Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

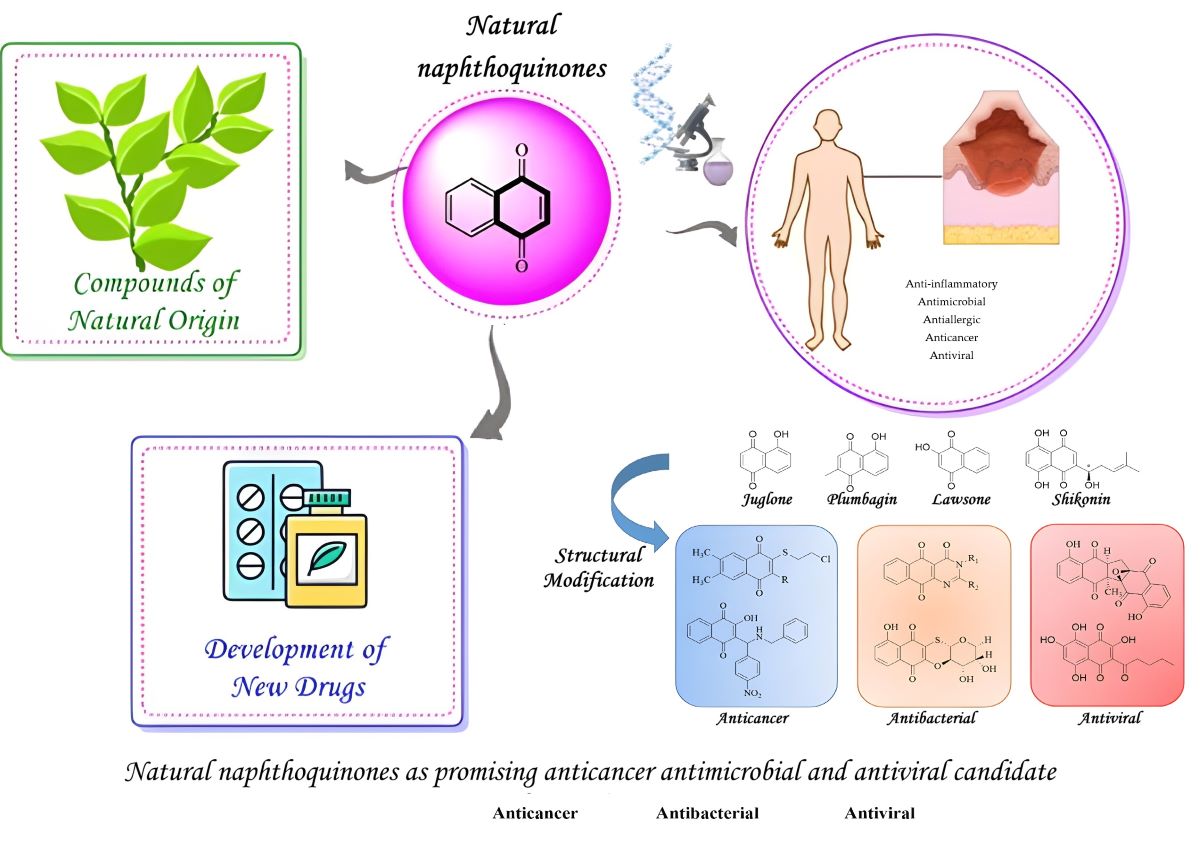

1. Introduction

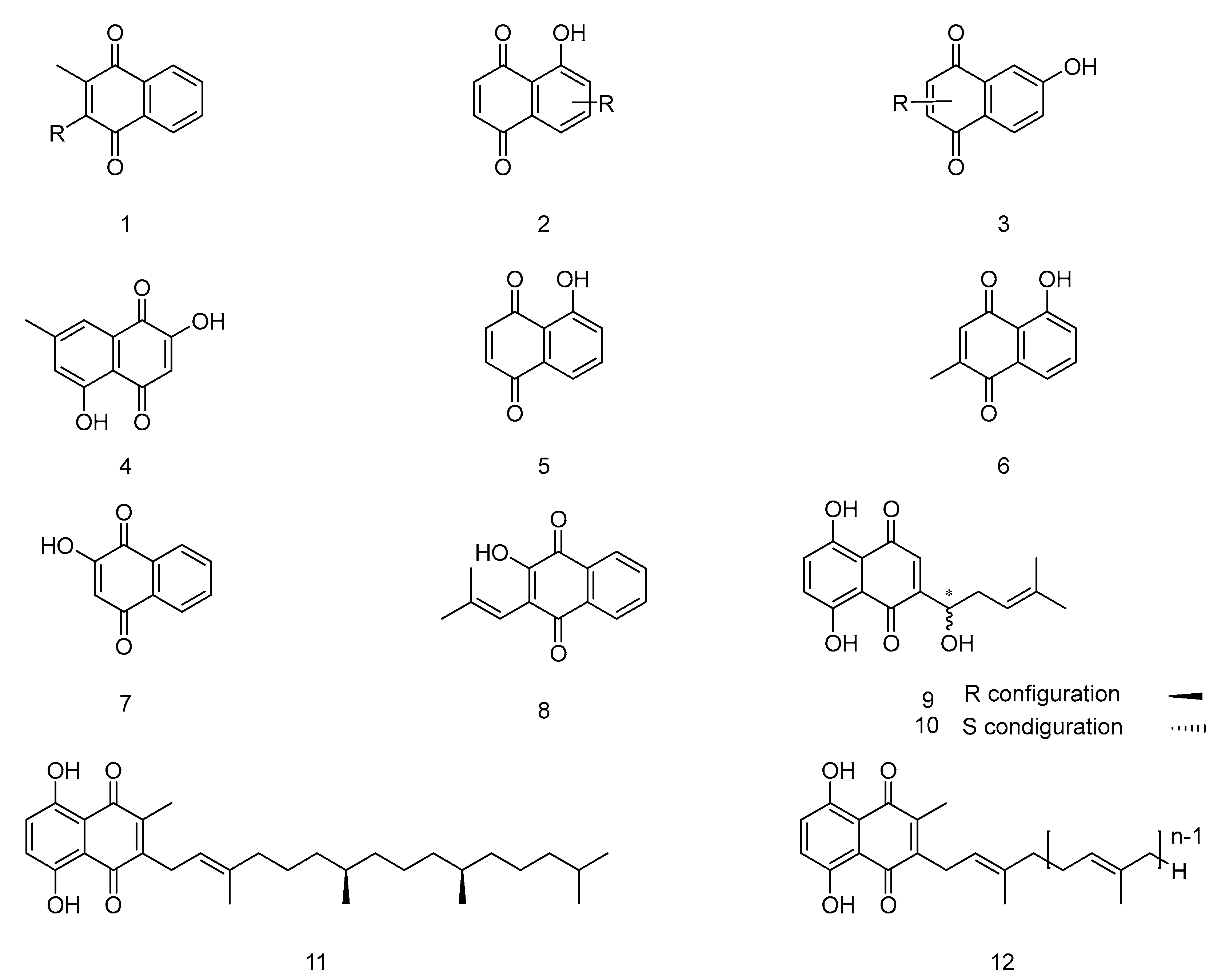

2. Natural 1,4-naphthoquinones and Synthetic Studies

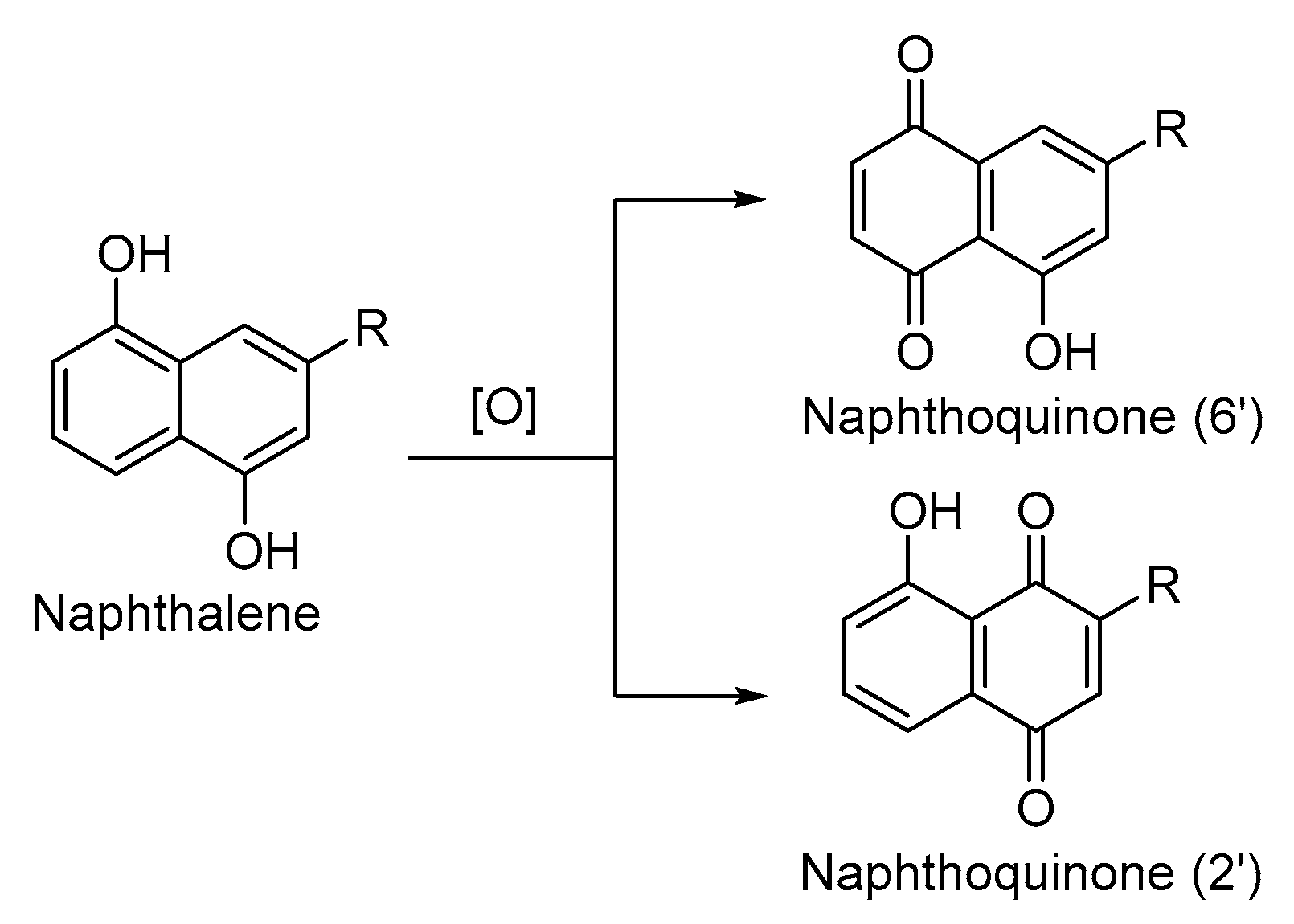

2.1. Synthesis of Natural 1,4-naphthoquinones

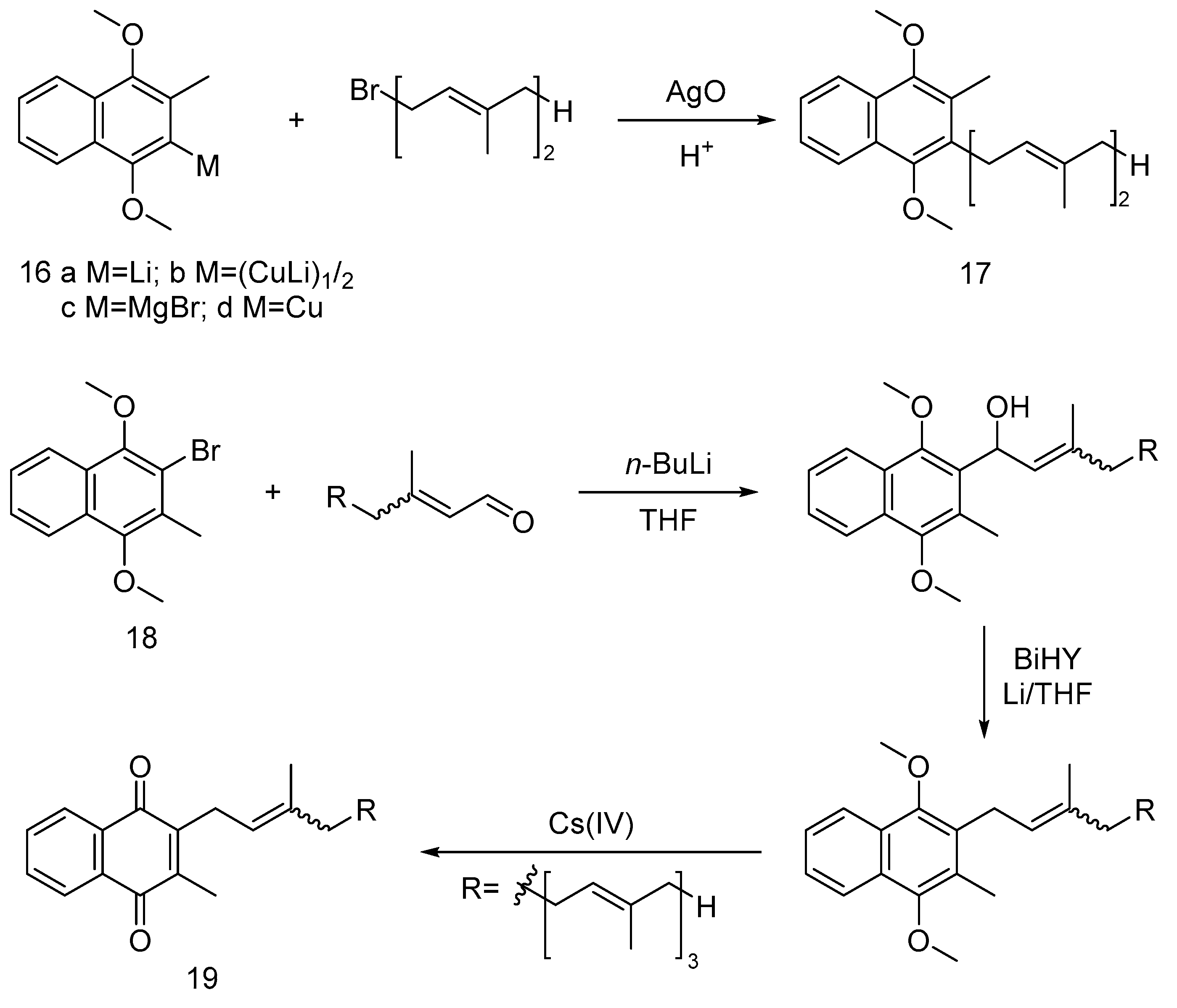

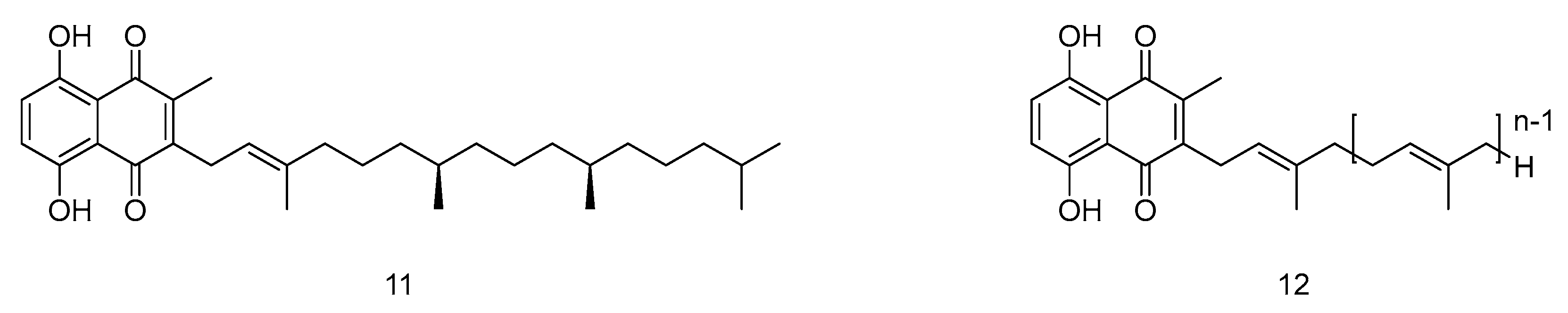

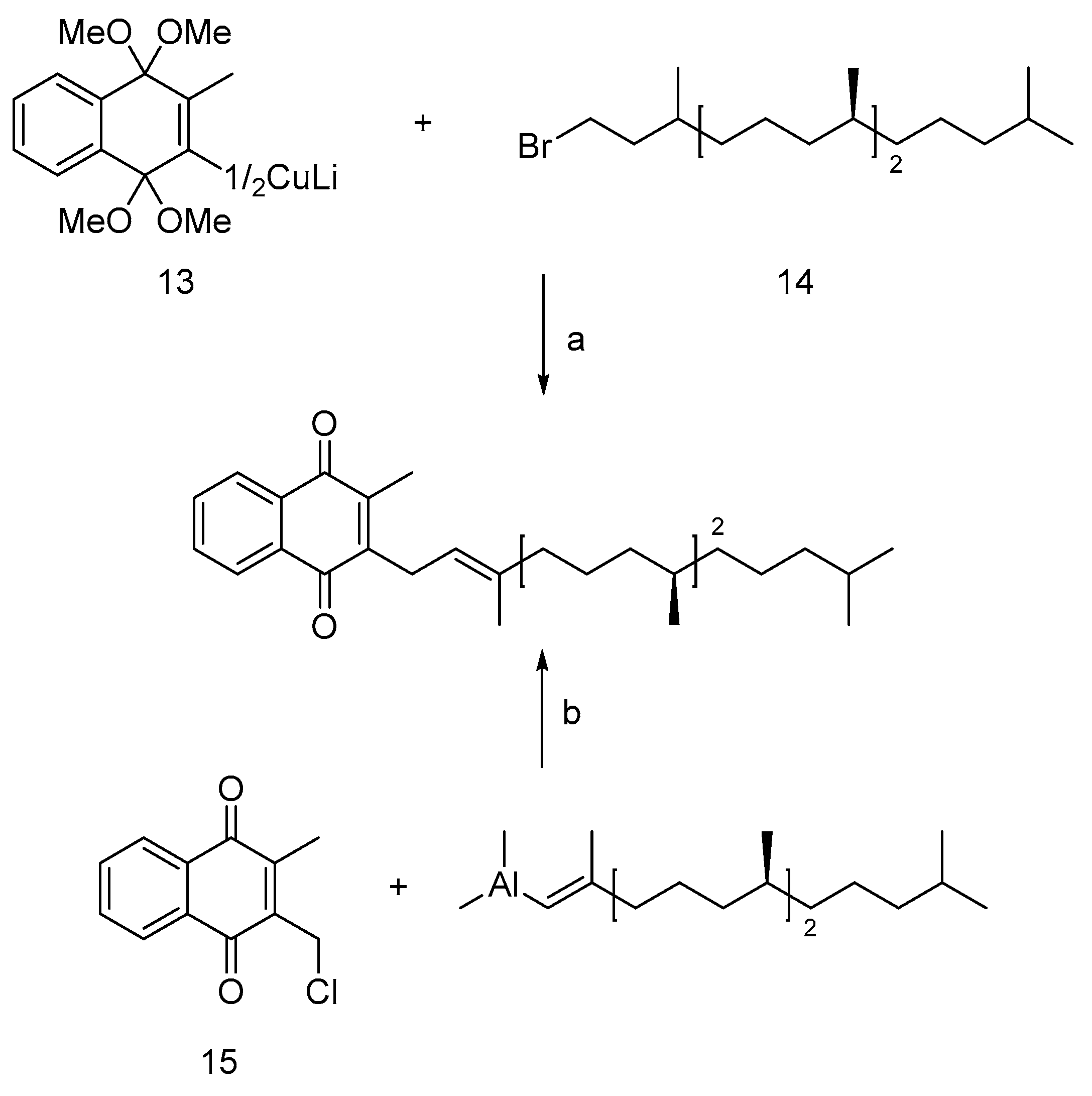

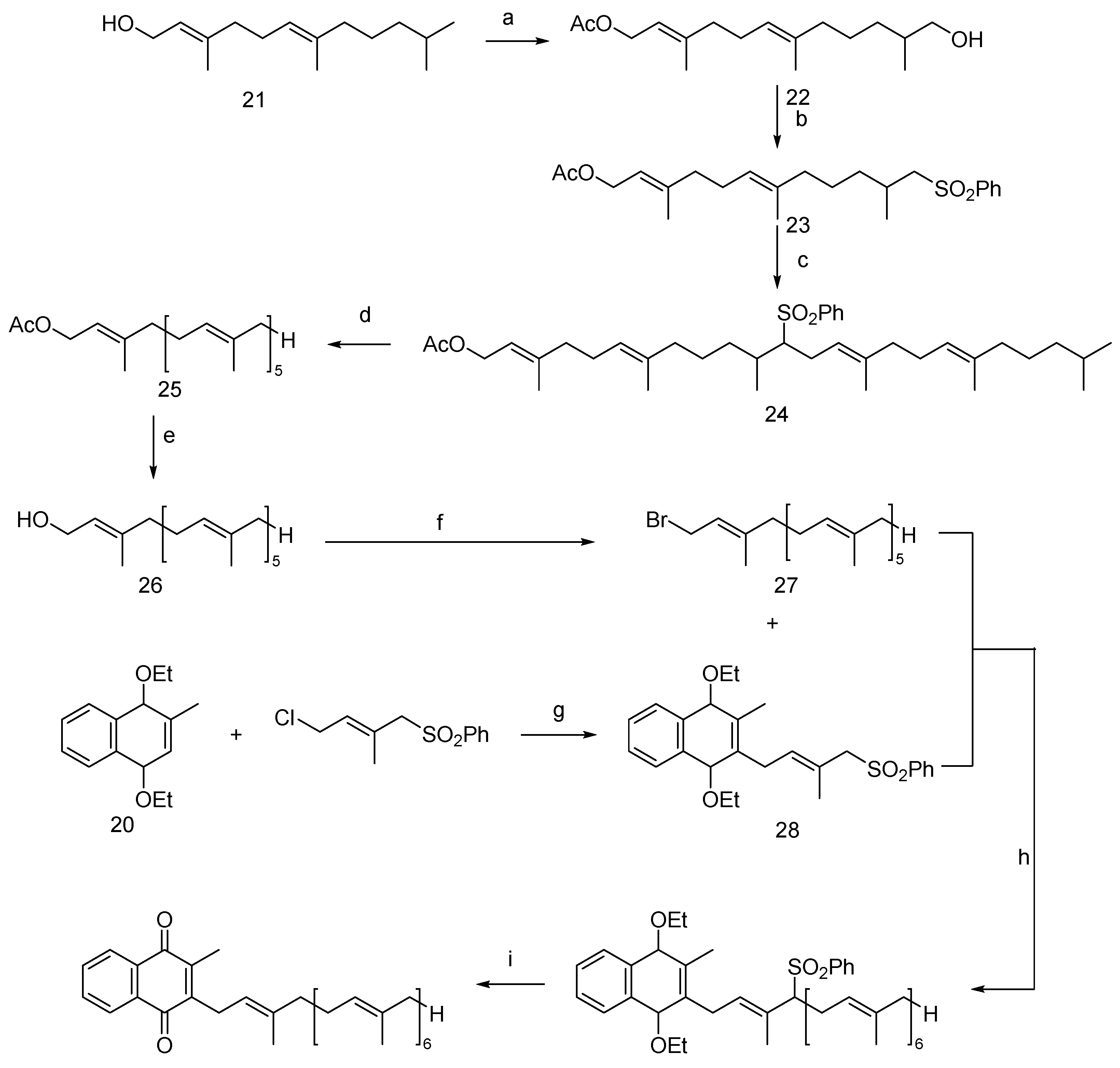

2.1.1. Synthesis of Vitamin K and Its Analogs

2.1.2. Synthesis of Juglone

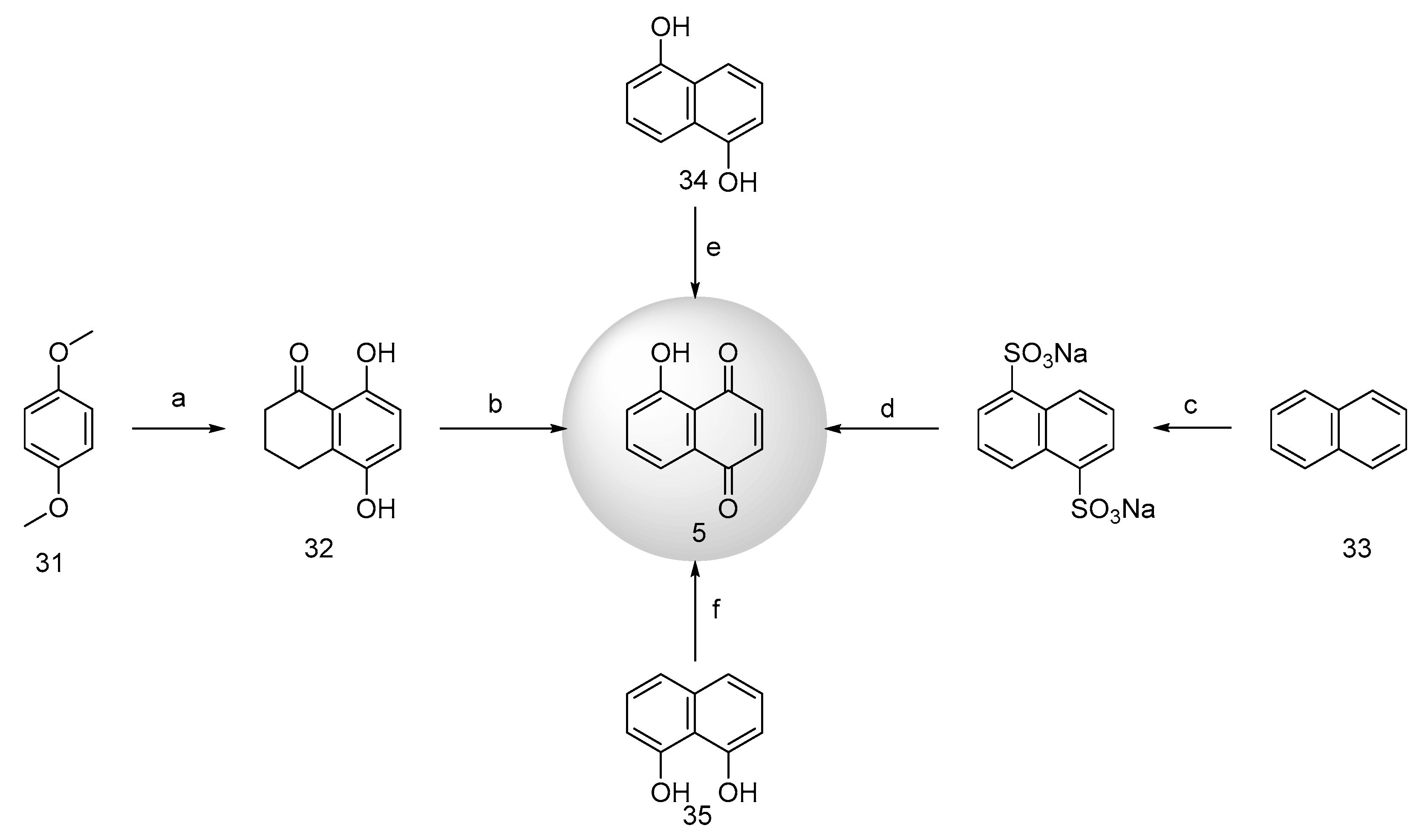

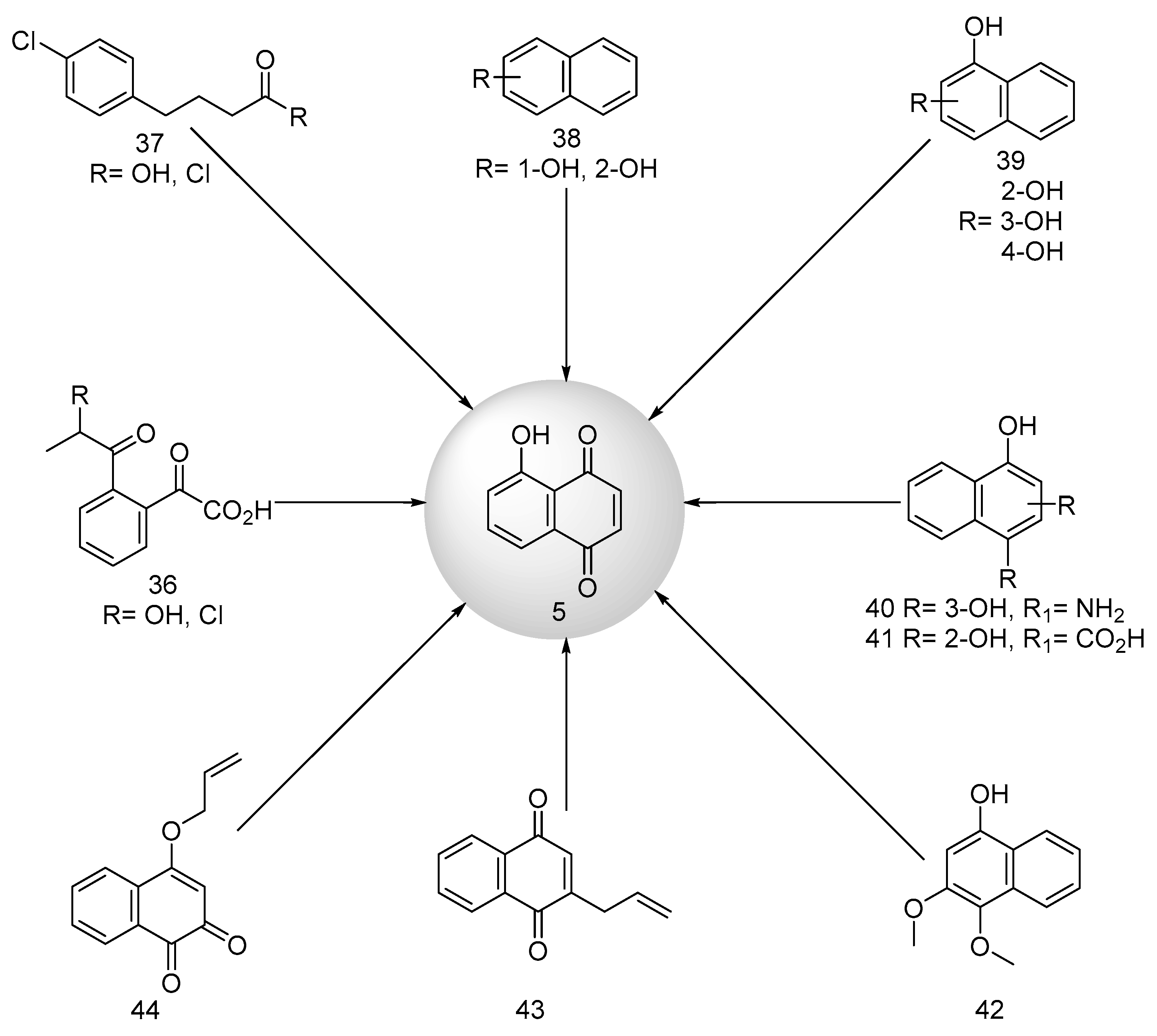

2.1.3. Synthesis of Lawsone

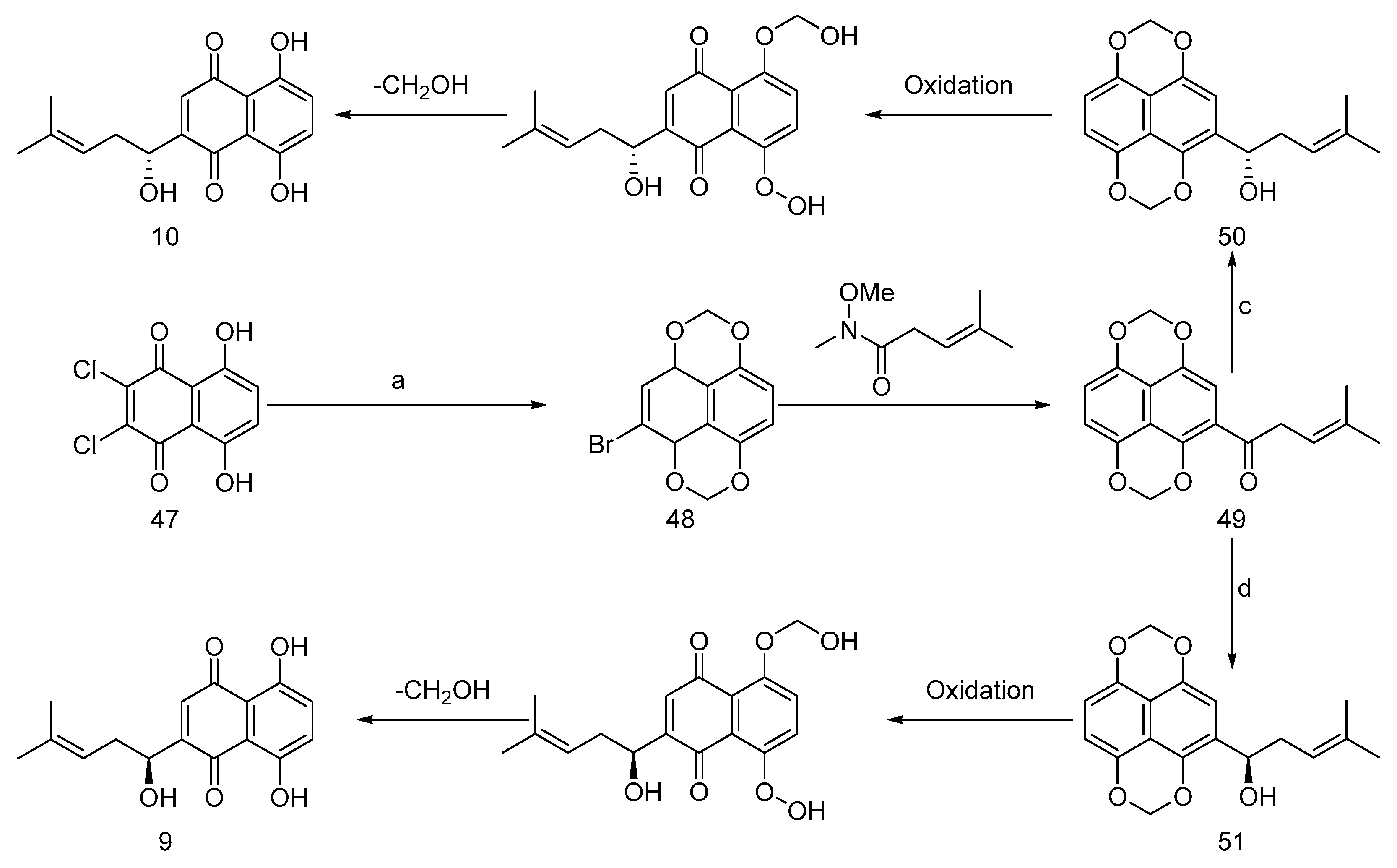

2.1.4. Synthesis of Shikonin and Alkannin

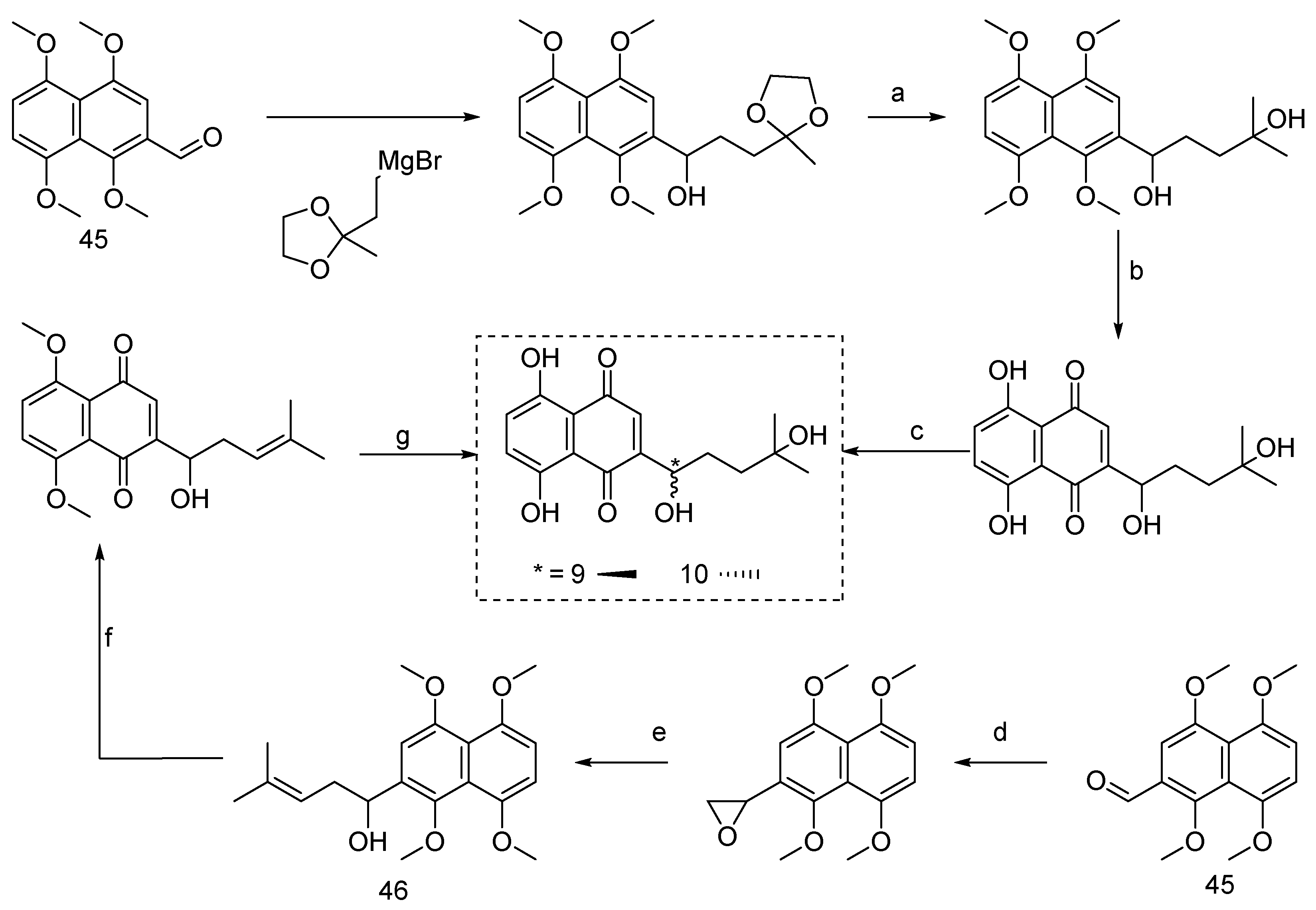

2.2. Biological Activity of 1,4-naphthoquinone Derivatives

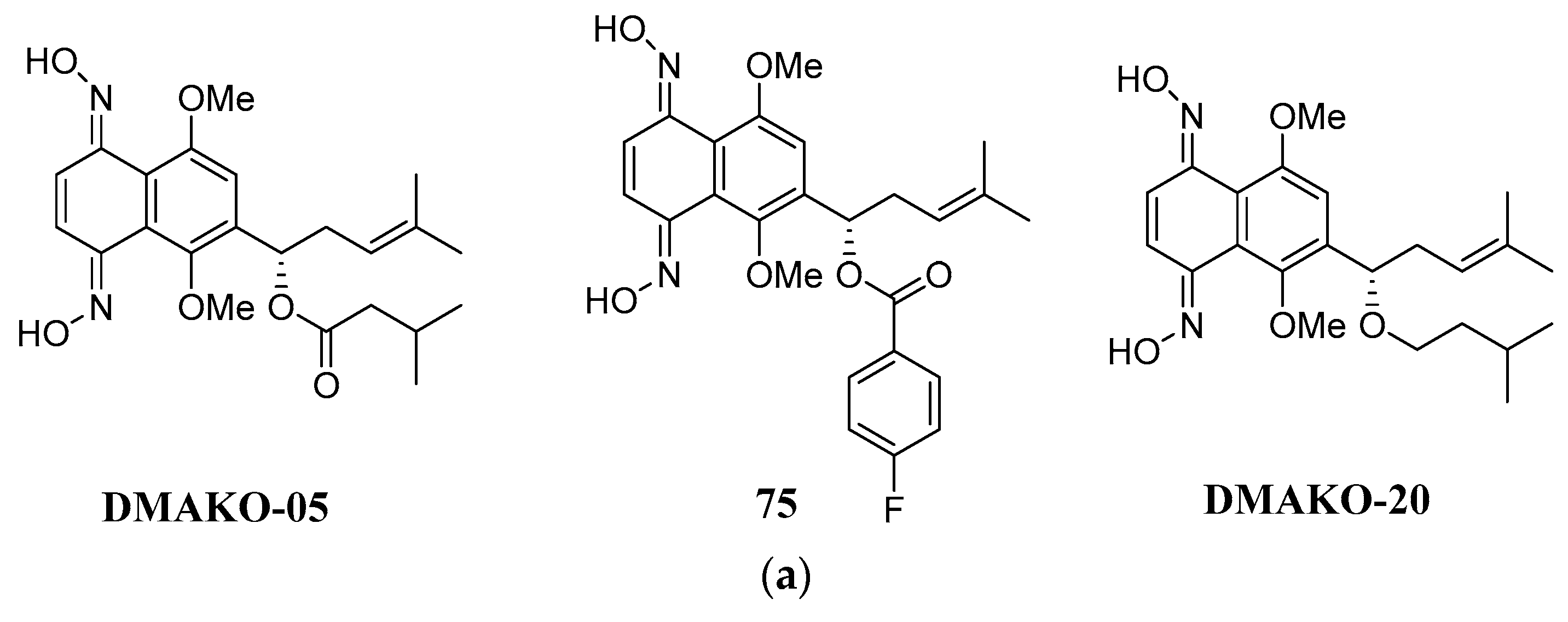

| IC50 (μM) | |||||

| DMAKO-20 | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | DU145 | 22RV1 | K562 |

| 11.4±2.2 | 9.1±1.2 | 15.3±1.7 | 20.4±2.5 | 0.4±0.1 | |

| SKOV-3 | HepG2 | PANC | A549 | MGC-803 | |

| 20.6±1.6 | 2.2±0.5 | 2.3±0.4 | 16.8±0.9 | 2.33±0.89 | |

| HCT-15 | HCT-116 | VEC∆ | HSF∆ | HL-7702∆ | |

| 0.63±0.10 | 1.08±0.21 | 61.9±2.5 | 75.9±2.1 | 66.5±3.9 | |

3. Antimicrobial Activity

4. Antiviral Activity

Miscellaneous

5. Conclusions and Further Perspectives

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. , Cancer statistics, 2020. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2020, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grivennikov, S.I.; Greten, F.R.; Karin, M. , Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzung, B.G.; Masters, S.B.; Trevor, A.J. , Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 11th Edition. Acta Agronomica Sinica 2009, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, M. , Side Effects of Chemotherapy. 2018.

- Mishra, A.P.; Salehi, B.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Pezzani, R.; Kobarfard, F.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Nigam, M. , Programmed Cell Death, from a Cancer Perspective: An Overview. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy 2018, 22, 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Alenazy, R.; Gu, X.; Polyak, S.W.; Zhang, P.; Sykes, M.J.; Zhang, N.; Venter, H.; Ma, S. , Design and structural optimization of novel 2H-benzo[h]chromene derivatives that target AcrB and reverse bacterial multidrug resistance. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 213, 113049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, S.; Khan, T.; Adil, M.; Khan, A. , Mechanistic aspects of plant-based silver nanoparticles against multi-drug resistant bacteria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.R. , Anti-Cancer Activities of 1,4-Naphthoquinones: A QSAR Study. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2006, 6, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.N.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Krishtopina, A.S.; Makarov, V.G. , Naphthoquinone pigments from sea urchins: Chemistry and pharmacology. Phytochemistry Reviews 2018, 17, 509–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldi, R.; Horrigan, S.K.; Cholody, M.W.; Padia, J.; Sorna, V.; Bearss, J.; Gilcrease, G.; Bhalla, K.; Verma, A.; Vankayalapati, H.; Sharma, S. , Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of a Series of Anthracene-9,10-dione Dioxime β-Catenin Pathway Inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 58, 5854–5862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, N.; Binneman, B.; Mahapatra, A.; van de Venter, M.; du Plessis-Stoman, D.; Boukes, G.; Houghton, P.; Marion Meyer, J.J.; Lall, N. , Cytotoxicity of synthesized 1,4-naphthoquinone analogues on selected human cancer cell lines. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 22, 5013–5019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, G.-Y.; Kim, Y.; You, Y.-J.; Cho, H.; Kim, S.-H.; Sok, D.-E.; Ahn, B.-Z. , Naphthazarin Derivatives (VI): Synthesis, Inhibitory Effect on DNA Topoisomerase-I and Antiproliferative Activity of 2- or 6-(1-Oxyiminoalkyl)-5,8-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinones. Archiv der Pharmazie 2000, 333, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durchschein, C.; Hufner, A.; Rinner, B.; Stallinger, A.; Deutsch, A.; Lohberger, B.; Bauer, R.; Kretschmer, N. In Molecules, 2018; Vol. 23.

- V. P. Papageorgiou, A.N.A., V. F. Samanidou, I. N. Papadoyannis, Recent Advances in Chemistry, Biology and Biotechnology of Alkannins and Shikonins. Current Organic Chemistry 2006, 10, 2123–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, V.K.; Kumar, S. , Recent development on naphthoquinone derivatives and their therapeutic applications as anticancer agents. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2013, 23, 1087–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-H.; Lo, C.-Y.; Gwo, Z.-H.; Lin, H.-J.; Chen, L.-G.; Kuo, C.-D.; Wu, J.-Y. In Molecules, 2015; Vol. 20, pp 11994-12015.

