e.g., smart thermostats adjusting temperatures), and spirit is seen in the system's ability to maintain stability and coherence through adaptive regulation.

By considering IoT systems through the metacybernetic theory, it becomes clear that agency extends beyond living organisms and can be found in diverse complex systems, demonstrating how cognition as information processing, affect as arousal and a degree of awareness, and spirit as transcendence (enhances viability by elaborating itself beyond its current state or constraints), wholeness, interconnectedness shape behaviors and responses across a variety of entities. Here then, for complex adaptive systems, spirit provides an orientation, and affect a platform on which cognition occurs to enhance system viability.

Author Contributions

All Authors contributed equally to all aspects: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization; project administration, funding acquisition, A.C.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Innovation Council and SMEs Executive Agency (EISMEA), grant number 964388.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used GPT-4.0 for the purposes of improving the readability of some elements of the paper. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Marengo, A. Navigating the nexus of AI and IoT: A comprehensive review of data analytics and privacy paradigms. Internet of Things 2024, 27, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, H.S. Review of the book The Meaning of Intelligence, by G.D. Stoddard. J. Consult. Psychol. 1943, 7(6), 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, T.W.; Bernstein, M.S. Collective intelligence: Merging the insights of people and machines. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 56(2), 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Daraojimba, E.C.; Nwasike, C.N.; Adegbite, A.O.; Ezeigweneme, C.A.; Gidiagba, J.O. Comprehensive review of agile methodologies in project management. Comput. Sci. & IT Res. J. 2024, 5(1), 190–218. [CrossRef]

- Miguel, J.; Caballé, S.; Xhafa, F. Intelligent Data Analysis for e-Learning: Enhancing Security and Trustworthiness in Online Learning Systems; Academic Press (Elsevier): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; 192 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Yolles, M.I.; Fink, G. A Configuration Approach to Mindset Agency Theory: A Formative Trait Psychology with Affect, Cognition & Behaviour; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, H.A. The architecture of complexity. Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 1962, 106(6), 467–482. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Michaud, E.J.; Baek, D.D.; Engels, J.; Sun, X.; Tegmark, M. The geometry of concepts: Sparse autoencoder feature structure. arXiv e-Print 2024, arXiv:2410.19750. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.19750 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Yolles, M. Metacybernetics: Towards a general theory of higher order cybernetics. Systems 2021, 9(2), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M. The cybernetics of ecology. In Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Chapter 1, pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F.J. Principles of Biological Autonomy; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F.J. Organism: A meshwork of selfless selves. In Organism and the Origins of Self; Tauber, A.I., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, E. Autogenesis.. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3826203, April 14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children; International Universities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Yolles, M.; Frieden, R. Viruses as living systems—a metacybernetic view. Systems 2022, 10(3), 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M. Debates on the nature of artificial general intelligence. Science 2024, 383(6689), eado7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oca, A.; Cosmas, A.; Tunasar, C.; Shah, K.; O’Neil, L. Using digital twins to unlock supply chain growth. McKinsey & Company, 20 November 2024. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/digital-twins-the-key-to-unlocking-end-to-end-supply-chain-growth (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Chappell, J.H. Artificial Intelligence: From Predictive to Prescriptive and Beyond; InSource Solutions White Paper: May 2020. Available online: https://insource.solutions/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/WhitePaper_AIfromPredictivetoPrescriptiveandBeyond-EN.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Bo, C.; Jianhui, W.; Xiaonan, L.; Chen, C.; Shijia, Z. Networked microgrids for grid resilience, robustness, and efficiency: a review. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2020, 1(12). [CrossRef]

- Popovic, M. Redundancy in communication networks for smart grids. PhD Thesis, 2016 6973 EPFL.

