1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a significant and devastating public health issue ranked top among notifiable parasite infections [

1]. It is caused by flagellate protozoa of the genus

Leishmania, which are transmitted by phlebotomy insects [

2]. Leishmaniasis is widespread in about 100 countries, and the population at risk is estimated to be around 350 million [

3]. There are three clinical types of Leishmaniasis, depending on the species: localized cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), and visceral leishmaniasis (VL). CL is the most common clinical manifestation worldwide, affecting 12 million people and adding about 2 million new cases annually [

4]. Furthermore, Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Iran, Pakistan, Peru, Saudi Arabia, and Syria account for 90% of all cases worldwide [

5]. In Algeria, three common species are encountered:

L. infantum, which causes the CL and VL forms of the disease in the northern part of the country;

L. killicki, which causes the CL form in Central Southern Algeria (Ghardaïa region), and

L. major, which is spread in the Central Eastern region of Algeria, with the M'Sila province being the most affected [

6].More than a quarter of a million (252,659) cases of CL were registered in the country between 1982 and 2017 in five provinces (Bechar, El Oued, Batna, Biskra, and M'Sila), accounting for more than 70% of the total number of cases [

6]. Given the epidemiology of leishmaniasis, the scarcity of treatment and the severe side effects of existing drugs such as amphotericin B and pentamidine, the lack of successful vaccines, and the lack of interest from major pharmaceutical companies, finding new molecules with leishmanicidal activity has become an urgent challenge [

7]. As a result, a global program for the prioritized assessment of natural products against the various forms of leishmaniasis is in demand [

3]. Ethnopharmacological knowledge is a holistic systems approach that can create better, safer, more accessible, and sustainable medicines [

8,

9]. It is also worth noting that despite numerous published works over the last decade exploring the diversity of ethnopharmacological research in Algeria [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], only three papers reported on the medicinal plants used for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Algeria [

28,

29,

30]. Besides, the antileishmanial activities of medicinal plants from Morocco and Tunisia have shown that natural products may inhibit the growth of several

Leishmania species, such as

L. major (cutaneous leishmaniasis) and

L. infantum (visceral leishmaniasis) [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

In the last decades, the use of multivariate analyses in various ethnosciences has risen significantly, allowing for quantitative examinations of various topics linked to traditional knowledge and its applications [

37]. In 1979, Moerman outlined the first strategy, which was used for Native American medicinal plant utilization [

37]. The author proposed the first statistical multiple linear regression model between two variables, tested the hypothesis that medicinal usage is a function of generic and particular availability, and found significant selectivity in plant use. The multivariate approaches are particularly beneficial for understanding the exploitation of biodiversity in ethnomedicinal systems, demonstrating that selecting valuable taxa may be explained by objective criteria rather than being driven by chance [

38]. Höft

et al. (1999) described the application of multidimensional approaches in the ethnobotanical area for the first time. The study's objective is to determine these statistical methodologies to identify the similarity of patterns between indigenous people and local plants [

39]. These methodologies have been investigated to analyze the ethnobotanical data set, including the description of traditional knowledge and the relevance of use by different ethnic, social, or gender groups [

39]. Seven years later, this novel strategy was utilized to determine the specificity of the link between the plant species employed for treating type 2 diabetes by the Cree Nation, the native people in Quebec [

40]. There is a constant increase in studies focusing on using these methodologies in ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology [

41,

42,

43,

44].

According to the reviews conducted by this group, no studies have highlighted the multidimensional elements of CL correlating with ethnopharmacology and ethnobotany data in Algeria. As a result, there is a clear need to develop a new approach to ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological research in Algeria.

Consequently, the objectives of this study were (a) to use multivariate analyses to investigate the association between medicinal plants used by herbalists, (b) to evaluate the most frequently used species, and (c) to investigate factors associated with the CL's traditional knowledge in northeastern Algeria.

2. Materials and Methods

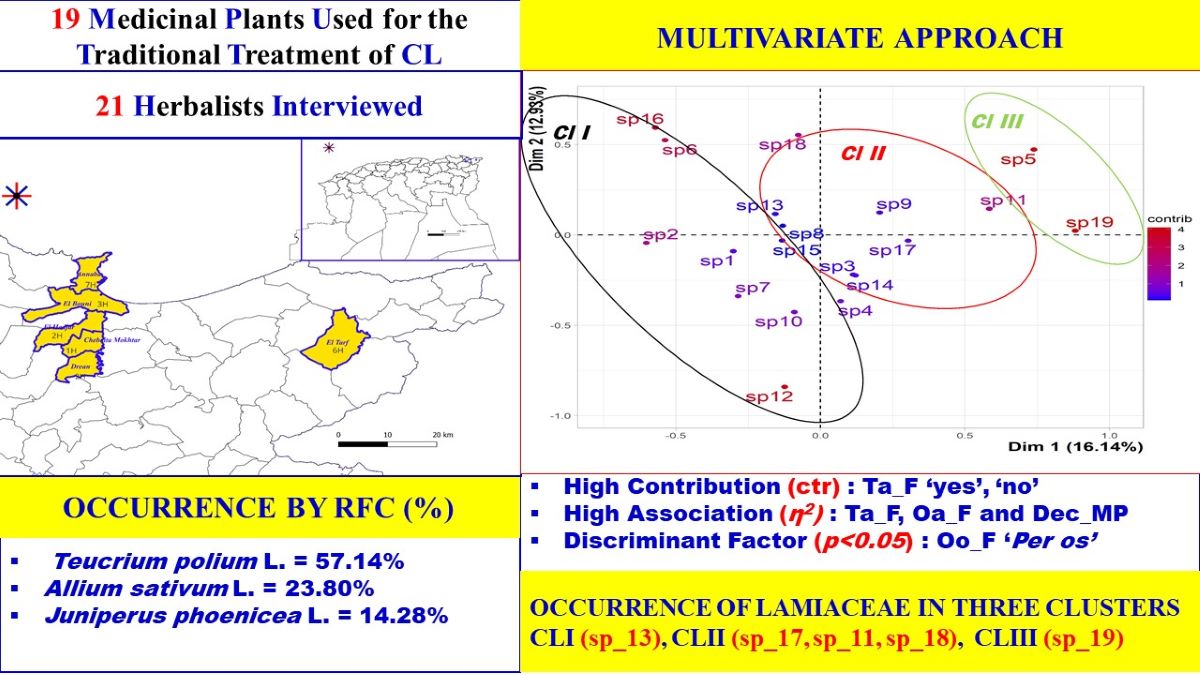

2.1. Description of the Study Sites

Interviews were held with established herbalists in two districts situated in Northeastern Algeria namely Annaba and El Tarf as shown in figure 1. The Annaba station (36°53'59'' North, 7°46'00'' East) is 533 km from Algiers (1439 Km

2 area). The El Tarf station (36°75'58'' North, 8°22'12'' East) is 589 km from Algiers (3339 Km

2 area). According to the Köppen and Geiger climate classification, the climate of the two study locations is warm and classified as «Csa» hot-summer Mediterranean climat , with average temperature values (A: 18.4°C, T: 18.3°C) and average annual rainfall values (A: 712 mm, T: 694 mm) [

45].

Figure 1.

Geographical position of districts in the study area map.H: herbalists

Figure 1.

Geographical position of districts in the study area map.H: herbalists

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Qualitative Variables

The ethnobotanical approach was based on describing the use of the traditional treatment. The questionnaire addressed traditional treatments used in the treatment of CL and included closed questions that required a 'yes' or 'no' response. As a result, the questions were semi structured [

46]. The interviews were conducted entirely in Arabic.

The questionnaire was prepared according to the model described by Chassagne et al. (2022) [

47]. Due to the absence of an ethics committee in Algeria, the ethical guidelines provided by the International Society of Ethnobiology (

http://www.ethnobiology.net/) were strictly followed [

48].

The questionnaire was focused on five aspects of use: 1) the part of the plant used, 2) the mode of preparation, 3) the form of administration, 4) the possibility of association with various natural products, and 5) the frequency of use. Each item was subdivided into qualitative variables (25 qualitative variables): 1-a: aerial part, 1-b: bark, 1-c: bulb, 1-d: flower, 1-e: fruit, 1-f: leaves, 1-g: roots, 1-h: resin, and 1-i: seeds; 2-a: decoction, 2-b: infusion, 2-c: cataplasm, 2-d: juice, 2-e: latex, 2-f: powder, and 2-g: oil; 3-a: topical administration or 3-b: oral administration; 4-a: honey, 4-b: olive oil, 4-c: cow’s milk, or 4-d: plant; 5-a: once a day, 5-b: twice a day, or 5-c: thrice a day.