- Pingaew, R.; Prachayasittikul, V.; Worachartcheewan, A.; Nantasenamat, C.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. , Novel 1,4-naphthoquinone-based sulfonamides: Synthesis, QSAR, anticancer and antimalarial studies. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 103, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeer, C.; Schurgers, L.J. , A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW OF VITAMIN K AND VITAMIN K ANTAGONISTS. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America 2000, 14, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansell; Jack; Hirsh; Poller; Leon; Bussey; Henry; Jacobson; Alan; Hylek, The Pharmacology and Management of the Vitamin K Antagonists. CHEST, 2004.

- Pucaj, K.; Rasmussen, H.; Møller, M.; Preston, T. , Safety and toxicological evaluation of a synthetic vitamin K2, menaquinone-7. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Almquist, H.J.; Klose, A.A. , SYNTHETIC AND NATURAL ANTIHEMORRHAGIC COMPOUNDS. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1939, 61, 2557–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieser, L.F.; Campbell, W.P.; Fry, E.M.; Gates, M.D. , SYNTHETIC APPROACH TO VITAMIN K1. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1939, 61, 2559–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand; L.; Chenard; Michael; J.; Manning; Peter; W.; Raynolds; John, Organocopper chemistry of quinone bisketals. Application to the synthesis of isoprenoid quinone systems. Journal of Organic Chemistry, 1980.

- Lipshutz, B.H.; Kim, S.-k.; Mollard, P.; Stevens, K.L. , An expeditious route to CoQn, vitamins K1 and K2, and related allylated para-quinones utilizing Ni(0) catalysis. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.D.; Rapoport, H. , Synthesis of menaquinones. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1974, 96, 8046–8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcias, X.; Ballester, P.; Capo, M.; Saa, J.M. , (2)DELTA-STEREOCONTROLLED ENTRY TO (E)-PRENYL OR (Z)-PRENYL AROMATICS AND AND QUINONES - SYNTHESIS OF MENAQUINONE-4. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1994, 59, 5093–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajewski, K.; Kutner, A.; Dzikowska, J.; Gutowska, R.; Napiórkowski, M.; Winiarski, J.; Kubiszewski, M.; Jedynak, L.; Morzycki, J.; Witkowski, S. , Process for preparation of NK-7 type of vitamin K2. 2015.

- Strugstad, M.P.; Despotovski, S. , A summary of extraction, properties, and potential uses of juglone: A literature review. Journal of Ecosystems and Management, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Inbaraj, J.J.; Chignell, C.F. , Cytotoxic Action of Juglone and Plumbagin: A Mechanistic Study Using HaCaT Keratinocytes. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2004, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.-h.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, Q.-j.; Li, S.-s. , An Efficient Multigram Synthesis of Juglone Methyl Ether. Journal of Chemical Research 2015, 39, 553–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalafy, J.; Bruce, J.M. , OXIDATIVE DEHYDROGENATION OF 1-TETRALONES: SYNTHESIS OF JUGLONE, NAPHTHAZARIN, AND α-HYDROXYANTHRAQUINONES. 2002.

- Mamchur, A.V.; Gorbas, L.F.; Galstyan, G.A. , Use of Ozone in Synthesis of 5-Hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry 2001, 74, 1405–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.a.X.L. , One-pot synthesis of pecan quinone from acetic anhydride, H2O2 and 1,5-dihydroxynaphthol. Chinese Journal of Applied Chemistry 2007, 24, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi, M.; Akhbari, M. , Efficient Solvent-Free Oxidation of Phenols to p-Quinones with Iodic Acid on the Surface of K10 Montmorillonite. Russian Journal of Organic Chemistry 2005, 41, 935–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, A.C. , Natural ingredients for colouring and styling. International Journal of Cosmetic Science 2002, 24, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama, W.S.; Hassanien, A.E.-D.E.; Zoorob, H.H. , Advanced Routes in Synthesis and Reactions of Lawsone Molecules (2-Hydroxynaphthalene-1,4-dione). Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry 2017, 54, 2155–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaissi-Afonso, L.; Oramas-Royo, S.; Ayra-Plasencia, J.; Martín-Rodríguez, P.; García-Luis, J.; Lorenzo-Castrillejo, I.; Fernández-Pérez, L.; Estévez-Braun, A.; Machín, F. , Lawsone, Juglone, and β-Lapachone Derivatives with Enhanced Mitochondrial-Based Toxicity. ACS Chemical Biology 2018, 13, 1950–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieser, L.F.; Berliner, E. , Naphthoquinone antimalarials; general survey. Journal of the American Chemical Society 1948, 70, 3151–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Ueda, S.; Nayeshiro, H.; Moritome, N.; Inouye, H. , Biosynthesis of naphthoqinones and anthraquinones in streptocarpus dunnii cell cultures. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lissel, M. , Über die reaktion von α- und β -tetralon mit kaliumsuperoxid. Tetrahedron Letters 1984, 25, 2213–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Min, M.; Croux, S.; Tournaire, C.; Hocquaux, M.; Jackquet, B.; Oliveros, E.; Maurette, M.-T. , Réactivité du superoxyde de Potassium en phase hétérogéne: Oxydation de naphtalénedios en naphtoquinones hydroxylées. Tetrahedron 1992, 48, 1869–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Kang, E.