- Garg, S.; Pundir, P.; Jindal, H.; Saini, H.; Garg, S. Towards a multimodal system for precision agriculture using IoT and machine learning. arXiv e-Print 2021, arXiv:2107.04895. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.04895 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Kubotani, Y.; Fukuhara, Y.; Morishima, S. RLTutor: Reinforcement learning-based adaptive tutoring system by modeling virtual student with fewer interactions. arXiv e-Print 2021, arXiv:2108.00268. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.00268 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Holonic Manufacturing. Available online: https://holonicmanufacturing.com (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- H2020-FETOPEN-2018-2019-2020-01 programme. COgITOR: A new COlloidal cybernetic sysTem tOwaRds 2030. Available online: https://www.cogitor-project.eu (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Cowing, K. COgITOR: The liquid cybernetic system inspired by cells. Astrobiology 2021, 6 September. Available online: https://astrobiology.com/2021/09/cogitor-the-liquid-cybernetic-system-inspired-by-cells.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Chiolerio, A. Colloid intelligence. In Proceedings of the SPIE—Bioinspiration, Biomimetics, and Bioreplication XIV, Long Beach, CA, USA, 25–28 March 2024; Proc. SPIE PC12944, PC1294406. 17 May 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bevione, M.; Chiolerio, A.; Tagliabue, G. Plasmonic nanofluids: Enhancing photothermal gradients toward liquid robots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15(43), 50106–50115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maturana, H. R.; Varela, F. J. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Chiolerio, A. Liquid cybernetic systems: The fourth-order cybernetics. Adv. Intell. Syst. 2020, 2, 2000120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Jai Kumar, B.; Mahesh, H. M. Quantum nanostructures (QDs): An overview. In Synthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials: Advances and Key Technologies, 1st ed.; Bhagyaraj, S., Oluwafemi, O. S., Kalarikkal, N., Thomas, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 59–88. [Google Scholar]

- Allia, P.; Coisson, M.; Tiberto, P.; Vinai, F.; Knobel, M.; Novak, M. A.; Nunes, W. C. Granular Cu–Co alloys as interacting superparamagnets. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 144420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, L.; Chiolerio, A. The magnetic body force in ferrofluids. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2021, 54(35), 355002. [CrossRef]

- Chiolerio, A.; Adamatzky, A. Tactile sensing and computing on a random network of conducting fluid channels. Flex. Print. Electron. 2020, 5(2), 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolerio, A.; Garofalo, E.; Phillips, N.; Falletta, E.; de Oliveira, R.; Adamatzky, A. Learning in colloidal polyaniline nanorods. Results Phys. 2024, 58, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolerio, A. , Garofalo, E., Phillips, N., Falletta, E., de Oliveira, R., & Adamatzky, A. Learning in colloidal polyaniline nanorods. Results in Physics 2024, 58, 107501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolerio, A.; Garofalo, E.; Bevione, M.; Cecchini, L. Multiphysics-enabled liquid state thermal harvesting: Synergistic effects between pyroelectricity and triboelectrification. Energy Technol. 2021, 9(10), 2100544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolerio, A.; Quadrelli, M. B. Smart fluid systems: The advent of autonomous liquid robotics. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4(7), 1700036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M.; Rautakivi, T. Diagnosing complex organizations with diverse cultures—Part 1: Agency theory. Systems 2023, 12(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepskiy, V. Evolution of cybernetics: Philosophical and methodological analysis. Kybernetes 2018, 47(2), 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moltmann, F. Levels of ontology and natural language: The case of the ontology of parts and wholes. In The Language of Ontology; Miller, J. T. M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; Chapter 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, R. A Realist Theory of Science; Leeds Books Ltd.: Leeds, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961 (1st ed. 1948).

- Foerster, H. von, Ed. Cybernetics of Cybernetics: Or, the Control of Control and the Communication of Communication, 2nd ed.; Future Systems, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fields, C.; Glazebrook, J. F.; Marcianò, A. The physical meaning of the holographic principle. Quanta 2022, 11, 72–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M. I. Informational Realism: The Fisher Information Field Theory. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5254750 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Peskin, M. E.; Schroeder, D. V. An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory; Perseus Books: Reading, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Srednicki, M. Quantum Field Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A.; Podolsky, B.; Rosen, N. Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambu, Y.; Jona-Lasinio, G. Dynamical model of elementary particles based on an analogy with superconductivity. II. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics (R. T. Beyer, Trans.; original work published 1932); Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1955.

- Frieden, B.R. Science from Fisher Information: A Unification, Revised ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yolles, M.I. Consciousness, sapience and sentience—A metacybernetic view. Systems 2022, 10, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitbol, M.; Luisi, P.L. Autopoiesis with or without cognition: Defining life at its edge. J. R. Soc. Interface 2004, 1, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecki, A.; Schmittel, M. The information encoded in structures: theory and application to molecular cybernetics. Foundations of Science 2022, 27(2). [CrossRef]

- Yolles, M. Diagnosing market capitalism: A metacybernetic view. Systems 2024, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streltsov, A.; Adesso, G.; Plenio, M.B. Colloquium: Quantum coherence as a resource. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2017, 89, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]