2.2.2. Quantitative Variables

A supplementary quantitative variable (V26) was determined in this survey, represented by the relative frequency of citation percentage. The Relative Frequency Citation (RFC) index indicated the local importance of each plant species based on the number of citations by the informants. Based on the number of citations by informants, the Relative Frequency Citation (RFC) index determined the local relevance of each plant species [

49]. This index was calculated by making specific changes to the formula used in prior research

Where FC indicates the number of citations given by the total number of informants showing the use of each species, and N denotes the total number of informants interviewed in the study.

2.3. Authentication of Medicinal Plants

Each voucher specimen was identified by comparing it with the morphological characteristics described in the Algerian flora [

50]. The scientific name of each species was checked and asserted based on their identification in the international database the plant list [

51].

2.4. Multivariate Analysis

This research used new statistical methods to evaluate the traditional knowledge for treating CL in North East Algeria. The multivariate analyses were performed with the assistance of r software (4.2.2) [

52], an open-source programming language and

environment for statistical and graphical techniques, with the assistance of the package "FactoMineR"[

53], using the graphical interface "Factoshiny" dedicated to multivariate data analysis taking and into account the main features: different types of variables (active and supplementary elements), the structure of the data (a partition on the variables and the individuals), and a hierarchical structure on the variables [

54].

2.4.1. Structure of the Data

The variables of a multivariate matrix could be classified as multistate or binary. The 25 qualitative variables for this dataset were considered "binary variables". It is noteworthy to codify the qualitative variables data into a binary data set with the possibilities of states or modalities as: "no"="0" or "yes"="1". The resulting "descriptive" data on traditional knowledge was transformed into an analytical "statistical" table known as a "Complete Contingency Table".

2.4.2. Description of the Dimensions

Each dimension of a multivariate analysis can be described by the active variables (quantitative and/or categorial). The description of the individuals (=species) and the descriptors (=variables) is an essential step for defining the type of multivariate analysis. The multivariate matrix was used to characterize the comparison between the identified species and the correlation between the descriptors [

37].

2.4.3. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

According to the nature of the variables, the data set of this study was submitted to Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). The data frame was constructed with 19 rows and 26 columns. Rows represented objects or species, while columns represented the 25 actives qualitative variables and one supplementary quantitative variable.

The qualitative matrix was used in MCA to generate two quantitative matrices. The output matrix for «items» comprises 19 rows and 25 columns (coordinates against each of 25 axes), with columns arranged in decreasing order of explained variance from the source matrix. The «variable» output matrix has 50 rows (variable modalities) and 19 columns (coordinates against the same 25 axes).

For one qualitative variable, in the first step, a descriptive analysis was obtained from the frequency derived from the data set described in the section on data collection. Then, in the second step, the eigenvalue, the contribution, and the correlation for the main features were derived. Understanding and interpreting the data in the results section is essential to clarifying the distinctions between these parameters.

The eigenvalues in the MCA reproduce, in descending order, the highest variation of inertia among the observations; the total number of eigenvalues is determined by considering the dimension of the dataset as indicated in Equation (1):

Where

k is the number of variables included in the MCA and

n is the total number of possible values the variables may assume. This contribution indicates which variables best explain the variations in the data set and are essential in the axis' development. Conversely, the correlation reflects the relationship between two variables or the degree of impact of one variable over the other [

57]. As a result, a one-way analysis of variance was done with the coordinates of the individuals on the axis explained by the categorical variable. The student

t-test was then used to compare the category average to the overall average [

54].

2.4.4. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA)

The MCA was applied in the HCA analysis using Ward's minimum variance approach [

55]. Ward's linkage method attempts to group observations to reduce cluster variation. As a result, an observation is deemed a cluster member if its inclusion in that cluster results in a minimal increase in the error sum of squares [

56]. The distance of the

Ward’s method (

DAB) is calculated using Equation (2):

Where A and B represent the set of clusters, NA and NB are the number of observations in clusters A and B, respectively; and demonstrate the mean vectors representing clusters A and B and shows the squared Euclidean distance between the vectors and Cluster analysis was used to i) characterize the partition of classes or groups of species used in traditional cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment (in terms of quantitative variables) and ii) characterize the parameters that best describe the partition using the Chi2 test (by increasing the p-value) between the qualitative variable and the class variable. Based on their ethnopharmacological applications in CL, our research produced a dendrogram representing the number of species in each class.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Features of Informants

A total of 21 herbalists were interviewed, with 57.10% belonging to Annaba and 42.90% from El Tarf provinces. The average age of all participants was 53.4 ±16.7 years old, ranging from 20 to 60 years old. The vast majority of participants (95.2%) were men. A substantial percentage of participants (76.20%) stated that their professional experience had made them the most informed in traditional medicine (

Table 1).

3.2. Distribution of Medicinal Plants According To The Relative Frequency Index

Table 2 shows the descriptive analysis of ethnobotanical data collected from interviews with herbalists in the Annaba and El Tarf districts. Herbalists recommended 19 therapeutic herbs from 13 plant families, where the Lamiaceae was the most abundant species (five), followed by the Amaryllidaceae (two species) and the Asteraceae (two species).

The species were ranked according to their frequency of citations, and the top two species were Teucrium polium L. (57.14%), followed by Allium sativum L. (23.80%). Other significant species also cited were Juniperus phoenicea L. (14.28%) and Rosmarinus officinalis L. (9.52%). The results also showed that 14 medicinal plants [sp1: bulb, sp3: leaves, sp4: leaves, sp5: bark, sp6: fruit, sp7: resin, sp8: fruit, sp10: stem, sp12 seeds, sp13: aerial part, sp14: leaves, sp15: leaves, sp16: aerial part, and sp19: leaves] demonstrated a similar value in the frequency index (4.76%). The most represented parts were bark, flower, root, resin, and stem, with a similar frequency of occurrence estimated as 18.

3.3. Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA)

Regarding the descriptive results and the frequency of responses connected to CL traditional knowledge in Northeastern Algeria, all qualitative variables were chosen for MCA analysis. Three parameters were identified using this method: the eigenvalue (p), the contribution (ctr), and the square ratio correlation (η2).