-H.; Yang, K.-E.; Tong, S.-L.; Fang, C.-G.; Liu, S.-J.; Xiao, F.-S. , High activity in selective catalytic oxidation of naphthol to 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone by molecular oxygen under air pressure over recycled iron porphyrin catalysts. Catalysis Communications 2004, 5, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barange, D.K.; Kavala, V.; Raju, B.R.; Kuo, C.-W.; Tseng, C.; Tu, Y.-C.; Yao, C.-F. , Facile and highly efficient method for the C-alkylation of 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone to nitroalkenes under catalyst-free ‘on water’ conditions. Tetrahedron Letters 2009, 50, 5116–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laatsch, H. , Dimere Naphthochinone, VIII. Synthese 3,3′-dihydroxylierter 2,2′-Bi-1,4-naphthochinone. Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1983, 1983, 1886–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, V.; Assimopoulou, A.; Ballis, A. Alkannins and Shikonins: A New Class of Wound Healing Agents. CMC 2008, 15, 3248–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, V.P.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Couladouros, E.A.; Hepworth, D.; Nicolaou, K.C. , The Chemistry and Biology of Alkannin, Shikonin, and Related Naphthazarin Natural Products. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 1999, 38, 270–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, K.; Li, W. , Shikonin, a Chinese plant-derived naphthoquinone, induces apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through reactive oxygen species: A potential new treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2011, 51, 2259–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, A.; et al. , Total synthesis of shikalkin [(±)-shikonin]. Journal of the Chemical Society Chemical Communications, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Moiseenkov, A.M.; et al. , Total synthesis of shikalkin. Proceedings of the USSR Academy of Sciences 1987, 295, 614–617. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou, K.C.; Hepworth, D. , Concise and Efficient Total Syntheses of Alkannin and Shikonin. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 1998, 37, 839–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, W.; Li, S. , An Efficient Multigram Synthesis of Alkannin and Shikonin. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2012, 2012, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Arpa, P.; Liu, L.F. , Topoisomerase-targeting antitumor drugs. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1989, 989, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

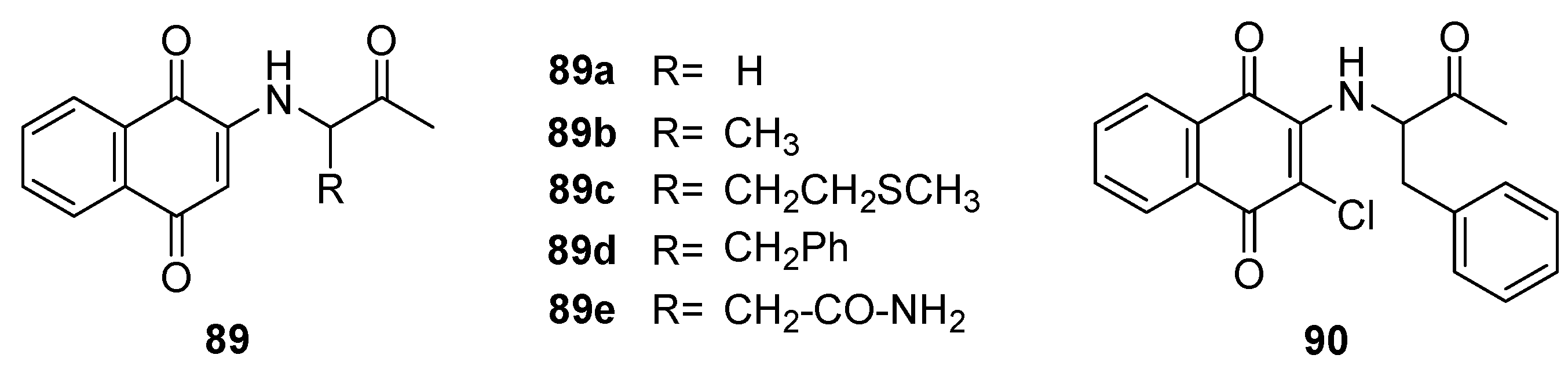

- Prachayasittikul, V.; Pingaew, R.; Worachartcheewan, A.; Nantasenamat, C.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V. , Synthesis, anticancer activity and QSAR study of 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 84, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.L.; Levine, A.J. , The p53 pathway: Positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene 2005, 24, 2899–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.C.; Zhao, J.; Long, F.; Chen, J.Y.; Mu, B.; Jiang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Yang, J. , Efficacy of Shikonin against Esophageal Cancer Cells and its possible mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. J Cancer 2018, 9, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanclemente, M.; et al. , c-RAF Ablation Induces Regression of Advanced Kras/Trp53 Mutant Lung Adenocarcinomas by a Mechanism Independent of MAPK Signaling. Cancer Cell 2018, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-L.; Cho, C.-Y.; Kuo, P.-L.; Huang, Y.-T.; Lin, C.-C. , Plumbagin (5-Hydroxy-2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone) Induces Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in A549 Cells through p53 Accumulation via c-Jun NH<sub>2</sub>-Terminal Kinase-Mediated Phosphorylation at Serine 15 in Vitro and in Vivo. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 2006, 318, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabb, M.M.; Sun, A.; Zhou, C.; Grün, F.; Errandi, J.; Romero, K.; Pham, H.; Inoue, S.; Mallick, S.; Lin, M.; Forman, B.M.; Blumberg, B. , Vitamin K2 Regulation of Bone Homeostasis Is Mediated by the Steroid and Xenobiotic Receptor SXR*. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003, 278, 43919–43927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishima, E.; Ito, J.; Wu, Z.; Nakamura, T.; Wahida, A.; Doll, S.; Tonnus, W.; Nepachalovich, P.; Eggenhofer, E.; Aldrovandi, M.; Henkelmann, B.; Yamada, K.-i.; Wanninger, J.; Zilka, O.; Sato, E.; Feederle, R.; Hass, D.; Maida, A.; Mourão, A.S.D.; Linkermann, A.; Geissler, E.K.; Nakagawa, K.; Abe, T.; Fedorova, M.; Proneth, B.; Pratt, D.A.; Conrad, M. , A non-canonical vitamin K cycle is a potent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature 2022, 608, 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.a.Z.R. , Research progress of antitumor effect of vitamin K2. The Practical Journal of Cancer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

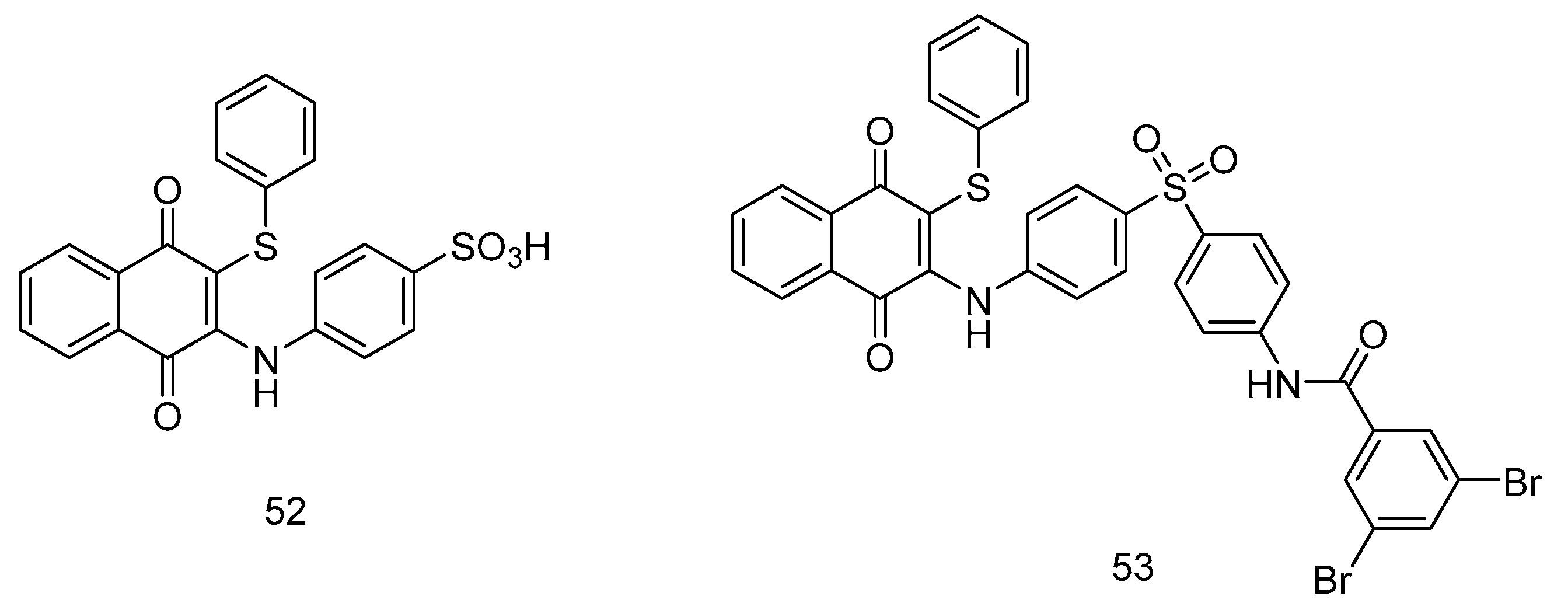

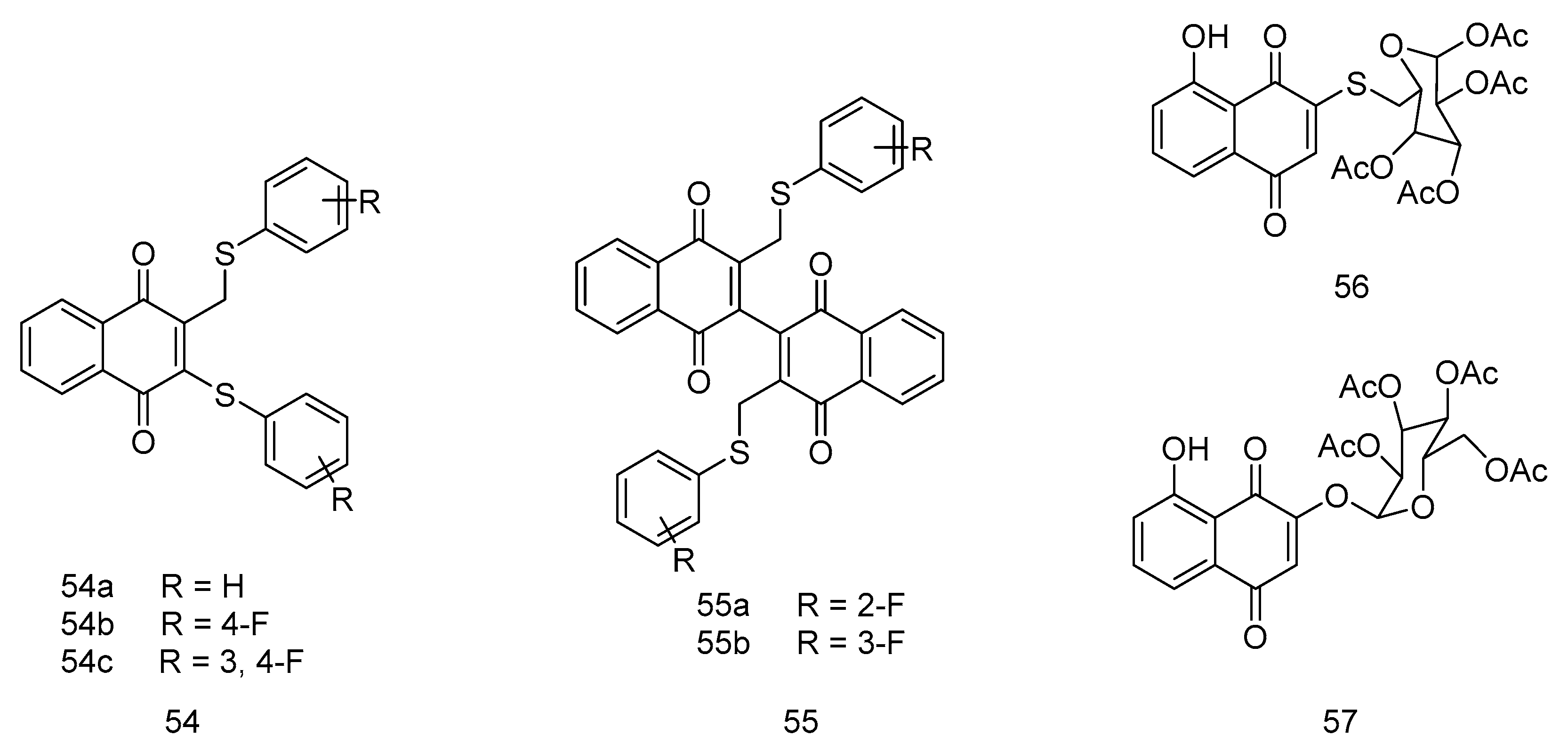

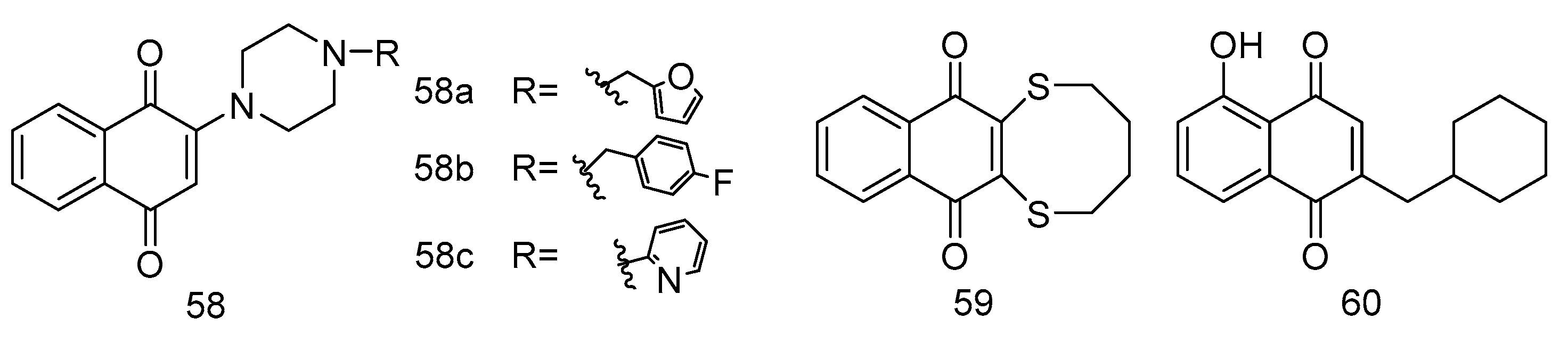

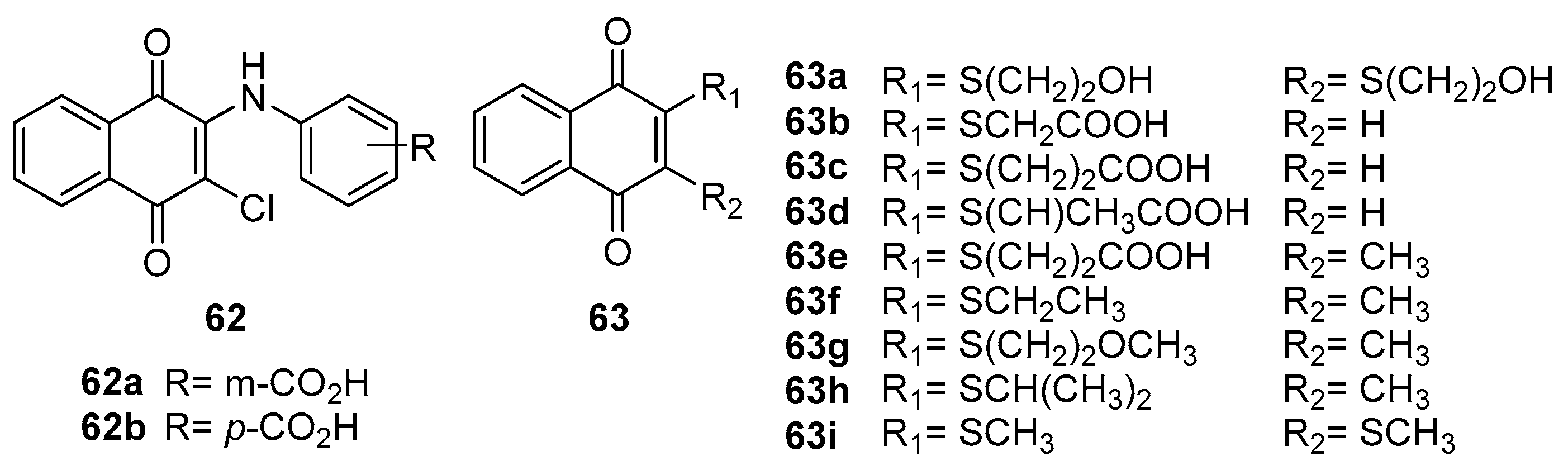

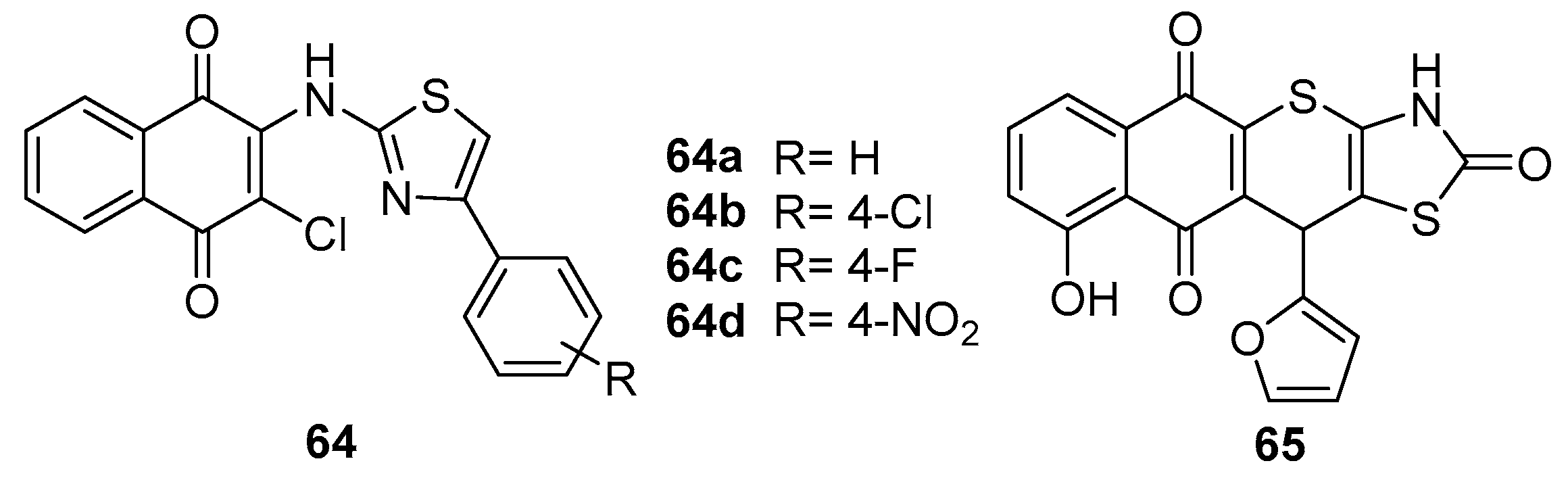

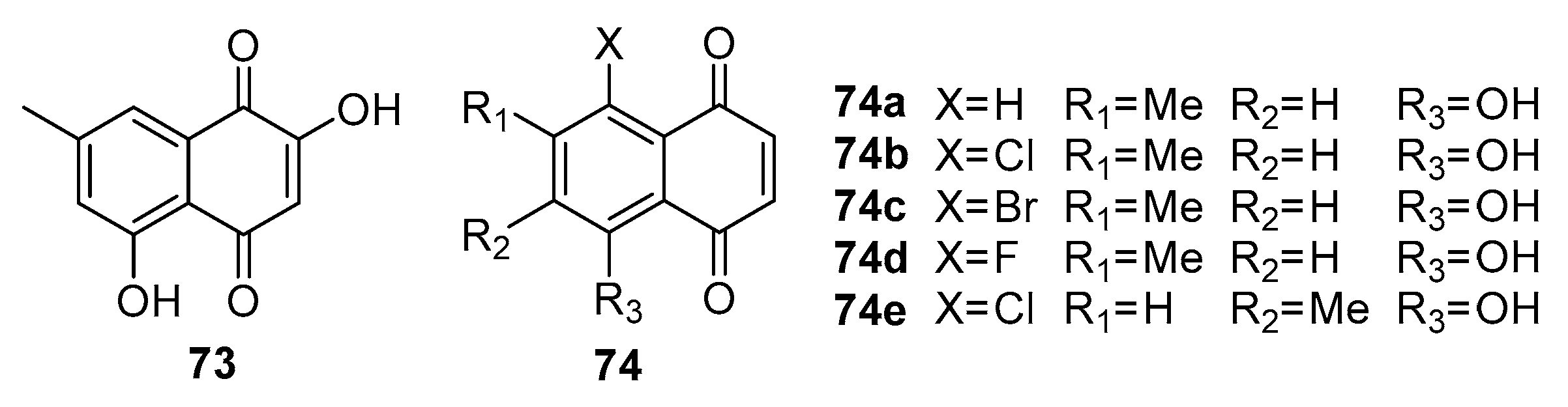

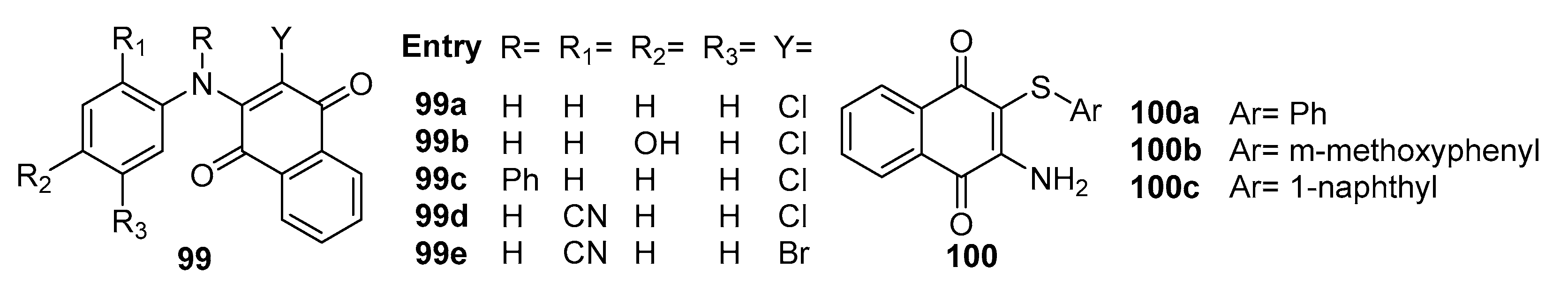

- Ravichandiran, P.; Subramaniyan, S.A.; Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-S.; Park, B.-H.; Shim, K.S.; Yoo, D.J. , Synthesis and Anticancer Evaluation of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives Containing a Phenylaminosulfanyl Moiety. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

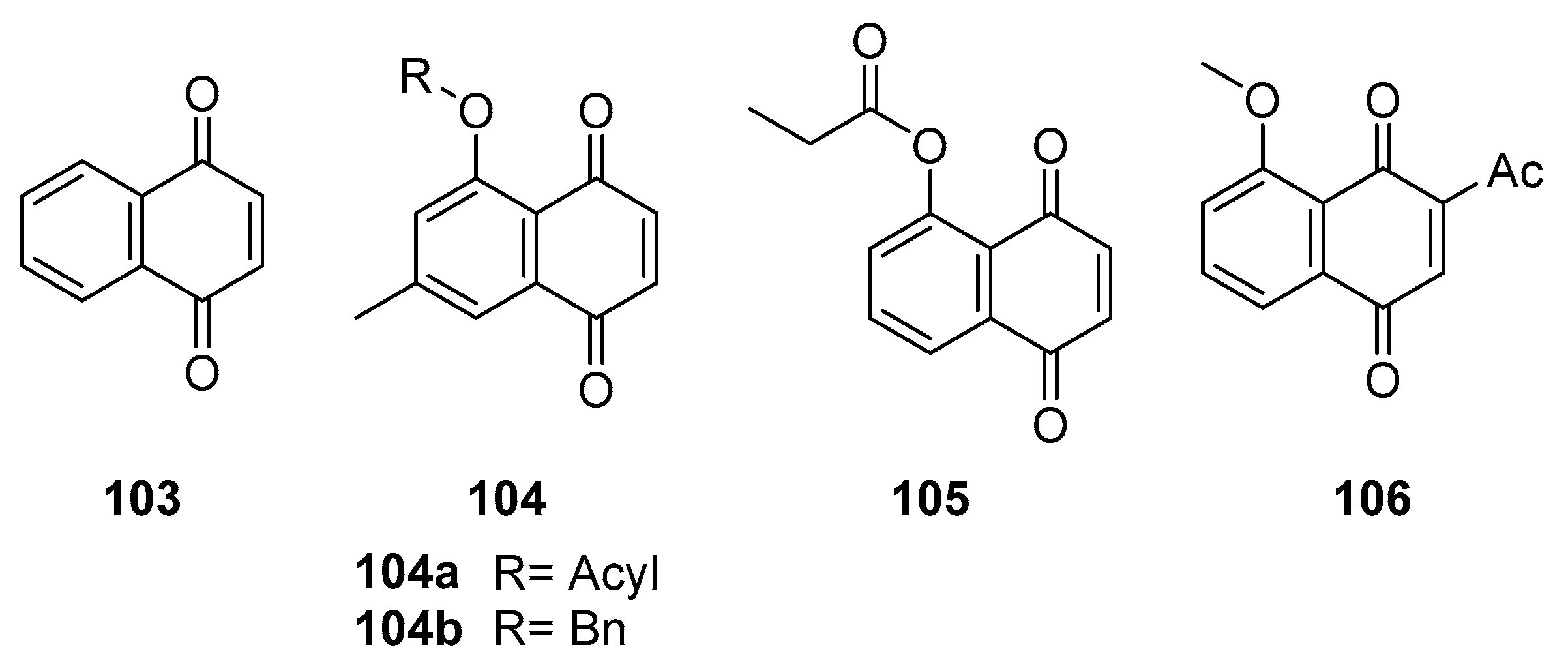

- Wellington, K.W.; Hlatshwayo, V.; Kolesnikova, N.I.; Saha, S.T.; Kaur, M.; Motadi, L.R. , Anticancer activities of vitamin K3 analogues. Investigational New Drugs 2020, 38, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juang, Y.-P.; Tsai, J.-Y.; Gu, W.-L.; Hsu, H.-C.; Lin, C.-L.; Wu, C.-C.; Liang, P.-H. , Discovery of 5-Hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (Juglone) Derivatives as Dual Effective Agents Targeting Platelet-Cancer Interplay through Protein Disulfide Isomerase Inhibition. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 67, 3626–3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