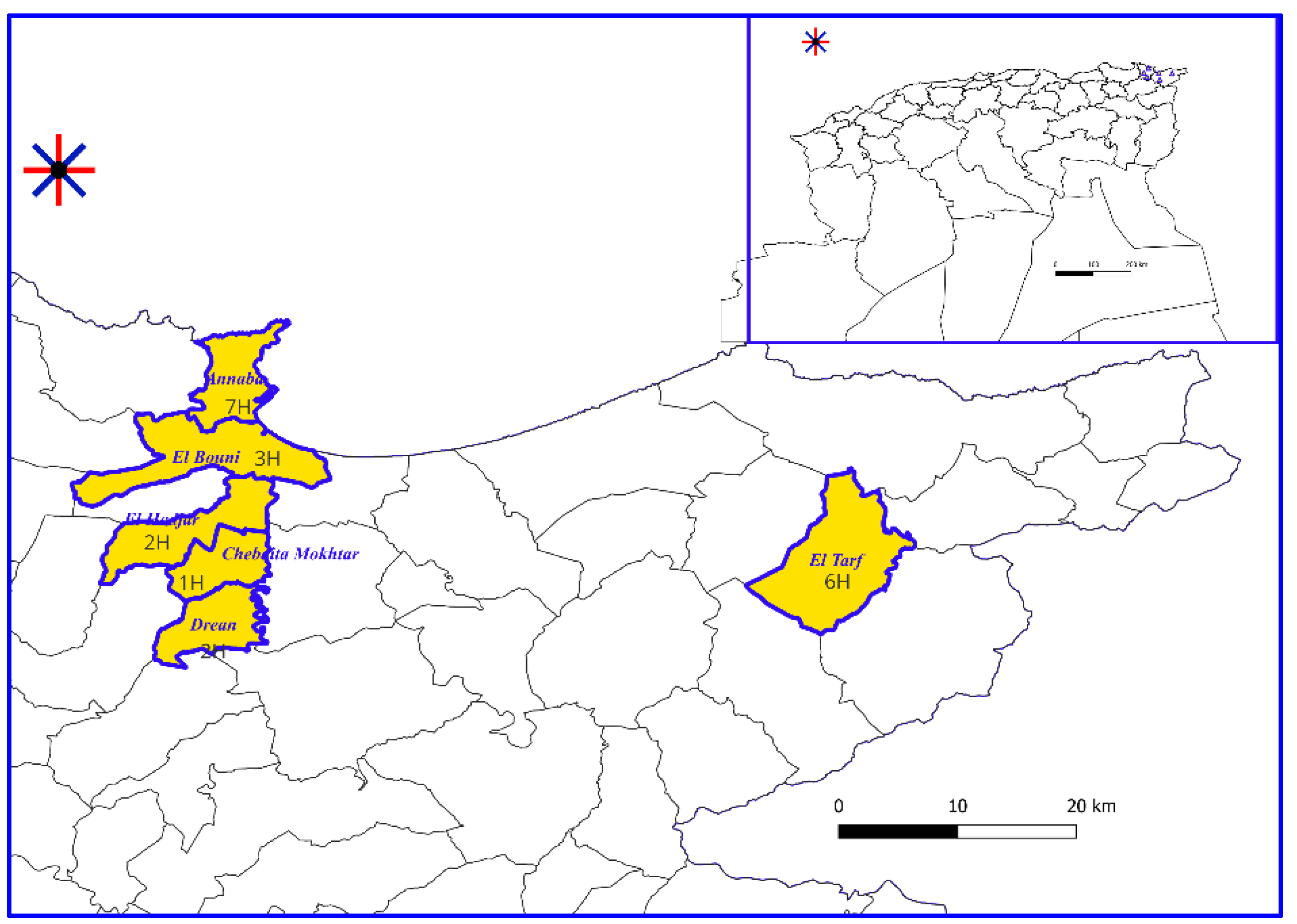

3.3.1. Inertia Distribution and Eigenvalues

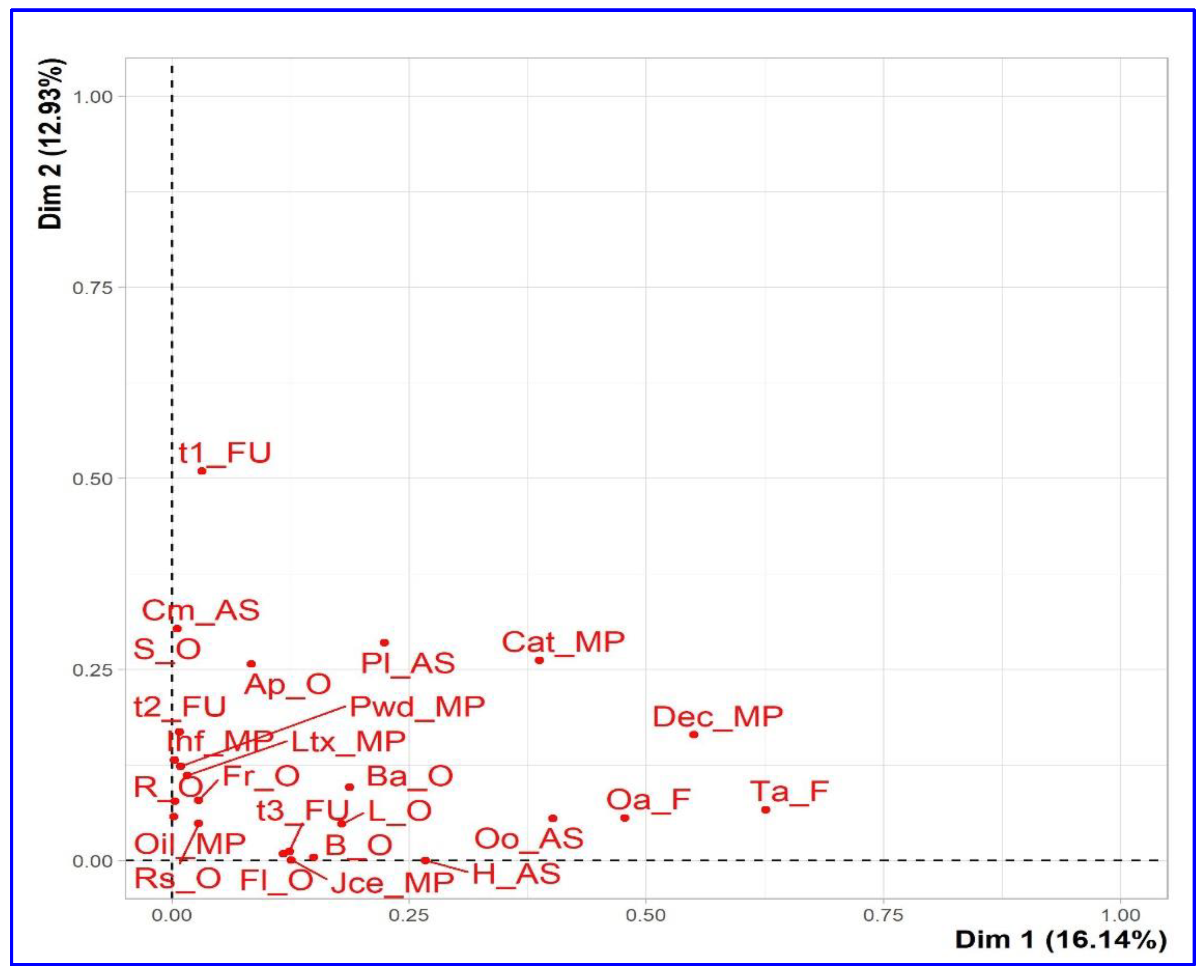

The variance for the first dimension (x-axis) was recorded to be 16.139% (p=0.155), while the second dimension (y-axis) was 12.926% (p=0.124). The inertia (sum of variances) for these two first dimensions was 29.07% of the whole dataset inertia; that means that 29.07% of the individuals (or variables) cloud total variability is explained by the plane (

Figure 2).

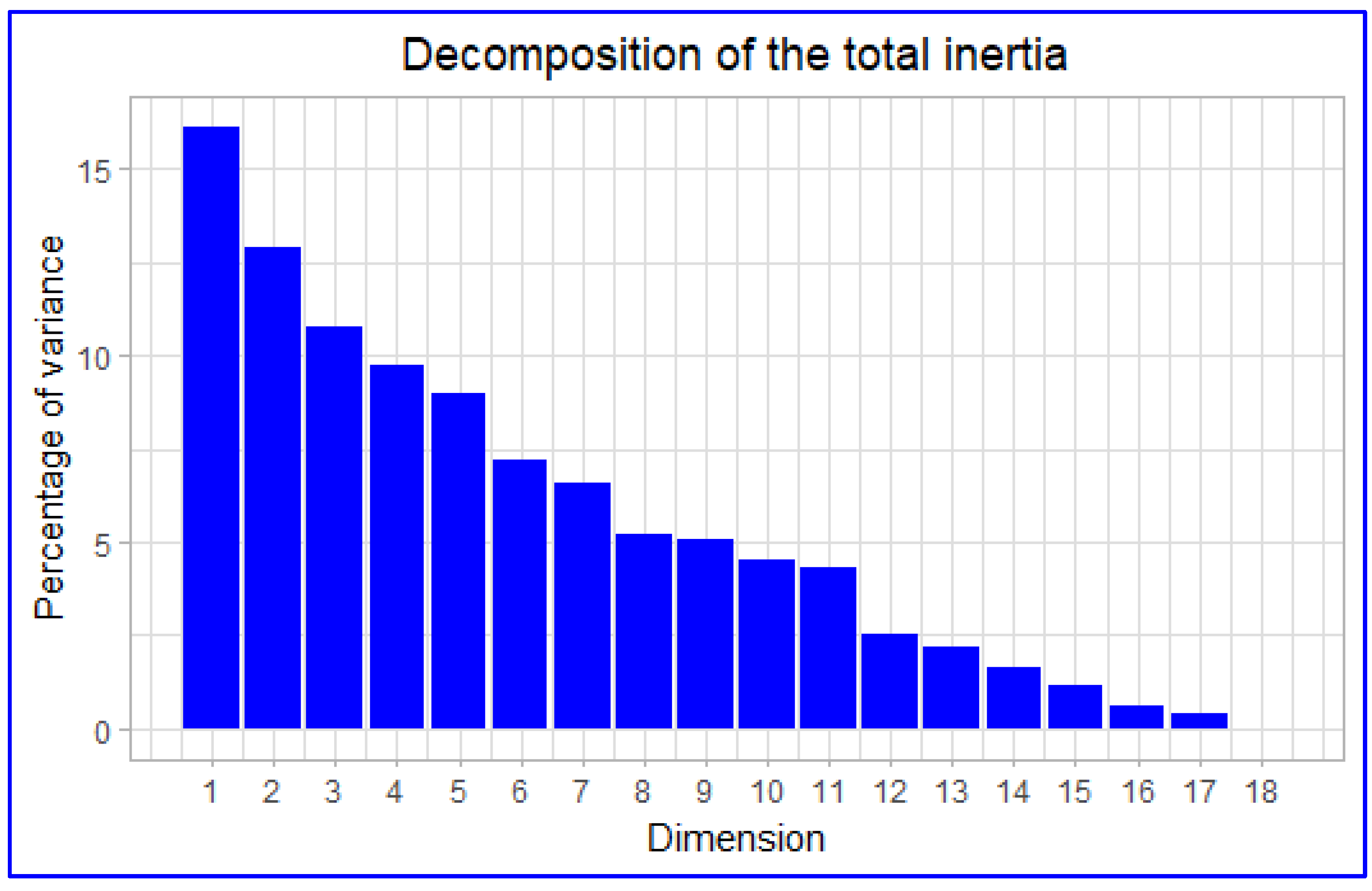

3.3.2. Distribution of species within variables

The graphical representation of the contribution of the individual species on the first two axes is shown in the

Figure 3. This presentation analyzes the states of the first descriptor compared to the states of the second descriptor. The visualization of the results was carried out with a scatter diagram. The variability or similarity of species identified in the study was described according to the descriptors used.

The first dimension opposes species characterized by a higher contribution value with positive coordinates on the axis-x [sp5: ctr=17.738, x=0.723, sp11: ctr=11.128, x=0.573, sp19: ctr=25.292, x=0.864] to species with negative coordinate values on the axis-x [sp 2: ctr=11.869, x=-0.592, sp6: ctr= 9.425, x=-0.527, sp16: ctr= 10.633, x=-0.560). Concerning the first dimension, the second axis opposes similarities with a strongly positive coordinate on the axis-y [sp16: ctr=14.363, y=0.582, sp6: ctr= 11.221, y=0.515, and sp18: ctr=12.497, y= 0.543] to species [sp12, sp10 and sp7] characterized by a negative coordinate value [ctr=28.727/y=-0.824, ctr=7.376/y=-0.417, ctr=4.635/ y=-0,331].

Legend of species (sp) factor map: The labeled individuals (species in red) are those with the higher contribution to the plane construction.

Species legends: sp1, Allium cepa L.; sp2, Allium sativum L.; sp3, Aloe vera L.; sp4, Artemisia herba alba Asso.; sp5, Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume; sp6, Citrullus colocynthis (L.) Schrad.; sp7, Commiphora myrrha (T. Nees) Engl.; sp8, Ficus carica L.; sp9, Juniperus phoenicea L.; sp10, Launaea arborescens (Batt.) Murb.; sp11, Lavandula angustifolia Mill.; sp12, Lepidium sativum L.; sp13, Marrubium vulgare L.; sp14, Nerium oleander L.; sp15, Olea europaea L.; sp16, Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb; sp17, Rosmarinus officinalis L.; sp18, Teucrium polium L.; sp19, Thymus vulgaris L.

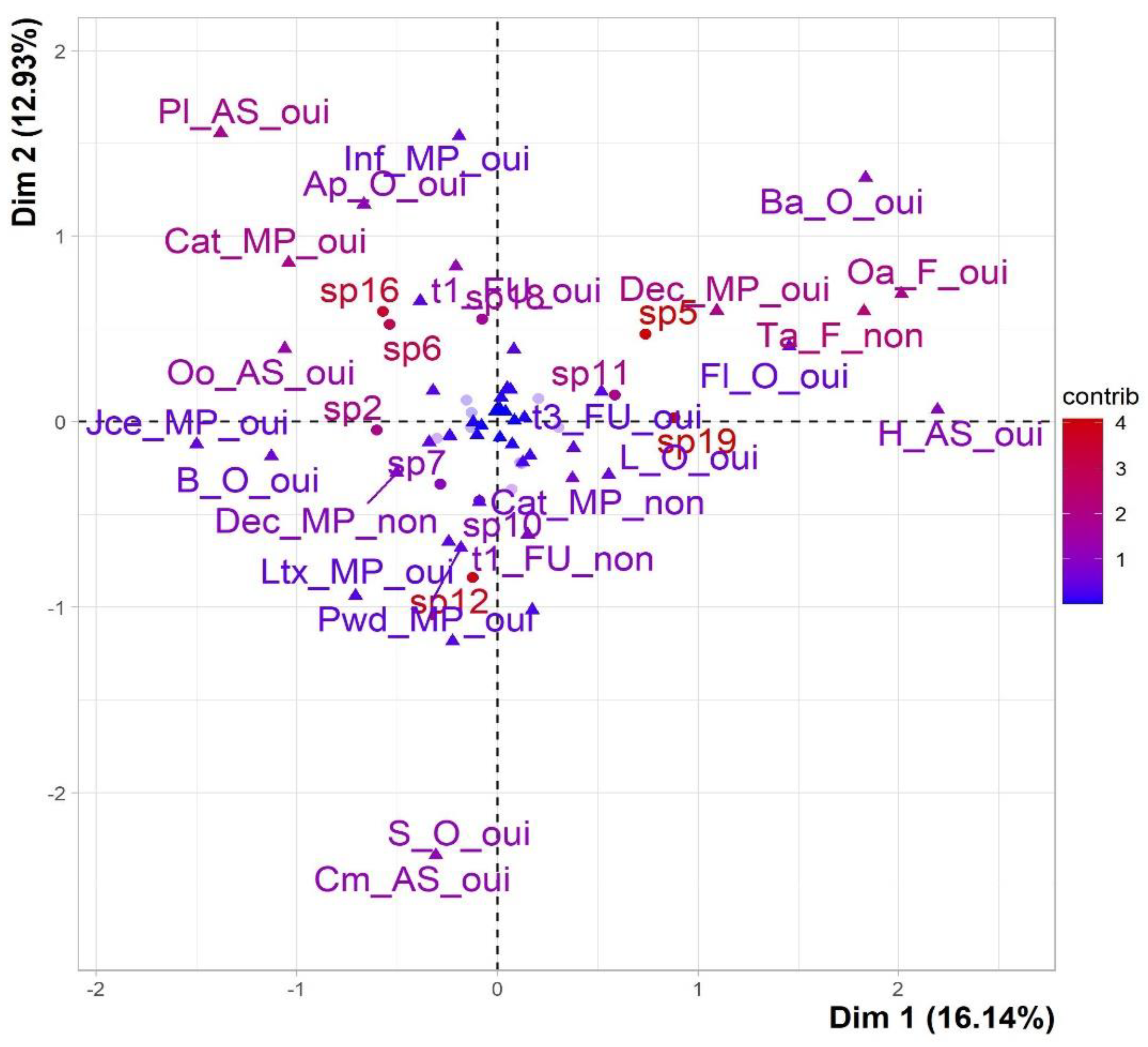

To facilitate the interpretation of the cloud of species, a graphical depiction of variables was employed (

Figure 4). In this presentation, each variable coordinates the square correlation ratios (denoted as η

2) between the variable and the coordinates of the individuals on the first and second axes, respectively.

In this way, the first dimension showed a higher correlation with the Ta_F variable, with the square correlation ratio (η2) estimated as 0.626 (p<0.05). This correlation with the first dimension was followed by two variables, Oa_F and Dec_MP, with values of η2: 0.550 and 0.477 (p<0.05). In parallel, the frequency of use (t1_FU) showed a higher correlation with the second dimension, with the η2 value estimated as 0.509.

Dim: Dimension

The data offered by the variables is broad and, hence, inadequate for interpreting the similarities and differences among the species. Consequently, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive examination utilizing the classifications of those variables. A common method for visually depicting a category on a graph of persons is to place the category at the barycenter, which refers to the average location of the individuals who possess it in their response. Two categories exhibit proximity when the species that comprise them demonstrate a tight relationship, indicating that their general reactions to the variables are comparable [

57]. The proximity between two categories is interpreted as proximity between two groups of species (

Figure 5).

Here, for example, the categories Ta_F_no, Oa_F_yes, and Dec_MP_yes are superimposed as they are chosen by the same species [sp5, sp19, and sp11, sp9, sp17]. Moreover, the modalities Cat_MP_yes, Pl_AS_yes and Oo_AS_yes were closely associated with species [sp16, sp6, sp2, and sp18].

Table 3 shows the main features and their correlation ratios on the two first dimensions (1 and 2).

Here, it represents the ratio of the between-categories variability over the total variability.