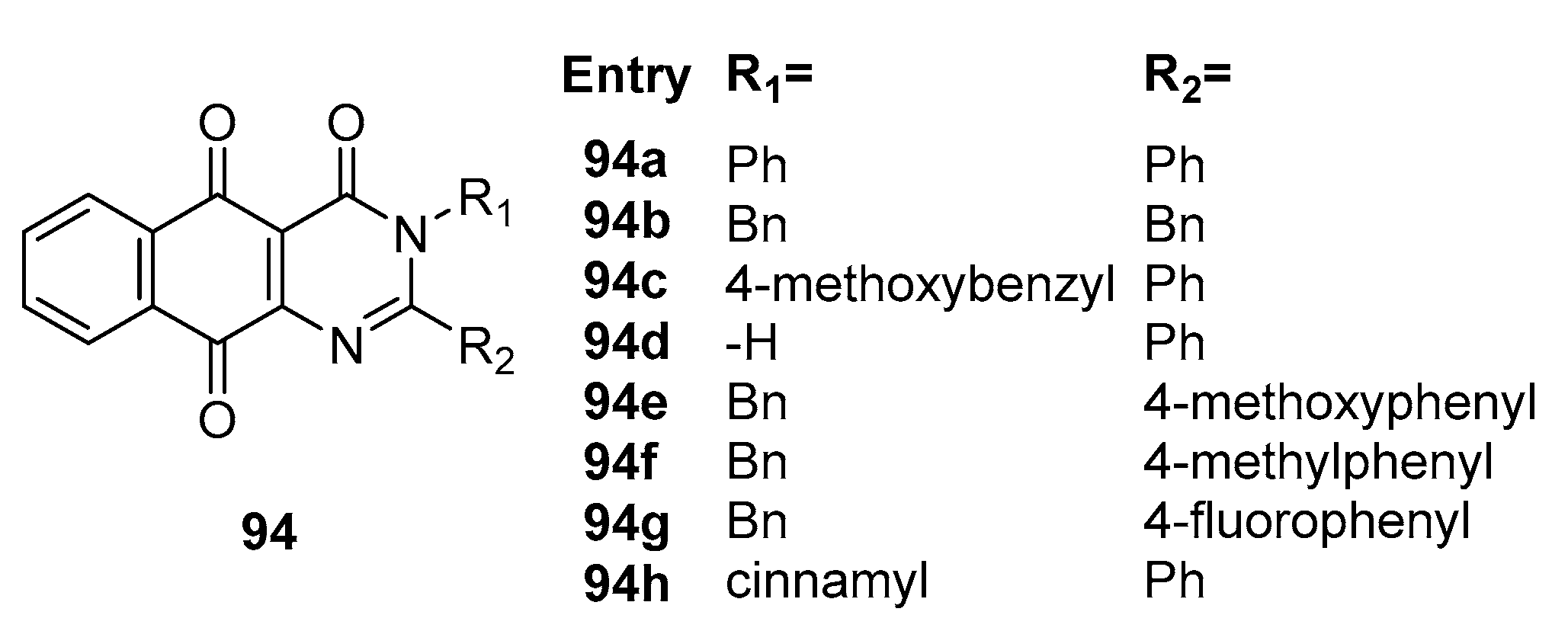

- Gokmen, Z.; Onan, M.E.; Deniz, N.G.; Karakas, D.; Ulukaya, E. , Synthesis and investigation of cytotoxicity of new N- and S,S-substituted-1,4-naphthoquinone (1,4-NQ) derivatives on selected cancer lines. Synthetic Communications 2019, 49, 3008–3016. [Google Scholar]

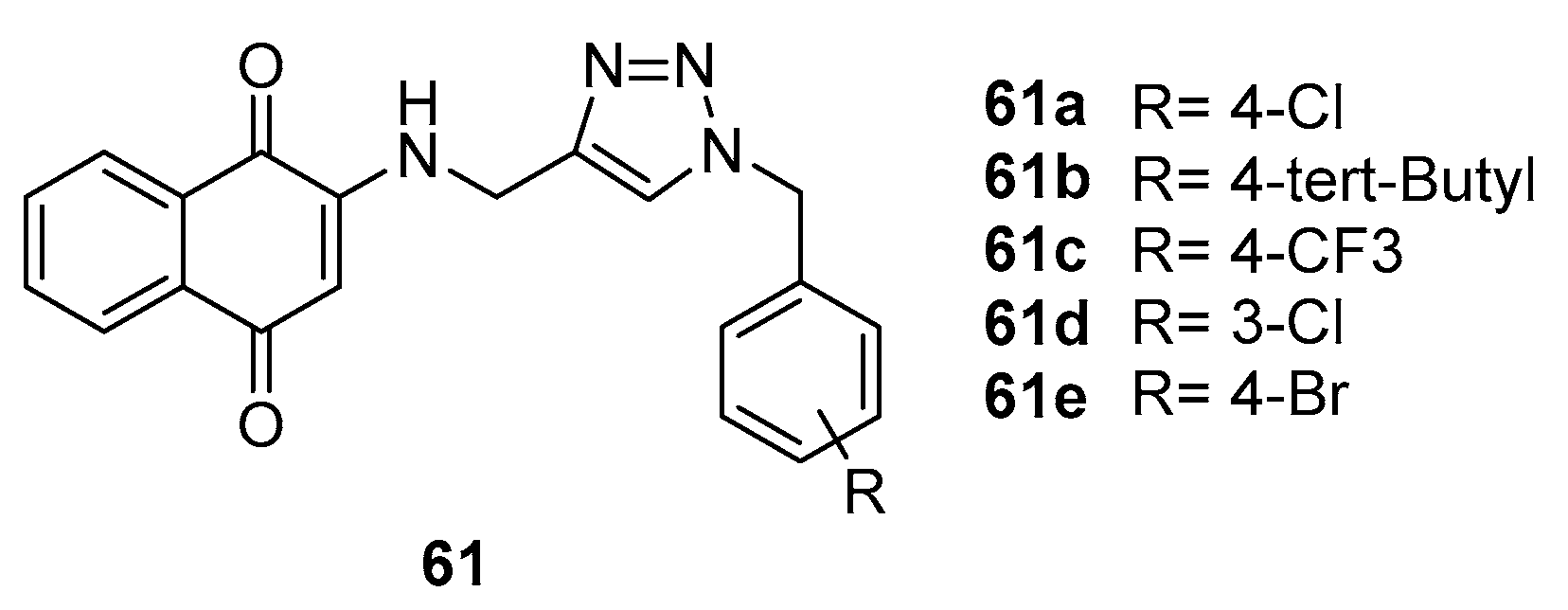

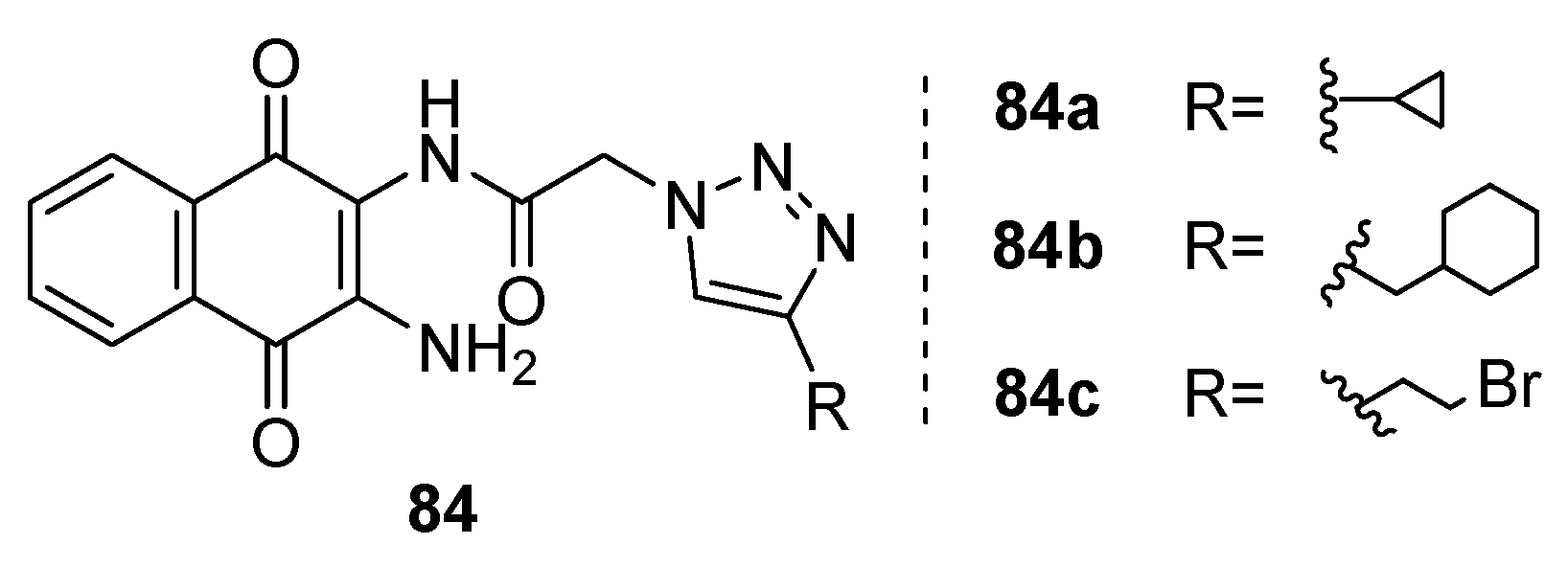

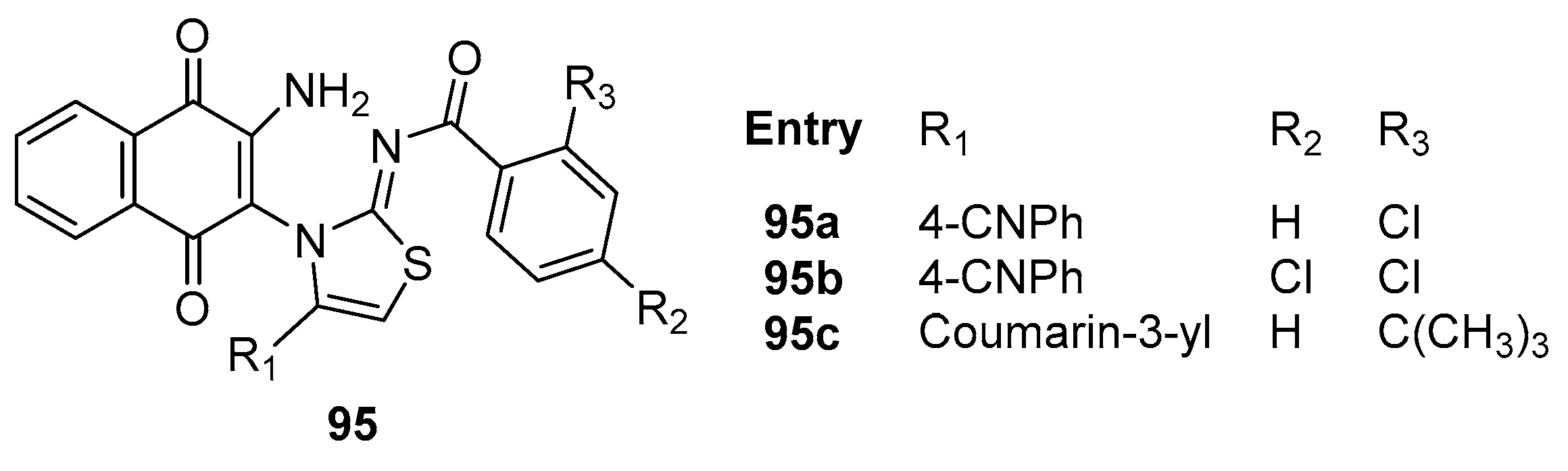

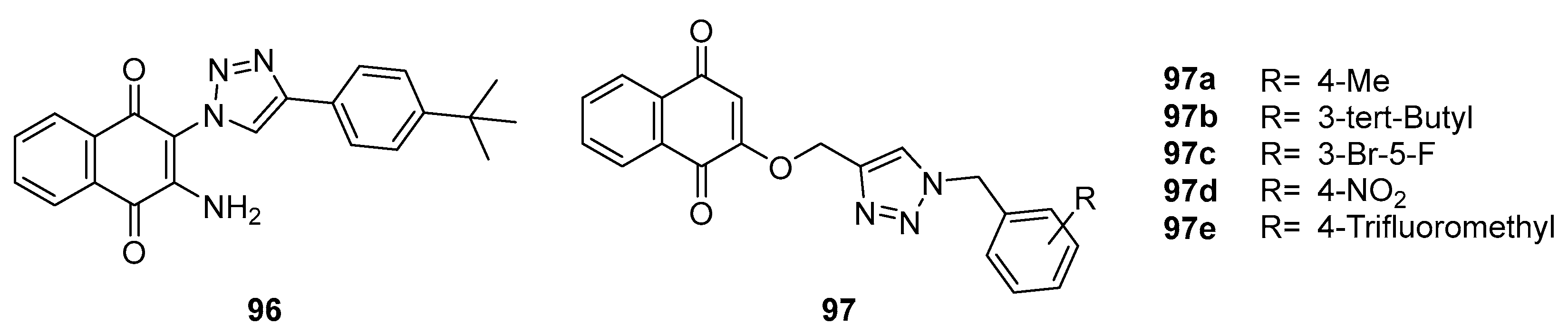

- Gholampour, M.; Ranjbar, S.; Edraki, N.; Mohabbati, M.; Firuzi, O.; Khoshneviszadeh, M. , Click chemistry-assisted synthesis of novel aminonaphthoquinone-1,2,3-triazole hybrids and investigation of their cytotoxicity and cancer cell cycle alterations. Bioorganic Chemistry 2019, 88, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

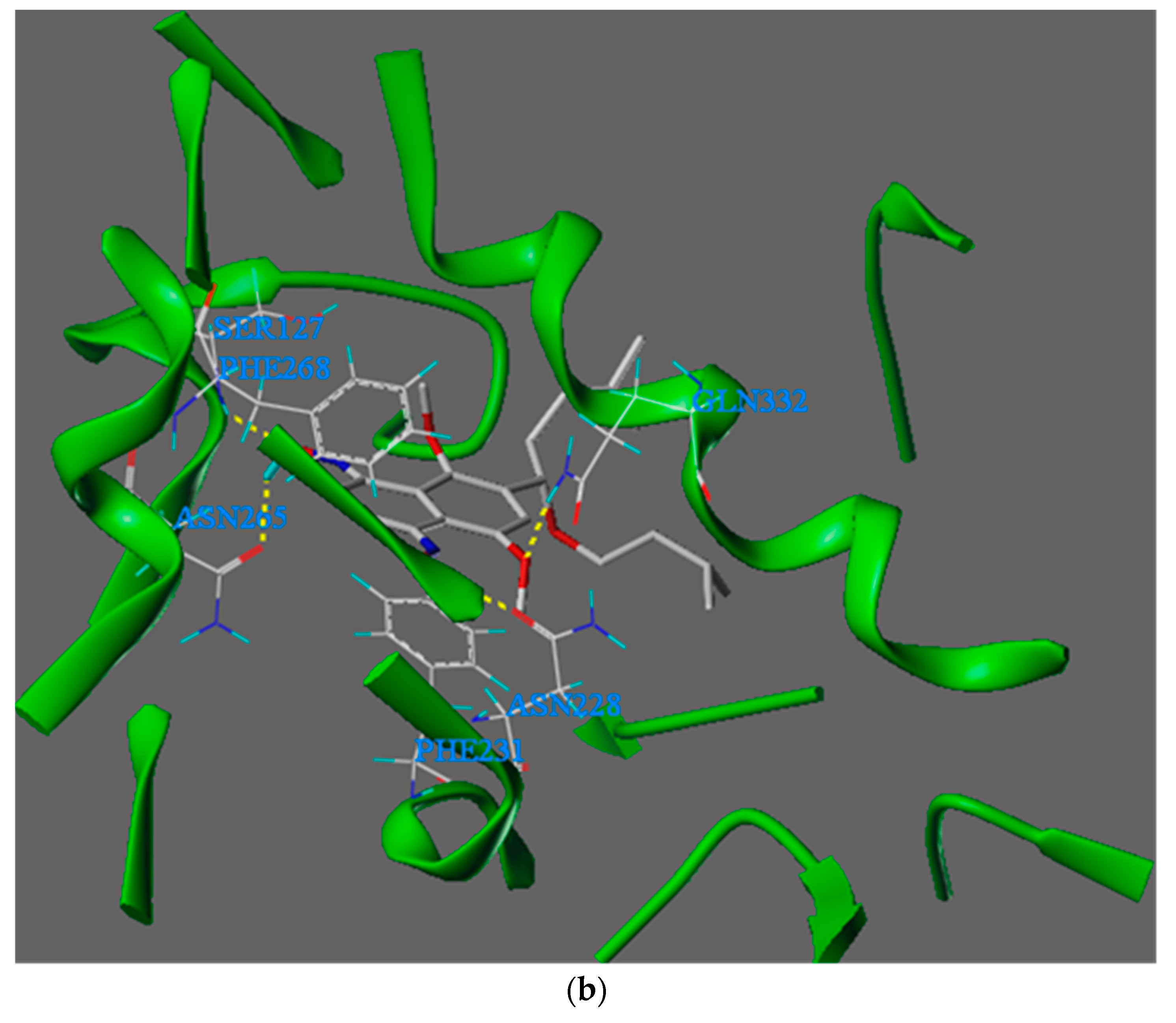

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Karpenko, A.S.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Shibinska, M.O.; Levandovskiy, I.A.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Danilenko, N.V.; Quinn, M.T. , Synthesis, anticancer activity, and molecular modeling of 1,4-naphthoquinones that inhibit MKK7 and Cdc25. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 183, 111719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawode, E.O.; Tandlich, R.; Prinsloo, E.; Isaacs, M.; Hoppe, H.; Seldon, R.; Warner, D.F.; Steenkamp, V.; Kaye, P.T. , Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2-chloro-3-[(thiazol-2-yl)amino]-1,4-naphthoquinones. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2019, 29, 1572–1575. [Google Scholar]

- Ivasechko, I.; Lozynskyi, A.; Senkiv, J.; Roszczenko, P.; Kozak, Y.; Finiuk, N.; Klyuchivska, O.; Kashchak, N.; Manko, N.; Maslyak, Z.; Lesyk, D.; Karkhut, A.; Polovkovych, S.; Czarnomysy, R.; Szewczyk, O.; Kozytskiy, A.; Karpenko, O.; Khyluk, D.; Gzella, A.; Bielawski, K.; Bielawska, A.; Dzubak, P.; Gurska, S.; Hajduch, M.; Stoika, R.; Lesyk, R. , Molecular design, synthesis and anticancer activity of new thiopyrano[2,3-d]thiazoles based on 5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone (juglone). European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 252, 115304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