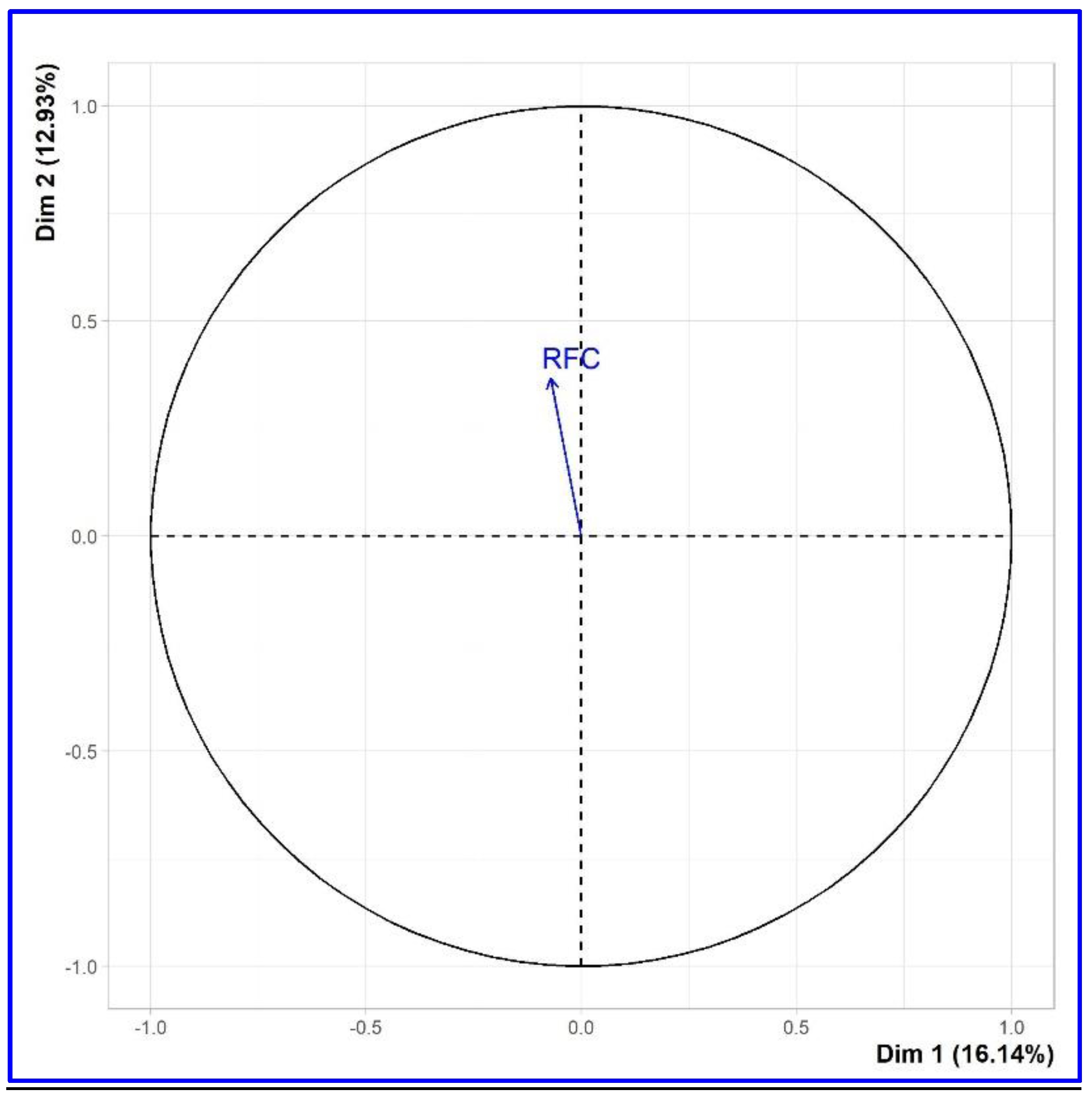

The quantitative variable of RFC is projected as a supplementary feature. Therefore, the graph is constructed as the graph of correlation in PCA. This method was detailed and reported by [

57]. The correlation of the variable on dimension

k corresponds to the correlation coefficient between the principal component

k and the variable.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the correlation coefficient between the second principal component and the frequency of the RFC index is 0.367.

3.4. Cluster Analysis

3.4.1. Cluster Characterization

The chi-square test was performed between the categorical variable and the cluster variable, and the

p-value was less than 0.05, showing that the categorical variable is linked to the cluster variable [

58]. Indeed, the most characteristic variables affecting the partition of the clusters were

Oa_F,

t3_FU,

Dec_ MP, and

Ta_F with respective

p-values 7.48E-05, 5.44E-04, 3.95E-03, and 1.87E-03 (

p-values

<0.05).

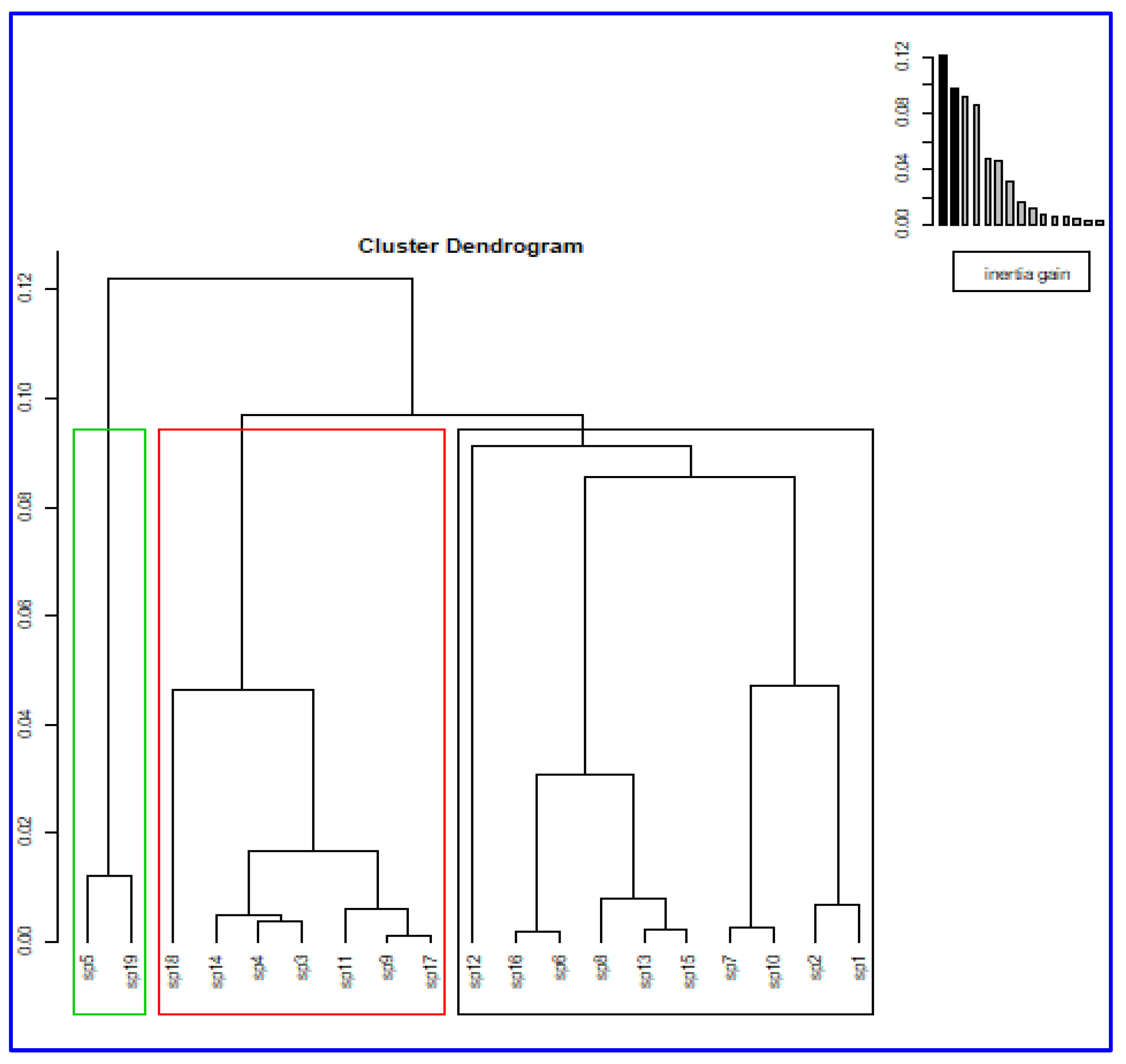

The dendrogram suggests the existence of three clusters (

Figure 7). Cluster 1 includes ten species, sp1, sp2, sp10, sp7, sp15, sp13, sp8, sp6, sp16, and sp12, while cluster 2 contains seven species, sp17, sp9, sp11, sp3, sp4, sp14, and sp18. In addition, cluster 3 includes the two species, sp5 and sp19.

3.4.2. Link between the cluster variable and the categorical variables

Determining the characteristic variables for the partition is measured by the difference between the values of the model of the nominal variable related to the cluster and the overall values. The modality is considered characteristic if its abundance in the cluster is significantly higher than expected, given its presence in the population. This is measured by a criterion known as the

test value [

59]. The test value is a criterion to assess a significant position of a modality or a category of the variable. The significant position is considered when the test value is greater than 2 in absolute value, corresponding to approximately the 5% threshold [

60].

Table 4 defines the category of variables most related to the cluster variable with the test value.

Considering the partition of the categorical variable for each cluster, cluster 1 is characterized by two modalities, including the mode of preparation via decoction [Dec_MP_no] and the frequency of use [t3_FU_no]. More species are not used by decoction and a frequency of thrice per day in this cluster than in others. Indeed, 76.92% of species related to t3_FU_no/Dec_MP_no belong to cluster 1, and 100% of species in cluster 1 are cited with t3_FU_no/Dec_MP_no considered as significant modalities with similar test values estimated as 2.95. In contrast, 100% of species used with a frequency of use t3_FU_yes belong to cluster 2 (v.test=3.65). Then, the modality Oa_F_yes was significant and characterized 100% of the species for cluster 3 with the test value estimated as 2.75.

The analysis of the clustering partition and the phylogenetic relationship demonstrates the disorders of the distribution of the botanical family coupled with the traditional use of the antileishmanial species. This is justified by the occurrence of the Lamiaceae family in the three clusters: cluster 1 (sp_13_Marrubium vulgare L.), cluster 2 (sp_17_Rosmarinus officinalis L., sp_11_Lavandula angustifolia Mill., and sp_18_Teucrium polium L.), and for cluster 3 (sp_19_Thymus vulgaris L.).

However, the partition of the species belonging to the Asteraceae family is noticeable for the two clusters 1 (sp10_

Launaea arborescens (Batt.) Murb) and 2 (sp4_

Artemisia herba alba Asso). The applicability of the cluster analysis to the study of plant taxonomy in the context of ethnopharmacology was performed by Leduc et al., 2006, who reported the limitations of the classification within phylogenetic relationships [

40].

4. Discussion

Considering the ethnobotanical research carried out in North Africa, it was found that 42% of species were not previously reported for the traditional treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Among them, three species were reported for the first time: Retama raetam (Forssk.) Webb, Ficus carica L. and Launaea arborescens (Batt.) Murb.

Moreover, the ethnopharmacological investigation in the Ain Sekhouna region, located in the elevated regions of western Algeria, revealed the presence of three plant species that are utilized for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). These species include

Haloxylon scoparium Pomel (Chenopodiaceae, 73%),

Artemisia herba-alba Asso. (Asteraceae, 18%), and

Camellia sinensis L. (Theaceae, 9%). These plants are administered primarily in the form of powdered extracts, either alone or in combination with substances such as butter, honey, olive oil, or cade oil, often applied as a poultice [

30].

Sixty-one plants were cited by 272 herbalists and traditional healers for the treatment of CL in the Tafilalet oasis situated in the Errachidia district of Morocco. Thus, 96% of responses described that the external form is the most administered as the cataplasm, liniment, poultice, ointment, local rinsing, and powdered forms [

61].

Subsequently, the diversity of leishmanicidal plants was investigated in the center of Morocco (Sefrou City). This ethnopharmacological survey included 16 herbalists and reported 16 species known for their potential to cure cutaneous lesions [

62]. The most species cited by herbalists from Sefrou city and ranked by the percentage of the frequency index (FI %) were

Lavandula dentata L. (FI = 93.75%),

Cistus salviifolius L. (FI = 87.5%),

Berberis hispanica Boiss. & Reut. (FI = 87.5%),

Crataegus oxyacantha L. (FI = 81.25%),

Ephedra altissima Desf. (FI = 75%), and

Rosmarinus officinalis L. (FI = 62.5%).

The results of this bibliographic data analysis do not agree with our study, which highlighted the ranking of species cited by the herbalists from the Annaba and El Tarf districts based on the relative frequency index value. Thus, the most important species identified were Teucrium polium L., Allium sativum L., Juniperus phoenicea L., Lavandula angustifolia L. and Rosmarinus officinalis L.

The antileshmanial effect of these species has not been reported previously in Algeria.

Table 5 reports their ethnopharmacological data and the scientific name of species, the origin of the plant, the part used, the form of parasitic strain tested, and the results of the concentration of drug that causes 50% growth inhibition of amastigotes and promastigotes forms of Leishmania.

Moreover, Eddaikra et al. (2019) reported on the antileishmanial activity of seven Algerian species [

Erica arborea L.

, Ajuga iva (L.) Schreb.,

Ballota hirsuta Benth.,

Artemisia herba alba Asso,

Marrubium vulgare L.,

Marrubium supinum L.

, and

Marrubium deserti (Noë) Coss.] against promastigotes and amastigotes of

Leishmania major (MON 25) and

Leishmania infantum (MON 1) [

29].

E. arborea,

M. vulgare, and

A. herba alba were the most efficient species on the growth inhibition of

L. major promastigotes form with respective values of IC

50: 43.98, 45.84, and 55.21 μg/mL.

M. vulgare leaves were the most effective against

L. infantum promastigotes, with an IC

50 value of 35.63 μg/mL [

29]. Three references were used as the positive control [Amphotericin B, Potassium antimony tartrate (SbIII), and Gluconate antimoniate of meglumine (Glucantime

®)], the concentration of the inhibition of 50% growth (IC50) for parasitic strains

L. major and

L. infantum were evaluated. The highest activity was observed for Amphotericin B, with a similar value of IC50 for

L. infantum and

L. major estimated as 0.2 μg/mL. At the same time, SbIII was active on

L. major and

L.infantum promastigotes with IC50s of 3.59±0.56 μg/ml and 1.34±0.56 μg/ml, respectively. However, Glucantime® was less active against

L. major and

L. infantum amastigotes with IC50s of 20.44±1.02 μg/ml and 13.78±1.07 μg/ml, respectively.

A significant contribution was performed by Passero et al. (2021) who analyzed 294 articles and reported several criteria regarding the plants recommended for the treatment of leishmaniasis by traditional communities worldwide, namely species, vernacular name, botanical family, recipes, parts of the plants used, the method of preparation, and the route of administration [

7].

From 20 articles, 378 citations referring to 292 plants indicated by several traditional communities around the world to treat leishmaniasis, the most frequent families used by traditional communities were Fabaceae (27 species), Araceae (23 species), and 22 each for the Asteraceae and Solanaceae. This classification was followed by the Euphorbiaceae (21 species) and Rubiaceae (20 species). Among the available data in the 378 citations, the most suitable route of administration for plants was the topical route at 74.6%, followed by the oral route and inhalation or nasal route (5%,

v.s 1.3%). Notably, no specified route of administration was indicated at 20.6% [

7].

Another review by Bahmani et al. (2015) highlighted the phytotherapy of cutaneous leishmaniasis in traditional Iranian medicine. Thirty medicinal plants were reported, with their effects supported

in vitro by inhibiting the parasitic agent. The effective concentration of extracts against promastigotes of

L. major was also detailed. According to these data, the most critical family with the best effect on leishmania is the Asteraceae, including the two genera

Artemisia and

Tagetes [

76].

5. Conclusions

This section is not mandatory but can be added to the manuscript if the discussion is unusually long or complex.

This is the first study to employ a quantitative ethnobotanical technique to investigate the traditional usage of antileshmanial medicinal plants from Northeastern Algeria. Even though this survey reported 19 species ranked according to their relative frequency index, practically all species cited had not been described in prior studies on Algerian antileishmanial plants. For the first time, three species are documented for their traditional use in treating CL.

The MCA multivariate tests and cluster analysis revealed that the traditional usage of antileshmanial species is distinguished by two factors: the mode of administration and the mode of preparation. In this case, Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume and Thymus vulgaris L. are described for the first time for treating CL using per os as the mode of administration.

Once the active principles have been determined, a more diverse in vitro study on sustainable, standardized preparations of the most promising plants is required to identify a dosage schedule. Selected clinical research studies on standardized materials may be conducted to determine their safety and efficacy against certain strains of leishmaniasis.

Finally, the partition clustering analysis requires more phylogenetic links and ethnobotany classes. These constraints highlight the need to identify the exact metabolite profile and biological activity to establish a global matrix for a potential candidate plant.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, A.B., M.L.A. and G.A.C.; formal analysis, A.B. and L.B.; investigation, A.G. and A.G.; resources, A.B. and L.B.; data curation, A.B., A.G. and A.G..; writing—original draft preparation, A.B., M.L.A. and G.A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.B., M.L.A. and G.A.C.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, A.B. and G.A.C.; project administration, A.B., A.G. and A.G.; funding acquisition, M.L.A. and E.R.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

“This research was funded by Northern Border University, grant number NBU-FFR-2024-249-XX”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable”

Data Availability Statement

All data collected and used in this work are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable written request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

MCA: Multiple Correspondence Analysis, HCA: Hierarchical Clustering Analysis, RFC: Relative Frequency Citation, CL: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis, VL: Visceral Leishmaniasis, MCL: Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis, Csa: hot-summer Mediterranean climat, p: eigenvalue, ctr: contribution, η2: square ratio correlation, ANOVA: Analysis of Variance, PCA: Principal Component Analysis, v. test: test value, FI: Frequency Index, IC50: Half maximal inhibitory concentration.