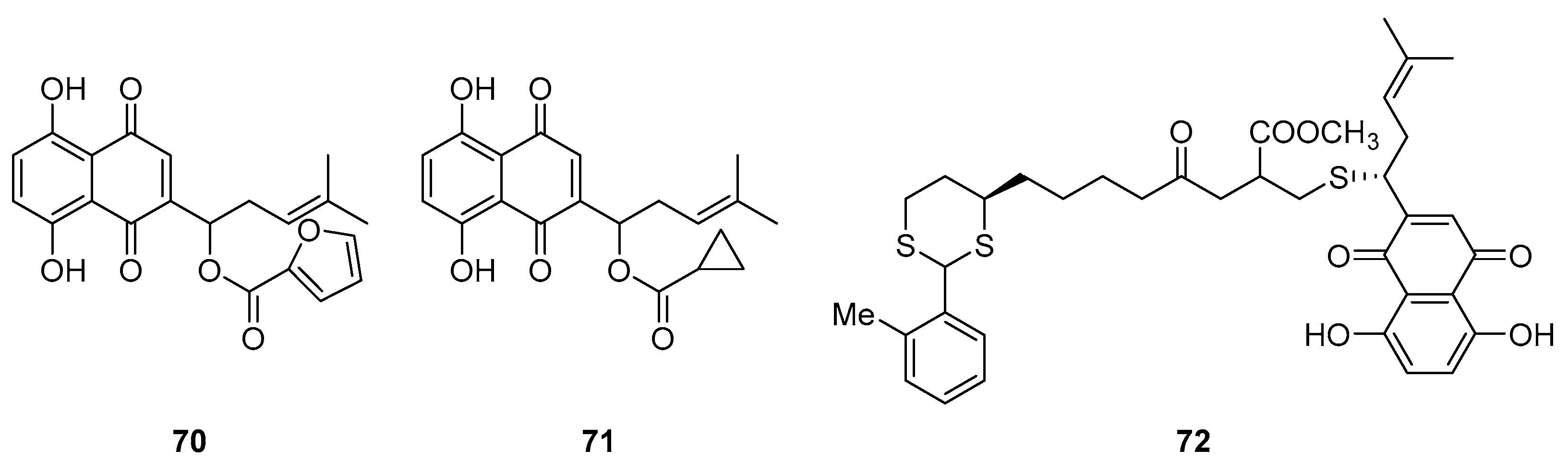

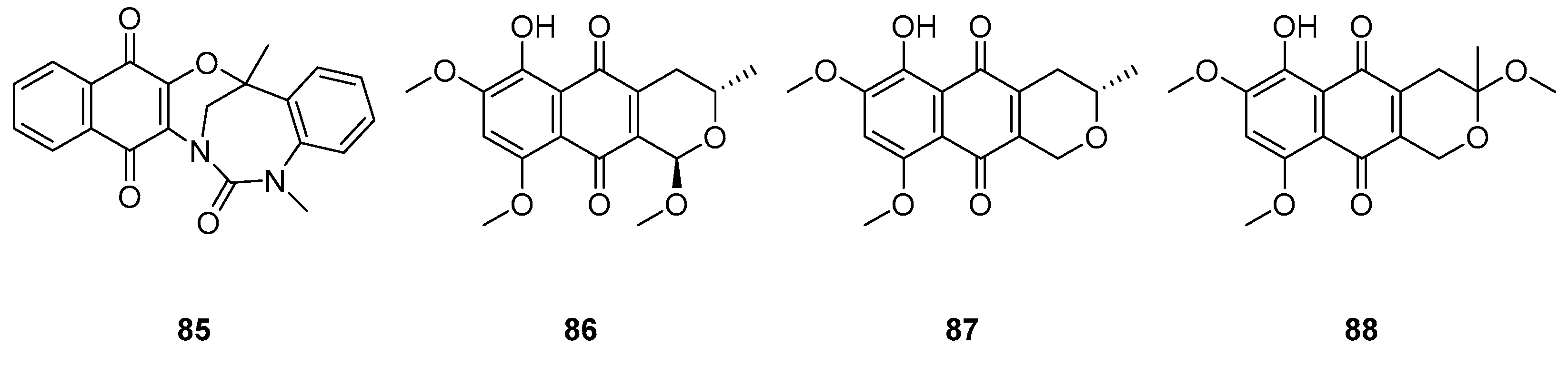

- Dyshlovoy, S.A.; Pelageev, D.N.; Jakob, L.S.; Borisova, K.L.; Hauschild, J.; Busenbender, T.; Kaune, M.; Khmelevskaya, E.A.; Graefen, M.; Bokemeyer, C.; Anufriev, V.P.; von Amsberg, G. In Pharmaceuticals, 2021; Vol. 14.

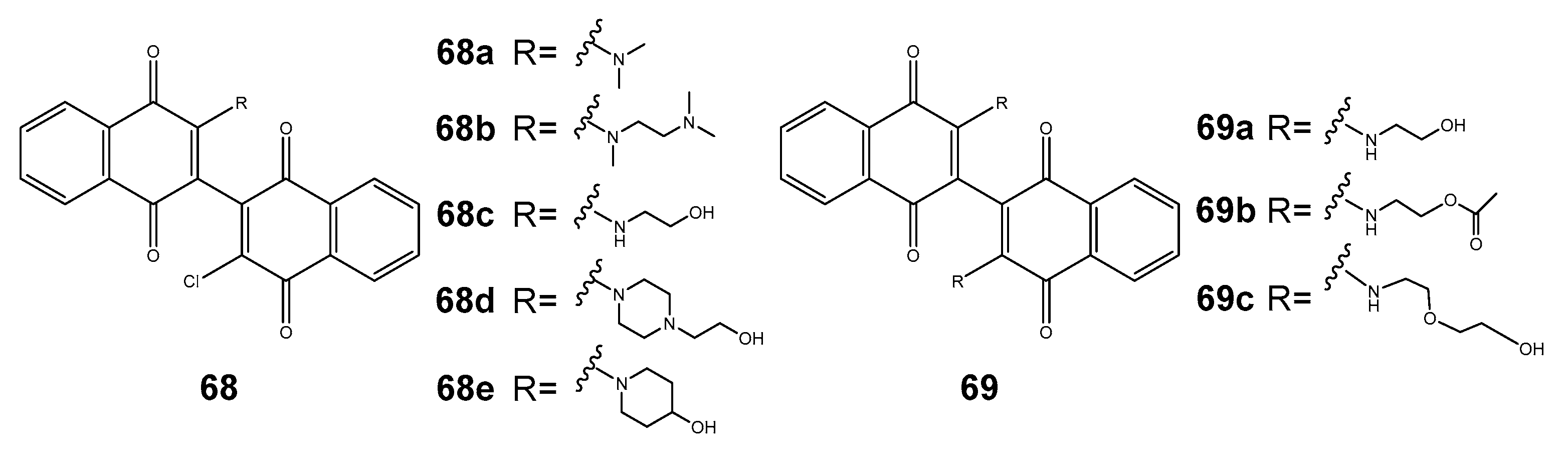

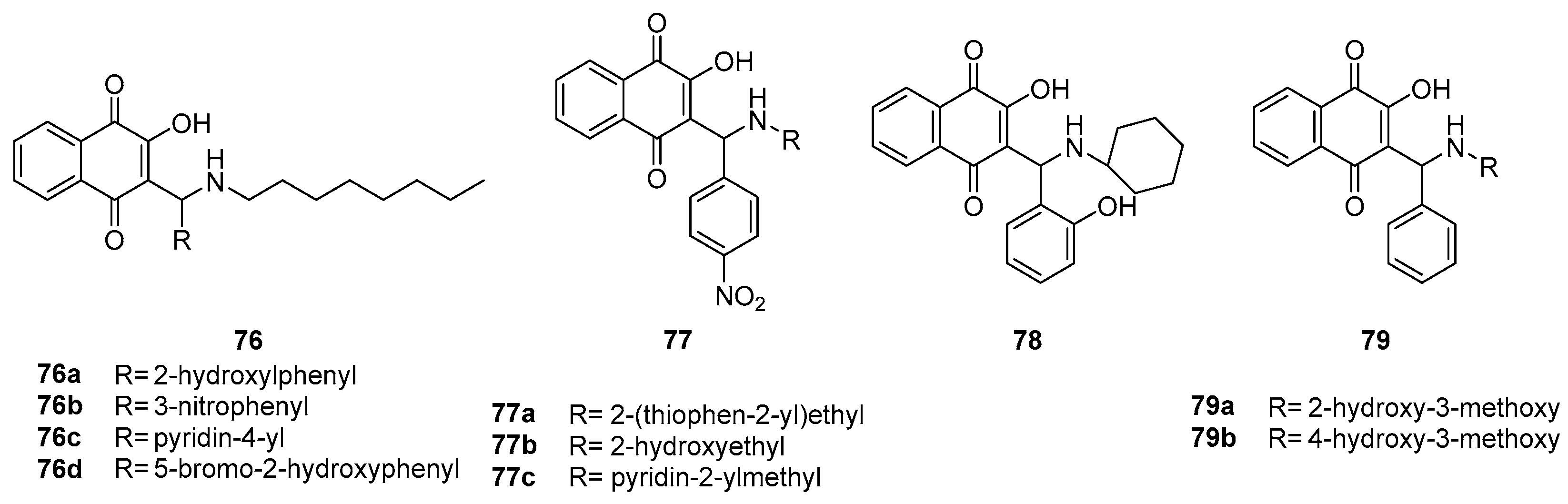

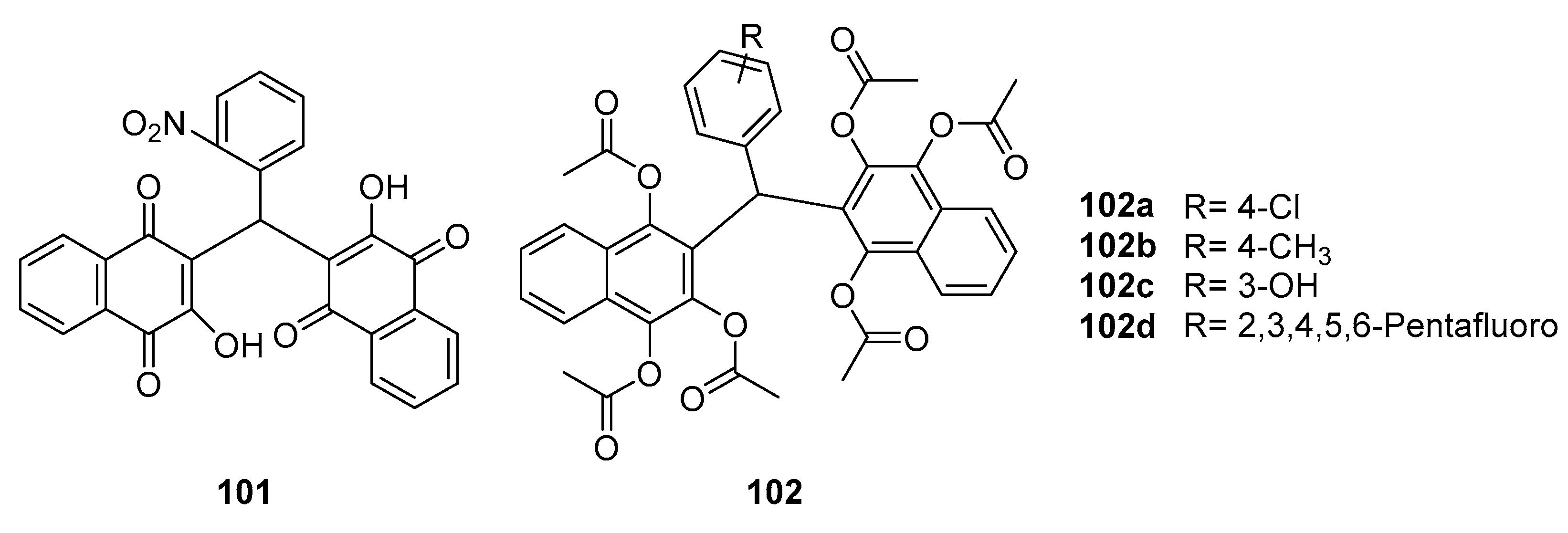

- Ferraris, D.; Lapidus, R.; Truong, P.; Bollino, D.; Carter-Cooper, B.; Lee, M.; Chang, E.; LaRossa-Garcia, M.; Dash, S.; Gartenhaus, R.; Choi, Y.E.; Kipe, O.; Lam, V.; Mason, K.; Palmer, R.; Williams, E.; Ambulos, N.; Kamangar, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kapadia, B.; Jing, Y.; Emadi, A. , Pre-Clinical Activity of Amino-Alcohol Dimeric Naphthoquinones as Potential Therapeutics for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 22, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xiao-Long, H.; Chun-Lian, W.U. , The Research Progress of Cell Apoptosis Induced by Shikonin and Signal Pathway of Apoptosis. Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 2016. [Google Scholar]

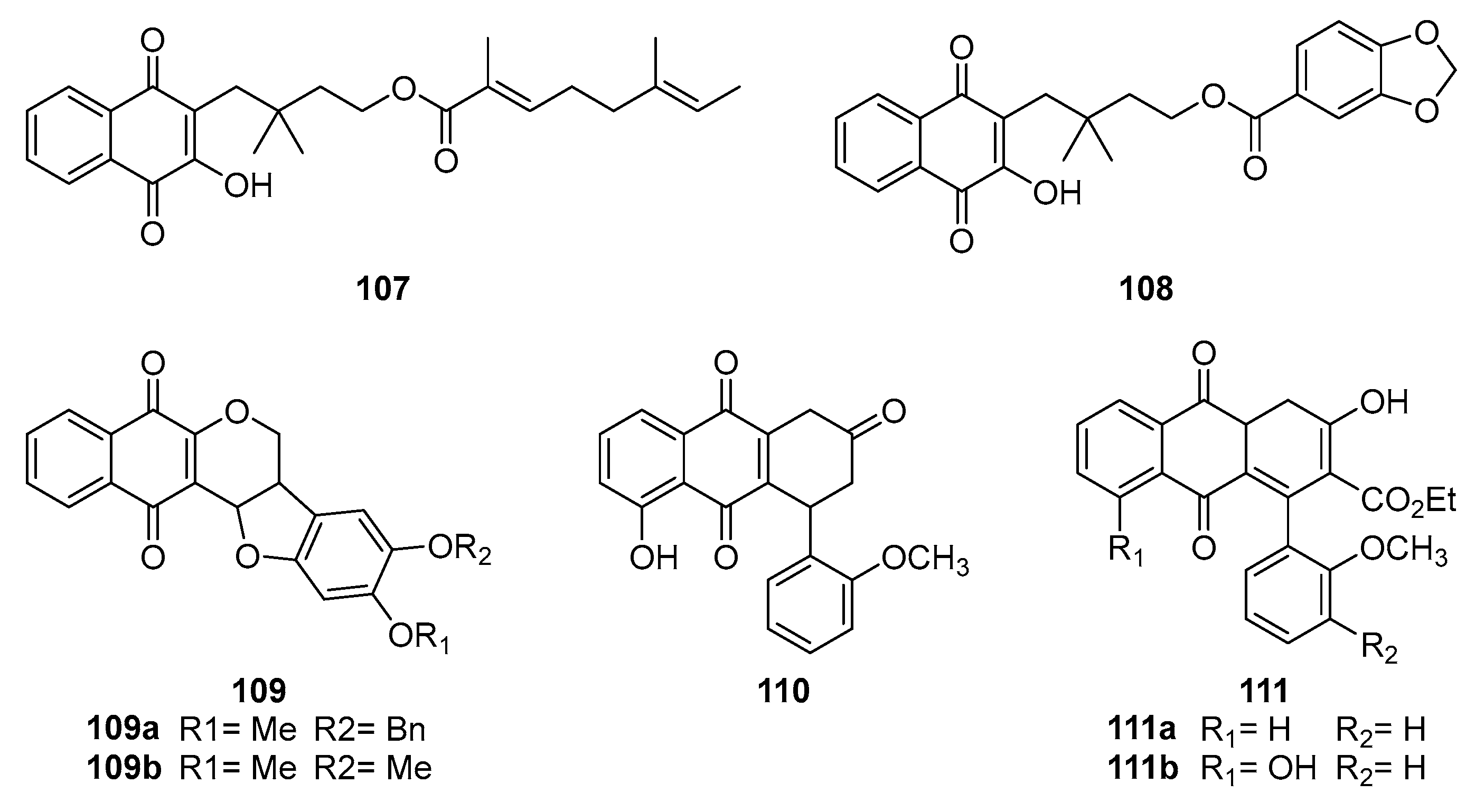

- Zhang, X.; Cui, J.-H.; Meng, Q.-Q.; Li, S.-S.; Zhou, W.; Xiao, S. , Advance in Anti-tumor Mechanisms of Shikonin, Alkannin and their Derivatives. Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 18, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Chen, Y.; Duan, W.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, H.; Ding, J. , SH-7, a new synthesized shikonin derivative, exerting its potent antitumor activities as a topoisomerase inhibitor. International Journal of Cancer 2006, 119, 1184–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

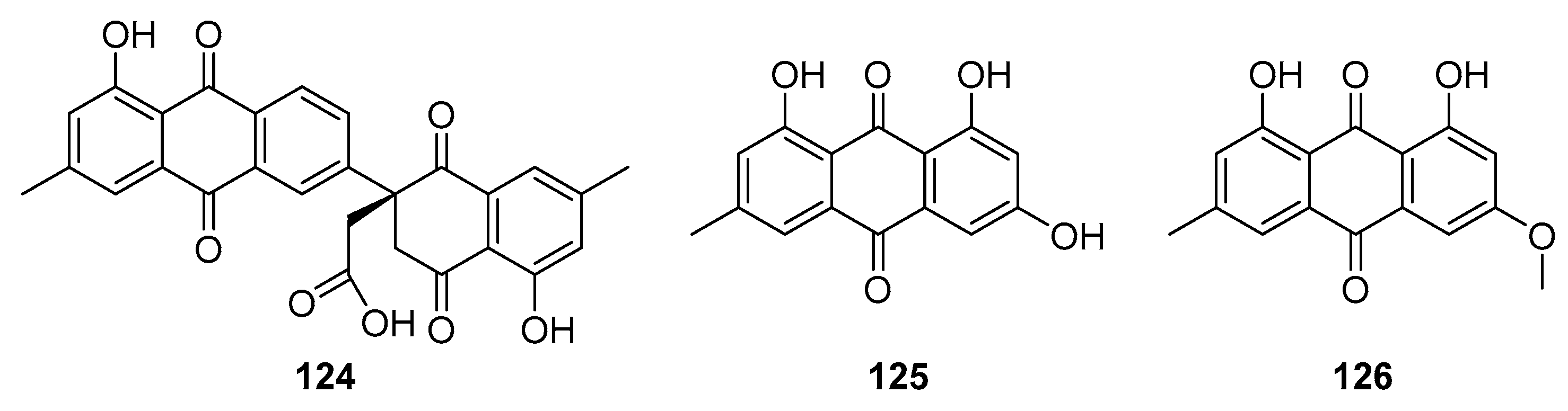

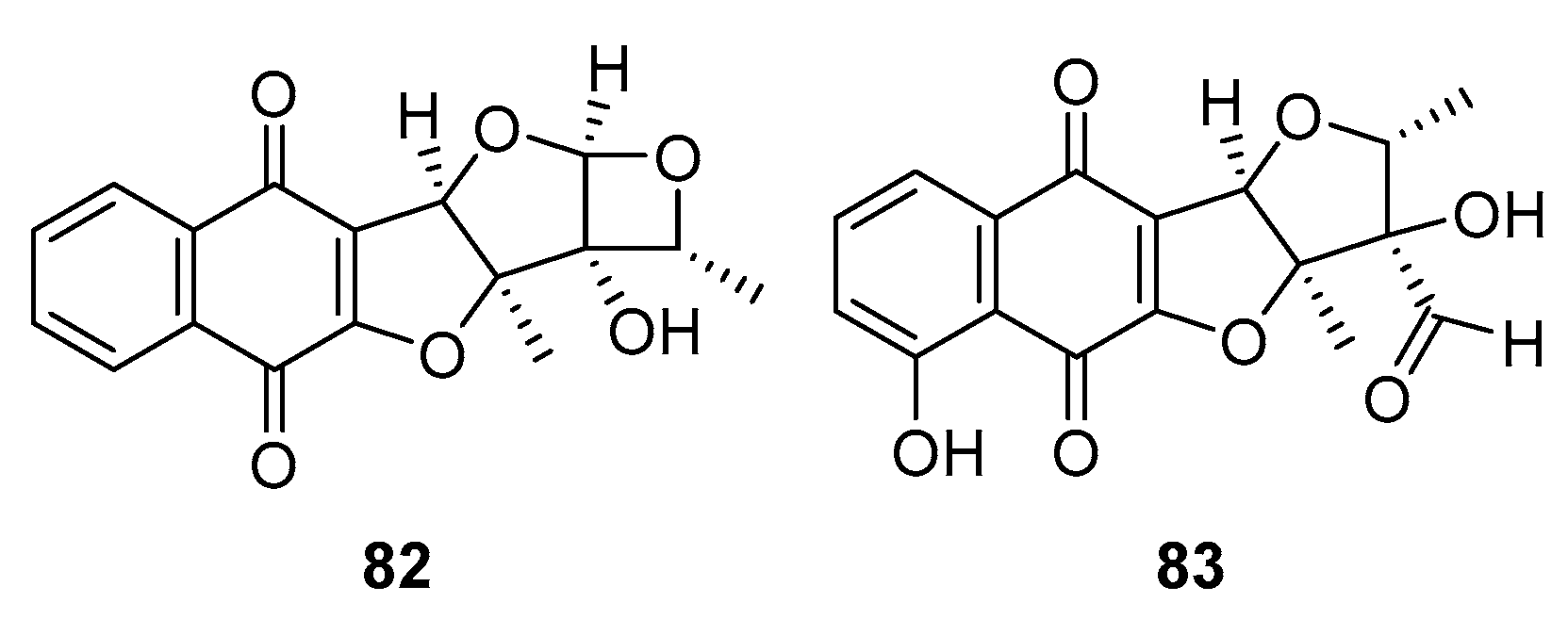

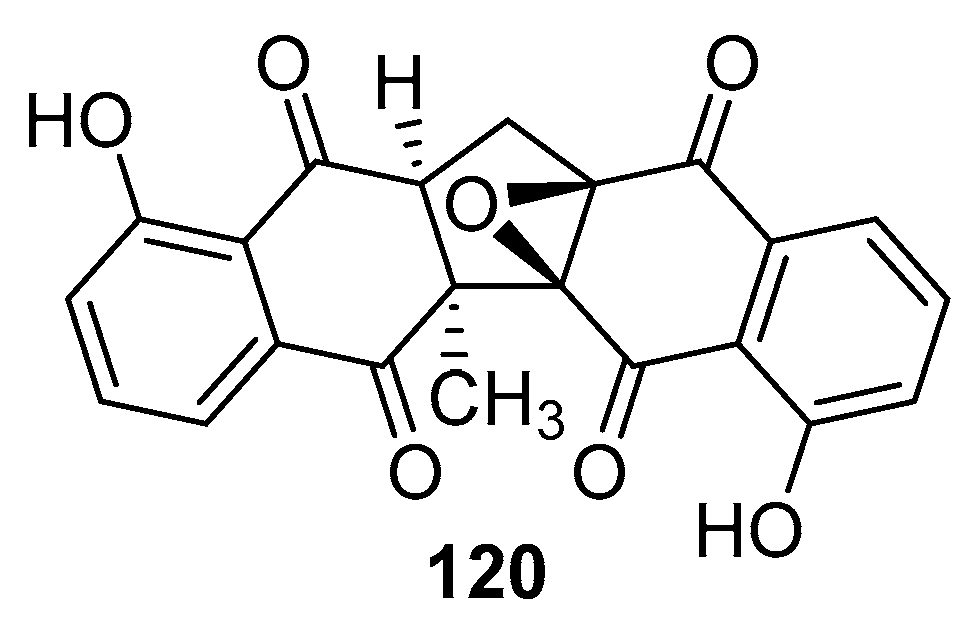

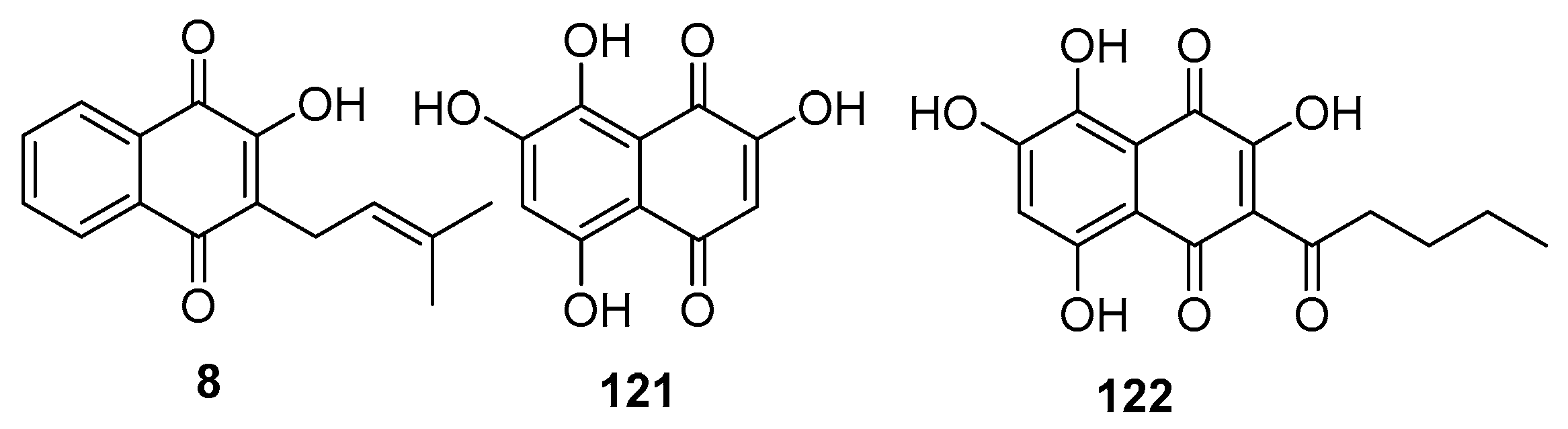

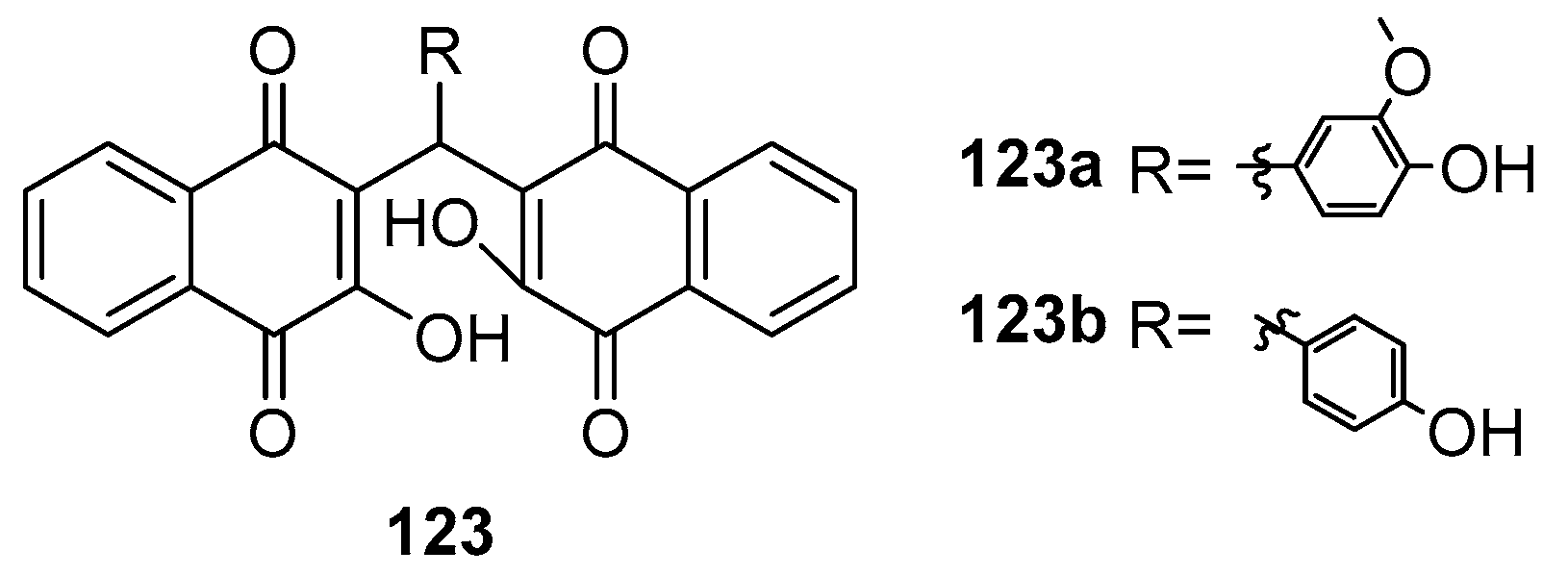

- Kamo, S.; Kuramochi, K.; Tsubaki, K. , Recent topics in total syntheses of natural dimeric naphthoquinone derivatives. Tetrahedron Letters 2018, 59, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

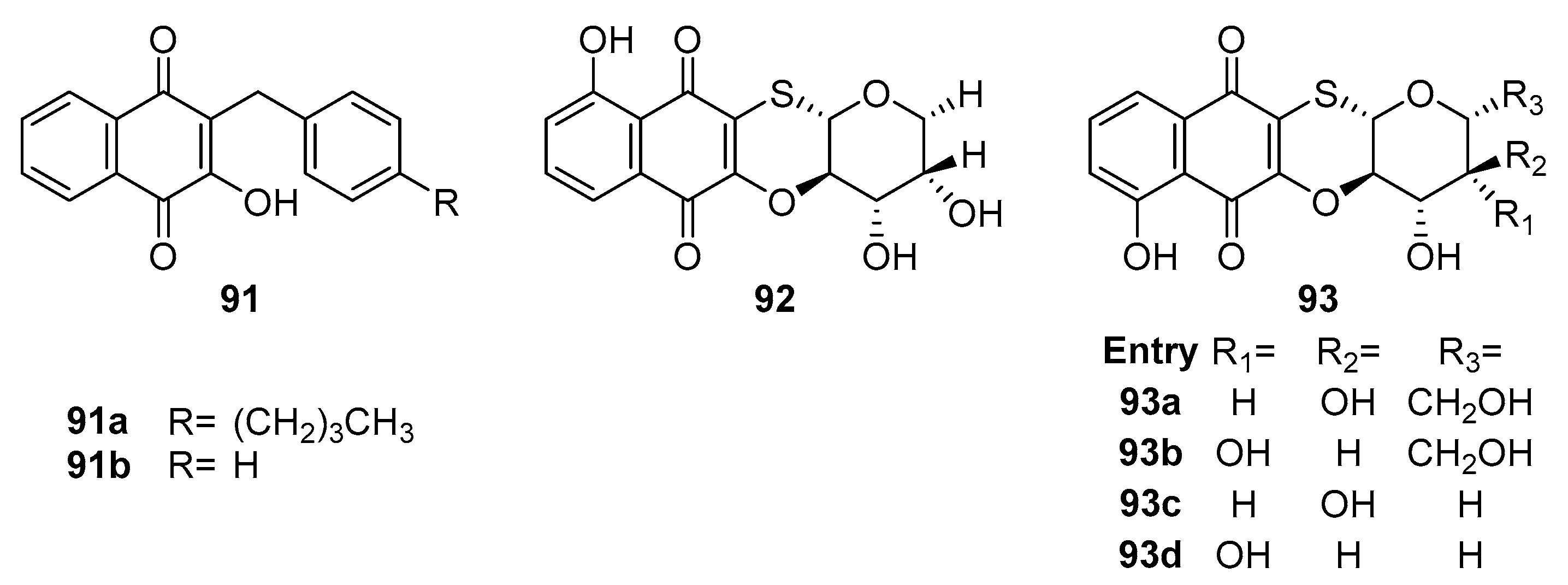

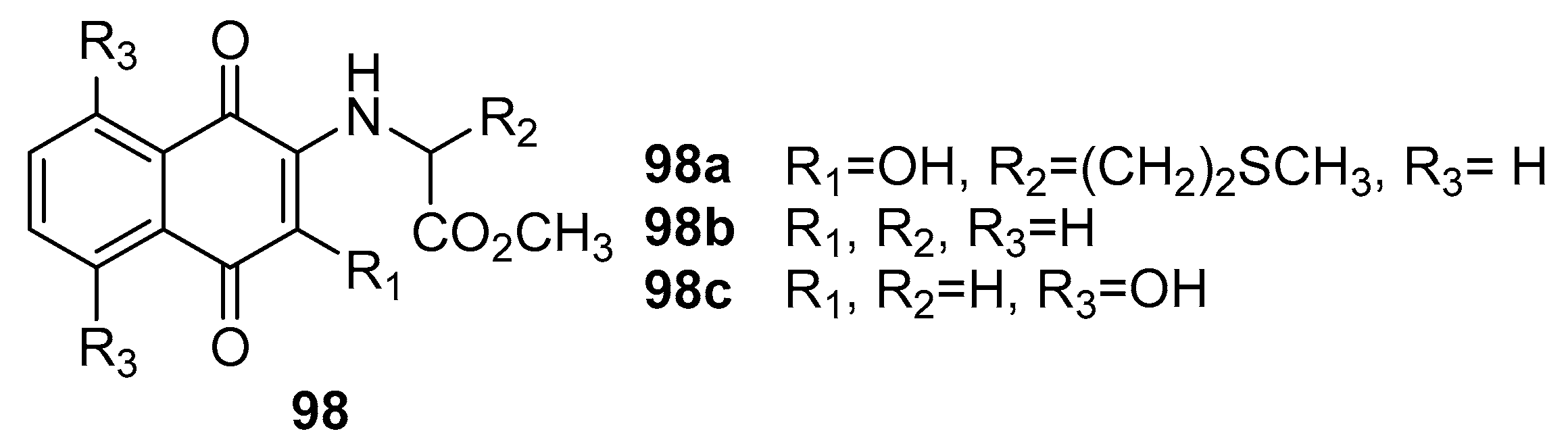

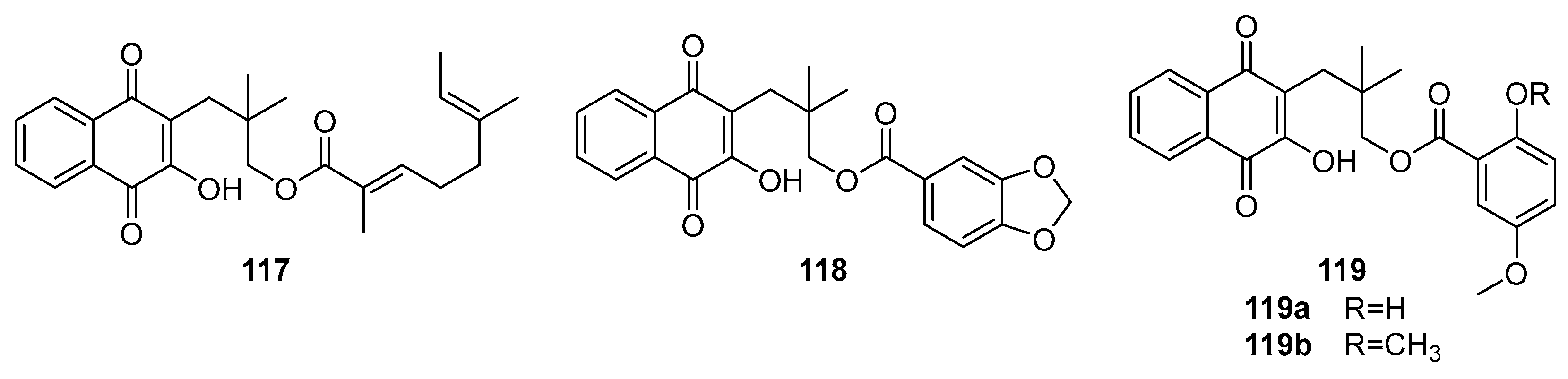

- Wang, R.; Zhang, X.; Song, H.; Zhou, S.; Li, S. , Synthesis and evaluation of novel alkannin and shikonin oxime derivatives as potent antitumor agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2014, 24, 4304–4307. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, J.; Sun, G.; Meng, Q.; Li, S. , DMAKO-20 as a New Multitarget Anticancer Prodrug Activated by the Tumor Specific CYP1B1 Enzyme. Molecular Pharmaceutics 2019, 16, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