References

- Achour, N.; Barchiche, N. A.; Madiou, M. Recrudescence des leishmanioses cutanées: a propos de 213 cas dans la wilaya de Tizi-Ouzou. Pathol. Biol. 2009, 57, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimaldi, G.; Tesh, R.B. Leishmaniases of the New World: current concepts and implications for future research. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1993, 6, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soosaraei, M.; Fakhar, M. , Teshnizi, S.H.; Hezarjaribi H. Z.; Banimostafavi, E. S. Medicinal plants with promising antileshmanial activity in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicinal plants with promising antileishmanial activity in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Med. Surg. 2017; 21, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, H.J.C.; Schallig, H.D. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A 2022 Updated Narrative Review into Diagnosis and Management Developments. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 823–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvar, J.; Vélez, I.D.; Bern, C.; Herrero, M.; Desjeux, P.; Cano, J.; et al. WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidences. PLoS One. 2012, 7:e35671. [CrossRef]

- Benikhlef, R.; Aoun, K.; Boudrissa, A.; Ben Abid, M.; Cherif, K.; Aissi, W.; Benrekta, S.; Boubidi, S.C.; Späth, G.F.; Bouratbine, A.; Sereno, D.; Harrat, Z. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Algeria; highlight on the focus of M’Sila. Microorganisms. 2021, 9, 962–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passero, L.F.D.; Brunelli, E.D.S.; Sauini, T. ; Amorim Pavani,T.F.; Jesus, J.A.; Rodrigues, E. The Potential of Traditional Knowledge to Develop Effective Medicines for the Treatment of Leishmaniasis. Front Pharmacol. 2021; 8, 690432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, GA. Ecopharmacognosy – the responsibilities of natural product research to sustainability. Phytochem. Lett. 2015, 11, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, S.K.; Cordell, G.A. Alkaloids in contemporary drug discovery to meet global disease needs. Mol. 2021, 26, 3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammiche, V. ; Maiza, K Traditional medicine in Central Sahara Pharmacopoeia of Tassili N’ajjer. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 105, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allali, H.; Benmehdi, H.; Dib, M.A.; Tabti, B.; Chalem, S. , Benabadji, N. Phytotherapy of Diabetes in west Algeria. Asian Journal of Chemistry. 2008, 20, 2701–2710. [Google Scholar]

- Azzi, R.; Djaziri, R.; Latifa, F. , Sekkal, F. Z.; Benmehdi, H., Belkacem, N. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus in the north western and south western Algeria. J. Med. Plant Res. 2012, 6, 2041–2050. [Google Scholar]

- Boudjelal, A. , Henchiri, C.; Sari, M., Sarri, D., Hendel, N.; Benkhaled, A., Ruberto, G. Herbalists and wild medicinal plants in M’sila (North Algeria): An ethnopharmacology survey. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013; 148, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Bouzabata, A. Traditional treatment of high blood pressure and diabetes in Souk Ahras District. J. Pharmacognosy Phytother. 2013, 5, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sarri, M. , Mouyet, F.Z., Benziane, M., Cheriet A. Traditional use of medicinal plants in a city at steppic character (M’sila, Algeria). J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2014; 2, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Benarba, B.; Belabid, L.; Righi, K.; Bekkar, A.A.; Elouissi, M.; Khaldi, A.; Hamimed, A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Mascara (North West of Algeria). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 175, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chermat, S.; Gharzouli, R. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal flora in the North-East of Algeria-An empirical knowledge in Djebel Zdimm (Setif). J. Mat. Sci. Eng. A. 2015; 5, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Meddour, R.; Meddour Sahar, O. Medicinal plants and their traditional uses in Kabylia (Tizi Ouzou, Algeria). AJMAP. 2015, 137–151. [Google Scholar]

- Ramdane, F.; Mahammed, M.H.; OuldHadj, M.D.; Chanai, A.; Hammoud, R.; Hillal, N.; Mesrouk, H.; Bouafia, I.; Bahaz, C. ; Ethnobotanical study of some medicinal plants from Hoggar, Algeria. J. Med. Plant Res. 2015, 9, 820–827. [Google Scholar]

- Sarri, M.; Boudjelal, A.; Hendel, N.; Sarri, D. Benkhaled A. Flora and ethnobotany of medicinal plants in the southeast of the capital Hodna (Algeria). AJMAP. 2015; 1, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baghdad, M.; Boumdiene, M. ; Djamel, A; Djilali B. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in the region Beni Chougrane (Mascara, Algeria). J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 2016; 9, 426–433. [Google Scholar]

- Benarba, B. Medicinal Plants used by traditional healers from South-west Algeria: An ethnobotanical study. J. Intercult. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 5, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telli, A.; Esnault, M.A.; Ould El Hadj Khelil, A. An ethnopharmacological survey of plants used in traditional diabetes treatment in south-eastern Algeria. J. Arid Environ 2016, 127, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouasla, A.; Bousla, I. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in northeastern of Algeria. Phytomedicine. 2017, 36, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzabata, A. Biodivesity, Traditional Medicine and Diabetes in Northeastern Algeria. In: Recent Advances in Environmental Science from the Euro-Mediterranean and Surrounding Regions, Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation; Ksibi M et al., Eds.; Proceeding of Euro-Mediterranean Conference for Environmental Integration (EMCEI-1), Tunisia: Springer International Publishing AG: Germany; 2018; pp. 1219–1221.

- Hamza, N.; Berke, B.; Umar, A.; Cheze, C.; Gin, H.; Moore, N. A review of Algerian medicinal plants used in the treatment of diabetes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 238, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzabata, A.; Mahomoodally, M.F.A. quantitative documentation of traditionally used medicinal plants from Northeastern Algeria: Interaction of beliefs among healers and diabetic patients. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, I. Etude in vitro de l’activité anti leishmanienne de certaines plantes médicinales locales: cas de la famille des lamiacées. Thèse en vue de l’obtention du diplôme de Magister en Biologie Appliquée. Université de Constantine 1 Faculté des sciences de la nature et de la vie, 2013. http://www.secheresse.info/spip.php?article80271.

- Eddaikra, N.; Boudjelal, A.; Sbadji, M.A.; Eddaikra, A.; Boudrissa, A.; Bouhenna, M.M.; et al. Leishmanicidal and Cytotoxic Activity of Algerian Medicinal Plants on Leishmania major and Leishmania infantum. J Med Microbiol Infect Dis 2019, 7, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, A.; Hachem, K.; Hassani, M.M. Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal plants used to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ain Sekhouna, Saida, Algeria. Not. Sci.Biol. 2021, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Et-Touys, A.; Fellah, H.; Mniouil, M.; Bouyahya, A.; Dakka, N. ; Abdennebi E H, et al. Screening of antioxidant, antibacterial and antileishmanial activities of Salvia officinalis L. extracts from Morocco. Br. Microbiol. Res. 2016; 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Et-Touys, A. , Fellah, H., Sebti, F., Mniouil, M., Aneb, M., Elboury, H et al. In vitro antileishmanial activity of extracts from endemic Moroccan medicinal plant Salvia verbenaca (L.) Briq. ssp. verbenaca Maire (S. clandestina Batt. non L). Euro. J. Med. Plants. 2016; 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Essid, R; Rahali, F.Z.; Msaada, K.; Sghair, I.; Hammami, M.; Bouratbine, A.; Limam F. Antileishmanial and cytotoxic potential of essential oils from medicinal plants in Northern Tunisia. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015; 77, 795–802.