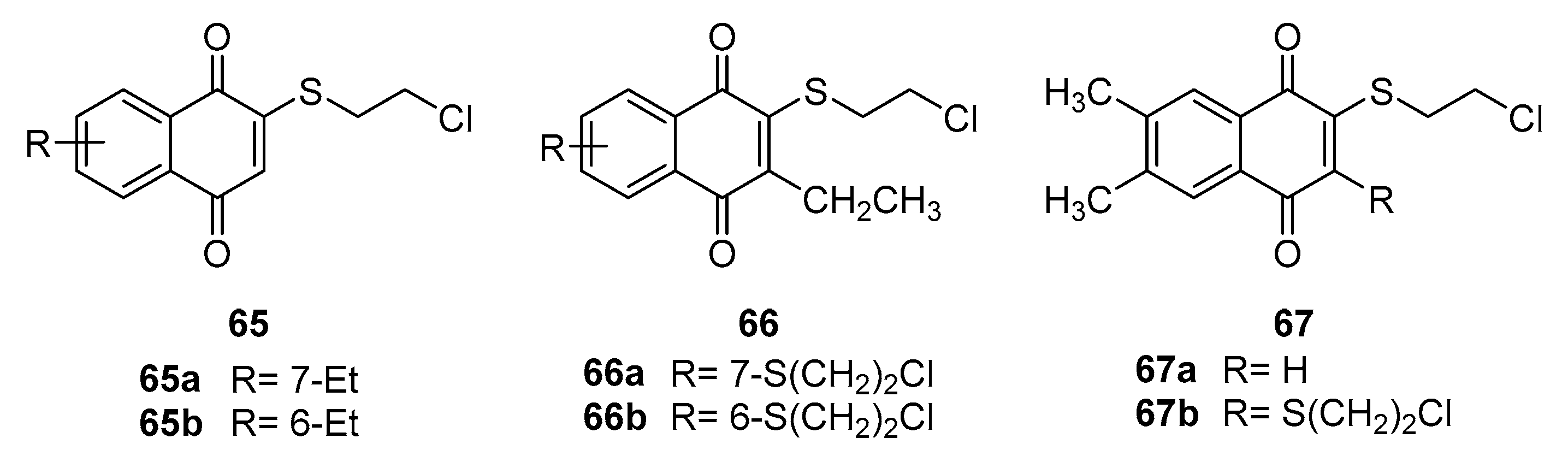

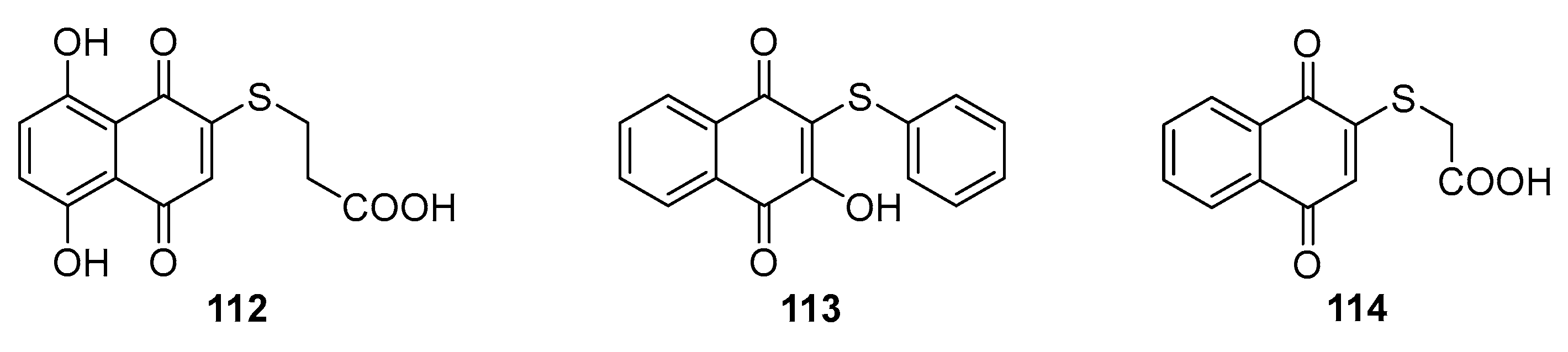

- Huang, G.; Zhao, H.-R.; Meng, Q.-Q.; Zhang, Q.-J.; Dong, J.-Y.; Zhu, B.-q.; Li, S.-S. , Synthesis and biological evaluation of sulfur-containing shikonin oxime derivatives as potential antineoplastic agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2018, 143, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Dong, J.-Y.; Zhang, Q.-J.; Meng, Q.-Q.; Zhao, H.-R.; Zhu, B.-Q.; Li, S.-S. , Discovery and synthesis of sulfur-containing 6-substituted 5,8-dimethoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone oxime derivatives as new and potential anti-MDR cancer agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 165, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

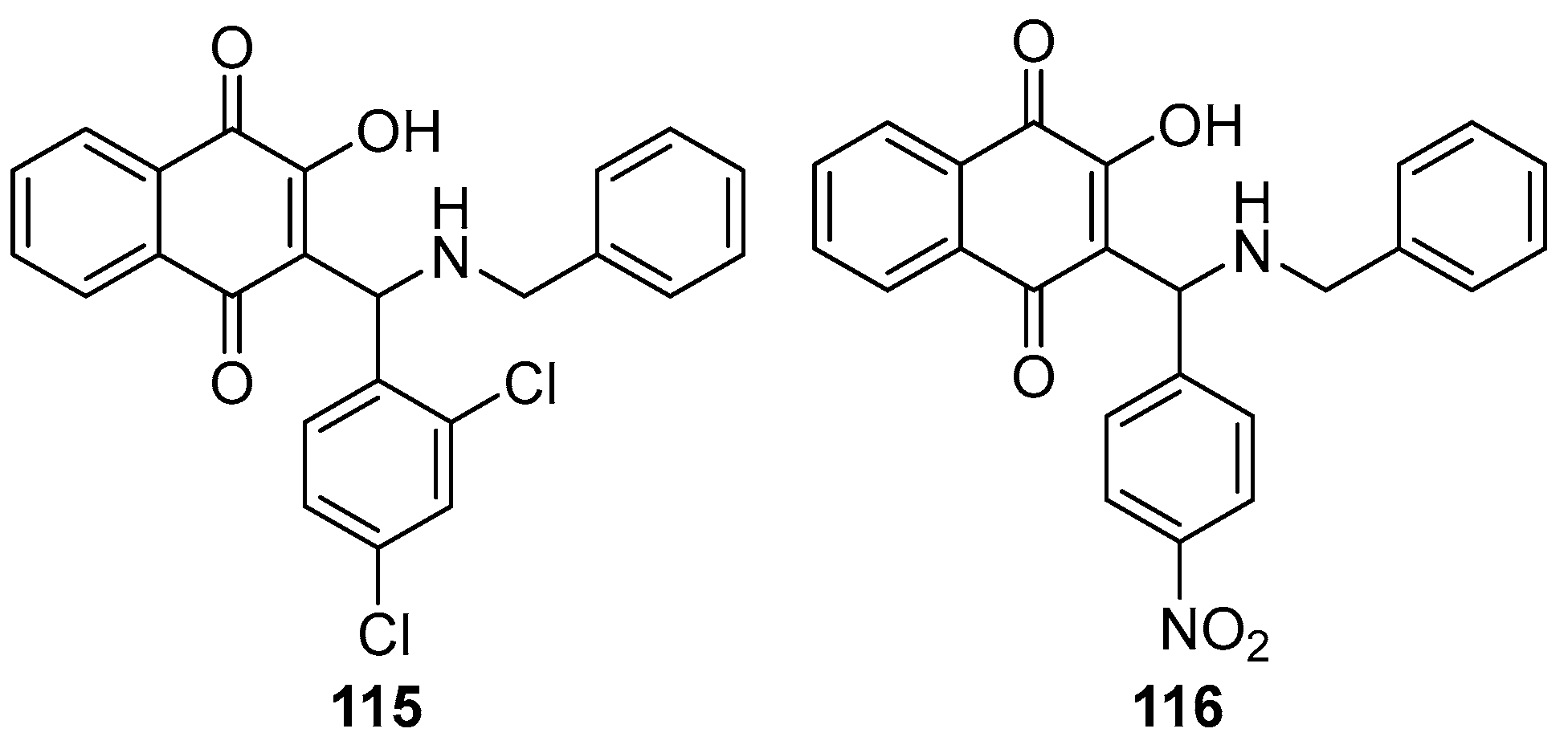

- Nariya, P.; Shukla, F.; Vyas, H.; Devkar, R.; Thakore, S. , Synthesis and characterization of Mannich bases of lawsone and their anticancer activity. Synthetic Communications 2020, 50, 1724–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

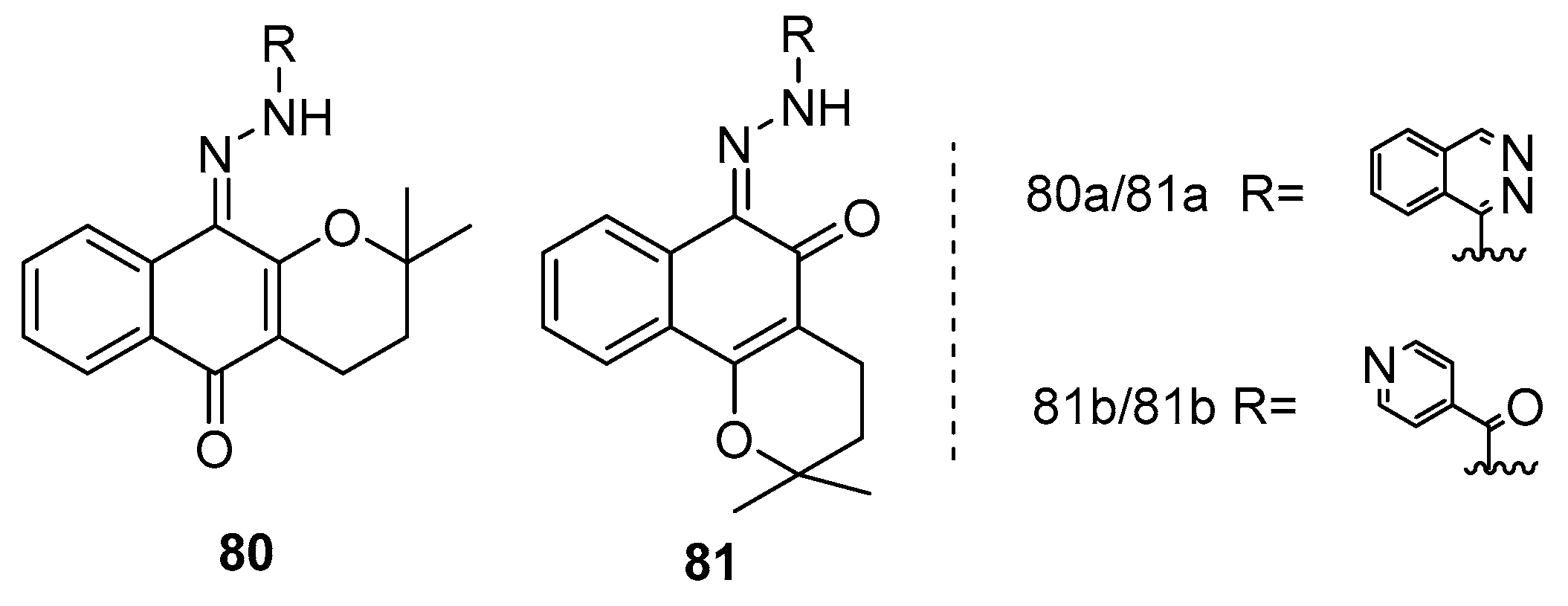

- Guimaráes, G.D.; de Assis Gonsalves, A.; Rolim, A.L.; Araújo, C.E.; dos Anjos Santos, L.V.; Silva, F.S.M.; de Cássia Evangelista de Oliveira, F.; da Costa, P.M.; Pessoa, C.; Fonseca Goulart, O.M.; Silva, L.T.; Santos, C.D.; Araújo, R.M.C. , Naphthoquinone-based Hydrazone Hybrids: Synthesis and Potent Activity Against Cancer Cell Lines. Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 17, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Said, M.S.; Borade, B.R.; Gonnade, R.; Barvkar, V.; Kontham, R.; Dastager, S.G. , Enceleamycins A–C, Furo-Naphthoquinones from Amycolatopsis sp. MCC0218: Isolation, Structure Elucidation, and Antimicrobial Activity. Journal of Natural Products 2022, 85, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nural, Y.; Ozdemir, S.; Doluca, O.; Demir, B.; Yalcin, M.S.; Atabey, H.; Kanat, B.; Erat, S.; Sari, H.; Seferoglu, Z. , Synthesis, biological properties, and acid dissociation constant of novel naphthoquinone–triazole hybrids. Bioorganic Chemistry 2020, 105, 104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, C.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Duraipandiyan, V.; Ignacimuthu, S. , Bluemomycin, a new naphthoquinone derivative from Streptomyces sp. with antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties. Biotechnology Letters 2021, 43, 1005–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supratman, U.; Hirai, N.; Sato, S.; Watanabe, K.; Malik, A.; Annas, S.; Harneti, D.; Maharani, R.; Koseki, T.; Shiono, Y. , New naphthoquinone derivatives from Fusarium napiforme of a mangrove plant. Natural Product Research 2021, 35, 1406–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.G.T.; Miranda, F.F.; Ferreira, V.F.; Freitas, C.C.; Rabello, R.F.; Carballido, J.M.; Corrêa, L.C.D. , Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation of 3-hydrazino-naphthoquinones as analogs of lapachol. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society 2001, 12, 791–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Yu, B.; Friedrich, D.; Li, J.; Shen, H.; Krautscheid, H.; Huang, S.D.; Kim, M.-H. , Naphthoquinone-derivative as a synthetic compound to overcome the antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Communications Biology 2020, 3, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabutski, Y.E.; Menchinskaya, E.S.; Shevchenko, L.S.; Chingizova, E.A.; Chingizov, A.R.; Popov, R.S.; Denisenko, V.A.; Mikhailov, V.V.; Aminin, D.L.; Polonik, S.G. In Molecules, 2020; Vol. 25.

- Kim, K.; Kim, D.; Lee, H.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, K.-Y.; Kim, H. In Biomedicines, 2020; Vol. 8.

- Gemili, M.; Nural, Y.; Keleş, E.; Aydıner, B.; Seferoğlu, N.; Ülger, M.; Şahin, E.; Erat, S.; Seferoğlu, Z. , Novel highly functionalized 1,4-naphthoquinone 2-iminothiazole hybrids: Synthesis, photophysical properties, crystal structure, DFT studies, and anti(myco)bacterial/antifungal activity. Journal of Molecular Structure 2019, 1196, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, C.; Aucamp, J.; Smit, F.J.; Seldon, R.; Jordaan, A.; Warner, D.F.; N'Da, D.D. , Synthesis and comparison of in vitro dual anti-infective activities of novel naphthoquinone hybrids and atovaquone. Bioorganic Chemistry 2021, 114, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, V.K.; Maurya, H.K.; Yadav, D.B.; Tripathi, A.; Kumar, M.; Shukla, P.K. , Naphtho[2,3-b][1,4]-thiazine-5,10-diones and 3-substituted-1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl-thioalkanoate derivatives: Synthesis and biological evaluation as potential antibacterial and antifungal agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2006, 16, 5883–5887. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, V.K.; Yadav, D.B.; Singh, R.V.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Shukla, P.K. , Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel (l)-α-amino acid methyl ester, heteroalkyl, and aryl substituted 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives as antifungal and antibacterial agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2005, 15, 5324–5328. [Google Scholar]

- Tandon, V.K.; Maurya, H.K.; Mishra, N.N.; Shukla, P.K. , Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel nitrogen and sulfur containing hetero-1,4-naphthoquinones as potent antifungal and antibacterial agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 44, 3130–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, D.T.G.; Gomes, R.S.P.; Marra, R.K.F.; Silva, F.C.d.; Gomes, M.W.L.; Ferreira, D.F.; Santos, R.M.A.; Pinto, A.M.V.; Ratcliffe, N.A.; Cirne-Santos, C.C.; Barros, C.S.; Ferreira, V.F.; Paixão, I.C.N.P. , Inhibition of Zika Virus Replication by Synthetic Bis-Naphthoquinones. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society 2019, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jia, J. , Discovery of juglone and its derivatives as potent SARS-CoV-2 main proteinase inhibitors. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 113789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Huang, B.; Tang, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, M.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhu, W.; Cao, D. , The complex structure of GRL0617 and SARS-CoV-2 PLpro reveals a hot spot for antiviral drug discovery. Nature Communications.

- Sendl, A.; Chen, J.L.; Jolad, S.D.; Stoddart, C.; Rozhon, E.; Kernan, M.; Nanakorn, W.; Balick, M. , Two new naphthoquinones with antiviral activity from Rhinacanthus nasutus. Journal of Natural Products 1996, 59, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.J.M.D.; Buarque, C.D.; Brito, F.V.; Aurelian, L.; Costa, P.R.R. , Synthesis and preliminary pharmacological evaluation of new (+/-) 1,4-naphthoquinones structurally related to lapachol. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2002, 10, 2731–2738. [Google Scholar]

- Ilina, T.V.; Semenova, E.A.; Pronyaeva, T.R.; Pokrovskii, A.G.; Tolstikov, G.A. , Inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by aryl-substituted naphto- and anthraquinones. Doklady Biochemistry & Biophysics 2002, 382, 56. [Google Scholar]

- A, V.K.T.; B, R.B.C.; C, R.V.S.; B, S.R.; A, D.B.Y. , Design, synthesis and evaluation of novel 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives as antifungal and anticancer agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2004, 14, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Ngoc, T.M.; Phuong, N.T.T.; Khoi, N.M.; Park, S.J.; Kwak, H.J.; Nhiem, N.X.; Trang, B.T.T.; Tai, B.H.; Song, J.H.; Ko, H.J. , A new naphthoquinone analogue and antiviral constituents from the root of Rhinacanthus nasutus. Natural Product Research 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetina-Montejo, L.; Ayora-Talavera, G.; Borges-Argáez, R. , Zeylanone epoxide isolated from Diospyros anisandra stem bark inhibits influenza virus in vitro. Archives of Virology, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zima, V.; Radilová, K.; Koíek, M.; Albiana, C.B.; Machara, A. , Unraveling the Anti-Influenza Effect of Flavonoids: Experimental Validation of Luteolin and its Congeners as Potent Influenza Endonuclease Inhibitors. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 112754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisseh, Z.N.; Bazgir, A. , An efficient, clean synthesis of 3,3′-(arylmethylene)bis(2-hydroxynaphthalene-1,4-dione) derivatives. dyes\&\pigments 2009, 83, 258–261. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, X.; Zhao, J.Y.; Liu, N.; Chen, M.H.; Ma, B.P. , Anthraquinone analogues with inhibitory activities against influenza a virus from Polygonatum odoratum. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

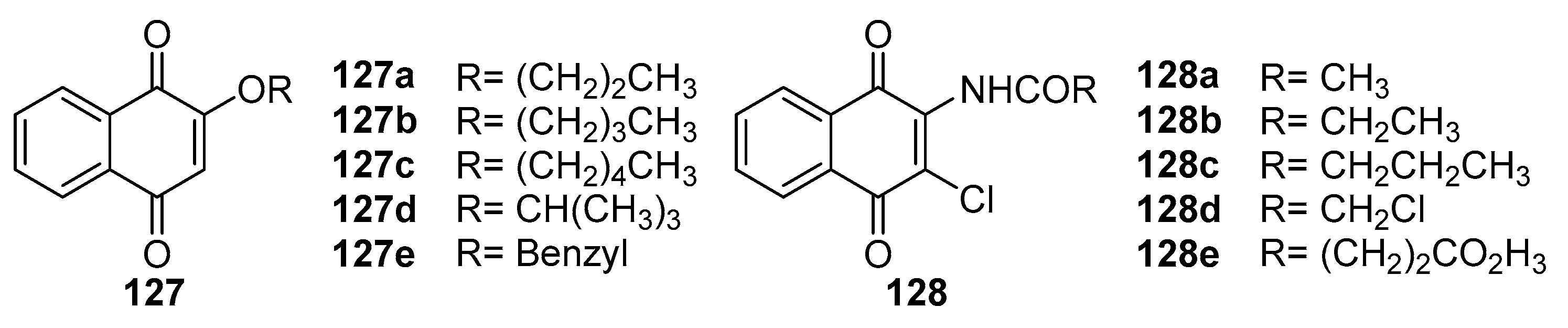

- Lien, J.C.; Huang, L.J.; Teng, C.M.; Wang, J.P.; Kuo, S.C. , Synthesis of 2-alkoxy 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives as antiplatelet, antiinflammatory, and antiallergic agents. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2010, 33, 105–105. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, J.C.; Huang, L.J.; Wang, J.P.; Teng, C.M.; Lee, K.H.; Kuo, S.C. , Synthesis and antiplatelet, antiinflammatory and antiallergic activities of 2,3-disubstituted 1,4-naphthoquinones. Cheminform 1996, 27, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).