- Bouyahya, A.; Bakri, Y. , Belmehdi, O.; Et-Touys, A.; Abrini, J.; Dakka N. Phenolic extracts of Centaurium erythraea with novel antiradical, antibacterial and antileishmanial activities. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2017; 7, 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyahya, A.; Et-Touys, A.; Bakri, Y.; Talbaui, A.; Fellah, H.; Abrini, J.; Dakka, N. Chemical composition of Mentha pulegium and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils and their antileishmanial, antibacterial and antioxidant activities. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 111, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouyahya, A.; Et-Touys, A.; Dakka, N. , Fellah, H.; Abrini, J.; Bakri, Y. Antileishmanial potential of medicinal plant extracts from the North-West of Morocco. Beni-Suef University J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 50–54. 7,. [CrossRef]

- Baldauf, C.; dos Santos, N.D. The use of multivariate tools in studies of traditional ecological knowledge and management systems; In: Methods and Techniques in Ethnobiology and, Ethnoecology, Albuquerque, UP., Eds.; New York: Springer Protocols Handbooks, 2019; pp. 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- Houël, E.; Ginouves, M.; Azas, N.; Bourreau, E.; Eparvier, V. Hutter, S. et al. Treating leishmaniasis in Amazonia, part 2: Multi-target evaluation of widely used plants to understand medicinal pratices. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 289, 115054.

- Höft, M. , Barik, S., Lykke, A. Quantitative ethnobotany—applications of multivariate and statistical analyses in ethnobotany.

- People and Plants Working Paper. 1999, 6, 1–49.

- Leduc, C.; Coonishish, J.; Haddad, P.; Cuerrier, A. Plants used by the Cree Nation of Eeyou Istchee (Quebec, Canada) for the treatment of diabetes: a novel approach in quantitative ethnobotany. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006; 105, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Inocencio, C.; Heinrich, M.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J.; Palazón, J.A. Gathered food plants in the mountains of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain): ethnobotany and multivariate analysis. Econ. Bot. 2007, 61, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective; Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education Prentice Hall; 2009.

- Obón, C.; Rivera, D.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J.; Valdés, A.; Alcaraz, F.; Carvalho, A.M. Árnica: a multivariate analysis of the botany and ethnopharmacology of a medicinal plant complex in the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 144, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.; Rapinski, M.; Spoor, D.; Eid, H.; Saleem, A.; Arnason, J.T.; et al. A multivariate approach to ethnopharmacology: Antidiabetic plants of Eeyou Istchee. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLIMATE-DATA: Les données climatiques pour les villes du monde entire. https://fr.climate-data.org/ (2022). Accessed 9 july 2023.

- Alexiades, M.N. Collecting ethnobotanical data: an introduction to basic concepts and techniques. In: Alexiades M N, Sheldon J W, editors, Selected Guidelines for Ethnobotanical Research: A Field Manual. Advances in Economic Botany. New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY, USA; 1996. p. 53–94.

- Chassagne, F.; Butaud, J.F.; Torrente, F.; Conte, E.; Ho, R.; Raharivelomanana, P. Polynesian medicine used to treat diarrhea and ciguatera: An ethnobotanical survey in six islands from French Polynesia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 292, 115186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International society of ethnobiology. 1988-2024. http://www.ethnobiology.net/. Accessed 9 july 2023.

- Vitalini, S. , Iriti, M., Purice Falli, C., Ciuchi, D., Segale, A., Fico, G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sandrio, Italy) - an alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–19. 145.

- Quezel, P.; Santa, S. Nouvelle flore de l’Algérie et des régions désertiques méridionales. Paris: CNRS; 1962-1963.

- The Plant List. Version 1. 2010. http://www.theplantlist.org. Accessed. 9 July 2023.

- Core Team, R: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2022). Accessed 9 july 2023.

- Husson, F.; Josse, J.; Le, S.; Mazet, J. FactoMineR: Factor Analysis and Data Mining with R. R package version 1.04. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=FactoMineR (2007). Accessed 9 july 2023.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.H. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaei, M.; Cliff, M.A.; Singh, A. Multiple Correspondence and Hierarchical Cluster Analyses for the Profiling of Fresh Apple Customers Using Data from Two Marketplaces. Foods 2020, 9, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husson, F.; Josse, J. Multiple Correspondence Analysis. In: The visualization and verbalization of data, Balsius, J., Greenacre, M., Eds. CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2015; pp. 163–181.

- Husson, F.; Josse, J.; Pagès, J. Principal component methods - hierarchical clustering -partitional clustering: why would we need to choose for visualizing data? Technical Report- Agrocampus 2010.

- Morineau, A. Note sur la caractérisation statistique d’une classe et les valeurs tests. Bulletin Technique Centre Statististique Informatique Appliquées. 1984, 2, 20–27.

- Lebart, L. , Morineau, A., Piron, M. Statistique exploratoire multidimensionnelle. Paris: Dunod; 1995.

- El Rhaffari, L. , Hammani, K., Benlyas, M., Zaid, A. Traitement de la leishmaniose cutanée par la phytotherapie au Tafilalet. BES. 2002, 1, 10, 45–54.

- Zeouk, I.; El Ouali Lalami, A.; Ezzoubi, Y.; Derraz, K.; Balouiri, M.; Bekhti, K. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: medicinal plants used in Sefrou City (Center of Morocco), a focus of leishmaniasis. Phytotherapie. 2020, 18(3-4), 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Essid, R.; Rahali, F.Z.; Msaada, K.; Sghair, I.; Hammami, M.; Bouratbine, A.; Limam, F. Antileishmanial and cytotoxic potential of essential oils from medicinal plants in Northern Tunisia. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 77, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademvatan, S.; Saki, J.; Gharavi, M.J.; Rahim, F. Allium sativum extract induces apoptosis in Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ ER) promastigotes. J. Med. Plant Res. 2011, 5, 3725–3732. [Google Scholar]

- Gharavi, M.; Nobakht, M.; Khademvatan, S.H.; Bandani, E.; Bakhshayesh, M.; Roozbehani, M. The effect of garlic extract on expression of IFN-g and iNOS genes in macrophages infected with Leishmania major. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2011, 6, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gharavi, M.; Nobakht, M.; Khademvatan, S.; Fani, F.; Bakhshayesh, M.; Roozbehani, M. The effect of aqueous garlic extract on interleukin-12 and 10 levels in Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER) infected macrophages. Iran. J. Public Health. 2011, 40, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fatima, F.; Khalid, A.; Nazar, N.; Abdalla, M.; Mohomed, H.; Toum, A.M.; et al. In vitro assessment of anticutaneous leishmaniasis activity of some Sudanese plants. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2005, 29, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudvand, H.; Sepahvand, P.; Jahanbakhsh, S.; Azadpour, M. Evaluation of the antileishmanial and cytotoxic effects of various extracts of garlic (Allium sativum) on Leishmania tropica. J Parasit Dis. 2016, 40, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, U.; Velpandian, T.; Sharma, P.; Singh, S. Evaluation of anti-leishmanial activity of selected Indian plants known to have antimicrobial properties. Parasitol. Res. 2009, 105, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabwoba, B.W.; Anjili, C.O.; Ngeiywa, M.M.; Ngure, P.K.; Kigondu, E.M. , Ingonga, J.; Makwali, J. Experimental chemotherapy with Allium sativum (Liliaceae) methanolic extract in rodents infected with Leishmania major and Leishmania donovani. J. Vector Borne Dis. 2010, 47, 160-167. 47,.

- Krstin, S.; Sobeh, M.; Braun, M.S.; Wink, M. Anti-parasitic activities of Allium sativum and Allium cepa against Trypanosoma b. brucei and Leishmania tarentolae. Medicines. 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, C.D.; Nolan, L.L.; Zatyrka, S.A. Antileshmanial properties of Allium sativum extracts and derivatives. Acta Hortic. 1996, 426, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinuthia, K.G.; Anjili, O.C.; Kabiru, W.E.; Kigondu, M.E.; Ingonga, M.J.; Gikonyo, K.N. Toxicity and efficacy of aqueous crude extracts from Allium sativum, Callistemon citrinus and Moringa stenopetala against L. Major. j. res. innov. 2015, 3, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoylenko, V.; Chuck Dunbar, D.; Abdul Gafur, Md.; Khan, S.I.; Ross, S.A.; Mossa, J.S.; El-Feraly, F.S.; Tekwani, B.L.; Bosselaers, J.; Muhammad, I. Antiparasitic, nematicidal and antifouling constituents from juniperus berries. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 1570–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A.; Saeedi, M.; Fakhar, M.; Morteza-Semnani, K.; Keighobadi, M. ; Hosseini Teshnizi, S; Kelidari, H.R.; Sadjadi, S. Antileishmanial Activity of Lavandula angustifolia and Rosmarinus officinalis essential oils and nano-emulsions on Leishmania major (MRHO/IR/75/ER). Iran. J. Parasitol. 2017, 12, 622–631. 12,.

- Bahmani, M.; Saki, K.; Ezatpour, B.; Shahasavari, S.; Eftekhari, Z.; Jelodari, M.; Rafieian, M. Leishmaniosis phytotherapy: Review of plants used in Iranian traditional medicine on leishmaniasis. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 673–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).